| Revision as of 09:56, 25 May 2012 editHohenloh (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers18,739 edits Undid revision 494253438 by 87.112.8.182 (talk) - according to the article it was 100← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:04, 20 January 2025 edit undoManfredHugh (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users11,426 edits illustration out of placeTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Part of the French Revolutionary Wars}} | |||

| {{Use Hiberno-English|date=January 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| |conflict |

| conflict = Irish Rebellion of 1798 | ||

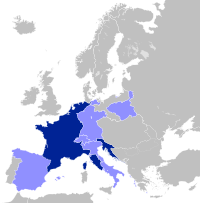

| | partof = the ] and the ] | |||

| |campaign = | |||

| |colour_scheme = background:#bbcccc | | colour_scheme = background:#bbcccc | ||

| |image |

| image = Vinhill.gif | ||

| | |

| image_size = 300px | ||

| | caption = ] by ] (1880) "Charge of the ] on the insurgents – a recreant ] having deserted to them in uniform is being cut down" | |||

| |date = 24 May – 23 September 1798 | |||

| | date = {{nowrap|24 May – 12 October 1798}} <br />(4 months and 18 days) | |||

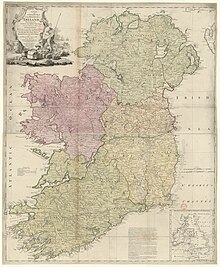

| |place = ] | |||

| | place = Ireland | |||

| |result = Rebellion crushed, ] | |||

| | result = Suppression by Crown forces | |||

| |territory = | |||

| * ] and creation of the ] in 1801 | |||

| |combatant1 = {{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland 17th century.svg}} ]<br>{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland 17th century.svg}} ]<br>{{flagicon|France}} ] | |||

| * Attempt to renew the insurrection with a ] | |||

| |combatant2 = {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Ireland}} ] | |||

| * Guerrilla activity in counties ] until 1800, ] until 1803 and ] until 1804. | |||

| |commander1 = Major leaders including:<br>{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland 17th century.svg}} ]<br>{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland 17th century.svg}} ]<br>{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland 17th century.svg}} ]<br>{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland 17th century.svg}} ]<br>{{flagicon|France}} ] | |||

| | combatant1 = {{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br />{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br />{{flagcountry|First French Republic}} | |||

| |commander2 = Including:<br>{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ] | |||

| | combatant2 = {{flagcountry|Kingdom of Great Britain}} | |||

| |strength1 = 50,000 United Irish fighters,<br>1,100 French regulars, marines & sailors,<br>10–15 ships<ref> BBC</ref> | |||

| * {{flagcountry|Kingdom of Ireland}} | |||

| |strength2 = 40,000 militia<br>30,000 British regulars<br>~25,000 yeomanry<br>] | |||

| | commander1 = {{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br />{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br/>{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br/>{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br />{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br />{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br />{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br />{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br/>{{Flagicon image|Green harp flag of Ireland.svg}} ]<br/>{{flagicon|French First Republic}} ]<br>{{flagicon|French First Republic}} ] | |||

| |casualties1 = c. 10,000<ref>Thomas Bartlett, Clemency and Compensation, the treatment of defeated rebels and suffering loyalists after the 1798 rebellion, in Revolution, Counter-Revolution and Union, Ireland in the 1790s, Jim Smyth ed, Cambridge, 2000, p100</ref>-50,000<ref name="thomas1969">], P.392 The Year of Liberty (1969) ISBN 0-586-03709-8</ref> estimated United Irish and civilian deaths | |||

| | commander2 = {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ] | |||

| |casualties2 = c. 500- 2,000 military <ref>Bartlett, p100</ref> | |||

| | strength1 = {{resize|95%|50,000 United Irishmen<br />4,100 French ]<br />10 ] ships<ref> (BBC).</ref>}} | |||

| Over 1,000 loyalist civilian deaths{{Citation needed|date=August 2010}} }} | |||

| | strength2 = {{resize|95%|40,000 ]<br />30,000 British ]<br />~25,000 ]<br />~1,000 ]}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Irish Rebellion of 1798}} | |||

| | casualties1 = {{resize|95%|10,000<ref>Thomas Bartlett, ''Clemency and Compensation, the treatment of defeated rebels and suffering loyalists after the 1798 rebellion, in Revolution, Counter-Revolution and Union, Ireland in the 1790s'', Jim Smyth ed, Cambridge, 2000, p. 100</ref>–50,000<ref name="thomas1969">], p. 392 ''The Year of Liberty'' (1969) {{ISBN|0-586-03709-8}}</ref> estimated combatant and civilian deaths<br />3,500 French captured<br />7 French ships captured}} | |||

| | casualties2 = {{resize|95%|500–2,000 military deaths<ref>Bartlett, p. 100</ref><br />c. 1,000 ] civilian deaths<ref>Richard Musgrave (1801). ''Memoirs of the different rebellions in Ireland'' (see Appendices)</ref>}} | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Irish Rebellion of 1798}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox French Revolutionary Wars}} | {{Campaignbox French Revolutionary Wars}} | ||

| }} | |||

| The '''Irish Rebellion of 1798''' ({{langx|ga|Éirí Amach 1798}}; ]: ''The Turn out'',<ref>{{Cite web |last=Patterson |first=William Hugh |date=1880 |title=Glossary of Words in the Counties of Antrim and Down |url=http://www.ulsterscotsacademy.com/texts/historical-abstracts/1800-1899/pattersons-glossary/t.php |access-date=2024-10-29 |website=www.ulsterscotsacademy.com}}</ref> ''The Hurries'',<ref>{{Cite web |last=Patterson |first=William Hugh |date=1880 |title=Glossary of Words in the Counties of Antrim and Down |url=http://www.ulsterscotsacademy.com/texts/historical-abstracts/1800-1899/pattersons-glossary/h.php |access-date=2020-11-04 |website=www.ulsterscotsacademy.com}}</ref> 1798 Rebellion<ref>{{Cite book |title=Revolution, counter-revolution, and union: Ireland in the 1790s |date=2000 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-66109-6 |editor-last=Smyth |editor-first=Jim |location=Cambridge; New York}}</ref>) was a popular insurrection against the ] in what was then the separate, but subordinate, ]. The main organising force was the ]. First formed in ] by ] opposed to the landed ], the Society, despairing of reform, sought to secure a republic through a revolutionary union with the country's ] majority. The grievances of a ]ed tenantry drove recruitment. | |||

| The '''Irish Rebellion of 1798''' ({{lang-ga|Éirí Amach 1798}}), also known as the '''United Irishmen Rebellion''' ({{lang-ga|Éirí Amach na nÉireannach Aontaithe}}), was an uprising against ] ] lasting from May to September 1798. The ], a ] revolutionary group influenced by the ideas of the ] and ] revolutions, were the main organising force behind the rebellion. | |||

| While assistance was being sought from the ] and from democratic militants in Britain, martial-law seizures and arrests forced the conspirators into the open. Beginning in late May 1798, there were a series of uncoordinated risings: in the counties of ] and ] in the southeast where the rebels met with some success; in the north around Belfast in counties ] and ]; and closer to the capital, ], in counties ] and ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| In late August, after the rebels had been reduced to pockets of guerrilla resistance, the French landed an ] in the west, in ]. Unable to effect a conjunction with a significant rebel force, they surrendered on 9 September. In the last open-field engagement of the rebellion, the local men they had rallied on their arrival were routed at ] on 23 September. On 12 October, a second French expedition was defeated in a ] off the coast of ] leading to the capture of the United Irish leader ]. | |||

| In the wake of the rebellion, ] abolished the ] and brought Ireland under the crown of a ] through the ]. The centenary of the rebellion in 1898 saw its legacy disputed by ] who wished to restore a legislature in Dublin, by ] who invoked the name of Tone in the cause of complete separation and independence, and by ] opposed to all measures of Irish self-government. Renewed in a bicentenary year that coincided with the ], the debate over the interpretation and significance of "1798" continues. | |||

| == Background == | == Background == | ||

| Since 1691 and the end of the ], Ireland had chiefly been controlled by the minority ] ] constituting members of the ] loyal to the ]. It governed through a form of institutionalised ] codified in the ] which discriminated against both the majority ] population and non-Anglican Protestants (for example ]). In the late 18th century, ] elements among the ruling class were inspired by the example of the ] (1776–1783) and sought to form common cause with the Catholic populace to achieve reform and greater autonomy from Britain. As in England, the majority of Protestants, as well as all Catholics, were barred from voting because they did not pass a property threshold. | |||

| Another grievance was that Ireland, although nominally a sovereign kingdom governed by the monarch and Parliament of the island, in reality had less independence than most of Britain's North American colonies, due to a series of laws enacted by the English, such as Poynings' law of 1494 and the Declaratory Act of 1720, the former of which gave the English veto power over Irish legislation, and the latter of which gave the British the right to legislate for the kingdom.<ref>Bartlett, Thomas Kevin Dawson Daire Keough The ''1798 Rebellion: An Illustrated History'' Roberts Rineheart Publishers 1998 pages 4-19</ref> | |||

| ], ] leader.]] | |||

| === The Volunteer movement === | |||

| When France joined the Americans in support of their ], London called for volunteers to join ]s to defend Ireland against the threat of invasion from France (since regular British forces had been dispatched to America). Many thousands joined the ]. In 1782 they used their newly powerful position to force the Crown to grant the landed Ascendancy self-rule and a more independent parliament ("]"). The ], led by ], pushed for greater enfranchisement. In 1793 parliament passed laws allowing Catholics with some property to vote, but they could neither be elected nor appointed as state officials. Liberal elements of the Ascendancy seeking a greater franchise for the people, and an end to religious discrimination, were further inspired by the ], which had taken place in a Catholic country. | |||

| In the last decades of the 18th century, the ] in Ireland faced growing demands for constitutional reform. The ] had relaxed the ] by which, in the wake of the ], it had sought to break the power, and reduce the influence, both of the ] and of the remaining Catholic ].<ref name="Cullen-1986">{{Cite journal |last=Cullen |first=Louis |date=1986 |title=Catholics under the Penal Laws |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/30070812 |journal=Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr |volume=1 |pages=23–36 |doi=10.3828/eci.1986.4 |jstor=30070812 |s2cid=150607757 |issn=0790-7915}}</ref> But the landed Anglican interest continued to monopolise the Irish Parliament, occupying both the ] and, through the system of ], half of the ].<ref name="Kennedy-1992">{{Cite journal |last=Kennedy |first=Denis |date=1992 |title=The Irish Opposition, Parliamentary Reform and Public Opinion, 1793–1794 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/30070925 |journal=Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr |volume=7 |pages=95–114 |doi=10.3828/eci.1992.7 |issn=0790-7915 |jstor=30070925 |s2cid=256154966}}</ref> The interests of the Crown were meanwhile secured by a ] accountable, not to the legislature in Dublin, but to the King and his ministers in London (and which also having boroughs in its pocket reduced to a third the number of Commons seats open to electoral contest).<ref name="Kennedy-1992" /> Additionally, the British parliament presumed the right to itself to legislate for Ireland, a prerogative it had exercised to restrict rival Irish trade and commerce.<ref name="Gill & Macmillan">{{cite book |last1=Bardon |first1=Jonathan |title=A History of Ireland in 250 Episodes |date=2008 |publisher=Gill & Macmillan |isbn=978-0717146499 |location=Dublin |pages=}}</ref>{{rp|286–288}} | |||

| The ] presented a challenge. War with the colonists and with their French allies drew down the Crown's regular forces in Ireland. In their absence ] were formed, ostensibly for home defence, but soon, like their kinsmen in the colonies, debating and asserting "constitutional rights".<ref name="Smyth-2000">"''Revolution, Counter-Revolution and Union''" (Cambridge University Press, 2000) Ed. Jim Smyth {{ISBN|0-521-66109-9}}, p. 113.</ref> In 1782, with the Volunteers drilling and parading in support of the otherwise beleaguered ] in the Irish Parliament, Westminster repealed its ].<ref name="Costin">{{cite book |title=The Law and Working of the Constitution: Documents 1660–1914 |publisher=A. & C. Black |year=1952 |editor1=Costin, W. C. |volume=I (1660–1783) |location=London |page=147 |editor2=Watson, J. Steven}}</ref><ref name="Cassell's Chronology">{{cite book |last=Williams |first=Hywel |url=https://archive.org/details/cassellschronolo0000will/page/334 |title=Cassell's Chronology of World History |publisher=Weidenfeld & Nicolson |year=2005 |isbn=0-304-35730-8 |location=London |pages=}}</ref> | |||

| == Society of United Irishmen == | |||

| The prospect of reform inspired a small group of Protestant liberals in ] to found the ] in 1791. The organisation crossed the religious divide with a membership comprising Roman Catholics, ], ], other Protestant "]s" groups, and some from the ]. The Society openly put forward policies of further democratic reforms and ], reforms which the ] had little intention of granting. The outbreak of ] earlier in 1793, following the execution of ], forced the Society underground and toward armed insurrection with French aid. The avowed intent of the United Irishmen was to "break the connection with England"; the organisation spread throughout Ireland and had at least 200,000 members by 1797.<ref>*Report of the Secret Committee of (Irish) House of Commons 1798 quoted in T. Pakenham "The Year of Liberty" p.46) ISBN 0-586-03709-8</ref> It linked up with Catholic agrarian resistance groups, known as the ], who had started raiding houses for arms in early 1793. | |||

| Volunteers, especially in the north where ] and other ] had flocked to their ranks, immediately sought to build upon this ] by agitating for the abolition of the pocket boroughs and an extension of the franchise. But the question of whether, and on what terms, parliamentary reform should embrace ] split the movement".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Stewart |first=A. T. Q. |title=A Deeper Silence: The Hidden Origins of the United Irishmen |publisher=Faber and Faber |year=1993 |isbn=0571154867 |pages=}}</ref>{{rp|pages=49–50}}<ref name="Bardon-2005">Bardon, Jonathan (2005), ''A History of Ulster'', Belfast: The Black Staff Press. {{ISBN|0-85640-764-X}}</ref>{{rp|pages=214–217}} The '']'' survived: the ] aristocracy remained entrenched under the patronage of a government that continued to take its direction from London.<ref>Coquelin, Olivier (2007) : ''From the Enlightenment to the Present'', Olivier Coquelin; Patrick Galliou; Thierry Robin, Nov 2007, Brest, France. pp. 42–52 . ffhal-02387112f</ref> | |||

| [[File:United Irish badge.gif|thumbnail|200px|right|<center>"''Equality — <br>It is new strung and shall be heard''" | |||

| <br> | |||

| ] Symbol<br>] (]) with ] instead of ]]] | |||

| ]'' (]).]] | |||

| === Formation of the United Irishmen === | |||

| Despite their growing strength, the United Irish leadership decided to seek military help from the ] and to postpone the rising until French troops landed in Ireland. ], leader of the United Irishmen, travelled in exile from the United States to France to press the case for intervention. | |||

| {{Main|Society of United Irishmen}} | |||

| The disappointment was felt keenly in ], a growing commercial centre which, as a borough owned of the ], had no elected representation. In October 1791, amidst public celebration of the ], a group of Volunteer veterans invited an address from ], a Protestant secretary to Dublin's ].<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VD4IAAAAQAAJ&q=Life+of+Theobald+Wolfe+Tone |title=Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. I |publisher=Gales and Seaton |year=1826 |editor=William Theobald Wolfe Tone |location=Washington D.C. |pages=141}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=English |first=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=59mOVEg80PYC |title=Irish Freedom: The History of Nationalism in Ireland |date=2007 |publisher=Pan Books |isbn=978-0330427593 |pages=96–98 |language=en}}</ref> Acknowledging his ''Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland,''<ref>{{Cite book |author=Theobald Wolfe Tone |url=https://celt.ucc.ie//published/E790002/index.html |title=An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland |publisher=H. Joy & Co. |year=1791 |location=Belfast}}</ref> in which Tone had argued that they could not enjoy liberty until banded together with Catholics against the "boobies and blockheads" of the Ascendancy, and styling themselves at his suggestion the ],<ref name="Bartlett-2010">{{Cite book |last=Bartlett |first=Thomas |title=Ireland, a History |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2010 |isbn=9780521197205}}</ref>{{rp|207}} the meeting resolved:<blockquote> the weight of English influence in the government of this country is so great as to require a cordial union among all the people of Ireland; that the sole constitutional mode by which this influence can be opposed, is by complete and radical reform of the representation of the people in parliament.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Altholz |first=Josef L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zsnwc3fadxAC |title=Selected Documents in Irish History |publisher=M E Sharpe |year=2000 |isbn=0415127769 |location=New York |pages=70}}</ref></blockquote>The same resolution was carried by Tone's friends in Dublin where, reflecting a larger, more diverse, middle class, the Society united from the outset Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter.<ref name="Durey-1994">{{Cite journal |last=Durey |first=Michael |date=1994 |title=The Dublin Society of United Irishmen and the Politics of the Carey-Drennan Dispute, 1792–1794 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2640053 |journal=The Historical Journal |volume=37 |issue=1 |pages=89–111 |doi=10.1017/S0018246X00014710 |issn=0018-246X |jstor=2640053 |s2cid=143976314}}</ref> | |||

| == |

=== The Catholic Convention === | ||

| With the support and participation of United Irishmen,<ref name="Smyth-1998">{{Cite book |last=Smyth |first=Jim |title=The Men of No Property: Irish Radicals and Popular Politics in the Late Eighteenth Century |publisher=Macmillan Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-333-73256-4 |location=London |pages=}}</ref>{{rp|74–76}} in December 1792 the ] convened a national Catholic Convention. Elected on a broad, head-of-household, franchise, the "Back Lane Parliament" was a direct challenge to the legitimacy of the ] and ]<ref name="Woods-2003">{{Cite journal |last=Woods |first=C. J. |date=2003 |title=The Personnel of the Catholic Convention, 1792–3 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25484204 |journal=Archivium Hibernicum |volume=57 |pages=26–76 |doi=10.2307/25484204 |issn=0044-8745 |jstor=25484204}}</ref> | |||

| Tone's efforts succeeded with the dispatch of the ], and he accompanied a force of 14,000 French veteran troops under ] which arrived off the coast of Ireland at ] in December 1796 after eluding the ]; however, unremitting storms, indecisiveness of leaders and poor seamanship all combined to prevent a landing. The despairing ] remarked; "England has had its luckiest escape since the ]."<ref>* ''The Writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone 1763–98, Volume Two: America, France and Bantry Bay – August 1795 to December 1796'' (Journal entry 26th December 1796) – eds. T W Moody, R B MacDowel and C J Woods, Clarendon Press (USA) ISBN 0-19-822383-8</ref> The French fleet was forced to return home and the veteran army intended to spearhead the invasion of Ireland split up and was sent to fight in other theatres of the ]. | |||

| Anticipating war with the ], ] received a delegation from the convention (including Tone) at ], and the British government pressed the Irish Parliament to match Westminster's ].<ref name="Gill & Macmillan"/>{{rp|296}} This relieved Catholics of most of their remaining civil disabilities and, where (in the counties) Common's seats were contested, allowed those meeting the property qualification to vote. For Parliament itself the ] was retained so that it remained exclusively Protestant.<ref>Patrick Weston Joyce (1910) An Installment on Emancipation p. 867. www.libraryireland.com</ref> | |||

| == Counter-insurgency and repression == | |||

| The Establishment responded to widespread disorders by launching a counter-campaign of ] from 2 March 1797. It used tactics including house burnings, torture of captives, ] and murder, particularly in ] as it was the one area of Ireland where large numbers of Catholics and Protestants (mainly ]) had effected common cause. In May 1797 the military in Belfast also violently suppressed the newspaper of the United Irishmen, the ]. | |||

| For a measure that could have little appreciable impact on the conduct of government, the price for overriding Ascendancy opposition was the dissolution of the Catholic Committee,<ref name="Lee23">{{cite DNB|wstitle=Tone, Theobald Wolfe|volume=57|page=23}}</ref> a new government militia that conscripted Catholic and Protestant by ],<ref name="Bartlett-2010"/>{{rp|209}} and a Convention Act that effectively outlawed extra-parliamentary opposition.<ref>{{cite book |last=Connolly |first=S. J. |title=Oxford Companion to Irish History |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-19-923483-7 |page=611}}</ref> When it was clear that these were not terms acceptable to the United Irishmen (who had been seeking to revive and remodel the Volunteers along the lines of the revolutionary ])<ref>{{Cite book |last=Blackstock |first=Allan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vkayx77nQLQC |title=Double Traitors?: The Belfast Volunteers and Yeomen, 1778–1828 |date=2000 |publisher=Ulster Historical Foundation |isbn=978-0-9539604-1-5 |location=Belfast |pages=11–12 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Garnham |first=Neal |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lB1vsTaIKC4C |title=The Militia in Eighteenth-century Ireland: In Defence of the Protestant Interest |date=2012 |publisher=Boydell Press |isbn=978-1-84383-724-4 |pages=152 |language=en}}</ref> the government moved to suppress the Society. In May 1794, following the revelation of meetings between a French emissary, ], and United leaders including Tone and ], the Society was proscribed.<ref name="Bartlett-2010"/>{{rp|211}} | |||

| ] caricatured the failure of Hoche's expedition.]] | |||

| The British establishment recognised ] as a divisive tool to employ against the Protestant United Irishmen in ] and the '']'' method of colonial dominion was officially encouraged by the Government. Brigadier-General C.E. Knox wrote to ] (who was responsible for Ulster): "I have arranged... to increase the animosity between the Orangemen and the United Irishmen, or liberty men as they call themselves. Upon that animosity depends the safety of the centre counties of the North."<ref>]. A History of England in the Eighteenth Century, Volume VII. D. Appleton And Company, New York, 1890, p. 312.</ref> | |||

| == Mobilisation == | |||

| Similarly, the ], ], wrote to the ] in June 1798, "''In the North nothing will keep the rebels quiet but the conviction that where treason has broken out the rebellion is merely ]''",<ref>Letter to Privy Council, 4 June 1798 "''A Volley of Execrations: the letters and papers of John Fitzgibbon, earl of Clare, 1772–1802''", edited by D.A. Fleming and A.P.W. Malcomson. (2004)</ref> expressing the hope that the Presbyterian republicans might not rise if they thought that rebellion was supported only by Catholics. | |||

| ] | |||

| === New System of Organisation === | |||

| ] across Ireland had organised in support of the Government; many supplied recruits and vital local intelligence through the foundation of the ] in 1795. The Government's founding of ] in the same year, and the French ] earlier in 1798 both helped secure the opposition of the Roman Catholic Church to rebellion; with a few individual exceptions, the Church was firmly on the side of the Crown throughout the entire period of turmoil. | |||

| A year later, in May 1795, a meeting of United delegates from Belfast and the surrounding market towns responded to the growing repression by endorsing a new, and it was hoped more resistant, "system of organisation". Local societies were to split so as to remain within a range of 7 to 35 members, and through baronial and county delegate committees, to build toward a provincial, and, once three of ] had organised, a national, directory.<ref name="Curtin-1993">Curtin, Nancy J. (1993), "United Irish organisation in Ulster, 1795–8", in D. Dickson, D. Keogh and K. Whelan, ''The United Irishmen: Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion,'' Dublin: Lilliput Press, {{ISBN|0946640955}}, pp. 209–222.</ref> | |||

| It was with this New System that the Society spread rapidly across Ulster and, eventually, from Dublin (where the abandonment of open proceedings had been resisted){{sfn|Stewart|1995|p=20}} out into the midlands and the south. As it did so, ]'s ], calling for "a union of power among Irishmen of every religious persuasion",<ref>{{Cite book |title=Belfast politics: or, A collection of the debates, resolutions, and other proceedings of that town in the years 1792, and 1793 |publisher=H. Joy & Co. |year=1794 |editor=William Bruce and Henry Joy |location=Belfast |pages=145}}</ref> was administered to ]s, ] and shopkeepers, many of whom had maintained their own ] clubs,<ref name="McSkimin-1906">{{Cite book |last=McSkimin |first=Samuel |title=Annals of Ulster: from 1790 to 1798 |publisher=Jmes Cleeland, William Mullan & Son |year=1906 |location=Belfast |pages=14–15}}</ref> and to tenant farmers and their market-town allies who had organised against the Protestant ] in secret fraternities.<ref name="Elliott-1993" />{{rp|227–228}} | |||

| In March 1798 intelligence from ] amongst the United Irish caused the Government to sweep up most of their leadership in raids in ] in March 1798. ] was imposed over most of the country and its unrelenting brutality put the United Irish organisation under severe pressure to act before it was too late. A rising in ], County Tipperary broke out in response, but was quickly crushed by the High Sherrif, ]. Militants led by ] and ] dominated the rump United Irish leadership and planned to rise without French aid, fixing the date for 23 May. | |||

| === United Irish–Defender alliance === | |||

| == Outbreak of the rebellion == | |||

| In rural Ireland, there was a "varied, energetic and complex structure of agrarian 'secret societies'", commonly referred to as ], after groups that had emerged mid-century in the south.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Foster |first=R. F. |title=Modern Ireland, 1600–1972 |publisher=Allen Lane, Penguin |year=1988 |isbn=9780713990102 |location=London |pages=222–223}}</ref> In the north, it had included the ] who, mobilising the aggrieved irrespective of religion, had in 1763 threatened to pursue fleeing Anglican rectors and tithe proctors into the ]<ref>Donnelly, James S. Jr. (1981). "Hearts of Oak, Hearts of Steel." ''Studia Hibernica'' 21: 7–73.</ref> There had also been the ] who, protesting land speculation and evictions, in 1770 entered Belfast, besieged the barracks, and sprung one of their number from prison.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bardon |first=Jonathan |title=Belfast: an Illustrated History |publisher=Blackstaff Press |year=1982 |isbn=0856402729 |location=Belfast |pages=34–36}}</ref> By the 1790s, borrowing, like the United Irish societies (and, from 1795, their nemesis the ], from the lodge structure and ceremonial of ],<ref name="CJYJs2">{{Cite journal |last=Rudland |first=David |date=1998 |title=1798 and Freemasonry |url=https://www.historyireland.com/1798-and-freemasonry/ |journal=United Irishmen |volume=6 |issue=4}}</ref><ref>Smyth, J, (1993), "Freemasonry and the United Irishmen", in David Dickson, Daire Keogh and Kevin Whelan eds., ''The United Irishmen, Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion'', pp. 167–174, Dublin, Lilliput, {{ISBN|0946640955}}</ref> this semi-insurrectionary phenomenon had regenerated as the largely but—with some latter-day adjustments to their oaths—not exclusively Catholic, ].<ref name="Curtin-1985">{{Cite journal |last=Curtin |first=Nancy J. |date=1985 |title=The Transformation of the Society of United Irishmen into a Mass-Based Revolutionary Organisation, 1794–6 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/30008756 |journal=Irish Historical Studies |volume=24 |issue=96 |pages=463–492 |doi=10.1017/S0021121400034477 |jstor=30008756 |s2cid=148429477 |issn=0021-1214}}</ref>{{rp|467–477}} | |||

| {{unreferenced|section|date=May 2012}} | |||

| The initial plan was to take ], with the counties bordering Dublin to rise in support and prevent the arrival of reinforcements followed by the rest of the country who were to tie down other garrisons. The signal to rise was to be spread by the interception of the mail coaches from Dublin. However, last-minute intelligence from informants provided the Government with details of rebel assembly points in Dublin and a huge force of military occupied them barely one hour before rebels were to assemble. Deterred by the military, the gathering groups of rebels quickly dispersed, abandoning the intended rallying points, and dumping their weapons in the surrounding lanes. In addition, the plan to intercept the mail coaches miscarried, with only the ]-bound coach halted at ], near ], on the first night. | |||

| Originating as "fleets" of young men who contended with Protestant ] for the control of tenancies and employment in the linen-producing region of north Armagh,<ref name="Furlong-1991">Furlong, Nicholas (1991) ''Fr. John Murphy of Boolavogue 1753–98,'' Dublin, p. 146, {{ISBN|0-906602-18-1}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=McEvoy |first=Brendan |date=1987 |title=The Peep of Day Boys and Defenders in the County Armagh (concluded) |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/29745261 |journal=Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society |volume=12 |issue=2 |pages=60–127 |doi=10.2307/29745261 |jstor=29745261 |issn=0488-0196}}</ref> the Defenders organised across the southern counties of Ulster and into the Irish midlands. Already in 1788, their oath-taking had been condemned in a pastoral by the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McEvoy |first=Brendan |date=1970 |title=Father James Quigley: Priest of Armagh and United Irishman |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/29740772 |journal=Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=247–268 |doi=10.2307/29740772 |issn=0488-0196 |jstor=29740772}}</ref> As the United Irishmen began to reach out the Defenders, they were similarly sanctioned. With cautions against the "fascinating illusions" of French principles, in 1794 Catholics taking the ] were threatened with ].<ref name="Kennedy-1984">{{cite journal |last1=Kennedy |first1=W. Benjamin |date=December 1984 |title=Catholics in Ireland and the French Revolution |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/44210866 |journal=Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia |volume=84 |issue=3/4 |page=222 |jstor=44210866 |access-date=20 January 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Although the planned nucleus of the rebellion had imploded, the surrounding districts of Dublin rose as planned and were swiftly followed by most of the counties surrounding Dublin. The first ] of the rebellion took place just after dawn on 24 May. Fighting quickly spread throughout Leinster, with the heaviest fighting taking place in ] where, despite the Government's successfully beating off almost every rebel attack, the rebels gained control of much of the county as military forces in Kildare were ordered to withdraw to ] for fear of their isolation and destruction as at ]. However, rebel defeats at ] and the ], ], effectively ended the rebellion in those counties. In ], news of the rising spread panic and fear among loyalists; they responded by massacring rebel suspects held in custody at ] and in ]. A baronet, ], was found guilty of leading the rebellion in Carlow and executed for ]. | |||

| Encountering a political outlook more ] than ],<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Morley |first=Vincent |date=2007 |title=The Continuity of Disaffection in Eighteenth-Century Ireland |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/30071497 |journal=Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr |volume=22 |pages=189–205 |doi=10.3828/eci.2007.12 |issn=0790-7915 |jstor=30071497}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kennedy |first=W. Benjamin |date=1974 |title=Catholics in Ireland and the French Revolution |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/44210866 |journal=Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia |volume=85 |issue=3/4 |pages=221–229 |jstor=44210866 |issn=0002-7790}}</ref> and speaking freely to the grievances of tithes, taxes and rents,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McEvoy |first=Brendan |date=1960 |title=The United Irishmen in Co. Tyrone |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/29740719 |journal=Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=1–32 |doi=10.2307/29740719 |issn=0488-0196 |jstor=29740719}}</ref><ref name="Bardon-2005"/>{{rp|pages=229–230}} United agents sought to convince Defenders of something they had only "vaguely" considered, namely the need to separate Ireland from England and to secure its "real as well as nominal independence".<ref name="Elliott-1993">Elliott, Marianne (1993), "The Defenders in Ulster", in David Dickson, Daire Keogh and Kevin Whelan eds., ''The United Irishment, Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion'', (pp. 222–233), Dublin, Lilliput, {{ISBN|0-946640-95-5}}</ref>{{rp|483, 486}} As the promise of reform receded, and as ] built hopes of military assistance, ] and parliamentary reform became a demand for ] (every man a citizen),<ref>R.B. McDowell (ed.) (1942), "Select documents{{snd}}II: United Irish plans of parliamentary reform, 1793" in ''Irish Historical Society'', iii, no. 9 (March), pp. 40–41; Douglas to Mehean, 24 January 1794 (Public Records Office, Home Office, 100/51/98–100); cited in Cronin (1985) p. 465</ref><ref name="McDowell-1944">{{Cite book |last=McDowell |first=R. B. |url= |title=Irish Public Opinion 1750–1800 |publisher=Faber and Faber |year=1944 |edition= |location=London |pages=197–198 |language=English}}</ref> and hopes for accountable government were increasingly represented by the call for an ]—terms that clearly anticipated a violent break with the Crown.<ref name="Curtin-1985" /> | |||

| == The rebellion spreads == | |||

| === Preparation === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Beginning with an obligation of each society to drill a company, and of three companies to form a battalion, the New System of Organisation was adapted to military preparation<ref name="Curtin-1993" /><ref>Graham, Thomas (1993), "A Union of Power: the United Irish Organisation 1795–1798", in David Dickson, Daire Keogh and Kevin Whelan eds., ''The United Irishmen, Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion'', (pp. 243–255), Dublin, Lilliput, {{ISBN|0946640955}}, pp. 246–247</ref> With only ] and ] organised, the leadership remained split between the two provincial directories. In June 1797, they met together in Dublin to consider the demands for an immediate rising from the northerners who, reeling from martial-law seizures and arrests, feared the opportunity to strike was passing. The meeting broke up in disarray, with many of the Ulster delegates fleeing abroad.<ref name="Bew-2011a">{{Cite book |last=Bew |first=John |title=Castlereagh: Enlightenment, War and Tyranny |publisher=Quercus |year=2011 |isbn=978-0857381866 |location=London |pages=96–98}}</ref> The authorities were sufficiently satisfied with the severity of their countermeasures in Ulster that in August they restored civil law in the province.<ref name="Kee-1976">{{Cite book |last=Kee |first=Robert |title=The Most Distressful Country, The Green Flag, Volume 1 |publisher=Quartet Books |year=1976 |isbn=070433089X |location=London |pages=}}</ref>{{rp|88}} | |||

| The initiative passed to the Leinster directory which had recruited two radically disaffected members of the Patriot opposition: ], who brought with him experience of the American war, and ] (later, undistinguished, as an officer of ]'s ]). The directory believed themselves too weak to act in the summer of 1797, but through the winter the movement appeared to strengthen in existing strongholds such as Dublin, ] and ], and to break new ground in the midlands and the south-east.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fagan |first=Patrick |year=1998 |title=Infiltration of Dublin Freemason Lodges by United Irishmen and Other Republican Groups |journal=Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an Dá Chultúr |volume=13 |pages=65–85 |doi=10.3828/eci.1998.7 |jstor=30064326 |s2cid=256149995}}</ref><ref name="Graham-1993a">Graham, Thomas. (1993), "'An Union of Power'? The United Irish organisation, 1795–1798", in D. Dickson, D. Keogh and K. Whelan, ''The United Irishmen: Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion,'' Dublin: Lilliput Press, {{ISBN|0946640955}}, pp. 244–255.</ref> In February 1798, a return prepared by Fitzgerald computed the number United Irishmen, nationwide, at 269,896. But there were doubts as to the number would heed call to arms and whether they could muster more than simple ] (over the previous year the authorities had seized 70,630 of these compared to just 4,183 ]es and 225 ] barrels).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Baines |first=Edward |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vi7lkwlB5QEC&pg=PA225 |title=History of the Wars of the French Revolution ..., Volume 1 |publisher=Longman, Herst, Bees, Orme & Brown |year=1817 |location=London |pages=225}}</ref> While the movement had withstood the government's countermeasures, and seditious propaganda and preparation continued, there was hesitation to act without the certainty of French arms and assistance.<ref name="Graham-1993a" /> | |||

| == Soliciting French, and British-Jacobin, alliances == | |||

| ===Hoche's expedition December 1796 {{anchor|Bantry}}=== | |||

| {{main|French expedition to Ireland (1796)}} | |||

| ] caricatured the failure of Hoche's expedition.]] | |||

| In 1795, from American exile Tone had travelled to Paris where he sought to convince the ] that Ireland was the key to breaking Britain's maritime stranglehold. His "memorials" on the situation in Ireland came to the attention of Director ], and by May, ], the Irish-descendant head of the War Ministry's ''Bureau Topographique'', had drafted an invasion plan. In June, Carnot offered General ] command of an Irish expedition that would secure "the safety of France for centuries to come."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Elliott |first=Marianne |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hxISHyhgrCIC |title=Wolfe Tone |date=2012 |publisher=Liverpool University Press |isbn=978-1-84631-807-8 |pages=280–287 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Originally, it was to have been accompanied by two diversionary raids on England: one against ], the other against ]. In the event, because of pressing demands in Italy, the forty thousand men called for could not be mustered.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Association |first=Waterloo |date=2018-07-26 |title=The Last Invasion of Britain 1797 |url=https://www.waterlooassociation.org.uk/2018/07/26/the-last-invasion-of-britain/ |access-date=2024-04-01 |website=The Waterloo Association |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| Under Hoche, a force of 15,000 veteran troops was assembled at ]. Sailing on 16 December, accompanied by Tone, the French arrived off the coast of Ireland at ] on 22 December 1796. Unremitting storms prevented a landing. Tone remarked that "England had its luckiest escape since the ]".<ref name="Moody-1763">''The Writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone 1763–98, Volume Two: America, France and Bantry Bay – August 1795 to December 1796'' (Journal entry 26 December 1796) – eds. T W Moody, R B MacDowell and C J Woods, Clarendon Press (US) {{ISBN|0-19-822383-8}}</ref> The fleet returned home and the army intended to spearhead the invasion of Ireland was split up and sent, along with a growing ], to fight in other theatres of the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Come |first=Donald R. |date=1952 |title=French Threat to British Shores, 1793–1798 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1982368 |journal=Military Affairs |volume=16 |issue=4 |pages=174–188 |doi=10.2307/1982368 |jstor=1982368 |issn=0026-3931}}</ref> | |||

| Bantry Bay had nonetheless made real the prospect of French intervention, and United societies flooded with new members.<ref name="Bardon-2005"/>{{rp|pages=229–230}} There were increasing reports of Defenders and United Irishmen "marauding" for weapons, and openly parading.<ref name="Kee-1976" />{{rp|86}} In May 1797, Yeomanry, which in the north had begun recruiting entire ],<ref name="Elliott-2000b">{{Cite book |last=Elliott |first=Marianne |title=The Catholics of Ulster, a History |publisher=Allen Lane |year=2000 |isbn=0713994649 |location=London}}</ref>{{rp|245–246}} charged gatherings near ] in ] killing eleven,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=MacDonald |first=Brian |date=2002 |title=Monaghan in the Age of Revolution |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/27699471 |journal=Clogher Record |volume=17 |issue=3 |pages=(751–780) 770 |doi=10.2307/27699471 |issn=0412-8079 |jstor=27699471}}</ref> and in Dundalk killing fourteen.<ref name="Kee-1976" />{{rp|83}} | |||

| === Naval mutinies === | |||

| Seeking to justify the suspension of '']'' in Britain, the authorities were quick to see the hand of both Irish and English radicals in the ] of April and May 1797.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Dugan |first1=James |title=The Great Mutiny |date=1965 |publisher=the Trinity Press |isbn=978-7070012751 |location=London |pages=420–425}}</ref> The United Irish were reportedly behind the resolution of the Nore mutineers to hand the fleet over to the French "as the only government that understands the Rights of Man".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Cole |first1=G. D. H. |title=The Common People, 1746–1938 |last2=Postgate |first2=Raymond |date=1945 |publisher=Methuen & Co. Ltd. |edition=2nd |location=London |page=162}}</ref> Much was made of Valentine Joyce, a leader at Spithead, described by ] as a "seditious Belfast clubist".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Manwaring |first1=George |title=The Floating Republic: An Account of the Mutinies at Spithead and the Nore in 1797 |last2=Dobree |first2=Bonamy |date=1935 |publisher=Geoffrey Bles |location=London |page=101}}</ref> But no evidence emerges of a concerted United Irish plot to subvert the fleet.<ref name="Roger-2003">Roger, N.A.M.(2003), "Mutiny or subversion? Spithead and the Nore", in Thomas Bartlett et al. (eds.), , Four Courts Press, {{ISBN|1851824308}}, pp. 549–564.</ref> There had only been talk of seizing British warships as part of a general insurrection.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Dugan |first1=James |title=The Great Mutiny |date=1965 |publisher=the Trinity Press |isbn=978-7070012751 |location=London |pages=425}}</ref> | |||

| The mutinies had paralysed the British navy, but the ] fleet that the French had prepared for their forces at ] was again opposed by the weather. In October 1797, after Tone and the troops he was to accompany to Ireland had been disembarked, the fleet sought to reach the French naval base at Brest and was destroyed by the Royal Navy at the ].<ref name="Pakenham 19922">{{cite book |last=Pakenham |first=Thomas |url=https://archive.org/details/yearoflibertyhis0000pake_v8o4/mode/2up?view=theater |title=The Year of Liberty – The History of the Great Irish Rebellion of 1798 |publisher=Phoenix |year=1992 |isbn=1-85799-050-1 |edition=Phoenix Paperback |location=London |author-link=Thomas Pakenham (historian) |url-access=registration}}</ref>{{rp|42–45}} <ref>{{Cite web |title=French Expeditions to Ireland 1796–1798 |url=https://www.frenchempire.net/articles/ireland/ |access-date=2023-11-16 |website=www.frenchempire.net}}</ref> | |||

| In Paris, Tone recognised the rising star of ]. But he found the conqueror of Italy incurious about the Irish situation being in need of a war of conquest, not of liberation, to pay his army.<ref name="Fahey-2015">{{Cite news |last=Fahey |first=Denis |date=21 September 2015 |title=An Irishman's Diary on Napoleon and the Irish |url=https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/an-irishman-s-diary-on-napoleon-and-the-irish-1.2357328 |access-date=2023-12-20 |newspaper=The Irish Times |language=en}}</ref> In February 1798, British spies did report that the ] was preparing a fleet in the Channel ports ready for the embarkation of up to 50,000 men,<ref name="Pakenham 19922" />{{rp|31}} but the preparations were soon reversed. Bonaparte deemed both the military and naval forces assembled inadequate to the task. In later exile, he was to claim that he might have made an attempt on Ireland (instead of sailing in May 1798 for Egypt) had he had confidence in Tone the other United Irish agents appearing in Paris. He describes them as divided in opinion and constantly quarrelling.<ref name="Fahey-2015" /> | |||

| === British co-conspiracy === | |||

| These agents from Ireland included ]. A Catholic priest who had been active in bringing Defenders into the movement in Ulster,<ref name="Keogh22">{{cite journal |last1=Keogh |first1=Dáire |date=1998 |title=An Unfortunate Man |url=https://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/an-unfortunate-man/ |journal=18th–19th – Century History |volume=6 |issue=2 |access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> Coigly sought to persuade both French Directory and the leadership in Ireland of a larger project. Beginning in 1796, United Irish agents had helped build networks of United Englishmen and ], societies whose proceedings, oath-taking, and advocacy of physical force "mirrored that of their Irish inspirators".<ref name="Davis United Englishmen2">{{cite ODNB|last1=Davis|first1=Michael|title=United Englishmen|url=https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-95956|year=2008|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/95956|access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> Describing himself as an emissary of the United Irish executive, assisted by a tide of refugees from Ulster,<ref name="McFarland-1994">McFarland, E. W. (1994), ''Ireland and Scotland in the Age of Revolution''. Edinburgh University Press. {{ISBN|978-0748605392}}</ref>{{rp|143–144}} and tapping into protest against the ] and wartime food shortages,<ref name="Elliott3">{{cite journal |last1=Elliott |first1=Marianne |date=May 1977 |title=The 'Despard Plot' Reconsidered |journal=Past & Present |issue=1 |pages=46–61 |doi=10.1093/past/75.1.46}}</ref> Coigly worked from ] to spread the United system across the manufacturing districts of northern England.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Davis |first1=Michael |title=The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest |via=Wiley Online Library |publisher=The International Encyclopaedia of Revolution and Protest |year=2009 |isbn=978-1405198073 |pages=1–2 |chapter=United Englishmen/ United Britons |doi=10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp1500 |access-date=9 November 2020 |chapter-url=https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp1500}}</ref><ref name="Booth2">{{cite journal |last1=Booth |first1=Alan |date=1986 |title=The united Englishmen and Radical Politics in the Industrial North West of England, 1795–1803 |journal=International Review of Social History |volume=31 |issue=3 |pages=271–297 |doi=10.1017/S0020859000008221 |jstor=44582816 |doi-access=free}}</ref> In London, he conferred with Irishmen prominent in the city's federation of democratic clubs, the ]. With these he drew together delegates from Scotland and the provinces who, as "United Britons", resolved "to overthrow the present Government, and to join the French as soon as they made a landing in England".<ref name="Keogh22"/> | |||

| In July 1797, the resolution of the United Britons was discussed by the leadership in Dublin and Belfast. Although addressed to the prospect of a French invasion, the suggestion that "England, Scotland and Ireland are all one people acting for one common cause", encouraged militants to believe that liberty could be won even if "the French should never come here".<ref name="McFarland-1994" />{{rp|184–185}}<ref name="Keogh22"/> | |||

| == The risings == | |||

| {{See also|Society of United Irishmen#1798 Rebellion}} | |||

| === Eve-of-rebellion arrests === | |||

| In early 1798, a series of violent attacks on magistrates in ], ] and ] alarmed the authorities. They were also aware that there was now a faction of the United Irish leadership, led by Fitzgerald and O'Connor, who felt "sufficiently well organised and equipped" to begin an insurgency without French assistance.<ref name="Pakenham 1992">{{cite book |last=Pakenham |first=Thomas |url=https://archive.org/details/yearoflibertyhis0000pake_v8o4/mode/2up?view=theater |title=The Year of Liberty – The History of the Great Irish Rebellion of 1798 |publisher=Phoenix |year=1992 |isbn=1-85799-050-1 |edition=Phoenix Paperback |location=London |author-link=Thomas Pakenham (historian) |url-access=registration}}</ref>{{rp|34–39}} ], ], came under increasing pressure from hardline Irish MPs, led by Speaker ], to crack down on the growing disorder in the south and midlands and arrest the Dublin leadership.<ref name="Pakenham 1992" />{{rp|42}} | |||

| Camden hesitated, partly as he feared a crackdown would itself provoke an insurrection: the British ] ] agreed, describing the proposals as "dangerous and inconvenient".<ref name="Pakenham 1992" />{{rp|42}} The situation changed when an informer, Thomas Reynolds, produced Fitzgerald's report on manpower with its suggestion that over a quarter of a million men across ], ] and ] were preparing to join the "revolutionary army". The Irish government learned from Reynolds that a meeting of the Leinster Provincial Committee and Directory had been set for 10 March in the Dublin house of wool merchant ], where a motion for an immediate rising would be tabled. Camden decided to act, explaining to London that he risked having the Irish Parliament turn against him.<ref name="Pakenham 1992" />{{rp|45}} | |||

| On the 10th, In March 1798, almost the entire committee were seized, along with two directors, the comparative moderates (those who, in the absence of the French, had counselled delay) ] and ], together with all their papers. Meanwhile in England, O'Connor had been arrested alongside Coigly. Having been found in possession of a further address to the French Directory, Coigly was hanged, and the United network he had helped build in Britain was broken up by ].<ref name="Keogh 1998">{{cite journal |last1=Keogh |first1=Daire |date=Summer 1998 |title=An Unfortunate Man |url=https://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/an-unfortunate-man/ |journal=18th–19th Century History |volume=5 |issue=2 |access-date=21 November 2020}}</ref> In Dublin, Fitzgerald went into hiding.<ref name="Pakenham 1992" />{{rp|45–46}} | |||

| The Irish government imposed ] on 30 March, although civil courts continued sitting. Overall command of the army was transferred from ] to ] who turned his attention to Leinster and Munster where from Ulster his troops' reputation for public floggings, half-hanging, pitch-capping and other interrogative refinements preceded him.<ref>{{Cite ODNB|url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/15900|title=Lake, Gerard, first Viscount Lake of Delhi (1744–1808)|last=Bennell|first=Anthony S.|date=2004|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/15900|access-date=15 July 2020}}</ref><ref name="Pakenham 1992" />{{rp|57–58}} | |||

| === The Call from Dublin === | |||

| Faced with the breaking-up of their entire system, Fitzgerald, joined by ] (publisher in Belfast of the Society paper ''],'' recently released from ]), and by ], resolved on a general uprising for 23 May.<ref name="Cullen-1993">Cullen, Louis. (1993), "The internal politics of the United Irishmen", in D. Dickson, D. Keogh and K. Whelan eds., ''The United Irishmen: Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion,'' Dublin: Lilliput Press, {{ISBN|0-946640-95-5}}, (pp. 176–196) pp. 95–96</ref> There was no immediate promise of assistance from France (on the 19th a ] had set sail, under Napoleon, but for Egypt, not Ireland).<ref name="Bartlett-2010"/>{{rp|220}} The United army in Dublin was to seize strategic points in the city, while the armies in the surrounding counties would throw up a cordon and advance into its centre. As soon as these developments were signalled by halting mail coaches from the capital, the rest of the country was to rise.<ref name="Graham-1993b">Graham, Thomas (1993), "A Union of Power: the United Irish Organisation 1795–1798", in David Dickson, Daire Keogh and Kevin Whelan eds., ''The United Irishment, Republicanism, Radicalism and Rebellion'', (pp. 243–255), Dublin, Lilliput, {{ISBN|0946640955}}, pp. 250–253</ref> | |||

| On the appointed day, the rising in the city was aborted. Fitzgerald had been mortally wounded on the 19th, the ] were betrayed the 21st, and on the morning of the 23rd, Neilson, who had been critical to the planning, was seized.<ref name="Graham-1993b"/> Armed with last minute intelligence, a large force of military occupied the rebels' intended assembly points, persuading those who had turned out to dump weapons and disperse. The plan to intercept the mail coaches miscarried, with only the Munster-bound coach halted at ], near ]. The organisation in the outer districts of the city nonetheless rose as planned and were swiftly followed by the surrounding counties.<ref>Graham, Thomas (1996), "Dublin in 1798: The Key to the Planned Insurrection" in ''The mighty wave : the 1798 rebellion in Wexford,'' Dáire Keogh and Nicholas Furlong (eds), pp. 65–78), Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Four Courts Press, {{ISBN|1851822534}}</ref> | |||

| === Leinster === | |||

| {{See also|Wexford Rebellion}} | {{See also|Wexford Rebellion}} | ||

| ]]] | |||

| In ], large numbers rose but chiefly engaged in a bloody rural guerrilla war with the military and loyalist forces. General ] led up to 1,000 men in the Wicklow Hills and forced the British to commit substantial forces to the area until his capitulation in October. | |||

| The first ] of the rebellion took place just after dawn on 24 May in ]. After the Munster mail coach was attacked on its approach to Naas on the night of the 23rd, a 1000 to 3,000 men approached the town. Their pikes could not prevail against ] and steady musket fire. A garrison of less than 200 routed the rebels, with a small cavalry detachment cutting down over a hundred as they fled.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Naas – Kildare Local History |url=https://kildarelocalhistory.ie/a-brief-history-of-co-kildare/1798-rebellion/rebellion-towns-villages/naas/ |access-date=2023-10-27 |website=kildarelocalhistory.ie}}</ref> | |||

| Success did attend a smaller rebel force, commanded by ], a Protestant physician who had deserted from the Yeomanry, later that day at ]. The town was not to be re-occupied until after a rebel ] on 19 June, but a succession of rebel reversals further afield, including defeats at ] (25 May) and of a larger host at the ] in ] (May 26) persuaded many of the Kildare insurgents that their cause was lost.<ref name="Pakenham 1992" />{{rp|124}} | |||

| Rebels were to remain longest in the field in south-east, in Wexford and in the ]. It is commonly suggested that the trigger for the rising in Wexford was the arrival on 26 May of the notorious North Cork Militia.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hay |first=Edward |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hkkTAAAAYAAJ |title=History of the Insurrection of the County of Wexford, A.D. 1798 |publisher=John Stockdale |year=1803 |location=Dublin |pages=57}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Ó hÓgartaigh |first=Margaret |title=Edward Hay: Historian of 1798 |publisher=The History Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-1845889920 |location=Dublin |pages=40–41}}</ref> On 27 May, underestimating the hill-top position and resolve of a rebel party hastily assembled under a local priest, ],<ref name="Swords-1997">Swords, L. (1997) ''Protestant, Catholic, and Dissenter: The Clergy and 1798'', Columbia Press, p. 176</ref> a force of the militia and yeomanry was cut down outside the town of ]. The insurgents then swept south through ] where they released, and gave command to, the local United Irish leader, a Protestant barrister, ]. | |||

| ], 27 May 1798]] | |||

| On 5 June, Bagnel, leading a force of 3,000, failed in an attempt to storm ] whose capture might have opened the way to the large bodies of Defenders known to exist in Kilkenny and Waterford.<ref name="Kee-1976" />{{rp|44}} During and after the battle, government forces systematically killed captured and wounded rebels. On news of the defeat, rebels in the rear killed up to 200 loyalist prisoners (men, women and children): the notorious ].<ref name="gahan">Gahan, D. (1996) , ''History Ireland'', v4:3</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile, attempts to break northward and open a road through Wicklow toward Dublin were checked 1 June at ] and, despite the deployment of guns captured in an ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hay |first=Edward |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=od49AAAAcAAJ |title=History of the Insurrection of the County of Wexford, A. D. 1798: Including an Account of Transactions Preceding that Event, with an Appendix |publisher=John Stockdale |year=1803 |location=Dublin |pages=147 |language=en}}</ref> at ] on 9 June. The rebels fell back toward the south, meeting the survivors of New Ross and forming a camp of 16,000 on ] outside the town of ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Gahan |first=Daniel |date=2013 |title=The Military Strategy of the Wexford United Irishmen in 1798 |url=https://www.historyireland.com/the-military-strategy-of-the-wexford-united-irishmen-in-1798/ |access-date=2023-11-26 |website=History Ireland}}</ref> There, on 21 June, they were surrounded, bombarded and routed by a force of 13,000 under General Lake.<ref name="ODNB2">{{cite ODNB|id=15900|first=Anthony S.|last=Bennell|title=Lake, Gerard, first Viscount Lake of Delhi (1744–1808)}}</ref> | |||

| The remnants of the "Republic of Wexford" established a base in Killaughrim Woods, in the north of the county, under ]. Others sought action elsewhere. On 24 June, 8,000 men converged in two columns led by Father Murphy and by ] on ] in ] where it was hoped the area's militant colliers would join them. Unprepared, the miners did not tip the balance and at the end of the day both garrison and rebels retreated from the burning town.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Battle of Castlecomer |url=https://castlecomer.ie/history/the-battle-of-castlecomer/ |access-date=2023-11-07 |website=Castlecomer |language=en-GB}}</ref> Byrne led his men into the Wicklow Mountains where ] and ] commanded a ] resistance.<ref name="Webb-1878b">{{Cite web |title=Myles Byrne – Irish Biography |url=https://www.libraryireland.com/biography/MylesByrne.php |access-date=2021-03-22 |website=www.libraryireland.com}}</ref> Murphy's men passed into Kildare where, after the priest was captured, they joined rebels withdrawn under ] into the ]. After a number of bruising engagements, the "Wexford croppies" moved into Meath making a last stand at Knightstown bog on 14 July.<ref>{{Cite news |title=Wexford Croppies' Graves In Meath |url=https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/wexford-croppies-graves-in-meath-1.137942 |access-date=2023-10-27 |newspaper=The Irish Times |language=en}}</ref> A few hundred survivors returned to Kildare where at ] they surrendered on the 21st.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Surrender – Kildare Local History . ie |url=https://kildarelocalhistory.ie/a-brief-history-of-co-kildare/1798-rebellion/rebellion-towns-villages/surrender/ |access-date=2023-10-29 |website=kildarelocalhistory.ie}}</ref> | |||

| All but their leaders benefited from an amnesty intended by the new ], ] to flush out remaining resistance. The law was pushed through the Irish Parliament by the Chancellor, ]. A staunch defender of the Ascendancy, Clare was determined to separate Catholics from the greater enemy, "Godless Jacobinism."<ref name="Pakenham 1992" />{{rp|44}} | |||

| === Ulster === | |||

| In the north, there had been no response to the call from Dublin. On 29 May, following news of the fighting in Leinster, county delegates meeting in Armagh, voted out the hesitant Ulster directory and resolved that if the adjutant generals of Antrim and Down could not agree a general plan of insurrection, they would return to their occupations and "deceive the people no more". In response, ], who refused to consider action in the absence of the French, resigned his command in Antrim. Amidst charges of betrayal by aristocrats, cowards and traitors, his colonels turned to the young ]. Fearful that the "hope of a union with the south" was otherwise lost, McCracken proclaimed the First Year of Liberty on 6 June.<ref name="Stewart-1995">] (1995), ''The Summer Soldiers: The 1798 Rebellion in Antrim and Down'' Belfast, Blackstaff Press, 1995,{{ISBN|9780856405587}}.</ref>{{rp|60–67}} | |||

| On 7 June, there were local musters across the county, and west of the ] at ].<ref name="McEvoy-1969">{{Cite journal |last=McEvoy |first=Brendan |date=1969 |title=The United Irishmen in Co. Tyrone |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/29740753 |journal=Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society |volume=5 |issue=1 |pages=(37–65), 52 |doi=10.2307/29740753 |issn=0488-0196 |jstor=29740753}}</ref> The green flag was raised in ], and there were attacks on ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name="Bartlett-2010"/>{{rp|222}} But by the following morning, before any coordination had been possible, those who turned out had begun to dump arms and disperse on news of McCracken defeat. Leading a body of four to six thousand, their commander had failed, with heavy losses, to seize ].<ref name="McCracken-2022">{{Cite book |last=McCracken |first=Stephen |title=The Battle of Antrim – Antrim's Story in 1798 |publisher=Springfarm Publishing |year=2022 |isbn=978-1-9162576-2-7 |edition=2nd Updated |location=Northern Ireland |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| In the north-east, mostly Presbyterian rebels led by ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ulsterhistory.co.uk/henryjoymccracken.htm |title=Henry Joy McCracken - United irishman |publisher=Ulsterhistory.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2012-03-07}}</ref> rose in ] on 6 June. They briefly held most of the county, but the rising there collapsed following ] at ]. In ], after initial success at ], rebels led by ] were defeated in the longest battle of the rebellion at ]. | |||

| From the point of view of the military, the insurrection in County Antrim ended on 9 June with the surrender of Ballymena (under an amnesty that spared it the fate of ], ] and Ballymoney—all set ablaze). A diminishing band under McCracken dispersed when, on the 14th, they received news of the decisive defeat of the Army of the Republic in County Down.<ref name="Stewart-1995" />{{rp|161–162}} | |||

| The rebels had most success in the south-eastern county of ] where they seized control of the county, but a series of bloody defeats at the ], ], and the ] prevented the effective spread of the rebellion beyond the county borders. 20,000 troops eventually poured into Wexford and inflicted defeat at the ] on 21 June. The dispersed rebels spread in two columns through the midlands, ], and finally towards Ulster. The last remnants of these forces fought on until their final defeat on 14 July at the battles of Knightstown Bog, ] and Ballyboughal, ]. | |||

| Plans for a simultaneous rising in Down on the 7th had been disrupted by the arrest of the county's adjutant general, ], and all his colonels. But beginning on the 9th younger officers took the initiative. An ], an attack upon ], and the seizure of guns from a ship in ] harbour, persuaded ] to concentrate his forces for a counteroffensive in Belfast. The republic in north Down, which extended down the ] to ] from which the rebels, under naval fire, were repulsed on the 11th,<ref name="Stewart-1995" />{{rp|190–192}} lasted but three days. Nugent moved on the 12th, and by the morning of the 13th had routed the main rebel conjunction under Dickson's successor, a young Lisburn draper, ], outside ].<ref name="Stewart-1995" />{{rp|179–224}} | |||

| == Atrocities == | |||

| ], 12–13 June 1798|left]] | |||

| ] of suspected ] by government troops.]] | |||

| Stories of Catholic desertion at the ] were common,<ref name="Elliott-2000a">{{Cite book |last=Elliott |first=Marianne |title=The Catholics of Ulster: A History |publisher=Allen Lane |year=2000 |isbn=0713994649 |pages=254–256}}</ref> although a more sympathetic account has ] decamping only after Munro rejected their proposal for a night attack on the riotous soldiery in the town as taking an "ungenerous advantage".<ref name="Proudfoot-1997">Proudfoot L. (ed.) ''Down History and Society'' (Dublin 1997) chapter by Nancy Curtin at p. 289. {{ISBN|0-906602-80-7}}</ref> These were denied by ] who had been one of the principal United emissaries to the Defenders. He insisted that Defenders had not appeared among the rebels in separate ranks, and that the body that deserted Munro on the eve of battle had been "the ] people ... and they were Dissenters".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Madden |first=Richard Robert |url=http://archive.org/details/antrimdownin98li00madd_0 |title=Antrim and Down in '98: the lives of Henry Joy M'Cracken, James Hope, William Putnam M'Cabe, Rev. James Porter, Henry Munro |publisher=Burns Oates & Washbourne Ltd. ... |year=1860 |location=London |pages=240}}</ref> | |||

| Historian ] notes that, in Down, Catholics had a formal parity in the United organisation. Prior to the final arrests, they accounted for three of the county's six colonels. As they dominated only in the southern third of the county this, she suggests, did not reflect a practice of separate Catholic divisions.<ref name="Elliott-2000a" /> | |||

| The intimate nature of the conflict meant that the rebellion at times took on the worst characteristics of a civil war, especially in Leinster. Sectarian resentment was fuelled by the remaining Penal Laws still in force and by the ruthless campaign of repression prior to the rising. Rumours of planned massacres by both sides were common in the days before the rising and led to a widespread climate of fear. Atrocities would be committed by both sides during the rebellion.<ref>Reid, Stuart. ''Armies of the Irish Rebellion 1798'' pg 3, "a campaign marked by atrocities on both sides</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Munster === | ||

| In the southwest, in ], there were just two skirmishes: on 19 June near ] in ], the "]"<ref name="Murphy-1998">{{Cite news |last=Murphy |first=John |date=24 May 1998 |title=We still fear to speak of all the ghosts of '98 |pages=15 |work=Sunday Independent}}</ref> and, after the principal action was over, on 24 July, an attempt to free prisoners at ] in ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Power |first=Patrick |date=1993 |title=Tipperary Courtmartials – 1798 to 1801 |url=https://tipperarystudies.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/18.-Tipperary-Courtmartials-1798-to-1801.pdf |journal=Tipperary Historical Journal |pages=134–147}}</ref> The province had been subject to pacification ten years before: a martial-law regime suppressed a semi-insurrectionary ] agrarian resistance movement.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Donnelly |first1=James S |last2=Donnelly |first2=James J |date=1977–1978 |title=The Rightboy Movement 1785–8 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/20496124 |journal=Studia Hibernica |issue=17/18 |pages=120–202 |jstor=20496124 |access-date=22 November 2020}}</ref> Following the French appearance off Bantry in December 1796, the exercise was repeated. With a license to "treat the people with as much harshness as possible", troops of the line, militia, yeomanry and fencibles, were garrisoned across the region recovering arms, arresting large numbers of United suspects, and dragooning young men into militia service.<ref name="Dickson-2003">Dickson, David (2003), "Smoke without fire? Munster and the 1798 rebellion", in Thomas Bartlett et al. (eds.), , Four Courts Press, {{ISBN|1851824308}}, (pp. 147–173), pp. 168–171.</ref> | |||

| The aftermath of almost every British victory in the rising was marked by the massacre of captured and wounded rebels with some on a large scale such as at Carlow, New Ross, Ballinamuck and Killala.<ref>Stock, Joseph. Dublin & London, 1800</ref> The British were responsible for particularly gruesome massacres at ], ] and ], burning rebels alive in the latter two.<ref>p. 146 "''Fr. John Murphy of Boolavogue 1753–98''" (Dublin, 1991) Nicholas Furlong ISBN 0-906602-18-1</ref> For those rebels who were taken alive in the aftermath of battle, being regarded as traitors to the Crown, they were not treated as prisoners of war but were executed, usually by hanging. | |||

| In May 1797, the entire committee of the relatively strong United organisation that the ] had built in Cork City<ref>{{usurped|1=}}</ref> were arrested. In April 1798, the authorities broke up what remained.<ref name="Dickson-2003" /><ref>{{Cite web |last=Woods |first=C. J. |date=2009 |title=Sheares, Henry {{!}} Dictionary of Irish Biography |url=https://www.dib.ie/biography/sheares-henry-a8013 |access-date=2023-10-27 |website=www.dib.ie |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In addition non-combatant civilians were murdered by the military, who also carried out many instances of rape, particularly in County Wexford.<ref>p. 28, "''The Mighty Wave: The 1798 Rebellion in Wexford''" (Four Courts Press 1996) Daire Keogh (Editor), Nicholas Furlong (Editor) ISBN 1-85182-254-2</ref><ref>Moore, Sir John ''The Diary of Sir John Moore'' p.295 ed. J.F Maurice (London 1904)</ref> Many individual instances of murder were also unofficially carried out by aggressive local Irish ] militia units before, during and after the rebellion as their local knowledge led them to attack suspected rebels. "Pardoned" rebels were a particular target.<ref>p. 113 "''Revolution, Counter-Revolution and Union''" (Cambridge University Press, 2000) Ed. Jim Smyth ISBN 0-521-66109-9</ref> | |||

| The confrontation on 19 June was between a column of Westmeath Militia and a force of 300-400 lightly armed local peasantry, who, according to one account, appealed to the militia men to join their party and were instead met with fire.<ref name="COR">{{cite web |title=The Battle of the Big Cross where one hundred Irish died |url=https://failteromhat.com/southernstar/page17.php |access-date=2 September 2021 |website=failteromhat.com |publisher=Southern Star}}</ref> The ] Catholics were afterwards admonished in their chapel by the town's Protestant vicar for being so "foolish" as "to think that ... country farmers and labourers set up as politicians, reformers, and law makers".<ref name="Murphy-1998"/> | |||

| ===Rebel=== | |||

| Massacres of loyalist prisoners took place at the ] camp and in ]. After the defeat of a rebel attack at ], up to 200 prisoners <ref name="autogenerated274">Lydon, James F. ''The making of Ireland: from ancient times to the present'' pg 274</ref> were forced by the rebels into ] and then burned alive. In ], 70 loyalist prisoners were stripped naked, tied to Wexford bridge and piked to death.<ref name="autogenerated274"/> Rebels sacked the village of ], before rounding up the local civilians to use as human shields against government fire.<ref name="autogenerated274"/> | |||

| == French |

== French epilogue == | ||

| {{See also|Cornwallis in Ireland}} | {{See also|Cornwallis in Ireland}} | ||

| ], 27 August ]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ], in the far west, the poorest of the Irish provinces, was drawn into the rebellion only by the arrival on 22 August of the French. About 1,000 French soldiers under ] landed at ].<ref>{{cite web |title=In Humbert's Footsteps – 1798 & the Year of the French |url=https://www.mayo.ie/library/local-history/historical-events/in-humberts-footsteps |access-date=10 December 2022 |work=Mayo County Library |publisher=Mayo County Council |quote=On 22 August 1798, a French expedition of 1,000 men under the leadership of General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert (b. 1767) landed at Kilcummin, north of Killala}}</ref> Joined by up to 5,000 hastily assembled "uncombed, ragged" and shoeless peasants,<ref>{{Cite web |last=Mayo County Council |title=General Humbert |url=https://www.mayo.ie/discover/history-heritage/great-battles-conflicts/general-humbert |access-date=2023-11-11 |website=MayoCoCo |language=en}}</ref> they had some initial success. In what would later become known as the "Races of Castlebar" they set to flight a militia force of 6,000 under ].<ref name="Beiner-2007">], ''Remembering the Year of the French: Irish Folk History and Social Memory'' (University of Wisconsin Press, 2007)</ref> | |||

| In the wake of the victory, Humbert proclaimed the ] with the French-educated ] as president of the government of Connacht. But unable to make timely contact with a new rising sparked in ] and ], after a token engagement with British forces of some 26,000 at ], in County Longford, Humbert surrendered on 8 September, along with 500 Irish under ]. | |||

| On 22 August, nearly two months after the main uprisings had been defeated, about 1,000 French soldiers under ] landed in the north-west of the country, at ] in ]. Joined by up to 5,000 local rebels, they had some initial success, inflicting a humiliating defeat on the British at the ] (also known as the ''Castlebar races'' to commemorate the speed of the retreat) and setting up a short-lived "]". This sparked some supportive risings in Longford and Westmeath which were quickly defeated, and the main force was defeated at ], in ], on 8 September 1798. The French troops who surrendered were repatriated to ] in exchange for British ], but hundreds of the captured Irish rebels were executed. This episode of the 1798 Rebellion became a major event in the heritage and collective memory of the West of Ireland and was commonly known in Irish as {{lang|ga|''Bliain na bhFrancach''}} and in English as "The Year of the French".<ref>], ''Remembering the Year of the French: Irish Folk History and Social Memory'' (University of Wisconsin Press, 2007).</ref> | |||

| What was recalled in the ] region as {{lang|ga|Bliain na bhFrancach}} (the year of the French),<ref name="Beiner-2007" /> concluded with slaughter of some 2000 poorly-armed insurgents outside Killala on the 23rd. They had been led by a scion of Mayo's surviving Catholic gentry, James Joseph MacDonnell.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Woods |first=C. J. |date=2009 |title=MacDonnell, James Joseph {{!}} Dictionary of Irish Biography |url=https://www.dib.ie/biography/macdonnell-james-joseph-a5185 |access-date=2023-01-23 |website=www.dib.ie |language=en}}</ref> Terror ensued with ], ] (the future ]) earning the nickname ''Donnchadh an Rópa'' (Denis the Rope).<ref>{{Cite web |last=Quinn |first=James |date=2009 |title=Browne, Denis {{!}} Dictionary of Irish Biography |url=https://www.dib.ie/biography/browne-denis-a1021#:~:text=Browne%20served%20as%20an%20officer,returned%20for%20Castlebar%20in%201797). |access-date=2023-11-11 |website=www.dib.ie |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| On 12 October 1798, a larger French force consisting of 3,000 men, and including Wolfe Tone himself, attempted to land in ] near ]. They were intercepted by a larger Royal Navy ], and finally surrendered after a ] without ever landing in Ireland. Wolfe Tone was tried by court-martial in Dublin and found guilty. He asked for death by firing squad, but when this was refused, Tone cheated the hangman by slitting his own throat in prison on 12 November, and died a week later. | |||

| ], 12 October 1798, painted by ]|left]] | |||

| To Tone's dismay, the ] concluded from Humbert's account of his misadventure that the Irish were to be compared with the devoutly Catholic peasantry they had battled at home in the ]. He had to rebuff the suggestion that, rather than a secular republic, he consider a restoration of the ] Pretender, ], as Henry IX, ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Pittock |first=Murray GH |date=2006 |title=Poetry and Jacobite Politics in Eighteenth-Century Britain and Ireland |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=9780521030274}}</ref>{{rp|210}} | |||

| On 12 October, Tone was aboard a second French expedition, carrying a force of 3,000 men, that was intercepted off the coast of ], the ]. Taken captive, Tone regretted nothing done "to raise three million of my countrymen to the ranks of citizen," and lamented only those "atrocities committed on both sides" during his exile.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harwood |first=Philip |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rAcwAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA235 |title=History of the Irish Rebellion |publisher=Chapman & Elcoate |year=1844 |location=London |pages=235}}</ref> On the eve of execution, he cut his own throat.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=O'Donnell |first=Patrick |date=1997 |title=Wolfe Tone's death: Suicide or assassination?: Commandant Patrick O'Donnell (Ret'd.) |url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF02939781 |journal=Irish Journal of Medical Science |language=en |volume=166 |issue=1 |pages=57–59 |doi=10.1007/BF02939781 |pmid=9057437 |s2cid=35311754 |issn=0021-1265}}</ref> | |||

| == Human toll == | |||

| === Casualties === | |||