| Revision as of 21:11, 22 February 2019 editShnevorSomeone (talk | contribs)159 edits →Background: Added content on Nayan KhanTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:28, 7 January 2025 edit undoTheLonelyPather (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers9,774 edits →Influence of Catholic Christianity: update info on the monastery | ||

| (26 intermediate revisions by 20 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{for|Christianity in the modern era|Christianity in Mongolia}} | {{for|Christianity in the modern era|Christianity in Mongolia}} | ||

| ], grandson of ] and founder of the ], seated with his ] queen ] of the ]]] | ], grandson of ] and founder of the ], seated with his ] queen ] of the ]]] | ||

| In modern times the Mongols are primarily ], but in previous eras, especially during the time of the Mongol empire (13th–14th centuries), they were primarily shamanist, and had a substantial minority of Christians, many of whom were in positions of considerable power.<ref>], ''Religions of the Silk Road'', Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010 {{ISBN|978-0-230-62125-1}}</ref><ref> |

In modern times the Mongols are primarily ], but in previous eras, especially during the time of the Mongol empire (13th–14th centuries), they were primarily shamanist, and had a substantial minority of Christians, many of whom were in positions of considerable power.<ref>], ''Religions of the Silk Road'', Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010 {{ISBN|978-0-230-62125-1}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://mcel.pacificu.edu/easpac/2003/may.php3 |title=E-Aspac<!-- Bot generated title --> |access-date=2007-09-08 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061107101245/http://mcel.pacificu.edu/easpac/2003/may.php3 |archive-date=2006-11-07 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Overall, Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions, and typically sponsored several at the same time. Many Mongols had been proselytized by the ] (sometimes called "Nestorian") since about the seventh century,<ref>Weatherford, p. 28</ref> and some tribes' primary religion was Christian. In the time of ], his sons took Christian wives of the ], and under the rule of Genghis Khan's grandson, ], the primary religious influence was Christian. | ||

| The practice of Nestorian Christianity was somewhat different from that practiced in the West, and Europeans tended to regard Nestorianism as heretical for its beliefs about the nature of ]. However, the Europeans also had legends about a figure known as ], a great Christian leader in the East who would come to help with the ]. One version of the legend connected the identity of Prester John with a Christian Mongol leader, ], leader of the Keraites. | The practice of Nestorian Christianity was somewhat different from that practiced in the West, and Europeans tended to regard ] as heretical for its beliefs about the nature of ]. However, the Europeans also had legends about a figure known as ], a great Christian leader in the East who would come to help with the ]. One version of the legend connected the identity of Prester John with a Christian Mongol leader, ], leader of the Keraites. | ||

| Some Mongolians rejected the church structure and what was orthodox for the time, and borrowed elements from other religions and merged beliefs from several ] together.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/46661540 |title=World Religions: Eastern Traditions |publisher=] |others=Edited by Willard Gurdon Oxtoby |year=2002 |isbn=0-19-541521-3 |edition=2nd |location=Don Mills, Ontario |pages=434 |oclc=46661540}}</ref> Some even identified ] with ].<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ⚫ | When the Mongols conquered northern China, establishing the ] (1271–1368), the Church of the East was reintroduced to China after a gap of centuries. As the Mongols further expanded, the Christian sympathies of the court, primarily through the influential wives of the khans, led to changes in military strategy. During the Mongols' ], many of the citizens of the city were massacred, but Christians were spared. |

||

| ⚫ | When the Mongols conquered northern China, establishing the ] (1271–1368), the Church of the East was reintroduced to China after a gap of centuries. As the Mongols further expanded, the Christian sympathies of the court, primarily through the influential wives of the khans, led to changes in military strategy. During the Mongols' ], many of the citizens of the city were massacred, but ] were spared. As the Mongols further encroached upon ], there were some attempts at forming a ] with the Christians of Europe against the Muslims. | ||

| ⚫ | Mongol contacts with the West also led to many missionaries, primarily ] and ], traveling eastward in attempts to convert the Mongols to |

||

| ⚫ | Mongol contacts with the West also led to many missionaries, primarily ] and ], traveling eastward in attempts to convert the Mongols to ]. | ||

| == Background == | == Background == | ||

| Line 13: | Line 16: | ||

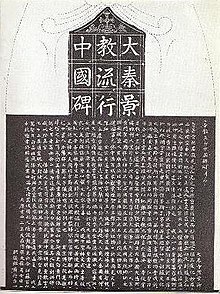

| The Mongols had been ] since about the seventh century.<ref>"The Silk Road", ], p.118 "] was shocked to discover that there were, indeed, Christians at the Mongol court, but that they were schismatic Nestorians (...) Nestorians had long been active along the Silk Road. Their existence in Tang China is testified by the "]", a stela still to be seen in the forest of Stelae in Xi'an"</ref><ref>Foltz "Religions of the Silk Road", p.90-150</ref><ref>For extensive detail and the testimony of Rabban Bar Sauma, see "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. </ref> Many Mongol tribes, such as the Keraites,<ref>"Early in the eleventh century their ruler had been converted to Nestorian Christianity, together with most of his subjects; and the conversion brought the Keraites into touch with the Uighur Turks, amongst whom were many Nestorians", Runciman, p.238</ref> the ], the ], the ],<ref>For these four tribes: Roux, p.39-40</ref> and to a large extent the ] (who practiced it side-by-side with Buddhism),<ref>Grousset, ''Empire'', p. 165</ref> were Nestorian Christian.<ref>"In 1196, Genghis Khan succeeded in the unification under his authority of all the Mongol tribes, some of which had been converted to Nestorian Christianity" "Les Croisades, origines et conséquences", p.74</ref> | The Mongols had been ] since about the seventh century.<ref>"The Silk Road", ], p.118 "] was shocked to discover that there were, indeed, Christians at the Mongol court, but that they were schismatic Nestorians (...) Nestorians had long been active along the Silk Road. Their existence in Tang China is testified by the "]", a stela still to be seen in the forest of Stelae in Xi'an"</ref><ref>Foltz "Religions of the Silk Road", p.90-150</ref><ref>For extensive detail and the testimony of Rabban Bar Sauma, see "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. </ref> Many Mongol tribes, such as the Keraites,<ref>"Early in the eleventh century their ruler had been converted to Nestorian Christianity, together with most of his subjects; and the conversion brought the Keraites into touch with the Uighur Turks, amongst whom were many Nestorians", Runciman, p.238</ref> the ], the ], the ],<ref>For these four tribes: Roux, p.39-40</ref> and to a large extent the ] (who practiced it side-by-side with Buddhism),<ref>Grousset, ''Empire'', p. 165</ref> were Nestorian Christian.<ref>"In 1196, Genghis Khan succeeded in the unification under his authority of all the Mongol tribes, some of which had been converted to Nestorian Christianity" "Les Croisades, origines et conséquences", p.74</ref> | ||

| ] himself believed in traditional ], but was tolerant of other faiths. When, as the young Temüjin, he swore allegiance with his men at the Baljuna Covenant |

] himself believed in traditional ], but was tolerant of other faiths. When, as the young Temüjin, he swore allegiance with his men at the ] in 1203, there were representatives of nine tribes among the 20 men, including "several Christians, three Muslims, and several Buddhists."<ref>Weatherford, p. 58</ref> | ||

| His sons were married to Christian princesses of the Keraites clan who held considerable influence at his court.<ref name="Runciman-246"/> Under the Great Khan ], Genghis's grandson, the main religious influence was that of the Nestorians.<ref>Under Mongka "The chief religious influence was that of the Nestorian Christians, to whom Mongka showed especial favour in memory of his mother Sorghaqtani, who had always remained loyal to her faith" Runciman, p.296</ref> | His sons were married to Christian princesses of the Keraites clan who held considerable influence at his court.<ref name="Runciman-246"/> Under the Great Khan ], Genghis's grandson, the main religious influence was that of the Nestorians.<ref>Under Mongka "The chief religious influence was that of the Nestorian Christians, to whom Mongka showed especial favour in memory of his mother Sorghaqtani, who had always remained loyal to her faith" Runciman, p.296</ref> | ||

| Line 23: | Line 26: | ||

| * ], an ] Mongol earlier known as Rabban Marcos, became the ] from 1281 to 1317.<ref>Grousset, p.698</ref> | * ], an ] Mongol earlier known as Rabban Marcos, became the ] from 1281 to 1317.<ref>Grousset, p.698</ref> | ||

| * ], a Chinese monk who made a pilgrimage from ] (now ]) and testified to the importance of Christianity among the Mongols during his visit to Rome in 1287. | * ], a Chinese monk who made a pilgrimage from ] (now ]) and testified to the importance of Christianity among the Mongols during his visit to Rome in 1287. | ||

| * ], a Mongol nobleman and uncle of ]. In 1287, after becoming increasingly angry with Kublai for being “too Chinese”, Nayan staged a rebellion. Since he was a nobleman and governor of four Mongol regions, Nayan had a significant army. He also allied with other Mongol governors who were themselves dissatisfied with |

* ], a Mongol nobleman and uncle of ]. In 1287, after becoming increasingly angry with Kublai for being “too Chinese”, Nayan staged a rebellion. Since he was a nobleman and governor of four Mongol regions, Nayan had a significant army. He also allied with other Mongol governors who were themselves dissatisfied with Kublai's rejection of Mongol values, from their perspective. Nayan's battle standard had a cross on it because he was a Christian. Their rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful, and Nayan was quietly executed. | ||

| ==Practice== | ==Practice== | ||

| ], found in ], dated 1312]] | ], found in ], dated 1312]] | ||

| According to popular anthropologist ], because the Mongols had a primarily nomadic culture, their practice of Christianity was different from what might have been recognized by most Western Christians. The Mongols had no churches or monasteries, but claimed a set of beliefs that descended from the ], which relied on wandering monks. Further, their style was based more on practice than belief. The primary interest in Christianity for many, was the story that Jesus had healed the sick and survived death, so the practice of Christianity became interwoven with the care of the sick. Jesus was considered to be a powerful shaman, and another attraction was that the name Jesus sounded like ''Yesu'', the Mongol number "9". It was a sacred number to the Mongols, and was also the name of Genghis Khan's father, ].<ref>Weatherford, p. 135</ref> However, somewhat in contradiction to Weatherford, there is written evidence of a permanent Nestorian church in Karakorum<ref> |

According to popular anthropologist ], because the Mongols had a primarily nomadic culture, their practice of Christianity was different from what might have been recognized by most Western Christians. The Mongols had no churches or monasteries, but claimed a set of beliefs that descended from the ], which relied on wandering monks. Further, their style was based more on practice than belief. The primary interest in Christianity for many, was the story that Jesus had healed the sick and survived death, so the practice of Christianity became interwoven with the care of the sick. Jesus was considered to be a powerful shaman, and another attraction was that the name Jesus sounded like ''Yesu'', the Mongol number "9". It was a sacred number to the Mongols, and was also the name of Genghis Khan's father, ].<ref>Weatherford, p. 135</ref> However, somewhat in contradiction to Weatherford, there is written evidence of a permanent Nestorian church in Karakorum<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/rubruck.html#court_christians|title=William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols|website=depts.washington.edu}}</ref> and archeological evidence for other permanent church buildings in ]<ref name = "halbertsma"></ref> and ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.livescience.com/48433-city-ruled-by-genghis-khan-heirs.html|title = Ancient City Ruled by Genghis Khan's Heirs Revealed| website=] | date=24 October 2014 }}</ref> The use of non-permanent (yurt) churches is also well-documented.<ref name = "halbertsma"/> | ||

| Again according to Weatherford, the Mongols also adapted the Christian cross to their own belief system, making it sacred because it pointed to the four directions of the world. They had varied readings of the Scriptures, especially feeling an affinity to the wandering ]. Christianity also allowed the eating of meat (different from the vegetarianism of the Buddhists). And of particular interest to the hard-drinking Mongols, they enjoyed that the consuming of alcohol was a required part of church services.<ref>Weatherford, p. 29. "Jesus was considered an important and powerful shaman, and the cross was sacred as the symbol of the four directions of the world. As a pastoral people, the steppe tribes felt very comfortable with the pastoral customs and beliefs of the ancient Hebrew tribes as illustrated in the Bible. Perhaps above all, the Christians ate meat, unlike the vegetarian Buddhists; and in contrast to the abstemious Muslims, the Christians not only enjoyed drinking alcohol, but they even prescribed it as a mandatory part of their worship service."</ref> | Again according to Weatherford, the Mongols also adapted the Christian cross to their own belief system, making it sacred because it pointed to the four directions of the world. They had varied readings of the Scriptures, especially feeling an affinity to the wandering ]. Christianity also allowed the eating of meat (different from the vegetarianism of the Buddhists). And of particular interest to the hard-drinking Mongols, they enjoyed that the consuming of alcohol was a required part of church services.<ref>Weatherford, p. 29. "Jesus was considered an important and powerful shaman, and the cross was sacred as the symbol of the four directions of the world. As a pastoral people, the steppe tribes felt very comfortable with the pastoral customs and beliefs of the ancient Hebrew tribes as illustrated in the Bible. Perhaps above all, the Christians ate meat, unlike the vegetarian Buddhists; and in contrast to the abstemious Muslims, the Christians not only enjoyed drinking alcohol, but they even prescribed it as a mandatory part of their worship service."</ref> | ||

| Line 38: | Line 41: | ||

| ]" ("King and Khan")<ref>Roux, p.107</ref> ] as "Prester John" in "Le Livre des Merveilles", 15th century.]] | ]" ("King and Khan")<ref>Roux, p.107</ref> ] as "Prester John" in "Le Livre des Merveilles", 15th century.]] | ||

| An account of the conversion of the Keraite is given by the 13th century ] historian, Gregory ], who documented a 1009 letter by bishop ] to the Patriarch ] which announced the conversion of the Keraits to Christianity.<ref>Roux, ''L'Asie Centrale'', p.241</ref> According to Hebraeus, in the early 11th century, a Keraite king lost his way while hunting in the high mountains. When he had abandoned all hope, a saint appeared in a vision and said, "If you will believe in Christ, I will lead you lest you perish." The king returned home safely, and when he later met Christian merchants, he remembered the vision and asked them about their faith. At their suggestion, he sent a message to the Metropolitan of ] for priests and deacons to baptize him and his tribe. As a result of the mission that followed, the king and 20,000 of his people were baptized.<ref name="grousset" /><ref>Moffett, ''A History of Christianity in Asia'' pp. 400-401.</ref> | An account of the conversion of the Keraite is given by the 13th century ] historian, Gregory ], who documented a 1009 letter by bishop ] to the Patriarch ] which announced the conversion of the Keraits to Christianity.<ref>Roux, ''L'Asie Centrale'', p.241</ref> According to Hebraeus, in the early 11th century, a Keraite king lost his way while hunting in the high mountains. When he had abandoned all hope, a saint, ], appeared in a vision and said, "If you will believe in Christ, I will lead you lest you perish." The king returned home safely, and when he later met Christian merchants, he remembered the vision and asked them about their faith. At their suggestion, he sent a message to the Metropolitan of ] for priests and deacons to baptize him and his tribe. As a result of the mission that followed, the king and 20,000 of his people were baptized.<ref name="grousset" /><ref>Moffett, ''A History of Christianity in Asia'' pp. 400-401.</ref> | ||

| The legend of ] was also connected with the Nestorian rulers of the Keraite. Though the identity of Prester John was linked with individuals from other areas as well, such as India or Ethiopia, in some versions of the legend, Prester John was explicitly identified with the Christian Mongol ]. | The legend of ] was also connected with the Nestorian rulers of the Keraite. Though the identity of Prester John was linked with individuals from other areas as well, such as India or Ethiopia, in some versions of the legend, Prester John was explicitly identified with the Christian Mongol ]. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 48: | ||

| {{main|Franco-Mongol alliance}} | {{main|Franco-Mongol alliance}} | ||

| ] and his wife ] in a Syriac Bible]] | ] and his wife ] in a Syriac Bible]] | ||

| Some military collaboration with Christian powers took place in |

Some military collaboration with Christian powers took place in 1259–1260. ] of ] and his son-in-law ] of Antioch had submitted to the Mongols, and, as did other vassal states, provided troops in the Mongols' expansion. The founder and leader of the Ilkhanate in 1260, ], was generally favourable to Christianity: his mother was Christian, his principal wife ] was a prominent Christian leader in the Ilkhanate, and at least one of his key generals, ], was also Christian.<ref name=grousset>Grousset, p. 581.</ref> A later descendant of Hulagu, the Ilkhan ], sent the Nestorian monk ] as an ambassador to Western courts to offer an alliance between the Mongols and the Europeans. While there, Bar Sauma explained the situation of the Nestorian faith to the European monarchs: | ||

| {{quote|"Know ye, O our Fathers, that many of our Fathers (Nestorian missionaries since the 7th century) have gone into the countries of the Mongols, and Turks, and Chinese and have taught them the Gospel, and at the present time there are many Mongols who are Christians. For many of the sons of the Mongol kings and queens have been baptized and confess Christ. And they have established churches in their military camps, and they pay honour to the Christians, and there are among them many who are believers."|Travels of Rabban Bar Sauma <ref> |

{{quote|"Know ye, O our Fathers, that many of our Fathers (Nestorian missionaries since the 7th century) have gone into the countries of the Mongols, and Turks, and Chinese and have taught them the Gospel, and at the present time there are many Mongols who are Christians. For many of the sons of the Mongol kings and queens have been baptized and confess Christ. And they have established churches in their military camps, and they pay honour to the Christians, and there are among them many who are believers."|Travels of Rabban Bar Sauma <ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.aina.org/books/mokk/mokk.htm|title=The Monks of Kublai Khan|website=www.aina.org}}</ref>}} | ||

| Upon his return, Bar Sauma wrote an elaborate account of his journey, which is of keen interest to modern historians, as it was the first account of Europe as seen through Eastern eyes. | Upon his return, Bar Sauma wrote an elaborate account of his journey, which is of keen interest to modern historians, as it was the first account of Europe as seen through Eastern eyes. | ||

| Line 53: | Line 56: | ||

| ==Influence of Catholic Christianity== | ==Influence of Catholic Christianity== | ||

| {{main|Christianity in Asia}} | {{main|Christianity in Asia}} | ||

| ] ] from |

] ] from ] in ] (then called Dadu, or ]), ]]] | ||

| The type of Christianity which the Mongols practiced was an Eastern ] form, which had an independent hierarchy from Western doctrine since the ] in the 5th century. Over the centuries, much of Europe had become unaware that there were any Christians in central Asia and beyond, except for vague legends of a ], a Christian king from the East who many hoped would come to help with the ] and the fight for the Holy Land. Even after contacts were re-established, there were still Western missionaries who proceeded eastward, to try and convert the Mongols to Roman Catholicism, away from what was regarded as ] Nestorianism. Some contacts were with the capital of the Mongols, first in ] and then ] (Beijing) in Mongol-conquered China. A larger number of contacts were with the closest of the Mongol states, the ] in what today is Iran, Iraq, and Syria. | The type of Christianity which the Mongols practiced was an Eastern ] form, which had an independent hierarchy from Western doctrine since the ] in the 5th century. Over the centuries, much of Europe had become unaware that there were any Christians in central Asia and beyond, except for vague legends of a ], a Christian king from the East who many hoped would come to help with the ] and the fight for the Holy Land. Even after contacts were re-established, there were still Western missionaries who proceeded eastward, to try and convert the Mongols to Roman Catholicism, away from what was regarded as ] Nestorianism. Some contacts were with the capital of the Mongols, first in ] and then ] (Beijing) in Mongol-conquered China. A larger number of contacts were with the closest of the Mongol states, the ] in what today is Iran, Iraq, and Syria. | ||

| As early as 1223, Franciscan missionaries had been traveling eastward to visit the prince of Damascus and the Caliph of Baghdad.<ref name=roux-95>Roux, ''Les explorateurs'', pp. 95–97</ref> In 1240, nine ] led by Guichard of Cremone are known to have arrived in ], the capital of Christian Georgia, by the orders of ]. Georgia submitted to the advancing Mongols in 1243, so as the missionaries lived for five years in the Georgian realm, much of it was in contact or in close proximity with the Mongols.<ref name=roux-95/> In 1245, ] sent a series of four missions to the Mongols. The first was led by the Dominican ], who had already been sent to Constantinople once by ] to acquire the ] from ].<ref name=roux-95/> His travels are known by the reports of ]. Three other missions were sent between March and April 1245, led respectively by the Dominican ] (accompanied by ], who later wrote the account of the mission in ''Historia Tartarorum''),<ref name=roux-95/> the Franciscan ], and another Franciscan, ]. | As early as 1223, Franciscan missionaries had been traveling eastward to visit the prince of Damascus and the Caliph of Baghdad.<ref name=roux-95>Roux, ''Les explorateurs'', pp. 95–97</ref> In 1240, nine ] led by Guichard of Cremone are known to have arrived in ], the capital of Christian Georgia, by the orders of ]. Georgia submitted to the advancing Mongols in 1243, so as the missionaries lived for five years in the Georgian realm, much of it was in contact or in close proximity with the Mongols.<ref name=roux-95/> In 1245, ] sent a series of four missions to the Mongols. The first was led by the Dominican ], who had already been sent to Constantinople once by ] to acquire the ] from ].<ref name=roux-95/> His travels are known by the reports of ]. Three other missions were sent between March and April 1245, led respectively by the Dominican ] (accompanied by ], who later wrote the account of the mission in ''Historia Tartarorum''),<ref name=roux-95/> the Franciscan ], and another Franciscan, ]. | ||

| In 1253, the Franciscan ] traveled to ], the western Mongol capital, and sought permission to serve its people in the name of Christ. He was received courteously, but forbidden to engage in missionary work or remain in the country.{{ref|AFM}} At one point of his stay among the Mongols, William did enter into a famous competition at the Mongol court. The khan encouraged a formal debate between the Christians, Buddhists, and Muslims, to determine which faith was correct, as determined by three judges, one from each faith.<ref>{{cite book|first=Jack |last=Weatherford|title=Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World|page=173}}</ref> When William returned to the West, he wrote a 40-chapter document on the customs and geography of the Mongols. Armenian King ], ] and ] visited Mongolia.<ref name="Rossabi2014">{{cite book|author=Morris Rossabi|title=From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GXejBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA670 |

In 1253, the Franciscan ] traveled to ], the western Mongol capital, and sought permission to serve its people in the name of Christ. He was received courteously, but forbidden to engage in missionary work or remain in the country.{{ref|AFM}} At one point of his stay among the Mongols, William did enter into a famous competition at the Mongol court. The khan encouraged a formal debate between the Christians, Buddhists, and Muslims, to determine which faith was correct, as determined by three judges, one from each faith.<ref>{{cite book|first=Jack |last=Weatherford|title=Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World|page=173}}</ref> When William returned to the West, he wrote a 40-chapter document on the customs and geography of the Mongols. Armenian King ], ] and ] visited Mongolia.<ref name="Rossabi2014">{{cite book|author=Morris Rossabi|title=From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GXejBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA670|date=28 November 2014|publisher=BRILL|isbn=978-90-04-28529-3|pages=670–}}</ref> | ||

| Dominican missionaries to the Ilkhanate included ] and ], who later became the bishop in the Ilkhanate capital of ]. By the year 1300, there were numerous Dominican and Franciscan convents in the Il-Khanate. About ten cities had such institutions, including Maragha, ], ], ], and ]. To help with coordination, the Pope established an archbishop in the new capital of ] in 1318 in the person of Francon de Pérouse, who was assisted by six bishops. His successor in 1330 was Jean de Cor.<ref>Roux, ‘’Histoire de l’Empire Mongol’’, p. 439</ref> | Dominican missionaries to the Ilkhanate included ] and ], who later became the bishop in the Ilkhanate capital of ]. By the year 1300, there were numerous Dominican and Franciscan convents in the Il-Khanate. About ten cities had such institutions, including Maragha, ], ], ], and ]. To help with coordination, the Pope established an archbishop in the new capital of ] in 1318 in the person of Francon de Pérouse, who was assisted by six bishops. His successor in 1330 was Jean de Cor.<ref>Roux, ‘’Histoire de l’Empire Mongol’’, p. 439</ref> | ||

| In 1302, the Nestorian Catholicos ], who as a young man had accompanied the older Rabban Bar Sauma from ] (Beijing), sent a profession of faith to the Pope. He thereby formalized his conversion to Roman Catholicism, though a 1304 letter from him to the pope indicated that his move had been strongly opposed by the local Nestorian clergy.<ref>Luisetto, p.99-100</ref> | In 1302, the Nestorian Catholicos ], who as a young man had accompanied the older Rabban Bar Sauma from ] (Beijing), sent a profession of faith to the Pope. He thereby formalized his conversion to Roman Catholicism, though a 1304 letter from him to the pope indicated that his move had been strongly opposed by the local Nestorian clergy.<ref>Luisetto, p.99-100</ref> | ||

| Mongol-European contacts diminished as Mongol power waned in Persia |

Mongol-European contacts diminished as Mongol power waned in Persia. In 1295, ] (great-grandson of Hulagu) formally adopted Islam when he took the throne of the Ilkhanate in 1295, as did ] along with other ] leaders. | ||

| In his own letters to the Mongol ruler in 1321 and 1322, the Pope still expressed his hope that the Mongol ruler would convert to Christianity. Between 500 |

In his own letters to the Mongol ruler in 1321 and 1322, the Pope still expressed his hope that the Mongol ruler would convert to Christianity. Between 500 and 1000 converts in each city were numbered by Jean of Sultaniye.<ref>Roux, ''Histoire'', p. 440</ref> | ||

| By the 14th century, the Mongols had effectively disappeared as a political power. | By the 14th century, the Mongols had effectively disappeared as a political power. | ||

| Line 74: | Line 77: | ||

| In 1271, the ] brought an invitation from ] to ], imploring him that a hundred teachers of science and religion be sent to reinforce the Christianity already present in his vast empire. This came to naught due to the hostility of influential Nestorians within the Mongol court, who objected to the introduction of the Western (Roman Catholic) form of Christianity to supplant their own Nestorian doctrine. | In 1271, the ] brought an invitation from ] to ], imploring him that a hundred teachers of science and religion be sent to reinforce the Christianity already present in his vast empire. This came to naught due to the hostility of influential Nestorians within the Mongol court, who objected to the introduction of the Western (Roman Catholic) form of Christianity to supplant their own Nestorian doctrine. | ||

| In 1289, ] sent the Franciscan ], who became China's first Roman Catholic missionary. He was significantly successful, translated the ] and ] into the Mongol language, built a central church, and within a few years (by 1305) could report six thousand baptized converts. But the work was not easy. He was often opposed by the Nestorians, whose style of Eastern Christianity was different from John's Western version. But the Franciscan mission continued to grow, other priests joined him and centers were established in the coastal provinces of ] (]), ] (]) and ] (]). Following the death of Monte Corvino, an embassy to the French ] in ] was sent by ], the last Mongol emperor in the ] of China, in 1336.<ref>Jackson, p. 314</ref> The Mongol ruler requested a new spiritual guide to replace Monte Corvino, so in 1338, a total of 50 ecclesiastics were sent by the Pope to ], among them ]. | In 1289, ] sent the Franciscan ], who became China's first Roman Catholic missionary. He was significantly successful, translated the ] and ] into the Mongol language, built a central church, and within a few years (by 1305) could report six thousand baptized converts. But the work was not easy. He was often opposed by the Nestorians, whose style of Eastern Christianity was different from John's Western version. But the Franciscan mission continued to grow, other priests joined him and centers were established in the coastal provinces of ] (]), ] (]) and ] (]). Following the death of Monte Corvino, an embassy to the French ] in ] was sent by ], the last Mongol emperor in the ] of China, in 1336.<ref>Jackson, p. 314</ref> The Mongol ruler requested a new spiritual guide to replace Monte Corvino, so in 1338, a total of 50 ecclesiastics were sent by the Pope to ], among them ]. | ||

| Two massive catastrophes hastened the extinction of this second wave of missionaries to China. |

Two massive catastrophes hastened the extinction of this second wave of missionaries to China. First, the ] during the latter half of the fourteenth century in Europe so depleted Franciscan houses that they were unable to sustain the mission to China. Second, the Mongol-created ] in China began to decline. The native Chinese rose up and drove out the Mongols, thereby launching the ] in 1368. By 1369, all Christians, whether Roman Catholic or Syro-Oriental, were expelled. With the end of Mongol rule in the 14th century, Christianity almost disappeared in mainland Asia, with three of the four principal Mongol khanates embracing Islam.<ref>The Encyclopedia Americana, By Grolier Incorporated, p. 680</ref> | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 84: | Line 87: | ||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist|2}} | ||

| ==References and further reading== | ==References and further reading== | ||

| *{{cite book|title=Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291|author= |

*{{cite book|title=Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291|author=Grousset, René|author-link=René Grousset|publisher=Editions Perrin|year=2006 |isbn=978-2-262-02569-4}} | ||

| *{{cite encyclopedia |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica |url=http://www.encyclopediairanica.com/articles/v10f2/v10f216a.html |title=Franco-Persian relations |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927032850/http://www.encyclopediairanica.com/articles/v10f2/v10f216a.html |archive-date=2007-09-27}} | *{{cite encyclopedia |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica |url=http://www.encyclopediairanica.com/articles/v10f2/v10f216a.html |title=Franco-Persian relations |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927032850/http://www.encyclopediairanica.com/articles/v10f2/v10f216a.html |archive-date=2007-09-27}} | ||

| *{{cite book|title=The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China|author=Sir E. A. Wallis Budge|url=http://www.aina.org/books/mokk/mokk.htm}} | *{{cite book|title=The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China|author=Sir E. A. Wallis Budge|url=http://www.aina.org/books/mokk/mokk.htm}} | ||

| *{{cite web|title=The history and Life of Rabban Bar Sauma, translated from the Syriac by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge|url=http://www.nestorian.org/history_of_rabban_bar_sawma_1.html| |

*{{cite web|title=The history and Life of Rabban Bar Sauma, translated from the Syriac by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge|url=http://www.nestorian.org/history_of_rabban_bar_sawma_1.html|url-status=dead|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928031354/http://www.nestorian.org/history_of_rabban_bar_sawma_1.html|archivedate=2007-09-28}} | ||

| *{{cite book|author= |

*{{cite book|author=Foltz, Richard|author-link=Richard Foltz|year=2010|title=Religions of the Silk Road : premodern patterns of globalization|location=New York|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|isbn=978-0-230-62125-1}} | ||

| *{{cite book|author=Roux, Jean-Paul|title=Histoire de l'Empire Mongol|publisher=Fayard|language=French|isbn=2-213-03164-9}} | *{{cite book|author=Roux, Jean-Paul|title=Histoire de l'Empire Mongol|year=1993|publisher=Fayard|language=French|isbn=2-213-03164-9}} | ||

| * {{cite book|author=Weatherford, Jack|year=2004|title=Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World|publisher=Three Rivers Press|isbn=0-609-80964-4}} | * {{cite book|author=Weatherford, Jack|year=2004|title=Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World|publisher=Three Rivers Press|isbn=0-609-80964-4}} | ||

| * {{cite book|author=Luisetto, Frédéric|title=Arméniens et autres Chrétiens d'Orient sous la domination Mongole|language=French|publisher=Geuthner|year=2007|isbn=978-2-7053-3791-9}} | * {{cite book|author=Luisetto, Frédéric|title=Arméniens et autres Chrétiens d'Orient sous la domination Mongole|language=French|publisher=Geuthner|year=2007|isbn=978-2-7053-3791-9}} | ||

| * {{cite book|author1=Mahé, Annie|author2= |

* {{cite book|author1=Mahé, Annie|author2=Mahé, Jean-Pierre|author2-link=Mahé, Jean-Pierre|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1ztSswEACAAJ|title=L'Arménie à l'épreuve des siècles|language=French|series=Coll. “]”|volume=464|location=Paris|publisher=Éditions Gallimard|year=2005|isbn=978-2-07-031409-6}} | ||

| * {{cite book|author=Rossabi, Morris|title=Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West|year=1992|isbn=4-7700-1650-6|publisher=]}} | * {{cite book|author=Rossabi, Morris|title=Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West|year=1992|isbn=4-7700-1650-6|publisher=]|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/voyagerfromxanad00ross}} | ||

| {{Eastern Christianity footer}} | |||

| {{Mongol Empire}} | {{Mongol Empire}} | ||

Latest revision as of 04:28, 7 January 2025

For Christianity in the modern era, see Christianity in Mongolia.

In modern times the Mongols are primarily Tibetan Buddhists, but in previous eras, especially during the time of the Mongol empire (13th–14th centuries), they were primarily shamanist, and had a substantial minority of Christians, many of whom were in positions of considerable power. Overall, Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions, and typically sponsored several at the same time. Many Mongols had been proselytized by the Church of the East (sometimes called "Nestorian") since about the seventh century, and some tribes' primary religion was Christian. In the time of Genghis Khan, his sons took Christian wives of the Keraites, and under the rule of Genghis Khan's grandson, Möngke Khan, the primary religious influence was Christian.

The practice of Nestorian Christianity was somewhat different from that practiced in the West, and Europeans tended to regard Nestorianism as heretical for its beliefs about the nature of Jesus. However, the Europeans also had legends about a figure known as Prester John, a great Christian leader in the East who would come to help with the Crusades. One version of the legend connected the identity of Prester John with a Christian Mongol leader, Toghrul, leader of the Keraites.

Some Mongolians rejected the church structure and what was orthodox for the time, and borrowed elements from other religions and merged beliefs from several Christian denominations together. Some even identified Adam with the Buddha.

When the Mongols conquered northern China, establishing the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), the Church of the East was reintroduced to China after a gap of centuries. As the Mongols further expanded, the Christian sympathies of the court, primarily through the influential wives of the khans, led to changes in military strategy. During the Mongols' siege of Baghdad (1258), many of the citizens of the city were massacred, but Christians were spared. As the Mongols further encroached upon Palestine, there were some attempts at forming a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Christians of Europe against the Muslims.

Mongol contacts with the West also led to many missionaries, primarily Franciscan and Dominican, traveling eastward in attempts to convert the Mongols to Catholicism.

Background

The Mongols had been proselytised since about the seventh century. Many Mongol tribes, such as the Keraites, the Naimans, the Merkit, the Ongud, and to a large extent the Qara Khitai (who practiced it side-by-side with Buddhism), were Nestorian Christian.

Genghis Khan himself believed in traditional Mongolian shamanism, but was tolerant of other faiths. When, as the young Temüjin, he swore allegiance with his men at the Baljuna Covenant in 1203, there were representatives of nine tribes among the 20 men, including "several Christians, three Muslims, and several Buddhists." His sons were married to Christian princesses of the Keraites clan who held considerable influence at his court. Under the Great Khan Mongke, Genghis's grandson, the main religious influence was that of the Nestorians.

Some of the major Christian figures among the Mongols were:

- Sorghaghtani Beki, daughter-in-law of Genghis Khan by his son Tolui, and mother of Möngke Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulagu Khan and Ariq Böke, who were also married to Christian princesses;

- Doquz Khatun, wife of Hulagu Khan and mother of Abaqa Khan, who for his part married Maria Palaiologina, daughter of the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1265. After the death of Abaqa's mother Doquz, Maria filled her role as a major Christian influence in the Ilkhanate.

- Sartaq Khan, son of Batu Khan, who converted to Christianity during his lifetime;

- Kitbuqa, general of Mongol forces in the Levant, who fought in alliance with Christian vassals.

- Yahballaha III, an Ongud Mongol earlier known as Rabban Marcos, became the Patriarch of the Church of the East from 1281 to 1317.

- Rabban Bar Sauma, a Chinese monk who made a pilgrimage from Khanbaliq (now Beijing) and testified to the importance of Christianity among the Mongols during his visit to Rome in 1287.

- Nayan Khan, a Mongol nobleman and uncle of Kublai Khan. In 1287, after becoming increasingly angry with Kublai for being “too Chinese”, Nayan staged a rebellion. Since he was a nobleman and governor of four Mongol regions, Nayan had a significant army. He also allied with other Mongol governors who were themselves dissatisfied with Kublai's rejection of Mongol values, from their perspective. Nayan's battle standard had a cross on it because he was a Christian. Their rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful, and Nayan was quietly executed.

Practice

According to popular anthropologist Jack Weatherford, because the Mongols had a primarily nomadic culture, their practice of Christianity was different from what might have been recognized by most Western Christians. The Mongols had no churches or monasteries, but claimed a set of beliefs that descended from the Apostle Thomas, which relied on wandering monks. Further, their style was based more on practice than belief. The primary interest in Christianity for many, was the story that Jesus had healed the sick and survived death, so the practice of Christianity became interwoven with the care of the sick. Jesus was considered to be a powerful shaman, and another attraction was that the name Jesus sounded like Yesu, the Mongol number "9". It was a sacred number to the Mongols, and was also the name of Genghis Khan's father, Yesugei. However, somewhat in contradiction to Weatherford, there is written evidence of a permanent Nestorian church in Karakorum and archeological evidence for other permanent church buildings in Olon Süme and Ukek. The use of non-permanent (yurt) churches is also well-documented.

Again according to Weatherford, the Mongols also adapted the Christian cross to their own belief system, making it sacred because it pointed to the four directions of the world. They had varied readings of the Scriptures, especially feeling an affinity to the wandering Hebrew tribes. Christianity also allowed the eating of meat (different from the vegetarianism of the Buddhists). And of particular interest to the hard-drinking Mongols, they enjoyed that the consuming of alcohol was a required part of church services.

Women in Mongolia were known to indicate their faith by wearing an amulet inscribed with a cross, or to be tattooed with a cross.

Keraite and Naiman Christian tribes

The Keraite tribe of the Mongols were converted to Nestorianism early in the 11th century. Other tribes evangelized entirely or to a great extent during the 10th and 11th centuries were the Naiman tribe. The Kara-Khitan Khanate also had a large proportion of Nestorian Christians, mingled with Buddhists and Muslims.

An account of the conversion of the Keraite is given by the 13th century West Syrian historian, Gregory Bar Hebraeus, who documented a 1009 letter by bishop Abdisho of Merv to the Patriarch John VI which announced the conversion of the Keraits to Christianity. According to Hebraeus, in the early 11th century, a Keraite king lost his way while hunting in the high mountains. When he had abandoned all hope, a saint, Mar Sergius, appeared in a vision and said, "If you will believe in Christ, I will lead you lest you perish." The king returned home safely, and when he later met Christian merchants, he remembered the vision and asked them about their faith. At their suggestion, he sent a message to the Metropolitan of Merv for priests and deacons to baptize him and his tribe. As a result of the mission that followed, the king and 20,000 of his people were baptized.

The legend of Prester John was also connected with the Nestorian rulers of the Keraite. Though the identity of Prester John was linked with individuals from other areas as well, such as India or Ethiopia, in some versions of the legend, Prester John was explicitly identified with the Christian Mongol Toghrul.

Relations with Christian nations

Main article: Franco-Mongol alliance

Some military collaboration with Christian powers took place in 1259–1260. Hetoum I of Cilician Armenia and his son-in-law Bohemond VI of Antioch had submitted to the Mongols, and, as did other vassal states, provided troops in the Mongols' expansion. The founder and leader of the Ilkhanate in 1260, Hulagu, was generally favourable to Christianity: his mother was Christian, his principal wife Doquz Khatun was a prominent Christian leader in the Ilkhanate, and at least one of his key generals, Kitbuqa, was also Christian. A later descendant of Hulagu, the Ilkhan Arghun, sent the Nestorian monk Rabban Bar Sauma as an ambassador to Western courts to offer an alliance between the Mongols and the Europeans. While there, Bar Sauma explained the situation of the Nestorian faith to the European monarchs:

"Know ye, O our Fathers, that many of our Fathers (Nestorian missionaries since the 7th century) have gone into the countries of the Mongols, and Turks, and Chinese and have taught them the Gospel, and at the present time there are many Mongols who are Christians. For many of the sons of the Mongol kings and queens have been baptized and confess Christ. And they have established churches in their military camps, and they pay honour to the Christians, and there are among them many who are believers."

— Travels of Rabban Bar Sauma

Upon his return, Bar Sauma wrote an elaborate account of his journey, which is of keen interest to modern historians, as it was the first account of Europe as seen through Eastern eyes.

Influence of Catholic Christianity

Main article: Christianity in Asia

The type of Christianity which the Mongols practiced was an Eastern Syriac form, which had an independent hierarchy from Western doctrine since the Nestorian Schism in the 5th century. Over the centuries, much of Europe had become unaware that there were any Christians in central Asia and beyond, except for vague legends of a Prester John, a Christian king from the East who many hoped would come to help with the Crusades and the fight for the Holy Land. Even after contacts were re-established, there were still Western missionaries who proceeded eastward, to try and convert the Mongols to Roman Catholicism, away from what was regarded as heretical Nestorianism. Some contacts were with the capital of the Mongols, first in Karakorum and then Khanbaliq (Beijing) in Mongol-conquered China. A larger number of contacts were with the closest of the Mongol states, the Ilkhanate in what today is Iran, Iraq, and Syria.

As early as 1223, Franciscan missionaries had been traveling eastward to visit the prince of Damascus and the Caliph of Baghdad. In 1240, nine Dominicans led by Guichard of Cremone are known to have arrived in Tiflis, the capital of Christian Georgia, by the orders of Pope Gregory IX. Georgia submitted to the advancing Mongols in 1243, so as the missionaries lived for five years in the Georgian realm, much of it was in contact or in close proximity with the Mongols. In 1245, Pope Innocent IV sent a series of four missions to the Mongols. The first was led by the Dominican André de Longjumeau, who had already been sent to Constantinople once by Saint Louis to acquire the Crown of thorns from Baldwin II. His travels are known by the reports of Matthew Paris. Three other missions were sent between March and April 1245, led respectively by the Dominican Ascelin of Cremone (accompanied by Simon de Saint-Quentin, who later wrote the account of the mission in Historia Tartarorum), the Franciscan Lawrence of Portugal, and another Franciscan, John of Plano Carpini.

In 1253, the Franciscan William of Rubruck traveled to Karakorum, the western Mongol capital, and sought permission to serve its people in the name of Christ. He was received courteously, but forbidden to engage in missionary work or remain in the country. At one point of his stay among the Mongols, William did enter into a famous competition at the Mongol court. The khan encouraged a formal debate between the Christians, Buddhists, and Muslims, to determine which faith was correct, as determined by three judges, one from each faith. When William returned to the West, he wrote a 40-chapter document on the customs and geography of the Mongols. Armenian King Hethum I, Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William Rubruck visited Mongolia.

Dominican missionaries to the Ilkhanate included Ricoldo of Montecroce and Barthelemy of Bologna, who later became the bishop in the Ilkhanate capital of Maragha. By the year 1300, there were numerous Dominican and Franciscan convents in the Il-Khanate. About ten cities had such institutions, including Maragha, Tabriz, Sultaniye, Tifflis, and Erzurum. To help with coordination, the Pope established an archbishop in the new capital of Sultaniye in 1318 in the person of Francon de Pérouse, who was assisted by six bishops. His successor in 1330 was Jean de Cor.

In 1302, the Nestorian Catholicos Mar Yaballaha III, who as a young man had accompanied the older Rabban Bar Sauma from Khanbaliq (Beijing), sent a profession of faith to the Pope. He thereby formalized his conversion to Roman Catholicism, though a 1304 letter from him to the pope indicated that his move had been strongly opposed by the local Nestorian clergy.

Mongol-European contacts diminished as Mongol power waned in Persia. In 1295, Ghazan (great-grandson of Hulagu) formally adopted Islam when he took the throne of the Ilkhanate in 1295, as did Berke along with other Golden Horde leaders.

In his own letters to the Mongol ruler in 1321 and 1322, the Pope still expressed his hope that the Mongol ruler would convert to Christianity. Between 500 and 1000 converts in each city were numbered by Jean of Sultaniye.

By the 14th century, the Mongols had effectively disappeared as a political power.

Catholic missions to Mongol China

In 1271, the Polo brothers brought an invitation from Kublai Khan to Pope Gregory X, imploring him that a hundred teachers of science and religion be sent to reinforce the Christianity already present in his vast empire. This came to naught due to the hostility of influential Nestorians within the Mongol court, who objected to the introduction of the Western (Roman Catholic) form of Christianity to supplant their own Nestorian doctrine.

In 1289, Pope Nicholas IV sent the Franciscan John of Monte Corvino, who became China's first Roman Catholic missionary. He was significantly successful, translated the New Testament and Psalms into the Mongol language, built a central church, and within a few years (by 1305) could report six thousand baptized converts. But the work was not easy. He was often opposed by the Nestorians, whose style of Eastern Christianity was different from John's Western version. But the Franciscan mission continued to grow, other priests joined him and centers were established in the coastal provinces of Jiangsu (Yangzhou), Zhejiang (Hangzhou) and Fujian (Zaitun). Following the death of Monte Corvino, an embassy to the French Pope Benedict XII in Avignon was sent by Toghun Temür, the last Mongol emperor in the Yuan dynasty of China, in 1336. The Mongol ruler requested a new spiritual guide to replace Monte Corvino, so in 1338, a total of 50 ecclesiastics were sent by the Pope to Beijing, among them John of Marignolli.

Two massive catastrophes hastened the extinction of this second wave of missionaries to China. First, the Black Death during the latter half of the fourteenth century in Europe so depleted Franciscan houses that they were unable to sustain the mission to China. Second, the Mongol-created Yuan dynasty in China began to decline. The native Chinese rose up and drove out the Mongols, thereby launching the Ming dynasty in 1368. By 1369, all Christians, whether Roman Catholic or Syro-Oriental, were expelled. With the end of Mongol rule in the 14th century, Christianity almost disappeared in mainland Asia, with three of the four principal Mongol khanates embracing Islam.

See also

Notes

- Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010 ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- "E-Aspac". Archived from the original on 2006-11-07. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- Weatherford, p. 28

- ^ World Religions: Eastern Traditions. Edited by Willard Gurdon Oxtoby (2nd ed.). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 434. ISBN 0-19-541521-3. OCLC 46661540.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "The Silk Road", Frances Wood, p.118 "William of Ribruk was shocked to discover that there were, indeed, Christians at the Mongol court, but that they were schismatic Nestorians (...) Nestorians had long been active along the Silk Road. Their existence in Tang China is testified by the "Nestorian monument", a stela still to be seen in the forest of Stelae in Xi'an"

- Foltz "Religions of the Silk Road", p.90-150

- For extensive detail and the testimony of Rabban Bar Sauma, see "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. Online

- "Early in the eleventh century their ruler had been converted to Nestorian Christianity, together with most of his subjects; and the conversion brought the Keraites into touch with the Uighur Turks, amongst whom were many Nestorians", Runciman, p.238

- For these four tribes: Roux, p.39-40

- Grousset, Empire, p. 165

- "In 1196, Genghis Khan succeeded in the unification under his authority of all the Mongol tribes, some of which had been converted to Nestorian Christianity" "Les Croisades, origines et conséquences", p.74

- Weatherford, p. 58

- ^ Runciman, p.246

- Under Mongka "The chief religious influence was that of the Nestorian Christians, to whom Mongka showed especial favour in memory of his mother Sorghaqtani, who had always remained loyal to her faith" Runciman, p.296

- "Sorghaqtani, a Kerait by birth and, like all her race, a devout Nestorian Christian", Runciman, p.293

- "His principal Empress, Kutuktai, and many other of his wives also were Nestorians", Runciman, p.296

- "This remarkable lady was a Kerait princess, the granddaughter of Toghrul Khan and cousin, therefore of Hulagu's mother. She was a passionate Nestorian, who made no secret of her dislike of Islam and her eagerness to help Christians of every sect", Runciman, p.299

- "Early in 1253 a report reached Acre that one of the Mongol princes, Sartaq, son of Batu, had been converted to Christianity", Runciman, p.280. See Alexander Nevsky for details.

- "Kitbuqa, as a Christian himself, made no secret of his sympathies", Runciman, p.308

- Grousset, p.698

- Weatherford, p. 135

- "William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols". depts.washington.edu.

- ^ Tjalling Halbertsma, Nestorian remains of Inner Mongolia : discovery, reconstruction and appropriation, p. 88ff

- "Ancient City Ruled by Genghis Khan's Heirs Revealed". Live Science. 24 October 2014.

- Weatherford, p. 29. "Jesus was considered an important and powerful shaman, and the cross was sacred as the symbol of the four directions of the world. As a pastoral people, the steppe tribes felt very comfortable with the pastoral customs and beliefs of the ancient Hebrew tribes as illustrated in the Bible. Perhaps above all, the Christians ate meat, unlike the vegetarian Buddhists; and in contrast to the abstemious Muslims, the Christians not only enjoyed drinking alcohol, but they even prescribed it as a mandatory part of their worship service."

- Li, Tang (2006). "Sorkaktani Beki: A prominent Nestorian woman at the Mongol Court". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter (eds.). Jingjiao: the Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Steyler Verlagsbuchhandlung. ISBN 978-3-8050-0534-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Roux, p.107

- Roux, L'Asie Centrale, p.241

- ^ Grousset, p. 581.

- Moffett, A History of Christianity in Asia pp. 400-401.

- "The Monks of Kublai Khan". www.aina.org.

- ^ Roux, Les explorateurs, pp. 95–97

- Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. p. 173.

- Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 670–. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- Roux, ‘’Histoire de l’Empire Mongol’’, p. 439

- Luisetto, p.99-100

- Roux, Histoire, p. 440

- Jackson, p. 314

- The Encyclopedia Americana, By Grolier Incorporated, p. 680

References and further reading

- Grousset, René (2006). Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291. Editions Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-02569-4.

- "Franco-Persian relations". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China.

- "The history and Life of Rabban Bar Sauma, translated from the Syriac by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

- Foltz, Richard (2010). Religions of the Silk Road : premodern patterns of globalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1.

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1993). Histoire de l'Empire Mongol (in French). Fayard. ISBN 2-213-03164-9.

- Weatherford, Jack (2004). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80964-4.

- Luisetto, Frédéric (2007). Arméniens et autres Chrétiens d'Orient sous la domination Mongole (in French). Geuthner. ISBN 978-2-7053-3791-9.

- Mahé, Annie; Mahé, Jean-Pierre (2005). L'Arménie à l'épreuve des siècles. Coll. “Découvertes Gallimard” (in French). Vol. 464. Paris: Éditions Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-031409-6.

- Rossabi, Morris (1992). Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 4-7700-1650-6.

| Eastern Christianity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural area of Christian traditions that developed since Early Christianity in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, North and East Africa, Asia Minor, South India, and parts of the Far East. | ||||||||

| Main divisions |

| Christ Pantocrator (circa 1261) in Hagia Sophia | ||||||

| History |

| |||||||

| Scriptures | ||||||||

| Theology | ||||||||

| Worship | ||||||||

| Mongol Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Timeline of the Mongol Empire | |||||||||||