| Revision as of 06:42, 18 November 2006 editHillock65 (talk | contribs)4,431 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:11, 20 January 2025 edit undoOnel5969 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers939,373 editsm Disambiguating links to Esotericism (link changed to Western esotericism) using DisamAssist. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Concept of rebirth in different physical form}} | |||

| :''"Past Lives" redirects here. For the 2002 Black Sabbath album, see ].'' | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2023}} | |||

| <!-- THIS ARTICLE IS ALREADY VERY LARGE. PLEASE ENSURE ANY ADDITIONS TO THE TEXT ARE FACTUAL, PRECISE AND CONCISE - OTHERWISE THEY WILL BE REMOVED. PLEASE CHECK THE DISCUSSION PAGE FOR MORE INFORMATION. --> | |||

| {{Redirect2|Reincarnate|Past lives|other uses|Reincarnation (disambiguation)|and|Past Lives (disambiguation){{!}}Past Lives}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Resurrection}} | |||

| {{For|the Futurama episode|Reincarnation (Futurama)}} | |||

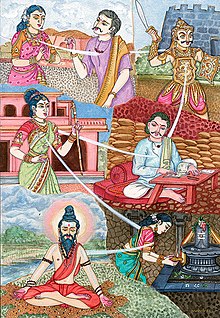

| ]]] | |||

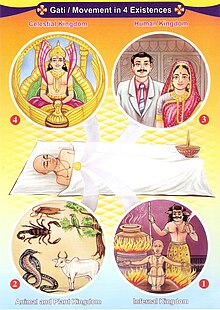

| ], a ] travels to any one of the four states of existence after death depending on its ]s.]] | |||

| '''Reincarnation''', also known as '''rebirth''' or '''transmigration''', is the ] or ] concept that the non-physical essence of a living ] begins a new ] in a different physical form or ] after biological ].<ref>{{cite book |first =Norman C. |last=McClelland |title=Encyclopedia of Reincarnation and Karma |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=S_Leq4U5ihkC |year =2010 |publisher =McFarland |isbn =978-0-7864-5675-8 |access-date =2016-09-25|archive-date =2016-11-26|archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20161126104519/https://books.google.com/books?id=S_Leq4U5ihkC|url-status =live |pages=24–29, 171}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last1 =Juergensmeyer | first1 = Mark | last2 = Roof | first2 = Wade Clark | year = 2011 | title = Encyclopedia of Global Religion | publisher = SAGE Publications | isbn = 978-1-4522-6656-5 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=WwJzAwAAQBAJ | access-date = 2016-09-25 | archive-date = 2019-03-31 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20190331224443/https://books.google.com/books?id=WwJzAwAAQBAJ | url-status = live |pages =271–272}}</ref> In most beliefs involving reincarnation, the ] of a human being is ] and does not disperse after the physical body has perished. Upon death, the soul merely becomes transmigrated into a newborn baby or into an animal to continue its ]. (The term "transmigration" means the passing of a soul from one body to another after death.) | |||

| '''Reincarnation''', literally "to be made flesh again", as a doctrine or ] belief, holds the notion that some essential part of a living being (or in some variations, only ]s) can survive ] in some form, with its integrity partly or wholly retained, to be reborn in a new body. This part is often referred to as the ] or ], the 'Higher or True Self', 'Divine Spark', 'I' or the 'Ego' (not to be confused with the ] as defined by psychology). | |||

| Reincarnation ('']'') is a central tenet of ] such as ], ], ], and ].{{Sfn|Juergensmeyer|Roof|2011|pp= 271–272}}<ref>{{cite book | |||

| In such beliefs, a new ] is developed during each life in the physical ], based upon past integrated experience and new acquired experiences, but some part of the being remains constantly present throughout these successive lives as well. It is usually believed that there is interaction between ] of certain experiences, or lessons intended to happen during the physical life, and the ] action of the individual as they live that life. | |||

| |first =Stephen J. |last =Laumakis |title =An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy |url =https://books.google.com/books?id=_29ZDAcUEwYC |year =2008 |publisher =Cambridge University Press |isbn =978-1-139-46966-1 |access-date =2016-09-25 |archive-date =2017-01-21 |archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20170121233453/https://books.google.com/books?id=_29ZDAcUEwYC |url-status =live |pages =90–99}}</ref><ref name="Gross1993p148">{{cite book |author =Rita M. Gross |title =Buddhism After Patriarchy: A Feminist History, Analysis, and Reconstruction of Buddhism |url =https://archive.org/details/buddhismafterpat00gros |url-access =registration |year =1993|publisher =State University of New York Press|isbn =978-1-4384-0513-1 |page =}}</ref><ref>] (1996), ''An Introduction to Hinduism'', Cambridge University Press</ref> In various forms, it occurs as an esoteric belief in many streams of ], in certain ] (including ]), and in some beliefs of the ]<ref>Gananath Obeyesekere, ''Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth''. University of California Press, 2002, p. 15.</ref> and of ] (though most believe in an afterlife or ]).<ref>Crawley{{full|date= September 2022}}</ref> Some ] historical figures, such as ], ], and ], expressed belief in the soul's rebirth or migration ('']'').<ref>see Charles Taliaferro, Paul Draper, Philip L. Quinn, ''A Companion to Philosophy of Religion''. John Wiley and Sons, 2010, p. 640, {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221212163105/https://books.google.com/books?id=SSCx-67Tk6cC&pg=PA640&dq=reincarnation+and+rebirth&cd=8#v=onepage&q=reincarnation%20and%20rebirth&f=false |date =2022-12-12 }}</ref> | |||

| Although the majority of denominations within ] do not believe that individuals reincarnate, particular groups within these religions do refer to reincarnation; these groups include the mainstream historical and contemporary followers of ], ], ], the ],<ref>Hitti, Philip K (2007) . ''Origins of the Druze People and Religion, with Extracts from their Sacred Writings (New Edition)''. Columbia University Oriental Studies. '''28'''. London: Saqi. pp. 13–14. {{ISBN |0-86356-690-1}}</ref> ], ],<ref>{{Cite book |last1 =Fernández Olmos |first1 =Margarite |url =https://www.worldcat.org/title/702357503 |title =Creole religions of the Caribbean: an introduction from Vodou and Santería to Obeah and Espiritismo |last2 =Paravisini-Gebert |first2 =Lizabeth |publisher =New York University Press |year =2011 |isbn =978-0-8147-6227-1 |edition =2 |series =Religion, race, and ethnicity |location =New York |pages =186 |oclc =702357503}}</ref> and the ].<ref>] (1985) ''The Rosicrucian Christianity Lectures (Collected Works)'': {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100629063357/http://www.rosicrucian.com/rcl/rcleng01.htm#lecture1 |date =2010-06-29 }}. Oceanside, California. 4th edition. {{ISBN|0-911274-84-7}}</ref> Recent scholarly research has explored the historical relations between different sects and their beliefs about reincarnation. This research includes the views of ], ], ], ], and the ] of the ], as well as those in Indian religions.<ref>For discussion of the mutual influence of ancient Greek and Indian philosophy regarding these matters, see '']'' by ]: | |||

| This doctrine is a central tenet within the majority of ] religious traditions such as ], ] and ] (from ]), and also ] and ]. It was common belief among the ] and ]{{fact}}. Many modern ]s also believe in reincarnation as do some ] movements, along with followers of ], practitioners of certain ] traditions, and students of ] philosophies. The ] concept of ] although often referred to as ''reincarnation'' differs significantly from the ] based traditions and New Age movements in that the "self" (or soul) does not reincarnate (]). | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |last1 = McEvilley | |||

| |first1 = Thomas | |||

| |author-link1 = Thomas McEvilley | |||

| |date = 7 February 2012 | |||

| |orig-date = 2002 | |||

| |title = The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies | |||

| |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=KmqCDwAAQBAJ | |||

| |publication-place = New York | |||

| |publisher = Simon and Schuster | |||

| |isbn = 9781581159332 | |||

| |access-date = 8 January 2025 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> In recent decades, many ] and ] have developed an interest in reincarnation,<ref name=Haraldsson2006>{{cite journal |last1=Haraldsson |first1=Erlendur |title=Popular psychology, belief in life after death and reincarnation in the Nordic countries, Western and Eastern Europe |journal=Nordic Psychology |date=January 2006 |volume=58 |issue=2 |pages=171–180 |doi=10.1027/1901-2276.58.2.171 |s2cid=143453837 }}</ref> and ] sometimes mention the topic.<ref> | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ==Conceptual definitions== | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| The word ''reincarnation'' derives from a ] term that literally means 'entering the flesh again'. Reincarnation refers to the ] that an aspect of every human being (or all living beings in some cultures) continues to exist after death. This aspect may be the soul, mind, consciousness, or something transcendent which is reborn in an interconnected cycle of existence; the transmigration belief varies by culture, and is envisioned to be in the form of a newly born human being, animal, plant, spirit, or as a being in some other non-human realm of existence.<ref>{{cite web|title=Encyclopædia Britannica|url=http://www.britannica.com/topic/reincarnation|access-date=25 June 2016|publisher=Concise.britannica.com}}</ref>{{Sfn|Keown|2013|pp=35–40}}<ref>{{cite book|author=Christopher Key Chapple|title=Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass|year=2006|isbn=978-81-208-2045-6|page=39|author-link=Christopher Chapple}}</ref> | |||

| Belief in reincarnation is an ancient phenomenon; in various guises humans have believed in a ] since the ]ians{{fact}}, perhaps earlier, and ancient ]s containing both people and possessions may testify to beliefs that a person would have need for their treasured possessions once again despite physical death. | |||

| An alternative term is ''transmigration'', implying migration from one life (body) to another.<ref>{{cite web|author=Oxford Dictionaries|year=2016|title=Transmigration|url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/transmigrate|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140105185254/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/transmigrate|archive-date=January 5, 2014|publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> The term has been used by modern philosophers such as ]<ref>{{cite web|author=Karl Sigmund|title=Gödel Exhibition: Gödel's Century|url=http://www.goedelexhibition.at/goedel/goedel.html|access-date=6 December 2011|publisher=Goedelexhibition.at|archive-date=21 October 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161021185849/http://www.goedelexhibition.at/goedel/goedel.html}}</ref> and has entered the English language. | |||

| In brief, there are several common concepts of a future life. In each of them either the person, or some essential component that defines that person (the ] or ]) persists in continuing existence: | |||

| * '''Reincarnation''' in human form. | |||

| : Successive lives on earth, usually including a belief in a passage through the ] or ] between death and rebirth. This is the most common use of '''reincarnation''' (also called "rebirth"). In many versions, eventually there is the potential to escape the cycle, e.g. by joining ], or achieving ], some kind of ], a ], entering a spiritual realm, etc. | |||

| * ''']''' | |||

| : Beings die, and are returned to this or another existence continually, their form upon return being of a 'higher' or 'lower' kind depending upon the ] (] quality) of their present life. This presupposes interchange between human and animal souls, at a minimum; plants and stone may be included, as well. | |||

| * '''Last Day''' | |||

| : People live only one life. After death, they may return to the earth or be revived in some final ], or at some final battle (eg the ] ]). They may go to heaven or hell at that time, or live again and repopulate the earth. This is an ] vision of the future. | |||

| * Related to these, but no longer including a return to embodied form, are beliefs in an ''']''' | |||

| : People live on this earth, and then live in some kind of afterlife for the rest of eternity - variously called ] (]) or ], or the ], or some ], or similar. They do not return to earth as such. | |||

| The Greek equivalent to reincarnation, '']'' ({{Langx|el|μετεμψύχωσις|label=none}}), derives from ''meta'' ('change') and {{Transl|el|empsykhoun}} ('to put a soul into'),<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160818075859/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=metempsychosis |date=2016-08-18 }}, Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper (2015)</ref> a term attributed to ].<ref>] (2014), {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081007201148/http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pythagoras |date=2008-10-07 }} Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University</ref> Another Greek term sometimes used synonymously is '']'', 'being born again'.<ref>{{cite web|title=Heart of Hinduism: Reincarnation and Samsara|url=http://hinduism.iskcon.com/concepts/102.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110419232238/http://hinduism.iskcon.com/concepts/102.htm|archive-date=19 April 2011|access-date=6 December 2011|publisher=Hinduism.iskcon.com}}</ref> | |||

| Beliefs in reincarnation or transmigration are widespread amongst religions and beliefs, some seeing it as part of the religion, others seeing in it an answer to many common moral and existential dilemmas, such as "]" and "why do bad things sometimes appear to happen to good people". Reincarnation is therefore a claim that a person has been or will be on this earth again in a different ]. It suggests that there is a connection between apparently disparate human lifetimes, and (in most cases) that there may even be covert evidence of continuity between different people's lifetimes, if looked for. Proponents claim this is indeed the case, whilst critics tend to reject the notion due to its ] implications or non-acceptance by ] due to other possible explanations of the phenomenon not yet eliminated from consideration. Such evidence tends to be of three kinds: | |||

| * Tradition commonly holds that certain people (such as the ] or ]s in ]) can be identified by looking for a child born at a specified time after their death, and by certain signs and knowledge that such a child has of their predecessor life beyond the norm. In the case of Buddhism there are well defined tests of such a child. | |||

| * In Western culture, ] or ] has at times provided what are claimed to be past life memories, some of which can in theory be verified, and some of which might be tested for fraudulent claims. Some aspects of these tend to be quite consistent in some ways (beings of light, messages of love and peace, etc), a factor which to some people lends credence to the idea, and to others supports that "something" is going on but without certainty what that might be. | |||

| * Last, for many people, the evidence is internal and ], personal belief or experience. This may not be proof as such, but to them, qualifies as sufficient evidence to believe it. | |||

| Rebirth is a key concept found in major Indian religions, and discussed using various terms. Reincarnation, or '']'' ({{Langx|sa|पुनर्जन्मन्}}, 'rebirth, transmigration'),<ref name="Monier-Williams582">{{cite book|author=Monier Monier-Williams|title=A Sanskrit-English Dictionary|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1872|page=582}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Ronald Wesley Neufeldt|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iaRWtgXjplQC&pg=PA106|title=Karma and Rebirth: Post Classical Developments|publisher=State University of New York Press|year=1986|isbn=978-0-87395-990-2|pages=88–89}}</ref> is discussed in the ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, with many alternate terms such as ''punarāvṛtti'' ({{Langx|sa|पुनरावृत्ति|label=none}}), ''punarājāti'' ({{Langx|sa|पुनराजाति|label=none}}), ''punarjīvātu'' ({{Langx|sa|पुनर्जीवातु|label=none}}), ''punarbhava'' ({{Langx|sa|पुनर्भव|label=none}}), ''āgati-gati'' ({{Langx|sa|आगति-गति|label=none}}, common in ] text), ''nibbattin'' ({{Langx|sa|निब्बत्तिन्|label=none}}), ''upapatti'' ({{Langx|sa|उपपत्ति|label=none}}), and ''uppajjana'' ({{Langx|sa|उप्पज्जन|label=none}}).<ref name="Monier-Williams582" /><ref>{{cite book|author1=Thomas William Rhys Davids|title=Pali-English Dictionary|author2=William Stede|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass|year=1921|isbn=978-81-208-1144-7|pages=95, 144, 151, 361, 475}}</ref> These religions believe that reincarnation is cyclic and an endless ], unless one gains spiritual insights that ends this cycle leading to liberation.{{Sfn|Juergensmeyer|Roof|2011|pp=271–272}}{{sfn|Laumakis|2008|pp=90–99}} The reincarnation concept is considered in Indian religions as a step that starts each "cycle of aimless drifting, wandering or mundane existence",{{Sfn|Juergensmeyer|Roof|2011|pp=271–272}} but one that is an opportunity to seek spiritual liberation through ethical living and a variety of meditative, yogic (''marga''), or other spiritual practices.<ref>{{harv|John Bowker|2014|pp=84–85}} Gavin Flood (2010), ''Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism'' (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Volume II, Brill, {{ISBN|978-90-04-17893-9}}, pp. 881–884</ref> They consider the release from the cycle of reincarnations as the ultimate spiritual goal, and call the liberation by terms such as ], ], ''mukti'' and ''kaivalya''.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Klostermaier |first1=Klaus |title=Mokṣa and Critical Theory |journal=Philosophy East and West |date=1985 |volume=35 |issue=1 |pages=61–71 |id={{ProQuest|1301471616}} |doi=10.2307/1398681 |jstor=1398681 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Thomas |first1=Norman E. |title=Liberation for Life: A Hindu Liberation Philosophy |journal=Missiology: An International Review |date=April 1988 |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=149–162 |doi=10.1177/009182968801600202 |s2cid=170870237 }}</ref><ref>Gerhard Oberhammer (1994), La Délivrance dès cette vie: Jivanmukti, Collège de France, Publications de l'Institut de Civilisation Indienne. Série in-8°, Fasc. 61, Édition-Diffusion de Boccard (Paris), {{ISBN|978-2-86803-061-0}}, pp. 1–9</ref> | |||

| Though some claims to recall past lives have been documented and tested in a scientific manner{{fact}}, mainstream science does not accept reincarnation as a proven phenomenon. | |||

| '']'', ''Gilgul neshamot'', or ''Gilgulei Ha Neshamot'' ({{Langx|he|גלגול הנשמות}}) is the concept of reincarnation in ] ], found in much ] among ]. ''Gilgul'' means 'cycle' and ''neshamot'' is 'souls'. Kabbalistic reincarnation says that humans reincarnate only to humans unless ]/]/] chooses. | |||

| ==Reincarnation in various religions, traditions and philosophies== | |||

| Philosophical and religious beliefs regarding the existence or non-existence of an enduring ']' have a direct bearing on how reincarnation is viewed within a given tradition. There are large differences in philosophical beliefs regarding the nature of the ] (also known as the ] or ]) amongst the ] such as Hinduism and Buddhism. Some schools deny the existence of a 'self', while others claim the existence of an eternal, personal self, and still others say there is neither self or no-self, as both are false. Each of these beliefs has a direct bearing on the possible nature of reincarnation, including such concepts of ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| === Eastern religions and traditions === | |||

| ==== Hinduism ==== | |||

| {{Main|Samsara}} | |||

| ===Origins=== | |||

| In ] the concept of reincarnation is first recorded in the ]s (c. 800 BCE - ), which are philosophical and religious texts composed in ]. The doctrine of reincarnation is absent in the ], which are generally considered the oldest of the Hindu scriptures. | |||

| The origins of the notion of reincarnation are obscure.<ref>{{cite book|publisher=Theosophical Society in America|title=Reincarnation: The Hope of the World|page=15|author=Irving Steiger Cooper|year=1920}}</ref> Discussion of the subject appears in the philosophical traditions of ]. The Greek ] discussed reincarnation, and the Celtic ] are also reported to have taught a doctrine of reincarnation.<ref>] thought the druids might have been influenced by the teachings of ]. Diodorus Siculus v.28.6; Hippolytus ''Philosophumena'' i.25.</ref> | |||

| According to ], the soul (]) is immortal, while the body is subject to birth and death. The ] states that: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| Worn-out garments are shed by the body; | |||

| ===Early Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism=== | |||

| Worn-out bodies are shed by the dweller within the body. New bodies are donned | |||

| The concepts of the cycle of birth and death, '']'', and ] partly derive from ] that arose in India around the middle of the first millennium BCE.<ref>Flood, Gavin. Olivelle, Patrick. 2003. ''The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism.'' Malden: Blackwell. pp. 273–274. "The second half of the first millennium BCE was the period that created many of the ideological and institutional elements that characterize later Indian religions. The renouncer tradition played a central role during this formative period of Indian religious history....Some of the fundamental values and beliefs that we generally associate with Indian religions in general and Hinduism in particular were in part the creation of the renouncer tradition. These include the two pillars of Indian theologies: samsara—the belief that life in this world is one of suffering and subject to repeated deaths and births (rebirth); moksa/nirvana—the goal of human existence....."</ref> The first textual references to the idea of reincarnation appear in the ], ] and ] of the late ] (c. 1100 – c. 500 BCE), predating the ] and ].<ref name=damienkeown32>{{cite book|first=Damien |last=Keown |title=Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction |year=2013|publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-966383-5 |pages=28, 32–38 }}</ref>{{sfn|Laumakis|2008|p=}} Though no direct evidence of this has been found, the tribes of the ] valley or the ] traditions of ] have been proposed as another early source of reincarnation beliefs.<ref>Gavin D. Flood, ''An Introduction to Hinduism'', Cambridge University Press (1996), UK {{ISBN|0-521-43878-0}} p. 86 – "A third alternative is that the origin of transmigration theory lies outside of vedic or sramanian traditions in the tribal religions of the Ganges valley, or even in Dravidian traditions of south India."</ref> | |||

| by the dweller, like garments.<ref> Bhagavad Gita II.22, ISBN 1-56619-670-1</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| The idea of reincarnation, ''saṁsāra'', did exist in the early ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/rig-veda-english-translation/d/doc839140.html|title=Rig Veda 10.58.1 |date=27 August 2021|website=www.wisdomlib.org|access-date=8 October 2023}}</ref><ref>A.M. Boyer: "Etude sur l'origine de la doctrine du samsara." ''Journal Asiatique'', (1901), Volume 9, Issue 18, S. 451–453, 459–468</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Krishan |first1=Y. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_Bi6FWX1NOgC |title=The Doctrine of Karma: Its Origin and Development in Brāhmaṇical, Buddhist, and Jaina Traditions |last2=Krishan |first2=Yuvraj |date=1997 |publisher=Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan |isbn=978-81-208-1233-8 |pages=3–37 |language=en}}</ref> The early Vedas mention the doctrine of ] and rebirth.{{sfn|Laumakis|2008|pp=90–99}}<ref>{{cite book|title=A Constructive Survey of Upanishadic Philosophy|author=R.D.Ranade|publisher=Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan |pages=147–148 |year = 1926 |url= https://archive.org/stream/A.Constructive.Survey.of.Upanishadic.Philosophy.by.R.D.Ranade.1926.djvu/A.Constructive.Survey.of.Upanishadic.Philosophy.by.R.D.Ranade.1926#page/n181/mode/2up |quote= There we definitely know that the whole hymn is address to a departed spirit, and the poet says that he is going to recall the departed soul in order that it may return again and live."}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Atsushi Hayakawa |title=Circulation of Fire in the Veda |year=2014| publisher=LIT Verlag Münster| isbn=978-3-643-90472-0| pages=66–67, 101–103 with footnotes}}</ref> It is in the early Upanishads, which are pre-] and pre-], where these ideas are developed and described in a general way.{{sfn|Laumakis|2008|p=90}}<ref name="amboyer">A.M. Boyer (1901), "Etude sur l'origine de la doctrine du samsara", ''Journal Asiatique'', Volume 9, Issue 18, pp. 451–453, 459–468</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=The way to Nirvana: six lectures on ancient Buddhism as a discipline of salvation|author=Vallee Pussin|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1917|pages=24–25}}</ref> Detailed descriptions first appear around the mid-1st millennium BCE in diverse traditions, including Buddhism, Jainism and various schools of ], each of which gave unique expression to the general principle.{{sfn|Laumakis|2008|pp=90–99}} | |||

| The idea that the soul (of any living being - including animals, humans and plants) reincarnates is intricately linked to ], another concept first introduced in the Upanishads. Karma (literally: action) is the sum of one's actions, and the force that determines one's next reincarnation. The cycle of death and rebirth, governed by karma, is referred to as ]. | |||

| ]<ref name="Kailas">{{cite book|author=K Kailasapathy|title=Tamil Heroic Poetry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kF9kAAAAMAAJ |year=1968|publisher=Clarendon Press|isbn=978-0-19-815434-1|page=1}}</ref> connotes the ancient ] and is the earliest known literature of ]. The Tamil tradition and legends link it to three literary gatherings around ]. According to ], a Tamil literature and history scholar, the most acceptable range for the Sangam literature is 100 BCE to 250 CE, based on the linguistic, prosodic and quasi-historic allusions within the texts and the ]s.{{sfn|Kamil Zvelebil|1974|pp=9–10 with footnotes}} There are several mentions of rebirth and moksha in the ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/purananuru-part-134|title=Poem: Purananuru – Part 134 by George L. III Hart|website=www.poetrynook.com|access-date=8 October 2023}}</ref> The text explains Hindu rituals surrounding death such as making riceballs called ] and cremation. The text states that good souls get a place in ] where ] welcomes them.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/purananuru-part-241|title=Poem: Purananuru – Part 241 by George L. III Hart|website=www.poetrynook.com|access-date=8 October 2023}}</ref> | |||

| Hinduism teaches that the soul goes on repeatedly being born and dying. One is reborn on account of desire: a person ''desires'' to be born because he or she wants to enjoy worldly pleasures, which can be enjoyed only through a body.<ref>See Bhagavad Gita XVI.8-20</ref> Hinduism does not teach that all worldly pleasures are sinful, but it teaches that they can never bring deep, lasting happiness or peace (''ānanda''). According to the Hindu sage ] - the world as we ordinarily understand it - is like a dream: fleeting and illusory. To be trapped in Samsara is a result of ignorance of the true nature of being. | |||

| The texts of ancient ] that have survived into the modern era are post-Mahavira, likely from the last centuries of the first millennium BCE, and extensively discuss the doctrines of rebirth and karma.<ref>{{cite book |first=Padmanabh |last=Jaini |editor=Wendy Doniger |title=Karma and Rebirth in Classical Indian Traditions |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_4WZTj3M71y0C |year=1980|publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-03923-0 |pages=217–236}}</ref><ref name=dundasp14>{{cite book|author= Paul Dundas|title=The Jains |year=2003|publisher= ]|isbn=978-0-415-26605-5 |pages= 14–16, 102–105 }}</ref> Jaina philosophy assumes that the soul ('']'' in Jainism; '']'' in Hinduism) exists and is eternal, passing through cycles of transmigration and rebirth.{{Sfn|Jaini|1980|pp=226–228}} After death, reincarnation into a new body is asserted to be instantaneous in early Jaina texts.<ref name=dundasp14/> Depending upon the accumulated karma, rebirth occurs into a higher or lower bodily form, either in heaven or hell or earthly realm.<ref>{{cite book|author=Kristi L. Wiley |title=The A to Z of Jainism |year=2009|publisher=Scarecrow |isbn=978-0-8108-6337-8 |page=186}}</ref>{{Sfn|Jaini|1980|pp=227-228}} No bodily form is permanent: everyone dies and reincarnates further. Liberation (''kevalya'') from reincarnation is possible, however, through removing and ending karmic accumulations to one's soul.<ref>{{cite book|author= Paul Dundas|title=The Jains |year=2003|publisher= Routledge|isbn=978-0-415-26605-5 |pages= 104–105 }}</ref> From the early stages of Jainism on, a human being was considered the highest mortal being, with the potential to achieve liberation, particularly through ].<ref>{{cite book|author=Jeffery D Long|title=Jainism: An Introduction|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ajAEBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT36|year=2013|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=978-0-85773-656-7|pages=36–37}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author= Paul Dundas|title=The Jains |year=2003|publisher= Routledge|isbn=978-0-415-26605-5 |pages= 55–59 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=John E. Cort|title=Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India| year=2001|publisher= Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-803037-9|pages=118–119}}</ref> | |||

| After many births, every person eventually becomes dissatisfied with the limited happiness that worldly pleasures can bring. At this point, a person begins to seek higher forms of happiness, which can be attained only through spiritual experience. When, after much spiritual practice (]), a person finally realizes his or her own divine nature—ie., realizes that the true "self" is the immortal soul rather than the body or the ego—all desires for the pleasures of the world will vanish, since they will seem insipid compared to spiritual ''ānanda''. When all desire has vanished, the person will not be reborn anymore.<ref>Rinehart, Robin, ed., ''Contemporary Hinduism''19-21 (2004) ISBN 1-57607-905-8</ref> | |||

| The ] discuss rebirth as part of the doctrine of '']''. This asserts that the nature of existence is a "suffering-laden cycle of life, death, and rebirth, without beginning or end".<ref name=jeffwilsonbudsam>{{cite book|author=Jeff Wilson|year= 2010|title= Saṃsāra and Rebirth, in Buddhism| publisher= Oxford University Press|isbn= 978-0-19-539352-1| doi=10.1093/obo/9780195393521-0141}}</ref><ref name="Trainor2004p63">{{cite book|first=Kevin |last=Trainor |title= Buddhism: The Illustrated Guide |year=2004|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-517398-7 |pages=62–63 }}; ''Quote:'' "Buddhist doctrine holds that until they realize nirvana, beings are bound to undergo rebirth and redeath due to their having acted out of ignorance and desire, thereby producing the seeds of karma".</ref> Also referred to as the wheel of existence ('']''), it is often mentioned in Buddhist texts with the term ''punarbhava'' (rebirth, re-becoming). Liberation from this cycle of existence, ''Nirvana'', is the foundation and the most important purpose of Buddhism.<ref name=jeffwilsonbudsam/><ref name="Conze2013p71">{{cite book|author=Edward Conze |title= Buddhist Thought in India: Three Phases of Buddhist Philosophy |year=2013|publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-134-54231-4|page=71|quote="Nirvana is the ''raison d'être'' of Buddhism, and its ultimate justification."}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | last =Gethin | first =Rupert | year =1998 | title =Foundations of Buddhism | publisher =Oxford University Press | isbn =978-0-19-289223-2 | page = | url =https://archive.org/details/foundationsofbud00rupe/page/119 }}</ref> Buddhist texts also assert that an ] person knows his previous births, a knowledge achieved through high levels of ].<ref>Paul Williams, Anthony Tribe, ''Buddhist thought: a complete introduction to the Indian tradition.'' Routledge, 2000, p. 84.</ref> Tibetan Buddhism discusses death, ] (an intermediate state), and rebirth in texts such as the '']''. While Nirvana is taught as the ultimate goal in the Theravadin Buddhism, and is essential to Mahayana Buddhism, the vast majority of contemporary lay Buddhists focus on accumulating good karma and acquiring merit to achieve a better reincarnation in the next life.<ref name="Merv Fowler 1999 65">{{cite book|author=Merv Fowler |title=Buddhism: Beliefs and Practices|year=1999|publisher=Sussex Academic Press |isbn=978-1-898723-66-0 |page=65|quote="For a vast majority of Buddhists in Theravadin countries, however, the order of monks is seen by lay Buddhists as a means of gaining the most merit in the hope of accumulating good karma for a better rebirth."}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Christopher Gowans|title=Philosophy of the Buddha: An Introduction|year=2004|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-46973-4|page=169}}</ref> | |||

| When the cycle of rebirth thus comes to an end, a person is said to have attained ], or salvation.<ref>Karel Werner, ''A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism'' 110 (Curzon Press 1994) ISBN 0-7007-0279-2</ref> While all schools of thought agree that moksha implies the cessation of worldly desires and freedom from the cycle of birth and death, the exact definition of salvation depends on individual beliefs. For example, followers of the ] school (often associated with ]) believe that they will spend eternity absorbed in the perfect peace and happiness that comes with the realization that all existence is One (]), and that the immortal soul is part of that existence. Thus they will no longer identify themselves as individual persons, but will see the "self" as a part of the infinite ocean of divinity, described as sat-chit-ananda (existence-knowledge-bliss). The followers of full or partial ] schools ("dualistic" schools, such as ]), on the other hand, perform their worship with the goal of spending eternity in a ], (spiritual world or heaven), in the blessed company of the Supreme being (i.e ] or ] for the ]s, ] for the ]). The two schools (Dvaita & Advaita) are not necessarily contradictory, however. A follower of one school may believe that both types of salvation are possible, but will simply have a personal preference to experience one or the other. Thus, it is said, the followers of Dvaita wish to "taste sugar," while the followers of Advaita wish to "become sugar."<ref>Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, Translation by Swami Nikhilananda (8th Ed. 1992) ISBN 0-911206-01-9</ref> | |||

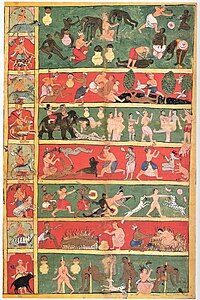

| In early Buddhist traditions, ''saṃsāra'' cosmology consisted of five realms through which the wheel of existence cycled.<ref name=jeffwilsonbudsam/> This included hells ('']''), ] ('']''), animals ('']''), humans ('']''), and gods ('']s'', heavenly).<ref name=jeffwilsonbudsam/><ref name="Trainor2004p63"/><ref>{{cite book|author=Robert DeCaroli |title=Haunting the Buddha: Indian Popular Religions and the Formation of Buddhism |year=2004|publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-803765-1|pages=94–103}}</ref> In latter Buddhist traditions, this list grew to a list of six realms of rebirth, adding demigods ('']'').<ref name=jeffwilsonbudsam/><ref>{{cite book|author=Akira Sadakata|title=Buddhist Cosmology: Philosophy and Origins|year=1997|publisher= Kōsei Publishing 佼成出版社, Tokyo|isbn=978-4-333-01682-2|pages=68–70}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Buddhism ==== | |||

| ], or reincarnation.]] | |||

| {{Main|Rebirth (Buddhist)}} | |||

| ====Rationale==== | |||

| Since according to Buddhism there is no permanent and unchanging ] (identify) there can be no ] in the strict sense. However, the Buddha himself referred to his past-lives. It can be inferred that these existed only in the world of the mind and that this is furthermore exactly the same state as is perceived by the one experiencing (or immersed in) the cyclic manifestation of ]. | |||

| The earliest layers of Vedic text incorporate the concept of life, followed by an ] in heaven and hell based on cumulative virtues (merit) or vices (demerit).<ref>{{cite book|author1=James Hastings|author2=John Alexander Selbie|author3-link=Louis Herbert Gray|author3=Louis Herbert Gray|series=]|title=Volume 12: Suffering-Zwingli|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.500005|year=1922|publisher=T. & T. Clark|pages=616–618|author1-link=James Hastings}}</ref> However, the ancient Vedic ]s challenged this idea of afterlife as simplistic, because people do not live equally moral or immoral lives. Between generally virtuous lives, some are more virtuous; while evil too has degrees, and the texts assert that it would be unfair for people, with varying degrees of virtue or vices, to end up in heaven or hell, in "either or" and disproportionate manner irrespective of how virtuous or vicious their lives were.{{Sfn|Jessica Frazier|Gavin Flood|2011|pp=84–86}}<ref>{{cite book|author=Kusum P. Merh |title=Yama, the Glorious Lord of the Other World |year=1996|publisher=Penguin |isbn=978-81-246-0066-5 |pages=213–215}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author= Anita Raina Thapan|title=The Penguin Swami Chinmyananda Reader |year=2006|publisher=Penguin Books |isbn=978-0-14-400062-3 |pages=84–90 }}</ref> They introduced the idea of an afterlife in heaven or hell in proportion to one's merit.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Jessica Frazier |author2=Gavin Flood |title= The Continuum Companion to Hindu Studies |year=2011|publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=978-0-8264-9966-0|pages= 84–86 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author1=Patrul Rinpoche|author2-link=Dalai Lama|author2=Dalai Lama|title=The Words of My Perfect Teacher: A Complete Translation of a Classic Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism|year=1998|publisher=Rowman Altamira|isbn=978-0-7619-9027-7|pages=95–96|author1-link=Patrul Rinpoche}}</ref><ref name="Krishan1997p17">{{cite book|author=Yuvraj Krishan |title=The Doctrine of Karma: Its Origin and Development in Brāhmaṇical, Buddhist, and Jaina Traditions |year=1997|publisher= Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan|isbn=978-81-208-1233-8 |pages=17–27 }}</ref> | |||

| ====Comparison==== | |||

| Buddhism never rejected ], the process of rebirth; however, there are debates over what is reborn. In addition to the ], Tibetan Buddhists, also believe that a new-born child may be the rebirth of some important departed lama. In ], the substance that make up the impermanent "self" (]) of an important ] (like the ]) is said to be reborn into an infant born nine months after his decease. This process is said to occurs after years of crystallization of the skandhas through mental cultivation. And when the body dies, some of the crystallized skandhas (which normally dissolves at death), is said to attach itself to the consciousness. So that when the next rebirth occurs, the new person will have some of the old characters. This belief, however, does not contradict with Buddha's teaching on the impermanent nature of the ]. | |||

| Early texts of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism share the concepts and terminology related to reincarnation.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Williams |first1=Paul |last2=Tribe |first2=Anthony |last3=Wynne |first3=Alexander | year=2012 |title=Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-52088-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NOLfCgAAQBAJ |access-date=2016-09-25 |archive-date=2020-11-20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201120065316/https://books.google.com/books?id=NOLfCgAAQBAJ |url-status=live |pages=30–42}}</ref> They also emphasize similar virtuous practices and ] as necessary for liberation and what influences future rebirths.<ref name="damienkeown32"/><ref>{{cite book|author=Michael D. Coogan|title=The Illustrated Guide to World Religions | year=2003| publisher=Oxford University Press| isbn=978-0-19-521997-5| page=192}}</ref> For example, all three discuss various virtues—sometimes grouped as ] and ]s—such as ], ], ], ], ] for all living beings, ] and many others.<ref>{{cite book|author1=David Carpenter|author2=Ian Whicher|title=Yoga: The Indian Tradition|year=2003|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-135-79606-8|page=116}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Rita Langer |title=Buddhist Rituals of Death and Rebirth: Contemporary Sri Lankan Practice and Its Origins |year=2007|publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-134-15873-7 |pages=53–54 }}</ref> | |||

| Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism disagree in their assumptions and theories about rebirth. Hinduism relies on its foundational belief that the 'soul, Self exists' (] or ''attā''), while Buddhism aserts that there is 'no soul, no Self' (] or ''anatman'').<ref>{{cite book|author=Christmas Humphreys|title=Exploring Buddhism |year=2012|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-22877-3 |pages=42–43 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Brian Morris |title=Religion and Anthropology: A Critical Introduction |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PguGB_uEQh4C&pg=PA51 |year=2006|publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-85241-8|page=51|quote="(...) anatta is the doctrine of non-self, and is an extreme empiricist doctrine that holds that the notion of an unchanging permanent self is a fiction and has no reality. According to Buddhist doctrine, the individual person consists of five skandhas or heaps—the body, feelings, perceptions, impulses and consciousness. The belief in a self or soul, over these five skandhas, is illusory and the cause of suffering."}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Richard Gombrich|title=Theravada Buddhism|year=2006|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-90352-8|page=47|quote="(...) Buddha's teaching that beings have no soul, no abiding essence. This 'no-soul doctrine' (anatta-vada) he expounded in his second sermon."}}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151210185046/http://www.britannica.com/topic/anatta |date=2015-12-10 }}, Encyclopedia Britannica (2013), Quote: "Anatta in Buddhism, the doctrine that there is in humans no permanent, underlying soul. The concept of anatta, or anatman, is a departure from the Hindu belief in atman ("the self").";</ref><ref>Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, {{ISBN|978-0-7914-2217-5}}, p. 64; "Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence."</ref><ref>Edward Roer (Translator), {{Google books|3uwDAAAAMAAJ|Shankara's Introduction|page=2}} to ''Brihad Aranyaka Upanishad'', pp. 2–4;</ref><ref>Katie Javanaud (2013), {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150206211126/https://philosophynow.org/issues/97/Is_The_Buddhist_No-Self_Doctrine_Compatible_With_Pursuing_Nirvana |date=2015-02-06 }}, Philosophy Now;</ref><ref name=Loy1982/><ref>KN Jayatilleke (2010), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge, {{ISBN|978-81-208-0619-1}}, pp. 246–249, from note 385 onwards;</ref><ref name=johnplott3>John C. Plott et al (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-81-208-0158-5}}, p. 63, Quote: "The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism".</ref> Hindu traditions consider soul to be the unchanging eternal essence of a living being, which journeys through reincarnations until it attains self-knowledge.<ref>{{cite book|author=Bruce M. Sullivan|title=Historical Dictionary of Hinduism|year=1997|publisher=Scarecrow|isbn=978-0-8108-3327-2|pages=235–236 (See: Upanishads)}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Klaus K. Klostermaier|title=A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition|year=2007|publisher=State University of New York Press|isbn=978-0-7914-7082-4|pages=119–122, 162–180, 194–195}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Kalupahana |first=David J. |date=1992 |title=The Principles of Buddhist Psychology |location=Delhi |publisher=ri Satguru Publications |pages=38–39}}</ref> Buddhism, in contrast, asserts a rebirth theory without a Self, and considers realization of non-Self or Emptiness as Nirvana ('']''). | |||

| The Buddha has this to say on rebirth. Kutadanta continued: | |||

| The reincarnation doctrine in Jainism differs from those in Buddhism, even though both are non-theistic ] traditions.<ref name=naomiappleton76/><ref>{{cite book|author=Kristi L. Wiley|title=Historical Dictionary of Jainism|year=2004|publisher=Scarecrow|isbn=978-0-8108-5051-4|page=91}}</ref> Jainism, in contrast to Buddhism, accepts the foundational assumption that soul ('']'') exists and asserts that this soul is involved in the rebirth mechanism.<ref>{{cite book|author=Kristi L. Wiley|title=Historical Dictionary of Jainism|year=2004|publisher=Scarecrow|isbn=978-0-8108-5051-4|pages=10–12, 111–112, 119}}</ref> Furthermore, Jainism considers ] as an important means to spiritual liberation that ends the cycle of reincarnation, while Buddhism does not.<ref name=naomiappleton76>{{cite book|author=Naomi Appleton |title=Narrating Karma and Rebirth: Buddhist and Jain Multi-Life Stories |year=2014|publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-91640-0|pages=76–89 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Gananath Obeyesekere |title=Karma and Rebirth: A Cross Cultural Study |year=2006|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |isbn=978-81-208-2609-0 |pages=107–108 }};<br />{{cite book|author=Kristi L. Wiley|title=Historical Dictionary of Jainism|year=2004|publisher=Scarecrow|isbn=978-0-8108-5051-4|pages=118–119}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=John E. Cort|title=Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India | year=2001|publisher= Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-803037-9|pages=118–123}}</ref> | |||

| "Thou believest, O Master, that beings are reborn; | |||

| that they migrate in the evolution of life; | |||

| and that subject to the law of karma we must reap what we sow. | |||

| Yet thou teachest the non-existence of the soul! | |||

| Thy disciples praise utter self-extinction | |||

| as the highest bliss of Nirvana. | |||

| If I am merely a combination of the sankharas, | |||

| my existence will cease when I die. | |||

| If I am merely a compound of sensations and ideas and desires, | |||

| whither can I go at the dissolution of the body?" | |||

| ===Classical antiquity=== | |||

| Said the Blessed One: | |||

| {{see also|Metempsychosis}} | |||

| "O Brahman, thou art religious and earnest. | |||

| ] | |||

| Thou art seriously concerned about thy soul. | |||

| Early Greek discussion of the concept dates to the sixth century BCE. An early Greek thinker known to have considered rebirth is ] (fl. 540 BCE).<ref>Schibli, S., Hermann, Pherekydes of Syros, p. 104, Oxford Univ. Press 2001</ref> His younger contemporary ] (c. 570–c. 495 BCE<ref>"The dates of his life cannot be fixed exactly, but assuming the approximate correctness of the statement of Aristoxenus (ap. Porph. ''V.P.'' 9) that he left Samos to escape the tyranny of Polycrates at the age of forty, we may put his birth round about 570 BCE, or a few years earlier. The length of his life was variously estimated in antiquity, but it is agreed that he lived to a fairly ripe old age, and most probably he died at about seventy-five or eighty." ], (1978), ''A history of Greek philosophy, Volume 1: The earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans'', p. 173. Cambridge University Press</ref>), its first famous exponent, instituted societies for its diffusion. Some authorities believe that Pythagoras was Pherecydes' pupil, others that Pythagoras took up the idea of reincarnation from the doctrine of ], a ] religion, or brought the teaching from India. | |||

| Yet is thy work in vain because thou art lacking | |||

| in the one thing that is needful." | |||

| ] (428/427–348/347 BCE) presented accounts of reincarnation in his works, particularly the '']'', where Plato makes Socrates tell how Er, the son of ], miraculously returned to life on the twelfth day after death and recounted the secrets of the other world. There are myths and theories to the same effect in other dialogues, in the ] of the '']'',<ref>''The Dialogues of Plato'' (Benjamin Jowett trans., 1875 ed), vol. 2, p. 125</ref> in the '']'',<ref>''The Dialogues of Plato'' (Benjamin Jowett trans., 1875 ed), vol. 1, p. 282</ref> '']'' and '']''. The soul, once separated from the body, spends an indeterminate amount of time in the intelligible realm (see the ] in '']'') and then assumes another body. In the ''Timaeus'', Plato believes that the soul moves from body to body without any distinct reward-or-punishment phase between lives, because the reincarnation is itself a punishment or reward for how a person has lived.<ref>See Kamtekar 2016 for a discussion of how Plato's view of reincarnation changes across texts, especially concerning the existence of a distinct reward-or-punishment phase between lives. Rachana Kamtekar. 2016. "The Soul’s (After-) Life," ''Ancient Philosophy'' 36 (1):115–132.</ref> | |||

| "There is rebirth of character, | |||

| but no transmigration of a self. | |||

| Thy thought-forms reappear, | |||

| but there is no egoentity transferred. | |||

| The stanza uttered by a teacher | |||

| is reborn in the scholar who repeats the word." | |||

| In '']'', Plato has his teacher ], prior to his death, state: "I am confident that there truly is such a thing as living again, and that the living spring from the dead." However, ] does not mention Socrates as believing in reincarnation, and Plato may have systematized Socrates' thought with concepts he took directly from Pythagoreanism or Orphism. Recent scholars have come to see that Plato has multiple reasons for the belief in reincarnation.<ref>See Campbell 2022 for more on why Plato believes in reincarnation. Douglas R. Campbell. 2022. "Plato's Theory of Reincarnation: Eschatology and Natural Philosophy," ''Review of Metaphysics'' 75 (4): 643–665. See also the discussion in Chad Jorgensen. 2018. ''The Embodied Soul in Plato's Later Thought''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.</ref> One argument concerns the theory of reincarnation's usefulness for explaining why non-human animals exist: they are former humans, being punished for their vices; Plato gives this argument at the end of the ''Timaeus''.<ref>See ''Timaeus'' 90–92.</ref> | |||

| ====Jainism==== | |||

| In ], particular reference is given to how ] (gods) also reincarnate after they die. A Jainist, who accumulates enough good karma, may become a deva; but, this is generally seen as undesirable since devas eventually die and one might then come back as a lesser being. This belief is also commonplace in a number of other schools of Hinduism. | |||

| ====Mystery cults==== | |||

| ===Western religions and traditions=== | |||

| The ], which taught reincarnation, about the sixth century BCE, produced a copious literature.<ref>Linforth, Ivan M. (1941) ''The Arts of Orpheus'' Arno Press, New York, {{OCLC|514515}}</ref><ref>Long, Herbert S. (1948) ''A Study of the doctrine of metempsychosis in Greece, from Pythagoras to Plato'' (Long's 1942 Ph.D. dissertation) Princeton, New Jersey, {{OCLC|1472399}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Long |first1=Herbert S. |title=Plato's Doctrine of Metempsychosis and Its Source |journal=The Classical Weekly |date=1948 |volume=41 |issue=10 |pages=149–155 |id={{ProQuest|1296280468}} |doi=10.2307/4342414 |jstor=4342414 }}</ref> ], its legendary founder, is said to have taught that the immortal soul aspires to freedom while the body holds it prisoner. The wheel of birth revolves, the soul alternates between freedom and captivity round the wide circle of necessity. Orpheus proclaimed the need of the grace of the gods, ] in particular, and of self-purification until the soul has completed the spiral ascent of destiny to live forever. | |||

| ====Classical Greek philosophy==== | |||

| Some ] philosophers believed in reincarnation; see for example ]'s ''Phaedo'' and ''The Republic''. ] was probably the first Greek philosopher to advance the idea. | |||

| An association between ] and reincarnation was routinely accepted throughout antiquity, as Pythagoras also taught about reincarnation. However, unlike the Orphics, who considered metempsychosis a cycle of grief that could be escaped by attaining liberation from it, Pythagoras seems to postulate an eternal, neutral reincarnation where subsequent lives would not be conditioned by any action done in the previous.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans|author=Leonid Zhmud|publisher=OUP Oxford|year=2012|isbn=978-0-19-928931-8|pages=232–233}}</ref> | |||

| :Main article: ] | |||

| ==== |

====Later authors==== | ||

| In later Greek literature the doctrine is mentioned in a fragment of ]<ref>Menander, ''The Inspired Woman''</ref> and satirized by ].<ref>Lucian, ''Gallus'', 18 et seq.</ref> In ] literature it is found as early as ],<ref>Poesch, Jessie (1962) "Ennius and Basinio of Parma" '']'' 25(1/2):116–118 .</ref> who, in a lost passage of his ''Annals'', told how he had seen ] in a dream, who had assured him that the same soul which had animated both the poets had once belonged to a peacock. ] in his satires (vi. 9) laughs at this; it is referred to also by ]<ref>Lucretius, (i. 124)</ref> and ].<ref>Horace, ''Epistles'', II. i. 52</ref> | |||

| The notion of reincarnation is not openly mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. The classical rabbinic works (], ] and ]) also are silent on this topic, as are the writings of the ] and many of the ]. | |||

| ] works the idea into his account of the Underworld in the sixth book of the '']''.<ref>Virgil, ''The Aeneid'', vv. 724 et seq.</ref> It persists down to the late classic thinkers, ] and the other ]s. In the ], a Graeco-Egyptian series of writings on cosmology and spirituality attributed to ]/], the doctrine of reincarnation is central. | |||

| A classic work of the ], '']'' ("Gate of Reincarnations") of Arizal or '']'' (1534-1572 AD/CE), describes complex laws of reincarnation '']'' and impregnation '']'' of 5 different parts of the soul. Within it one can find what its author considered to be references of reincarnation in the Hebrew Bible (the ]). | |||

| ===Celtic paganism=== | |||

| The concept was elucidated in an influential mystical work called the '']'' (Illumination) (claimed to be one of the most ancient books of Jewish mysticism) which is believed to have been composed by the first century mystic Nehunia ben haKana, and gained widespread recognition around 1150. After the publication of the '']'' in the late 13th century, the idea of reincarnation began to spread to most of the general Jewish community. | |||

| In the first century BCE ] wrote: | |||

| {{bquote|The Pythagorean doctrine prevails among the ]' teaching that the souls of men are immortal, and that after a fixed number of years they will enter into another body.}} | |||

| While ancient Greek philosophers like ] and ] attempted to prove the existence of reincarnation through philosophical proofs, Jewish mystics who accepted this idea did not. Rather, they offered explanations of why reincarnation would solve otherwise intractable problems of ] (how to reconcile the existence of evil with the premise of a good God.) | |||

| ] recorded that the ] of Gaul, Britain and Ireland had metempsychosis as one of their core doctrines:<ref>Julius Caesar, "De Bello Gallico", VI</ref> | |||

| Some well-known Rabbis who accepted the idea of reincarnation include the founder of ], the ], Levi ibn Habib (the Ralbah), ] (the Ramban), Rabbenu ], Rabbi Shelomoh Alkabez and Rabbi ]. | |||

| The argument made was that even the most righteous of Jews sometimes would suffer or be murdered unjustly. Further, children would sometimes suffer or be murdered, yet they were obviously too young for them to have committed sins that God would presumably punish them for. | |||

| Jewish supporters of reincarnation said that this idea would remove the theodicy: Good people were not suffering; rather, they were reincarnations of people who had sinned in previous lifetimes. Therefore any suffering which was observed could be assumed to be from a just God. Yitzchak Blua writes "Unlike some other areas of philosophy where the philosophic battleground revolves around the truth or falsehood of a given assertion, the '']'' debate at points focuses on the psychological needs of the people." (p.6) | |||

| {{bquote|The principal point of their doctrine is that the soul does not die and that after death it passes from one body into another... the main object of all education is, in their opinion, to imbue their scholars with a firm belief in the indestructibility of the human soul, which, according to their belief, merely passes at death from one tenement to another; for by such doctrine alone, they say, which robs death of all its terrors, can the highest form of human courage be developed.}} | |||

| ]'s collection of ''Legend of the Baal-Shem'' (''Die Chassidischen Bücher'') includes several of the Baal Shem Tov's stories that explicitly discuss concrete cases of reincarnating souls. | |||

| ] also recorded the Gaul belief that human souls were immortal, and that after a prescribed number of years they would commence upon a new life in another body. He added that Gauls had the custom of casting letters to their deceased upon the funeral pyres, through which the dead would be able to read them.<ref>{{cite book|author=]|title=Caesar's Conquest of Gaul: An Historical Narrative|date=1903|publisher=|isbn=|page=}}</ref> ] also recounted they had the custom of lending sums of money to each other which would be repayable in the next world.<ref>{{cite book |last=Kendrick |first=T.D. |date=2003 |orig-date=1927 |title=Druids and Druidism |publisher=Dover |isbn=0-486-42719-6 |page=106}}</ref> This was mentioned by ], who also recorded Gauls buried or burnt with them things they would need in a next life, to the point some would jump into the funeral piles of their relatives in order to cohabit in the new life with them.{{Sfn|Kendrick|2003|p=108}} | |||

| Among well known Rabbis who rejected the idea of reincarnation are the ](סעדיה הגאון), ], Yedayah Bedershi (early 14th century), ], ] and ]. | |||

| Saadia Gaon, in ], concludes Section vi with a refutation of the doctrine of metempsychosis (reincarnation). While refuting reincarnation, Saadia Gaon states that Jews who hold to reincarnation have adopted non-Jewish beliefs. Crescas writes that if reincarnation was real, people should remember details of their previous lives. Bedershi offers three reasons why the entire concept is dangerous: | |||

| #There is no reason for people to try and do good in this life, if they fear that they will nonetheless be punished for some unknown sin committed in a past life. | |||

| #Some people may assume that they did not sin in their past life, and so can coast on their success; thus there is no need to try hard to live a good life. In Bedershi's view, the only psychologically tenable worldview for a healthy life is to deal with the here-and-now. | |||

| #The idea presents a conundrum for those who believe that at the end of days, God will resurrect the souls and physical bodies of the dead. If a person has lived multiple lives, which body will God resurrect? | |||

| ] believed the Gauls had been taught the doctrine of reincarnation by a slave of ] named ]. Conversely, ] believed Pythagoras himself had learned it from the Celts and not the opposite, claiming he had been taught by ] Gauls, ] priests and ].{{Sfn|Kendrick|2003|p=105}}<ref name=Lopez>{{cite book|author=Robin Melrose|title=The Druids and King Arthur: A New View of Early Britain|date=2014|publisher=McFarland|isbn=978-07-864600-5-2}}</ref> However, author ] rejected a real connection between Pythagoras and the Celtic idea reincarnation, noting their beliefs to have substantial differences, and any contact to be historically unlikely.{{Sfn|Kendrick|2003|p=108}} Nonetheless, he proposed the possibility of an ancient common source, also related to the ] and ] systems of belief.{{Sfn|Kendrick|2003|p=109}} | |||

| Joseph Albo writes that in theory the idea of gilgulim is compatible with Jewish theology. However, Albo argues that there is a purpose for a soul to enter the body, creating a being with free-will. However, a return of the soul to another body, again and again, has no point. Leon De Modena thinks that the idea of reincarnation make a mockery of God's plans for humans; why does God need to send the soul back over and over? If God requires an individual to achieve some perfection or atone for some sin, then God can just extend that person's life until they have time to do what is necessary. De Modena's second argument against reincarnation is that the entire concept is absent from the entire Bible and corpus of classical rabbinic literature. | |||

| ===Germanic paganism=== | |||

| The idea of reincarnation, called '']'', became popular in folk belief, and is found in much ] literature among ] Jews. Among a few kabbalists, it was posited that some human souls could end up being reincarnated into non-human bodies. These ideas can be found in a number of Kabbalistic works from the 1200s, and also among many mystics in the late 1500s. A distinction was made, however, between actual Transmigration and this form of reincarnation; the non-human subject had its own soul already, the human soul simply 'rode along with' the rock, or tree, or giraffe waiting to be 'elevated,' that is, to be raised to a higher level and to gradually approach the level of human again. The cow eats the grass, elevating the soul within it, the soul rides with the cow a while until a person eats the cow, and then the soul is elevated to the max'. Rabbi Chaim Vidal, when asked how he came to be the foremost disciple and sole transmitter of the teachings of his teacher, the great Issac Luria, credits, not study or mitzvot, but his diligence in blessing his food: "For this way I elevate the souls therein. These souls then become my witnesses in the Heavenly Realm, and empower me to receive even greater revelations." | |||

| {{Main|Rebirth in Germanic paganism}} | |||

| Surviving texts indicate that there was a belief in ]. Examples include figures from ] and ]s, potentially by way of a process of naming and/or through the family line. Scholars have discussed the implications of these attestations and proposed theories regarding belief in reincarnation among the ] prior to ] and potentially to some extent in ] thereafter. | |||

| ===Judaism=== | |||

| "Over time however, the philosophical teaching limiting reincarnation to human bodies emerged as the dominant view. Nonetheless, the idea that one can reborn as an animal was never completely eliminated from Jewish thought, and appears centuries later in the Eastern European folk tradition". | |||

| The belief in reincarnation developed among Jewish mystics in the medieval world, among whom differing explanations were given of the afterlife, although with a universal belief in an immortal soul.<ref>''Essential Judaism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals'', By George Robinson, Simon and Schuster 2008, p. 193</ref> It was explicitly rejected by ].<ref>''The Book of Beliefs and Opinions'', chap. VIII</ref> Today, reincarnation is an ] belief within many streams of modern Judaism. ] teaches a belief in '']'', transmigration of souls, and hence the belief in reincarnation is universal in ], which regards the Kabbalah as sacred and authoritative, and is also sometimes held as an esoteric belief within other strains of ]. In ], the ], first published in the 13th century, discusses reincarnation at length, especially in the ] portion "Balak." The most comprehensive ] work on reincarnation, '']'',<ref>"Mind in the Balance: Meditation in Science, Buddhism, and Christianity", p. 104, by B. Alan Wallace</ref><ref>"Between Worlds: Dybbuks, Exorcists, and Early Modern Judaism", p. 190, by ]</ref> was written by ], based on the teachings of his mentor, the 16th-century kabbalist ], who was said to know the past lives of each person through his ] abilities. The 18th-century Lithuanian master scholar and kabbalist, Elijah of Vilna, known as the ], authored a commentary on the biblical ] as an allegory of reincarnation. | |||

| The practice of conversion to Judaism is sometimes understood within Orthodox Judaism in terms of reincarnation. According to this school of thought in Judaism, when non-Jews are drawn to Judaism, it is because they had been Jews in a former life. Such souls may "wander among nations" through multiple lives, until they find their way back to Judaism, including through finding themselves born in a gentile family with a "lost" Jewish ancestor.<ref>''Jewish Tales of Reincarnation'', By Yonasson Gershom, Yonasson Gershom, Jason Aronson, Incorporated, 31 January 2000</ref> | |||

| While many Jews today do not believe in reincarnation, the belief is common amongst ] Jews, particularly amongst ]; some Hasidic ]im (prayerbooks) have a prayer asking for forgiveness for one's sins that one may have committed in this '']'' or a previous one. | |||

| There is an extensive literature of Jewish folk and traditional stories that refer to reincarnation.<ref>Yonasson Gershom (1999), ''Jewish Tales of Reincarnation''. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson. {{ISBN|0-7657-6083-5}}</ref> | |||

| The greatest number of ] who reject the concept of reincarnation is to be found among students of ] (the ]), among ], and among ''Gaonists.'' One can also find ] who deny the compatibility of reincarnation with Judaism among segments of ]. | |||

| ===Christianity=== | |||

| '''Reincarnationism''' or '''biblical reincarnation''' is the belief that certain people are or can be ] of ], such as ] and the ].<ref name="cinemaseekers1">{{Cite web |url=http://www.cinemaseekers.com/Christ/reincarnation.html |title=Biblical Accounts that Suggest Reincarnation |access-date=2023-08-27 |archive-date=2021-06-08 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210608232803/http://www.cinemaseekers.com/christ/reincarnation.html }}</ref> Some Christians believe that certain New Testament figures are reincarnations of Old Testament figures. For example, ] is believed by some to be a reincarnation of the prophet ], and a few take this further by suggesting Jesus was the reincarnation of Elijah's disciple ].<ref name="cinemaseekers1"/><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://yoganandafortheworld.com/who-was-jesus-before-the-last-incarnation-elias-and-elijah-the-second-coming-of-christ/ |title=Who Was Jesus Before the Last Incarnation? |date=9 January 2012 |access-date=2023-09-07}}</ref> Other Christians believe the ] of Jesus would be fulfilled by reincarnation. ], the founder of the ], considered himself to be the fulfillment of Jesus' return. | |||

| The Catholic Church does not believe in reincarnation, which it regards as being incompatible with ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p123a11.htm#1013 |title=CCC – PART 1 SECTION 2 CHAPTER 3 ARTICLE 11 |publisher=Vatican.va |date= |access-date=2012-05-23}}</ref> Nonetheless, the leaders of certain ] in the church have taught that they are reincarnations of Mary – for example, Marie-Paule Giguère of the ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cccb.ca/site/Files/armyofmary.html |title=Army of Mary Doctrinal Note |publisher=Cccb.ca |date= |access-date=2012-05-23 |archive-date=2012-05-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120504170432/http://www.cccb.ca/site/Files/armyofmary.html }}</ref><ref name="vsu">{{Cite web|url=https://wrldrels.org/2016/10/08/army-of-mary/|title=Army of Mary / Community of the Lady of All Peoples – WRSP|access-date=8 October 2023}}</ref> and ] of the former ].<ref>{{cite web|author=Pius X |url=https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_x/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-x_enc_05041906_tribus-circiter_en.html |title=Pius X, Tribus Circiter (05/04/1906) |publisher=Vatican.va |date=1904-09-04 |access-date=2012-05-23}}</ref> The ] excommunicated the Army of Mary for teaching heresy, including reincarnationism.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.cccb.ca/site/images/stories/pdf/decl_excomm_english.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=2012-05-23 |archive-date=2012-05-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120504170442/http://www.cccb.ca/site/images/stories/pdf/decl_excomm_english.pdf }}</ref> | |||

| ====Gnosticism==== | ====Gnosticism==== | ||

| Several ] sects professed reincarnation. The ] and followers of ] believed in it.<ref>Much of this is documented in R.E. Slater's book ''Paradise Reconsidered.''</ref> The followers of ] of ], a sect of the second century deemed heretical by the Catholic Church, drew upon ] ], to which Bardaisan's son Harmonius, educated in Athens, added Greek ideas including a sort of metempsychosis. Another such teacher was ] (132–? CE/AD), known to us through the criticisms of ] and the work of ] (see also ] and ]). | |||

| Many ] groups believed in reincarnation. For them, reincarnation was a negative concept: ] believed that the material body was evil, and that they would be better off if they could eventually avoid having their 'good' souls reincarnated in 'evil' bodies. | |||

| In the third Christian century ] spread both east and west from ], then within the ], where its founder ] lived about 216–276. Manichaean monasteries existed in Rome in 312 AD. Noting Mani's early travels to the ] and other Buddhist influences in Manichaeism, ]<ref>], ''Religions of the Silk Road'', New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010</ref> attributes Mani's teaching of reincarnation to Buddhist influence. However the inter-relation of Manicheanism, Orphism, Gnosticism and neo-Platonism is far from clear. | |||

| The Gnostic : | |||

| :''1. As Yeshua sat by the west of the temple with his disciples, behold there passed some carrying one that was dead, to burial, and a certain one said to Him, "Master, if a man die, shall he live again?"'' | |||

| :''2. He answered and said, "I am the resurrection and the life, I am the good, the beautiful, the true; if a man believe in me he shall not die, but live eternally. As in Adam all (1997 = are bound to cycles of rebirth) die, so in the Messiah shall all be made alive. Blessed are the dead who die in me, and are made perfect in my image and likeness, for they rest from their labors and their works do follow them. They have overcome evil, and are made pillars in the temple of my God, and they go out no more, for they rest in the eternal."'' | |||

| :''3. "For them that persist in evil there is no rest, but they go out and in, and suffer correction for ages, till they are made perfect. But for them that have done good and attained to perfection, there is endless rest and they go into life everlasting. They rest in the eternal."'' | |||

| :''4. "Over them the repeated death and birth have no power, for them the wheel of the eternal revolves no more, for they have attained to the center, where is eternal rest, and the center of all things is God." '' | |||

| ===Taoism=== | |||

| Note: The text above is not from the original Gospel of the Nazirenes, which now exists only in fragments. Rather, it is the product of "channeling" and of recent origin. | |||

| ] documents from as early as the ] claimed that ] appeared on earth as different persons in different times beginning in the legendary era of ]. The (ca. third century BC) '']'' states: "Birth is not a beginning; death is not an end. There is existence without limitation; there is continuity without a starting-point. Existence without limitation is Space. Continuity without a starting point is Time. There is birth, there is death, there is issuing forth, there is entering in."<ref>{{cite book |url= https://archive.org/details/chuangtzmysticm00chuagoog|title=Chuang Tzŭ: Mystic, Moralist, and Social Reformer (translated by Herbert Allen Giles)|publisher= Bernard Quaritch|year= 1889|page= |author1=Zhuangzi}}</ref>{{Better source needed|date=April 2019}} | |||

| ===European Middle Ages=== | |||

| The texts contains several parallels to the Gospels, which are, though, traditionally interpreted differently in their context: | |||

| Around the 11–12th century in Europe, several reincarnationist movements were persecuted as heresies, through the establishment of the ] in the Latin west. These included the ], Paterene or Albigensian church of western Europe, the ] movement, which arose in Armenia,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11583b.htm |title=Newadvent.org |publisher=Newadvent.org |date=1 February 1911 |access-date=6 December 2011}}</ref> and the ] in ].<ref>Steven Runciman, ''The Medieval Manichee: A Study of the Christian Dualist Heresy'', 1982, {{ISBN|0-521-28926-2}}, Cambridge University Press, ''The Bogomils''</ref> | |||

| :''"I am the resurrection and the life; he who believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and whoever lives and believes in me shall never die. '' John 11:25f RSV | |||

| :''Him who overcomes I will make a pillar in the temple of my God. Never again will he leave it.'' Revelation 3:12 (NIV) | |||

| Christian sects such as the Bogomils and the Cathars, who professed reincarnation and other gnostic beliefs, were referred to as "Manichaean", and are today sometimes described by scholars as "Neo-Manichaean".<ref>For example Dondaine, Antoine. O.P. ''Un traite neo-manicheen du XIIIe siecle: Le Liber de duobus principiis, suivi d'un fragment de rituel Cathare'' (Rome: Institutum Historicum Fratrum Praedicatorum, 1939)</ref> As there is no known Manichaean mythology or terminology in the writings of these groups there has been some dispute among historians as to whether these groups truly were descendants of Manichaeism.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01267e.htm |title=Newadvent.org |publisher=Newadvent.org |date=1 March 1907 |access-date=6 December 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ====Christianity==== | |||

| {{Further|]}} | |||

| ===Renaissance and Early Modern period=== | |||

| Almost all present official Christian denominations reject reincarnation: exceptions include the ], ], and the ]. Doctrines of reincarnation were known to the early Church (before the 6th century A.D.), and believers in reincarnation claim that these doctrines were embraced or at least tolerated within the Church at that time. Two Church Fathers, ] and ] are frequently cited as supporting this. However, this cannot be confirmed from the existent writings of Origen. He was cognizant of the concept of reincarnation (metensomatosis "re-embodiment" in his words) from Greek philosophy, but he repeatedly states that this concept is no part of the Christian teaching or scripture. He writes in his Comment on the Gospel of Matthew: "In this place it does not appear to me that by Elijah the soul is spoken of, lest I fall into the doctrine of transmigration, which is foreign to the Church of God, and not handed down by the apostles, nor anywhere set forth in the scriptures" (ibid., 13:1:46–53). | |||

| While reincarnation has been a matter of faith in some communities from an early date it has also frequently been argued for on principle, as Plato does when he argues that the number of souls must be finite because souls are indestructible,<ref>"the souls must always be the same, for if none be destroyed they will not diminish in number". Republic X, 611. The Republic of Plato By Plato, Benjamin Jowett Edition: 3 Published by Clarendon press, 1888.</ref> ] held a similar view.<ref>In a letter to his friend ] written 23 May 1785: {{cite journal|jstor = 25057231|title = Death Effects: Revisiting the Conceit of Franklin's "Memoir"|journal = Early American Literature|volume = 36|issue = 2|pages = 201–234|last1 = Kennedy|first1 = Jennifer T.|year = 2001|doi = 10.1353/eal.2001.0016|s2cid = 161799223}}</ref> Sometimes such convictions, as in Socrates' case, arise from a more general personal faith, at other times from anecdotal evidence such as Plato makes Socrates offer in the '']''. | |||

| During the ] translations of Plato, the ] and other works fostered new European interest in reincarnation. ]<ref>Marsilio Ficino, ''Platonic Theology'', 17.3–4</ref> argued that Plato's references to reincarnation were intended allegorically, Shakespeare alluded to the doctrine of reincarnation<ref>"Again, Rosalind in "As You Like It" (Act III., Scene 2), says: ''I was never so be-rhimed that I can remember since Pythagoras's time, when I was an Irish rat"''—alluding to the doctrine of the transmigration of souls." William H. Grattan Flood, quoted at {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090421065024/http://www.libraryireland.com/IrishMusic/XVII-2.php |date=2009-04-21 }}</ref> but ] was burned at the stake by authorities after being found guilty of heresy by the ] for his teachings.<ref>Boulting, 1914. pp. 163–164</ref> But the Greek philosophical works remained available and, particularly in north Europe, were discussed by groups such as the ]. ] believed that we leave the physical world once, but then go through several lives in the spiritual world—a kind of hybrid of Christian tradition and the popular view of reincarnation.<ref>{{cite web |title=Swedenborg and Life Recap: Do We Reincarnate? 3/6/2017 |date=10 March 2017 |url=https://swedenborg.com/recap-do-we-reincarnate/ |access-date=24 October 2019 |publisher=Swedenborg Foundation}}</ref> | |||

| Some reincarnation followers state that Origen's writings have only come down to us heavily edited 'to conform to Church doctrine', and some Origen's writings were later declared heretical by the Church (though Origen himself was not). | |||

| ===19th to 20th centuries=== | |||

| They also state that before the Church expurged what it considered his heretical ideas from editions of his works, other quotes of Origen were also recorded by early Church fathers that make it clear that he did indeed teach reincarnation. A discussion of Origen's relationship to reincarnation, including many more quotes, can be found at . | |||

| By the 19th century the philosophers ]<ref>Schopenhauer, A: "Parerga und Paralipomena" (Eduard Grisebach edition), On Religion, Section 177</ref> and ]<ref>Nietzsche and the Doctrine of Metempsychosis, in J. Urpeth & J. Lippitt, ''Nietzsche and the Divine'', Manchester: Clinamen, 2000</ref> could access the Indian scriptures for discussion of the doctrine of reincarnation, which recommended itself to the ] ], ] and ] and was adapted by ] into ''Christian Metempsychosis''.<ref name="shirleymaclaine.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.shirleymaclaine.com/articles/reincarnation/article-318 |title=Shirleymaclaine.com |publisher=Shirleymaclaine.com |access-date=6 December 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111106160539/http://www.shirleymaclaine.com/articles/reincarnation/article-318 |archive-date=6 November 2011 }}</ref> | |||