| Revision as of 01:02, 17 August 2013 editJMyrleFuller (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users69,620 editsm →Notable performers← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:59, 22 February 2024 edit undoRodw (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers775,534 editsm Disambiguating links to Bob Moore (link changed to Bob Moore (musician)) using DisamAssist. | ||

| (468 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Music genre}} | |||

| {{About|the music genre|the record label|Outside Music|the jazz technique|Outside (jazz)}} | {{About|the music genre|the record label|Outside Music|the jazz technique|Outside (jazz)}} | ||

| {{Infobox music genre | |||

| |name=Outsider music | |||

| |color = black | |||

| |bgcolor = light grey | |||

| |stylistic_origins= | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |cultural_origins=1960s, United States | |||

| |instruments=Various | |||

| |popularity= | |||

| |derivatives= | |||

| |other_topics= | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Outsider music''' (from "]") is music created by ] or ] musicians. The term is usually applied to musicians who have little or no traditional musical experience, who exhibit ] qualities in their music, or who have ] or ]es. The term was popularized in the 1990s by journalist and ] DJ ].<ref name="Harperthesis">{{cite thesis |last=Harper |first=Adam |date=2014 |title=Lo-Fi Aesthetics in Popular Music Discourse |type=PDF |publisher=] |url=https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:cc84039c-3d30-484e-84b4-8535ba4a54f8/datastreams/THESIS01 |access-date=March 10, 2018 |pages=48, 190 }}{{Dead link|date=April 2020 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| '''Outsider music''', a term coined by ] in the mid-1990s, are songs and compositions by musicians who are not part of the ] who write songs that ignore standard musical or lyrical conventions, either because they have no formal training or because they disagree with formal rules. This type of music, which often lacks typical structure and is emotionally stark, has few outlets; performers or recordings are often promoted by word of mouth or through fan chat sites, usually among communities of music collectors and music connoisseurs. Outsider musicians usually have much "greater individual control over the final creative" product either because of a low budget or because of their "inability or unwillingness to cooperate" with modifications by a record label or producer.<ref name="autogenerated2"></ref> | |||

| Outsider musicians often overlap with ] artists, since their work is rarely captured in professional ]s. Examples include ], ], and ], who each became the subjects of ]s in the 2000s.{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=347}} | |||

| Very few outsider musicians ever attain anything resembling ]; the few that do generally are considered ]. This notwithstanding, there is a ] for outsider music, and such musicians often maintain a ]. | |||

| == |

==Etymology== | ||

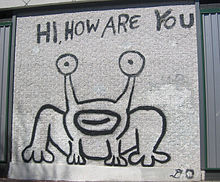

| ], by the outsider musician and visual artist ]]] | |||

| Pop music critic/popular culture writer Gina Vivinetto points out that outsider musicians include ], a "schizophrenic former street person from Chicago with dozens of records and a cult of loyal fans to his credit." She calls the clan of outsider musicians "an elite group," even "a group of geniuses," and she lists ] (]), ] (]) and ] (]).<ref name="autogenerated1"></ref> | |||

| The term "outsider music" is traced to the definitions of "]" and "]".<ref name="Encarnacao2016">{{cite book|last=Encarnacao|first=John|title=Punk Aesthetics and New Folk: Way Down the Old Plank Road|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VrYFDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA103|year=2016|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-317-07321-5|page=103}}</ref> "Outsider art" is rooted in the 1920s French concept of "L'Art Brut" ("raw art"). In 1972, academic ] introduced "outsider art" as the American counterpart of "L'Art Brut", which originally referred to work created exclusively by children or the mentally ill.<ref name="Plasketes2016"/> The word "outsider" began to be applied to music cultures as early as 1959, with respect to ],<ref>Charles Winick, "The Use of Drugs by Jazz Musicians", ''Social Problems'' 7, no. 3 (Winter 1959–1960): 240–53. Citation on 250.</ref> and to rock as early as 1979.<ref>Bernice Martin, "The Sacralization of Disorder: Symbolism in Rock Music", ''Sociological Analysis'' 40, no. 2 (Summer 1979): 87–124. Citation on 116.</ref> In the 1970s, "outsider music" was also a "favorite epithet" in music criticism in Europe.<ref>Zdenka Kapko-Foretić, "Kölnska škola avangarde", ''Zvuk: Jugoslavenska muzička revija'', 1980 no. 2:50–55. Citation on 54.</ref> By the 1980s and 1990s, "outsider" was common in the cultural lexicon and was synonymous with "self-taught", "untrained", and "primitive".<ref name="Plasketes2016"/> | |||

| There are some links between outsider music and ]: the emotional starkness, the lack of formal training and the humour. ] names ] as a major influence, Syd Barrett influenced antifolk's British strain, and there are similarities between the tuneless singing styles of Wesley Willis and ]. | |||

| ==Definition and scope== | |||

| The book '']: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music'' (2000), by music journalist and radio personality ], is a comprehensive guide to outsider music. The book profiles several relatively well known outsider musicians and gives a definition to the term. The book inspired two companion compilation CDs, sold separately. The guide claims that fans of outsider music are "fairly unusual," "inquisitive" types who have an "adventurous taste in music." While the guide does not "contend that Outsiders are "better" than their commercial counterparts", it does suggest that they may be more genuine, depending on how cynical a person is "about packaging and marketing as practiced by the music business", given that a "]per... is considered an authentic 'voice of the street'" even though they sell millions of albums. | |||

| Although outsider music has existed since before ], it was not until the advent of ] and music exchange networks that such a genre was recognized.<ref name="Misiroglu2015"/> Music journalist ] is credited with adapting "outsider art" for music in a 1996 article for the ] publication ''Pulse!''.<ref name="Plasketes2016">{{cite book|last=Plasketes|first=George|title=B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U203DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA43|year=2016|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-317-17113-3|page=43}}</ref> As a DJ on the New Jersey radio station ] in the 1980s, he had been an influential figure in ] scenes.<ref name="Harperthesis" /> In 2000, he authored a book titled '']'', which attempted to introduce and market outsider music as a genre.<ref name="Misiroglu2015"/> He summarized the concept thus: | |||

| The guide argues that music that is "exploited through conventional music channels" has "been revised, remodeled, and re-coifed; touched-up and tweaked; Photoshopped and focus-grouped" by the time it reaches the listener, to the point that it is "Music by Committee" that is "second-guessed" by a large team of record company staff. On the other hand, since outsider music has little target audience, so they are autonomous, and able to go through an "intensely solipsistic" process and create a singular artistic vision. Outsider artists have much "greater individual control over the final creative contour", either because of a low budget or because of their "inability or unwillingness to cooperate with or trust anyone but themselves." The guide notes that "our inability to fully comprehend the internal calculus of Outsider art... partly explains its charisma."<ref name="autogenerated2" /> | |||

| {{quote|... there are countless "unintentional renegades," performers who lack overt self-consciousness about their art. As far as they're concerned, what they're doing is "normal." And despite paltry incomes and dismal record sales, they're happy to be in the same line of work as ] and ]. ... Their vocals sound melodically adrift; their rhythms stumble. They seem harmonically without anchor. Their instrumental proficiency may come across as laughably incompetent. ... They get little or no commercial radio exposure, their followings are limited, and they have roughly the same likelihood of attaining mainstream success that a possum has of skittering safely across a six-lane freeway. ... The outsiders in this book, for the most part, lack self-awareness. They don't boldly break the rules, because they don't know there are rules.{{sfn|Chusid|2000}}}} | |||

| Outsider music includes various styles that cannot neatly be classified into other ], the ] guide describing it as "a nebulous category that encompasses the weird, the puzzling, the ill-conceived, the unclassifiable, the musical territory you never dreamed existed."<ref></ref> | |||

| As was common with journalists who championed musical ] in the 1980s,{{sfn|Harper|2014|pp=48, 53, 63–64}} Chusid considered outsiders more "]" than artists whose music is "exploited through conventional music channels" and "revised, remodeled, and re-coifed; touched-up and tweaked; Photoshopped and focus-grouped" by the time it reaches the listener, to the point that it is "Music by Committee". On the other hand, outsider artists have much "greater individual control over the final creative contour", either because of a low budget or because of their "inability or unwillingness to cooperate with or trust anyone but themselves."{{sfn|Chusid|2000}} | |||

| == Notable performers == | |||

| <!-- PLEASE NOTE: The persons in this list should have a Misplaced Pages article attached to them. If it redlinks, it will likely be removed.--> | |||

| Outsider musicians range from unskilled performers whose recordings are praised for their honesty, to the complex compositions of avant-garde groups. | |||

| Outsider music does not generally include ], ], ], or anything self-consciously ] or ]; Chusid uses the term "incorrect music" for music that is intentionally recorded to draw bad reactions, ] ], or from artists who are talented and self-aware enough not to produce such music but do so anyway. Works are usually sourced from ]s or independent ]s "with no quality control".<ref name="Misiroglu2015">{{cite book|editor-last=Misiroglu|editor-first=Gina|title=American Countercultures: An Encyclopedia of Nonconformists, Alternative Lifestyles, and Radical Ideas in U.S. History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=j4KsBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA541|year=2015|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-317-47729-7|pages=541–542}}</ref> In ''Songs in the Key of Z'', Chusid explicitly avoided discussing "unpopular", "uncommercial", or "underground" artists, and disqualified "just about anyone who could keep an orchestra or band together."{{sfn|Chusid|2000}} He did include a few acts in the definition that broke through to mainstream fame as novelty acts; ], for example, is included despite a consistent three-decade career in the music industry that included a major chart hit, ] was one of the United Kingdom's most influential and successful sound engineers of the 1960s, and the ] had ] in the 1960s with several national television appearances.{{sfn|Chusid|2000}} | |||

| ] (1901–1974) was a composer who built his own instruments according to his own system of ]s. | |||

| ] of ] is regarded as the most famous example of an outsider musician.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Vivinetto |first1=Gina |title=The bipolar poet |url=http://www.sptimes.com/2003/07/19/Floridian/The_bipolar_poet.shtml |newspaper=] |date=July 19, 2003|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030825171545/http://www.sptimes.com/2003/07/19/Floridian/The_bipolar_poet.shtml|url-status=dead|archive-date=August 25, 2003}}</ref> Chusid felt that "it's difficult" to argue for Wilson as an outsider due to his popularity, but acknowledged that his struggles with mental illness and the widely circulated bootlegs of ] "certify his outsider status".<ref name="Chusid2000"/> | |||

| ] were a 1960s rock band of sisters with only rudimentary musical skill, whose ineptitude became semi-legendary. The band was formed on the insistence of their father, Austin Wiggin, who believed that his mother foresaw the band's rise to stardom. As the obscure LP achieved recognition among collectors, the band was praised for their raw, intuitive composition style and lyrical honesty. | |||

| ==Cultural resonance and influence== | |||

| ]<ref name="autogenerated1" /> (1946–2006) was the original lead singer and songwriter for ]. He left the group in 1968, partway through the band's second album, amidst speculations of mental illness exacerbated by heavy drug use. After he left the group, he completed two solo albums and attempted a comeback with ], but his mental disturbances marred both projects and he soon went into self-imposed seclusion for the rest of his life. | |||

| ], sometimes cited as the "godfather of outsider music"<ref name="fish"/><ref>{{cite news|title=I'm crazy for you... but not that crazy|url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2006/mar/19/42|work=]|date=March 18, 2006}}</ref>]] | |||

| Chusid credited outsider musicians for the existence of ] ("invented by an outsider, ]"), the ] and ] record labels, and the "punk/new-wave/no-wave upheaval that undermined prog-rock and airbrush-pop in the mid- to late-1970s hyped itself with the defiant notion that anyone―regardless of technical proficiency or lack thereof―could make music as long as it represented genuine, naturalistic self-expression."{{sfn|Chusid|2000}} Specific acts that "significantly contributed―directly and indirectly―to contemporary popular music" include ], ], ], ], ], ]<ref>{{Cite news |last=Dee |first=Johnny |date=2010-07-16 |title=Taking over YouTube: the irresistible rise of Tonetta |language=en-GB |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/jul/17/tonetta-videos-youtube-johnny-dee |access-date=2023-05-05 |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> and ].<ref name="Chusid2000">{{cite book|last=Chusid|first=Irwin|author-link=Irwin Chusid|title=Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kT9dnDaFdX8C|year=2000|publisher=Chicago Review Press|isbn=978-1-56976-493-0|page=xv}}</ref> Conversely, the book ''Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music'' (2007) argues that "few of the outsiders praised by their fans can be called innovators; most of them are simply naïve."<ref name="BarkerTaylor2007">{{cite book|last1=Barker|first1=Hugh|last2=Taylor|first2=Yuval|title=Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music|url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780393060782|url-access=registration|year=2007|publisher=W. W. Norton|isbn=978-0-393-06078-2|page=}}</ref> | |||

| ] are a US dadaist, avant-garde music and visual arts collective who have maintained complete anonymity throughout their career. They released over sixty albums, created numerous musical short films, designed three CD-ROM projects and ten DVDs, and undertook six world tours. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] (1941-2010) is the stage name of Don van Vliet, who performed noisy, free jazz-influenced blues in the 1960s and 1970s. His music, which used shifting time signatures and surreal lyrics, had a major influence on the ], ], ] and ] genres. | |||

| ]'s '']'' (1969), Beefheart's '']'' (produced by Frank Zappa, 1969), and Barrett's '']'' (1970), according to music historian John Encarnacao, "were particularly important in helping to define a framework through which outsider recordings are understood ... seeded many ideas and practices, affirming them as desirable in the context of rock mythology."{{sfn|Encarnacao|2016|p=105}} In 1969, Zappa co-founded ], a label dedicated to "musical and sociological material that the important record companies would probably not allow you to hear," and approached the production of ''Trout Mask Replica'' like an anthropological ].{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=110}} Beefheart was not on the Bizarre label, but ] was. Fischer was a street performer discovered by Zappa and is sometimes regarded as "the grandfather of outsider music".<ref name="fish">{{cite news|last1=Fox|first1=Margalit|title=Wild Man Fischer, Outsider Musician, Dies at 66|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/18/arts/music/wild-man-fischer-outsider-musician-dies-at-66.html|work=]|date=June 17, 2011}}</ref> In the liner notes of the 1968 album '']'', Zappa writes: "Please listen to this album several times before you decide whether or not you like it or what Wild Man Fischer is all about. He has something to say to you, even though you might not want to hear it." According to musicologist Adam Harper, the writing prefigures similar commentary on "the also mentally ill Daniel Johnston."{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=100}} | |||

| ]<ref name="autogenerated1" /> (1961- ) is a Texas singer-songwriter with ] known for recording music on his radio boom box. His songs are often called "painfully direct," and tend to display a blend of childlike naïveté with darker, "spooky" themes. His performances often seem faltering or uncertain; one critic writes that Johnston's recordings range from "spotty to brilliant." He also has a documentary, '']'', centered around his life and music. | |||

| After a 1980 reissue on ]'s Red Rooster Records (distributed by Rounder Records), ] attracted notoriety for their 1969 album '']'', which received prominent national coverage. It was referred to as "the worst rock album ever made" by the '']'' and later championed in published lists such as "the 100 most influential alternative albums of all time", "the greatest garage recordings of the 20th century", and "the fifty most significant indie records".{{sfn|Harper|2014|pp=109–110}} ] famously praised the band as better than ], and Zappa also held the band in high regard, much higher than the Shaggs themselves, who were embarrassed by the record.<ref name=newyorker2017>{{cite magazine|url=https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-shaggs-reunion-concert-was-unsettling-beautiful-eerie-and-will-probably-never-happen-again|title=The Shaggs Reunion Concert Was Unsettling, Beautiful, Eerie, and Will Probably Never Happen Again|first=Howard|last=Fishman|magazine=] |date=August 30, 2017|access-date=January 8, 2020}}</ref> In the 1990s, interest in outsider music was spurred by books such as ''Incredibly Strange Music'' (1994) and compilations devoted to obscure musicians such as ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Chusid|2000}} | |||

| ]<ref></ref> (1904-2002) was a ], ]-born multi-instrumentalist and former 1926 Miss St. Louis who, in 1965 recorded the album ''Into Outer Space With Lucia Pamela''. The self-funded album (released in 1969) consisted largely of Pamela breathlessly telling listeners of her adventures in outer space where she meets intergalactic roosters, Native Americans and travels upon blue winds. Pamela (playing the accordion, drums, clarinet and piano) was nearly forgotten as a performer until 1992, when Irwin Chusid revived her legacy by producing a reissued version of the album. She is perhaps slightly better known as the mother of ], the former owner of the ]. | |||

| ==Lo-fi music== | |||

| Other notable musicians who are identified with outsider music include: | |||

| {{Main|Lo-fi music}} | |||

| Outsider musicians tend to overlap with "]" artists since their work is rarely captured in professional studios.<ref name="Harperthesis"/> Harper credits the discourse surrounding Daniel Johnston and ] with "form a bridge between 1980s primitivism and the lo-fi ] of the 1990s. ... both musicians introduced the notion that lo-fi was not just acceptable but the special context of some extraordinary and brilliant musicians."{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=180}} Critics frequently write about Johnston's "pure and childlike soul" and describe him as the "Brian Wilson" of lo-fi.<ref>{{cite news|last1=McNamee|first1=David|title=The myth of Daniel Johnston's genius|url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2009/aug/10/daniel-johnston|work=]|date=August 10, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| *] | |||

| *], one-song wonder best known for "You're Driving Me Mad," a heavy metal song with uncharacteristic lyric performance | |||

| ], who pioneered lo-fi/DIY music, was affiliated with Irwin Chusid as well as being associated with the "outsider" tag. He recalled "always ha the dilemma that did not want to present me as an outsider, like a Wesley Willis or a Daniel Johnston, or these people that are touched in the head and have a certain gift. I love outsider music ... but they have no concept as to how to write or arrange a Brian Wilson song." (Moore's father, ], was a consummate musical insider, having worked as a ] with the ].)<ref>{{cite magazine|last1=Ingram|first1=Matthew|title=Here Comes the Flood|magazine=]|date=June 2012|issue=340|url=http://www.moorestevie.com/press/wire12.html}}</ref> | |||

| *], began writing songs after sustaining a head injury in a car accident in 2009. A self-taught artist, he is becoming known for his raw, unpolished sound, melancholy lyrics, and unique melodies. | |||

| *], a spoken-word artist known for his often vulgar stream-of-consciousness rants | |||

| *], Massachusetts music teacher | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *], career criminal and commune leader, recorded a series of songs with his "family" | |||

| *The ], an extremely poorly received vaudeville act | |||

| *], character actor who extended his eccentric persona into music | |||

| *] | |||

| *], a punk/celebrity-exploitation band featuring ], known for acting in several films by ] | |||

| *], early 20th-century off-key soprano | |||

| *], best known for his surreal 1977 album '']'', which includes songs such as "6.4 = Make Out" and "Chromium Bitch" | |||

| *], outsider metal band from ] best known for their album ]<ref>{{cite web|title=Second Tunnel by Grand Reefer at rateyourmusic.com|url=http://rateyourmusic.com/release/album/grand_reefer/second_tunnel/}}</ref> | |||

| *], a forerunner to ] known for his morbid choices of lyrics | |||

| *] | |||

| *], nursing-home resident who recorded a 47-minute marathon of Tin Pan Alley tunes known as ''Downloading the Repertoire'' | |||

| *], founder and lead singer of ], who has collaborated with several outsider musicians and himself has a nasally singing voice, rudimentary guitar skill, and unorthodox songwriting approaches | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *], an English record producer. Curiously, Meek was in the position of the archetypical insider and produced several mainstream pop hits, most famously "]," but is nonetheless included in part for his mental illness, unusual (but effective) techniques, and closeted homosexuality (alluded to in his final record, "]"). | |||

| *], actor whose primary contribution to music was a recording of "]," a song based on the book '']''. | |||

| *], record producer from ] best known as rapper ] | |||

| *], who achieved fame on ] and around the internet for his low-budget music videos that first aired on the ] music show ''The Uncharted Zone''. | |||

| *], blind street musician who fashioned his own instruments and dressed as a Viking | |||

| *], a warbling, self-trained, middle-aged housewife who reluctantly rose to stardom as a novelty act in the 1960s | |||

| *] | |||

| *The ], an orchestra whose members were all novices at the instrument they played | |||

| *], son of Nashville producer Bob Moore known for his experimental, homebrewed recordings | |||

| *] | |||

| *], scat artist who dubbed himself the "Human Horn" and dubbed his unusual scatting over all sorts of music | |||

| *] | |||

| * ], a teenager from ] who has written and recorded over 500 songs that are off-tempo, low fidelity and otherwise completely idiosyncratic, bearing closest resemblance to rap. | |||

| *], late-1980s public access cable star known for her off-key renditions of popular songs, often with incorrect lyrics | |||

| *] also known as the Gangsta Rabbi is a bipolar punk musician who performs Jewish-themed punk rock using only bass guitar and flutes | |||

| *], YouTube sensation known for his rich baritone and socially conscious lyrical content. | |||

| *], another forerunner to psychobilly whose songs included incomprehensible yelling and random rhythms. Also known for launching the career of ]. | |||

| *], low-fi comedy from Philadelphia | |||

| *], a man who performed mostly ] tunes with a ] in a falsetto voice; came to fame on '']''. | |||

| *] | |||

| *], Chicago schizophrenic who would make stream-of-consciousness rants, many of which involve ], accompanied by his keyboard to scare off his "demons" | |||

| *], best known for his a capella, almost sobbing songs and his brief association with ] | |||

| *], Los Angeles crime analyst with no musical training who became infamous for his audition on '']'' | |||

| *], consisting almost entirely of spoken-word covers of popular songs. | |||

| *], was a musician that was heavily influenced by Frank Zappa And Captain Beef Heart came to sculpt his own unique sound he was also a painter and professional wrestling personality for a period. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{col-float}} | |||

| *] | |||

| {{col-float-break}} | |||

| *] | |||

| '''Related topics''' | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{col-float-break}} | |||

| '''Documentary films''' | |||

| * '']'' (2003) (about ]) | |||

| * '']'' (2005) | |||

| * '']'' (2003) | |||

| * '']'' (2005) | |||

| * '']'' (2005) | |||

| {{col-float-end}} | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| ] | |||

| * article in MungBeing magazine | |||

| ] | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 07:59, 22 February 2024

Music genre This article is about the music genre. For the record label, see Outside Music. For the jazz technique, see Outside (jazz).Outsider music (from "outsider art") is music created by self-taught or naïve musicians. The term is usually applied to musicians who have little or no traditional musical experience, who exhibit childlike qualities in their music, or who have intellectual disabilities or mental illnesses. The term was popularized in the 1990s by journalist and WFMU DJ Irwin Chusid.

Outsider musicians often overlap with lo-fi artists, since their work is rarely captured in professional recording studios. Examples include Daniel Johnston, Wesley Willis, and Jandek, who each became the subjects of documentary films in the 2000s.

Etymology

The term "outsider music" is traced to the definitions of "outsider art" and "naïve art". "Outsider art" is rooted in the 1920s French concept of "L'Art Brut" ("raw art"). In 1972, academic Roger Cardinal introduced "outsider art" as the American counterpart of "L'Art Brut", which originally referred to work created exclusively by children or the mentally ill. The word "outsider" began to be applied to music cultures as early as 1959, with respect to jazz, and to rock as early as 1979. In the 1970s, "outsider music" was also a "favorite epithet" in music criticism in Europe. By the 1980s and 1990s, "outsider" was common in the cultural lexicon and was synonymous with "self-taught", "untrained", and "primitive".

Definition and scope

Although outsider music has existed since before written history, it was not until the advent of sound reproduction and music exchange networks that such a genre was recognized. Music journalist Irwin Chusid is credited with adapting "outsider art" for music in a 1996 article for the Tower Records publication Pulse!. As a DJ on the New Jersey radio station WFMU in the 1980s, he had been an influential figure in independent music scenes. In 2000, he authored a book titled Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music, which attempted to introduce and market outsider music as a genre. He summarized the concept thus:

... there are countless "unintentional renegades," performers who lack overt self-consciousness about their art. As far as they're concerned, what they're doing is "normal." And despite paltry incomes and dismal record sales, they're happy to be in the same line of work as Celine Dion and Andrew Lloyd Webber. ... Their vocals sound melodically adrift; their rhythms stumble. They seem harmonically without anchor. Their instrumental proficiency may come across as laughably incompetent. ... They get little or no commercial radio exposure, their followings are limited, and they have roughly the same likelihood of attaining mainstream success that a possum has of skittering safely across a six-lane freeway. ... The outsiders in this book, for the most part, lack self-awareness. They don't boldly break the rules, because they don't know there are rules.

As was common with journalists who championed musical primitivism in the 1980s, Chusid considered outsiders more "authentic" than artists whose music is "exploited through conventional music channels" and "revised, remodeled, and re-coifed; touched-up and tweaked; Photoshopped and focus-grouped" by the time it reaches the listener, to the point that it is "Music by Committee". On the other hand, outsider artists have much "greater individual control over the final creative contour", either because of a low budget or because of their "inability or unwillingness to cooperate with or trust anyone but themselves."

Outsider music does not generally include avant-garde music, world music, songs recorded solely for their novelty value, or anything self-consciously camp or kitsch; Chusid uses the term "incorrect music" for music that is intentionally recorded to draw bad reactions, from non-musician celebrity entertainers attempting to cross over into music, or from artists who are talented and self-aware enough not to produce such music but do so anyway. Works are usually sourced from home recordings or independent recording studios "with no quality control". In Songs in the Key of Z, Chusid explicitly avoided discussing "unpopular", "uncommercial", or "underground" artists, and disqualified "just about anyone who could keep an orchestra or band together." He did include a few acts in the definition that broke through to mainstream fame as novelty acts; Tiny Tim, for example, is included despite a consistent three-decade career in the music industry that included a major chart hit, Joe Meek was one of the United Kingdom's most influential and successful sound engineers of the 1960s, and the Legendary Stardust Cowboy had a brief moment of widespread fame in the 1960s with several national television appearances.

Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys is regarded as the most famous example of an outsider musician. Chusid felt that "it's difficult" to argue for Wilson as an outsider due to his popularity, but acknowledged that his struggles with mental illness and the widely circulated bootlegs of his unreleased 1970s and 1980s demos "certify his outsider status".

Cultural resonance and influence

Chusid credited outsider musicians for the existence of dub reggae ("invented by an outsider, Lee "Scratch" Perry"), the K Records and Sub Pop record labels, and the "punk/new-wave/no-wave upheaval that undermined prog-rock and airbrush-pop in the mid- to late-1970s hyped itself with the defiant notion that anyone―regardless of technical proficiency or lack thereof―could make music as long as it represented genuine, naturalistic self-expression." Specific acts that "significantly contributed―directly and indirectly―to contemporary popular music" include Syd Barrett, Captain Beefheart, the Shaggs, Harry Partch, Robert Graettinger, Tonetta and Daniel Johnston. Conversely, the book Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music (2007) argues that "few of the outsiders praised by their fans can be called innovators; most of them are simply naïve."

Skip Spence's Oar (1969), Beefheart's Trout Mask Replica (produced by Frank Zappa, 1969), and Barrett's The Madcap Laughs (1970), according to music historian John Encarnacao, "were particularly important in helping to define a framework through which outsider recordings are understood ... seeded many ideas and practices, affirming them as desirable in the context of rock mythology." In 1969, Zappa co-founded Bizarre Records, a label dedicated to "musical and sociological material that the important record companies would probably not allow you to hear," and approached the production of Trout Mask Replica like an anthropological field recording. Beefheart was not on the Bizarre label, but Larry "Wild Man" Fischer was. Fischer was a street performer discovered by Zappa and is sometimes regarded as "the grandfather of outsider music". In the liner notes of the 1968 album An Evening with Wild Man Fischer, Zappa writes: "Please listen to this album several times before you decide whether or not you like it or what Wild Man Fischer is all about. He has something to say to you, even though you might not want to hear it." According to musicologist Adam Harper, the writing prefigures similar commentary on "the also mentally ill Daniel Johnston."

After a 1980 reissue on NRBQ's Red Rooster Records (distributed by Rounder Records), The Shaggs attracted notoriety for their 1969 album Philosophy of the World, which received prominent national coverage. It was referred to as "the worst rock album ever made" by the New York Times and later championed in published lists such as "the 100 most influential alternative albums of all time", "the greatest garage recordings of the 20th century", and "the fifty most significant indie records". Lester Bangs famously praised the band as better than the Beatles, and Zappa also held the band in high regard, much higher than the Shaggs themselves, who were embarrassed by the record. In the 1990s, interest in outsider music was spurred by books such as Incredibly Strange Music (1994) and compilations devoted to obscure musicians such as B. J. Snowden, Wesley Willis, Lucia Pamela, and Eilert Pilarm.

Lo-fi music

Main article: Lo-fi musicOutsider musicians tend to overlap with "lo-fi" artists since their work is rarely captured in professional studios. Harper credits the discourse surrounding Daniel Johnston and Jandek with "form a bridge between 1980s primitivism and the lo-fi indie rock of the 1990s. ... both musicians introduced the notion that lo-fi was not just acceptable but the special context of some extraordinary and brilliant musicians." Critics frequently write about Johnston's "pure and childlike soul" and describe him as the "Brian Wilson" of lo-fi.

R. Stevie Moore, who pioneered lo-fi/DIY music, was affiliated with Irwin Chusid as well as being associated with the "outsider" tag. He recalled "always ha the dilemma that did not want to present me as an outsider, like a Wesley Willis or a Daniel Johnston, or these people that are touched in the head and have a certain gift. I love outsider music ... but they have no concept as to how to write or arrange a Brian Wilson song." (Moore's father, Bob Moore, was a consummate musical insider, having worked as a session musician with the Nashville A-Team.)

See also

Related topics

Documentary films

- The Daddy of Rock 'n' Roll (2003) (about Wesley Willis)

- The Devil and Daniel Johnston (2005)

- Jandek on Corwood (2003)

- Derailroaded: Inside the Mind of Wild Man Fischer (2005)

- Beautiful Dreamer: Brian Wilson and the Story of Smile (2005)

References

- ^ Harper, Adam (2014). Lo-Fi Aesthetics in Popular Music Discourse (PDF). Wadham College. pp. 48, 190. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Harper 2014, p. 347.

- Encarnacao, John (2016). Punk Aesthetics and New Folk: Way Down the Old Plank Road. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-317-07321-5.

- ^ Plasketes, George (2016). B-Sides, Undercurrents and Overtones: Peripheries to Popular in Music, 1960 to the Present. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-317-17113-3.

- Charles Winick, "The Use of Drugs by Jazz Musicians", Social Problems 7, no. 3 (Winter 1959–1960): 240–53. Citation on 250.

- Bernice Martin, "The Sacralization of Disorder: Symbolism in Rock Music", Sociological Analysis 40, no. 2 (Summer 1979): 87–124. Citation on 116.

- Zdenka Kapko-Foretić, "Kölnska škola avangarde", Zvuk: Jugoslavenska muzička revija, 1980 no. 2:50–55. Citation on 54.

- ^ Misiroglu, Gina, ed. (2015). American Countercultures: An Encyclopedia of Nonconformists, Alternative Lifestyles, and Radical Ideas in U.S. History. Routledge. pp. 541–542. ISBN 978-1-317-47729-7.

- ^ Chusid 2000.

- Harper 2014, pp. 48, 53, 63–64.

- Vivinetto, Gina (July 19, 2003). "The bipolar poet". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on August 25, 2003.

- ^ Chusid, Irwin (2000). Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music. Chicago Review Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-1-56976-493-0.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (June 17, 2011). "Wild Man Fischer, Outsider Musician, Dies at 66". The New York Times.

- "I'm crazy for you... but not that crazy". The Observer. March 18, 2006.

- Dee, Johnny (2010-07-16). "Taking over YouTube: the irresistible rise of Tonetta". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- Barker, Hugh; Taylor, Yuval (2007). Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music. W. W. Norton. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-393-06078-2.

- Encarnacao 2016, p. 105.

- Harper 2014, p. 110.

- Harper 2014, p. 100.

- Harper 2014, pp. 109–110.

- Fishman, Howard (August 30, 2017). "The Shaggs Reunion Concert Was Unsettling, Beautiful, Eerie, and Will Probably Never Happen Again". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- Harper 2014, p. 180.

- McNamee, David (August 10, 2009). "The myth of Daniel Johnston's genius". The Guardian.

- Ingram, Matthew (June 2012). "Here Comes the Flood". The Wire. No. 340.