| Revision as of 10:28, 18 June 2012 view sourceMadGeographer (talk | contribs)19,930 edits Undid revision 498137420 by Pass a Method (talk), clearly undue← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:36, 16 January 2025 view source Omnipaedista (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers242,962 edits style fix per MOS:SECTIONORDER | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Continent}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{About|the continent}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}}{{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox Continent | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2024}} | |||

| |title = Europe | |||

| {{Use British English|date=November 2024}} | |||

| |image = ] | |||

| {{CS1 config|mode=cs1}} | |||

| |area = {{convert|10,180,000|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}{{Cref2|o|1}} | |||

| |population = 739,165,030{{Cref2|o|2}} (2011), ]) | |||

| {{Infobox continent | |||

| |density = 72.5/km<sup>2</sup> | |||

| | title = Europe | |||

| |demonym = ] | |||

| | image = {{Switcher|]|Show national borders|]|Hide national borders|default=1}} | |||

| |countries = 50 | |||

| | area = {{Convert|10,186,000|km2}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/largest-countries-in-europe|title=Largest Countries In Europe 2020|website=worldpopulationreview.com|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=8 July 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220708182613/https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/largest-countries-in-europe|url-status=live}}</ref> (]){{ref label|footnote_a|a}} | |||

| |list_countries = List of sovereign states and dependent territories in Europe|List of European countries | |||

| | population = {{UN_Population|Europe}} ({{UN_Population|Year}}; ]){{UN_Population|ref}} | |||

| |languages = ] | |||

| | density = 72.9/km<sup>2</sup> (188/sq mi) (2nd) | |||

| |time = ] to ] | |||

| | GDP_PPP = {{nowrap|$33.62 trillion (2022 est; ])<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPGDP@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD|title=GDP PPP, current prices|publisher=International Monetary Fund|date=2022|access-date=16 January 2022|archive-date=22 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210122001107/https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPGDP@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD|url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| |internet = ] (]) | |||

| | GDP_nominal = $24.02 trillion (2022 est; ])<ref>{{cite web|title=GDP Nominal, current prices|url=https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD|publisher=International Monetary Fund|date=2022|access-date=16 January 2022|archive-date=25 February 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170225211431/https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |cities = ] | |||

| | GDP_per_capita = $34,230 (2022 est; ]){{ref label|footnote_c|c}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD|title=Nominal GDP per capita|publisher=International Monetary Fund|date=2022|access-date=16 January 2022|archive-date=11 January 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200111084550/https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | HDI = {{increase}} 0.845<ref>{{cite web|url=http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2011/|title=Reports |website=Human Development Reports |access-date=21 July 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120709095716/http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2011/|archive-date=9 July 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| | religions = {{unbulleted list | |||

| | ] (76.2%)<ref name="Survey"/> | |||

| | ] (18.3%)<ref name="Survey"/> | |||

| | ] (4.9%)<ref name="Survey"/> | |||

| | ] (0.6%)<ref name="Survey"/> | |||

| }} | |||

| | demonym = ] | |||

| | countries = ] (])<!-- Note: The smaller figure denotes the number of European countries as defined by the United Nations geoscheme. The greater figure indicates the inclusion of several transcontinental countries and European countries in political and/or cultural geography. --><br />] (])<!-- Note: The greater figure indicates the inclusion of European de facto states in political and/or cultural geography. --> | |||

| | dependencies = ] (])<!-- Note: External territories are country-like dependencies. The greater figure indicates the inclusion of Akrotiri and Dhekelia. --><br />] (])<!-- Note: Internal territories are areas of special sovereignty which form a constituent part of their sovereign state. --> | |||

| | languages = ]: {{hlist | |||

| <!-- Note: according to ], ordered by number of L1 speakers. --> | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| }} | |||

| | time = ]<!--Azores--> to ]<!--Russia--> | |||

| | cities = ]:{{hlist | |||

| <!-- Note: 10 largest urban areas only, ranked by the total population of the conurbation. Please do not modify the list per your own original research. The list must be sourced from a single cited aggregate source. --> | |||

| <!--1-->|]<!--17.9 million--> | |||

| <!--2-->|]<!--14.4.million-->{{ref label|footnote_b|b}} | |||

| <!--3-->|]<!--11.1 million--> | |||

| <!--4-->|]<!--10.8 million--> | |||

| <!--5-->|]<!--6.8 million--> | |||

| <!--6-->|]-]<!--6.8 million--> | |||

| <!--7-->|]<!--5.7 million--> | |||

| <!--8-->|]<!--4.5 million--> | |||

| <!--9-->|]<!--4.3 million--> | |||

| <!--10-->|]<!--4.3 million--><ref name="Urban">{{cite web|url=http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf|title=Demographia World Urban Areas|publisher=Demographia|access-date=28 October 2020|archive-date=3 May 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180503021711/http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| | m49 = <code>150</code> – Europe<br /><code>001</code> – ] | |||

| | footnotes = {{unbulleted list|style=font-size:90%; | |||

| |a. {{note|footnote_a}} Figures include only European portions of transcontinental countries.{{cref2|n|1}} | |||

| |b. {{note|footnote_b}} Includes Asian population. Istanbul is a transcontinental city which straddles both Asia and Europe. | |||

| |c. {{note|footnote_c}} "Europe" as defined by the International Monetary Fund}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Europe''' |

'''Europe''' is a ]{{cref2|t}} located entirely in the ] and mostly in the ]. It is bordered by the ] to the north, the ] to the west, the ] to the south, and ] to the east. Europe shares the ] of ] with Asia, and of ] with both ] and Asia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Europe|title=Europe|publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=30 March 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190330175836/https://www.britannica.com/place/Europe|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=Europe: Human Geography {{!}} National Geographic Society |url=https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/europe-human-geography/ |access-date=2023-02-04 |website=education.nationalgeographic.org}}</ref> Europe is commonly considered to be ] by the ] of the ], the ], the ], the ], the ], and the waterway of the ].<ref name="NatlGeoAtlas">{{Cite book|title=National Geographic Atlas of the World|edition=7th|year=1999|location=Washington, DC|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-7922-7528-2}} "Europe" (pp. 68–69); "Asia" (pp. 90–91): "A commonly accepted division between Asia and Europe ... is formed by the Ural Mountains, Ural River, Caspian Sea, Caucasus Mountains, and the Black Sea with its outlets, the Bosporus and Dardanelles."</ref> | ||

| Europe covers approx. {{Convert|10,186,000|km2}}, or 2% of ] (6.8% of Earth's land area), making it the second-smallest continent (using the ]). Politically, Europe is divided into about ], of which ] is the ] and ], spanning 39% of the continent and comprising 15% of its population. Europe had a ] of about {{#expr:{{formatnum:{{UN_Population|Europe}}|R}}/1e6 round 0}} million (about 10% of the ]) in {{UN_Population|Year}}; the ] after Asia and Africa.{{UN_Population|ref}} The ] is affected by warm Atlantic currents, such as the ], which produce a ], tempering winters and summers, on much of the continent. Further from the sea, seasonal differences are more noticeable producing more ]s. | |||

| Europe is the world's ] continent by surface area, covering about {{convert|10,180,000|km2|sqmi}} or 2% of the Earth's surface and about 6.8% of its land area. Of Europe's approximately 50 states, ] is by far the largest by both area and population, taking up 40% of the continent (although the country has territory in both Europe and Asia), while the ] is the smallest. Europe is the third-most populous continent after Asia and ], with a ] of 733 million or about 11% of the ].<ref>"". Migration News. January 2010 Volume 17 Number 1.</ref> | |||

| The ] consists of a range of national and regional cultures, which form the central roots of the wider ], and together commonly reference ] and ], particularly through ], as crucial and shared roots.<ref>{{harvnb|Lewis|Wigen|1997|page=226}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Kim|last=Covert|title=Ancient Greece: Birthplace of Democracy|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KVMYJNvUiYkC&pg=PP5|year=2011|publisher=Capstone|isbn=978-1-4296-6831-6|page=5|quote=Ancient Greece is often called the cradle of western civilization. ... Ideas from literature and science also have their roots in ancient Greece.|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=27 July 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220727133725/https://books.google.com/books?id=KVMYJNvUiYkC&pg=PP5|url-status=live}}</ref> Beginning with the ] in 476 CE, ] of Europe in the wake of the ] marked the European ] ]. The ] spread in the continent a ] interest in ] and ] which led to the ]. Since the ], led by ] and ], Europe played a predominant role in global affairs with multiple explorations and conquests around the world. Between the 16th and 20th centuries, ] at various times the ], almost all of Africa and ], and the majority of Asia. | |||

| Europe, in particular ], is the birthplace of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Lewis|Wigen|1997|page=226}}</ref> It played a predominant role in global affairs from the 15th century onwards, especially after the beginning of ]. Between the 16th and 20th centuries, European nations controlled at various times ], ], ], and large portions of Asia. Both ]s were largely focused upon Europe, greatly contributing to a decline in ]an dominance in world affairs by the mid-20th century as the ] and ] took prominence.<ref name="natgeo 534">National Geographic, 534.</ref> During the ], Europe was divided along the ] between ] in the west and the ] in the east. ] led to the formation of the ] and the ] in ], both of which have been expanding eastward since the ] in 1991. | |||

| The ], the ], and the ] shaped the continent culturally, politically, and economically from the end of the 17th century until the first half of the 19th century. The ], which began in ] at the end of the 18th century, gave rise to radical economic, cultural, and social change in ] and eventually the wider world. Both ]s began and were fought to a great extent in Europe, contributing to a decline in Western European dominance in world affairs by the mid-20th century as the ] and the ] took prominence and competed over dominance in Europe and globally.<ref name="natgeo 534">National Geographic, 534.</ref> The resulting ] divided Europe along the ], with ] in the ] and the ] in the ]. This divide ended with the ], the ], and the ], which allowed ] to advance significantly. | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| {{Further|List of countries spanning more than one continent}} | |||

| {{Further|Borders of the continents}} | |||

| ]' world map]] | |||

| ] from 1472 showing the division of the world into 3 continents]] | |||

| ]'' map from ]. The British Isles and Scandinavia are not included in Europe proper.]] | |||

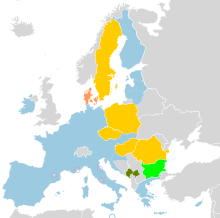

| European integration has been advanced institutionally since 1948 with the founding of the ], and significantly through the realisation of the ] (EU), which represents today the majority of Europe.<ref name="europaeu 1945-59">{{Cite web |title=History of the European Union 1945–59 |url=https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/history-eu/1945-59_en |access-date=16 April 2022 |website=european-union.europa.eu |language=en |archive-date=23 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220423212328/https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/history-eu/1945-59_en |url-status=live }}</ref> The European Union is a ] political entity that lies between a ] and a ] and is based on a system of ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ies.ee/iesp/No11/articles/03_Gabriel_Hazak.pdf|title=The European union—a federation or a confederation?|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=19 March 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220319194121/https://www.ies.ee/iesp/No11/articles/03_Gabriel_Hazak.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> The EU originated in ] but has been ] since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. A majority of its members have adopted a common currency, the ], and participate in the ] and a ]. A large bloc of countries, the ], have also abolished internal border and immigration controls. ] take place every five years within the EU; they are considered to be the second-largest democratic elections in the world after ]. The EU is the third-largest economy in the world. | |||

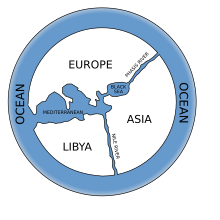

| The use of the term "Europe" has developed gradually throughout history.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=The myth of continents: a critique of metageography| first=Martin W.|last= Lewis|first2= Kären|last2= Wigen|year= 1997|isbn= 0-520-20743-2|publisher=University of California Press|ref=harv}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=The European culture area: a systematic geography|first=Terry G.|last= Jordan-Bychkov| first2=Bella Bychkova|last2= Jordan| publisher=]|year= 2001|isbn=0-7425-1628-8}}</ref> In antiquity, the Greek historian ] mentioned that the world had been divided by unknown persons into three parts, Europe, Asia, and Libya (Africa), with the ] and the ] forming their boundaries—though he also states that some considered the ], rather than the Phasis, as the boundary between Europe and Asia.<ref>Herodotus, 4:45</ref> Europe's eastern frontier was defined in the 1st century by geographer ] at the ]<ref>Strabo ''Geography 11.1''</ref> ] and the '']'' described the continents as the lands given by ] to his three sons; Europe was defined as stretching from the ] at the ], separating it from ], to the ], separating it from ].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Genesis and the Jewish antiquities of Flavius Josephus|first= Thomas W.|last= Franxman|publisher=Pontificium Institutum Biblicum|year= 1979|isbn=88-7653-335-4|pages=101–102}}</ref> | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| A cultural definition of Europe as the lands of ] coalesced in the 8th century, signifying the new cultural condominium created through the confluence of Germanic traditions and Christian-Latin culture, defined partly in contrast with ] and ], and limited to northern Iberia, the British Isles, France, Christianized western Germany, the Alpine regions and northern and central Italy.<ref>], ''The Civilization of the Middle Ages'', 1993, ""Culture and Society in the First Europe", pp185ff.</ref> The concept is one of the lasting legacies of the ]: "Europa" often figures in the letters of Charlemagne's cultural minister, ].<ref>Noted by Cantor, 1993:181.</ref> This division—as much cultural as geographical—was used until the ], when it was challenged by the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Lewis|Wigen|1997|pp=23–25}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=jrVW9W9eiYMC&pg=PA8&dq=%22suggested+that+Europe%27s+boundary%22 |title=Europe: A History, by Norman Davies, p. 8 |publisher=|date= |accessdate=2010-08-23|isbn=978-0-19-820171-7|year=1996|author1=Davies|first1=Norman}}</ref>{{why?|how did age of discovery challenge notion of Europe?|date=December 2011}} The problem of redefining Europe was finally resolved in 1730 when, instead of waterways, the Swedish geographer and cartographer ] proposed the ] as the most significant eastern boundary, a suggestion that found favour in ] and throughout Europe.<ref>{{harvnb|Lewis|Wigen|1997|pp=27–28}}</ref> | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| Europe is now generally defined by geographers as the westernmost ] of Eurasia, with its boundaries marked by large bodies of water to the north, west and south; Europe's limits to the far east are usually taken to be the Urals, the ], and the ]; to the south-east, including the ], the ] and the waterways connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean Sea.<ref name="Encarta">{{cite encyclopedia|last=Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopaedia 2007|title=Europe|url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopaedia_761570768/Europe.html|accessdate=27 December 2007|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5kwbxqnne|archivedate=31 October 2009|deadurl=yes}}</ref> Because of sociopolitical and cultural differences, there are various descriptions of Europe's boundary. For example, ] is approximate to ], but is usually considered part of Europe and currently is a member state of the EU. In addition, ] was considered an island of North Africa for centuries,<ref>Falconer, William; Falconer, Thomas. , BiblioLife (BiblioBazaar), 1872. (1817.), p 50, ISBN 1-113-68809-2 ''These islands Pliny, as well as Strabo and Ptolemy, included in the African sea''</ref> while ], though nearer to ] (North America), is also generally included in Europe. | |||

| {{Anchor|Etymology}} | |||

| {{Further|Europa (consort of Zeus)}} | |||

| ] made by ] of the 6th century BCE, dividing the known world into three large landmasses, one of which was named Europe]] | |||

| The place name Evros was first used by the ancient Greeks to refer to their northernmost province, which bears the same name today. The principal river there – Evros (today's ]) – flows through the fertile valleys of ],<ref>{{cite web | url=https://archive.org/details/dr_qrakh-thraciae-veteris-typus-ex-conatibus-geographicis-abrah-ortelij-cu-10001403 | title=Qrakh. Thraciae Veteris Typus. Ex conatibus Geographicis Abrah. Ortelij. Cum Imp. Et Belgico privilegio decennali. 1585. | date=15 February 1585 }}</ref> which itself was also called Europe, before the term meant the continent.<ref name="BBC News 2013 o022">{{cite web | title=Greek goddess Europa adorns new five-euro note | website=BBC News | date=2013-01-10 | url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-20970684 | access-date=2024-03-21}}</ref> | |||

| Sometimes, the word 'Europe' is used in a geopolitically limiting way<ref>See, e.g., Merje Kuus, ''Progress in Human Geography'', Vol. 28, No. 4, 472–489 (2004), József Böröcz, , ''Comparative Studies in Society and History'', 110–36, 2006, or , Budapest: Central European University Press, 2006.</ref> to refer only to the European Union or, even more exclusively, a culturally defined core. On the other hand, the ] has 47 member countries, and only 27 member states are in the EU.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.coe.int/T/e/Com/about_coe/|title=About the Council of Europe|publisher=Council of Europe|accessdate=9 June 2008 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080516024649/http://www.coe.int/T/e/Com/about_coe/ <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate = 16 May 2008}}</ref> In addition, people living in insular areas such as ], the ], the ] and ] islands and also in ] may routinely refer to ] simply as Europe or "the Continent".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wordnet.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=europe|title=Europe — Noun|publisher=Princeton University|accessdate=9 June 2008}} {{Dead link|date=September 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> | |||

| In classical ], ] ({{langx|grc|Εὐρώπη}}, {{transliteration|grc|Eurṓpē}}) was a ]n princess. One view is that her name derives from the ] elements {{lang|grc|εὐρύς}} ({{transliteration|grc|eurús}}) 'wide, broad', and {{lang|grc|ὤψ}} ({{transliteration|grc|ōps}}, ] {{lang|grc|ὠπός}}, {{transliteration|grc|ōpós}}) 'eye, face, countenance', hence their composite {{transliteration|grc|Eurṓpē}} would mean 'wide-gazing' or 'broad of aspect'.<ref name="WestWest2007">{{cite book|author1=M. L. West|first2=Morris|last2=West|title=Indo-European Poetry and Myth|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZXrJA_5LKlYC|date= 2007|publisher=OUP Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-928075-9|page=185|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=22 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210122123919/https://books.google.com/books?id=ZXrJA_5LKlYC|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="FitzRoy2015">{{cite book|first=Charles|last=FitzRoy|title=The Rape of Europa: The Intriguing History of Titian's Masterpiece|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zhF0BgAAQBAJ&pg=PT52|date=2015|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|isbn=978-1-4081-9211-5|pages=52–|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=20 March 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220320035838/https://books.google.com/books?id=zhF0BgAAQBAJ&pg=PT52|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Astour1967">{{cite book|first=Michael C.|last=Astour|title=Hellenosemitica: An Ethnic and Cultural Study in West Semitic Impact on Mycenaean Greece|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NMkUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA128|year=1967|publisher=Brill Archive|page=128|id=GGKEY:G19ZZ3TSL38|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=20 March 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220320014449/https://books.google.com/books?id=NMkUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA128|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=etymonline>{{cite web|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=Europe|title=Europe – Origin and meaning of the name Europe by Online Etymology Dictionary|website=www.etymonline.com|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=17 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170917144349/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=Europe|url-status=live}}</ref> ''Broad'' has been an ] of Earth herself in the reconstructed ] and the poetry devoted to it.<ref name="WestWest2007"/> An alternative view is that of ], who has argued in favour of a pre-Indo-European origin for the name, explaining that a derivation from {{transliteration|grc|eurus}} would yield a different ] than Europa. Beekes has located toponyms related to that of Europa in the territory of ancient Greece, and localities such as that of ] in ].<ref name="Beekes">{{cite journal |last1=Beekes |first1=Robert |title=Kadmos and Europa, and the Phoenicians |journal=Kadmos |date=2004 |volume=43 |issue=1 |pages=168–69 |doi=10.1515/kadm.43.1.167 |s2cid=162196643 |url=https://www.robertbeekes.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/b118.pdf |access-date=30 July 2022 |archive-date=1 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211101121039/https://www.robertbeekes.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/b118.pdf |url-status=live |issn=0022-7498 }}</ref> | |||

| <center> | |||

| <div class="thumbinner"><div class="overflowbugx" style="overflow: auto;"> | |||

| There have been attempts to connect {{transliteration|grc|Eurṓpē}} to a Semitic term for ''west'', this being either ] {{transliteration|akk|erebu}} meaning 'to go down, set' (said of the sun) or ] {{transliteration|phn|'ereb}} 'evening, west',<ref name=etymonline/> which is at the origin of ] {{transliteration|ar|maghreb}} and ] {{transliteration|he|ma'arav}}. ] stated that "phonologically, the match between Europa's name and any form of the Semitic word is very poor",<ref>{{Cite book |author=M. L. West |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fIp0RYIjazQC&pg=PA451 |title=The east face of Helicon: west Asiatic elements in Greek poetry and myth |publisher=Clarendon Press |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-19-815221-7 |location=Oxford |page=451}}.</ref> while Beekes considers a connection to Semitic languages improbable.<ref name="Beekes"/> | |||

| <small>Clickable map of Europe, showing one of the most commonly used ]<ref>The map shows one of the most commonly accepted delineations of the geographical boundaries of Europe, as used by ] and ]. Whether countries are considered in Europe or Asia can vary in sources, for example in the classification of the ] or that of the ]. Note also that certain countries in Europe, such as France, have ], but which are nevertheless considered integral parts of that country.</ref> <br/>'''Key:''' <span style="color:blue">'''blue'''</span>: ]; | |||

| <span style="color:green">'''green'''</span>: states not geographically in Europe, but closely associated politically<ref>] as part of Denmark, ] as member of the ], ] as member of the ]</ref> | |||

| Most major world languages use words derived from {{transliteration|grc|Eurṓpē}} or ''Europa'' to refer to the continent. Chinese, for example, uses the word {{transliteration|zh|pinyin|Ōuzhōu}} ({{lang|zh-Hant|歐洲}}/{{lang|zh-Hans|欧洲}}), which is an abbreviation of the transliterated name {{transliteration|zh|pinyin|Ōuluóbā zhōu}} ({{lang|zh|歐羅巴洲}}) ({{transliteration|zh|pinyin|zhōu}} means "continent"); a similar Chinese-derived term {{nihongo||欧州|Ōshū}} is also sometimes used in Japanese such as in the Japanese name of the European Union, {{nihongo||欧州連合|Ōshū Rengō}}, despite the ] {{nihongo||ヨーロッパ|Yōroppa}} being more commonly used. In some Turkic languages, the originally Persian name {{transliteration|fa|]}} ("land of the ]") is used casually in referring to much of Europe, besides official names such as {{transliteration|fa|Avrupa}} or {{transliteration|fa|Evropa}}.<ref name="davison">{{Cite journal|author=Davidson, Roderic H. |s2cid=157454140|title=Where is the Middle East?|jstor=20029452 |journal=Foreign Affairs |volume=38|issue=4 |pages=665–675 |year=1960|doi=10.2307/20029452 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| {{Further|Boundaries between the continents#Asia and Europe}} | |||

| {{See also|List of transcontinental countries}} | |||

| ===Contemporary definition=== | |||

| <div class="center"> | |||

| <div class="thumbinner overflowbugx" style="overflow:auto;"> | |||

| <small>Clickable map of Europe, showing one of the most commonly used ]{{cref2|u}} <br />'''Key:''' <span style="color:blue">'''blue'''</span>: ]; | |||

| <span style="color:green">'''green'''</span>: countries not geographically in Europe, but closely associated with the continent | |||

| </small> | </small> | ||

| < |

</div> | ||

| {{Europe and |

{{Europe and seas labelled map}} | ||

| </ |

</div> | ||

| </div></div> | |||

| </center> | |||

| The prevalent definition of Europe as a geographical term has been in use since the mid-19th century. | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| Europe is taken to be bounded by large bodies of water to the north, west and south; Europe's limits to the east and north-east are usually taken to be the ], the ], and the ]; to the south-east, the ], the ], and the waterways connecting the Black Sea to the ].<ref name="Encarta">{{cite encyclopedia |encyclopedia=Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopaedia 2007 |title=Europe |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopaedia_761570768/Europe.html |access-date=27 December 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091028013857/http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761570768/Europe.html |archive-date=28 October 2009 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] printed by ] in 1472, showing the three continents as domains of the sons of ] – Asia to Sem (]), Europe to Iafeth (]) and Africa to Cham (])]] | |||

| ] on a Greek vase. Tarquinia Museum, circa 480 BC]] | |||

| In ancient ], ] was a ]n princess whom ] abducted after assuming the form of a dazzling white bull. He took her to the island of ] where she gave birth to ], ] and ]. For ], Europe ({{lang-grc|Εὐρώπη}}, ''{{Unicode|Eurṓpē}}''; see also ]) was a mythological queen of Crete, not a geographical designation. Later, ''Europa'' stood for ], and by 500 BC its meaning had been extended to the lands to the north. | |||

| Islands are generally grouped with the nearest continental landmass, hence ] is considered to be part of Europe, while the nearby island of Greenland is usually assigned to ], although politically belonging to Denmark. Nevertheless, there are some exceptions based on sociopolitical and cultural differences. Cyprus is closest to ] (or Asia Minor), but is considered part of Europe politically<ref>{{Citation |title=Cyprus |date=2024-08-07 |work=The World Factbook |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/cyprus/ |access-date=2024-08-13 |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency |language=en}}</ref> and it is a member state of the EU. Malta was considered an island of ] for centuries, but now it is considered to be part of Europe as well.<ref>Falconer, William; Falconer, Thomas. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170327020614/https://books.google.com/books?id=B3Q29kWRdtgC&pg=PA50 |date=2017 }}, BiblioLife (BiblioBazaar), 1872. (1817.), p. 50, {{ISBN|1-113-68809-2}} ''These islands Pliny, as well as Strabo and Ptolemy, included in the African sea''</ref> "Europe", as used specifically in ], may also refer to ] exclusively.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=europe|title=Europe – Noun|publisher=Princeton University|access-date=9 June 2008|archive-date=15 July 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140715121246/http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=europe|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The name of ''Europa'' is of uncertain etymology.<ref>Minor theories, such as the (probably folk-etymological) one deriving Europa from εὐρώς (''gen''.: εὐρῶτος) "mould" aren't discussed in the section</ref> One theory suggests that it is derived from the ] εὐρύς (''eurus''), meaning "wide, broad"<ref>, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', on Perseus</ref> and ὤψ/ὠπ-/ὀπτ- (''ōps''/''ōp''-/''opt-''), meaning "eye, face, countenance",<ref>, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', on Perseus</ref> hence ''{{Unicode|Eurṓpē}}'', "wide-gazing", "broad of aspect" (compare with ] or ]). ''Broad'' has been an ] of ] itself in the reconstructed ].<ref>{{Cite book|author=M. L. West |title=Indo-European poetry and myth |publisher=] |location=Oxford |year=2007 |pages=178–179 |isbn=0-19-928075-4 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> Another theory suggests that it is based on a ] word such as the ] ''erebu'' meaning "to go down, set" (cf. ]),<ref name="Etymonline: European">{{cite web| url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=European| title=Etymonline: European| accessdate=10 September 2006}}</ref> ] to Phoenician '' 'ereb'' "evening; west" and Arabic ], Hebrew ''ma'ariv'' (see also '']'', ] ''*h<sub>1</sub>regʷos'', "darkness"). However, M. L. West states that "phonologically, the match between Europa's name and any form of the Semitic word is very poor".<ref>{{Cite book|author=M. L. West |title=The east face of Helicon: west Asiatic elements in Greek poetry and myth |publisher=Clarendon Press |location=Oxford |year=1997 |page=451 |isbn=0-19-815221-3 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> | |||

| The term "continent" usually implies the ] of a large land mass completely or almost completely surrounded by water at its borders. Prior to the adoption of the current convention that includes mountain divides, the border between Europe and Asia had been redefined several times since its first conception in ], but always as a series of rivers, seas and straits that were believed to extend an unknown distance east and north from the Mediterranean Sea without the inclusion of any mountain ranges. Cartographer ] suggested in 1715 Europe was bounded by a series of partly-joined waterways directed towards the Turkish straits, and the ] draining into the upper part of the ] and the ]. In contrast, the present eastern boundary of Europe partially adheres to the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, which is somewhat arbitrary and inconsistent compared to any clear-cut definition of the term "continent". | |||

| Most major world languages use words derived from "Europa" to refer to the "continent" (peninsula). Chinese, for example, uses the word ''{{Unicode|Ōuzhōu}}'' (歐洲); this term is also used by the European Union in ]-language diplomatic relations, despite the ] ''{{nihongo||ヨーロッパ|Yōroppa}}'' being more commonly used. However, in some Turkic languages the originally Persian name '']'' (land of the ]) is used casually in referring to much of Europe, besides official names such as ''Avrupa'' or ''Evropa''.<ref name="davison">{{Cite journal|author=Davidson, Roderic H. |title=Where is the Middle East?|jstor=20029452 |journal=Foreign Affairs |volume=38|issue=4 |pages=665–675 |year=1960|doi=10.2307/20029452 |ref=harv}}</ref> | |||

| The current division of Eurasia into two continents now reflects ] cultural, linguistic and ethnic differences which vary on a spectrum rather than with a sharp dividing line. The geographic border between Europe and Asia does not follow any state boundaries and now only follows a few bodies of water. Turkey is generally considered a ] divided entirely by water, while ] and ] are only partly divided by waterways. France, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain<!--but not the United Kingdom: British Overseas Territories are not part of the UK--> are also transcontinental (or more properly, intercontinental, when oceans or large seas are involved) in that their main land areas are in Europe while pockets of their territories are located on other ] separated from Europe by large bodies of water. Spain, for example, has territories south of the ]—namely, ] and ]—which are parts of ] and share a border with Morocco. According to the current convention, Georgia and Azerbaijan are transcontinental countries where waterways have been completely replaced by mountains as the divide between continents. | |||

| ===History of the concept=== | |||

| {{see also|Boundary between Europe and Asia}} | |||

| ====Early history==== | |||

| ]'' ('Queen Europe') in 1582|alt=|270x270px]] | |||

| The first recorded usage of ''Eurṓpē'' as a geographic term is in the ] to ], in reference to the western shore of the ]. As a name for a part of the known world, it is first used in the 6th century BCE by ] and ]. Anaximander placed the boundary between Asia and Europe along the Phasis River (the modern ] on the territory of ]) in the Caucasus, a convention still followed by ] in the 5th century BCE.<ref>'']'' 4.38. C.f. James Rennell, ''The geographical system of Herodotus examined and explained'', Volume 1, Rivington 1830, </ref> Herodotus mentioned that the world had been divided by unknown persons into three parts—Europe, Asia, and Libya (Africa)—with the ] and the Phasis forming their boundaries—though he also states that some considered the ], rather than the Phasis, as the boundary between Europe and Asia.<ref>Herodotus, 4:45</ref> Europe's eastern frontier was defined in the 1st century by geographer ] at the River Don.<ref>Strabo ''Geography 11.1''</ref> The '']'' described the continents as the lands given by ] to his three sons; Europe was defined as stretching from the ] at the ], separating it from ], to the Don, separating it from Asia.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Genesis and the Jewish antiquities of Flavius Josephus|first= Thomas W.|last= Franxman|publisher=Pontificium Institutum Biblicum|year= 1979|isbn=978-88-7653-335-8|pages=101–102}}</ref> | |||

| The convention received by the ] and surviving into modern usage is that of the ] used by Roman-era authors such as ],<ref>W. Theiler, ''Posidonios. Die Fragmente'', vol. 1. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1982, fragm. 47a.</ref> ],<ref>I. G. Kidd (ed.), ''Posidonius: The commentary'', Cambridge University Press, 2004, {{ISBN|978-0-521-60443-7}}, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801115807/https://books.google.com/books?id=_iXs1aCr1ckC&pg=PA738 |date=1 August 2020 }}.</ref> and ],<ref>'']'' 7.5.6 (ed. Nobbe 1845, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200524011208/https://books.google.com/books?id=vHMCAAAAQAAJ |date=24 May 2020 }}, p. 178) {{lang|grc|Καὶ τῇ Εὐρώπῃ δὲ συνάπτει διὰ τοῦ μεταξὺ αὐχένος τῆς τε Μαιώτιδος λίμνης καὶ τοῦ Σαρματικοῦ Ὠκεανοῦ ἐπὶ τῆς διαβάσεως τοῦ Τανάϊδος ποταμοῦ. }} "And is connected to Europe by the land-strait between Lake Maiotis and the Sarmatian Ocean where the river Tanais crosses through."</ref> who took the Tanais (the modern Don River) as the boundary. | |||

| The Roman Empire did not attach a strong identity to the concept of continental divisions. However, following the fall of the ], the ], linked to Latin and the Catholic church, began to associate itself with the concept of "Europe".<ref name="Pocock2002">{{cite book |author1=J. G. A. Pocock |author1-link=J. G. A. Pocock |editor1-last=Pagden |editor1-first=Anthony |title=The Idea of Europe From Antiquity to the European Union |date=2002 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0511496813 |chapter=Some Europes in Their History |chapter-url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/idea-of-europe/some-europes-in-their-history/261CF37C1E49E93280878F816D4483F1 |doi=10.1017/CBO9780511496813.003 |pages=57–61 |access-date=30 July 2022 |archive-date=23 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220323132907/https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/idea-of-europe/some-europes-in-their-history/261CF37C1E49E93280878F816D4483F1 |url-status=live }}</ref> The term "Europe" is first used for a cultural sphere in the ] of the 9th century. From that time, the term designated the sphere of influence of the ], as opposed to both the ] churches and to the ]. | |||

| A cultural definition of Europe as the lands of ] coalesced in the 8th century, signifying the new cultural condominium created through the confluence of Germanic traditions and Christian-Latin culture, defined partly in contrast with ] and ], and limited to northern ], the British Isles, France, Christianised western Germany, the Alpine regions and northern and central Italy.<ref>], ''The Civilization of the Middle Ages'', 1993, ""Culture and Society in the First Europe", pp185ff.</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Dawson|first1=Christopher|title=Crisis in Western Education|year=1961|isbn=978-0-8132-1683-6|edition=reprint|first2=Glenn|last2=Olsen|page=108|publisher=CUA Press }}</ref> The concept is one of the lasting legacies of the ]: ''Europa'' often{{dubious|date=October 2016}}<!--inflated from "once or twice"--> figures in the letters of Charlemagne's court scholar, ].<ref>Noted by Cantor, 1993:181.</ref> The transition of Europe to being a cultural term as well as a geographic one led to the borders of Europe being affected by cultural considerations in the East, especially relating to areas under Byzantine, Ottoman, and Russian influence. Such questions were affected by the positive connotations associated with the term Europe by its users. Such cultural considerations were not applied to the Americas, despite their conquest and settlement by European states. Instead, the concept of "Western civilisation" emerged as a way of grouping together Europe and these colonies.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.unaoc.org/repository/9334Western%20Historiography%20and%20Problem%20of%20Western%20History%20-%20JGA%20Pocock.doc.pdf |title=Western historiography and the problem of "Western" history |author=J. G. A. Pocock |author-link=J. G. A. Pocock |publisher=United Nations |pages=5–6 |access-date=30 July 2022 |archive-date=13 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220613222622/https://www.unaoc.org/repository/9334Western%20Historiography%20and%20Problem%20of%20Western%20History%20-%20JGA%20Pocock.doc.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ====Modern definitions==== | |||

| {{further|Regions of Europe|Continental Europe}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The question of defining a precise eastern boundary of Europe arises in the Early Modern period, as the eastern extension of ] began to include ]. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the 18th century, the traditional division of the landmass of ] into two continents, Europe and Asia, followed Ptolemy, with the boundary following the ], the ], the ], the ] and the ] (ancient ]). But maps produced during the 16th to 18th centuries tended to differ in how to continue the boundary beyond the Don bend at ] (where it is closest to the Volga, now joined with it by the ]), into territory not described in any detail by the ancient geographers. | |||

| Around 1715, ] produced a map showing the northern part of the ] and the ], a major tributary of the Ob, as components of a series of partly-joined waterways taking the boundary between Europe and Asia from the Turkish Straits, and the Don River all the way to the Arctic Ocean. In 1721, he produced a more up to date map that was easier to read. However, his proposal to adhere to major rivers as the line of demarcation was never taken up by other geographers who were beginning to move away from the idea of water boundaries as the only legitimate divides between Europe and Asia. | |||

| Four years later, in 1725, ] was the first to depart from the classical Don boundary. He drew a new line along the ], following the Volga north until the ], along ] (the ] between the Volga and ]s), then north and east along the latter waterway to its source in the ]. At this point he proposed that mountain ranges could be included as boundaries between continents as alternatives to nearby waterways. Accordingly, he drew the new boundary north along ] rather than the nearby and parallel running Ob and Irtysh rivers.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Das Nord-und Ostliche Theil von Europa und Asia|author=Philipp Johann von Strahlenberg|year=1730|language=de|page=106}}</ref> This was endorsed by the Russian Empire and introduced the convention that would eventually become commonly accepted. However, this did not come without criticism. ], writing in 1760 about ]'s efforts to make Russia more European, ignored the whole boundary question with his claim that neither Russia, Scandinavia, northern Germany, nor Poland were fully part of Europe.<ref name="Pocock2002"/> Since then, many modern analytical geographers like ] have declared that they see little validity in the Ural Mountains as a boundary between continents.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jrVW9W9eiYMC&pg=PA8|title=Europe: A History|page=8|access-date=23 August 2010|isbn=978-0-19-820171-7|date=1996|last1=Davies|first1=Norman|publisher=Oxford University Press |archive-date=1 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801123242/https://books.google.com/books?id=jrVW9W9eiYMC&pg=PA8|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The mapmakers continued to differ on the boundary between the lower Don and Samara well into the 19th century. The ] published by the ] has the boundary follow the Don beyond Kalach as far as ] before cutting north towards ], while other 18th- to 19th-century mapmakers such as ] followed Strahlenberg's prescription. To the south, the ] was identified {{Circa|1773}} by a German naturalist, ], as a valley that once connected the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea,<ref name="oren-icn.ru">{{cite web|url=http://oren-icn.ru/index.php/discussmenu/retrospectiva/685-eagraniza |title=Boundary of Europe and Asia along Urals |language=ru |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120108153922/http://oren-icn.ru/index.php/discussmenu/retrospectiva/685-eagraniza |archive-date=8 January 2012 }}</ref><ref>Peter Simon Pallas, ''Journey through various provinces of the Russian Empire'', vol. 3 (1773)</ref> and subsequently was proposed as a natural boundary between continents. | |||

| By the mid-19th century, there were three main conventions, one following the Don, the ] and the Volga, the other following the Kuma–Manych Depression to the Caspian and then the Ural River, and the third abandoning the Don altogether, following the ] to the Caspian. The question was still treated as a "controversy" in geographical literature of the 1860s, with ] advocating the Caucasus crest boundary as the "best possible", citing support from various "modern geographers".<ref>Douglas W. Freshfield, " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801113249/https://books.google.com/books?id=ips8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA71 |date=2020-08-01 }}", ''Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society'', Volumes 13–14, 1869. | |||

| Cited as de facto convention by Baron von Haxthausen, ''Transcaucasia'' (1854); review </ref> | |||

| In ] and the ], the boundary along the Kuma–Manych Depression was the most commonly used as early as 1906.<ref>{{dead link|date=August 2016}}, '']'', 1906</ref> In 1958, the Soviet Geographical Society formally recommended that the boundary between the Europe and Asia be drawn in textbooks from ], on the ], along the eastern foot of Ural Mountains, then following the ] until the ], and then the ]; and Kuma–Manych Depression,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://velikijporog.narod.ru/st_evraz_gran.htm|title=Do we live in Europe or in Asia?|language=ru|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=18 February 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180218073322/http://velikijporog.narod.ru/st_evraz_gran.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> thus placing the Caucasus entirely in Asia and the Urals entirely in Europe.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.i-u.ru/biblio/archive/orlenok_fisicheskaja/06.aspx |title=Physical Geography |year=1998 |author=Orlenok V. |language=ru |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111016212930/http://www.i-u.ru/biblio/archive/orlenok_fisicheskaja/06.aspx |archive-date=16 October 2011 }}</ref> The '']'' adopted a boundary along the ] and ] rivers, so southwards from the Kuma and the Manych, but still with the Caucasus entirely in Asia.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Tutin |first1=T.G. |title=Flora Europaea, Volume 1: Lycopodiaceae to Platanaceae |last2=Heywood |first2=V.H. |last3=Burges |first3=N.A. |last4=Valentine |first4=D.H. |last5=Walters |first5=S.M. |last6=Webb |first6=D.A. |date=1964 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-06661-7 |location=Cambridge}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Tutin |first=Thomas Gaskell |title=Flora Europaea, Volume 1: Psilotaceae to Platanaceae |date=1993 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-41007-6 |edition=2nd |location=Cambridge New York Melbourne }}</ref> However, most geographers in the Soviet Union favoured the boundary along the Caucasus crest,<ref>E.M. Moores, R.W. Fairbridge, ''Encyclopedia of European and Asian regional geology'', Springer, 1997, {{ISBN|978-0-412-74040-4}}, p. 34: "most Soviet geographers took the watershed of the Main Range of the Greater Caucasus as the boundary between Europe and Asia."</ref> and this became the common convention in the later 20th century, although the Kuma–Manych boundary remained in use in some 20th-century maps. | |||

| Some view the separation of ] into Asia and Europe as a residue of ]: "In physical, cultural and historical diversity, ] and ] are comparable to the entire European landmass, not to a single European country. ."{{sfnp|Lewis|Wigen|1997|p=?}} | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 62: | Line 149: | ||

| ===Prehistory=== | ===Prehistory=== | ||

| {{Main|Prehistoric Europe}} | {{Main|Prehistoric Europe}} | ||

| ], c. 20,000 years ago<br /> | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| {{legend|#c54b00|] culture}} | |||

| ]'', neolithic pottery from ]]] | |||

| {{legend|#ca00b0|] culture<ref name="Nature-2023"/>}} | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| ]] | |||

| ] from ] ]]] | |||

| ] in ] ({{c.}} 15,000 BCE)]] | |||

| '']'', which lived roughly 1.8 million years ago in ], is the earliest ] to have been discovered in Europe.<ref>{{Cite journal| author = A. Vekua, D. Lordkipanidze, G. P. Rightmire, J. Agusti, R. Ferring, G. Maisuradze, et al. | year = 2002 | title = A new skull of early ''Homo'' from Dmanisi, Georgia | journal = Science | volume = 297 | pages = 85–9 | doi = 10.1126/science.1072953 | pmid = 12098694 | issue = 5578 | ref = harv}}</ref> Other hominid remains, dating back roughly 1 million years, have been discovered in ], ].<ref>], ], found in June 2007]</ref> ] (named for the ] valley in ]) appeared in Europe 150,000 years ago and disappeared from the fossil record about 28,000 BC, with this extinction probably ], and their final refuge being present-day ]. The Neanderthals were supplanted by modern humans (]), who appeared in Europe around 43 to 40 thousand years ago.<ref name="natgeo 21">National Geographic, 21.</ref> | |||

| ] in the ] (Late Neolithic from 3000 to 2000 BCE)]] | |||

| During the 2.5 million years of the ], numerous cold phases called ] (]), or significant advances of continental ice sheets, in Europe and North America, occurred at intervals of approximately 40,000 to 100,000 years. The long glacial periods were separated by more temperate and shorter ]s which lasted about 10,000–15,000 years. The last cold episode of the ] ended about 10,000 years ago.<ref>{{cite magazine|url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/prehistoric-world/quaternary|title=Quaternary Period|magazine=National Geographic|date=6 January 2017|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=29 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201129042714/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/prehistoric-world/quaternary/|url-status=dead}}</ref> Earth is currently in an interglacial period of the Quaternary, called the ].<ref>{{cite news |title=How long can we expect the present Interglacial period to last? |url=https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/how-long-can-we-expect-present-interglacial-period-last |work=U.S. Department of the Interior |access-date=30 July 2022 |archive-date=26 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220726044340/http://www.usgs.gov/faqs/how-long-can-we-expect-present-interglacial-period-last |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| '']'', which lived roughly 1.8 million years ago in ], is the earliest ] to have been discovered in Europe.<ref>{{Cite journal|author1=A. Vekua |author2=D. Lordkipanidze |author3=G.P. Rightmire |author4=J. Agusti |author5=R. Ferring |author6=G. Maisuradze |s2cid=32726786 | year = 2002 | title = A new skull of early ''Homo'' from Dmanisi, Georgia | journal = Science | volume = 297 | pages = 85–89 | doi = 10.1126/science.1072953 | pmid = 12098694 | issue = 5578 |display-authors=etal|bibcode=2002Sci...297...85V }}</ref> ] hominin remains, dating back roughly 1 million years, have been discovered in ], ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210922200046/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/6256356.stm |date=22 September 2021 }} ], ], found in June 2007</ref> ] (named after the ] in ]) appeared in Europe 150,000 years ago (115,000 years ago it is found already in the territory of present-day ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cnn.com/2018/10/10/health/neanderthal-child-eaten-by-giant-bird/index.html|title=Bones reveal Neanderthal child was eaten by a giant bird|first=Ashley|last=Strickland|website=CNN|date=10 October 2018|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=7 July 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220707235740/https://www.cnn.com/2018/10/10/health/neanderthal-child-eaten-by-giant-bird/index.html|url-status=live}}</ref>) and disappeared from the fossil record about 40,000 years ago,<ref>{{cite news |title=Neanderthals Died Out 10,000 Years Earlier Than Thought, With Help From Modern Humans |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/140820-neanderthal-dating-bones-archaeology-science |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210218071546/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/140820-neanderthal-dating-bones-archaeology-science |url-status=dead |archive-date=18 February 2021 |work=National Geographic |date=21 August 2014}}</ref> with their final refuge being the Iberian Peninsula. The Neanderthals were supplanted by modern humans (]), who seem to have appeared in Europe around 43,000 to 40,000 years ago.<ref name="natgeo 21">National Geographic, 21.</ref> However, there is also evidence that Homo sapiens arrived in Europe around 54,000 years ago, some 10,000 years earlier than previously thought.<ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.1038/d41586-022-01593-3 | title=My work digging up the shelters of our ancestors | year=2022 | last1=Fleming | first1=Nic | journal=Nature | volume=606 | issue=7916 | page=1035 | pmid=35676354 | bibcode=2022Natur.606.1035F | s2cid=249520231 | doi-access=free }}</ref> The earliest sites in Europe dated 48,000 years ago are ] (Italy), ] (Germany) and ] (France).<ref name=range>{{cite journal |last1=Fu |first1=Qiaomei |display-authors=etal|title=The genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia |journal=Nature |volume=514 |issue=7523 |pages=445–449 |date=23 October 2014 |doi=10.1038/nature13810|pmid=25341783 |pmc=4753769 |bibcode=2014Natur.514..445F |hdl=10550/42071 }}</ref><ref>42.7–41.5 ka (]). | |||

| The ] period—marked by the cultivation of crops and the raising of livestock, increased numbers of settlements and the widespread use of pottery—began around 7000 BC in ] and the ], probably influenced by earlier farming practices in ] and the ]. It spread from South Eastern Europe along the valleys of the ] and the ] (]) and along the ] (]). Between 4500 and 3000 BC, these central European neolithic cultures developed further to the west and the north, transmitting newly acquired skills in producing copper artefacts. In Western Europe the Neolithic period was characterized not by large agricultural settlements but by field monuments, such as ]s, ]s and ]s.<ref>{{Cite document|first=Chris|last=Scarre|authorlink=Chris Scarre|title=The Oxford Companion to Archaeology|first-editor=Brian M.|last-editor= Fagan|publisher= ]|year=1996|pages=215–216|ref=harv|postscript=<!--None-->|isbn=0-19-507618-4|unused_data=DUPLICATE DATA: authorlink=Brian Fagan}}</ref> The ] cultural horizon flourished at the transition from the Neolithic to the ]. During this period giant ] monuments, such as the ] and ], were constructed throughout Western and Southern Europe.<ref>], R J C, ''Stonehenge'' (], 1956)</ref><ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Prehistory|title=European Megalithic|volume=4 : Europe|editor1-first=Peter Neal|editor1-last=Peregrine|editor1-link=Peter N. Peregrine|editor2-first=Melvin|editor2-last=Ember|editor2-link=Melvin Ember|publisher=Springer|year= 2001 | |||

| {{cite journal | last1 = Douka | first1 = Katerina | display-authors = etal | year = 2012| title = A new chronostratigraphic framework for the Upper Palaeolithic of Riparo Mochi (Italy) | journal = Journal of Human Evolution | volume = 62 | issue = 2| pages = 286–299 | doi = 10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.009 | pmid = 22189428 | bibcode = 2012JHumE..62..286D }}</ref> | |||

| |isbn=0-306-46258-3|pages=157–184}}</ref> The ] began in the late 3rd millennium BC with the ]. | |||

| The ] period—marked by the cultivation of crops and the raising of livestock, increased numbers of settlements and the widespread use of pottery—began around 7000 BCE in ] and the ], probably influenced by earlier farming practices in ] and the ].<ref name="Borza">{{Citation | last = Borza | first = E.N. | title = In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence of Macedon | page = 58 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=614pd07OtfQC&pg=PA58 | publisher = Princeton University Press | year = 1992 | isbn = 978-0-691-00880-6 | access-date = 30 July 2022 | archive-date = 1 August 2020 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200801114047/https://books.google.com/books?id=614pd07OtfQC&pg=PA58 | url-status = live }}</ref> It spread from the Balkans along the valleys of the ] and the ] (]), and along the ] (]). Between 4500 and 3000 BCE, these central European neolithic cultures developed further to the west and the north, transmitting newly acquired skills in producing copper artifacts. In Western Europe the Neolithic period was characterised not by large agricultural settlements but by field monuments, such as ]s, ]s and ]s.<ref>{{Cite book|first=Chris|last=Scarre|author-link=Chris Scarre|title=The Oxford Companion to Archaeology|editor-first=Brian M.|editor-last= Fagan|publisher= ]|year=1996|pages=215–216|isbn=978-0-19-507618-9|editor-link=Brian M. Fagan}}</ref> The ] cultural horizon flourished at the transition from the Neolithic to the ]. During this period giant ] monuments, such as the ] and ], were constructed throughout Western and Southern Europe.<ref>], ''Stonehenge'' (], 1956)</ref><ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Prehistory|title=European Megalithic|volume=4 |editor1-first=Peter Neal|editor1-last=Peregrine|editor1-link=Peter N. Peregrine|editor2-first=Melvin|editor2-last=Ember|editor2-link=Melvin Ember|publisher=Springer|year= 2001 | |||

| The ] began around 800 BC, with the ]. Iron Age colonisation by the ] gave rise to early ] cities. Early ] and ] from around the 8th century BC gradually gave rise to historical Classical antiquity. | |||

| |isbn=978-0-306-46258-0|pages=157–184}}</ref> | |||

| The modern native populations of Europe largely descend from three distinct lineages:<ref name="Indo-European"/> Mesolithic ]s, descended from populations associated with the Paleolithic ] culture;<ref name="Nature-2023">{{cite journal |last1=Posth|last2= Yu|last3=Ghalichi|title=Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European hunter-gatherers |journal=] |date=2023 |volume=615 |issue=2 March 2023 |pages=117–126 |doi=10.1038/s41586-023-05726-0 |pmid=36859578 |pmc=9977688 |bibcode=2023Natur.615..117P }}</ref> Neolithic ] who migrated from Anatolia during the ] 9,000 years ago;<ref>{{cite news |title=When the First Farmers Arrived in Europe, Inequality Evolved |url=https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/when-the-first-farmers-arrived-in-europe-inequality-evolved/ |work=Scientific American |date=1 July 2020}}</ref> and ] ] who expanded into Europe from the ] of Ukraine and southern Russia in the context of ] 5,000 years ago.<ref name="Indo-European">{{Cite journal|last1=Haak |first1=Wolfgang |last2=Lazaridis |first2=Iosif |last3=Patterson |first3=Nick |last4=Rohland |first4=Nadin |last5=Mallick |first5=Swapan |last6=Llamas |first6=Bastien |last7=Brandt |first7=Guido |last8=Nordenfelt |first8=Susanne |last9=Harney |first9=Eadaoin |last10=Stewardson |first10=Kristin |last11=Fu |first11=Qiaomei |date=11 June 2015 |title=Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe |journal=] |volume=522 |issue=7555 |pages=207–211 |doi=10.1038/nature14317 |issn=0028-0836 |pmc=5048219 |pmid=25731166 |bibcode=2015Natur.522..207H |arxiv=1502.02783}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gibbons |first1=Ann |title=Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population |journal=Science |date=21 February 2017 |url=https://www.science.org/content/article/thousands-horsemen-may-have-swept-bronze-age-europe-transforming-local-population}}</ref> The ] began c. 3200 BCE in Greece with the ] on ], the first advanced civilisation in Europe.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/cultures/europe/ancient_greece.aspx |publisher=British Museum |title=Ancient Greece |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120615141437/http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/cultures/europe/ancient_greece.aspx |archive-date=15 June 2012 }}</ref> The Minoans were followed by the ], who collapsed suddenly around 1200 BCE, ushering the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.arch.ox.ac.uk/classical-archaeology-periods.html|title=Periods – School of Archaeology|publisher=University of Oxford|access-date=25 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181119063421/http://www.arch.ox.ac.uk/classical-archaeology-periods.html|archive-date=19 November 2018|url-status=dead}}</ref> Iron Age colonisation by the ] and ] gave rise to early ] cities. Early ] and ] from around the 8th century BCE gradually gave rise to historical Classical antiquity, whose beginning is sometimes dated to 776 BCE, the year of the first ].<ref>{{Citation | first = John R. | last = Short | title = An Introduction to Urban Geography | page = 10 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=uGE9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA10 | publisher = Routledge | year = 1987 | isbn = 978-0-7102-0372-4 | access-date = 30 July 2022 | archive-date = 20 March 2022 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220320034104/https://books.google.com/books?id=uGE9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA10 | url-status = live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Classical antiquity=== | ===Classical antiquity=== | ||

| {{Main|Classical antiquity}} | {{Main|Classical antiquity}} | ||

| {{See also|Ancient Greece|Ancient Rome}} | {{See also|Ancient Greece|Ancient Rome}} | ||

| ] |

] in ] (432 BCE)]] | ||

| ] had a profound impact on Western civilisation. Western ] and ] are often attributed to Ancient Greece.<ref name="natgeo 76">National Geographic, 76.</ref> The Greeks invented the ], or city-state, which played a fundamental role in their concept of identity.<ref name="natgeo 82">National Geographic, 82.</ref> These Greek political ideals were rediscovered in the late 18th century by European philosophers and idealists. Greece also generated many cultural contributions: in ], ] and ] under ], ] and ]; in ] with ] and ]; in dramatic and narrative verse, starting with the epic poems of ];<ref name="natgeo 76"/> and in science with ], ] and ].<ref name=Heath>{{Cite book| first=Thomas Little | last=Heath| authorlink= T. L. Heath| title=A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume I| publisher=]| year=1981| isbn=0-486-24073-8| ref=harv| postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref><ref name=Heath_Vol_2>{{Cite book| first=Thomas Little| last=Heath| authorlink= T. L. Heath| title=A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume II| publisher=Dover publications| year=1981| isbn=0-486-24074-6| ref=harv| postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref><ref>Pedersen, Olaf. ''Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction''. 2nd edition. Cambridge: ], 1993.</ref> | |||

| ] at its greatest extent]] | |||

| Another major influence on Europe came from the ] which left its mark on ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="natgeo 77">National Geographic, 76–77.</ref> During the '']'', the Roman Empire expanded to encompass the entire ] and much of Europe.<ref name = "mieawl">{{Cite book|last=McEvedy|first=Colin|title=The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1961}}</ref> | |||

| Ancient Greece was the founding culture of Western civilisation. Western ] and ] are often attributed to Ancient Greece.<ref name="Daly2013">{{cite book|first=Jonathan|last=Daly|title=The Rise of Western Power: A Comparative History of Western Civilization|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9aZPAQAAQBAJ|year=2013|publisher=A&C Black|isbn=978-1-4411-1851-6|pages=7–9|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=28 April 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220428191428/https://books.google.com/books?id=9aZPAQAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> The Greek city-state, the ], was the fundamental political unit of classical Greece.<ref name="Daly2013"/> In 508 BCE, ] instituted the world's first ] system of government in ].<ref name="BKDunn1992">{{Citation | first = John | last = Dunn | title = Democracy: the unfinished journey 508 BCE – 1993 CE | publisher = Oxford University Press | year = 1994 | isbn = 978-0-19-827934-1}}</ref> The Greek political ideals were rediscovered in the late 18th century by European philosophers and idealists. Greece also generated many cultural contributions: in ], ] and ] under ], ] and ]; in ] with ] and ]; in dramatic and narrative verse, starting with the epic poems of ];<ref name="natgeo 76">National Geographic, 76.</ref> in drama with ] and ]; in medicine with ] and ]; and in science with ], ], and ].<ref name="Heath">{{Cite book| first=Thomas Little | last=Heath| author-link= T. L. Heath| title=A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume I| publisher=]| year=1981| isbn=978-0-486-24073-2}}</ref><ref name="Heath_Vol_2">{{Cite book| first=Thomas Little| last=Heath| author-link= T. L. Heath| title=A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume II| publisher=Dover publications| year=1981| isbn=978-0-486-24074-9}}</ref><ref>Pedersen, Olaf. ''Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction''. 2nd edition. Cambridge: ], 1993.</ref> In the course of the 5th century BCE, several of the Greek ] would ultimately check the ] advance in Europe through the ], considered a pivotal moment in world history,<ref name="Strauss2005">{{cite book|first=Barry|last=Strauss|title=The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece – and Western Civilization|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nQFtMcD5dOsC|year=2005|publisher=Simon and Schuster|isbn=978-0-7432-7453-1|pages=1–11|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=23 June 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220623162126/https://books.google.com/books?id=nQFtMcD5dOsC|url-status=live}}</ref> as the 50 years of peace that followed are known as ], the seminal period of ancient Greece that laid many of the foundations of Western civilisation. | |||

| ] influenced ]s such as ], ], and ], who all spent time on the Empire's northern border fighting ], ] and ] tribes.<ref name="natgeo 123">National Geographic, 123.</ref><ref>Foster, Sally M., ''Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland.'' Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3</ref> ] was eventually ] by ] after three centuries of ]. | |||

| ] (years CE)]] | |||

| Greece was followed by ], which left its mark on ], ], ], ], ], ], and many more key aspects in western civilisation.<ref name="Daly2013"/> By 200 BCE, Rome had conquered ] and over the following two centuries it conquered ], ] (] and ]), the ]n coast, much of the ], ] (] and ]), and ] (] and ]). | |||

| Expanding from their base in central Italy beginning in the third century BCE, the Romans gradually expanded to eventually rule the entire Mediterranean basin and Western Europe by the turn of the millennium. The ] ended in 27 BCE, when ] proclaimed the ]. The two centuries that followed are known as the '']'', a period of unprecedented peace, prosperity and political stability in most of Europe.<ref name="mieawl">{{Cite book|last=McEvedy|first=Colin|title=The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History|publisher=Penguin Books|year=1961}}</ref> The empire continued to expand under emperors such as ] and ], who spent time on the Empire's northern border fighting ], ] and ] tribes.<ref name="natgeo 123">National Geographic, 123.</ref><ref>Foster, Sally M., ''Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland''. Batsford, London, 2004. {{ISBN|0-7134-8874-3}}</ref> ] was ] by ] in 313 CE after three centuries of ]. Constantine also permanently moved the capital of the empire from Rome to the city of ] (modern-day ]) which was renamed ] in his honour in 330 CE. Christianity became the sole official religion of the empire in 380 CE, and in 391–392 CE the emperor ] outlawed pagan religions.<ref name="FriellWilliams2005">{{cite book|first1=Stephen|last1=Williams|first2=Gerard|last2=Friell|title=Theodosius: The Empire at Bay|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=I8KRAgAAQBAJ|year=2005|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-135-78262-7|page=105|access-date=30 July 2022|archive-date=30 May 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220530232720/https://books.google.com/books?id=I8KRAgAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> This is sometimes considered to mark the end of antiquity; alternatively antiquity is considered to end with the ] in 476 CE; the closure of the pagan ] in 529 CE;<ref>{{cite book |title=A History of Greek Literature |last=Hadas |first=Moses |year=1950 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-231-01767-1 |pages=273, 327 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dOht3609JOMC&pg=PA273 |access-date=30 July 2022 |archive-date=21 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220521051042/https://books.google.com/books?id=dOht3609JOMC&pg=PA273 |url-status=live }}</ref> or the rise of Islam in the early 7th century CE. During most of its existence, the ] was one of the most powerful economic, cultural, and military forces in Europe.<ref>{{Harvnb|Laiou|Morisson|2007|pp=130–131}}; {{Harvnb|Pounds|1979|p=124}}.</ref> | |||

| ===Early Middle Ages=== | ===Early Middle Ages=== | ||

| {{Main|Late Antiquity|Early Middle Ages}} | {{Main|Late Antiquity|Early Middle Ages}} | ||

| {{See also|Dark Ages (historiography)|Age of Migrations}} | {{See also|Dark Ages (historiography){{!}}Dark Ages|Age of Migrations}} | ||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| ] pledges ] to ], ].]] | |||

| | align = left | |||

| During the ], Europe entered a long period of change arising from what historians call the "]". There were numerous invasions and migrations amongst the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and, later still, the ] and ].<ref name = "mieawl"/> ] thinkers such as ] would later refer to this as the "]".<ref>, ''Journal of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 4, No. 1. (Jan., 1943), pp. 69–74.</ref> Isolated monastic communities were the only places to safeguard and compile written knowledge accumulated previously; apart from this very few written records survive and much literature, philosophy, mathematics, and other thinking from the classical period disappeared from Europe.<ref>], ''The Medieval World 300 to 1300''.</ref> | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 240 | |||

| | image1 = Europe around 650.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Europe c. 650 | |||

| | image2 = Frankish Empire 481 to 814-en.svg | |||

| | footer = ] in 814: {{Legend0|#3CB371|Francia}}, {{Legend0|#FAEBD7|Tributaries}} | |||

| }} | |||

| During the ], Europe entered a long period of change arising from what historians call the "]". There were numerous invasions and migrations amongst the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="mieawl"/> ] thinkers such as ] would later refer to this as the "Dark Ages".<ref>''Journal of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 4, No. 1. (January 1943), pp. 69–74.</ref> | |||

| During the Dark Ages, the ] fell under the control of various tribes. The Germanic and Slav tribes established their domains over Western and Eastern Europe respectively.<ref name="natgeo 143">National Geographic, 143–145.</ref> Eventually the ] were united under ].<ref name="natgeo 162">National Geographic, 162.</ref> ], a Frankish king of the ] dynasty who had conquered most of Western Europe, was anointed "]" by the Pope in 800. This led to the founding of the ], which eventually became centred in the German principalities of central Europe.<ref name="natgeo 166">National Geographic, 166.</ref> | |||

| Isolated monastic communities were the only places to safeguard and compile written knowledge accumulated previously; apart from this, very few written records survive. Much literature, philosophy, mathematics, and other thinking from the classical period disappeared from Western Europe, though they were preserved in the east, in the Byzantine Empire.<ref>], ''The Medieval World 300 to 1300''.</ref> | |||

| The predominantly ] ] became known in the west as the ]. Its capital was ]. Emperor ] presided over Constantinople's first golden age: he established a ], funded the construction of the ] and brought the Christian church under state control.<ref name="natgeo 135">National Geographic, 135.</ref> Fatally weakened by the sack of Constantinople during the ], the Byzantines fell in 1453 when they were conquered by the ].<ref name="natgeo 211">National Geographic, 211.</ref> | |||

| While the Roman empire in the west continued to decline, Roman traditions and the Roman state remained strong in the predominantly Greek-speaking ], also known as the ]. During most of its existence, the Byzantine Empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in Europe. Emperor ] presided over Constantinople's first golden age: he established a ] that forms the basis of many modern legal systems, funded the construction of the ] and brought the Christian church under state control.<ref name="natgeo 135">National Geographic, 135.</ref> | |||

| ===Middle Ages=== | |||

| From the 7th century onwards, as the Byzantines and neighbouring ] were severely weakened due to the protracted, centuries-lasting and frequent ], the Muslim Arabs began to make inroads into historically Roman territory, taking the Levant and North Africa and making inroads into ]. In the mid-7th century, following the ], Islam penetrated into the ] region.<ref>{{cite book |quote=(..) It is difficult to establish exactly when Islam first appeared in Russia because the lands that Islam penetrated early in its expansion were not part of Russia at the time, but were later incorporated into the expanding Russian Empire. Islam reached the Caucasus region in the middle of the seventh century as part of the Arab ] of the Iranian Sassanian Empire.|title=Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security|first=Shireen |last= Hunter | publisher= M.E. Sharpe | date = 2004 |page=3 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> Over the next centuries Muslim forces took ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>Kennedy, Hugh (1995). "The Muslims in Europe". In McKitterick, Rosamund, ''The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 500 – c. 700'', pp. 249–272. Cambridge University Press. 052136292X.</ref> Between 711 and 720, most of the lands of the ] of ] were brought under ] rule—save for small areas in the northwest (]) and largely ] regions in the ]. This territory, under the Arabic name ], became part of the expanding ]. The unsuccessful ] (717) weakened the ] and reduced their prestige. The Umayyads were then defeated by the ] leader ] at the ] in 732, which ended their northward advance. In the remote regions of north-western Iberia and the middle ] the power of the Muslims in the south was scarcely felt. It was here that the foundations of the Christian kingdoms of ], ], and ] were laid and from where the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula would start. However, no coordinated attempt would be made to drive the ] out. The Christian kingdoms were mainly focused on their own internal power struggles. As a result, the ] took the greater part of eight hundred years, in which period a long list of Alfonsos, Sanchos, Ordoños, Ramiros, Fernandos, and Bermudos would be fighting their Christian rivals as much as the Muslim invaders. | |||

| ] raids and division of the Frankish Empire at the ] in 843]] | |||

| During the Dark Ages, the ] fell under the control of various tribes. The Germanic and Slav tribes established their domains over Western and Eastern Europe, respectively.<ref name="natgeo 143">National Geographic, 143–145.</ref> Eventually the Frankish tribes were united under ].<ref name="natgeo 162">National Geographic, 162.</ref> ], a Frankish king of the ] dynasty who had conquered most of Western Europe, was anointed "]" by the Pope in 800. This led in 962 to the founding of the ], which eventually became centred in the German principalities of central Europe.<ref name="natgeo 166">National Geographic, 166.</ref> | |||

| ] saw the creation of the first Slavic states and the adoption of ] ({{nowrap|{{c.}} 1000 CE)}}. The powerful ] state of ] spread its territory all the way south to the Balkans, reaching its largest territorial extent under ] and causing a series of armed conflicts with ]. Further south, the first ] emerged in the late 7th and 8th century and adopted ]: the ], the ] (later ] and ]), and the ] (later ]). To the east, ] expanded from its capital in ] to become the largest state in Europe by the 10th century. In 988, ] adopted ] as the religion of state.{{sfn|Bulliet|Crossley|Headrick|Hirsch|2011|page=250}}{{sfn|Brown|Anatolios|Palmer|2009|page=66}} Further east, ] became an Islamic state in the 10th century, but was eventually absorbed into Russia several centuries later.<ref>Gerald Mako, "The Islamization of the Volga Bulghars: A Question Reconsidered", Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 18, 2011, 199–223.</ref> | |||

| ===High and Late Middle Ages=== | |||

| {{Main|High Middle Ages|Late Middle Ages|Middle Ages}} | {{Main|High Middle Ages|Late Middle Ages|Middle Ages}} | ||

| {{See also|Medieval demography}} | {{See also|Medieval demography}} | ||

| ] of medieval ] reestablished contacts between Europe, Asia and Africa with extensive trade networks and colonies across the Mediterranean, and had an essential role in the ].<ref>Marc'Antonio Bragadin, ''Storia delle Repubbliche marinare'', Odoya, Bologna 2010, 240 pp., {{ISBN|978-88-6288-082-4}}</ref><ref>G. Benvenuti, ''Le Repubbliche Marinare. Amalfi, Pisa, Genova, Venezia'', Newton & Compton editori, Roma 1989</ref>]] | |||

| The economic growth of Europe around the year 1000, together with the lack of safety on the mainland trading routes, made possible the development of major commercial routes along the coast of the ]. In this context, the growing independence acquired by some coastal cities gave the ] a leading role in the European scene. | |||

| The period between the year 1000 and 1250 is known as the ], followed by the ] until c. 1500. | |||

| During the High Middle Ages the population of Europe experienced significant growth, culminating in the ]. Economic growth, together with the lack of safety on the mainland trading routes, made possible the development of major commercial routes along the coast of the ] and ]s. The growing wealth and independence acquired by some coastal cities gave the ] a leading role in the European scene. | |||

| The Middle Ages on the mainland were dominated by the two upper echelons of the social structure: the nobility and the clergy. ] developed in ] in the Early Middle Ages, and soon spread throughout Europe.<ref name="natgeo 158">National Geographic, 158.</ref> A struggle for influence between the ] and the ] in England led to the writing of ] and the establishment of a ].<ref name="natgeo 186">National Geographic, 186.</ref> The primary source of culture in this period came from the ]. Through monasteries and ]s, the Church was responsible for education in much of Europe.<ref name="natgeo 158"/> | |||

| ] and ], during the ] (1189–1192)]] | |||

| The ] reached the height of its power during the High Middle Ages. An ] in 1054 split the former Roman Empire religiously, with the ] in the ] and the Roman Catholic Church in the former Western Roman Empire. In 1095 ] called for a ] against ] occupying ] and the ].<ref name="natgeo 192">National Geographic, 192.</ref> In Europe itself, the Church organised the ] against heretics. In the ], the ] concluded with the ], ending over seven centuries of Islamic rule in the south-western peninsula.<ref name="natgeo 199">National Geographic, 199.</ref> | |||