| Revision as of 21:00, 8 October 2004 editLoremaster (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers55,231 edits →External links and references: Moved link back from Da Vinci Code article← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:44, 20 January 2025 edit undoOnel5969 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers939,238 editsm Disambiguating links to Esotericism (link changed to Western esotericism) using DisamAssist. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|French fraternal organization associated with a literary hoax}} | |||

| There was much speculation as to just what the '''''Prieuré de Sion''''' is. In its English translation it is usually rendered as '''Priory of Sion''', or even '''Priory of Zion'''. It was an elusive protagonist in many works of both non-fiction and fiction, and it had been characterized as anything from the most ] ] in Western history to a modern ]-esque ] but in fact it has been exposed as an elaborate ]. | |||

| {{Citation style|date=October 2020}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=August 2010}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} | |||

| ] of the Priory of Sion is partly based on the ], which was a symbol particularly associated with the ].<ref name="Baigent 1982">{{Cite book|last1=Baigent |first1=Michael |author-link1=Michael Baigent |last2=Leigh |first2=Richard |author-link2=Richard Leigh (author) |last3=Lincoln |first3=Henry |author-link3=Henry Lincoln | title=] | publisher=Jonathan Cape|year=1982|isbn=978-0-224-01735-0}}</ref>]] | |||

| The '''''Prieuré de Sion''''' ({{IPA|fr|pʁijœʁe də sjɔ̃}}), translated as '''Priory of Sion''', was a ] founded in ] and dissolved in 1956 by ] in his failed attempt to create a prestigious neo-].<ref name="Introvigne 2005">{{cite journal| author=Massimo Introvigne | url=http://www.cesnur.org/2005/pa_introvigne.htm | title=Beyond The Da Vinci Code: History and Myth of the Priory of Sion | publisher=] | date=2-5 June 2005 | access-date=20 November 2012}}</ref> In the 1960s, Plantard began claiming that his ] was the latest ] for a ] founded by crusading knight ], on ] in the ] in 1099, under the guise of the historical monastic ] of the ]. As a framework for his grandiose assertion of being both the ] prophesied by ] and a ] ], Plantard further claimed the Priory of Sion was engaged in a centuries-long benevolent ] to install a secret ] of the ] on the thrones of France and the rest of ].<ref name="Introvigne 2005"/><ref>Pierre Plantard, ''Gisors et son secret...'', ORBIS, 1961, abridged version contained in Gérard de Sède, ''Les Templiers sont parmi nous''. 1962.</ref> To Plantard's surprise, all of his claims were fused with the notion of a ] and popularised by the authors of the 1982 speculative nonfiction book '']'',<ref name="Baigent 1982" /> whose conclusions would later be borrowed by ] for his 2003 mystery thriller novel '']''.<ref name="Brown 2003">{{Cite book|author=] | title=] | publisher=Doubleday |year=2003|isbn=0-385-50420-9}}</ref><ref>Chapter 21 by Cory James Rushton, "Twenty-First-Century Templar", p. 236, in Gail Ashton (editor), ''Medieval Afterlives in Contemporary Culture'' (Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. {{ISBN|978-1-4411-2960-4}}).</ref> | |||

| After attracting varying degrees of public attention from the late 1960s to the 1980s, the ] of the Priory of Sion was exposed as a ] — an elaborate ] in the form of an ] ] — created by Plantard as part of his unsuccessful stratagem to become a respected, influential and wealthy player in French ] and ] circles. Pieces of evidence presented in support of the historical existence and activities of the Priory of Sion before 1956, such as the so-called '']'', were discovered to have been ] and then planted in various locations around France by Plantard and his accomplices.<ref name="Putnam 2003">{{Cite book|author=Bill Putnam, John Edwin Wood | title=The Treasure of Rennes-le-Château. A Mystery Solved | publisher=Sutton Publishing|year=2003|isbn=0750930810}}</ref> However, Pierre Plantard himself disowned Dossiers Secrets d'Henri Lobineau when he described it as being the work of Philippe Toscan du Plantier who had allegedly been arrested for taking LSD, in another attempt to form another version of the Priory of Sion from 1989, also reviving the organ “Vaincre”, that lasted for four issues. | |||

| Despite the "Priory of Sion mysteries" having been exhaustively ] by journalists and scholars as France's greatest 20th-century ],<ref name="Putnam 2003"/><ref name="Bradley 2006">{{Cite journal| last = Bradley | first = Ed | author-link = Ed Bradley | title = The Priory Of Sion: Is The "Secret Organization" Fact Or Fiction? | year = 2006 | url = https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-priory-of-sion/ | access-date=16 July 2008}}</ref><ref name="Katsoulis 2009">{{Cite book|author=Melissa Kasoutlis | title=Literary Hoaxes: An Eye-Opening History of Famous Frauds | publisher=Skyhorse |year=2009|isbn=978-1602397941}}</ref> many ] still ] that the Priory of Sion was a millennium-old ] concealing a religiously ] secret. A few independent researchers outside of ] claim, based on alleged insider information, that the Priory of Sion continues to operate as a conspiratorial secret society to this day.<ref name="Baigent 1987">{{Cite book| author=Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, Henry Lincoln | title=The Messianic Legacy | publisher=Henry Holt & Co | year=1987 |isbn=9780805005684}}</ref><ref name="Picknett 1997">{{Cite book| author=], Clive Prince | title=]: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ | publisher=Bantam Press |year=1997 |isbn=0593038703}}</ref><ref name="Gardner 2005">{{Cite book| author=Laurence Gardner | title=The Magdalene Legacy: The Jesus and Mary Bloodline Conspiracy | publisher=Harpercollins Pub Ltd |year=2005 |isbn=0007200846}}</ref><ref name="Picknett 2006">{{Cite book| author=], Clive Prince | title=The Sion Revelation. The Truth About the Guardians of Christ's Sacred Bloodline | publisher=Touchstone |year=2006 |isbn=0-7432-6303-0}}</ref><ref name="Howells 2011">{{Cite book| author=Robert Howells | title=Inside the Priory of Sion: Revelations from the World's Most Secret Society | publisher=Watkins Publishing |year=2011 |isbn=978-1-78028-136-0}}</ref> Some ]s express concern that the proliferation and popularity of ] books, websites and films inspired by the Priory of Sion hoax contribute to the problem of unfounded ] becoming mainstream;<ref name="Mondschein 2014">{{cite web |url=http://www.nypress.com/news/holy-blood-holy-grail-MXNP1020040720307209982 |title=Holy Blood, Holy Grail |last=Mondschein |first=Ken |date=11 November 2014 |website=Straus Media |publisher=Straus News |access-date=7 October 2020 |quote=Likewise, there's an entire cottage industry devoted to disseminating crazy conspiracy theories about the Knights Templar, from Richard Metzger's Disinfo.com (which seems to be more interested in the believers than the belief) to Dagobert's Revenge, the New Jersey-based conspiracy zine to which industrial musician Boyd Rice is a prominent contributor (it's named for a murdered Merovingian king). I've heard everything from the Templars having hidden the Ark of the Covenant in Ethiopia to their having built a supposed medieval tower in Connecticut a hundred years before Columbus sailed the ocean blue. The sad truth is that, while remnants survived in such groups as the Knights of Christ in Portugal, the Templars have about as much effect on the modern world as does the Empire of Trebezonia.}}</ref> while others are troubled by how these works romanticize the ] ideologies of the ].<ref name="Klinghoffer 2006">David Klinghoffer, "The Da Vinci Protocols: Jews should worry about Dan Brown’s success" {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090907001650/http://article.nationalreview.com/?q=NDY0YmNhMjc5YThmZWIxY2VjNmM3MWE0YjU1MDFhYTg= |date=7 September 2009 }}, ''National Review Online'', 2006. Retrieved on 28 March 2008.</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| The ] was founded in the town of ], ], in eastern France in 1956.<ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.elcaminosantiago.com/PDF/Book/The_Real_History_Behind_The_Da_Vinci_Code.pdf |first=Sharan |last=Newman |title=The Real History Behind the Da Vinci Code |pages=243–245 |location=New York |publisher=Berkley Books |isbn=0-7865-5469-X |access-date=8 March 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140909171253/http://www.elcaminosantiago.com/PDF/Book/The_Real_History_Behind_The_Da_Vinci_Code.pdf |archive-date=9 September 2014 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120324102225/http://jhaldezos.free.fr/lespersonnages/plantard/images/extraitdejo.html |date=24 March 2012 }}</ref> The 1901 ] of Associations required that the Priory of Sion be registered with the government; although the statutes and the registration documents are dated 7 May 1956, the registration took place at the ] of ] on 25 June 1956 and recorded in the '']'' on 20 July 1956.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://jhaldezos.free.fr/lespersonnages/plantard/images/extraitdejo.html |title=Pierre Plantard Extrait du Journal Officiel du 20 juillet 1956 |publisher=Jhaldezos.free.fr |date=16 February 2008 |access-date=20 November 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120324102225/http://jhaldezos.free.fr/lespersonnages/plantard/images/extraitdejo.html |archive-date=24 March 2012 }}</ref> The headquarters of the Priory of Sion and its journal ''Circuit'' were based in the apartment of Plantard, in a social housing block known as Sous-Cassan newly constructed in 1956.<ref>Guy Gavard, ''Histoire d'Annemasse et des communes voisines: les relations avec Genève de l'époque romaine à l'an 2000'' (Montmélian: la Fontaine de Siloé, impr. 2006).</ref><ref>Bernardo Sanchez Da Motta, ''Do Enigma de Rennes-le-Château ao Priorado de Siao – Historia de um Mito Moderno'', Esquilo, 2005, p. 322, reproducing the Priory of Sion Registration Document showing the group was based in Plantard's apartment.</ref> | |||

| Under Article III.c of the original 1956 Statutes of the Priory of Sion, the association was named after the nearby mountain called Sion by the French town of Annemasse. It was devoted to opposing ] in the area through its journal, ''Circuit''. The 1956 Priory had its headquarters in ]'s house in Annemasse and was officially registered at the sub-prefecture in Saint-Julien-en-Genevoise on May 7th, 1956, by André Bonhomme and Pierre Plantard. It was dissolved sometime after October 1956 but intermittently revived by Plantard between 1962 and 1993 as an ] order and crypto-political ] dedicated to the restoration of ] and ] in ] to further his ] royalty bid. | |||

| The founders and signatories inscribed with their real names and aliases were Pierre Plantard, also known as "Chyren", and André Bonhomme, also known as "Stanis Bellas". Bonhomme was the President while Plantard was the Secretary General. The registration documents also included the names of Jean Deleaval as the Vice-President and Armand Defago as the Treasurer. The choice of the name "Sion" was based on a popular local feature, a hill south of Annemasse in France, known as Mont Sion, where the founders intended to establish a ] center.<ref name="Bradley 2006" /> The accompanying title to the name was "''Chevalerie d'Institutions et Règles Catholiques d'Union Indépendante et Traditionaliste''": this subtitle forms the acronym CIRCUIT and translates in English as "Chivalry of Catholic Rules and Institutions of Independent and Traditionalist Union". The statutes of the Priory of Sion indicate its purpose was to allow and encourage members to engage in studies and ]. The articles of the association expressed the goal of creating a ] ].<ref name="Jean-Luc Chaumeil">"Les Archives du Prieuré de Sion", ''Le Charivari'', N°18, 1973. Containing a transcript of the 1956 Statutes of the Priory of Sion.</ref> | |||

| Article 7 of the statutes of the Priory of Sion stated that its members were expected "to carry out good deeds, to help the Roman Catholic Church, teach the truth, defend the weak and the oppressed". Towards the end of 1956 the association had planned to forge partnerships with the local Catholic Church of the area which would have involved a school bus service run by both the Priory of Sion and the church of Saint-Joseph in Annemasse.<ref>J. Cailleboite, "A Sous-Cassan et aux pervenches un missionnaire regarde la vie ouvriere", ''Circuit'', Numéro spécial, October 1956.</ref> Plantard is described as the President of the Tenants' Association of Annemasse in the issues of ''Circuit''. The bulk of the activities of the Priory of Sion bore no resemblance to the objectives as outlined in its statutes: ''Circuit'', the official journal of the Priory of Sion, was indicated as a news bulletin of an "organisation for the defence of the rights and the freedom of affordable housing" rather than for the promotion of ]-inspired charitable work. The first issue of the journal is dated 27 May 1956, and, in total, twelve issues appeared. Some of the articles took a political position in the local council elections. Others criticised and even attacked real-estate developers of Annemasse.<ref name="Jean-Luc Chaumeil" /> | |||

| According to a letter written by Léon Guersillon the Mayor of Annemasse in 1956, contained in the folder holding the 1956 Statutes of the Priory of Sion in the subprefecture of Saint-Julien-en-Genevois, Plantard was given a six-month sentence in 1953 for fraud.<ref>''The History of a Mystery'', BBC 2, transmitted on 17 September 1996</ref> The formally registered association was dissolved some time after October 1956 but intermittently revived for different reasons by Plantard between 1961 and 1993, though in name and on paper only. The Priory of Sion is considered dormant by the subprefecture because it has indicated no activities since 1956. According to French law, subsequent references to the Priory bear no legal relation to that of 1956 and no one, other than the original signatories, is entitled to use its name in an official capacity.{{citation needed|date=April 2018}} André Bonhomme played no part in the association after 1956. He officially resigned in 1973 when he heard that Plantard was linking his name with the association. In light of Plantard's death in 2000, there is no one who is currently alive who has official permission to use the name.<ref>Pierre Jarnac, ''Les Archives de Rennes-le-Château'', Tome II, Editions Belisane, 1988, p. 566.</ref> | |||

| ==Myth== | |||

| ===Plantard's plot=== | |||

| Plantard set out to have the Priory of Sion perceived as a prestigious ] chivalric order, whose members would be ] in the fields of finance, politics and philosophy, devoted to installing the "]", prophesied by ], on the throne of France. Plantard's choice of the pseudonym "Chyren" was a reference to "Chyren Selin", Nostradamus's ] for the name for this ] figure.<ref>Marie-France Etchegoin & Frédéric Lenoir, ''Code Da Vinci: L'Enquête'', p. 61 (Robert Laffont, 2004).</ref> | |||

| Between 1961 and 1984, Plantard contrived a ] pedigree for the Priory of Sion claiming that it was the offshoot of a real ] housed in the Abbey of Our Lady of Mount Zion, which had been founded in the ] during the ] in 1099 and later absorbed by the ] in 1617. The mistake is often made that this Abbey of Sion was a Priory of Sion, but there is a difference between an ] and a ].<ref name="Introvigne 2005"/> Calling his original 1956 group "Priory of Sion" presumably gave Plantard the later idea to claim that his organisation had been historically founded by crusading knight ] on ] near ] during the ].<ref name="Putnam 2003"/> | |||

| ]'s late 1630s painting '']'' was appropriated for Priory of Sion myth-making, first utilised in 1964.]]Furthermore, Plantard was inspired by a 1960 magazine ''Les Cahiers de l'Histoire'' to center his personal genealogical claims, as found in the "Priory of Sion documents", on the ] king ], who had been assassinated in the 7th century.<ref>Jean-Luc Chaumeil, ''La Table d'Isis ou Le Secret de la Lumière'', Editions Guy Trédaniel, 1994, pp. 121–124.</ref> He also adopted ''"]..."'', a slightly altered version of a ] that most famously appears as the title of two paintings by ], as the ] of both his family and the Priory of Sion,<ref>Madeleine Blancassall, "Les Descendants Mérovingiens ou l’énigme du Razès wisigoth" (1965), in: Pierre Jarnac, ''Les Mystères de Rennes-le-Château, Mélanges Sulfureux'', CERT, 1994.</ref> because the tomb which appears in these paintings resembled one in the Les Pontils area near ]. This tomb would become a symbol for his ] claims as the last legacy of the Merovingians on the territory of ], left to remind the select few who have been initiated into these ] that the "lost king", Dagobert II, would figuratively come back in the form of a hereditary ].<ref name="Jean Delaude 1994">Jean Delaude, ''Le Cercle d’Ulysse'' (1977), in: Pierre Jarnac, ''Les Mystères de Rennes-le-Château, Mélanges Sulfureux'', CERT, 1994.</ref><ref>A photograph of a young Thomas Plantard de Saint-Clair standing next to the Les Pontils tomb was published in Jean-Pierre Deloux, Jacques Brétigny, ''Rennes-le-Château – Capitale Secrète de l'Histoire de France'', 1982.</ref> | |||

| To lend credibility to the apparently fabricated lineage and pedigree, Plantard and his friend, ], needed to create "independent evidence". So during the 1960s, they created and deposited a series of ]s, the most famous of which was entitled '']'' ("Secret Files of Henri Lobineau"), at the ] in Paris. During the same decade, Plantard commissioned de Chérisey to forge two medieval ]s. These parchments contained encrypted messages that referred to the Priory of Sion. | |||

| They adapted, and used to their advantage, the earlier false claims put forward by ] that a Catholic priest named ] had supposedly discovered ancient parchments inside a pillar while renovating his church in ] in 1891. Inspired by the popularity of media reports and books in France about the discovery of the ] in the ], they hoped this same theme would attract attention to their parchments.<ref name="ChaumTest">Jean-Luc Chaumeil (Goeroe of speculative freemason), ''Rennes-le-Château – Gisors – Le Testament du Prieuré de Sion. Le Crépuscule d’une Ténébreuse Affaire'', Éditions Pégase, 2006.</ref> Their version of the parchments was intended to prove Plantard's claims about the Priory of Sion being a medieval secret society that was the source of the "underground stream" of ] in Europe.<ref name="Putnam 2003"/> | |||

| Plantard then enlisted the aid of author ] to write a book based on his unpublished manuscript and forged parchments,<ref name="ChaumTest"/> alleging that Saunière had discovered a link to a hidden treasure. The 1967 book ''L'or de Rennes, ou La vie insolite de Bérenger Saunière, curé de Rennes-le-Château'' ("The Gold of Rennes, or The Strange Life of Bérenger Saunière, Priest of Rennes-le-Château"), which was later published in paperback under the title ''Le Trésor Maudit de Rennes-le-Château'' ("The Accursed Treasure of Rennes-le-Château") in 1968, became a popular read in France. It included copies of the found parchments (the originals were, of course, never produced), though it did not provide the decoded hidden texts contained within them. One of the Latin texts in the parchments was copied from the '']'', an attempted restoration of the ] by ] and Henry White.<ref name="Putnam 2003"/> | |||

| The other text was copied from the ].<ref name="Putnam 2003"/> Based on the wording used, the versions of the Latin texts found in the parchments can be shown to have been copied from books first published in 1889 and 1895, which is problematic considering that de Sède's book was trying to make a case that these documents were centuries old. In 1969, English scriptwriter, producer and researcher ] became intrigued after reading ''Le Trésor Maudit''. He discovered one of the encrypted messages, which read "''À Dagobert II Roi et à Sion est ce trésor, et il est là mort''" ("To Dagobert II, King, and to Sion belongs this treasure and he is there dead"). This was possibly an allusion to the tomb and ] of ], a real or mythical son of Dagobert II which would not only prove that the Merovingian dynasty did not end with the death of the king, but that the Priory of Sion has been entrusted with the duty to protect his ]s like a treasure.<ref name="Baigent 1982" /> | |||

| Lincoln expanded on the conspiracy theories, writing his own books on the subject, and inspiring and presenting three ] ] documentaries between 1972 and 1979 about the alleged mysteries of the Rennes-le-Château area. In response to a tip from Gérard de Sède, Lincoln claims he was also the one who discovered the ''Dossiers Secrets'', a series of planted genealogies which appeared to further confirm the link with the extinct Merovingian bloodline. The documents claimed that the Priory of Sion and the ] were two fronts of one unified organisation with the same leadership until 1188.<ref name="Baigent 1982"/> | |||

| Letters in existence dating from the 1960s written by Plantard, de Chérisey and de Sède to each other confirm that the three were engaging in an out-and-out ]. The letters describe schemes to combat criticisms of their various allegations and ways they would make up new allegations to try to keep the hoax alive. These letters (totalling over 100) are in the possession of French researcher Jean-Luc Chaumeil, who has also retained the original envelopes. A letter later discovered at the subprefecture of Saint-Julien-en-Genevois also indicated that Plantard had a criminal conviction as a ].<ref>''The History of a Mystery'', BBC 2, transmitted on 17 September 1996.</ref><ref name="Bradley 2006" /> | |||

| ===''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail''=== | |||

| {{details|The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail}} | |||

| As the ''Chronicle'' documentaries on the topic became quite popular and generated thousands of responses, Lincoln then joined forces with ] and ] for further research. This led them to the ] '']'' at the ], which though alleging to portray hundreds of years of medieval history, were actually all written by Plantard and de Chérisey under the pseudonym of "Philippe Toscan du Plantier". | |||

| Unaware that the documents had been forged, Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh used them as a major source for their 1982 speculative nonfiction book ''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail,''<ref name="Baigent 1982"/> in which they presented the following ] to support their hypotheses:<ref name="Thompson 2008">], "", ''Daily Telegraph''. 13 January 2008. Retrieved on 28 March 2008.</ref> | |||

| * there is a ] known as the Priory of Sion, which has a long history starting in 1099, and had illustrious ] including ] and ]; | |||

| * it created the ] as its military arm and financial branch; and | |||

| * it is devoted to installing the ], that ruled the ] from 457 to 751, on the thrones of France and the rest of Europe. | |||

| The authors re-interpreted the ''Dossiers Secrets'' in the light of their own interest in questioning the Catholic Church's institutional reading of ] history.<ref>''Conspiracies On Trial: The Da Vinci Code'' (The Discovery Channel); transmitted on 10 April 2005.</ref> Contrary to Plantard's initial ] claim that the Merovingians were only descended from the ],<ref>Pierre Jarnac, ''Les Mystères de Rennes-le-Château: Mèlange Sulfureux'' (CERT, 1994).</ref> they asserted that: | |||

| * the Priory of Sion protects Merovingian ]s because they may be the lineal ] and his alleged wife, ], traced further back to ]; | |||

| * the legendary ] is simultaneously the womb of ] Mary Magdalene and the sacred ] she gave birth to; and | |||

| * the Church tried to kill off all remnants of this bloodline and their supposed guardians, the ] and the ], so ] could hold the ] through the ] of ] without fear of it ever being ] by an ] from the ] of Mary Magdalene. | |||

| The authors therefore concluded that the modern goals of the Priory of Sion are: | |||

| * the public revelation of the tomb and shrine of ] as well as the ] of the ], which supposedly contains genealogical records that prove the Merovingian dynasty was of the ], to facilitate Merovingian restoration in France; | |||

| * the re-institutionalization of ] ] and the promotion of ]; | |||

| * the establishment of a ] "]": a Holy European Empire politically and religiously unified through the ] of a Merovingian ] who occupies both the throne of Europe and the ]; and | |||

| * the actual governance of Europe residing with the Priory of Sion through a ] ]. | |||

| The authors incorporated the ] and ] tract known as '']'' into their story, concluding that it was actually based on the master plan of the Priory of Sion. They presented it as the most persuasive piece of evidence for the existence and activities of the Priory of Sion by arguing that: | |||

| * the original text on which the published version of ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' was based had nothing to do with ] or an "]". It issued from a ] practicing the ] which incorporated the word "]" in its name; | |||

| * the original text was not intended to be released publicly, but was a program for gaining control of ] as part of a strategy to infiltrate and reorganize church and state according to ] principles; | |||

| * after a failed attempt to gain influence in the court of Tsar ], ] changed the original text to forge an inflammatory tract in 1903 to discredit the esoteric clique around ] by implying they were ]; and | |||

| * some esoteric Christian elements in the original text were ignored by Nilus and hence remained unchanged in the ] he published. | |||

| In reaction to this ] of investigative journalism with religious ], many secular conspiracy theorists added the Priory of Sion to their list of ] collaborating or competing to manipulate political happenings from behind the scenes in their bid for ].<ref name="Moench 1995">Doug Moench, ''Factoid Books. The Big Book of Conspiracies'', Paradox Press, 1995. {{ISBN|1-56389-186-7}}.</ref> Some ] speculated that the emergence of the Priory of Sion and Plantard closely follows ''The Prophecies by M. Michel Nostradamus'' (unaware that Plantard was ] them).<ref>Marie-France Etchegoin & Frédéric Lenoir, ''Code Da Vinci: L’Enquête'', p. 61 (Robert Laffont; 2004).</ref> Fringe ] countered that it was a fulfilment of ] found in the ] and further proof of an ] conspiracy of epic proportions.<ref name="Aho 1997">Barbara Aho, ", watchpair.com, 1997. Retrieved on 5 October 2020.</ref> | |||

| Historians and scholars from related fields do not accept ''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail'' as a serious dissertation.<ref>Martin Kemp, Professor of Art History at Oxford University, on the documentary ''The History of a Mystery'', BBC Two, transmitted on 17 September 1996, commenting on books like ''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail'': "There are certain historical problems, of which the Turin Shroud is one, in which there is 'fantastic fascination' with the topic, but a historical vacuum – a lack of solid evidence – and where there's a vacuum – nature abhores a vacuum – and historical speculation abhors a vacuum – and it all floods in...But what you end up with is almost nothing tangible or solid. You start from a hypothesis, and then that is deemed to be demonstrated more-or-less by stating the speculation, you then put another speculation on top of that, and you end up with this great tower of hypotheses and speculations – and if you say 'where are the rocks underneath this?' they are not there. It's like the House on Sand, it washes away as soon as you ask really hard questions of it."</ref> French authors like Franck Marie (1978),<ref>Franck Marie, ''Rennes-le-Château: Etude Critique'' (SRES, 1978).</ref> Pierre Jarnac (1985),<ref>Pierre Jarnac, ''Histoire du Trésor de Rennes-le-Château'' (1985).</ref> (1988),<ref>Pierre Jarnac, ''Les Archives de Rennes-le-Château'' (Editions Belisane, 1988). Describing ''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail'' as a "monument of mediocrity".</ref> Jean-Luc Chaumeil (1994),<ref>Jean-Luc Chaumeil,''La Table d'Isis ou Le Secret de la Lumière'' (Editions Guy Trédaniel, 1994).</ref> and more recently Marie-France Etchegoin and Frédéric Lenoir (2004),<ref>Marie-France Etchegoin & Frédéric Lenoir, ''Code Da Vinci: L'Enquête'' (Robert Laffont, 2004).</ref> ] (2005),<ref>Massimo Introvigne, ''Gli Illuminati E Il Priorato Di Sion – La Verita Sulle Due Societa Segrete Del Codice Da Vinci Di Angeli E Demoni'' (Piemme; 2005).</ref> Jean-Jacques Bedu (2005),<ref>Jean-Jacques Bedu, ''Les sources secrètes du Da Vinci Code'' (Editions du Rocher, 2005).</ref> and Bernardo Sanchez Da Motta (2005),<ref>Bernardo Sanchez Da Motta, ''Do Enigma de Rennes-le-Château ao Priorado de Siao – Historia de um Mito Moderno'' (Esquilo, 2005).</ref> have never taken Plantard and the Priory of Sion as seriously as Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh. They eventually concluded that it was all a ], outlining in detail the reasons for their verdict, and giving detailed evidence that the ''Holy Blood'' authors had not reported comprehensively.<ref name="Miller 2004">{{Cite journal| last = Miller | first = Laura | title = The Last Word; The Da Vinci Con | url = https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B07E0DD103AF931A15751C0A9629C8B63 | access-date=16 July 2008 | date=22 February 2004 | journal=The New York Times}}</ref> They imply that this evidence had been ignored by Lincoln, Baigent, and Leigh to bolster the mythical version of the Priory's history that was developed by Plantard during the early 1960s after meeting author ].<ref name="Miller 2004"/> | |||

| === ''The Messianic Legacy'' === | |||

| Between 1961 and 1984 Plantard contrived a mythical pedigree of the Priory of Sion claiming that it had been founded in ] during the ] by ]. Research in the ] mysteries led Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln to the ] ''Secret Files of Henri Lobineau'', compiled by "Philippe Toscan du Plantier," that became the source for their book, ''],'' in which they reported claims that | |||

| In 1986, Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh published ''The Messianic Legacy'', a sequel to ''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail''. The authors assert that the Priory of Sion is not only ''the'' archetypal ] but an ideal repository of the cultural legacy of ] that could end the “crisis of ]” within the ] by providing a Merovingian ] as a ] in which the West and, by extension, humanity can place its trust. However, the authors are led to believe by Plantard that he has resigned as ] of the Priory of Sion in 1984 and that the organisation has since gone underground in reaction to both an internal power struggle between Plantard and an “Anglo-American contingent” as well as a campaign of ] against Plantard in the press and books written by skeptics.<ref name="Baigent 1987"/> | |||

| # with a list of illustrious grand masters (]), the Priory of Sion has a long history starting with the creation of the ] as its military front; | |||

| # it had a large role in partaking in and promoting the "underground river of ]," the ], in Medieval Europe; | |||

| # it is sworn to returning the ] dynasty, that ruled the Frankish kingdom from ] to ] C.E., to the thrones of ] and Jerusalem; and | |||

| # the order protects these royal claimants because they are the literal descendants of ] and his wife ]. | |||

| Although Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh remain convinced that the pre-1956 history of the Priory of Sion is true, they confess to the possibility that all of Plantard's claims about a post-1956 Priory of Sion were part of an elaborate ] to become a respected, influential and wealthy player in French ] and ] circles.<ref name="Baigent 1987"/> | |||

| These authors furthered that the ultimate goals of the Priory of Sion are | |||

| #the founding of a '] ]' that would become the next ] and usher in a ] of peace and prosperity; | |||

| # the supplantation of the ] with an ] ] ] by revealing the ] and lost ] relics which would prove ] views and ] claims; and | |||

| # the grooming and installing of the ] of a ]. | |||

| ===Revised myth=== | |||

| Baigent, Leigh, and Lincoln came to their own interpretation of the ], where they used the spelling "Sion" in the name: | |||

| In 1989, Plantard tried but failed to salvage his reputation and agenda as a ] in esotericist circles by claiming that the Priory of Sion had actually been founded in 1681 at ], and was focused more on harnessing the ] power of ]s and sunrise lines,<ref>The ley line is from "Fauteil du Diable" to "Fortin de Blanchefort", intersected by a sunrise line of 17 January from the church of Rennes-les-Bains to the church of Rennes-le-Château, in ''Vaincre'', page 19 (June 1989). This was first given, in much more complex form, in Philippe de Chérisey's 1975 document ''L'Or de Rennes pour un Napoléon'' (Bibliothèque Nationale; Tolbiac – Rez-de-jardin – magasin 4- LB44- 2360).</ref> and a promontory called "Roc Noir" (Black Rock) in the area,<ref>Quoting from Plantard's letter dated 4 April 1989: "Our Treasure, that of the Priory of Sion, is the Secret of the Roc Noir. Venerated since high antiquity by those who believed in its immense power..."</ref> than installing a Merovingian ] on the restored throne of France. In 1990, Plantard revised himself by claiming he was only descended from a ] of the line of Dagobert II, while arguing that the direct descendant was really ].<ref>Quoting Pierre Plantard: "If anyone can claim to be a descendant of Sigisbert IV in the direct line it can only be Otto von Habsburg, and he alone. To all those people who write to me I have given this same reply." From ''Vaincre – Reprend le titre d'un périodique paru en 1942–1943'', Number 1, April 1990 {{cite web |url=http://jhaldezos.free.fr/lespersonnages/plantard/images/Vaincre%20avril%201990.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=18 August 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110818232934/http://jhaldezos.free.fr/lespersonnages/plantard/images/Vaincre%20avril%201990.pdf |archive-date=18 August 2011 }} The April 1989, June 1989, September 1989, April 1990 issues of ''Vaincre'' were compiled together (with some of the articles modified) in 1992 and entitled ''Le Cercle: Rennes-le-Château et le Prieuré de Sion'', consisting of 86 pages. This material was published in December 2007 by Pierre Jarnac in ''Pégase, No 5 hors série, Le Prieuré de Sion – Les Archives de Pierre Plantard de Saint-Clair – Rennes-le-Chateau – Gisors – Stenay'' (90 pages) {{cite web |url=http://www.rennes-le-chateau.tv/back/images_article/03010918115990.jpg |title=Archived copy |access-date=25 April 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120425051656/http://www.rennes-le-chateau.tv/back/images_article/03010918115990.jpg |archive-date=25 April 2012 }}</ref><ref>Quoting Plantard: "We would like to repeat that in no case have we found any trace of the son of Dagobert II in the list of the Visigothic Razes. This Sigibert IV found refuge with his abbess sister at Oeren and was the cousin of Sigebert de Rhedae, who was alive more or less around the same time. Historians conflate these two Sigiberts into one person. When did Sigebert IV die? We don't know. Some think that he was the founder of the Habsburg family."</ref> | |||

| ===Pelat Affair=== | |||

| #The original version emanated from an irregular Masonic organization that used the name "Sion" but had nothing to do with an international ] ]. | |||

| In September 1993, while investigative judge Thierry Jean-Pierre was investigating the activities of multi-millionaire Roger-Patrice Pelat in the context of the Pechiney-Triangle Affair, he was informed that Pelat may have once been ] of a secret society known as the Priory of Sion. Pelat's name had been on Plantard's list of Grand Masters since 1989. In fact, Pelat had died in 1989, while he was being indicted for ]. Following a long established pattern of using dead people's names, Plantard "recruited" the "initiate" Pelat soon after his death and included him as the most recent Priory of Sion Grand Master.<ref name="lepoint">"Affaire Pelat: Le Rapport du Juge", ''Le Point'', no. 1112 (8–14 January 1994), p. 11.</ref> Plantard had first claimed that Pelat had been a Grand Master in a Priory of Sion pamphlet dated 8 March 1989, then claimed it again later in a 1990 issue of ''Vaincre'', the revived publication of Alpha Galates, a ] created by Plantard in ] to support the "]".<ref>''Les Cahiers de Rennes-le-Chateau'', Nr. IX, page 59, Éditions Bélisane, 1989.</ref><ref>Jean-Jacques Bedu, ''Les sources secrètes du Da Vinci Code'', Editions du Rocher, 2005.</ref> | |||

| #The original version was not intended to be inflammatory or released publicly, but was a program for gaining control of ]. | |||

| #The person responsible for changing the text in about 1903 was ] in the course of his attempt to gain influence in the Court of Tsar ]. The presence of esoteric cliques in the royal court led to considerable intrigue. Nilus' publication of the text resulted from his failure to succeed in wresting influence away from ] and an otherwise unidentified "Monsieur Philippe". | |||

| #Since Nilus did not recognize a number of references in the text that reflected a background in a Christian cultural context, he did not change them. This fact established that the original version could not possibly have come from the Judaic Congress in Basle in 1897. | |||

| Pelat had been a friend of ], then ], and at the centre of a scandal involving French Prime Minister ]. As an investigative judge, Jean-Pierre could not dismiss any information brought to his attention pertaining to the case, especially if it might have led to a scandal similar to the one implicating an illegal pseudo-] named ] in the 1982 ] bank failure in Italy, Jean-Pierre ordered a search of Plantard's home. The search turned up a hoard of false documents, including some proclaiming Plantard the true ]. Plantard admitted under oath that he had fabricated everything, including Pelat's involvement with the Priory of Sion.<ref name="lepoint"/><ref name="Philippe Laprévôte 1996 p. 140">Philippe Laprévôte, "Note sur l’actualité du Prieuré de Sion", in: ''Politica Hermetica'', Nr. 10 (1996), pp. 140–151.</ref> Plantard was threatened with legal action by the Pelat family and therefore disappeared to his house in ]. He was 74 years old at the time. Nothing more was heard of him until he died in Paris on 3 February 2000.<ref name="Octonovo">Laurent "Octonovo" Buchholtzer, "Pierre Plantard, Geneviève Zaepfell and the Alpha-Galates", in: ''Actes du Colloque 2006'', Oeil-du-Sphinx, 2007.</ref> | |||

| Although these authors recognised that the history of the Protocols may be linked to the Priory's, they did not go so far as suggest that it proved anything about its continued existence. | |||

| ===Revival attempts=== | |||

| Accepting these hypotheses as facts, some fringe ] viewed the Priory of Sion as a fulfillment of prophesies found in the ] and further proof of an ] conspiracy of epic proportions. | |||

| On 27 December 2002, an open letter announced the revival of the Priory of Sion as an ] esoteric society, which stated that: "The Commanderies of Saint-Denis, Millau, Geneva and Barcelona are fully operative. According to the Tradition, the first Commanderie is under the direction of a woman", claiming there were 9,841 members.<ref>Bulletin ''Pégase'' N°06, Janvier/Mars 2003.</ref> It was signed by ] (who claims to be Plantard's former private secretary) under the title of General Secretary,<ref name="Buccholtzer, 2008">Laurent "Octonovo" Buchholtzer, ''Rennes-le-Château, une Affaire Paradoxale'', Oeil-du-Sphinx, 2008.</ref> and by "P. Plantard" (Le Nautonnier, G. Chyren). Sandri is a well-versed ] who has spent his life infiltrating esoteric societies only to get expelled from them.<ref name="Buccholtzer, 2008"/> After interviewing Sandri, independent researcher Laurent Octonovo Buchholtzer wrote: | |||

| {{quote|I’ve personally met this Gino Sandri on one occasion, and I had the opportunity to have a really good talk with him, but I think that he's simply seeking attention. He seemed to me to be something of a mythomaniac, which would certainly be an excellent qualification for being Secretary of the Priory of Sion. During our conversation he said something in passing that I found quite extraordinary. He said, “Ultimately, what is the Priory of Sion? It's nothing more than a well-known brand name, but with goodness knows what behind it?” He gave a good brief account of the phenomenon of the Priory of Sion. Thanks to Dan Brown, hundreds of millions of people now have “brand awareness”, and several million of them seem to take it seriously.<ref name="Octonovo"/>}} | |||

| However, since modern historians do not accept ''Holy Blood, Holy Grail'' as a serious contribution to scholarship, all these claims are regarded as being part of an intriguing but dubious ]. French authors like Franck Marie (1978), Jean-Luc Chaumeil (1979, 1984, 1992) and Pierre Jarnac (1985, 1988) have never taken Pierre Plantard and the Priory of Sion as seriously as Baigent, Lincoln and Leigh, always concluding that it was all a hoax in their respective books and outlining the reasons for their verdicts that these authors never reported comprehensively since their books were pro-conspiracy theory oriented. | |||

| Since 2016, Italian ] ] has claimed to be the Grand Master of the Priory of Sion.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Grand Master {{!}} Priory of Sion |url=http://www.prieure-de-sion.com/4/the_grand_master_1131456.html |website=www.prieure-de-sion.com/}}</ref> | |||

| In 1989, Pierre Plantard tried to salvage his reputation and agenda by claiming that the Priory had actually been founded in 1681 at Rennes-le-Chateau. This last revival did not succeed and in 1993, thinking he was dealing with a ]-like organization at first, Judge Thierry Jean-Pierre investigated and suppressed all activities related to the Priory of Sion hoax. | |||

| ===''The Da Vinci Code''=== | |||

| Most recently, due to Dan Brown's bestselling novel, ], there has been a new level of public interest in the Priory of Sion. | |||

| As a result of ]'s best-selling 2003 ] novel '']''<ref name="Brown 2003" /> and the subsequent 2006 ], there was a new level of public interest in the Priory of Sion. Brown's novel promotes the mythical version of the Priory but departs from the ultimate conclusions presented in ''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail''. Rather than plotting to create a Federal Europe ruled by a ] ] descended from the ], the Priory of Sion initiates its members into a ] seeking to restore the ] necessary for a complete understanding of ], which was supposedly suppressed by the Catholic Church. The author has presented this speculation as fact in his non-fiction preface, as well as in his public appearances and interviews. | |||

| ===Alleged Grand Masters of the Priory of Sion=== | |||

| # ] (]-]) | |||

| # ] (1220-]) | |||

| # ] (1266-]) | |||

| # ] (1307-]) | |||

| # ] (1336-]) | |||

| # ] (1351-]) | |||

| # ] (1366-]) | |||

| # ] (1398-]) | |||

| # ] (1418-]) | |||

| # ] (1480-]) | |||

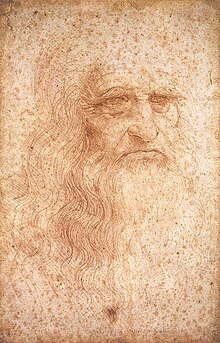

| # ] AKA ] (1483-]) | |||

| # ] (1510-]) | |||

| # ] (1519-]) | |||

| # ] (1527-]) | |||

| # ] AKA ](1556-]) | |||

| # ] & ] (1566-]) | |||

| # ] (1575-]) | |||

| # ] (1595-]) | |||

| # ] (1637-]) | |||

| # ] (1654-]) | |||

| # ] (1691-]) | |||

| # ] (1727-]) | |||

| # ] (1746-]) | |||

| # ] (1780-]) | |||

| # ] (1801-]) | |||

| # ] (1844-]) | |||

| # ] (1885-]) | |||

| # ] (1918-]) | |||

| Furthermore, in their 1987 sequel '']'',<ref name="Baigent 1987"/> Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh suggested that there was a current conflict between the Priory of Sion and the ], which they speculated might have originated from an earlier rivalry between the ] and ] during the ]. However, for the dramatic structure of ''The Da Vinci Code'', Brown chose the ] Catholic ] ] as the ]-like nemesis of the Priory of Sion, despite the fact that no author had ever argued that there is a conflict between these two groups. | |||

| ===''The Sion Revelation''=== | |||

| A second List of the Grand Masters of the Priory of Sion that included the names of Roger Patrice Pelat and Thomas Plantard appeared in 1989 - but it should not be confused with the above list that belonged to a version of the Priory of Sion that Plantard rejected. When Plantard tried to make a comeback and a revival of the Priory of Sion in 1989 following his retirement in 1984 he claimed that the above list was bogus and a part of the ''"Secret Files"'', which by then had been exposed as a fraud by French researchers and authors. | |||

| Further conspiracy theories were reported in the 2006 non-fiction book ''The Sion Revelation: The Truth About the Guardians of Christ's Sacred Bloodline'' by ] and Clive Prince (authors of the 1997 non-fiction book '']'', the principal source for Dan Brown's claims about hidden messages in the work of ]).<ref name="Picknett 2006"/> They accepted that the pre-1956 history of the Priory of Sion was a hoax created by Plantard, and that his claim that he was a Merovingian ] was a lie. However, they insist that this was part of a complex ] intended to distract the public from the hidden agenda of Plantard and his ]. They argue that the Priory of Sion was a ] for one of the many crypto-political societies which have been plotting to create a "]" in line with French ] ]'s ] vision of an ideal form of government. | |||

| === |

===''Bloodline'' movie=== | ||

| The 2008 documentary '']''<ref>''Bloodline'' DVD (Cinema Libre, 2008, 113 minutes). The documentary was originally released in cinemas on 9 May 2008.</ref> by 1244 Films and producers Bruce Burgess, a British filmmaker with an interest in ] claims and Rene Barnett, a Los Angeles researcher and television and filmmaker, expands on the "]" hypothesis and other elements of ''The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail''.<ref>Ronald H. Fritze, ''Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-Religions'', pp. 8–9 (Reaktion Books, 2009). {{ISBN|1-86189-430-9}}</ref> Accepting as valid the testimony of an amateur archaeologist codenamed "Ben Hammott" relating to his discoveries made in the vicinity of ] since 1999; The film speculates that Ben has found the treasure of ]: a mummified corpse, which Hammott claimed to believe is ], in an underground tomb purportedly connected to both the Knights Templar and the Priory of Sion. In the film, Burgess interviews several people with alleged connections to the Priory of Sion, including a Gino Sandri and Nicolas Haywood. A book by one of the documentary's researchers, Rob Howells, entitled ''Inside the Priory of Sion: Revelations from the World's Most Secret Society – Guardians of the Bloodline of Jesus'' presented the version of the Priory of Sion as given in the 2008 documentary,<ref>Robert Howells, ''Inside The Priory of Sion: Revelations From The World's Most Secret Society – Guardians of The Bloodline of Jesus'' (Watkins Publishing, 2011). {{ISBN|1-78028-017-3}}</ref> which contained several erroneous assertions, such as the claim that Plantard believed in the Jesus bloodline hypothesis.<ref>"In ] Plantard claimed that the key to the mystery of Rennes-le-Château was that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were married and had children." Howells, page 2.</ref> On 21 March 2012, ahead of an impending public outing on the internet, Ben Hammott confessed and apologised on NightVision Radio, a podcast hosted by Bloodline Producer Rene Barnett (using his real name Bill Wilkinson) that everything to do with the tomb and related artifacts was a hoax; revealing that the actual tomb was now destroyed, being part of a full sized set located in a warehouse in England.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120320110246/http://latalkradio.com/Rene.php |date=20 March 2012 }}, entry dated Wednesday, 21 March 2012</ref> | |||

| ==Alleged Grand Masters== | |||

| '''''Et in Arcadia ego...''''' is supposedly the official motto of both the Plantard family and the Priory of Sion, according to a claim that first appeared in 1964. '']'' is a Latin phrase, that most famously appears as a tomb inscription on the ''ca.'' ] ] painting, ''The Arcadian Shepherds'', by French painter ]. It literally means, "And I in Arcadia." However, the addition of the ellipsis (which was not there in the Poussin painting), suggests a missing word. Although it would not be needed in Latin grammar, ''sum'' has been one suggested completion to mean: "And I am in Arcadia." Furthermore, it has been theorized by Richard Andrews and Paul Schellenberger that the completed phrase ''Et in Arcadia ego sum'' is an ] for ''Arcam Dei Tango Iesu'' which means "I touch the tomb of God - Jesus." The implication being that the tomb contains the ] of Jesus, the mortal prophet of God. Regardless of the accuracy of this extraordinary claim, it is not considered part of the official history of the painting by Poussin that contains the phrase, which is well documented. | |||

| The notional version of the Priory of Sion first referred to during the 1960s was supposedly led by a "Nautonnier", an ] word for a ], which means ] in their internal esoteric nomenclature. The following list of Grand Masters is derived from the '']'' compiled by Plantard under the ''nom de plume'' of "Philippe Toscan du Plantier" in 1967. All those named on this list had died before that date. All but two are also found on lists of alleged “]s” (supreme heads) and “distinguished members” of the ] that circulated in France at the time when Plantard was in touch with this ]. Most of those named share the common thread of being known for having an interest in the ] or ].<ref name="Introvigne 2005"/> | |||

| ], alleged to be the Priory of Sion's 12th Grand Master]] | |||

| The ''Dossiers Secrets'' asserted that the Priory of Sion and the ] always shared ] until a ] occurred during the "]" incident in 1188. Following that event, the Grand Masters of the Priory of Sion are listed in ] as being: | |||

| ==Cultural influences== | |||

| # ] (1188–1220) | |||

| # Marie de Saint-Clair (1220–1266)- Marie de Saint-Clair (1192-1266), daughter of Robert de Saint-Clair and Isabel Levis, became Grand Mistress of the Priory from 1220 to her death (3). | |||

| # ] (1266–1307) | |||

| # ] (1307–1336) | |||

| # ] (1336–1351) | |||

| # Jean de Saint-Clair (1351–1366) | |||

| # ] (1366–1398) | |||

| # ] (1398–1418) | |||

| # ] (1418–1480) | |||

| # ] (1480–1483) | |||

| # ] (1483–1510) | |||

| # ] (1510–1519) | |||

| # ] (1519–1527) | |||

| # ] (1527–1575) | |||

| # ] (1575–1595) | |||

| # ] (1595–1637) | |||

| # ] (1637–1654) | |||

| # ] (1654–1691) | |||

| # ] (1691–1727) | |||

| # ] (1727–1746) | |||

| # ] (1746–1780) | |||

| # ] (1780–1801) | |||

| # ] (1801–1844) | |||

| # ] (1844–1885) | |||

| # ] (1885–1918) | |||

| # ] (1918–1963) | |||

| A later document, ''Le Cercle d'Ulysse'',<ref name="Jean Delaude 1994"/> identifies ], a prominent ] priest who Plantard had worked for as a ] during World War II,<ref name="Introvigne 2005" /> as the Grand Master following Cocteau's death. Plantard himself is later identified as the next Grand Master. | |||

| The Priory of Sion has had several influences on popular culture, not all of them entirely accurate or serious: | |||

| Pierre Plantard rejected the ''Dossiers Secrets'' from the late 1980s and gave the Priory of Sion a completely different pedigree. For example the link with the Knights Templar was abolished, although the connection with Godfrey of Bouillon remained. Plantard attempted to make a comeback. The second list appeared in ''Vaincre'' No. 3, September 1989, p. 22 <ref>Jean-Jacques Bedu, ''Les Sources Secrets du Da Vinci Code'', page 250, Editions du Rocher, 2005.</ref> which included the names of the deceased Roger-Patrice Pelat, and his own son Thomas Plantard de Saint-Clair: | |||

| * The Priory, portrayed as more of a ] ], plays a large part in ]'s novel '']''. | |||

| # Jean-Tim Negri d'Albes (1681–1703) | |||

| * The Priory was the template for the Grail order in the ] book series and, more loosely, the ] in the ] television series. | |||

| # François d'Hautpoul (1703–1726) | |||

| # ] (1726–1766) | |||

| # ] (1766–1780) | |||

| # ] (1780–1801) | |||

| # ] (1801–1844) | |||

| # ] (1844–1885) | |||

| # ] (1885–1918) | |||

| # ] (1918–1963) | |||

| # François Balphangon (1963–1969) | |||

| # John Drick (1969–1981) | |||

| # ] (1981) | |||

| # ] (1984–1985) | |||

| # {{ill|Roger-Patrice Pelat|fr|}} (1985–1989) | |||

| # ] (1989) | |||

| # Thomas Plantard de Saint-Clair (1989) | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| ==External links and references== | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh and Henry Lincoln. ''Holy Blood, Holy Grail'', 1982 (ISBN 055212138) | |||

| * Official website of the | |||

| * Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh and Henry Lincoln. ''The Messianic Legacy'', 1987 (1989 reissue: ISBN 0440203198) The sequel to ''Holy Blood, Holy Grail''. | |||

| * ]. ''''. '']'', Volume 28, No 6. (November-December 2004) Retrieved on 2020-09-21 | |||

| * Richard Andrews and Paul Schellenberger. ''The Tomb of God: The Body of Jesus and the Solution to a 2,000-year-old Mystery'', 1996 (ISBN 0316879975) | |||

| * ]. ''''. ] (2005) Retrieved on 2008-06-20 | |||

| * Steven Mizrach. '''' A critical analysis of the Priory of Sion mystery. | |||

| * Netchacovitch, Johan. ''''. ''Gazette of Rennes-le-Château'' (12 April 2006). Retrieved on 2008-06-20 | |||

| * Paul Smith. '''' The most extensive resource for a debunking of the Priory of Sion hoax. | |||

| * Netchacovitch, Johan. ''''. ''Gazette of Rennes-le-Château'' (4 November 2006). Retrieved on 2008-06-20 | |||

| * Lisa Shea. | |||

| * Netchacovitch, Johan. ''. ''Gazette de Rennes-le-Château'' (27 March 2017) Retrieved on 2020-09-21 | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Priory Of Sion}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:44, 20 January 2025

French fraternal organization associated with a literary hoax| This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (October 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Prieuré de Sion (French pronunciation: [pʁijœʁe də sjɔ̃]), translated as Priory of Sion, was a fraternal organisation founded in France and dissolved in 1956 by Pierre Plantard in his failed attempt to create a prestigious neo-chivalric order. In the 1960s, Plantard began claiming that his self-styled order was the latest front for a secret society founded by crusading knight Godfrey of Bouillon, on Mount Zion in the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1099, under the guise of the historical monastic order of the Abbey of Our Lady of Mount Zion. As a framework for his grandiose assertion of being both the Great Monarch prophesied by Nostradamus and a Merovingian pretender, Plantard further claimed the Priory of Sion was engaged in a centuries-long benevolent conspiracy to install a secret bloodline of the Merovingian dynasty on the thrones of France and the rest of Europe. To Plantard's surprise, all of his claims were fused with the notion of a Jesus bloodline and popularised by the authors of the 1982 speculative nonfiction book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, whose conclusions would later be borrowed by Dan Brown for his 2003 mystery thriller novel The Da Vinci Code.

After attracting varying degrees of public attention from the late 1960s to the 1980s, the mythical history of the Priory of Sion was exposed as a ludibrium — an elaborate hoax in the form of an esoteric puzzle — created by Plantard as part of his unsuccessful stratagem to become a respected, influential and wealthy player in French esotericist and monarchist circles. Pieces of evidence presented in support of the historical existence and activities of the Priory of Sion before 1956, such as the so-called Dossiers Secrets d'Henri Lobineau, were discovered to have been forged and then planted in various locations around France by Plantard and his accomplices. However, Pierre Plantard himself disowned Dossiers Secrets d'Henri Lobineau when he described it as being the work of Philippe Toscan du Plantier who had allegedly been arrested for taking LSD, in another attempt to form another version of the Priory of Sion from 1989, also reviving the organ “Vaincre”, that lasted for four issues.

Despite the "Priory of Sion mysteries" having been exhaustively debunked by journalists and scholars as France's greatest 20th-century literary hoax, many conspiracy theorists still persist in believing that the Priory of Sion was a millennium-old cabal concealing a religiously subversive secret. A few independent researchers outside of academia claim, based on alleged insider information, that the Priory of Sion continues to operate as a conspiratorial secret society to this day. Some skeptics express concern that the proliferation and popularity of pseudohistorical books, websites and films inspired by the Priory of Sion hoax contribute to the problem of unfounded conspiracy theories becoming mainstream; while others are troubled by how these works romanticize the reactionary ideologies of the far right.

History

The fraternal organisation was founded in the town of Annemasse, Haute-Savoie, in eastern France in 1956. The 1901 French law of Associations required that the Priory of Sion be registered with the government; although the statutes and the registration documents are dated 7 May 1956, the registration took place at the subprefecture of Saint-Julien-en-Genevois on 25 June 1956 and recorded in the Journal Officiel de la République Française on 20 July 1956. The headquarters of the Priory of Sion and its journal Circuit were based in the apartment of Plantard, in a social housing block known as Sous-Cassan newly constructed in 1956.

The founders and signatories inscribed with their real names and aliases were Pierre Plantard, also known as "Chyren", and André Bonhomme, also known as "Stanis Bellas". Bonhomme was the President while Plantard was the Secretary General. The registration documents also included the names of Jean Deleaval as the Vice-President and Armand Defago as the Treasurer. The choice of the name "Sion" was based on a popular local feature, a hill south of Annemasse in France, known as Mont Sion, where the founders intended to establish a spiritual retreat center. The accompanying title to the name was "Chevalerie d'Institutions et Règles Catholiques d'Union Indépendante et Traditionaliste": this subtitle forms the acronym CIRCUIT and translates in English as "Chivalry of Catholic Rules and Institutions of Independent and Traditionalist Union". The statutes of the Priory of Sion indicate its purpose was to allow and encourage members to engage in studies and mutual aid. The articles of the association expressed the goal of creating a Traditionalist Catholic chivalric order.

Article 7 of the statutes of the Priory of Sion stated that its members were expected "to carry out good deeds, to help the Roman Catholic Church, teach the truth, defend the weak and the oppressed". Towards the end of 1956 the association had planned to forge partnerships with the local Catholic Church of the area which would have involved a school bus service run by both the Priory of Sion and the church of Saint-Joseph in Annemasse. Plantard is described as the President of the Tenants' Association of Annemasse in the issues of Circuit. The bulk of the activities of the Priory of Sion bore no resemblance to the objectives as outlined in its statutes: Circuit, the official journal of the Priory of Sion, was indicated as a news bulletin of an "organisation for the defence of the rights and the freedom of affordable housing" rather than for the promotion of chivalry-inspired charitable work. The first issue of the journal is dated 27 May 1956, and, in total, twelve issues appeared. Some of the articles took a political position in the local council elections. Others criticised and even attacked real-estate developers of Annemasse.

According to a letter written by Léon Guersillon the Mayor of Annemasse in 1956, contained in the folder holding the 1956 Statutes of the Priory of Sion in the subprefecture of Saint-Julien-en-Genevois, Plantard was given a six-month sentence in 1953 for fraud. The formally registered association was dissolved some time after October 1956 but intermittently revived for different reasons by Plantard between 1961 and 1993, though in name and on paper only. The Priory of Sion is considered dormant by the subprefecture because it has indicated no activities since 1956. According to French law, subsequent references to the Priory bear no legal relation to that of 1956 and no one, other than the original signatories, is entitled to use its name in an official capacity. André Bonhomme played no part in the association after 1956. He officially resigned in 1973 when he heard that Plantard was linking his name with the association. In light of Plantard's death in 2000, there is no one who is currently alive who has official permission to use the name.

Myth

Plantard's plot

Plantard set out to have the Priory of Sion perceived as a prestigious esoteric Christian chivalric order, whose members would be people of influence in the fields of finance, politics and philosophy, devoted to installing the "Great Monarch", prophesied by Nostradamus, on the throne of France. Plantard's choice of the pseudonym "Chyren" was a reference to "Chyren Selin", Nostradamus's anagram for the name for this eschatological figure.

Between 1961 and 1984, Plantard contrived a mythical pedigree for the Priory of Sion claiming that it was the offshoot of a real Catholic religious order housed in the Abbey of Our Lady of Mount Zion, which had been founded in the Kingdom of Jerusalem during the First Crusade in 1099 and later absorbed by the Jesuits in 1617. The mistake is often made that this Abbey of Sion was a Priory of Sion, but there is a difference between an abbey and a priory. Calling his original 1956 group "Priory of Sion" presumably gave Plantard the later idea to claim that his organisation had been historically founded by crusading knight Godfrey of Bouillon on Mount Zion near Jerusalem during the Middle Ages.

Furthermore, Plantard was inspired by a 1960 magazine Les Cahiers de l'Histoire to center his personal genealogical claims, as found in the "Priory of Sion documents", on the Merovingian king Dagobert II, who had been assassinated in the 7th century. He also adopted "Et in Arcadia ego...", a slightly altered version of a Latin phrase that most famously appears as the title of two paintings by Nicolas Poussin, as the motto of both his family and the Priory of Sion, because the tomb which appears in these paintings resembled one in the Les Pontils area near Rennes-le-Château. This tomb would become a symbol for his dynastic claims as the last legacy of the Merovingians on the territory of Razès, left to remind the select few who have been initiated into these mysteries that the "lost king", Dagobert II, would figuratively come back in the form of a hereditary pretender.

To lend credibility to the apparently fabricated lineage and pedigree, Plantard and his friend, Philippe de Chérisey, needed to create "independent evidence". So during the 1960s, they created and deposited a series of false documents, the most famous of which was entitled Dossiers Secrets d'Henri Lobineau ("Secret Files of Henri Lobineau"), at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. During the same decade, Plantard commissioned de Chérisey to forge two medieval parchments. These parchments contained encrypted messages that referred to the Priory of Sion.

They adapted, and used to their advantage, the earlier false claims put forward by Noël Corbu that a Catholic priest named Bérenger Saunière had supposedly discovered ancient parchments inside a pillar while renovating his church in Rennes-le-Château in 1891. Inspired by the popularity of media reports and books in France about the discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls in the West Bank, they hoped this same theme would attract attention to their parchments. Their version of the parchments was intended to prove Plantard's claims about the Priory of Sion being a medieval secret society that was the source of the "underground stream" of esotericism in Europe.

Plantard then enlisted the aid of author Gérard de Sède to write a book based on his unpublished manuscript and forged parchments, alleging that Saunière had discovered a link to a hidden treasure. The 1967 book L'or de Rennes, ou La vie insolite de Bérenger Saunière, curé de Rennes-le-Château ("The Gold of Rennes, or The Strange Life of Bérenger Saunière, Priest of Rennes-le-Château"), which was later published in paperback under the title Le Trésor Maudit de Rennes-le-Château ("The Accursed Treasure of Rennes-le-Château") in 1968, became a popular read in France. It included copies of the found parchments (the originals were, of course, never produced), though it did not provide the decoded hidden texts contained within them. One of the Latin texts in the parchments was copied from the Novum Testamentum, an attempted restoration of the Vulgate by John Wordsworth and Henry White.

The other text was copied from the Codex Bezae. Based on the wording used, the versions of the Latin texts found in the parchments can be shown to have been copied from books first published in 1889 and 1895, which is problematic considering that de Sède's book was trying to make a case that these documents were centuries old. In 1969, English scriptwriter, producer and researcher Henry Lincoln became intrigued after reading Le Trésor Maudit. He discovered one of the encrypted messages, which read "À Dagobert II Roi et à Sion est ce trésor, et il est là mort" ("To Dagobert II, King, and to Sion belongs this treasure and he is there dead"). This was possibly an allusion to the tomb and shrine of Sigebert IV, a real or mythical son of Dagobert II which would not only prove that the Merovingian dynasty did not end with the death of the king, but that the Priory of Sion has been entrusted with the duty to protect his relics like a treasure.

Lincoln expanded on the conspiracy theories, writing his own books on the subject, and inspiring and presenting three BBC Two Chronicle documentaries between 1972 and 1979 about the alleged mysteries of the Rennes-le-Château area. In response to a tip from Gérard de Sède, Lincoln claims he was also the one who discovered the Dossiers Secrets, a series of planted genealogies which appeared to further confirm the link with the extinct Merovingian bloodline. The documents claimed that the Priory of Sion and the Knights Templar were two fronts of one unified organisation with the same leadership until 1188.

Letters in existence dating from the 1960s written by Plantard, de Chérisey and de Sède to each other confirm that the three were engaging in an out-and-out hoax. The letters describe schemes to combat criticisms of their various allegations and ways they would make up new allegations to try to keep the hoax alive. These letters (totalling over 100) are in the possession of French researcher Jean-Luc Chaumeil, who has also retained the original envelopes. A letter later discovered at the subprefecture of Saint-Julien-en-Genevois also indicated that Plantard had a criminal conviction as a con artist.

The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail

Further information: The Holy Blood and the Holy GrailAs the Chronicle documentaries on the topic became quite popular and generated thousands of responses, Lincoln then joined forces with Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh for further research. This led them to the pseudohistorical Dossiers Secrets at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which though alleging to portray hundreds of years of medieval history, were actually all written by Plantard and de Chérisey under the pseudonym of "Philippe Toscan du Plantier".

Unaware that the documents had been forged, Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh used them as a major source for their 1982 speculative nonfiction book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, in which they presented the following myths as facts to support their hypotheses:

- there is a secret society known as the Priory of Sion, which has a long history starting in 1099, and had illustrious Grand Masters including Leonardo da Vinci and Isaac Newton;

- it created the Knights Templar as its military arm and financial branch; and

- it is devoted to installing the Merovingian dynasty, that ruled the Franks from 457 to 751, on the thrones of France and the rest of Europe.

The authors re-interpreted the Dossiers Secrets in the light of their own interest in questioning the Catholic Church's institutional reading of Judeo-Christian history. Contrary to Plantard's initial Franco-Israelist claim that the Merovingians were only descended from the Tribe of Benjamin, they asserted that:

- the Priory of Sion protects Merovingian dynasts because they may be the lineal descendants of the historical Jesus and his alleged wife, Mary Magdalene, traced further back to King David;

- the legendary Holy Grail is simultaneously the womb of saint Mary Magdalene and the sacred royal bloodline she gave birth to; and

- the Church tried to kill off all remnants of this bloodline and their supposed guardians, the Cathars and the Templars, so popes could hold the episcopal throne through the apostolic succession of Peter without fear of it ever being usurped by an antipope from the hereditary succession of Mary Magdalene.

The authors therefore concluded that the modern goals of the Priory of Sion are:

- the public revelation of the tomb and shrine of Sigebert IV as well as the lost treasure of the Temple in Jerusalem, which supposedly contains genealogical records that prove the Merovingian dynasty was of the Davidic line, to facilitate Merovingian restoration in France;

- the re-institutionalization of chivalric knighthood and the promotion of pan-European nationalism;

- the establishment of a theocratic "United States of Europe": a Holy European Empire politically and religiously unified through the imperial cult of a Merovingian Great Monarch who occupies both the throne of Europe and the Holy See; and

- the actual governance of Europe residing with the Priory of Sion through a one-party European Parliament.

The authors incorporated the antisemitic and anti-Masonic tract known as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion into their story, concluding that it was actually based on the master plan of the Priory of Sion. They presented it as the most persuasive piece of evidence for the existence and activities of the Priory of Sion by arguing that:

- the original text on which the published version of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was based had nothing to do with Judaism or an "international Jewish conspiracy". It issued from a Masonic body practicing the Scottish Rite which incorporated the word "Zion" in its name;

- the original text was not intended to be released publicly, but was a program for gaining control of Freemasonry as part of a strategy to infiltrate and reorganize church and state according to esoteric Christian principles;

- after a failed attempt to gain influence in the court of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, Sergei Nilus changed the original text to forge an inflammatory tract in 1903 to discredit the esoteric clique around Papus by implying they were Judaeo-Masonic conspirators; and

- some esoteric Christian elements in the original text were ignored by Nilus and hence remained unchanged in the antisemitic canard he published.

In reaction to this memetic synthesis of investigative journalism with religious conspiracism, many secular conspiracy theorists added the Priory of Sion to their list of secret societies collaborating or competing to manipulate political happenings from behind the scenes in their bid for world domination. Some occultists speculated that the emergence of the Priory of Sion and Plantard closely follows The Prophecies by M. Michel Nostradamus (unaware that Plantard was intentionally trying to fulfill them). Fringe Christian eschatologists countered that it was a fulfilment of prophecies found in the Book of Revelation and further proof of an anti-Christian conspiracy of epic proportions.

Historians and scholars from related fields do not accept The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail as a serious dissertation. French authors like Franck Marie (1978), Pierre Jarnac (1985), (1988), Jean-Luc Chaumeil (1994), and more recently Marie-France Etchegoin and Frédéric Lenoir (2004), Massimo Introvigne (2005), Jean-Jacques Bedu (2005), and Bernardo Sanchez Da Motta (2005), have never taken Plantard and the Priory of Sion as seriously as Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh. They eventually concluded that it was all a hoax, outlining in detail the reasons for their verdict, and giving detailed evidence that the Holy Blood authors had not reported comprehensively. They imply that this evidence had been ignored by Lincoln, Baigent, and Leigh to bolster the mythical version of the Priory's history that was developed by Plantard during the early 1960s after meeting author Gérard de Sède.

The Messianic Legacy

In 1986, Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh published The Messianic Legacy, a sequel to The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. The authors assert that the Priory of Sion is not only the archetypal cabal but an ideal repository of the cultural legacy of Jewish messianism that could end the “crisis of meaning” within the Western world by providing a Merovingian sacred king as a messianic figure in which the West and, by extension, humanity can place its trust. However, the authors are led to believe by Plantard that he has resigned as Grand Master of the Priory of Sion in 1984 and that the organisation has since gone underground in reaction to both an internal power struggle between Plantard and an “Anglo-American contingent” as well as a campaign of character assassination against Plantard in the press and books written by skeptics.

Although Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh remain convinced that the pre-1956 history of the Priory of Sion is true, they confess to the possibility that all of Plantard's claims about a post-1956 Priory of Sion were part of an elaborate hoax to become a respected, influential and wealthy player in French esotericist and monarchist circles.

Revised myth

In 1989, Plantard tried but failed to salvage his reputation and agenda as a mystagogue in esotericist circles by claiming that the Priory of Sion had actually been founded in 1681 at Rennes-le-Château, and was focused more on harnessing the paranormal power of ley lines and sunrise lines, and a promontory called "Roc Noir" (Black Rock) in the area, than installing a Merovingian pretender on the restored throne of France. In 1990, Plantard revised himself by claiming he was only descended from a cadet branch of the line of Dagobert II, while arguing that the direct descendant was really Otto von Habsburg.

Pelat Affair

In September 1993, while investigative judge Thierry Jean-Pierre was investigating the activities of multi-millionaire Roger-Patrice Pelat in the context of the Pechiney-Triangle Affair, he was informed that Pelat may have once been Grand Master of a secret society known as the Priory of Sion. Pelat's name had been on Plantard's list of Grand Masters since 1989. In fact, Pelat had died in 1989, while he was being indicted for insider trading. Following a long established pattern of using dead people's names, Plantard "recruited" the "initiate" Pelat soon after his death and included him as the most recent Priory of Sion Grand Master. Plantard had first claimed that Pelat had been a Grand Master in a Priory of Sion pamphlet dated 8 March 1989, then claimed it again later in a 1990 issue of Vaincre, the revived publication of Alpha Galates, a pseudo-chivalric order created by Plantard in Vichy France to support the "National Revolution".

Pelat had been a friend of François Mitterrand, then President of France, and at the centre of a scandal involving French Prime Minister Pierre Bérégovoy. As an investigative judge, Jean-Pierre could not dismiss any information brought to his attention pertaining to the case, especially if it might have led to a scandal similar to the one implicating an illegal pseudo-Masonic lodge named Propaganda Due in the 1982 Banco Ambrosiano bank failure in Italy, Jean-Pierre ordered a search of Plantard's home. The search turned up a hoard of false documents, including some proclaiming Plantard the true king of France. Plantard admitted under oath that he had fabricated everything, including Pelat's involvement with the Priory of Sion. Plantard was threatened with legal action by the Pelat family and therefore disappeared to his house in southern France. He was 74 years old at the time. Nothing more was heard of him until he died in Paris on 3 February 2000.

Revival attempts

On 27 December 2002, an open letter announced the revival of the Priory of Sion as an integral traditionalist esoteric society, which stated that: "The Commanderies of Saint-Denis, Millau, Geneva and Barcelona are fully operative. According to the Tradition, the first Commanderie is under the direction of a woman", claiming there were 9,841 members. It was signed by Gino Sandri (who claims to be Plantard's former private secretary) under the title of General Secretary, and by "P. Plantard" (Le Nautonnier, G. Chyren). Sandri is a well-versed occultist who has spent his life infiltrating esoteric societies only to get expelled from them. After interviewing Sandri, independent researcher Laurent Octonovo Buchholtzer wrote: