| Revision as of 18:13, 17 November 2016 editLilHelpa (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers413,750 editsm Typos and general fixes, replaced: properous → prosperous using AWB← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:03, 20 January 2025 edit undoMaplesyrupSushi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,424 edits →Journeys: duplicate infoTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ninth Sikh guru from 1665 to 1675}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| {{Infobox religious biography | |||

| | image = Guru teg bahadur.jpg | |||

| | |

| religion = ] | ||

| | name = Guru Tegh Bahadur | |||

| | birth_name = Tyaga Mal Khatri | |||

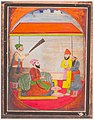

| | image = Contemporary painting of Guru Tegh Bahadur by Ahsan, ca.1668.jpg | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth-date|1 April 1621}} | |||

| | alt = | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] (Present day ]) | |||

| | caption = A mid-17th-century portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur painted by Ahsan, the viceregal painter of Shaista Khan, governor of Bengal, circa 1668–69 | |||

| | death_date = {{Death-date and age|24 November 1675|1 April 1621}} | |||

| | birth_name = Tyag Mal | |||

| | death_place = ], ] (Present day ]) | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth-date| 1 April 1621}} | |||

| | years_active = 1664–1675 | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] <br /> {{small|(present-day ], ])}} | |||

| | residence = ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death-date and age|11 November 1675| 11 April 1621}} | |||

| | other_names = ''The Shield of ]'', ''Mighty of the Sword'', ''The Ninth Master'', The True King | |||

| | death_place = ], ] <br /> {{small|(present-day ])}} | |||

| | known_for = Spiritual contributions to Guru Granth Sahib, ] for defending human rights and freedom of conscience, founding of ], founder of ] | |||

| | death_cause = ] | |||

| | occupation = | |||

| | |

| period = 1664–1675 | ||

| | |

| known_for = * Hymns to Guru Granth Sahib | ||

| * Executed under the reign of Mughal Emperor ].<ref name="pslf" /><ref>Gill, Sarjit S., and Charanjit Kaur (2008), "Gurdwara and its politics: Current debate on Sikh identity in Malaysia", SARI: Journal Alam dan Tamadun Melayu, Vol. 26 (2008), pages 243–255, Quote: "Guru Tegh Bahadur died in order to protect the freedom of India from invading Mughals."</ref><ref name=cs2013/><ref name=sg2007>{{cite book|last=Gandhi|first=Surjit|title=History of Sikh gurus retold|publisher=Atlantic Publishers|year=2007|isbn=978-81-269-0858-5|pages=653–91}}</ref> | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| * Founder of ] | |||

| | spouse = ] | |||

| | children = ] | |||

| | parents = ] and ] | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | battles = ]<br>] (1635) Skirmish Of Dhubri (1669) | |||

| | native_name = ਗੁਰੂ ਤੇਗ਼ ਬਹਾਦਰ | |||

| | native_name_lang = pa | |||

| | signature = Authentic signature (neeshan) of Guru Tegh Bahadur.jpg | |||

| | signature_size = 80px | |||

| | other_name = Ninth Master<br>Ninth Nanak<br>''Srisht-di-Chadar'' ("Shield of The World")<br>''Dharam-di-Chadar'' ("Shield of ]")<ref>{{cite web |last1=Singh |first1=Harmeet Shah |title=Explained - The legacy of Guru Teg Bahadar and its revisionism |url=https://www.indiatoday.in/news-analysis/story/legacy-guru-teg-bahadar-sikh-guru-1940109-2022-04-21 |website=India Today |date=21 April 2022 |quote=Take for instance, the description of Guru Teg Bahadar as 'Hind di Chadar' in present-day parlance and 'Dharam di Chadar' some 100 years ago. That appears to be a departure from how he was originally described in contemporaneous poetic texts after his execution in 1675. Chandra Sain Sainapati was a court poet of Guru Gobind Singh, the son of Guru Teg Bahadar. In his composition called Sri Gur Sobha, Sainapati described the martyred Guru as 'Srisht ki Chadar', or the protector of humanity. 'Pargat Bhae Gur Teg Bahadar, Sagal Srisht Pe Dhaapi Chadar,' the poet wrote, meaning 'Guru Tegh Bahadar was revealed, and protected the whole creation.'}}</ref><br>''Hind-di-Chadar'' ("Shield of ]") | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Sikhism sidebar}} | {{Sikhism sidebar}} | ||

| ]|456x456px]] | |||

| '''Guru Tegh Bahadur''' ( |

'''Guru Tegh Bahadur''' (]: ਗੁਰੂ ਤੇਗ਼ ਬਹਾਦਰ <small>(])</small>; {{IPA|pa|gʊɾuː t̯eːɣ bəɦaːd̯ʊɾᵊ}}; 1 April 1621 – 11 November 1675)<ref>{{cite book|title=Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism|year=1984|publisher=Manchester University Press|pages=32–33|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Mj28AAAAIAAJ|author=W. H. McLeod|access-date=14 November 2013|isbn=9780719010637|archive-date=18 February 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200218101303/https://books.google.com/books?id=Mj28AAAAIAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=The Ninth Master Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675)|url=http://www.sikhs.org/guru9.htm|website=sikhs.org|access-date=23 November 2014|archive-date=7 January 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190107050930/http://www.sikhs.org/guru9.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> was the ninth of ten ] who founded the ] and was the leader of Sikhs from 1665 until his ] in 1675. He was born in ], ], India in 1621 and was the youngest son of ], the sixth Sikh guru. Considered a principled and fearless warrior, he was a learned spiritual scholar and a poet whose 115 hymns are included in the ], which is the main text of Sikhism. | ||

| Tegh Bahadur was executed on the orders of ], the sixth ] emperor, in ], India.<ref name="cs2013">{{cite book|last=Seiple|first=Chris|title=The Routledge handbook of religion and security|publisher=Routledge|year=2013|isbn=978-0-415-66744-9|location=New York|page=96}}</ref><ref name="bbcgtb">{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/sikhism/people/teghbahadur.shtml|title=Religions – Sikhism: Guru Tegh Bahadur|publisher=]|access-date=20 October 2016|archive-date=14 April 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170414075330/http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/sikhism/people/teghbahadur.shtml|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="fenech4">{{cite book|author1=Pashaura Singh|author2=Louis E. Fenech|title=The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8I0NAwAAQBAJ|year=2014|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-969930-8|pages=236–238|access-date=12 June 2017|archive-date=4 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190504190932/https://books.google.com/books?id=8I0NAwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}};<br />{{cite journal | last=Fenech | first=Louis E. | title=Martyrdom and the Execution of Guru Arjan in Early Sikh Sources | journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society | publisher= American Oriental Society | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| | volume=121 | issue=1 | year=2001 |doi=10.2307/606726 | pages=20–31| jstor=606726 }};<br />{{cite journal | last=Fenech | first=Louis E. | title=Martyrdom and the Sikh Tradition | journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society | publisher=American Oriental Society | volume=117 | issue=4 | year=1997 | doi=10.2307/606445 | pages=623–642| jstor=606445 }};<br />{{cite journal | last=McLeod | first=Hew | title=Sikhs and Muslims in the Punjab | journal=South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies | publisher=Taylor & Francis | volume=22 | issue=sup001 | year=1999 | issn=0085-6401 | doi=10.1080/00856408708723379 | pages=155–165}}</ref> Sikh holy premises ] and ] in Delhi mark the places of execution and cremation of Guru Tegh Bahadur.<ref name="singharakab">{{cite book|author=H. S. Singha|title=The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries)|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gqIbJz7vMn0C|year=2000|publisher=Hemkunt Press|isbn=978-81-7010-301-1|page=169|access-date=30 October 2016|archive-date=20 September 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200920113541/https://books.google.com/books?id=gqIbJz7vMn0C|url-status=live}}</ref> His day of martyrdom (''Shaheedi Divas'') is commemorated in India every year on 24 November.<ref name="nesbitt122">{{cite book|author=Eleanor Nesbitt|title=Sikhism: a Very Short Introduction|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XebnCwAAQBAJ|year=2016|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-874557-0|pages=6, 122–123|access-date=9 March 2017|archive-date=9 March 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170309075522/https://books.google.com/books?id=XebnCwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Guru Tegh Bahadur was born in a Sodhi Family.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Nabha|first1=Kahan|title=Mahan Kosh}}</ref> The Sixth guru, ] had one daughter Bibi Viro and five sons: Baba Gurditta, Suraj Mal, Ani Rai, Atal Rai and Tyaga Mal Khatri. Tyaga Mal Khatri was born in ] in the early hours of 1 April 1621. The name ''Tegh Bahadur'' (Mighty Of The Sword), was given to him by Guru Hargobind after he had shown his valour in a battle against the Mughals. | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| Amritsar at that time was the centre of Sikh faith. As the seat of the ], and with its connection to Sikhs in far-flung areas of the country through the chains of ''Masands'' or missionaries, it had developed the characteristics of a state capital. Guru Tegh Bahadur was brought up in Sikh culture and trained in ] and ]. He was also taught the old classics. He underwent prolonged spells of seclusion and contemplation. Tegh Bahadur was married on 3 February 1633, to Mata Gujri.<ref>{{cite book|last=Smith|first=Bonnie|title=The Oxford encyclopedia of women in world history|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, New York|year=2008|isbn=978-0-19-514890-9|page=410}}</ref> | |||

| ===Early life=== | |||

| Guru Tegh Bahadur was born ''Tyag Mal'' (Tīāg Mal) ({{langx|pa|ਤਿਆਗ ਮਲ}}) in Amritsar on 1 April 1621. He was the youngest son of Guru Hargobind, the sixth guru.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":5">{{Cite book |last1=Bhatia |first1=H.S. |url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopaedichis0000unse_f4o8/page/26/mode/2up?view=theater&q=%22April+1%22 |title=The Sikh Gurus and Sikhism |last2=Bakshi |first2=S.R. |publisher=Deep & Deep Publications |year=2000 |isbn=8176291307 |pages=}}</ref>{{Rp|page=27}} His family belonged to the ] clan of ]. Hargobind had one daughter, Bibi Viro, and five sons: Baba Gurditta, Suraj Mal, Ani Rai, Atal Rai, and Tyag Mal.<ref>{{Cite book |last=McLeod |first=W. H. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vgixwfeCyDAC&pg=PA88 |title=The A to Z of Sikhism |date=2009-07-24 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=978-0-8108-6344-6 |pages=88 |language=en}}</ref> He gave Tyag Mal the name ''Tegh Bahadur'' (Brave Sword) after Tyag Mal showed valor in the ] against the Mughals.<ref name=":3">{{cite book |author1=William Owen Cole |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zIC_MgJ5RMUC&pg=PA34 |title=The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices |author2=Piara Singh Sambhi |publisher=Sussex Academic Press |year=1995 |isbn=978-1-898723-13-4 |pages=32–35 |access-date=23 November 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200528230214/https://books.google.com/books?id=zIC_MgJ5RMUC&pg=PA34%2F |archive-date=28 May 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Tegh Bahadur was brought up in the Sikh culture and trained in ] and ]. He was also taught the old classics such as the ], the ], and the ]. He was married on 3 February 1632 to ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Smith|first=Bonnie|title=The Oxford encyclopedia of women in world history, Volume 2|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, New York|year=2008|isbn=978-0-19-514890-9|page=|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/oxfordencycloped0000unse_k2h2/page/410}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=H.S. Singha|title=Sikh Studies|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nRodBu9seiIC&pg=PA21|year=2005|publisher=Hemkunt Press|isbn=978-81-7010-245-8|pages=21–22|access-date=28 June 2018|archive-date=4 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190504192024/https://books.google.com/books?id=nRodBu9seiIC&pg=PA21|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Stay at Bakala== | |||

| In the 1640s, nearing his death, Guru Hargobind said to his wife Nanaki, to move to his ancestral village of ] in ], together with Guru Tegh Bahadur and ]. Bakala, as described in ''Gurbilas Dasvin Patishahi'', was then a prosperous town with many beautiful pools, wells and ''baolis''. | |||

| In the 1640s, nearing his death, Guru Hargobind and his wife Nanaki moved to his ancestral village of ] in ], together with Tegh Bahadur and Gujri. After Hargobind's death, Tegh Bahadur continued to live in Bakala with his wife and mother.<ref name=gandhi621>{{cite book|last=Gandhi|first=Surjit|title=History of Sikh gurus retold|publisher=Atlantic Publishers|year=2007|isbn=978-81-269-0858-5|pages=621–22}}</ref> | |||

| ===Installation as Guru of Sikhs=== | |||

| ==Guruship== | |||

| In March 1664 Guru Har Krishan contracted smallpox. When |

In March 1664, ] contracted ]. When his followers asked who would lead them after him, he said, "''Baba Bakala''", meaning his successor was to be found in Bakala. Taking advantage of the ambiguity in the words of the dying guru, many installed themselves in Bakala, claiming to be the new guru. Sikhs were puzzled to see so many claimants.<ref name=mk1992/><ref name="hss2000">{{cite book|last=Singha|first=H.S.|title=The encyclopedia of Sikhism|publisher=Hemkunt Publishers|year=2000|isbn=978-81-7010-301-1|page=85}}</ref> | ||

| Sikh tradition has a legend about how Tegh Bahadur was selected as the ninth guru. A wealthy trader named ] had vowed to give 500 gold coins to the Sikh Guru upon escaping a shipwreck some time ago, and he came to Bakala in search of the ninth guru. He met each claimant he could find, making his obeisance and offering them two gold coins in the belief that the right guru would know of his silent promise to give them 500 coins. Every "guru" he met accepted the two gold coins and bid him farewell. Then he discovered that Tegh Bahadur also lived at Bakala. Makhan Shah gave Tegh Bahadur the usual offering of two gold coins. Tegh Bahadur blessed him and remarked that his offering was short of the promised five hundred. Makhan Shah made good the difference and ran upstairs. He began shouting from the rooftop, "''Guru ladho re, Guru ladho re''", meaning "I have found the Guru, I have found the Guru".<ref name=mk1992>{{cite book|last=Kohli|first=Mohindar|title=Guru Tegh Bahadur: testimony of conscience|publisher=Sahitya Akademi|year=1992|isbn=978-81-7201-234-2|pages=13–15}}</ref> | |||

| In August 1664 a Sikh |

In August 1664, a Sikh congregation led by Diwan Dargha Mal, son of a well-known devotee of Har Krishan, arrived in Bakala and appointed Tegh Bahadur as the ninth guru of Sikhs.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Singh |first1=Fauja |title=Guru Tegh Bahadur: Martyr and Teacher |last2=Talib |first2=Gurbachan Singh |publisher=Punjabi University |year=1975 |pages=24–26}}</ref> | ||

| As had been the custom among Sikhs after the execution of ] by Mughal Emperor Jahangir, Guru Tegh Bahadur was surrounded by armed bodyguards |

As had been the custom among Sikhs after the execution of ] by Mughal Emperor Jahangir, Guru Tegh Bahadur was surrounded by armed bodyguards,<ref>{{cite book|author=H.R. Gupta|isbn=9788121502764|title=History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Gurus, 1469–1708|year=1994|volume=1|page=188}}</ref> but he otherwise lived an austere life.<ref name=mk37>{{cite book|last=Kohli|first=Mohindar|title=Guru Tegh Bahadur : testimony of conscience|publisher=Sahitya Akademi|year=1992|isbn=978-81-7201-234-2|pages=37–41}}</ref> | ||

| === |

=== Journeys === | ||

| Guru Tegh Bahadur traveled extensively in different parts of the ], including ] and ], to preach the teachings of ], the first Sikh guru. The places he visited and stayed in became sites of Sikh temples.<ref>{{cite book|last=Singha|first=H.S.|title=The encyclopedia of Sikhism|publisher=Hemkunt Publishers|year=2000|isbn=978-81-7010-301-1|pages=139–40}}</ref> During his travels, he started a number of community water wells and ''langars'' (community kitchens for the poor).<ref name="ps189">{{cite book|last=Singh|first=Prithi|title=The history of Sikh gurus|publisher=Lotus Press|year=2006|isbn=978-81-8382-075-2|pages=187–89}}</ref><ref name="rp88">{{cite book|last=Pruthi|first=Raj|title=Sikhism and Indian civilization|year=2004|isbn=978-81-7141-879-4|page=88|publisher=Discovery Publishing House }}</ref> | |||

| Tegh Bahadur visited the towns of Mathura, Agra, Allahabad and Varanasi.<ref name="nsxviii">{{cite book |author=Gobind Singh (Translated by Navtej Sarna) |title=Zafarnama |publisher=Penguin Books |year=2011 |isbn=978-0-670-08556-9 |pages=xviii–xix}}</ref> His son, ], who would be the tenth Sikh guru, was born in ] in 1666 while he was away in ], Assam, where the ] now stands. While in Assam, it is claimed by Sikh accounts that the guru brokered peace between ] and the Ahom ruler ] (Supangmung).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=Dharam |title=Guru Tegh Bahadur: His Life, Travel and Message |last2=Singh |first2=Paramvir |publisher=Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting |year=2022 |isbn=9789354095832 |quote=There took place one battle between the opposing forces of Ram Singh and the Ahom king, named Chakradhwaj, but it remained inconclusive. According to Sikh chronicles, the Guru was able to arrange a truce between the opposing forces and opened the way for a negotiated settlement. The Guru succeeded in bringing about a rapprochement between them and thus more bloodshed was avoided. To celebrate the happy conclusion, soldiers of Ram Singh's camp raised a high mound on the bank of the Brahmputra, each soldier contributing five shields of earth. On the top of this mound now stands Thara Sahib or Damdama Sahib ...}}</ref><ref name="ps189" /><ref>{{cite book |last=Kohli |first=Mohindar |title=Guru Tegh Bahadur: testimony of conscience |publisher=Sahitya Akademi |year=1992 |isbn=978-81-7201-234-2 |pages=25–27}}</ref> | |||

| His works are included in '']'' (pages 219-1427).<ref name=mahalla>{{cite book|author=Tegh Bahadur (Translated by Gopal Singh)|title=Mahalla nawan: compositions of Guru Tegh Bahādur-the ninth guru (from Sri Guru Granth Sahib): Bāṇī Gurū Tega Bahādara|publisher=Allied Publishers|year=2005|isbn=978-81-7764-897-3|accessdate=20 October 2016|pages=xxviii-xxxiii, 15–27}}</ref> They cover a wide range of topics, such as the nature of God, human attachments, body, mind, sorrow, dignity, service, death and deliverance.<ref name=mahalla/> For example, in ''Sorath rag'', Guru Tegh Bahadur describes what an ideal human being is like,<ref name=mahalla/> | |||

| After his visit to Assam, Bengal, and Bihar, Guru Tegh Bahadur visited Rani Champa of ], who offered to give the Guru a piece of land in her state. The Guru bought the site for 500 ]. There, he founded the city of ] in the foothills of the Himalayas.<ref name="bbcgtb" /><ref>{{cite book|last=Singha|first=H.S.|title=The encyclopedia of Sikhism|publisher=Hemkunt Publishers|year=2000|isbn=978-81-7010-301-1|page=21}}</ref> In 1672, Tegh Bahadur traveled in and around the Malwa region to meet the masses as the persecution of ]s reached new heights.<ref>{{cite book|last=Singh|first=Prithi|title=The history of Sikh gurus|publisher=Lotus Press|year=2006|isbn=978-81-8382-075-2|pages=121–24}}</ref> | |||

| {{Quotation| | |||

| <poem> | |||

| ''jo nar dukh mein dukh nahin manney, sukh snehh ar phey nahi ja kai, kanchan maati manney'' | |||

| ''na nindya nehn usttat ja kai lobh moh abhimana'' | |||

| ''harakh sog tey rahey niaro nahen maan apmana, aasa mansa sagal tyagey'' | |||

| ''jagg tey rahey nirasa, kaam krodh jeh parsai nahin teh ghatt ] niwasa'' | |||

| ''Gur kirpa jeh nar kao kini teh eh jugti pachani'' | |||

| ''nanak leen bhayo gobind sao jayo pani sang pani'' | |||

| ==Execution== | |||

| One who is not perturbed by misfortune, who is beyond comfort, attachment and fear, who considers gold as dust. | |||

| He neither speaks ill of others nor feels elated by praise and shuns greed, attachments and arrogance. | |||

| He is indifferent to ecstasy and tragedy, is not affected by honors or humiliations. He renounces expectations, greed. | |||

| He is neither attached to the worldliness, nor lets senses and anger affect him. | |||

| In such a person resides ]. | |||

| </poem> | |||

| |Guru Tegh Bahadur|Sorath 633 (Translated by Gopal Singh)|<ref name=mahalla/>}} | |||

| === |

=== Narrative === | ||

| Many scholars identify the traditional Sikh narrative as follows: A congregation of Hindu ] from Kashmir requested help against Aurangzeb's persecutions and oppressive policies, and Guru Tegh Bahadur decided to protect their rights.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jerryson |first1=Michael |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pfjtDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA684 |title=Religious Violence Today: Faith and Conflict in the Modern World |year=2020 |isbn=9781440859915 |page=684|publisher=Abc-Clio }}</ref> According to Trilochan Singh in ''Guru Tegh Bahadur: Prophet and Martyr'', the convoy of Kashmiri Pandits who tearfully pleaded with the Guru at ] were 500 in number and were led by a certain Pandit Kirpa Ram, who recounted tales of religious oppression under the governorship of ].<ref name=":22">{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=Trilochan |title=Guru Tegh Bahadur, Prophet and Martyr: A Biography |publisher=Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee |year=1967 |pages=293–300 |chapter=Chapter XXII}}</ref> The Kashmiri Pandits decided to meet with the Guru after they first sought the assistance of ] at the ], where one of them is said to have had a dream where Shiva instructed the Pandits to seek out the ninth Sikh guru for assistance in their plight and hence a group was formed for carrying out the task.<ref name=":22" /> Guru Tegh Bahadur left from his base at Makhowal to confront the persecution of ] by Mughal officials but was arrested at Ropar and put to jail in Sirhind.<ref name="Grewal1998p71">{{cite book |author=J. S. Grewal |url=https://archive.org/details/sikhsofpunjab0000grew |title=The Sikhs of the Punjab |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-521-63764-0 |pages=–73 |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Purnima Dhavan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q0ZpAgAAQBAJ |title=When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699–1799 |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2011 |isbn=978-0-19-987717-1 |pages=33, 36–37 |access-date=24 August 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190504223455/https://books.google.com/books?id=q0ZpAgAAQBAJ |archive-date=4 May 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> Four months later, in November 1675, he was transferred to Delhi and asked to perform a miracle to prove his nearness to God or convert to Islam.<ref name="Grewal1998p71" /> The Guru declined, and three of his colleagues, who had been arrested with him, were tortured to death in front of him: ] was sawn in two, ] was thrown into a cauldron of boiling liquid, and ] was cut into pieces.<ref name="Grewal1998p71" /><ref name=":5" />{{Rp|page=48}} Thereafter on 11 November, Tegh Bahadur was publicly beheaded in Chandni Chowk, a market square close to the Red Fort.<ref name="Grewal1998p71" /><ref name="SinghFenech2014p236">{{cite book |author1=Pashaura Singh |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7YwNAwAAQBAJ |title=The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2014 |isbn=978-0-19-100411-7 |editor=Louis E. Fenech |pages=236–238 |access-date=24 August 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190504171425/https://books.google.com/books?id=7YwNAwAAQBAJ |archive-date=4 May 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="cs2013" /> | |||

| Guru Tegh Bahadur travelled extensively in different parts of the country, including ] and ], to preach the teachings of Nanak, the first Sikh guru. The places he visited and stayed in, became sites of Sikh temples.<ref>{{cite book|last=Singha|first=H.S.|title=The encyclopedia of Sikhism|publisher=Hemkunt Publishers|year=2000|isbn=978-81-7010-301-1|pages=139–40|accessdate=20 October 2016}}</ref> | |||

| === Historiography === | |||

| During his travels, Guru Tegh Bahadur spread the Sikh ideas and message, as well as started community water wells and langars (community kitchen charity for the poor).<ref name=ps189>{{cite book|last=Singh|first=Prithi|title=The history of Sikh gurus|publisher=Lotus Press|year=2006|isbn=978-81-8382-075-2|pages=187–89}}</ref><ref name=rp88>{{cite book|last=Pruthi|first=Raj|title=Sikhism and Indian civilization|year=2004|isbn=978-81-7141-879-4|page=88|accessdate=20 October 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The primary nucleus of Sikh narratives remains the '']'', a memoir of Guru Gobind Singh, Guru Tegh Bahadur's son, dated between late 1680s and late 1690s.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Fenech |first=Louis E. |date=1997 |title=Martyrdom and the Sikh Tradition |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/606445 |url-status=live |journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society |volume=117 |issue=4 |pages=633 |doi=10.2307/606445 |issn=0003-0279 |jstor=606445 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181006000554/https://www.jstor.org/stable/606445 |archive-date=6 October 2018 |access-date=2 December 2017}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite book|last=Grewal|first=J. S.|title=Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708): Master of the White Hawk|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2020|isbn=9780199494941|pages=9–10|chapter=New Perspectives and Sources}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Doniger |first1=Wendy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FdgWBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA261 |title=Pluralism and Democracy in India: Debating the Hindu Right |last2=Nussbaum |first2=Martha Craven |date=2015 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-539553-2 |pages=261 |language=en}}</ref>{{efn|The authorship is disputed. While ] considered the work to be Guru Gobind Singh's, ] and ] concluded it to be the work of multiple court poets; there is a rough consensus to date the text.<ref name=":1" />}} | |||

| Guru Tegh Bahadur's son and successor recalled the Guru's execution:<ref name="sur">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JHVmEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT379|title=Medieval Panjab in Transition Authority, Resistance and Spirituality C.1500 – C.1700|last1=Singh|first1=Surinder|isbn=9781000609448|page=384|year=2022|publisher=Routledge }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=Trilochan |title=Guru Tegh Bahadur, Prophet and Martyr: A Biography |publisher=Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee |year=1967 |pages=311 |chapter=Chapter XXIV}}</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|In this dark age, Tegh Bahadur performed a great act of chivalry (''saka'') for the sake of the frontal mark and sacred thread. He offered all he had for the holy. He gave up his head, but did not utter a sigh. He suffered martyrdom for the sake of religion. He laid down his head, but not his honor. Real men of God do not perform tricks like showmen. Having broken the pitcher on the head of the Emperor of Delhi, he departed to the world of God. No one has ever performed a deed like him. At his departure, the whole world mourned, while the heavens hailed it as a victory.|]|title=''Bachittar Natak: Apni Katha''}} | |||

| The Guru made three successive visits to ]. On 21 August 1664, Guru went there to console with Bibi Rup upon the death of her father, ], the seventh Sikh guru, and of her brother, Guru Har Krishan.{{citation needed|date=May 2015}} The second visit was on 15 October 1664, at the death on 29 September 1664, of Bassi, the mother of Guru Har Rai. A third visit concluded a fairly extensive journey through northwest Indian subcontinent. His son ], who would be the tenth Sikh guru, was born in ], while he was away in ], Assam in 1666, where stands the ]. He there helped end the war between Raja Ram Singh of Bengal and Raja Chakardwaj of Ahom state (later Assam).<ref name=ps189/><ref>{{cite book|last=Kohli|first=Mohindar|title=Guru Tegh Bahadur: testimony of conscience|publisher=Sahitya Akademi|year=1992|isbn=978-81-7201-234-2|pages=25–27}}</ref> He also visited the towns of Mathura, Agra, Allahabad and Varanasi.<ref name=nsxviii>{{cite book|author=Gobind Singh (Translated by Navtej Sarna)|title=Zafarnama|publisher=Penguin Books|year=2011|accessdate=20 October 2016|isbn=978-0-670-08556-9|pages=xviii-xix}}</ref> | |||

| More Sikh accounts of Guru Tegh Bahadur's execution, all claiming to be sourced from the "testimony of trustworthy Sikhs", only started emerging in around the late eighteenth century, and are thus, often conflicting, according to historian ].<ref name="sc2001" /> | |||

| After his visit to Assam, Bengal and Bihar, the Guru visited Rani Champa of ] who offered to give the Guru a piece of land in her state. The Guru bought the site for 500 ]. There, Guru Tegh Bahadur founded the city of ] in the foothills of Himalayas.<ref name=bbcgtb/><ref>{{cite book|last=Singha|first=H.S.|title=The encyclopedia of Sikhism|publisher=Hemkunt Publishers|year=2000|isbn=978-81-7010-301-1|accessdate=20 October 2016|page=21}}</ref> | |||

| Persian and non Sikh sources<ref>{{Cite book |last=Grewal |first=J.S. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9yj-OwAACAAJ |title=Sikh History From Persian Sources |year=2001 |publisher=Indian History Congress |isbn=978-81-89487-18-8 |pages=12–13 |language=en |quote=Most of the non Sikh sources mention Guru Tegh Bahadur's militancy as the reason for Aurangzeb's action. By contrast, the Sikh sources dwell exclusively on the religious dimension of the situation.}}</ref> maintain that the Guru was a bandit<ref name=":0" /> whose plunder and rapine of Punjab along with his rebellious activities precipitated his execution.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chandavarkar |first=Rajnayaran |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yH4hAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA192 |title=History, Culture and the Indian City |date=2009-09-03 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-48044-4 |pages=192 |language=en |quote=In another, the historian Satish Chandra pointed out that the 'official explanation' for the execution of the Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur by the Mughal court was that he had 'resorted to plunder and rapine'.}}</ref> According to Chandra, the earliest Persian source to chronicle his execution is ''Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin'' by ] c. 1782, where Tegh Bahadur's (alleged) oppression of subjects is held to have incurred Aurangzeb's wrath:<ref name="sc2001">{{cite web|last1=Chandra|first1=Satish|title=Guru Tegh Bahadur's martyrdom|url=http://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/2001/10/16/stories/05162524.htm|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020228135707/http://thehindu.com/thehindu/2001/10/16/stories/05162524.htm|archive-date=28 February 2002|access-date=20 October 2016|work=]}}</ref> | |||

| In 1672 Guru Tegh Bahadur traveled through Kashmir and the North-West Frontier, to meet the masses, as the persecution of non-Muslims reached new heights.<ref>{{cite book|last=Singh|first=Prithi|title=The history of Sikh gurus|publisher=Lotus Press|year=2006|isbn=978-81-8382-075-2|pages=121–24}}</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|Tegh Bahadur, the eighth successor of (Guru) Nanak became a man of authority with a large number of followers. (In fact) several thousand persons used to accompany him as he moved from place to place. His contemporary Hafiz Adam, a faqir belonging to the group of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi's followers, had also come to have a large number of murids and followers. Both these men (Guru Tegh Bahadur and Hafiz Adam) used to move about in Punjab, adopting a habit of coercion and extortion. Tegh Bahadur used to collect money from Hindus and Hafiz Adam from Muslims. The royal ''waqia navis'' (news reporter and intelligence agent) wrote to the Emperor Alamgir ... of their manner of activity, adding that if their authority increased they could become even refractory.|Ghulam Husain|Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin}} | |||

| ==Execution by Aurangzeb== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1675 Guru Tegh Bahadur was executed in ] on 11 November under the orders of the Mughal Emperor ].<ref name=cs2013/><ref name=pslf/> No contemporary detailed accounts of the circumstances of his arrest and execution have survived either in Persian or Sikh sources. The only accounts available are those written about a 100 years later, and these accounts are conflicting.<ref name=sc2001>{{cite web|last1=Chandra|first1=Satish|title=Guru Tegh Bahadur's martyrdom|url=http://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/2001/10/16/stories/05162524.htm|publisher=The Hindu|accessdate=20 October 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Chandra cautions against taking Ghulam Husain's argument at face value, as Ghulam Husain was a relative of ] — one of the closest confidantes of Aurangzeb — and might have been providing an "official justification".<ref name="sc2001" /><ref>{{Cite web|title=Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin – Banglapedia|url=https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin|access-date=2021-09-18|website=en.banglapedia.org|archive-date=18 September 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210918151706/https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin|url-status=live}}</ref> Also, the Guru's alleged association with Hafiz Adam is anachronistic. Chandra further writes that Ghulam Husain's account places Guru Tegh Bahadur's confinement and execution in Lahore, while Sikh tradition places it in Delhi, and Chandra finds no reason to reject said tradition.<ref name="sc2001" /> | |||

| According to the official account of the Mughal Empire, written 107 years later by Ghulam Husain of Lucknow in 1782,<ref name=sc2001/><ref>{{cite book|author=H.R. Gupta|isbn=9788121502764|title=History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Gurus, 1469-1708|volume=1}}<!-- ISSN/ISBN needed --></ref> | |||

| The Sikh ''sakhis'' (traditional accounts)<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=Dogra |first=R. C. |url=http://archive.org/details/encyclopaediaofs0000dogr |title=Encyclopaedia of Sikh religion and culture |date=1995 |publisher=New Delhi : Vikas Pub. House |others=Internet Archive |isbn=978-0-7069-8368-5 |pages=407}}</ref> written during the eighteenth century indirectly support the narrative in the Persian sources, saying that "the Guru was in violent opposition to the Muslim rulers of the country" in response to the dogmatic policies implemented by Aurangzeb.<ref name="ha">{{Cite book |last=Chandra |first=Satish |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rm9MC4DDrcC&pg=PA296 |title=Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals Part - II |date=2005 |publisher=Har-Anand Publications |isbn=978-81-241-1066-9 |pages=296 |language=en}}</ref> Both Persian and Sikh sources agree that Guru Tegh Bahadur militarily opposed the Mughal state and was therefore targeted for execution in accordance with Aurangzeb's zeal for punishing enemies of the state.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Truschke |first=Audrey |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oUUkDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT48 |title=Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India's Most Controversial King |date=2017-05-16 |publisher=Stanford University Press |isbn=978-1-5036-0259-5 |pages=48 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| {{Quotation|Tegh Bahadur, the eighth successor of (Guru) Nanak became a man of authority with a large number of followers. (In fact) several thousand persons used to accompany him as he moved from place to place. His contemporary Hafiz Adam, a faqir belonging to the group of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi's followers, had also come to have a large number of murids and followers. Both these men (Guru Tegh Bahadur and Hafiz Adam) used to move about in the Punjab, adopting a habit of coercion and extortion. Tegh Bahadur used to collect money from Hindus and Hafiz Adam from Muslims. The royal waqia navis (news reporter and intelligence agent) wrote to the Emperor Alamgir of their manner of activity, added that if their authority increased they could become even refractory.|Ghulam Husain|Mughal Empire records|<ref name=sc2001/>}} | |||

| Bhimsen, a contemporary chronicler of Guru Gobind Singh, wrote (c.1708){{sfn|Grewal|2001|p=105}} that the successors of Guru Nanak maintained extravagant lifestyles, and some of them, including Tegh Bahadur, rebelled against the state: Tegh Bahadur proclaimed himself ] and acquired a large following, as a result, Aurangzeb had him executed. Muhammad Qasim's ''Ibratnama,'' written in 1723,{{sfn|Grewal|2001|p=110}} claimed Tegh Bahadur's religious inclinations along with his life of splendor and conferral of sovereignty by his followers had him condemned and executed.{{sfn|Grewal|2001|p=13}} | |||

| Satish Chandra cautions that this was the "official justification", which historically can be expected to be full of evasion and distortion to justify official action.<ref name=sc2001/> | |||

| Chronicler ], the court historian of ], in his magisterial ''Umdat ut Tawarikh'' (c. 1805) chose to reiterate Ghulam Husain Khan's argument at large: he states that the Guru gained thousands of followers of soldiers and horsemen during his travels between 1672 and 1673 in southern Punjab, essentially having a nomadic army, and provided shelter to rebels who were resistant to Mughal representatives. Aurangzeb was warned about such activity as a cause of concern that could possibly lead to insurrection or rebellion and to eliminate the threat of the Guru at the earliest opportunity.<ref name="sur" /><ref name="sc2001" /> | |||

| Another Muslim scholar, Ghulam Muhiuddin Bute Shah wrote his ''Tarikh-i-Punjab'' in 1842,<ref>{{cite book | last=Mir | first=Farina | title=The social space of language vernacular culture in British colonial Punjab | publisher=University of California Press | location=Berkeley | year=2010 | isbn=978-0-520-26269-0 | page=36}}</ref> over a century and half after the death of Guru Tegh Bahadur, saying that there was ongoing hostility from Ram Rai, the elder brother of Guru Har Kishan, against Guru Tegh Bahadur. Ghulam Muhiuddin Bute Shah said that "Ram Rai represented to the Emperor that Guru Tegh Bahadur was very proud of his spiritual greatness and that he would not realise his fault unless he was punished. Ram Rai also suggested that Guru Tegh Bahadur be asked to appear before the Emperor to work a miracle, if he failed, he could be put to death." Satish Chandra and others say that this account is also doubtful as to the circumstances or cause of Guru Tegh Bahadur's execution.<ref name=sc2001/><ref>{{cite book|last=Mir|first=Farina|title=The social space of language vernacular culture in British colonial Punjab|publisher=University of California Press|location=Berkeley|year=2010|isbn=978-0-520-26269-0|pages=207–37}}</ref> | |||

| Chandra writes that in contrast to this dominating theme in Sikh literature, some pre-modern Sikh accounts had laid the blame on an acrimonious succession dispute: Ram Rai, elder brother of ], was held to have instigated Aurangzeb against Tegh Bahadur by suggesting that he prove his spiritual greatness by performing miracles at the Court.<ref name="sc2001" />{{Efn|Ghulam Muhiuddin Bute Shah in his ''Tarikh- i-Punjab'' reiterates this narrative.}} | |||

| Sikh historians record that Guru Tegh Bahadur had become a socio-political challenge to the Muslim rule and Aurangzeb.<ref name=cs2013>{{cite book|last=Seiple|first=Chris|title=The Routledge handbook of religion and security|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|year=2013|isbn=978-0-415-66744-9|page=96}}</ref> The Sikh movement was rapidly growing in the rural Malwa region of Punjab, and the Guru was openly encouraging Sikhs to, "be fearless in their pursuit of just society: he who holds none in fear, nor is afraid of anyone, is acknowledged as a man of true wisdom", a statement recorded in Adi Granth 1427.<ref name=cs2013/><ref name=pslf/> While Guru Tegh Bahadur influence was rising, Aurangzeb had imposed Islamic laws, demolished ] schools and temples, and enforced new taxes on non-Muslims.<ref name=bbcgtb/><ref name=pslf/><ref name=nsxviii/> | |||

| ] | |||

| === Scholarly analysis === | |||

| The main substantive record however comes from Guru Tegh Bahadur's son, Guru Gobind Singh in his composition, Bachittar Natak. This composition is recited in every Sikh place of workshop on the occasion of the Guru's martyrdom. According to records written by his son Guru Gobind Singh, the Guru had resisted persecution, adopted and promised to protect Kashmiri Hindus.<ref name=cs2013/><ref name=sg2007>{{cite book|last=Gandhi|first=Surjit|title=History of Sikh gurus retold|publisher=Atlantic Publishers|year=2007|isbn=978-81-269-0858-5|pages=653–91}}</ref> The Guru was summoned to Delhi by Aurangzeb on a pretext, but when he arrived, he was offered, "to abandon his faith, and convert to Islam".<ref name=cs2013/><ref name=sg2007/> Guru Tegh Bahadur refused, he and his associates were arrested. He was executed on 11 November 1675 before public in Chandni Chowk, Delhi.<ref name=pslf>{{cite book|author=Pashaura Singh and Louis Fenech|title=The Oxford handbook of Sikh studies|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, UK|year=2014|isbn=978-0-19-969930-8|pages=236–445}}</ref><ref name=sg2007/> | |||

| Satish Chandra expresses doubt about the authenticity of these meta-narratives, centered on miracles — Aurangzeb was not a believer in them, according to Chandra. He further expresses doubt pertaining to the narrative of the persecution of Hindus in Kashmir within Sikh accounts, remarking that no contemporary sources mentioned the persecution of Hindus there.<ref name="ha" /><ref name="sc2001" /><ref>{{cite book|last=Mir|first=Farina|url=https://archive.org/details/socialspacelangu00mirf|title=The social space of language vernacular culture in British colonial Punjab|publisher=University of California Press|year=2010|isbn=978-0-520-26269-0|location=Berkeley|pages=–37|url-access=limited}}</ref> | |||

| Louis E. Fenech refuses to pass any judgement, in light of the paucity of primary sources; however, he notes that these Sikh accounts had coded martyrdom into the events, with an aim to elicit pride rather than trauma in readers. He further argues that Tegh Bahadur sacrificed himself for the sake of his own faith, saying that the ''janju'' and ''tilak'' mentioned in a passage in the Bachittar Natak refer to Tegh Bahadur's own sacred thread and frontal mark.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite book|last=Fenech|first=Louis E.|title=The Sikh Ẓafar-nāmah of Guru Gobind Singh: A Discursive Blade in the Heart of the Mughal Empire|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2013|isbn=9780199931439|pages=108|chapter=The Historiography of the Ẓafar-nāmah}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Grewal |first=J. S. |title=Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708): Master of the White Hawk |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2020 |isbn=9780199494941 |chapter=New Perspectives and Sources |quote=Fenech argues that the twentieth-century Tat Khalsa wrongly treated the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur as a sacrifice to save Hinduism. In his view, the tilak and janju in the passage under consideration refer to the frontal mark and the sacred thread of Guru Tegh Bahadur himself. In other words, Guru Tegh Bahadur sacrificed his life for the sake of his own faith.}}</ref> | |||

| William Irvine states that Guru Tegh Bahadur was tortured for many weeks while being asked to abandon his faith and convert to Islam; he stood by his convictions and refused, he was then executed.<ref>{{cite book|title=Later Mughals|author=William Irvine|publisher=Harvard Press|isbn= 9781290917766|year=2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Siṅgha|first=Kirapāla|title=Select documents on Partition of Punjab-1947|publisher=National Book|year=2006|isbn=978-81-7116-445-5|page=234}}</ref> | |||

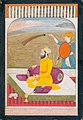

| ] notes that Tegh Bahadur's familial ties to Dara Shikoh (Aurangzeb summoned both Guru Har Rai and later Guru Har Krishan to his court to account for their rumored support to Shikoh), along with his proselytization and being a military organizer, invoked both political and Islamic justifications for the execution.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Metcalf |first1=Barbara D. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jGCBNTDv7acC&pg=PA21 |title=A Concise History of India |last2=Metcalf |first2=Thomas R. |date=2002 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-63974-3 |pages=21 |language=en}}</ref>] sitting on his throne, receiving the news of the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur and the Guru’s companions, ] and ] at Delhi’s ]. Painting by Basahatullah, court painter of the ] of ], circa 19th century.]] | |||

| Sikh tradition teaches that the associates of the Guru were also tortured for refusing to convert: Bhai Mati Das was sawed into pieces and Bhai Dayal Das was thrown into a cauldron of boiling water, while Guru Tegh Bahadur was held inside a cage to watch his colleagues suffer.<ref>{{cite book|last=Singh|first=Prithi|title=The history of Sikh gurus|publisher=Lotus Press|year=2006|isbn=978-81-8382-075-2|page=124}}</ref> The Guru himself was beheaded in public.<ref>{{cite book|author=SS Kapoor|title=The Sloaks of Guru Tegh Bahadur & The Facts About the Text of Ragamala|isbn=978-81-7010-371-4|pages=18–19}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Gandhi|first=Surjit|title=History of Sikh gurus retold|publisher=Atlantic Publishers|year=2007|isbn=978-81-269-0858-5|page=690}}</ref> | |||

| == |

==Legacy and memorials== | ||

| ], Delhi|300x300px]] | |||

| Guru Tegh Bahadur composed 116 hymns in 15 '']'' (musical measures),<ref name="mk37" /> and these were included in the ] (pages 219–1427) by his son, Guru Gobind Singh.<ref name="mahalla">{{cite book |author=Tegh Bahadur (Translated by Gopal Singh) |title=Mahalla nawan: compositions of Guru Tegh Bahādur-the ninth guru (from Sri Guru Granth Sahib): Bāṇī Gurū Tega Bahādara |publisher=Allied Publishers |year=2005 |isbn=978-81-7764-897-3 |pages=xxviii–xxxiii, 15–27}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Singh |first=Prithi |title=The history of Sikh gurus |publisher=Lotus Press |year=2006 |isbn=978-81-8382-075-2 |page=170}}</ref> They cover a wide range of spiritual topics, including human attachments, the body, the mind, sorrow, dignity, service, death, and deliverance.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-11-23 |title=Guru Tegh Bahadur's Martyrdom Day 2022: 8 powerful quotes by the ninth Sikh Guru |url=https://www.hindustantimes.com/lifestyle/festivals/guru-tegh-bahadur-s-martyrdom-day-2022-8-powerful-quotes-by-the-ninth-sikh-guru-101669217215300.html |access-date=2022-11-24 |website=Hindustan Times |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Guru Tegh Bahadur built the city of Anandpur Sahib and was responsible for saving a faction of ], who were being persecuted by the Mughals.<ref name="pslf">{{cite book|author=Pashaura Singh and Louis Fenech|title=The Oxford handbook of Sikh studies|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2014|isbn=978-0-19-969930-8|location=Oxford, UK|pages=236–245, 444–446, Quote: "This second martyrdom helped to make 'human rights and freedom of conscience' central to its identity." Quote: "This is the reputed place where several Kashmiri Pandits came seeking protection from Aurangzeb's army."}}</ref><ref name="cs2013" /> | |||

| ===Legacy and memorials=== | |||

| ], Delhi]] | |||

| ] was Guru Tegh Bahadur's father. He was originally named ''Tyag Mal'' ({{lang-pa|ਤਿਆਗ ਮਲ}}) but was later renamed ''Tegh Bahadur'' after his gallantry and bravery in the wars against the Mughal forces. He built the city of Anandpur Sahib, and was responsible for saving the ], who were being persecuted by the Mughals.<ref name=pslf/> | |||

| After the execution of Guru Tegh |

After the execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, a number of Sikh ] were built in his and his associates' memory. The ] in ], Delhi, was built over where he was beheaded.<ref name="skc">SK Chatterji (1975), Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur and the Sis Ganj Gurdwara, Sikh Review, 23(264): 100–09</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite web |last=John |first=Rachel |date=2019-11-24 |title=Guru Tegh Bahadur — the ninth Sikh guru who sacrificed himself for religious freedom |url=https://theprint.in/theprint-profile/guru-tegh-bahadur-the-ninth-sikh-guru-who-sacrificed-himself-for-religious-freedom/324938/ |access-date=2023-01-25 |website=ThePrint |language=en-US}}</ref> ], also in Delhi, is built where one of Guru Tegh Bahadur's disciples burned his house down to cremate the Guru's body.<ref name="singharakab" /><ref name=":4" /> | ||

| Gurdwara Sisganj Sahib in Punjab marks the site where in November 1675, the head of the martyred Guru |

Gurdwara Sisganj Sahib in Punjab marks the site where, in November 1675, the head of the martyred Guru Tegh Bahadur was cremated after being brought there by Bhai Jaita (renamed ] according to ]) in defiance of the Mughal authority of Aurangzeb.<ref>Harbans Singh (1992), "History of Gurdwara Sis Ganj Sahib", in ''Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Volume 1'', pg. 547</ref> | ||

| The execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur hardened the resolve of Sikhs against Muslim rule and persecution. Pashaura Singh states that "if the martyrdom of ] had helped bring the Sikh Panth together, Guru Tegh Bahadur's martyrdom helped to make the protection of human rights central to its ] identity".<ref name="cs2013" /> Wilfred Smith stated that "the attempt to forcibly convert the ninth Guru to an externalized, impersonal Islam clearly made an indelible impression on the martyr's nine-year-old son, Gobind, who reacted slowly but deliberately by eventually organizing the Sikh group into a distinct, formal, symbol-patterned community". It inaugurated the Khalsa identity.<ref name="ws1981">{{cite book |author=Wilfred Smith |url=https://archive.org/details/onunderstandingi0000smit/page/191 |title=On Understanding Islam: Selected Studies |publisher=Walter De Gruyter |year=1981 |isbn=978-9027934482 |page=}}</ref> | |||

| Guru Tegh Bahadur has been remembered for giving up his life for freedom of religion, reminding Sikhs and non-Muslims in India to follow and practice their beliefs without fear of persecution and forced conversions by Muslims.<ref name=cs2013/><ref name=pslf/> Guru Tegh Bahadur was martyred, along with fellow devotees ], ] and ].<ref name=bbcgtb/> ], the date of his martyrdom, is celebrated in certain parts of India as a public holiday.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dnh.nic.in/Docs/14Dec2015/HolidayNotification2016.pdf|format=PDF|title=Letter from Administration of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, U.T.|website=Dnh.nic.in|accessdate=20 October 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://arunachalipr.gov.in/GH_Restricted.htm|title=LIST OF RESTRICTED HOLIDAYS 2016|website=Arunachalipr.gov.in|accessdate=20 October 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://himachal.nic.in/en-IN/holidays-2016.html|title=HP Government - Holidays - Government of Himachal Pradesh, India|website=Himachal.nic.in|date=13 June 2016|accessdate=20 October 2016}}</ref> | |||

| In one of his poetic works, the classical Punjabi poet ], referred to Guru Tegh Bahadur as "]", an honorific title for a warrior.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bullhe Shāh,?-1758? |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1240164691 |title=Sufi lyrics |date=2015 |others=C. Shackle, Inc OverDrive |isbn=978-0-674-25966-9 |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |oclc=1240164691}}</ref> | |||

| ===Effect on Sikhs=== | |||

| The execution hardened the resolve of Sikhs against Muslim rule and the persecution. Pashaura Singh states that, "if the martyrdom of ] had helped bring the Sikh Panth together, Guru Tegh Bahadur's martyrdom helped to make the protection of human rights central to its ] identity".<ref name=cs2013/> Wilfred Smith<ref name=ws1981/> states that, "the attempt to forcibly convert the ninth Guru to an externalized, impersonal Islam clearly made an indelible impression on the martyr's nine year old son, Gobind, who reacted slowly but deliberately by eventually organizing the Sikh group into a distinct, formal, symbol-patterned community". It inaugurated the Khalsa identity.<ref name=ws1981>{{cite book|author=Wilfred Smith|year=1981|page=191|title=On Understanding Islam: Selected Studies|publisher=Walter De Gruyter|isbn=978-9027934482}}</ref> | |||

| In India, 24 November is observed as Guru Tegh Bahadur's Martyrdom Day (''Shaheedi Diwas'').<ref>{{Cite web |last=NEWS |first=SA |date=2022-11-24 |title=Guru Tegh Bahadur Martyrdom Day 2022: Revelation From Guru Granth Sahib Ji |url=https://news.jagatgururampalji.org/guru-tegh-bahadur-martyrdom-day/ |access-date=2022-11-24 |website=SA News Channel |language=en-US}}</ref> In certain parts of India, this day of the year is a public holiday.<ref>{{cite web |title=Letter from Administration of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, U.T. |url=http://www.dnh.nic.in/Docs/14Dec2015/HolidayNotification2016.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160806124235/http://www.dnh.nic.in/Docs/14Dec2015/HolidayNotification2016.pdf |archive-date=6 August 2016 |access-date=20 October 2016 |website=Dnh.nic.in}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=LIST OF RESTRICTED HOLIDAYS 2016 |url=http://arunachalipr.gov.in/GH_Restricted.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161108090922/http://arunachalipr.gov.in/GH_Restricted.htm |archive-date=8 November 2016 |access-date=20 October 2016 |website=Arunachalipr.gov.in}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=13 June 2016 |title=HP Government – Holidays – Government of Himachal Pradesh, India |url=http://himachal.nic.in/en-IN/holidays-2016.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161101172904/http://himachal.nic.in/en-IN/holidays-2016.html |archive-date=1 November 2016 |access-date=20 October 2016 |website=Himachal.nic.in}}</ref> Guru Tegh Bahadur is remembered for giving up his life to protect the freedom of the oppressed to practice their own religion.<ref name="pslf" /><ref name="cs2013" /><ref name="bbcgtb" /> | |||

| ==Places named after Guru Teg Bahadur== | |||

| A number of places are named after the ninth guru of Sikhs, Guru Teg Bahadur. | |||

| == Gallery == | |||

| {{div col|3}} | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| * Shri guru Teg Bahadur Senior Secondary School, PATLI DABAR, Sirsa (Haryana) | |||

| File:Guru Tegh Bahadur, fresco from Qila Mubarak.jpg|Guru Tegh Bahadur, fresco from Qila Mubarak. | |||

| File:Portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur in the Pahari style.jpg|Portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur in the Pahari style. | |||

| * Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, ] | |||

| File:Guru Tegh Bahadur, the Ninth Sikh Guru.jpg|18th century painting of Guru Tegh Bahadur. | |||

| * Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Khalsa Institute of Engineering & Technology, ] | |||

| File:A 19th century painting depicting Guru Tegh Bahadur.jpg|19th century painting depicting Guru Tegh Bahadur. | |||

| * Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Institute of Technology | |||

| File:Guru Tegh Bahadur, Pahari painting.png|Guru Tegh Bahadur, Pahari painting. Gouache on paper. | |||

| * Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Integration Chair, ], ] | |||

| File:Guru Tegh Bahadur painting from the family workshop of Nainsukh of Guler.jpg|Guru Tegh Bahadur painting from the family workshop of Nainsukh of Guler. | |||

| * Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Railway Station, ] (G.T.B. Nagar) | |||

| File:Portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur.jpg|Portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur from the last quarter of the 19th century. | |||

| * Guru Teg Bahadur Public School, ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Gurudwara Sri Guru Tegh Bahadar Langar Saheb, ] | |||

| * Sri Guru Tegh Bahadar English High School, Aurangabad, Maharashtra | |||

| * Sri Guru Teg Bahadur Khalsa Collge (SGTB Khalsa Collge), University of Delhi | |||

| * Guru Tegh bahadur 3rd centenary public school, New Delhi | |||

| * Guru Teg Bahadur Charitable Hospital, Ludhiana | |||

| * Guru Teg Bahadur Public School, Patran (District Patiala) | |||

| * Gurudwara Sahib, Sri Guru Teg bahadur Nagar, Jalandhar (Punjab) | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{ |

{{Notelist}} | ||

| <!-- publishing info, years, ISSN/ISBN #s, etc needed --> | |||

| *''Shri Guru Teg Bahadur Education Society Patli Dabar, Sirsa' (Haryana) | |||

| *Gokalchand Narang; ''Transformation of Sikhism'' | |||

| *Puran Singh; ''The book of Ten Masters'' | |||

| *N.K Sinha; ''Rise of Sikh Panth'' | |||

| *Teja Singh Ganda Singh; ''A Short History of the Sikhs''. | |||

| *Guru Tegh Bahadur; Commemorative Volume''. Editor: Satbir Singh. Publisher: Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur Tercentenary Martyrdom Gurpurab Committee. Government of India (1975) | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Wikiquote}} | |||

| {{Portal|India|Biography|Sikhism|Punjab}} | |||

| {{Portal|India|Biography|Punjab}} | |||

| ;Peer reviewed publications on Guru Tegh Bahadur | ;Peer reviewed publications on Guru Tegh Bahadur | ||

| * Ranbir Singh (1975) | |||

| *, Louis E. Fenech, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 117(4): 623-42, (Oct-Dec, 1997) | |||

| *, Jeevan Singh Deol, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 121(2): 193–203, (Apr. – Jun., 2001) | |||

| * Ranbir Singh (1975) | |||

| *, Jeevan Singh Deol, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 121(2): 193-203, (Apr. - Jun., 2001) | |||

| ;Other links | |||

| {{col div|2}} | |||

| * Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur is the ninth of the Ten Sikh Gurus. Read about his life and stories here. | |||

| *{{dead link|date=November 2016 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{col div end}} | |||

| {{s-start}} | {{s-start}} | ||

| {{succession box | {{succession box | ||

| | before = ] | | before = ] | ||

| | title = ]|years=20 March 1665 |

| title = ]|years=20 March 1665 – 24 November 1675 | ||

| | after = ] | | after = ] | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| Line 175: | Line 149: | ||

| {{Guru Gobind Singh}} | {{Guru Gobind Singh}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | {{Authority control}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Bahadur, Guru Tegh}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Bahadur, Guru Tegh}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:03, 20 January 2025

Ninth Sikh guru from 1665 to 1675| Guru Tegh Bahadur | |

|---|---|

| ਗੁਰੂ ਤੇਗ਼ ਬਹਾਦਰ | |

A mid-17th-century portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur painted by Ahsan, the viceregal painter of Shaista Khan, governor of Bengal, circa 1668–69 A mid-17th-century portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur painted by Ahsan, the viceregal painter of Shaista Khan, governor of Bengal, circa 1668–69 | |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Tyag Mal 1 April 1621 (1621-04) Amritsar, Lahore Subah, Mughal Empire (present-day Punjab, India) |

| Died | 11 November 1675 (1675-11-12) (aged 54) Delhi, Mughal Empire (present-day India) |

| Cause of death | Execution by decapitation |

| Spouse | Mata Gujri |

| Children | Guru Gobind Singh |

| Parent(s) | Guru Hargobind and Mata Nanaki |

| Known for |

|

| Other names | Ninth Master Ninth Nanak Srisht-di-Chadar ("Shield of The World") Dharam-di-Chadar ("Shield of Dharma") Hind-di-Chadar ("Shield of India") |

| Signature |  |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Sikhism |

| Religious career | |

| Period in office | 1664–1675 |

| Predecessor | Guru Har Krishan |

| Successor | Guru Gobind Singh |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | Early Mughal-Sikh Wars Battle of Kartarpur (1635) Skirmish Of Dhubri (1669) |

Guru Tegh Bahadur (Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਤੇਗ਼ ਬਹਾਦਰ (Gurmukhi); Punjabi pronunciation: [gʊɾuː t̯eːɣ bəɦaːd̯ʊɾᵊ]; 1 April 1621 – 11 November 1675) was the ninth of ten gurus who founded the Sikh religion and was the leader of Sikhs from 1665 until his beheading in 1675. He was born in Amritsar, Punjab, India in 1621 and was the youngest son of Guru Hargobind, the sixth Sikh guru. Considered a principled and fearless warrior, he was a learned spiritual scholar and a poet whose 115 hymns are included in the Guru Granth Sahib, which is the main text of Sikhism.

Tegh Bahadur was executed on the orders of Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal emperor, in Delhi, India. Sikh holy premises Gurudwara Sis Ganj Sahib and Gurdwara Rakab Ganj Sahib in Delhi mark the places of execution and cremation of Guru Tegh Bahadur. His day of martyrdom (Shaheedi Divas) is commemorated in India every year on 24 November.

Biography

Early life

Guru Tegh Bahadur was born Tyag Mal (Tīāg Mal) (Punjabi: ਤਿਆਗ ਮਲ) in Amritsar on 1 April 1621. He was the youngest son of Guru Hargobind, the sixth guru. His family belonged to the Sodhi clan of Khatris. Hargobind had one daughter, Bibi Viro, and five sons: Baba Gurditta, Suraj Mal, Ani Rai, Atal Rai, and Tyag Mal. He gave Tyag Mal the name Tegh Bahadur (Brave Sword) after Tyag Mal showed valor in the Battle of Kartarpur against the Mughals.

Tegh Bahadur was brought up in the Sikh culture and trained in archery and horsemanship. He was also taught the old classics such as the Vedas, the Upanishads, and the Puranas. He was married on 3 February 1632 to Gujri.

In the 1640s, nearing his death, Guru Hargobind and his wife Nanaki moved to his ancestral village of Bakala in Amritsar district, together with Tegh Bahadur and Gujri. After Hargobind's death, Tegh Bahadur continued to live in Bakala with his wife and mother.

Installation as Guru of Sikhs

In March 1664, Guru Har Krishan contracted smallpox. When his followers asked who would lead them after him, he said, "Baba Bakala", meaning his successor was to be found in Bakala. Taking advantage of the ambiguity in the words of the dying guru, many installed themselves in Bakala, claiming to be the new guru. Sikhs were puzzled to see so many claimants.

Sikh tradition has a legend about how Tegh Bahadur was selected as the ninth guru. A wealthy trader named Makhan Shah Labana had vowed to give 500 gold coins to the Sikh Guru upon escaping a shipwreck some time ago, and he came to Bakala in search of the ninth guru. He met each claimant he could find, making his obeisance and offering them two gold coins in the belief that the right guru would know of his silent promise to give them 500 coins. Every "guru" he met accepted the two gold coins and bid him farewell. Then he discovered that Tegh Bahadur also lived at Bakala. Makhan Shah gave Tegh Bahadur the usual offering of two gold coins. Tegh Bahadur blessed him and remarked that his offering was short of the promised five hundred. Makhan Shah made good the difference and ran upstairs. He began shouting from the rooftop, "Guru ladho re, Guru ladho re", meaning "I have found the Guru, I have found the Guru".

In August 1664, a Sikh congregation led by Diwan Dargha Mal, son of a well-known devotee of Har Krishan, arrived in Bakala and appointed Tegh Bahadur as the ninth guru of Sikhs.

As had been the custom among Sikhs after the execution of Guru Arjan by Mughal Emperor Jahangir, Guru Tegh Bahadur was surrounded by armed bodyguards, but he otherwise lived an austere life.

Journeys

Guru Tegh Bahadur traveled extensively in different parts of the Indian subcontinent, including Dhaka and Assam, to preach the teachings of Guru Nanak, the first Sikh guru. The places he visited and stayed in became sites of Sikh temples. During his travels, he started a number of community water wells and langars (community kitchens for the poor).

Tegh Bahadur visited the towns of Mathura, Agra, Allahabad and Varanasi. His son, Guru Gobind Singh, who would be the tenth Sikh guru, was born in Patna in 1666 while he was away in Dhubri, Assam, where the Gurdwara Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur Sahib now stands. While in Assam, it is claimed by Sikh accounts that the guru brokered peace between Raja Ram Singh and the Ahom ruler Raja Chakradhwaj Singha (Supangmung).

After his visit to Assam, Bengal, and Bihar, Guru Tegh Bahadur visited Rani Champa of Bilaspur, who offered to give the Guru a piece of land in her state. The Guru bought the site for 500 rupees. There, he founded the city of Anandpur Sahib in the foothills of the Himalayas. In 1672, Tegh Bahadur traveled in and around the Malwa region to meet the masses as the persecution of non-Muslims reached new heights.

Execution

Narrative

Many scholars identify the traditional Sikh narrative as follows: A congregation of Hindu Pandits from Kashmir requested help against Aurangzeb's persecutions and oppressive policies, and Guru Tegh Bahadur decided to protect their rights. According to Trilochan Singh in Guru Tegh Bahadur: Prophet and Martyr, the convoy of Kashmiri Pandits who tearfully pleaded with the Guru at Anandpur were 500 in number and were led by a certain Pandit Kirpa Ram, who recounted tales of religious oppression under the governorship of Iftikhar Khan. The Kashmiri Pandits decided to meet with the Guru after they first sought the assistance of Shiva at the Amarnath shrine, where one of them is said to have had a dream where Shiva instructed the Pandits to seek out the ninth Sikh guru for assistance in their plight and hence a group was formed for carrying out the task. Guru Tegh Bahadur left from his base at Makhowal to confront the persecution of Kashmiri Pandits by Mughal officials but was arrested at Ropar and put to jail in Sirhind. Four months later, in November 1675, he was transferred to Delhi and asked to perform a miracle to prove his nearness to God or convert to Islam. The Guru declined, and three of his colleagues, who had been arrested with him, were tortured to death in front of him: Bhai Mati Das was sawn in two, Bhai Dayal Das was thrown into a cauldron of boiling liquid, and Bhai Sati Das was cut into pieces. Thereafter on 11 November, Tegh Bahadur was publicly beheaded in Chandni Chowk, a market square close to the Red Fort.

Historiography

The primary nucleus of Sikh narratives remains the Bachittar Natak, a memoir of Guru Gobind Singh, Guru Tegh Bahadur's son, dated between late 1680s and late 1690s. Guru Tegh Bahadur's son and successor recalled the Guru's execution:

In this dark age, Tegh Bahadur performed a great act of chivalry (saka) for the sake of the frontal mark and sacred thread. He offered all he had for the holy. He gave up his head, but did not utter a sigh. He suffered martyrdom for the sake of religion. He laid down his head, but not his honor. Real men of God do not perform tricks like showmen. Having broken the pitcher on the head of the Emperor of Delhi, he departed to the world of God. No one has ever performed a deed like him. At his departure, the whole world mourned, while the heavens hailed it as a victory.

— Guru Gobind Singh, Bachittar Natak: Apni Katha

More Sikh accounts of Guru Tegh Bahadur's execution, all claiming to be sourced from the "testimony of trustworthy Sikhs", only started emerging in around the late eighteenth century, and are thus, often conflicting, according to historian Satish Chandra.

Persian and non Sikh sources maintain that the Guru was a bandit whose plunder and rapine of Punjab along with his rebellious activities precipitated his execution. According to Chandra, the earliest Persian source to chronicle his execution is Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin by Ghulam Husain Khan c. 1782, where Tegh Bahadur's (alleged) oppression of subjects is held to have incurred Aurangzeb's wrath:

Tegh Bahadur, the eighth successor of (Guru) Nanak became a man of authority with a large number of followers. (In fact) several thousand persons used to accompany him as he moved from place to place. His contemporary Hafiz Adam, a faqir belonging to the group of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi's followers, had also come to have a large number of murids and followers. Both these men (Guru Tegh Bahadur and Hafiz Adam) used to move about in Punjab, adopting a habit of coercion and extortion. Tegh Bahadur used to collect money from Hindus and Hafiz Adam from Muslims. The royal waqia navis (news reporter and intelligence agent) wrote to the Emperor Alamgir ... of their manner of activity, adding that if their authority increased they could become even refractory.

— Ghulam Husain, Siyar-ul-Mutakhkherin

Chandra cautions against taking Ghulam Husain's argument at face value, as Ghulam Husain was a relative of Alivardi Khan — one of the closest confidantes of Aurangzeb — and might have been providing an "official justification". Also, the Guru's alleged association with Hafiz Adam is anachronistic. Chandra further writes that Ghulam Husain's account places Guru Tegh Bahadur's confinement and execution in Lahore, while Sikh tradition places it in Delhi, and Chandra finds no reason to reject said tradition.

The Sikh sakhis (traditional accounts) written during the eighteenth century indirectly support the narrative in the Persian sources, saying that "the Guru was in violent opposition to the Muslim rulers of the country" in response to the dogmatic policies implemented by Aurangzeb. Both Persian and Sikh sources agree that Guru Tegh Bahadur militarily opposed the Mughal state and was therefore targeted for execution in accordance with Aurangzeb's zeal for punishing enemies of the state.

Bhimsen, a contemporary chronicler of Guru Gobind Singh, wrote (c.1708) that the successors of Guru Nanak maintained extravagant lifestyles, and some of them, including Tegh Bahadur, rebelled against the state: Tegh Bahadur proclaimed himself Padshah and acquired a large following, as a result, Aurangzeb had him executed. Muhammad Qasim's Ibratnama, written in 1723, claimed Tegh Bahadur's religious inclinations along with his life of splendor and conferral of sovereignty by his followers had him condemned and executed.

Chronicler Sohan Lal Suri, the court historian of Ranjit Singh, in his magisterial Umdat ut Tawarikh (c. 1805) chose to reiterate Ghulam Husain Khan's argument at large: he states that the Guru gained thousands of followers of soldiers and horsemen during his travels between 1672 and 1673 in southern Punjab, essentially having a nomadic army, and provided shelter to rebels who were resistant to Mughal representatives. Aurangzeb was warned about such activity as a cause of concern that could possibly lead to insurrection or rebellion and to eliminate the threat of the Guru at the earliest opportunity.

Chandra writes that in contrast to this dominating theme in Sikh literature, some pre-modern Sikh accounts had laid the blame on an acrimonious succession dispute: Ram Rai, elder brother of Guru Har Krishan, was held to have instigated Aurangzeb against Tegh Bahadur by suggesting that he prove his spiritual greatness by performing miracles at the Court.

Scholarly analysis

Satish Chandra expresses doubt about the authenticity of these meta-narratives, centered on miracles — Aurangzeb was not a believer in them, according to Chandra. He further expresses doubt pertaining to the narrative of the persecution of Hindus in Kashmir within Sikh accounts, remarking that no contemporary sources mentioned the persecution of Hindus there.

Louis E. Fenech refuses to pass any judgement, in light of the paucity of primary sources; however, he notes that these Sikh accounts had coded martyrdom into the events, with an aim to elicit pride rather than trauma in readers. He further argues that Tegh Bahadur sacrificed himself for the sake of his own faith, saying that the janju and tilak mentioned in a passage in the Bachittar Natak refer to Tegh Bahadur's own sacred thread and frontal mark.

Barbara Metcalf notes that Tegh Bahadur's familial ties to Dara Shikoh (Aurangzeb summoned both Guru Har Rai and later Guru Har Krishan to his court to account for their rumored support to Shikoh), along with his proselytization and being a military organizer, invoked both political and Islamic justifications for the execution.

Legacy and memorials

Guru Tegh Bahadur composed 116 hymns in 15 ragas (musical measures), and these were included in the Guru Granth Sahib (pages 219–1427) by his son, Guru Gobind Singh. They cover a wide range of spiritual topics, including human attachments, the body, the mind, sorrow, dignity, service, death, and deliverance.

Guru Tegh Bahadur built the city of Anandpur Sahib and was responsible for saving a faction of Kashmiri Pandits, who were being persecuted by the Mughals.

After the execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, a number of Sikh gurudwaras were built in his and his associates' memory. The Gurdwara Sis Ganj Sahib in Chandni Chowk, Delhi, was built over where he was beheaded. Gurdwara Rakab Ganj Sahib, also in Delhi, is built where one of Guru Tegh Bahadur's disciples burned his house down to cremate the Guru's body.

Gurdwara Sisganj Sahib in Punjab marks the site where, in November 1675, the head of the martyred Guru Tegh Bahadur was cremated after being brought there by Bhai Jaita (renamed Bhai Jiwan Singh according to Sikh rites) in defiance of the Mughal authority of Aurangzeb.

The execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur hardened the resolve of Sikhs against Muslim rule and persecution. Pashaura Singh states that "if the martyrdom of Guru Arjan had helped bring the Sikh Panth together, Guru Tegh Bahadur's martyrdom helped to make the protection of human rights central to its Sikh identity". Wilfred Smith stated that "the attempt to forcibly convert the ninth Guru to an externalized, impersonal Islam clearly made an indelible impression on the martyr's nine-year-old son, Gobind, who reacted slowly but deliberately by eventually organizing the Sikh group into a distinct, formal, symbol-patterned community". It inaugurated the Khalsa identity.

In one of his poetic works, the classical Punjabi poet Bulleh Shah, referred to Guru Tegh Bahadur as "Ghazi", an honorific title for a warrior.

In India, 24 November is observed as Guru Tegh Bahadur's Martyrdom Day (Shaheedi Diwas). In certain parts of India, this day of the year is a public holiday. Guru Tegh Bahadur is remembered for giving up his life to protect the freedom of the oppressed to practice their own religion.

Gallery

-

Guru Tegh Bahadur, fresco from Qila Mubarak.

Guru Tegh Bahadur, fresco from Qila Mubarak.

-

Portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur in the Pahari style.

Portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur in the Pahari style.

-

18th century painting of Guru Tegh Bahadur.

18th century painting of Guru Tegh Bahadur.

-

19th century painting depicting Guru Tegh Bahadur.

19th century painting depicting Guru Tegh Bahadur.

-

Guru Tegh Bahadur, Pahari painting. Gouache on paper.

Guru Tegh Bahadur, Pahari painting. Gouache on paper.

-

Guru Tegh Bahadur painting from the family workshop of Nainsukh of Guler.

Guru Tegh Bahadur painting from the family workshop of Nainsukh of Guler.

-

Portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur from the last quarter of the 19th century.

Portrait of Guru Tegh Bahadur from the last quarter of the 19th century.

Notes

- The authorship is disputed. While W. H. McLeod considered the work to be Guru Gobind Singh's, Gurinder Singh Mann and Purnima Dhavan concluded it to be the work of multiple court poets; there is a rough consensus to date the text.

- Ghulam Muhiuddin Bute Shah in his Tarikh- i-Punjab reiterates this narrative.

References

- ^ Pashaura Singh and Louis Fenech (2014). The Oxford handbook of Sikh studies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 236–245, 444–446, Quote: "This second martyrdom helped to make 'human rights and freedom of conscience' central to its identity." Quote: "This is the reputed place where several Kashmiri Pandits came seeking protection from Aurangzeb's army.". ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Gill, Sarjit S., and Charanjit Kaur (2008), "Gurdwara and its politics: Current debate on Sikh identity in Malaysia", SARI: Journal Alam dan Tamadun Melayu, Vol. 26 (2008), pages 243–255, Quote: "Guru Tegh Bahadur died in order to protect the freedom of India from invading Mughals."

- ^ Seiple, Chris (2013). The Routledge handbook of religion and security. New York: Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-415-66744-9.

- Gandhi, Surjit (2007). History of Sikh gurus retold. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 653–91. ISBN 978-81-269-0858-5.

- Singh, Harmeet Shah (21 April 2022). "Explained - The legacy of Guru Teg Bahadar and its revisionism". India Today.

Take for instance, the description of Guru Teg Bahadar as 'Hind di Chadar' in present-day parlance and 'Dharam di Chadar' some 100 years ago. That appears to be a departure from how he was originally described in contemporaneous poetic texts after his execution in 1675. Chandra Sain Sainapati was a court poet of Guru Gobind Singh, the son of Guru Teg Bahadar. In his composition called Sri Gur Sobha, Sainapati described the martyred Guru as 'Srisht ki Chadar', or the protector of humanity. 'Pargat Bhae Gur Teg Bahadar, Sagal Srisht Pe Dhaapi Chadar,' the poet wrote, meaning 'Guru Tegh Bahadar was revealed, and protected the whole creation.'

- W. H. McLeod (1984). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. Manchester University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780719010637. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "The Ninth Master Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675)". sikhs.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ "Religions – Sikhism: Guru Tegh Bahadur". BBC. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 236–238. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 12 June 2017.;

Fenech, Louis E. (2001). "Martyrdom and the Execution of Guru Arjan in Early Sikh Sources". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 121 (1). American Oriental Society: 20–31. doi:10.2307/606726. JSTOR 606726.;

Fenech, Louis E. (1997). "Martyrdom and the Sikh Tradition". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 117 (4). American Oriental Society: 623–642. doi:10.2307/606445. JSTOR 606445.;

McLeod, Hew (1999). "Sikhs and Muslims in the Punjab". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 22 (sup001). Taylor & Francis: 155–165. doi:10.1080/00856408708723379. ISSN 0085-6401. - ^ H. S. Singha (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2016). Sikhism: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 6, 122–123. ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.