| Revision as of 10:10, 12 October 2016 editGoldsmelter (talk | contribs)150 edits →Contacts with the Han Empire: bbc← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:36, 16 January 2025 edit undoKylieTastic (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers490,059 editsm Reverted 1 edit by 46.217.189.109 (talk) to last revision by EiszettTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| (563 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Hellenistic-era Greek kingdom (256–100 BCE)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Former Country | |||

| {{Redirect|Baktria|the historical region|Bactria}} | |||

| |native_name = | |||

| {{Infobox country | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Greco-Bactrian Kingdom | |||

| | native_name = Βασιλεία τῆς Βακτριανῆς<br /> ''{{transl|grc|Basileía tês Baktrianês}}'' | |||

| |common_name = Greco-Bactrian Kingdom | |||

| | conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Bactria | |||

| |continent = Asia | |||

| | |

| common_name = {{Plainlist| | ||

| * Greco-Bactrian Kingdom | |||

| |era = ] | |||

| * Bactrian Kingdom | |||

| |status = | |||

| * Greco-Bactria | |||

| |event_start = | |||

| * Graeco-Bactria | |||

| |year_start = 256 BC | |||

| }} | |||

| |date_start = | |||

| | era = ] | |||

| |event1 = | |||

| | status = | |||

| |date_event1 = | |||

| | |

| event_start = | ||

| | |

| year_start = 256 BC | ||

| | |

| date_start = | ||

| | |

| event1 = | ||

| | |

| date_event1 = | ||

| | |

| event_end = | ||

| | |

| year_end = c. 120 BC | ||

| | date_end = | |||

| |image_coat = | |||

| | p1 = Seleucid Empire | |||

| |image_map = Greco-BactrianKingdomMap.jpg | |||

| | s1 = Indo-Greek Kingdom | |||

| |image_map_caption = Approximate maximum extent of the '''Greco-Bactrian kingdom''' circa 180 BC, including the regions of ] and ] to the West, ]na and ] to the north, ] and ] to the south. | |||

| | s2 = Parthian Empire | |||

| |capital = ]<br>] | |||

| | s3 = Kushan Empire | |||

| |common_languages = ]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>] | |||

| | image_coat = Eucratide 1er - 20 statères.jpg | |||

| |religion = ]<br>]<br>] | |||

| | image_map = Greco-BactrianKingdomMap.jpg | |||

| |government_type = Monarchy | |||

| | |

| image_map_size = 280px | ||

| | image_map_caption = Approximate maximum extent of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom circa 170 BC, under the reign of Eucratides the Great, including the regions of ] and ] to the west, ]na and ] to the north, ] and ] to the south. | |||

| |year_leader1 = 256–240 BC | |||

| | |

| capital = {{Plainlist| | ||

| * ] | |||

| |year_leader2 = 145–130 BC | |||

| * ] | |||

| |stat_year1= 184 BC<ref name="Taagepera132">{{cite journal|date=1979|title=Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/1170959|journal=Social Science History|volume=3|issue=3/4|page=132|doi=10.2307/1170959|last1=Taagepera|first1=Rein|accessdate=16 September 2016}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| |stat_area1= 2500000 | |||

| | common_languages = {{Plainlist| | |||

| |title_leader = ] | |||

| * ] (official) | |||

| '''Today''' | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | religion = {{Plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | government_type = ] ] | |||

| | leader1 = ] (first) | |||

| | year_leader1 = 256–239 BC | |||

| | leader2 = ] (last) | |||

| | year_leader2 = 117–100 BC | |||

| | stat_year1 = 184 BC<ref name="Taagepera132">{{cite journal|date=1979|title=Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.|journal=Social Science History|volume=3|issue=3–4|page=132|doi=10.2307/1170959|last1=Taagepera|first1=Rein|jstor=1170959}}</ref> | |||

| | stat_area1 = 2500000 | |||

| | title_leader = ] | |||

| | symbol_type = ] wearing the Bactrian version of the ], shown on his gold 20-stater, the largest gold coin ever minted in the ancient world, c. 2nd century BC. | |||

| | coa_size = 113px | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Greco-Bactrian Kingdom''' ({{langx|el | |||

| {{Flag|Afghanistan}} | |||

| |Βασιλεία τῆς Βακτριανῆς|translit=Basileía tês Baktrianês|lit=Kingdom of Bactria}}) was a ] state of the ]<ref> ''Brewminate'', {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210924155537/https://brewminate.com/the-ancient-greco-bactrian-kingdom-and-hellenistic-afghanistan/|date=2021-09-24}} – ''Matthew A. McIntosh''</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Cribb|first=Joe|date=2005|title=The Greek Kingdom of Bactria, its coinage and its collapse|url=https://www.academia.edu/3026258|journal=Afghanistan Ancien Carrefour Entre Lʼest et Lʼouest|pages=1|via=Academia.edu}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Mairs|first=Rachel|title=Bactrian or Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom|url=https://www.academia.edu/23031604|journal=The Encyclopedia of Empire|year=2016|pages=1–4}}</ref> located in ]. The kingdom was founded by the ] satrap ] in about 256 BC, and continued to dominate Central Asia until its fall around 120 BC.{{Efn|Some cities were still controlled by Greek kings such as ] (90–70 BC) in what is today ].}} | |||

| At its peak, the kingdom consisted of present-day ], ], ], and ], and for a short time, small parts of ], ] and ]. An extension further east, with military campaigns and settlements, may have reached the borders of the ] in China by about 230 BC.<ref>Lucas, Christopoulos. Dionysian Rituals and the Golden Zeus of China. Sino-Platonic Papers 326.</ref><ref>Strabo, Geography 11.11.1</ref> | |||

| {{Flag|China}} | |||

| Although a Greek population was already present in Bactria by the 5th century BC, ] conquered the region by 327 BC<ref>{{Cite web|last=Crabben|first=Jan van der|title=Bactria|url=https://www.worldhistory.org/Bactria/|access-date=2024-10-11|website=World History Encyclopedia}}</ref> and founded many cities, most of them named ], and further settled with ] and other ]. After the death of Alexander, control of Bactria passed on to his general ].<ref>{{Cite web|date=2024-08-30|title=Bactria {{!}} Map, History, & Facts {{!}} Britannica|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Bactria|access-date=2024-10-11|website=Encyclopædia Britannica}}</ref> The fertility and the prosperity of the land by the early 3rd century BC led to the creation of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom by Diodotus as a successor state of the Seleucid empire. The Bactrian Greeks grew increasingly more powerful and invaded north-western ] between 190 and 180 BC under king ], the son of ]. This invasion led to the creation of the ], as a successor state of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, and was subsequently ruled by kings ] and ]. Historical records indicate that many rich and prosperous cities were present in the kingdom,<ref>Doumanis, Nicholas (16 December 2009). .{{Dead link|date=November 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} Palgrave Macmillan. p. 64. {{ISBN|978-1137013675}}.</ref><ref>] (11 December 2012). ({{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221119145809/https://books.google.com/books?id=yglkwD7pKV8C&dq=greco-bactrians+establish+indo-greeks&hl=nl&source=gbs_navlinks_s |date=2022-11-19 }}) Vol. '''1'''. I. B. Tauris, {{ISBN|978-1780760605}} p. 289.</ref><ref>Kaushik Roy (28 July 2015). ({{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221119145817/https://books.google.com/books?id=GpNECgAAQBAJ&pg=PT34&dq=indo-greek+kingdom+invaded+india&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAzgKahUKEwjYyoSrwvLIAhVCgA8KHQhgC-g#v=onepage&q=indo-greek%20kingdom%20invaded%20india&f=false |date=2022-11-19 }}). Routledge. {{ISBN|978-1317321279}}.</ref> but only a few such cities have been excavated, such as ] and ]. The city of Ai-Khanoum, in north-eastern Afghanistan, had all the hallmarks of a true Hellenistic city with a ], ] and some houses with colonnaded courtyards.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Boardman|first=John|title=The Greeks in Asia|publisher=Thames and Hudson|year=2015|isbn=978-0-500-77278-2|pages=166}}</ref> | |||

| {{Flag|India}} | |||

| The kingdom reached the height of its power under king ], who seems to have seized power through a ] around 171 BC and created his own dynasty. Eucratides also invaded India and successfully fought against the Indo-Greek kings. However, soon after this the kingdom began to decline. The ] and nomadic tribes such as ]s and ] became a major threat.<ref name="Strabo 11.11.2" /> Eucratides was killed by his own son in about 145 BC, which may have further destabilised the kingdom. ] was the last Greek king to rule in Bactria.<ref>Jakobsson, J. (2007). "The Greeks of Afghanistan Revisited". Nomismatika Khronika: p 17.</ref> | |||

| {{Flag|Iran}} | |||

| Even after the fall of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, their rich Hellenistic influence remained strong for many more centuries. The Yuezhi invaders settled in Bactria and became ]. They subsequently founded the ] around 30 AD, and adopted the ] to write their language and added Greek deities to their ]. The Greco-Bactrian city of Ai-Khanoum was at the doorstep of India and known for its high level of Hellenistic sophistication. Greek art travelled from Bactria with the Indo-Greeks and influenced Indian art, religion and culture, leading to new ] art called ]. | |||

| {{Flag|Kazakhstan}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Flag|Kyrgyzstan}} | |||

| === Origins === | |||

| {{Flag|Pakistan}} | |||

| ] was inhabited by Greek settlers since the time of ], when the majority of the population of ], in ], was deported to the region for refusing to surrender assassins.<ref>Herodotus, 4.200–204</ref> Greek influence increased under ], after the descendants of Greek priests who had once lived near ] (western ]) were forcibly relocated in Bactria,<ref>Strabo, 11.11.4</ref> and later on with other exiled Greeks, most of them prisoners of war. Greek communities and language were already common in the area by the time that ] conquered Bactria in 328 BC.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2020-12-23|title=Afghanistan: Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom|url=https://www.cemml.colostate.edu/cultural/09476/afgh02-06enl.html|access-date=2023-10-06|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201223080249/https://www.cemml.colostate.edu/cultural/09476/afgh02-06enl.html|archive-date=2020-12-23}}</ref> | |||

| ===Independence and Diodotid dynasty=== | |||

| {{Flag|Tajikistan}} | |||

| ] {{circa|245}} BC. The reverse shows ] standing, holding aegis and thunderbolt. The ] inscription reads: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΔΙΟΔΟΤΟΥ, ''Basileōs Diodotou'' – "(of) King Diodotus".|303x303px]] | |||

| Diodotus, the ] of Bactria (and probably the surrounding provinces) founded the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom when he seceded from the ] around 250 BC and became ], or king ] of Bactria. The preserved ancient sources (see below) are somewhat contradictory, and the exact date of Bactrian independence has not been settled. Somewhat simplified, there is a high chronology ({{circa|255}} BC) and a low chronology (c. 246 BC) for Diodotus' secession.<ref>J. D. Lerner (1999), ''The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau: The foundations of Arsacid Parthia and Graeco-Bactria'', Stuttgart</ref> The high chronology has the advantage of explaining why the Seleucid king ] issued very few coins in Bactria, as Diodotus would have become independent there early in Antiochus' reign.<ref>] (1999), ''Thundering Zeus'', Berkeley.</ref>{{page needed|date=December 2021}} On the other hand, the low chronology, from the mid-240s BC, has the advantage of connecting the secession of Diodotus I with the ], a catastrophic conflict for the Seleucid Empire. | |||

| {{Blockquote | Diodotus, the governor of the thousand cities of Bactria ({{langx|la|Theodotus, mille urbium Bactrianarum praefectus}}), defected and proclaimed himself king; all the other people of the Orient followed his example and seceded from the Macedonians.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/justin/texte41.html|title=Justin XLI, paragraph 4|access-date=2006-01-14|archive-date=2019-11-10|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191110100422/http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/justin/texte41.html|url-status=usurped}}</ref>}} | |||

| The new kingdom, highly urbanized and considered one of the richest of the Orient (''opulentissimum illud mille urbium Bactrianum imperium'' "The extremely prosperous Bactrian empire of the thousand cities", according to the historian ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/justin/texte41.html|title=Justin XLI, paragraph 1|access-date=2006-01-14|archive-date=2019-11-10|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191110100422/http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/justin/texte41.html|url-status=usurped}}</ref>), was to further grow in power and engage in territorial expansion to the east and the west: | |||

| {{Flag|Turkmenistan}} | |||

| ] capital, found at ], 2nd century BC.]] | |||

| {{Flag|Uzbekistan}} | |||

| {{Blockquote | The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of ], but also of India, as ] says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander… Their cities were ] (also called Zariaspa, through which flows a river bearing the same name and emptying into the ]), and Darapsa, and several others. Among these was ],<ref name= "Eucratidia">Possibly present day ]; Encyclopaedia Metropolitana: Or Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, Volume 23, ed. by Edward Smedley, Hugh James Rose, Henry John Rose, 1923, p. 260: "Eucratidia, named from its ruler, (Strabo, xi. p. 516.) was, according to Ptolemy, 2° North and 1° West of Bactra." As these coordinates are relative to, and close to, ], it is reasonable to disregard the imprecision in Ptolemy's coordinates and accept them without adjustment. If the coordinates for Bactra are taken to be {{coord|36|45|N|66|55|E}}, then the coordinates {{coord|38|45|N|65|55|E}} can be seen to be close to the modern day city of ].</ref> which was named after its ruler.<ref name="Strabo XI.XI.I">{{Cite web|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Strab.+11.11.1|title=Strabo XI.XI.I|access-date=2021-02-20|archive-date=2008-04-19|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080419032744/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Strab.+11.11.1|url-status=live}}</ref>}} | |||

| In 247 BC, the ] (the Greek rulers of Egypt following the death of ]) captured the Seleucid capital, ]. In the resulting power vacuum, ], the Seleucid satrap of Parthia, proclaimed independence from the Seleucids, declaring himself king. A decade later, he was ] by ] of Parthia, leading to the rise of a ]. This cut Bactria off from contact with the Greek world. Overland trade continued at a reduced rate, while sea trade between ] and Bactria developed. | |||

| }} | |||

| {{History of Afghanistan}} | |||

| The '''Greco-Bactrian Kingdom''' was – along with the ] – the easternmost part of the ] world, covering ] and ] in ] from 250 to 125 BC. It was centered on the north of present-day Afghanistan. The expansion of the Greco-Bactrians into present-day northern India and Pakistan from 180 BC established the Indo-Greek Kingdom, which was to last until around 10 AD.<ref>Doumanis, Nicholas. Palgrave Macmillan, 16 dec. 2009 ISBN 978-1137013675 p 64</ref><ref>]. Vol. '''1''' I.B.Tauris, 11 dec. 2012 ISBN 978-1780760605 p 289</ref><ref>Kaushik Roy. Routledge, 28 jul. 2015 ISBN 978-1317321279</ref> | |||

| ==Independence (around 250 BC)== | |||

| ] c. 245 BC. The ] inscription reads: ''ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΔΙΟΔΟΤΟΥ'' – "(of) King Diodotus".]] | |||

| Diodotus, the ] of Bactria (and probably the surrounding provinces) founded the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom when he seceded from the ] around 250 BC and became King ] of Bactria. The preserved ancient sources (see below) are somewhat contradictory, and the exact date of Bactrian independence has not been settled. Somewhat simplified, there is a high chronology (c. 255 BC) and a low chronology (c. 246 BC) for Diodotos’ secession.<ref>J. D. Lerner, The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau: the Foundations of Arsacid Parthia and Graeco-Bactria, (Stuttgart 1999)</ref> | |||

| The high chronology has the advantage of explaining why the Seleucid king ] issued very few coins in Bactria, as Diodotos would have become independent there early in Antiochus' reign.<ref>F. L. Holt, Thundering Zeus (Berkeley 1999)</ref> On the other hand, the low chronology, from the mid-240s BC, has the advantage of connecting the secession of Diodotus I with the ], a catastrophic conflict for the Seleucid Empire. | |||

| <!-- for this paragraph to appear properly indented to the right of the left adjusted image which normally precedes it, the following 12 extra tabs are necessary!; clearly a bug somewhere -:::::::::::: -->:Diodotus, the governor of the thousand cities of Bactria ({{lang-la|Theodotus, mille urbium Bactrianarum praefectus}}), defected and proclaimed himself king; all the other people of the Orient followed his example and seceded from the Macedonians. (], XLI,4)<ref></ref> | |||

| The new kingdom, highly urbanized and considered as one of the richest of the Orient (''opulentissimum illud mille urbium Bactrianum imperium'' "The extremely prosperous Bactrian empire of the thousand cities" Justin, XLI,1 <ref></ref>), was to further grow in power and engage into territorial expansion to the east and the west: | |||

| ] found in ], ancient Bactra.]] | |||

| :The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of ], but also of ], as ] says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander... Their cities were ] (also called Zariaspa, through which flows a river bearing the same name and emptying into the ]), and Darapsa, and several others. Among these was ],<ref name="Eucratidia">possibly present day ]; Encyclopaedia Metropolitana: Or Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, Volume 23, edited by Edward Smedley, Hugh James Rose, Henry John Rose, 1923, page 260, states: "Eucratidia, named from its ruler, (Strabo, xi. p. 516.) was, according to Ptolemy, 2° North and 1° West of Bactra." As these coordinates are relative to, and close to, ], it is reasonable to disregard the imprecision in Ptolemy's coordinates and accept them without adjustment. If the coordinates for Bactra are taken to be {{coord|36|45|N|66|55|E}}, then the coordinates {{coord|38|45|N|65|55|E}} can be seen to be close to the modern day city of ].</ref> which was named after its ruler. (Strabo, XI.XI.I)<ref name="Strabo XI.XI.I"></ref> | |||

| In 247 BC, the ] (the Greek rulers of Egypt following the death of ]) captured the Selucid capital, ]. In the resulting power vacuum, the ] of Parthia proclaimed independence from the Selucids, declaring himself king. A decade later, he was ] by ] of Parthia, leading to the rise of a ]. This cut Bactria off from contact with the Greek world. Overland trade continued at a reduced rate, while sea trade between ] and Bactria developed. | |||

| Diodotus was succeeded by his son ], who allied himself with the Parthian ] in his fight against ]: | Diodotus was succeeded by his son ], who allied himself with the Parthian ] in his fight against ]: | ||

| {{Blockquote | Soon after, relieved by the death of Diodotus, Arsaces made peace and concluded an alliance with his son, also by the name of Diodotus; some time later he fought against Seleucos who came to punish the rebels, and he prevailed: the Parthians celebrated this day as the one that marked the beginning of their freedom.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/justin/texte41.html|title=Justin XLI|access-date=2006-01-14|archive-date=2019-11-10|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191110100422/http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/justin/texte41.html|url-status=usurped}}</ref>}} | |||

| ===Euthydemid dynasty and Seleucid invasion=== | |||

| :Soon after, relieved by the death of Diodotus, Arsaces made peace and concluded an alliance with his son, also by the name of Diodotus; some time later he fought against Seleucos who came to punish the rebels, and he prevailed: the Parthians celebrated this day as the one that marked the beginning of their freedom. (], XLI,4)<ref></ref> | |||

| ], 230–200 BC. The reverse shows ] seated, holding club in right hand. The ] inscription reads: {{lang|grc-x-hellen|ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΕΥΘΥΔΗΜΟΥ}}, ''Basileōs Euthydēmou'' – "(of) King Euthydemus".]] | |||

| ], an Ionian Greek from ] according to ],<ref>{{cite book|section=Euthydemus|title=Encyclopaedia Iranica|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/euthydemus}}</ref><ref name="Polybius 11.34">{{Cite web|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+11.34|title=Polybius 11.34|access-date=2021-02-20|archive-date=2008-04-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080420074248/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+11.34|url-status=live}}</ref> and possibly satrap of ], overthrew the dynasty of Diodotus II around 230–220 BC and started his own dynasty. Euthydemus's control extended to Sogdiana, going beyond the city of ] founded by Alexander the Great in ]:{{citation needed|date=March 2021}} | |||

| <blockquote>And they also held Sogdiana, situated above Bactriana towards the east between the Oxus River, which forms the boundary between the Bactrians and the Sogdians, and the ] River. And the Iaxartes forms also the boundary between the Sogdians and the nomads.<ref name="Strabo 11.11.2">{{Cite web|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Strab.+11.11.1|title=Strabo 11.11.2|access-date=2021-02-20|archive-date=2008-04-19|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080419032744/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Strab.+11.11.1|url-status=live}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ==Overthrow of Diodotus II (230 BC)== | |||

| ] | |||

| Euthydemus was attacked by the Seleucid ruler ] around 210 BC. Although he commanded 10,000 horsemen, Euthydemus initially lost a ] on the ]<ref name= "Polybius 10.49, Battle of the Arius">{{Cite web|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+10.49|title=Polybius 10.49, Battle of the Arius|access-date=2021-02-20|archive-date=2008-03-19|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080319072118/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+10.49|url-status=live}}</ref> and had to retreat. He then successfully ] in the fortified city of ], before Antiochus finally decided to recognize the new ruler, and to offer one of his daughters to Euthydemus's son ] around 206 BC.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+11.34|title=Polybius 11.34 Siege of Bactra|access-date=2021-02-20|archive-date=2008-04-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080420074248/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plb.+11.34|url-status=live}}</ref> Classical accounts also relate that Euthydemus negotiated peace with Antiochus III by suggesting that he deserved credit for overthrowing the original rebel Diodotus and that he was protecting Central Asia from nomadic invasions thanks to his defensive efforts: | |||

| {{Blockquote | ... for if he did not yield to this demand, neither of them would be safe: Seeing that great hordes of Nomads were close at hand, who were a danger to both; and that if they admitted them into the country, it would certainly be utterly barbarised.<ref name="Polybius 11.34"/>}} | |||

| In an inscription found in the ] area of ], in eastern Greco-Bactria, and dated to 200–195 BC,<ref name="SW">Shane Wallace {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200112215954/https://www.academia.edu/25638818 |date=2020-01-12 }} p.206</ref> a Greek by the name of Heliodotus, dedicating a fire altar to ], mentions Euthydemus as the greatest of all kings, and his son ] as "Demetrios Kallinikos", meaning "Demetrius the Glorious Conqueror":<ref>], {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308060357/https://www.academia.edu/22821570/Some_observations_on_the_chronology_of_the_early_Kushans |date=2021-03-08 }}, p.48</ref><ref name="SW"/> | |||

| ], a ] Greek according to ]<ref name="Polybius 11.34"></ref> and possibly satrap of ], overthrew the dynasty of Diodotus I around 230-220 BC and started his own dynasty. Euthydemus's control extended to Sogdiana, going beyond the city of ] founded by Alexander the Great in ]: | |||

| <blockquote><poem> | |||

| :And they also held Sogdiana, situated above Bactriana towards the east between the Oxus River, which forms the boundary between the Bactrians and the Sogdians, and the ] River. And the Iaxartes forms also the boundary between the Sogdians and the nomads. (Strabo XI.11.2)<ref name="Strabo 11.11.2"></ref> | |||

| {{lang|grc-x-hellen|τόνδε σοι βωμὸν θυώδη, πρέσβα κυδίστη θεῶν Ἑστία, Διὸς κ(α)τ᾽ ἄλσος καλλίδενδρον ἔκτισεν καὶ κλυταῖς ἤσκησε λοιβαῖς ἐμπύροις Ἡλιόδοτος ὄφρα τὸμ πάντων μέγιστον Εὐθύδημον βασιλέων τοῦ τε παῖδα καλλίνικον ἐκπρεπῆ Δημήτριον πρευμενὴς σώιζηις ἐκηδεῖ(ς) σὺν τύχαι θεόφρον.}} | |||

| ''tónde soi bōmòn thuṓdē, présba kydístē theôn Hestía, Diòs kat' álsos kallídendron éktisen kaì klytaîs ḗskēse loibaîs empýrois Hēliodótos óphra tòm pántōn mégiston Euthýdēmon basiléōn toû te paîda kallínikon ekprepê Dēmḗtrion preumenḕs sṓizēis ekēdeîs sỳn Týchai theόphroni.'' | |||

| ==Seleucid invasion== | |||

| ] king ] 230–200 BC. The ] inscription reads: ''ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΕΥΘΥΔΗΜΟΥ'' – "(of) King Euthydemus".]] | |||

| "Heliodotus dedicated this fragrant altar for ], venerable goddess, illustrious amongst all, in the grove of ], with beautiful trees; he made libations and sacrifices so that the greatest of all kings ], as well as his son, the glorious, victorious and remarkable ], be preserved of all pains, with the help of ] with divine thoughts."<ref>Shane Wallace {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200112215954/https://www.academia.edu/25638818 |date=2020-01-12 }} p. 211</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.attalus.org/docs/seg/s54_1569.html|title=Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum: 54.1569|access-date=2019-11-15|archive-date=2021-02-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210207033247/http://www.attalus.org/docs/seg/s54_1569.html|url-status=live}}</ref></poem></blockquote> | |||

| ] was attacked by the Seleucid ruler ] around 210 BC. Although he commanded 10,000 horsemen, Euthydemus initially lost a ] on the ]<ref name="Polybius 10.49, Battle of the Arius"></ref> and had to retreat. He then successfully ] in the fortified city of ] (modern ]), before Antiochus finally decided to recognize the new ruler, and to offer one of his daughters to Euthydemus's son ] around 206 BC.<ref></ref> Classical accounts also relate that Euthydemus negotiated peace with Antiochus III by suggesting that he deserved credit for overthrowing the original rebel Diodotus, and that he was protecting Central Asia from nomadic invasions thanks to his defensive efforts: | |||

| : ...for if he did not yield to this demand, neither of them would be safe: seeing that great hordes of Nomads were close at hand, who were a danger to both; and that if they admitted them into the country, it would certainly be utterly barbarised. (], 11.34)<ref name="Polybius 11.34"/> | |||

| ==Geographic expansion== | |||

| Following the departure of the Seleucid army, the Bactrian kingdom seems to have expanded. In the west, areas in north-eastern ] may have been absorbed, possibly as far as into ], whose ruler had been defeated by ]. These territories possibly are identical with the Bactrian satrapies of ] and ]. | Following the departure of the Seleucid army, the Bactrian kingdom seems to have expanded. In the west, areas in north-eastern ] may have been absorbed, possibly as far as into ], whose ruler had been defeated by ]. These territories possibly are identical with the Bactrian satrapies of ] and ]. | ||

| ===Expansion into the Indian subcontinent (around 180 BC)=== | |||

| ], ] ] Museum (drawing).]] | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | perrow = 2 | |||

| ===Contacts with the ]=== | |||

| | total_width = 210 | |||

| ], woollen wall hanging, 3rd–2nd century BC, Sampul, ] ] Museum.]] | |||

| | caption_align = left | |||

| | align = left | |||

| ]/] bronze mirror with glass inlays, perhaps incorporated Greco-Roman artistic patterns (rosette flowers, geometric lines, and glass inlays). ].]] | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | header = | |||

| ] vase with glass inlays, 4th–3rd century BC, ].]] | |||

| | image1 = Demetrius I of Bactria.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Silver coin of king ] (reigned c. 200–180 BC), wearing an elephant scalp, symbol of his conquests in northwest ]. | |||

| To the north, Euthydemus also ruled ] and ], and there are indications that from ] the Greco-Bactrians may have led expeditions as far as ] and ] in ], leading to the first known contacts between China and the West around 220 BC. The Greek historian ] too writes that: "they extended their empire even as far as the ] (Chinese) and the ]". (], XI.XI.I).<ref name="Strabo XI.XI.I"/> | |||

| | footer = | |||

| }} | |||

| Several statuettes and representations of Greek soldiers have been found north of the ], on the doorstep to China, and are today on display in the ] museum at ] (Boardman).<ref>On the image of the Greek kneeling warrior: "A bronze figurine of a kneeling warrior, not Greek work, but wearing a version of the Greek Phrygian helmet.. From a burial, said to be of the 4th century BC, just north of the Tien Shan range". Ürümqi Xinjiang Museum. (Boardman "The diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity")</ref> Greek influences on Chinese art have also been suggested (], ]). Designs with ] flowers, geometric lines, and glass inlays, suggestive of Hellenistic influences,<ref>Notice of the British Museum on the Zhou vase (2005, attached image): "Red earthenware bowl, decorated with a slip and inlaid with glass paste. Eastern Zhou period, 4th–3rd century BC. This bowl was probably intended to copy a more precious and possibly foreign vessel in bronze or even silver. Glass was little used in China. Its popularity at the end of the Eastern Zhou period was probably due to foreign influence."</ref> can be found on some early ] bronze mirrors.<ref>"The things which China received from the Graeco-Iranian world-the pomegranate and other "Chang-Kien" plants, the heavy equipment of the cataphract, the traces of Greeks influence on Han art (such as) the famous white bronze mirror of the Han period with Graeco-Bactrian designs (...) in the Victoria and Albert Museum" (Tarn, ''The Greeks in Bactria and India'', pp. 363-364)</ref> | |||

| ], the son of Euthydemus, started an invasion of the subcontinent before 180 BC, and a few years after the ] had been overthrown by the ]. Historians differ on the motivations behind the invasion. Some historians suggest that the invasion of the subcontinent was intended to show their support for the ], and to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the ] as alleged by Buddhist scriptures (Tarn). Other historians have argued however that the accounts of these persecutions have been exaggerated (], ]). | |||

| Recent excavations at the burial site of ]'s first Emperor ], dating back to the 3rd century BCE, also suggest Greek influence in the artworks found there, including in the manufacture of the famous ]. It is also suggested that Greek artists may have come to China at that time to train local artisans in making sculptures <ref></ref><ref></ref> | |||

| ] also suggest that some technology exchanges may have occurred on these occasions: the Greco-Bactrians were the first in the world to issue ] (75/25 ratio) coins,<ref></ref> an alloy technology only known by the Chinese at the time under the name "White copper" (some weapons from the ] were in copper-nickel alloy).<ref> </ref> The practice of exporting Chinese metals, in particular iron, for trade is attested around that period. Kings Euthydemus, Euthydemus II, ] and ] made these coin issues around 170 BC and it has alternatively been suggested that a nickeliferous copper ore was the source from mines at ].<ref>A.A. Moss pp317-318 ''Numismatic Chronicle'' 1950</ref> Copper-nickel would not be used again in coinage until the 19th century. | |||

| The presence of Chinese people in India from ancient times is also suggested by the accounts of the "]" in the '']'' and the '']''. The ] explorer and ambassador ] visited Bactria in 126 BC, and reported the presence of Chinese products in the Bactrian markets: | |||

| :When I was in Bactria (])", Zhang Qian reported, "I saw bamboo canes from Qiong and cloth made in the province of Shu (territories of southwestern China). When I asked the people how they had gotten such articles, they replied, "Our merchants go buy them in the markets of Shendu (India). ('']'' 123, ], trans. Burton Watson). | |||

| Upon his return, Zhang Qian informed the Chinese emperor Han ] of the level of sophistication of the urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia, who became interested in developing commercial relationship with them: | |||

| :The Son of Heaven on hearing all this reasoned thus: ] (]) and the possessions of ] (]) and ] (Anxi) are large countries, full of rare things, with a population living in fixed abodes and given to occupations somewhat identical with those of the Chinese people, and placing great value on the rich produce of China. ('']'', Former Han History). | |||

| A number of Chinese envoys were then sent to Central Asia, triggering the development of the ] from the end of the 2nd century BC.<ref></ref> | |||

| ===Contacts with the Indian Subcontinent (250–180)=== | |||

| The Indian emperor ], founder of the ], had re-conquered the northwestern subcontinent upon the death of ] around 322 BC. However, contacts were kept with his Greek neighbours in the ], a dynastic alliance or the recognition of intermarriage between Greeks and ancient ] were established (described as an agreement on ] in Ancient sources), and several Greeks, such as the historian ], resided at the Mauryan court. Subsequently, each Mauryan emperor had a Greek ambassador at his court. | |||

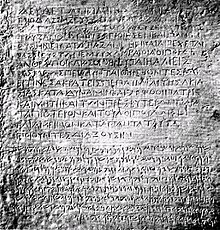

| ] (in ] and ]), found in ]. Circa 250 BC, ] Museum.]] | |||

| Chandragupta's grandson ] converted to the Buddhist faith and became a great proselytizer in the line of the traditional Pali canon of ] Buddhism, directing his efforts towards the Indo-Iranic and the Hellenistic worlds from around 250 BC. According to the ], set in stone, some of them written in Greek, he sent Buddhist emissaries to the Greek lands in Asia and as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts name each of the rulers of the ] world at the time. | |||

| :The conquest by ] has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred ]s (4,000 miles) away, where the Greek king ] rules, beyond there where the four kings named ], ], ] and ] rule, likewise in the south among the ]s, the ]s, and as far as ]. (], 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika). | |||

| Some of the Greek populations that had remained in northwestern India apparently converted to Buddhism: | |||

| :Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the ], the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the ] and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in ]. (], 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika). | |||

| Furthermore, according to ] sources, some of Ashoka's emissaries were Greek Buddhist monks, indicating close religious exchanges between the two cultures: | |||

| <!-- Deleted image removed: ] and ] issued bilingual coins in the Indian square standard, with depictions of the Buddhist lion, the ] inscription reads: ''ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ (ΠΑΝ)ΤΑΛΕΟΝΤΟΣ'' – "(of) King (Pan)taleon", the other side represents a ].]] --> | |||

| :When the thera (elder) Moggaliputta, the illuminator of the religion of the Conqueror (Ashoka), had brought the (third) council to an end… he sent forth theras, one here and one there: …and to Aparantaka (the "Western countries" corresponding to ] and ]) he sent the Greek (]) named ]... and the thera Maharakkhita he sent into the country of the Yona. (] XII). | |||

| Greco-Bactrians probably received these Buddhist emissaries (At least Maharakkhita, lit. "The Great Saved One", who was "sent to the country of the Yona") and somehow tolerated the Buddhist faith, although little proof remains. In the 2nd century AD, the Christian dogmatist ] recognized the existence of Buddhist ]s among the Bactrians ("Bactrians" meaning "Oriental Greeks" in that period), and even their influence on Greek thought: | |||

| :Thus philosophy, a thing of the highest utility, flourished in antiquity among the barbarians, shedding its light over the nations. And afterwards it came to ]. First in its ranks were the prophets of the ]; and the ]ns among the ]; and the ] among the ]; and the ''']s''' among the ] ("Σαρμαναίοι Βάκτρων"); and the philosophers of the ]; and the ] of the ], who foretold the Saviour's birth, and came into the land of ] guided by a star. The Indian ]s are also in the number, and the other barbarian philosophers. And of these there are two classes, some of them called ''']s''' ("Σαρμάναι"), and others ] ("Βραφμαναι"). Clement of Alexandria "The Stromata, or Miscellanies" Book I, Chapter XV.<ref></ref> | |||

| ===Expansion into the Indian subcontinent (after 180 BC)=== | |||

| ] (reigned c. 200–180 BC), wearing an elephant scalp, symbol of his conquests in ].]] | |||

| {{Main|Indo-Greek Kingdom}} | |||

| ], the son of Euthydemus, started an invasion of the subcontinent from 180 BC, a few years after the ] had been overthrown by the ]. Historians differ on the motivations behind the invasion. Some historians suggest that the invasion of the subcontinent was intended to show their support for the ], and to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the ] as alleged by Buddhist scriptures (Tarn). Other historians have argued however that the accounts of these persecutions have been exaggerated (], ]). | |||

| Demetrius may have been as far as the imperial capital ] in today's eastern India (today ]). However, these campaigns are typically attributed to Menander. The invasion was completed by 175 BC. This established in the northwestern Indian Subcontinent what is called the ], which lasted for almost two centuries until around |

Demetrius may have been as far as the imperial capital ] in today's eastern India (today ]). However, these campaigns are typically attributed to ]. His conquests were mentioned along with that of Menander by the historian Strabo, as having "subdued more tribes than Alexander." The invasion was completed by 175 BC. This established in the northwestern Indian Subcontinent what is called the ], which lasted for almost two centuries until around 10 AD. The Buddhist faith flourished under the Indo-Greek kings, especially Menander who was arguably the most powerful of them all. It was also a period of great cultural syncretism, exemplified by the development of ] in the region of ]. | ||

| It was also a period of great cultural syncretism, exemplified by the development of ]. | |||

| <!-- | <!-- | ||

| The Indo-Greek Kingdom or Graeco-Indian Kingdom covered various parts of the northwest regions of the Indian subcontinent during the last two centuries BC, and was ruled by more than 30 Hellenistic kings, often in conflict with each other. The kingdom was founded when the Graeco-Bactrian king Demetrius invaded India early in the 2nd century BC; in this context the boundary of "India" is the Hindu Kush. The Greeks in India were eventually divided from the Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom centered in Bactria (now the border between Afghanistan and Uzbekistan). | The Indo-Greek Kingdom or Graeco-Indian Kingdom covered various parts of the northwest regions of the Indian subcontinent during the last two centuries BC, and was ruled by more than 30 Hellenistic kings, often in conflict with each other. The kingdom was founded when the Graeco-Bactrian king Demetrius invaded India early in the 2nd century BC; in this context the boundary of "India" is the Hindu Kush. The Greeks in India were eventually divided from the Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom centered in Bactria (now the border between Afghanistan and Uzbekistan). | ||

| Line 163: | Line 132: | ||

| The Indo-Greeks ultimately disappeared as a political entity around AD 10 following the invasions of the Indo-Scythians, although pockets of Greek populations probably remained for several centuries longer under the subsequent rule of the Indo-Parthians and Kushans. | The Indo-Greeks ultimately disappeared as a political entity around AD 10 following the invasions of the Indo-Scythians, although pockets of Greek populations probably remained for several centuries longer under the subsequent rule of the Indo-Parthians and Kushans. | ||

| Nature and quality of the sources | ===Nature and quality of the sources=== | ||

| Some narrative history has survived for most of the Hellenistic world, at least of the kings and the wars; this is lacking for India. The main Greco-Roman source on the Indo-Greeks is Justin, who wrote an anthology drawn from the Roman historian Pompeius Trogus, who in turn wrote, from Greek sources, at the time of Augustus Caesar. Justin tells the parts of Trogus' history he finds particularly interesting at some length; he connects them by short and simplified summaries of the rest of the material. In the process he has left 85% to 90% of Trogus out; and his summaries are held together by phrases like "meanwhile" (eodem tempore) and "thereafter" (deinde), which he uses very loosely. Where Justin covers periods for which there are other and better sources, he has occasionally made provable mistakes. As Develin, the recent annotator of Justin, and Tarn both point out, Justin is not trying to write history in our sense of the word; he is collecting instructive moral anecdotes. Justin does find the customs and growth of the Parthians, which were covered in Trogus' 41st book, quite interesting, and discusses them at length; in the process, he mentions four of the kings of Bactria and one Greek king of India. | Some narrative history has survived for most of the Hellenistic world, at least of the kings and the wars; this is lacking for India. The main Greco-Roman source on the Indo-Greeks is Justin, who wrote an anthology drawn from the Roman historian Pompeius Trogus, who in turn wrote, from Greek sources, at the time of Augustus Caesar. Justin tells the parts of Trogus' history he finds particularly interesting at some length; he connects them by short and simplified summaries of the rest of the material. In the process he has left 85% to 90% of Trogus out; and his summaries are held together by phrases like "meanwhile" (eodem tempore) and "thereafter" (deinde), which he uses very loosely. Where Justin covers periods for which there are other and better sources, he has occasionally made provable mistakes. As Develin, the recent annotator of Justin, and Tarn both point out, Justin is not trying to write history in our sense of the word; he is collecting instructive moral anecdotes. Justin does find the customs and growth of the Parthians, which were covered in Trogus' 41st book, quite interesting, and discusses them at length; in the process, he mentions four of the kings of Bactria and one Greek king of India. | ||

| Line 177: | Line 146: | ||

| Hoards which contain many coins of the same king come from his realm. | Hoards which contain many coins of the same king come from his realm. | ||

| Kings who use the same iconography are friendly, and may well be from the same family, | Kings who use the same iconography are friendly, and may well be from the same family, | ||

| If a king overstrikes another king's coins, this is an important evidence to show that the overstriker reigned after the overstruck. Overstrikes may indicate that the two kings were enemies. |

If a king overstrikes another king's coins, this is an important evidence to show that the overstriker reigned after the overstruck. Overstrikes may indicate that the two kings were enemies. | ||

| Indo-Greek coins, like other Hellenistic coins, have monograms in addition to their inscriptions. These are generally held to indicate a mint official; therefore, if two kings issue coins with the same monogram, they reigned in the same area, and if not immediately following one another, have no long interval between them. | Indo-Greek coins, like other Hellenistic coins, have monograms in addition to their inscriptions. These are generally held to indicate a mint official; therefore, if two kings issue coins with the same monogram, they reigned in the same area, and if not immediately following one another, have no long interval between them. | ||

| All of these arguments are arguments of probability, and have exceptions; one of Menander's coins was found in Wales. | All of these arguments are arguments of probability, and have exceptions; one of Menander's coins was found in Wales. | ||

| Line 183: | Line 153: | ||

| The exact time and progression of the Bactrian expansion into India is difficult to ascertain, but ancient authors name Demetrius, Apollodotus, and Menander as conquerors. | The exact time and progression of the Bactrian expansion into India is difficult to ascertain, but ancient authors name Demetrius, Apollodotus, and Menander as conquerors. | ||

| ;Demetrius | |||

| Demetrius I was the son of Euthydemus I of Bactria; there is an inscription from his father's reign already officially hailing him as victorious. He also has one of the few absolute dates in Indo-Greek history: after his father held off Antiochus III for two years, 208–6 BC, the peace treaty included the offer of a marriage between Demetrius and Antiochus' daughter. Coins of Demetrius I have been found in Arachosia and in the Kabul Valley; the latter would be the first entry of the Greeks into India, as they defined it. There is also literary evidence for a campaign eastward against the Seres and the Phryni; but the order and dating of these conquests is uncertain. Demetrius I seems to have conquered the Kabul valley, Arachosia and perhaps Gandhara; he struck no Indian coins, so either his conquests did not penetrate that far into India or he died before he could consolidate them. On his coins, Demetrius I always carries the elephant-helmet worn by Alexander, which seems to be a token of his Indian conquests. Bopearachchi believes that Demetrius received the title of "King of India" following his victories south of the Hindu Kush. He was also given, though perhaps only posthumously, the title ανικητος ("Anicetos", lit. Invincible) a cult title of Heracles, which Alexander had assumed; the later Indo-Greek kings Lysias, Philoxenus, and Artemidorus also took it. Finally, Demetrius may have been the founder of a newly discovered Greek Era, starting in 186/5 BC. | Demetrius I was the son of Euthydemus I of Bactria; there is an inscription from his father's reign already officially hailing him as victorious. He also has one of the few absolute dates in Indo-Greek history: after his father held off Antiochus III for two years, 208–6 BC, the peace treaty included the offer of a marriage between Demetrius and Antiochus' daughter. Coins of Demetrius I have been found in Arachosia and in the Kabul Valley; the latter would be the first entry of the Greeks into India, as they defined it. There is also literary evidence for a campaign eastward against the Seres and the Phryni; but the order and dating of these conquests is uncertain. Demetrius I seems to have conquered the Kabul valley, Arachosia and perhaps Gandhara; he struck no Indian coins, so either his conquests did not penetrate that far into India or he died before he could consolidate them. On his coins, Demetrius I always carries the elephant-helmet worn by Alexander, which seems to be a token of his Indian conquests. Bopearachchi believes that Demetrius received the title of "King of India" following his victories south of the Hindu Kush. He was also given, though perhaps only posthumously, the title ανικητος ("Anicetos", lit. Invincible) a cult title of Heracles, which Alexander had assumed; the later Indo-Greek kings Lysias, Philoxenus, and Artemidorus also took it. Finally, Demetrius may have been the founder of a newly discovered Greek Era, starting in 186/5 BC. | ||

| ;After Demetrius I | |||

| After the death of Demetrius, the Bactrian kings Pantaleon and Agathocles struck the first bilingual coins with Indian inscriptions found as far east as Taxila so in their time (c. 185–170 BC) the Bactrian kingdom seems to have included Gandhara. Several Bactrian kings followed after Demetrius' death, and it seems likely that the civil wars between them made it possible for Apollodotus I (from c. |

After the death of Demetrius, the Bactrian kings Pantaleon and Agathocles struck the first bilingual coins with Indian inscriptions found as far east as Taxila so in their time (c. 185–170 BC) the Bactrian kingdom seems to have included Gandhara. Several Bactrian kings followed after Demetrius' death, and it seems likely that the civil wars between them made it possible for Apollodotus I (from c. 180–175 BC) to make himself independent as the first proper Indo-Greek king (who did not rule from Bactria). Large numbers of his coins have been found in India, and he seems to have reigned in Gandhara as well as western Punjab. Apollodotus I was succeeded by or ruled alongside Antimachus II, likely the son of the Bactrian king Antimachus I. | ||

| The next important Indo-Greek king was Menander (from c. |

The next important Indo-Greek king was Menander (from c. 165–155 BC) whose coins are frequently found even in eastern Punjab. Menander seems to have begun a second wave of conquests, and since he already ruled in India, it seems likely that the easternmost conquests were made by him. | ||

| According to Apollodorus of Artemita, quoted by Strabo, the Indo-Greek territory for a while included the Indian coastal provinces of Sindh and possibly Gujarat. With archaeological methods, the Indo-Greek territory can however only be confirmed from the Kabul Valley to the eastern Punjab, so Greek presence outside was probably short-lived or less significant. | According to Apollodorus of Artemita, quoted by Strabo, the Indo-Greek territory for a while included the Indian coastal provinces of Sindh and possibly Gujarat. With archaeological methods, the Indo-Greek territory can however only be confirmed from the Kabul Valley to the eastern Punjab, so Greek presence outside was probably short-lived or less significant. | ||

| Line 207: | Line 177: | ||

| To the south, the Greeks may have occupied the areas of the Sindh and Gujarat, including the strategic harbour of Barygaza (Bharuch), conquests also attested by coins dating from the Indo-Greek ruler Apollodotus I and by several ancient writers (Strabo 11; Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Chap. 41/47): | To the south, the Greeks may have occupied the areas of the Sindh and Gujarat, including the strategic harbour of Barygaza (Bharuch), conquests also attested by coins dating from the Indo-Greek ruler Apollodotus I and by several ancient writers (Strabo 11; Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Chap. 41/47): | ||

| "The Greeks... took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis." | "The Greeks ... took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis." | ||

| —Strabo 11.11.1 | —Strabo 11.11.1 | ||

| Narain however dismisses the account of the Periplus as "just a sailor's story", and holds that coin finds are not necessarily indicators of occupation. Coin hoards suggest that in Central India, the area of Malwa may also have been conquered. | Narain however dismisses the account of the Periplus as "just a sailor's story", and holds that coin finds are not necessarily indicators of occupation. Coin hoards suggest that in Central India, the area of Malwa may also have been conquered. | ||

| Line 225: | Line 195: | ||

| Therefore, Menander remains the likeliest candidate for any advance east of Punjab. | Therefore, Menander remains the likeliest candidate for any advance east of Punjab. | ||

| ;Consolidation | |||

| The important Bactrian king Eucratides seems to have attacked the Indo-Greek kingdom during the mid 2nd century BC. A Demetrius, called "King of the Indians", seems to have confronted Eucratides in a four month siege, reported by Justin, but he ultimately lost. | The important Bactrian king Eucratides seems to have attacked the Indo-Greek kingdom during the mid 2nd century BC. A Demetrius, called "King of the Indians", seems to have confronted Eucratides in a four month siege, reported by Justin, but he ultimately lost. | ||

| Line 233: | Line 203: | ||

| Menander is considered to have been probably the most successful Indo-Greek king, and the conqueror of the largest territory. The finds of his coins are the most numerous and the most widespread of all the Indo-Greek kings. Menander is also remembered in Buddhist literature, where he called Milinda, and is described in the Milinda Panha as a convert to Buddhism: he became an arhat whose relics were enshrined in a manner reminiscent of the Buddha. He also introduced a new coin type, with Athena Alkidemos ("Protector of the people") on the reverse, which was adopted by most of his successors in the East. | Menander is considered to have been probably the most successful Indo-Greek king, and the conqueror of the largest territory. The finds of his coins are the most numerous and the most widespread of all the Indo-Greek kings. Menander is also remembered in Buddhist literature, where he called Milinda, and is described in the Milinda Panha as a convert to Buddhism: he became an arhat whose relics were enshrined in a manner reminiscent of the Buddha. He also introduced a new coin type, with Athena Alkidemos ("Protector of the people") on the reverse, which was adopted by most of his successors in the East. | ||

| ;Fall of Bactria and death of Menander | |||

| Fall of Bactria and death of MenanderFrom the mid-2nd century BC, the Scythians and then the Yuezhi, following a long migration from the border of China, started to invade Bactria from the north. Around 130 BC the last Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles was probably killed during the invasion and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom proper ceased to exist. The Parthians also probably played a role in the downfall of the Bactrian kingdom | |||

| From the mid-2nd century BC, the Scythians and then the Yuezhi, following a long migration from the border of China, started to invade Bactria from the north. Around 130 BC the last Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles was probably killed during the invasion and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom proper ceased to exist. The Parthians also probably played a role in the downfall of the Bactrian kingdom. | |||

| The Indo-Greek states, shielded by the Hindu Kush range, were saved from the invasions, but the civil wars which had weakened the Greeks continued. Menander I died around the same time, and even though the king himself seems to have been popular among his subjects, his dynasty was at least partially dethroned (see discussion under Menander I). Probable members of the dynasty of Menander include the ruling queen Agathokleia, her son Strato I, and Nicias, though it is uncertain whether they ruled directly after Menander. Other kings emerged, usually in the western part of the Indo-Greek realm, such as Zoilos I, Lysias, Antialcidas and Philoxenos. These rulers may have been relatives of either the Eucratid or the Euthydemid dynasties. The names of later kings were often new (members of Hellenistic dynasties usually inherited family names) but old reverses and titles were frequently repeated by the later rulers. | The Indo-Greek states, shielded by the Hindu Kush range, were saved from the invasions, but the civil wars which had weakened the Greeks continued. Menander I died around the same time, and even though the king himself seems to have been popular among his subjects, his dynasty was at least partially dethroned (see discussion under Menander I). Probable members of the dynasty of Menander include the ruling queen Agathokleia, her son Strato I, and Nicias, though it is uncertain whether they ruled directly after Menander. Other kings emerged, usually in the western part of the Indo-Greek realm, such as Zoilos I, Lysias, Antialcidas and Philoxenos. These rulers may have been relatives of either the Eucratid or the Euthydemid dynasties. The names of later kings were often new (members of Hellenistic dynasties usually inherited family names) but old reverses and titles were frequently repeated by the later rulers. | ||

| Line 240: | Line 212: | ||

| There are however no historical recordings of events in the Indo-Greek kingdom after Menander's death around 130 BC, since the Indo-Greeks had now become very isolated from the rest of the Graeco-Roman world. The later history of the Indo-Greek states, which lasted to around the shift BC/AD, is reconstructed almost entirely from archaeological and numismatical analyses. | There are however no historical recordings of events in the Indo-Greek kingdom after Menander's death around 130 BC, since the Indo-Greeks had now become very isolated from the rest of the Graeco-Roman world. The later history of the Indo-Greek states, which lasted to around the shift BC/AD, is reconstructed almost entirely from archaeological and numismatical analyses. | ||

| ; Later History | |||

| Later HistoryThroughout the 1st century BC, the Indo-Greeks progressively lost ground to the Indians in the east, and the Scythians, the Yuezhi, and the Parthians in the West. About 20 Indo-Greek king are known during this period, down to the last known Indo-Greek ruler, a king named Strato II, who ruled in the Punjab region until around 55 BC. Other sources, however, place the end of Strato II's reign as late as AD 10 – see below in the list of coins. | |||

| Throughout the 1st century BC, the Indo-Greeks progressively lost ground to the Indians in the east, and the Scythians, the Yuezhi, and the Parthians in the West. About 20 Indo-Greek king are known during this period, down to the last known Indo-Greek ruler, a king named Strato II, who ruled in the Punjab region until around 55 BC. Other sources, however, place the end of Strato II's reign as late as AD 10 – see below in the list of coins. | |||

| Loss of Eastern territories (circa 100 BC) | ;Loss of Eastern territories (circa 100 BC) | ||

| The Indo-Greeks may have ruled as far as the area of Mathura until the 1st century BC: the Maghera inscription, from a village near Mathura, records the dedication of a well "in the one hundred and sixteenth year of the reign of the Yavanas", which could be as late as 70 BC. Soon however Indian kings recovered the area of Mathura and south-eastern Punjab, west of the Yamuna River, and started to mint their own coins. The Arjunayanas (area of Mathura) and Yaudheyas mention military victories on their coins ("Victory of the Arjunayanas", "Victory of the Yaudheyas"). During the 1st century BC, the Trigartas, Audumbaras and finally the Kunindas also started to mint their own coins, usually in a style highly reminiscent of Indo-Greek coinage. | The Indo-Greeks may have ruled as far as the area of Mathura until the 1st century BC: the Maghera inscription, from a village near Mathura, records the dedication of a well "in the one hundred and sixteenth year of the reign of the Yavanas", which could be as late as 70 BC. Soon however Indian kings recovered the area of Mathura and south-eastern Punjab, west of the Yamuna River, and started to mint their own coins. The Arjunayanas (area of Mathura) and Yaudheyas mention military victories on their coins ("Victory of the Arjunayanas", "Victory of the Yaudheyas"). During the 1st century BC, the Trigartas, Audumbaras and finally the Kunindas also started to mint their own coins, usually in a style highly reminiscent of Indo-Greek coinage. | ||

| The Western king Philoxenus briefly occupied the whole remaining Greek territory from the Paropamisadae to Western Punjab between 100 to 95 BC, after what the territories fragmented again. The western kings regained their territory as far west as Arachosia, and eastern kings continued to rule on and off until the beginning of our era. | The Western king Philoxenus briefly occupied the whole remaining Greek territory from the Paropamisadae to Western Punjab between 100 to 95 BC, after what the territories fragmented again. The western kings regained their territory as far west as Arachosia, and eastern kings continued to rule on and off until the beginning of our era. | ||

| ; Scythian invasions (80 BC – 20 AD) | |||

| {{Main|Indo-Scythians}} | |||

| Around 80 BC, an Indo-Scythian king named Maues, possibly a general in the service of the Indo-Greeks, ruled for a few years in northwestern India before the Indo-Greeks again took control. He seems to have been married to an Indo-Greek princess. King Hippostratos (65–55 BC) seems to have been one of the most successful subsequent Indo-Greek kings until he lost to the Indo-Scythian Azes I, who established an Indo-Scythian dynasty. Various coins seem to suggest that some sort of alliance may have taken place between the Indo-Greeks and the Scythians. | Around 80 BC, an Indo-Scythian king named Maues, possibly a general in the service of the Indo-Greeks, ruled for a few years in northwestern India before the Indo-Greeks again took control. He seems to have been married to an Indo-Greek princess. King Hippostratos (65–55 BC) seems to have been one of the most successful subsequent Indo-Greek kings until he lost to the Indo-Scythian Azes I, who established an Indo-Scythian dynasty. Various coins seem to suggest that some sort of alliance may have taken place between the Indo-Greeks and the Scythians. | ||

| Line 253: | Line 227: | ||

| Although the Indo-Scythians clearly ruled militarily and politically, they remained surprisingly respectful of Greek and Indian cultures. Their coins were minted in Greek mints, continued using proper Greek and Kharoshthi legends, and incorporated depictions of Greek deities, particularly Zeus. The Mathura lion capital inscription attests that they adopted the Buddhist faith, as do the depictions of deities forming the vitarka mudra on their coins. Greek communities, far from being exterminated, probably persisted under Indo-Scythian rule. There is a possibility that a fusion, rather than a confrontation, occurred between the Greeks and the Indo-Scythians: in a recently published coin, Artemidoros presents himself as "son of Maues", and the Buner reliefs show Indo-Greeks and Indo-Scythians reveling in a Buddhist context. | Although the Indo-Scythians clearly ruled militarily and politically, they remained surprisingly respectful of Greek and Indian cultures. Their coins were minted in Greek mints, continued using proper Greek and Kharoshthi legends, and incorporated depictions of Greek deities, particularly Zeus. The Mathura lion capital inscription attests that they adopted the Buddhist faith, as do the depictions of deities forming the vitarka mudra on their coins. Greek communities, far from being exterminated, probably persisted under Indo-Scythian rule. There is a possibility that a fusion, rather than a confrontation, occurred between the Greeks and the Indo-Scythians: in a recently published coin, Artemidoros presents himself as "son of Maues", and the Buner reliefs show Indo-Greeks and Indo-Scythians reveling in a Buddhist context. | ||

| The Indo-Greeks continued to rule a territory in the eastern Punjab, until the kingdom of the last Indo-Greek king Strato was taken over by the Indo-Scythian ruler Rajuvula around |

The Indo-Greeks continued to rule a territory in the eastern Punjab, until the kingdom of the last Indo-Greek king Strato was taken over by the Indo-Scythian ruler Rajuvula around 10 AD. | ||

| ; Western Yuezhi or Saka expansion (70 BC-) | |||

| Around eight "western" Indo-Greek kings are known; most of them are distinguished by their issues of Attic coins for circulation in the neighbouring. | Around eight "western" Indo-Greek kings are known; most of them are distinguished by their issues of Attic coins for circulation in the neighbouring. | ||

| Line 261: | Line 235: | ||

| One of the last important kings in the Paropamisadae was Hermaeus, who ruled until around 80 BC; soon after his death the Yuezhi or Sakas took over his areas from neighbouring Bactria. When Hermaeus is depicted on his coins riding a horse, he is equipped with the recurve bow and bow-case of the steppes and RC Senior believes him to be of partly nomad origin. The later king Hippostratus may however also have held territories in the Paropamisadae. | One of the last important kings in the Paropamisadae was Hermaeus, who ruled until around 80 BC; soon after his death the Yuezhi or Sakas took over his areas from neighbouring Bactria. When Hermaeus is depicted on his coins riding a horse, he is equipped with the recurve bow and bow-case of the steppes and RC Senior believes him to be of partly nomad origin. The later king Hippostratus may however also have held territories in the Paropamisadae. | ||

| After the death of Hermaeus, the Yuezhi or Saka nomads became the new rulers of the Paropamisadae, and minted vast quantities of posthumous issues of Hermaeus up to around |

After the death of Hermaeus, the Yuezhi or Saka nomads became the new rulers of the Paropamisadae, and minted vast quantities of posthumous issues of Hermaeus up to around 40 AD, when they blend with the coinage of the Kushan king Kujula Kadphises. The first documented Yuezhi prince, Sapadbizes, ruled around 20 BC, and minted in Greek and in the same style as the western Indo-Greek kings, probably depending on Greek mints and celators. | ||

| The last known mention of an Indo-Greek ruler is suggested by an inscription on a signet ring of the 1st century AD in the name of a king Theodamas, from the Bajaur area of Gandhara, in modern Pakistan. No coins of him are known, but the signet bears in kharoshthi script the inscription "Su Theodamasa", "Su" being explained as the Greek transliteration of the ubiquitous Kushan royal title "Shau" ("Shah", "King"). | The last known mention of an Indo-Greek ruler is suggested by an inscription on a signet ring of the 1st century AD in the name of a king Theodamas, from the Bajaur area of Gandhara, in modern Pakistan. No coins of him are known, but the signet bears in kharoshthi script the inscription "Su Theodamasa", "Su" being explained as the Greek transliteration of the ubiquitous Kushan royal title "Shau" ("Shah", "King"). | ||

| Ideology | ;Ideology | ||

| Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek kings, and their rule, especially that of Menander, has been remembered as benevolent. It has been suggested, although direct evidence is lacking, that their invasion of India was intended to show their support for the Mauryan empire which may have had a long history of marital alliances, exchange of presents, demonstrations of friendship, exchange of ambassadors and religious missions with the Greeks. The historian Diodorus even wrote that the king of Pataliputra had "great love for the Greeks". | Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek kings, and their rule, especially that of Menander, has been remembered as benevolent. It has been suggested, although direct evidence is lacking, that their invasion of India was intended to show their support for the Mauryan empire which may have had a long history of marital alliances, exchange of presents, demonstrations of friendship, exchange of ambassadors and religious missions with the Greeks. The historian Diodorus even wrote that the king of Pataliputra had "great love for the Greeks". | ||

| Line 277: | Line 251: | ||

| In Indian literature, the Indo-Greeks are described as Yavanas (in Sanskrit), or Yonas (in Pali) both thought to be transliterations of "Ionians". In the Harivamsa the "Yavana" Indo-Greeks are qualified, together with the Sakas, Kambojas, Pahlavas and Paradas as Kshatriya-pungava i.e. foremost among the Warrior caste, or Kshatriyas. The Majjhima Nikaya explains that in the lands of the Yavanas and Kambojas, in contrast with the numerous Indian castes, there were only two classes of people, Aryas and Dasas (masters and slaves). | In Indian literature, the Indo-Greeks are described as Yavanas (in Sanskrit), or Yonas (in Pali) both thought to be transliterations of "Ionians". In the Harivamsa the "Yavana" Indo-Greeks are qualified, together with the Sakas, Kambojas, Pahlavas and Paradas as Kshatriya-pungava i.e. foremost among the Warrior caste, or Kshatriyas. The Majjhima Nikaya explains that in the lands of the Yavanas and Kambojas, in contrast with the numerous Indian castes, there were only two classes of people, Aryas and Dasas (masters and slaves). | ||

| ; Religion | |||

| In addition to the worship of the Classical pantheon of the Greek deities found on their coins (Zeus, Herakles, Athena, Apollo...), the Indo-Greeks were involved with local faiths, particularly with Buddhism, but also with Hinduism and Zoroastrianism. | In addition to the worship of the Classical pantheon of the Greek deities found on their coins (Zeus, Herakles, Athena, Apollo...), the Indo-Greeks were involved with local faiths, particularly with Buddhism, but also with Hinduism and Zoroastrianism. | ||

| Line 283: | Line 257: | ||

| After the Greco-Bactrians militarily occupied parts of northern India from around 180 BC, numerous instances of interaction between Greeks and Buddhism are recorded. Menander I, the "Saviour king", seems to have converted to Buddhism, and is described as a great benefactor of the religion, on a par with Ashoka or the future Kushan emperor Kanishka. The wheel he represented on some of his coins was probably Buddhist, and he is famous for his dialogues with the Buddhist monk Nagasena, transmitted to us in the Milinda Panha, which explain that he became a Buddhist arhat: | After the Greco-Bactrians militarily occupied parts of northern India from around 180 BC, numerous instances of interaction between Greeks and Buddhism are recorded. Menander I, the "Saviour king", seems to have converted to Buddhism, and is described as a great benefactor of the religion, on a par with Ashoka or the future Kushan emperor Kanishka. The wheel he represented on some of his coins was probably Buddhist, and he is famous for his dialogues with the Buddhist monk Nagasena, transmitted to us in the Milinda Panha, which explain that he became a Buddhist arhat: | ||

| "And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he (Menander) handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the house-less state, grew great in insight, and himself attained to Arahatship!" | :"And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he (Menander) handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the house-less state, grew great in insight, and himself attained to Arahatship!" | ||

| ::– ''The Questions of King Milinda'', translation by T. W. Rhys Davids. | |||

| Another Indian text, the Stupavadana of Ksemendra, mentions in the form of a prophecy that Menander will build a stupa in Pataliputra. | Another Indian text, the Stupavadana of Ksemendra, mentions in the form of a prophecy that Menander will build a stupa in Pataliputra. | ||

| Line 291: | Line 265: | ||

| "But when one Menander, who had reigned graciously over the Bactrians, died afterwards in the camp, the cities indeed by common consent celebrated his funerals; but coming to a contest about his relics, they were difficultly at last brought to this agreement, that his ashes being distributed, everyone should carry away an equal share, and they should all erect monuments to him." | "But when one Menander, who had reigned graciously over the Bactrians, died afterwards in the camp, the cities indeed by common consent celebrated his funerals; but coming to a contest about his relics, they were difficultly at last brought to this agreement, that his ashes being distributed, everyone should carry away an equal share, and they should all erect monuments to him." | ||

| —Plutarch, "Political Precepts" Praec. reip. ger. 28, 6). | —Plutarch, "Political Precepts" Praec. reip. ger. 28, 6). | ||

| The Butkara stupa was "monumentalized" by the addition of Hellenistic architectural decorations during Indo-Greek rule in 2nd century |

The Butkara stupa was "monumentalized" by the addition of Hellenistic architectural decorations during Indo-Greek rule in 2nd century BC. | ||

| --> | --> | ||

| ===Eucratides the Great=== | |||

| ==Usurpation of Eucratides== | |||

| ] of King ], 171–145 BC. The ] inscription reads: {{lang|grc-x-hellen|ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΕΥΚΡΑΤΙΔΟΥ}}, ''Basileōs Megalou Eukratidou'' – "(of) Great King Eucratides".]] | |||

| Back in Bactria, ], either a general of Demetrius or an ally of the ], managed to overthrow the Euthydemid dynasty and establish his own rule around 170 BC, probably dethroning ] and ]. The Indian branch of the Euthydemids tried to strike back. An Indian king called Demetrius (very likely ]) is said to have returned to Bactria with 60,000 men to oust the usurper, but he apparently was defeated and killed in the encounter: | |||

| Back in Bactria, ], either a general of Demetrius or an ally of the ], managed to overthrow the Euthydemid dynasty and establish his own rule, the short-lived Eucratid dynasty,<ref>{{Cite book|last=Cary|first=M.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-aUcI5B_wDAC&q=Helioclid+dynasty|title=A History of the Greek World Form 323 to 146 B.C|date=1963|pages=75}}</ref> around 170 BC, probably dethroning ] and ]. The Indian branch of the Euthydemids tried to strike back. An Indian king called Demetrius (very likely ]) is said to have returned to Bactria with 60,000 men to oust the usurper, but he apparently was defeated and killed in the encounter: | |||

| ] inscription reads: {{lang|grc-x-hellen|ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΕΥΚΡΑΤΙΔΟΥ}}, ''Basileōs Megalou Eukratidou'' – "(of) Great King Eucratides"; on the reverse ] in ] legend reads: ''Maharajasa Evukratidasa'', "of Great King Eucratides"''.''<ref>{{Cite web|title=The COININDIA Coin Galleries: Greek: Eucratides I (Eukratides I)|url=https://coinindia.com/galleries-eucratides1.html|access-date=2024-06-19|website=coinindia.com}}</ref>|303x303px]] | |||

| <blockquote>Eucratides led many wars with great courage, and, while weakened by them, was put under siege by Demetrius, king of the Indians. He made numerous sorties, and managed to vanquish 60,000 enemies with 300 soldiers, and thus liberated after four months, he put India under his rule.<ref name="Justin XLI,6">{{Cite web|url=http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/justin/texte41.html|title=Justin XLI,6|access-date=2006-01-14|archive-date=2019-11-10|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191110100422/http://www.forumromanum.org/literature/justin/texte41.html|url-status=usurped}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Eucratides campaigned extensively in present-day northwestern India, and ruled a vast territory, as indicated by his minting of coins in many Indian mints, possibly as far as the ] in ]. In the end, however, he was repulsed by the Indo-Greek king ], who managed to create a huge unified territory. | |||

| ] of King ] 171–145 BC. The ] inscription reads: ''ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΕΥΚΡΑΤΙΔΟΥ'' – "(of) King Great Eucratides".]] | |||

| ] inscription reads: ''ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΕΥΚΡΑΤΙΔΟΥ''-"(of) King Great Eucratides", ] in the ] script on the reverse.]] | |||

| :Eucratides led many wars with great courage, and, while weakened by them, was put under siege by Demetrius, king of the Indians. He made numerous sorties, and managed to vanquish 60,000 enemies with 300 soldiers, and thus liberated after four months, he put India under his rule. (Justin, XLI,6)<ref name="Justin XLI,6"></ref> | |||

| Eucratides campaigned extensively in present-day northwestern India, and ruled on a vast territory as indicated by his minting of coins in many Indian mints, possibly as far as the ] in ]. In the end however, he was repulsed by the Indo-Greek king ], who managed to create a huge unified territory. | |||

| In a rather confused account, Justin explains that Eucratides was killed on the field by "his son and joint king", who would be his own son, either ] or ] (although there are speculations that it could |

In a rather confused account, ] explains that Eucratides was killed on the field by "his son and joint king", who would be his own son, either ] or ] (although there are speculations that it could have been his enemy's son ]). The son drove over Eucratides' bloodied body with his chariot and left him dismembered without a sepulcher: | ||

| <blockquote>As Eucratides returned from India, he was killed on the way back by his son, whom he had associated to his rule, and who, without hiding his parricide, as if he didn't kill a father but an enemy, ran with his chariot over the blood of his father, and ordered the corpse to be left without a sepulture.<ref name="Justin XLI,6"/></blockquote> | |||

| ===Defeats by Parthia=== | ===Defeats by Parthia=== | ||

| During or after his Indian campaigns, Eucratides was attacked and defeated by the ]n king ], possibly in alliance with partisans of the Euthydemids: | During or after his Indian campaigns, Eucratides was attacked and defeated by the ]n king ], possibly in alliance with partisans of the Euthydemids: | ||

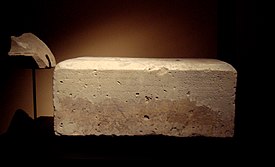

| ] of ], the largest gold coin of Antiquity. The coin weighs 169.2 grams, and has a diameter of 58 millimeters.]] | ] of ], the largest gold coin of Antiquity. The coin weighs 169.2 grams, and has a diameter of 58 millimeters. The reverse shows the ] on horseback.|303x303px]] | ||