| Revision as of 04:47, 1 August 2006 view source71.39.11.138 (talk) →Other Resources← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:00, 14 January 2025 view source Person by the Tuatnark (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users915 edits Expanded bare URL | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|East Slavic language}} | |||

| {{Infobox Language | |||

| {{distinguish|Rusyn language|text=the ]}} | |||

| |name=Russian | |||

| {{redirect-distinguish|Great Russian|Great Russia}} | |||

| |nativename=русский язык ''russkiy yazyk'' | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| |states=], ], ], ] and the ]. | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| |speakers=primary language: about 145 million<br>secondary language: 110 million (1999 WA, 2000 WCD) | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} | |||

| |rank=8 (native) | |||

| {{Infobox language | |||

| |familycolor=Indo-European | |||

| | name = Russian | |||

| |fam2=] | |||

| | states = ], other areas of the ] | |||

| |fam3=] | |||

| | nativename = {{lang|ru|русский язык}}{{efn|On the history of using "русский" ("''russkiy''") and "российский" ("''rossiyskiy''") as the Russian adjectives denoting "Russian", see: ]. 2005. Русский{{nbs}}– Российский. История, динамика, идеология двух атрибутов нации (pp. 216–227). В поисках единства. Взгляд филолога на проблему истоков Руси., 2005. {{cite web|url=http://krotov.info/libr_min/19_t/ru/bachev.htm|access-date=25 January 2014|language=ru|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140218214456/http://krotov.info/libr_min/19_t/ru/bachev.htm|archive-date=18 February 2014|script-title=ru:РУССКИЙ – РОССИЙСКИЙ}}. On the 1830s change in the Russian name of the Russian language and its causes, see: ]. 2012. The Change of the Name of the Russian Language in Russian from Rossiiskii to Russkii: Did Politics Have Anything to Do with It? (pp.{{nbs}}73–96). ''Acta Slavica Iaponica''. Vol 32, {{cite web|url=http://src-h.slav.hokudai.ac.jp/publictn/acta/32/04Kamusella.pdf|title=The Change of the Name of the Russian Language in Russian from Rossiiskii to Russkii: Did Politics Have Anything to Do with It?|access-date=7 January 2013|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130518165147/http://src-h.slav.hokudai.ac.jp/publictn/acta/32/04Kamusella.pdf|archive-date=18 May 2013}}}}<br/> | |||

| |fam4=] | |||

| | pronunciation = {{IPA|ru|ˈruskʲɪi̯ jɪˈzɨk||Ru-russkiy jizyk.ogg}} | |||

| |script=] | |||

| | region = | |||

| |nation=], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| | ethnicity = | |||

| |agency=] | |||

| | speakers = ]: {{Significant figures|147.566020|3}} million | |||

| |iso1=ru|iso2=rus|iso3=rus|map=]<center><small>Countries of the world where Russian is spoken.</center></small>}} | |||

| | date = 2020 census | |||

| | ref = e27 | |||

| | speakers2 = ]: {{Significant figures|107.826500|3}} million (2020 census)<ref name=e27/><br/>Total: {{sigfig|255.392520|3}} million (2020 census)<ref name=e27/> | |||

| | speakers_label = Speakers | |||

| | familycolor = Indo-European | |||

| | fam2 = ] | |||

| | fam3 = ] | |||

| | fam4 = ] | |||

| | ancestor = ] | |||

| | ancestor2 = ] | |||

| | ancestor3 = ] | |||

| | ancestor4 = ] | |||

| | script = ] (])<br/>] | |||

| | nation = {{Collapsible list |titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left;|title=]| | |||

| | | |||

| * {{flag|Russia}} <small>(state)</small><ref name=RusConst>{{cite web |url=http://www.constitution.ru/en/10003000-01.htm |title=Article 68. Constitution of the Russian Federation |website=Constitution.ru |access-date=18 June 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130606071041/http://www.constitution.ru/en/10003000-01.htm |archive-date=6 June 2013}}</ref> | |||

| * {{flag|Belarus}} <small>(co-official)</small><ref name=Belarus>{{cite web |url=http://president.gov.by/en/press19329.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070502115338/http://president.gov.by/en/press19329.html|archive-date=2 May 2007 |title=Article 17. Constitution of the Republic of Belarus |website=President.gov.by |date=11 May 1998 |access-date=18 June 2013}}</ref> | |||

| * {{flag|Kazakhstan}} <small>(co-official)</small><ref name=Kazakhstan>{{cite web |first=N. |last=Nazarbaev | |||

| | url=http://www.constcouncil.kz/eng/norpb/constrk/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071020060732/http://www.constcouncil.kz/eng/norpb/constrk/ |archive-date=20 October 2007 |title=Article 7. Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan |website=Constcouncil.kz |date=4 December 2005 |access-date=18 June 2013}}</ref><br/> | |||

| * {{flag|Kyrgyzstan}} <small>(co-official)</small><ref name=Kyrgyzstan>{{Cite web|url=https://www.gov.kg/ky|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121222125830/http://www.gov.kg/?page_id=263|url-status=dead|title=Официальный сайт Правительства КР|archive-date=22 December 2012|website=Gov.kg|access-date=16 February 2020}}</ref> | |||

| * {{flag|Tajikistan}} <small>(as inter-ethnic language designated by the constitution)</small><ref>{{cite web |title=КОНСТИТУЦИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ ТАДЖИКИСТАН |url=http://prokuratura.tj/ru/legislation/the-constitution-of-the-republic-of-tajikistan.html |website=prokuratura.tj |publisher=Parliament of Tajikistan |access-date=9 January 2020 |archive-date=24 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210224035434/http://prokuratura.tj/ru/legislation/the-constitution-of-the-republic-of-tajikistan.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| <br />{{Collapsible list |titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left;|title=As inter-ethnic language but with no official status, or ]| | |||

| '''Russian''' (Russian: {{lang|ru|русский язык, ''russkiy yazyk''}}, {{IPA|}} {{Audio|Ru-russkiy jizyk.ogg|listen}}) is the most widely spoken language of ] and the most widespread of the ]. | |||

| * {{flag|Uzbekistan}}{{efn|Under the laws of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Russian language is not offered any status in terms of official language. The provisions only state that "Under request of citizens the text of document compiled by state notary or person acting as a notary shall be issued on Russian and if possible on other acceptable language" {{cite web |url=https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b4d328.html |title=Uzbekistan: Law "On Official Language" |access-date=13 November 2021 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190508060700/https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b4d328.html |archive-date=8 May 2019}}}} <small>(as inter-ethnic language despite having no ''de jure'' status)</small><ref name="AA">{{cite web |author=Юрий Подпоренко |title=Бесправен, но востребован. Русский язык в Узбекистане |url=http://mytashkent.uz/2015/04/27/bespraven-no-vostrebovan-russkij-yazyk-v-uzbekistane/ |year=2001 |publisher=Дружба Народов |access-date=27 May 2016 |url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160513012627/http://mytashkent.uz/2015/04/27/bespraven-no-vostrebovan-russkij-yazyk-v-uzbekistane/ |archive-date=13 May 2016}}</ref><ref name="Шухрат Хуррамов">{{cite web|author=Шухрат Хуррамов|title=Почему русский язык нужен узбекам? |url=http://365info.kz/2015/09/russkij-yazyk-v-uzbekistane/|date=11 September 2015 |website=365info.kz |access-date=27 May 2016 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160701175737/http://365info.kz/2015/09/russkij-yazyk-v-uzbekistane/ |archive-date=1 July 2016}}</ref><ref name="AB">{{cite web |author=Евгений Абдуллаев |title=Русский язык: жизнь после смерти. Язык, политика и общество в современном Узбекистане |url=http://magazines.russ.ru/nz/2009/4/ab21.html |year=2009 |publisher=Неприкосновенный запас |access-date=27 May 2016|url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160623201807/http://magazines.russ.ru/nz/2009/4/ab21.html|archive-date=23 June 2016}}</ref> | |||

| * {{flag|Moldova}}: | |||

| ** {{flag|Gagauzia}} <small>(co-official)</small><ref name=Gagauzia>{{cite web |url=http://www.gagauzia.md/pageview.php?l=en&idc=389&id=240 |title=Article 16. Legal code of Gagauzia (Gagauz-Yeri) |website=Gagauzia.md |date=5 August 2008 |access-date=18 June 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130513170728/http://www.gagauzia.md/pageview.php?l=en&idc=389&id=240 |archive-date=13 May 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ** ] <small>(co-official)</small> | |||

| * {{flag|Ukraine}}: | |||

| ** {{flag|Autonomous Republic of Crimea}} <small>(co-official)</small>{{efn|The status of ] and of the city of ] is ] since March 2014; Ukraine and the majority of the international community consider Crimea to be an ] of Ukraine and Sevastopol to be one of Ukraine's ], whereas Russia, on the other hand, considers Crimea to be a ] and Sevastopol to be one of Russia's three ]}}}} | |||

| <br />{{Collapsible list |titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left;|title=]| | |||

| Russian belongs to the family of ]. Within the Slavic family, Russian is one of three living members of the ], the other two being ] and ]. | |||

| * {{flag|Abkhazia}}{{efn|Abkhazia and South Ossetia are only ].|name=AbkhaziaSouthOssetia}} <small>(co-official)</small><ref name=Abkhazia>{{Cite web|url=http://www.abkhaziagov.org/ru/state/sovereignty|title=Конституция Республики Абхазия|date=18 January 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090118213155/http://www.abkhaziagov.org/ru/state/sovereignty|access-date=16 February 2020|archive-date=18 January 2009}}</ref> | |||

| Written examples of East Slavonic are attested from the 10th century onwards. While Russian preserves much of East Slavonic synthetic-inflexional structure and a ] word base, modern Russian exhibits a large stock of borrowed international vocabulary for politics, science, and technology. A language of great political importance in the 20th century, Russian is one of the official languages of the ]. | |||

| * {{flag|South Ossetia}}{{efn|name=AbkhaziaSouthOssetia}} <small>(co-official)</small><ref name=Ossetia>{{cite web |url=http://cominf.org/node/1127818105 |date=11 August 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090811021536/http://cominf.org/node/1127818105 |title=КОНСТИТУЦИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ ЮЖНАЯ ОСЕТИЯ |trans-title=Constitution of the Republic of South Ossetia |access-date=5 April 2021 |archive-date=11 August 2009}}</ref> | |||

| * {{flag|Transnistria}} <small>(state)</small><ref name="Law of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic on the Functioning of Languages on the Territory of the Moldavian SSR">{{cite web |url=http://usefoundation.org/view/436 |title=Law of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic on the Functioning of Languages on the Territory of the Moldavian SSR |publisher=U.S. English Foundation Research |date=2016 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160921034927/http://usefoundation.org/view/436 |archive-date=21 September 2016 }}</ref>}} | |||

| <br />{{Collapsible list |titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left;|title=Organizations| | |||

| <small>'''NOTE'''. Russian is written in a non-Latin script. All examples below are in the ], with transcriptions in ].</small> | |||

| {{flag|United Nations}}: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ]<br/> | |||

| ]<br/> | |||

| ]<br/> | |||

| ]<br/> | |||

| ]<br/> | |||

| ]<br/> | |||

| ]}} | |||

| | minority = {{collapsible list| | |||

| {{flag|Romania}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=RO |title=Romania : Languages of Romania |website=Ethnologue.com |date=19 February 1999 |access-date=28 January 2016 |archive-date=31 January 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130131170434/http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=RO |url-status=live }}</ref><br/> | |||

| {{flag|Armenia}}<ref name=No148>{{cite web |url=http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/ListeDeclarations.asp?NT=148&CM=8&DF=23/01/05&CL=ENG&VL=1 |title=List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148 (Status as of: 21/9/2011) |publisher=] |access-date=22 May 2012 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120522083136/http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/ListeDeclarations.asp?NT=148&CM=8&DF=23%2F01%2F05&CL=ENG&VL=1 |archive-date=22 May 2012}}</ref><br/> | |||

| {{flag|Czech Republic}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.vlada.cz/en/pracovni-a-poradni-organy-vlady/rnm/historie-a-soucasnost-rady-en-16666/ |title=National Minorities Policy of the Government of the Czech Republic |publisher=Vlada.cz |access-date=22 May 2012 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120607051111/http://www.vlada.cz/en/pracovni-a-poradni-organy-vlady/rnm/historie-a-soucasnost-rady-en-16666/ |archive-date=7 June 2012}}</ref><br/> | |||

| {{flag|Slovakia}}<ref name=No148/><br/> | |||

| {{flag|Moldova}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://deschide.md/ro/stiri/politic/78929/Pre%C8%99edintele-CCM-Constitu%C8%9Bia-nu-confer%C4%83-limbii-ruse-un-statut-deosebit-de-cel-al-altor-limbi-minoritare.htm |title=Președintele CCM: Constituția nu conferă limbii ruse un statut deosebit de cel al altor limbi minoritare |publisher=Deschide.md |access-date=22 January 2021 |archive-date=29 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210129050215/https://deschide.md/ro/stiri/politic/78929/Pre%C8%99edintele-CCM-Constitu%C8%9Bia-nu-confer%C4%83-limbii-ruse-un-statut-deosebit-de-cel-al-altor-limbi-minoritare.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><br/> | |||

| {{flag|Ukraine}}<ref name="UAConstitution"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110521190059/http://www.rada.gov.ua/const/conengl.htm |date=21 May 2011}} of the Constitution says: "The state language of Ukraine is the Ukrainian language. The State ensures the comprehensive development and functioning of the Ukrainian language in all spheres of social life throughout the entire territory of Ukraine. In Ukraine, the free development, use and protection of Russian, and other languages of national minorities of Ukraine, is guaranteed."</ref><br/> | |||

| {{flag|China}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://fujian.gov.cn/hdjl/hdjlzsk/mzzjt/mz/202209/t20220913_5991001.htm|title=少数民族的语言文字有哪些?|language=zh|website=fujian.gov.cn|date=13 September 2022|access-date=28 October 2022|author=Ethnic Groups and Religious department, Fujian Provincial Government|archive-date=28 October 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221028081421/http://fujian.gov.cn/hdjl/hdjlzsk/mzzjt/mz/202209/t20220913_5991001.htm|url-status=live|quote="我国已正式使用和经国家批准推行的少数民族文字有19种,它们是...俄罗斯文..."}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/wenzi/202108/t20210827_554992.html|title=中国语言文字概况(2021年版)|language=zh|website=moe.gov.cn|date=27 August 2021|access-date=18 December 2023|author=]|quote="...属于印欧语系的是属斯拉夫语族的俄语..."|archive-date=4 January 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240104031557/http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/wenzi/202108/t20210827_554992.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| | agency = ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ruslang.ru/agens.php?id=aims |title=Russian Language Institute |website=Ruslang.ru |access-date=16 May 2010 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100719234135/http://www.ruslang.ru/agens.php?id=aims |archive-date=19 July 2010}}</ref> | |||

| | iso1 = ru | |||

| | iso2 = rus | |||

| | iso3 = rus | |||

| | lingua = 53-AAA-ea < ]<br/>(varieties: 53-AAA-eaa to 53-AAA-eat) | |||

| | image = | |||

| | map = Russian language status and proficiency in the World.svg | |||

| | mapsize = | |||

| | mapcaption = {{legend|#000075|Official language (Stripes: Disputed territory)}} | |||

| {{legend|#007575|Spoken by >30% of the population as either 1st or a 2nd language}} | |||

| {{legend|#B3B3B3|Neither of the above}} | |||

| | notice = ] | |||

| | glotto = russ1263 | |||

| | glottorefname = Russian | |||

| | map2 = | |||

| | mapcaption2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Russian'''{{Efn|{{langx|ru|Русский язык|Russkiy yazyk|label=none}}, {{IPA|ru|ˈruskʲɪj jɪˈzɨk|pron|Ru-russkiy jizyk.ogg}}}} is an ] belonging to the ] branch of the ]. It is one of the four extant East Slavic languages,{{efn|Including ], which is sometimes classified as a ] of ] in Ukraine.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Magocsi|first=Paul Robert|title=Language and National Survival|volume=44|number=1|journal=Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas|publisher=]|pages=83–85|date=1996|jstor=41049661}}</ref>}} and is the native language of the ]. It was the ''de facto'' and ''de jure''<ref name=":1">Since 1990</ref> ] of the former ].<ref name="USSR">], 1977: Section II, Chapter 6, Article 36</ref> Russian has remained an ] of the ], ], ], ], and ], and is still commonly used as a ] in ], ], the ], ], and to a lesser extent in the ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gallup.com/poll/109228/russian-language-enjoying-boost-postsoviet-states.aspx|title=Russian Language Enjoying a Boost in Post-Soviet States|publisher=Gallup |date=1 August 2008|access-date=16 May 2010|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100518073110/http://www.gallup.com/poll/109228/Russian-Language-Enjoying-Boost-PostSoviet-States.aspx|archive-date=18 May 2010}}</ref><ref name="demoscope">{{cite journal|last=Арефьев|first=Александр|script-title=ru:Падение статуса русского языка на постсоветском пространстве|journal=Демоскоп Weekly|year=2006|issue=251|url=http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2006/0251/tema01.php|language=ru|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130308114703/http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2006/0251/tema01.php|archive-date=8 March 2013}}</ref>{{sfn|Spolsky|Shohamy|1999|p=236}}{{sfn|Isurin|2011|p=13}} | |||

| ==Classification== | |||

| Russian is a ] in the Indo-European family. From the point of view of the ], its closest relatives are ] and ], the other two national languages in the ] group. (Some academics also consider ] an East Slavic language; others consider Rusyn just a dialect.) In many places in ] and ], these languages are spoken interchangeably, and in certain areas traditional bilinguism resulted in language mixture, e.g. Surzhik in central Ukraine. | |||

| Russian has over 258 million total speakers worldwide.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/rus|title=Russian|publisher=Ethnologue|access-date=10 August 2020|archive-date=23 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210223132915/https://www.ethnologue.com/language/rus|url-status=live}}</ref> It is the ],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.tandem.net/10-most-spoken-languages-europe|title=The 10 Most Spoken Languages in Europe|work=]|date=12 September 2019|access-date=31 May 2021|archive-date=2 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210602215325/https://www.tandem.net/10-most-spoken-languages-europe|url-status=live}}</ref> the most spoken ],<ref name="language"/> as well as the most geographically widespread language of ].<ref name="language">{{cite web|url=https://learn.utoronto.ca/programs-courses/languages-and-translation/language-learning/russian|title=Russian|publisher=]|quote="Russian is the most widespread of the Slavic languages and the largest native language in Europe. Of great political importance, it is one of the official languages of the United Nations – making it a natural area of study for those interested in geopolitics."|access-date=9 July 2021|archive-date=28 June 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190628022427/https://learn.utoronto.ca/programs-courses/languages-and-translation/language-learning/russian|url-status=live}}</ref> It is the world's ], and the world's ].<ref>{{cite web |title=The World's Most Widely Spoken Languages |url=http://www2.ignatius.edu/faculty/turner/languages.htm |website=Saint Ignatius High School |access-date=17 February 2012 |location=Cleveland, Ohio |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110927062910/http://www2.ignatius.edu/faculty/turner/languages.htm |archive-date=27 September 2011}}</ref> Russian is one of two official languages aboard the ],<ref>{{cite web|last=Wakata|first=Koichi|author-link=Koichi Wakata|url=https://global.jaxa.jp/article/special/expedition/wakata01_e.html|title=My Long Mission in Space|publisher=]|quote="The official languages on the ISS are English and Russian, and when I was speaking with the Flight Control Room at JAXA's Tsukuba Space Center during ISS systems and payload operations, I was required to speak in either English or Russian."|access-date=18 July 2021|archive-date=26 April 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140426232353/https://global.jaxa.jp/article/special/expedition/wakata01_e.html|url-status=live}}</ref> one of the six ],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.un.org/en/our-work/official-languages|title=Official Languages|publisher=United Nations|quote="There are six official languages of the UN. These are Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish. The correct interpretation and translation of these six languages, in both spoken and written form, is very important to the work of the Organization, because this enables clear and concise communication on issues of global importance."|access-date=16 July 2021|archive-date=13 July 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210713075145/https://www.un.org/en/our-work/official-languages|url-status=live}}</ref> as well as the ] on the ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Most used languages online by share of websites 2024 |url=https://www.statista.com/statistics/262946/most-common-languages-on-the-internet/ |website=Statista.com |access-date=12 April 2024 |language=en |archive-date=27 April 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240427100253/https://www.statista.com/statistics/262946/most-common-languages-on-the-internet/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The basic vocabulary, principles of word-formation, and, to some extent, inflexions and literary style of Russian have been heavily influenced by ], a developed and partly adopted form of the ] ] language used by the ]. Many words in modern literary Russian are closer in form to the modern ] than to Ukrainian or Belarusian. However, the East Slavic forms have tended to remain in the various dialects that are experiencing a rapid decline. In some cases, both the ] and the ] forms are in use, with slightly different meanings. ''For details, see ] and ].'' | |||

| Russian is written using the ] of the ]; it distinguishes between consonant ]s with ] ] and those without—the so-called "soft" and "hard" sounds. Almost every ] has a hard or soft counterpart, and the distinction is a prominent feature of the language, which is usually shown in writing not by a change of the consonant but rather by changing the following vowel. Another important aspect is the ] of unstressed ]s. ], which is often unpredictable, is not normally indicated ],{{sfn|Timberlake|2004|p=17}} though an optional ] may be used to mark stress – such as to distinguish between ]ic words (e.g. {{lang|ru|замо́к}} and {{lang|ru|за́мок}} ), or to indicate the proper pronunciation of uncommon words or names. | |||

| Russian phonology and syntax (especially in northern dialects) have also been influenced to some extent by the numerous Finnic languages of the ]: ], ], ], the language of the ], ] etc. These languages, some of them now extinct, used to be spoken right in the center and in the north of what is now the European part of Russia. They came in contact with Eastern Slavic as far back as the early Middle Ages and eventually served as substratum for the modern Russian language. The Russian dialects spoken north, north-east and north-west of Moscow have a considerable number of words of Finno-Ugric origin. <ref>{{cite web|title=Academic credit|publisher=Вопросы языкознания. - М., 1982, № 5. - С. 18-28|url=http://www.philology.ru/linguistics2/filin-82.htm|accessdate= 2006-04-29}}</ref> <ref>{{cite web|title=Academic credit|publisher=Прибалтийско-финский компонент в русском слове |url=http://www.ksu.ru/f10/publications/konf/articles_1_1.php?id=5&num=17000000|accessdate= 2006-04-29}}</ref> | |||

| == Classification == | |||

| Outside the Slavic languages, the vocabulary and literary style of Russian have been greatly influenced by ], ], ], ], and ]. Modern Russian also has a considerable number of words adopted from ] and some other Turkic languages. | |||

| Russian is an ] of the wider ]. It is a descendant of ], a language used in ], which was a loose conglomerate of ] tribes from the late 9th to the mid-13th centuries. From the point of view of ], its closest relatives are ], ], and ],<ref>{{cite web |title=Most similar languages to Russian |url=http://www.ezglot.com/most-similar-languages.php?l=rus |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525141518/http://www.ezglot.com/most-similar-languages.php?l=rus |archive-date=25 May 2017}}</ref> the other three languages in the East Slavic branch. In many places in eastern and southern Ukraine and throughout Belarus, these languages are spoken interchangeably, and in certain areas traditional bilingualism resulted in language mixtures such as ] in eastern Ukraine and ] in Belarus. An East Slavic ], although it vanished during the 15th or 16th century, is sometimes considered to have played a significant role in the formation of modern Russian. Also, Russian has notable lexical similarities with ] due to a common ] influence on both languages, but because of later interaction in the 19th and 20th centuries, Bulgarian grammar differs markedly from Russian.{{sfn|Sussex|Cubberley|2006|pp=477–478, 480}} | |||

| Over the course of centuries, the vocabulary and literary style of Russian have also been influenced by Western and Central European languages such as Greek, ], ], ], German, French, Italian, and English,<ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Russian Language |first=Ellis Hovell |last=Minns |author-link=Ellis Minns|volume=23 |pages=912–914}}</ref> and to a lesser extent the languages to the south and the east: ], ],<ref>{{cite journal |title=The Turkic Languages of Central Asia: Problems of Planned Culture Contact by Stefan Wurm |journal=Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=392–394 |jstor=610442 |last=Waterson |first=Natalie |year=1955 |doi=10.1017/S0041977X00111954|issn=0041-977X}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://roa.rutgers.edu/files/491-0102/491-0102-GOUSKOVA-0-0.PDF |title=Falling Sonoroty Onsets, Loanwords, and Syllable contact |access-date=4 May 2015 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150505092913/http://roa.rutgers.edu/files/491-0102/491-0102-GOUSKOVA-0-0.PDF |archive-date=5 May 2015}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web |author1=Aliyeh Kord Zafaranlu Kambuziya |author2=Eftekhar Sadat Hashemi |url=http://roa.rutgers.edu/content/article/files/1317_hashemi_1.pdf|title=Russian Loanword Adoptation in Persian; Optimal Approach |website=roa.rutgers.edu |year=2010 |access-date=4 May 2015 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150505092721/http://roa.rutgers.edu/content/article/files/1317_hashemi_1.pdf |archive-date=5 May 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Iraj Bashiri |url=https://www.academia.edu/10442551|title=Russian Loanwords in Persian and Tajiki Language |website=academia.edu |year=1990|access-date=4 May 2015|url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160530193133/http://www.academia.edu/10442551/Russian_Loanwords_in_Persian_and_Tajiki_Languages |archive-date=30 May 2016}}</ref> ], and ].<ref>Colin Baker, Sylvia Prys Jones {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180320151848/https://books.google.com/books?id=YgtSqB9oqDIC&pg=PA219&dq=russian+loanwords+in+hebrew&hl=nl&sa=X&ei=Y75GVbmtKomuUe25gbAJ&ved=0CEEQ6AEwAw |date=20 March 2018}} pp 219 Multilingual Matters, 1998 {{ISBN|1-85359-362-1}}</ref> | |||

| According to the ] in ], Russian is classified as a level III language in terms of learning difficulty for native English speakers,<ref>{{cite web|title=Academic credit|publisher=Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center|url=http://www.dliflc.edu/academics/academic_affairs/dli_catalog/acadcred.htm|accessdate= 2006-04-20}}</ref> requiring approximately 780 hours of immersion instruction to achieve intermediate fluency. It is also regarded by the ] as a "hard target" language, due to both its difficulty to master for English speakers as well as due to its critical role in American foreign policy. | |||

| According to the ] in ], Russian is classified as a ] in terms of learning difficulty for native English speakers, requiring approximately 1,100 hours of immersion instruction to achieve intermediate fluency.<ref>{{cite web|last=Thompson|first=Irene|title=Language Learning Difficulty|url=http://aboutworldlanguages.com/language-difficulty|url-status=live|archive-url=http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/20140527094808/http://aboutworldlanguages.com/language-difficulty|archive-date=27 May 2014|access-date=25 May 2014|website=mustgo}}</ref> | |||

| ==Geographic distribution== | |||

| Russian is primarily spoken in ] and, to a lesser extent, the other countries that were once constituent republics of the ]. Until 1917, it was the sole official language of the ]. During the Soviet period, the policy toward the languages of the various other ethnic groups fluctuated in practice. Though each of the constituent republics had its own official language, the unifying role and superior status was reserved for Russian. Following the break-up of 1991, several of the newly independent states have encouraged their native languages, which has partly reversed the privileged status of Russian, though its role as the language of post-Soviet national intercourse throughout the region has continued. | |||

| == Standard Russian == | |||

| In ], notably, its official recognition and legality in the classroom have been a topic of considerable debate in a country where more than one-third of the population is Russian-speaking, consisting mostly of post-] immigrants from Russia and other parts of the former ] (Belarus, Ukraine). Similarly, in ], the Soviet-era immigrants and their Russian-speaking descendants constitute about one quarter of the country's current population. | |||

| {{Main|Moscow dialect}} | |||

| Feudal divisions and conflicts created obstacles between the Russian principalities before and especially during Mongol rule. This strengthened dialectal differences, and for a while, prevented the emergence of a standardized national language. The formation of the unified and centralized Russian state in the 15th and 16th centuries, and the gradual re-emergence of a common political, economic, and cultural space created the need for a common standard language. The initial impulse for standardization came from the government bureaucracy for the lack of a reliable tool of communication in administrative, legal, and judicial affairs became an obvious practical problem. The earliest attempts at standardizing Russian were made based on the so-called Moscow official or chancery language, during the 15th to 17th centuries.<ref name=":0"/> Since then, the trend of language policy in Russia has been standardization in both the restricted sense of reducing dialectical barriers between ethnic Russians, and the broader sense of expanding the use of Russian alongside or in favour of other languages.<ref name=":0">{{Citation|last=Kadochnikov|first=Denis V.|title=Languages, Regional Conflicts and Economic Development: Russia|date=2016|url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-137-32505-1_20|work=The Palgrave Handbook of Economics and Language|pages=538–580|editor-last=Ginsburgh|editor-first=Victor|place=London|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK|language=en|doi=10.1007/978-1-137-32505-1_20|isbn=978-1-349-67307-0|access-date=16 February 2021|editor2-last=Weber|editor2-first=Shlomo|archive-date=22 January 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240122222530/https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-137-32505-1_20|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The current standard form of Russian is generally regarded as the ''modern Russian literary language'' ({{lang|ru|современный русский литературный язык}} – "sovremenny russky literaturny yazyk"). It arose at the beginning of the 18th century with the modernization reforms of the Russian state under the rule of ] and developed from the Moscow (]) dialect substratum under the influence of some of the previous century's Russian chancery language.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| A much smaller Russian-speaking minority in ] has largely been assimilated during the decade of independence and currently represent less than 1/10 of the country's overall population. Nevertheless, around 80% of the population of the Baltic states are able to hold a conversation in Russian and almost all have at least some familiarity with the most basic spoken and written phrases. In ], once part of the Russian Empire, only a few Russian-speaking communities still exist. | |||

| Prior to the ], the spoken form of the Russian language was that of the nobility and the urban bourgeoisie. Russian peasants, the great majority of the population, continued to speak in their own dialects. However, the peasants' speech was never systematically studied, as it was generally regarded by philologists as simply a source of folklore and an object of curiosity.<ref>Nakhimovsky,{{nbs}}A.{{nbs}}D.{{nbs}}(2019).{{nbs}}''The Language of Russian Peasants in the Twentieth Century: A Linguistic Analysis and Oral History''.{{nbs}}United Kingdom:{{nbs}}Lexington Books. (Chapter 1)</ref> This was acknowledged by the noted Russian dialectologist ], who toward the end of his life wrote: "Scholars of Russian dialects mostly studied phonetics and morphology. Some scholars and collectors compiled local dictionaries. We have almost no studies of lexical material or the syntax of Russian dialects."<ref>Nakhimovsky,{{nbs}}A.{{nbs}}D.{{nbs}}(2019).{{nbs}}''The Language of Russian Peasants in the Twentieth Century: A Linguistic Analysis and Oral History''.{{nbs}}United Kingdom:{{nbs}}Lexington Books. (p.2)</ref> | |||

| In the twentieth century it was widely taught in the schools of the members of the old ] and in other ] that used to be satellites of the USSR. In particular, these countries include ], ], the ], ], ], ], and ]. However, younger generations are usually not fluent in it, because Russian is no longer mandatory in the school system. It was, and to a lesser extent still is, widely taught in Asian countries such as ], ], and ] due to Soviet influence. Russian is still used as a ] in ] by a few tribes. It was also taught as the mandatory foreign language requisite in the ] before the ]. | |||

| After 1917, Marxist linguists had no interest in the multiplicity of peasant dialects and regarded their language as a relic of the rapidly disappearing past that was not worthy of scholarly attention. Nakhimovsky quotes the Soviet academicians A.M Ivanov and L.P Yakubinsky, writing in 1930: | |||

| Russian is also spoken in ] by at least 750,000 ethnic ] immigrants from the former ] (1999 census). The Israeli ] and ]s regularly publish material in Russian. | |||

| <blockquote>The language of peasants has a motley diversity inherited from feudalism. On its way to becoming proletariat peasantry brings to the factory and the industrial plant their local peasant dialects with their phonetics, grammar, and vocabulary, and the very process of recruiting workers from peasants and the mobility of the worker population generate another process: the liquidation of peasant inheritance by way of leveling the particulars of local dialects. On the ruins of peasant multilingual, in the context of developing heavy industry, a qualitatively new entity can be said to emerge—the general language of the working class... capitalism has the tendency of creating the general urban language of a given society.<ref>''Ibid.''(p.3)</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Sizeable Russian-speaking communities also exist in ], especially in large urban centers of the ] and ] such as ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and the ] suburb of ]. In the former two Russian-speaking groups total over half a million. In a number of locations they issue their own newspapers, and live in their self-sufficient neighborhoods (especially the generation of immigrants who started arriving in the early sixties). It is important to note, however, that only about a quarter of them are ethnic Russians. Before the ], the overwhelming majority of ]s in North America were Russian-speaking ]. Afterwards the influx from the countries of the former ] changed the statistics somewhat. According to the ], Russian was reported as language spoken at home by 1.50% of population, or about 4.2 million, placing it as #10 language in the ]. | |||

| == Geographic distribution == | |||

| Significant Russian-speaking groups also exist in ]. These have been fed by several waves of immigrants since the beginning of the twentieth century, each with its own flavour of language. ], the ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] have significant Russian-speaking communities totaling 3 million people. | |||

| {{Main|Geographical distribution of Russian speakers}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Two thirds of them are actually Russian-speaking descendants of ], ], ], ], or ] who either repatriated after the ] collapsed or are just looking for temporary employment. But many are well-off Russian families acquiring property and getting an education. | |||

| In 2010, there were 259.8 million speakers of Russian in the world: in Russia – 137.5 million, in the ] and Baltic countries – 93.7 million, in Eastern Europe – 12.9 million, Western Europe – 7.3 million, Asia – 2.7 million, in the Middle East and North Africa – 1.3 million, Sub-Saharan Africa – 0.1 million, Latin America – 0.2 million, U.S., ], Australia, and ] – 4.1 million speakers. Therefore, the Russian language is the ], after English, Mandarin, ]-Urdu, Spanish, French, Arabic, and Portuguese.<ref name="demoscope.ru">{{cite web|title=Демографические изменения – не на пользу русскому языку|url=http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2013/0571/tema02.php|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140805090035/http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2013/0571/tema02.php|archive-date=5 August 2014|access-date=23 April 2014|publisher=Demoscope.ru|language=ru}}</ref><ref name="Ethnologue-rating-2018">{{cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/statistics/size|title=Statistical Summaries. Summary by language size. Language size|date=21 February 2018|editor=Lewis, M. Paul|editor2=Gary F. Simons|editor3=Charles D. Fennig|work=]|edition=21st|location=Dallas|publisher=]|language=en|access-date=6 January 2019|archive-date=26 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181226040016/https://www.ethnologue.com/statistics/size|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Арефьев А. Л. Сжимающееся русскоязычие">{{cite web|author=Арефьев А. Л.|date=31 October 2013|title=Сжимающееся русскоязычие. Демографические изменения — не на пользу русскому языку|url=http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2013/0571/tema02.php|work=]|language=ru|number=571–572|access-date=23 January 2014|archive-date=5 August 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140805090035/http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2013/0571/tema02.php|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Earlier, the descendants of the Russian émigrés tended to lose the tongue of their ancestors by the third generation. Now, when the border is more open, Russian is likely to survive longer, especially when many of the emigrants visit their homelands at least once a year and also have access to Russian websites and TV channels. | |||

| Russian is one of the ] of the United Nations. Education in Russian is still a popular choice for both Russian as a second language (RSL) and native speakers in Russia, and in many former Soviet republics. Russian is still seen as an important language for children to learn in most of the former Soviet republics.<ref name=gallup2008>{{Cite web|url=http://www.gallup.com/poll/112270/Russias-Language-Could-Ticket-Migrants.aspx |title=Russia's Language Could Be Ticket in for Migrants |date=28 November 2008 |publisher=] |access-date=26 May 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140928191526/http://www.gallup.com/poll/112270/russias-language-could-ticket-migrants.aspx |archive-date=28 September 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Recent estimates of the total number of speakers of Russian: | |||

| === Europe === | |||

| {| align=center cellpadding=4 cellspacing=0 border=0 | |||

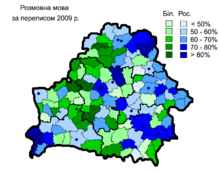

| ] (according to the ]) (green — Belarusian, blue — Russian) (])]] | |||

| |- | |||

| ] (according to the 2000 Estonian census)]] | |||

| !Source||Native speakers||Native Rank||Total speakers||Total rank | |||

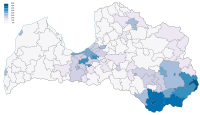

| ] (according to the {{Interlanguage link|2011 Latvian census|lt=2011 census|lv|2011. gada tautas skaitīšana Latvijā}})]] | |||

| |- | |||

| ] with Russian as their native language (according to the ])]] | |||

| |G. Weber, "Top Languages",<br>''Language Monthly'',<br>3: 12-18, 1997, ISSN 1369-9733||160,000,000||8||285,000,000||5 | |||

| In ], Russian is a second state language alongside Belarusian per the ].<ref name="fundeh1"/> 77% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 67% used it as the main language with family, friends, or at work.<ref name="demoscope329">{{cite web|title=Русскоязычие распространено не только там, где живут русские|url=http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2008/0329/tema03.php|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161023011719/http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2008/0329/tema03.php|archive-date=23 October 2016|website=demoscope.ru|language=ru}}</ref> According to the ], out of 9,413,446 inhabitants of the country, 5,094,928 (54.1% of the total population) named Belarusian as their native language, with 61.2% of ethnic Belarusians and 54.5% of ] declaring Belarusian as their native language. In everyday life in the Belarusian society the Russian language prevails, so according to the 2019 census 6,718,557 people (71.4% of the total population) stated that they speak Russian at home, for ethnic Belarusians this share is 61.4%, for ] — 97.2%, for ] — 89.0%, for Poles — 52.4%, and for ] — 96.6%; 2,447,764 people (26.0% of the total population) stated that the language they usually speak at home is Belarusian, among ethnic Belarusians this share is 28.5%; the highest share of those who speak Belarusian at home is among ethnic Poles — 46.0%.<ref>{{cite web |title = Общая численность населения, численность населения по возрасту и полу, состоянию в браке, уровню образования, национальностям, языку, источникам средств к существованию по Республике Беларусь |url = https://belstat.gov.by/upload/iblock/471/471b4693ab545e3c40d206338ff4ec9e.pdf |archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20201004235333/https://www.belstat.gov.by/upload/iblock/471/471b4693ab545e3c40d206338ff4ec9e.pdf |archivedate = 4 October 2020 |url-status= live |access-date = 6 October 2020 }}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |World Almanac (1999)||145,000,000||8 (2005)||275,000,000||5 | |||

| |- | |||

| |SIL (2000 WCD)||145,000,000||8||255,000,000||5-6 (tied with Arabic) | |||

| |- | |||

| |CIA World Factbook (2005)||160,000,000||8|| | |||

| |} | |||

| In ], Russian is spoken by 29.6% of the population, according to a 2011 estimate from the World Factbook,<ref name=bookoffact/> and is officially considered a foreign language.<ref name="fundeh1"/> School education in the Russian language is a very contentious point in Estonian politics, and in 2022, the parliament approved a bill to close up all Russian language schools and kindergartens by the school year. The transition to only Estonian language schools and kindergartens will start in the 2024–2025 school year.<ref>{{Cite web|website=]|date=12 December 2022|title=Riigikogu kiitis heaks eestikeelsele õppele ülemineku|trans-title=The Riigikogu approved the transition to Estonian-language education|url=https://www.err.ee/1608817708/riigikogu-kiitis-heaks-eestikeelsele-oppele-ulemineku|language=Estonian|access-date=2 February 2023|archive-date=2 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230202094203/https://www.err.ee/1608817708/riigikogu-kiitis-heaks-eestikeelsele-oppele-ulemineku|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=13 December 2022|title=Estonia's Russian schools to switch to Estonian-language schooling|website=]|url=https://estonianworld.com/knowledge/estonias-russian-schools-to-switch-to-estonian-language-schooling/ |access-date=2 June 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ===Official status=== | |||

| Russian is the official language of ], and an official language of ], ], ], the ] and the ] ], ] and ]. It is one of the six official languages of the ]. Education in Russian is still a popular choice for many of the both native and RSL (Russian as a second language) speakers in Russia and many of the former Soviet republics. | |||

| In ], Russian is officially considered a foreign language.<ref name="fundeh1"/> 55% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 26% used it as the main language with family, friends, or at work.<ref name="demoscope329"/> On 18 February 2012, Latvia held a ] on whether to adopt Russian as a second official language.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.cvk.lv/pub/public/28361.html/|title=Referendum on the Draft Law 'Amendments to the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia'|publisher=Central Election Commission of Latvia|year=2012|access-date=2 May 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120502013728/http://web.cvk.lv/pub/public/28361.html|archive-date=2 May 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> According to the Central Election Commission, 74.8% voted against, 24.9% voted for and the voter turnout was 71.1%.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tn2012.cvk.lv/|title=Results of the referendum on the Draft Law 'Amendments to the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia'|language=lv|publisher=Central Election Commission of Latvia|year=2012|access-date=2 May 2012|archive-date=15 April 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120415075014/http://www.tn2012.cvk.lv/|url-status=live}}</ref> Starting in 2019, ] will be gradually discontinued in private colleges and universities in Latvia, and in general instruction in Latvian public high schools.<ref>{{cite news |title=Latvia pushes majority language in schools, leaving parents miffed |url=https://www.dw.com/en/latvia-pushes-majority-language-in-schools-leaving-parents-miffed/a-45385830 |agency=Deutsche Welle |date=8 September 2018 |access-date=7 August 2019 |archive-date=23 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190123223709/https://www.dw.com/en/latvia-pushes-majority-language-in-schools-leaving-parents-miffed/a-45385830 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Moscow threatens sanctions against Latvia over removal of Russian from secondary schools |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/04/03/moscow-threatens-sanctions-against-latvia-removal-russian-secondary/ |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/04/03/moscow-threatens-sanctions-against-latvia-removal-russian-secondary/ |archive-date=10 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |work=The Daily Telegraph |date=3 April 2018}}{{cbignore}}</ref> On 29 September 2022, ] passed in the final reading amendments that state that all schools and kindergartens in the country are to transition to education in ]. From 2025, all children will be taught in Latvian only.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://bnn-news.com/latvia-to-gradually-transition-to-education-only-in-official-language-238962|title=Latvia to gradually transition to education only in official language|date=29 September 2022|access-date=21 November 2023|archive-date=5 December 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231205153814/https://bnn-news.com/latvia-to-gradually-transition-to-education-only-in-official-language-238962|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Sheremet |first=Anhelina |date=13 May 2022 |title=In Latvia, from 2025, all children will be taught in Latvian only |url=https://babel.ua/en/news/78675-in-latvia-from-2025-all-children-will-be-taught-in-latvian-only |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231121114406/https://babel.ua/en/news/78675-in-latvia-from-2025-all-children-will-be-taught-in-latvian-only |archive-date=21 November 2023 |website=Бабель}}</ref> On 28 September 2023, Latvian deputies approved The National Security Concept, according to which from 1 January 2026, all content created by Latvian public media (including ]) should be only in Latvian or a language that "belongs to the European cultural space". The financing of Russian-language content by the state will cease, which the concept says create a "unified information space". However, one inevitable consequence would be the closure of public media broadcasts in Russian on LTV and Latvian Radio, as well as the closure of LSM's Russian-language service.<ref>{{Cite web |date=28 September 2023 |title=Saeima approves updated National Security concept for Latvia |url=https://eng.lsm.lv/article/society/defense/28.09.2023-saeima-approves-updated-national-security-concept-for-latvia.a525735/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231121114206/https://eng.lsm.lv/article/society/defense/28.09.2023-saeima-approves-updated-national-security-concept-for-latvia.a525735/ |archive-date=21 November 2023 |website=Eng.LSM.lv}}</ref> | |||

| 97% of the public school students of Russia, 75% in Belarus, 41% in Kazakhstan, 25% in ], 23% in Kyrgyzstan, 21% in ], 7% in ], 5% in ] and 2% in ] and ] receive their education only or mostly in Russian, although the corresponding percentage of ethnic Russians was 78% in ], 10% in ], 26% in ], 17% in ], 9% in ], 6% in ], 2% in ], 1.5% in ] and less than 1% in both ] and ]. | |||

| In ], Russian has no official or legal status, but the use of the language has some presence in certain areas. A large part of the population, especially the older generations, can speak Russian as a foreign language.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://in.mfa.lt/in/en/news/statistics-lithuania-785-of-lithuanians-speak-at-least-one-foreign-language|title=Statistics Lithuania: 78.5% of Lithuanians speak at least one foreign language | News |website= Ministry of Foreign Affairs |date=27 September 2013 |access-date=28 December 2020|archive-date=6 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210106145651/https://in.mfa.lt/in/en/news/statistics-lithuania-785-of-lithuanians-speak-at-least-one-foreign-language|url-status=dead}}</ref> However, English has replaced Russian as '']'' in Lithuania and around 80% of young people speak English as their first foreign language.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://investlithuania.com/news/employees-fluent-in-three-languages-its-the-norm-in-lithuania/|title=Employees fluent in three languages – it's the norm in Lithuania |publisher=Outsourcing&More |date=26 September 2018 |first1=Rūta |last1=Labalaukytė |website=Invest Lithuania |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231019201722/https://investlithuania.com/news/employees-fluent-in-three-languages-its-the-norm-in-lithuania/ |archive-date= 19 October 2023 }}</ref> In contrast to the other two Baltic states, Lithuania has a relatively small Russian-speaking minority (5.0% as of 2008).<ref name="andrlik">{{cite web|title=Ethnic and Language Policy of the Republic of Lithuania: Basis and Practice |first1=Jan |last1=Andrlík|url=http://alppi.eu/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/Andrlik_2009.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160403213425/http://alppi.eu/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/Andrlik_2009.pdf|archive-date=3 April 2016}}</ref> According to the ], Russian was the native language for 7.2% of the population.<ref>Statistics Lithuania census 2011: {{cite web |url=https://osp.stat.gov.lt/documents/10180/217110/Gyv_kalba_tikyba.pdf |title=Gyventojai pagal tautybę, gimtąją kalbą ir tikybą |website=Oficialiosios statistikos portalas |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230404074611/https://osp.stat.gov.lt/documents/10180/217110/Gyv_kalba_tikyba.pdf |archive-date= 4 April 2023 }}</ref> | |||

| Russian-language schooling is also available in Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, despite the government attempts to reduce the number of subjects taught in Russian. | |||

| In ], Russian was considered to be the language of interethnic communication under a Soviet-era law.<ref name="fundeh1"/> On 21 January 2021, the ] declared the law unconstitutional and deprived Russian of the status of the language of interethnic communication.<ref>{{Cite web |date=1 January 2021 |title=The Court examined the constitutionality of the Law on the Usage of Languages Spoken on the Territory of the Republic of Moldova |url=https://www.constcourt.md/libview.php?l=en&idc=7&id=2067&t=/Media/News/The-Court-examined-the-constitutionality-of-the-Law-on-the-Usage-of-Languages-Spoken-on-the-Territory-of-the-Republic-of-Moldova |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211022191049/https://www.constcourt.md/libview.php?l=en&idc=7&id=2067&t=/Media/News/The-Court-examined-the-constitutionality-of-the-Law-on-the-Usage-of-Languages-Spoken-on-the-Territory-of-the-Republic-of-Moldova |archive-date=22 October 2021 |website=Constitutional Court of the Republic of Moldova}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Tanas |first=Alexander |date=21 January 2021 |title=Moldovan court overturns special status for Russian language |language=en-US |work=Reuters |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-moldova-language-idUSKBN29Q2J0/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231121095432/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-moldova-language-idUSKBN29Q2J0/ |archive-date= 21 November 2023 }}</ref> 50% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 19% used it as the main language with family, friends, or at work.<ref name="demoscope329"/> According to the ], Russians accounted for 4.1% of Moldova's population, 9.4% of the population declared Russian as their native language, and 14.5% said they usually spoke Russian.<ref>{{Cite web |date=31 March 2017 |title=The Population of the Republic of Moldova at the time of the Census was 2 998 235 |url=https://statistica.gov.md/en/the-population-of-the-republic-of-moldova-at-the-time-12_896.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231121100936/https://statistica.gov.md/en/the-population-of-the-republic-of-moldova-at-the-time-12_896.html |archive-date=21 November 2023 |website=National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova}}</ref> | |||

| Russian has co-official status alongside ] in seven Romanian ] in ] and ] counties. In these localities, Russian-speaking ], who are a recognized ethnic minority, make up more than 20% of the population. Thus, according to Romania's minority rights law, education, signage and access to public administration and the justice system are provided in Russian, alongside Romanian. | |||

| According to the ], Russian language skills were indicated by 138 million people (99.4% of the respondents), while according to the ] – 142.6 million people (99.2% of the respondents).<ref>{{cite web|date=8 November 2011|title=Демоскоп Weekly. Об итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года. Сообщение Росстата|url=http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2011/0491/perep01.php|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141018055149/http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2011/0491/perep01.php|archive-date=18 October 2014|access-date=23 April 2014|publisher=Demoscope.ru|language=ru}}</ref> | |||

| ===Dialects=== | |||

| Despite levelling after 1900, especially in matters of vocabulary, a number of dialects exist in Russia. Some linguists divide the dialects of the Russian language into two primary regional groupings, "Northern" and "Southern", with ] lying on the zone of transition between the two. Others divide the language into three groupings, Northern, Central and Southern, with Moscow lying in the Central region. ] within Russia recognizes dozens of smaller-scale variants. | |||

| In ], Russian is a significant minority language. According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 14,400,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 29 million active speakers.<ref name="demoscope251">{{cite web|title=Падение статуса русского языка на постсоветском пространстве|url=http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2006/0251/tema01.php|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161025204352/http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2006/0251/tema01.php|archive-date=25 October 2016|website=demoscope.ru|language=ru}}</ref> 65% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 38% used it as the main language with family, friends, or at work.<ref name="demoscope329"/> On 5 September 2017, Ukraine's Parliament passed a ] which requires all schools to teach at least partially in Ukrainian, with provisions while allow indigenous languages and languages of national minorities to be used alongside the national language.<ref>{{cite web |title=New education law becomes effective in Ukraine |url=https://www.unian.info/society/2159231-new-education-law-becomes-effective-in-ukraine.html |website=www.unian.info |access-date=22 March 2023 |language=en |archive-date=27 June 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180627202400/https://www.unian.info/society/2159231-new-education-law-becomes-effective-in-ukraine.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The law faced criticism from officials in Russia and Hungary.<ref>{{cite news |title=Ukraine defends education reform as Hungary promises 'pain' |url=https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/ukraine-defends-education-reform-as-hungary-promises-pain-1.3235916 |newspaper=The Irish Times |date=27 September 2017 |access-date=7 August 2019 |archive-date=24 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220324150210/https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/ukraine-defends-education-reform-as-hungary-promises-pain-1.3235916 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Ukrainian Language Bill Facing Barrage Of Criticism From Minorities, Foreign Capitals |url=https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-language-legislation-minority-languages-russia-hungary-romania/28753925.html |work=] |date=24 September 2017 |access-date=7 August 2019 |archive-date=31 March 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190331162824/https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-language-legislation-minority-languages-russia-hungary-romania/28753925.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The 2019 ] gives priority to the ] in more than 30 spheres of public life: in particular in ], media, education, science, culture, advertising, ]. The law does not regulate private communication.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2704-19#Text|title=Про забезпечення функціонування української мови як державної|website=Офіційний вебпортал парламенту України|access-date=21 November 2023|archive-date=2 May 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200502182619/https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2704-19#Text|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=16 May 2019|title=Кому варто боятися закону про мову?|url=http://language-policy.info/2019/05/komu-varto-boyatysya-zakonu-pro-movu/|access-date=14 May 2022|website=Портал мовної політики|language=uk|archive-date=18 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190518152707/http://language-policy.info/2019/05/komu-varto-boyatysya-zakonu-pro-movu/|url-status=live}}</ref> A poll conducted in March 2022 by ] in the territory controlled by Ukraine found that 83% of the respondents believe that Ukrainian should be the only state language of Ukraine. This opinion dominates in all macro-regions, age and language groups. On the other hand, before the war, almost a quarter of Ukrainians were in favour of granting Russian the status of the state language, while after the beginning of Russia's invasion the support for the idea dropped to just 7%. In peacetime, the idea of raising the status of Russian was traditionally supported by residents of the ] and ]. But even in these regions, only a third of the respondents were in favour, and after ], their number dropped by almost half.<ref>{{cite web |title=Шосте загальнонаціональне опитування: мовне питання в Україні (19 березня 2022) |url=https://ratinggroup.ua/research/ukraine/language_issue_in_ukraine_march_19th_2022.html |access-date=27 August 2023 |language=uk |archive-date=24 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230824150442/https://ratinggroup.ua/research/ukraine/language_issue_in_ukraine_march_19th_2022.html |url-status=live }}</ref> According to the survey carried out by ] in August 2023 in the territory controlled by Ukraine and among the refugees, almost 60% of the polled usually speak Ukrainian at home, about 30% – Ukrainian and Russian, only 9% – Russian. Since March 2022, the use of Russian in everyday life has been noticeably decreasing. For 82% of respondents, Ukrainian is their mother tongue, and for 16%, Russian is their mother tongue. ] and ] are more likely to use both languages for communication or speak Russian. Nevertheless, more than 70% of IDPs and refugees consider Ukrainian to be their native language.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rating_independence_august_2023.pdf |title=Соціологічне дослідження до Дня Незалежності УЯВЛЕННЯ ПРО ПАТРІОТИЗМ ТА МАЙБУТНЄ УКРАЇНИ |access-date=21 November 2023 |archive-date=27 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231227002638/https://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rating_independence_august_2023.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The dialects often show distinct and non-standard features of pronunciation and intonation, vocabulary, and grammar. Some of these are relics of ancient usage now completely discarded by the standard language. Also cf. Moscow pronunciation of "-чн-", e.g. "булошная" (''buloshnaya'' - bakery) instead of "булочная" (''bulochnaya''). | |||

| In the 20th century, Russian was a mandatory language taught in the schools of the members of the old ] and in other ] that used to be satellites of the USSR. According to the Eurobarometer 2005 survey,<ref>{{cite web|year=2006|title=Europeans and their Languages|url=http://ec.europa.eu/education/languages/pdf/doc631_en.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090521033643/http://ec.europa.eu/education/languages/pdf/doc631_en.pdf|archive-date=21 May 2009|website=europa.eu}}</ref> fluency in Russian remains fairly high (20–40%) in some countries, in particular former Warsaw Pact countries. | |||

| The northern dialects and those spoken along the ] typically pronounce unstressed {{IPA|/o/}} clearly (the phenomenon called okanye ''оканье''); east of Moscow, particularly in ], unstressed {{IPA|/e/}} and {{IPA|/a/}} following ]d consonants and preceding a stressed syllabus are not reduced to {{IPA|}} (unlike in the Moscow dialect) and are instead pronounced as {{IPA|/a/}} in such positions (e.g. несл'''и''' is pronounced as {{IPA|}}, not as {{IPA|}}) - this is called yakanye ''яканье''<ref>{{cite web|title=The Language of the Russian Village|language=Russian|url=http://www.gramota.ru/book/village/map13.html|accessdate= 2006-07-04}}</ref>; many southern dialects palatalize the final {{IPA|/t/}} in 3rd person forms of verbs and ]ize the {{IPA|/g/}} into {{IPA|}}. However, in certain areas south of Moscow, e.g. in and around ], {{IPA|/g/}} is pronounced as in the Moscow and northern dialects unless it precedes a voiceless plosive or a silent pause. In this position {{IPA|/g/}} is spirantized and devoiced to the fricative {{IPA|}}, e.g. друг {{IPA|}} (in Moscow's dialect, only Бог {{IPA|}}, лёгкий {{IPA|}}, мягкий {{IPA|}} and some derivatives follow this rule). It should be noted that some of these features (e.g. the spirantized {{IPA|/ɡ/}} and palatalized final {{IPA|/t/}} in 3rd person forms of verbs) are also present in modern ], indicating either a linguistic continuum or strong influence one way or the other. | |||

| === Caucasus === | |||

| The town of ] has historically displayed a feature called chokanye/tsokanye (чоканье/цоканье), where {{IPA|/ʨ/}} and {{IPA|/ʦ/}} were confused (this is thought to be due to influence from ], which doesn't distinguish these sounds). So, '''ц'''апля ("heron") has been recorded as 'чапля'. Also, the second palatalization of ]s did not occur there, so the so-called '''ě²''' (from the Proto-Slavonic diphthong *ai) did not cause {{IPA|/k, g, x/}} to shift to {{IPA|/ʦ, ʣ, s/}}; therefore where Standard Russian has '''ц'''епь ("chain"), the form '''к'''епь {{IPA|kepʲ}} is attested in earlier texts. | |||

| In ], Russian has no official status, but it is recognized as a minority language under the ].<ref name="fundeh1"/> 30% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 2% used it as the main language with family, friends, or at work.<ref name="demoscope329"/> | |||

| In ], Russian has no official status, but is a ''lingua franca'' of the country.<ref name="fundeh1">{{cite web |url=http://www.fundeh.org/files/publications/90/vedenie_obshchee_sostoyanie_russkogo_yazyka.pdf |title=Введение |access-date=16 October 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304122143/http://www.fundeh.org/files/publications/90/vedenie_obshchee_sostoyanie_russkogo_yazyka.pdf |archive-date=4 March 2016}}</ref> 26% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 5% used it as the main language with family, friends, or at work.<ref name="demoscope329"/> | |||

| Among the first to study Russian dialects was ] in the eighteenth century. In the nineteenth, ] compiled the first dictionary that included dialectal vocabulary. Detailed mapping of Russian dialects began at the turn of the twentieth century. In modern times, the monumental ''Dialectological Atlas of the Russian Language'' (''Диалектологический атлас русского языка'' {{IPA|/dʲəʌˈlʲektəlʌˈɡʲiʨəskʲəj ˈatləs ˈruskəvə jəzɨˈka/}}), was published in 3 folio volumes 1986-1989, after four decades of preparatory work. | |||

| In ], Russian has no official status, but it is recognized as a minority language under the ].<ref name="fundeh1"/> Russian is the language of 9% of the population according to the World Factbook.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204222544/https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/georgia/ |date=4 February 2021 }}. '']''. ].</ref> Ethnologue cites Russian as the country's de facto working language.<ref name="ethn">{{Ethnologue21|rus|Russian}}</ref> | |||

| The ''standard language'' is based on (but not identical to) the Moscow dialect. | |||

| === |

=== Asia === | ||

| In ], Russian has no official status, but it is spoken by the ] in the northeastern ] and the northwestern ]. Russian was also the main foreign language taught in school in China between 1949 and 1964. | |||

| * ], a criminal ] of ancient origin, with Russian grammar, but with distinct vocabulary. | |||

| * ] is a language with Russian and Ukrainian features, spoken in some rural areas of Ukraine | |||

| * ] is a language with Russian and Belorusian features used by a large portion of the rural population in ]. | |||

| * ], a pseudo pidgin of German and Russian. | |||

| * ] is an extinct ] language with mostly Russian vocabulary and mostly ] grammar, used for communication between ] and ] in ] and ]. | |||

| * ], Russian-English pidgin. This word is also used by English speakers to describe the way in which Russians attempt to speak English using Russian morphology and/or syntax. | |||

| In ], Russian is not a state language, but according to article 7 of the ] its usage enjoys equal status to that of the ] in state and local administration.<ref name="fundeh1"/> The 2009 census reported that 10,309,500 people, or 84.8% of the population aged 15 and above, could read and write well in Russian, and understand the spoken language.<ref name=kazcensus>{{cite web |title=Results of the 2009 National Population Census of the Republic of Kazakhstan |url=http://liportal.giz.de/fileadmin/user_upload/oeffentlich/Kasachstan/40_gesellschaft/Kaz2009_Analytical_report.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210615010100/https://liportal.giz.de/fileadmin/user_upload/oeffentlich/Kasachstan/40_gesellschaft/Kaz2009_Analytical_report.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=15 June 2021 |publisher=Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit |access-date=31 October 2015 }}</ref> In October 2023, Kazakhstan drafted a media law aimed at increasing the use of the Kazakh language over Russian, the law stipulates that the share of the state language on television and radio should increase from 50% to 70%, at a rate of 5% per year, starting in 2025.<ref>{{Cite news|title=Kazakhstan drafts media law to increase use of Kazakh language over Russian|agency=Agence France-Presse|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/06/kazakhstan-drafts-media-law-to-increase-use-of-kazakh-language-over-russian|website=The Guardian|id=0261-3077|date=6 October 2023|accessdate=28 October 2023|language=en-GB|archive-date=28 October 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231028002220/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/06/kazakhstan-drafts-media-law-to-increase-use-of-kazakh-language-over-russian|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Writing system== | |||

| ===Alphabet=== | |||

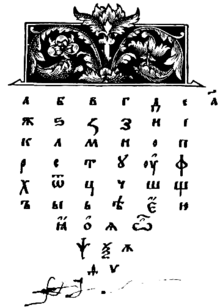

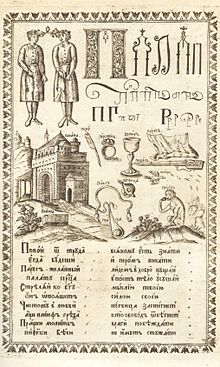

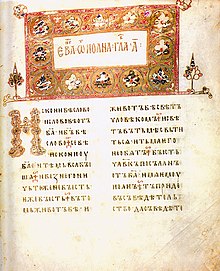

| ] presented the Cyrillic alphabet in this 1619 publication describing the "Slavonic" language.]] | |||

| {{main|Russian alphabet}} | |||

| Russian is written using a modified version of the ] alphabet, consisting of 33 letters. | |||

| In ], Russian is a co-official language per article 5 of the ].<ref name="fundeh1"/> The 2009 census states that 482,200 people speak Russian as a native language, or 8.99% of the population.<ref name=kyrcen>{{cite web|title=Population And Housing Census Of The Kyrgyz Republic Of 2009 |url=http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sources/census/2010_phc/Kyrgyzstan/A5-2PopulationAndHousingCensusOfTheKyrgyzRepublicOf2009.pdf |publisher=UN Stats |access-date=1 November 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120710092216/http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sources/census/2010_PHC/Kyrgyzstan/A5-2PopulationAndHousingCensusOfTheKyrgyzRepublicOf2009.pdf |archive-date=10 July 2012}}</ref> Additionally, 1,854,700 residents of Kyrgyzstan aged 15 and above fluently speak Russian as a second language, or 49.6% of the population in the age group.<ref name=kyrcen/> | |||

| The following table gives their upper case forms, along with ] values for each letter's typical sound: | |||

| In ], Russian is the language of inter-ethnic communication under the ] and is permitted in official documentation.<ref name="fundeh1"/> 28% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 7% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.<ref name="demoscope329"/> The World Factbook notes that Russian is widely used in government and business.<ref name="bookoffact">{{cite web |title=Languages |url=https://www.hannasles.com/languages/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220523002924/https://www.hannasles.com/russian-translation-services/ |archive-date=23 May 2022 |access-date=26 April 2015 |publisher=The World Factbook}}</ref> | |||

| {| align=center cellpadding=4 style="text-align:center;" | |||

| In ], Russian lost its status as the official ''lingua franca'' in 1996.<ref name="fundeh1"/> Among 12%<ref name=bookoffact/> of the population who grew up in the Soviet era can speak Russian, other generations of citizens that do not have any knowledge of Russian. Primary and secondary education by Russian is almost non-existent.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Bekmurzaev |first1=Nurbek |title=Russian Language Status in Central Asian Countries |date=28 February 2019 |url=https://cabar.asia/en/russian-language-status-in-central-asian-countries |publisher=Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting |access-date=22 June 2022 |archive-date=20 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220920173149/https://cabar.asia/en/russian-language-status-in-central-asian-countries |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In ], Russian is the language of inter-ethnic communication.<ref name="AA"/><ref name="Шухрат Хуррамов"/><ref name="AB"/> It has some official roles, being permitted in official documentation and is the ''lingua franca'' of the country and the language of the elite.<ref name="fundeh1"/><ref name=UZB>{{cite web |title=Law on Official Language |url=https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/eoir/legacy/2013/11/08/Law_on_official_language.pdf |publisher=Government of Uzbekistan |access-date=2 December 2016 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170129231323/https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/eoir/legacy/2013/11/08/Law_on_official_language.pdf |archive-date=29 January 2017}}</ref> Russian is spoken by 14.2% of the population according to an undated estimate from the World Factbook.<ref name=bookoffact/> | |||

| In 2005, Russian was the most widely taught foreign language in Mongolia,<ref>{{cite news |first=James |last=Brooke |newspaper=] |title=For Mongolians, E Is for English, F Is for Future |date=15 February 2005 |access-date=16 May 2009 |url=https://nytimes.com/2005/02/15/international/asia/15mongolia.html?_r=2&pagewanted=all |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110614225411/http://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/15/international/asia/15mongolia.html?_r=2&pagewanted=all |archive-date=14 June 2011}}</ref> and was compulsory in Year 7 onward as a second foreign language in 2006.<ref name="auto">{{cite news|date=21 September 2006|script-title=ru:Русский язык в Монголии стал обязательным|language=ru|trans-title=Russian language has become compulsory in Mongolia|agency=New Region|url=http://www.nr2.ru/83966.html|url-status=dead|access-date=16 May 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081009170315/http://www.nr2.ru/83966.html|archive-date=9 October 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Around 1.5{{nbs}}million Israelis spoke Russian as of 2017.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170313125416/http://www.forbes.ru/finansy-i-investicii/340519-rossiysko-izrailskie-ekonomicheskie-svyazi-ne-tolko-neft-na |date=13 March 2017}} Алексей Голубович, Forbes Russia, 9 March 2017</ref> The Israeli ] and websites regularly publish material in Russian and there are Russian newspapers, television stations, schools, and social media outlets based in the country.<ref>{{Cite web|url= https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/russians-in-israel|title= Russians in Israel|access-date= 11 July 2019|archive-date= 11 July 2019|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190711133459/https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/russians-in-israel/|url-status= live}}</ref> There is an Israeli TV channel mainly broadcasting in Russian with ]. See also ]. | |||

| Russian is also spoken as a second language by a small number of people in ].<ref>Awde and Sarwan, 2003</ref> | |||

| In ], Russian has been added in the elementary curriculum along with Chinese and Japanese and were named as "first foreign languages" for Vietnamese students to learn, on equal footing with English.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-to-add-chinese-russian-to-elementary-school-curriculum-3470743.html |title=Vietnam to add Chinese, Russian to elementary school curriculum |date=20 September 2016 |access-date=12 July 2019 |archive-date=12 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190712121639/https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-to-add-chinese-russian-to-elementary-school-curriculum-3470743.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === North America === | |||

| {{See also|Russian language in the United States}} | |||

| The Russian language was first introduced in North America when ] voyaged into ] and claimed it for Russia during the 18th century. Although most Russian colonists left after the United States bought the land in 1867, a handful stayed and preserved the Russian language in this region to this day, although only a few elderly speakers of this unique dialect are left.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://languagehat.com/ninilchik/ |title=Ninilchik |publisher=languagehat.com |date=1 January 2009 |access-date=18 June 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140107112220/http://languagehat.com/ninilchik/ |archive-date=7 January 2014}}</ref> In ], Russian is more spoken than English. Sizable Russian-speaking communities also exist in North America, especially in large urban centers of the US and Canada, such as ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. In a number of locations they issue their own newspapers, and live in ]s (especially the generation of immigrants who started arriving in the early 1960s). Only about 25% of them are ethnic Russians, however. Before the ], the overwhelming majority of ]s in ] in New York City were Russian-speaking Jews. Afterward, the influx from the countries of the former ] changed the statistics somewhat, with ethnic Russians and Ukrainians immigrating along with some more Russian Jews and Central Asians. According to the ], in 2007 Russian was the primary language spoken in the homes of over 850,000 individuals living in the United States.<ref>{{cite web|title=Language Use in the United States: 2007, census.gov|url=https://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/language/data/acs/ACS-12.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130614060228/http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/language/data/acs/ACS-12.pdf|archive-date=14 June 2013|access-date=18 June 2013}}</ref> | |||

| == As an international language == | |||

| {{See also|Russophone|List of official languages by institution|Internet in Russian}} | |||

| Russian is one of the official languages (or has similar status and interpretation must be provided into Russian) of the following: | |||

| {{div col}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||