| Revision as of 06:50, 28 November 2017 view sourceJinerea (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers45,798 editsm Reverted edits by 41.78.74.30 (talk) to last version by Soupforone← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:32, 12 January 2025 view source Solanif (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users593 edits →Clans: Rv self link, changed llink to correct page.Tag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{About|the Somali ethnic group|the general population of the Federal Republic of Somalia|Demographics of Somalia|other uses|Somali (disambiguation)}} |

{{short description|Cushitic ethnic group native to the Horn of Africa}} | ||

| {{About|the Somali ethnic group|the general population of the Federal Republic of Somalia|Demographics of Somalia|other uses|Somali (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | {{Infobox ethnic group | ||

| |group |

| group = Somali people | ||

| | flag = | |||

| <!-- ] --> | |||

| | flag_caption = | |||

| |image = File:Somali_map.jpg | |||

| | population = 26.8 million<ref name="WorldData.info">{{Cite web|url=https://www.worlddata.info/languages/somali.php | title=Somali, worldwide distribution | access-date=16 July 2023}}</ref> | |||

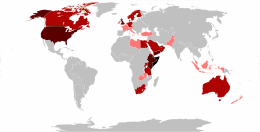

| |caption = Traditional area inhabited by the Somali ethnic group | |||

| ] | |||

| |population = {{circa}} 20–21 million | |||

| |popplace = ]<!-- regional parameter --> | | popplace = ]<!-- regional parameter --> | ||

| <!-- ] -->| image = Greater Somalia (orthographic projection).svg | |||

| |region1 = {{flagcountry|Somalia}} | |||

| | caption = <small>Traditional area inhabited by the Somali ethnic group</small> | |||

| |pop1 = 12 million | |||

| | region1 = {{flag|Somalia}}{{efn|including Somaliland}} | |||

| |ref1 = <ref name="UNFPA Somali Population Survey 2014">. Somalia.unfpa.org (06 April 2014). Retrieved 06 October 2016.</ref> | |||

| | pop1 = 18,143,378 (2023) | |||

| |region2 = {{flagcountry|Ethiopia}} | |||

| | ref1 = <ref>{{cite web |url=https://data.worldbank.org/country/SO |title=World Bank Open Data |access-date=4 April 2024 |archive-date=30 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231130043543/https://data.worldbank.org/country/SO |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Lewis|first=I. M.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k3QwAQAAIAAJ|title=Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar, and Saho|date=1998|publisher=Red Sea Press|isbn=978-1-56902-104-0|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| |pop2 = 4.6 million | |||

| | region2 = {{flag|Ethiopia}} | |||

| |ref2 = <ref name=CSA>, first draft, Table 5. Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia</ref> | |||

| | pop2 = 4,581,793 (2007) | |||

| |region3 = {{flagcountry|Kenya}} | |||

| | ref2 = <ref name="CSA">{{cite web|title=Table 2.2 Percentage distribution of major ethnic groups: 2007|page=16|url=http://www.csa.gov.et/pdf/Cen2007_firstdraft.pdf|work=Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results|publisher=Population Census Commission|access-date=21 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090325050115/http://www.csa.gov.et/pdf/Cen2007_firstdraft.pdf|archive-date=25 March 2009}}</ref> | |||

| |pop3 = 2.4 million | |||

| | region3 = {{flag|Kenya}} | |||

| |ref3 = <ref name="Kengov">{{cite web|title=2009 POPULATION & HOUSING CENSUS RESULTS |url=http://www.knbs.or.ke/docs/PresentationbyMinisterforPlanningrevised.pdf |publisher=Ministry of State for Planning, National Development and Vision 2030 |accessdate=17 September 2014 |deadurl=unfit |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130810185221/http://www.knbs.or.ke/docs/PresentationbyMinisterforPlanningrevised.pdf |archivedate=10 August 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| | pop3 = 2,780,502 (2019) | |||

| |region4 = {{flagcountry|Djibouti}} | |||

| | ref3 = <ref name =Census2019>{{cite web|url=https://www.knbs.or.ke/?wpdmpro=2019-kenya-population-and-housing-census-volume-iv-distribution-of-population-by-socio-economic-characteristics&wpdmdl=5730&ind=7HRl6KateNzKXCJaxxaHSh1qe6C1M6VHznmVmKGBKgO5qIMXjby1XHM2u_swXdiR|title=2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Volume IV: Distribution of Population by Socio-Economic Characteristics|date=December 2019|access-date=24 March 2020|publisher=Kenya National Bureau of Statistics|page=423|df=dmy}}</ref> | |||

| |pop4 = 524,000 | |||

| | region4 = {{flag|Djibouti}} | |||

| |ref4 = <ref name=Ethnologue> – Ethnologue.com</ref> | |||

| | pop4 = 560,000 (2024) | |||

| |region5 = {{flagcountry|Yemen}} | |||

| | ref4 = <ref name=JoshDJ> – Joshuaproject.net</ref> | |||

| |pop5 = 200,000 | |||

| | region5 = {{flag|Yemen}} | |||

| |ref5 = <ref name="Twhr">{{cite book|last=Shire|first=Saad A.|title=Transactions with Homeland: Remittance|publisher=Bildhaan|url=http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1034&context=bildhaan}}: *N.B. Somali migrant population, Middle East including Yemen.</ref> | |||

| | pop5 = 500,000 (2014) | |||

| |region6 = {{flagcountry|United Arab Emirates}} | |||

| | ref5 = <ref name=Gramer>{{cite news|url=https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/17/apache-helicopter-guns-down-boat-full-of-somali-refugees-fleeing-yemen/|title=Apache Helicopter Guns Down Boat Full of Somali Refugees Fleeing Yemen|first=Robbie|last=Gramer|work=Foreign Policy|date=17 March 2017|access-date=24 April 2020}}</ref> | |||

| |pop6 = 130,000 | |||

| | region7 = {{flag|United States}} | |||

| |ref6 = <ref name="UAEData">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/country/AE|title=Ethnologue United Arab Emirates|work=Ethnologue|access-date=2017-07-16}}</ref> | |||

| | pop7 = 169,799 (2023) | |||

| |region7 = {{flagcountry|United States}} | |||

| | ref7 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=B04006&t=Ancestry&d=ACS%201-Year%20Estimates%20Detailed%20Tables&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B04006&hidePreview=false|title=American Community Survey – 1-Year Estimates – Table B04006|publisher=U.S. Census Bureau|website=data.census.gov}}</ref> | |||

| |pop7 = 129,018 | |||

| | region8 = {{flag|Libya}} | |||

| |ref7 = <ref name="USCensus">{{Cite web|url=https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_5YR_B04006&prodType=table|title=American FactFinder - Results|last=Bureau|first=U.S. Census|website=factfinder.census.gov|language=en|access-date=2017-08-04}}</ref> | |||

| | pop8 = 112,000 (2020) | |||

| |region8 = {{flagcountry|United Kingdom}} | |||

| | ref8 = <ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination|title=Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination|date=February 10, 2014|website=migrationpolicy.org|access-date=April 16, 2024|archive-date=April 14, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414153852/https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |pop8 = 114,000 | |||

| | |

| region6 = {{flag|United Kingdom}} | ||

| | pop6 = 176,645 (2021) | |||

| |region9 = {{flagcountry|Sweden}} | |||

| | ref6 = <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/articles/somalipopulationsenglandandwales/census2021#:~:text=In%20Census%202021%2C%20176%2C645%20usual,0.3%25%20of%20the%20population|title=Somali Population of England and Wales 2021|work=2021 Statistics for Ethnicity in England and Wales|publisher=]| access-date=14 June 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |pop9 = 63,853 | |||

| | region9 = {{flag|United Arab Emirates}} | |||

| |ref9 = <ref name="SCB">{{cite web|title=Statistics Sweden - Foreign-born and born in Sweden|url=http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/sq/30271}}</ref> | |||

| | pop9 = 101,000 | |||

| |region10 = {{flagcountry|Canada}} | |||

| | ref9 = <ref name="UAEData">{{cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/country/AE|title=Ethnologue United Arab Emirates|work=Ethnologue|access-date=21 February 2018}}</ref> | |||

| |pop10 = 62,550 | |||

| | region10 = {{flag|Sweden}} | |||

| |ref10 = <ref>http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=01&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=Canada&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=Ethnic%20origin&TABID=1</ref> | |||

| | pop10 = 68,290 | |||

| |region11 = {{flagcountry|Norway}} | |||

| | ref10 = <ref name="SCB">{{cite web|title=Statistics Sweden – Foreign-born and born in Sweden|url=http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/?rxid=1bcec35a-5bd2-4a4a-9609-668463972a1c}}</ref> | |||

| |pop11 = 42,217 | |||

| | region12 = {{flag|Canada}} | |||

| |ref11 = <ref name="NorwayCensus">{{cite web|url=http://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/innvbef/aar/2017-03-02?fane=tabell&sort=nummer&tabell=297399|title= | |||

| | pop12 = 65,550 | |||

| Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, 1 January 2016}}</ref> | |||

| | ref12 = <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810035501&geocode=A000011124 | title=Census Profile, 2021 Census – Ethnic or Cultural Background – Canada [ Country] | date=8 July 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |region12 = {{flagcountry|South Africa}} | |||

| | |

| region11 = {{flag|Tanzania}} | ||

| | pop11 = 66,000 | |||

| |ref12 = <ref name="Mhiahlusiilrj">{{cite web|last=Jinnah|first=Zaheera|title=Making Home in a Hostile Land: Understanding Somali Identity, Integration, Livelihood and Risks in Johannesburg|url=http://www.krepublishers.com/02-Journals/JSSA/JSSA-01-0-000-10-Web/JSSA-01-0-000-10-PDF/JSSA-01-1-2-091-10-012-Jinnah-Z/JSSA-01-1-2-091-10-012-Jinnah-Z-Tt.pdf|work=J Sociology Soc Anth, 1 (1-2): 91-99 (2010)|publisher=KRE Publishers|accessdate=6 March 2014}}</ref> | |||

| | ref11 = {{cn|date=December 2024}} | |||

| |region13 = {{flagcountry|Netherlands}} | |||

| | |

| region16 = {{flag|Norway}} | ||

| | pop16 = 43,196 | |||

| |ref13 = <ref name=NetherlandsCensus>{{cite web|url=http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=37325eng&D1=a&D2=a&D3=0&D4=0&D5=187&D6=a&LA=EN&HDR=T&STB=G2,G1,G3,G5,G4&VW=T|title=CBS StatLine - Population; sex, age, origin and generation, 1 January|work=cbs.nl}}</ref> | |||

| | ref16 = <ref name="NorwayCensus">{{cite web|url=http://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/innvbef|title=Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents}}</ref> | |||

| |region14 = {{flagcountry|Saudi Arabia}} | |||

| | |

| region14 = {{flag|Uganda}} | ||

| | pop14 = 51,536 | |||

| |ref14 = <ref name="SDRD">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/country/SA|title=Ethnologue Saudi Arabia|work=Ethnologue|access-date=2017-07-12}}</ref> | |||

| | ref14 = <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.statista.com/statistics/1241293/refugees-in-uganda-by-origin/|title=Refugees in Uganda by country of origin 2024|publisher=Statista|access-date=8 July 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |region15 = {{flagcountry|Germany}} | |||

| | region18 = {{flag|South Africa}} | |||

| |pop15 = 33,900 | |||

| | pop18 = 27,000–40,000 | |||

| |ref15 = <ref name=GermanyCensus>{{cite web|url=https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1221/umfrage/anzahl-der-auslaender-in-deutschland-nach-herkunftsland/|title=Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland |publisher=Statista}}</ref> | |||

| | ref18 = <ref name="Mhiahlusiilrj">{{cite web|last=Jinnah|first=Zaheera|title=Making Home in a Hostile Land: Understanding Somali Identity, Integration, Livelihood and Risks in Johannesburg|url=http://www.krepublishers.com/02-Journals/JSSA/JSSA-01-0-000-10-Web/JSSA-01-0-000-10-PDF/JSSA-01-1-2-091-10-012-Jinnah-Z/JSSA-01-1-2-091-10-012-Jinnah-Z-Tt.pdf|work=J Sociology Soc Anth, 1 (1–2): 91–99 (2010)|publisher=KRE Publishers|access-date=6 March 2014}}</ref> | |||

| |region16 = {{flagcountry|Egypt}} | |||

| | |

| region17 = {{flag|Netherlands}} | ||

| | pop17 = 41,064 | |||

| |ref16 = <ref name="UNDESA">{{cite web|title=United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2015). Trends in International Migrant Stock: Migrants by Destination and Origin |url=http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates15.shtml}}</ref> | |||

| | ref17 = <ref name=NetherlandsCensus>{{cite web|url=http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=37325eng&D1=a&D2=a&D3=0&D4=0&D5=187&D6=a&LA=EN&HDR=T&STB=G2,G1,G3,G5,G4&VW=T|title=Population; sex, age, origin and generation, 1 January|work=CBS StatLine|publisher=Statistics Netherlands}}</ref> | |||

| |region17 = {{flagcountry|Denmark}} | |||

| | |

| region13 = {{flag|Germany}} | ||

| | pop13 = 60,295 | |||

| |ref17 = <ref name=DenmarkCensus>{{cite web|url=http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1280|title=StatBank Denmark|work=statbank.dk}}</ref> | |||

| | ref13 = <ref name=GermanyCensus>{{cite web|url=https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1221/umfrage/anzahl-der-auslaender-in-deutschland-nach-herkunftsland/|title=Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland |publisher=Statista}}</ref> | |||

| |region18 = {{flagcountry|Finland}} | |||

| | |

| region15 = {{flag|Saudi Arabia}} | ||

| | pop15 = 45,710 | |||

| |ref18 = <ref name="FinCensus"></ref> | |||

| | ref15 = <ref name="GLMM">{{Cite web|url=https://gulfmigration.grc.net/saudi-arabia-sub-saharan-african-population-by-country-of-citizenship-and-sex-census-2022/|title=Sub-Saharan-African Population by Country of Citizenship in Saudi Arabia 2022 Census|date=13 June 2024 |publisher=Gulf Labour Markets and Migration|access-date=18 August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |region19 = {{flagcountry|Australia}} | |||

| | |

| region19 = {{flag|Finland}} | ||

| | pop19 = 24,647 | |||

| |ref19 = <ref name="AustraliaCensus">{{cite web|title=Table 5. Ancestry by State and Territory of Usual Residence, Count of persons - 2016(a)(b)|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&207103%20-%20Cultural%20Diversity.xls&2071.0&Data%20Cubes&21F50C2D0457EF67CA2581620019845C&0&2016&20.07.2017&Latest|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|date=20 July 2017|accessdate=4 August 2017}}</ref> | |||

| | ref19 = <ref name="FinCensus">{{cite web|url=https://statfin.stat.fi/PxWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_11rm.px/|title=Statistics Finland|publisher=stat.fi}}</ref> | |||

| |region20 = {{flagcountry|Italy}} | |||

| | |

| region20 = {{flag|Egypt}} | ||

| | pop20 = 21,000 | |||

| |ref20 = <ref name="ItalyCensus">{{cite web|url=http://demo.istat.it/str2016/|title=Statistiche demografiche ISTAT|work=istat.it}}</ref> | |||

| | ref20 = <ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination|title=Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination|date=February 10, 2014|website=migrationpolicy.org|access-date=April 16, 2024|archive-date=April 14, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414153852/https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination/|url-status=live}}</ref>–200,000<ref name="IOM">{{Cite web|url=https://egypt.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1021/files/documents/migration-stock-in-egypt-june-2022_v4_eng.pdf| title=Migration Stock in Egypt 2022| publisher=International Organization for Migration (IOM)|last=The UN Migration agency|access-date=12 July 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |region21 = {{flagcountry|Switzerland}} | |||

| | |

| region22 = {{flag|Denmark}} | ||

| | pop22 = 11,041 | |||

| |ref21 = <ref name="SwissCensus">{{cite web|url=https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/migration-intergration.assetdetail.325742.html|title=Federal Statistical Office}}</ref> | |||

| | ref22 = <ref name=DenmarkCensus>{{cite web|url=http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1280|title=StatBank Denmark|work=statbank.dk}}</ref> | |||

| |region22 = {{flagcountry|Austria}} | |||

| | |

| region21 = {{flag|Australia}} | ||

| | pop21 = 18,401 | |||

| |ref22 = {{lower|<ref name="AustriaCensus">{{cite web|url=http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bevoelkerung/bevoelkerungsstruktur/bevoelkerung_nach_staatsangehoerigkeit_geburtsland/index.html|title=Statistik Austria}}</ref>}} | |||

| | ref21 = <ref name="AustraliaCensus">{{cite web|title=Table 5. Ancestry by State and Territory of Usual Residence, Count of persons – 2016(a)(b)|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&207103%20-%20Cultural%20Diversity.xls&2071.0&Data%20Cubes&21F50C2D0457EF67CA2581620019845C&0&2016&20.07.2017&Latest|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|date=20 July 2017|access-date=4 August 2017}}</ref> | |||

| |region23 = {{flagcountry|Belgium}} | |||

| | |

| region23 = {{flag|Italy}} | ||

| | pop23 = 9,349 | |||

| |ref23 = {{lower|<ref name="Jan Hertogen">{{cite news|first=J|last=Hertogen|title=Inwoners van vreemde afkomst in België|url=http://www.npdata.be/BuG/155-Vreemde-afkomst/Vreemde-afkomst.htm}}</ref>}} | |||

| | ref23 = <ref name="ItalyCensus">{{cite web|title=Statistiche demografiche ISTAT | |||

| |region24 = {{flagcountry|Pakistan}} | |||

| |url=https://www.tuttitalia.it/statistiche/cittadini-stranieri-2023/|publisher=Tuttitalia Cittadini stranieri al 2022|access-date=2 July 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |pop24 = 2,500 | |||

| | region27 = {{flag|Austria}} | |||

| |ref24 = {{lower|<ref name="Fakhr">{{cite news|last=Fakhr|first=Alhan|title=Insecure once again|url=http://jang.com.pk/thenews/jul2012-weekly/nos-15-07-2012/dia.htm#6|accessdate=10 November 2013|newspaper=Daily Jang|date=15 July 2012}}</ref>}} | |||

| | pop27 = 7,101 | |||

| |region25 = {{flagcountry|New Zealand}} | |||

| | ref27 = <ref name="AustriaCensus">{{cite web|url=http://www.statistik.at/wcm/idc/idcplg?IdcService=GET_PDF_FILE&RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased&dDocName=071715|title=Bevölkerung zu Jahresbeginn 2002–2021 nach detaillierter Staatsangehörigke|publisher=Statistik Austria|access-date=2 March 2021}}</ref> | |||

| |pop25 = 1,617 | |||

| | region25 = {{flag|Switzerland}} | |||

| |ref25 = <ref name="NewZealandCensus">{{cite web|url=http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/ethnic-profiles.aspx?request_value=24790&parent_id=24761&tabname=#24790|title=Ethnic group profiles|work=stats.govt.nz}}</ref> | |||

| | pop25 = 8,625 | |||

| |region26 = {{flagcountry|Ireland}} | |||

| | ref25 = <ref name="SwissCensus">{{cite web|url=https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/#_Tablesandgraphs|title=Federal Statistical Office|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170417072647/https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/migration-intergration.assetdetail.325742.html|archive-date=17 April 2017}}</ref> | |||

| |pop26 = 1,495 | |||

| | region26 = {{flag|France}} | |||

| |ref26 = {{lower|<ref name="IrelandCensus">{{Cite web|url=http://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?Maintable=EY025&Planguage=0|title=Population Usually Resident and Present in the State who Speak a Language other than English or Irish at Home 2011 to 2016 by Birthplace, Language Spoken, Age Group and CensusYear - StatBank - data and statistics|website=www.cso.ie|access-date=2017-07-12}}</ref>}} | |||

| | pop26 = 8,000 | |||

| |langs = ] | |||

| | ref26 = <ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination|title=Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination|date=February 10, 2014|website=migrationpolicy.org|access-date=April 16, 2024|archive-date=April 14, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414153852/https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |rels = ] (<small>], ]</small>) | |||

| | region28 = {{flag|Turkey}} | |||

| |related = {{hlist| ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ]-] | ] | other ]-speaking peoples<ref name="Joireman">{{cite book|last=Joireman|first=Sandra F.|title=Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development|year=1997|publisher=Universal-Publishers|page=1|isbn=1581120001}}</ref>}} | |||

| | pop28 = 5,518 | |||

| | ref28 = <ref name="TRDat">{{cite web|url=https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/66212|title=Turkey Fact Sheet|last=UNHCR|date=1 August 2018|website=unhcr.org}}</ref> | |||

| {{collapsed infobox section begin|Other countries}} | |||

| | region29 = {{flag|Zambia}} | |||

| | pop29 = 3,000–4,000 | |||

| | ref29 = {{lower|<ref name="ZBIData">{{cite web|url=https://www.hiiraan.com/news4/2013/Dec/52663/somalis_in_zambia_seek_better_leadership.aspx|title=Somalis in Zambia seek better leadership|website=www.hiiraan.com|language=en-US|access-date=18 October 2018}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.lusakatimes.com/2018/01/10/somali-community-zambia-donate-35-trucks-garbage-collection/|title=Zambia : Somali Community in Zambia donate 35 trucks for garbage collection|date=10 January 2018|work=LusakaTimes.com|access-date=18 October 2018|language=en-GB}}</ref>}} | |||

| | region30 = {{flag|Malaysia}} | |||

| | pop30 = 3,000 | |||

| | ref30 = <ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination|title=Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination|date=February 10, 2014|website=migrationpolicy.org|access-date=April 16, 2024|archive-date=April 14, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414153852/https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | region31 = {{flag|Belgium}} | |||

| | pop31 = 2,627 | |||

| | ref31 = {{lower|<ref name="Jan Hertogen">{{cite news|first=J|last=Hertogen|title=Inwoners van vreemde afkomst in België|url=http://www.npdata.be/BuG/155-Vreemde-afkomst/Vreemde-afkomst.htm}}</ref>}} | |||

| | region32 = {{flag|Eritrea}} | |||

| | pop32 = 2,604 | |||

| | ref32 = {{lower|<ref name="ERDat">{{cite news|url=http://www.unhcr.org/protection/operations/524d829b9/eritrea-fact-sheet.html|title=Eritrea Fact Sheet|last=UNHCR|date=1 August 2018|newspaper=Unhcr}}</ref>}} | |||

| | region33 = {{flag|Pakistan}} | |||

| | pop33 = 2,500 | |||

| | ref33 = {{lower|<ref name="Fakhr">{{cite news|last=Fakhr|first=Alhan|title=Insecure once again|url=http://jang.com.pk/thenews/jul2012-weekly/nos-15-07-2012/dia.htm#6|access-date=10 November 2013|newspaper=Daily Jang|date=15 July 2012}}</ref>}} | |||

| | region34 = {{flag|Ireland}} | |||

| | pop34 = 2,150 | |||

| | ref34 = <ref name="Ireland Census">{{Cite web|url=https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpsr/censusofpopulation2022-summaryresults/migrationanddiversity/|title=Population Census of Ireland 2022 Results-Migration and Diversity|date=30 May 2023 |publisher=Ireland Census Bureau of Statistics|access-date=18 August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | region35 = {{flag|New Zealand}} | |||

| | pop35 = 1,617 | |||

| | ref35 = <ref name="NewZealandCensus">{{cite web|url=http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/ethnic-profiles.aspx?request_value=24790&parent_id=24761&tabname=#24790|title=Ethnic group profiles|work=stats.govt.nz}}</ref> | |||

| | region36 = {{flag|Indonesia}} | |||

| | pop36 = 1,170 | |||

| | ref36 = <ref name="UNHCR">{{Cite web|url=https://www.unhcr.org/id/en/figures-at-a-glance#:~:text=As%20of%20end%202023%2C%20there,registered%20with%20UNHCR%20in%20Indonesia.&text=at%20a%20Glance-,As%20of%20end%202023%2C%20there%20are%20so|title=Refugees and Asylum-seekers in Indonesia by country of Origin 2023|publisher=UNHCR Indonesia|access-date=18 August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| {{collapsed infobox section end}} | |||

| | langs = ]<!-- Do not add Arabic, it is NOT spoken natively by Somalis --> | |||

| | rels = ] <sup>(Sunni)</sup> | |||

| | related = ] • ] • ] • ] • ]<ref name="Joireman">{{cite book|last=Joireman|first=Sandra F.|title=Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development|year=1997|publisher=Universal-Publishers|page=1|isbn=978-1581120004}}</ref> | |||

| | native_name = Soomaalida<br/>𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖<br/> صومالِدَ | |||

| | native_name_lang = so | |||

| | rawimage = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ]|231x231px]] | |||

| The '''Somali people''' ({{langx|so|Soomaalida}}, ]: {{lang|so|𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖}},<!--for historical notation purposes--> ]: {{Script/Arabic| صومالِدَ}}) are a ] ] native to the ]<ref>{{Cite book |date=2010-04-06 |title=Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=978-0-08-087775-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F2SRqDzB50wC |access-date=2023-10-25|language=en-GB}}</ref><ref name=2009factbook>{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/somalia/|title=Somalia|access-date=31 May 2009|date=14 May 2009|work=]|publisher=]}}</ref> who share a common ancestry, culture and history. The ] ] is the shared mother tongue of ethnic Somalis, which is part of the ] branch of the ] language family. They are predominantly ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Somali-people |title=Somali-people | website= Britannica|date=23 September 2023 }}</ref><ref name="Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi">Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, ''Culture and Customs of Somalia'', (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.1</ref> Forming one of the largest ethnic groups on the continent, they cover one of the most expansive landmasses by a single ethnic group in ].<ref>The Collapse of the Somali State: The Impact of the Colonial Legacy by A.M. Issa-Salwe (Page 1)</ref> | |||

| According to most scholars, the ancient ] and its native inhabitants formed part of the ethnogenesis of the Somali people. This ancient historical kingdom is where a great portion of their cultural traditions and ancestry are said to derive from.<ref name="ReferenceA">Egypt: 3000 Years of Civilization Brought to Life By Christine El Mahdy</ref><ref name="ReferenceB">Ancient perspectives on Egypt By Roger Matthews, Cornelia Roemer, University College, London.</ref><ref name="ReferenceC">Africa's legacies of urbanization: unfolding saga of a continent By Stefan Goodwin</ref><ref name="ReferenceD">Civilizations: Culture, Ambition, and the Transformation of Nature By Felipe Armesto Fernandez</ref> Somalis share many historical and cultural traits with other ], especially with ] people, specifically the ] and the ].<ref>Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho by I. M. Lewis</ref> | |||

| '''Somalis''' ({{lang-so|''Soomaali''}}, {{lang-ar|صوماليون}}) are an ] inhabiting the ] (]).<ref name=2009factbook>{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/so.html|title=Somalia|accessdate=2009-05-31|date=2009-05-14|work=]|publisher=]}}</ref> The overwhelming majority of Somalis speak the ], which is part of the ] branch of the ] family. They are predominantly ] ].<ref name="Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi"/> Ethnic Somalis number around 20–21 million and are principally concentrated in ] (around 12 million),<ref name="UNFPA Somali Population Survey 2014">. Somalia.unfpa.org (06 April 2014). Retrieved 06 October 2016.</ref> ] (4.6 million),<ref name=CSA/> ] (2.4 million),<ref name="Kengov"/> and ] (524,000).<ref name=Ethnologue> – Ethnologue.com</ref> Expatriate Somalis are also found in parts of the ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| Ethnic Somalis are principally concentrated in ] (around 17.6 million),<ref name="UNFPA Somali Population Survey 2014">{{cite web |date=2022 |title=Population, total - Somalia |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=SO |access-date= |publisher=World Bank |page=}}</ref> ] (5.7 million),<ref name="somalilandchronicle1">{{cite web|date=March 2021|title=Republic of Somaliland – Country Profile 2021|url=https://somalilandchronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Country-GUIDE-March-2021.pdf}}</ref> ] (4.6 million),<ref name="CSA">{{cite web|title=Table 2.2 Percentage distribution of major ethnic groups: 2007|page=16|url=http://www.csa.gov.et/pdf/Cen2007_firstdraft.pdf|work=Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results|publisher=Population Census Commission|access-date=21 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090325050115/http://www.csa.gov.et/pdf/Cen2007_firstdraft.pdf|archive-date=25 March 2009}}</ref> ] (2.8 million),<ref name =Census2019/> and ] (534,000).<ref name="Ethnologue"> – Ethnologue.com</ref> | |||

| ]s are also found in parts of the ], ], ], ] region, ] and ]. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| {{main|proto-Somali}} | |||

| ], the oldest common ancestor of several ]s, is generally regarded as the source of the ] ''Somali''. The name "Somali" is, in turn, held to be derived from the words ''soo'' and ''maal'', which together mean "go and milk" — a reference to the ubiquitous ] of the Somali people.<ref>I. M. Lewis, ''A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa'', (Oxford University Press : 1963), p.12.</ref> Another plausible ] proposes that the term ''Somali'' is derived from the ] for "wealthy" (''dhawamaal''), again referring to Somali riches in livestock.<ref name="Lewis">{{cite book|last=Lewis|first=I. M.|author2=Said Samatar|title=A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa|publisher=LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster|year=1999|pages=11–13|url=https://www.google.com/books?id=L2vXPfRsf04C| isbn = 3-8258-3084-5}}</ref> | |||

| ], the oldest common ancestor of several ], is generally regarded as the source of the ] ''Somali''. One other theory is that the name is held to be derived from the words ''soo'' and ''maal'', which together mean "go and milk". This interpretation differs depending on region with northern Somalis imply it refers to go and milk in regards to the camel's milk,<ref name=":0">Who Cares about Somalia: Hassan's Ordeal; Reflections on a Nation's Future, By Hassan Ali Jama, page 92</ref> southern Somalis use the transliteration "''sa''' ''maal''" which refers to cow's milk.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Ahmed|first=Ali Jimale|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XpdAzRYruCwC&q=northern+southern+soo+maal+invention&pg=PA85|title=The Invention of Somalia|date=1995|publisher=The Red Sea Press|isbn=978-0-932415-99-8|language=en}}</ref> This is a reference to the ubiquitous ] of the Somali people.<ref>I. M. Lewis, ''A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa'', (Oxford University Press : 1963), p.12.</ref> Another plausible ] proposes that the term ''Somali'' is derived from the ] word for "wealthy" (''zāwamāl''), again referring to Somali riches in livestock.<ref name="Lewis">{{cite book|last=Lewis|first=I. M.|author2=Said Samatar|title=A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa|publisher=LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster|year=1999|pages=11–13|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=L2vXPfRsf04C| isbn = 978-3-8258-3084-7}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Suleiman|first=Anita|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kREOAQAAMAAJ&q=Somali+studies+zu+maal|title=Somali studies: early history|date=1991|publisher=HAAN Associates|isbn=9781874209157|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Alternatively, the ethnonym ''Somali'' is believed to have been derived from the Automoli (Asmach), a group of warriors from ] described by ]. ''Asmach'' is thought to have been their Egyptian name, with ''Automoli'' being a Greek derivative of the Hebrew word ''S’mali'' (meaning "on the left hand side").<ref>{{cite book|title=Journal of the East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society, Issues 24–30|date=1926|publisher=The Society|page=103|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vwccAAAAMAAJ|access-date=17 April 2018}}</ref> | |||

| An ] document from the 9th century CE referred to the northern Somalia coast — which was then part of a broader region in ] known as ], in reference to the area's ] (]) inhabitants<ref name="Laitin">David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, ''Somalia: Nation in Search of a State'', (Westview Press: 1987), p. 5.</ref> — as ''Po-pa-li''.<ref name="Cassanelli">Lee V. Cassanelli, ''The shaping of Somali society: reconstructing the history of a pastoral people, 1600-1900'', (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1982), p.9.</ref><ref name="Singh">Nagendra Kr Singh, ''International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties'', (Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 2002), p.524.</ref> The first clear written reference of the sobriquet ''Somali'', however, dates back to the 15th century. During the wars between the ] based at ] and the ], the Abyssinian ] had one of his court officials compose a ] celebrating a military victory over the ] of Ifat's eponymous troops.<ref>I.M. Lewis, ''A modern history of the Somali: nation and state in the Horn of Africa'', 4, illustrated edition, (James Currey: 2002), p.25.</ref> ''Simur'' was also an ancient ] alias for the Somali people.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Fage|first1=J.D|title=The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3|date=1975|publisher=Cambridge University Press|page=154|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&pg=PA154&dq=simur+harari&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjm8efm7crSAhUn54MKHfK0AewQ6AEIGjAA#v=onepage&q=simur%20harari&f=false|accessdate=10 March 2017}}</ref> | |||

| A ] document from the 9th century CE referred to the northern Somalia coast — which was then part of a broader region in ] known as ], in reference to the area's ] (]) inhabitants<ref name="Laitin">David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, ''Somalia: Nation in Search of a State'', (Westview Press: 1987), p. 5.</ref> — as ''Po-pa-li''.<ref>Lee V. Cassanelli, ''The shaping of Somali society: reconstructing the history of a pastoral people, 1600–1900'', (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1982), p.9.</ref><ref name="Singh">Nagendra Kr Singh, ''International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties'', (Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 2002), p. 524.</ref> | |||

| The first clear written reference of the sobriquet ''Somali'' dates back to the early 15th century CE during the reign of Ethiopian Emperor ] who had one of his court officials compose a ] celebrating a military victory over the ].<ref>I.M. Lewis, ''A modern history of the Somali: nation and state in the Horn of Africa'', 4, illustrated edition, (James Currey: 2002), p.25.</ref> ''Simur'' was also an ancient ] alias for the Somali people.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Fage|first1=J.D|title=The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3|date=1975|publisher=Cambridge University Press|page=154|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GWjxR61xAe0C&q=simur+harari&pg=PA154|access-date=10 March 2017|isbn=9780521209816}}</ref> | |||

| Somalis overwhelmingly prefer the demonym ''Somali'' over the incorrect ''Somalian'' since the former is an endonym, while the latter is an exonym with double suffixes.<ref>Michel, A. D. A. M. "Panorama of Socio-Religious Communities1." Indian Africa: Minorities of Indian-Pakistani Origin in Eastern Africa (2015): 69.</ref> The ] of the term ''Somali'' from a geopolitical sense is '']'' and from an ethnic sense, it is '']''.<ref>Woldu, Demelash. Exploring language uses and policy processes in Karat Town of Konso Woreda, Ethiopia. Diss. University of East Anglia, 2018.</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{History_of Somalia}} | {{History_of Somalia}} | ||

| {{History_of Somaliland}} | |||

| {{Main article|History of Somalia|Maritime history of Somalia}} | |||

| {{Main|History of Somalia|History of Somaliland|Maritime history of Somalia}} | |||

| ] in ], a kingdom led in the 16th century by Imam ] (Ahmed Gurey).]] | |||

| ] in ], a kingdom led in the 16th century by Imam ] (Ahmed Gurey).]] | |||

| Ancient ], which date back 5000 years, have been found in the northern part of Somalia; these depict early life in the territory.<ref name="Dawn"/> The most famous of these is the ], which contains some of the earliest known ] on the ] and features many elaborate pastoralist sketches of animal and human figures. In other places, such as the northern ] region, a depiction of a man on a horse is postulated as being one of the earliest known examples of a mounted huntsman.<ref name="Dawn">{{cite web|url=http://www.dawn.com/2011/04/26/grotto-galleries-show-early-somali-life.html|title=Grotto galleries show early Somali life|author=AFP|publisher=}}</ref> | |||

| The origin of the Somali people which was previously theorized to have been from Southern ] since 1000 BC or from the ] in the eleventh century has now been overturned by newer archeological and linguistic studies which puts the original homeland of the Somali people in ] region, which concludes that the Somalis are the indigenous inhabitants of the ] for the last 7000 years.<ref>{{Cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X1dDDwAAQBAJ&q=Making+Sense+of+Somali+History:+Volume+1 | title=Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1| page= 65|isbn=9781909112797| last1=Abdullahi| first1=Abdurahman| date=2017-09-18| publisher=Adonis and Abbey Publishers}}</ref> | |||

| ] have been found beneath many of the rock paintings, but ]s have so far been unable to decipher this form of ancient writing.<ref>Susan M. Hassig, Zawiah Abdul Latif, ''Somalia'', (Marshall Cavendish: 2007), p.22</ref> During the ], the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here with their respective ] and factories.<ref>pg 105 - A History of African archaeology By Peter Robertshaw</ref> | |||

| Ancient ], which date back 5000 years (estimated), have been found in ] region. These engravings depict early life in the territory.<ref name="Dawn"/> The most famous of these is the ]. It contains some of the earliest known ] on the ] and features many elaborate pastoralist sketches of animal and human figures. In other places, such as the ] region, a depiction of a man on a horse is postulated as being one of the earliest known examples of a mounted huntsman.<ref name="Dawn">{{cite web|url=http://www.dawn.com/2011/04/26/grotto-galleries-show-early-somali-life.html|title=Grotto galleries show early Somali life|author=AFP|date=26 April 2011}}</ref> | |||

| The oldest evidence of burial customs in the ] comes from ] in Somalia dating back to ].<ref>pg 40 - Early Holocene Mortuary Practices and Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations in Southern Somalia, by Steven A. Brandt World Archaeology © 1988</ref> The ] from the ''Jalelo'' ] in northern Somalia are said to be the most important link in evidence of the universality in ] times between the ] and the ].<ref>Prehistoric Implements from Somaliland by H. W. Seton-Karr pg 183</ref> | |||

| ] of ] was an important site in the medieval ].]] | |||

| In ], the ancestors of the Somali people were an important link in the Horn of Africa connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of ], ] and ]s, items which were considered valuable luxuries by the ]ians, ]ns, ] and ]ians.<ref>Phoenicia pg 199</ref><ref>The Aromatherapy Book by Jeanne Rose and John Hulburd pg 94</ref> | |||

| ] have been found beneath many of the rock paintings, but ]s have so far been unable to decipher this form of ancient writing.<ref>Susan M. Hassig, Zawiah Abdul Latif, ''Somalia'', (Marshall Cavendish: 2007), p.22</ref> During the ], the ] and ]n cultures flourished here with their respective ] and factories.<ref>pg 105 – A History of African archaeology By Peter Robertshaw</ref> | |||

| According to most scholars, the ancient ] and its inhabitants formed part of the ] of the Somali people.<ref>Egypt: 3000 Years of Civilization Brought to Life By Christine El Mahdy</ref><ref>Ancient perspectives on Egypt By Roger Matthews, Cornelia Roemer, University College, London.</ref><ref>Africa's legacies of urbanization: unfolding saga of a continent By Stefan Goodwin</ref><ref>Civilizations: Culture, Ambition, and the Transformation of Nature By Felipe Armesto Fernandez</ref> The ancient Puntites were a nation of people that had close relations with ] during the times of ] ] and ] ]. The ], temples and ancient houses of ] littered around Somalia are said to date from this period.<ref name="Man, God and Civilization pg 216">Man, God and Civilization pg 216</ref> | |||

| The oldest evidence of burial customs in the ] comes from ] in Somalia dating back to ].<ref>pg 40 – Early Holocene Mortuary Practices and Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations in Southern Somalia, by Steven A. Brandt World Archaeology © 1988</ref> The ] from the ''Jalelo'' ] in Somalia are said to be the most important link in evidence of the universality in ] times between the ] and the ].<ref>Prehistoric Implements from Somalia by H. W. Seton-Karr pg 183</ref> | |||

| In the ], several ancient city-states, such as ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] near ], which competed with the ], ]ns and ] for the wealthy ]-] trade, also flourished in Somalia.<ref>Oman in history By Peter Vine Page 324</ref> | |||

| In ], the ancestors of the Somali people were an important link in the Horn of Africa connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of ], ] and ]s, items which were considered valuable luxuries by the ]ians, ]ns, ] and ]ians.<ref>Phoenicia pg 199</ref><ref>The Aromatherapy Book by Jeanne Rose and John Hulburd pg 94</ref>]]]According to most scholars, the ancient ] and its native inhabitants formed part of the ] of the Somali people.<ref name="ReferenceA"/><ref name="ReferenceB"/><ref name="ReferenceC"/><ref name="ReferenceD"/> The ancient Puntites were a nation of people that had close relations with ] during the times of ] ] and ] ]. The ], temples and ancient houses of ] littered around Somalia may date from this period.<ref name="Man, God and Civilization pg 216">Man, God and Civilization pg 216</ref> | |||

| ]'s realm in the 14th century.]] | |||

| The ] on the opposite side of Somalia's ] coast meant that Somali merchants, sailors and ]s living in the ] gradually came under the influence of the new religion through their converted ] ] trading partners. With the migration of fleeing Muslim families from the ] to Somalia in the early centuries of ], and the peaceful conversion of the Somali population by ] in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic ], ], ], ] and ], which were part of the Berberi civilization. The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the ''City of Islam'',<ref>Society, security, sovereignty and the state in Somalia - Page 116</ref> and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.<ref>East Africa: Its Peoples and Resources - Page 18</ref> | |||

| In ], the ], who may have been ancestral to the Automoli or ancient Somalis, established a powerful tribal kingdom that ruled large parts of modern ]. They were reputed for their longevity and wealth, and were said to be the "tallest and handsomest of all men".<ref name="Wheeler pg 526"> by James Talboys Wheeler, pg 1xvi, 315, 526</ref> The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the ] ], upon ], sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based on his stature and beauty, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to draw it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.<ref name="Wheeler pg 526"/><ref name="Kitto2">John Kitto, James Taylor, ''The popular cyclopædia of Biblical literature: condensed from the larger work'', (Gould and Lincoln: 1856), p.302.</ref> The Macrobians were a regional power reputed for their advanced architecture and ] wealth, which was so plentiful that they shackled their prisoners in golden chains.<ref name="Kitto2"/> | |||

| The ], led by the ] with its capital at ], ruled over parts of what is now eastern Ethiopia, Djibouti, and northern Somalia. The historian ] records that Ifat was situated near the ] coast, and states its size as 15 days travel by 20 days travel. Its army numbered 15,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers. Al-Umari also credits Ifat with seven "mother cities": Belqulzar, Kuljura, Shimi, ], Adal, Jamme and Laboo.<ref>], ''The Glorious Victories of Ameda Seyon, King of Ethiopia'' (Oxford: University Press, 1965), p. 20.</ref> | |||

| ] of the ].]] | |||

| In the ], several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the ], which excelled in ] and ] building,<ref>Shaping of Somali society Lee Cassanelli pg.92</ref> the ], whose general ] (Ahmed Gurey) was the first ] to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the ],<ref>Futuh Al Habash Shibab ad Din</ref> and the ], whose military dominance forced governors of the ] north of the city of ] to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan ].<ref>Sudan Notes and Records - Page 147</ref> The ], an early ] group of tall stature who inhabited parts of Somalia, Tchertcher and other areas in the Horn, also erected various ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Joussaume|first1=Roger|title=Fouille d'un tumulus à Ganda Hassan Abdi dans les monts du Harar|journal=Annales d'Ethiopie|date=1976|volume=10|pages=25–39|url=http://www.persee.fr/doc/ethio_0066-2127_1976_num_10_1_1157|accessdate=10 March 2017|doi=10.3406/ethio.1976.1157}}</ref> These masons are believed to have been ancestral to the Somalis ("proto-Somali").<ref>{{cite book|last=Braukämper|first=Ulrich|title=Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays|url=http://www.google.com/books?id=HGnyk8Pg9NgC&pg=PA18|year=2002|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|isbn=978-3-8258-5671-7}}</ref> | |||

| Several ancient city-states, such as ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] near ], which competed with the ], ]ns and ] for the wealthy ]-] trade, also flourished in Somalia.<ref>Oman in history By Peter Vine Page 324</ref> | |||

| In the late 19th century, after the ] had ended, European empires sailed with their armies to the Horn of Africa. The imperial clouds wavering over Somalia alarmed the ] leader ], who gathered Somali soldiers from across the Horn of Africa and began one of the longest anti-colonial ] ever. The ] successfully repulsed the ] four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region.<ref>Encyclopedia of African history - Page 1406</ref> As a result of its successes against the British, the Dervish State received support from the ] and ]s. The ] also named Hassan ] of the Somali nation,<ref>I.M. Lewis, ''The modern history of Somaliland: from nation to state'', (Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1965), p. 78</ref> and the ] promised to officially recognize any territories the Dervishes were to acquire.<ref>Thomas P. Ofcansky, Historical dictionary of Ethiopia, (The Scarecrow Press, Inc.: 2004), p.405</ref> After a quarter of a century of holding the British at bay, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920, when Britain for the first time in Africa used ]s to bomb the Dervish capital of ]. As a result of this bombardment, former Dervish territories were turned into a ] of Britain. ] similarly faced the same opposition from Somali ] and armies and did not acquire full control of parts of modern Somalia until the ] in late 1927. This occupation lasted till 1941 and was replaced by a British ]. | |||

| ]'s realm in the 14th century.]] | |||

| ], a prominent Somali anti-imperialist leader and the 26th ] of the ].]] | |||

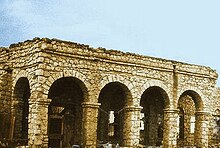

| ] was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of ] fleeing prosecution during the first ] with ] being built before the ]h faced towards ]. The town of ]'s two-] Masjid al-Qiblatayn dates to the 7th century, and is one of the oldest ] in Africa.<ref name="Btgpb">{{cite book |last=Briggs |first=Phillip |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M6NI2FejIuwC |title=Somaliland |publisher=Bradt Travel Guides |year=2012 |isbn=978-1841623719 |page=7}}</ref> | |||

| Following ], Britain retained control of both ] and ] as ]s. In 1945, during the ], the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland, but only under close supervision and on the condition — first proposed by the ] (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL) — that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.<ref name = "Zolberg"/><ref name=Gates1999>Gates, Henry Louis, ''Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience'', (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1749</ref> British Somaliland remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.<ref name=Tripodi1999>Tripodi, Paolo. ''The Colonial Legacy in Somalia'' p. 68 New York, 1999.</ref> | |||

| ], the "Father of the Revolution" initiated by the ].]] | |||

| Consequently the Somalis were some of the earliest non-Arabs that converted to Islam.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Politics of Dress in Somali Culture (African Expressive Cultures)|first=Heather|last=Akou|publisher=Indiana University Press; 1st Paperback Edition|year=2011}}</ref> The peaceful conversion of the Somali population by ] in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic ], ], ], ], ] and ], which were part of the Berberi civilization. The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the ''City of Islam'',<ref>Society, security, sovereignty and the state in Somalia – Page 116</ref> and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.<ref>East Africa: Its Peoples and Resources – Page 18</ref> | |||

| To the extent that Italy held the territory by UN mandate, the trusteeship provisions gave the Somalis the opportunity to gain experience in political education and self-government. These were advantages that British Somaliland, which was to be incorporated into the new Somali state, did not have. Although in the 1950s British colonial officials attempted, through various administrative development efforts, to make up for past neglect, the protectorate stagnated. The disparity between the two territories in economic development and political experience would cause serious difficulties when it came time to integrate the two parts.<ref name=ChapinMetz>Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Somalia: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1992. </ref> | |||

| Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their ] and to the dismay of the Somalis,<ref name="Federal">Federal Research Division, ''Somalia: A Country Study'', (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p.38</ref> the British "returned" the ] (an important Somali grazing area that was presumably 'protected' by British treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the ] to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somali territory to the Ethiopian Emperor ] in exchange for his help against plundering by Somali clans.<ref name=Laitin1977>David D. Laitin, ''Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience'', (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p.73</ref> Britain included the proviso that the Somali nomads would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over them.<ref name="Zolberg">Zolberg, Aristide R., et al., ''Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World'', (Oxford University Press: 1992), p.106</ref> This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to buy back the Somali lands it had turned over.<ref name="Zolberg"/> Britain also granted administration of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited<ref>Francis Vallat, ''First report on succession of states in respect of treaties: International Law Commission twenty-sixth session 6 May-26 July 1974'', (United Nations: 1974), p.20</ref> ] (NFD) to Kenyan nationalists despite an informal ] demonstrating the overwhelming desire of the region's population to join the newly formed Somali Republic.<ref>David D. Laitin, ''Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience'', (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p.75</ref> | |||

| The ], led by the ] with its capital at ], ruled over parts of what is now eastern Ethiopia, Djibouti and Somaliland. The historian ] records that Ifat was situated near the ] coast, and states its size as 15 days travel by 20 days travel. Its army numbered 15,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers. Al-Umari also credits Ifat with seven "mother cities": Belqulzar, Kuljura, Shimi, ], Adal, Jamme and Laboo.<ref>], ''The Glorious Victories of Ameda Seyon, King of Ethiopia'' (Oxford: University Press, 1965), p. 20.</ref> | |||

| {{History_of Djibouti}} | |||

| A ] was held in neighboring ] (then known as ]) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, largely due to a combined yes vote by the sizable ] ethnic group and resident Europeans.<ref name=Barrington2006/> There was also widespread ], with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.<ref name="Kseoah">Kevin Shillington, ''Encyclopedia of African history'', (CRC Press: 2005), p.360.</ref> The majority of those who voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia, as had been proposed by ], Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later.<ref name=Barrington2006>Barrington, Lowell, ''After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States'', (University of Michigan Press: 2006), p.115</ref> Djibouti finally gained its independence from ] in 1977, and ], a Somali who had campaigned for a yes vote in the referendum of 1958, eventually wound up as Djibouti's first president (1977–1991).<ref name=Barrington2006/> | |||

| In the ], several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the ], which excelled in ] and ] building,<ref>Shaping of Somali society Lee Cassanelli pg.92</ref> the ], whose general ] (Ahmed Gurey) was the first ] to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the ],<ref>Futuh Al Habash Shibab ad Din</ref> and the ], whose military dominance forced governors of the ] north of the city of ] to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan ].<ref>Sudan Notes and Records – Page 147</ref> The ], an early group who inhabited parts of Somalia, Tchertcher and other areas in the Horn, also erected various ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Joussaume|first1=Roger|title=Fouille d'un tumulus à Ganda Hassan Abdi dans les monts du Harar|journal=Annales d'Ethiopie|date=1976|volume=10|pages=25–39|doi=10.3406/ethio.1976.1157}}</ref> These masons are believed to have been ancestral to the Somalis ("proto-Somali").<ref>{{cite book|last=Braukämper|first=Ulrich|title=Islamic History and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: Collected Essays|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HGnyk8Pg9NgC&pg=PA18|year=2002|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|isbn=978-3-8258-5671-7}}</ref>] of ] was an important site in the medieval ].]]] was the most important port in the ] between the 18th–19th centuries.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Prichard|first1=J. C.|title= Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind: Ethnography of the African races.|date=1837|publisher= Sherwood, Gilbert & Piper|page=160|language=en}}</ref> For centuries, ] had extensive trade relations with several historic ports in the ]. Additionally, the Somali and Ethiopian interiors were very dependent on ] for trade, where most of the goods for export arrived from. During the 1833 trading season, the port town swelled to over 70,000 people, and upwards of 6,000 camels laden with goods arrived from the interior within a single day. ] was the main marketplace in the entire Somali seaboard for various goods procured from the interior, such as ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite book|title=The Colonial Magazine and Commercial-maritime Journal, Volume 2|date=1840|page=22|language=en}}</ref> Historically, the port of ] was controlled indigenously between the ] Reer Ahmed Nur and Reer Yunis Nuh sub-clans of the ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Lewis|first1=I. M.|title= A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa|date=1988|publisher=Westview Press|page=35|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the ], and the ] (the former Italian Somaliland) followed suit five days later.<ref>Encyclopædia Britannica, ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica'', (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p.835</ref> On 1 July 1960, the two territories united to form the ], albeit within boundaries drawn up by Italy and Britain.<ref name="buluugleey.com">{{cite web|url=http://www.buluugleey.com/warkiidanbe/Governance.htm |title=The dawn of the Somali nation-state in 1960 |publisher=Buluugleey.com |accessdate=2009-02-25}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.strategypage.com/htmw/htwin/articles/20060809.aspx |title=The making of a Somalia state |publisher=Strategypage.com |date=2006-08-09 |accessdate=2009-02-25}}</ref> A government was formed by ] and ] other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments, with ] as President of the Somali National Assembly, ] as the ] of the Somali Republic and ] as ] (later to become President from 1967 to 1969). On 20 July 1961 and through a popular ], the people of Somalia ratified a new ], which was first drafted in 1960.<ref>Greystone Press Staff, ''The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East'', (Greystone Press: 1967), p.338</ref> In 1967, ] became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke. Egal would later become the President of the autonomous ] region in northwestern Somalia. | |||

| ] | |||

| According to a trade journal published in 1856, ] was described as “the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf.”: | |||

| {{cquote|“The only seaports of importance on this coast are Feyla and Berbera; the former is an Arabian colony, dependent of Mocha, but Berbera is independent of any foreign power. It is, without having the name, the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf. From the beginning of November to the end of April, a large fair assembles in Berbera, and caravans of 6,000 camels at a time come from the interior loaded with coffee, (considered superior to Mocha in Bombay), gum, ivory, hides, skins, grain, cattle, and sour milk, the substitute of fermented drinks in these regions; also much cattle is brought there for the Aden market.”<ref>{{cite book|last1=Hunt|first1=Freeman|title=The Merchants' Magazine and Commercial Review, Volume 34|date=1856|page=694|language=en}}</ref>}} | |||

| On 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of ], Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military ] on 21 October 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the ] seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General ], who at the time commanded the army.<ref name="Myswenvwp">Moshe Y. Sachs, ''Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations'', Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p.290.</ref> | |||

| As a tributary of ], which in turn was part of the Ottoman possessions in Western Arabia, the port of ] had seen several men placed as governors over the years. The Ottomans based in Yemen held nominal authority of Zeila when ], who was a successful and ambitious Somali merchant, purchased the rights of the town from the Ottoman governor of Mocha and Hodeida.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Omar|first=Mohamed Osman|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_RAOAQAAMAAJ&q=farmed+out+to|title=The scramble in the Horn of Africa: history of Somalia, 1827–1977|date=2001|publisher=Somali Publications|isbn=9781874209638|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Alongside Barre, the ] (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel ] and Chief of Police ]. The SRC subsequently renamed the country the ],<ref>J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, ''The Cambridge history of Africa'', Volume 8, (Cambridge University Press: 1985), p.478.</ref><ref name="Grolierenc">''The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac'', Volume 25, (Grolier: 1995), p.214.</ref> dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.<ref name="Pjdlfw">Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, ''The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy'', (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p.279.</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>Allee Shurmalkee has since my visit either seized or purchased this town, and hoisted independent colours upon its walls; but as I know little or nothing save the mere fact of its possession by that Soumaulee chief, and as this change occurred whilst I was in Abyssinia, I shall not say anything more upon the subject.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Travels in Southern Abyssinia: Through the Country of Adal to the Kingdom of Shoa|first1=Charles|last1=Johnston|author-link1=Charles Johnston (travel writer)|year=1844|publisher= Madden|page=33}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The revolutionary army established large-scale public works programs and successfully implemented an urban and rural ] campaign, which helped dramatically increase the literacy rate. In addition to a nationalization program of industry and land, the new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the ], eventually joining the ] (AL) in 1974.<ref name="Frankel">Benjamin Frankel, ''The Cold War, 1945–1991: Leaders and other important figures in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, and the Third World'', (Gale Research: 1992), p.306.</ref> That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the ] (OAU), the predecessor of the ] (AU).<ref name="Yang">Oihe Yang, ''Africa South of the Sahara 2001'', 30th Ed., (Taylor and Francis: 2000), p.1025.</ref> | |||

| However, the previous governor was not eager to relinquish his control of Zeila. Hence in 1841, Sharmarke chartered two dhows (ships) along with fifty Somali ] men and two ] to target ] and depose its Arab Governor, Syed Mohammed Al Barr. Sharmarke initially directed his cannons at the city walls which frightened Al Barr's followers and caused them to abandon their posts and succeeded Al Barr as the ruler of Zeila. Sharmarke's governorship had an instant effect on the city, as he maneuvered to monopolize as much of the regional trade as possible, with his sights set as far as ] and the ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Cornwallis Harris |first1=William|title=The Highlands of Æthiopia, Volume 1|date=1844|page=39|publisher=Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Rayne|first=Major.H|title=Sun, Sand and Somals – Leaves from the Note-Book of a District Commissioner|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ubd8CgAAQBAJ&q=sharmarki+chartered+two+dhows+and+returned+with+his+army+to+zeila&pg=PT10|date=1921|publisher=Read Books Ltd|page=75|isbn=9781447485438|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Pan-Somalism== | |||

| {{Main article|Somali nationalism}} | |||

| <!-- Pan-Somalism is ethnic not civic nationalism --> | |||

| ] is centered on the notion that Somalis in ] share a common language, religion, culture and ethnicity, and as such constitute a nation unto themselves. The ideology's earliest manifestations are often traced back to the resistance movement led by ]'s ] at the turn of the 20th century.<ref>Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi. ''Culture and Customs of Somalia''. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc, 2001. p. 24.</ref> In northwestern present-day ], the first Somali nationalist political organization to be formed was the Somali National League (SNL), established in 1935 in the former ] ]. In the country's northeastern, central and southern regions, the similarly-oriented Somali Youth Club (SYC) was founded in 1943 in ], just prior to the ]. The SYC was later renamed the ] (SYL) in 1947. It became the most influential political party in the early years of post-independence Somalia.<ref>Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi. ''Culture and Customs of Somalia''. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc, 2001. p. 25.</ref> | |||

| In 1845, Sharmarke deployed a few matchlock men to wrest control of neighboring Berbera from that town's then feuding Somali local authorities.<ref>Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769–1855. Praeger. p. 18.</ref><ref>First Footsteps in East Africa, by Richard Burton, p. 16-p. 30</ref><ref>Sun, Sand and Somals; leaves from the note-book of a district commissioner in British Somaliland, by Rayne Henry. pp. 15–16</ref> Sharmarke's influence was not limited to the Somali coast as he had allies and influence in the interior of the Somali country, the Danakil coast and even further afield in Abyssinia. Among his allies were the Kings of Shewa. When there was tension between the Amir of Harar ] and Sharmarke, as a result of the Amir arresting one of his agents in ], Sharmarke persuaded the son of ], ruler of ], to imprison on his behalf about 300 citizens of Harar then resident in Shewa, for a length of two years.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Burton. F.|first1=Richard|title= First Footsteps in East Africa |date=1856|page=302|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Notable Pan-Somalists=== | |||

| ] on the left with his brother in-law Duale Idres. Aden, 1892.]] | |||

| ], one of several prominent pan-Somalists that emerged from the ]'s leadership ranks.]] | |||

| *] (7 April 1856 – 21 December 1920) – Somali nationalist and religious leader that established the ] during the ]. | |||

| *] – 26th Sultan of the ] (1897–1960). | |||

| *] – Early 20th century Somali female ] of the Dervish State that frequently joined battles against the imperial powers during the Scramble for Africa. | |||

| *] (d.1948) – Early 20th century Somali female nationalist whose sacrifice became a symbol for Pan-Somalism. | |||

| *] (b. 1905–1945) – Somali nationalist and religious leader. | |||

| *] (b. 1922–1988) – ]. | |||

| *] (7 January 1960 – 10 June 1967) – ]. | |||

| *] (10 June 1967 – 15 October 1969) – Second President of Somalia. | |||

| *] (b. 1919 – 2 January 1995) – Third President of Somalia. | |||

| *] – Somali National Army General, former Head of Somali Police, and commander in the ]. | |||

| *] (1925–1965) – Prominent Somali General considered the Father of the ]. | |||

| *] – active Pan-Somalist that came close to uniting Djibouti with ] in the 1970s. | |||

| *] – ] in the ] and a revolutionary. | |||

| *] (b. 1905–1975) – Somali businessman actively supporting Pan-Somalist aspirations in the 1950s. | |||

| *] – Former Prime Minister of Somalia (1964–1967) and ] leader. | |||

| *], speaker of parliament, from 1965 to 1969 and interim President of Somalia before the coup d'état in 1969. | |||

| *] – General in the Somali National Army; established the National Academy for Strategy. | |||

| *] – ] and politician; first Somali Air Force pilot, the father of Somali Air Force and a prominent member of the Supreme Revolutionary Council. | |||

| *] – Former Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Finance of Somalia. | |||

| *] – First President of the ] and prominent Somali Youth League member. | |||

| *] – Prominent Somali Youth League member and parliamentarian. | |||

| *] – President of Somalia, Colonel in Somali National Army, and commander during WSLF campaign. | |||

| *]h – Pan-Somalist that has written many works on Somali nationalism. | |||

| In the late 19th century, after the ] had ended, the ] reached the Horn of Africa. Increasing foreign influence in the region culminated in the creation of the first ''Darawiish,'' an armed resistance movement calling for the independence from the European powers.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Abdi |first1=Abdulqadir |title=Divine Madness |date=1993 |publisher=Zed Books |page=101 |quote=to the Dervish cause, such as the Ali Gheri, the Mullah's maternal kinsmen and his first converts. In fact, Swayne had instructions to fine the Ali Gheri 1000 camels for possible use in the upcoming campaign}}</ref><ref name="AngusHamilton">*{{cite book |last1=Bartram |first1=R |title=The annihilation of Colonel Plunkett's force |date=1903 |publisher=The Marion Star |url=https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/296280296/ |quote=By his marriage he extended his influence from Abyssinia, on the west, to the borders of Italian Somaliland, on the east. The '''Ali Gheri were his first''' followers.}}<br>*{{cite book |last1=Hamilton |first1=Angus |title=Field Force |publisher= ] |date=1911 |page=50 |url=https://archive.org/stream/dli.ministry.06400/209.94.A.61_djvu.txt |quote=it appeared for the nonce as if he were content with the homage paid to his learnings and devotional sincerity by the Ogaden and Dolbahanta tribes. The '''Ali Gheri were his first followers'''}}<br>*{{cite book |last1=Leys |first1=Thomson |title=The British Sphere |publisher=] |date=1903 |page=5 |url=https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/imageserver/newspapers/P29pZD1BUzE5MDMwNDI0LjEuNSZnZXRwZGY9dHJ1ZQ== |quote='''Ali Gheri were his first''' followers, while these were presently joined by two sections of the Ogaden}}</ref> The ] had their leaders, ], ] and ], who sought a state in the Nugaal<ref name="dervishletter">{{cite book |last1=Samatar |first1=Said |title=In the Shadow of Conquest |date=1992 |publisher=] |page=68 |quote=this letter comes from ... the Dervishes to General Swayne ... They also informed us that you said you would leave the country, I mean the country of the Nugaal and Buuhoodle and its neighborhoods. This news made us extremely joyous.}}</ref> and began one of the longest African conflicts in modern history.<ref>Foreign Department-External-B, August 1899, N. 33-234, NAI, New Delhi, Inclosure 2 in No. 1. And inclosure 3 in No. 1.</ref><ref>F.O.78/5031, Sayyid Mohamad To The Aidagalla, Enclosed Sadler To Salisbury. 69, 20 August 1899</ref> | |||

| ==Religion== | |||

| {{Main article|Islam in Somalia}} | |||

| The ] in Somalia is as old as the religion itself. The early persecuted ]s fled to various places in the region, including the city of ] in modern-day northern Somalia, so as to seek protection from the ]. Somalis were among the first populations on the continent to embrace ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+so0014) |title=A Country Study: Somalia from The Library of Congress |publisher=Lcweb2.loc.gov |accessdate=2011-04-27}}</ref> With very few exceptions, Somalis are entirely Muslims, the majority belonging to the ] branch of Islam and the ] school of ].<ref></ref><ref name="Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi">Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, ''Culture and Customs of Somalia'', (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.1</ref> | |||

| The news of the incident that sparked the 21 year long ], according to the consul-general ], was spread or as he claimed was concocted by Sultan Nur of the ]. The incident in question was that of a group of Somali children who were converted to Christianity and adopted by the French Catholic Mission at ] in 1899. Whether Sultan Nur experienced the incident first hand or whether he was told of it is not clear but what is known is that he propagated the incident in June 1899, precipitating the religious rebellion of the Dervishes.<ref>F.O.78/5031, Sayyid Mohamad To The Aidagalla, Enclosed Sadler To Salisbury. 69, 20 August 1899.</ref> | |||

| ]ed coral stone city of ] is an ancient ] center in ].]] | |||

| ] (also known as ''dugsi'') remain the basic system of traditional religious instruction in Somalia. They provide Islamic education for children, thereby filling a clear religious and social role in the country. Known as the most stable local, non-formal system of education providing basic religious and moral instruction, their strength rests on community support and their use of locally made and widely available teaching materials. The Qur'anic system, which teaches the greatest number of students relative to other educational sub-sectors, is oftentimes the only system accessible to Somalis in nomadic as compared to urban areas. A study from 1993 found, among other things, that "unlike in primary schools where gender disparity is enormous, around 40 per cent of Qur'anic school pupils are girls; but the teaching staff have minimum or no qualification necessary to ensure intellectual development of children." To address these concerns, the Somali government on its own part subsequently established the Ministry of Endowment and Islamic Affairs, under which Qur'anic education is now regulated.<ref></ref> | |||

| The ] successfully stymied ] four times and forced them to retreat to the coastal region.<ref>Encyclopedia of African history – Page 1406</ref> As a result of its successes against the British, the Dervish movement received support from the ] and ]. The ] also named Hassan ] of the Somali nation,<ref>I.M. Lewis, ''The modern history of Somalia: from nation to state'', (Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1965), p. 78</ref> and the ] promised to officially recognise any territories the Dervishes were to acquire.<ref>Thomas P. Ofcansky, Historical dictionary of Ethiopia, (The Scarecrow Press, Inc.: 2004), p.405</ref> | |||

| In the Somali diaspora, multiple Islamic fundraising events are held every year in cities like ], ], ] and ], where Somali ] and ]s give lectures and answer questions from the audience. The purpose of these events is usually to raise money for new schools or universities in Somalia, to help Somalis that have suffered as a consequence of floods and/or droughts, or to gather funds for the creation of new mosques like the Abuubakar-As-Saddique Mosque, which is currently undergoing construction in the ]. | |||

| After a quarter of a century of military successes against the British, the Dervishes were finally defeated by Britain in 1920 in part due to the successful deployment of the newly-formed ] by the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Irons |first=Roy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_8YVBAAAQBAJ |title=Churchill and the Mad Mullah of Somaliland: Betrayal and Redemption 1899–1921 |date=2013-11-04 |publisher=Pen and Sword |isbn=978-1-4738-3155-1 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In addition, the Somali community has produced numerous important Muslim figures over the centuries, many of whom have significantly shaped the course of Islamic learning and practice in the ], the ] and well ]. | |||

| ], 2nd Sultan of the ].]] | |||

| ] was founded in the early-1700s and rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) ].<ref name="Metz">], ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10.</ref> His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.<ref name="HOA">''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1–4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.</ref><ref name="WSP">''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.</ref> | |||

| The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly dismantled in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor ] and his ambitious cousin, ] who founded the ] in 1878. Initially Kenadid wanted to seize control of the neighbouring Sultanate. However, he was unsuccessful in this endeavour, and was eventually forced into exile in ].<ref> | |||

| ===Important Islamic figures=== | |||

| African Studies Center, Northeast African studies, Volumes 11–12, (Michigan State University Press: 1989), p. 32.</ref> Both sultanates maintained written records of their activities, which still exist.<ref name="Ssarif">{{cite book|title=Sub-Saharan Africa Report, Issues 57–67|year=1986|publisher=Foreign Broadcast Information Service|page=34|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8FlEAQAAIAAJ}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- ], patron saint of ].]] --> | |||

| ], a prominent ] of British Somaliland of the delegation sent from ] Protectorate to the British government in London to appeal for the return of ], a territory ceded by the British to ] in 1954.]] | |||

| ] | |||