| Revision as of 11:33, 22 November 2012 edit65.35.164.231 (talk) →Her early years← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:37, 20 January 2025 edit undoHydrangeans (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,621 edits →Around the world and general impact: Added sentence about what day Bly finished her circumnavigation and added citation. →Film and television: Trimmed some uncited material and two examples that were original research cited to the pop cultural primary sources. →Sources: Added sourceTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|American investigative journalist (1864–1922)}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| {{For|the fictional character|Frankie and Johnny (song){{!}}"Frankie and Johnny"}} | |||

| | name = Nellie Bly | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=January 2021}} | |||

| | image = Nellie_Bly_2.jpg | |||

| {{Infobox writer | |||

| | caption = Elizabeth Cochrane, aka Nellie Bly c. 1890 | |||

| | name = Nellie Bly | |||

| | birth_name = Elizabeth Jane Cochran | |||

| | image = Nellie Bly 2.jpg | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1864|05|05}} | |||

| | caption = Cochran at 26 years old, {{circa|1890}} | |||

| | birth_place = ] | |||

| | pseudonym = Elly Cochran, Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, and most commonly known as Nellie Bly as her pen-name | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1922|01|27|1864|05|05}} | |||

| | birth_name = Elizabeth Jane Cochran | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1864|05|05}} | |||

| | nationality = American | |||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | occupation = Journalist, Novelist, Inventor | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1922|01|27|1864|05|05}} | |||

| | spouse = ] (m. 1895) | |||

| | |

| death_place = ], U.S. | ||

| | occupation = {{flatlist| | |||

| | signature = Nellie Bly signature.svg | |||

| * ] | |||

| | signature_alt = Signature reads: "Nellie Bly" | |||

| * writer | |||

| | footnotes = <small>After her marriage, Nellie used the name "Elisabeth Cochrane Seaman," as seen in the signatures on patents she filed.</small> | |||

| * inventor | |||

| }} | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|]|1895|1904|end=died}} | |||

| | awards = ] (1998) | |||

| | notable_works = | |||

| | language = English | |||

| | signature = Nellie Bly signature.svg | |||

| | signature_alt = Signature reads: "Nellie Bly" | |||

| | footnotes = After her marriage, Bly used the name "Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman." | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Nellie Bly''' (May 5, 1864<ref>Kroeger 1994 reports (p. 529) that although a birth year of 1867 was deduced from the age Bly claimed to be at the height of her popularity, her baptismal record confirms 1864.</ref> – January 27, 1922) was the ] of American ] '''Elizabeth Jane Cochrane'''. She remains notable for two feats: a record-breaking ] in emulation of ]'s character Phileas Fogg, and an ] in which she ] to study a mental institution from within. In addition to her writing, she was also an industrialist and charity worker. She originally intended for her pseudonym to be "Nelly Bly," but her editor wrote "Nellie" by mistake, and the error stuck. | |||

| '''Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman''' (born '''Elizabeth Jane Cochran'''; May 5, 1864 – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name '''Nellie Bly''', was an American journalist who was widely known for her record-breaking ] in 72 days in emulation of ]'s fictional character ] and an ] in which she worked undercover to report on a mental institution from within.<ref name="doodle">{{Cite news |last=Bernard |first=Diane |date=July 28, 2019 |title=She went undercover to expose an insane asylum's horrors. Now Nellie Bly is getting her due. |newspaper=The Washington Post |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/07/28/she-went-undercover-expose-an-insane-asylums-horrors-now-nellie-bly-is-getting-her-due/ }}</ref> She pioneered her field and launched a new kind of ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/world/peopleevents/pande01.html |title=American Experience |publisher=] |access-date=September 6, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170305011608/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/world/peopleevents/pande01.html |archive-date=March 5, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Her early years== | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| Nellie was born '''Elizabeth Jane Cochran''' in Cochran Mills, ]. | |||

| Elizabeth Jane Cochran was born May 5, 1864,{{sfn|Kroeger|1994|pp=3 & 5}} in "Cochran's Mills", now part of ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.pittsburghclo.org/files/file/NellieBlyStudentsGuide_v4%5B1%5D.pdf |title=Nellie Bly |publisher=Pittsburgh Civic Light Opera |access-date=July 20, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131101091249/https://www.pittsburghclo.org/files/file/NellieBlyStudentsGuide_v4%5B1%5D.pdf#91;1].pdf |archive-date=November 1, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-3C0 |title=Nellie Bly Historical Marker |website=Explore PA History |publisher=] |access-date=July 20, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160415215106/http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-3C0 |archive-date=April 15, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://pghbridges.com/glassport/0587-4460/cochransmillrd_lickrun.htm |title=Cochran's Mill Rd over Licks Run |last=Cridlebaugh |first=Bruce S. |publisher=Bridges and Tunnels of Allegheny County and Pittsburgh, PA |access-date=July 20, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170828104706/http://pghbridges.com/glassport/0587-4460/cochransmillrd_lickrun.htm |archive-date=August 28, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> Her father, Michael Cochran, born about 1810, started as a laborer and mill worker before buying the local mill and most of the land surrounding his family farmhouse. He later became a merchant, postmaster, and associate justice at Cochran's Mills (named after him) in Pennsylvania. Michael married twice. He had 10 children with his first wife, Catherine Murphy, and five more children, including Elizabeth Cochran, his thirteenth daughter, with his second wife, Mary Jane Kennedy.{{sfn|Kroeger|1994|p=3}} Michael Cochran died in 1870, when Elizabeth was 6.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.biography.com/activist/nellie-bly |title=Nellie Bly Biography |website=Biography.com |publisher=A&E Television Networks |access-date=Jan 27, 2021 }}</ref> | |||

| Her father, Michael Cochran, was a modest laborer and mill worker who married Mary Jane. Cochran taught his young children a cogent lesson about the virtues of hard work and determination, buying the local mill and most of the land surrounding his family farmhouse. As a young girl Bly was often called "Pinky" because she so frequently wore the color. As she became a teenager she wanted to portray herself as more sophisticated, and so dropped the nickname and changed her surname to '''Cochrane'''.<ref>Kroeger 1994, p. 25.</ref> She attended ] for one term, but was forced to drop out due to lack of funds. | |||

| As a young girl, Elizabeth often was called "Pink" because she so frequently wore that color. As she became a teenager, she wanted to portray herself as more sophisticated, and she dropped the nickname and changed her surname to "Cochrane".{{sfn|Kroeger|1994|p=25}} In 1879, she enrolled at Indiana Normal School (now ]) for one term but was forced to drop out due to lack of funds.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Englert|first1=John|last2=Houser|first2=Regan|year=1994|title=The New American Girl|url=http://www.archive.org/stream/iupmagazine124indi#page/4/mode/2up|journal=IUP Magazine|publisher=Indiana University of Pennsylvania|volume=12|issue=4|pages=4–7|access-date=April 8, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100501220500/http://www.archive.org/stream/iupmagazine124indi#page/4/mode/2up|archive-date=May 1, 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1880, Cochrane's mother moved her family to ], which was later annexed by the ].<ref name="NBO" /> | |||

| In 1880, Bly and her family moved to ]. An aggressively misogynistic column in the '']'' prompted her to write a fiery rebuttal to the editor with the pen name "Lonely Orphan Girl." The editor was so impressed with Bly's earnestness and spirit that he asked the man who wrote the letter to join the paper. When he learned the man was Bly, he refused to give her the job, but she was a good talker and persuaded him. Female newspaper writers at that time customarily used pen names, and for Bly the editor chose "Nellie Bly", adopted from the ] in the popular song "Nelly Bly" by ]. | |||

| ==Career== | |||

| As a writer, Bly focused her early work for the ''Dispatch'' on the plight of working women, writing a series of investigative articles on female factory workers. But editorial pressure pushed her to the so-called ] to cover fashion, society, and gardening, the usual role for female journalists of the day. Dissatisfied with these duties, she took the initiative and traveled to Mexico to serve as a ]. Still only 21, she spent nearly half a year reporting the lives and customs of the ]; her dispatches were later published in book form as '']''. In one report, she protested the imprisonment of a local journalist for criticizing the Mexican government, then a dictatorship under ]. When Mexican authorities learned of Bly's report, they threatened her with arrest, prompting her to leave the country. Safely home, she denounced Díaz as a tyrannical czar suppressing the Mexican people and ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ===''Pittsburgh Dispatch''=== | |||

| ==Asylum exposé== | |||

| In 1885, a column in the '']'' titled "What Girls Are Good For" stated that girls were principally for birthing children and keeping house. This prompted Elizabeth to write a response under the pseudonym "Lonely Orphan Girl".<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.nwhm.org/online-exhibits/youngandbrave/bly.html |title=Young and Brave: Girls Changing History |publisher=National Woman's History Museum |access-date=April 7, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906093341/https://www.nwhm.org/online-exhibits/youngandbrave/bly.html |archive-date=September 6, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="NBO">{{Cite web|title=Nellie Bly, (1864–1922)|url=http://www.nellieblyonline.com/bio|last=Fritz|first=Arthur|website=Nellie Bly Online|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160323195842/http://www.nellieblyonline.com/bio|archive-date=March 23, 2016|access-date=April 7, 2014}}</ref><ref name="About.com">{{Cite web |url=http://womenshistory.about.com/od/blynellie/p/Nellie-Bly.htm |title=Nellie Bly |last=Jone Johnson Lewis |publisher=] |access-date=April 7, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170211034026/http://womenshistory.about.com/od/blynellie/p/Nellie-Bly.htm |archive-date=February 11, 2017 |url-status=dead }}</ref> The editor, George Madden, was impressed with her passion and ran an advertisement asking the author to identify herself. When Cochran introduced herself to the editor, he offered her the opportunity to write a piece for the newspaper, again under the pseudonym "Lonely Orphan Girl".<ref name="About.com" /> Her first article for the ''Dispatch'', titled "The Girl Puzzle", argued that not all women would marry and that what was needed were better jobs for women.<ref name=todd>{{Cite book |last=Todd |first=Kim |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1244546167 |title=Sensational : the hidden history of America's "girl stunt reporters" |date=2021 |isbn=978-0062843616 |edition= |publisher=Harper |location=New York|oclc=1244546167 |author-link=Kim Todd | page=17}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Ten Days in a Mad-House}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Burdened again with theater and arts reporting, Bly left the ''Pittsburgh Dispatch'' in 1887 for ]. Penniless after four months, she talked her way into the offices of ]'s newspaper, the '']'', and took an ] for which she agreed to feign insanity to investigate reports of brutality and neglect at the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island. | |||

| Her second article, "Mad Marriages", was about how ] affected women. In it, she argued for reform of divorce laws.<ref name="Spartacus" />{{failed verification|date=October 2023}} "Mad Marriages" was published under the byline of Nellie Bly, rather than "Lonely Orphan Girl" because, at the time,{{r|todd}} it was customary for female journalists to use pen names to conceal their gender so that readers would not discredit them. The editor chose "Nellie Bly", after the African-American title character in the popular song "Nelly Bly" by ].<ref name="Room2010">{{Cite book |title=Dictionary of Pseudonyms: 13,000 Assumed Names and Their Origins|edition=5th |last=Adrian Room |publisher=McFarland |year=2010 |isbn=978-0786457632 |page=182}}</ref> Cochrane originally intended that her pseudonym be "Nelly Bly", but her editor wrote "Nellie" by mistake, and the error stuck.{{sfn|Kroeger|1994|pp=43–44}} Madden was impressed again and offered her a full-time job.<ref name="NBO" /> | |||

| After a night of practicing deranged expressions in front of a mirror, she checked into a working-class ]. She refused to go to bed, telling the boarders that she was afraid of them and that they looked crazy. They soon decided that ''she'' was crazy, and the next morning summoned the police. Taken to a courtroom, she pretended to have ]. The judge concluded she had been drugged. | |||

| As a writer, Nellie Bly focused her early work for the ''Pittsburgh Dispatch'' on the lives of working women, writing a series of investigative articles on female factory workers. However, the newspaper soon received complaints from factory owners about her writing, and she was reassigned to ]s to cover fashion, society, and gardening, the usual role for female journalists, and she became dissatisfied. Still only 21, she was determined "to do something no girl has done before."<ref name="Nellie on the Fly">{{Cite web |url=https://www.theattic.space/home-page-blogs/2019/1/26/around-the-world-with-nellie-bly |title=Nellie on the Fly |website=The Attic |date=January 26, 2019 |access-date=February 1, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190423034603/https://www.theattic.space/home-page-blogs/2019/1/26/around-the-world-with-nellie-bly |archive-date=April 23, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> She then traveled to Mexico to serve as a ], spending nearly half a year reporting on the lives and customs of the ]. Her dispatches later were published in book form as ''].''<ref name="Spartacus">{{Cite web |url=http://spartacus-educational.com/USAWbly.htm |title=Nellie Bly |last=Simkin |first=John |date=September 1997 |publisher=] |access-date=January 24, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190403142341/https://spartacus-educational.com/USAWbly.htm |archive-date=April 3, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> In one report, she protested the imprisonment of a local journalist for criticizing the Mexican government, then a dictatorship under ].<ref>{{cite wikisource |title=Six Months in Mexico |wslink=Six Months In Mexico/Chapter 26 |first=Nellie |last=Bly |year=1889 |publisher=American Publishers Corporation |location=New York |chapter=Chapter XXVI}}</ref> When Mexican authorities learned of Bly's report, they threatened her with arrest, prompting her to flee the country. Safely home, she accused Díaz of being a tyrannical czar suppressing the Mexican people and ].<ref name="NBO" /> | |||

| She was then examined by several doctors, who all declared her to be insane. "Positively demented," said one, "I consider it a hopeless case. She needs to be put where someone will take care of her."<ref name=Bly1887>Bly 1887.</ref> The head of the insane pavilion at ] pronounced her "undoubtedly insane". The case of the "pretty crazy girl" attracted media attention: "Who Is This Insane Girl?" asked the '']''. '']'' wrote of the "mysterious waif" with the "wild, hunted look in her eyes", and her desperate cry: "I can't remember I can't remember."<ref>Kroeger 1994, pp. 91–92.</ref> | |||

| ===Asylum exposé=== | |||

| Committed to the asylum, Bly experienced its conditions firsthand. The food consisted of gruel broth, spoiled beef, bread that was little more than dried dough, and dirty undrinkable water. The dangerous patients were tied together with ropes. The patients were made to sit for much of each day on hard benches with scant protection from the cold. Waste was all around the eating places. Rats crawled all around the hospital. The bathwater was frigid, and buckets of it were poured over their heads. The nurses were obnoxious and abusive, telling the patients to shut up, and beating them if they did not. Speaking with her fellow patients, Bly was convinced that some were as sane as she was. On the effect of her experiences, she wrote: | |||

| {{Main|Ten Days in a Mad-House}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Burdened again with theater and arts reporting, Bly left the ''Pittsburgh Dispatch'' in 1887 for New York City. Bly faced rejection after rejection as news editors would not consider hiring a woman.<ref name="Lutes 2002">{{Cite journal|last=Lutes|first=Jean Marie|date=2002|title=Into the Madhouse with Nellie Bly: Girl Stunt Reporting in Late Nineteenth-Century America|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/aq.2002.0017|journal=American Quarterly|volume=54|issue=2|pages=217–253|doi=10.1353/aq.2002.0017|s2cid=143667078|issn=1080-6490}}</ref> Penniless after four months, she talked her way into the offices of ]'s newspaper, the '']'', and took an ] for which she agreed to feign ] to investigate reports of ] and ] at the ] on Blackwell's Island, now named ].<ref>{{Cite magazine |url=http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/nellie-blys-lessons-in-writing-what-you-want-to |title=Nellie Bly's Lessons in Writing What You Want To |last=Gregory |first=Alice |date=May 14, 2014 |magazine=] |access-date=August 23, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190719084012/https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/nellie-blys-lessons-in-writing-what-you-want-to |archive-date=July 19, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment? Here is a class of women sent to be cured. I would like the expert physicians who are condemning me for my action, which has proven their ability, to take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 a.m. until 8 p.m. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her no reading and let her know nothing of the world or its doings, give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck.<ref name=Bly1887/></blockquote> | |||

| It was not easy for Bly to be admitted to the asylum: she first decided to check herself into a boarding house called "Temporary Homes for Females". She stayed up all night to give herself the wide-eyed look of a disturbed woman and began making accusations that the other boarders were insane. Bly told the assistant matron: "There are so many crazy people about, and one can never tell what they will do."<ref name="Ten Days in a Mad-House">{{Cite book |url=http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/bly/madhouse/madhouse.html |title=Ten Days in a Mad-House |last=Bly |first=Nellie |date=1887 |via=digital.library.upenn.edu |publisher=Ian L. Munro|location=New York |access-date=October 13, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040216024852/http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/bly/madhouse/madhouse.html |archive-date=February 16, 2004 |url-status=dead }}</ref> She refused to go to bed and eventually scared so many of the other boarders that the police were called to take her to the nearby courthouse. Once examined by a police officer, a judge, and a doctor, Bly was taken to ] for a few days, then after evaluation was sent by boat to Blackwell's Island.<ref name="Ten Days in a Mad-House" /> | |||

| <blockquote>…My teeth chattered and my limbs were …numb with cold. Suddenly, I got three buckets of ice-cold water…one in my eyes, nose and mouth.</blockquote> | |||

| Committed to the asylum, Bly experienced the deplorable conditions firsthand. After ten days, the asylum released Bly at ''The World''{{'}}s behest. Her report, published October 9, 1887<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bell |first=Jo |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1250378425 |title=On this day she : putting women back into history, one day at a time |date=2021 |others=Tania Hershman, Ailsa Holland |isbn=978-1789462715 |location=London |page=313 |oclc=1250378425}}</ref> and later in book form as '']'', caused a sensation, prompted the asylum to implement reforms, and brought her lasting fame.<ref name="ten">{{Cite web|title=Ten Days in a Madhouse: The Woman Who Got Herself Committed|url=http://mentalfloss.com/article/29734/ten-days-madhouse-woman-who-got-herself-committed|last=DeMain|first=Bill|publisher=mental floss|access-date=May 10, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190514211407/http://mentalfloss.com/article/29734/ten-days-madhouse-woman-who-got-herself-committed|archive-date=May 14, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> Nellie Bly had a significant impact on American culture and shed light on the experiences of marginalized women beyond the bounds of the asylum as she ushered in the era of ] journalism.<ref name="Lutes 2002" /> | |||

| After ten days, Bly was released from the asylum at ''The World'''s behest. Her report, later published in book form as '']'', caused a sensation and brought her lasting fame. While embarrassed physicians and staff fumbled to explain how so many professionals had been fooled, a ] launched its own investigation into conditions at the asylum, inviting Bly to assist. The jury's report recommended the changes she had proposed, and its call for increased funds for care of the insane prompted an $850,000 increase in the budget of the Department of Public Charities and Corrections. They also made sure that future examinations were more thorough so that only the seriously ill actually went to the asylum. | |||

| In 1893, Bly used the celebrity status she had gained from her asylum reporting skills to schedule an exclusive interview with the allegedly insane serial killer ].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Telfer|first=Tori|title=Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout History|publisher=HarperCollins Publishers|year=2017|location=New York|pages=69}}</ref> | |||

| ==Around the world== | |||

| ] that mentions Bly's connection to the island]] | |||

| Biographer ] argues: | |||

| :Her two-part series in October 1887 was a sensation, effectively launching the decade of "stunt" or "detective" reporting, a clear precursor to investigative journalism and one of Joseph Pulitzer's innovations that helped give "New Journalism" of the 1880s and 1890s its moniker. The employment of "stunt girls" has often been dismissed as a circulation-boosting gimmick of the sensationalist press. However, the genre also provided women with their first collective opportunity to demonstrate that, as a class, they had the skills necessary for the highest level of general reporting. The stunt girls, with Bly as their prototype, were the first women to enter the journalistic mainstream in the twentieth century.{{sfn|Kroeger|2000}} | |||

| ===Around the world and general impact=== | |||

| {{Main|Around the World in Seventy-Two Days}} | {{Main|Around the World in Seventy-Two Days}} | ||

| ]'' newspaper to promote Bly's ] |

]'' newspaper to promote Bly's ]]] | ||

| In 1888, Bly suggested to her editor at the ''New York World'' that she take a trip around the world, attempting to turn the fictional '']'' into fact for the first time. A year later, at 9:40 a.m. on November 14, 1889, and with two days' notice,<ref name="Ruddick, Nicholas 1999, p. 4">Ruddick, Nicholas. “Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age.” ''Canadian Review of American Studies'', Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 4</ref> she boarded the ], a steamer of the ],<ref name="Kroeger, Brooke 1994, p. 146">Kroeger, Brooke. ''Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist''. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 146</ref> and began her 24,899-mile journey. | |||

| In 1888, Bly suggested to her editor at the ''New York World'' that she take a trip around the world, attempting to turn the fictional '']'' (1873) into fact for the first time. A year later, at 9:40 a.m. on November 14, 1889, and with two days' notice,{{sfn|Ruddick|1999|p=4}}{{Clarify|date=January 2023|reason=Is it a year or two days later?}} she boarded the '']'', a steamer of the ],{{sfn|Kroeger|1994|p=146}} and began her 24,898 mile (40,070 kilometer) journey. | |||

| She brought with her the dress she was wearing, a sturdy overcoat, several changes of underwear and a small travel bag carrying her toiletry essentials. | |||

| She carried most of her money (£200 in English bank notes and gold in total as well as some American currency)<ref>Kroeger, Brooke. ''Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist''. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 141</ref> in a bag tied around her neck.<ref name="Ruddick, Nicholas 1999, p. 5">Ruddick, Nicholas. “Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age.” ''Canadian Review of American Studies'', Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 5</ref> | |||

| To sustain interest in the story, the ''World'' organized a "Nellie Bly Guessing Match" in which readers were asked to estimate Bly's arrival time to the second, with the Grand Prize consisting at first of a trip to Europe and, later on, spending money for the trip.{{sfn|Ruddick|1999|p=5}}{{sfn|Kroeger|1994|p=150}} During her travels around the world, Bly went through England, France (where she met ] in ]), ], the ], ] (in ]), the ] of ] and Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan. | |||

| ] printed in '']'' on |

] printed in '']'' on February 8, 1890]] | ||

| Just over seventy-two days after her initial departure, Bly arrived in New York on January 25, 1890, completing her circumnavigation of the globe.{{Sfn|Linford|2022|pp=72–77}} She had traveled alone for almost the entire journey.{{sfn|Kroeger|1994|p=146}} Bly's journey was a ], though it only stood for a few months, until ] completed the journey in 67 days.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/george-francis-train-one-of-few-sane-men-mad-mad-world/ |title=George Francis Train, One of the Few Sane Men in a Mad, Mad World |website=New England Historical Society|date=March 2015 }}</ref> | |||

| On her travels around the world, Bly went through England, France (where she met ] in ]), ], the ], ] (]), the Straits Settlements of ] and ], ], and ]. The development of efficient submarine cable networks and the electric telegraph allowed Bly to send short progress reports,<ref name="Ruddick, Nicholas 1999, p. 8">Ruddick, Nicholas. “Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age.” ''Canadian Review of American Studies'', Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 8</ref> though longer dispatches had to travel by regular post and were thus often delayed by several weeks.<ref name="Kroeger, Brooke 1994, p. 150"/> | |||

| ===Novelist=== | |||

| Bly travelled using steamships and the existing railroad systems,<ref>Ruddick, Nicholas. “Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age.” ''Canadian Review of American Studies'', Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 6</ref> which caused occasional setbacks, particularly on the Asian leg of her race.<ref name="ReferenceA">Bear, David. “Around the World With Nellie Bly.” ''Pittsburgh Post-Gazette'', November 26, 2006</ref> During these stops, she visited a leper colony in China<ref name="Ruddick, Nicholas 1999, p. 7">Ruddick, Nicholas. “Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age.” ''Canadian Review of American Studies'', Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 7</ref><ref>Kroeger, Brooke. ''Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist''. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 160</ref> and she bought a monkey in Singapore.<ref name="Ruddick, Nicholas 1999, p. 7"/><ref>Kroeger, Brooke. ''Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist''. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 158</ref> | |||

| After the fanfare of her trip around the world, Bly quit reporting and took a lucrative job writing serial novels for publisher ]'s weekly ''New York Family Story Paper.'' The first chapters of ''Eva The Adventuress,'' based on the real-life trial of Eva Hamilton, appeared in print before Bly returned to New York. Between 1889 and 1895 she wrote eleven novels. As few copies of the paper survived, these novels were thought lost until 2021, when author ] announced the discovery of 11 lost novels in Munro's British weekly ''The London Story Paper.''<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/almost-100-years-after-her-death-nellie-bly-is-back/Content?oid=86169777 |author=Reid, Kerry|title=Almost 100 Years After Her Death, Nellie Bly Is Back|publisher=Chicago Reader|date=February 2, 2021 }}</ref> In 1893, though still writing novels, she returned to reporting for the ''World''. | |||

| ===Later work=== | |||

| As a result of rough weather on her Pacific crossing, she arrived in San Francisco on the ] ship '']'' on January 21, two days behind schedule.<ref name="ReferenceA"/><ref>*</ref> However, ''World'' owner Pulitzer ] to bring her home, and she arrived back in New Jersey on January 25, 1890, at 3:51 p.m.<ref name="Ruddick, Nicholas 1999, p. 8"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1895, Bly married millionaire manufacturer ].<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|title=Nellie Bly {{!}} American journalist|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nellie-Bly|language=en|access-date=August 23, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170823170657/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nellie-Bly|archive-date=August 23, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> Bly was 31 and Seaman was 73 when they married.<ref name="NYT">{{Cite news|date=January 28, 1922|title=Nellie Bly, journalist, Dies of Pneumonia|url=https://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0505.html|url-status=live|work=The New York Times|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111115224129/http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0505.html|archive-date=November 15, 2011|access-date=November 29, 2011}}</ref> Due to her husband's failing health, she left journalism and succeeded her husband as head of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co., which made steel containers such as milk cans and boilers. Seaman died in 1904.<ref name="AmericanOilGas">{{Cite web|title=The Remarkable Nellie Bly|url=http://aoghs.org/technology/the-remarkable-nellie-bly/|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111004215247/http://aoghs.org/technology/the-remarkable-nellie-bly/|archive-date=October 4, 2011|access-date=July 20, 2013|publisher=American Oil & Gas Historical Society}}</ref> | |||

| "Seventy-two days, six hours, eleven minutes and fourteen seconds after her ] departure" Bly was back in New York. She had circumnavigated the globe almost<ref name="Kroeger, Brooke 1994, p. 146"/> unchaperoned. At the time, Bisland was still going around the world. Like Bly, she had missed a connection and had to board a slow, old ship (the ''Bothina'') in the place of a fast ship (''Etruria'').<ref name="Ruddick, Nicholas 1999, p. 4"/> Bly's journey was a world record, though it was bettered a few months later by ], who completed the journey in 67 days.<ref>http://www.skagitriverjournal.com/WA/Library/Newspaper/Visscher/Visscher3-Bio2.html para 16</ref> By 1913, Andre Jaeger-Schmidt, Henry Frederick and ] had improved on the record, the latter completing the journey in less than 36 days.<ref>''New York Times'', "A Run Around the World", August 8, 1913</ref> | |||

| That same year, Iron Clad began manufacturing the steel barrel that was the model for the 55-gallon ] still in widespread use in the United States. There have been claims that Bly invented the barrel,<ref name=AmericanOilGas/> but the inventor was registered as Henry Wehrhahn (U.S. Patents 808,327 and 808,413).<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.businesshistory.com/ind._oil2.php |title=Industries – Business History of Oil Drillers, Refiners |publisher=Business History |access-date=July 20, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131006045411/http://www.businesshistory.com/ind._oil2.php |archive-date=October 6, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Later years== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1895 Nellie Bly married millionaire manufacturer ], who was 40 years her senior. She retired from journalism, and became the president of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co., which made steel containers such as milk cans and boilers. In 1904, her husband died. In the same year, Iron Clad began manufacturing the steel barrel that was the model for the 55-gallon ] still in widespread use in the United States. Although there have been claims that Nellie Bly invented the barrel,<ref>http://aoghs.org/technology/the-remarkable-nellie-bly/</ref> the inventor is believed to have been Henry Wehrhahn, who likely assigned his invention to her. (US Patents 808,327 and 808,413).<ref>http://www.businesshistory.com/ind._oil2.php</ref> Nellie Bly was, however, an inventor in her own right, receiving US patent 697,553 for a novel milk can and US patent 703,711 for a stacking garbage can, both under her married name of Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman.<ref>http://www.google.com/patents</ref> For a time she was one of the leading female industrialists in the United States, but embezzlement by employees forced her into bankruptcy. Forced back into reporting, she covered such events as the ] convention in 1913, and stories on Europe's ] during ].<ref>''The remarkable Nellie Bly, inventor of the metal oil drum'', Petroleum Age, 12/2006, p.5.</ref> | |||

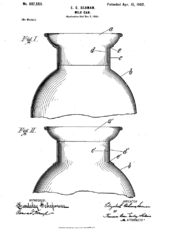

| Bly was also an inventor in her own right, receiving {{US patent|697553}} for a novel milk can and {{US patent|703711}} for a stacking garbage can, both under her married name of Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman. For a time, she was one of the leading women industrialists in the United States. But her negligence, and embezzlement by a factory manager, resulted in the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co. going bankrupt.<ref name="LAT">{{Cite news |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-03-28-vw-39454-story.html |title=Nellie Bly, Girl Reporter : Daredevil journalist |last=Garrison |first=Jayne |work=] |access-date=May 5, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150508180815/http://articles.latimes.com/1994-03-28/news/vw-39454_1_real-nellie-bly/2 |archive-date=May 8, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ]]]In 1916 Nellie was given a baby boy whose mother requested Nellie look after him and see that he become adopted. The child was illegitimate and difficult to place since he was ]. He spent the next six years in an orphanage run by the Church For All Nations {{Clarify|date=November 2008}} in Manhattan. | |||

| According to biographer Brooke Kroeger: | |||

| As Nellie became ill towards the end of her life she requested that her niece, Beatrice Brown, look after the boy and several other babies in whom she had become interested. Her interest in orphanages may have been part of her ongoing efforts to improve the social organizations of the day. | |||

| {{blockquote|She ran her company as a model of social welfare, replete with health benefits and recreational facilities. But Bly was hopeless at understanding the financial aspects of her business and ultimately lost everything. Unscrupulous employees bilked the firm of hundreds of thousands of dollars, troubles compounded by protracted and costly bankruptcy litigation.{{sfn|Kroeger|2000}}}} | |||

| She died of ] at St. Mark's Hospital in New York City in 1922, at age 57.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1= |first1= |authorlink= |date=28 January 1922 |title=Nellie Bly, Journalist, Dies of Pneumonia |journal=The New York Times |publisher=The New York Times Co. |url=http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0505.html |accessdate=29 November 2011 }}</ref> She was interred in a modest grave at ] in ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dunning |first1=Jennifer |authorlink=Jennifer Dunning |date=23 February 1979 |title=Woodlawn, Bronx's Other Hall of Fame |journal=The New York Times |publisher=The New York Times Co. |url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70911F63D5D12728DDDAA0A94DA405B898BF1D3 |accessdate=29 November 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| Back in reporting, she covered the ] of 1913 for the ]. Her article's headline was "Suffragists Are Men's Superiors" and in its text she accurately predicted that women in the United States would be given the right to vote in 1920.<ref name="Harvey">{{Cite web |url=http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/aw01e/aw01e.html#ack |title=Marching for the Vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913 |last=Harvey |first=Sheridan |year=2001 |website=American Women |publisher=Library of Congress |access-date=March 3, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130210230748/http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/aw01e/aw01e.html#ack |archive-date=February 10, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Bly wrote stories on Europe's ] during ].<ref>{{cite magazine |title=The remarkable Nellie Bly, inventor of the metal oil drum |magazine=Petroleum Age |date=December 2006 |page=5}}</ref> Bly was the first woman and one of the first foreigners to visit the war zone between Serbia and Austria. She was arrested when she was mistaken for a British spy.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Bly|first=Nellie|date=January 12, 1915|title=American Woman Imprisoned in Austria; Liberated When Identified by Dr. Friedman|page=2|work=Los Angeles Herald|url=https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH19150112.2.23&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------1|access-date=May 13, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ==Death== | |||

| ] | |||

| On January 27, 1922, Bly died of pneumonia at St. Mark's Hospital, New York City, aged 57.{{sfn|Kroeger|2000}} She was interred at ] in ], New York City.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1979/02/23/archives/woodlawn-bronxs-other-hall-of-fame-hitching-posts-available.html |title=Woodlawn, Bronx's Other Hall of Fame |last=Dunning |first=Jennifer |date=February 23, 1979 |work=The New York Times |access-date=November 29, 2011 |author-link=Jennifer Dunning |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180110234051/http://www.nytimes.com/1979/02/23/archives/woodlawn-bronxs-other-hall-of-fame-hitching-posts-available.html |archive-date=January 10, 2018 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| ===Dramatic representations=== | |||

| *Bly was the subject of a 1946 ] by ] and ].<ref> MacGregor retired.", ''musicals101.com''</ref> | |||

| *In 1981 ] appeared as Bly in a made for TV movie called ''The Adventures of Nellie Bly''.<ref></ref> | |||

| *] appeared as Nellie Bly in the July 10, 1983 ] episode "Jack's Back" | |||

| *A fictionalized account of her around the world trip was used in the comic book "Julie Walker is The Phantom" published by Moonstone Books (Story: Elizabeth Massie, art: Paul Daly, colors: Stephen Downer).<ref></ref> | |||

| * ] used her as a model for the type of reporter he wanted ] to be. | |||

| * In ] by ] the yachtsman (sometimes a slang term for a bootlegger) Dan Cody, who takes the young Jay Gatsby under his wing was said by Fitzgerald to be based on "the mysterious yatchsman (sic) whose mistress was Nellie Bly". (Some Kind of Epic Grandeur, biography of F Scott Fitzgerald by Matthew J Bruccoli) | |||

| === |

===Honors=== | ||

| In 1998, Bly was inducted into the ].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Elizabeth Jane Cochran – National Women's Hall of Fame| url= http://www.greatwomen.org/component/fabrik/details/2/22|url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130924181010/http://www.greatwomen.org/component/fabrik/details/2/22|archive-date=September 24, 2013|access-date=July 20, 2013|publisher=Greatwomen.org}}</ref> | |||

| *The Nellie Bly Amusement Park in Brooklyn, New York City, is named after her, taking as its theme ''Around the World in Eighty Days''. The park recently reopened under new management, renamed "Adventurers Amusement Park." | |||

| *From early in the twentieth century until 1961, the ] operated a parlor-car only ] between New York and ] that bore the name, ''Nellie Bly''. | |||

| *] confers an annual "Nellie Bly Cub Reporter" to acknowledge the best journalistic effort by an individual with three years or less professional experience. | |||

| Bly was one of four journalists honored with a US postage stamp in a "Women in Journalism" set in 2002.<ref>{{cite press release | website= about.com| publisher=USPS | date= September 14, 2002| url= http://womenshistory.about.com/library/news/pr/blpr_stamp_journalists.htm| title= Four Accomplished Journalists Honored on U.S. Postage Stamps |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111016141356/http://womenshistory.about.com/library/news/pr/blpr_stamp_journalists.htm| archive-date=October 16, 2011}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Fletcher, Bertram Julian|title=Nellie Bly Marguerite Higgins Ethel L. Payne Ida M. Tarbell March Women's History Month Lady Journalists on Postage Stamps |url= http://slideplayer.com/slide/9446515/|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180209122243/http://slideplayer.com/slide/9446515/|archive-date=February 9, 2018|access-date=February 9, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| ===Other recognition=== | |||

| *In 1998, she was inducted into the ].<ref></ref> | |||

| In 2019, the ] put out an open call for artists to create a Nellie Bly Memorial art installation on ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Nellie Bly Memorial Call for Artists |url=https://rioc.ny.gov/DocumentCenter/View/2371/Nellie-Bly-Memorial-Call-for-Artsts?bidId= |website=Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation of New York |publisher=New York State |access-date=2 March 2021}}</ref> The winning proposal, '']'' by ], was announced on October 16, 2019.<ref>{{cite web |title=Amanda Matthews of Prometheus Art Selected to Create Monument to Journalist Nelly Bly on Roosevelt Island, Press Release |url=http://rioc.ny.gov/DocumentCenter/View/2902/Amanda-Matthews-of-Prometheus-Art-Selected-to-Create-Nellie-Bly-Monument---10-16-19 |website=Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation of New York |publisher=New York State |access-date=2 March 2021}}</ref> ''The Girl Puzzle'' opened to the public in December, 2021.<ref>{{cite web | title=Monument honoring journalist Nellie Bly opens: "This installation is spiritual" | website=CBS News | date=December 11, 2021 | url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/nellie-bly-monument-opens/ | access-date=March 24, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| *Nellie Bly was one of four journalists honored with a U.S ] in a "Women in Journalism" set in 2002.<ref>USPS Press Release (September 14, 2002), , ''usps.com''</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| *Her investigation of the Blackwell's Island insane asylum is dramatized in a ] in the Annenberg Theater at the ] in ]. | |||

| The ] confers an annual Nellie Bly Cub Reporter ] to acknowledge the best journalistic effort by an individual with three years or fewer of professional experience. In 2020, it was awarded to Claudia Irizarry Aponte, of ''THE CITY.''<ref>{{Cite web|title=New York Press Club Announces its 2020 Journalism Award Winners|url=https://www.nypressclub.org/new-york-press-club-announces-its-2020-journalism-award-winners/|access-date=2021-11-05|website=www.nypressclub.org|date=August 19, 2020 }}</ref> | |||

| *Bly served as inspiration for the character, Katherine Plumber from the musical adaptation of Disney's '']''. | |||

| ===Theater=== | |||

| Bly was the subject of the 1946 ] ''Nellie Bly'' by ] and ]. The show ran for 16 performances.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Dietz|first=Dan|title=Off Broadway Musicals, 1910–2007: Casts, Credits, Songs, Critical Reception and Performance Data of More Than 1,800 Shows|publisher=McFarland|year=2010|isbn=978-0786457311}}</ref>{{Rp|310}} | |||

| During the 1990s, playwright Lynn Schrichte wrote and toured ''Did You Lie, Nellie Bly?'', a one-woman show about Bly.<ref>{{Cite web |url= https://www.loc.gov/rr/women/schrichte.html |title=Lynn Schrichte |website=Resourceful Women |publisher=Library of Congress |access-date= January 24, 2018 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20180125015902/https://www.loc.gov/rr/women/schrichte.html |archive-date=January 25, 2018 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| An opera based on 10 Days in a Madhouse premiered in Philadelphia, PA in September 2023. The music was by Rene Orth and the libretto by Hannah Moscovitch.<ref>{{cite news | last=Brodeur | first=Michael Andor | title=A reporter feigned madness to expose abuse. Now it's an unnerving opera. | newspaper=Washington Post | date=September 22, 2023 | url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/music/2023/09/22/opera-philadelphia-madhouse-review/ | access-date=October 1, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ===Film and television=== | |||

| Bly has been portrayed in the films '']'' (1981),<ref>{{cite news | newspaper=The New York Times | date=March 4, 2016 | title=The Adventures of Nellie Bly (1981) | url=http://www.nytimes.com/movies/movie/982/The-Adventures-of-Nellie-Bly/overview | archive-date=March 4, 2016 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304144451/http://www.nytimes.com/movies/movie/982/The-Adventures-of-Nellie-Bly/overview}}</ref> '']'' (2015),<ref>{{Cite web|title=Fearless Feminist Reporter Nellie Bly Hits the Big Screen | work= Ms. Magazine| date= November 11, 2015| url=https://msmagazine.com/2015/11/11/fearless-feminist-reporter-nellie-bly-hits-the-big-screen/|access-date=July 20, 2020}}</ref> and '']'' (2019).<ref>{{Cite web|last=Bentley|first=Rick|title=Judith Light hopes 'The Nellie Bly Story' will prompt mental health discussions| url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/tv/ct-ent-nellie-bly-judith-light-0117-story.html|access-date=July 20, 2020|website=Chicago Tribune|date=January 17, 2019 }}</ref> In 2019, the ] released ''Nellie Bly Makes the News'', a short animated biographical film.{{sfn|Reveal|2017}} A fictionalized version of Bly as a mouse named Nellie Brie appears as a central character in the animated children's film '']''.<ref>{{Cite web|date=February 11, 2015|title=Nellie Bly |url= https://popularpittsburgh.com/nellie-bly/|access-date=July 20, 2020|website=Popular Pittsburgh|language=en-US}}</ref> The character of Lana Winters (]) in '']'' is inspired by Bly's experience in the asylum.<ref>{{Cite magazine|last=Eidell|first=Lynsey|date=October 7, 2015 |title=All the Real-Life Scary Stories Told on American Horror Story| url= https://www.glamour.com/story/all-of-the-real-life-scary-sto|magazine=Glamour|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180619063553/https://www.glamour.com/story/all-of-the-real-life-scary-sto|archive-date=June 19, 2018|access-date=January 24, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> Bly was a subject of Season 2 Episode 5 of '']'' in which First Lady Abbey Bartlet dedicates a memorial in Pennsylvania in honor of Nellie Bly and convinces the president to mention her and other female historic figures during his weekly radio address.<ref>{{Cite magazine|last= MacIntosh|first=Selena|date=July 2011|title=Ladyghosts: The West Wing 2.05, 'And It's Surely to Their Credit' |url= http://persephonemagazine.com/2011/07/ladyghosts-the-west-wing-2-05-and-its-surely-to-their-credit/|magazine=Persephone|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120205045243/http://persephonemagazine.com/2011/07/ladyghosts-the-west-wing-2-05-and-its-surely-to-their-credit/|archive-date=February 5, 2012|access-date=January 24, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> On May 5, 2015, the Google search engine produced an interactive "Google Doodle" for Bly; for the "Google Doodle" ] wrote, composed, and recorded an original song about Bly, and Katy Wu created an animation set to Karen O's music.<ref>{{Cite web|date=May 4, 2015|title=What Girls are Good For: Happy birthday Nellie Bly| url= http://googleblog.blogspot.com.au/2015/05/what-girls-are-good-for-happy-birthday.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150507224547/http://googleblog.blogspot.com.au/2015/05/what-girls-are-good-for-happy-birthday.html|archive-date=May 7, 2015|access-date=May 5, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ===Audio drama=== | |||

| Nellie’s story was adapted into a Doctor Who audio drama by Big Finish Productions, released on 8 September 2021. ''The Perils of Nellie Bly'' was the second story in a three story box set, and was written by Sarah Ward.<ref>{{cite web | title=Many happy returns, Peter Davison! | website=Big Finish | date=April 13, 2021 | url=https://www.bigfinish.com/news/v/many-happy-returns-peter-davison | access-date=May 10, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ===Literature=== | |||

| Bly has been featured as the protagonist of novels by ],<ref>{{Cite web|title=What Girls Are Good For - A Novel Of Nellie Bly|url=https://www.nextchapter.pub/books/what-girls-are-good-for-novel-nellie-bly|access-date=2021-04-28|website=Next Chapter|date=September 20, 2019 |language=en-US}}</ref> Marshall Goldberg,<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://diversionbooks.com/ebooks/new-colossus |title=The New Colossus |website=diversionbooks.com/ebooks/new-colossus |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140424100418/http://diversionbooks.com/ebooks/new-colossus |archive-date=April 24, 2014 |access-date=April 29, 2014 }}</ref> Dan Jorgensen,<ref>{{Cite news |url= https://www.usatoday.com/story/jillcallison/2015/03/23/dan-jorgensen-wind-whispered-black-hills-history-nellie-bly--gold/70325778/ |title= Author: There's gold in them thar southern Black Hills |last=Callison |first=Jill |date=March 23, 2015 |work=] |access-date=January 24, 2018 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20180125032351/https://www.usatoday.com/story/jillcallison/2015/03/23/dan-jorgensen-wind-whispered-black-hills-history-nellie-bly--gold/70325778/ |archive-date=January 25, 2018 |url-status= live }}</ref> Carol McCleary,<ref>{{Cite web| title=Books |url= http://www.carolmccleary.com/Books.html|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160514200741/http://www.carolmccleary.com/Books.html|archive-date=May 14, 2016|access-date=January 24, 2018|publisher=Carol McCleary}}</ref> ], Maya Rodale,<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Mad Girls of New York: A Nellie Bly Novel |url=https://www.mayarodale.com/mad-girls-new-york |access-date=2023-01-11 |website=Maya Rodale |language=en-US}}</ref> Christine Converse <ref>{{Cite web|title=Bedlam Stories |url= http://www.bedlamstories.com|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131001155736/http://www.bedlamstories.com/|archive-date=October 1, 2013|access-date=September 24, 2013}}</ref> and Louisa Treger <ref>{{Cite web|title=Madwoman|url=https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/madwoman-9781526637161/}}</ref> ] also appeared on a March 10, 2021 episode of the podcast Broads You Should Know as a Nellie Bly expert.<ref name="Broads You Should Know">{{cite web|author=Broads You Should Know|title=Nellie Bly|url= https://broadsyoushouldknow.com/nellie-bly/|year=2021}}</ref> | |||

| A fictionalized account of Bly's around-the-world trip was used in the 2010 comic book ''Julie Walker Is The Phantom'' published by Moonstone Books (Story: ], art: Paul Daly, colors: Stephen Downer).<ref>{{Cite web|title=024. Julie Walker: The Phantom (A)| url=http://moonstonebooks.com/shop/item.aspx?itemid=500|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130729115453/http://moonstonebooks.com/shop/item.aspx?itemid=500|archive-date=July 29, 2013|access-date=July 20, 2013| website=Moonstonebooks.com}}</ref> | |||

| Bly is one of 100 women featured in the first version of the book '']'' written by Elena Favilli & Francesca Cavallo.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Establishment|first=The|date=2016-05-22|title=New Book Gives Rebel Girls The Bedtime Tales They Deserve|url=https://theestablishment.co/new-book-gives-rebel-girls-the-bedtime-tales-they-deserve-e832506af968/|access-date=2021-11-05|website=The Establishment|language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| ===Eponyms and namesakes=== | |||

| The board game ''Round the World with Nellie Bly'' created in 1890 is named in recognition of her trip.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Round the world with Nellie Bly – The Worlds globe circler| year= 1890| url= https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002716792/|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180125015842/http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002716792/|archive-date=January 25, 2018|access-date=January 24, 2018|publisher=Library of Congress}}</ref> | |||

| The Nellie Bly Amusement Park in Brooklyn, New York City, was named after her, taking as its theme ''Around the World in Eighty Days''. The park reopened in 2007<ref>{{Cite web |url= http://www.ultimaterollercoaster.com/themeparks/nelliebly_ny/ |title= Adventurer's Amusement Park|publisher=UltimaterollerCoaster.com |access-date= May 5, 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150728011039/http://www.ultimaterollercoaster.com/themeparks/nelliebly_ny |archive-date=July 28, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> under new management, renamed "Adventurers Amusement Park".<ref>{{Cite web |url= http://www.adventurerspark.com/index.php |title=Adventurer's Park Family Entertainment Center – Brooklyn, NY |website=adventurerspark.com |access-date=May 5, 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150503225626/http://www.adventurerspark.com/index.php |archive-date=May 3, 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| A large species of ] from ], ''Pamphobeteus nellieblyae'' Sherwood ''et al.'', 2022, was named in her honour by arachnologists.<ref>Sherwood, D., Gabriel, R., Brescovit, A. D. & Lucas, S. M. (2022). "On the species of Pamphobeteus Pocock, 1901 deposited in the Natural History Museum, London, with redescriptions of type material, the first record of P. grandis Bertani, Fukushima & Silva, 2008 from Peru, and the description of four new species". ''Arachnology'' 19(3): 650–674. </ref> | |||

| A ] named ] operated in ], in the first decade of the 20th century.<ref name="BlogTO2013-01" /> From early in the twentieth century until 1961, the ] operated an ] named the ''Nellie Bly'' on a route between New York and ], bypassing Philadelphia. | |||

| <gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> | |||

| File:Tugboat and part-time fireboat Nellie Bly, in Toronto, in 1908.jpg| A steam tug named after Bly served as a ] in ], Ontario, Canada.<ref name=BlogTO2013-01/> | |||

| File:RoundTheWorldWithNellieBly.jpg|Cover of the 1890 board game ''Round the World with Nellie Bly'' | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Works== | |||

| Within her lifetime, Nellie Bly published three non-fiction books (compilations of her newspaper reportage) and one novel in book form. | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Bly|first=Nellie|url=http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/bly/madhouse/madhouse.html|title=Ten Days in a Mad-House|publisher=Ian L. Munro|year=1887|location=New York}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Bly|first=Nellie|url=http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/bly/mexico/mexico.html|title=Six Months in Mexico|publisher=American Publishers Corporation|year=1888|location=New York}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Bly|first=Nellie|title=The Mystery of Central Park|year=1889|location=New York|publisher=G. W. Dillingham|url=https://archive.org/details/mysteryofcentral00coch/page/n7/}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Bly|first=Nellie|url=http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/bly/world/world.html|title=Nellie Bly's Book: Around the World in Seventy-two Days|publisher=The Pictorial Weeklies Company|year=1890|location=New York}} | |||

| Between 1889 and 1895, Nellie Bly also penned twelve novels for ''The New York Family Story Paper.'' Thought lost, these novels were not collected in book form until their re-discovery in 2021.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://pulp.aadl.org/node/576976 |title=Ann Arbor Native David Blixt Discovered a Cache of Long Lost Novels by Journalist-Adventurer Nellie Bly |first=Jenn |last=McKee |date=February 3, 2021 |work=Pulp | Arts Around Ann Arbor |access-date=November 21, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| * ''Eva The Adventuress'' (1889) | |||

| * ''New York By Night'' (1890) | |||

| * ''Alta Lynn, M.D.'' (1891) | |||

| * ''Wayne's Faithful Sweetheart'' (1891) | |||

| * ''Little Luckie, or Playing For Hearts'' (1892) | |||

| * ''Dolly The Coquette'' (1892) | |||

| * ''In Love With A Stranger, or Through Fire And Water To Win Him'' (1893) | |||

| * ''The Love Of Three Girls'' (1893) | |||

| * ''Little Penny, Child Of The Streets'' (1893) | |||

| * ''Pretty Merribelle'' (1894) | |||

| * ''Twins & Rivals'' (1895) | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Portal|New York City|Journalism|Biography}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ], a psychiatric patient who sued over non-consensual administration of anti-psychotic medicine | |||

| * ], another pioneering female journalist | |||

| * ], who raced Nellie around the globe for a competing publisher | |||

| * '']'', 2001 Brazilian film about life in a mental hospital | |||

| * ], actress who was involuntarily committed to mental hospitals | |||

| * ], 1970s, being sane in an insane place | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist|colwidth=30em|refs= | |||

| * Bly, Nellie (1887). ''].'' | |||

| <ref name=BlogTO2013-01>{{cite news | |||

| * Kroeger, Brooke (1994). ''Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist.'' | |||

| |url = https://www.blogto.com/city/2013/01/the_nautical_adventures_of_the_trillium_ferry_in_toronto/ | |||

| * Affidavit of Beatrice K. Brown; Surrogates Court, Kings County (1922) | |||

| |title = The nautical adventures of the Trillium ferry in Toronto | |||

| |work = ] | |||

| |author = Chris Bateman | |||

| |date = 2013 | |||

| |access-date = August 11, 2018 | |||

| |quote = A second fire boat, the Nellie Bly, presumably named after the American journalist famous for her round-the-world trip and exposé piece of US mental health practices, was also involved. {{'}}Their combined efforts prevented the fire from spreading,{{'}} noted the Star. | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20180828001819/https://www.blogto.com/city/2013/01/the_nautical_adventures_of_the_trillium_ferry_in_toronto/ | |||

| |archive-date = August 28, 2018 | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| === Sources === | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Ruddick|first=Nicholas|year=1999|title=Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age|journal=Canadian Review of American Studies|volume=29|issue=1|pages=1–12|doi=10.3138/CRAS-029-01-01|s2cid=159883003}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |title=Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist |last=Kroeger |first=Brooke |author-link=Brooke Kroeger|publisher=Three Rivers Press |year=1994 |isbn=978-0812925258 }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal|title=Bly, Nellie|last=Kroeger|first=Brooke|date=February 2000|journal=American National Biography|doi=10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1601472}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Linford |first=Autumn Lorimer |date=2022 |title=Nellie Bly Merchandise and the Changing American Woman: A Material Culture Study |journal=] |volume=39 |issue=1 |pages=72–91 |doi=10.1080/08821127.2022.2026195}} | |||

| * {{Cite web|ref={{harvid|Reveal|2017}}|author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.-->|title=Nellie Bly Makes the News|url=https://www.revealnews.org/article/nellie-bly-makes-the-news/|date=2017|website=Reveal|publisher=The Center for Investigative Reporting|access-date=May 11, 2020}} | |||

| == |

==Further reading== | ||

| {{Library resources box|by=yes|onlinebooksby=yes|viaf=816475}} | |||

| {{Reflist|group=fn|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|title=Following Nellie Bly: Her Record-Breaking Race Around the World |last=Brown |first=Rosemary J. |publisher=Pen & Sword Books Ltd |year=2021 |isbn=978-1526761408 }} | |||

| {{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|title=Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland's History-Making Race Around the World|last=Goodman|first=Matthew|year=2013|publisher=Ballantine Books |isbn=978-0345527264}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Lutes|first=Jean Marie|date=June 2002|title=Into the Madhouse with Nellie Bly: Girl Stunt Reporting in Late Nineteenth-Century America|url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/2536|journal=American Quarterly|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|volume=54|issue=2|pages=217–253|doi=10.1353/aq.2002.0017|s2cid=143667078|via=Project MUSE}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Mahoney|first=Ellen|date=Summer 2017|title=Nellie Bly: Pioneer journalist extraordinaire|url=https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/60927/60658|journal=Western Pennsylvania History|pages=32–45}} | |||

| * {{Cite thesis|last=Parham|first=Stacey Gaines|title=Nellie Bly, "the best reporter in America": one woman's rhetorical legacy|year=2010|degree=PhD|publisher=The University of Alabama|url=https://ir.ua.edu/bitstream/handle/123456789/793/file_1.pdf?sequence=1}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Randall|first=David|title=The Great Reporters|publisher=Pluto Press|year=2005|isbn=0745322972|location=London|pages=93–113|chapter=Nellie Bly: The best undercover reporter in history}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Rittenhouse|first=Mignon|title=The Amazing Nellie Bly|publisher=Dutton|year=1956 | oclc=299483}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Roggenkamp|first=Karen|title=Sympathy, Madness, and Crime: How Four Nineteenth-century Journalists Made the Newspaper Women's Business|publisher=Kent State University Press|year=2016|isbn=978-1606352878}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last=Vengadasalam|first=Puja|date=September 10, 2018|title=Dislocating the Masculine: How Nellie Bly Feminised Her Reports|journal=Social Change|volume=48|issue=3|pages=451–458|doi=10.1177/0049085718781597|s2cid=149576773|doi-access=free}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{sister project links|d=Q230299|n=no|s=Author:Elizabeth Jane Cochrane|v=no|voy=no|m=no|mw=no|q=no|species=no|wikt=no|b=no}} | |||

| *{{commonscat-inline|Nellie Bly}} | |||

| * Information, photos and original Nellie Bly articles at | |||

| *{{wikisource-inline|Author:Nellie Bly|Nellie Bly}} | |||

| * | |||

| *Information, photos and original Nellie Bly articles at : | |||

| * |

* Nellie Bly's collected journalism at | ||

| * Norwood, Arlisha. . National Women's History Museum. 2017. | |||

| ** | |||

| * '''' illustrated biography by ], reviewed by ] | |||

| ** | |||

| * {{Gutenberg author | id=9648 | name=Nellie Bly}} | |||

| ** | |||

| * {{Internet Archive author |sname=Nellie Bly}} | |||

| *{{Find a Grave|grid=106}} | |||

| * {{Librivox author |id=4117}} | |||

| * | |||

| *] | , a documentary about Bly's trip around the world. | |||

| * | |||

| *Nellie Bly Park | |||

| * | |||

| {{National Women's Hall of Fame}} | {{National Women's Hall of Fame}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{Authority control|VIAF=816475}} | |||

| {{Persondata <!-- Metadata: see ]. --> | |||

| | NAME = Bly, Nellie | |||

| | ALTERNATIVE NAMES = Cochran, Elizabeth Jane | |||

| | SHORT DESCRIPTION = American journalist | |||

| | DATE OF BIRTH = May 5, 1864 | |||

| | PLACE OF BIRTH = ], ] | |||

| | DATE OF DEATH = January 27, 1922 | |||

| | PLACE OF DEATH = ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Bly, Nellie}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Bly, Nellie}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 02:37, 20 January 2025

American investigative journalist (1864–1922) For the fictional character, see "Frankie and Johnny".

| Nellie Bly | |

|---|---|

Cochran at 26 years old, c. 1890 Cochran at 26 years old, c. 1890 | |

| Born | Elizabeth Jane Cochran (1864-05-05)May 5, 1864 Burrell Township, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | January 27, 1922(1922-01-27) (aged 57) New York City, U.S. |

| Pen name | Elly Cochran, Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, and most commonly known as Nellie Bly as her pen-name |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | English |

| Notable awards | National Women's Hall of Fame (1998) |

| Spouse |

Robert Seaman

(m. 1895; died 1904) |

| Signature | |

| |

Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran; May 5, 1864 – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was an American journalist who was widely known for her record-breaking trip around the world in 72 days in emulation of Jules Verne's fictional character Phileas Fogg and an exposé in which she worked undercover to report on a mental institution from within. She pioneered her field and launched a new kind of investigative journalism.

Early life

Elizabeth Jane Cochran was born May 5, 1864, in "Cochran's Mills", now part of Burrell Township, Armstrong County, Pennsylvania. Her father, Michael Cochran, born about 1810, started as a laborer and mill worker before buying the local mill and most of the land surrounding his family farmhouse. He later became a merchant, postmaster, and associate justice at Cochran's Mills (named after him) in Pennsylvania. Michael married twice. He had 10 children with his first wife, Catherine Murphy, and five more children, including Elizabeth Cochran, his thirteenth daughter, with his second wife, Mary Jane Kennedy. Michael Cochran died in 1870, when Elizabeth was 6.

As a young girl, Elizabeth often was called "Pink" because she so frequently wore that color. As she became a teenager, she wanted to portray herself as more sophisticated, and she dropped the nickname and changed her surname to "Cochrane". In 1879, she enrolled at Indiana Normal School (now Indiana University of Pennsylvania) for one term but was forced to drop out due to lack of funds. In 1880, Cochrane's mother moved her family to Allegheny City, which was later annexed by the City of Pittsburgh.

Career

Pittsburgh Dispatch

In 1885, a column in the Pittsburgh Dispatch titled "What Girls Are Good For" stated that girls were principally for birthing children and keeping house. This prompted Elizabeth to write a response under the pseudonym "Lonely Orphan Girl". The editor, George Madden, was impressed with her passion and ran an advertisement asking the author to identify herself. When Cochran introduced herself to the editor, he offered her the opportunity to write a piece for the newspaper, again under the pseudonym "Lonely Orphan Girl". Her first article for the Dispatch, titled "The Girl Puzzle", argued that not all women would marry and that what was needed were better jobs for women.

Her second article, "Mad Marriages", was about how divorce affected women. In it, she argued for reform of divorce laws. "Mad Marriages" was published under the byline of Nellie Bly, rather than "Lonely Orphan Girl" because, at the time, it was customary for female journalists to use pen names to conceal their gender so that readers would not discredit them. The editor chose "Nellie Bly", after the African-American title character in the popular song "Nelly Bly" by Stephen Foster. Cochrane originally intended that her pseudonym be "Nelly Bly", but her editor wrote "Nellie" by mistake, and the error stuck. Madden was impressed again and offered her a full-time job.

As a writer, Nellie Bly focused her early work for the Pittsburgh Dispatch on the lives of working women, writing a series of investigative articles on female factory workers. However, the newspaper soon received complaints from factory owners about her writing, and she was reassigned to women's pages to cover fashion, society, and gardening, the usual role for female journalists, and she became dissatisfied. Still only 21, she was determined "to do something no girl has done before." She then traveled to Mexico to serve as a foreign correspondent, spending nearly half a year reporting on the lives and customs of the Mexican people. Her dispatches later were published in book form as Six Months in Mexico. In one report, she protested the imprisonment of a local journalist for criticizing the Mexican government, then a dictatorship under Porfirio Díaz. When Mexican authorities learned of Bly's report, they threatened her with arrest, prompting her to flee the country. Safely home, she accused Díaz of being a tyrannical czar suppressing the Mexican people and controlling the press.

Asylum exposé

Main article: Ten Days in a Mad-House

Burdened again with theater and arts reporting, Bly left the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1887 for New York City. Bly faced rejection after rejection as news editors would not consider hiring a woman. Penniless after four months, she talked her way into the offices of Joseph Pulitzer's newspaper, the New York World, and took an undercover assignment for which she agreed to feign insanity to investigate reports of brutality and neglect at the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island, now named Roosevelt Island.

It was not easy for Bly to be admitted to the asylum: she first decided to check herself into a boarding house called "Temporary Homes for Females". She stayed up all night to give herself the wide-eyed look of a disturbed woman and began making accusations that the other boarders were insane. Bly told the assistant matron: "There are so many crazy people about, and one can never tell what they will do." She refused to go to bed and eventually scared so many of the other boarders that the police were called to take her to the nearby courthouse. Once examined by a police officer, a judge, and a doctor, Bly was taken to Bellevue Hospital for a few days, then after evaluation was sent by boat to Blackwell's Island.

Committed to the asylum, Bly experienced the deplorable conditions firsthand. After ten days, the asylum released Bly at The World's behest. Her report, published October 9, 1887 and later in book form as Ten Days in a Mad-House, caused a sensation, prompted the asylum to implement reforms, and brought her lasting fame. Nellie Bly had a significant impact on American culture and shed light on the experiences of marginalized women beyond the bounds of the asylum as she ushered in the era of stunt girl journalism.

In 1893, Bly used the celebrity status she had gained from her asylum reporting skills to schedule an exclusive interview with the allegedly insane serial killer Lizzie Halliday.

Biographer Brooke Kroeger argues:

- Her two-part series in October 1887 was a sensation, effectively launching the decade of "stunt" or "detective" reporting, a clear precursor to investigative journalism and one of Joseph Pulitzer's innovations that helped give "New Journalism" of the 1880s and 1890s its moniker. The employment of "stunt girls" has often been dismissed as a circulation-boosting gimmick of the sensationalist press. However, the genre also provided women with their first collective opportunity to demonstrate that, as a class, they had the skills necessary for the highest level of general reporting. The stunt girls, with Bly as their prototype, were the first women to enter the journalistic mainstream in the twentieth century.

Around the world and general impact

Main article: Around the World in Seventy-Two Days

In 1888, Bly suggested to her editor at the New York World that she take a trip around the world, attempting to turn the fictional Around the World in Eighty Days (1873) into fact for the first time. A year later, at 9:40 a.m. on November 14, 1889, and with two days' notice, she boarded the Augusta Victoria, a steamer of the Hamburg America Line, and began her 24,898 mile (40,070 kilometer) journey.

To sustain interest in the story, the World organized a "Nellie Bly Guessing Match" in which readers were asked to estimate Bly's arrival time to the second, with the Grand Prize consisting at first of a trip to Europe and, later on, spending money for the trip. During her travels around the world, Bly went through England, France (where she met Jules Verne in Amiens), Brindisi, the Suez Canal, Colombo (in Ceylon), the Straits Settlements of Penang and Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan.

Just over seventy-two days after her initial departure, Bly arrived in New York on January 25, 1890, completing her circumnavigation of the globe. She had traveled alone for almost the entire journey. Bly's journey was a world record, though it only stood for a few months, until George Francis Train completed the journey in 67 days.

Novelist

After the fanfare of her trip around the world, Bly quit reporting and took a lucrative job writing serial novels for publisher Norman Munro's weekly New York Family Story Paper. The first chapters of Eva The Adventuress, based on the real-life trial of Eva Hamilton, appeared in print before Bly returned to New York. Between 1889 and 1895 she wrote eleven novels. As few copies of the paper survived, these novels were thought lost until 2021, when author David Blixt announced the discovery of 11 lost novels in Munro's British weekly The London Story Paper. In 1893, though still writing novels, she returned to reporting for the World.

Later work

In 1895, Bly married millionaire manufacturer Robert Seaman. Bly was 31 and Seaman was 73 when they married. Due to her husband's failing health, she left journalism and succeeded her husband as head of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co., which made steel containers such as milk cans and boilers. Seaman died in 1904.

That same year, Iron Clad began manufacturing the steel barrel that was the model for the 55-gallon oil drum still in widespread use in the United States. There have been claims that Bly invented the barrel, but the inventor was registered as Henry Wehrhahn (U.S. Patents 808,327 and 808,413).

Bly was also an inventor in her own right, receiving U.S. patent 697,553 for a novel milk can and U.S. patent 703,711 for a stacking garbage can, both under her married name of Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman. For a time, she was one of the leading women industrialists in the United States. But her negligence, and embezzlement by a factory manager, resulted in the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co. going bankrupt.

According to biographer Brooke Kroeger:

She ran her company as a model of social welfare, replete with health benefits and recreational facilities. But Bly was hopeless at understanding the financial aspects of her business and ultimately lost everything. Unscrupulous employees bilked the firm of hundreds of thousands of dollars, troubles compounded by protracted and costly bankruptcy litigation.

Back in reporting, she covered the Woman Suffrage Procession of 1913 for the New York Evening Journal. Her article's headline was "Suffragists Are Men's Superiors" and in its text she accurately predicted that women in the United States would be given the right to vote in 1920.

Bly wrote stories on Europe's Eastern Front during World War I. Bly was the first woman and one of the first foreigners to visit the war zone between Serbia and Austria. She was arrested when she was mistaken for a British spy.

Death

On January 27, 1922, Bly died of pneumonia at St. Mark's Hospital, New York City, aged 57. She was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Legacy

Honors

In 1998, Bly was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

Bly was one of four journalists honored with a US postage stamp in a "Women in Journalism" set in 2002.

In 2019, the Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation put out an open call for artists to create a Nellie Bly Memorial art installation on Roosevelt Island. The winning proposal, The Girl Puzzle by Amanda Matthews, was announced on October 16, 2019. The Girl Puzzle opened to the public in December, 2021.

The New York Press Club confers an annual Nellie Bly Cub Reporter journalism award to acknowledge the best journalistic effort by an individual with three years or fewer of professional experience. In 2020, it was awarded to Claudia Irizarry Aponte, of THE CITY.

Theater

Bly was the subject of the 1946 Broadway musical Nellie Bly by Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen. The show ran for 16 performances.

During the 1990s, playwright Lynn Schrichte wrote and toured Did You Lie, Nellie Bly?, a one-woman show about Bly.

An opera based on 10 Days in a Madhouse premiered in Philadelphia, PA in September 2023. The music was by Rene Orth and the libretto by Hannah Moscovitch.

Film and television