| Revision as of 10:35, 29 August 2006 view sourceSmackBot (talk | contribs)3,734,324 editsm ISBN formatting &/or general fixes using AWB← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:08, 21 January 2025 view source BigBullfrog (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users54,211 editsNo edit summaryTag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|French folk heroine and saint (1412–1431)}} | |||

| :''This article is about the person Joan of Arc. For other uses of this name, see ].'' | |||

| {{Redirect-several|dab=off|Jeanne d'Arc (disambiguation)|Joan of Arc (disambiguation)|Jehanne (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Featured article}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=March 2013}} | |||

| {{Infobox saint | |||

| | honorific-prefix = ] | |||

| | name = Joan of Arc | |||

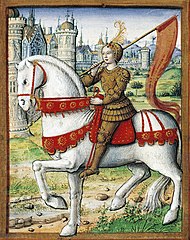

| | image = Joan of Arc miniature graded.jpg | |||

| | caption = ] depicting Joan of Arc{{efn|This historiated initial from the ] has been dated to the second half of the {{nobr|15th century}}, but it may be an ].{{sfn|Contamine|2007|p=|ps=: Cette miniature du XV{{sup|e}} siècle, très soignée (l'étendard correspond exactement à la description que Jeanne d'Arc elle-même en donnera lors de son procès){{nbsp}}... Mais c'est précisément cette exactitude, et cette coïncidence, trop belle pour être vraie, qui éveillent—ou plutôt auraient dû éveiller—les soupçons{{nbsp}}... }}}} | |||

| | alt = An image of a woman dressed in silver armor, holding a sword and a banner. | |||

| | birth_name = <!--Jeanne d'Arc (modern French)--> | |||

| | birth_date = {{circa|1412}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] | |||

| | death_date = 30 May 1431 (aged {{Approx.|19}}) | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | titles = ] | |||

| | feast_day = 30 May | |||

| | venerated_in = {{ubl|]|]{{sfn|The Calendar|2021}}}} | |||

| | beatified_date = 18 April 1909 | |||

| | beatified_by = ] | |||

| | canonized_date = 16 May 1920 | |||

| | canonized_by = ] | |||

| | patronage = France | |||

| | module = {{Infobox person|embed=yes | |||

| | signature = Jeanne d'Arc signature 16 mars 1430.svg | |||

| | signature_size = 100px}} | |||

| }} | |||

| <!-- Please add new citations in the same format as existing citations. See ] or ask for help on the talk page. --> | |||

| '''Joan of Arc''' ({{langx|fr|link=yes|Jeanne d'Arc}} {{IPA|fr|ʒan daʁk||LL-Q150 (fra)-Exilexi-Jeanne d'Arc.wav}}; {{langx|frm|Jehanne Darc}} {{IPA|frm|ʒəˈãnə ˈdark|}}; {{circa|1412}} – 30 May 1431) is a ] of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the ] and her insistence on the ] of ] during the ]. Claiming to be acting under divine guidance, she became a military leader who transcended gender roles and gained recognition as a savior of France. | |||

| Joan was born to a propertied peasant family at ] in northeast France. In 1428, she requested to be taken to Charles VII, later testifying that she was guided by visions from the ], ], and ] to help him save France from English domination. Convinced of her devotion and purity, Charles sent Joan, who was about seventeen years old, to the siege of Orléans as part of a relief army. She arrived at the city in April 1429, wielding her banner and bringing hope to the demoralized French army. Nine days after her arrival, the English abandoned the siege. Joan encouraged the French to aggressively pursue the English during the ], which culminated in another decisive ], opening the way for the French army to advance on ] unopposed, where Charles was crowned as the King of France with Joan at his side. These victories boosted French morale, paving the way for their final triumph in the Hundred Years' War several decades later. | |||

| {| class="infobox bordered" style="width: 250px; font-size: 95%;" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="0" | |||

| ! colspan="2" bgcolor="gold" style="font-size:120%"|Saint Joan of Arc | |||

| |- | |||

| |align="center" colspan="2" | ], AE II 2490)]] | |||

| |- | |||

| |align="center" colspan="2" bgcolor="gold"| | |||

| |- | |||

| |'''Born''' | |||

| |], ] (later renamed ]), ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |'''Died''' | |||

| |] ], ], France | |||

| |- | |||

| |'''Venerated in''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |||

| |''']''' | |||

| |] ] by ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |''']''' | |||

| |] ] by ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |''']''' | |||

| |30 May | |||

| |- | |||

| |''']''' | |||

| |captives; France; martyrs; opponents of Church authorities; people ridiculed for their piety; prisoners; rape victims; soldiers; Women Appointed for Voluntary Emergency Service; ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |colspan="2"|<small>Prayer to Joan of Arc for Faith</small> In the face of your enemies, in the face of harassment, ridicule, and doubt, you held firm in your faith. Even in your abandonment, alone and without friends, you held firm in your faith. Even as you faced your own mortality, you held firm in your faith. I pray that I may be as bold in my beliefs as you, St. Joan. I ask that you ride alongside me in my own battles. Help me be mindful that what is worthwhile can be won when I persist. Help me hold firm in my faith. Help me believe in my ability to act well and wisely. Amen.<br> | |||

| |} | |||

| After Charles's coronation, Joan participated in the unsuccessful ] in September 1429 and the failed ] in November. Her role in these defeats reduced the court's faith in her. In early 1430, Joan organized a company of volunteers to relieve ], which had been besieged by the ]s—French allies of the English. She was captured by Burgundian troops on 23 May. After trying unsuccessfully to escape, she was handed to the English in November. She was put on ] by Bishop ] on accusations of ], which included blaspheming by wearing men's clothes, acting upon visions that were demonic, and refusing to submit her words and deeds to the judgment of the church. She was declared guilty and ] on 30 May 1431, aged about nineteen. | |||

| '''Joan of Arc''', also known as '''Jeanne d'Arc''',<ref>Joan of Arc's name was written in a variety of ways, particularly prior to the mid-19th century. A few examples are mentioned in ]. See Pernoud and Clin, pp. 220–221.</ref> (] – ] ])<ref>Modern biographical summaries often assert a birthdate of 6 January. Actually Joan of Arc could only estimate her own age. All of the rehabilitation trial witnesses likewise estimated her age even though several of these people were her godmothers and godfathers. The 6 January claim is based on a single source: a letter from Lord Perceval de Boullainvilliers on 21 July 1429 (see Pernoud's ''Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses'', p. 98: "Boulainvilliers tells of her birth in Domrémy, and it is he who gives us an exact date, which may be the true one, saying that she was born on the night of Epiphany, January 6th"). Boulainvilliers, however, was not from Domrémy. The event was probably not recorded. The practice of ]s for non-noble births did not begin until several generations later.</ref> is a national ]ine of ] and a ] of the ]. She asserted that she had visions from God which told her to recover her homeland from ] domination late in the ]. The uncrowned ] sent her to the ] as part of a relief mission. She gained prominence when she overcame the light regard of veteran commanders and lifted the siege in only nine days. Several more swift victories led to Charles VII's coronation at ] and settled the disputed succession to the throne. | |||

| In 1456, an inquisitorial court reinvestigated Joan's trial and overturned the verdict, declaring that it was tainted by deceit and procedural errors. Joan has been described as an obedient daughter of the ], an early feminist, and a symbol of freedom and independence. She is popularly revered as a martyr. After the ], she became a national symbol of France. In 1920, Joan of Arc was ] by ] and, two years later, was declared one of the patron saints of France. She is portrayed in ], including literature, music, paintings, sculptures, and theater. | |||

| The renewed French confidence outlasted her own brief career. She refused to leave the field when she was wounded during an attempt to recapture ] that autumn. Hampered by court intrigues, she led only minor companies from then onward and fell prisoner at a skirmish near ] the following spring. A politically motivated trial convicted her of ]. The English regent ] had her ] in ]. She had been the heroine of her country at the age of seventeen and died at just nineteen. Some twenty-four years later ] reopened the case and a new finding overturned the original conviction. Her piety to the end impressed the retrial court. ] canonized her on ], ].<ref>A tribunal led by Inquisitor-General Brehal retried her case after the war. The new verdict overturned the original conviction and described the earlier proceeding as "corruption, cozenage, calumny, fraud and malice". (Accessed 12 February 2006)</ref> | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| Joan of Arc has remained an important figure in Western culture. From ] to the present, French politicians of all leanings have invoked her memory. Major writers and composers who have created works about her include ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. ] continue in film, television, and song. | |||

| ] was written in a variety of ways. There is no standard spelling of her name before the sixteenth century; her last name was usually written as "Darc" without an apostrophe, but there are variants such as "Tarc", "Dart" or "Day". Her father's name was written as "Tart" at her trial.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|pp=}} She was called "Jeanne d'Ay de Domrémy" in Charles VII's 1429 letter granting her a coat of arms.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} Joan may never have heard herself called "Jeanne d'Arc". The first written record of her being called by this name is in 1455, 24 years after her death.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|pp=}} | |||

| She was not taught to read and write in her childhood,{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} and so dictated her letters.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} She may later have learned to sign her name, as some of her letters are signed, and she may even have learned to read.{{sfnm|1a1=Lucie-Smith|1y=1976|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} Joan referred to herself in the letters as {{lang|fr|Jeanne la Pucelle}} ("Joan the Maiden") or as {{lang|fr|la Pucelle}} ("the Maiden"), emphasizing her virginity, and she signed "Jehanne". In the sixteenth century, she became known as the "Maid of Orleans".{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} | |||

| <!--- Capitalization is complicated in this subject. Titles are not capitalized except when they immediately precede a name: e.g., King Charles VI. A title is not capitalized if used in opposition to a name: e.g., The French king, Charles VI (ref. ''Chicago Manual of Style'' "Titles and Offices"). ---> | |||

| ==Birth and historical background== | |||

| == Background == | |||

| }} | |||

| The period that preceded Joan of Arc's career was one of the lowest points in ]. The ] had begun 1337 as a ] with intermittent periods of relative peace. Nearly all of the fighting had taken place in France. At the outset of Joan of Arc's career the English had almost realized their goal of a dual monarchy under English control.<ref>"If anything could have discouraged her (Joan of Arc), the state of France in 1429 should have. Wracked by a war that had lasted nearly a century at this point, half of it occupied by a foreign military...its economy broken by the constant marching of armies across its agricultural fields, their soldiers largely living off the land, and its industries blocked from the trade routes that had once made them prospersous, with no crowned king, and few others who could or would rise to take over leadership of the government or the armies, the kingdom of France was not even a shadow of its thirteenth-century prototype." DeVries, pp. 27-28.</ref> | |||

| ---- | |||

| {{legend|#ee6677|Controlled by ]}} | |||

| {{legend|#aa3377|Controlled by ]}} | |||

| {{legend|#4477aa|Controlled by ]}}]] | |||

| Joan of Arc was born {{circa|1412|lk=no}}{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Warner|3y=1981|3p=}} in ], a small village in the Meuse valley now in the ] in the north-east of France.{{sfnm|1a1=DLP|1y=2021|1p=|1ps=: Domrémy-La-Pucelle est situé en Lorraine, dans l'ouest du département des Vosges{{nbsp}}... dans la vallée de la Meuse. |2a1=Gies|2y=1981|2p=|2ps=}} Her date of birth is unknown and her statements about her age were vague.{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}}{{efn|Her birthday is sometimes given as 6 January. This is based on a letter by {{ill|Perceval de Boulainvilliers|fr}}, a councillor of Charles VII, stating that Joan was born on the ],{{sfn|Lucie-Smith|1976|p=}} but his letter is filled with literary ] that make it questionable as a statement of fact.{{sfnm|1a1=Harrison|1y=2014|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Warner|3y=1981|3p=}} There is no other evidence of her being born on Epiphany.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}}}} Her parents were ] and ]. Joan had three brothers and a sister.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2p=|Taylor|2009|3p=}} Her father was a peasant farmer{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} with about {{convert|50|acre}} of land,{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} and he supplemented the family income as a village official, collecting taxes and heading the local ].{{sfnm|1a1=Lowell|1y=1896|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} | |||

| Although the English nobility had spoken ] as a first language for several centuries after the ], this was no longer the case during Joan of Arc's lifetime. The English language had gained ascendancy in England during the fourteenth century.<ref>Pernoud and Clin, p. 323.</ref> Notwithstanding Joan of Arc's claim of a Divine mission and her enemies' claim that she proceded instead from the Devil, both she and her English opponents were Catholic, and England would remain so until the following century when ] during the reign of ]. | |||

| She was born during the ] between England and France, which had begun in 1337{{sfn|Aberth|2000|p=}} over the status of English territories in France and ].{{sfnm|Aberth|2000|1pp=|Perroy|1959|2p=}} Nearly all the fighting had taken place in France, devastating its economy.{{sfn|Aberth|2000|pp=}} At the time of Joan's birth, France was divided politically. The French king ] had recurring bouts of mental illness and was often unable to rule;{{sfn|Seward|1982|pp=}} his brother ], ], and his cousin ], ], quarreled over the regency of France. In 1407, the Duke of Burgundy ordered the ],{{sfn|Barker|2009|p=}} precipitating a civil war.{{sfn|Seward|1982|p=}} ] succeeded his father as duke at the age of thirteen and was placed in the custody of ]; his supporters became known as "]", while supporters of the Duke of Burgundy became known as "]".{{sfn|Barker|2009|p=}} The future French king ] had assumed the title of ] (heir to the throne) after the deaths of his four older brothers{{sfnm|1a1=Pernoud|1a2=Clin|1y=1986|1p=|2a1=Vale|2y=1974|2p=}} and was associated with the Armagnacs.{{sfn|Vale|1974|pp=, }} | |||

| The French king at the time of Joan's birth, ], suffered bouts of insanity and was often unable to rule. The king's brother Duke ] of Orléans and the king's cousin Duke ] of Burgundy quarreled over the regency of France and the guardianship of the royal children. This dispute escalated to accusations of an extramarital affair with Queen ] and kidnappings of the royal children and culminated when the duke of Burgundy ordered the assassination of the duke of Orléans in 1407. | |||

| ] exploited France's internal divisions when he invaded in 1415.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1pp=|Tuchman|1982|2pp=}} The Burgundians took ] in 1418.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Sizer|2007}} In 1419, the Dauphin offered a truce to negotiate peace with the Duke of Burgundy, but the duke was ] during the negotiations. The new duke of Burgundy, ], allied with the English.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1pp=|Burne|1956|2p=}} Charles VI accused the Dauphin of murdering the Duke of Burgundy and declared him unfit to inherit the French throne.{{sfn|Barker|2009|p=}} During a period of illness, Charles's wife ] stood in for him and signed the ],{{sfn|Gibbons|1996|p=}} which gave their daughter ] in marriage to Henry V, granted the succession of the French throne to their heirs, and effectively disinherited the Dauphin.{{sfn|Barker|2009|pp=}} This caused rumors that the Dauphin was not King Charles VI's son, but the offspring of an adulterous affair between Isabeau and the murdered duke of Orléans.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} In 1422, Henry V and Charles VI died within two months of each other; the 9-month-old ] was the nominal heir of the ] as agreed in the treaty, but the Dauphin also claimed the French throne.{{sfn|Curry|Hoskins|Richardson|Spencer|2015|p=}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| The factions loyal to these two men became known as the ] and the ]. The English king, ], took advantage of this turmoil and invaded France, won a dramatic ] in 1415, and proceeded to capture northern French towns.<ref>DeVries, pp. 15–19.</ref> The future French king, ], assumed the title of ] as heir to the throne at the age of fourteen after all four of his older brothers had died.<ref>Pernoud and Clin, p. 167.</ref> His first significant official act was to conclude a peace treaty with Burgundy in 1419. This ended in disaster when Armagnac partisans murdered John the Fearless during a meeting under Charles's guarantee of protection. The new duke of Burgundy, ], blamed Charles and entered an alliance with the English. Large sections of France fell to conquest.<ref>DeVries, p. 24.</ref> | |||

| }} drawing by Clément de Fauquembergue (May 1429, French National Archives){{efn|Fauquembergue's doodle on the margin of a Parliament's register is the only known contemporary representation of Joan. It is an ] depicting her with long hair and a dress rather than with her hair cut short and in armor.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p= |Maddox|2012|2p =}}}}|alt=Joan in dress facing left in profile, holding banner in her right hand and sheathed sword in her left.]] | |||

| In her youth, Joan did household chores, spun wool, helped her father in the fields and looked after their animals. Her mother provided Joan's religious education.{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} Much of Domrémy lay in the ],{{sfn|Lowell|1896|p=}} whose precise feudal status was unclear;{{sfnm|Castor|2015|1p=|Lowell|1896|2pp=|Sackville-West|1936|3pp=}} though surrounded by pro-Burgundian lands, its people were loyal to the Armagnac cause.{{sfnm|1a1=Pernoud|1a2=Clin|1y=1986|1p=}} By 1419, the war had affected the area,{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Lowell|1896|2pp=}} and in 1425, Domrémy was attacked and cattle were stolen.{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} This led to a sentiment among villagers that the English must be expelled from France to achieve peace. Joan had her first vision after this raid.{{sfn|Lowell|1896|pp=}} | |||

| In 1420 Queen Isabeau of Bavaria concluded the ], which granted the French royal succession to Henry V and his heirs in preference to her son Charles. This agreement revived rumors about her supposed affair with the late duke of Orléans and raised fresh suspicions that the dauphin was a royal bastard rather than the son of the king.<ref>Pernoud and Clin, pp. 188–189.</ref> Henry V and Charles VI died within two months of each other in 1422, leaving an infant, ], the nominal monarch of both kingdoms. Henry V's brother ], the duke of Bedford, acted as regent.<ref>DeVries, pp. 24, 26.</ref> | |||

| Joan later testified that when she was thirteen, {{Circa|1425|lk=no}}, a figure she identified as ] surrounded by angels appeared to her in the garden.{{sfnm|Harrison|2014|1p=|Sackville-West|1936|2pp=|Taylor|2009|3pp=–}} After this vision, she said she wept because she wanted them to take her with them.{{sfnm|1a1=Barstow|1y=1986|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} Throughout her life, she had visions of St. Michael,{{sfnm|1a1=Pernoud|1a2=Clin|1y=1986|1p=|2a1=Sackville-West|2y=1936|2p=|3a1=Sullivan|3y=1996|3p=}} a patron saint of the Domrémy area who was seen as a defender of France.{{sfnm|Barstow|1986|1p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2p=|Warner|1981|3p=}} She stated that she had these visions frequently and that she often had them when the church bells were rung.{{sfnm|Barstow|1986|1p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2p=}} Her visions also included St. Margaret and St. Catherine; although Joan never specified, they were probably ] and ]—those most known in the area.{{sfnm|1a1=Pernoud|1a2=Clin|1y=1986|1p=|2a1=Sullivan|2y=1996|2pp=}} Both were known as ] saints who strove against powerful enemies, were tortured and ] for their beliefs, and preserved their virtue to the death.{{sfnm|Barstow|1986|1p=|Dworkin|1987|2pp=|Sullivan|1996|3pp=}} Joan testified that she swore a vow of virginity to these voices.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Dworkin|1987|2p=}} When a young man from her village alleged that she had broken a promise of marriage, Joan stated that she had made him no promises,{{sfn|Warner|1981|pp=}} and his case was dismissed by an ecclesiastical court.{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Lowell|3y=1896|3p=|4a1=Warner|4y=1981|4p=}} | |||

| By the beginning of 1429 nearly all of northern France and some parts of the southwest were under foreign control. The English ruled Paris and the Burgundians ruled ]. The latter city was important as the traditional site of French coronations and consecrations, especially since neither claimant to the throne of France had been crowned. The English had laid ], which was the only remaining loyal French city north of the ]. Its strategic location along the river made it the last obstacle to an assault on the remaining French heartland. In the words of one modern historian, "On the fate of Orléans hung that of the entire kingdom."<ref>Pernoud and Clin, p. 10.</ref> No one was optimistic that the city could long withstand the siege.<ref>DeVries, p. 28.</ref> | |||

| During Joan's youth, a prophecy circulating in the French countryside, based on the visions of {{ill|Marie Robine of Avignon|fr|Marie Robine}}, promised an armed virgin would come forth to save France.{{sfnm|Barstow|1986|1p=|Taylor|2009|2p=|Warner|1981|3pp=}} Another prophecy, attributed to ], stated that a virgin carrying a banner would put an end to France's suffering.{{sfnm|Fraioli|2000|1p=|Harrison|2014|2p=|Taylor|2006|3p=|Warner|1981|4p=}} Joan implied she was this promised maiden, reminding the people around her that there was a saying that France would be destroyed by a woman but would be restored by a virgin.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Harrison|2014|2p=| Pernoud|1962|3p=}}{{efn|The woman in this saying is assumed to refer to Isabeau of Bavaria,{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Harrison|2014|2p=|Pernoud|1962|3p=}} but this is uncertain.{{sfnm|Adams|2010|1pp=|Fraioli|2000|2p=}}}} In May 1428,{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} she asked her uncle to take her to the nearby town of ], where she petitioned the garrison commander, ], for an armed escort to the Armagnac court at ]. Baudricourt harshly refused and sent her home.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1pp= |Harrison|2014|2pp=}} In July, Domrémy was raided by Burgundian forces{{sfnm|1a1=Lowell|1y=1896|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2pp=}} which set fire to the town, destroyed the crops, and forced Joan, her family and the other townspeople to flee.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Richey|2003|2p=}} She returned to Vaucouleurs in January 1429. Her petition was refused again,{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} but by this time she had gained the support of two of Baudricourt's soldiers, ] and ].{{sfnm|Harrison|2014|1pp=,|Lowell|1896|2pp=|Sackville-West|1936|3pp=}} Meanwhile, she was summoned to ] under safe conduct by ], who had heard about Joan during her stay at Vaucouleurs. The duke was ill and thought she might have supernatural powers that could cure him. She offered no cures, but reprimanded him for living with his mistress.{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2pp=}} | |||

| ==Life== | |||

| ===Childhood=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Henry V's brothers, ], and ], had continued the English conquest of France.{{sfn|DeVries|1999|pp=}} Most of northern France, Paris, and parts of southwestern France were under Anglo-Burgundian control. The Burgundians controlled ], the traditional site for the coronation of French kings; Charles had not yet been ], and doing so at Reims would help legitimize his claim to the throne.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Vale|1974|2p=}} In July 1428, the English had started to surround Orléans and had nearly isolated it from the rest of Charles's territory by capturing many of the smaller bridge towns on the ] River.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1pp=|DeVries|1999|2p=}} Orléans was strategically important as the last obstacle to an assault on the remainder of Charles's territory.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} According to Joan's later testimony, it was around this period that her visions told her to leave Domrémy to help the Dauphin Charles.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Goldstone|2012|2pp=|Sackville-West|1936|3p=}} | |||

| Joan of Arc was born to ] and ] in ], a village which was then in the duchy of Bar (and later annexed to the province of Lorraine and renamed Domrémy-la-Pucelle).<ref>Condemnation trial, p. 37. (Accessed 23 March 2006)</ref> Her parents owned about 50 acres (20 ha) of land and her father supplemented his farming work with a minor position as a village official, collecting taxes and heading the town watch.<ref>Pernoud and Clin, p. 221.</ref> They lived in an isolated patch of northeastern territory that remained loyal to the French crown despite being surrounded by Burgundian lands. Several local raids occurred during Joan of Arc's childhood and on one occasion her village was burned. | |||

| Baudricourt agreed to a third meeting with Joan in February 1429, around the time the English captured an Armagnac relief convoy at the ] during the ]. Their conversations,{{sfnm|Lowell|1896|1p=|Sackville-West|1936|2pp=}} along with Metz and Poulengy's support,{{sfnm|1a1=Castor|1y=2015|1p=|2a1=Lucie-Smith|2y=1976|2p=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3p=}} convinced Baudricourt to allow her to go to Chinon for an audience with the Dauphin. Joan traveled with an escort of six soldiers.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Lowell|1896|2p=}} Before leaving, Joan put on men's clothes,{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2pp=|Warner|1981|3pp=}} which were provided by her escorts and the people of Vaucouleurs.{{sfnm|1a1=Lowell|1y=1896|1p=|2a1=Lucie-Smith|2y=1976|2p=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3pp=}} She continued to wear men's clothes for the remainder of her life.{{sfn|Crane|1996|p=}} | |||

| Joan of Arc later testified that she experienced her first vision around 1424. She would report that ], ], and ] told her to drive out the English and bring the dauphin to Reims for his coronation.<ref>Condemnation trial, pp. 58 - 59. (Accessed 23 March 2006)</ref> At the age of sixteen she asked a kinsman, Durand Lassois, to bring her to nearby ] where she petitioned the garrison commander, Count ], for permission to visit the royal French court at ]. Baudricourt's sarcastic response did not deter her.<ref>DeVries, pp. 37–40.</ref> She returned the following January and gained support from two men of standing: Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulegny.<ref>Nullification trial testimony of Jean de Metz. (Accessed 12 February 2006)</ref> Under their auspices she gained a second interview where she made an apparently miraculous prediction about a ] near Orléans.<ref>Oliphant, ch. 2. (Accessed 12 February 2006)</ref> | |||

| == |

==Chinon== | ||

| ] by ] ({{Circa|1444|lk=no}}, ], Paris)|alt=Miniature of Charles the seventh of France.]] | |||

| Charles VII met Joan for the first time at the Royal Court in Chinon in late February or early March 1429,{{sfnm|1a1=Vale|1y=1974|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a=Lowell|3y=1896|3p=|ps=, fn 1}} when she was seventeen{{sfnm|Taylor|2009|1p=|Warner|1981|2p=}} and he was twenty-six.{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} She told him that she had come to raise the siege of Orléans and to lead him to Reims for his coronation.{{sfnm|Castor|2015|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=|Lowell|1896|3p= }} They had a private exchange that made a strong impression on Charles; ], Joan's confessor, later testified that Joan told him she had reassured the Dauphin that he was Charles VI's son and the legitimate king.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=}} | |||

| ] where Joan of Arc met King Charles VII. The castle's only remaining intact tower has become a museum to Joan of Arc.]] | |||

| Charles and his council needed more assurance,{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} sending Joan to ] to be examined by a council of theologians, who declared that she was a good person and a good Catholic.{{sfnm|Castor|2015|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=|Vale=1974|3p=}} They did not render a decision on the source of Joan's inspiration, but agreed that sending her to Orléans could be useful to the king{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Richey|2003|2p=}} and would test whether her inspiration was of divine origin.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Vale|1974|2p=}} Joan was then sent to Tours to be physically examined by women directed by Charles's mother-in-law ], who verified her virginity.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2p=}} This was to establish if she could indeed be the prophesied virgin savior of France,{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=}} to show the purity of her devotion,{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} and to ensure she had not consorted with the Devil.{{sfnm|Michelet|1855|1p=|Sackville-West|1936|2p=}} | |||

| Robert de Baudricourt granted Joan of Arc an escort to visit Chinon after news from the front confirmed her prediction. She made the journey through hostile Burgundian territory in male disguise.<ref>Richey, p. 4. </ref> Upon arriving at the royal court she impressed Charles VII during a private conference. He then ordered background inquiries and a theological examination at ] to verify her morality. During this time Charles's mother-in-law ] was financing a relief expedition to Orléans. Joan of Arc petitioned for permission to travel with the army and wear the equipment of a knight. She depended on donations for her armor, horse, sword, banner, and entourage. Historian Stephen W. Richey explains her attraction as the only source of hope for a regime that was near collapse: | |||

| The Dauphin, reassured by the results of these tests, commissioned ] for her. She designed her own banner and had a sword brought to her from under the altar in the church at ].{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1pp=|2a1=Gies|2y=1981|2pp=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3pp=}} Around this time she began calling herself "Joan the Maiden", emphasizing her virginity as a sign of her mission.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} | |||

| :"''After years of one humiliating defeat after another, both the military and civil leadership of France were demoralized and discredited. When the Dauphin Charles granted Joan’s urgent request to be equipped for war and placed at the head of his army, his decision must have been based in large part on the knowledge that every orthodox, every rational, option had been tried and had failed. Only a regime in the final straits of desperation would pay any heed to an illiterate farm girl who claimed that voices from God were instructing her to take charge of her country’s army and lead it to victory.''"<ref>Richey, "Joan of Arc: A Military Appreciation". (Accessed 12 February 2006)</ref> | |||

| Before Joan's arrival at Chinon, the Armagnac strategic situation was bad but not hopeless.{{sfnm|Warner|1981|1p=|Vale|1974|2p=}} The Armagnac forces were prepared to endure a prolonged siege at Orléans,{{sfn|Gies|1981|pp=}} the Burgundians had recently withdrawn from the siege due to disagreements about territory,{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=}} and the English were debating whether to continue.{{sfn|Vale|1974|p=}} Nonetheless, after almost a century of war, the Armagnacs were demoralized.{{sfn|DeVries|1999|p=}} Once Joan joined the Dauphin's cause, her personality began to raise their spirits,{{sfn|Richey|2003|p=}} inspiring devotion and the hope of divine assistance.{{sfnm|1a1=Harrison|1y=2014|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} Her belief in the divine origin of her mission turned the longstanding Anglo-French conflict over inheritance into a religious war.{{sfn|Vale|1974|p=}} Before beginning the journey to Orléans, Joan dictated a letter to the Duke of Bedford warning him that she was sent by God to drive him out of France.{{sfnm|1a1=Lucie-Smith|1y=1976|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2pp=|3a1=Richey|3y=2003|3pp=}} | |||

| {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 0em; margin-right: 1em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | |||

| | style="text-align: left;" | "King of England, and you, duke of Bedford, who call yourself regent of the kingdom of France...settle your debt to the king of Heaven; return to the Maiden, who is envoy of the king of Heaven, the keys to all the good towns you took and violated in France." | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align: left;" | ''Joan of Arc, Letter to the English, March - April 1429; Quicherat I, p. 240, trans. Misplaced Pages.'' | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Military campaigns== | |||

| Joan of Arc arrived at the ] on ] ], but ], the acting head of the Orléans ducal family, initially excluded her from war councils and failed to inform her when the army engaged the enemy.<ref>Histories and fictional works often refer to this man by other names. Some call him count of Dunois in reference to a title he received years after Joan of Arc's death. During her lifetime he preferred Bastard of Orléans, which his contemporaries understood as an honor because it described him as a first cousin of King Charles VII. That name often confuses modern readers because "bastard" has become a popular insult. "Jean d'Orleans" is less precise but not anachronistic. For a short biography see Pernoud and Clin, pp. 180-181.</ref> This did not prevent her from being present at most councils and battles. The extent of her actual military leadership is a subject of historical debate. Traditional historians such as Edouard Perroy conclude that she was a standard bearer whose primary effect was on morale.<ref>Perroy, p. 283.</ref> This type of analysis usually relies on the condemnation trial testimony, where Joan of Arc stated that she preferred her standard to her sword. Recent scholarship that focuses on the rehabilitation trial testimony asserts that her fellow officers esteemed her as a skilled tactician and a successful strategist. Stephen W. Richey's opinion is one example: "She proceeded to lead the army in an astounding series of victories that reversed the tide of the war."<ref>Richey, p. 4.</ref> In either case, historians agree that the army enjoyed remarkable success during her brief career.<ref>Pernoud and Clin, p. 230.</ref> | |||

| === |

===Orléans=== | ||

| ] (1887, ])|alt=Joan of Arc on horseback with armor and holding banner being greeted by the people of Orléans.]] | |||

| In the last week of April 1429, Joan set out from ] as part of an army carrying supplies for the relief of Orléans.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=}} She arrived there on 29 April{{sfn|Barker|2009 |p=}} and met the commander ], the ] of Orléans.{{sfn|Richey|2003|p=}} Orléans was not completely cut off, and Dunois got her into the city, where she was greeted enthusiastically.{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1pp=|2a1=Gies|2y=1981|2p=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3pp=}} Joan was initially treated as a figurehead to raise morale,{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Warner|1981|2p=}} flying her banner on the battlefield.{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Warner|3y=1981|3p=}} She was not given any formal command{{sfnm|Richey|2003|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=}} or included in military councils{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1pp=,|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Warner|3y=1981|3p=}} but quickly gained the support of the Armagnac troops. She always seemed to be present where the fighting was most intense, she frequently stayed with the front ranks, and she gave them a sense she was fighting for their salvation.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1996|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Richey|3y=2003|3p=}} Armagnac commanders would sometimes accept the advice she gave them, such as deciding what position to attack, when to continue an assault, and how to place artillery.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1pp=|Gies|1981|2p=}} | |||

| ] is one of the few surviving fortifications from Joan of Arc's battles. English defenders retreated to the tower at upper right after the French breached the town wall.]] | |||

| On 4 May, the Armagnacs went on the offensive, attacking the outlying {{lang|fr|bastille de Saint-Loup}} (fortress of ]). Once Joan learned of the attack, she rode out with her banner to the site of the battle, a mile east of Orléans. She arrived as the Armagnac soldiers were retreating after a failed assault. Her appearance rallied the soldiers, who attacked again and took the fortress.{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1p=|2a1=Gies|2y=1981|2pp=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3pp=}} On 5 May, no combat occurred since it was ], a ]. She dictated another letter to the English warning them to leave France and had it tied to a ], which was fired by a crossbowman.{{sfnm|1a1=Harrison|1y=2014|1pp=|2a1=Richey|2y=2003|2p=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3p=}} | |||

| Joan of Arc defied the cautious strategy that had characterized French leadership. During the five months of siege before her arrival the defenders of Orléans had attempted only one aggressive move and that had ended in disaster. On 4 May the French attacked and captured the outlying fortress of Saint Loup, which she followed on 5 May with a march to a second fortress called Saint Jean le Blanc. Finding it deserted, this became a bloodless victory. The next day she opposed Jean d'Orleans at a war council where she demanded another assault on the enemy. D'Orleans ordered the city gates locked to prevent another battle, but Joan of Arc summoned the townsmen and common soldiers and forced the mayor to unlock a gate. With the aid of only one captain she rode out and captured the fortress of Saint Augustins. That evening she learned she had been excluded from a war council where the leaders had decided to wait for reinforcements before acting again. Disregarding this decision, she insisted on assaulting the main English stronghold called "les Tourelles" on 7 May.<ref>DeVries, pp. 74-83</ref> Contemporaries acknowledged her as the hero of the engagement after she pulled an arrow from her own shoulder and returned wounded to lead the final charge.<ref>Devout Catholics regard this as proof of her divine mission. At Chinon and Poitiers she had declared that she would give a sign at Orléans. The lifting of the siege gained her the support of prominent clergy such as the Archbishop of Embrun and theologian ], who both wrote supportive treatises immediately following this event.</ref> | |||

| The Armagnacs resumed their offensive on 6 May, capturing ], which the English had deserted.{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} The Armagnac commanders wanted to stop, but Joan encouraged them to launch an ], an English fortress built around a monastery.{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Richey|3y=2003|3p=}} After its capture,{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1p=|2a1=DeVries|2y=1999|2pp=| 3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3pp=}} the Armagnac commanders wanted to consolidate their gains, but Joan again argued for continuing the offensive.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1p=|2a1=Gies|2y=1981|2p=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3p=}} On the morning of 7 May, the Armagnacs attacked the main English stronghold, ''les Tourelles''. Joan was wounded by an arrow between the neck and shoulder while holding her banner in the trench on the south bank of the river but later returned to encourage the final assault that took the fortress.{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Richey|3y=2003|3p=}} The English retreated from Orléans on 8 May, ending the siege.{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1p=|2a1=DeVries|2y=1999|2p=|3a1=Gies|3y=1981|3p=}} | |||

| {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 0em; margin-right: 1em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | |||

| | style="text-align: left;" | "...the Maiden lets you know that here, in eight days, she has chased the English out of all the places they held on the river Loire by attack or other means: they are dead or prisoners or discouraged in battle. Believe what you have heard about the earl of Suffolk, the lord la Pole and his brother, the lord Talbot, the lord Scales, and Sir Fastolf; many more knights and captains than these are defeated." | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align: left;" | ''Joan of Arc, Letter to the citizens of ], 25 June 1429; Quicherat V, pp. 125-126, trans. Misplaced Pages.'' | |||

| |} | |||

| At Chinon, Joan had declared that she was sent by God.{{sfnm|1a1=Pernoud|1a2=Clin|1y=1986|1p=|2a1=Warner|2y=1981|2p=}} At Poitiers, when she was asked to show a sign demonstrating this claim, she replied that it would be given if she were brought to Orléans. The lifting of the siege was interpreted by many people to be that sign.{{sfnm|1a1=Pernoud|1a2=Clin|1y=1986|1p=|2a1=Warner|2y=1981|2p=}} Prominent clergy such as {{ill|Jacques Gélu|fr}}, ],{{sfn|Fraioli|2000|pp=–}} and the theologian ]{{sfn|Michelet|1855|pp=}} wrote treatises in support of Joan after this victory.{{sfnm|Lang|1909|1pp= |Warner|1981|2p=}} In contrast, the English saw the ability of this peasant girl to defeat their armies as proof she was possessed by the devil.{{sfnm|Boyd|1986|1p=|DeVries|1996|2p=|Gies|1981|3p=|Seward|1982|4pp=}} | |||

| The sudden victory at Orléans led to many proposals for offensive action. The English expected an attempt to recapture Paris or an attack on Normandy. In the aftermath of the unexpected victory, she persuaded Charles VII to grant her co-command of the army with Duke ] and gained royal permission for her plan to recapture nearby bridges along the Loire as a prelude to an advance on Reims and a coronation. Hers was a bold proposal because Reims was roughly twice as far away as Paris and deep in enemy territory.<ref>DeVries, pp. 96–97.</ref> | |||

| ===Loire Campaign=== | |||

| ], traditional site of French coronations. The structure had additional spires prior to a 1481 fire.]] | |||

| {{Infobox military person | |||

| | width_style = person | |||

| | name = ] Joan of Arc | |||

| | allegiance = ] | |||

| | battles_label = Conflict | |||

| | battles = ''']''' | |||

| | module = {{OSM Location map | |||

| | coord = {{coord|48|2}} | |||

| | zoom = 5 | |||

| | float = right | |||

| | nolabels = 1 | |||

| | width = 235 | |||

| | height = 160 | |||

| |scalemark=0 | |||

| | title = Important locations | |||

| | caption = {{legend-line|#000000 dashed 2px|Joan's journey to ]}}{{legend|#4daf4a|] and ]}}{{legend-line|#332288 dashed 2px|]}}{{legend|#377eb8|Reims and the ]}}{{legend|#984ea3|Campaign against Perrinet Gressard}}{{legend|#e41a1c|]}}{{legend|black|Other locations}} | |||

| |mark=Joan of Arc overlay file.png | |||

| |mark-coord={{coord|48|2}} | |||

| |mark-size=230 | |||

| |mark-dim=1.48 | |||

| |mark-title=none | |||

| | shape1 = circle | |||

| The army recovered ] on 12 June, ] on 15 June, then ] on 17 June. The duke of Alençon agreed to all of Joan of Arc's decisions. Other commanders including Jean d'Orléans had been impressed with her performance at Orléans, and became her supporters. Alençon credited Joan for saving his life at Jargeau, where she warned him of an imminent artillery attack.<ref>Nullification trial testimony of Jean, Duke of Alençon. (Accessed 12 February 2006)</ref> During the same battle she withstood a blow from a stone cannonball to her helmet as she climbed a scaling ladder. An expected English relief force arrived in the area on 18 June under the command of Sir ]. The ] might be compared to Agincourt in reverse. The French vanguard attacked before the English ] could finish defensive preparations. A rout ensued that decimated the main body of the English army and killed or captured most of its commanders. Fastolf escaped with a small band of soldiers and became the scapegoat for the English humiliation. The French suffered minimal losses.<ref>DeVries, pp. 114–115.</ref> | |||

| | label1 = Domrémy | |||

| | label-pos1 = bottom | |||

| | mark-coord1 = {{coord|48.44|5.68}} | |||

| | mark-title1 = ]- Joan's birthplace and childhood home | |||

| | mark-description1 = ] | |||

| | shape-color1 = black | |||

| | label-color1 = black | |||

| |label-offset-x1 = 16 | |||

| |label-offset-y1 = -2 | |||

| |label-size1 = 8 | |||

| | mark-size1 = 7 | |||

| | shape2 = circle | |||

| The French army set out for Reims from Gien-sur-Loire on 29 June and accepted the conditional surrender of the Burgundian-held city of ] on 3 July. Every other town in their path returned to French allegiance without resistance. ], the site of the treaty that had tried to disinherit Charles VII, capitulated after a bloodless four-day siege.<ref>Ibid., pp. 122–126.</ref> The army was in short supply of food by the time it reached Troyes. Edward Lucie-Smith cites this as an example of why Joan of Arc was more lucky than skilled: a wandering friar named Brother Richard had been preaching about the end of the world at Troyes and had convinced local residents to plant beans, a crop with an early harvest. The hungry army arrived as the beans ripened.<ref>Lucie-Smith, pp. 156–160.</ref> | |||

| | label2 = Vaucouleurs | |||

| | mark-coord2 = {{coord|48.60|5.67}} | |||

| | mark-title2 = ]- Site of Joan's three meetings with ] to request being sent to ]'s Court: May and January 1428, February 1429. | |||

| | mark-description2 = ] | |||

| | shape-color2 = black | |||

| | label-color2 = black | |||

| |label-size2 = 8 | |||

| |label-pos2 = top | |||

| |label-offset-y2 = 2 | |||

| |label-offset-x2 = 0 | |||

| | mark-size2 = 7 | |||

| | shape3 = circle | |||

| {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 0em; margin-right: 1em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | |||

| | label3 = | |||

| | style="text-align: left;" | "Prince of Burgundy, I pray of you - I beg and humbly supplicate - that you make no more war with the holy kingdom of France. Withdraw your people swiftly from certain places and fortresses of this holy kingdom, and on behalf of the gentle king of France I say he is ready to make peace with you, by his honor." | |||

| | mark-coord3 = {{coord|48.6936|6.1846}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | mark-title3 = ]- Joan meets Charles II, Duke of Lorraine: early winter 1429 | |||

| | style="text-align: left;" | ''Joan of Arc, Letter to Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy, 17 July 1429; Quicherat V, pp. 126-127, trans. Misplaced Pages.'' | |||

| | mark-description3 = ] | |||

| |} | |||

| | shape-color3 = black | |||

| | label-color3 = black | |||

| | mark-size3 = 0 | |||

| | shape4 = circle | |||

| Reims opened its gates on 16 July. The coronation took place the following morning. Although Joan and the duke of Alençon urged a prompt march on Paris, the royal court pursued a negotiated truce with the duke of Burgundy. Duke Philip the Good broke the agreement, using it as a stalling tactic to reinforce the defense of Paris.<ref>DeVries, p. 134.</ref> The French army marched through towns near Paris during the interim and accepted more peaceful surrenders. The duke of Bedford headed an English force and confronted the French army in a standoff on 15 August. The French assault at Paris ensued on 8 September. Despite a crossbow bolt wound to the leg, Joan of Arc continued directing the troops until the day's fighting ended. The following morning she received a royal order to withdraw. Most historians blame French grand chamberlain ] for the political blunders that followed the coronation.<ref>These range from mild associations of intrigue to scholarly invective. For an empassioned statement see Gower, ch. 4. (Accessed 12 February 2006) Milder examples are Pernoud and Clin, pp. 78–80; DeVries, p. 135; and Oliphant, ch. 6. (Accessed 12 February 2006)</ref> | |||

| | label4 = Chinon | |||

| | mark-coord4 = {{coord|47.168056|0.23611}} | |||

| | mark-title4 = ]- Joan meets ] at his court: March 1429 | |||

| | mark-description4 = ] | |||

| | shape-color4 = black | |||

| | label-color4 = black | |||

| | label-size4=11 | |||

| | label-pos4=top | |||

| |label-offset-x4= -18 | |||

| |label-offset-y4= 2 | |||

| | mark-size4 = 7 | |||

| | shape5 = circle | |||

| === Capture === | |||

| | label5 = | |||

| ] where she was imprisoned during her trial.]] | |||

| | mark-coord5 = {{coord|46.5803|0.3493}} | |||

| | mark-title5 = ]- Joan examined by theologians of ]'s court during March–April 1429 | |||

| | mark-description5 = ] | |||

| | shape-color5 = black | |||

| | label-color5 = black | |||

| | mark-size5 = 0 | |||

| | shape6 = circle | |||

| After minor action at La-Charité-sur-Loire in November and December, Joan went to ] the following April to defend against an ]. A skirmish on ] ] led to her capture. When she ordered a retreat she assumed the place of honor as the last to leave the field. Burgundians surrounded the rear guard.<ref>DeVries, pp. 161-170.</ref> | |||

| | label6 = | |||

| | mark-coord6 = {{coord|47.3971|0.6936}} | |||

| | mark-title6 = ]- Joan's virginity attested; Joan receives her armor, banner and sword: early April 1429. | |||

| | mark-description6 = ] | |||

| | shape-color6 = black | |||

| | label-color6 = black | |||

| | mark-size6 = 0 | |||

| | shape7 = circle | |||

| {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 0em; margin-right: 1em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | |||

| | label7 = | |||

| | style="text-align: left;" | "It is true that the king has made a truce with the duke of Burgundy for fifteen days and that the duke is to turn over the city of Paris at the end of fifteen days. Yet you should not marvel if I do not enter that city so quickly. I am not content with these truces and do not know if I will keep them, but if I hold them it will only be to guard the king's honor: no matter how much they abuse the royal blood, I will keep and maintain the royal army in case they make no peace at the end of those fifteen days." | |||

| | mark-coord7 = {{coord|47.59|1.33}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | |

| mark-title7 = ]- Joan joins the army to relieve the siege of Orléans: 24 April 1429. | ||

| | mark-description7 = ] | |||

| |} | |||

| | shape-color7 = black | |||

| | label-color7 = black | |||

| | mark-size7 = 0 | |||

| | shape8 = circle | |||

| It was customary for a captive's family to ransom a prisoner of war. Joan of Arc and her family lacked the financial resources. Many historians condemn Charles VII for failing to intervene. She attempted several escapes, on one occasion leaping from a seventy foot tower to the soft earth of a dry moat. The English government eventually purchased her from Duke Philip of Burgundy. Bishop ] of ], an English partisan, assumed a prominent role in these negotiations and her later trial. | |||

| | label8 = Orléans | |||

| |label-color8=black | |||

| |label-size8= 11 | |||

| |label-pos8= top | |||

| |label-offset-x8= -20 | |||

| |label-offset-y8= 2 | |||

| | mark-coord8 = {{coord|47.90| 1.91}} | |||

| | mark-title8 = ]: 29 April 1429- 8 May 1429 | |||

| | mark-description8 = ] | |||

| | shape-color8 = #4daf4a | |||

| | mark-size8 = 10 | |||

| | label9 = | |||

| | shape9 = circle | |||

| | mark-coord9 = {{coord|47.87| 2.12}} | |||

| | mark-title9 = ]: on 11 June 1429 | |||

| | mark-description9 = ] | |||

| | shape-color9 = #4daf4a | |||

| | label-color9 = #4daf4a | |||

| | mark-size9 = 0 | |||

| | label10 = | |||

| | shape10 = circle | |||

| | mark-coord10 = {{coord|47.82|1.70}} | |||

| | mark-title10 = ]: on 15–16 June 1429 | |||

| | mark-description10 = ] | |||

| | shape-color10 = #4daf4a | |||

| | label-color10 = #4daf4a | |||

| | mark-size10 = 0 | |||

| | label11 = | |||

| | shape11 = circle | |||

| | mark-coord11 = {{coord|47.78|1.63}} | |||

| | mark-title11 = ]: on 16 June 1429 | |||

| | mark-description11 = ] | |||

| | shape-color11 = #4daf4a | |||

| | label-color11 = #4daf4a | |||

| | mark-size11 = 0 | |||

| | label12 = | |||

| | shape12 = circle | |||

| | mark-coord12 = {{coord|48.03|1.70}} | |||

| | mark-title12 = ]: 18 June 1429 | |||

| | mark-description12 = SE of ] | |||

| | shape-color12 = #4daf4a | |||

| | label-color12 = #4daf4a | |||

| | mark-size12 = 0 | |||

| | label13 = Reims | |||

| | shape13 = circle | |||

| |label-pos13 = top | |||

| | mark-coord13 = {{coord|49.26|4.03}} | |||

| | mark-title13 = Joan and Charles arrive at ]: 16 July 1429 | |||

| | mark-description13 = ] | |||

| | shape-color13 = #377eb8 | |||

| | label-color13 = black | |||

| | label-offset-x13 = 5 | |||

| | label-offset-y13 = 2 | |||

| | label-size13= 11 | |||

| | mark-size13 = 10 | |||

| | shape14 = circle | |||

| | label14 = Paris | |||

| | mark-coord14 = {{coord|48.86|2.32}} | |||

| | mark-title14 = ]: 3–8 September 1429 | |||

| | mark-description14 = ] | |||

| | shape-color14 = #377eb8 | |||

| | mark-size14 = 7 | |||

| | label-size14= 11 | |||

| | label-color14 = black | |||

| | label-pos14 = bottom | |||

| |label-offset-x14= 10 | |||

| |label-offset-y14= 0 | |||

| | shape15 = circle | |||

| | label15 = | |||

| | mark-coord15 = {{coord|46.79|3.12}} | |||

| | mark-title15 = ]: October–November 1429 | |||

| | mark-description15 = ] | |||

| | shape-color15 = #984ea3 | |||

| | label-color15 = #984ea3 | |||

| | mark-size15 = 0 | |||

| | shape16 = circle | |||

| | mark-coord16 = {{coord|47.17|3.02}} | |||

| | mark-title16 = ]: 24 November–25 December 1429 | |||

| | mark-description16 = ] | |||

| | shape-color16 = #984ea3 | |||

| | mark-size16 = 7 | |||

| |label16= La Charité | |||

| |label-size16= 8 | |||

| |label-color16=black | |||

| |label-pos16 = right | |||

| |label-offset-x16=0 | |||

| |label-offset-y16=0 | |||

| | shape17 = circle | |||

| | label17 = | |||

| | mark-coord17 = {{coord|48.5406|2.66}} | |||

| | mark-title17 = ]- Liberated by Joan's forces: April 1430. | |||

| | mark-description17 = ] | |||

| | shape-color17 = #e41a1c | |||

| | label-color17 = #e41a1c | |||

| | mark-size17 = 0 | |||

| | shape18 = circle | |||

| | label18 = | |||

| | mark-coord18 = {{coord|48.8788|2.7075}} | |||

| | mark-title18 = ]- Site of battle against Franquet D'Arras: April 1430. | |||

| | mark-description18 = ] | |||

| | shape-color18 = #e41a1c | |||

| | label-color18 = #e41a1c | |||

| | mark-size18 = 0 | |||

| | label19 = Compiègne | |||

| |label-color19=black | |||

| |label-size19=8 | |||

| | mark-coord19 = {{coord|49.41|2.82}} | |||

| | mark-title19 = ]: 14–23 May 1493 | |||

| | mark-description19 = ] | |||

| | shape-color19 = #e41a1c | |||

| |label-pos19 = top | |||

| |label-offset-x19 = -10 | |||

| |label-offset-y19 = 0 | |||

| | mark-size19 = 7 | |||

| | label20 = | |||

| | mark-coord20 = {{coord|49.42133|2.82345}} | |||

| | mark-title20 = ]- Site of Joan's capture by Burgundians: 23 May 1430. | |||

| | mark-description20 = ] | |||

| | shape-color20 = #DB3123 | |||

| | label-color20 = #DB3123 | |||

| | mark-size20 = 7 | |||

| | shape21 = circle | |||

| | label21 = | |||

| | mark-coord21 = {{coord|49.6608|2.9133}} | |||

| | mark-title21 = ]- Joan is imprisoned in the castle keep and attempts to escape: May–June 1430. | |||

| | mark-description21 = ] | |||

| | shape-color21 = black | |||

| | label-color21 = black | |||

| | mark-size21 = 0 | |||

| | shape22 = circle | |||

| | label22 = | |||

| | mark-coord22 = {{coord|50.00|3.31}} | |||

| | mark-title22 = ]- Joan imprisoned here after her first escape attempt; Jumps from tower in another escape attempt: June–November 1430. | |||

| | mark-description22 = ] | |||

| | shape-color22 = black | |||

| | label-color22 = black | |||

| | mark-size22 = 0 | |||

| | shape23 = circle | |||

| | label23 = | |||

| | mark-coord23 = {{coord|50.292|2.78}} | |||

| | mark-title23 = ]- Joan imprisoned here after her second escape attempt: November–December 1430 | |||

| | mark-description23 = ] | |||

| | shape-color23 = black | |||

| | label-color23 = black | |||

| | mark-size23 = 0 | |||

| | shape24 = circle | |||

| | label24 = Rouen | |||

| | label-size24= 11 | |||

| | mark-coord24 = {{coord|49.44|1.09}} | |||

| | mark-title24 = ]- Joan's final prison, place of trail and execution: 25 December 1430–30 May 1431. | |||

| | mark-description24 = ] | |||

| | shape-color24 = black | |||

| | label-color24 = black | |||

| |label-pos24 = left | |||

| |label-offset-x24= 7 | |||

| |label-offset-y24= 10 | |||

| |mark-size24=7 | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| After the success at Orléans, Joan insisted that the Armagnac forces should advance promptly toward Reims to crown the Dauphin.{{sfnm|1a1=Harrison|1y=2014|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Richey|3y=2003|3p=}} Charles allowed her to accompany the army under the command of ],{{sfnm|Lucie-Smith|1976|1p=|Richey|2003|2p=}} who collaboratively worked with Joan and regularly heeded her advice.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=}} Before advancing toward Reims, the Armagnacs needed to recapture the bridge towns along the Loire: ], ], and ]. This would clear the way for Charles and his entourage, who would have to cross the Loire near Orléans to get from Chinon to Reims.{{sfnm|Castor|2015|1p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2pp=|Lowell|1896|3p=}} | |||

| The ] began on 11 June when the Armagnac forces led by Alençon and Joan arrived at Jargeau{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Barker|2009|2p=}} and forced the English to withdraw inside the town's walls. Joan sent a message to the English to surrender; they refused{{sfnm|Burne|1956|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|3p=}} and she advocated for a direct assault on the walls the next day.{{sfnm|Burne|1956|1p=|Castor|2015|2p=|DeVries|1999|3p=}} By the end of the day, the town was taken. The Armagnac took few prisoners and many of the English who surrendered were killed.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1pp=|DeVries|1999|2p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|3p=}} During this campaign, Joan continued to serve in the thick of battle. She began scaling a siege ladder with her banner in hand but before she could climb the wall, she was struck by a stone which split her helmet.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Lowell|1896|2p=}} | |||

| Alençon and Joan's army advanced on ]. On 15 June, they took control of the town's bridge, and the English garrison withdrew to a castle on the Loire's north bank.{{sfn|Burne|1956|p=}} Most of the army continued on the south bank of the Loire to ].{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Burne|1956|2p=|Gies|1981|3pp=}} | |||

| Meanwhile, the English army from Paris under the command of Sir ] had linked up with the garrison in Meung and traveled along the north bank of the Loire to relieve Beaugency.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Burne|1956|2pp=}} Unaware of this, the English garrison at Beaugency surrendered on 18 June.{{sfn|Barker|2009|p=}} The main English army retreated toward Paris; Joan urged the Armagnacs to pursue them, and the two armies clashed at the ] later that day. The English had prepared their forces to ambush an Armagnac attack with hidden ],{{sfn|DeVries|1999|p=}} but the Armagnac vanguard detected and scattered them. A rout ensued that decimated the English army. Fastolf escaped with a small band of soldiers, but many of the English leaders were captured.{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} Joan arrived at the battlefield too late to participate in the decisive action,{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=}} but her encouragement to pursue the English had made the victory possible.{{sfnm|Burne|1956|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=|Harrison|2014|3pp=|Richey|2003|4p=}} | |||

| ===Coronation and siege of Paris=== | |||

| ] in ]' ''Chronicon abbreviatum regum Francorum''; Joan of Arc stands holding a banner of France to his left. Unknown author (15th century).|alt=Miniature of coronation of King Charles the seventh of France]] | |||

| After the destruction of the English army at Patay, some Armagnac leaders argued for an invasion of English-held Normandy, but Joan remained insistent that Charles must be crowned.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Gies|1981|2pp=,}} The Dauphin agreed, and the army left ] on 29 June to ].{{sfnm|1a1=Michelet|1y=1855|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} The advance was nearly unopposed.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Burne|1956|2p=}} The Burgundian-held town of ] surrendered on 3 July after three days of negotiations,{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=}} and other towns in the army's path returned to Armagnac allegiance without resistance.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=}} ], which had a small garrison of English and Burgundian troops,{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Michelet|1855|2p=}} was the only one to resist. After four days of negotiation, Joan ordered the soldiers to fill the city's moat with wood and directed the placement of artillery. Fearing an assault, Troyes negotiated a surrender.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1p=|2a1=Michelet|2y=1855|2pp=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3p=}} | |||

| Reims opened its gates on 16 July 1429. Charles, Joan, and the army entered in the evening, and Charles's consecration took place the following morning.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2p=}} Joan was given a place of honor at the ceremony,{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2p=}} and announced that God's will had been fulfilled.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1p=|2a1=Gies|2y=1981|2p=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3p=}} | |||

| After the consecration, the royal court negotiated a truce of fifteen days with the Duke of Burgundy,{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} who promised he would try to arrange the transfer of Paris to the Armagnacs while continuing negotiations for a definitive peace. At the end of the truce, Burgundy reneged on his promise.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Lowell|1896|2pp=}} Joan and the Duke of Alençon favored a quick march on Paris,{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Richey|3y=2003|3p=}} but divisions in Charles's court and continued peace negotiations with Burgundy led to a slow advance.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Harrison|2014|2pp=|Lowell|1896|3pp=}} | |||

| As the Armagnac army approached Paris, many of the towns along the way surrendered without a fight.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=}} On 15 August, the English forces under the Duke of Bedford confronted the Armagnacs near ] in a fortified position that the Armagnac commanders thought was too strong to assault. Joan rode out in front of the English positions to try to provoke them to attack. They refused, resulting in a standoff.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2pp=}} The English retreated the following day.{{sfn|DeVries|1999|p=}} The Armagnacs continued their advance and launched an ] on 8 September.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=}} During the fighting, Joan was wounded in the leg by a crossbow bolt. She remained in a trench beneath the city walls until she was rescued after nightfall.{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} The Armagnacs had suffered 1,500 casualties.{{sfn|Barker|2009|p=}} The following morning, Charles ordered an end to the assault. Joan was displeased{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} and argued that the attack should be continued. She and Alençon had made fresh plans to attack Paris, but Charles dismantled a bridge approaching Paris that was necessary for the attack and the Armagnac army had to retreat.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=}} | |||

| After the defeat at Paris, Joan's role in the French court diminished. Her aggressive independence did not agree with the court's emphasis on finding a diplomatic solution with Burgundy, and her role in the defeat at Paris reduced the court's faith in her.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=|Harrison|2014|3p=}} Scholars at the ] argued that she failed to take Paris because her inspiration was not divine.{{sfn|Castor|2015|p=}} In September, Charles disbanded the army, and Joan was not allowed to work with the Duke of Alençon again.{{sfnm|1a1=Barker|1y=2009|1pp=|DeVries|1999|2p=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3pp=}} | |||

| ===Campaign against Perrinet Gressart=== | |||

| ], Nantes, France)|alt=A human figure on horseback, with the horse pointing left. The figure is wearing armor and carrying an orange banner. The horse is white and has red accessories.]] | |||

| In October, Joan was sent as part of a force to attack the territory of {{ill|Perrinet Gressart|fr}}, a mercenary who had served the Burgundians and English.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1pp=|DeVries|1999|2p=}} The army ], which fell after Joan encouraged a direct assault on 4 November. The army then tried unsuccessfully to take ] in November and December and had to abandon their artillery during the retreat.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} This defeat further diminished Joan's reputation.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|Castor|2015|2p=|Lowell|1896|3p=|Richey|2003|4p=}} | |||

| Joan returned to court at the end of December,{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} where she learned that she and her family had been ennobled by Charles as a reward for her services to him and the kingdom.{{sfnm|1a1=Lucie-Smith|1y=1976|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} Before the September attack on Paris, Charles had negotiated a four-month truce with the Burgundians,{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=|Lucie-Smith|1976|3p=}} which was extended until Easter 1430.{{sfnm|Lang|1909|1p=|Lowell|1896|2p=}} During this truce, the French court had no need for Joan.{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=|Harrison|2014|3pp=}} | |||

| ===Siege of Compiègne and capture=== | |||

| {{main|Siege of Compiègne}} | |||

| The Duke of Burgundy began to reclaim towns which had been ceded to him by treaty but had not submitted.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} Compiègne was one such town{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2pp=}} of many in areas which the Armagnacs had recaptured over the previous few months.{{sfn|DeVries|1999|p=}} Joan set out with a company of volunteers at the end of March 1430 to relieve the town, which was under siege.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=}} This expedition did not have the explicit permission of Charles, who was still observing the truce.{{sfnm|1a1=Lang|1y=1909|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2pp=|Vale|1974|p=}} Some writers suggest that Joan's expedition to Compiègne without documented permission from the court was a desperate and treasonable action,{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2p=}} but others have argued that she could not have launched the expedition without the financial support of the court.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Lightbody|1961|2p=}} | |||

| In April, Joan arrived at ], which had expelled its Burgundian garrison.{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} As Joan advanced, her force grew as other commanders joined her.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} Joan's troops advanced to ] and defeated an Anglo-Burgundian force commanded by the mercenary Franquet d'Arras who was captured. Typically, he would have been ransomed or exchanged by the capturing force, but Joan allowed the townspeople to execute him after a trial.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1p=|2a1=Gies|2y=1981|2pp=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3p=}} | |||

| ] ({{circa|1886–1890|lk=no}}, ], Paris)|alt=Joan in armor and surcoat being pulled off her horse by soldiers.]] | |||

| Joan reached Compiègne on 14 May.{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=}} After defensive forays against the Burgundian besiegers,{{sfnm|DeVries|1999|1p=}} she was forced to disband the majority of the army because it had become too difficult for the surrounding countryside to support.{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} Joan and about 400 of her remaining soldiers entered the town.{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} | |||

| On 23 May 1430, Joan accompanied an Armagnac force which ]d from Compiègne to attack the Burgundian camp at ], northeast of the town. The attack failed, and Joan was captured;{{sfnm|Barker|2009|1p=|DeVries|1999|2pp=|Harrison|2014|3pp=}} she agreed to surrender to a pro-Burgundian nobleman named Lyonnel de Wandomme, a member of ]'s contingent.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} who quickly moved her to his castle at ], near Noyes.{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} After her first attempt to escape, she was transferred to ] Castle. She made another escape attempt while there, jumping from a window of a tower and landing in a dry moat; she was injured but survived.{{sfnm|Castor|2015|1p=|Gies|1981|2p=|Warner|1981|3p=}} In November, she was moved to the Burgundian town of ].{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} | |||

| The English and Burgundians rejoiced that Joan had been removed as a military threat.{{sfn|Rankin|Quintal|1964|pp=}} The English negotiated with their Burgundian allies to pay Joan's ransom and transfer her to their custody. Bishop ] of ], a partisan supporter of the Duke of Burgundy and the English crown,{{sfnm|1a1=Champion|1y=1920|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2pp=}} played a prominent part in these negotiations,{{sfnm|Castor|2015|1pp=|Lucie-Smith|1976|2pp=}} which were completed in November.{{sfn|Taylor|2006|p=}} The final agreement called for the English to pay 10,000 ] to obtain her from Luxembourg.{{sfnm|1a1=DeVries|1y=1999|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Lucie-Smith|3y=1976|3p=}} After the English paid the ransom, they moved Joan to ], their main headquarters in France.{{sfnm|1a1=Castor|1y=2015|1p=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2pp=}} There is no evidence that Charles tried to save Joan once she was transferred to the English.{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1pp=|2a1=DeVries|2y=1999|2p=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3pp=|4a1=Vale|4y=1974|4pp=}} | |||

| ==Trials and execution== | |||

| === Trial === | === Trial === | ||

| {{Main|Trial of Joan of Arc}} | |||

| ] (1909–1910, ], Washington, D.C.)|alt=Joan of Arc facing left addressing assessors, scribes. She has soldiers behind her]] | |||

| ], Paris, 1835)]] | |||

| Joan was put on trial for ]{{sfnm|Hobbins|2005|1pp= |Sullivan|1999|2p=|Russell|1972|3p=|Taylor|2006|4p=}} in Rouen on 9 January 1431.{{sfn|Taylor|2006|p= }} She was accused of having ] by wearing men's clothes, of acting upon visions that were ]ic, and of refusing to submit her words and deeds to the church because she claimed she would be judged by God alone.{{sfn|Gies|1981|pp=|ps=; See {{harvnb|Hobbins|2005|pp=}} for a complete translation of the articles.}} Joan's captors downplayed the secular aspects of her trial by submitting her judgment to an ecclesiastical court, but the trial was politically motivated.{{sfnm|Peters|1989|1p=|Weiskopf|1996|2p=}} Joan testified that her visions had instructed her to defeat the English and crown Charles, and her success was argued to be evidence she was acting on behalf of God.{{sfn|Elliott|2002|pp=}} If unchallenged, her testimony would invalidate the English claim to the rule of France{{sfn|Hobbins|2005|p=}} and undermine the University of Paris,{{sfnm|1a1=Gies|1y=1981|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=}} which supported the dual monarchy ruled by an English king.{{sfnm|1a1=Pernoud|1a2=Clin|1y=1986|1p=|2a1=Hobbins|2a2=2005|2p=|3a1=Verger|3y=1972|3pp=}} | |||

| Joan of Arc's trial for heresy was politically motivated. The duke of Bedford claimed the throne of France for his nephew Henry VI. She had been responsible for the rival coronation so to condemn her was to undermine her king's legitimacy. Legal proceedings commenced on ] ] at ], the seat of the English occupation government.<ref>Judges' investigations January 9–March 26, ordinary trial March 26–May 24, recantation May 24, relapse trial May 28–29.</ref> The procedure was irregular on a number of points. | |||

| The verdict was a foregone conclusion.{{sfnm|Hobbins|2005|1p= |Kelly|1993|2pp=|Sullivan|2011|3p=}} Joan's guilt could be used to compromise Charles's claims to legitimacy by showing that he had been consecrated by the act of a heretic.{{sfnm|1a1=Hobbins|1y=2005|1pp=|2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|4a1=Taylor|4y=2006|4p=}} Cauchon served as the ] judge of the trial.{{sfn|Lightbody|1961|p=}} The English subsidized the trial,{{sfnm|Sullivan|1999|1p=|Gies|1981|2p= |Lightbody|1961|3pp=}} including payments to Cauchon{{sfnm|Newhall|1934|1p=|Warner|1981|2p=}} and Jean Le Maître,{{sfn|Pernoud|Clin|1986|p=}} who represented the Inquisitor of France.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Taylor|2006|2p=}} All but 8 of the 131 clergy who participated in the trial were French{{sfnm|Hobbins|2005|1p=|Taylor|2006|2p=}} and two thirds were associated with the University of Paris,{{sfnm|Harrison|2014|1p=|Hobbins|2005|2p=}} but most were pro-Burgundian and pro-English.{{sfnm|Pernoud|1962|1p=|Warner|1981|2p=}} | |||

| To summarize some major problems, the jurisdiction of judge Bishop Cauchon was a legal fiction.<ref>The retrial verdict later affirmed that Cauchon had no right to try the case. See also ''Joan of Arc: Her Story'', by Regine Pernoud and Marie-Veronique Clin, p. 108. The vice-inquisitor of France objected to the trial on jurisdictional grounds at its outset. </ref> He owed his appointment to his partisan support of the English government that financed the entire trial. Clerical notary Nicolas Bailly, commissioned to collect testimony against Joan of Arc, could find no adverse evidence.<ref>Nullification trial testimony of Father Nicholas Bailly. (Accessed 12 February 2006)</ref> Without such evidence the court lacked grounds to initiate a trial. Opening a trial anyway, the court also violated ecclesiastical law in denying her right to a legal advisor. | |||

| ] presiding at Joan of Arc's trial, unknown author (15th century, ])|alt=miniature of Pierre Couchon]] | |||

| The trial record demonstrates her remarkable intellect. The transcript's most famous exchange is an exercise in subtlety. "Asked if she knew she was in God's grace, she answered: 'If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me.'"<ref>Condemnation trial, p. 52. (Accessed 12 February 2006)</ref> The question is a scholarly trap. Church doctrine held that no one could be certain of being in God's grace. If she had answered yes, then she would have convicted herself of ]. If she had answered no, then she would have confessed her own guilt. Notary Boisguillaume would later testify that at the moment the court heard this reply, "Those who were interrogating her were stupefied."<ref>Pernoud and Clin, p. 112.</ref> In the twentieth century ] would find this dialogue so compelling that sections of his play ''Saint Joan'' are literal translations of the trial record.<ref>Shaw, ''].'' Penguin Classics; Reissue edition (2001). ISBN 0-14-043791-6</ref> | |||

| Cauchon attempted to follow correct inquisitorial procedure,{{sfnm|1a1=Hobbins|1y=2005|1p= |2a1=Pernoud|2a2=Clin|2y=1986|2p=|3a1=Sullivan|3y=2011|3p=|4a1=Taylor|4y=2006|4p=}} but the trial had many irregularities.{{sfnm|Gies|1981|1p=|Hobbins|2005|2p=|Peters|1989|3p=}} Joan should have been in the hands of the church during the trial and guarded by women,{{sfn|Taylor|2006|p=}} but instead was imprisoned by the English and guarded by male soldiers under the command of the Duke of Bedford.{{sfn|Gies|1981|p=}} Contrary to ], Cauchon had not established Joan's ] before proceeding with the trial.{{sfnm|Harrison|2014|1pp=|Kelly|1993|2pp=,|Taylor|2006|3pp=}} Joan was not read the charges against her until well after her interrogations began.{{sfn|Kelly|1993|p=}} The procedures were below inquisitorial standards,{{sfn|Peters|1989|p=}} subjecting Joan to lengthy interrogations{{sfn|Sullivan|1999|pp=}} without legal counsel.{{sfnm|Hobbins|2005|1p=|Taylor|2006|2pp=}} One of the trial clerics stepped down because he felt the testimony was coerced and its intention was to entrap Joan;{{sfnm|Frank|1997|1p=|Kelly|1993|2p=}} another challenged Cauchon's right to judge the trial and was jailed.{{sfnm|1a1=Frank|1y=1997|1p=|2a1=Gies|2y=1981|2pp=|3a1=Pernoud|3a2=Clin|3y=1986|3p=}} There is evidence that the trial records were falsified.{{sfnm|1a1=Hobbins|1y=2005|1p=|2a1=Rankin|2a2=Quintal|2y=1964|2p=}} | |||