| Revision as of 08:12, 6 February 2015 editMilktaco (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users30,723 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:20, 20 December 2024 edit undoYuanmongolempiredynasty (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users633 editsNo edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Mongol-led dynasty of China (1271–1368)}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{pp-move|small=yes}} | |||

| {{refimprove|date=December 2013}} | |||

| {{pp-pc}} | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=August 2017}} | |||

| {{Infobox Former Country | |||

| {{use British English|date=August 2017}} | |||

| |native_name = 大元<br />] | |||

| {{Infobox former country | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Great Yuan | |||

| | native_name = {{native name list|tag1=zh|name1=大元|tag2=zh-Latn|name2=Dà Yuán|tag3=mn|name3={{lower|0.2em|{{MongolUnicode|ᠳᠠᠢ ᠦᠨ <br>ᠤᠯᠤᠰ}}}}|tag4=mn-Latn|name4=Dai Ön ulus|paren1=omit|paren3=omit}}<ref>{{cite web | editor1= Walter Koh |title=China under Mongol Rule: The Yuan dynasty |url=http://www.chinasymposium.com/articles/History/History_Chapter_Eight.pdf | work = China Symposium| date = 2014}}</ref> | |||

| |common_name = Yuan dynasty | |||

| | conventional_long_name = Great Yuan | |||

| |image_flag = | |||

| | common_name = Yuan dynasty | |||

| |flag = | |||

| | life_span = 1271–1368 | |||

| |flag_type = | |||

| | era = ] | |||

| |continent = Asia | |||

| | status = ]-ruled ] of the ]{{NoteTag|name=GreatYuan}}<br />] of ] | |||

| |region = Eastern Asia | |||

| | |

| empire = Mongol Empire | ||

| | government_type = ] | |||

| |status = ] ]<br />] ] | |||

| | year_start = 1271 | |||

| |status_text = | |||

| | year_end = 1368 | |||

| |empire = Mongol Empire | |||

| | event_start = Kublai's proclamation of the dynastic name "Great Yuan"<ref name="Proclamation1271" /> | |||

| |government_type = ] | |||

| | date_start = 5 November | |||

| |year_start = 1271 | |||

| | event_end = Fall of ] | |||

| |year_end = 1368 | |||

| | |

| date_end = 14 September | ||

| | event_pre = ] proclaimed Emperor{{NoteTag|name=Emperor}} | |||

| |date_start = 18 December 1271 | |||

| | |

| date_pre = 5 May 1260 | ||

| | |

| event1 = ] | ||

| | |

| date_event1 = 1268–1273 | ||

| | |

| event2 = ] | ||

| | |

| date_event2 = 4 February 1276 | ||

| | |

| event3 = ] | ||

| | |

| date_event3 = 19 March 1279 | ||

| | |

| event4 = ] | ||

| | |

| date_event4 = 1351–1368 | ||

| | |

| event_post = Formation of ] | ||

| | |

| date_post = 1368–1388 | ||

| | |

| p1 = Mongol Empire | ||

| | |

| p2 = Song dynasty | ||

| | |

| s1 = Northern Yuan | ||

| | |

| s2 = Ming dynasty | ||

| | |

| s3 = Phagmodrupa dynasty | ||

| | |

| image_map = Yuan Dynasty revised.png | ||

| | image_map_caption = Yuan dynasty ({{circa|1290}}){{NoteTag|name=goryeo|The precise status of ] is unclear. While Goryeo was a vassal of the Yuan dynasty, many scholars, such as ], regard it as an autonomous state outside the Yuan territory;<ref name=tan>{{cite book |language=zh-Hans |script-title = zh:《中国历史地图集》 |trans-title = The Historical Atlas of China |title-link = The Historical Atlas of China |publisher=] |at= |author1-link = Tan Qixiang |author1=Tan Qixiang |display-authors = etal |isbn=978-7-5031-1844-9 |year=1987}}</ref>{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|pp=436–437}}{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=77}} others regard it as an integral part of the Yuan territory.}} | |||

| |flag_p2 = | |||

| | |

| capital = {{ubl|] (now ])|] (summer capital)}} | ||

| | common_languages = {{ubl|]|] (])|]}} | |||

| |flag_p3 = | |||

| | |

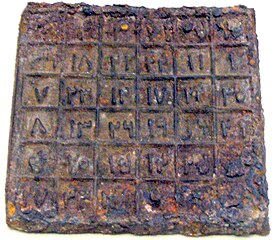

| languages_type = Official script | ||

| | languages = ]<ref>{{cite web |title='Phags-pa Script: Description|url=https://www.babelstone.co.uk/Phags-pa/Description.html|date=21 December 2006|access-date=22 April 2023 | editor1= Andrew West | work = BabelStone }}</ref> | |||

| |flag_p4 = | |||

| | religion = ] (] as ''de facto'' ]), ], ], ], Mongolian ]/Chinese ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| |p5 = | |||

| | currency = ] banknotes, ] | |||

| |flag_p5 = | |||

| | |

| leader1 = ] (first) | ||

| | |

| leader2 = ] (last) | ||

| | |

| year_leader1 = 1260–1294 | ||

| | |

| year_leader2 = 1332–1368 | ||

| | title_leader = ]{{NoteTag|name=Emperor|Since the enthronement of ] ({{zhi|c=成吉思皇帝|p=Chéngjísī huángdì}}) in Spring 1206.<ref name="Enthronement1206">{{cite book |script-title = zh:《元史》 |trans-title = ] |language=zh-Classical | orig-date= 1370 | |||

| |image_s2 = | |||

| | date = 1976 | publisher= Zhonghua Shuju | place= Beijing | |||

| |s3 = | |||

| | author1= Song Lian | author1-link= Song Lian | |||

| |flag_s3 = | |||

| |chapter=] ]] |quote=元年丙寅,帝大會諸王群臣,建],即皇帝位於斡難河之源。諸王群臣共上尊號曰{{strong|{{serif|{{nowrap|成吉思}}皇帝}}}}。"<br />"In ], on the '']'' day, the emperor greatly assembled the many princes and numerous vassals, and erected his nine-tailed white ], assuming the position of ] at the source of the ]. And the many princes and numerous vassals together bestowed upon him the reverent title {{aut|Genghis Huangdi}}. }}</ref> Decades before ] announced the dynastic name "Great Yuan" in 1271, the "Great Mongol State" (''Yeke Mongγol Ulus'') already used the ]-style title of ] ({{zh |c = 皇帝 |p = Huángdì }}) to translate title ] ({{zh |c = 合罕 |p = Héhàn }}, ''Great Khan'') in ].<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| |s4 = | |||

| |author1=Yang Fuxue (杨富学) |script-title=zh:回鹘文献所见蒙古"合罕"称号之使用范围 |date=1997 |publisher=甘肃敦煌研究院 |trans-title=The scope of use of Mongolian "Khagan" title found in Old Uyghur literature |journal=内蒙古社会科学 |issue=5|s2cid=224535800 }}</ref> Although Kublai Khan announced that he inherited the Mongol throne, ] broke out due to opposition from other Mongols.}} | |||

| |flag_s4 = | |||

| | |

| deputy1 = ] | ||

| | |

| deputy2 = ] | ||

| | |

| year_deputy1 = 1264–1282 | ||

| | |

| year_deputy2 = 1340–1355 | ||

| | title_deputy = ] | |||

| |symbol_type = | |||

| | |

| stat_year1 = 1310 | ||

| | stat_area1 = 11000000 | |||

| |image_map_caption = Yuan dynasty in 1294 | |||

| | ref_area1 = <ref>{{cite journal |date=September 1997 |title=Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia |journal=] |volume=41 |issue=3 |page=499 |doi=10.1111/0020-8833.00053 |first=Rein |last=Taagepera |author-link = Rein Taagepera |jstor=2600793 |url=https://escholarship.org/content/qt3cn68807/qt3cn68807.pdf?t=otc3in}}</ref> | |||

| |capital = ] (]) | |||

| |capital_exile = | |||

| |latd = 39 |latm = 54 |latNS = N |longd = 116 |longm = 23 |longEW = | |||

| | | |||

| |national_motto = | |||

| |national_anthem = | |||

| |common_languages = ]<br />] | |||

| |religion = ] - ] and ]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />] | |||

| |currency = Predominantly ] (]), with a small amount of ] in use | |||

| | | |||

| |leader1 = Kublai Khan | |||

| |leader2 = Ukhaatu Khan | |||

| |year_leader1 = 1260–1294 | |||

| |year_leader2 = 1333–1370 (Cont.) | |||

| |leader_pre = Genghis Khan | |||

| |year_leader_pre = 1206–1227 | |||

| |title_leader = ] | |||

| |stat_year1 = 1290 | |||

| |stat_area1 = | |||

| |stat_pop1 = 77000000 | |||

| |title_deputy = ] | |||

| |legislature = | |||

| |stat_year2 = 1293 | |||

| |stat_area2 = | |||

| |stat_pop2 = 79816000 | |||

| |stat_year3 = 1310 | |||

| |stat_area3 = 14000000 | |||

| |stat_pop3 = | |||

| |stat_year4 = 1330 | |||

| |stat_area4 = | |||

| |stat_pop4 = 83873000 | |||

| |stat_year5 = 1350 | |||

| |stat_area5 = | |||

| |stat_pop5 = 87147000 | |||

| |today = {{Flag|Mongolia}}<br />{{Flag|China}}<br /> {{Flag|Hong Kong}}<br /> {{Flag|Macau}}<br />{{Flag|India}}<br />{{Flag|North Korea}}<br />{{Flag|South Korea}}<br />{{Flag|Laos}}<br />{{Flag|Myanmar}}<br />{{Flag|Russia}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| |c = {{linktext|元|朝}} | |||

| |p = Yuán Cháo | |||

| |w = Yuan<sup>2</sup> Ch'ao<sup>2</sup> | |||

| |mon = Их Юань улс | |||

| |mong = ] | |||

| |monr = Ikh Yuanʹ Üls | |||

| }} | |||

| {{special characters}} | |||

| {{History of Mongolia}} | {{History of Mongolia}} | ||

| {{History of China}} | {{History of China}} | ||

| The '''Yuan dynasty''' ({{zh |c={{linktext|元|朝}} |p=Yuáncháo }}), officially the '''Great Yuan'''<ref name="CivilSociety" /> ({{zh |c={{linktext|大|元}} |p=Dà Yuán }}; ]: {{MongolUnicode|ᠶᠡᠬᠡ<br />ᠶᠤᠸᠠᠨ<br />ᠤᠯᠤᠰ}}, {{lang|mn-Latn|Yeke Yuwan Ulus}}, literally "Great Yuan State"),{{NoteTag|Modern ] form commonly used by Chinese and Mongolian academics: {{langx|xng|{{MongolUnicode|ᠳᠠᠢ<br />ᠦᠨ<br />ᠶᠡᠬᠡ<br />ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ<br />ᠤᠯᠤᠰ}}}}, {{lang|mn-Latn|Dai Ön Yeke Mongghul Ulus}} or {{lang|mn|Их Юань улс}} in Modern ], ''{{transliteration|mn|Ikh Yuan Üls/Yekhe Yuan Ulus}}''.<ref>{{cite web |title=ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠤᠨ ᠶᠡᠬᠡ ᠶᠤᠸᠠᠨ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ |url=https://mongoltoli.mn/history/h/418 |publisher=Монголын түүхийн тайлбар толь |year=2016 | language=mn}}</ref>}} was a ]-led ] and a ] to the ] after ].{{NoteTag|name=GreatYuan|As per modern historiographical norm, the "Yuan dynasty" in this article refers exclusively to the realm based in ] (present-day ]). However, the ]-style dynastic name "Great Yuan" ({{lang|zh-Hant|大元}}) as proclaimed by Kublai in 1271, as well as the claim to Chinese political orthodoxy were meant to be applied to the entire ].<ref name="Proclamation1271" /><ref name="GreatYuan1" /> In spite of this, "Yuan dynasty" is rarely used in the broad sense of the definition by modern scholars due to the ] of the Mongol Empire.}} It was established by ] (Emperor Shizu or Setsen Khan), the fifth khagan-emperor of the Mongol Empire from the ] clan, and lasted from 1271 to 1368. In ], the Yuan dynasty followed the ] and preceded the ]. | |||

| Although ]'s enthronement as ] in 1206 was described in ] as the ]-style title of ]{{NoteTag|name=Emperor}}<ref name="Enthronement1206" /> and the ] had ruled territories including modern-day ] for decades, it was not until 1271 that Kublai Khan officially proclaimed the dynasty in the traditional Han style,{{sfn|Mote|1994|p=624}} and the conquest was not complete until 1279 when the Southern Song dynasty was defeated in the ]. His realm was, by this point, isolated from the other Mongol-led khanates and controlled most of modern-day ] and its surrounding areas, including modern-day ].<ref name="Mongol Empire p.611">{{cite book |last=Atwood |first=Christopher Pratt |title=Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire |url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofmo0000atwo |url-access=registration |year=2004 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-8160-4671-3}}</ref> It was the first dynasty founded by a non-Han ethnicity that ruled all of ].<ref name="San" />{{rp|312}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Eberhard |first1=Wolfram |title=A History of China |date=1971 |publisher=University of California Press |location=Berkeley, California |isbn=0-520-01518-5 |page=232 |edition=3rd}}{{pn|date=July 2023}}</ref> In 1368, following the defeat of the Yuan forces by the Ming dynasty, the Genghisid rulers retreated to the ] and continued to rule until 1635 when they surrendered to the ] (which later evolved into the ]). The ] is known in ] as the ]. | |||

| After the division of the Mongol Empire, the Yuan dynasty was the khanate ruled by the successors of ]. In official Chinese histories, the Yuan dynasty bore the ]. The dynasty was established by Kublai Khan, yet he placed his grandfather Genghis Khan on the imperial records as the official founder of the dynasty and accorded him the ] Taizu.{{NoteTag|name=Emperor}} In the edict titled ''Proclamation of the Dynastic Name'' issued in 1271,<ref name="Proclamation1271" /> Kublai announced the name of the new dynasty as Great Yuan and claimed the succession of former Chinese dynasties from the ] to the ].<ref name="Proclamation1271" /> Some of the Yuan emperors mastered the ], while others only used their native ], written with the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Franke |first=Herbert |title=Could the Mongol emperors read and write Chinese? | pages = 28–41 | url = https://www2.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/file/1665DFfIcjI.pdf | journal= Asia Major | date= 1953 | series= Second series | volume= 3 | issue= 1 | publisher= Academica Sinica }}</ref> | |||

| The Yuan is considered both a successor to the ] and as an imperial ]. In ], the Yuan dynasty bore the ], following the ] and preceding the ]. Although the dynasty was established by ], he placed his grandfather ] on the imperial records as the official founder of the dynasty as ]. | |||

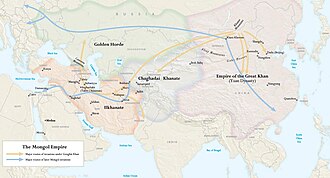

| Kublai, as a ] (Great Khan) of the Mongol Empire from 1260, had claimed supremacy over the other successor Mongol khanates: the ], the ], and the ], before proclaiming as the ] in 1271. As such, the Yuan was also sometimes referred to as the '''Empire of the Great Khan'''. However, even though the claim of supremacy by the Yuan emperors was recognized by the western khans in 1304, their subservience was nominal and each continued its own separate development.<ref>{{cite book |first=John Joseph |last=Saunders |title=The History of the Mongol Conquests |page=116 |orig-year=1971 |year=2001 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |isbn=978-0-8122-1766-7 |author-link=J. J. Saunders }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Grousset |first=René |author-link=René Grousset |year=1939 |language=fr |title=L'empire des steppes: Attila, Gengis-Khan, Tamerlan |trans-title=The Empire of Steppes}}</ref>{{pn|date=July 2023}} | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| {{See also|Names of China|Mongol Empire}} | |||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| | pic = Yuan dynasty (Chinese and Mongolian).svg | |||

| | piccap = "Yuan dynasty" in ] (top) and "Great Yuan State" (''Yehe Yüan Ulus'', a modern form) in ] (bottom) | |||

| | picsize = 145 | |||

| | c = 元朝 | |||

| | l = "Yuan dynasty" | |||

| | p = Yuán cháo | |||

| | w = Yüan<sup>2</sup> ch‘ao<sup>2</sup> | |||

| | mi = {{IPAc-cmn|yuan|2|-|ch|ao|2}} | |||

| | suz = Nyœ́ záu | |||

| | y = Yùhn chìuh | |||

| | ci = {{IPAc-yue|j|yun|4|-|c|iu|4}} | |||

| | j = Jyun4 ciu4 | |||

| | tl = Guân tiâo | |||

| | altname = Dynastic name | |||

| | c2 = 大元 | |||

| | l2 = Great Yuan | |||

| | p2 = Dà Yuán | |||

| | ci2 = {{IPAc-yue|d|aai|6|-|j|yun|4}} | |||

| | altname3 = Alternative official full name:<br />{{MongolUnicode|ᠳᠠᠢ<br />ᠶᠤᠸᠠᠨ<br />ᠶᠡᠬᠡ<br />ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ<br />ᠤᠯᠤᠰ}}<br /> {{lang|mn-Latn|Dai Yuwan Yeqe Mongɣul Ulus}} | |||

| | t3 = 大元大蒙古國 | |||

| | s3 = 大元大蒙古国 | |||

| | p3 = Dà Yuán Dà Měnggǔ Guó | |||

| | l3 = "Great Yuan" (Middle Mongol transliteration of Chinese "Dà Yuán") Great Mongol State | |||

| | bpmf = ㄩㄢˊ ㄔㄠˊ | |||

| | tp = Yuán cháo | |||

| | tp2 = Dà Yuán | |||

| | w2 = {{tone superscript|Ta4 Yüan2}} | |||

| | j2 = daai6 jyun4 | |||

| | mi2 = {{IPAc-cmn|d|a|4|-|yuan|2}} | |||

| | bpmf2 = ㄉㄚˋ ㄩㄢˊ | |||

| | tp3 = Dà Yuán Dà Měng-gǔ Guó | |||

| | w3 = {{tone superscript|Ta4 Yüan2 Ta4 Meng3-ku3 Kuo2}} | |||

| | mi3 = {{IPAc-cmn|d|a|4|-|yuan|2|-|d|a|4|-|m|eng|3|.|g|u|3|-|g|uo|2}} | |||

| | bpmf3 = ㄉㄚˋ ㄩㄢˊ ㄉㄚˋ ㄇㄥˇ ㄍㄨˇ ㄍㄨㄛˊ | |||

| }} | |||

| {{special characters}} | |||

| In 1271, ] imposed the name '''Great Yuan''' ({{zh|c=大元|p=Dà Yuán}}), establishing the Yuan dynasty.<ref name="CivilSociety">{{cite book |last=Simon |first=Karla W. |title=Civil Society in China: The Legal Framework from Ancient Times to the 'New Reform Era' |date=26 April 2013 |publisher=Oxford University Press | isbn = 9780190297640 |page=39 {{nowrap|n. 69}} |doi=10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199765898.003.0002}}</ref> "Dà Yuán" ({{lang|zh|大元}}) is derived from a clause "{{lang|zh|大哉乾元}}" ({{zhi|p=dà zāi Qián Yuán |l=Great is Qián, the Primal }}) in the ''] on the ]'' section<ref>{{cite book |language=zh-Hant |script-title=zh:《易傳》 |trans-title=] on the I Ching |section=] |quote=《彖》曰:{{nowrap|{{strong|{{serif|大哉乾元}}}}}},萬物資始,乃統天。}}</ref> regarding the ] ({{lang|zh|乾}}).<ref name="Proclamation1271">{{citation |author=Kublai Emperor |author-link=Kublai Khan |date=18 December 1271 |language=zh-Classical |script-title=zh:《建國號詔》 |trans-title=Edict to Establish the Name of the State |series=《元典章》 |url=http://zh.wikisource.org/建國號詔}}</ref> The ] counterpart was {{transl|mn|Dai Ön Ulus}}, also rendered as {{transl|mn|Ikh Yuan Üls}} or {{transl|mn|Yekhe Yuan Ulus}}. In Mongolian, {{transl|mn|Dai Ön}} a borrowing from Chinese, was often used in conjunction with the "Yeke Mongghul Ulus" ({{lang|zh-Hant|大蒙古國}}; 'Great Mongol State'), which resulted in the form {{MongolUnicode|ᠳᠠᠢ<br />ᠥᠨ<br />ᠶᠡᠬᠡ<br />ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ<br />ᠤᠯᠤᠰ}} ({{lang|zh-Hant|大元大蒙古國}}; {{lang|mn-Latn|Dai Ön Yeqe Mongɣul Ulus}}, lit. "Great Yuan {{en dash}} Great Mongol State")<ref name="mname">{{ cite book | title= The Early Mongols Language, Culture and History | series= Studies in Honor of Igor de Rachewiltz on the Occasion of his 80th Birthday | |||

| == Name == | |||

| | editor1= Volker Rybatzki | editor2= Alessandra Pozzi | editor3= Peter W. Geier | editor4= John R. Krueger | isbn = 9780933070578 | |||

| {{Main|Names of China}} | |||

| | publisher= Indiana University Press | date=2009 | page=116}}</ref> or {{MongolUnicode|ᠳᠠᠢ ᠦᠨ<br /> ᠺᠡᠮᠡᠺᠦ<br /> ᠶᠡᠬᠡ<br /> ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ<br /> ᠤᠯᠤᠰ}} ({{lang|mn-Latn|Dai Ön qemeqü Yeqe Mongɣol Ulus}}, lit. "Great Mongol State called Great Yuan").<ref>{{cite journal |author=陈得芝 |date=2009 |title=关于元朝的国号、年代与疆域问题 |journal=北方民族大学学报 |volume=87 |issue=3}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Hodong Kim |date=2015 |title=Was 'da Yuan' a Chinese Dynasty? |journal=Journal of Song-Yuan Studies |volume=45 |page=288}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author= Francis Woodman Cleaves |date=1949 |title=The Sino-Mongolian Inscription of 1362 in Memory of Prince Hindu |journal=Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies |volume=12 |page=8}}</ref> | |||

| As per contemporary historiographical norm, "Yuan dynasty" typically refers to the realm with its main capital in ] (modern-day ]). However, the ]-style dynastic name "Great Yuan" and the claim to Chinese political orthodoxy were meant for the entire Mongol Empire when the dynasty was proclaimed.<ref name="Proclamation1271" /><ref name="GreatYuan1">{{cite book |last=Robinson |first=David |title=In the Shadow of the Mongol Empire: Ming China and Eurasia |year=2019 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=itKyDwAAQBAJ&q=great+yuan+entire+mongol+empire&pg=PA50 |page=50 |isbn=978-1-108-48244-8 | publisher= Cambridge University Press}}{{pb}}{{cite book |last=Robinson |first=David |title=Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia Under the Mongols |year=2009 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PDjWpqU55eMC&q=great+yuan+refer+to+entire+mongol+empire&pg=PA293 |page=293 |isbn=978-0-674-03608-6 | series = Harvard–Yenching Institute Monograph Series 68 Studies in East Asian Law | publisher= Brill}}{{pb}}{{cite book |editor1-last=Brook |editor1-first=Timothy |editor2-last=Walt van Praag |editor2-first=Michael van |editor3-last=Boltjes |editor3-first=Miek |title=Sacred Mandates: Asian International Relations since Chinggis Khan |year=2018 | pages= 45–56 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6p1WDwAAQBAJ&q=great+yuan+refer+to+entire+mongol+empire&pg=PA45 |isbn=978-0-226-56293-3 | |||

| The Yuan Emperors equated their state with the concept of '''China'''(中國) like other non-Han dynasties did such as the Jin.<ref>, p. 7.</ref> Non-Han rulers expanded the definition of "China" to include non-Han peoples in addition to Han people, whenever they ruled China.<ref>, p. 6.</ref> Yuan, Jin, and Northern Wei documents indicate the usage of "China" by dynasties to refer to themselves began earlier than previously thought.<ref>, p. 24.</ref> | |||

| | author= Hodong Kim | chapter = Mongol Perceptions of "China" and the Yuan Dynasty | publisher= University of Chicago Press | |||

| }} At p. 45.</ref> This usage is seen in the writings, including non-Chinese texts, produced during the time of the Yuan dynasty.<ref name="GreatYuan1" /> In spite of this, "Yuan dynasty" is not commonly used in the broad sense of the definition by modern scholars due to the ]. Some scholars believe that 1260 was the year that the Yuan dynasty emerged with the proclamation of a ] following the collapse of the unified Mongol Empire.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hodong Kim |date=2015 |title=Was 'da Yuan' a Chinese Dynasty? |journal=Journal of Song-Yuan Studies |volume=45 |pages=279–280|doi=10.1353/sys.2015.0007 }}</ref> | |||

| The Yuan dynasty is sometimes also called the "Mongol dynasty" by westerners,<ref>{{ cite book| title = Archaeology of Asia | editor=Miriam T. Stark | |||

| In 1217 a Chinese title, Da Chao (大朝; Wade Giles: Ta-ch'ao ; English: "Great Dynasty") was adopted by Genghis Khan to refer to the Mongol state, alongside Da Menggu Guo (大蒙古國 ; Wade Giles: Ta Meng-ku kuo), the Chinese translation of the Mongol name "Yeke Mongghol Ulus" (The Great Mongolian State), until Kublai Khan imposed the new name Da Yuan (大元; Wade–Giles: Ta-Yüan).<ref>, p. 255.</ref> | |||

| | date= 2006 | isbn =9780470774670 | doi= 10.1002/9780470774670.ch12 | publisher= Wiley Blackwell | chapter = States on Horseback: The Rise of Inner Asian Confederations and Empires | pages= 255–278 | |||

| | author1=William Honeychurch | author2= Chunag Amartuvshin}}</ref>{{rp|269}} akin to the ] sometimes being referred to as the "Manchu dynasty"<ref>{{ cite journal | |||

| | title= Civil Administration at the Beginning of the Manchu Dynasty: A note on the establishment of the Six Ministries (Liu-pu) | |||

| | author= Piero Corradini | jstor= 43382329 | |||

| | journal=Oriens Extremus | volume= 9 | number= 2 | date= 1962 | pages= 133–138 | |||

| | publisher= Harrassowitz Verlag }}</ref> or "Manchu Dynasty of China".<ref>{{ cite journal| title= Reviewed Work: ''Central Asia''. Gavin Hambly | author= Elizabeth E. Bacon | |||

| | journal=American Journal of Sociology | |||

| | volume= 77 | number= 2 | date=September 1971 | pages= 364–366 | type= book review | |||

| | publisher= University of Chicago Press | |||

| | doi= 10.1086/225131 | |||

| |jstor =2776897}}</ref>{{rp|365}} Furthermore, the Yuan is sometimes known as the "Empire of the Great Khan" or "Khanate of the Great Khan",<ref>{{ cite book | |||

| | doi = 10.1163/9789047410812_005 | |||

| | isbn = 9789047410812 | |||

| | chapter= The First Globalization Episode: The Creation of the Mongol Empire, or the Economics of Chinggis Khan | |||

| | author1= Ronald Findlay | author2= Mats Lundahl | title= Asia and Europe in Globalization | pages=13–54 | |||

| | editor1=Göran Therborn | editor2= Habibul Khondker | date= 2006 | publisher= Brill}}</ref>{{rp|48}} since Yuan emperors held the nominal title of ]; these appeared on some Yuan maps. However, both terms can also refer to the khanate within the Mongol Empire directly ruled by Great Khans before the actual establishment of the Yuan dynasty by Kublai Khan in 1271. | |||

| == |

==History== | ||

| {{Main|History of the Yuan dynasty}} | {{Main|History of the Yuan dynasty}} | ||

| {{For timeline}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Mongol conquests}} | |||

| ===Kublai Khan's rise === | |||

| {{Division of the Mongol Empire}} | |||

| {{Main|Toluid Civil War}} | |||

| ===Background=== | |||

| Genghis Khan united the Mongol and Turkic tribes of the steppes and became ] in 1206.{{sfn|Ebrey|2010|p=169}} He and his successors expanded the Mongol empire across Asia. Under the reign of Genghis' third son, ], the Mongols ] the weakened ] in 1234, conquering most of ].{{sfn|Ebrey|2010|pp=169–170}} Ögedei offered his nephew Kublai a position in Xingzhou, ]. Kublai was unable to read Chinese, but had several Han Chinese teachers attached to him since his early years by his mother ]. He sought the counsel of Chinese Buddhist and Confucian advisers.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=415}} ] succeeded Ögedei's son, ], as Great Khan in 1251.{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=392}} He granted his brother Kublai control over Mongol held territories in China.{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=394}} Kublai built schools for Confucian scholars, issued ], revived Chinese rituals, and endorsed policies that stimulated agricultural and commercial growth.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=418}} He made the city of Kaiping in ], later renamed ], his capital.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=65}} | |||

| {{Main|Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty|Division of the Mongol Empire|Toluid Civil War|Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty}} | |||

| ] united the Mongol tribes of the steppes and became ] in 1206.{{sfn|Ebrey|2010|p=169}} He and his successors expanded the Mongol empire across Asia. Under the reign of Genghis' third son, ], the Mongols ] the weakened ] in 1234, conquering most of ].{{sfn|Ebrey|2010|pp=169–170}} Ögedei offered his nephew Kublai a position in ], ]. Kublai was unable to read Chinese but had several Han teachers attached to him since his early years by his mother ]. He sought the counsel of Chinese Buddhist and Confucian advisers.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=415}} ] succeeded Ögedei's son, ], as Great Khan in 1251.{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=392}} He granted his brother Kublai control over Mongol held territories in China.{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=394}} Kublai built schools for Confucian scholars, issued ], revived Chinese rituals, and endorsed policies that stimulated agricultural and commercial growth.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=418}} He adopted as his capital city Kaiping in ], later renamed ].{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=65}} | |||

| Möngke Khan commenced a military campaign against the Chinese ] in southern China.{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=410}} He died in 1259 without a successor.{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=411}} Kublai returned from fighting the Song in 1260 when he learned that his brother, ], was challenging his claim to the throne.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=422}} Kublai convened a kurultai in the Chinese city of ] that elected him Great Khan.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=51}} A rival kurultai in Mongolia proclaimed Ariq Böke Great Khan, beginning a civil war.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=53}} Kublai Khan depended on the cooperation of his Chinese subjects to ensure that his army received ample resources. He bolstered his popularity among his subjects by modeling his government on the bureaucracy of traditional Chinese dynasties and adopting the Chinese era name of Zhongtong.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=423–424}} Ariq Böke was hampered by inadequate supplies and surrendered in 1264.{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=104}} The three other Mongol khanates recognized Kublai as Great Khan,{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=62}} but were functionally autonomous.{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=413}} Civil strife had permanently ended the unity of the Mongol Empire.{{sfn|Allsen|2001|p=24}} | |||

| Many Han Chinese and Khitan defected to the Mongols to fight against the Jin. Two Han Chinese leaders, ], ] ({{lang|zh|]}}, aka Liu Ni),<ref>{{cite periodical | author= Wen Haiqing (溫海清) |url=http://big5.xjass.com/ls/content/2013-02/27/content_267592.htm |script-title=zh:"萬戶路"、"千戶州" ——蒙古千戶百戶制度與華北路府州郡體制 | trans-title= "Ten thousand per ''lu''", "one thousand per ''zhou''"— the Mongol decimal household administrative system and the ''lu–fu–zhou–jun'' structure in northern China |magazine=Fudan Academic Journal | issue= 4 |date=2012 |access-date=2016-05-27 |url-status=usurped |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304080427/http://big5.xjass.com/ls/content/2013-02/27/content_267592.htm |archive-date=2016-03-04}}</ref> and the Khitan ] ({{lang|zh|]}}) defected and commanded the 3 Tumens in the Mongol army. Liu Heima and Shi Tianze served Ögedei Khan.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F00qAQAAMAAJ |title=Foundations and Limits of State Power in China |date=1987 |isbn=978-0-7286-0139-0 |editor-last=Schram |editor-first=Stuart Reynolds | pages=113–146 | |||

| | author=Françoise Aubin | |||

| | chapter =The Rebirth of Chinese Rule in Times of Trouble | |||

| }}</ref>{{rp|129–130}} Liu Heima and Shi Tianxiang led armies against Western Xia for the Mongols.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MztuAAAAMAAJ | pages=158–185 |title=Rulers from the Steppe: State Formation on the Eurasian periphery |date=1989 |isbn=1-878986-01-5 | publisher= University of Southern California Press | series= Ethnographics Monograph Series No. 2 | |||

| | id= Proceedings of the Soviet-American Academic Symposia "Nomads: Masters of the Eurasian Steppe" | |||

| |editor1-last=Seaman |editor1-first=Gary |editor2-last=Marks |editor2-first=Daniel | |||

| | chapter = The Fall of the Xia Empire: Sino-Steppe Relations in the Late 12th – Early 13th Centuries | |||

| | author= Ruth Dunnell | |||

| }}</ref>{{rp|175}} There were 4 Han Tumens and 3 Khitan Tumens, with each Tumen consisting of 10,000 troops. The three Khitan Generals Shimobeidier ({{lang|zh-Hant|石抹孛迭兒}}), Tabuyir ({{lang|zh-Hant|塔不已兒}}), and Zhongxi, the son of Xiaozhaci ({{lang|zh-Hant|蕭札刺之子重喜}}) commanded the three Khitan Tumens and the four Han Generals Zhang Rou, Yan Shi, Shi Tianze, and Liu Heima commanded the four Han tumens under Ögedei Khan.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hu Xiaopeng (胡小鹏) |language=zh-Hans |url=http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/xbsdxb-shkxb200106008 |script-title=zh:窝阔台汗己丑年汉军万户萧札剌考辨——兼论金元之际的汉地七万户 |trans-title=A Study of Xiao Zhala the Han Army commander of 10,000 families in the ''jichou'' Year of 1229 during the Period of Ögedei Khan – with a discursus on the Han territory of 70,000 families at the Northern Jin–Yuan boundary |journal= Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Sciences) | date= 2001 | issue= 6 | pages = 36–42 | doi=10.3969/j.issn.1001-9162.2001.06.008}}</ref><ref>{{ cite book | title-link=New History of Yuan | title= New History of Yuan | date= 1920 | chapter=] | author = Ke Shaomin | author-link= Ke Shaomin }}</ref> | |||

| Möngke Khan commenced a military campaign against the Chinese ] in southern China.{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=410}} The Mongol force that invaded southern China was far greater than the force they sent to invade the Middle East in 1256.<ref>{{cite journal |jstor=606298 |title=Nomads on Ponies vs. Slaves on Horses. Reviewed Work: ''Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Īlkhānid War, 1260–1281'' by Reuven Amitai-Preiss |author=John Masson Smith Jr. |journal=] |volume=118 |issue=1 |year=1998 |pages=54–62}}</ref> He died in 1259 without a successor at the ].{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=411}} Kublai returned from fighting the Song in 1260 when he learned that his brother, ], was challenging his claim to the throne.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=422}} Kublai convened a kurultai in Kaiping that elected him Great Khan.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=51}} A rival kurultai in Mongolia proclaimed Ariq Böke Great Khan, beginning a civil war.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=53}} Kublai depended on the cooperation of his Chinese subjects to ensure that his army received ample resources. He bolstered his popularity among his subjects by modeling his government on the bureaucracy of traditional Chinese dynasties and adopting the Chinese era name of Zhongtong.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=423–424}} ] was hampered by inadequate supplies and surrendered in 1264.{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=104}} All of the three western khanates (], ] and ]) became functionally autonomous, and only the Ilkhans truly recognized Kublai as Great Khan.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=62}}{{sfn|Allsen|1994|p=413}} Civil strife had ].{{sfn|Allsen|2001|p=24}} | |||

| === Rule of Kublai Khan === | |||

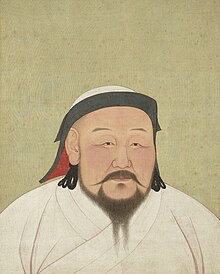

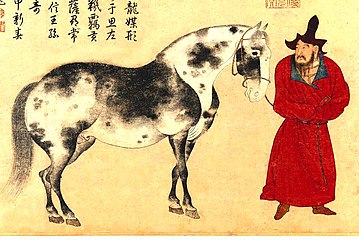

| ], ]'s grandson and founder of the Yuan dynasty]] | |||

| ===Rule of Kublai Khan=== | |||

| Instability troubled the early years of Kublai Khan's reign. Ogedei's grandson ] refused to submit to Kublai and threatened the western frontier of Kublai's domain.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=77}}{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=105}} The hostile but weakened Song dynasty remained an obstacle in the south.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=77}} Kublai secured the northeast border in 1259 by installing the hostage prince ] as the ruler of Korea, making it a Mongol tributary state.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|pp=436–437}}{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=77}} Kublai was also threatened by domestic unrest. Li Tan, the son-in-law of a powerful official, instigated a revolt against Mongol rule in 1262. After successfully suppressing the revolt, Kublai curbed the influence of the Han Chinese advisers in his court.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=426}} He feared that his dependence on Chinese officials left him vulnerable to future revolts and defections to the Song.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=66}} | |||

| ====Early years==== | |||

| Instability troubled the early years of Kublai Khan's reign. Ögedei's grandson ] refused to submit to Kublai and threatened the western frontier of Kublai's domain.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=77}}{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=105}} The hostile but weakened Song dynasty remained an obstacle in the south.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=77}} Kublai secured the northeast border in 1259 by installing the hostage prince ] as the ruler of the ] (Korea), making it a Mongol tributary state.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|pp=436–437}}{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=77}} Kublai betrothed one of his daughters to the prince to solidify the relationship between the two houses.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|pp=438}} Korean women were sent to the Yuan court as tribute and one concubine became the ] of the Yuan dynasty.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lorge |first1=Peter |title=Review of David M. Robinson, ''Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia under the Mongols''. Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series |journal=China Review International |date=2010 |volume=17 |issue=3 |pages=377–379 |issn=1069-5834 |jstor=23733178}}</ref> Kublai was also threatened by domestic unrest. Li Tan, the son-in-law of a powerful official, instigated a revolt against Mongol rule in 1262. After successfully suppressing the revolt, Kublai curbed the influence of the Han advisers in his court.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=426}} He feared that his dependence on Chinese officials left him vulnerable to future revolts and defections to the Song.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=66}} | |||

| Kublai's government after 1262 was a compromise between preserving Mongol interests in China and satisfying the demands of his Chinese subjects.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=427}} He instituted the reforms proposed by his Chinese advisers by centralizing the bureaucracy, expanding the circulation of paper money, and maintaining the ] and ].{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|pp=70–71}} |

Kublai's government after 1262 was a compromise between preserving Mongol interests in China and satisfying the demands of his Chinese subjects.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=427}} He instituted the reforms proposed by his Chinese advisers by centralizing the bureaucracy, expanding the circulation of paper money, and maintaining the ] and ].{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|pp=70–71}} He restored the Imperial Secretariat and left the local administrative structure of past Chinese dynasties unchanged.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=70}} However, Kublai rejected plans to revive the Confucian ]s and divided Yuan society into three classes with the Han occupying the lowest rank until the conquest of the ] and its people, who made up the fourth class, the Southern Chinese. Kublai's Chinese advisers still wielded significant power in the government, sometimes more than high officials, but their official rank was nebulous.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|pp=70–71}} | ||

| ====Founding the dynasty==== | |||

| Kublai readied the move from the Mongol capital from ] in Mongolia to ] in 1264,{{sfn|Ebrey|201|p=172}} by constructing a new city near the former ] capital ], now modern ] in 1266.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=132}} In 1271, Kublai Khan formally claimed the ] and declared that 1272 was the first year of the Great Yuan ({{zh|c=大元|links=no}}) in the style of a traditional Chinese dynasty.{{sfn|Mote|1994|p=616}} The name of the dynasty originated from the '']'' and describes the "origin of the universe" or a "primal force".{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=136}} Kublai proclaimed Khanbaliq the "Great Capital" or Daidu (Dadu, {{zh|c=大都|links=no}} in Chinese) of the dynasty.{{sfn|Mote|1999|p=460}} The era name was changed to Zhiyuan to herald a new era of Chinese history.{{sfn|Mote|1999|p=458}} The adoption of a dynastic name legitimized Mongol rule by integrating the government into the narrative of traditional Chinese political succession.{{sfn|Mote|1999|p=616}} Khublai evoked his public image as a sage emperor by following the rituals of Confucian propriety and ancestor veneration,{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=458}} while simultaneously retaining his roots as a leader from the steppes.{{sfn|Mote|1999|p=616}} | |||

| ], founder of the Yuan dynasty]] | |||

| Kublai readied the move of the Mongol capital from ] in Mongolia to ] in 1264,{{sfn|Ebrey|2010|p=172}} constructing a new city near the former ] capital ], now modern ], in 1266.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=132}} In 1271, Kublai formally claimed the ] and declared that 1272 was the first year of the Great Yuan ({{zh |c=大元 |labels=no }}) in the style of a traditional Chinese dynasty.{{sfn|Mote|1994|p=616}} The name of the dynasty is first attested in the '']'' and describes the "origin of the universe" or a "primal force".{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=136}} Kublai proclaimed Khanbaliq the Daidu ({{zhi|c=大都|p=Dàdū|l=Great Capital}}) of the dynasty.{{sfn|Mote|1999|p=461}} The era name was changed to Zhiyuan to herald a new era of Chinese history.{{sfn|Mote|1999|p=458}} The adoption of a dynastic name legitimized Mongol rule by integrating the government into the narrative of traditional Chinese political succession.{{sfn|Mote|1999|p=616}} Kublai evoked his public image as a sage emperor by following the rituals of Confucian propriety and ancestor veneration,{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=458}} while simultaneously retaining his roots as a leader from the steppes.{{sfn|Mote|1999|p=616}} | |||

| Kublai Khan promoted commercial, scientific, and cultural growth. He supported the merchants of the ] trade network by protecting the ], constructing infrastructure, providing loans that financed trade caravans, and encouraging the circulation of paper banknotes (鈔, ]). ], Mongol peace, enabled the spread of technologies, commodities, and culture between China and the West.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=72}} Kublai expanded the ] from southern China to Daidu in the north.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=74}} Mongol rule was cosmopolitan under Kublai Khan.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=62}} He welcomed foreign visitors to his court, such as the Venetian merchant ], who wrote the most influential European account of Yuan China.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=463}} Marco Polo's travels would later inspire many others like ] to chart a passage to the Far East in search of its legendary wealth.{{sfn|Allsen|2001|p=61}} | |||

| Kublai Khan promoted commercial, scientific, and cultural growth. He supported the merchants of the ] trade network by protecting the ], constructing infrastructure, providing loans that financed trade caravans, and encouraging the circulation of paper ] banknotes. During the beginning of the Yuan dynasty, the Mongols continued issuing ]; however, under ] coins were completely replaced by paper money. It was not until the reign of ] that the government of the Yuan dynasty would attempt to reintroduce copper coinage for circulation.<ref>{{cite book |author1=David Miles |author2=Andrew Scott |title=Macroeconomics: Understanding the Wealth of Nations |date=2005 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-0-470-01243-7 |page=273}}{{pb}}{{cite web |url=http://www.coinweek.com/expert-columns/mike-markowitz/coinweek-ancient-coin-series-coinage-mongols/ |series=Ancient Coin Series|title= Coinage of the Mongols |date=22 May 2016 |archive-date= 23 May 2016 | url-status =dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160523104237/http://www.coinweek.com/expert-columns/mike-markowitz/coinweek-ancient-coin-series-coinage-mongols/|author=Mike Markowitz | work=CoinWeek}}{{pb}}{{ cite book | last=Hartill | first= David |date= 2005 | title= Cast Chinese Coins: A Historical Catalogue | place= ] | isbn=1-4120-5466-4 | url= https://books.google.com/books?id=r4qWx1MFrMQC}}{{pn|date=July 2023}}</ref> The '']'', Mongol peace, enabled the spread of technologies, commodities, and culture between China and the West.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=72}} Kublai expanded the ] from southern China to Daidu in the north.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=74}} Mongol rule was cosmopolitan under Kublai Khan.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=62}} He welcomed foreign visitors to his court, such as the Venetian merchant ], who wrote the most influential European account of Yuan China.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=463}} Marco Polo's travels would later inspire many others like ] to chart a passage to the Far East in search of its legendary wealth.{{sfn|Allsen|2001|p=61}} | |||

| After strengthening his government in northern China, Kublai pursued an expansionist policy in line with the tradition of Mongol and Chinese imperialism. He renewed a massive drive against the Song dynasty to the south.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=429}} Kublai besieged ] between 1268 and 1273,{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=77}} the last obstacle in his way to capture the rich Yangzi River basin.{{sfn|Ebrey|201|p=172}} An unsuccessful naval expedition was undertaken against Japan in 1274.{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=107}} Kublai captured the Song capital of ] in 1276,{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=106}} the wealthiest city of China.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=430}} Song loyalists escaped from the capital and enthroned a young child as ]. The Mongols defeated the loyalists at the ] in 1279. The last Song emperor drowned, bringing an end to the Song dynasty.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|pp=77–78}} The conquest of the Song reunited northern and southern China for the first time in three hundred years.{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=113}} | |||

| Kublai's government faced financial difficulties after 1279. Wars and construction projects had drained the Mongol treasury.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=473}} Efforts to raise and collect tax revenues were plagued by corruption and political scandals.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=111}} Mishandled military expeditions followed the financial problems.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=473}} Kublai's second invasion of Japan in 1281 failed because of an ].{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=107}} Kublai botched his campaigns against ], and ],{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=113}} but won a ] against ].{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=218}} The expeditions were hampered by disease, an inhospitable climate, and a tropical terrain unsuitable for the mounted warfare of the Mongols.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=113}}{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=107}} Annam, Burma, and Champa recognized Mongol hegemony and established tributary relations with the Yuan dynasty.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|pp=218–219}} | |||

| ====Military conquests and campaigns==== | |||

| Internal strife threatened Kublai within his empire. Kublai Khan suppressed rebellions challenging his rule in Tibet and the northeast.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|pp=487–488}} His favorite wife died in 1281 and so did his chosen heir in 1285. Kublai grew despondent and retreated from his duties as emperor. He fell ill in 1293, and died on 18 February 1294.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=488}} | |||

| ]) according to the ] (1375, rotated 180°). ] with its caravan of traders appears in the bottom right corner, while the Pacific coast runs along the top-left corner. ] is seen enthroned. A flag with three red crescent moons {{nowrap|(])}} appears on all the territory.<ref>{{cite web |series=Catalan Atlas | work= The Cresques Project |title= Panel VI |url=https://www.cresquesproject.net/catalan-atlas-legends/panel-vi }}{{pb}}{{cite book |last1=Cavallo |first1=Jo Ann |title=The World Beyond Europe in the Romance Epics of Boiardo and Ariosto |date=2013 |publisher=University of Toronto Press |isbn=978-1-4426-6667-2 |page=32 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dYyBAAAAQBAJ&pg=PT32 }}</ref>]] | |||

| After strengthening his government in northern China, Kublai pursued an expansionist policy in line with the tradition of Mongol and Chinese imperialism. He renewed a massive drive against the Song dynasty to the south.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=429}} Kublai besieged ] (襄阳) between 1268 and 1273,{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=77}} the last obstacle in his way to capture the rich Yangtze River basin.{{sfn|Ebrey|2010|p=172}} An unsuccessful naval expedition was undertaken ] in 1274.{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=107}} The Duan family ruling the ] (大理) in Yunnan submitted to the Yuan dynasty as vassals and were allowed to keep their throne, militarily assisting the Yuan dynasty against the Song dynasty in southern China. | |||

| The Duan family still ruled Dali relatively independently during the Yuan dynasty.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| ===Decline after Kublai=== | |||

| | doi = 10.1163/9789004282483_006 | |||

| Following the conquest of ] in 1253, the former ruling Duan dynasty were appointed as ], recognized as imperial officials by the Yuan, ], and ]-era governments, principally in the province of ]. Succession for the Yuan dynasty, however, was an intractable problem, later causing much strife and internal struggle. This emerged as early as the end of Kublai's reign. Kublai originally named his eldest son, ], as the ], but he died before Kublai in 1285. Thus, Zhenjin's third son, with the support of his mother Kökejin and the minister ], succeeded the throne and ruled as ], or Emperor Chengzong, from 1294 to 1307. Temür Khan decided to maintain and continue much of the work begun by his grandfather. He also made peace with the western Mongol khanates as well as neighboring countries such as Vietnam, which recognized his nominal suzerainty and paid tributes for a few decades. However, the corruption in the Yuan dynasty began during the reign of Temür Khan. | |||

| | author1= Michael C. Brose | pages= 135–155 | |||

| | chapter= Yunnan's Muslim Heritage | |||

| |editor1-last=Anderson |editor1-first=James A. |editor2-last=Whitmore |editor2-first=John K. |title=China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia |date=2014 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-28248-3 |series = Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 3 Southeast Asia, Volume: 22 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YV1hBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA146}}</ref>{{rp|146}} The ] chieftains and local tribe leaders and kingdoms in Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan submitted to Yuan rule and were allowed to keep their titles. The Han Chinese Yang family ruling the ], which was recognized by both the Song and Tang dynasty, also received recognition by the Mongols in the Yuan dynasty, and later by the ]. The Luo clan in Shuixi led by Ahua were recognized by the Yuan emperors, as they were by the Song emperors when led by Pugui and Tang emperors when led by Apei. They descended from the ] era king Huoji who legendarily helped ] against ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Herman |first1=John. E. |editor1-last=Di Cosmo |editor1-first=Nicola |editor2-last=Wyatt |editor2-first=Don J |title=Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries and Human Geographies in Chinese History |date=2005 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-135-79095-0 |pages=245–285 | chapter = The Mu'ege kingdom: A brief history of a frontier empire in Southwest China | |||

| |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y1mQAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA260}}</ref>{{rp|260}} They were also recognized by the ].<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Crossley |editor1-first=Pamela Kyle |editor2-last=Siu |editor2-first=Helen F. |editor3-last=Sutton |editor3-first=Donald S. |title=Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China |date=2006 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-23015-6 |pages=135–170 |author1= John E. Herman | chapter = The Cant of Conquest: Tusi Offices and China's Political Incorporation of the Southwest Frontier|volume=28 of Studies on China |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EtNVMUx9qIIC&pg=PA143}}</ref>{{rp|143}} | |||

| In 1276 Kublai captured the Song capital of ] (杭州), the wealthiest city of China,{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=430}} after the surrender of the Southern Song Han Chinese ].{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=106}} Emperor Gong was married off to a Mongol princess of the royal ] family of the Yuan dynasty.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hua | first=Kaiqi |editor1-last=Heirman |editor1-first=Ann |editor2-last=Meinert |editor2-first=Carmen |editor3-last=Anderl |editor3-first=Christoph |title=Buddhist Encounters and Identities Across East Asia |date=2018 |publisher=Brill |location=Leiden |isbn=978-90-04-36615-2 |doi=10.1163/9789004366152_008 |pages=196–226 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bGdjDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA213 |chapter= The Journey of Zhao Xian and the Exile of Royal Descendants in the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1358)}}</ref>{{rp|213}} Song loyalists escaped from the capital and enthroned a young child as ], who was Emperor Gong's younger brother. The Yuan forces commanded by Han Chinese General ] led a predominantly Han navy to defeat the Song loyalists at the ] in 1279. The last Song emperor drowned, bringing an end to the Song dynasty.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|pp=77–78}} The conquest of the Song reunited northern and southern China for the first time in three hundred years.{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=113}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The Yuan dynasty created the "Han Army" ({{zh |t=漢軍 |labels=no }}) out of defected Jin troops and an army of defected Song troops called the "Newly Submitted Army" ({{zh |t=新附軍 |labels=no }}).<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8hOgAAAAIAAJ&q=han+tumen+khitan&pg=PA66 |title=A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China |author=Charles O. Hucker |page=66 |access-date=2016-05-27 |isbn=978-0-8047-1193-7 |year=1985 | publisher= Stanford University Press}}</ref> | |||

| ] (Emperor Wuzong) came to the throne after the death of Temür Khan. Unlike his predecessor, he did not continue Kublai's work, largely rejecting his objectives. Most significantly he introduced a policy called "New Deals", focused on monetary reforms. During his short reign (1307–11), the government fell into financial difficulties, partly due to bad decisions made by Külüg. By the time he died, China was in severe debt and the Yuan court faced popular discontent. | |||

| Kublai's government faced financial difficulties after 1279. Wars and construction projects had drained the Mongol treasury.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=473}} Efforts to raise and collect tax revenues were plagued by corruption and political scandals.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=111}} Mishandled military expeditions followed the financial problems.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=473}} Kublai's ] in 1281 failed because of an ].{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=107}} Kublai botched his campaigns against ], and ],{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=113}} but won a ] against ].{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|p=218}} The expeditions were hampered by disease, an inhospitable climate, and a tropical terrain unsuitable for the mounted warfare of the Mongols.{{sfn|Rossabi|2012|p=113}}{{sfn|Morgan|2007|p=107}} The ] which ruled Annam (Đại Việt) defeated the Mongols at the ]. Annam, Burma, and Champa recognized Mongol hegemony and established tributary relations with the Yuan dynasty.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|pp=218–219}} | |||

| The fourth Yuan emperor, ] (Ayurbarwada) was a competent emperor. He was the first among the Yuan emperors who actively supported and adopted the mainstream ] after the reign of Kublai, to the discontent of some Mongol elite. He had been mentored by ], a ] academic. He made many reforms, including the liquidation of the Department of State Affairs ({{lang-zh|尚書省}}), which resulted in the execution of five of the highest-ranking officials. Starting in 1313 the traditional ]s were reintroduced for prospective officials, testing their knowledge on significant historical works. Also, he codified much of the law, as well as publishing or translating a number of Chinese books and works. | |||

| Internal strife threatened Kublai within his empire. Kublai Khan suppressed rebellions challenging his rule in Tibet and the northeast.{{sfn|Rossabi|1988|pp=487–488}} His favorite wife died in 1281 and so did his chosen heir in 1285. Kublai grew despondent and retreated from his duties as emperor. He fell ill in 1293, and died on 18 February 1294.{{sfn|Rossabi|1994|p=488}} | |||

| The final years of the Yuan dynasty were marked by struggle, famine, and bitterness among the populace. In time, Kublai Khan's successors lost all influence on other Mongol lands across Asia, while the Mongols beyond the Middle Kingdom saw them as too Chinese. Gradually, they lost influence in China as well. The reigns of the later Yuan emperors were short and marked by intrigues and rivalries. Uninterested in administration, they were separated from both the army and the populace, and China was torn by dissension and unrest. ]s ravaged the country without interference from the weakening Yuan armies. | |||

| ===Successors after Kublai=== | |||

| ] of Zhaoxian County, ] Province, built in 1330 during the Yuan dynasty.]] | |||

| {{Main list|List of Yuan emperors}} | |||

| {{Further|List of Northern Yuan khans|Family tree of Chinese monarchs (late)}} | |||

| ====Temür Khan==== | |||

| Emperor ], Ayurbarwada's son and successor, ruled for only two years, from 1321 to 1323. He continued his father's policies to reform the government based on the Confucian principles, with the help of his newly appointed grand ] Baiju. During his reign, the Da Yuan Tong Zhi (]: 大元通制, "the comprehensive institutions of the Great Yuan"), a huge collection of codes and regulations of the Yuan dynasty begun by his father, was formally promulgated. Gegeen was assassinated in a ] involving five princes from a rival faction, perhaps steppe elite opposed to Confucian reforms. They placed ] (or Taidingdi) on the throne, and, after an unsuccessful attempt to calm the princes, he also succumbed to ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| Following the conquest of ] in 1253, the former ruling Duan family were appointed as its leaders.<ref>{{cite book |title=Genghis Khan: a Biography |last=Stone |first=Zofia |year=2017 |publisher=Vij Books India |isbn=978-93-86367-11-2 |location=New Delhi |oclc=975222159 | url = {{google books| plainurl= yes| id=6Q55zwEACAAJ }}}}{{pn|date=July 2023}}</ref> Local chieftains were appointed as ], recognized as imperial officials by the Yuan, ], and ]-era governments, principally in the province of ]. Succession for the Yuan dynasty, however, was an intractable problem, later causing much strife and internal struggle. This emerged as early as the end of Kublai's reign. Kublai originally named his eldest son, ], as the crown prince, but he died before Kublai in 1285.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Rise and Fall of the Second Largest Empire in History: How Genghis Khan's Mongols almost Conquered the World |last=Craughwell |first=Thomas J. |year=2010 |publisher=Fair Winds Press |isbn=978-1-61673-851-8 |location=Beverly, MA |page=251 |oclc=777020257 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ROijKBT6CMIC&pg=PA251}}</ref> Thus, Zhenjin's third son, with the support of his mother Kökejin and the minister ], succeeded the throne and ruled as ], or Emperor Chengzong, from 1294 to 1307. Temür Khan decided to maintain and continue much of the work begun by his grandfather. He also made peace with the western Mongol khanates as well as neighboring countries such as Vietnam,<ref>{{cite book |title=Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel |last=Howard |first=Michael C. |year=2012 |publisher=McFarland |isbn=978-0-7864-9033-2 |location=Jefferson, NC |page=84 |oclc=779849477 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6QPWXrCCzBIC&pg=PA84}}</ref> which recognized his nominal suzerainty and paid tributes for a few decades. However, the corruption in the Yuan dynasty began during the reign of Temür Khan. | |||

| ====Külüg Khan==== | |||

| Before Yesün Temür's reign, China had been relatively free from popular rebellions after the reign of Kublai. Yuan control, however, began to break down in those regions inhabited by ethnic minorities. The occurrence of these revolts and the subsequent suppression aggravated the financial difficulties of the Yuan government. The government had to adopt some measure to increase revenue, such as selling offices, as well as curtailing its spending on some items.{{sfn|Hsiao|1994|p=551}} | |||

| ] (Emperor Wuzong) came to the throne after the death of Temür Khan. Unlike his predecessor, he did not continue Kublai's work, largely rejecting his objectives. Most significantly he introduced a policy called "New Deals", focused on monetary reforms. During his short reign (1307–11), the government fell into financial difficulties, partly due to bad decisions made by Külüg. By the time he died, China was in severe debt and the Yuan court faced popular discontent.<ref name="San">{{cite book |title=Dynastic China: An Elementary History |last=San |first=Tan Koon |publisher=The Other Press |year=2014 |isbn=978-983-9541-88-5 |location=Kuala Lumpur |pages=312, 323 |oclc=898313910}}</ref>{{rp|323}} | |||

| When Yesün Temür died in Shangdu in 1328, ] was recalled to Khanbaliq by the ] commander ]. He was installed as the emperor (Emperor Wenzong) in Khanbaliq while Yesün Temür's son ] succeeded to the throne in Shangdu with the support of Yesün Temür's favorite retainer Dawlat Shah. Gaining support from princes and officers in Northern China and some other parts of the dynasty, Khanbaliq-based Tugh Temür eventually won the civil war against Ragibagh in 1329. Afterwards, Tugh Temür abdicated in favour of his brother ] who was backed by Chagatai Khan ] and announced Khanbaliq's intent to welcome him. However, Kusala suddenly died only four days after a banquet with Tugh Temür. He was supposedly killed with poison by El Temür, and Tugh Temür then remounted the throne. Tugh Temür also managed to send delegates to the western Mongol khanates such as ] and ] to be accepted as the suzerain of Mongol world.{{sfn|Hsiao|1994|p=550}} However, he was mainly a puppet of the powerful official El Temür during his latter three-year reign. El Temür purged pro-Kusala officials and brought power to warlords, whose despotic rule clearly marked the decline of the dynasty. | |||

| ====Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan==== | |||

| ] belt plaque featuring carved designs of a ].]] | |||

| The fourth Yuan emperor, ] (born Ayurbarwada), was a competent emperor. He was the first Yuan emperor to actively support and adopt mainstream ] after the reign of Kublai, to the discontent of some Mongol elite.<ref name=":0">{{cite encyclopedia | chapter=Yuan Dynasty |title=Historical Dictionary of Tibet |last1=Powers |first1=John |last2=Templeman |first2=David |year=2012 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=978-0-8108-7984-3 |location=Lanham, MD |page=742 |oclc=801440529 | chapter-url= https://books.google.com/books?id=LVlyX6iSDEQC&pg=PA742}}</ref> He had been mentored by ] ({{zhi|]}}), a ] academic. He made many reforms, including the liquidation of the ] ({{zh |t=尚書省 |labels=no }}), which resulted in the execution of five of the highest-ranking officials.<ref name=":0" /> Starting in 1313 the traditional ]s were reintroduced for prospective officials, testing their knowledge on significant historical works. Also, he codified much of the law, as well as publishing or translating a number of Chinese books and works. | |||

| ] dish with fish and flowing water design, mid fourteenth century, ].]] | |||

| ====Gegeen Khan and Yesün Temür==== | |||

| Due to the fact that the bureaucracy was dominated by El Temür, Tugh Temür is known for his cultural contribution instead. He adopted many measures honoring ] and promoting ]. His most concrete effort to patronize Chinese learning was founding the Academy of the Pavilion of the Star of Literature ({{lang-zh|奎章閣學士院}}), first established in the spring of 1329 and designed to undertake "a number of tasks relating to the transmission of Confucian high culture to the Mongolian imperial establishment". The academy was responsible for compiling and publishing a number of books, but its most important achievement was its compilation of a vast institutional ] named Jingshi Dadian ({{lang-zh|經世大典}}). Tugh Temür supported ]'s ] and also devoted himself in ]. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| |align=left | |||

| |direction=vertical | |||

| |image1=Yuntai north side.jpg | |||

| |width1=250 | |||

| |alt1= | |||

| |caption1= | |||

| |image2=Deva King of the East.jpg | |||

| |width2=250 | |||

| |alt2= | |||

| |caption2= | |||

| |footer=The ] was created during the reign of ] by imperial command. | |||

| }} | |||

| Emperor ], Ayurbarwada's son and successor, ruled for only two years, from 1321 to 1323. He continued his father's policies to reform the government based on the Confucian principles, with the help of his newly appointed grand ] Baiju. During his reign, the ''Da Yuan Tong Zhi'' ({{zh |c=《大元通制》 |l='Comprehensive Institutions of the Great Yuan' |labels=no }}), a huge collection of codes and regulations of the Yuan dynasty begun by his father, was formally promulgated. Gegeen was assassinated in a ] involving five princes from a rival faction, perhaps steppe elite opposed to Confucian reforms. They placed ] (or Taidingdi) on the throne, and, after an unsuccessful attempt to calm the princes, he also succumbed to ]. | |||

| After the death of Tugh Temür in 1332 and subsequent death of ] (Emperor Ningzong) the same year, the 13-year-old ] (Emperor Huizong), the last of the nine successors of Kublai Khan, was summoned back from ] and succeeded to the throne. After El Temür's death, ] became as powerful an official as El Temür had been in the beginning of his long reign. As Toghun Temür grew, he came to disapprove of Bayan's autocratic rule. In 1340 he allied himself with Bayan's nephew ], who was in discord with Bayan, and banished Bayan by coup. With the dismissal of Bayan, Toghtogha seized the power of the court. His first administration clearly exhibited fresh new spirit. He also gave a few early signs of a new and positive direction in central government. One of his successful projects was to finish the long-stalled official histories of the ], ], and ] dynasties, which were eventually completed in 1345. Yet, Toghtogha resigned his office with the approval of Toghun Temür, marking the end of his first administration, and he was not called back until 1349. | |||

| Before Yesün Temür's reign, China had been relatively free from popular rebellions after the reign of Kublai. Yuan control, however, began to break down in those regions inhabited by ethnic minorities. The occurrence of these revolts and the subsequent suppression aggravated the financial difficulties of the Yuan government. The government had to adopt some measure to increase revenue, such as selling offices, as well as curtailing its spending on some items.{{sfn|Hsiao|1994|p=551}} | |||

| From the late 1340s onwards, people in the countryside suffered from frequent natural disasters such as droughts, floods and the resulting famines, and the government's lack of effective policy led to a loss of popular support. In 1351, the ] started and grew into a nationwide uprising. In 1354, when Toghtogha led a large army to crush the Red Turban rebels, Toghun Temür suddenly dismissed him for fear of betrayal. This resulted in Toghun Temür's restoration of power on the one hand and a rapid weakening of the central government on the other. He had no choice but to rely on local warlords' military power, and gradually lost his interest in politics and ceased to intervene in political struggles. He fled north to ] from Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing) in 1368 after the approach of the forces of the ] (1368–1644), founded by ] in the south. He had tried to regain Khanbaliq, which eventually failed; he died in ] (located in present-day ]) two years later (1370). Yingchang was seized by the Ming shortly after his death. Some royal family members still lived in ] today.<ref></ref> | |||

| ====Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür==== | |||

| The ], ] established a separate pocket of resistance to the Ming in ] and ], but his forces were decisively defeated by the Ming in 1381. By 1387 the remaining Yuan forces in ] under Nahacu ]. | |||

| {{Main|Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür}} | |||

| ] of Zhaoxian County, ] Province, built in 1330 during the Yuan dynasty]] | |||

| When Yesün Temür died in Shangdu in 1328, ] was recalled to ] by the ] commander ]. He was installed as emperor in Khanbaliq, while Yesün Temür's son ] succeeded to the throne in Shangdu (商都) with the support of Yesün Temür's favorite retainer Dawlat Shah. Gaining support from princes and officers in Northern China and some other parts of the dynasty, Khanbaliq-based Tugh Temür eventually won the civil war against Ragibagh known as the ]. Afterwards, Tugh Temür abdi­cated in favour of his brother ], who was backed by Chagatai Khan ], and announced Khanbaliq's intent to welcome him. However, Kusala suddenly died only four days after a banquet with Tugh Temür. He was supposedly killed with poison by El Temür, and Tugh Temür then remounted the throne. Tugh Temür also managed to send delegates to the western Mongol khanates such as ] and ] to be accepted as the suzerain of Mongol world.{{sfn|Hsiao|1994|p=550}} However, he was mainly a puppet of the powerful official El Temür during his latter three-year reign. El Temür purged pro-Kusala officials and brought power to warlords, whose despotic rule clearly marked the decline of the dynasty. | |||

| Due to the fact that the bureaucracy was dominated by El Temür, Tugh Temür is known for his cultural contribution instead. He adopted many measures honoring ] and promoting ]. His most concrete effort to patronize Chinese learning was founding the Academy of the Pavilion of the Star of Literature ({{zh |t=奎章閣學士院 |labels=no }}), first established in the spring of 1329 and designed to undertake "a number of tasks relating to the transmission of Confucian high culture to the Mongolian imperial establishment" ({{zhi|儒教推崇}}). The academy was responsible for compiling and publishing a number of books, but its most important achievement was its compilation of a vast institutional ] named ''Jingshi Dadian'' ({{zh |t=經世大典 |labels=no }}). Tugh Temür supported ]'s ] and also devoted himself in ]. | |||

| === Northern Yuan === | |||

| {{Main|Northern Yuan dynasty}} | |||

| ] from the Yuan dynasty]] | |||

| ====Toghon Temür==== | |||

| The Yuan remnants retreated to Mongolia after the fall of Yingchang to the Ming in 1370, where the name Great Yuan (大元) was formally carried on, and is known as the '''Northern Yuan''' (北元). According to Chinese political orthodoxy, there could be only one legitimate dynasty whose rulers were blessed by ] to rule as ] (see ]), and so the Ming and the Northern Yuan denied each other's legitimacy as emperors of China, although the Ming did consider the previous Yuan which it had succeeded to be a legitimate dynasty. Historians generally regard ] rulers as the legitimate emperors of China after the Yuan dynasty, though Northern Yuan rulers also claimed to rule over China, and continued to resist the Ming under the name "Yuan" or "Northern Yuan". | |||

| After the death of Tugh Temür in 1332 and subsequent death of ] (Emperor Ningzong) the same year, the 13-year-old ] (Emperor Huizong), the last of the nine successors of Kublai Khan, was summoned back from ] and succeeded to the throne. After El Temür's death, ] became as powerful an official as El Temür had been in the beginning of his long reign. As Toghon Temür grew, he came to disapprove of Bayan's autocratic rule. In 1340 he allied himself with Bayan's nephew ], who was in discord with Bayan, and banished Bayan by coup. With the dismissal of Bayan, Toqto'a seized the power of the court. His first administration clearly exhibited fresh new spirit. He also gave a few early signs of a new and positive direction in central government. One of his successful projects was to finish the long-stalled ] of the ], ], and ] dynasties, which were eventually completed in 1345. Yet, Toqto'a resigned his office with the approval of Toghon Temür, marking the end of his first administration, and he was not called back until 1349. | |||

| ===Decline of the empire=== | |||

| The Ming army pursued the Northern Yuan forces into Mongolia in 1372, but were defeated by the latter under ] and his general ]. They tried again in 1380, ultimately winning a ]. Eight years later, the Northern Yuan throne was taken over by ], a descendant of ], instead of the descendants of ]. The following centuries saw a succession of Genghisid rulers, many of whom were mere figureheads put on the throne by those warlords who happened to be the most powerful. Periods of conflict with the Ming dynasty intermingled with periods of peaceful relations with border trade. In 1402, ] (Guilichi) abolished the name Great Yuan; he was however defeated by ] (Bunyashiri), protege of ] (Timur Barulas) in 1403. Mongols invaded the Ming many times in the following centuries and even captured its emperor (]) after defeating a large Ming army at ] in 1449. The high point of Mongol power came again in 1517, when Dayan Khan moved on ] itself. Although the Chinese held the Mongols off in a major battle, Dayan Khan and his successors continued to threaten China until 1526. The Mongolian armies raided the Ming Dynasty not only in the north, but also in the hitherto quiet west. The Ming Emperor ] lost his ] Hami to the ]s at the same time. In 1542 Dayan Khan defeated Chinese troops just before his death.<ref>Gérard Chaliand-Nomadic empires: from Mongolia to the Danube, p.102</ref> | |||

| ] swan]] | |||

| ] dish with fish and flowing water design, mid-14th century, ]]] | |||

| The final years of the Yuan dynasty were marked by struggle, famine, and bitterness among the populace. In time, Kublai Khan's successors lost all influence on other Mongol lands across Asia, while the Mongols beyond the Middle Kingdom saw them as too Chinese. Gradually, they lost influence in China as well. The reigns of the later Yuan emperors were short and marked by intrigues and rivalries. Uninterested in administration, they were separated from both the army and the populace, and China was torn by dissension and unrest. Outlaws ravaged the country without interference from the weakening Yuan armies. | |||

| By that time, Mongol Khaganate stretched from the ]n ] and ] in the north, across the ], to the edge of the ] and south of it into the Ordos. The lands extended from the forests of ] in the East past the ] and out onto the steppes of ].<ref></ref> | |||

| From the late 1340s onwards, people in the countryside suffered from frequent natural disasters such as droughts, floods and the resulting famines, and the government's lack of effective policy led to a loss of popular support. In 1351, the ] led by Song loyalists started and grew into a nationwide uprising and the Song loyalists established a renewed Song dynasty in 1351 with its capital at Kaifeng. In 1354, when Toghtogha led a large army to crush the Red Turban rebels, Toghon Temür suddenly dismissed him for fear of betrayal. This resulted in Toghon Temür's restoration of power on the one hand and a rapid weakening of the central government on the other. He had no choice but to rely on local warlords' military power, and gradually lost his interest in politics and ceased to intervene in political struggles. He fled north to ] from Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing) in 1368 after the approach of the forces of the ] (1368–1644), founded by ] in the south. Zhu Yuanzhang was a former Duke and commander in the army of the Red Turban Song dynasty and assumed power as Emperor after the death of the Red Turban Song Emperor ], who had tried to regain Khanbaliq, which eventually failed, and who died in ] (located in present-day ]) two years later (1370). Yingchang was seized by the Ming shortly after his death. Some royal family members still live in ] today.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.xinmin.cn/domestic/zonghe/2007/02/06/149732.html |script-title=zh:成吉思汗直系后裔现身河南 巨幅家谱为证 | trans-title= Genghis Khan's direct descendants still alive in Henan: huge pedigree chart verifies |work = 今日安报|url-status =dead | language= zh |date=6 February 2007 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20080928071037/http://news.xinmin.cn/domestic/zonghe/2007/02/06/149732.html | archive-date= 28 September 2008}}</ref>{{relevance inline|date=July 2023}} | |||

| After defeat at the hands of the Manchus and submission of the Northern Yuan leader ] to the ], the independent rule of the the Northern Yuan ended in 1635. The Qing then completely exterminated this main line of the Yuan royal family after an anti-Qing revolt in 1675 by Ejei's brother Abunai and Ejei's son Borni against the Qing, killing all males in the family and enslaving the females. The Qing Emperors then placed the Chahar Mongols under their direct rule. | |||

| The ], ] established a separate pocket of resistance to the Ming in ] and ], but his forces were decisively defeated by the Ming in 1381. By 1387 the remaining Yuan forces in ] under ] had also ]. The Yuan remnants retreated to Mongolia after the fall of Yingchang to the Ming in 1370, where the name Great Yuan ({{lang|zh|大元}}) was formally carried on, and is known as the ]. | |||

| == Impact == | |||

| ], an indication of the thriving exchanges with the Mongols during the period.]] | |||

| ==Impact== | |||

| A rich cultural diversity developed during the Yuan dynasty. The major cultural achievements were the development of ] and the ] and the increased use of the ]. The political unity of China and much of central Asia promoted trade between East and West. The Mongols' extensive West Asian and European contacts produced a fair amount of cultural exchange. The other cultures and peoples in the ] also very much influenced China. It had significantly eased trade and commerce across ] until its decline; the communications between Yuan dynasty and its ally and subordinate in ], the ], encouraged this development.{{sfn|Guzman|1988|pp=568-570}}{{sfn|Allsen|2001|p=211}} Buddhism had a great influence in the Yuan government, and the Tibetan-rite ] had significantly influenced China during this period. The Muslims of the Yuan dynasty introduced ] ], ], medicine, clothing, and diet in East Asia. Eastern crops such as ]s, ]s, new varieties of ]s, ]s, and ]s, high-quality granulated ], and ] were all either introduced or successfully popularized during the Yuan dynasty.<ref name="Mongol Empire p.611">C.P. Atwood - Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.611</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] plate]] | |||

| A rich cultural diversity developed during the Yuan dynasty. The major cultural achievements were the development of ] and the ] and the increased use of the ]. Arts and culture also greatly developed and flourished during the Yuan dynasty. There was a widespread introduction of blue and white painted porcelain, as well as a major change to Chinese painting.<ref>{{cite web |title=Yuan dynasty (1279{{ndash}}1368) |url=https://asia.si.edu/learn/for-educators/teaching-china-with-the-smithsonian/explore-by-dynasty/yuan-dynasty/ |work=] | series=Teaching China with the Smithsonian |access-date=3 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230507190351/https://asia-archive.si.edu/learn/for-educators/teaching-china-with-the-smithsonian/explore-by-dynasty/yuan-dynasty/ |archive-date=May 7, 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> The political unity of China and much of central Asia promoted trade between East and West. The Mongols' extensive West Asian and European contacts produced a fair amount of cultural exchange. The other cultures and peoples in the ] also very much influenced China. It had significantly eased trade and commerce across Asia until its decline; the communications between Yuan dynasty and its ally and subordinate in ], the ], encouraged this development.{{sfn|Guzman|1988|pp=568–570}}{{sfn|Allsen|2001|p=211}} Buddhism had a great influence in the Yuan government, and the Tibetan-rite ] had significantly influenced China during this period. The Muslims of the Yuan dynasty introduced ] ], ], medicine, clothing, and cuisine in East Asia. Eastern crops such as ]s, ]s, new varieties of ]s, ]s, and ]s, high-quality granulated ], and ] were all either introduced or successfully popularized during the Yuan dynasty.<ref name="Mongol Empire p.611" />{{rp|611}} | |||

| Western musical instruments were introduced to enrich Chinese performing arts. From this period dates the conversion to ], by Muslims of Central Asia, of growing numbers of Chinese in the northwest and southwest. ] and ] also enjoyed a period of toleration. ] (especially ]) flourished, although ] endured certain persecutions in favor of Buddhism from the Yuan government. ] governmental practices and examinations based on the ], which had fallen into disuse in north China during the period of disunity, were reinstated by the Yuan court, probably in the hope of maintaining order over Han society. Advances were realized in the fields of travel literature, ], ], and scientific education. | Western musical instruments were introduced to enrich Chinese performing arts. From this period dates the conversion to ], by Muslims of Central Asia, of growing numbers of Chinese in the northwest and southwest. ] and ] also enjoyed a period of toleration. ] (especially ]) flourished, although ] endured certain persecutions in favor of Buddhism from the Yuan government. ] governmental practices and examinations based on the ], which had fallen into disuse in north China during the period of disunity, were reinstated by the Yuan court, probably in the hope of maintaining order over Han society. Advances were realized in the fields of travel literature, ], ], and scientific education. | ||