| Revision as of 20:09, 3 October 2006 view source149.79.54.95 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:24, 23 January 2025 view source JJMC89 bot III (talk | contribs)Bots, Administrators3,759,505 editsm Removing Category:Species that are or were threatened by human consumption for medicinal or magical purposes per Misplaced Pages:Categories for discussion/Log/2025 January 15#Category:Species that are or were threatened by human consumption for medicinal or magical purposes | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Species of large cat}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{redirect|Tigress|other uses|Tiger (disambiguation)|and|Tigress (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| | color = pink | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| | name = Tiger | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=April 2020}} | |||

| {{Speciesbox | |||

| | fossil_range = {{fossil range|Early Pleistocene | Present}} | |||

| | image = Walking tiger female.jpg | |||

| | image_caption = A ] in ], India | |||

| | image_upright = 1.2 | |||

| | status = EN | | status = EN | ||

| | status_system = IUCN3.1 | |||

| | trend = down | |||

| | status_ref =<ref name=iucn>{{cite iucn |title=''Panthera tigris'' |author=Goodrich, J. |author2=Wibisono, H. |author3=Miquelle, D. |author4=Lynam, A.J |author5=Sanderson, E. |author6=Chapman, S. |author7=Gray, T. N. E. |author8=Chanchani, P. |author9=Harihar, A. |name-list-style=amp |date=2022 |page=e.T15955A214862019 |doi=10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T15955A214862019.en |access-date=31 August 2022}}</ref> | |||

| | status_ref = <ref name="IUCN">{{IUCN2006|assessors=Cat Specialist Group|year=2002|id=15955 era tigris|downloaded=10 May 2006}} Database entry includes justification for why this species is endangered </ref> | |||

| | status2 = CITES_A1 | |||

| | image = Manchuriantig.jpg | |||

| | |

| status2_system = CITES | ||

| | status2_ref = <ref name=iucn/> | |||

| | image_caption = ] (''P. tigris altaica'') | |||

| | taxon = Panthera tigris | |||

| | regnum = ]ia | |||

| | authority = (], 1758)<ref name=Linn1758/> | |||

| | phylum = ] | |||

| | subdivision_ranks = Subspecies | |||

| | classis = ]ia | |||

| | subdivision = | |||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| * '']'' | |||

| | familia = ] | |||

| * '']'' | |||

| | genus = '']'' | |||

| * {{extinct}}'']'' | |||

| | species = '''''P. tigris''''' | |||

| * {{extinct}}'']'' | |||

| * {{extinct}}'']'' | |||

| | binomial_authority = (], ]) | |||

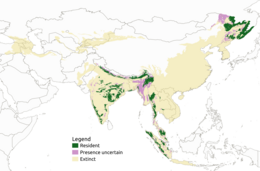

| | range_map = Tiger distribution.png | |||

| | synonyms = | |||

| | range_map_caption = Tiger distribution as of 2022 | |||

| <center>'''''Felis tigris''''' <small>], ]</small><br> | |||

| | range_map_upright = 1.2 | |||

| '''''Tigris striatus''''' <small>], ]</small><br> | |||

| | synonyms = | |||

| '''''Tigris regalis''''' <small>], ]</small></center> | |||

| {{Species list | |||

| | Felis tigris | ], ] | |||

| | Tigris striatus | ], 1858 | |||

| | Tigris regalis | ], 1867 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | synonyms_ref = <ref>{{cite book |first1=J. R. |last1=Ellerman |first2=T. C. S. |last2=Morrison-Scott |name-list-style=amp |date=1951 |title=Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 |location=London |publisher=British Museum |pages=318–319 |chapter=''Panthera tigris'', Linnaeus, 1758 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/checklistofpalae00elle/page/318/mode/2up}}</ref> | |||

| '''Tigers''' ('''''Panthera tigris''''') are ]s of the ] family and one of four "]s" in the '']'' ]. They are ]s and the largest and most powerful living cat species in the world<ref name="bbc">{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/wildfacts/factfiles/19.shtml|title=BBC Wildfacts – Tiger}}</ref><ref></ref>. The ] is the most common subspecies of tiger, constituting approximately 80% of the entire tiger population, and is found in the ]. The tiger's beautiful blend of grace and ferocity led the legendary author and conservationist, ] to remark - "The Tiger is a large hearted gentleman with boundless courage...". | |||

| }} | |||

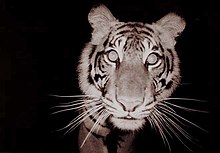

| The '''tiger''' ('''''Panthera tigris''''') is a large ] and a member of the genus '']'' native to ]. It has a powerful, muscular body with a large head and paws, a long tail and orange fur with black, mostly vertical stripes. It is traditionally classified into nine ] ], though some recognise only two subspecies, mainland Asian tigers and the island tigers of the ]. | |||

| Throughout the tiger's range, it inhabits mainly forests, from ]ous and ]s in the ] and ] to ] on the ] and ]. The tiger is an ] and preys mainly on ]s, which it takes by ambush. It lives a mostly solitary life and occupies ]s, defending these from individuals of the same sex. The range of a male tiger overlaps with that of multiple females with whom he mates. Females give birth to usually two or three cubs that stay with their mother for about two years. When becoming independent, they leave their mother's home range and establish their own. | |||

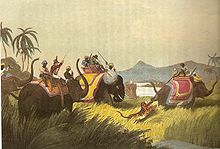

| Since the early 20th century, tiger populations have lost at least 93% of their historic range and are ] in ] and ], in large areas of ] and on the islands of ] and ]. Today, the tiger's range is severely fragmented. It is listed as ] on the ], as its range is thought to have declined by 53% to 68% since the late 1990s. Major threats to tigers are ] and ] due to ], ] for fur and the illegal trade of body parts for medicinal purposes. Tigers are also victims of ] as they attack and prey on livestock in areas where natural prey is scarce. The tiger is legally protected in all range countries. National conservation measures consist of action plans, ] patrols and schemes for monitoring tiger populations. In several range countries, ]s have been established and tiger reintroduction is planned. | |||

| The tiger is among the most popular of the world's ]. It has been kept in captivity since ancient times and has been trained to perform in ]es and other entertainment shows. The tiger featured prominently in the ancient ] and ] of cultures throughout its historic range and has continued to ] worldwide. | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| The ] ''tigras'' derives from ] {{lang|fro|tigre}}, from ] {{lang|la|tigris}}, which was a borrowing from {{transl|grc| tigris}} ({{langx|grc|τίγρις}}).<ref>{{cite book |author1=Liddell, H. G. |author2=Scott, R. |name-list-style=amp |title=A Greek-English Lexicon |edition=Revised and augmented |year=1940 |location=Oxford |publisher=Clarendon Press |chapter=τίγρις |chapter-url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dti%2Fgris |access-date=21 February 2021 |archive-date=21 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201021200154/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0057:entry=ti/gris |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Since ancient times, the word {{transl|grc|tigris}} has been suggested to originate from the ] or ] word for 'arrow', which may also be the origin of the name for the river ].<ref name=Varro>{{cite book |author=Varro, M. T. |translator=Kent, R. G. |year=1938 |title=De lingua latina |trans-title=On the Latin language |publisher=W. Heinemann |place=London |chapter=XX. Ferarum vocabula |trans-chapter=XX. The names of wild beasts |pages=94–97 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/onlatinlanguage01varruoft/page/96/mode/2up}}</ref><ref name=Thorley>{{cite journal |last=Thorley |first=D. |year=2017 |title=Naming the tiger in the Early Modern world |journal=Renaissance Quarterly |volume=70 |issue=3 |pages=977–1006 |doi=10.1086/693884 |jstor=26560471 |s2cid=165388712}}</ref> However, today, the names are thought to be ], and the connection between the tiger and the river is doubted.<ref name=Thorley/> | |||

| == Taxonomy == | |||

| In 1758, ] described the tiger in his work '']'' and gave it the ] ''Felis tigris'', as the genus ''Felis'' was being used for all cats at the time. His ] was based on descriptions by earlier naturalists such as ] and ].<ref name=Linn1758>{{cite book |author=Linnaeus, C. |year=1758 |title=Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis |volume=Tomus I |edition=decima, reformata |location=Holmiae |publisher=Laurentius Salvius |page=41 |chapter=''Felis tigris'' |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/mobot31753000798865#page/41/mode/2up |language=la}}</ref> In 1929, ] placed the species in the genus '']'' using the scientific name ''Panthera tigris''.<ref name=pocock1929>{{cite journal |author=Pocock, R. I. |year=1929 |title=Tigers |journal=Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society |volume=33 |issue=3 |pages=505–541 |url=https://archive.org/details/journalofbomb33341929bomb/page/n133}}</ref><ref name=pocock1939>{{cite book |author=Pocock, R. I. |year=1939 |title=The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma |volume=((Mammalia. Volume 1)) |location=London |publisher=T. Taylor and Francis, Ltd. |pages=197–210 |chapter=''Panthera tigris'' |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/PocockMammalia1/pocock1#page/n247/mode/2up}}</ref> | |||

| === Subspecies === | |||

| {{anchor|Populations}} | |||

| Nine ] tiger ] have been proposed between the early 19th and early 21st centuries, namely the ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]s.<ref name=MSW3>{{MSW3 Carnivora |id=14000259 |page=546 |heading=Species ''Panthera tigris''}}</ref><ref name=Wilting2015/> The ] of several tiger subspecies was questioned in 1999 as most putative subspecies were distinguished on the basis of fur length and colouration, striping patterns and body size of specimens in ] collections that are not necessarily representative for the entire population. It was proposed to recognise only two tiger subspecies as valid, namely ''P. t. tigris'' in mainland Asia and the smaller ''P. t. sondaica'' in the ].<ref name=Kitchener1999>Kitchener, A. (1999). "Tiger distribution, phenotypic variation and conservation issues" in {{harvnb|Seidensticker|Christie|Jackson|1999|pp=19–39}}</ref> | |||

| This two-subspecies proposal was reaffirmed in 2015 through a comprehensive analysis of morphological, ecological and ] (mtDNA) traits of all putative tiger subspecies.<ref name=Wilting2015>{{cite journal |title=Planning tiger recovery: Understanding intraspecific variation for effective conservation |last1=Wilting |first1=A. |last2=Courtiol |first2=A. |first3=P. |last3=Christiansen |first4=J. |last4=Niedballa |first5=A. K. |last5=Scharf |first6=L. |last6=Orlando |first7=N. |last7=Balkenhol |first8=H. |last8=Hofer |first9=S. |last9=Kramer-Schadt |first10=J. |last10=Fickel |first11=A. C. |last11=Kitchener |name-list-style=amp |date=2015 |volume=11 |issue=5 |page=e1400175 |doi=10.1126/sciadv.1400175 |pmid=26601191 |pmc=4640610 |journal=Science Advances |bibcode=2015SciA....1E0175W}}</ref> | |||

| In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group revised ] taxonomy in accordance with the 2015 two-subspecies proposal and recognised only ''P. t. tigris'' and ''P. t. sondaica''.<ref name=catsg>{{cite journal |last1=Kitchener |first1=A. C. |last2=Breitenmoser-Würsten |first2=C. |last3=Eizirik |first3=E. |last4=Gentry |first4=A. |last5=Werdelin |first5=L. |last6=Wilting |first6=A. |last7=Yamaguchi |first7=N. |last8=Abramov |first8=A. V. |last9=Christiansen |first9=P. |last10=Driscoll |first10=C. |last11=Duckworth |first11=J. W. |last12=Johnson |first12=W. |last13=Luo |first13=S.-J. |last14=Meijaard |first14=E. |last15=O'Donoghue |first15=P. |last16=Sanderson |first16=J. |last17=Seymour |first17=K. |last18=Bruford |first18=M. |last19=Groves |first19=C. |last20=Hoffmann |first20=M. |last21=Nowell |first21=K. |last22=Timmons |first22=Z. |last23=Tobe |first23=S. |name-list-style=amp |date=2017 |title=A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group |journal=Cat News |issue=Special Issue 11 |pages=66–68 |url=https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=66 |access-date=27 August 2019 |archive-date=17 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200117172708/https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=66 |url-status=live}}</ref> Results of a 2018 ] study of 32 samples from the six living putative subspecies—the Bengal, Malayan, Indochinese, South China, Siberian and Sumatran tiger—found them to be distinct and separate ]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Liu |first1=Y.-C. |first2=X. |last2=Sun |first3=C. |last3=Driscoll |first4=D. G. |last4=Miquelle |first5=X. |last5=Xu |first6=P. |last6=Martelli |first7=O. |last7=Uphyrkina |first8=J. L. D. |last8=Smith |first9=S. J. |last9=O'Brien |first10=S.-J. |last10=Luo |name-list-style=amp |title=Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of natural history and adaptation in the world's tigers |journal=Current Biology |volume=28 |issue=23 |date=2018 |pages=3840–3849 |doi=10.1016/j.cub.2018.09.019 |pmid=30482605 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2018CBio...28E3840L}}</ref> These results were corroborated in 2021 and 2023.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Armstrong|first1=E. E.|last2=Khan|first2=A. |last3=Taylor|first3=R. W.|last4=Gouy|first4=A. |last5=Greenbaum |first5=G. |last6=Thiéry|first6=A |last7=Kang|first7=J. T.|last8=Redondo|first8=S. A.|last9=Prost|first9=S. |last10=Barsh |first10=G. |last11=Kaelin |first11=C. |last12=Phalke|first12=S. |last13=Chugani|first13=A. |last14=Gilbert|first14=M. |last15=Miquelle |first15=D. |last16=Zachariah |first16=A. |last17=Borthakur|first17=U. |last18=Reddy|first18=A. |last19=Louis|first19=E. |last20=Ryder |first20=O. A. |last21=Jhala |first21=Y. V.|last22=Petrov|first22=D. |last23=Excoffier|first23=L. |last24=Hadly|first24=E. |last25=Ramakrishnan |first25=U. |name-list-style=amp |year=2021|title=Recent evolutionary history of tigers highlights contrasting roles of genetic drift and selection |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution|volume=38|issue=6|pages=2366–2379 |doi=10.1093/molbev/msab032 |pmid=33592092 |pmc=8136513}}</ref><ref name=Wang2023>{{cite journal|last1=Wang|first1=C. |last2=Wu|first2=D. D. |last3=Yuan |first3=Y. H. |last4=Yao |first4=M. C.|last5=Han|first5=J. L.|last6=Wu|first6=Y. J.|last7=Shan|first7=F. |last8=Li|first8=W. P. |last9=Zhai |first9=J. Q. |last10=Huang |first10=M|last11=Peng|first11=S. H.|last12=Cai|first12=Q .H.|last13=Yu|first13=J. Y. |last14=Liu|first14=Q. X. |last15=Lui |first15=Z. Y. |last16=Li|first16=L. X.|last17=Teng|first17=M. S.|last18=Huang|first18=W. |last19=Zhou|first19=J. Y. |last20=Zhang |first20=C. |last21=Chen|first21=W. |last22=Tu|first22=X. L.|year=2023|title=Population genomic analysis provides evidence of the past success and future potential of South China tiger captive conservation|journal=BMC Biology|volume=21 |issue=1 |page=64 |doi=10.1186/s12915-023-01552-y |doi-access=free |pmid=37069598 |pmc=10111772 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> The Cat Specialist Group states that "Given the varied interpretations of data, the taxonomy of this species is currently under review by the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group."<ref>{{cite web|title=Tiger|publisher=CatSG|url=http://www.catsg.org/index.php?id=124|accessdate=14 June 2024}}</ref> | |||

| The following tables are based on the ] of the tiger as of 2005,<ref name=MSW3/> and also reflect the classification recognised by the Cat Classification Task Force in 2017.<ref name=catsg/> | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |+ style="text-align: centre;" | ''Panthera tigris tigris'' {{small|(Linnaeus, 1758)}}<ref name=Linn1758/> | |||

| ! Population !! Description !! Image | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | ] {{small|formerly ''P. t. tigris'' (Linnaeus, 1758)}}<ref name=Linn1758/> | |||

| | | This population inhabits the ].<ref name=Jackson1996>{{Cite book |author1=Nowell, K. |author2=Jackson, P. |title=Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan |place=Gland, Switzerland |publisher=IUCN |year=1996 |isbn=2-8317-0045-0 |name-list-style=amp |pages=55–65 |chapter=Tiger, ''Panthera tigris'' (Linnaeus, 1758) |chapter-url=https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/1996-008.pdf#page=80 |access-date=25 January 2024 |archive-date=25 January 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240125121859/https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/1996-008.pdf#page=80 |url-status=live}}</ref> The Bengal tiger has shorter fur than tigers further north,<ref name=pocock1939/> with a light ] to orange-red colouration,<ref name=pocock1939/><ref>{{cite report|title=Indian National Studbook of the Bengal Tiger (''Panthera tigris tigris'') |publisher=Central Zoo Authority, Wildlife Institute of India |date=2011 |url=https://cza.nic.in/uploads/documents/studbooks/english/Bengal%20Tiger%20Studbook%202011.pdf |last1=Srivastav|first1=A. |last2=Malviya |first2=M. |last3=Tyagi |first3=P. C.|last4=Nigam |first4=P. |name-list-style=amp |accessdate=27 May 2024}}</ref> and relatively long and narrow nostrils.<ref name="Mazák2010"/> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | ] ] {{small|formerly ''P. t. virgata'' (], 1815)}}<ref name=Illiger>{{cite journal |last1=Illiger |first1=C. |date=1815 |title=Überblick der Säugethiere nach ihrer Verteilung über die Welttheile |journal=Abhandlungen der Königlichen Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin |volume=1804–1811 |pages=39–159 |url=https://bibliothek.bbaw.de/digitalisierte-sammlungen/akademieschriften/ansicht-akademieschriften?tx_bbaw_academicpublicationshow%5Baction%5D=show&tx_bbaw_academicpublicationshow%5Bcontroller%5D=AcademicPublication%5CVolume&tx_bbaw_academicpublicationshow%5Bpage%5D=195&tx_bbaw_academicpublicationshow%5Bvolume%5D=85&cHash=f015ec3f9a13240a9559ebdcb88aafa4}}</ref> | |||

| | |This population occurred from Turkey to around the Caspian Sea.<ref name=Jackson1996/> It had bright rusty-red fur with thin and closely spaced brownish stripes,{{sfn|Sludskii|1992|p=137}} and a broad ].<ref name=Kitchener1999/> Genetic analysis revealed that it was closely related to the Siberian tiger.<ref name=Driscoll2009>{{Cite journal |last1=Driscoll |first1=C. A. |last2=Yamaguchi |first2=N. |last3=Bar-Gal |first3=G. K. |last4=Roca |first4=A. L. |last5=Luo |first5=S. |last6=MacDonald |first6=D. W. |last7=O'Brien |first7=S. J. |name-list-style=amp |title=Mitochondrial phylogeography illuminates the origin of the extinct Caspian Tiger and its relationship to the Amur Tiger |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0004125 |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=e4125 |date=2009 |pmid=19142238 |pmc=2624500 |bibcode=2009PLoSO...4.4125D |doi-access=free}}</ref> It has been extinct since the 1970s.<ref name=Seidensticker1999/> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | ] {{small|formerly ''P. t. altaica'' (], 1844)}}<ref name=Temminck>{{cite book |last=Temminck |first=C. J. |date=1844 |chapter=Aperçu général et spécifique sur les Mammifères qui habitent le Japon et les Iles qui en dépendent |title=Fauna Japonica sive Descriptio animalium, quae in itinere per Japoniam, jussu et auspiciis superiorum, qui summum in India Batava imperium tenent, suscepto, annis 1825–1830 collegit, notis, observationibus et adumbrationibus illustravit Ph. Fr. de Siebold |location=Leiden |publisher=Lugduni Batavorum |editor1=Siebold, P. F. v. |editor2=Temminck, C. J. |editor3=Schlegel, H. |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/faunajaponicasi00sieb/page/43}}</ref> | |||

| | |This population lives in the ], ] and possibly North Korea.<ref name=Jackson1996/> The Siberian tiger has long hair and dense fur.<ref name=Temminck/> Its ground colour varies widely from ]-yellow in winter to more reddish and vibrant after moulting.{{sfn|Sludskii|1992|p=131}} The skull is shorter and broader than the skulls of tigers further south.<ref name="Mazák2010">{{cite journal |last1=Mazák |first1=J. H. |year=2010|title=Craniometric variation in the tiger (''Panthera tigris''): Implications for patterns of diversity, taxonomy and conservation |journal=Mammalian Biology |volume=75 |issue=1 |pages=45–68 |doi=10.1016/j.mambio.2008.06.003|bibcode=2010MamBi..75...45M}}</ref> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | ] {{small|formerly ''P. t. amoyensis'' (], 1905)}}<ref name=Hilzheimer>{{cite journal |last=Hilzheimer |first=M. |date=1905 |title=Über einige Tigerschädel aus der Straßburger zoologischen Sammlung |journal=Zoologischer Anzeiger |volume=28 |pages=594–599 |url=https://archive.org/details/zoologischeranze28deut/page/596}}</ref> | |||

| | |This tiger historically lived in south-central China.<ref name=Jackson1996/> The skulls of the five ]s had shorter ]s and ] than tigers from India, a smaller cranium, ]s set closer together and larger ]es; skins were yellowish with ]-like stripes.<ref name=Hilzheimer/> It has a unique mtDNA ] due to interbreeding with ancient tiger lineages.<ref name=catsg/><ref name=Sun2023/><ref name=Hu2022/> It is ] as there has not been a confirmed sighting since the 1970s,<ref name=iucn/> and survives only in captivity.<ref name=Wang2023/> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | ] {{small|formerly ''P. t. corbetti'' (], 1968)}}<ref name=Mazak1968>{{cite journal |last=Mazák |first=V. |author-link=Vratislav Mazák |date=1968 |title=Nouvelle sous-espèce de tigre provenant de l'Asie du sud-est |journal=Mammalia |volume=32 |issue=1 |pages=104–112 |doi=10.1515/mamm.1968.32.1.104|s2cid=84054536}}</ref> | |||

| | |This tiger population occurs on the ].<ref name=Jackson1996/> Indochinese tiger specimens have smaller craniums than Bengal tigers and appear to have darker fur with somewhat thin stripes.<ref name=Mazak1968/><ref name=mazak06>{{cite journal |last1=Mazák |first1=J. H. |last2=Groves |first2=C. P. |name-list-style=amp |date=2006 |title=A taxonomic revision of the tigers (''Panthera tigris'') of Southeast Asia |journal=Mammalian Biology |volume=71 |issue=5 |pages=268–287 |doi=10.1016/j.mambio.2006.02.007 |bibcode=2006MamBi..71..268M |url=http://www.dl.edi-info.ir/A%20taxonomic%20revision%20of%20the%20tigers%20of%20Southeast%20Asia.pdf |access-date=15 January 2024 |archive-date=31 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230531133543/http://www.dl.edi-info.ir/A%20taxonomic%20revision%20of%20the%20tigers%20of%20Southeast%20Asia.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | ] {{small|formerly ''P. t. jacksoni'' (Luo et al., 2004)}}<ref name=Luo04>{{cite journal |last1=Luo |first1=S.-J. |last2=Kim |first2=J.-H. |last3=Johnson |first3=W. E. |last4=van der Walt |first4=J. |last5=Martenson |first5=J. |last6=Yuhki |first6=N. |last7=Miquelle |first7=D. G. |last8=Uphyrkina |first8=O. |last9=Goodrich |first9=J. M. |last10=Quigley |first10=H. B. |last11=Tilson |first11=R. |last12=Brady |first12=G. |last13=Martelli |first13=P. |last14=Subramaniam |first14=V. |last15=McDougal |first15=C. |last16=Hean |first16=S. |last17=Huang |first17=S.-Q. |last18=Pan |first18=W. |last19=Karanth |first19=U. K. |last20=Sunquist |first20=M. |last21=Smith |first21=J. L. D. |last22=O'Brien |first22=S. J. |name-list-style=amp |date=2004 |title=Phylogeography and genetic ancestry of tigers (''Panthera tigris'') |journal=] |volume=2 |issue=12 |page=e442 |pmid=15583716 |pmc=534810 |doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0020442 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| | |The Malayan tiger was proposed as a distinct subspecies on the basis of mtDNA and ] that differ from the Indochinese tiger.<ref name=Luo04/> It does not differ significantly in fur colour or skull size from Indochinese tigers.<ref name=mazak06/> There is no clear geographical barrier between tiger populations in northern Malaysia and southern Thailand.<ref name=iucn/> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |+ style="text-align: centre;" | ''Panthera tigris sondaica'' {{small|(Temminck, 1844)}}<ref name=catsg/> | |||

| ! Population !! Description !! Image | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | †] {{small|formerly ''P. t. sondaica'' (Temminck, 1944)}}<ref name=Temminck/> | |||

| | |This tiger was described based on an unspecified number of skins with short and smooth hair.<ref name=Temminck/> Tigers from Java were small compared to tigers of the Asian mainland, had relatively elongated skulls compared to the Sumatran tiger and longer, thinner and more numerous stripes.<ref name=mazak06/> The Javan tiger is thought to have gone extinct by the 1980s.<ref name=Seidensticker1999/> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | †] {{small|formerly ''P. t. balica'' (], 1912)}}<ref name=Schwarz>{{cite journal |last=Schwarz |first=E. |date=1912 |title=Notes on Malay tigers, with description of a new form from Bali |journal=Annals and Magazine of Natural History |pages=324–326 |series=8 |volume=10 |issue=57 |doi=10.1080/00222931208693243 |url=https://archive.org/stream/annalsmagazineof8101912lond#page/324/mode/2up}}</ref> | |||

| | | This tiger occurred on ] and had brighter fur and a smaller skull than the Javan tiger.<ref name=Schwarz/><ref name="der-tiger">{{cite book |author=Mazak, V. |year=2004 |title=Der Tiger |publisher=Westarp Wissenschaften Hohenwarsleben|location = Madgeburg |isbn=978-3-89432-759-0 |language=de}}</ref> A typical feature of Bali tiger skulls is the narrow occipital bone, which is similar to the Javan tiger's skull.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Mazák |first1=V. |author-link=Vratislav Mazák |last2=Groves |first2=C. P. |last3=Van Bree |first3=P. |date=1978 |title=Skin and Skull of the Bali Tiger, and a list of preserved specimens of ''Panthera tigris balica'' (Schwarz, 1912) |journal=] |volume=43 |issue=2 |pages=108–113 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> The tiger went extinct in the 1940s.<ref name=Seidensticker1999>Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S. & Jackson, P. (1999). "Preface" in {{harvnb|Seidensticker|Christie|Jackson|1999|pp=xv–xx}}</ref> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | ] {{small|formerly ''P. t. sumatrae'' (], 1929)}}<ref name=Pocock1929>{{cite journal |last=Pocock |first=R. I. |date=1929 |title=Tigers |journal=] |volume=33 |pages=505–541 |url=https://archive.org/details/journalofbomb33341929bomb/page/n185}}</ref> | |||

| | The type specimen from ] had dark fur.<ref name=Pocock1929/> The Sumatran tiger has particularly long hair around the face,<ref name=Jackson1996/> thick body stripes and a broader and smaller ] than other island tigers.<ref name=mazak06/> | |||

| | |] | |||

| |} | |||

| === Evolution === | |||

| {{Cladogram|align=right|caption=Phylogeny of the genus ''Panthera'' based on a 2016 ] study<ref name=Li_al2016>{{cite journal |last1=Li |first1=G. |last2=Davis |first2=B. W. |last3=Eizirik |first3=E. |last4=Murphy |first4=W. J. |date=2016 |title=Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae) |journal=Genome Research |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=1–11 |doi=10.1101/gr.186668.114 |pmid=26518481 |pmc=4691742}}</ref> | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |label1='']'' | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |2='''Tiger''' ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |2={{clade sequential | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| |3=] ] | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| The tiger shares the genus ''Panthera'' with the ], ], ] and ]. Results of genetic analyses indicate that the tiger and snow leopard are ] whose ] split from each other between 2.70 and 3.70 million years ago.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Davis |first1=B. W. |last2=Li |first2=G. |last3=Murphy |first3=W. J. |title=Supermatrix and species tree methods resolve phylogenetic relationships within the big cats, ''Panthera'' (Carnivora: Felidae) |journal=Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution |year=2010 |volume=56 |issue=1 |pages=64–76 |pmid=20138224 |doi=10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.036 |bibcode=2010MolPE..56...64D |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> The tiger's whole genome sequencing shows ] that parallel those in other cat genomes.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=The tiger genome and comparative analysis with lion and snow leopard genomes |doi=10.1038/ncomms3433 |pmid=24045858 |pmc=3778509 |journal=Nature Communications |volume=4 |page=2433 |year=2013 |last1=Cho |first1=Y. S. |last2=Hu |first2=L. |last3=Hou |first3=H. |last4=Lee |first4=H. |last5=Xu |first5=J. |last6=Kwon |first6=S. |last7=Oh |first7=S. |last8=Kim |first8=H. M. |last9=Jho |first9=S. |last10=Kim |first10=S. |last11=Shin |first11=Y. A. |last12=Kim |first12=B. C. |last13=Kim |first13=H. |last14=Kim |first14=C. U. |last15=Luo | first15=S. J. |last16=Johnson |first16=W. E. |last17=Koepfli |first17=K. P. |last18=Schmidt-Küntzel |first18=A. |last19=Turner |first19=J. A. |last20=Marker |first20=L. |last21=Harper |first21=C. |last22=Miller |first22=S. M. |last23=Jacobs |first23=W. |last24=Bertola |first24=L. D. |last25=Kim |first25=T. H. |last26=Lee |first26=S. |last27=Zhou |first27=Q. |last28=Jung |first28=H. J. |last29=Xu |first29=X. |last30=Gadhvi |first30=P. |name-list-style=amp |bibcode=2013NatCo...4.2433C |hdl=2263/32583}}</ref> | |||

| The fossil species '']'' of early ] northern China was described as a possible tiger ancestor when it was discovered in 1924, but modern cladistics places it as ] to modern ''Panthera''.<ref name=Mazák>{{cite journal |year=2011 |title=Oldest Known Pantherine Skull and Evolution of the Tiger |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=6 |issue=10 |page=e25483 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0025483 |pmid=22016768 |last1=Mazák |first1=J. H. |last2=Christiansen |first2=P. |last3=Kitchener |first3=A. C. |bibcode=2011PLoSO...625483M |pmc=3189913 |doi-access=free |name-list-style=amp}}</ref><ref name=Tseng>{{cite journal |author1=Tseng, Z. J. |author2=Wang, X. |author3=Slater, G. J. |author4=Takeuchi, G. T. |author5=Li, Q. |author6=Liu, J. |author7=Xie, G. |date=2014 |title=Himalayan fossils of the oldest known pantherine establish ancient origin of big cats |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume=281 |issue=1774 |page=20132686 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2013.2686|pmid=24225466 |pmc=3843846 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> '']'' lived around the same time and place, and was suggested to be a sister species of the modern tiger when it was examined in 2014.<ref name=Mazák/> However, as of 2023, at least two subsequent studies considered ''P. zdanskyi'' likely to be a ] of ''P. palaeosinensis'', noting that its proposed differences from that species fell within the range of individual variation.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hemmer |first1=Helmut |title= The identity of the "lion", ''Panthera principialis'' sp. nov., from the Pliocene Tanzanian site of Laetoli and its significance for molecular dating the pantherine phylogeny, with remarks on Panthera shawi (Broom, 1948), and a revision of Puma incurva (Ewer, 1956), the Early Pleistocene Swartkrans "leopard" (Carnivora, Felidae)|url= |journal= Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments|year=2023 |volume= 103|issue= 2|pages= 465–487|doi=10.1007/s12549-022-00542-2 |bibcode=2023PdPe..103..465H |access-date=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|doi=10.1080/08912963.2022.2034808 |title=Discovery of jaguar from northeastern China middle Pleistocene reveals an intercontinental dispersal event |date=2023 |last1=Jiangzuo |first1=Q. |last2=Wang |first2=Y. |last3=Ge |first3=J. |last4=Liu |first4=S. |last5=Song |first5=Y. |last6=Jin |first6=C. |last7=Jiang |first7=H. |last8=Liu |first8=J. |journal=Historical Biology |volume=35 |issue=3 |pages=293–302 |bibcode=2023HBio...35..293J |s2cid=246693903 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> The earliest appearance of the modern tiger species in the fossil record are jaw fragments from ] in China that are dated to the early Pleistocene.<ref name=Mazák/> | |||

| Middle- to late-Pleistocene tiger fossils have been found throughout China, Sumatra and Java. Prehistoric subspecies include '']'' and '']'' of Java and Sumatra and '']'' of China; late Pleistocene and early ] fossils of tigers have also been found in ] and Palawan, Philippines.<ref name=Kitchener2009>Kitchener, A. & Yamaguchi, N. (2009). "What is a Tiger? Biogeography, Morphology, and Taxonomy" in {{harvnb|Tilson|Nyhus|2010|pp=53–84}}</ref> Fossil specimens of tigers have also been reported from the Middle-Late Pleistocene of Japan.<ref>Hasegawa, Y., Takakuwa, Y., Nenoki, K. & Kimura, T. <abbr>. Bull. Gunma Museum Nat. Hist</abbr>. 23, (2019) (in Japanese with English abstract)</ref> Results of a ] study indicate that all living tigers have a common ancestor that lived between 108,000 and 72,000 years ago.<ref name=Luo04/> Genetic studies suggest that the tiger population contracted around 115,000 years ago due to glaciation. Modern tiger populations originated from a ] in Indochina and spread across Asia after the ]. As they colonised northeastern China, the ancestors of the South China tiger intermixed with a relict tiger population.<ref name=Hu2022>{{cite journal |last1=Hu|first1=J. |last2=Westbury |first2=M. V.|last3=Yuan|first3=J. |last4=Wang|first4=C. |last5=Xiao|first5=B. |last6=Chen|first6=S. |last7=Song|first7=S. |last8=Wang |first8=L. |last9=Lin |first9=H. |last10=Lai|first10=X. |last11=Sheng|first11=G. |name-list-style=amp |year=2022|title=An extinct and deeply divergent tiger lineage from northeastern China recognized through palaeogenomics |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume=289 |issue=1979 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2022.0617|pmid=35892215|pmc=9326283}}</ref><ref name=Sun2023>{{cite journal |last1=Sun |first1=X. |last2=Liu |first2=Y.-C. |last3=Tiunov |first3=M. P. |last4=Gimranov|first4=D. O. |last5=Zhuang |first5=Y. |last6=Han |first6=Y. |last7=Driscoll |first7=C. A. |last8=Driscoll|first8=C. A. |last9=Pang |first9=Y. |last10=Li |first10=C. |last11=Pan|first11=Y|last12=Velasco|first12=M. S. |last13=Gopalakrishnan |first13=S. |last14=Yang |first14=R.-Z. |last15=Li |first15=B.-G. |last16=Jin |first16=K. |last17=Xu |first17=X. |last18=Uphyrkina |first18=O. |last19=Huang |first19=Y. |last20=Wu |first20=X.-H. |last21=Gilbert |first21=M. T. P. |last22=O'Brien |first22=S. J. |last23=Yamaguchi |first23=N. |last24=Luo |first24=S.-J. |year=2023 |title=Ancient DNA reveals genetic admixture in China during tiger evolution |journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution |volume=7 |issue=11 |pages=1914–1929 |doi=10.1038/s41559-023-02185-8 |pmid=37652999 |bibcode=2023NatEE...7.1914S |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> | |||

| === Hybrids === | |||

| {{further|Felid hybrids|Panthera hybrid}} | |||

| Tigers can ] with other ''Panthera'' cats and have done so in captivity. The ] is the offspring of a female tiger and a male lion and the ] the offspring of a male tiger and a female lion.<ref name=Gabryś>{{cite journal |author1=Gabryś, J. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Kij, B. |author3=Kochan, J. |author4=Bugno-Poniewierska, M. |year=2021 |title=Interspecific hybrids of animals-in nature, breeding and science–a review |journal=Annals of Animal Science |volume=21 |issue=2 |pages=403–415 |doi=10.2478/aoas-2020-0082 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The lion sire passes on a growth-promoting gene, but the corresponding growth-inhibiting gene from the female tiger is absent, so that ligers grow far larger than either parent species. By contrast, the male tiger does not pass on a growth-promoting gene while the lioness passes on a growth inhibiting gene; hence, tigons are around the same size as their parents.<ref name=imprinting>{{cite web |title=Genomic Imprinting |publisher=Genetic Science Learning Center, Utah.org |access-date=26 August 2018 |url=https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/epigenetics/imprinting/ |archive-date=4 September 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190904215316/https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/EPIGENETICS/imprinting/ |url-status=live}}</ref> Since they often develop life-threatening birth defects and can easily become obese, breeding these hybrids is regarded as unethical.<ref name=Gabryś/> | |||

| == Characteristics == | |||

| ] | |||

| The tiger has a typical felid morphology, with a muscular body, shortened legs, strong forelimbs with wide front paws, a large head and a tail that is about half the length of the rest of its body.<ref name=Mazak1981/>{{sfn|Sludskii|1992|p=98}} It has five digits, including a ], on the front feet and four on the back, all of which have retractile claws that are compact and curved, and can reach {{convert|10|cm|in|abbr=on}} long.<ref name=Mazak1981/>{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=26}} The ears are rounded and the eyes have a round pupil.<ref name=Mazak1981/> The snout ends in a triangular, pink tip with small black dots, the number of which increase with age.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Zhao|first1=C. |last2=Dai|first2=W. |last3=Liu|first3=Q. |last4=Liu|first4=D. |last5=Roberts |first5=N. J. |last6=Liu |first6=Z. |last7=Gong |first7=M. |last8=Qiu |first8=H. |last9=Liu |first9=C. |last10=Liu |first10=D. |last11=Ma |first11=G. |last12=Jiang |first12=G. |year=2024 |title=Combination of facial and nose features of Amur tigers to determine age|journal=Integrative Zoology |doi=10.1111/1749-4877.12817 |pmid=38509845 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> The tiger's skull is robust, with a constricted front region, proportionally small, elliptical ], long ]s and a lengthened ] with a large ].{{sfn|Sludskii|1992|p=103}}<ref name=Mazak1981/> It resembles a lion's skull, but differs from it in the concave or flattened underside of the lower jaw and in its longer nasals.{{sfn|Sludskii|1992|p=103}}<ref name=Kitchener2009/> The tiger has 30 fairly robust teeth and its somewhat curved ] are the longest in the cat family at {{cvt|6.4|–|7.6|cm}}.<ref name=Mazak1981 />{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=25}} | |||

| The tiger has a head-body length of {{cvt|1.4|–|2.8|m}} with a {{cvt|0.6|–|1.1|m}} tail and stands {{cvt|0.8|–|1.1|m}} at the shoulder.<ref name=Walker>{{cite book |author1=Novak, R. M. |author2=Walker, E. P. |name-list-style=amp |year=1999 |chapter=''Panthera tigris'' (tiger) |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=T37sFCl43E8C&pg=PA825 |title=Walker's Mammals of the World |edition=6th |publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press |location=Baltimore |isbn=978-0-8018-5789-8 |pages=825–828 |access-date=17 October 2020 |archive-date=5 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240505145513/https://books.google.com/books?id=T37sFCl43E8C&pg=PA825#v=onepage&q&f=false#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=bot: unknown }}</ref> The Siberian and Bengal tigers are the largest.<ref name=Mazak1981/> Male Bengal tigers weigh {{cvt|200|–|260|kg}}, and females weigh {{cvt|100|–|160|kg}}; island tigers are the smallest, likely due to ].<ref name=Kitchener1999/> Male Sumatran tigers weigh {{cvt|100|–|140|kg}}, and females weigh {{cvt|75|–|110|kg}}.<ref name=Sunquist2010/> | |||

| The tiger is popularly thought to be the largest living felid species; but since tigers of the different subspecies and populations vary greatly in size and weight, the tiger's average size may be less than the lion's, while the largest tigers are bigger than their lion counterparts.<ref name=Kitchener2009/> | |||

| ===Coat=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The tiger's coat usually has short hairs, reaching up to {{cvt|35|mm}}, though the hairs of the northern-living Siberian tiger can reach {{cvt|105|mm}}. Belly hairs tend to be longer than back hairs. The density of their fur is usually thin, though the Siberian tiger develops a particularly thick winter coat. The tiger has lines of fur around the face and long whiskers, especially in males.<ref name=Mazak1981/> It has an orange ] that varies from yellowish to reddish.{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=28}} White fur covers the underside, from head to tail, along with the inner surface of the legs and parts of the face.<ref name=Mazak1981 />{{sfn|Sludskii|1992|pp=99–102}} On the back of the ears, it has a prominent white spot, which is surrounded by black.<ref name=Mazak1981 /> The tiger is marked with distinctive black or dark brown stripes, which are uniquely patterned in each individual.<ref name=Mazak1981>{{cite journal |author=Mazák, V. |year=1981 |title=''Panthera tigris'' |journal=Mammalian Species |issue=152 |pages=1–8 |doi=10.2307/3504004 |jstor=3504004 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=Miquelle/> The stripes are mostly vertical, but those on the limbs and forehead are horizontal. They are more concentrated towards the backside and those on the trunk may reach under the belly. The tips of stripes are generally sharp and some may split up or split and fuse again. Tail stripes are thick bands and a black tip marks the end.{{sfn|Sludskii|1992|pp=99–102}} | |||

| The tiger is one of only a few striped cat species.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Allen, W. L. |author2=Cuthill, I. C. |author3=Scott-Samuel, N. E. |author4=Baddeley, R. |year=2010 |title=Why the leopard got its spots: relating pattern development to ecology in felids |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B |volume=278 |issue=1710 |pages=1373–1380 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2010.1734 |pmid=20961899 |pmc=3061134 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> Stripes are advantageous for ] in vegetation with vertical patterns of light and shade, such as trees, reeds and tall grass.<ref name=Miquelle>Miquelle, D. "Tiger" in {{harvnb|MacDonald|2001|pp=18–21}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Caro |first=T. |year=2005 |title=The adaptive significance of coloration in mammals |journal=BioScience |volume=55 |issue=2|pages=125–136 |doi=10.1641/0006-3568(2005)0552.0.CO;2}}</ref> This is supported by a ] study showing that the striping patterns line up with their environment.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Godfrey |first1=D. |last2=Lythgoe |first2=J. N. |last3=Rumball |first3=D. A. |name-list-style=amp |year=1987 |title=Zebra stripes and tiger stripes: the spatial frequency distribution of the pattern compared to that of the background is significant in display and crypsis |journal=] |volume=32 |issue=4 |pages=427–433 |doi=10.1111/j.1095-8312.1987.tb00442.x}}</ref> | |||

| The orange colour may also aid in concealment, as the tiger's prey is ] and possibly perceives the tiger as green and blended in with the vegetation.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Fennell, J. G. |author2=Talas, L. |author3=Baddeley, R. J. |author4=Cuthill, I. C. |author5=Scott-Samuel, N. E. |name-list-style=amp |year=2019 |title=Optimizing colour for camouflage and visibility using deep learning: the effects of the environment and the observer's visual system |journal=Journal of the Royal Society Interface |volume=16 |issue=154|doi=10.1098/rsif.2019.0183 |doi-access=free |page=20190183 |pmid=31138092 |pmc=6544896}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Colour variations ==== | |||

| ]|alt=White tiger with thickened stripes lying down]] | |||

| The three ] of Bengal tigers – nearly stripeless snow-white, white and golden – are now virtually non-existent in the wild due to the reduction of wild tiger populations but continue in captive populations. The ] has a white background colour with ]-brown stripes. The ] is pale golden with reddish-brown stripes. The snow-white tiger is a morph with extremely faint stripes and a pale sepia-brown ringed tail. White and golden morphs are the result of an ] with a white ] and a ] locus, respectively. The snow-white variation is caused by ]s with both white and wideband loci.<ref name=Xu_al2017>{{cite journal |author1=Xu, X. |author2=Dong, G. X. |author3=Schmidt-Küntzel, A. |author4=Zhang, X. L. |author5=Zhuang, Y. |author6=Fang, R. |author7=Sun, X. |author8=Hu, X. S. |author9=Zhang, T. Y. |author10=Yang, H. D. |author11=Zhang, D. L. |author12=Marker, L. |author13=Jiang, Z.-F. |author14=Li, R. |author15=Luo, S.-J. |name-list-style=amp |year=2017 |title=The genetics of tiger pelage color variations |journal=Cell Research |volume=27 |issue=7 |pages=954–957 |doi=10.1038/cr.2017.32 |pmid=28281538 |pmc=5518981 |url=https://www.luo-lab.org/publications/Xu17-CellRes-GoldenTiger.pdf |access-date=25 August 2018}}</ref> The breeding of white tigers is controversial, as they have no use for conservation. Only 0.001% of wild tigers have the genes for this colour morph and the overrepresentation of white tigers in captivity is the result of ]. Hence, their continued breeding will risk both ] and loss of ] in captive tigers.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Xavier |first1=N. |year=2010 |title=A new conservation policy needed for reintroduction of Bengal tiger-white |journal=Current Science |volume=99 |issue=7 |pages=894–895 |url=https://www.currentscience.ac.in/Volumes/99/07/0894.pdf |access-date=29 January 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Pseudo-] tigers with thick, merged stripes have been recorded in ] and three Indian zoos; a ] analysis of Indian tiger samples revealed that this ] is caused by a ] of a ] ] gene. Around 37% of the Simlipal tiger population has this feature, which has been linked to ].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Sagar, V. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Kaelin, C. B. |author3=Natesh, M. |author4=Reddy, P. A. |author5=Mohapatra, R. K. |author6=Chhattani, H. |author7=Thatte, P. |author8=Vaidyanathan, S. |author9=Biswas, S. |author10=Bhatt, S. |author11=Paul, S. |year=2021 |title=High frequency of an otherwise rare phenotype in a small and isolated tiger population |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=118 |issue=39 |page=e2025273118 |doi=10.1073/pnas.2025273118 |pmid=34518374 |pmc=8488692 |bibcode=2021PNAS..11825273S |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Most tigers live in forests or grasslands, for which their camouflage is ideally suited, and where it is easy to hunt prey that is faster or more agile. Among the big cats, only the tiger and ] are strong ]s; tigers are often found bathing in ]s, ]s, and ]s. Tigers hunt alone and eat primarily medium to large sized ]s such as ], ], ] and ]. However, they also take smaller prey on occasion. | |||

| == Distribution and habitat == | |||

| ]s are the tiger's only true predator, as tigers are often poached illegally for their ]. Also, their bones and nearly all body parts are used in ] for a range of purported uses including pain killers and ]s. ] for fur and destruction of ] have greatly reduced tiger populations in the wild. A century ago, there were approximately over 100,000 tigers in the world; now numbers are down to below 2,500 mature breeding individuals, with no subpopulation containing more than 250 mature breeding individuals<ref name="IUCN" />. All subspecies of tigers have been placed on the ] list. | |||

| ] in Russia|alt=Picture of tiger in forest at night]] | |||

| The tiger historically ranged from eastern Turkey, northern Iran and Afghanistan to Central Asia and from northern Pakistan through the ] and Indochina to southeastern Siberia, Sumatra, Java and Bali.<ref name=Mazak1981/> As of 2022, it inhabits less than 7% of its historical distribution and has a scattered range in the Indian subcontinent, the ], Sumatra, northeastern China and the ].<ref name=iucn/> As of 2020, India had the largest extent of global tiger habitat with {{cvt|300508|km2}}, followed by Russia with {{cvt|195819|km2}}.<ref name=Sanderson_al2023>{{cite journal |author1=Sanderson, E. W. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Miquelle, D. G. |author3=Fisher, K. |author4=Harihar, A. |author5=Clark, C. |author6=Moy, J. |author7=Potapov, P. |author8=Robinson, N. |author9=Royte, L. |author10=Sampson, D. |author11=Sanderlin, J. |author12=Yackulic, C. B. |author13=Belecky, M. |author14= Breitenmoser, U. |author15=Breitenmoser-Würsten, C. |author16=Chanchani, P. |author17=Chapman, S. |author18=Deomurari, A. |author19=Duangchantrasiri, S. |author20=Facchini, E. |author21=Gray, T. N. E. |author22=Goodrich, J. |author23=Hunter, L. |author24=Linkie, M. |author25=Marthy, W. |author26=Rasphone, A. |author27=Roy, S. |author28=Sittibal, D. |author29=Tempa, T. |author30=Umponjan, M. |author31=Wood, K. |year=2023 |title=Range-wide trends in tiger conservation landscapes, 2001–2020 |journal=Frontiers in Conservation Science |volume=4 |page=1191280 |doi=10.3389/fcosc.2023.1191280 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| The tiger mainly lives in forest habitats and is highly adaptable.<ref name=Sunquist2010>Sunquist, M. (2010). "What is a Tiger? Ecology and Behaviour" in {{harvnb|Tilson|Nyhus|2010|pp=19−34}}</ref> Records in Central Asia indicate that it primarily inhabited ] riverine forests and hilly and lowland forests in the ].{{sfn|Sludskii|1992|pp=108–112}} In the ]-] region of Russia and China, it inhabits ] and ]s; ]s serve as ] corridors, providing food and water for both tigers and ]s.<ref name=Miquelle_al1999>Miquelle, D. G.; Smirnov, E. N.; Merrill, T. W.; Myslenkov, A. E.; Quigley, H.; Hornocker, M. G. & Schleyer, B. (1999). "Hierarchical spatial analysis of Amur tiger relationships to habitat and prey" in {{harvnb|Seidensticker|Christie|Jackson|1999|pp=71–99}}</ref> On the Indian subcontinent, it inhabits mainly ], ], ]s, ]s, ]s and the ]s of the ].<ref name=Wikramanayake_al1999>Wikramanayake, E. D.; Dinerstein, E.; Robinson, J. G.; Karanth, K. U.; Rabinowitz, A.; Olson, D.; Mathew, T.; Hedao, P.; Connor, M.; Hemley, G. & Bolze, D. (1999). "Where can tigers live in the future? A framework for identifying high-priority areas for the conservation of tigers in the wild" in {{harvnb|Seidensticker|Christie|Jackson|1999|pp=265–267}}</ref> In the ]s, it was documented in ] up to an elevation of {{cvt|4200|m}} in Bhutan, of {{cvt|3630|m}} in the ] and of {{cvt|3139|m}} in ], southeastern Tibet.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Jigme, K. |author2=Tharchen, L. |name-list-style=amp |year=2012 |title=Camera-trap records of tigers at high altitudes in Bhutan |journal=Cat News |issue=56 |pages=14–15}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Adhikarimayum, A. S. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Gopi, G. V. |year=2018 |title=First photographic record of tiger presence at higher elevations of the Mishmi Hills in the Eastern Himalayan Biodiversity Hotspot, Arunachal Pradesh, India |journal=Journal of Threatened Taxa |volume=10 |issue=13 |pages=12833–12836 |doi=10.11609/jott.4381.10.13.12833-12836 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Li, X. Y. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Hu, W. Q. |author3=Wang, H. J. |author4=Jiang, X. L. |year=2023 |title=Tiger reappearance in Medog highlights the conservation values of the region for this apex predator |journal=Zoological Research |volume=44 |issue=4 |pages=747–749 |doi=10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2023.178 |doi-access=free |pmid=37464931|pmc=10415778}}</ref> In Thailand, it lives in ] and ] forests.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Simcharoen, S. |author2=Pattanavibool, A. |author3=Karanth, K. U. |author4=Nichols, J. D. |author5=Kumar, N. S. |name-list-style=amp |year=2007 |title=How many tigers ''Panthera tigris'' are there in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand? An estimate using photographic capture-recapture sampling |journal=Oryx |volume=41 |issue=4 |pages=447–453 |doi=10.1017/S0030605307414107|doi-access=free}}</ref> In Sumatra, it inhabits lowland ]s and rugged ]s.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Wibisono, H. T. |author2=Linkie, M. |author3=Guillera-Arroita, G. |author4=Smith, J. A. |author5=Sunarto |author6=Pusarini, W. |author7=Asriadi |author8=Baroto, P. |author9=Brickle, N. |author10=Dinata, Y. |author11=Gemita, E. |author12=Gunaryadi, D. |author13=Haidir, I. A. |author14=Herwansyah |year=2011 |title=Population status of a cryptic top predator: An island-wide assessment of Tigers in Sumatran rainforests |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=6 |issue=11 |page=e25931 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0025931 |pmid=22087218 |pmc=3206793 |bibcode=2011PLoSO...625931W |doi-access=free |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> | |||

| ==Physical traits== | |||

| <!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: ] --> | |||

| Tigers are the largest and heaviest cats in the world<ref name="WWF">{{cite web|url=http://www.worldwildlife.org/tigers/ecology.cfm|title=WWF – Tigers – Ecology}}</ref>. Although different subspecies of tiger have different characteristics, in general male tigers weigh between 200 and 320 ] (440 lb and 700 lb) and females between 120 and 181 kg (265 lb and 400 lb). At an average, males are between 2.6 and 3.3 ]s (8 feet 6 inches to 10 feet 8 inch) in length, and females are between 2.3 and 2.75 metres (7 ft 6 in and 9 ft) in length. Of the living subspecies, ]s are the smallest, and ] or ]s are the largest. | |||

| === Population density === | |||

| The stripes of most tigers vary from brown or hay to pure black, although ]s have far fewer apparent stripes. White tigers are not a separate sub-species; They are ] Indian tigers. The form and density of stripes differs between subspecies, but most tigers have in excess of 100 stripes. The now extinct ] may have had far more than this. The pattern of stripes is unique to each animal, and thus could potentially be used to identify individuals, much in the same way as ]s are used to identify people. This is not, however, a preferred method of identification, due to the difficulty of recording the stripe pattern of a wild tiger. It seems likely that the function of stripes is ], serving to hide these animals from their prey. Few large animals have colour vision as capable as that of humans, so the colour is not as great of a problem as one is believed that they are used more to enhance daytime vision than for colour vision. <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.buschgardens.org/infobooks/Tiger/sensetiger.html|title=Senses part from Busch Gardens Animal Information Database - Tiger infobook|accessdate: =] | |||

| ]ping during 2010–2015 in the deciduous and subtropical pine forest of ], northern India revealed a stable tiger ] of 12–17 individuals per {{cvt|100|km2}} in an area of {{cvt|521|km2}}.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Bisht, S. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Banerjee, S. |author3=Qureshi, Q. |author4=Jhala, Y. |year=2019 |title=Demography of a high-density tiger population and its implications for tiger recovery |journal=Journal of Applied Ecology |volume= 56 |issue=7 |pages=1725–1740 |doi=10.1111/1365-2664.13410 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2019JApEc..56.1725B}}</ref> | |||

| }}</ref> The stripe pattern is found on a tiger's skin and if you shaved one, you would find that its distinctive camouflage pattern would be preserved. | |||

| In northern Myanmar, the population density in a sampled area of roughly {{cvt|3250|km2}} in a mosaic of tropical broadleaf forest and grassland was estimated to be 0.21–0.44 tigers per {{cvt|100|km2}} as of 2009.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Lynam, A. J. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Rabinowitz, A. |author3=Myint, T. |author4=Maung, M. |author5=Latt, K. T. |author6=Po, S. H. T. |year=2009 |title=Estimating abundance with sparse data: tigers in northern Myanmar |journal=Population Ecology |volume=51 |issue=1 |pages=115–121 |doi=10.1007/s10144-008-0093-5 |bibcode=2009PopEc..51..115L}}</ref> | |||

| Population density in mixed deciduous and semi-evergreen forests of Thailand's ] was estimated at 2.01 tigers per {{cvt|100|km2}}; during the 1970s and 1980s, ] and poaching had occurred in the adjacent ] and ]s, where population density was much lower, estimated at only 0.359 tigers per {{cvt|100|km2}} as of 2016.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Phumanee, W. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Steinmetz, R. |author3=Phoonjampa, R. |author4=Weingdow, S. |author5=Phokamanee, S. |author6=Bhumpakphan, N. |author7=Savini, T. |year=2021 |title=Tiger density, movements, and immigration outside of a tiger source site in Thailand |journal=Conservation Science and Practice |volume=3 |issue=12 |page=e560 |doi=10.1111/csp2.560 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2021ConSP...3E.560P}}</ref> | |||

| Population density in ] and montane forests in northern Malaysia was estimated at 1.47–2.43 adult tigers per {{cvt|100|km2}} in ], but 0.3–0.92 adult tigers per {{cvt|100|km2}} in the unprotected ] Temengor Forest Reserve.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Rayan, D. M. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Linkie, M. |year=2015 |title=Conserving tigers in Malaysia: A science-driven approach for eliciting conservation policy change |journal=Biological Conservation |volume=184 |pages=18–26 |doi=10.1016/j.biocon.2014.12.024 |bibcode=2015BCons.184...18R}}</ref> | |||

| ==Behaviour and ecology== | |||

| Several obscure references to various other tiger colors have also been found, including most notably, the reference to the "blue" or slate-colored tiger. | |||

| ] | |||

| Camera trap data show that tigers in ] avoided locations frequented by people and were more active at night than during day.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Carter |first1=N. H. |last2=Shrestha |first2=B. K. |last3=Karki |first3=J. B. |last4=Pradhan |first4=N. M. B. |last5=Liu|first5=J. |name-list-style=amp |year=2012 |title=Coexistence between wildlife and humans at fine spatial scales |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=109 |issue=38 |pages=15360–15365 |doi=10.1073/pnas.1210490109 |doi-access=free |pmid=22949642 |pmc=3458348|bibcode=2012PNAS..10915360C}}</ref> | |||

| In ], six ]ed tigers were most active from dawn to early morning and reached their zenith around 7:00 o'clock in the morning.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Naha, D. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Jhala, Y. V. |author3=Qureshi, Q. |author4=Roy, M. |author5=Sankar, K. |author6=Gopal, R. |year=2016 |title=Ranging, activity and habitat use by tigers in the mangrove forests of the Sundarban |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=11 |issue=4 |page=e0152119 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0152119 |doi-access=free |pmid=27049644 |pmc=4822765 |bibcode=2016PLoSO..1152119N}}</ref> | |||

| A three-year-long camera trap survey in ] revealed that tigers were most active from dusk until midnight.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Pokheral, C. P. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Wegge, P. |year=2019 |title=Coexisting large carnivores: spatial relationships of tigers and leopards and their prey in a prey-rich area in lowland Nepal |journal=Écoscience |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=1–9 |doi=10.1080/11956860.2018.1491512 |bibcode=2019Ecosc..26....1P |s2cid=92446020}}</ref> | |||

| In northeastern China, tigers were ] and active at night with activity peaking at dawn and dusk; they were largely active at the same time as their prey.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Yang, H. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Han, S. |author3=Xie, B. |author4=Mou, P. |author5=Kou, X. |author6=Wang, T. |author7=Ge, J. |author8=Feng, L. |year=2019 |title=Do prey availability, human disturbance and habitat structure drive the daily activity patterns of Amur tigers (''Panthera tigris altaica'')? |journal=Journal of Zoology |volume=307 |issue=2 |pages=131–140 |doi=10.1111/jzo.12622 |s2cid=92736301}}</ref> | |||

| The tiger is a powerful swimmer and easily transverses rivers as wide as {{cvt|8|km}}; it immerses in water, particularly on hot days.<ref name=Miquelle/> In general, it is less capable of climbing trees than many other cats due to its size, but cubs under 16 months old may routinely do so.{{sfn|Thapar|2004|pp=26, 64–66}} An adult was recorded climbing {{cvt|10|m}} up a smooth ].<ref name=Mazak1981/> | |||

| ==Hunting methods== | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Social spacing=== | |||

| Tigers often ambush their prey as other cats do, overpowering their prey from any angle, using their body size and strength to knock prey off balance. Once prone, the tiger bites the back of the neck, often breaking the prey's ], piercing the ], or severing the ] or ]. For large prey, a bite to the throat is preferred. After biting, the tiger then uses its muscled forelimbs to hold onto the prey, bringing it to the ground. The tiger remains latched onto the neck until its prey dies. | |||

| Adult tigers lead largely solitary lives within ]s or ], the size of which mainly depends on prey abundance, geographic area and sex of the individual. Males and females defend their home ranges from those of the same sex and the home range of a male encompasses that of multiple females.<ref name=Mazak1981/><ref name=Miquelle/> Two females in the ] had home ranges of {{cvt|10.6|and|14.1|km2}}.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Barlow, A. C. D. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Smith, J. L. D. |author3=Ahmad, I. U. |author4=Hossain, A. N. M. |author5=Rahman, M. |author6=Howlader, A. |year=2011 |title=Female tiger ''Panthera tigris'' home range size in the Bangladesh Sundarbans: the value of this mangrove ecosystem for the species' conservation |journal=Oryx |volume=45 |issue=1 |pages=125–128 |doi=10.1017/S0030605310001456 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| In ], the home ranges of five reintroduced females varied from {{cvt|53-67|km2}} in winter to {{cvt|55-60|km2}} in summer and to {{cvt|46-94|km2}} during the ]; three males had {{cvt|84-147|km2}} large home ranges in winter, {{cvt|82-98|km2}} in summer and {{cvt|81-118|km2}} during monsoon seasons.<ref name=Sarkar2016>{{cite journal |author1=Sarkar, M. S. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Ramesh, K. |author3=Johnson, J. A. |author4=Sen, S. |author5=Nigam, P.|author6=Gupta, S. K.|author7=Murthy, R. S. |author8=Saha, G. K. |year=2016 |title=Movement and home range characteristics of reintroduced tiger (''Panthera tigris'') population in Panna Tiger Reserve, central India |journal=European Journal of Wildlife Research |volume=62 |issue=5 |pages=537–547 |doi=10.1007/s10344-016-1026-9|bibcode=2016EJWR...62..537S |s2cid=254187854}}</ref> | |||

| In ], 14 females had home ranges {{cvt|248-520|km2}} and five resident males of {{cvt|847-1923|km2}} that overlapped with those of up to five females.<ref name=Goodrich_2010>{{cite journal |author1=Goodrich, J. M. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Miquelle, D. G. |author3=Smirnov, E. M. | author4=Kerley, L. L. |author5=Quigley, H. B. |author6=Hornocker, M. G. |year=2010 |title=Spatial structure of Amur (Siberian) tigers (''Panthera tigris altaica'') on Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Zapovednik, Russia |journal=Journal of Mammalogy |volume=91 |issue=3 |pages=737–748 |doi=10.1644/09-mamm-a-293.1 |doi-access=free}}</ref> When tigresses in the same reserve had cubs of up to four months of age, they reduced their home ranges to stay near their young and steadily enlarged them until their offspring were 13–18 months old.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Klevtcova, A. V. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Miquelle, D. G. |author3=Seryodkin, I. V. |author4=Bragina, E. V. |author5=Soutyrina, S. V. |author6=Goodrich, J. M. |year=2021 |title=The influence of reproductive status on home range size and spatial dynamics of female Amur tigers |journal=Mammal Research |volume=66 |pages=83–94 |doi=10.1007/s13364-020-00547-2}}</ref> | |||

| {{image frame | |||

| |caption=]s spraying urine (above) and rubbing against a tree to mark territory | |||

| |content= | |||

| {{CSS image crop | |||

| |Image = Tiger spray marking. DavidRaju 1.jpg | |||

| |bSize = 300 | |||

| |cWidth = 150 | |||

| |cHeight = 150 | |||

| |oTop = 30 | |||

| |oLeft = 30 | |||

| }}{{CSS image crop | |||

| |Image = Bijili (A tiger in Ranthambore National Park, 2016) 1.jpg | |||

| |bSize = 150 | |||

| |cWidth = 150 | |||

| |cHeight = 150 | |||

| |oTop = 30 | |||

| |oLeft = 0 | |||

| }}|width=150}} | |||

| The tiger is a long-ranging species and individuals disperse over distances of up to {{cvt|650|km|mi}} to reach tiger populations in other areas.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Joshi, A. |author2=Vaidyanathan, S. |author3=Mondol, S. |author4=Edgaonkar, A. |author5=Ramakrishnan, U. |year=2013 |title=Connectivity of Tiger (''Panthera tigris'') Populations in the Human-Influenced Forest Mosaic of Central India |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=8 |issue=11 |pages=e77980 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0077980 |pmid=24223132 |pmc=3819329 |bibcode=2013PLoSO...877980J |doi-access=free |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> Young tigresses establish their first home ranges close to their mothers' while males migrate further than their female counterparts.{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=76}} Four ] females in Chitwan dispersed between {{cvt|0|and|43.2|km|mi}} and 10 males between {{cvt|9.5|and|65.7|km}}.<ref name=Smith1993>{{cite journal |last=Smith |first=J. L. D. |year=1993 |title=The role of dispersal in structuring the Chitwan tiger population |volume=124 |journal=Behaviour |issue=3 |pages=165–195 |doi=10.1163/156853993X00560}}</ref> A subadult male lives as a transient in another male's home range until he is older and strong enough to challenge the resident male.{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=76}}{{sfn|Mills|2004|pp=54–55}} Tigers mark their home ranges by ] on vegetation and rocks, clawing or ] trees and marking trails with ], ] secretions and ground scrapings.<ref name=Miquelle/><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Burger |first1=B. V. |last2=Viviers |first2=M. Z. |last3=Bekker |first3=J. P. I. |last4=Roux |first4=M. |last5=Fish |first5=N. |last6=Fourie |first6=W. B. |last7=Weibchen |first7=G. |year=2008 |title=Chemical characterization of territorial marking fluid of male Bengal tiger, ''Panthera tigris'' |journal=Journal of Chemical Ecology |volume=34 |issue=5 |pages=659–671 |doi=10.1007/s10886-008-9462-y |pmid=18437496 |bibcode=2008JCEco..34..659B |hdl-access=free |hdl=10019.1/11220 |s2cid=5558760 |name-list-style=amp |url=https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=586948b8396932dd13d9e5a880e77cb7618a273f |access-date=29 June 2023}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Smith|first1=J. L. D. |last2=McDougal|first2=C. |last3=Miquelle |first3=D. |year=1989 |title=Scent marking in free-ranging tigers, ''Panthera tigris'' |url=|journal=Animal Behaviour |volume=37|pages=1–10 |doi=10.1016/0003-3472(89)90001-8 |s2cid=53149100 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref>{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=105}} Scent markings also allow an individual to pick up information on another's identity. Unclaimed home ranges, particularly those that belonged to a deceased individual, can be taken over in days or weeks.<ref name=Miquelle/> | |||

| Male tigers are generally less tolerant of other males within their home ranges than females are of other females. Disputes are usually solved by intimidation rather than fighting. Once ] has been established, a male may tolerate a subordinate within his range, as long as they do not come near him. The most serious disputes tend to occur between two males competing for a female in ].{{sfn|Mills|2004|pp=85–86}} Though tigers mostly live alone, relationships between individuals can be complex. Tigers are particularly social at kills and a male tiger will sometimes share a carcass with the females and cubs within this home range and unlike male lions, will allow them to feed on the kill before he is finished with it. However, a female is more tense when encountering another female at a kill.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|pp=244–251}}{{sfn|Mills|2004|p=89}} | |||

| Powerful swimmers, tigers are known to kill prey while swimming. Some tigers have even ambushed boats for the fishermen on board or their catches of fish.{{fact}} | |||

| ===Communication=== | |||

| The majority of tigers never hunt humans except in desperation. Probably only 3 or 4 tigers out of every 1000 tigers kill a person as prey in their lifetimes. The usual man-eater is an injured or ill tiger which can no longer catch its usual prey and must resort to a smaller, slower target. Like most other large predators they generally recognize humans as unsuitable prey because of the danger of being hunted by a predator themselves (a human possessing spears or firearms). The ] mangrove swamps of ] have had a higher incidence of man-eaters, where some healthy tigers have been known to hunt humans as prey. | |||

| {{Multiple image |align= right |direction=vertical |total_width=150|image1=Panthera tigris altaica 28 - Buffalo Zoo (1).jpg|caption1=Siberian tiger baring teeth as a sign of aggression|image2=Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) vocalising.webm |caption2=Captive ] roaring|alt=Image of tiger barring teeth (top) and a video of one roaring at a zoo}} | |||

| During friendly encounters and bonding, tigers ] each other's bodies.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|pp=262–263}} Facial expressions include the "defence threat", which involves a wrinkled face, bared teeth, pulled-back ears and widened pupils.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=263}}<ref name=Mazak1981/> Both males and females show a ], a characteristic curled-lip grimace, when smelling urine markings. Males also use the flehmen to detect the markings made by tigresses in oestrus.<ref name=Mazak1981/> Tigers will move their ears around to display the white spots, particularly during aggressive encounters and between mothers and cubs.<ref name=WCW/> They also use their tails to signal their mood. To show cordiality, the tail sticks up and sways slowly, while an apprehensive tiger lowers its tail or wags it side-to-side. When calm, the tail hangs low.{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=29}} | |||

| Tigers are normally silent but can produce numerous vocalisations.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=256}}{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=99}} They ] to signal their presence to other individuals over long distances. This vocalisation is forced through an open mouth as it closes and can be heard {{cvt|3|km}} away. They roar multiple times in a row and others respond in kind. Tigers also roar during mating and a mother will roar to call her cubs to her. When tense, tigers moan, a sound similar to a roar but softer and made when the mouth is at least partially closed. Moaning can be heard {{cvt|400|m}} away.<ref name="Mazak1981" />{{sfn|Schaller|1967|pp=258–261}} Aggressive encounters involve ], ] and hissing.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=261}} An explosive "coughing roar" or "coughing snarl" is emitted through an open mouth and exposed teeth.<ref name=Mazak1981/>{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=261}}<ref name=WCW>{{Cite book |last1=Sunquist |first1=M. E. |year=2002 |last2=Sunquist |first2=F. |name-list-style=amp |title=Wild Cats of the World |publisher=University of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |isbn=978-0-226-77999-7 |chapter=Tiger ''Panthera tigris'' (Linnaeus, 1758) |pages=343–372 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IF8nDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA320}}</ref> In friendlier situations, tigers ], a soft, low-frequency snorting sound similar to ] in smaller cats.<ref>{{Cite journal |doi=10.1023/A:1020620121416 |year=1999| last1=Peters |first1=G. |last2=Tonkin-Leyhausen |first2=B. A. |name-list-style=amp |title=Evolution of acoustic communication signals of mammals: Friendly close-range vocalizations in Felidae (Carnivora) |journal=Journal of Mammalian Evolution |volume=6 |issue=2 |pages=129–159 |s2cid=25252052}}</ref> Tiger mothers communicate with their cubs by grunting, while cubs call back with ]s.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|pp=257–258}} When startled, they "woof". They produce a deer-like "pok" sound for unknown reasons, but most often at kills.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|pp=256–258}}{{sfn|Mills|2004|p=62}} | |||

| In the wild, tigers can leap as high as 5 m and as far as 9-10 m, making them one of the highest-jumping mammals (just slightly behind cougars in jumping ability). | |||

| === Hunting and diet === | |||

| They have been reported to carry domestic livestock weighing 50 kg while easily jumping over fences 2 m high. Their forelimbs, massive and heavily muscled, are used to hold tightly onto the prey and to avoid being dislodged, especially by large prey such as ]s. ]s and ] weighing over a ton have been killed by tigers weighing about a sixth as much. A single tremendous blow of the paw can kill a full-grown ] or ], or can heavily injure a 150 kg ]. | |||

| ] in ]|alt=Tiger attacking a sambar deer from behind, pulling on its back]] | |||

| The tiger is a ] and an ] feeding mainly on large and medium-sized ungulates, with a preference for ], ], ], ] and ].<!--Please do not add any more species to this sentence.--><ref name=Hayward>{{cite journal |last1=Hayward |first1=M. W. |last2=Jędrzejewski |first2=W. |last3=Jędrzejewska |first3=B. |year=2012 |title=Prey preferences of the tiger ''Panthera tigris''|journal=Journal of Zoology |volume=286 |issue=3 |pages=221–231 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00871.x |name-list-style=amp}}</ref><ref name=Steinmetz_al2021>{{cite journal |author1=Steinmetz, R. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Seuaturien, N. |author3=Intanajitjuy, P. |author4=Inrueang, P. |author5=Prempree, K. |year=2021 |title=The effects of prey depletion on dietary niches of sympatric apex predators in Southeast Asia |journal=Integrative Zoology |volume=16 |issue=1 |pages=19–32 |doi=10.1111/1749-4877.12461 |pmid=32627329}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Variar, A. S. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Anoop, N. R. |author3=Komire, S. |author4=Vinayan, P. A. |author5=Sujin, N. S. |author6=Raj, A. |author7=Prasadan, P. K. |year=2023 |title=Prey selection by the Indian tiger (''Panthera tigris tigris'') outside protected areas in Indias Western Ghats: implications for conservation |journal=Food Webs |volume=34 |page=e00268 |doi=10.1016/j.fooweb.2022.e00268|bibcode=2023FWebs..3400268V }}</ref> | |||

| ] and body weight of prey species are assumed to be the main criteria for the tiger's prey selection, both inside and outside protected areas.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Biswas, S. |name-list-style=amp |author2=Kumar, S. |author3=Bandhopadhyay, M. |author4=Patel, S. K. |author5=Lyngdoh, S. |author6=Pandav, B. |author7=Mondol, S. |year=2023 |title=What drives prey selection? Assessment of Tiger (''Panthera tigris'') food habits across the Terai-Arc Landscape, India |journal=Journal of Mammalogy |volume=104 |issue=6 |pages=1302–1316 |doi=10.1093/jmammal/gyad069}}</ref> | |||

| It also preys opportunistically on smaller species like ]s, ] and other ground-based birds, ]s and fish.<ref name=Mazak1981/><ref name=Miquelle/> Occasional attacks on ]s and ]es have also been reported.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Karanth, K. U. |year=2003 |title=Tiger ecology and conservation in the Indian subcontinent |journal=Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society |volume=100 |issue=2 & 3 |pages=169–189 |url=http://repository.ias.ac.in/89489/1/50p.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| More often, tigers take the more vulnerable calves.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Karanth, K. U. |author2=Nichols, J. D. |name-list-style=amp |year=1998 |title=Estimation of tiger densities in India using photographic captures and recaptures |journal=Ecology |volume=79 |issue=8 |pages=2852–2862 |doi=10.1890/0012-9658(1998)0792.0.CO;2 |jstor=176521 |url=http://erepo.usiu.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11732/758/Estimation%20of%20tiger%20densities%20in%20India%20using%20photographic%20captures%20and%20recaptures.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y |access-date=16 December 2021 |archive-date=27 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221127044620/http://erepo.usiu.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11732/758/Estimation%20of%20tiger%20densities%20in%20India%20using%20photographic%20captures%20and%20recaptures.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| They sometimes prey on livestock and dogs in close proximity to settlements.<ref name=Mazak1981/> Tigers occasionally consume vegetation, fruit and minerals for ] and supplements.<ref name=Perry>{{cite book |author=Perry, R. |title=The World of the Tiger |year=1965 |publisher=Cassell |place=London |pages=133–134 |asin=B0007DU2IU}}</ref> | |||

| Tigers learn to hunt from their mothers, though the ability to hunt may be partially inborn.<ref name="Fàbregas">{{cite journal |last1=Fàbregas |first1=M. C. |last2=Fosgate|first2=G. T. |last3=Koehler |first3=G. M.|year=2015|title=Hunting performance of captive-born South China tigers (''Panthera tigris amoyensis'') on free-ranging prey and implications for their reintroduction |journal=Biological Conservation |volume=192 |pages=57–64 |doi=10.1016/j.biocon.2015.09.007 |bibcode=2015BCons.192...57F |hdl=2263/50208 |hdl-access=free |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> Depending on the size of the prey, they typically kill weekly though mothers must kill more often.<ref name=Sunquist2010/> Families hunt together when cubs are old enough.{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=63}} They search for prey using vision and hearing.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|pp=284–285}} A tiger will also wait at a watering hole for prey to come by, particularly during hot summer days.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=288}}{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=120}} It is an ambush predator and when approaching potential prey, it crouches with the head lowered and hides in foliage. It switches between creeping forward and staying still. A tiger may even doze off and can stay in the same spot for as long as a day, waiting for prey and launch an attack when the prey is close enough,{{sfn|Thapar|2004|pp=119–120, 122}} usually within {{cvt|30|m}}.<ref name=Sunquist2010/> If the prey spots it before then, the cat does not pursue further.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=288}} A tiger can sprint {{cvt|56|km/h|mph}} and leap {{cvt|10|m}};{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=287}}{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=23}} it is not a long-distance runner and gives up a chase if prey outpaces it over a certain distance.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=288}} | |||

| ==Biology and ecology== | |||

| ] in ]|alt=Two tigers attacking a boar]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The tiger attacks from behind or at the sides and tries to knock the target off balance. It latches onto prey with its forelimbs, twisting and turning during the struggle and tries to pull it to the ground. The tiger generally applies a ] until its victim dies of ].<ref name=Mazak1981/>{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=121}}{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=295}}{{sfn|Mills|2004|p=24}} It has an average bite force at the canine tips of 1234.3 ].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Christiansen, P. |year=2007 |title=Canine morphology in the larger Felidae: implications for feeding ecology |journal=Biological Journal of the Linnean Society |volume=91 |issue=4 |pages=573–592 |doi=10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00819.x |doi-access=free}}</ref> Holding onto the throat puts the cat out of reach of horns, antlers, tusks and hooves.{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=121}}{{sfn|Schaller|1967|pp=295–296}} Tigers are adaptable killers and may use other methods, including ripping the throat or breaking the neck. Large prey may be disabled by a bite to the back of the ], severing the tendon. Swipes from the large paws are capable of stunning or breaking the skull of a ].{{sfn|Thapar|2004|p=126}} They kill small prey with a bite to the back of the neck or head.{{sfn|Schaller|1967|p=289}}<ref name=Sunquist2010/> Estimates of the ] for hunting tigers range from a low of 5% to a high of 50%. They are sometimes killed or injured by large or dangerous prey like gaur, buffalo and boar.<ref name=Sunquist2010/> | |||