| Revision as of 02:31, 16 July 2012 editMedeis (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users49,187 edits restore neutral well-written material← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:32, 12 December 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,459,761 edits Added date. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Roerichism | #UCB_Category 3/9 | ||

| (460 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{expand Russian|topic=bio|date=October 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox Person | |||

| {{refimprove|date=October 2023}} | |||

| {{Short description|Russian painter, writer, archaeologist and philosopher (1874–1947)}} | |||

| {{family name hatnote|Konstantinovich|Roerich|lang=Eastern Slavic}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=April 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| |name = Nicholas Roerich | |name = Nicholas Roerich | ||

| |native_name = {{nobold|Николай Рерих}} | |||

| |image = N_Roerich.jpg | |image = N_Roerich.jpg | ||

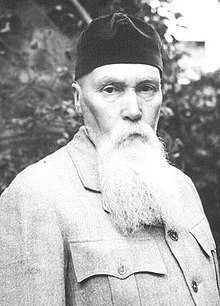

| |caption = Roerich {{circa|1940–1947}} | |||

| |image_size = 144px | |||

| |caption = | |||

| |birth_name = | |birth_name = | ||

| |birth_date = {{birth date|1874|10|9}} | |birth_date = {{birth date|1874|10|9}} | ||

| |birth_place = ], ] | |birth_place = ], ] | ||

| |death_date = {{death date and age|1947|12|13|1874|10|9}} | |death_date = {{death date and age|1947|12|13|1874|10|9}} | ||

| |death_place = ], ] | |death_place = ], ] | ||

| |death_cause = | |death_cause = | ||

| |resting_place = | |resting_place = | ||

| |resting_place_coordinates = | |resting_place_coordinates = | ||

| | |

|nationality = Russian | ||

| |nationality = ] | |||

| |other_names = | |other_names = | ||

| |known_for = | |known_for = | ||

| Line 19: | Line 23: | ||

| |employer = | |employer = | ||

| |occupation = painter, archaeologist, costume and set designer for ballets, operas, and dramas | |occupation = painter, archaeologist, costume and set designer for ballets, operas, and dramas | ||

| |home_town = | |||

| |title = | |||

| |salary = | |||

| |networth = | |||

| |height = | |||

| |weight = | |||

| |term = | |||

| |predecessor = | |||

| |successor = | |||

| |party = | |||

| |boards = | |||

| |religion = | |||

| |spouse = ] | |spouse = ] | ||

| |partner = | |partner = | ||

| Line 36: | Line 28: | ||

| |parents = | |parents = | ||

| |relatives = | |relatives = | ||

| |signature = | |signature = Подпись Николая Рериха-1932 г.jpg | ||

| |website = | |website = | ||

| |footnotes = | |footnotes = | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh'''{{efn|Also spelled as '''Ryorikh''', from {{langx|ru|Рёрих}}}} ({{langx|ru|Николай Константинович Рерих}}), better known as '''Nicholas Roerich''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|r|ɛr|ɪ|k}}; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), was a Russian painter, writer, ], ], ], and ]. In his youth he was influenced by ], a movement in Russian society centered on the spiritual. He was interested in ] and other ]s and his paintings are said to have hypnotic expression.<ref>, стр. 31</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006071558/http://www.watkinsbooks.com/ushahidi/reports/view/266 |date=October 6, 2014 }}</ref> | |||

| '''Nicholas Roerich''', (], ] - ], ]) also known as '''Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh''' (alternative transliteration) ({{lang-ru|Николай Константинович Рерих}}), was a ]n ] and ]<ref> | |||

| // Большая биографическая энциклопедия | |||

| : — // Русская философия: словарь/Под общ. ред. М. А. Маслина / В. В. Сапов. — М.: Республика, 1995 | |||

| : — // Краткий философский словарь / А. П. Алексеев, Г. Г. Васильев и др.; Под ред. А. П. Алексеева — 2-е изд., перераб. и доп. — М.: ТК Велби, Изд-во Проспект, 2004. | |||

| : — // С. Левит. Культурология. XX век. Энциклопедия., 1998 г. | |||

| : — / Новейший философский словарь /Грицанов А. А.. — Научное издание. — Минск: В. М. Скакун, 1999 г. — 896 с. | |||

| : — // Биографический словарь | |||

| : — // Современная энциклопедия | |||

| : — // Большая советская энциклопедия | |||

| : — // Энциклопедический словарь Ф. А. Брокгауза и И. А. Ефрона | |||

| : — // Энциклопедия «Кругосвет» | |||

| : — Рерих Николай Константинович // Современный Энциклопедический словарь. Изд. «Большая Российская Энциклопедия», 1997 г. | |||

| : — // Gallery of Russian Thinkers | |||

| : — / Meyers Konversations Lexikon. Online-version | |||

| </ref>. | |||

| Born in ], ] to the |

Born in ], to a well-to-do ] father and to a Russian mother,<ref>Andrei Znamenski, ''Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia'', Quest Books (2011), p. 157</ref> Roerich lived in various places in the world until his death in ], India.<ref>{{cite web |title=Nicholas Roerich - Russian set designer |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/506736/Nicholas-Roerich |access-date=June 14, 2016}}</ref> Trained as an artist and a lawyer, his main interests were literature, philosophy, ], and especially art. Roerich was a dedicated activist for the cause of preserving art and architecture during times of war. He was nominated several times to the longlist for the ].<ref> Nomination Database</ref> The so-called ] (for the protection of ]) was signed into law by the United States and most other nations of the ] in April 1935. | ||

| == Biography == | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| ===Early life=== | ===Early life=== | ||

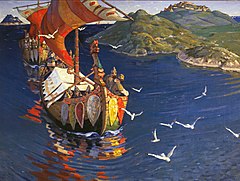

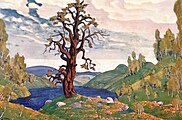

| ]s in |

]s in Rus')]] | ||

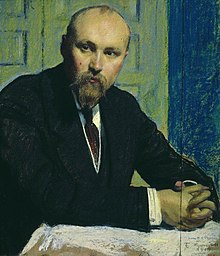

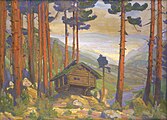

| ]'']] | |||

| Raised in turn-of-the-century St. Petersburg, Roerich matriculated simultaneously at ] and the ] in 1893. He received the title of "artist" in 1897 and a degree in law the following year. He found early employment with the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, whose school he directed from 1906 to 1917. Despite early tensions with the group, he became a member of ]'s "]" society; he chaired the society from 1910 to 1916. | |||

| Raised in late-19th-century St. Petersburg, Roerich enrolled simultaneously at ] and the ] in 1893. He received the title of "artist" in 1897 and a degree in law the next year. He found early employment with the ], whose school he directed from 1906 to 1917. Despite early tensions with the group, he became a member of ]'s "]" society and was its president from 1910 to 1916. | |||

| Artistically, he made a mark as his generation's most talented painter of Russia's ancient past, a subject that meshed well with his lifelong interest in archaeology. He also succeeded in the field of stage design, achieving his greatest fame as one of the designers for Diaghilev's ]. His best-known designs were for Borodin's '']'' (1909 and later productions), and costumes and set for '']'' (1913), composed by ]. | |||

| Artistically, Roerich became known as his generation's most talented painter of Russia's ancient past, a topic that was compatible with his lifelong interest in archeology. He also succeeded as a stage designer by achieving his greatest fame as one of the designers for Diaghilev's ]. His best-known designs were for ]'s '']'' (1909 and later productions),<ref>{{cite book |last=McCannon |first=John |date=2022 |title=Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eASZEAAAQBAJ |publisher=University of Pittsburgh Press |page=107-12 |isbn=978-0822947417 }}</ref> and costumes and set for '']'' (1913),<ref name="NYT">Julie Besonen, , '']'', April 6, 2014.</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=McCannon |first=John |date=2022 |title=Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eASZEAAAQBAJ |publisher=University of Pittsburgh Press |page=121-64 |isbn=978-0822947417 }}</ref> composed by ]. | |||

| Another of Roerich's passions was architecture. His acclaimed "Architectural Studies" (1904-1905) -- the dozens of paintings he completed of fortresses, monasteries, churches, and other monuments during two long trips through Russia -- inspired his decades-long career as an activist on behalf of artistic and architectural preservation. He also designed religious art for places of worship throughout Russia and ], most notably the ''Queen of Heaven'' fresco for the Church of the Holy Spirit which the patroness ] built near her ] estate. | |||

| Along with ] and ], Roerich is considered a major representative of ] in art.<ref name="symbolism">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k44-DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT22|title=Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives|isbn=9781783743414|last1=Hardiman|first1=Louise|last2=Kozicharow|first2=Nicola|date=November 13, 2017|publisher=Open Book Publishers }}</ref> From an early period of his life, he was influenced by apocrypha and medieval sectarian writings such as the mysterious ].<ref>Н. В. Сергеева. Древнерусская традиция в символизме Н.К. Рериха. М.: Международный Центр Рерихов, 2003. {{ISBN|5-86988-080-7}}. Page 87.</ref> | |||

| During the 1900s and early 1910s, Roerich, largely due to the influence of his wife Helena, developed an interest in eastern religions, as well as alternative belief systems such as ]. Both Roerichs became avid readers of the Vedantist essays of ] and ], the poetry of ], and the '']''. The Roerichs' commitment to occult mysticism steadily increased. It was brought to a new pitch during World War I and the Russian revolutions of 1917, to which the couple, like many Russian intellectuals, attached apocalyptic significance. The influence of Theosophy, Vedanta, Buddhism, and other mystical strains of thought can be seen not only in many of his paintings, but in the many short stories and poems Roerich wrote before and after the 1917 revolutions, including the ''Flowers of Morya'' cycle, begun in 1907 and completed in 1921. | |||

| Another of Roerich's artistic subjects was architecture. His acclaimed publication "Architectural Studies" (1904–1905), consisting of dozens of paintings he made of fortresses, monasteries, churches, and other monuments during two long trips through Russia, inspired his decades-long career as an activist on behalf of artistic and architectural preservation. He also designed religious art for places of worship throughout Russia and ], most notably the ''Queen of Heaven'' fresco for the Church of the Holy Spirit, which the patroness ] built near her ] estate, and the stained glass windows for the ] in 1913–1915. His designs for the ] church were so radical that the Orthodox church refused to consecrate the building.<ref name="symbolism" /> | |||

| ===Revolution, emigration, and the United States=== | |||

| ] the Healer, 1916.]] | |||

| After the February Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of the tsarist regime, Roerich, a political moderate who placed spiritual values and Russia's cultural heritage above ideology and party politics, played an active part in artistic politics. With ] and ], he participated in the so-called "Gorky Commission" and its successor organization, the Arts Union (SDI). Both attempted to focus the ]'s and ]'s attention on the need to form a coherent cultural policy and, most urgently, protect art and architecture from destruction and vandalism. At the same time, however, illness forced Roerich to leave the capital and reside in Karelia, the district bordering Finland. He had already resigned the chair of the World of Art society, and he now gave up the directorship of the School of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. After the October Revolution and the rise to power of Lenin's Bolshevik Party, Roerich grew increasingly discouraged about Russia's political future. In early 1918, he, Helena, and their two sons George and Sviatoslav emigrated to Finland. | |||

| During the first decade of the 1900s and in the early 1910s, Roerich, largely by the influence of his wife, Helena, developed an interest in eastern religions, as well as alternative belief systems such as ]. Both Roerichs became avid readers of the Vedantist essays of ] and ], the poetry of ], and the '']''. | |||

| Two unresolved historical debates are associated with Roerich's departure. First, it is often claimed that Roerich was a leading candidate to head a people's commissariat of culture (the Soviet equivalent of a ministry of culture) which the Bolsheviks considered establishing in 1917-1918, but that he refused to take up the post. In fact, Benois was the most likely pick to lead any such commissariat. It appears that Roerich was a preferred choice to run its department of artistic education; the point is rendered moot by the fact that the Soviets elected not to establish such a commissariat. Second, when he wished to reconcile with the USSR, Roerich later maintained that he had not left Soviet Russia deliberately, but that he and his family, living in Karelia, had been cut off from their homeland when civil war broke out in Finland. However, Roerich's extreme hostility to the Bolshevik regime - prompted not so much by a dislike of communism as by his revulsion at Lenin's ruthlessness and his fear that Bolshevik rule would lead to the destruction of Russia's artistic and architectural heritage - was amply documented. He illustrated ]'s anti-communist polemic "S.O.S." and had a widely published pamphlet, "Violators of Art" (1918-1919). Roerich believed that "the triumph of Russian culture would come about through a new appreciation of ancient myth and legend".<ref>{{cite book | last = Bowlt | first = John E. | title = Moscow and St. Petersburg 1900-1920: Art, Life and Culture | publisher = The Vendome Press | date = 2008 | location = New York | pages = 69 | isbn =978-0-86565-191-3}}</ref> | |||

| The Roerichs' commitment to occult mysticism increased steadily. It was especially intense during ] and the 1917 ] to which the couple, like other many Russian intellectuals, accorded apocalyptic significance.<ref>John McCannon, "Apocalypse and Tranquility: The World War I Paintings of Nicholas Roerich,” Russian History/Histoire Russe 30 (Fall 2003): 301-21</ref> The influence of Theosophy, ], ], and other mystical topics can be detected not only in many of Roerich's paintings but also in the many short stories and poems that Roerich wrote before and after the 1917 revolutions, including the ''Flowers of ]'' cycle, which was begun in 1907 and completed in 1921. | |||

| ]. Peaks and passes named in honor of the Roerich family]] | |||

| ===Revolution and emigration to United States=== | |||

| After some months in Finland and Scandinavia, the Roerichs moved on to ], arriving in mid-1919. Fully engrossed in Theosophical mysticism, the Roerichs were now consumed by millenarian expectations that a new age was imminent, and they wished to reach India as soon as possible. They joined the English-Welsh chapter of the Theosophical Society. It was in London, in March 1920, that the Roerichs founded their own school of occult thinking, '']'', which they also referred to as "the system of living ethics." To earn passage to India, Roerich worked as a stage designer for ]'s ], but the enterprise collapsed in 1920, and the artist never received full payment for his work. | |||

| ]. 1913]] | |||

| {{further|Yoga in Russia}} | |||

| After the ] and the end of the czarist regime, Roerich, a political moderate who valued Russia's cultural heritage more than ideology and party politics, had an active part in artistic politics. With ] and ], he participated with the so-called "Gorky Commission" and its successor organization, the Arts Union (SDI). Both attempted to gain the attention of the ] and ] on the need to form a coherent cultural policy and, most urgently, to protect art and architecture from destruction and vandalism. | |||

| Luckily, a successful exhibition led to an invitation from a director at the ], offering to arrange for Roerich's art to tour the United States. In the fall of 1920, the Roerichs set sail for America. Among the notable people Roerich befriended while in England were the famed British Buddhist ], philosopher-author ], and the poet and Nobel laureate ] (whose grand-niece ] would later marry Roerich's son Sviatoslav). | |||

| Meanwhile, illness forced Roerich to leave the capital and reside in ], the district bordering Finland. He had already quit the presidency of the World of Art society, and he now quit the directorship of the School of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. After the October Revolution and the acquisition of power of Lenin's ], Roerich became increasingly discouraged about Russia's political future. During early 1918, he, Helena, and their two sons ] and ] emigrated to Finland. | |||

| ] | |||

| Two unresolved historical debates are associated with Roerich's departure. First, it is often claimed that Roerich was a major candidate to direct a people's commissariat of culture (the Soviet equivalent of a ministry of culture), which the Bolsheviks considered establishing in 1917–1918, but he refused to accept the job. In fact, Benois was the most likely choice to direct any such commissariat. It seems that Roerich was a preferred choice to manage its department of artistic education; the topic is rendered moot by the fact that the Soviets elected not to establish such a commissariat. | |||

| The Roerichs remained in the United States from October 1920 to May 1923. A large exhibition of Roerich's art, organized in part by U.S. impresario Christian Brinton and in part by the Chicago Art Institute, opened in New York in December 1920 and toured the country, to ] and back, in 1921 and early 1922. Roerich befriended acclaimed soprano ] of the ] and received a commission to design a 1922 production of ]'s '']'' for her. During the exhibition, the Roerichs spent significant amounts of time in Chicago, New Mexico, and California. | |||

| Second, when Roerich later wished to reconcile with the Soviet Union, he maintained that he had not left Soviet Russia deliberately, but that he and his family, living in ], had been isolated from their homeland when the ] began. However, Roerich had an amply-documented extreme hostility to the Bolshevik regime, prompted not so much by a dislike of communism as by his revulsion at ]'s ruthlessness and his fear that Bolshevism would result in the destruction of Russia's artistic and architectural heritage. He illustrated ]'s anticommunist polemic "S.O.S." and had a widely-published pamphlet, "Violators of Art" (1918–1919). Roerich believed that "the triumph of Russian culture would come about through a new appreciation of ancient myth and legend."<ref>{{cite book | last=Bowlt | first=John E. | title=Moscow and St. Petersburg 1900–1920: Art, Life and Culture | publisher=The Vendome Press | year=2008 | location=New York | page=69 | isbn =978-0-86565-191-3}}</ref> | |||

| They settled in New York City, which became the base of their many American operations. The Roerichs founded several institutions during these years: ''Cor Ardens'' and ''Corona Mundi'', both of which were meant to unite artists around the globe in the cause of civic activism; the ], an art school with an exceptionally versatile curriculum, and the eventual home of the first ]; and an American Agni Yoga Society. They also joined various theosophical societies, and their activities in these groups dominated their lives. | |||

| After some months in ] and ], the Roerichs relocated to London, arriving in mid-1919. Engrossed with Theosophical mysticism, they now had ] expectations that a new age was imminent, and they wished to travel to India as soon as possible. They joined the English-Welsh chapter of the Theosophical Society. It was in London, in March 1920, that the Roerichs founded their own school of mysticism, '']'',<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.highest-yoga.info/en/yoga/agni-yoga.html |title=Agni Yoga |publisher=highest-yoga.info |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181023071905/http://www.highest-yoga.info/en/yoga/agni-yoga.html |archive-date=23 October 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> which they described as "the system of living ethics." While in London, Roerich also contributed scenic designs for ], a cooperative group of Russian theatrical artists led by ].<ref> ''The Stage'', 22 January, 1920.</ref> | |||

| ===Asian Expedition (1925-1928)=== | |||

| To earn passage to India, Roerich worked as a stage designer for ]'s ], but the enterprise ended unsuccessfully in 1920, and the artist never received full payment for his work. Among the notable people Roerich befriended while in England were the famed British Buddhist ], the philosopher-author ], and the poet and Nobel laureate ] (whose grand-niece ] would later marry Roerich's son ]). | |||

| After leaving New York, the Roerichs - together with their son George and six friends - went on the five-year long 'Roerich Asian Expedition' that, in Roerich's own words: ''"started from Sikkim through Punjab, Kashmir, Ladakh, the Karakoram Mountains, Khotan, Kashgar, Qara Shar, Urumchi, Irtysh, the Altai Mountains, the Oryot region of Mongolia, the Central Gobi, Kansu, Tsaidam, and Tibet"'' with a detour through Siberia to Moscow in 1926. Roerichs' Asian expedition attracted anxious attention from the foreign services and intelligence agencies of the USSR, the United States, Great Britain, and Japan. Between the summer of 1927 and June of 1928 the expedition was thought to be lost, since all contact from them ceased for a year. They had been attacked in Tibet and only the ''"Superiority of our firearms prevented bloodshed... In spite of our having Tibet passports, the expedition was forcibly stopped by Tibetan authorities."'' The expedition was detained by the government for five months, and forced to live in tents in sub-zero conditions and to subsist on meagre rations. Five men of the expedition died at this time. In March of 1928 they were allowed to leave Tibet, and trekked south to settle in ], where they founded a research center, the Himalayan Research Institute. | |||

| A successful exhibition in London resulted in an invitation from a director at the ], offering to arrange for Roerich's art to tour the United States. In the autumn of 1920, the Roerichs traveled to America by sea. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Cultural work=== | |||

| In 1929 Nicholas Roerich was nominated for the ] by the ].<ref>{{cite news |first= |last= |authorlink= |coauthors= |title=Roerich Nominated for Peace Award |url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FB0911F8385A127A93C1A91788D85F4D8285F9 |quote=|work=] |date=March 3, 1929 |accessdate=2009-02-03 }}</ref> He received two more nominations in 1932 and 1935.<ref></ref> His concern for peace led to his creation of the ], the "]" of art and culture. His work in this area also led the United States and the twenty other members of the ] to sign the ] on ], ] at the White House. The Roerich Pact is an early international instrument protecting cultural property. | |||

| The Roerichs remained in the United States from October 1920 until May 1923. A large exhibition of Roerich's art, organized partly by the U.S. impresario Christian Brinton and partly by the ], began in New York in December 1920 and toured the country, to San Francisco and back, in 1921 and early 1922. Roerich befriended acclaimed soprano ] of the ] and received a commission to design a 1922 production of ]'s '']'' for her. During the exhibition, the Roerichs spent significant amounts of time in Chicago, New Mexico, and California. | |||

| ] ] was a frequent correspondent and sometime follower of Roerich's teachings. This became controversial when Wallace ran for President in 1948 and portions of the letters were printed by ] columnist ]. | |||

| Politically, Roerich was at first anti-Bolshevik. He gave lectures and wrote articles to ] populations in which he criticized the ]. However, his aversion to ], "the impertinent monster that lies to humanity," changed in America. Roerich claimed that his spiritual masters, the "Mahatmas" in the ], were communicating telepathically with him through his wife, Helena, who was a mystic and a clairvoyant. | |||

| ==Cultural references== | |||

| ] referred to the "strange and disturbing paintings of Nicholas Roerich" in his Antarctic horror story '']''. | |||

| The beings from an ] community in India were said to have told Roerich that Russia was destined for a mission on Earth. That led him to formulate his "Great Plan," which envisaged the unification of millions of ] through a religious movement using the Future Buddha, or ], into a "Second Union of the East." There, the King of ] would, following the Maitreya prophecies, make his appearance to fight a great battle against all evil forces on Earth. Roerich understood that as "perfection towards Common Good." The new polity was to include southwestern ], ], ], ] and ], ] and Tibet, with its capital in "Zvenigorod," the "City of Tolling Bells," which was to be built at the foot of ], in Altai. According to Roerich, the same Mahatmas revealed to him in 1922 that he was an incarnation of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Andreyev |first=Alexandre |date=2003 |title=Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debacle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MqXnOBX4dREC |publisher=Brill |page=294 |isbn=9004129529 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| ] | |||

| Today, the ] in New York City is a major center for Roerich's artistic work. Numerous Roerich societies continue to promote his theosophical teachings worldwide. His paintings can be seen in several museums including the Roerich Department of the State Museum of Oriental Arts in Moscow; the Roerich Museum at the International Centre of the Roerichs in Moscow; the Russian State Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia; a collection in the ] in ]; a collection in the Art Museum in ], Russia; a collection in the Art Museum in ], Russia; the Roerich Hall Estate in Nagar village, Kulu Valley, Himachal-Pradesh (India); in various art museums in India; and a selection featuring several of his larger works in ]. | |||

| Roerichs' collaboration with Bolshevik diplomats and aim to gather intelligence on the British, led several scholars to place Nicholas Roerich as a participant in the British-Russian colonial ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Andreyev |first=Alexandre |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TI6fAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA198 |title=The Myth of the Masters Revived: The Occult Lives of Nikolai and Elena Roerich |date=2014-05-08 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-27043-5 |pages=198–199 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":11">{{Cite book |last=Znamenski |first=Andrei |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6J6T2uz1KSoC |title=Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia |date=2011-07-01 |publisher=Quest Books |isbn=978-0-8356-0891-6 |pages=181–182 |language=en }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2001-01-07 |title=Observer review: Tournament of Shadows by Karl Meyer and Shareen Brysac |url=http://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/jan/07/historybooks1 |access-date= |website=The Guardian |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=McCannon |first=John |date=2022 |title=Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eASZEAAAQBAJ |publisher=University of Pittsburgh Press |isbn=978-0822947417 }}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| In 1923, Roerich, the "practical idealist," set out to the Himalayas with his wife and his son Yuri. Roerich initially settled in Darjeeling in the same house that the ] had stayed during his exile in India. Roerich spent his time painting the Himalayas with visitors such as ], ], and members of the ], as well as ], ], and ], influential Tibetans. According to British intelligence, lamas from the Moru monastery recognized Roerich as the incarnation of the Fifth Dalai Lama due to a ] pattern on his right cheek. It was during his stay in the Himalayas that Roerich learned about the flight of the ], which he interpreted as the fulfillment of the Matreiya prophecies and the bringing about of the Age of Shambhala.<ref>{{cite book |last=Andreyev |first=Alexandre |date=2003 |title=Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debacle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MqXnOBX4dREC |publisher=Brill |page=295 |isbn=9004129529 }}</ref> | |||

| ] or ]]] | |||

| In 1924, the Roerichs returned to the West. On his way to America, Roerich stopped at the Soviet embassy in Berlin, where he told the local ] about a Central Asian expedition he wanted to take. He asked for Soviet protection on his way, and shared his impressions of politics in India and Tibet. Roerich commented on the "occupation of Tibet by the British" by claiming that they "infiltrate in small parties... conduct extensive anti-Soviet propaganda" by talking about "anti-religious activity of the Bolsheviks." The plenipotentiary later pointed out to one of Roerich's old university classmates, ], that he had "absolutely pro-Soviet leanings, which looked somewhat Buddho-Communistic," and that his son, who spoke 28 Asian languages, helped him in gaining the favor with the Indians and the Tibetans.<ref>AVPRF, op. 04, op. 13, papka 87, d. 50117, 1. 13a. Krestinsky to Checherin, January 2, 1925</ref> | |||

| The Roerichs settled in New York City, which became the base of their many American operations. They founded several institutions during these years: ''Cor Ardens'' ("Flaming Heart") and ''Corona Mundi'' ("Crown of the World"), both of which were meant to unite artists around the globe in the cause of civic activism; the Master Institute of United Arts, an art school with a versatile curriculum, and the eventual home of the first ]; and an American Agni Yoga Society. They also joined various theosophical societies; their activities with these groups dominated their lives. | |||

| ===Asian expedition (1925–1929)=== | |||

| ] | |||

| After leaving New York, the Roerichs, together with their son ] and six friends began the five-year Roerich Asian Expedition that in Roerich's own words "started from ] through ], ], ], the ] Mountains, ], ], ], ], ], the ], the ] region of Mongolia, the Central ], ], ], and ]" with a detour through Siberia to Moscow in 1926. | |||

| The Roerichs' Asian expedition attracted attention from the foreign services and intelligence agencies of the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. In fact, prior to this expedition, Roerich had solicited the help of the Soviet government and Bolshevik secret police to assist him in his expedition by promising in return to monitor British activities in the area, but he received only a lukewarm response from ], the chief of the Soviet foreign intelligence. | |||

| The Bolsheviks assisted Roerich with logistics while he was traveling through Siberia and Mongolia. However, they did not commit themselves to his reckless project of the Sacred Union of the East, a spiritual utopia that boiled down to Roerich's ambitious attempts to stir the Buddhist masses of inner Asia to create a highly spiritual co-operative commonwealth under the patronage of Bolshevik Russia. | |||

| The official mission of his expedition, as Roerich put it, was to act as the embassy of ] to Tibet. To the Western media, it was presented as an artistic and scientific enterprise.<ref>{{Cite web|url = https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxPIHCsXnuI|title = Andrei Znamenski, "Nicholas Roerich Shambhala Warrior"| website=] | date=May 29, 2011 }}.</ref> Roerich reported seeing a metallic oval in the sky over the Tibet; decades later, UFO enthusiasts would claim the Roerich expedition witnessed a "]".<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iJPyVjs8jrsC&pg=PA56|title=The Flying Saucers Are Real|isbn=9781585092642|last1=Keyhoe|first1=Donald|date=June 30, 2006}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3vckAQAAMAAJ|title = The Colorado Engineer|year = 1954}}</ref> | |||

| Between the summer of 1927 and June 1928, the expedition was thought to have been lost, as communication with them had ceased. They had, in fact, been attacked in Tibet. Roerich wrote that only the "superiority of our firearms prevented bloodshed.... In spite of our having Tibet passports, the expedition was forcibly stopped by Tibetan authorities." They were detained by the government for five months and were forced to live in tents in sub-zero conditions and to subsist on meagre rations. Five men of the expedition died during this time. In March 1928 they were allowed to leave Tibet, and they trekked south to settle in ], where they founded a research center, the Himalayan Research Institute. | |||

| In 1929 Roerich was nominated for the ] by the ].<ref>{{cite news |title=Roerich Nominated for Peace Award |url=https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FB0911F8385A127A93C1A91788D85F4D8285F9 |work=] |date=March 3, 1929 |access-date=February 3, 2009 }}</ref> He received two more nominations in 1932 and 1935.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://nobelprize.org/nomination/peace/nomination.php?string=Nicholas%20Roerich&action=simplesearch&submit.x=0&submit.y=0|title=Nomination Database - Peace|access-date=June 14, 2016}}</ref> ] ]'' (1932), She is seen holding the ]]] | |||

| His concern for peace resulted in his creation of the ], the "]" of art and culture. His work for this cause also resulted in the United States and the 20 other nations of the ] signing the ], an early international instrument protecting cultural property, on April 15, 1935 at the White House. | |||

| ===Manchurian expedition=== | |||

| In 1934–1935, the ], then headed by the Roerich admirer ], sponsored an expedition conducted by Roerich, his wife ], and its scientists H. G. MacMillan and James F. Stephens to ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite journal |author-last=Boyd |author-first=James |date=January 2012 |title=In Search of Shambhala? Nicholas Roerich's 1934–5 Inner Mongolian Expedition |journal=Inner Asia |location=] and ] |publisher=] |volume=14 |issue=2 |pages=257–277 |doi=10.1163/22105018-90000004 |issn=2210-5018 |jstor=24572064}}</ref> The expedition's purpose was to collect seeds of plants which prevented ]. | |||

| The expedition consisted of two parts. In 1934, they explored the ] mountains and Bargan plateau in western Manchuria. In 1935, they explored parts of Inner Mongolia: the ], ], and ]. The expedition found almost 300 species of ]s, collected herbs, conducted archeological studies, and found antique manuscripts of great scientific importance. | |||

| === Later life === | |||

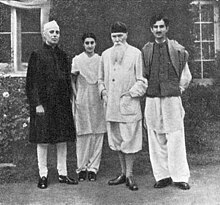

| ], ], Nicholas Roerich, and ]. (Roerich's estate, Kullu).]] | |||

| ], 1947]] | |||

| Roerich was in India during World War II, where he painted Russian epic heroic and saintly themes, including ''Alexander Nevsky'', ''The Fight of Mstislav and Rededia,'' and ''Boris and Gleb''.<ref name="Leek2005">{{cite book |author=Peter Leek |title=Russian Painting |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ePYhUnX4vgUC&pg=PA256 |access-date=June 23, 2013 |year=2005 |publisher=Parkstone International |isbn=978-1-78042-975-5 |pages=256–}}</ref> | |||

| In 1942, Roerich received ] and his daughter, ], at his house in ].{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} Together they discussed the fate of the new world: "We spoke about Indian–Russian cultural association it is time to think about useful and creative co-operation."<ref>N. Roerich. Diary Leaves. V. 3. – Moscow, International Centre of the Roerichs. – 1996. – p.39. {{ISBN|5-86988-056-4}}</ref> | |||

| Indira Gandhi would later recall several days spent together with Roerich's family: "That was a memorable visit to a surprising and gifted family where each member was a remarkable figure in himself, with a well-defined range of interests.... Roerich himself stays in my memory. He was a man with extensive knowledge and enormous experience, a man with a big heart, deeply influenced by all that he observed." | |||

| During the visit, "ideas and thoughts about closer co-operation between India and USSR were expressed. Now, after India wins independence, they have got its own real implementation{{clarify|phrase after the comma is totally unclear|date=June 2013}}. And as you know, there are friendly and mutually-understanding relationships today between both our countries."<ref name="Индира Ганди"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091212022537/http://lib.roerich-museum.ru/node/769 |date=December 12, 2009 }} / Roerich's Empire. (Derzhava Rerikhov) (in Russian). / Collected Articles. – Moscow, International Centre of the Roerichs, Master-Bank. – 2004. – p.65. {{ISBN|5-86988-148-X}}</ref> | |||

| In 1942, the American–Russian cultural Association (ARCA) was created in New York. Its active participants were ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Its activity was welcomed by scientists such as ] and ].<ref name="Drayer2005">{{cite book |author=Ruth Abrams Drayer |title=Nicholas and Helena Roerich: The Spiritual Journey of Two Great Artists and Peacemakers |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yIoY64HNGysC&pg=PA330 |access-date=June 23, 2013 |year=2005 |publisher=Quest Books |isbn=978-0-8356-0843-5 |pages=330– }}</ref> | |||

| Roerich had a lengthy correspondence with Henry Wallace, the 1948 Progressive Party candidate for US president. | |||

| ==Death== | |||

| Roerich died in ] on December 13, 1947.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |author = Madhukar, J. | |||

| |url = https://bangaloremirror.indiatimes.com/opinion/sunday-read/remembering-roerich/articleshow/71668952.cms | |||

| |title = Remembering Roerich | |||

| |publisher = ‘The Bangalore Mirror’ | |||

| |date = October 20, 2019 | |||

| |access-date = January 29, 2020 | |||

| }}</ref> His wife, philosopher | |||

| ], wrote about this day: “The day of cremation was exceptionally beautiful. Not a single breath of wind and all surrounding mountains were clad in fresh snowy attire.”<ref>{{cite web |author=Kamalakaran, A. |url=https://www.rbth.com/articles/2012/05/02/nicholas_roerichs_legacy_lives_on_in_himalayan_hamlet_15652 |title=Nicholas Roerich's legacy lives on in Himalayan Hamlet |date=2 May 2012 |access-date=21 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220621124431/https://www.rbth.com/articles/2012/05/02/nicholas_roerichs_legacy_lives_on_in_himalayan_hamlet_15652|archive-date=21 June 2022|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Cultural legacy== | |||

| ]. Peaks and passes named in honor of the Roerich family.]] | |||

| ] in Solar System]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| In the 21st century, the ] in New York City is a major institution for Roerich's artistic work. Numerous Roerich societies continue to promote his theosophical teachings worldwide. His paintings can be seen in several museums including the Roerich Department of the State Museum of Oriental Arts in Moscow; the Roerich Museum at the International Centre of the Roerichs in Moscow; the Russian State Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia; a collection in the ] in Moscow; a collection in the Art Museum in ], Russia; an important collection in the ] in ], ]; a collection in the Art Museum in ] Russia; ]; the Roerich Hall Estate in ], ]; the ], ], India;<ref>{{Cite news|url = http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Thiruvananthapuram/dust-throws-a-blanket-over-prized-paintings/article4639568.ece|title = Dust throws a blanket over prized paintings| website=] | date=April 21, 2013 }}.</ref> in various art museums in India; and a selection featuring several of his larger works in ]. A memorial plaque marks the house in Lahaul valley where Roerich lived during summers from 1929 to 1932.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Roerich In Lahul |url=https://roerichinlahul.info/ |access-date=2022-11-08 |website=Roerich In Lahul |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Roerich's biography and his controversial expeditions to Tibet and Manchuria have been examined recently by a number of authors, including two Russians, Vladimir Rosov and Alexandre Andreyev, two Americans (Andrei Znamenski and John McCannon), and the German Ernst von Waldenfels.<ref>Nicholas Roerich: the Messenger of Zvenigorod (vol. 1: The Great Plan, vol. 2: The New Country) (2002–2004) ; Alexandre Andreyev, Gimalaiski mif i ego tvotry (St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg University Press, 2004) ; Andrei Znamenski, Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophesy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia (Quest Books, 2011); John McCannon, Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022) ; John McCannon, "Searching for Shambhala: The Mystical Art and Epic Journeys of Nikolai Roerich," Russian Life (January–February 2001); John McCannon, "By the Shores of White Waters: The Altai and Its Place in the Spiritual Geopolitics of Nicholas Roerich,” Sibirica: Journal of Siberian Studies (October 2002) ; Ernst von Waldenfels, Nicholas Roerich: Kunst, Macht und Okkultismus (Osburg, 2011)</ref> | |||

| A series of his studies on the Himalayan Ranges-donated by the artist's son (36 works specifically) are even showcased in the Nicholas Roerich Gallery of the Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath Museum based in Bangalore, India. The hypnotic, immersive nature of his works truly absorbs the onlooker, leaving one with a sense of peace and tranquility as one moves with the series through the gallery. | |||

| ] describes Roerich's paintings of Asian mountain landscapes as "strange and disturbing" numerous times in his Antarctic horror story '']''.<ref>{{cite book |last=McCannon |first=John |date=2022 |title=Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eASZEAAAQBAJ |publisher=University of Pittsburgh Press |page=366-67 |isbn=978-0822947417 }}</ref> | |||

| Roerich was awarded ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Radulovic|first=Nemanja|title=Rerihov pokret u Kraljevini Jugoslaviji|url=https://www.academia.edu/30928970|journal=Godišnjak Katedre za srpsku književnost sa južnoslovenskim književnostima, XI, 2016|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.vreme.com/cms/view.php?id=1669255&print=yes|title=Vreme - Kultura i politika: Selidba trajne pozajmice|website=www.vreme.com|date=February 27, 2019 |access-date=July 11, 2019}}</ref> The ] ] in the ] was named in honor of Roerich. ] on ], near the south pole, is also named for Roerich.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Feature/15105 |title = Roerich |publisher = ] |work = Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature |accessdate = 23 March 2020}}</ref> | |||

| In June 2013 during ] in London, Roerich's ''Madonna Laboris'' sold at auction at ] shop for £7,881,250, including the buyer's premium, making it the most valuable painting ever sold at a Russian art auction.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/20841/lot/63/|title=Bonhams : Nikolai Konstantinovich Roerich (Russian, 1874-1947) Madonna Laboris|access-date=June 14, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ==Gallery== | |||

| <gallery mode="nolines" widths="185"> | |||

| File:Roerich 01 Messenger.jpg|''Messenger'', 1897 | |||

| File:Treasure of angels.jpg|''Treasure of angels,'' 1905 | |||

| File:Roerich Rite of Spring.jpg|''Kiss to the Earth'', 1912, scenery for ]’s '']'' ballet | |||

| File:Николай К. Рерих - Песнь Сольвейг (1912).jpg|''Solveig's Song'', 1912 | |||

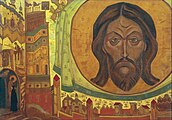

| File:Saint Olga by Nicholas Roerich - 1915.jpg|'']'', 1915 | |||

| File:Николай К. Рерих - Пантелеймон-целитель (1916).jpg|'']'', 1916 | |||

| File:N. Roerich - And We See. From the «Sancta» Series - Google Art Project.jpg|''And We See'', from the "Sancta" Series, 1922 | |||

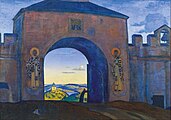

| File:N. Roerich - And We are Opening the Gates. From the «Sancta» Series - Google Art Project.jpg|''And We Are Opening the Gates'', from the "Sancta" Series, 1922 | |||

| File:N. Roerich - Monhegan. Maine - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'', 1922 | |||

| File:N. Roerich - The Messenger - Google Art Project.jpg|''The Messenger'', 1922 | |||

| File:N. Roerich - And We are Trying. From the «Sancta» Series - Google Art Project.jpg|''And We Are Trying'', from the "Sancta" Series, 1922 | |||

| File:Roerich Book.jpg|''The Pigeon Book'' (pigeon being used as an adjective), 1922 | |||

| File:Yama no ue.jpg|''Yama no Ue'' (Japanese, {{Literally|Atop the Mountain}}), from the "His Country" series, 1924 | |||

| File:On-the-way-to-shekar-dzong-1928.jpg!PinterestLarge.jpg|''On the Way to Shelkar Dzong'', 1928 | |||

| File:Sunset-near-shekar-1928.jpg!PinterestLarge.jpg|''Sunset near Shelkar,'' 1928 | |||

| File:Shekar zongu.jpg|], 1928 | |||

| File:Madonna Protectoris.jpg|]'', 1933 | |||

| File:Shekar-dzong-1933.jpg!PinterestLarge.jpg|1933 ''Shelkar Dzong'' (fortress) and monastery | |||

| File:Sky power.jpg|''Sky power'', 1934 | |||

| File:Kampa-dzong-pink-peak-1938.jpg!PinterestLarge.jpg|''] Pink Peak,'' 1938 | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| {{Listen | |||

| |filename = "About Shambala" N.Roerich.ogg | |||

| |title = N. K. Roerich. About Shambala | |||

| |description = Phonogram of 1929. | |||

| }} | |||

| == Major works == | |||

| # Art and archaeology // Art and art industry. SPb., 1898. No. 3; 1899. No. 4-5. | |||

| # Some ancient Shelonsky fifths and Bezhetsky end. SPb., 31 pages, drawings of the author, 1899. | |||

| # Excursion of the Archaeological Institute in 1899 in connection with the question of the Finnish burials of St. Petersburg province. SPb., 14 p., 1900. | |||

| # Some ancient stains Derevsky and Bezhetsk. SPb., 30 p., 1903. | |||

| # In the old days, St. Petersburg., 1904,18 p., drawings of the author. | |||

| # Stone age on lake piros., SPb., ed. "Russian archaeological society", 1905. | |||

| # Collected works. kN. 1. M.: publishing house of I. D. Sytin, p. 335, 1914. | |||

| # Tales and parables. Pg.: Free art, 1916. | |||

| # Violators of Art. London, 1919. | |||

| # The Flowers Of Moria. . Berlin: Word, 128 p., Collection of poems. 1921. | |||

| # Adamant. New York: Corona Mundi, 1922 | |||

| # Ways Of Blessing. New York, Paris, Riga, Harbin: Alatas, 1924 | |||

| # Altai - Himalayas. (Thoughts on a horse and in a tent) 1923–1926. Ulan Bator Khoto, 1927. | |||

| # Heart of Asia. Southbury (St. Connecticut): Alatas, 1929. | |||

| # Flame in Chalice. Series X, Book 1. Songs and Sagas Series. New York: Roerich Museum Press, 1930. | |||

| # Shambhala. New York: F. A. Stokes Co., 1930 | |||

| # Realm of Light. Series IX, Book II. Sayings of Eternity Series. New York: Roerich Museum Press, 1931. | |||

| # The Power Of Light. Southbury: Alatas, New York, 1931. | |||

| # Women. Address on the occasion of the opening of the Association of women, Riga, ed. About Roerich, 1931, 15 p., 1 reproduction. | |||

| # The Fiery Stronghold. Paris: World League Of Culture, 1932. | |||

| # Banner of peace. Harbin, Alatyr, 1934. | |||

| # Holy Watch. Harbin, Alatyr, 1934. | |||

| # A gateway to the Future. Riga: Uguns, 1936. | |||

| # Indestructible. Riga: Uguns, 1936. | |||

| # Roerich Essays: One hundred essays. В 2 т. India, 1937. | |||

| # Beautiful Unity. Bombey, 1946. | |||

| # Himavat: Diary Leaveves. Allahabad: Kitabistan, 1946. | |||

| # Himalayas — Adobe of Light. Bombey: Nalanda Publ, 1947. | |||

| # Diary sheets. Vol. 1 (1934-1935). M: ICR, 1995. | |||

| # Diary sheets. Vol. 2 (1936-1941). M: ICR, 1995. | |||

| # Diary sheets. Vol. 3 (1942-1947). M: ICR, 1996. | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{columns-list|colwidth=20em| | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] — President of International Centre of the Roerichs (]) | |||

| }} | |||

| * ] — Minor planet in Solar System | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{wikiquote}} | {{wikiquote}} | ||

| {{ |

{{commons category|Nicholas Roerich}} | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160312080403/http://histclo.com/art/ind/r/ro/roer/roer-fam.html |date=March 12, 2016 }} | ||

| *{{Find a Grave|105420902}} | |||

| * | |||

| * at the ] | |||

| *, J Murrey Atkins Library, UNC Charlotte | |||

| * | |||

| *, ISFP Gallery of Russian Thinkers | |||

| * | |||

| {{Nicholas Roerich|state=expanded}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Theosophy series}} | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Roerich, Nicholas}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Roerich, Nicholas}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Roerich, Nicholas}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 03:32, 12 December 2024

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (October 2023) Click for important translation instructions.

|

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Nicholas Roerich" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Nicholas Roerich | |

|---|---|

| Николай Рерих | |

Roerich c. 1940–1947 Roerich c. 1940–1947 | |

| Born | (1874-10-09)October 9, 1874 Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | December 13, 1947(1947-12-13) (aged 73) Naggar, Dominion of India |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation(s) | painter, archaeologist, costume and set designer for ballets, operas, and dramas |

| Spouse | Helena Roerich |

| Children | George de Roerich, Svetoslav Roerich |

| Signature | |

| |

Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (Russian: Николай Константинович Рерих), better known as Nicholas Roerich (/ˈrɛrɪk/; October 9, 1874 – December 13, 1947), was a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophist, philosopher, and public figure. In his youth he was influenced by Russian Symbolism, a movement in Russian society centered on the spiritual. He was interested in hypnosis and other spiritual practices and his paintings are said to have hypnotic expression.

Born in Saint Petersburg, to a well-to-do Baltic German father and to a Russian mother, Roerich lived in various places in the world until his death in Naggar, India. Trained as an artist and a lawyer, his main interests were literature, philosophy, archaeology, and especially art. Roerich was a dedicated activist for the cause of preserving art and architecture during times of war. He was nominated several times to the longlist for the Nobel Peace Prize. The so-called Roerich Pact (for the protection of cultural objects) was signed into law by the United States and most other nations of the Pan-American Union in April 1935.

Biography

Early life

Raised in late-19th-century St. Petersburg, Roerich enrolled simultaneously at St. Petersburg University and the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1893. He received the title of "artist" in 1897 and a degree in law the next year. He found early employment with the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, whose school he directed from 1906 to 1917. Despite early tensions with the group, he became a member of Sergei Diaghilev's "World of Art" society and was its president from 1910 to 1916.

Artistically, Roerich became known as his generation's most talented painter of Russia's ancient past, a topic that was compatible with his lifelong interest in archeology. He also succeeded as a stage designer by achieving his greatest fame as one of the designers for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. His best-known designs were for Alexander Borodin's Prince Igor (1909 and later productions), and costumes and set for The Rite of Spring (1913), composed by Igor Stravinsky.

Along with Mikhail Vrubel and Mikhail Nesterov, Roerich is considered a major representative of Russian Symbolism in art. From an early period of his life, he was influenced by apocrypha and medieval sectarian writings such as the mysterious Dove Book.

Another of Roerich's artistic subjects was architecture. His acclaimed publication "Architectural Studies" (1904–1905), consisting of dozens of paintings he made of fortresses, monasteries, churches, and other monuments during two long trips through Russia, inspired his decades-long career as an activist on behalf of artistic and architectural preservation. He also designed religious art for places of worship throughout Russia and Ukraine, most notably the Queen of Heaven fresco for the Church of the Holy Spirit, which the patroness Maria Tenisheva built near her Talashkino estate, and the stained glass windows for the Datsan Gunzechoinei in 1913–1915. His designs for the Talashkino church were so radical that the Orthodox church refused to consecrate the building.

During the first decade of the 1900s and in the early 1910s, Roerich, largely by the influence of his wife, Helena, developed an interest in eastern religions, as well as alternative belief systems such as Theosophy. Both Roerichs became avid readers of the Vedantist essays of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda, the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore, and the Bhagavad Gita.

The Roerichs' commitment to occult mysticism increased steadily. It was especially intense during World War I and the 1917 Russian Revolution to which the couple, like other many Russian intellectuals, accorded apocalyptic significance. The influence of Theosophy, Vedanta, Buddhism, and other mystical topics can be detected not only in many of Roerich's paintings but also in the many short stories and poems that Roerich wrote before and after the 1917 revolutions, including the Flowers of Morya cycle, which was begun in 1907 and completed in 1921.

Revolution and emigration to United States

After the February Revolution of 1917 and the end of the czarist regime, Roerich, a political moderate who valued Russia's cultural heritage more than ideology and party politics, had an active part in artistic politics. With Maxim Gorky and Aleksandr Benois, he participated with the so-called "Gorky Commission" and its successor organization, the Arts Union (SDI). Both attempted to gain the attention of the Provisional Government and Petrograd Soviet on the need to form a coherent cultural policy and, most urgently, to protect art and architecture from destruction and vandalism.

Meanwhile, illness forced Roerich to leave the capital and reside in Karelia, the district bordering Finland. He had already quit the presidency of the World of Art society, and he now quit the directorship of the School of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. After the October Revolution and the acquisition of power of Lenin's Bolshevik Party, Roerich became increasingly discouraged about Russia's political future. During early 1918, he, Helena, and their two sons George and Svetoslav emigrated to Finland.

Two unresolved historical debates are associated with Roerich's departure. First, it is often claimed that Roerich was a major candidate to direct a people's commissariat of culture (the Soviet equivalent of a ministry of culture), which the Bolsheviks considered establishing in 1917–1918, but he refused to accept the job. In fact, Benois was the most likely choice to direct any such commissariat. It seems that Roerich was a preferred choice to manage its department of artistic education; the topic is rendered moot by the fact that the Soviets elected not to establish such a commissariat.

Second, when Roerich later wished to reconcile with the Soviet Union, he maintained that he had not left Soviet Russia deliberately, but that he and his family, living in Karelia, had been isolated from their homeland when the Finnish Civil War began. However, Roerich had an amply-documented extreme hostility to the Bolshevik regime, prompted not so much by a dislike of communism as by his revulsion at Lenin's ruthlessness and his fear that Bolshevism would result in the destruction of Russia's artistic and architectural heritage. He illustrated Leonid Andreyev's anticommunist polemic "S.O.S." and had a widely-published pamphlet, "Violators of Art" (1918–1919). Roerich believed that "the triumph of Russian culture would come about through a new appreciation of ancient myth and legend."

After some months in Finland and Scandinavia, the Roerichs relocated to London, arriving in mid-1919. Engrossed with Theosophical mysticism, they now had millenarian expectations that a new age was imminent, and they wished to travel to India as soon as possible. They joined the English-Welsh chapter of the Theosophical Society. It was in London, in March 1920, that the Roerichs founded their own school of mysticism, Agni Yoga, which they described as "the system of living ethics." While in London, Roerich also contributed scenic designs for LAHDA, a cooperative group of Russian theatrical artists led by Theodore Komisarjevsky.

To earn passage to India, Roerich worked as a stage designer for Thomas Beecham's Covent Garden Theatre, but the enterprise ended unsuccessfully in 1920, and the artist never received full payment for his work. Among the notable people Roerich befriended while in England were the famed British Buddhist Christmas Humphreys, the philosopher-author H. G. Wells, and the poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (whose grand-niece Devika Rani would later marry Roerich's son Svetoslav).

A successful exhibition in London resulted in an invitation from a director at the Art Institute of Chicago, offering to arrange for Roerich's art to tour the United States. In the autumn of 1920, the Roerichs traveled to America by sea.

The Roerichs remained in the United States from October 1920 until May 1923. A large exhibition of Roerich's art, organized partly by the U.S. impresario Christian Brinton and partly by the Chicago Art Institute, began in New York in December 1920 and toured the country, to San Francisco and back, in 1921 and early 1922. Roerich befriended acclaimed soprano Mary Garden of the Chicago Opera and received a commission to design a 1922 production of Rimsky-Korsakov's The Snow Maiden for her. During the exhibition, the Roerichs spent significant amounts of time in Chicago, New Mexico, and California.

Politically, Roerich was at first anti-Bolshevik. He gave lectures and wrote articles to White Russian populations in which he criticized the Soviet Union. However, his aversion to communism, "the impertinent monster that lies to humanity," changed in America. Roerich claimed that his spiritual masters, the "Mahatmas" in the Himalayas, were communicating telepathically with him through his wife, Helena, who was a mystic and a clairvoyant.

The beings from an esoteric Buddhist community in India were said to have told Roerich that Russia was destined for a mission on Earth. That led him to formulate his "Great Plan," which envisaged the unification of millions of Asian peoples through a religious movement using the Future Buddha, or Maitreya, into a "Second Union of the East." There, the King of Shambhala would, following the Maitreya prophecies, make his appearance to fight a great battle against all evil forces on Earth. Roerich understood that as "perfection towards Common Good." The new polity was to include southwestern Altai, Tuva, Buryatia, Outer and Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet, with its capital in "Zvenigorod," the "City of Tolling Bells," which was to be built at the foot of Mount Belukha, in Altai. According to Roerich, the same Mahatmas revealed to him in 1922 that he was an incarnation of the Fifth Dalai Lama.

Roerichs' collaboration with Bolshevik diplomats and aim to gather intelligence on the British, led several scholars to place Nicholas Roerich as a participant in the British-Russian colonial Great Game.

In 1923, Roerich, the "practical idealist," set out to the Himalayas with his wife and his son Yuri. Roerich initially settled in Darjeeling in the same house that the 13th Dalai Lama had stayed during his exile in India. Roerich spent his time painting the Himalayas with visitors such as Frederick Marshman Bailey, Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton, and members of the 1924 British Everest Expedition, as well as Sonam Wangfel Laden La, Kusho Doring, and Tsarong Shape, influential Tibetans. According to British intelligence, lamas from the Moru monastery recognized Roerich as the incarnation of the Fifth Dalai Lama due to a mole pattern on his right cheek. It was during his stay in the Himalayas that Roerich learned about the flight of the 9th Panchen Lama, which he interpreted as the fulfillment of the Matreiya prophecies and the bringing about of the Age of Shambhala.

In 1924, the Roerichs returned to the West. On his way to America, Roerich stopped at the Soviet embassy in Berlin, where he told the local plenipotentiary about a Central Asian expedition he wanted to take. He asked for Soviet protection on his way, and shared his impressions of politics in India and Tibet. Roerich commented on the "occupation of Tibet by the British" by claiming that they "infiltrate in small parties... conduct extensive anti-Soviet propaganda" by talking about "anti-religious activity of the Bolsheviks." The plenipotentiary later pointed out to one of Roerich's old university classmates, Georgy Chicherin, that he had "absolutely pro-Soviet leanings, which looked somewhat Buddho-Communistic," and that his son, who spoke 28 Asian languages, helped him in gaining the favor with the Indians and the Tibetans.

The Roerichs settled in New York City, which became the base of their many American operations. They founded several institutions during these years: Cor Ardens ("Flaming Heart") and Corona Mundi ("Crown of the World"), both of which were meant to unite artists around the globe in the cause of civic activism; the Master Institute of United Arts, an art school with a versatile curriculum, and the eventual home of the first Nicholas Roerich Museum; and an American Agni Yoga Society. They also joined various theosophical societies; their activities with these groups dominated their lives.

Asian expedition (1925–1929)

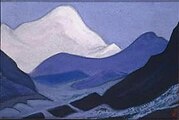

After leaving New York, the Roerichs, together with their son George and six friends began the five-year Roerich Asian Expedition that in Roerich's own words "started from Sikkim through Punjab, Kashmir, Ladakh, the Karakoram Mountains, Khotan, Kashgar, Qara Shar, Urumchi, Irtysh, the Altai Mountains, the Oyrot region of Mongolia, the Central Gobi, Kansu, Tsaidam, and Tibet" with a detour through Siberia to Moscow in 1926.

The Roerichs' Asian expedition attracted attention from the foreign services and intelligence agencies of the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. In fact, prior to this expedition, Roerich had solicited the help of the Soviet government and Bolshevik secret police to assist him in his expedition by promising in return to monitor British activities in the area, but he received only a lukewarm response from Mikhail Trilisser, the chief of the Soviet foreign intelligence.

The Bolsheviks assisted Roerich with logistics while he was traveling through Siberia and Mongolia. However, they did not commit themselves to his reckless project of the Sacred Union of the East, a spiritual utopia that boiled down to Roerich's ambitious attempts to stir the Buddhist masses of inner Asia to create a highly spiritual co-operative commonwealth under the patronage of Bolshevik Russia.

The official mission of his expedition, as Roerich put it, was to act as the embassy of Western Buddhism to Tibet. To the Western media, it was presented as an artistic and scientific enterprise. Roerich reported seeing a metallic oval in the sky over the Tibet; decades later, UFO enthusiasts would claim the Roerich expedition witnessed a "flying saucer".

Between the summer of 1927 and June 1928, the expedition was thought to have been lost, as communication with them had ceased. They had, in fact, been attacked in Tibet. Roerich wrote that only the "superiority of our firearms prevented bloodshed.... In spite of our having Tibet passports, the expedition was forcibly stopped by Tibetan authorities." They were detained by the government for five months and were forced to live in tents in sub-zero conditions and to subsist on meagre rations. Five men of the expedition died during this time. In March 1928 they were allowed to leave Tibet, and they trekked south to settle in India, where they founded a research center, the Himalayan Research Institute.

In 1929 Roerich was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the University of Paris. He received two more nominations in 1932 and 1935.

His concern for peace resulted in his creation of the Pax Cultura, the "Red Cross" of art and culture. His work for this cause also resulted in the United States and the 20 other nations of the Pan-American Union signing the Roerich Pact, an early international instrument protecting cultural property, on April 15, 1935 at the White House.

Manchurian expedition

In 1934–1935, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, then headed by the Roerich admirer Henry A. Wallace, sponsored an expedition conducted by Roerich, his wife Helena, and its scientists H. G. MacMillan and James F. Stephens to Inner Mongolia, Manchuria, and mainland China. The expedition's purpose was to collect seeds of plants which prevented soil erosion.

The expedition consisted of two parts. In 1934, they explored the Greater Khingan mountains and Bargan plateau in western Manchuria. In 1935, they explored parts of Inner Mongolia: the Gobi Desert, Ordos Desert, and Helan Mountains. The expedition found almost 300 species of xerophytes, collected herbs, conducted archeological studies, and found antique manuscripts of great scientific importance.

Later life

Roerich was in India during World War II, where he painted Russian epic heroic and saintly themes, including Alexander Nevsky, The Fight of Mstislav and Rededia, and Boris and Gleb.

In 1942, Roerich received Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter, Indira Gandhi, at his house in Kullu. Together they discussed the fate of the new world: "We spoke about Indian–Russian cultural association it is time to think about useful and creative co-operation."

Indira Gandhi would later recall several days spent together with Roerich's family: "That was a memorable visit to a surprising and gifted family where each member was a remarkable figure in himself, with a well-defined range of interests.... Roerich himself stays in my memory. He was a man with extensive knowledge and enormous experience, a man with a big heart, deeply influenced by all that he observed."

During the visit, "ideas and thoughts about closer co-operation between India and USSR were expressed. Now, after India wins independence, they have got its own real implementation. And as you know, there are friendly and mutually-understanding relationships today between both our countries."

In 1942, the American–Russian cultural Association (ARCA) was created in New York. Its active participants were Ernest Hemingway, Rockwell Kent, Charlie Chaplin, Emil Cooper, Serge Koussevitzky, and Valeriy Ivanovich Tereshchenko. Its activity was welcomed by scientists such as Robert Millikan and Arthur Compton.

Roerich had a lengthy correspondence with Henry Wallace, the 1948 Progressive Party candidate for US president.

Death

Roerich died in Kullu on December 13, 1947. His wife, philosopher Helena Roerich, wrote about this day: “The day of cremation was exceptionally beautiful. Not a single breath of wind and all surrounding mountains were clad in fresh snowy attire.”

Cultural legacy

In the 21st century, the Nicholas Roerich Museum in New York City is a major institution for Roerich's artistic work. Numerous Roerich societies continue to promote his theosophical teachings worldwide. His paintings can be seen in several museums including the Roerich Department of the State Museum of Oriental Arts in Moscow; the Roerich Museum at the International Centre of the Roerichs in Moscow; the Russian State Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia; a collection in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow; a collection in the Art Museum in Novosibirsk, Russia; an important collection in the National Gallery for Foreign Art in Sofia, Bulgaria; a collection in the Art Museum in Nizhny Novgorod Russia; National Museum of Serbia; the Roerich Hall Estate in Naggar, India; the Sree Chitra Art Gallery, Thiruvananthapuram, India; in various art museums in India; and a selection featuring several of his larger works in The Latvian National Museum of Art. A memorial plaque marks the house in Lahaul valley where Roerich lived during summers from 1929 to 1932.

Roerich's biography and his controversial expeditions to Tibet and Manchuria have been examined recently by a number of authors, including two Russians, Vladimir Rosov and Alexandre Andreyev, two Americans (Andrei Znamenski and John McCannon), and the German Ernst von Waldenfels.

A series of his studies on the Himalayan Ranges-donated by the artist's son (36 works specifically) are even showcased in the Nicholas Roerich Gallery of the Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath Museum based in Bangalore, India. The hypnotic, immersive nature of his works truly absorbs the onlooker, leaving one with a sense of peace and tranquility as one moves with the series through the gallery.

H. P. Lovecraft describes Roerich's paintings of Asian mountain landscapes as "strange and disturbing" numerous times in his Antarctic horror story At the Mountains of Madness.

Roerich was awarded Order of St. Sava. The minor planet 4426 Roerich in the Solar System was named in honor of Roerich. A crater on Mercury, near the south pole, is also named for Roerich.

In June 2013 during Russian Art Week in London, Roerich's Madonna Laboris sold at auction at Bonhams shop for £7,881,250, including the buyer's premium, making it the most valuable painting ever sold at a Russian art auction.

Gallery

-

Messenger, 1897

Messenger, 1897

-

Treasure of angels, 1905

Treasure of angels, 1905

-

Kiss to the Earth, 1912, scenery for Diaghilev’s The Rite of Spring ballet

Kiss to the Earth, 1912, scenery for Diaghilev’s The Rite of Spring ballet

-

Solveig's Song, 1912

Solveig's Song, 1912

-

Saint Olga, 1915

Saint Olga, 1915

-

Saint Pantaleon, 1916

Saint Pantaleon, 1916

-

And We See, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

And We See, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

-

And We Are Opening the Gates, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

And We Are Opening the Gates, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

-

Monhegan, Maine, 1922

Monhegan, Maine, 1922

-

The Messenger, 1922

The Messenger, 1922

-

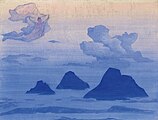

And We Are Trying, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

And We Are Trying, from the "Sancta" Series, 1922

-

The Pigeon Book (pigeon being used as an adjective), 1922

The Pigeon Book (pigeon being used as an adjective), 1922

-

Yama no Ue (Japanese, lit. 'Atop the Mountain'), from the "His Country" series, 1924

Yama no Ue (Japanese, lit. 'Atop the Mountain'), from the "His Country" series, 1924

-

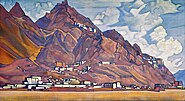

On the Way to Shelkar Dzong, 1928

On the Way to Shelkar Dzong, 1928

-

Sunset near Shelkar, 1928

Sunset near Shelkar, 1928

-

Shelkar Dzong, 1928

Shelkar Dzong, 1928

-

Madonna Protectoris, 1933

Madonna Protectoris, 1933

-

1933 Shelkar Dzong (fortress) and monastery

1933 Shelkar Dzong (fortress) and monastery

-

Sky power, 1934

Sky power, 1934

-

Kampa Dzong Pink Peak, 1938

Kampa Dzong Pink Peak, 1938

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Major works

- Art and archaeology // Art and art industry. SPb., 1898. No. 3; 1899. No. 4-5.

- Some ancient Shelonsky fifths and Bezhetsky end. SPb., 31 pages, drawings of the author, 1899.

- Excursion of the Archaeological Institute in 1899 in connection with the question of the Finnish burials of St. Petersburg province. SPb., 14 p., 1900.

- Some ancient stains Derevsky and Bezhetsk. SPb., 30 p., 1903.

- In the old days, St. Petersburg., 1904,18 p., drawings of the author.

- Stone age on lake piros., SPb., ed. "Russian archaeological society", 1905.

- Collected works. kN. 1. M.: publishing house of I. D. Sytin, p. 335, 1914.

- Tales and parables. Pg.: Free art, 1916.

- Violators of Art. London, 1919.

- The Flowers Of Moria. . Berlin: Word, 128 p., Collection of poems. 1921.

- Adamant. New York: Corona Mundi, 1922

- Ways Of Blessing. New York, Paris, Riga, Harbin: Alatas, 1924

- Altai - Himalayas. (Thoughts on a horse and in a tent) 1923–1926. Ulan Bator Khoto, 1927.

- Heart of Asia. Southbury (St. Connecticut): Alatas, 1929.

- Flame in Chalice. Series X, Book 1. Songs and Sagas Series. New York: Roerich Museum Press, 1930.

- Shambhala. New York: F. A. Stokes Co., 1930

- Realm of Light. Series IX, Book II. Sayings of Eternity Series. New York: Roerich Museum Press, 1931.

- The Power Of Light. Southbury: Alatas, New York, 1931.

- Women. Address on the occasion of the opening of the Association of women, Riga, ed. About Roerich, 1931, 15 p., 1 reproduction.

- The Fiery Stronghold. Paris: World League Of Culture, 1932.

- Banner of peace. Harbin, Alatyr, 1934.

- Holy Watch. Harbin, Alatyr, 1934.

- A gateway to the Future. Riga: Uguns, 1936.

- Indestructible. Riga: Uguns, 1936.

- Roerich Essays: One hundred essays. В 2 т. India, 1937.

- Beautiful Unity. Bombey, 1946.

- Himavat: Diary Leaveves. Allahabad: Kitabistan, 1946.

- Himalayas — Adobe of Light. Bombey: Nalanda Publ, 1947.

- Diary sheets. Vol. 1 (1934-1935). M: ICR, 1995.

- Diary sheets. Vol. 2 (1936-1941). M: ICR, 1995.

- Diary sheets. Vol. 3 (1942-1947). M: ICR, 1996.

See also

Notes

- Also spelled as Ryorikh, from Russian: Рёрих

References

- Nicholas Roerich: In Search of Shambala by Victoria Klimentieva, стр. 31

- Nicholas Roerich Museum Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Andrei Znamenski, Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia, Quest Books (2011), p. 157

- "Nicholas Roerich - Russian set designer". Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Nobel Prize Nomination Database

- McCannon, John (2022). Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 107-12. ISBN 978-0822947417.

- Julie Besonen, "Visions of a Forgotten Utopian", New York Times, April 6, 2014.

- McCannon, John (2022). Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 121-64. ISBN 978-0822947417.

- ^ Hardiman, Louise; Kozicharow, Nicola (November 13, 2017). Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives. Open Book Publishers. ISBN 9781783743414.

- Н. В. Сергеева. Древнерусская традиция в символизме Н.К. Рериха. М.: Международный Центр Рерихов, 2003. ISBN 5-86988-080-7. Page 87.

- John McCannon, "Apocalypse and Tranquility: The World War I Paintings of Nicholas Roerich,” Russian History/Histoire Russe 30 (Fall 2003): 301-21

- Bowlt, John E. (2008). Moscow and St. Petersburg 1900–1920: Art, Life and Culture. New York: The Vendome Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-86565-191-3.

- "Agni Yoga". highest-yoga.info. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018.

- The Stage, 22 January, 1920.

- Andreyev, Alexandre (2003). Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debacle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s. Brill. p. 294. ISBN 9004129529.

- Andreyev, Alexandre (May 8, 2014). The Myth of the Masters Revived: The Occult Lives of Nikolai and Elena Roerich. BRILL. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-90-04-27043-5.

- Znamenski, Andrei (July 1, 2011). Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia. Quest Books. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-8356-0891-6.

- "Observer review: Tournament of Shadows by Karl Meyer and Shareen Brysac". The Guardian. January 7, 2001.

- McCannon, John (2022). Nicholas Roerich: The Artist Who Would Be King. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0822947417.

- Andreyev, Alexandre (2003). Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debacle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s. Brill. p. 295. ISBN 9004129529.

- AVPRF, op. 04, op. 13, papka 87, d. 50117, 1. 13a. Krestinsky to Checherin, January 2, 1925

- "Andrei Znamenski, "Nicholas Roerich Shambhala Warrior"". YouTube. May 29, 2011..

- Keyhoe, Donald (June 30, 2006). The Flying Saucers Are Real. ISBN 9781585092642.

- "The Colorado Engineer". 1954.

- "Roerich Nominated for Peace Award". New York Times. March 3, 1929. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- "Nomination Database - Peace". Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Boyd, James (January 2012). "In Search of Shambhala? Nicholas Roerich's 1934–5 Inner Mongolian Expedition". Inner Asia. 14 (2). Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers: 257–277. doi:10.1163/22105018-90000004. ISSN 2210-5018. JSTOR 24572064.

- Peter Leek (2005). Russian Painting. Parkstone International. pp. 256–. ISBN 978-1-78042-975-5. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- N. Roerich. Diary Leaves. V. 3. – Moscow, International Centre of the Roerichs. – 1996. – p.39. ISBN 5-86988-056-4