| Revision as of 16:46, 27 February 2014 editPigsonthewing (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, IP block exemptions, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors266,658 edits removed Category:World War I; added Category:Home front during World War I using HotCat← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:13, 14 January 2025 edit undoRichard Nevell (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users10,563 edits →Germany: fmt ref | ||

| (339 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| The '''home front during World War I''' covers the domestic, economic, social and political histories of countries involved in ]. It covers the mobilization of war supplies and soldiers, but does not include the military history. During the entire war, ], including many weakened by years of malnutrition who fell in the worldwide ], which struck late in 1918 just as the war was ending. | |||

| ], circa 1917-1919.]] | |||

| The '''home front during World War I''' covers the domestic, economic, social and political histories of countries involved in ]. It covers the mobilization of armed forces and war supplies, lives of others, but does not include the military history. For nonmilitary interactions among the major players see ]. | |||

| About 10.9 million combatants and seven million civilians ], including many weakened by years of malnutrition; they fell in the worldwide ], which struck late in 1918, just as the war was ending. | |||

| The Allies had much more potential wealth they could spend on the war. One estimate (using 1913 US dollars) is that the Allies spent $147 billion on the war and the Central Powers only $61 billion. Among the Allies, Britain and its Empire spent $47 billion and the U.S. $27 billion; among the Central Powers Germany spent $45 billion.<ref>H.E. Fisk, ''The Inter-Allied Debts'' (1924) pp 13 & 325 reprinted in Horst Menderhausen, ''The Economics of War'' (1943 edition), appendix table II</ref> | |||

| The ] had much more potential wealth that they could spend on the war. One estimate (using 1913 US dollars), is that the Allies spent $147 billion ($4.5tr in 2023 USD) on the war and the ] only $61 billion ($1.88tr in 2023 USD). Among the Allies, Britain and its Empire spent $47 billion and the ] $27 billion; among the Central Powers, Germany spent $45 billion.<ref>H.E. Fisk, ''The Inter-Allied Debts'' (1924) pp 13 & 325 reprinted in Horst Menderhausen, ''The Economics of War'' (1943 edition), appendix table II</ref> | |||

| Total war demanded total mobilization of all the nation's resources for a common goal. Manpower had to be channeled into the front lines (all the powers except the United States and Britain had large trained reserves designed just for that). Behind the lines labor power had to be redirected away from less necessary activities that were luxuries during a total war. In particular, vast munitions industries had to be built up to provide shells, guns, warships, uniforms, airplanes, and a hundred other weapons both old and new. Agriculture had to be mobilized as well, to provide food for both civilians and for soldiers (many of whom had been farmers and needed to be replaced by old men, boys and women) and for horses to move supplies. Transportation in general was a challenge, especially when Britain and Germany each tried to intercept merchant ships headed for the enemy. Finance was a special challenge. Germany financed the Central Powers. Britain financed the Allies until 1916, when it ran out of money and had to borrow from the United States. The U.S. took over the financing of the Allies in 1917 with loans that it insisted be repaid after the war. The victorious Allies looked to defeated Germany in 1919 to pay "reparations" that would cover some of their costs. Above all, it was essential to conduct the mobilization in such a way that the short term confidence of the people was maintained, the long-term power of the political establishment was upheld, and the long-term economic health of the nation was preserved.<ref>Hardach, ''First World War: 1914–1918'' (1981)</ref> | |||

| Total war demanded the total mobilization of all the nation's resources for a common goal. Manpower had to be channeled into the front lines (all the powers except the United States and Britain had large trained reserves designed for just that). Behind the lines labor power had to be redirected away from less necessary activities that were luxuries during a total war. In particular, vast munitions industries had to be built up to provide shells, guns, warships, uniforms, airplanes, and a hundred other weapons, both old and new. Agriculture had to be mobilized as well, to provide food for both civilians and for soldiers (many of whom had been farmers and needed to be replaced by old men, boys and women) and for horses to move supplies. Transportation in general was a challenge, especially when Britain and Germany each tried to intercept merchant ships headed for the enemy. Finance was a special challenge. Germany financed the Central Powers. Britain financed the Allies until 1916, when it ran out of money and had to borrow from the United States. The US took over the financing of the Allies in 1917 with loans that it insisted be repaid after the war. The victorious Allies looked to defeated Germany in 1919 to pay "reparations" that would cover some of their costs. Above all, it was essential to conduct the mobilization in such a way that the short term confidence of the people was maintained, the long-term power of the political establishment was upheld, and the long-term economic health of the nation was preserved.<ref>Hardach, ''First World War: 1914–1918'' (1981)</ref> For more details on economics see ]. | |||

| For more details on economics see ]. | |||

| World War I had a profound impact on woman suffrage across the belligerents. Women played a major role on the homefronts and many countries recognized their sacrifices with the vote during or shortly after the war, including the United States, Britain, Canada (except ]), Denmark, Austria, the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, Sweden and Ireland. France almost did so but stopped short.<ref>{{Cite journal | last = Palm | first = Trineke | title = Embedded in social cleavages: an explanation of the variation in timing of women's suffrage | journal = ] | volume = 36 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–22 | doi = 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2012.00294.x | date = March 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Financial costs== | |||

| {{Further|Economic history of World War I}} | |||

| The total direct cost of war, for all participants including those not listed here, was about $80 billion in 1913 US dollars. Since $1 billion in 1913 is approximately $46.32 billion in 2023 US dollars, the total cost comes to around $2.47 trillion in 2023 dollars. Direct cost is figured as actual expenditures during war minus normal prewar spending. It excludes postwar costs such as pensions, interest, and veteran hospitals. Loans to/from allies are not included in "direct cost". Repayment of loans after 1918 is not included.<ref>Harvey Fisk, ''The Inter-Ally Debts: An Analysis of War and Post-War Public Finance, 1914-1923'' (1924) pp 1, 21-37{{ISBN?}}</ref> | |||

| The total direct cost of the war as a percent of wartime national income: | |||

| * '''Allies''': Britain, 37%; France, 26%; Italy, 19%; Russia, 24%; United States, 16%. | |||

| * '''Central Powers''': Austria-Hungary, 24%; Germany, 32%; Turkey unknown. | |||

| The amounts listed below are presented in terms of 1913 US dollars, where $1 billion then equals about $25 billion in 2017.<ref>Fisk, ''The Inter-Ally Debts'' pp 21-37.</ref> | |||

| * Britain had a direct war cost about $21.2 billion; it made loans to Allies and Dominions of $4.886 billion, and received loans from the United States of $2.909 billion. | |||

| * France had a direct war cost about $10.1 billion; it made loans to Allies of $1.104 billion, and received loans from Allies (United States and Britain) of $2.909 billion. | |||

| * Italy had a direct war cost about $4.5 billion; it received loans from Allies (United States and Britain) of $1.278 billion. | |||

| * The United States had a direct war cost about $12.3 billion; it made loans to Allies of $5.041 billion. | |||

| * Russia had a direct war cost about $7.7 billion; it received loans from Allies (United States and Britain) of $2.289 billion.<ref>Peter Gatrell, ''Russia's First World War: A Social and Economic History'' (2005) pp 132-53</ref> | |||

| The two governments agreed that financially Britain would support the weaker Allies and that France would take care of itself.<ref>Martin Horn, ''Britain, France, and the financing of the First World War'' (2002) ch 1.</ref> In August 1914, ], a Morgan partner, traveled to London and made a deal with the ] to make J.P. Morgan & Co. the sole underwriter of ] for Great Britain and France. The Bank of England became a fiscal agent of J.P. Morgan & Co., and ''vice versa''. Over the course of the war, J.P. Morgan loaned about $1.5 billion (approximately ${{formatnum:{{inflation|US|1.5|1929|r=0}}}} billion in today's dollars) to the Allies to fight against the Germans.<ref name=wolff>{{Cite book|title=Black Sun: The Brief Transit and Violent Eclipse of Harry Crosby |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RpVaAAAAMAAJ|author=Geoffrey Wolff|year=2003|isbn=978-1-59017-066-3|publisher=New York Review of Books}}</ref>{{rp|63}} Morgan also invested in the suppliers of war equipment to Britain and France, thus profiting from the financing and purchasing activities of the two European governments. | |||

| Britain made heavy loans to Tsarist Russia; the Lenin government after 1920 refused to honor them, causing long-term issues.<ref>Jennifer Siegel, ''For Peace and Money: French and British Finance in the Service of Tsars and Commissars'' (Oxford UP, 2014).</ref> | |||

| ==Britain== | ==Britain== | ||

| {{main|History of the United Kingdom during World War I}} | {{main|History of the United Kingdom during World War I|British entry into World War I}} | ||

| {{see also| |

{{see also|Timeline of the United Kingdom home front during World War I}} | ||

| At the outbreak of war, patriotic feelings spread throughout the country, and many of the class barriers of ] faded during the years of combat.<ref>National Archives </ref> However the Catholics in southern Ireland moved overnight to demands for complete immediate independence after the failed ] of 1916. Northern Ireland remained loyal to the crown. | |||

| At the outbreak of war, patriotic feelings spread throughout the country, and many of the class barriers of ] faded during the years of combat.<ref>National Archives </ref> However, the Catholics in southern Ireland moved overnight to demands for complete immediate independence after the failed ] of 1916. Northern Ireland remained loyal to the crown. | |||

| Economic sacrifices were made, however, in the name of defeating the enemy.<ref>Stephen Broadberry and Peter Howlett, "The United Kingdom during World War I: business as usual?" in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch 7</ref> In 1915 Liberal politician ] took charge of the newly created Ministry of Munitions. He dramatically increased output of artillery shells—the main weapon actually used in battle. In 1916 he became secretary for war. Prime Minister H. H. Asquith was a disappointment; he formed a coalition government in 1915 but it also was ineffective. Asquith was replaced by Lloyd George in late 1916. He had a strong hand in the managing of every affair, making many decisions himself. Historians credit Lloyd George for providing the driving energy and organisation that won the War.<ref>A.J.P. Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) pp. 34–5, 54, 58, 73–76</ref> | |||

| In 1914 Britain had by far the largest and most efficient financial system in the world.<ref>Christopher Godden, "The Business of War: Reflections on Recent Contributions to the Economic and Business Histories of the First World War." ''Œconomia. History, Methodology, Philosophy'' 6#4 (2016): 549-556. </ref> Roger Lloyd-Jones and M. J. Lewis argue: | |||

| Although ], morale remained relatively high due in part to the morale-building propaganda churned out by the national newspapers.<ref>Ian F. W. Beckett, ''The Great war'' (2nd ed. 2007) pp 394–395</ref> With a severe shortage of skilled workers, industry redesigned work so that it could be done by unskilled men and women (termed the "dilution of labour") so that war-related industries grew rapidly. Lloyd George cut a deal with the trades unions—they approved the dilution (since it would be temporary) and threw their organizations into the war effort.<ref>Beckett (2007), pp. 341, 455</ref> | |||

| : To prosecute industrial war required the mobilization of economic resources for the mass production of weapons and munitions, which necessarily entitled fundamental changes in the relationship between the state (the procurer), business (the provider), labor (the key productive input), and the military (the consumer). In this context, the industrial battlefields of France and Flanders intertwined with the home front that produced the materials to sustain a war over four long and bloody years.<ref>Roger Lloyd-Jones and M. J. Lewis, ''Arming the Western Front: War, Business and the State in Britain, 1900–1920'' (Routledge, 2016), p 1.</ref> | |||

| Economic sacrifices were made, however, in the name of defeating the enemy.<ref>Stephen Broadberry and Peter Howlett, "The United Kingdom during World War I: business as usual?" in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch 7</ref> In 1915 Liberal politician ] took charge of the newly created Ministry of Munitions. He dramatically increased the output of artillery shells—the main weapon actually used in battle. In 1916 he became secretary for war. Prime Minister ] was a disappointment; he formed a coalition government in 1915 but it was also ineffective. Asquith was replaced by Lloyd George in late 1916. He had a strong hand in the managing of every affair, making many decisions himself. Historians credit Lloyd George with providing the driving energy and organisation that won the War.<ref>A.J.P. Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) pp. 34–5, 54, 58, 73–76</ref> | |||

| Historian ] sees a radical transformation of British society, a deluge that swept away many old attitudes and brought in a more equalitarian society. He sees the famous literary pessimism of the 1920s as misplaced, for there were major positive long-term consequences of the war. He points to new job opportunities and self-consciousness among workers that quickly built up the Labour Party, to the coming of partial woman suffrage, and to an acceleration of social reform and state control of the British economy. He finds a decline of deference toward the aristocracy and established authority in general, and a weakening among youth of traditional restraints on individual moral behavior. Marwick concludes that class differentials softened, national cohesion increased, and British society became more equal.<ref>Arthur Marwick, ''The Deluge: British Society and the First World War'' (1965)</ref> | |||

| Although ], morale remained relatively high due in part to the propaganda churned out by the national newspapers.<ref>Ian F. W. Beckett, ''The Great war'' (2nd ed. 2007) pp 394–395</ref> With a severe shortage of skilled workers, industry redesigned work so that it could be done by unskilled men and women (termed the "dilution of labour") so that war-related industries grew rapidly. Lloyd George cut a deal with the trades unions—they approved the dilution (since it would be temporary) and threw their organizations into the war effort.<ref>Beckett (2007), pp. 341, 455</ref> | |||

| ===Politics=== | |||

| Historian ] saw a radical transformation of British society, a deluge that swept away many old attitudes and brought in a more equalitarian society. He also saw the famous literary pessimism of the 1920s as misplaced, for there were major positive long-term consequences of the war. He pointed to new job opportunities and self-consciousness among workers that quickly built up the ], to the coming of partial woman suffrage, and an acceleration of social reform and state control of the British economy. He found a decline of deference toward the aristocracy and established authority in general, and a weakening among youth of traditional restraints on individual moral behavior. Marwick concluded that class differentials softened, national cohesion increased, and British society became more equal.<ref>Arthur Marwick, ''The Deluge: British Society and the First World War'' (1965)</ref> During the conflict, the various elements of the British Left created the War Emergency Workers' National Committee, which played a crucial role in supporting the most vulnerable people on the Home Front during the war, and in ensuring the British Labour remained united in the years after the Armistice.<ref>David Swift, "The War Emergency: Workers' National Committee." ''History Workshop Journal'' 81 (2016): 84-105. </ref> | |||

| ===Scotland=== | |||

| Scotland played a major role in the British effort in the First World War.<ref>C. M. M. Macdonald and E. W. McFarland, eds, ''Scotland and the Great War'' (Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press, 1999)</ref> It especially provided manpower, ships, machinery, food (particularly fish) and money, engaging with the conflict with some enthusiasm.<ref>D. Daniel, "Measures of enthusiasm: new avenues in quantifying variations in voluntary enlistment in Scotland, August 1914-December 1915", ''Local Population Studies,'' Spring 2005, Issue 74, pp. 16–35.</ref> With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent 690,000 men to the war, of whom 74,000 died in combat or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded.<ref>I. F. W. Beckett and K. R. Simpson, eds. ''A Nation in Arms: a Social Study of the British Army in the First World War'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985) p. 11.</ref><ref>R. A. Houston and W. W. Knox, eds, ''The New Penguin History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 2001), p. 426.</ref> Scottish urban centres, with their poverty and unemployment were favourite recruiting grounds of the regular British army, and ], where the female dominated jute industry limited male employment had one of the highest proportion of reservists and serving soldiers than almost any other British city.<ref name=Lenman&Mackie1991>B. Lenman and J., Mackie, (London: Penguin, 1991)</ref> Concern for their families' standard of living made men hesitate to enlist; voluntary enlistment rates went up after the government guaranteed a weekly stipend for life to the survivors of men who were killed or disabled.<ref>D. Coetzee, "A life and death decision: the influence of trends in fertility, nuptiality and family economies on voluntary enlistment in Scotland, August 1914 to December 1915", ''Family and Community History'', Nov 2005, vol. 8 (2), pp. 77–89.</ref> After the introduction of conscription from January 1916 every part of the country was affected. Occasionally Scottish troops made up large proportions of the active combatants, and suffered corresponding loses, as at the ], where there were three full Scots divisions and other Scottish units.<ref name=Lenman&Mackie1991/> Thus, although Scots were only 10 per cent of the British population, they made up 15 per cent of the national armed forces and eventually accounted for 20 per cent of the dead.<ref name=Buchanan2003p49>J. Buchanan, ''Scotland'' (Langenscheidt, 3rd edn., 2003), p. 49.</ref> Some areas, like the thinly populated Island of ] suffered some of the highest proportional losses of any part of Britain.<ref name=Lenman&Mackie1991/> Clydeside shipyards and the nearby engineering shops were the major centers of war industry in Scotland. In ], radical agitation led to industrial and political unrest that continued after the war ended.<ref>Bruce Lenman, ''An Economic History of Modern Scotland: 1660–1976'' (1977) pp 206–14</ref> | |||

| In Glasgow, the heavy demand for munitions and warships strengthened union power. There emerged a radical movement called "]" led by militant trades unionists. Formerly a Liberal Party stronghold, the industrial districts switched to Labour by 1922, with a base among the Irish Catholic working class districts. Women were especially active in solidarity on housing issues. However, the "Reds" operated within the Labour Party and had little influence in Parliament; the mood changed to passive despair by the late 1920s.<ref>Iain McLean, ''The Legend of Red Clydeside'' (1983)</ref> | |||

| ===Politics=== | |||

| {{See also|David Lloyd George}} | {{See also|David Lloyd George}} | ||

| ] became prime minister in December 1916 and immediately transformed the British war effort, taking firm control of both military and domestic policy.<ref>John Grigg, ''Lloyd George: War Leader 1916–1918'' (2002) vol 4 pp 1–30</ref><ref>A. J. P. Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) pp 73–99</ref> | ] became prime minister in December 1916 and immediately transformed the British war effort, taking firm control of both military and domestic policy.<ref>John Grigg, ''Lloyd George: War Leader 1916–1918'' (2002) vol 4 pp 1–30</ref><ref>A. J. P. Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) pp 73–99</ref> | ||

| In rapid succession in spring 1918 came a series of military and political crises.<ref>A. J. P. Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) pp 100–106</ref> The Germans, having moved troops from the Eastern front and retrained them in new tactics, |

In rapid succession in spring 1918 came a series of military and political crises.<ref>A. J. P. Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) pp 100–106</ref> The Germans, having moved troops from the Eastern front and retrained them in new tactics, now had more soldiers on the Western Front than the Allies. Germany launched a full scale ] (]), starting March 21 against the British and French lines, with the hope of victory on the battlefield before the American troops arrived in numbers. The Allied armies fell back 40 miles in confusion, and facing defeat, London realized it needed more troops to fight a mobile war. Lloyd George found a half million soldiers and rushed them to France, asked American President ] for immediate help, and agreed to the appointment of French General ] as commander-in-chief on the Western Front so that Allied forces could be coordinated to handle the German offensive.<ref>John Grigg, ''Lloyd George: War Leader 1916–1918'' (2002) vol 4 pp 478–83</ref> | ||

| Despite strong warnings it was a bad idea, the War Cabinet ]. The main reason was that labour in Britain demanded it as the price for cutting back on exemptions for certain workers. Labour wanted the principle established that no one was exempt, but it did not demand that the draft actually take place in Ireland. The proposal was enacted but never enforced. The Catholic bishops for the first time entered the fray and called for open resistance to a draft |

Despite strong warnings it was a bad idea, the War Cabinet ]. The main reason was that labour in Britain demanded it as the price for cutting back on exemptions for certain workers. Labour wanted the principle established that no one was exempt, but it did not demand that the draft actually take place in Ireland. The proposal was enacted but never enforced. The Catholic bishops for the first time entered the fray and called for open resistance to a draft. Many Irish Catholics and nationalists moved into the intransigent ] movement. This proved a decisive moment, marking the end of Irish willingness to stay inside the UK.<ref>Alan J. Ward, "Lloyd George and the 1918 Irish Conscription Crisis," ''Historical Journal'' (1974) 17#1 pp. 107–129 </ref><ref>Grigg, ''Lloyd George'' vol 4 pp 465–88</ref> | ||

| When on May 7, 1918, a senior army general on active duty, Major-General Sir ] went public with allegations that Lloyd George had lied to Parliament on military matters, ]. The German spring offensive had made unexpected major gains, and a scapegoat was needed. Asquith, the Liberal leader in the House, took up the allegations and attacked Lloyd George (also a Liberal), which further |

When on May 7, 1918, a senior army general on active duty, Major-General Sir ] went public with allegations that Lloyd George had lied to Parliament on military matters, ]. The German spring offensive had made unexpected major gains, and a scapegoat was needed. Asquith, the Liberal leader in the House, took up the allegations and attacked Lloyd George (also a Liberal), which further split the Liberal Party. While Asquith's presentation was poorly done, Lloyd George vigorously defended his position, treating the debate as a vote of confidence. He won over the House with a powerful refutation of Maurice's allegations. The main results were to strengthen Lloyd George, weaken Asquith, end public criticism of overall strategy, and strengthen civilian control of the military.<ref>John Gooch, "The Maurice Debate 1918," ''Journal of Contemporary History'' (1968) 3#4 pp. 211–228 </ref><ref>John Grigg, ''Lloyd George: War leader, 1916–1918'' (London: Penguin, 2002), pp 489–512</ref> | ||

| Meanwhile the German offensive stalled. By summer the Americans were sending 10,000 fresh men a day to the Western Front, a |

Meanwhile, the German offensive stalled. By summer the Americans were sending 10,000 fresh men a day to the Western Front, a more rapid response made possible by leaving their equipment behind and using British and French munitions. The German army had used up its last reserves and was steadily shrinking in number and weakening in resolve. Victory came with ] on November 11, 1918.<ref>A. J. P. Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) pp 108–11</ref> | ||

| ===Women=== | ===Women=== | ||

| Prime Minister David Lloyd George was clear about how important the women were: | |||

| :It would have been utterly impossible for us to have waged a successful war had it not been for the skill and ardour, enthusiasm and industry which the women of this country have thrown into the war.<ref>{{cite book|last=Bob Whitfield|title=The Extension of the Franchise, 1832-1931|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=a-Rd0iLobaEC&pg=PA167|year=2001|publisher=Heinemann|page=167|isbn=9780435327170}}</ref> | |||

| The militant suffragette movement was suspended during the war, and at the time people credited the new patriotic roles women played as earning them the vote in 1918.<ref>Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) p. 29, 94</ref> |

The militant suffragette movement was suspended during the war, and at the time people credited the new patriotic roles women played as earning them the vote in 1918.<ref>Taylor, ''English History, 1914–1945'' (1965) p. 29, 94</ref> However, British historians no longer emphasize the granting of woman suffrage as a reward for women's participation in war work. Pugh (1974) argues that enfranchising soldiers primarily and women secondarily was decided by senior politicians in 1916. In the absence of major women's groups demanding for equal suffrage, the government's conference recommended limited, age-restricted women's suffrage. The ] had been weakened, Pugh argues, by repeated failures before 1914 and by the disorganizing effects of war mobilization; therefore they quietly accepted these restrictions, which were approved in 1918 by a majority of the War Ministry and each political party in Parliament.<ref>Martin D. Pugh, "Politicians and the Woman's Vote 1914–1918," ''History,'' (1974), Vol. 59 Issue 197, pp 358–374</ref> More generally, Searle (2004) argues that the British debate was essentially over by the 1890s, and that granting the suffrage in 1918 was mostly a byproduct of giving the vote to male soldiers. Women in Britain finally achieved suffrage on the same terms as men in 1928.<ref>G.R. Searle, ''A New England? Peace and war, 1886–1918'' (2004) p 791</ref> | ||

| ==British Empire== | ==British Empire== | ||

| The British Empire provided imports of food and raw material, worldwide network of naval bases, and a steady flow of soldiers and workers into Britain.<ref>Ashley Jackson, "The British Empire and the First World War"''BBC History Magazine'' 9#11 (2008) </ref> | |||

| ===Canada=== | ===Canada=== | ||

| {{multiple image|direction=vertical|width=150|align=right|footer= Yiddish (top) and English versions of World War I recruitment posters directed at Canadian Jews.|image1=Enlist-canadaWW1-yiddish.jpg|alt1=Yiddish World War I recruitment poster|caption1= |image2=The Jews the world over love liberty poster.jpg|alt2=English World War I recruitment poster|caption2= |

{{multiple image|direction=vertical|width=150|align=right|footer= Yiddish (top) and English versions of World War I recruitment posters directed at Canadian Jews.|image1=Enlist-canadaWW1-yiddish.jpg|alt1=Yiddish World War I recruitment poster|caption1= |image2=The Jews the world over love liberty poster.jpg|alt2=English World War I recruitment poster|caption2=}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| {{main|Canada in the World Wars and Interwar Years#World War I}} | {{main|Canada in the World Wars and Interwar Years#World War I}} | ||

| The 620,000 men in service were most notable for combat in the trenches of the ]; there were 67,000 war dead and 173,000 wounded. |

The 620,000 men in service were most notable for combat in the trenches of the ]; there were 67,000 war dead and 173,000 wounded. This total does not include the 2,000 deaths and 9,000 injuries in December 1917 when ], ].<ref>War Office, ''Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914–1920'' (London, 1922) p. 237</ref> | ||

| Volunteering provided enough soldiers at first, but high casualties soon required conscription, which was strongly opposed by Francophones. The |

Volunteering provided enough soldiers at first, but high casualties soon required conscription, which was strongly opposed by Francophones (French speakers, based mostly in ]). The ] saw the Liberal Party ripped apart, to the advantage of the ]'s Prime Minister ], who led a new ] to a landslide victory in 1917.<ref>Robert Craig Brown and Ramsay Cook, ''Canada, 1896–1921 A Nation Transformed'' (1974) ch 13</ref> | ||

| Distrusting the loyalties of ] and, especially, recent |

Distrusting the loyalties of ] and, especially, recent ] immigrants from ], the government interned thousands of aliens.<ref>Frances Swyripa and John Herd Thompson, eds. ''Loyalties in Conflict: Ukrainians in Canada During the Great War'' (1983)</ref> | ||

| The war validated Canada's new world role, in an almost-equal partnership with Britain in the ]. Arguing that Canada had become a true nation on the battlefields of Europe, Borden demanded and received a separate seat for Canada at the ]. |

The war validated Canada's new world role, in an almost-equal partnership with Britain in the ]. Arguing that Canada had become a true nation on the battlefields of Europe, Borden demanded and received a separate seat for Canada at the ]. Canada's military and civilian participation in the First World War strengthened a sense of British-Canadian nationhood among the Anglophones (English speakers). The Francophones (French speakers) supported the war at first, but pulled back and stood aloof after 1915 because of language disputes at home. Heroic memories centered around the ] where the unified Canadian corps captured Vimy ridge, a position that the French and British armies had failed to capture and "]" battles of 1918 which saw the ] of 100,000 defeat one fourth of the German Army on the Western Front.<ref>Jacqueline Hucker, "'Battle and Burial': Recapturing the Cultural Meaning of Canada's National Memorial on Vimy Ridge," ''Public Historian,'' (Feb 2009) 31#1 pp 89–109</ref> | ||

| ===Australia=== | ===Australia=== | ||

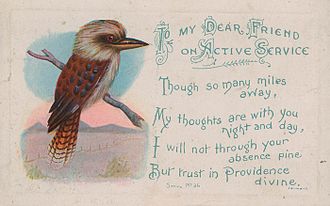

| ] active service postcard]] | ] active service postcard]] | ||

| ], prime minister from October 1915, expanded the government's role in the economy, while dealing with intense debates over the issue of conscription.<ref>Kosmas Tsokhas, "The Forgotten Economy and Australia's Involvement in the Great War," ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' (1993) 4#2 331-357</ref> | |||

| From a population of |

From a population of five million, 417,000 men enlisted; 330,000 went overseas to fight during the First World War. They were all volunteers, since the political battle for compulsory conscription failed. Some 58,000 died and 156,000 were wounded.<ref>See {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120215170018/http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/ww1.asp |date=2012-02-15 }}</ref> Gerhard Fischer argues that the government aggressively promoted economic, industrial, and social modernization in the war years.<ref>Gerhard Fischer, "'Negative integration' and an Australian road to modernity: Interpreting the Australian homefront experience in World War I," ''Australian Historical Studies,'' (April 1995) 26#104 pp 452–76</ref> However, he says it came through exclusion and repression. He says the war turned a peaceful nation into "one that was violent, aggressive, angst- and conflict-ridden, torn apart by invisible front lines of sectarian division, ethnic conflict and socio-economic and political upheaval." The nation was fearful of enemy aliens—especially Germans, regardless of how closely they identified with Australia. The government interned 2,900 German-born men (40% of the total) and deported 700 of them after the war.<ref>Graeme Davidson et al., ''The Oxford Companion to Australian History'' (2nd ed. 2001) p 283–4</ref> Irish nationalists and labor radicals were under suspicion as well. Racist hostility was high toward nonwhites, including Pacific Islanders, Chinese and Aborigines. The result, Fischer says, was a strengthening of conformity to imperial/British loyalties and an explicit preference for immigrants from the British Isles.<ref>Fischer, "'Negative integration' and an Australian road to modernity" p. 452 for quote</ref> | ||

| The major military event involved sending 40,000 ANZAC (Australia and New Zealand) soldiers in 1915 to seize the ] near Constantinople to open an Allied route to Russia and weaken the Ottoman Empire. |

The major military event involved sending 40,000 ANZAC (Australia and New Zealand) soldiers in 1915 to seize the ] near Constantinople to open an Allied route to Russia and weaken the Ottoman Empire. The campaign was a total failure militarily and 8,100 Australians died. However the memory was all-important, for it transformed the Australian mind and became an iconic element of the Australian identity and the founding moment of nationhood.<ref>Joan Beaumont, ''Australia's War 1914–18'' (1995)</ref> | ||

| ====Internment of German aliens==== | ====Internment of German aliens==== | ||

| The |

The '']'' provided the Commonwealth government with wide-ranging powers for a period of up to six months after the duration of the war.<ref name=homefront> | ||

| {{cite web |

{{cite web|title=Home front Powers 1914–1918 |publisher=anzacday.org |url=http://www.anzacday.org.au/history/ww1/homefront/powers.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20010415012538/http://www.anzacday.org.au/history/ww1/homefront/powers.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=15 April 2001 |access-date=2 May 2009 }}</ref> It covered: the prevention of trade with hostile nations, issuing loans to pay for the war effort, the introduction of a national taxation scheme, the fixing of the prices of certain goods, the internment of people considered a danger to Australia, the compulsory purchase of strategic goods, and the censorship of the media.<ref name=homefront/> | ||

| At the outbreak of the war there were about 35,000 people who had been born in either Germany or Austria-Hungary living in Australia.<ref>Ernest Scott, ''Australia During the War'' (7th ed. 1941) p 105 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130704190307/http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/first_world_war/volume.asp?levelID=67897 |date=2013-07-04 }}</ref> They had weak ties with Germany (and almost none to Austria) and many had enlisted in the Australian war effort. Nevertheless, fears ran high and internment camps were set up where those suspected of unpatriotic acts were sent. In total 4,500 people were interned under the provisions of the ''War Precautions Act'', of which 700 were naturalised Australians and 70 Australian born. Following the end of the war, 6,150 were deported.<ref name=homefront2>{{cite web|title=Internment in Australia during WWI |publisher=anzacday.org |url=http://www.anzacday.org.au/history/ww1/homefront/enemy.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20010415020511/http://www.anzacday.org.au/history/ww1/homefront/enemy.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=15 April 2001 |access-date=2 May 2009 }}</ref> | |||

| The main provisions of the Act were focused upon allowing the Commonwealth to enact legislation that was required for the smooth prosecution of the war. The main areas in which legislation was enacted under the ''War Precautions Act'' were: the prevention of trade with hostile nations, the creation of loans to raise money for the war effort, the introduction of a national taxation scheme, the fixing of the prices of certain goods, the internment of people considered a danger to the war effort, the compulsory purchase of strategic goods, and the censorship of the media.<ref name=homefront/> | |||

| At the outbreak of the war there were about 35,000 people who had been born in either Germany or Austria-Hungary living in Australia.<ref>Ernest Scott, ''Australia During the War'' (7th ed. 1941) p 105 </ref> They had weak ties to Germany (and almost none to Austria) and many had enlisted in the Australian war effort. Nevertheless fears ran high and internment camps were set up where those suspected of unpatriotic acts were sent. In total 4,500 people were interned under the provisions of the ''War Precautions Act'', of which 700 were naturalised Australians and 70 Australian born. Following the end of the war, 6,150 were deported.<ref name=homefront2>{{cite web |title=Internment in Australia during WWI |publisher=anzacday.org |date= |url=http://www.anzacday.org.au/history/ww1/homefront/enemy.html |accessdate=2 May 2009}}</ref> | |||

| ====Economy==== | ====Economy==== | ||

| ], awarded to subscribers of the Australian Government's 7th War Loan in 1918]] |

], awarded to subscribers of the Australian Government's 7th War Loan in 1918]] | ||

| In 1914 the Australian economy was small but very nearly the most |

In 1914 the Australian economy was small but very nearly the most prosperous in the world per capita; it depended on the export of wool and mutton. London provided assurances that it would underwrite a large amount of the war risk insurance for shipping to allow trade amongst the Commonwealth nations to continue. London imposed controls so that no exports would wind up in German hands. The British government protected prices by buying Australian products, even though the shortage of shipping meant that there was no chance that they would ever receive them.<ref>Scott, ''Australia During the War'' (1941) p. 516–18, 539.</ref> | ||

| On the whole Australian commerce was expanded due to the war, although the cost of the war was quite considerable and the Australian government had to borrow considerably from overseas to fund the war effort. In terms of value, Australian exports rose almost 45 per cent, while the number of Australians employed in |

On the whole, Australian commerce was expanded due to the war, although the cost of the war was quite considerable and the Australian government had to borrow considerably from overseas to fund the war effort. In terms of value, Australian exports rose almost 45 per cent, while the number of Australians employed in manufacturing industries increased over 11 per cent. Iron mining and steel manufacture grew enormously.<ref>Russel Ward, ''A nation for a continent: The history of Australia, 1901–1975'' (1977) p 110</ref> Inflation became a factor as the prices of ] went up, while the cost of exports was deliberately kept lower than market value to prevent further inflationary pressures worldwide. As a result, the cost of living for many average Australians was increased.<ref>Scott, ''Australia During the War'' (1941) pp. 549, 563</ref> | ||

| The trade union movement, already powerful grew rapidly, |

The trade union movement, already powerful, grew rapidly, although the movement was split on the political question of conscription. It expelled the politicians, such as Hughes, who favoured conscription (which was never passed into law).<ref>Stuart Macintyre, ''The Oxford History of Australia: Volume 4: 1901–42, the Succeeding Age'' (1987) pp 163–75</ref> The government sought to stabilize wages, much to the anger of unionists. The average weekly wage during the war was increased by between 8 and 12 per cent, it was not enough to keep up with inflation. Angry workers launched a wave of strikes against both the wage freeze and the conscription proposal. Nevertheless, the result was very disruptive and it has been estimated that between 1914 and 1918 there were 1,945 industrial disputes, resulting in 8,533,061 working days being lost and a £4,785,607 deficit in wages.<ref>Scott, ''Australia During the War'' (1941) pp. 663–65</ref><ref>Russel Ward, ''A nation for a continent: The history of Australia, 1901–1975'' (1977) p 110–11</ref> | ||

| Overall, the war had a significantly negative impact on the |

Overall, the war had a significantly negative impact on the Australian economy. Real aggregate ] (GDP) declined by 9.5 percent over the period 1914 to 1920, while the mobilization of personnel resulted in a six percent decline in civilian employment. Meanwhile, although population growth continued during the war years, it was only half that of the prewar rate. Per capita incomes also declined sharply, failing by 16 percent.<ref>Ian W. McLean, ''Why Australia Prospered: The Shifting Sources of Economic Growth'' (2013), pp. 147–148.</ref> | ||

| ===New Zealand=== | ===New Zealand=== | ||

| The country remained an enthusiastic supporter of the Empire, |

The country remained an enthusiastic supporter of the Empire, enlisting 124,211 men and sending 100,444 to fight in World War I (see ]). Over 18,000 died in service. Conscription was introduced in mid 1916 and by the end of the war near 1 in four members of the NZEF was a conscript.<ref>Steven Loveridge, ''Calls to Arms: New Zealand Society and Commitment to the Great War'' (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2014) p.26</ref> As in Australia, involvement in the Gallipoli campaign became an iconic touchstone in New Zealand memory of the war and was commonly connected to imaginings of collective identity. | ||

| The war divided the labour movement with numerous elements taking up roles in the war effort while others alleged the war was an imperial venture against the interests of the working class. ] MPs frequently acted as critics of government policy during the war and opposition to conscription saw the modern Labour Party formed in 1916. Maori tribes that had been close to the government sent their young men to volunteer. The mobilisation of women for war work/service was relatively slight compared to more industrialised countries though some 640 women served as nurses with 500 going overseas.<ref>Gwen Parsons, "The New Zealand Home Front during World War One and World War Two," ''History Compass'' (2013) 11#6 pp 419–428</ref> | |||

| New Zealand forces captured ] from Germany in the early stages of the war, and New Zealand administered the country until Samoan Independence in 1962. However Samoans greatly resented the imperialism, and blamed inflation and the catastrophic 1918 flu epidemic on New Zealand rule.<ref>Hermann Hiery, "West Samoans between Germany and New Zealand 1914–1921," ''War and Society'' (1992) 10#1 pp 53–80.</ref> | |||

| New Zealand forces captured ] from Germany in the early stages of the war, and New Zealand administered the country until Samoan Independence in 1962. However many Samoans greatly resented the administration, and blamed inflation and the catastrophic 1918 flu epidemic on New Zealand rule.<ref>Hermann Hiery, "West Samoans between Germany and New Zealand 1914–1921," ''War and Society'' (1992) 10#1 pp 53–80.</ref> | |||

| The heroism of the soldiers in the failed Gallipoli campaign made their sacrifices iconic in New Zealand memory, and secured the psychological independence of the nation. | |||

| ===South Africa=== | ===South Africa=== | ||

| South Africa had a military role in the war, fighting the Germans in East Africa and on the Western Front.<ref>Bill Nasson, ''Springboks on the Somme: South Africa in the Great War, 1914–1918'' (2007); Anne Samson, ''Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign, 1914–1918: The Union Comes of Age'' (2006)</ref> |

South Africa had a military role in the war, fighting the Germans in East Africa and on the Western Front.<ref>Bill Nasson, ''Springboks on the Somme: South Africa in the Great War, 1914–1918'' (2007); Anne Samson, ''Britain, South Africa and the East Africa Campaign, 1914–1918: The Union Comes of Age'' (2006)</ref> Public opinion in South Africa split along racial and ethnic lines. The British elements strongly supported the war and comprised the great majority of the 146,000 white soldiers. Nasson says, "for many enthusiastic English-speaking Union recruits, going to war was anticipated as an exciting adventure, egged on by the itch of making a manly mark upon a heroic cause."<ref>Nasson, ''Springboks on the Somme'' ch 8</ref> Likewise the Indian element (led by ]), generally supported the war effort. Afrikaners were split, with some like Prime Minister ] and General ] taking a prominent leadership role in the British war effort. Their pro-British position was rejected by many rural Afrikaners who favoured Germany and who launched the ], a small-scale open revolt against the government. The trade union movement was also divided. Many urban blacks supported the war, expecting it would raise their status in society, others said it was not relevant to the struggle for their rights. The Coloured element was generally supportive and many served in a Coloured Corps in East Africa and France, also hoping to better their lot after the war. Those blacks and Coloureds who supported the war were embittered when the postwar era saw no easing of white domination and restrictive conditions.<ref>Bill Nasson, "A Great Divide: Popular Responses to the Great War in South Africa," ''War & Society'' (1994) 12#1 pp 47–64</ref> | ||

| ===India=== | ===India=== | ||

| {{Main|India in World War I}} | |||

| The British controlled India (including modern Pakistan and Bangladesh) either directly through the ] or indirectly through ]. The colonial government of India supported the war enthusiastically, and enlarged the British Indian army by a factor of 500% to 1.4 million men. It sent 550,000 overseas, with 200,000 going as labourers to the Western Front and the rest to the Middle East theatre. Only a few hundred were allowed to become officers, but there were some 100,000 casualties. The main fighting of the latter group was in Iraq, where large numbers were killed and captured in the initial stages of the ], most infamously during the ].<ref>Tucker, ''European Powers,'' pp 353–4</ref> The Indian contingent was entirely funded by the Indian taxpayers (who had no vote and no voice in the matter). | |||

| ], ] donated to the war effort, 1916.]] | |||

| The British controlled India (including modern ] and ]) either directly through the ] or indirectly through ]. The colonial government of India supported the war enthusiastically, and enlarged the ] by a factor of 500% to 1.4 million men. It sent 550,000 overseas, with 200,000 going as laborers to the Western Front and the rest to the Middle East theatre. Only a few hundred were allowed to become officers, but there were some 100,000 casualties. The main fighting of the latter group was in Mesopotamia (modern ]), where large numbers were killed and captured in the initial stages of the ], most infamously during the ].<ref>Tucker, ''European Powers,'' pp 353–4</ref> The Indian contingent was entirely funded by the Indian taxpayers (who had no vote and no voice in the matter).<ref name="online">Xu Guoqi. ''Asia and the Great War – A Shared History'' (Oxford UP) {{Dead link|date=October 2022 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| Although Germany and the Ottoman Empire tried to incite anti-British subversion with help of Indian freedom fighters, such as ] or ], they had virtually no success, apart from a localized ],<ref>Hew Strachan, ''The First World War'' (2001) 1:791-814</ref> which was a part of the ]. The small Indian industrial base expanded dramatically to provide most of the supplies and munitions for the Middle East theatre.<ref>David Stevenson, ''With Our Backs to the Wall'' (2011) pp 257–8, 381</ref> Indian nationalists became well organized for the first time during the war, and were stunned when they received little in the way of self-government in the aftermath of victory. | |||

| Although Germany and the Ottoman Empire tried to incite anti-British subversion with the help of Indian freedom fighters, such as ] or ], they had virtually no success, apart from a localized ],<ref>Hew Strachan, ''The First World War'' (2001) 1:791-814</ref> which was a part of the ]. The small Indian industrial base expanded dramatically to provide most of the supplies and munitions for the Middle East theatre.<ref>David Stevenson, ''With Our Backs to the Wall'' (2011) pp 257–8, 381</ref> Indian nationalists became well organized for the first time during the war, and were stunned when they received little in the way of self-government in the aftermath of victory. | |||

| In 1918, India experienced an influenza epidemic and severe food shortage. | |||

| In 1918, India ] and severe food shortages. | |||

| ==Belgium== | ==Belgium== | ||

| {{main|Belgium in World War I|Rape of Belgium}} | {{main|Belgium in World War I|Rape of Belgium}} | ||

| Nearly all of Belgium was occupied by the Germans, but the government and army escaped and fought the war on a narrow slice of the Western Front. The German invaders treated any resistance—such as sabotaging rail lines—as illegal and immoral, and shot the offenders and burned buildings in retaliation. The German army executed over 6,500 French and Belgian civilians between August and November 1914, usually in near-random large-scale shootings of civilians ordered by junior German officers. |

Nearly all of Belgium was occupied by the Germans, but the government and army escaped and fought the war on a narrow slice of the Western Front. The German invaders treated any resistance—such as sabotaging rail lines—as illegal and immoral, and shot the offenders and burned buildings in retaliation. The German army executed over 6,500 French and Belgian civilians between August and November 1914, usually in near-random large-scale shootings of civilians ordered by junior German officers. The German Army destroyed 15,000-20,000 buildings—most famously the university library at ] (Leuven)—and generated a refugee wave of over a million people. Over half the German regiments in Belgium were involved in major incidents.<ref>John Horne and Alan Kramer, ''German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial'' (Yale U.P. 2001) ch 1-2, esp. p. 76</ref> Thousands of workers were shipped to Germany to work in factories. British propaganda dramatizing the ] attracted much attention in the US, while Berlin said it was legal and necessary because of the threat of "franc-tireurs" (guerrillas) like those in ].<ref>Horne and Kramer, ''German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial'' ch 3-4 show there were no "franc-tireurs" in Belgium.</ref> The British and French magnified the reports and disseminated them at home and in the US, where they played a major role in dissolving support for Germany.<ref>Horne and Kramer, ''German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial'' ch 5-8</ref> | ||

| The Germans left Belgium stripped and barren. They shipped machinery to Germany while destroying factories.<ref>E.H. Kossmann. ''The Low Countries'' (1978), p 523–35</ref> |

The Germans left Belgium stripped and barren. They shipped machinery to Germany while destroying factories.<ref>E.H. Kossmann. ''The Low Countries'' (1978), p 523–35</ref> After the atrocities of the first few weeks, German civil servants took control and were generally correct, albeit strict and severe. There was no violent resistance movement, but there was a large-scale spontaneous passive resistance of a refusal to work for the benefit of German victory. Belgium was heavily industrialized; while farms operated and small shops stayed open, most large establishments shut down or drastically reduced their output. The faculty closed the universities; publishers shut down most newspapers. Most Belgians "turned the four war years into a long and extremely dull vacation", says Kiossmann.<ref>Kossmann, p 525</ref> | ||

| Neutrals led by the United States set up the Commission for Relief in Belgium, headed by American engineer ]. It shipped in large quantities of food and medical supplies, which it tried to reserve for civilians and keep out of the hands of the Germans.<ref>Johan den Hertog, "The Commission for Relief in Belgium and the Political Diplomatic History of the First World War," ''Diplomacy and Statecraft,'' (Dec 2010) 21#4 pp 593–613,</ref> |

Neutrals led by the United States set up the Commission for Relief in Belgium, headed by American engineer ]. It shipped in large quantities of food and medical supplies, which it tried to reserve for civilians and keep out of the hands of the Germans.<ref>Johan den Hertog, "The Commission for Relief in Belgium and the Political Diplomatic History of the First World War," ''Diplomacy and Statecraft,'' (Dec 2010) 21#4 pp 593–613,</ref> Many businesses collaborated with the Germans, and some women cohabitated with their men. They were treated roughly in a wave of popular violence in November and December 1918. The government set up judicial proceedings to punish the collaborators.<ref>Laurence van Ypersele and Xavier Rousseaux, "Leaving the War: Popular Violence and Judicial Repression of 'unpatriotic' behaviour in Belgium (1918–1921)," ''European Review of History'' (Spring 2005) 12#3 pp 3–22</ref> In 1919 the ] organized a new ministry and introduced universal male suffrage. The Socialists—mostly poor workers—benefited more than the more middle class Catholics and Liberals. | ||

| ===Belgian Congo=== | ===Belgian Congo=== | ||

| Rubber had long been the main export; production levels held up but its importance fell from 77% of exports (by value) to only 15%. New resources were opened, especially copper mining in ]. The British-owned Union Miniere company dominated the copper industry; it used a direct rail line to the sea at Beira. The war caused a heavy demand for copper, production soared from 997 tons in 1911 to 27,000 tons in 1917, then fell off to 19,000 tons in 1920. Smelters operated at ]; before the war copper was sold to Germany; the British purchased all the wartime output, with the revenues going to the Belgian government in exile. Diamond and gold mining expanded during the war. The British firm of Lever Brothers greatly expanded the palm oil business during the war, and there was an increased output of cocoa, rice and cotton. New rail and steamship lines opened to handle the expanded export traffic.<ref>{{Cite EB1922 |wstitle=Belgian Congo |volume=30 |page=429 |first=Frank Richardson |last=Cana}}</ref> | |||

| Rubber had long been the main export; production levels held up but its importance fell from 77% of exports (by value) to only 15%. New resources were opened, especially copper mining in Katanga province. The British-owned Union Miniere company dominated the copper industry; it used a direct rail line to the sea at Beira. The war caused a heavy demand for copper, and production soared from 997 tons in 1911 to 27,000 tons in 1917, then fell off to 19,000 tons in 1920. Smelters operate at Lubumbashi. Before the war the copper was sold to Germany; the British purchased all the wartime output, with the revenues going to the Belgian government in exile. Diamond and gold mining expanded during the war. The British firm of Lever Bros. greatly expanded the palm oil business during the war, and there was an increased output of cocoa, rice and cotton. New rail and steamship lines opened to handle the expanded export traffic.<ref>"Belgian Congo" in ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (1922 edition) </ref> | |||

| ==France== | ==France== | ||

| {{main|French Third Republic#First World War}} | {{main|French entry into World War I|French Third Republic#First World War}} | ||

| Many French intellectuals welcomed the war to avenge the humiliation of defeat and loss of territory to Germany following the ] of 1871. |

Many French intellectuals welcomed the war to avenge the humiliation of defeat and loss of territory to Germany following the ] of 1871. Only one major figure, novelist ] retained his pacifist internationalist values; he moved to Switzerland.<ref>Martha Hanna, ''The mobilization of intellect: French scholars and writers during the Great War'' (Harvard University Press, 1996)</ref> After Socialist leader ], a pacifist, was assassinated at the start of the war, the French socialist movement abandoned its antimilitarist positions and joined the national war effort. Prime Minister ] called for unity—for a "]" ("Sacred Union"); France had few dissenters.<ref>Elizabeth Greenhalgh, "Writing about France's Great War." (2005): 601-612. </ref> | ||

| However, ] was a major factor by 1917, even reaching the army, as soldiers were reluctant to attack—many threatened to mutiny—saying it was best to wait for the arrival of millions of Americans. The soldiers were protesting not just the futility of frontal assaults in the face of German machine guns but also degraded conditions at the front lines and home, especially infrequent leaves, poor food, the use of African and Asian colonials on the home front, and concerns about the welfare of their wives and children.<ref>Leonard V. Smith, "War and 'Politics': The French Army Mutinies of 1917," ''War in History,'' (April 1995) 2#2 pp 180–201</ref> | |||

| The economy was hurt by the German invasion of major industrial areas in the northeast. While the occupied area in 1913 contained only 14% of France's industrial workers, it produced 58% of the steel, and 40% of the coal.<ref>Gerd Hardach, ''The First World War: 1914–1918'' (1977) pp 87–88</ref> Considerable relief came with the influx of American food, money and raw materials in 1917.<ref>Pierre-Cyrille Hautcoeur, "Was the Great War a watershed? The economics of World War I in France," in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch 6</ref> | |||

| The industrial economy was badly hurt by the German invasion of major industrial areas in the northeast. While the occupied area in 1913 contained only 14% of France's industrial workers, it produced 58% of the steel, and 40% of the coal.<ref>Gerd Hardach, ''The First World War: 1914–1918'' (1977) pp 87–88</ref> Considerable relief came with the influx of American food, money and raw materials in 1917.<ref>Pierre-Cyrille Hautcoeur, "Was the Great War a watershed? The economics of World War I in France," in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch 6</ref> The arrival of over a million American soldiers in 1918 brought heavy spending on food and construction materials. Labor shortages were in part alleviated by the use of volunteer and slave labor from the colonies.<ref>John Horne, "Immigrant Workers in France during World War I." ''French Historical Studies'' 14.1 (1985): 57-88. </ref> | |||

| The war damages amounted to about 113% of the GDP of 1913, chiefly the destruction of productive capital and housing. The national debt rose from 66% of GDP in 1913 to 170% in 1919, reflecting the heavy use of bond issues to pay for the war. Inflation was severe, with the franc losing over half its value against the British pound.<ref>Paul Beaudry and Franck Portier, "The French depression in the 1930s." ''Review of Economic Dynamics''(2002) 5#1 pp: 73-99.</ref> | |||

| ] became prime minister in November 1917, a time of defeatism and acrimony. Italy was on the defensive, Russia had surrendered. Civilians were angry, as rations fell short and the threat of German air raids grew. Clemenceau realized his first priority was to restore civilian morale. He arrested ], a former French prime minister, for openly advocating peace negotiations. He won all-party support to fight to victory calling for "la guerre jusqu'au bout" (war until the end). | |||

| The World War ended a golden era for the press. Their younger staff members were drafted and male replacements could not be found (women were not considered). Rail transportation was rationed and less paper and ink came in, and fewer copies could be shipped out. Inflation raised the price of newsprint, which was always in short supply. The cover price went up, circulation fell and many of the 242 dailies published outside Paris closed down. The government set up the Interministerial Press Commission to closely supervise newspapers. A separate agency imposed tight censorship that led to blank spaces where news reports or editorials were disallowed. The dailies sometimes were limited to only two pages instead of the usual four, leading one satirical paper to try to report the war news in the same spirit: | |||

| : War News. A half-zeppelin threw half its bombs on half-time combatants, resulting in one-quarter damaged. The zeppelin, halfways-attacked by a portion of half-anti aircraft guns, was half destroyed."<ref>Collins, "The Business of Journalism in Provincial France during World War I," (2001)</ref> | |||

| ] became prime minister in November 1917, a time of defeatism and acrimony. Italy was on the defensive, Russia had surrendered. Civilians were angry, as rations fell short and the threat of German air raids grew. Clemenceau realized his priority was to restore civilian morale. He arrested ], a former French prime minister, for openly advocating peace negotiations. He won all-party support to fight to victory calling for "la guerre jusqu'au bout" (war until the end). | |||

| ==Russia== | ==Russia== | ||

| {{Main|Russian entry into World War I|History of Russia (1892–1917)|Russian Revolution}} | |||

| Czarist Russia was being torn apart in 1914 and was not prepared to fight a modern war.<ref>Hans Rogger, "Russia in 1914," ''Journal of Contemporary History'' (1966) 1#4 pp. 95–119 </ref> The industrial sector was small, finances were poor, the rural areas could barely feed themselves.<ref>Peter Gatrell, "Poor Russia, poor show: mobilising a backward economy for war, 1914–1917," in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch. 8</ref> Repeated military failures and bureaucratic ineptitude soon turned large segments of the population against the government. Control of the Baltic Sea by the German fleet, and of the Black Sea by combined German and Ottoman forces prevented Russia from importing supplies or exporting goods. By the middle of 1915 the impact of the war was demoralizing. Food and fuel supplies grew scarce, war casualties kept climbing and inflation was mounting. Strikes increased among low-paid factory workers, and the peasants, who wanted land reforms, were restless. Meanwhile, elite distrust of the regime was deepened when a semiliterate mystic, ], gained enormous influence over the Czar. Major strikes broke out early in 1917 and the army sided with the strikers in the ]. The czar abdicated. The liberal reformer ] came to power in July, but in the ] Lenin and the Bolsheviks took control. In early 1918 they signed the ] that made Germany dominant in Eastern Europe, while Russia plunged into years of civil war.<ref>John M. Thompson, ''Revolutionary Russia, 1917'' (1989)</ref> | |||

| Tsarist Russia was being torn apart in 1914 and was not prepared to fight a modern war.<ref>Hans Rogger, "Russia in 1914," ''Journal of Contemporary History'' (1966) 1#4 pp. 95–119 </ref> The industrial sector was small, finances were poor, the rural areas could barely feed themselves.<ref>Peter Gatrell, "Poor Russia, poor show: mobilising a backward economy for war, 1914–1917," in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch. 8</ref> Repeated military failures and bureaucratic ineptitude soon turned large segments of the population against the government. Control of the ] by the German fleet, and of the ] by combined German and Ottoman forces prevented Russia from importing supplies or exporting goods. By the middle of 1915 the impact of the war was demoralizing. Food and fuel supplies grew scarce, war casualties kept climbing and inflation was mounting. Strikes increased among low-paid factory workers, and the peasants, who wanted land reforms, were restless. Meanwhile, elite distrust of the incompetent decision making at the highest levels was deepened when a semiliterate mystic, ], gained enormous influence over the Tsar and his wife until he was assassinated in 1916. Major strikes broke out early in 1917 and the army sided with the strikers in the ]. The ] abdicated. The liberal reformer ] came to power in July, but in the ] ] and the Bolsheviks took control. In early 1918 they signed the ] that made Germany dominant in Eastern Europe, while Russia plunged into years of ].<ref>John M. Thompson, ''Revolutionary Russia, 1917'' (1989)</ref> | |||

| While the central bureaucracy was overwhelmed and under-led, Fallows shows that localities sprang into action motivated by patriotism, pragmatism, economic self-interest, and partisan politics. Food distribution was the main role of the largest network, called the "Union of Zemstvos." It also set up hospitals and refugee stations.<ref>Thomas Fallows, "Politics and the War Effort in Russia: The Union of Zemstvos and the Organization of the Food Supply, 1914–1916," ''Slavic Review'' (1978) 37#1 pp. 70–90 </ref> | While the central bureaucracy was overwhelmed and under-led, Fallows shows that localities sprang into action motivated by patriotism, pragmatism, economic self-interest, and partisan politics. Food distribution was the main role of the largest network, called the "Union of Zemstvos." It also set up hospitals and refugee stations.<ref>Thomas Fallows, "Politics and the War Effort in Russia: The Union of Zemstvos and the Organization of the Food Supply, 1914–1916," ''Slavic Review'' (1978) 37#1 pp. 70–90 </ref> | ||

| ==Italy== | ==Italy== | ||

| {{see also|History of Italy#First World War|Italy in World War I}} | {{see also|History of Italy#First World War|Italy in World War I}} | ||

| Italy decided not to honor its ] with Germany and Austria, and remained neutral. Public opinion in Italy was sharply divided, with Catholics and socialists calling for peace. However nationalists saw their opportunity to gain their "irredenta" – that is, the border regions that were controlled by Austria. The nationalists won out, and in April 1915, the Italian government secretly agreed to the ] in which Britain and France promised that if Italy would declare war on Austria it would receive its territorial rewards. The Italian army of 875,000 men was poorly led and lacked heavy artillery and machine guns. The industrial base was too small to provide adequate amounts of modern equipment, and the old-fashioned rural base did not produce much of a food surplus.<ref>Francesco Galassi and Mark Harrison, "Italy at war, 1915–1918," in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch. 9</ref> The war |

Italy decided not to honor its ] with Germany and Austria, and initially remained neutral. Public opinion in Italy was sharply divided, with Catholics and socialists calling for peace. However nationalists saw their opportunity to gain their "irredenta" – that is, the border regions that were controlled by Austria. The nationalists won out, and in April 1915, the Italian government secretly agreed to the ] in which Britain and France promised that if Italy would declare war on Austria, it would receive its territorial rewards. The Italian army of 875,000 men was poorly led and lacked heavy artillery and machine guns. The industrial base was too small to provide adequate amounts of modern equipment, and the old-fashioned rural base did not produce much of a food surplus.<ref>Francesco Galassi and Mark Harrison, "Italy at war, 1915–1918," in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch. 9</ref> The war stalemated with a dozen indecisive battles on a very narrow front along the ], where the Austrians held the high ground. In 1916, Italy declared war on Germany, which provided significant aid to the Austrians. Some 650,000 Italian soldiers died and 950,000 were wounded, while the economy required large-scale Allied funding to survive.<ref>Thomas Nelson Page, ''Italy and the world war'' (1992) </ref> | ||

| Before the war the government had ignored labor issues, but now it had to intervene to mobilize war production. With the main working-class Socialist party reluctant to support the war effort, strikes were frequent and cooperation was minimal, especially in the Socialist strongholds of Piedmont and Lombardy. The government imposed high wage scales, as well as collective bargaining and insurance schemes.<ref>Luigi Tomassini, "Industrial Mobilization and the |

Before the war the government had ignored labor issues, but now it had to intervene to mobilize war production. With the main working-class Socialist party reluctant to support the war effort, strikes were frequent and cooperation was minimal, especially in the Socialist strongholds of ] and ]. The government imposed high wage scales, as well as collective bargaining and insurance schemes.<ref>Luigi Tomassini, "Industrial Mobilization and the labor market in Italy during the First World War," ''Social History,'' (Jan 1991), 16#1 pp 59–87</ref> Many large firms expanded dramatically. For example, the workforce at the Ansaldo munitions company grew from 6,000 to 110,000 workers as it manufactured 10,900 artillery pieces, 3,800 warplanes, 95 warships and 10 million artillery shells. At Fiat the workforce grew from 4,000 to 40,000. Inflation doubled the cost of living. Industrial wages kept pace but not wages for farm workers. Discontent was high in rural areas since so many men were taken for service, industrial jobs were unavailable, wages grew slowly and inflation was just as bad.<ref>Tucker, ''European Powers in the First World War,'' p 375–76</ref> | ||

| Italy blocked serious peace negotiations, staying in the war primarily to gain new territory. The ] awarded the victorious Italian nation the Southern half of the ], ], ], and the city of ]. Italy did not receive other territories promised by the Pact of London, so this victory was considered "]". In 1922 Italy formally annexed the ] (''Possedimenti Italiani dell'Egeo''), that she had occupied during the previous war with Turkey. | Italy blocked serious peace negotiations, staying in the war primarily to gain new territory. The ] awarded the victorious Italian nation the Southern half of the ], ], ], and the city of ]. Italy did not receive other territories promised by the Pact of London, so this victory was considered "]". In 1922 Italy formally annexed the ] (''Possedimenti Italiani dell'Egeo''), that she had occupied during the previous war with Turkey. | ||

| ==United States== | ==United States== | ||

| {{main|United States home front during World War I}} | {{main|United States home front during World War I|American entry into World War I|}} | ||

| President ] took full control of foreign policy, declaring neutrality but warning Germany that resumption of ] against American ships would mean war. Wilson's mediation efforts failed; likewise the peace efforts sponsored by industrialist ] went nowhere. Germany decided to take the risk and try to win by cutting off Britain; the |

President ] took full control of foreign policy, declaring neutrality but warning Germany that the resumption of ] against American ships would mean war. Wilson's mediation efforts failed; likewise, the peace efforts sponsored by industrialist ] went nowhere. Germany decided to take the risk and try to win by cutting off Britain; the US declared war in April 1917. America had the largest industrial, financial and agricultural base of any of the great powers, but it took 12–18 months to fully reorient it to the war effort.<ref>Hugh Rockoff, "Until it's over, over there: the US economy in World War I," in Broadberry and Harrison, eds. ''The Economics of World War I'' (2005) ch 10</ref> American money, food and munitions flowed freely to Europe from spring 1917, but troops arrived slowly. The US Army in 1917 was small and poorly equipped. | ||

| ]]] | |||

| The draft began in spring 1917 but volunteers were also accepted. Four million men and thousands of women joined the services for the duration.<ref>John W. Chambers, II, ''To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America'' (1987)</ref> By summer 1918 American soldiers under General ] arrived in France at the rate of 10,000 a day, while Germany was unable to replace its losses.<ref>Edward M. Coffman, ''The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I'' (1998)</ref> The result was an Allied victory in November 1918. | |||

| Propaganda campaigns directed by the government shaped the public mood toward patriotism and voluntary purchases of war bonds. The ] (CPI) controlled war information and |

Propaganda campaigns directed by the government shaped the public mood toward patriotism and voluntary purchases of war bonds. The ] (CPI) controlled war information and provided pro-war propaganda, with the assistance of the private ] and tens of thousands of local speakers. The ] criminalized any expression of opinion that used "disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive language" about the US government, flag or armed forces. The most prominent opponents of the war were ] and ], many of whom were convicted of deliberately impeding the war effort and were sentenced to prison, including the Socialist presidential candidate ].<ref>Ronald Schaffer, ''The United States in World War I'' (1978)</ref> | ||

| Wilson played the central role in defining the Allied war aims in 1917–1918 (although the |

Woodrow Wilson played the central role in defining the Allied war aims in 1917–1918 (although the US never officially joined the Allies). He demanded Germany depose the ] and accept the terms of his ]. Wilson dominated the ] but Germany was treated harshly by the Allies in the ] (1919) as Wilson put all his hopes in the new ]. Wilson refused to compromise with ] ] over the issue of Congressional power to declare war, and the Senate rejected the Treaty and the League.<ref>John Milton Cooper, ''Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations'' (2001)</ref> | ||

| ==Germany== | ==Germany== | ||

| {{main|History of Germany during World War I}} | {{main|History of Germany during World War I| German entry into World War I }} | ||

| By 1915 the British naval blockade had cut off food imports and conditions deteriorated rapidly on the home front, with severe food shortages reported in all urban areas. The causes included the transfer of so many farmers and food workers into the military, combined with the overburdened railroad system, a shortage of coal, and the ] that cut off imports from abroad.<ref>{{cite chapter |last=Albrecht |first=Ritschl |authorlink=Albrecht Ritschl (economist) |chapter=The pity of peace: Germany's economy at war, 1914–1918 and beyond |editor-last1=Broadberry |editor-last2=Harrison |title=The Economics of World War I |year=2005}}</ref> The winter of 1916–1917 was known as the "turnip winter" (]), because that vegetable, which was usually fed to livestock, was used by people as a substitute for potatoes and meat, which were increasingly scarce. Thousands of ]s were opened to feed the hungry people, who grumbled that the farmers were keeping the food for themselves. Even ] had to cut the rations for soldiers.<ref>Roger Chickering, ''Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914–1918'' (2004) p. 141–42</ref> Compared to peacetime, about 474,000 additional civilians died, chiefly because malnutrition had weakened the body.<ref>N.P. Howard, "The Social and Political Consequences of the Allied Food Blockade of Germany, 1918–19," ''German History'' (1993) 11#2 pp 161–88 table p 166, with 271,000 excess deaths in 1918 and 71,000 in 1919.</ref> | |||

| According to historian ]: | |||

| :By 1917, after three years of war, the various groups and bureaucratic hierarchies which had been operating more or less independently of one another in peacetime (and not infrequently had worked at cross purposes) were subordinated to one (and perhaps the most effective) of their number: the General Staff. Military officers controlled civilian government officials, the staffs of banks, cartels, firms, and factories, engineers and scientists, workingmen, farmers-indeed almost every element in German society; and all efforts were directed in theory and in large degree also in practice to forwarding the war effort.<ref>William H. McNeill, ''The Rise of the West'' (1991 edition) p. 742.</ref> | |||

| Morale of both civilians and soldiers continued to sink, but using the slogan of "sharing scarcity", the German bureaucracy ran an efficient rationing system nevertheless.<ref>Keith Allen, "Sharing scarcity: Bread rationing and the First World War in Berlin, 1914–1923," ], (Winter 1998) 32#2 pp 371–93 </ref> | |||

| ===Political revolution=== | ===Political revolution=== | ||

| The end of October 1918 saw the outbreak of the ] as units of the German Navy refused to set sail for a last, large-scale operation in a war which they saw as good as lost. By 3 November, the revolt spread to other cities and states of the country, in many of which workers' and soldiers' councils were established. Meanwhile, Hindenburg and the senior commanders had lost confidence in |