| Revision as of 14:06, 2 April 2013 editVolunteer Marek (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers94,174 edits →Westward expansion of Wartislaw I: sources have been provided, dispute seems to have ended← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:41, 2 November 2024 edit undoHam II (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers56,738 edits Set {{DEFAULTSORT}} to Pomerania In The High Middle Ages using HotDefaultSort | ||

| (99 intermediate revisions by 45 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{Too few opinions|date=April 2011}} | {{Too few opinions|date=April 2011}} | ||

| {{POV|date=January 2011}} | |||

| {{History of Pomerania}} | {{History of Pomerania}} | ||

| '''Pomerania during the High Middle Ages''' covers the ] in the 12th and 13th centuries. | '''Pomerania during the High Middle Ages''' covers the ] in the 12th and 13th centuries. | ||

| The early 12th century ], ], ], and ] conquests resulted in ] and ] of the formerly pagan and independent ]n tribes.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40">Krause (1997), p.40</ref><ref name="Addison 2003, pp.57ff">Addison (2003), pp.57ff</ref><ref name="Buchholz p.25"/><ref name="Herrmann, pp.384ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.384ff</ref> Local dynasties ruled the ] (House of Wizlaw), the ] (], "Griffins"), the ] (Ratiboride branch of the Griffins), and the duchies in ] (]).<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40"/> | The early 12th century ], ], ], and ] conquests resulted in ] and ] of the formerly pagan and independent ]n tribes.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40">Krause (1997), p.40</ref><ref name="Addison 2003, pp.57ff">Addison (2003), pp.57ff</ref><ref name="Buchholz p.25"/><ref name="Herrmann, pp.384ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.384ff</ref> Local dynasties ruled the ] (House of Wizlaw), the ] (], "Griffins"), the ] (Ratiboride branch of the Griffins), and the duchies in ] (]).<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40"/> | ||

| Line 8: | Line 10: | ||

| The ] expanded their realm into ] and ] to the southwest, and competed with the ] and the ] for territory and formal overlordship over their duchies. Pomerania-Demmin lost most of its territory and was integrated into Pomerania-Stettin in the mid-13th century. When the Ratiborides died out in 1223, competition arose for the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp,<ref name="Buchholz p.87">Buchholz (1999), p.87</ref> which changed hands numerous times. | The ] expanded their realm into ] and ] to the southwest, and competed with the ] and the ] for territory and formal overlordship over their duchies. Pomerania-Demmin lost most of its territory and was integrated into Pomerania-Stettin in the mid-13th century. When the Ratiborides died out in 1223, competition arose for the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp,<ref name="Buchholz p.87">Buchholz (1999), p.87</ref> which changed hands numerous times. | ||

| Starting in the High Middle Ages, a large influx of German settlers and the introduction of German law, custom, and ] language |

Starting in the High Middle Ages, a large influx of German settlers and the introduction of German law, custom, and ] language began the process of Germanisation (]). Many of the people groups that had dominated the area ], such as the ] ], ] and ] tribes, were assimilated into the new ] culture. The Germanisation was not complete, as the ], descendants of ], dominated many rural areas in ]. The arrival of German colonists and Germanization mostly affected both the central and local administration.<ref> Pomorze słowiańskie, Pomorze germańskie, Biuletyn Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego</ref> | ||

| The Germanisation was not complete, however, and in particular ], descendants of ], dominated many rural areas in ]. With the arrival of German colonists and Germanization the local population was pushed away by the newcomers from both central and local administration.<ref> Pomorze słowiańskie, Pomorze germańskie, Biuletyn Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego</ref> | |||

| Some publications claim that most of the present-day towns were founded{{Clarify|date=April 2011}} during the Ostsiedlung.<ref>Inachin (2008), p. 26, ]</ref> Others insist that urban development was already in progress before the Ostsiedlung and theories that urban development was brought to areas such as Pomerania, Mecklenburg or Poland by Germans are now discarded.<ref>The German Hansa P. Dollinger, page 16, Routledge 1999</ref> | |||

| The ] to ] was achieved primarily by the missionary efforts of ] and ], by the foundation of numerous monasteries, and through the Christian clergy and settlers. ] was set up in ], the see was later moved to ] (Kammin, Kamień Pomorski). | The ] to ] was achieved primarily by the missionary efforts of ] and ], by the foundation of numerous monasteries, and through the Christian clergy and settlers. ] was set up in ], the see was later moved to ] (Kammin, Kamień Pomorski). | ||

| == Obodrite realm ( |

== Obodrite realm (1093–1128) == | ||

| After the ], and following the victory of ] prince ] in the ] in 1093, ] reported that among others the ],<ref name=Herrmann379>Herrmann (1985), p.379</ref> ]<ref name=Herrmann379/> and ]<ref name=Herrmann379/> had to pay tribute to Obodrite prince Henry.<ref name=Herrmann379/><ref name=Herrmann367>Herrmann (1985), p.367</ref> The Rani however launched a naval expedition in 1100, in the course of which they sieged ], a predecessor of modern ] and then the Obodrite capitol.<ref name=Herrmann268>Herrmann (1985), p.268</ref> This attack was however repulsed, and the Rani became tributary again.<ref name=Herrmann379/><ref name=Herrmann268/> After they had killed Henry's son Woldemar and stopped paying tribute, Henry retaliated with two expeditions launched in the winters of 1123/24 and 1124/25, supported by ] and ] troops.<ref name=Herrmann379/> The Rani ] priests were forced to negotiate,<ref name=Herrmann268/> and the island was spared only in return for an immense sum which had to be collected from the continental Slavs further east. At this time, ], was already expanding his realm into Liutician territories south of the Rani. Regrouping after Henry's death (1127), the Rani again assaulted and this time destroyed Liubice in 1128,<ref name=Herrmann268/><ref name=Herrmann381>Herrmann (1985), p.381</ref> ending Obodrite influence in the Pomeranian territories. | |||

| After the ], and following the victory of ] prince ] in the ] in 1093, ] reported that among others the ],<ref name=Herrmann379>Herrmann (1985), p.379</ref> ]<ref name=Herrmann379/> and ]<ref name=Herrmann379/> had to pay tribute to Obodrite prince Henry.<ref name=Herrmann379/><ref name=Herrmann367>Herrmann (1985), p.367</ref> The Rani however launched a naval expedition in 1100, in the course of which they sieged ], a predecessor of modern ] and then the Obodrite capitol.<ref name=Herrmann268>Herrmann (1985), p.268</ref> This attack was however repulsed, and the Rani became tributary again.<ref name=Herrmann379/><ref name=Herrmann268/> After they had killed Henry's son Woldemar and stopped paying tribute, Henry retaliated with two expeditions launched in the winters of 1123/24 and 1124/25, supported by ] and ] troops.<ref name=Herrmann379/> The Rani ] priests were forced to negotiate,<ref name=Herrmann268/> and the island was spared only in return for an immense sum which had to be collected from the continental Slavs further east. At this time, ], was already expanding his realm into Liutician territories south of the Rani. Regrouping after Henry's death (1127), the Rani again assaulted and this time destroyed Liubice in 1128,<ref name=Herrmann268/><ref name=Herrmann381>Herrmann (1985), p.381</ref> ending Obodrite influence in the Pomeranian territories. | |||

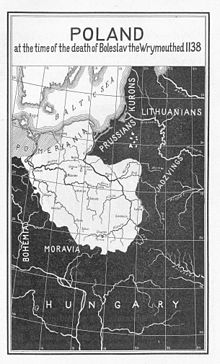

| == As part of Polish realm (1102/22–1138) == | == As part of Polish realm (1102/22–1138) == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In several expeditions mounted between 1102<ref>Richard Roepell: ''Geschichte Polens'', vol. I. Hamburg 1840, </ref> and 1121,<ref name="RR">Richard Roepell: ''Geschichte Polens'', vol. I, |

In several expeditions mounted between 1102<ref>Richard Roepell: ''Geschichte Polens'', vol. I. Hamburg 1840, </ref> and 1121,<ref name="RR">Richard Roepell: ''Geschichte Polens'', vol. I, Hamburg 1840, </ref> most of Pomerania had been acquired by the Polish duke ].<ref name=Piskorski35>Piskorski (1999), p.35</ref> | ||

| From 1102 to 1109, Boleslaw campaigned in the ] (Netze) and ] (Persante) area.<ref name=Piskorski36>Piskorski (1999), p.36</ref> The Pomeranian residence in Białogard (Belgard) was taken already in 1102.<ref name=Piskorski35/> From 1112 to 1116, Boleslaw took all of Pomerelia.<ref name=Piskorski36/> From 1119 to 1122, the area towards the ] was acquired.<ref name=Piskorski36/> Szczecin (Stettin) was taken in the winter of 1121/1122.<ref name=Piskorski36/> | From 1102 to 1109, Boleslaw campaigned in the ] (Netze) and ] (Persante) area.<ref name=Piskorski36>Piskorski (1999), p.36</ref> The Pomeranian residence in Białogard (Belgard) was taken already in 1102.<ref name=Piskorski35/> From 1112 to 1116, Boleslaw took all of Pomerelia.<ref name=Piskorski36/> From 1119 to 1122, the area towards the ] was acquired.<ref name=Piskorski36/> Szczecin (Stettin) was taken in the winter of 1121/1122.<ref name=Piskorski36/> | ||

| Line 30: | Line 26: | ||

| The conquest resulted in a high death toll and devastation of vast areas of Pomerania, and the Pomeranian dukes became vassals of Boleslaw III of Poland.<ref name="Addison 2003, pp.57ff"/><ref name="Buchholz p.25"/><ref name="Herrmann, pp.384ff"/> Deportations of Pomeranians to Poland took place.<ref name="RR"/><ref name=Heitz158>Heitz (1995), p.158</ref>{{Clarify|date=September 2009}} The terms of surrender after the Polish conquest were that Wartislaw had to accept Polish sovereignty, convert his people to Christianity, and pay an annual tribute to the Polish duke.<ref name="Buchholz p.25"/> | The conquest resulted in a high death toll and devastation of vast areas of Pomerania, and the Pomeranian dukes became vassals of Boleslaw III of Poland.<ref name="Addison 2003, pp.57ff"/><ref name="Buchholz p.25"/><ref name="Herrmann, pp.384ff"/> Deportations of Pomeranians to Poland took place.<ref name="RR"/><ref name=Heitz158>Heitz (1995), p.158</ref>{{Clarify|date=September 2009}} The terms of surrender after the Polish conquest were that Wartislaw had to accept Polish sovereignty, convert his people to Christianity, and pay an annual tribute to the Polish duke.<ref name="Buchholz p.25"/> | ||

| The Annals of Traska report that "Boleslaw III crossed the sea and captured castles."<ref>"1123 Boleslaus tercius mare transivit et castra obtinuit," ed. in , p. 832 . Cf. {{cite book|first=Mikolaj|last=Gladysz|title=The Forgotten Crusaders. Poland and the Crusader Movement in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries|location=Leiden|year=2012|page=36|isbn=978-9004185517|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=l9R2WMhnHHAC&pg=PA36}}; {{cite book|first=Nils|last=Blomkvist|title=The Discovery of the Baltic. The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (a.d. 1075–1225)|series=The Northern World|volume=15|location=Leiden|year=2005|page=330|isbn=9789004141223|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tyLZAAAAMAAJ&q=traski}}</ref> The currently prevailing view is that this mention refers to a campaign in Pomerania, but proposed targets also include the ], ]<ref name=Gladysz>{{cite book|first=Mikolaj|last=Gladysz|title=The Forgotten Crusaders. Poland and the Crusader Movement in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries|location=Leiden|year=2012|pages=36–38 and fn 96, 97, 102|isbn=978-9004185517|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=l9R2WMhnHHAC&pg=PA36}}</ref> and ].<ref>{{cite book|first=Nils|last=Blomkvist|title=The Discovery of the Baltic. The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (a.d. 1075–1225)|series=The Northern World|volume=15|location=Leiden|year=2005|page=332}}</ref> In Pomerania, Boleslaw's targets may have been Rügen/Rugia, Wolin/Wollin or Stettin/Szczecin.<ref name=Gladysz/><ref>Similarly {{cite book|first=Nils|last=Blomkvist|title=The Discovery of the Baltic. The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (a.d. 1075–1225)|series=The Northern World|volume=15|location=Leiden|year=2005|page=332|isbn=9789004141223|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tyLZAAAAMAAJ&q=traski}}: ''"In Polish research many suggestions have been made, from a mere crossing over Stettiner Bucht, to an assault on Rügen. Tyc states that the objective of Boleslaus' navigation remains unknown,"'' referring to {{cite book|first=Teodor|last=Tyc|title=Z średniowiecznych dziejów Wielkopolski i Pomorza: wybór prac. Zebrał i posłowiem opatrzył Jan M Piskorski|location=Poznań|year=1997|pages=206ff}}</ref> | |||

| ===List of Polish campaigns=== | |||

| {|class=wikitable | |||

| !colspan="2"|Expeditions of ] into the ] | |||

| |- | |||

| !Date | |||

| !Destination, notes | |||

| |- | |||

| |fall of 1102 | |||

| |]<ref name=Heitz157>Heitz (1995), p.157</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1103 | |||

| |Białogard, ] (Kolberg)<ref name=Heitz157/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1107 | |||

| |Kołobrzeg<ref name=Heitz157/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1108 | |||

| |] area (], Usch, ])<ref name=Heitz158/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |10 August 1109 | |||

| |]. Polish victory.<ref name=Heitz158/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1113 | |||

| |Nakło finally sacked by Boleslaw.<ref name=Heitz158/> Nakło and ]{{Clarify|date=February 2011}} become Polish.<ref name=Heitz157/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1112 to 1116 | |||

| |]. Polish victory.<ref name=Piskorski36/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1119-1121 | |||

| |] area. Polish victory.<ref name=Piskorski36/><ref name=Heitz158/> Szczecin captured in the winter of 1121/22.<ref name=Piskorski36/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1121 | |||

| |Expedition east of the Oder. Bolesław took control of ] (Kocków) and ] (Dymin), and campaigned in the area of ] (Stralsund) and ] lake.<ref name="Michalek">{{cite book | title=Słowianie Zachodni. Monarchie wczesnofeudalne | publisher=Bellona | author=Andrzej Michałek | year=2007 | pages=102 | isbn=978-83-11-10737-3}}</ref>{{Disputed-inline|talk=Misplaced Pages:Reliable_sources/Noticeboard#Andrzej_Michalek_.22Slowianie_Zachodni._Monarchie_Wczesnofeudalne.22|date=March 2013}}<ref name="Mal">{{cite book | url=http://www.polski.pro/_ld/9/997_Karol_Maleczysk.pdf | title=Bolesław III Krzywousty | publisher=Zakład Im. Ossolinskich | author=Maleczyński, Karol | year=1975 (1939)}}</ref>{{Failed verification|talk=Misplaced Pages:Reliable_sources/Noticeboard#Andrzej_Michalek_.22Slowianie_Zachodni._Monarchie_Wczesnofeudalne.22|date=March 2013}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Sometime between 1121-1130 | |||

| |Joint Polish-Danish invasion of ]. The ] accepted Polish suzerainty but Polish control didn't last.<ref name="Michalek"/>{{Disputed-inline|talk=Misplaced Pages:Reliable_sources/Noticeboard#Andrzej_Michalek_.22Slowianie_Zachodni._Monarchie_Wczesnofeudalne.22|date=March 2013}} | |||

| |} | |||

| == Emergence of Pomeranian dynasties - Samborides and Griffins == | == Emergence of Pomeranian dynasties - Samborides and Griffins == | ||

| {{Main article|Samborides|House of Pomerania}} | |||

| {{Main|Samborides|House of Pomerania}} | |||

| Pomerelia, initially under Polish control, was ruled by the Samborides dynasty from 1227 until 1294.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40"/> The duchy was split temporarily{{When|date=April 2011}} into districts of Gdańsk (Danzig), ], ] (Schwetz) and ]–] . | Pomerelia, initially under Polish control, was ruled by the Samborides dynasty from 1227 until 1294.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40"/> The duchy was split temporarily{{When|date=April 2011}} into districts of Gdańsk (Danzig), ], ] (Schwetz) and ]–] . | ||

| In ], |

In ], Polish rule ended with Boleslaw III's death in 1138.<ref name=Inachim17>Inachin (2008), p.17</ref><ref name="Herrmann, pp.386">Herrmann (1985), pp.386</ref><ref>Norman Davies, "God's Playground", Columbia University Press, 2005, pg 69</ref> The ] and ] areas (] were ruled by ] and his descendants (''Ratiboriden'' branch of the Griffin ]) until the Danish occupation and extinction of the Ratiboride branch in 1227. | ||

| The areas stretching from ] to Szczecin were ruled by Ratibor's brother ] and his descendants (], also called ''Griffins'', of which he was the first ascertained ancestor) until the 1630s.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40"/> | The areas stretching from ] to Szczecin were ruled by Ratibor's brother ] and his descendants (], also called ''Griffins'', of which he was the first ascertained ancestor) until the 1630s.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40"/> | ||

| == |

== Conversion of Pomerania == | ||

| {{Main|Conversion of Pomerania}} | {{Main article|Conversion of Pomerania|Otto von Bamberg}} | ||

| The first attempt to convert the ] to ] following the acquisition of Pomerania by ] was made in |

The first attempt to convert the ] to ] following the acquisition of Pomerania by ] was made in 1122. The ] monk ] (also Bernhard) travelled to Jumne (]), accompanied only by his chaplain and an interpreter. The Pomeranians however were not impressed by his missionary efforts and finally threw him out of town.<ref name="Buchholz p.25">Buchholz (1999), p.25</ref><ref name=Piskorski36/><ref>Maclear (1969), pp.218ff</ref> Bernard was later made ].<ref name="Buchholz p.25"/> | ||

| Bernard was later made ].<ref name="Buchholz p.25"/> | |||

| ==Otto of Bamberg's first mission (1124)== | |||

| ], in the monastery of Saint Michael in ] (], Germany)]] | ], in the monastery of Saint Michael in ] (], Germany)]] | ||

| {{Main|Conversion of Pomerania|Otto von Bamberg}} | |||

| After Bernard's misfortune, Boleslaw III asked ]<ref>Medley (2004), p.152</ref> to convert Pomerania to ], which he accomplished in his first visit in 1124/25.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff">Krause (1997), p.40ff</ref> Otto's strategy severely differed from the one Bernard used: While Bernard travelled alone and as a poor and unknown priest, Otto, a wealthy and famous man, was |

After Bernard's misfortune, Boleslaw III asked ]<ref>Medley (2004), p.152</ref> to convert Pomerania to ], which he accomplished in his first visit in 1124/25.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff">Krause (1997), p.40ff</ref> Otto's strategy severely differed from the one Bernard used: While Bernard travelled alone and as a poor and unknown priest, Otto, a wealthy and famous man, was accompanied by 20 clergy of his own diocese, numerous servants, 60 warriors supplied to him by Boleslaw, and carried with him numerous supplies and gifts. After arriving in ] (Pyrzyce), the Pomeranians were assured that Otto's aim was not the gain of wealth at the expense of the Pomeranian people, as he was wealthy already, but only to convert them to Christianity, which would protect the Pomeranians from further punishment by God, as which the devastating Polish conquest was depicted. This approach turned out to be successful, and was backed by parts of the Pomeranian nobility that in part was Christian raised already, like duke Wartislaw, who encouraged and promoted Otto's mission. Many Pomeranians were baptized already in Pyritz and also in the other burghs visited.<ref name="Buchholz p.25"/><ref>Addison (2003), pp.59ff</ref><ref name="Palmer, P.107ff">Palmer (2005), pp.107ff</ref><ref name="Herrmann, pp.402ff"/><ref>Piskorski (1999), pp.36ff</ref> | ||

| At this first mission, Otto founded at least eleven churches, two of those each in Szczecin and Wolin.<ref>Piskorski (1999), p.39</ref> | At this first mission, Otto founded at least eleven churches, two of those each in Szczecin and Wolin.<ref>Piskorski (1999), p.39</ref> | ||

| Line 95: | Line 50: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| == Westward expansion of Wartislaw I == | |||

| ] to ] and east of the ] to subjugate the Slavic ], in 1121. <ref name="Michalek">{{cite book | title=Słowianie Zachodni. Monarchie wczesnofeudalne | publisher=Bellona | author=Andrzej Michałek | year=2007 | pages=102 | isbn=978-83-11-10737-3}}</ref>]] | |||

| In the meantime, Wartislaw managed to conquer territories west of the ] river, an area inhabited by ] tribes weakened by past warfare, and included these territories into his ''Duchy of Pomerania''. Already in 1120, he had expanded west into the areas near the ] and ] river. Most notably ], the ] and ] were conquered in the following years.<ref name="Herrmann, pp.386"/> | |||

| The major stage of the westward expansion into Lutici territory occurred between Otto of Bamberg's two missions, 1124 and 1128. In 1128, Demmin, the County of Gützkow and Wolgast were already incorporated into Wartislaw I's realm, yet warfare was still going on.<ref name=Piskorski4041>Piskorski (1999), pp. 40,41</ref> Captured Lutici and other war loot, including livestock, money, and clothes were apportioned among the victorious.<ref name=Herrmann141>Herrmann (1985), p.141</ref> After Wartislaw's Lutician conquests, his duchy lay between the ] to the north, ], including ], to the west, Kolberg/Kolobrzeg in the east, and possibly as far as the ] and ] rivers in the south.<ref name=Piskorski41>Piskorski (1999), p.41</ref> | |||

| After the conquests, Wartislaw's realm stretched from the ] in the North and ] with ] in the West to the ] and possibly also the ] rivers in the South and the ] area in the east.<ref name=Piskorski41/> | |||

| These gains were not subject to Polish over lordship,<ref name=Inachim17/><ref name=Buske11/> but were placed under over lordship of ] ] ], who according to Bialecki was a dedicated enemy of Slavs,<ref>Historia Szczecina: | |||

| zarys dziejów miasta od czasów najdawniejszych do 1980, Tadeusz Białecki, page 53 Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1992 -</ref> by ].<ref name=Inachim17/> Thus, the western territories contributed to making Wartislaw significantly independent from the Polish dukes.<ref>Buske (1997), p.11 :"Durch die Eroberung des Peenegebiets, das nicht zum polnischen Einflußgebiet gehörte, gewann Wartislaw eine beachtliche Selbstständigkeit. Er konnte sich schließlich dauerhaft gegen Polen behaupten "</ref> Wartislaw was not the only one campaigning in these areas. The Polish duke Boleslaw III, during his Pomeranian campaign launched an expedition into the ] area in 1120/21,<ref name=Buske10/> before he turned back to subdue Wartislaw. The later ] Lothair III (then ] Lothair I of Supplinburg) in 1114 initiated large scale campaigns against the local Lutici tribes resulting in their final defeat in 1228.<ref name=Buske10>Buske (1997), p.10</ref>{{clarify|date=February 2011}} Also, the territories were invaded by Danish forces multiple times, who, coming from the ], used the rivers Peene and ] to advance to a line ]–].<ref name=Buske11>Buske (1997), p.11</ref> At different times, Pomeranians, Saxons and Danes were either allies or opponents.<ref name=Buske11/> The ] consolidated their power in the course of the 12th century, yet the preceding warfare had left these territories completely devastated.<ref name=Buske1112>Buske (1997), pp.11,12</ref> | |||

| == Society under Wartislaw I == | |||

| During Wartislaw I's rule society was composed of the Pomeranian freeman and the slaves, who consisted mostly of Wendish, German or Danish war captives. The freemen generally made their living from agriculture, fishing and husbandry, as well as hunting and trade.<ref name=Herrmann141/><ref name=Piskorski5154/> Their social status depended both on accumulated wealth as well as noble status. The proportion of slaves in the total population of the area was relatively small and in fact the Pomeranians exported slaves to Poland.<ref name=Herrmann141/><ref name=Piskorski5154>Piskorski (1999), pp.51,54</ref> | |||

| The largest settlements were Wollin (Wolin) and Stettin (Szczecin), each of which had a few thousand inhabitants, and a biweekly market day.<ref name=Piskorski54/> While some historians address these settlements as towns, this is rejected by others due to the differences to later towns. They are usually referred to as early towns, proto-towns, ]s or emporia; their Slavic designation was ''*grod'' (] in ] and ]).<ref group=nb name=A>In German historiography, larger pre-Ostsiedlung settlements comprising castles and suburbia are usually termed ''Burgstadt'' (lit. "castle town"), in contrast to the earlier emporia (''Seehandelsplätze'') at the Baltic coast and the later ''Rechtsstadt'' (lit. "law town") or communal town; both ''Burgstadt'' and emporia are also described as ''Frühstadt'' (lit. "early town"). The contemporary Slavic cognate of Burgstadt was ''*]'' ] and ]: ''gard'', it resembled the contemporary West European ''vicus'' and ''villa'' in structure and layout, but not the West European ''civitas'' markets. In Slavic-speaking regions, Ostsiedlung narrowed the meaning of ''*grod'' to denote the castles only, while towns were termed ''*město'' (orig. "site", ; in areas not affected by Ostsiedlung, towns were termed ''*grod'', cf. Russian ''город''). {{cite book|last=Brather|first=Sebastian|title=Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa|publisher=de Gruyter|year=2001|isbn=3-11-017061-2|pages=141f., 148, 154–155}} ] lacked a dedicated term for the ''Burgstadt'' settlements, contemporary documents refer to them as ''civitates, oppida'' or ''urbes'' {{cite journal|last=Brachmann|first=Hansjürgen|title=Von der Burg zur Stadt. Die Frühstadt in Ostmitteleuropa|year=1995|journal=Archaeologia historica|volume=20|pages=315–321; 315}} Schich (2007) rejected a proposal of Stoob (1986) to discontinue the use of compound words including "town" for these places, such as ''Protostadt'' (lit. "proto town"), ''Burgstadt'', ''Frühstadt'' and Stoob's own, earlier proposal ''Grodstadt'' (lit. "grod town"). Stoob says that this would suggests, unjustified, a relation to the high medieval towns. Schich says that "if - despite the undisputable break in the 'urban' development in this area - terms like ''Burgstadt'' and ''Frühstadt'' are used here, then this is based on a broader understanding of the term 'town.' ''Frühstadt'' then denotes an early form of town-like settlements preceeding the high medieval towns, without insinuating an evolution from ''Burgstadt'' or ''Frühstadt'' to the communal town." {{cite book|last=Schich|first=Winfried|chapter=|title=Wirtschaft und Kulturlandschaft|editor1-first=Winfried|editor1-last=Schich|editor2-first=Peter|editor2-last=Neumeister|publisher=BWV Verlag|year=2007|isbn=3-8305-0378-4|page=266}} Cf. also Benl, R, in Buchholz (1999), p. 75.</ref> The population of Pomerania was relatively wealthy in comparison to her neighbors, owing to abundant land, inter-regional trade and ].<ref name=Piskorski54>Piskorski (1999), p.54</ref> | |||

| Wartislaw's power and standing differed depending on the area. In the east of his duchy (], ], and ] area) his power was strongest, tribal assemblies are not documented. In the center (Wolin, Szczecin, and Pyrzyce area) Wartislaw had to yield the decisions of the local population and nobility. In the towns, Wartislaw maintained small courts. Every decision of Wartislaw had to pass an assembly of the elders and an assembly of the free. In the newly gained Lutici territories of the West, Wartislaw managed to establish a rule that resembled his rule in the eastern parts, but also negotiated with the nobility.<ref name=Piskorski5051>Piskorski (1999), pp.50,51</ref> | |||

| ==Otto of Bamberg's second mission (1128)== | |||

| {{Main|Conversion of Pomerania|Otto von Bamberg}} | |||

| ], depicted in ]'s ] Memorial Church]] | ], depicted in ]'s ] Memorial Church]] | ||

| Otto of Bamberg returned in 1128,<ref name="Palmer, P.107ff"/> this time invited by duke Wartislaw himself, aided by the emperor Holy Roman Emperor Lothair III, to convert the Slavs of Western Pomerania just incorporated into the Pomeranian duchy, and to strengthen the Christian faith of the inhabitants of Szczecin and Wolin, who fell back into heathen practices and idolatry.<ref name="Herrmann, pp.402ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.402ff</ref><ref name=Piskorski40>Piskorski (1999), p.40</ref> Otto this time visited primarily ]n burghs, had the temples of ] and ] torn down and on their sites erected the predecessors of today's ''St Nikolai'' and ''St Petri'' churches, respectively, before turning to ], Wolin and Szczecin.<ref name=Piskorski40/> The nobility assembled to a congress in ],<ref name=Piskorski40/> where they accepted Christianity on June 10, 1128.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/><ref name="Herrmann, pp.402ff"/><ref name="Buchholz p.26">Buchholz (1999), p.26</ref> Otto then was titled ''apostolus gentis Pomeranorum'', made a ] by pope ] in 1189, and was worshiped in Pomerania even after the ].<ref name="Buchholz p.28">Buchholz (1999), p.28</ref> | Otto of Bamberg returned in 1128,<ref name="Palmer, P.107ff"/> this time invited by duke Wartislaw himself, aided by the emperor Holy Roman Emperor Lothair III, to convert the Slavs of Western Pomerania just incorporated into the Pomeranian duchy, and to strengthen the Christian faith of the inhabitants of Szczecin and Wolin, who fell back into heathen practices and idolatry.<ref name="Herrmann, pp.402ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.402ff</ref><ref name=Piskorski40>Piskorski (1999), p.40</ref> Otto this time visited primarily ]n burghs, had the temples of ] and ] torn down and on their sites erected the predecessors of today's ''St Nikolai'' and ''St Petri'' churches, respectively, before turning to ], Wolin and Szczecin.<ref name=Piskorski40/> The nobility assembled to a congress in ],<ref name=Piskorski40/> where they accepted Christianity on June 10, 1128.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/><ref name="Herrmann, pp.402ff"/><ref name="Buchholz p.26">Buchholz (1999), p.26</ref> Otto then was titled ''apostolus gentis Pomeranorum'', made a ] by pope ] in 1189, and was worshiped in Pomerania even after the ].<ref name="Buchholz p.28">Buchholz (1999), p.28</ref> | ||

| Holy Roman Emperor Lothair claimed the areas west of the ] for his empire. Thus the terms of Otto's second mission were not negotiated with ], but with Lothar and Wartislaw.{{ |

Holy Roman Emperor Lothair claimed the areas west of the ] for his empire. Thus the terms of Otto's second mission were not negotiated with ], but with Lothar and Wartislaw.{{citation needed|date=February 2013}} However Lothair terminated the mission in the fall of 1128, probably because he distrusted Otto's contacts with Boleslaw. Otto visited ] on his way back to ].<ref name=Piskorski40/> | ||

| ], the later Pomeranian bishop, participated in Otto's mission as an interpreter and assistant.<ref name="Buchholz p.29"/><ref name=Piskorski47>Piskorski (1999), p.47</ref> | ], the later Pomeranian bishop, participated in Otto's mission as an interpreter and assistant.<ref name="Buchholz p.29"/><ref name=Piskorski47>Piskorski (1999), p.47</ref> | ||

| Fate of the pagan priesthood | |||

| The priests of the numerous gods |

The priests of the numerous gods worshipped before the conversion were one of the most powerful class in the early medieval society. Their reaction to the ] was ambiguous: In 1122, they saved missionary Bernhard's life by declaring him insane, otherwise he would have been killed in Wolin. On the other hand, Otto of Bamberg's mission was a far larger threat to the established pagan tradition, and eventually it succeeded in Christianization of the region. There are reports of unsuccessful assassination attempts made against Otto of Bamberg by the pagan priesthood. Following Otto's success, some of the pagan priests were ], while it is unknown what happened to the others. It has been speculated that they adapted to the new reality.<ref name=Piskorski47/> | ||

| == Pomeranian |

=== Pomeranian diocese (1140) === | ||

| In 1134, Pomeranian troops invaded Denmark and even looted ], then the Danish capital.<ref name=Piskorski44/> In 1135, Norwegian ] was attacked and sacked.<ref name=Piskorski44/> | |||

| == Pomeranian diocese (1140) == | |||

| ] (Wolin)]] | ] (Wolin)]] | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| {{Main|Roman Catholic Diocese of Kammin}} | {{Main article|Roman Catholic Diocese of Kammin}} | ||

| On Otto of Bamberg's behalf, a ] was founded with the see in ] (''Julin'', ''Jumne'', '']''),<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/> a major Slavic and Viking town in the ] estituary. On October 14, 1140, ] was made the first ] by ].<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/> Otto however had died the year before.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/> There was a rivalry between Otto's ], the ] and the ] for the incorporation of Pomerania. Pope Innocence II solved the dispute by repelling their claims and placed the new diocese directly under his ]. The see of the diocese was the church of ''St Adalbert'' in ].<ref name="Buchholz p.29">Buchholz (1999), p.29</ref> The diocese had no clear-cut borders in the beginning, but roughly reached from the ] burgh in the West to the ] in the East. In the South, it comprised the northern parts of ] and ]. As such, it was shaped after the territory held by ].<ref name="Buchholz p.29"/> | On Otto of Bamberg's behalf, a ] was founded with the see in ] (''Julin'', ''Jumne'', '']''),<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/> a major Slavic and Viking town in the ] estituary. On October 14, 1140, ] was made the first ] by ].<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/> Otto however had died the year before.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/> There was a rivalry between Otto's ], the ] and the ] for the incorporation of Pomerania. Pope Innocence II solved the dispute by repelling their claims and placed the new diocese directly under his ]. The see of the diocese was the church of ''St Adalbert'' in ].<ref name="Buchholz p.29">Buchholz (1999), p.29</ref> The diocese had no clear-cut borders in the beginning, but roughly reached from the ] burgh in the West to the ] in the East. In the South, it comprised the northern parts of ] and ]. As such, it was shaped after the territory held by ].<ref name="Buchholz p.29"/> | ||

| After ongoing Danish raids, Wollin was destroyed, and the see of the diocese was shifted across the |

After ongoing Danish raids, Wollin was destroyed, and the see of the diocese was shifted across the ] to Kamień Pomorski's ''St John's'' church in 1176. This was confirmed by the pope in 1186. In the early 13th century, the Cammin diocese along with the Pomeranian dukes gained control over Circipania. Also, the bishops managed to gain direct control over a territory around Kolobrzeg and ]. | ||

| The Pomerelian areas were integrated into the ]n ]. | The Pomerelian areas were integrated into the ]n ]. | ||

| After the successful conversion of the nobility, monasteries were set up on vast areas granted by local dukes both to further implement Christian faith and to develop the land. The monasteries actively took part in the ].<ref name="Herrmann, pp.402ff"/><ref name=Piskorski56>Piskorski (1999), p.56</ref> Most of the clergy originated in Germany, some in Poland, and since the mid-12th century also from Denmark.<ref name=Piskorski5455>Piskorski (1999), pp.54,55</ref> | |||

| == Wendish Crusade (1147) == | |||

| === Wendish Crusade (1147) === | |||

| {{Main article|Wendish Crusade}} | |||

| In 1147, the ], a campaign of the ], was mounted by bishops and nobles of the Holy Roman Empire and Poland.<ref name="Piskowski43"/> The crusaders ravaged the land and laid siege to ] and ] despite them (officially) being already Christian. Wollin's bishop ] took part in the negotiations that finally led to the lifting of the Stettin siege by the crusaders. ], went to the ] in ] the following year, where he swore to be a Christian.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/><ref name="Buchholz p.31">Buchholz (1999), p.31</ref><ref name="Herrmann, pp.388ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.388ff</ref> | In 1147, the ], a campaign of the ], was mounted by bishops and nobles of the Holy Roman Empire and Poland.<ref name="Piskowski43"/> The crusaders ravaged the land and laid siege to ] and ] despite them (officially) being already Christian. Wollin's bishop ] took part in the negotiations that finally led to the lifting of the Stettin siege by the crusaders. ], went to the ] in ] the following year, where he swore to be a Christian.<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/><ref name="Buchholz p.31">Buchholz (1999), p.31</ref><ref name="Herrmann, pp.388ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.388ff</ref> | ||

| Line 153: | Line 84: | ||

| {{Further|Partitions of the Duchy of Pomerania}} | {{Further|Partitions of the Duchy of Pomerania}} | ||

| ] died between 1134 and 1148. His brother ], duke in the ], ruled in place of Wartislaw's sons, ] and ] until his death in about 1155. Then the duchy was split into Pomerania-Demmin, ruled by Casimir, including the upper ], ], ] and ] areas, and Pomerania-Stettin, ruled by Bogislaw, including the lower ], ], ], and ] areas. The ] area was ruled in common as a codominion.<ref>Piskorski (1999), pp.41,42</ref> | ] died between 1134 and 1148. His brother ], duke in the ], ruled in place of Wartislaw's sons, ] and ] until his death in about 1155. Then the duchy was split into Pomerania-Demmin, ruled by Casimir, including the upper ], ], ] and ] areas, and Pomerania-Stettin, ruled by Bogislaw, including the lower ], ], ], and ] areas. The ] area was ruled in common as a codominion.<ref>Piskorski (1999), pp.41,42</ref> | ||

| == Westward expansion of Wartislaw I == | |||

| ] to ] and east of the ] to subjugate the Slavic ], in 1121.<ref name="Michalek">{{cite book | title=Słowianie Zachodni. Monarchie wczesnofeudalne | publisher=Bellona | author=Andrzej Michałek | year=2007 | pages=102 | isbn=978-83-11-10737-3}}</ref>]] | |||

| In the meantime, Wartislaw managed to conquer territories west of the ] river, an area inhabited by ] tribes weakened by past warfare, and included these territories into his ''Duchy of Pomerania''. Already in 1120, he had expanded west into the areas near the ] and ] river. Most notably ], the ] and ] were conquered in the following years.<ref name="Herrmann, pp.386"/> | |||

| The major stage of the westward expansion into Lutici territory occurred between Otto of Bamberg's two missions, 1124 and 1128. In 1128, Demmin, the County of Gützkow and Wolgast were already incorporated into Wartislaw I's realm, yet warfare was still going on.<ref name=Piskorski4041>Piskorski (1999), pp. 40,41</ref> Captured Lutici and other war loot, including livestock, money, and clothes were apportioned among the victorious.<ref name=Herrmann141>Herrmann (1985), p.141</ref> After Wartislaw's Lutician conquests, his duchy lay between the ] to the north, ], including ], to the west, Kolberg/Kołobrzeg in the east, and possibly as far as the ] and ] rivers in the south.<ref name=Piskorski41>Piskorski (1999), p.41</ref> | |||

| After the conquests, Wartislaw's realm stretched from the ] in the North and ] with ] in the West to the ] and possibly also the ] rivers in the South and the Kolobrzeg area in the east.<ref name=Piskorski41/> | |||

| These gains were not subject to Polish over lordship,<ref name=Inachim17/><ref name=Buske11/> but were placed under over lordship of ] ] ], who according to Bialecki was a dedicated enemy of Slavs,<ref>Historia Szczecina: | |||

| zarys dziejów miasta od czasów najdawniejszych do 1980, Tadeusz Białecki, page 53 Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1992 -</ref> by ].<ref name=Inachim17/> Thus, the western territories contributed to making Wartislaw significantly independent from the Polish dukes.<ref>Buske (1997), p.11 :"Durch die Eroberung des Peenegebiets, das nicht zum polnischen Einflußgebiet gehörte, gewann Wartislaw eine beachtliche Selbstständigkeit. Er konnte sich schließlich dauerhaft gegen Polen behaupten "</ref> Wartislaw was not the only one campaigning in these areas. The Polish duke Boleslaw III, during his Pomeranian campaign launched an expedition into the ] area in 1120/21,<ref name=Buske10/> before he turned back to subdue Wartislaw. The later ] Lothair III (then ] Lothair I of Supplinburg) in 1114 initiated large scale campaigns against the local Lutici tribes resulting in their final defeat in 1228.<ref name=Buske10>Buske (1997), p.10</ref>{{clarify|date=February 2011}} Also, the territories were invaded by Danish forces multiple times, who, coming from the ], used the rivers Peene and ] to advance to a line ]–].<ref name=Buske11>Buske (1997), p.11</ref> At different times, Pomeranians, Saxons and Danes were either allies or opponents.<ref name=Buske11/> The ] consolidated their power in the course of the 12th century, yet the preceding warfare had left these territories completely devastated.<ref name=Buske1112>Buske (1997), pp.11,12</ref> | |||

| == Society under Wartislaw I == | |||

| During Wartislaw I's rule society was composed of the Pomeranian freeman and the slaves, who consisted mostly of Wendish, German or Danish war captives. The freemen generally made their living from agriculture, fishing and husbandry, as well as hunting and trade.<ref name=Herrmann141/><ref name=Piskorski5154/> Their social status depended both on accumulated wealth as well as noble status. The proportion of slaves in the total population of the area was relatively small and in fact the Pomeranians exported slaves to Poland.<ref name=Herrmann141/><ref name=Piskorski5154>Piskorski (1999), pp.51,54</ref> | |||

| The largest settlements were Wollin (Wolin) and Stettin (Szczecin), each of which had a few thousand inhabitants, and a biweekly market day.<ref name=Piskorski54/> While some historians address these settlements as towns, this is rejected by others due to the differences to later towns. They are usually referred to as early towns, proto-towns, ]s or emporia; their Slavic designation was ''*grod'' (] in ] and ]).<ref group=nb name=A>In German historiography, larger pre-Ostsiedlung settlements comprising castles and suburbia are usually termed ''Burgstadt'' (lit. "castle town"), in contrast to the earlier emporia (''Seehandelsplätze'') at the Baltic coast and the later ''Rechtsstadt'' (lit. "law town") or communal town; both ''Burgstadt'' and emporia are also described as ''Frühstadt'' (lit. "early town"). The contemporary Slavic cognate of Burgstadt was ''*]'' ] and ]: ''gard'', it resembled the contemporary West European ''vicus'' and ''villa'' in structure and layout, but not the West European ''civitas'' markets. In Slavic-speaking regions, Ostsiedlung narrowed the meaning of ''*grod'' to denote the castles only, while towns were termed ''*město'' (orig. "site", ; in areas not affected by Ostsiedlung, towns were termed ''*grod'', cf. Russian ''город''). {{cite book|last=Brather|first=Sebastian|title=Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa|publisher=de Gruyter|year=2001|isbn=3-11-017061-2|pages=141f., 148, 154–155}} ] lacked a dedicated term for the ''Burgstadt'' settlements, contemporary documents refer to them as ''civitates, oppida'' or ''urbes'' {{cite journal|last=Brachmann|first=Hansjürgen|title=Von der Burg zur Stadt. Die Frühstadt in Ostmitteleuropa|year=1995|journal=Archaeologia Historica|volume=20|pages=315–321; 315}} Schich (2007) rejected a proposal of Stoob (1986) to discontinue the use of compound words including "town" for these places, such as ''Protostadt'' (lit. "proto town"), ''Burgstadt'', ''Frühstadt'' and Stoob's own, earlier proposal ''Grodstadt'' (lit. "grod town"). Stoob says that this would unjustifiably suggest a relation to the high medieval towns. Schich says that "if - despite the undisputable break in the 'urban' development in this area - terms like ''Burgstadt'' and ''Frühstadt'' are used here, then this is based on a broader understanding of the term 'town.' ''Frühstadt'' then denotes an early form of town-like settlements preceding the high medieval towns, without insinuating an evolution from ''Burgstadt'' or ''Frühstadt'' to the communal town." {{cite book|last=Schich|first=Winfried|title=Wirtschaft und Kulturlandschaft|editor1-first=Winfried|editor1-last=Schich|editor2-first=Peter|editor2-last=Neumeister|publisher=BWV Verlag|year=2007|isbn=978-3-8305-0378-1|page=266}} Cf. also Benl, R, in Buchholz (1999), p. 75.</ref> The population of Pomerania was relatively wealthy in comparison to her neighbors, owing to abundant land, inter-regional trade and ].<ref name=Piskorski54>Piskorski (1999), p.54</ref> | |||

| Wartislaw's power and standing differed depending on the area. In the east of his duchy (], ], and ] area) his power was strongest, tribal assemblies are not documented. In the center (Wolin, Szczecin, and Pyrzyce area) Wartislaw had to yield the decisions of the local population and nobility. In the towns, Wartislaw maintained small courts. Every decision of Wartislaw had to pass an assembly of the elders and an assembly of the free. In the newly gained Lutici territories of the West, Wartislaw managed to establish a rule that resembled his rule in the eastern parts, but also negotiated with the nobility.<ref name=Piskorski5051>Piskorski (1999), pp.50,51</ref> | |||

| == Pomeranian expeditions to Scandinavia == | |||

| In 1134, Pomeranian troops invaded Denmark and even looted ], then the Danish capital.<ref name=Piskorski44/> In 1135, Norwegian ] was attacked and sacked.<ref name=Piskorski44/> | |||

| == Saxon conquest (1164) == | == Saxon conquest (1164) == | ||

| {{Main|Battle of Verchen}} | {{Main article|Battle of Verchen}} | ||

| In the West, bishops and dukes of the ] mounted expeditions to Pomerania. Most notable for the further fate of Pomerania are the 1147 ] and the 1164 ], the Pomeranian dukes became vassals of ], ].<ref name="Piskowski43"/> ] came under control of the Pomeranian dukes at about this time. Despite this vassalage, Henry again sieged Demmin in 1177 when he allied with the Danes, but reconciled with the Pomeranian dukes thereafter.<ref name="Buchholz pp.30,34">Buchholz (1999), pp.30,34</ref> | In the West, bishops and dukes of the ] mounted expeditions to Pomerania. Most notable for the further fate of Pomerania are the 1147 ] and the 1164 ], the Pomeranian dukes became vassals of ], ].<ref name="Piskowski43"/> ] came under control of the Pomeranian dukes at about this time. Despite this vassalage, Henry again sieged Demmin in 1177 when he allied with the Danes, but reconciled with the Pomeranian dukes thereafter.<ref name="Buchholz pp.30,34">Buchholz (1999), pp.30,34</ref> | ||

| Line 164: | Line 116: | ||

| After the 1147 ] and the 1164 ], the duchy (at least the western parts) had joined ]'s ]. Following internal struggles, Henry fell against ] Frederick ] in 1181. ] took his duchy as a fief directly from Barbarossa in the same year.<ref name="Piskorski44"/><ref name="Buchholz p.34">Buchholz (1999), p.34</ref> | After the 1147 ] and the 1164 ], the duchy (at least the western parts) had joined ]'s ]. Following internal struggles, Henry fell against ] Frederick ] in 1181. ] took his duchy as a fief directly from Barbarossa in the same year.<ref name="Piskorski44"/><ref name="Buchholz p.34">Buchholz (1999), p.34</ref> | ||

| At that time, the duchy was also referred to as ] ({{ |

At that time, the duchy was also referred to as ] ({{langx|de|Slawien}}) (yet this was a term applied to several ] areas such as ] and the Principality of Rügen). The duchy remained in the Empire, although Denmark managed to take control of the southern Baltic including the Duchy of Pomerania from the 1180s until the 1227 ]. | ||

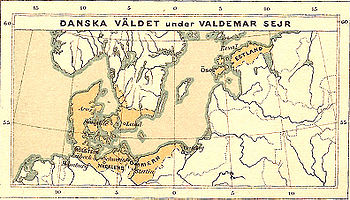

| == Danish conquests (1168–1185) == | == Danish conquests (1168–1185) == | ||

| From the North, Denmark attacked Pomerania. Several campaigns throughout the 12th century (in 1136, 1150, 1159 and throughout the 1160s) culminated in the defeat of the ] in 1168.<ref name="Herrmann, pp.394ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.394ff</ref> | From the North, Denmark attacked Pomerania. Several campaigns throughout the 12th century (in 1136, 1150, 1159 and throughout the 1160s) culminated in the defeat of the ] in 1168.<ref name="Herrmann, pp.394ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.394ff</ref> | ||

| Line 173: | Line 124: | ||

| ] topples the god ] at ], by ]]] | ] topples the god ] at ], by ]]] | ||

| ], 13th century]] | ], 13th century]] | ||

| {{Main|Principality of Rügen|Absalon}} | {{Main article|Principality of Rügen|Absalon}} | ||

| The island of ] and the surrounding areas between the ], ] and ] rivers were the settlement area of the West Slavic ]. After Otto von Bamberg's mission, only the ] ] remained pagan. This was changed by a Danish expedition of 1168, launched by ] and ], ] of |

The island of ] and the surrounding areas between the ], ] and ] rivers were the settlement area of the West Slavic ]. After Otto von Bamberg's mission, only the ] ] remained pagan. This was changed by a Danish ], launched by ] and ], ].<ref name="Realenzyklopedie p.40ff"/> The Danish success in this expedition ended a series of conflicts between Denmark and Rügen. The Rügen princes, starting with ], became vassals of Denmark,<ref name="Piskowski43">Piskorski (1999), p.43</ref><ref name="Buchholz p.34"/> and the principality would be Denmark's bridgehead on the southern shore of the Baltic for the next centuries. The 1168 expedition was decided when after a Danish siege of the ] of ], a fire broke out leaving the defendants unable to further withstand the siege. Since Arkona was the major temple of the superior god ] and therefore crucial for the powerful clerics, the Rani surrendered their other strongholds and temples without further fighting. ] had the Rani hand out and burn the wooden statues of their gods and integrated Rügen in the ]. The mainland of the Rügen principality was integrated into the ]. | ||

| === Danish conquest of all Pomerania (1170–1185) === | === Danish conquest of all Pomerania (1170–1185) === | ||

| Line 184: | Line 135: | ||

| In the fall of 1170, the Danes raided the ] estituary. In 1171, the Danes raided ] and took Cotimar's burgh in ]. In 1173, the Danes turned to the ] again, taking the burgh of ]. ], castellan of Stettin, became a Danish vassal. In 1177, the Danes again raided the Oder Lagoon area, also the burgh of ] in 1178.<ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35"/> | In the fall of 1170, the Danes raided the ] estituary. In 1171, the Danes raided ] and took Cotimar's burgh in ]. In 1173, the Danes turned to the ] again, taking the burgh of ]. ], castellan of Stettin, became a Danish vassal. In 1177, the Danes again raided the Oder Lagoon area, also the burgh of ] in 1178.<ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35"/> | ||

| In 1184, ] led the Pomeranian navy towards ]. On emperor ]'s initiative, Bogislaw was to take the ] from the Danes, whose king ] had refused him the oath of fealty. Though superior in numbers, the Pomeranian navy was utterly defeated by the Danish navy led by ] near ] island in the ].<ref name=Piskorski44>Piskorski (1999), p.44</ref> | In 1184, ] led the Pomeranian navy towards ]. On emperor ]'s initiative, Bogislaw was to take the ] from the Danes, whose king ] had refused him the oath of fealty. Though superior in numbers, the Pomeranian navy was utterly defeated by the Danish navy led by ] near ] island in the ].<ref name=Piskorski44>Piskorski (1999), p.44</ref> | ||

| In 1184 and 1185, three campaigns of the Danes resulted in making ] a Danish vassal. These campaigns were mounted by Valdemar's son and successor for the Danish throne, ]. In the ] the Danish period lasted until ] lost the ] on 22 July 1227. Danish supremacy prevailed until 1325<ref name="Herrmann, pp.394ff"/> in the Rugian principality.<ref name=Piskorski44/><ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35">Buchholz (1999), pp.34,35</ref> During this time, the emperor formally renounced his claims on the southern ] in favour of Denmark.<ref name=Piskorski44/> | In 1184 and 1185, three campaigns of the Danes resulted in making ] a Danish vassal. These campaigns were mounted by Valdemar's son and successor for the Danish throne, ]. In the ] the Danish period lasted until ] lost the ] on 22 July 1227. Danish supremacy prevailed until 1325<ref name="Herrmann, pp.394ff"/> in the Rugian principality.<ref name=Piskorski44/><ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35">Buchholz (1999), pp.34,35</ref> During this time, the emperor formally renounced his claims on the southern ] in favour of Denmark.<ref name=Piskorski44/> | ||

| ===List of Danish campaigns=== | |||

| {|class=wikitable | |||

| !colspan="2"|Danish expeditions of into the ] and the ] | |||

| |- | |||

| !Date | |||

| !Destination, notes | |||

| |- | |||

| |1042–1047 | |||

| |Rügen, ] (destroyed 1043)<ref name=Heitz157/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1080–1086 | |||

| |Rügen<ref name=Heitz157/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1098 | |||

| |] (subdued)<ref name=Heitz157/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1129 or 1130 | |||

| |], Julin<ref name=Heitz162>Heitz (1995), p.162</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1136 | |||

| |Pomerania,<ref name="Herrmann, pp.394ff"/> Rügen (])<ref name=Heitz162/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1150 | |||

| |Pomerania<ref name="Herrmann, pp.394ff"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |summer of 1159 | |||

| |] and ]<ref name=Heitz163>Heitz (1995), p.163</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |fall of 1159 | |||

| |Rügen (])<ref name=Heitz163/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1160 | |||

| |Pomerania, with support of the ] and ]<ref name=Heitz163/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |spring of 1162 | |||

| |], defeat of Pomeranian forces, Danes carry off Pomeranian hostages<ref name=Heitz163/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |July 1164 | |||

| |] and Pomerania, together with ] who defeats the ] in the ]<ref name=Heitz164>Heitz (1995), p.164</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |fall of 1164 | |||

| |Rügen, devastation of the coastline<ref name=Heitz164/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |April/May 1165 | |||

| |Rügen (], ], ]), also Pomeranian-claimed territory (] devastated)<ref name=Heitz164/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |fall of 1165 | |||

| |Rügen (], ], ])<ref name=Heitz164/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |March/April 1166 | |||

| |]<ref name=Heitz165>Heitz (1995), p.165</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |May 1166 | |||

| |], "Ostrozne" (thought to be ]). ] protests that ] attacked his vassal, ].<ref name=Heitz165/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |September/October 1166 | |||

| |], ], ]<ref name=Heitz165/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |June 1168 | |||

| |Rügen, ] defeated, Rügen becomes Danish principality. In 1169, Valdemar pledges allegiance to ] (Barbarossa), and in turn is permitted to campaign in Pomerania as he likes.<ref name=Heitz165/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |fall of 1170 | |||

| |] and ],<ref name=Heitz165/> ] estuary<ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1171 | |||

| |] (in May),<ref name=Heitz165/> ]<ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1173 | |||

| |"Gorgasia", ], ], ], ]. Poland sends relief forces to besieged Bogislaw in Stettin,<ref name=Heitz165/> Denmark nevertheless sacks the burgh, the castellan becomes a Danish vassal.<ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1174 | |||

| |Danish preparations for a further campaign fail, two-year peace settlement with the ]<ref name=Heitz166>Heitz (1995), p.166</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |June 1177 | |||

| |Valdemar demands that ] campaigns in Pomerania, Henry besieges ] for 10 weeks<ref name=Heitz166/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1177 | |||

| |], ], ], supported by ].<ref name=Heitz166/> ] area.<ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1178 | |||

| |"Ostrozno" (thought to be ], in the spring),<ref name=Heitz166/> ]<ref name="Buchholz pp.34,35"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |spring of 1184 | |||

| |On demand of ] (Barbarossa), his vassal ], mounts a naval attack against Danish vassal ], to punish Valdemar's son Kanut for not pledging allegiance to the emperor. Utter defeat of the Pomeranian navy in the ].<ref name=Heitz167>Heitz (1995), p.167</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |summer of 1184 | |||

| |] and ] (unsuccessful), ] (destroyed)<ref name=Heitz167/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |after 22 September 1184 | |||

| |Pomerania<ref name=Heitz167/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |late 1184 | |||

| |]<ref name=Heitz167/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |April/May 1185 | |||

| |], ], ].<ref name=Heitz168>Heitz (1995), p.168</ref>], pledges allegiance to ].<ref name=Heitz167/><ref name=Heitz168/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1189 | |||

| |]<ref name=Heitz168/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1198–1199 | |||

| |Danish and ] forces under ] fight against each other in ], the ], and the ] area. ] gets destroyed.<ref name=Heitz168/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |(1214) | |||

| |] renounces his claims to the areas east of the ] and ] rivers (including Rügen and Pomerania) in favour of Denmark<ref name=Heitz169>Heitz (1995), p.169</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |(1227) | |||

| |Utter Danish defeat in the ], end of Danish rule in Pomerania, principality of Rügen remains with Denmark.<ref name=Heitz170>Heitz (1995), p.170</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1228 | |||

| |Pomeranians attack and sack Danish-held ]<ref name=Heitz170/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1233 | |||

| |] sacked by ]<ref name=Heitz170/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |1234 | |||

| |] and ] attack and sack Danish-held ]<ref name=Heitz170/> | |||

| |} | |||

| == Foundation of monasteries == | |||

| After the successful conversion of the nobility, monasteries were set up on vast areas granted by local dukes both to further implement Christian faith and to develop the land. The monasteries actively took part in the ].<ref name="Herrmann, pp.402ff"/><ref name=Piskorski56>Piskorski (1999), p.56</ref> Most of the clergy originated in Germany, some in Poland, and since the mid-12th century also from Denmark.<ref name=Piskorski5455>Piskorski (1999), pp.54,55</ref> | |||

| {| width = "95%" | |||

| | width = "50%"| | |||

| === ] === | |||

| *] (1153 by ], since 1304 Cistercian<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/>) near ] | |||

| *] (1172)<ref name=Piskorski50>Piskorski (1999), p.50</ref> in ] near the ducal residence ], later town of ] | |||

| *] (1173)<ref name=Piskorski50/> | |||

| *] (1186) (now part of nearby ] (Gdańsk)) | |||

| *] (1193)<ref name=Piskorski50/> in the center of ], near the Ranis' former main burgh ] and just besides the residence of the ], ]. | |||

| *] (1198/99)<ref name=Piskorski50/> (now part of nearby ]) | |||

| *] (1231)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> (1243) | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> (1248) | |||

| *] (1252/1260<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/>) near ] | |||

| *] (1260, later moved to ]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/>) | |||

| *] Marienstift (1261)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> (1278) | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> (1289) on the ] isle | |||

| *] (1296)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (1304), south of ] | |||

| *] Ottenstift (1346)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| === ] === | |||

| * Grobe, Pudagla, or ] (1155), near ] on the isle of ] | |||

| *] near the old Liutizian main temple site and capital, ] and the later town of ] | |||

| *] in the center of the ] near the Ukrani burgh ] and the town of ] | |||

| *] (1224) near ]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| |width="50%"| | |||

| === ] === | |||

| ] (Eldena, ], founded in 1199) by ] ] monks]] | |||

| *] (1251)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100">Buchholz (1999), pp.98-100</ref> | |||

| *] (1295)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] Schwarzes Kloster ("Black Abbey") (1254)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (1272)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (1278)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| === ] === | |||

| *] (1240)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (before 1250)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (1254)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] Graues Kloster ("Grey Abbey", donated by the ], now ]) (1262)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| === ] === | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (13th century)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (13th century)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (1276)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (14th century)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] (14th century) near ]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *] - (now Jasienica) near ] (now in ]) | |||

| === ] === | |||

| *] (between 1191 and 1194)<ref name=Piskorski50/> | |||

| *] (1253–1304)<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| *]<ref name="Buchholz pp.98-100"/> | |||

| |} | |||

| == Society in the late 12th and early 13th centuries == | == Society in the late 12th and early 13th centuries == | ||

| While in the early 12th century most of the Pomeranians were free, by the late 12th century only the nobility and knights remained free. They were free in their decisions concerning their property and actions, though formally they had to apply for the duke's support.<ref name=Piskorski55>Piskorski (1999), p.55</ref> | While in the early 12th century most of the Pomeranians were free, by the late 12th century only the nobility and knights remained free. They were free in their decisions concerning their property and actions, though formally they had to apply for the duke's support.<ref name=Piskorski55>Piskorski (1999), p.55</ref> | ||

| The class of the unfree still consisted of prisoners of war, but additionally one became unfree after conviction of a major criminal offense or if one was unable to pay one's |

The class of the unfree still consisted of prisoners of war, but additionally one became unfree after conviction of a major criminal offense or if one was unable to pay one's debts. The unfree made up for an estimated 15% of the population and primarily had to work on the lands of the free.<ref name=Piskorski55/> | ||

| Most of the population of this time was largely dependent on the duke. This dependency |

Most of the population of this time was largely dependent on the duke. This dependency could also result in becoming dependent on a person other than the duke, if the duke granted parts of his lands including the population thereon to a noble, a church, or a monastery. This class shared certain obligations and restrictions with the unfree, for example a ], and a restricted right to marry.<ref name=Piskorski55/> | ||

| Their major obligations were participation in the duke's military campaigns, defense of the duchy, erection and maintenance of the ducal buildings (burghs, courts, bridges), to hand over horses, oxen, and carriages to the duke or his officials on demand, to host and to cater the duke or his officials on demand, to supply rations for the duke's journeys, a periodic tribute in form of a fixed amount of meat and wheat, and also a church tax ("''biskopownica''", since 1170 "''Garbenzehnt''").<ref name=Piskorski56/> | Their major obligations were participation in the duke's military campaigns, defense of the duchy, erection and maintenance of the ducal buildings (burghs, courts, bridges), to hand over horses, oxen, and carriages to the duke or his officials on demand, to host and to cater the duke or his officials on demand, to supply rations for the duke's journeys, a periodic tribute in form of a fixed amount of meat and wheat, and also a church tax ("''biskopownica''", since 1170 "''Garbenzehnt''").<ref name=Piskorski56/> | ||

| == |

==German settlement== | ||

| {{Further|Ostsiedlung}} | {{Further|Ostsiedlung}} | ||

| ] illustrated in the ]. The man with the hat is the '']'', who recruited the settlers (right) for the landlord (left) and oversaw the construction of the town or village in turn for an elevated administrative position.]] | ] illustrated in the ]. The man with the hat is the '']'', who recruited the settlers (right) for the landlord (left) and oversaw the construction of the town or village in turn for an elevated administrative position.]] | ||

| Line 399: | Line 157: | ||

| === Rural settlement === | === Rural settlement === | ||

| Before the Ostsiedlung, Pomerania was rather sparsely settled. Around 1200, a relatively dense population could be found on the islands of ], ] and ]/Wolin, around the gards of ]/Szczecin, ]/Koszalin, ]/Pyrzyce (''Pyritzer Weizacker'') and ], around the ]/Parsęta river (]/Kołobrzeg area), the lower ] river, and between ] and the ] valley. Largely unsettled were the hilly regions and the woods in the South. The 12th century warfare, especially the Danish raids, depopulated many areas of Pomerania and caused severe population drops in others (e.g. Usedom). At the turn to the 13th century, only isolated German settlements existed, e.g. ] and other German villages, and the merchant's settlement near the Stettin castle. In contrast, the monasteries were almost exclusively run by Germans and Danes.<ref name="Buchholz pp.43-48">Buchholz (1999), pp.43-48</ref> | |||

| {{undue|section|date=February 2011}} | |||

| Before the Ostsiedlung, Pomerania was rather sparsely settled. Around 1200, a relatively dense population could be found on the islands of ], ] and ]/Wolin, around the gards of ]/Szczecin, ]/Koszalin, ]/Pyrzyce (''Pyritzer Weizacker'') and ], around the ]/Parsęta river (]/Kołobrzeg area), the lower ] river, and between ] and the ] valley. Largely unsettled were the hilly regions and the woods in the South. The 12th century warfare, especially the Danish raids, depopulated many areas of Pomerania and caused severe population drops in others (e.g. Usedom). At the turn to the 13th century, only isolated German settlements existed, e.g. ] and other German villages, and the merchant's settlement near the Stettin castle. In contrast, the monasteries were almost exclusively run by Germans and Danes.<ref name="Buchholz pp.43-48">Buchholz (1999), pp.43-48</ref> | |||

| The first German and Danish settlers arrived since the 1170s and settled in the ] area, the ], the ] area and southern Pomerania.<ref name=Piskorski77>Piskorski (1999), p.77</ref> | The first German and Danish settlers arrived since the 1170s and settled in the ] area, the ], the ] area and southern Pomerania.<ref name=Piskorski77>Piskorski (1999), p.77</ref> | ||

| Significant German settlement started in the first half of the 13th century. Ostsiedlung was a common process at this time in all Central Europe and was largely run by the nobles and monasteries to increase their income. Also, the settlers were expected to finish and secure the conversion of the non-nobles to Christianity. In addition, the Danes withdrew from most of Pomerania in 1227, leaving the duchy vulnerable to their expansive neighbors, especially ], ], and ].<ref name="Buchholz pp.46-52"/> | Significant German settlement started in the first half of the 13th century. Ostsiedlung was a common process at this time in all Central Europe and was largely run by the nobles and monasteries to increase their income. Also, the settlers were expected to finish and secure the conversion of the non-nobles to Christianity. In addition, the Danes withdrew from most of Pomerania in 1227, leaving the duchy vulnerable to their expansive neighbors, especially ], ], and ].<ref name="Buchholz pp.46-52">Buchholz (1999), pp.46-52</ref> | ||

| Besides the ] area, the last records of a Slavic language in the ] are from the 16th century: In the Oder area, a few Slavic fishing villages are recorded, and east of ] and ], a more numerous Slavic-speaking population must have existed, as can be concluded from a 1516 decree forbidding the use of the Slavic language at the ] market.<ref>Piskorski (2007), p.86</ref> | |||

| Germans, at this early stage (before 1240), were often settled in frontier regions, such as the mainland part of the ] (after ] granted ] the right to call in settlers in 1209), ], the lands of ] (administered semi-independently by Detlev of Gadebush), the ], the lands of ] and ] (which later was granted to the Knights Templar), and the area north of the ] and along the lower ] river. However, in many of these frontiers, German settlement did not hinder the advance of Pomerania's neighbors.<ref name="Buchholz pp.46-52">Buchholz (1999), pp.46-52</ref> | |||

| Germans were placed under a different law than Slavs. While those who were unfree (except for the nobles), did not own the soil they cultivated, and were to serve the nobility, the opposite was true for the Germans.<ref name="Buchholz p.45">Buchholz (1999), p.45</ref><ref name="Herrmann, p.422">Herrmann (1985), p. 422</ref> | |||

| About 1240, the areas of ] and ] were subject to German settlement. About 1250, large scale settlement took place also in Central Western Pomerania (], lands of ], ], ] and ]), and the ] area (where settlement was encouraged already since 1229). In the 1260s, settlement started in the ] area, and in the virtually unpopulated lands of ], ] and ]. The ] and the ] mouth areas were also settled at about 1260, but the ] and the woodlands on both sides of the ] remained untouched. In the areas adjacted to the ] (the lands of ] and ]) local Slavs participated in the German settlement which started in the 1260s. Settlement of the areas centered on the upper ] river, previously unsettled, started in the 1250s, and reached a peak in the 1280s. The lower Rega area around ] and ] was settled about the same period, but here a native Slavic population participated. In the ] area, first German settlements occurred about 1260, but a more extensive settlement did not start before 1280. On the islands of ] and ], only isolated settlement took place in the 13th century, e.g. in the ] and ] area, where Germans settled already in the 1240s, and in proximity of the German town of ]. The local ] did, in contrast to the other Pomeranian monasteries, not enhance German settlement. Therefore, Slavic culture on the isles persisted and vanished only in the late 14th century. The island of ], in contrast to the German mainland parts of the principality, also retained a Slavic character throughout the 13th century - German settlement would only start in the 14th century, with strong participation of local Slavs. In ], German settlement started in the 1260s, and was promoted by the ]. A large influx of settlers to the western parts of Schlawe-Stolp took place after 1270—first settlers were called to the ] area in the 1280s. Here, local Slavs participated in the Ostsiedlung, and settlement went on throughout the 14th century.<ref name="Buchholz pp.48-60">Buchholz (1999), pp.48-60</ref> | |||

| Initially, the Germans who settled the northern regions of the Pomeranian duchy predominantly came from ], while the Germans who settled the southern areas (''mittelpommerscher Keil'') predominantly came from ] and ]. This caused the emergence of different ]. German settlers also came from areas earlier affected by Ostsiedlung, such as ], ], and later also German settled regions of ] herself. The Slavic dialects disappeared, with the exception that fishermen from the isles and the Oder lagoon area continued to use Wendish for a relatively long period.<ref name="Buchholz pp.61-63">Buchholz (1999), pp.61-63</ref><ref>Piskorski (2007), pp.83ff</ref> | |||

| Besides the ] area, the last records of Slavic language in the ] are from the 16th century: In the Oder area, a few Slavic fishing villages are recorded, and east of ] and ], a more numerous Slavic-speaking population must have existed, as can be concluded from a 1516 decree forbidding the use of the Slavic language at the ] market.<ref>Piskorski (2007), p.86</ref> | |||

| Villages before the Ostsiedlung were of the '']'' type; the houses were built close to each other without a special ruling. A variant of this type also found in Pomerania is the ] (or ]) type, where a dead-end road leads to those houses. This type evolved as an extension of ''Haufendorf'' villages. German settlement introduced new types of villages: In the ] type, houses were built on both sides of a main road, each within its own ] ({{lang-de|Hagen}}). Those villages were usually set up after the clearance of woodlands; most of them were given German names in absence of any Slavic site names. This type of village can be found all along the coast, most of them in the areas between ] and ], ] and ], and north and west of ]. Other villages were built in the ] type, where a main street fork encloses a large meadow ("Anger") in the village's center where the livestock was kept at night; sometimes the church or other buildings not used for living were built on the Anger also. This type is the most prominent type in the ], lower ], ], ] and ] areas, and many villages of this type are also found in the ] and ] area. In addition to these types, the ] type, characterized by a single and very long main street, was introduced in a later stage of Ostsiedlung, and therefore is found predominantly in areas that were affected last by the German settlement (easternmost parts, Cammin area). Villages of this type were either new construction, or extensions of Slavic precursors. In other areas, Hagenhufendorf and Angerdorf types dominate, while the Haufendorf type used in Slavic times and its Sackdorf variant can still be found in between, predominantly on the islands.<ref name="Buchholz pp.63-65">Buchholz (1999), pp. 63–65</ref><ref name="Herrmann, pp.421ff"/><ref>without pointing out the specific areas also Piskorski (1999), pp. 83ff</ref> | |||

| The villages' area was divided in ]. The size of a hide differed between the village types: A ], used in the Hagenhufendorf villages, comprised 60 ] ({{lang-la|iugera}}), about 40 ]. A ], used in the Angerdorf villages, comprised 30 Morgen. One farm would usually have an area of one Hagenhufe or two Landhufen. Slavic farmland was measured in Haken ({{lang-la|uncus}}), with one Haken equaling 15 ] (half a Landhufe). Haken were used only in villages remaining under old Slavic law (predominantly on the islands), whereas Hufen were used for new villages placed under German law (in Pomerania sometimes referred to as ]). Not all families of German villages owned a Hufe. Those dwelling on considerably smaller property ("gardens") were usually hired as workers by the farmers ({{lang-de|Vollbauern}}). These people were termed "gardeners" ({{lang-de|Gärtner}}) or ] (literally "who sits in a hut"), and could either be local Slavs or the younger sons of German farmers who did not inherit their father's soil.<ref name="Herrmann, pp.421ff">Herrmann (1985), pp. 421ff</ref><ref name="Buchholz pp.66-70">Buchholz (1999), pp. 66–70</ref><ref>for ] also Piskorski (1999), p.85</ref> | |||

| In southern Pomerania, villages were larger than in the North (50 to 60 Hufen compared to 10 to 20 Hufen), also the farm size varied with a typical farm in the South (] area) being 2 to 3 Hufen and at the coast one Hufe.<ref>Piskorski (1999), p. 85</ref> | |||

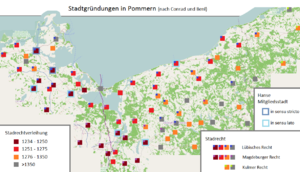

| === Foundation of towns === | === Foundation of towns === | ||

| Before the Ostsiedlung, urban settlements of the emporia{{clarify|date=October 2013}} and ]<ref group=nb name=A/> types existed, for example the city of ] (Stettin) which counted between 5,000 and 9,000 inhabitants,<ref>An historical geography of Europe, 450 B.C.-A.D.1330, Norman John Greville Pounds, Cambridge University Press 1973, page 241, "By 1121 Polish armies had penetrated its forests, captured its chief city of Szczecin"</ref><ref>Archeologia Polski, Volume 38, Instytut Historii Kultury Materialnej (Polska Akademia Nauk, page 309, Zakład im. Ossolińskich, 1993</ref> and other locations like ], ], ], Wollin/Wolin, Kolberg/Kołobrzeg, Pyritz/Pyrzyce and Stargard, though many of the coastal ones declined during the 12th century warfare.<ref name="Herrmann, pp.237ff, 244ff, 269ff">Herrmann (1985), pp.237ff, 244ff, 269ff</ref> Previous theories that urban development was "in its entirety" brought to areas such as Pomerania, Mecklenburg or Poland by Germans are now discarded, and studies show that these areas had already growing urban centres in process similar to Western Europe<ref>Dollinger, P. (1999): ''The German Hansa.'' Routledge. p. 16.</ref> These population centres were usually centered on a gard, which was a fortified castle which housed the ] as well as his staff and the ducal craftsmen. The surrounding town consisted of suburbs, inhabited by merchants, clergy and the higher nobles. According to Piskorski this portion usually included "markets, taverns, butcher shops, mints, which also exchanged coins, toll stations, abbeys, churches and the houses of nobles".<ref>Piskorski (1999), p. 55.</ref> | |||