| Revision as of 23:22, 24 November 2006 editCoso~enwiki (talk | contribs)45 editsm →The 1980s through the present← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:00, 16 January 2025 edit undoÆ's old account wasn't working (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,258 editsm typographical correctionTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Cinematic term used to describe stylized feature film crime dramas}} | |||

| {{for|the Carly Simon album|Film Noir (album)}} | |||

| {{redirect|Film Noir|the Carly Simon album|Film Noir (album){{!}}''Film Noir'' (album)}} | |||

| ]'' (1955) demonstrates the visual style of film noir at its most extreme. ], the film's ], created many of the iconic images of film noir.]] | |||

| {{use mdy dates|date=October 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox film movement | |||

| | name = Film noir | |||

| | image = BigComboTrailer.jpg | |||

| | caption = Two silhouetted figures in '']'' (1955). The film's ], ], is sometimes credited as the creator of many of film noir's stylized images. | |||

| | yearsactive = ]: 1940s and 1950s; earlier films are often referred to as proto-noirs and later films as ]s | |||

| | country = United States | |||

| | majorfigures =] <br> ] <br> ] <br> ] | |||

| | influences = *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| | influenced = *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| | origins = early ] | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Film noir''' is a |

'''Film noir''' ({{IPAc-en|n|w|ɑːr}}; {{IPA|fr|film nwaʁ|lang}}) is a cinematic term used primarily to describe stylized ] ], particularly those that emphasize ] attitudes and motivations. The 1940s and 1950s are generally regarded as the "classic period" of American film noir. Film noir of this era is associated with a ], ] visual style that has roots in ]tography. Many of the prototypical stories and attitudes expressed in classic noir derive from the ] school of ] that emerged in the United States during the ], known as ].<ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.learner.org/series/american-cinema/film-noir/|publisher = Annenberg Learner|work = American Cinema|title = Film Noir|access-date = 2021-04-18|archive-date = 2021-04-18|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210418071813/https://www.learner.org/series/american-cinema/film-noir/|url-status = live}}</ref> | ||

| The term ''film noir'' |

The term ''film noir'', French for "black film" (literal) or "dark film" (closer meaning),<ref>See, e.g., Biesen (2005), p. 1; Hirsch (2001), p. 9; Lyons (2001), p. 2; Silver and Ward (1992), p. 1; Schatz (1981), p. 112. Outside the field of film noir scholarship, "dark film" is also offered on occasion; see, e.g., Block, Bruce A., ''The Visual Story: Seeing the Structure of Film, TV, and New Media'' (2001), p. 94; Klarer, Mario, ''An Introduction to Literary Studies'' (1999), p. 59.</ref> was first applied to ]s by French critic ] in 1946, but was unrecognized by most American film industry professionals of that era.<ref>Naremore (2008), pp. 4, 15–16, 18, 41; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 4–5, 22, 255.</ref> Frank is believed to have been inspired by the French literary publishing imprint ], founded in 1945. | ||

| Cinema historians and critics defined the category retrospectively. Before the notion was widely adopted in the 1970s, many of the classic films noir{{Ref label|A|a|none}} were referred to as "]s". Whether film noir qualifies as a distinct ] or whether it should be considered a filmmaking style is a matter of ongoing and heavy debate among film scholars. | |||

| ==Noir—What is it?== | |||

| "We'd be oversimplifying things in calling film noir ], strange, erotic, ambivalent, and cruel...."<ref>Borde and Chaumeton (2002), p. 2.</ref> This is the first of many attempts to define film noir made by the French critics Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton in their 1955 book ''Panorama du film noir américain 1941–1953'' (''A Panorama of American Film Noir''), the original and seminal extended treatment of the subject. They take pains to point out that not each film noir embodies all five attributes in equal measure—this one is more dreamlike, while this other is particularly brutal. The authors' caveats and repeated efforts at alternative definition have proved telling about noir's reliability as a label: in the five decades since, no definition has achieved anything close to general acceptance. The authors of most substantial considerations of film noir still find it necessary to add on to what are now innumerable attempts at definition. As Borde and Chaumeton suggest, however, the field of noir is very diverse and any generalization about it risks veering into oversimplification. | |||

| Film noir encompasses a range of plots; common archetypical protagonists include a private investigator ('']''), a ] ('']''), an aging boxer ('']''), a hapless ] ('']''), a law-abiding citizen lured into a life of crime ('']''), a ] ('']'') or simply a victim of circumstance ('']''). Although film noir was originally associated with American productions, the term has been used to describe films from around the world. Many films released from the 1960s onward share attributes with films noir of the classical period, and often treat its conventions ]. Latter-day works are typically referred to as ]. The clichés of film noir have inspired parody since the mid-1940s.<ref>{{cite web|first = Nandia|last = Foteini Vlachou|url = https://iknowwhereimgoing.wordpress.com/2016/09/06/parody-and-the-noir/|title = Parody and the noir|website = I Know Where I'm Going|date = 6 September 2016|access-date = 19 November 2020|archive-date = 27 November 2020|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20201127201850/https://iknowwhereimgoing.wordpress.com/2016/09/06/parody-and-the-noir/|url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| Film noirs embrace a variety of ]s, from the gangster film to the ] to the so-called ], and evidence a variety of visual approaches, from meat-and-potatoes Hollywood mainstream to outré. While many critics refer to film noir as a genre itself, others argue that it can be no such thing. Though noir is often associated with an urban setting, for example, many classic noirs take place largely in small towns, suburbia, rural areas, or on the open road, so setting can not be its genre determinant, as with the ]. Similarly, while the ] and the ] are character types conventionally identified with noir, the majority of film noirs feature neither, so there is no character basis for genre designation as with the gangster film. Nor does it rely on anything as evident as the monstrous or supernatural elements of the ], the speculative leaps of the ], or the song-and-dance routines of the ]. | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| A more analogous case is that of the ], widely accepted by film historians as constituting a "genre"—the screwball is defined not by a fundamental attribute, but by a general disposition and a group of elements, some (but rarely and perhaps never all) of which are found in each of the genre's films.<ref>See Dancyger and Rush (2002), p. 68, for a detailed comparison of screwball comedy and film noir.</ref> However, because of the diversity of noir (much greater than that of the screwball comedy), certain scholars in the field, such as film historian Thomas Schatz, treat it as not a genre but a "style." Alain Silver, the most widely published American critic specializing in film noir studies, refers to it as a "cycle" and a "phenomenon," even as he argues that it has—like certain genres—a consistent set of visual and thematic codes. Other critics treat film noir as a "mood," a "movement," or a "series," or simply address a chosen set of movies from the "period." There is no consensus on the matter. | |||

| ]'' (1946), directed by ]]] | |||

| The question of what defines film noir and what sort of category it is, provokes continuing debate.<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 3.</ref> "We'd be oversimplifying things in calling film noir ], strange, erotic, ambivalent, and cruel ..."—this set of attributes constitutes the first of many attempts to define film noir made by French critics {{interlanguage link|Raymond Borde|fr}} and Étienne Chaumeton in their 1955 book ''Panorama du film noir américain 1941–1953'' (''A Panorama of American Film Noir''), the original and seminal extended treatment of the subject. | |||

| <ref>Borde and Chaumeton (2002), p. 2.</ref> They emphasize that not every noir film embodies all five attributes in equal measure—one might be more dreamlike; another, particularly brutal.<ref>Borde and Chaumeton (2002), pp. 2–3.</ref> The authors' caveats and repeated efforts at alternative definition have been echoed in subsequent scholarship, but in the words of cinema historian Mark Bould, film noir remains an "elusive phenomenon."<ref>Bould (2005), p. 13.</ref> | |||

| ==The prehistory of noir== | |||

| Film noir has sources not only in cinema but other artistic mediums as well. The ] schemes commonly linked with the classic mode are in the tradition of ] and ], techniques using high contrasts of light and dark developed by 15th- and 16th-century painters associated with ] and the ]. Film noir's aesthetics are deeply influenced by ], a cinematic movement of the 1910s and 1920s closely related to contemporaneous developments in theater, photography, painting, scultpture, and architecture. The opportunities offered by the booming Hollywood film industry and, later, the threat of growing ] power led to the emigration of many important film artists working in Germany who had either been directly involved in the Expressionist movement or studied with its practitioners. ] such as ], ], and ] brought dramatic lighting techniques and a psychologically expressive approach to ] with them to Hollywood, where they would make some of the most famous of classic noirs. Lang's 1931 masterwork, the German '']'', is among the first major crime films of the ] to join a characteristically noirish visual style with a noir-type plot, one in which the ] is a criminal (as are his most successful pursuers). ''M'' was also the occasion for the first star performance by ], who would go on to act in several formative American noirs of the classic era. | |||

| Though film noir is often identified with a visual style that emphasizes ] and ],<ref>See, e.g., Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 4; Bould (2005), p. 12; Place and Peterson (1974).</ref> films commonly identified as noir evidence a variety of visual approaches, including ones that fit comfortably within the Hollywood mainstream.<ref>See, e.g., Naremore (2008), p. 167–68; Irwin (2006), p. 210.</ref> Film noir similarly embraces a variety of genres, from the ] to the ] to the ] to the ]—any example of which from the 1940s and 1950s, now seen as noir's classical era, was likely to be described as a melodrama at the time.<ref>Neale (2000), p. 166; Vernet (1993), p. 2; Naremore (2008), pp. 17, 122, 124, 140; Bould (2005), p. 19.</ref> | |||

| ], ], complete with noir-regulation cigarette, in a publicity shot for ]'s mordant melodrama '']'' (''The Blue Angel''; 1930).]] | |||

| {{Quote box | |||

| By 1931, Curtiz had already been in Hollywood for half a decade, making as many as six films a year. Movies of his such as ''20,000 Years in Sing Sing'' (1932) and ''Private Detective 62'' (1933) are among the early Hollywood sound films arguably classifiable as noir. Giving Expressionist-affiliated moviemakers particularly free stylistic rein were ] horror pictures such as '']'' (1931), '']'' (1932)—the former ] and the latter directed by the Berlin-trained ]—and '']'' (1934), directed by Austrian émigré ]; the Universal horror that comes closest to noir, both in story and sensibility, however, is '']'' (1933), directed by Englishman ] and shot by American ] | |||

| | quote = It is night, always. The hero enters a labyrinth on a quest. He is alone and off balance. He may be desperate, in flight, or coldly calculating, imagining he is the pursuer rather than the pursued. | |||

| A woman invariably joins him at a critical juncture, when he is most vulnerable. eventual betrayal of him (or herself) is as ambiguous as her feelings about him. | |||

| The Vienna-born but largely American-raised ] was directing in Hollywood at the same time. Films of his such as '']'' (1932) and '']'' (1935), with their hothouse eroticism and baroque visual style, specifically anticipate central elements of classic noir. The commercial and critical success of Sternberg's silent '']'' in 1927 was largely responsible for spurring a trend of Hollywood gangster films. Popular movies in the genre such as '']'' (1931), '']'' (1931), and '']'' (1932) demonstrated that there was an audience for crime dramas with morally reprehensible protagonists. | |||

| | author = ] | |||

| | source = ''Somewhere in the Night'' (1997)<ref>{{Cite book |last=Christopher |first=Nicholas |title=Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City |date=1997 |isbn=0-684-82803-0 |publisher=] |location=New York, NY |oclc=36330881|page=7}}</ref> | |||

| | align = left | |||

| An important, and possibly influential, cinematic antecedent to classic noir was 1930s French ], with its romantic, ] attitude and celebration of doomed heroes; an acknowledged influence on certain trends in noir was 1940s ], with its emphasis on quasi-documentary authenticity. (The ] drama '']'' presciently combines these sensibilities.) Director ] of '']'' (1948) pointed to the neorealists as inspiring his use of on-location photography with nonprofessional extras; three years earlier, '']'', directed by ], demonstrated the parallel influence of the cinematic newsreel. A few movies now considered noir strove to depict comparatively ordinary protagonists with unspectacular lives in a manner occasionally evocative of neorealism—the most famous example is '']'' (1945), directed by ], yet another Vienna-born, Berlin-trained American ]. (In turn, one of the primary influences on neorealism was the 1930 German film ''Menschen am Sonntag'', codirected and cowritten by Siodmak, cowritten by Wilder, and codirected and produced by Ulmer.) Among those movies not themselves considered film noirs, perhaps none had a greater effect on the development of the genre than America's own '']'' (1941), the landmark motion picture directed by ]. Its Sternbergian visual intricacy and complex, ]-driven narrative structure are echoed in dozens of classic film noirs. | |||

| | width = 25% | |||

| }}While many critics refer to film noir as a genre itself, others argue that it can be no such thing.<ref>For overview of debate, see, e.g., Bould (2005), pp. 13–23; Telotte (1989), pp. 9–10. For description of noir as a genre, see, e.g., Bould (2005), p. 2; Hirsch (2001), pp. 71–72; Tuska (1984), p. xxiii. For the opposing viewpoint, see, e.g., Neale (2000), p. 164; Ottoson (1981), p. 2; Schrader (1972); Durgnat (1970).</ref> Foster Hirsch defines a genre as determined by "conventions of narrative structure, characterization, theme, and visual design." Hirsch, as one who has taken the position that film noir is a genre, argues that these elements are present "in abundance." Hirsch notes that there are unifying features of tone, visual style and narrative sufficient to classify noir as a distinct genre.<ref>{{cite book | last=Conrad |first=Mark T. |title=The Philosophy of Film Noir| publisher=University Press of Kentucky |date=2006}}</ref> | |||

| Others argue that film noir is not a genre. It is often associated with an urban setting, but many classic noirs take place in small towns, suburbia, rural areas, or on the open road; setting is not a determinant, as with the ]. Similarly, while the ] and the ] are ] types conventionally identified with noir, the majority of films in the genre feature neither. Nor does film noir rely on anything as evident as the monstrous or supernatural elements of the ], the speculative leaps of the ], or the song-and-dance routines of the ].<ref>Ottoson (1981), pp. 2–3.</ref> | |||

| ==="The Simple Art of Murder"=== | |||

| The primary literary influence on film noir was the ] school of American ] and ], led in its early years by such writers as ] (whose first novel, '']'', was published in 1929) and ] (whose '']'' appeared five years later), and popularized in ]s such as '']''. The classic film noirs '']'' (1941) and '']'' (1942) were based on novels by Hammett; Cain's novels provided the basis for '']'' (1944), '']'' (1945), '']'' (1946), and '']'' (1956; adapted from ''Love's Lovely Counterfeit''). A decade before the classic era, a story of Hammett's was the source for the gangster melodrama ''City Streets'' (1931), directed by ] and photographed by ], who worked regularly with Sternberg. Wedding a style and story both with many noir characteristics, released the month before Lang's ''M'', ''City Streets'' has a claim to being the first major film noir. | |||

| An analogous case is that of the ], widely accepted by film historians as constituting a "genre": screwball is defined not by a fundamental attribute, but by a general disposition and a group of elements, some—but rarely and perhaps never all—of which are found in each of the genre's films.<ref>See Dancyger and Rush (2002), p. 68, for a detailed comparison of screwball comedy and film noir.</ref> Because of the diversity of noir (much greater than that of the screwball comedy), certain scholars in the field, such as film historian Thomas Schatz, treat it as not a genre but a "style". | |||

| ], who debuted as a novelist with '']'' in 1939, soon became the most famous author of the hardboiled school. Not only were Chandler's novels turned into major noirs—'']'' (1944; adapted from '']''), '']'' (1946), and '']'' (1947)—he was an important ] in the genre as well, producing the scripts for ''Double Indemnity'', '']'' (1946), and '']'' (1951). Where Chandler, like Hammett, centered most of his novels and stories on the character of the private eye, Cain featured less heroic protagonists and focused more on psychological exposition than on crime solving; the Cain approach has come to be identified with a subset of the hardboiled genre dubbed "]." For much of the 1940s, one of the most prolific and successful authors of this often downbeat brand of suspense tale was ] (sometimes using the pseudonyms George Hopley or William Irish). No writer's published work provided the basis for more film noirs of the classic period than Woolrich's: thirteen in all, including '']'' (1946), '']'' (1946), and '']'' (1947). | |||

| <ref>Schatz (1981), pp. 111–15.</ref> ], the most widely published American critic specializing in film noir studies, refers to film noir as a "cycle"<ref>Silver (1996), pp. 4, 6 passim. See also Bould (2005), pp. 3, 4; Hirsch (2001), p. 11.</ref> and a "phenomenon",<ref>Silver (1996), pp. 3, 6 passim. See also Place and Peterson (1974).</ref> even as he argues that it has—like certain genres—a consistent set of visual and thematic codes.<ref>Silver (1996), pp. 7–10.</ref> Screenwriter ] labels both film noir and screwball comedy a "pathway" in his screenwriters taxonomy; explaining that a pathway has two parts: 1) the way the audience connects with the protagonist and 2) the trajectory the audience expects the story to follow.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Williams|first=Eric R.|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/993983488|title=The screenwriters taxonomy : a roadmap to collaborative storytelling|publisher=Routledge Studies in Media Theory and Practice|year=2017|isbn=978-1-315-10864-3|location=New York, NY|oclc=993983488|access-date=2020-06-07|archive-date=2020-06-15|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200615120622/https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/993983488|url-status=live}}</ref> Other critics treat film noir as a "mood,"<ref>See, e.g., Jones (2009).</ref> a "series",<ref>See, e.g., Borde and Chaumeton (2002), pp. 1–7 passim.</ref> or simply a chosen set of films they regard as belonging to the noir "canon."<ref>See, e.g., Telotte (1989), pp. 10–11, 15 passim.</ref> There is no consensus on the matter.<ref>For survey of the lexical variety, see Naremore (2008), pp. 9, 311–12 n. 1.</ref> | |||

| A crucial literary source for film noir, now often overlooked, was ], whose first novel to be published was ''Little Caesar'', in 1929. It would be turned into the hit for ] in 1931; the following year, Burnett was hired to write dialogue for ''Scarface'', while ''Beast of the City'' was adapted from one of his stories. Some critics regard these latter two movies as film noirs, despite their early date. Burnett's characteristic narrative approach fell somewhere between that of the quintessential hardboiled writers and their noir fiction compatriots—his protagonists were often heroic in their way, a way just happening to be that of the gangster. During the classic era, his work, either as author or screenwriter, was the basis for seven movies now widely regarded as film noirs, including three of the most famous: '']'' (1941), '']'' (1942), and '']'' (1950). | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| ==The classic period== | |||

| ]'' (1947) features many of the genre's hallmarks: a cynical private detective as the protagonist, a sexy ], multiple ]s with ] narration, dramatic ] photography, and a ] mood leavened with provocative banter. The film stars ], one of the foremost male icons of film noir.]] | |||

| ===Cinematic sources=== | |||

| The 1940s and 1950s are generally regarded as the "classic period" of American film noir. The movie most commonly cited as the first "true" film noir is '']'' (1940). While ''City Streets'' and other pre-WWII crime melodramas such as '']'' (1936) and '']'' (1937), both directed by Fritz Lang, are considered full-fledged noir by some critics, most categorize them as "proto-noir" or in similar terms. Many claim that there is a significant distinction between the noirs of the classic period's two decades—other than the relative disappearance of the private eye as a lead character there is no consensus on how that distinction manifests, but it often comes down to a view that the noirs of the 1950s tend to be more "extreme" in one way or another. | |||

| ], an actress frequently called upon to play a ].]] | |||

| The aesthetics of film noir were influenced by ], an artistic movement of the 1910s and 1920s that involved theater, music, photography, painting, sculpture and architecture, as well as cinema. The opportunities offered by the booming Hollywood film industry and then the threat of ]sm led to the emigration of many film artists working in Germany who had been involved in the Expressionist movement or studied with its practitioners.<ref>Bould (2005), pp. 24–33.</ref> '']'' (1931), shot only a few years before director ]'s departure from Germany, is among the first crime films of the ] to join a characteristically noirish visual style with a noir-type plot, in which the protagonist is a criminal (as are his most successful pursuers). Directors such as Lang, ], ] and ] brought a dramatically shadowed lighting style and a psychologically expressive approach to visual composition ('']'') with them to Hollywood, where they made some of the most famous classic noirs.<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 9–11.</ref> | |||

| Orson Welles's '']'' (1958) is frequently cited as the last noir of the classic period. Some scholars believe film noir never really ended, but continued to transform even as the characteristic noir visual style began to seem dated and changing production conditions led Hollywood in different directions—in this view, later films in the noir tradition are seen as part of a continuity with classic noir. A majority of critics, however, regard comparable movies made outside the classic era to be something other than genuine film noirs. They regard true film noir as belonging to a temporally and geographically limited cycle or period, treating subsequent films that evoke the classics as fundamentally different due to general shifts in moviemaking style and latter-day awareness of noir as a historical source for ]. | |||

| By 1931, Curtiz had already been in Hollywood for half a decade, making as many as six films a year. Movies of his such as '']'' (1932) and '']'' (1933) are among the early Hollywood sound films arguably classifiable as noir—scholar Marc Vernet offers the latter as evidence that dating the initiation of film noir to 1940 or any other year is "arbitrary".<ref>Vernet (1993), p. 15.</ref> Expressionism-orientated filmmakers had free stylistic rein in ] horror pictures such as '']'' (1931), '']'' (1932)—the former ] and the latter directed by the Berlin-trained ]—and '']'' (1934), directed by Austrian émigré ].<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 11–13.</ref> The Universal horror film that comes closest to noir, in story and sensibility, is '']'' (1933), directed by Englishman ] and photographed by American ]. Edeson later photographed '']'' (1941), widely regarded as the first major film noir of the classic era.<ref>Davis (2004), p. 194. See also Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 133; Ottoson (1981), pp. 110–111. Vernet (1993) notes that the techniques now associated with Expressionism were evident in the American cinema from the mid-1910s (pp. 9–12).</ref> | |||

| Most of the film noirs of the classic period were low- and modestly budgeted features without major stars (] either literally or in spirit), in which writers, directors, cinematographers, and other craftsmen found themselves relatively free from the typical big-picture constraints. While enforcement of the ] ensured that no movie character could literally get away with murder, at the B level of noir especially, one could come awful close. Thematically, film noirs as a group were most exceptional for the relative frequency with which they centered on women of questionable virtue—a focus very rare in Hollywood films after the mid-1930s and the end of the ] era. The signal movie in this vein was ''Double Indemnity'', directed by Billy Wilder; setting the mold was ]'s unforgettable ], Phyllis Dietrichson—an apparent nod to ], who had built her extraordinary career playing such characters for Sternberg. An A-level feature all the way, the movie's commercial success and seven ] nominations made it probably the most influential of the early noirs; in particular, it led to a spate of what later became known as "]." | |||

| ] was directing in Hollywood during the same period. Films of his such as '']'' (1932) and '']'' (1935), with their hothouse eroticism and baroque visual style anticipated central elements of classic noir. The commercial and critical success of Sternberg's silent '']'' (1927) was largely responsible for spurring a trend of Hollywood gangster films.<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 6.</ref> Successful films in that genre such as '']'' (1931), '']'' (1931) and '']'' (1932) demonstrated that there was an audience for crime dramas with morally reprehensible protagonists.<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 6–9; Silver and Ward (1992), pp. 323–24.</ref> An important, possibly influential, cinematic antecedent to classic noir was 1930s French ], with its romantic, ] attitude and celebration of doomed heroes.<ref>Spicer (2007), pp. 26, 28; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 13–15; Bould (2005), pp. 33–40.</ref> The movement's sensibility is mirrored in the ] drama '']'' (1932), a forerunner of noir.<ref>McGarry (1980), p. 139.</ref> Among films not considered noir, perhaps none had a greater effect on the development of the genre than '']'' (1941), directed by ]. Its visual intricacy and complex, ] narrative structure are echoed in dozens of classic films noir.<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 20; Schatz (1981), pp. 116–22; Ottoson (1981), p. 2.</ref> | |||

| Conventional A films, however emotionally tortuous, were ultimately expected to convey positive, reassuring messages; in terms of style, invisible camerawork and ] techniques, flattering soft lighting schemes, and deluxely trimmed sets were the rule. The makers of film noir turned all this on its head, creating sophisticated, sometimes bleak dramas tinged with mistrust, cynicism, and a sense of the ], in settings that were frequently either real-life urban or budget-saving minimalist, with often strikingly expressionist lighting and unsettling techniques such as wildly skewed camera angles and convoluted flashbacks. The noir style gradually influenced the mainstream—even beyond Hollywood. | |||

| ] of the 1940s, with its emphasis on ] authenticity, was an acknowledged influence on trends that emerged in American noir. '']'' (1945), directed by ], another Vienna-born, Berlin-trained American ], tells the story of an alcoholic in a manner evocative of neorealism.<ref>Biesen (2005), p. 207.</ref> It also exemplifies the problem of classification: one of the first American films to be described as a film noir, it has largely disappeared from considerations of the field.<ref>Naremore (2008), pp. 13–14.</ref> Director ] of '']'' (1948) pointed to the neorealists as inspiring his use of location photography with non-professional extras. This semidocumentary approach characterized a substantial number of noirs in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Along with neorealism, the style had an American precedent cited by Dassin, in director ]'s '']'' (1945), which demonstrated the parallel influence of the cinematic newsreel.<ref>Krutnik, Neale, and Neve (2008), pp. 147–148; Macek and Silver (1980), p. 135.</ref> | |||

| ===Thirty-five notable American film noirs of the classic period=== | |||

| '''(with directors and significant noir performers—''supporting players in italics'')'''{{fn|1}} | |||

| === |

===Literary sources=== | ||

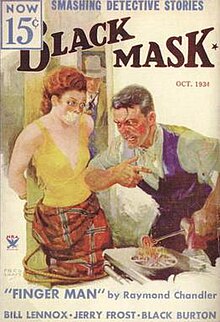

| ]'' featured the first appearance of the detective character whom ] developed into the famous ].<ref>Widdicombe (2001), pp. 37–39, 59–60, 118–19; {{cite web|author=Doherty, Jim|url=http://www.thrillingdetective.com/carmady.html|title=Carmady|publisher=Thrilling Detective Web Site|access-date=2010-02-25|archive-date=2010-01-04|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100104102528/http://thrillingdetective.com/carmady.html|url-status=live}}</ref>]] | |||

| *'']'' (1940) d. Boris Ingster, w/ ], '']'' | |||

| *'']'' (1941) d. ], w/ ], ], '']'' | |||

| *'']'' (1941) d. ], w/ Bogart, ''Lorre, ], Cook'' (costarring ]) | |||

| *'']'' (1943) d. ], w/ ] | |||

| *'']'' (1944) d. ], w/ ], ], ] | |||

| *'']'' (1944) d. ], w/ ], ], ] | |||

| *'']'' (1945) d. Wilder, w/ ] | |||

| *'']'' (1945) d. ], w/ ], ], '']'' | |||

| *'']'' (1946) d. ], w/ Bogart, ], ''], Cook'' | |||

| *'']'' (1946) d. ], w/ ], ], ''], ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1946) d. ], w/ ], ], ], ''], ], ], ], ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1946) d. Hitchcock, w/ ] (starring ] and ]) | |||

| *'']'' (1946) d. ], w/ ], ], '']'' | |||

| *'']'' (1946) d. ], w/ Robinson, ], Welles, ''Erskine Sanford'' | |||

| *'']'' (1947) d. ], w/ Bogart, Bacall, ''Bennett'' | |||

| *'']'' (1947) d. Welles, w/ Hayworth, Welles, ''], ], Sanford'' | |||

| *'']'' (1947) d. ], w/ Mitchum, ], ], ''], ], ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1948) d. Huston, w/ Bogart, Robinson, Bacall, ''], ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1949) d. ], w/ ], Totter, ''], ], ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1949) d. Walsh, w/ ], O'Brien, ''], ]'' (costarring ]) | |||

| The primary literary influence on film noir was the ] school of American ] and ], led in its early years by such writers as ] (whose first novel, '']'', was published in 1929) and ] (whose '']'' appeared five years later), and popularized in ]s such as '']''. The classic film noirs '']'' (1941) and '']'' (1942) were based on novels by Hammett; Cain's novels provided the basis for '']'' (1944), '']'' (1945), '']'' (1946), and '']'' (1956; adapted from ''Love's Lovely Counterfeit''). A decade before the classic era, a story by Hammett was the source for the gangster melodrama '']'' (1931), directed by ] and photographed by ], who worked regularly with Sternberg. Released the month before Lang's ''M'', ''City Streets'' has a claim to being the first major film noir; both its style and story had many noir characteristics.<ref>See, e.g., Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 6; Macek (1980), pp. 59–60.</ref> | |||

| ====1950–1958==== | |||

| *'']'' (1950) d. Huston, w/ ], ''], ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1950) d. ], w/ O'Brien, '']'' | |||

| *'']'' (1950) d. ], w/ Bogart, ], ''], Carl Benton Reid, ], Jeff Donnell'' | |||

| *'']'' (1950) d. ], w/ ], ], '']'' ]" below for its status as an American noir] | |||

| *'']'' (1950) d. Wilder, w/ ], ''Clark, ]'' (costarring ]) | |||

| *'']'' (1951) d. Wilder, w/ Douglas, ], ''], ], ], Teal, Lewis Martin, ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1951) d. Hitchcock, w/ ], ], ''], ]'' (costarring ]) | |||

| *'']'' (1953) d. ], w/ Widmark, ''], ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1953) d. ], w/ Ford, Grahame, ''], ], Doucette'' | |||

| *'']'' (1955) d. ], w/ ''Dekker, ], Marian Carr, ], Helton'' (starring ]) | |||

| *'']'' (1955) d. ], w/ Mitchum, ] (costarring ]) | |||

| *'']'' (1956) d. ], w/ Hayden, ], ], ''], Cook, ], de Corsia, Carey, ], ]'' | |||

| *'']'' (1956) d. Hitchcock, w/ ], '']'' (costarring ]) | |||

| *'']'' (1957) d. ], w/ Lancaster, ], ''Levene, Donnell, Jay Adler'' | |||

| *'']'' (1958) d. Welles, w/ ], ], Welles, ''Calleia, ]'' | |||

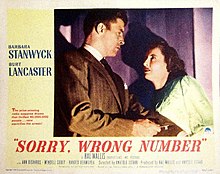

| ], who debuted as a novelist with '']'' in 1939, soon became the most famous author of the hardboiled school. Not only were Chandler's novels turned into major noirs—'']'' (1944; adapted from '']''), '']'' (1946), and '']'' (1947)—he was an important ] in the genre as well, producing the scripts for ''Double Indemnity'', '']'' (1946), and '']'' (1951). Where Chandler, like Hammett, centered most of his novels and stories on the character of the private eye, Cain featured less heroic protagonists and focused more on psychological exposition than on crime solving;<ref>Irwin (2006), pp. 71, 95–96.</ref> the Cain approach has come to be identified with a subset of the hardboiled genre dubbed "]". For much of the 1940s, one of the most prolific and successful authors of this often downbeat brand of suspense tale was ] (sometimes under the pseudonym George Hopley or William Irish). No writer's published work provided the basis for more noir films of the classic period than Woolrich's: thirteen in all, including '']'' (1946), '']'' (1946), and '']'' (1947).<ref>Irwin (2006), pp. 123–24, 129–30.</ref> | |||

| For an expanded list of films considered "noir," see ] | |||

| Another crucial literary source for film noir was ], whose first novel to be published was ''Little Caesar'', in 1929. It was turned into a hit for ] in 1931; the following year, Burnett was hired to write dialogue for ''Scarface'', while '']'' (1932) was adapted from one of his stories. At least one important reference work identifies the latter as a film noir despite its early date.<ref>White (1980), p. 17.</ref> Burnett's characteristic narrative approach fell somewhere between that of the quintessential hardboiled writers and their noir fiction compatriots—his protagonists were often heroic in their own way, which happened to be that of the gangster. During the classic era, his work, either as author or screenwriter, was the basis for seven films now widely regarded as noir, including three of the most famous: '']'' (1941), '']'' (1942), and '']'' (1950).<ref>Irwin (2006), pp. 97–98, 188–89.</ref> | |||

| ==Classic period== | |||

| ===Overview=== | |||

| The 1940s and 1950s are generally regarded as the classic period of American film noir. While ''City Streets'' and other pre-WWII crime melodramas such as '']'' (1936) and '']'' (1937), both directed by Fritz Lang, are categorized as full-fledged noir in Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward's film noir encyclopedia, other critics tend to describe them as "proto-noir" or in similar terms.<ref>Silver and Ward (1992), p. 333, as well as entries on individual films, pp. 59–60, 109–10, 320–21. For description of ''City Streets'' as "proto-noir", see Turan (2008). For description of ''Fury'' as "proto-noir", see Machura, Stefan, and Peter Robson, ''Law and Film'' (2001), p. 13. For description of ''You Only Live Once'' as "pre-noir", see Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 9.</ref> | |||

| The film now most commonly cited as the first "true" film noir is '']'' (1940), directed by Latvian-born, Soviet-trained ].<ref name=3d>See, e.g., Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 19; Irwin (2006), p. 210; Lyons (2000), p. 36; Porfirio (1980), p. 269.</ref> Hungarian émigré ]—who had starred in Lang's '']''—was top-billed, although he did not play the primary lead. (He later played ] in several other formative American noirs.) Although modestly budgeted, at the high end of the ] scale, ''Stranger on the Third Floor'' still lost its studio, ], US$56,000 ({{Inflation|US|56000|1940|fmt=eq}}), almost a third of its total cost.<ref>Biesen (2005), p. 33.</ref> '']'' magazine found Ingster's work: "...too studied and when original, lacks the flare {{sic}} to hold attention. It's a film too arty for average audiences, and too humdrum for others."<ref>''Variety'' (1940).</ref> ''Stranger on the Third Floor'' was not recognized as the beginning of a trend, let alone a new genre, for many decades.<ref name=3d/> | |||

| {{Quote box | |||

| |quote = Whoever went to the movies with any regularity during 1946 was caught in the midst of Hollywood's profound postwar affection for morbid drama. From January through December deep shadows, clutching hands, exploding revolvers, sadistic villains and heroines tormented with deeply rooted diseases of the mind flashed across the screen in a panting display of psychoneurosis, unsublimated sex and murder most foul. | |||

| |source = Donald Marshman, ''Life'' (August 25, 1947)<ref>Marshman (1947), pp. 100–1.</ref> | |||

| |width = 35% | |||

| |align = right | |||

| |salign = right | |||

| }} | |||

| Most film noirs of the classic period were similarly low- and modestly-budgeted features without major stars—] either literally or in spirit. In this production context, writers, directors, cinematographers, and other craftsmen were relatively free from typical big-picture constraints. There was more visual experimentation than in Hollywood filmmaking as a whole: the Expressionism now closely associated with noir and the semi-documentary style that later emerged represent two very different tendencies. Narrative structures sometimes involved convoluted flashbacks uncommon in non-noir commercial productions. In terms of content, enforcement of the ] ensured that no film character could literally get away with murder or be seen sharing a bed with anyone but a spouse; within those bounds, however, many films now identified as noir feature plot elements and dialogue that were very risqué for the time.<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 4, 19–26, 28–33; Hirsch (2001), pp. 1–21; Schatz (1981), pp. 111–16.</ref> | |||

| ]'' (1947) directed by ], features many of the genre's hallmarks: a cynical private detective as the protagonist, a ], multiple ] with ] narration, ] photography, and a ] mood leavened with provocative banter. Pictured are noir icons ] and ].]] | |||

| Thematically, films noir were most exceptional for the relative frequency with which they centered on ] of questionable virtue—a focus that had become rare in Hollywood films after the mid-1930s and the end of the ] era. The signal film in this vein was '']'', directed by Billy Wilder; setting the mold was ]'s ], Phyllis Dietrichson—an apparent nod to ], who had built her extraordinary career playing such characters for Sternberg. An A-level feature, the film's commercial success and seven ] nominations made it probably the most influential of the early noirs.<ref>See, e.g., Naremore (2008), pp. 81, 319 n. 13; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 86–88.</ref> A slew of now-renowned noir "bad girls" followed, such as those played by ] in '']'' (1946), ] in '']'' (1946), ] in '']'' (1946), and ] in '']'' (1947). The iconic noir counterpart to the femme fatale, the private eye, came to the fore in films such as '']'' (1941), with ] as ], and '']'' (1944), with ] as ]. | |||

| The prevalence of the private eye as a lead character declined in film noir of the 1950s, a period during which several critics describe the form as becoming more focused on extreme psychologies and more exaggerated in general.<ref>See, e.g., Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 30; Hirsch (2001), pp. 12, 202; Schrader (1972), pp. 59–61 .</ref> A prime example is '']'' (1955); based on a novel by ], the best-selling of all the hardboiled authors, here the protagonist is a private eye, ]. As described by ], "]'s teasing direction carries ''noir'' to its sleaziest and most perversely erotic. Hammer overturns the underworld in search of the 'great whatsit' turns out to be—joke of jokes—an exploding atomic bomb."<ref>Schrader (1972), p. 61.</ref> Orson Welles's baroquely styled '']'' (1958) is frequently cited as the last noir of the classic period.<ref>See, e.g., Silver (1996), p. 11; Ottoson (1981), pp. 182–183; Schrader (1972), p. 61.</ref> Some scholars believe film noir never really ended, but continued to transform even as the characteristic noir visual style began to seem dated and changing production conditions led Hollywood in different directions—in this view, post-1950s films in the noir tradition are seen as part of a continuity with classic noir.<ref>See, e.g., Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 19–53.</ref> A majority of critics, however, regard comparable films made outside the classic era to be something other than genuine film noir. They regard true film noir as belonging to a temporally and geographically limited cycle or period, treating subsequent films that evoke the classics as fundamentally different due to general shifts in filmmaking style and latter-day awareness of noir as a historical source for ].<ref>See, e.g., Hirsch (2001), pp. 10, 202–7; Silver and Ward (1992), p. 6 (though they phrase their position more ambiguously on p. 398); Ottoson (1981), p. 1.</ref> These later films are often called ]. | |||

| ===Directors and the business of noir=== | ===Directors and the business of noir=== | ||

| ]'' (1950), directed by ] based on a novel by ] writer ]. Two of |

]'' (1950), directed by ] and based on a novel by ] writer ]. Two of noir's defining actors, ] and ], portray star-crossed lovers in the film.]] | ||

| While the inceptive ''Stranger on the Third Floor'' was an ] B-picture, directed by a virtual unknown, the preceding list of films—based primarily on enduring fame—leans heavily toward A-list productions by name-brand directors such as Wilder, ], and ] (who debuted as a director with ''The Maltese Falcon''). ]'s success with '']'' made his name (he honored the debt by making two other classic ] noirs with ], '']'' and '']'' ) and '']'' did something similar for ]'s career (his other noirs include his debut, '']'' , and '']'' ). | |||

| While the inceptive noir, ''Stranger on the Third Floor'', was a B picture directed by a virtual unknown, many of the films noir still remembered were A-list productions by well-known film makers. Debuting as a director with '']'' (1941), ] followed with '']'' (1948) and '']'' (1950). Opinion is divided on the noir status of several ] thrillers from the era; at least four qualify by consensus: '']'' (1943), '']'' (1946), '']'' (1951) and '']'' (1956),<ref>See, e.g., entries on individual films in Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 34, 190–92; Silver and Ward (1992), pp. 214–15; 253–54, 269–70, 318–19.</ref> ]'s success with '']'' (1944) made his name and helped demonstrate noir's adaptability to a high-gloss ] presentation.<ref>Biesen (2005), p. 162.</ref> Among Hollywood's most celebrated directors of the era, arguably none worked more often in a noir mode than Preminger; his other noirs include '']'' (1945), '']'' (1949), '']'' (1950) (all for Fox) and '']'' (1952). A half-decade after ''Double Indemnity'' and ''The Lost Weekend'', Billy Wilder made '']'' (1950) and '']'' (1951), noirs that were not so much crime dramas as satires on Hollywood and the news media respectively. '']'' (1950) was ]'s breakthrough; his other noirs include his debut, '']'' (1948) and '']'' (1952), noted for their unusually sympathetic treatment of characters alienated from the social mainstream.<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 188, 202–3.</ref> | |||

| Orson Welles had notorious problems with financing, but his three film noirs were reasonably well budgeted: '']'' received top-level, "prestige" backing, while both '']'' (his most conventional film) and ''Touch of Evil'' (an unmistakably personal work) were funded at levels lower but still commensurate with a headlining release. Like ''The Stranger'', Fritz Lang's '']'' (1945) was a production of the independent International Pictures. Lang's follow-up, the wickedly entertaining '']'' (1945), was semi-independent—cosponsored by ] and his own Diana Productions, of which the movie's costar, ], was the second biggest shareholder. Lang, Bennett, and her husband, Universal veteran and Diana production head ], would make '']'' (1948) in similar fashion.<ref>McGilligan (1997), pp. 314–317.</ref> Before he was forced abroad for political reasons, director Jules Dassin made two classic noirs that also stradled the major/independent line: '']'' (1947) and the influential documentary-style ''Naked City'' were developed by producer ], who had an "inside/outside" contract with Universal similar to Wanger's.<ref>Schatz (1998), pp. 354–358.</ref> Years earlier, working at Warner Bros., Hellinger had produced three films for ], the proto-noirs '']'' (1940) and ''Manpower'' (1941) and the recognized classic '']''. Walsh had no great name recognition during his half-century as a working director, but his noirs—'']'' and '']'' (1951) would follow—had A-list stars and were of consistently high quality. In addition to the aforementioned, other directors associated with top-of-the-bill Hollywood film noirs include ] (''Murder, My Sweet''; '']'' ), the first important noir director to fall prey to the ], as well as ] ('']'' , '']'' ) and ] ('']'' , '']'' ). | |||

| ] in the trailer for '']'' (1947)]] | |||

| But again, most of the Hollywood films now considered classic noir are known as "B-movies"—some in the most precise sense, produced to run on the bottom of ] by a low-budget unit of one of the ] or by one of the smaller, so-called ] outfits, from the relatively well-off ] to shakier ventures such as ]. ] had made over thirty Hollywood Bs (a few now highly regarded, most completely forgotten) before directing the A-level '']'', considered by some critics the pinnacle of classic noir. Movies with budgets a step up the ladder, known as "intermediates" within the industry, might be treated as A or B pictures depending on the circumstance—Monogram created a new unit, Allied Artists, in the late 1940s to focus on this sort of production. Such films have long colloquially been referred to as B-movies. ] (cited above, also '']'' ) and ] ('']'' , '']'' ) each made a series of impressive intermediates, many of them noirs, before graduating to steady work on big-budget productions. Mann did some of his finest work with cinematographer ], a specialist in what critic James Naremore describes as "hypnotic moments of light-in-darkness."<ref>Naremore (1998), p. 173.</ref> '']'' (1948), shot by Alton and, though credited solely to Alfred Werker, directed in large part by Mann, demonstrates their technical mastery and exemplifies the late 1940s trend of "]" crime dramas. Put out, like other Mann–Alton noirs, by the small ] company, it was the direct inspiration for the '']'' series, which debuted on radio in 1949 and television in 1951. | |||

| Orson Welles had notorious problems with financing but his three film noirs were well-budgeted: '']'' (1947) received top-level, "prestige" backing, while '']'' (1946), his most conventional film, and '']'' (1958), an unmistakably personal work, were funded at levels lower but still commensurate with headlining releases.<ref>For overview of Welles's noirs, see, e.g., Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 210–11. For specific production circumstances, see Brady, Frank, ''Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles'' (1989), pp. 395–404, 378–81, 496–512.</ref> Like ''The Stranger'', Fritz Lang's '']'' (1944) was a production of the independent International Pictures. Lang's follow-up, '']'' (1945), was one of the few classic noirs to be officially censored: filled with erotic innuendo, it was temporarily banned in Milwaukee, Atlanta and New York State.<ref>Bernstein (1995).</ref> ''Scarlet Street'' was a semi-independent, cosponsored by ] and Lang's Diana Productions, of which the film's co-star, ], was the second biggest shareholder. Lang, Bennett and her husband, the Universal veteran and Diana production head ], made '']'' (1948) in similar fashion.<ref>McGilligan (1997), pp. 314–17.</ref> | |||

| ]'' (1945) cost $117,000 to make when the major Hollywood studios spent around $1 million on the average feature. But the accountants at small ] weren't happy—it was 30% ''over'' budget.]] | |||

| Directors such as ] (cited above, also ''Underworld U.S.A.'' ), ] ('']'' , '']'' ), and ] ('']'' , ''The Brothers Rico'' ) built now well-respected oeuvres largely at the B-movie/intermediate level. (]—like Dmytryk, one of the ]—wrote the ''Gun Crazy'' screenplay disguised by a front while still blacklisted.) In 1945, Edgar G. Ulmer made one of the all-time noir cult classics, '']'', at PRC. A number of low and modestly budgeted films were made by independent, often actor-owned, companies contracting with one of the larger outfits for distribution. It was in this way that accomplished noir actress ] became the sole female director in Hollywood during the late 1940s and much of the 1950s—her best-known film is '']'' (1953), developed by her company, The Filmakers, with support and distribution by RKO. It is one of the seven classic film noirs produced largely outside of the major studios that have been chosen to date for the United States ]; the others are ''Detour'', ''Gun Crazy'', ''D.O.A.'', ''Kiss Me Deadly'', ''Sweet Smell of Success'' (the preceding four distributed by ], the "studio without a studio"), and '']'' (1948; dist. ]), directed by ] and starring ], both of whom would be blacklisted in the 1950s. Independent production usually meant restricted circumstances, but not always—''Sweet Smell of Success'', for instance, despite the original plans of the production team, was clearly not made on the cheap, though like many other cherished A-budget noirs it might be said to have a B-movie soul. | |||

| Before leaving the United States while subject to the ], Jules Dassin made two classic noirs that also straddled the major/independent line: '']'' (1947) and the influential documentary-style '']'' (1948) were developed by producer ], who had an "inside/outside" contract with Universal similar to Wanger's.<ref>Schatz (1998), pp. 354–58.</ref> Years earlier, working at Warner Bros., Hellinger had produced three films for ], the proto-noirs '']'' (1940), '']'' (1941) and '']'' (1941), now regarded as a seminal work in noir's development.<ref>See, e.g., Schatz (1981), pp. 103, 112.</ref> Walsh had no great name during his half-century as a director but his noirs '']'' (1947), '']'' (1949) and '']'' (1951) had A-list stars and are seen as important examples of the cycle.<ref>See, e.g., entries on individual films in Silver and Ward (1992), pp. 97–98, 125–26, 311–12.</ref> Other directors associated with top-of-the-bill Hollywood films noir include ] ('']'' (1944), '']'' (1947))—the first important noir director to fall prey to the industry blacklist—as well as ] ('']'' (1946), '']'' (1947)) and ] ('']'' (1948), '']'' (1948)). | |||

| Perhaps no director better displayed that spirit than the German-born ], who had already made a score of films before his 1940 arrival in Hollywood. Working mostly on A features, he made eight movies now regarded as classic film noirs (a figure matched only by Lang and Mann). In addition to '']'', ]'s debut and a Hellinger/Universal coproduction, Siodmak's other important contributions to the genre include 1944's '']'' (a top-of-the-line B and Woolrich adaptation), the ironically titled '']'' (1944), and '']'' (1948). '']'' (1949), with Lancaster again the lead, exemplifies how Siodmak brought the virtues of the B-movie to the A noir. In addition to the relatively looser constraints on character and message at lower budgets, the nature of B production lent itself to the noir style for directly economic reasons: dim lighting not only saved on electrical costs but helped cloak cheap sets (mist and smoke also served the cause); night shooting was often compelled by hurried production schedules; plots with obscure motivations and intriguingly elliptical transitions were sometimes the consequence of scripts written in haste, not every scene of which was there always time or money to shoot. In ''Criss Cross'', Siodmak achieves all these effects with purpose, wrapping them around ], playing the most understandable of femme fatales, ], in one of his deliciously charismatic villain roles, and Lancaster—already an established star—as an ordinary joe turned armed robber, a romantic obsessive on a one-way ride to ruin. | |||

| Most of the Hollywood films considered to be classic noirs fall into the category of the B movie.<ref>See Naremore (2008), pp. 140–55, on "B Pictures versus Intermediates".</ref> Some were Bs in the most precise sense, produced to run on the bottom of ] by a low-budget unit of one of the ] or by one of the smaller ] outfits, from the relatively well-off ] to shakier ventures such as ]. ] had made over thirty Hollywood Bs (a few now highly regarded, most forgotten) before directing the A-level ''Out of the Past'', described by scholar Robert Ottoson as "the ''ne plus ultra'' of forties film noir".<ref>Ottoson (1981), p. 132.</ref> Movies with budgets a step up the ladder, known as "intermediates" by the industry, might be treated as A or B pictures depending on the circumstances. Monogram created ] in the late 1940s to focus on this sort of production. ] ('']'' , '']'' ) and ] ('']'' and '']'' ) each made a series of impressive intermediates, many of them noirs, before graduating to steady work on big-budget productions. Mann did some of his most celebrated work with cinematographer ], a specialist in what James Naremore called "hypnotic moments of light-in-darkness".<ref>Naremore (2008), p. 173.</ref> '']'' (1948), shot by Alton though credited solely to Alfred Werker, directed in large part by Mann, demonstrates their technical mastery and exemplifies the late 1940s trend of "]" crime dramas. It was released, like other Mann-Alton noirs, by the small ] company; it was the inspiration for the '']'' series, which debuted on radio in 1949 and television in 1951.<ref>Hayde (2001), pp. 3–4, 15–21, 37.</ref> | |||

| ==Film noir outside the United States== | |||

| Some critics regard classic film noir as a cycle exclusive to the United States; e.g., Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward: "With the Western, film noir shares the distinction of being an indigenous American form...a wholly American film style."<ref>Silver and Ward (1992), p. 1.</ref> Others, however, regard noir as an international phenomenon.<ref>See Palmer (2004), pp. 267–268, for a representative discussion of film noir as an international phenomenon.</ref> Even before the beginning of the generally accepted classic period, there were movies made far from Hollywood that can be seen in retrospect as film noirs, for example, the French productions '']'' (1937), directed by Jules Duvivier, and '']'' (1939), directed by ]. | |||

| ]'' (1945) cost $117,000 to make when the biggest Hollywood studios spent around $600,000 on the average feature. Produced at small ], however, the film was 30 percent over budget.<ref>Erickson (2004), p. 26.</ref>]] | |||

| ] in ]'s '']'' (''Elevator to the Gallows''; 1958). The film features one of the most acclaimed of all noir ], composed and performed by jazz musician ].]] | |||

| Several directors associated with noir built well-respected oeuvres largely at the B-movie/intermediate level. ]'s brutal, visually energetic films such as '']'' (1953) and '']'' (1961) earned him a unique reputation; his advocates praise him as "primitive" and "barbarous".<ref>Sarris (1985), p. 93.</ref><ref>Thomson (1998), p. 269.</ref> ] directed noirs as diverse as '']'' (1950) and '']'' (1955). The former—whose screenplay was written by the blacklisted ], disguised by a front—features a bank hold-up sequence shown in an unbroken take of over three minutes that was influential.<ref>Naremore (2008), pp. 128, 150–51; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 97–99.</ref> ''The Big Combo'' was shot by John Alton and took the shadowy noir style to its outer limits.<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 59–60.</ref> The most distinctive films of ] ('']'' and '']'' ) tell stories of vice organized on a monstrous scale.<ref>Clarens (1980), pp. 245–47.</ref> The work of other directors in this tier of the industry, such as ] ('']'' , '']'' ), has become obscure. ] spent most of his Hollywood career working at B studios and once in a while on projects that achieved intermediate status; for the most part, on unmistakable Bs. In 1945, while at PRC, he directed a noir cult classic, '']''.<ref>See, e.g., Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 83–85; Ottoson (1981), pp. 60–61.</ref> Ulmer's other noirs include '']'' (1945), also for PRC; '']'' (1948), for Eagle-Lion, which had acquired PRC the previous year and '']'' (1955), for Allied Artists. | |||

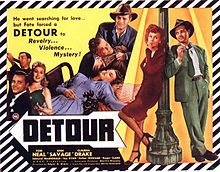

| A number of low- and modestly-budgeted noirs were made by independent, often actor-owned, companies contracting with larger studios for distribution. Serving as producer, writer, director and top-billed performer, ] made films like '']'' (1951), '']'' (1954) and Jacques Tourneur, ''] (1958)''. It was in this way that accomplished noir actress ] established herself as the sole female director in Hollywood during the late 1940s and much of the 1950s. She does not appear in the best-known film she directed, '']'' (1953), developed by her company, The Filmakers, with support and distribution by RKO.<ref>Muller (1998), pp. 176–77.</ref> It is one of the seven classic film noirs produced largely outside of the major studios that have been chosen for the United States ]. Of the others, one was a small-studio release: ''Detour''. Four were independent productions distributed by ], the "studio without a studio": ''Gun Crazy''; ''Kiss Me Deadly''; '']'' (1950), directed by ] and '']'' (1957), directed by ]. One was an independent distributed by ], the industry leader: '']'' (1948), directed by ] and starring ], both of whom were blacklisted in the 1950s.<ref>Krutnik, Neale, and Neve (2008), pp. 259–60, 262–63.</ref> Independent production usually meant restricted circumstances but ''Sweet Smell of Success'', despite the plans of the production team, was clearly not made on the cheap, though like many other cherished A-budget noirs, it might be said to have a B-movie soul.<ref>See Mackendrick (2006), pp. 119–20.</ref> | |||

| During the classic period, there were many films produced outside the United States, particularly in France, that share elements of style, theme, and sensibility with American film noirs and may themselves be included in the genre's canon. In certain cases, the interrelationship with Hollywood noir is obvious: American-born director Jules Dassin moved to France in the early 1950s as a result of the Hollywood blacklist, and made one of the most famous French film noirs, '']'' (1955). Other well-known French films often classified as noir include '']'' (1947), '']'' (released in English-speaking countries as ''The Wages of Fear'') (1953) and '']'' (1955), all directed by ]; '']'' (1952) and '']'' (1954), both directed by ]; and '']'' (1958), directed by ]. French director ] is widely recognized for his tragic, minimalist film noirs—''Quand tu liras cette lettre'' (1953) and '']'' (1955), from the classic period, were followed by '']'' (1962), '']'' (1967), and '']'' (1970). | |||

| Perhaps no director better displayed that spirit than the German-born ], who had already made a score of films before his 1940 arrival in Hollywood. Working mostly on A features, he made eight films now regarded as classic-era noir (a figure matched only by Lang and Mann).<ref>See, e.g., Silver and Ward (1992), pp. 338–39. Ottoson (1981) also lists two period pieces directed by Siodmak ('']'' and '']'' ) (pp. 173–74, 164–65). Silver and Ward list nine classic-era film noirs by Lang, plus two from the 1930s (pp. 338, 396). Ottoson lists eight (excluding '']'' ), plus the same two from the 1930s (passim). Silver and Ward list seven by Mann (p. 338). Ottoson also lists '']'' (a.k.a. ''The Black Book''; 1949), set during the French Revolution, for a total of eight (passim). See also Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 241.</ref> In addition to ''The Killers'', ]'s debut and a Hellinger/Universal co-production, Siodmak's other important contributions to the genre include 1944's '']'' (a top-of-the-line B and Woolrich adaptation), the ironically titled '']'' (1944), and '']'' (1948). '']'' (1949), with Lancaster again the lead, exemplifies how Siodmak brought the virtues of the B-movie to the A noir. In addition to the relatively looser constraints on character and message at lower budgets, the nature of B production lent itself to the noir style for economic reasons: dim lighting saved on electricity and helped cloak cheap sets (mist and smoke also served the cause). Night shooting was often compelled by hurried production schedules. Plots with obscure motivations and intriguingly elliptical transitions were sometimes the consequence of hastily written scripts. There was not always enough time or money to shoot every scene. In ''Criss Cross'', Siodmak achieved these effects, wrapping them around ], who played the most understandable of femme fatales; ], in one of his many charismatic villain roles; and Lancaster as an ordinary laborer turned armed robber, doomed by a romantic obsession.<ref>Clarens (1980), pp. 200–2; Walker (1992), pp. 139–45; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 77–79.</ref> | |||

| A number of thrillers produced in Great Britain during the classic period are also frequently referred to as film noirs, including '']'' (1947), directed by ]; '']'' (1947), directed by Alberto Cavalcanti; '']'' (1949), directed by ] and ]; and '']'' (1955), directed by ]. Before leaving for France, Jules Dassin had been obliged by political pressure to shoot his last English-language film of the classic noir period in Great Britain: '']'' (1950), though it was conceived in the United States and was not only directed by an American but also stars an American actor (]), is technically a UK production, financed by ]'s British subsidiary. The most famous of classic British noirs is director ]'s '']'' (1949), like ''Brighton Rock'' based on a ] novel. Set in Vienna immediately after World War II, it stars ] and Orson Welles, both prominent American actors who starred in U.S. film noirs; despite being a completely British production, the movie is sometimes discussed as if it is a classic Hollywood noir. | |||

| {| style="width:94%; margin:auto; text-align:center; font-size:87%; clear:both;" | |||

| Elsewhere, Italian director ] adapted Cain's ''The Postman Always Rings Twice'' as '']'' (1943), regarded both as one of the great noirs and a seminal film in the development of neorealism. (This was not even the first screen version of Cain's novel, having been preceded by the French ''Le Dernier tournant'' in 1939.) In Japan, the celebrated ] directed several movies recognizable as film noirs, including '']'' (1948), '']'' (1949), and '']'' (1963). | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| | |||

| ! style="background:#dbdaba; font-weight:normal; line-height:normal;"| <span style="font-size: 14px;">'''Classic-era film noirs in the ]'''</span> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background-color:#fff; width:55px; background-color:#dbdaba; font-size:11px;"|] | |||

| | style="background:#f5f5ec;"| | |||

| {{flatlist| | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']''}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="background:#dbdaba; font-size:11px;"|] | |||

| | style="background:#f5f5ec;"| | |||

| {{flatlist| | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| }} | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Outside the United States== | |||

| Among the first major neo-noir films—the term often applied to movies that consciously refer back to the classic noir tradition—was the French '']'' (1960), directed by ] from a novel by one of the gloomiest of American noir fiction writers, ]. Noir crime films and melodramas have been produced in many countries in the post-classic area, some of them quintessentially self-aware neo-noirs, others simply sharing a version of the hardboiled sensibility associated with classic noir. Notable examples include '']'' (1969; Italy), '']'' (1974; Japan), '']'' (1977; Germany), '']'' (1984; Denmark), '']'' (1988; Hong Kong), '']'' (1997; Norway), '']'' (1998; UK), and '']'' (2003; China). | |||

| {{listen|filename=17 Generique.ogg|title="Générique" ("Nuit sur les Champs-Élysées")| description= The moody, evocative music improvised by jazz trumpeter ]'s quintet for '']'' (1958) is regarded as one of the definitive noir scores.<ref>Butler (2002), p. 12.</ref>}} | |||

| Some critics regard classic film noir as a cycle exclusive to the United States; Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward, for example, argue, "With the Western, film noir shares the distinction of being an indigenous American form ... a wholly American film style."<ref>Silver and Ward (1992), p. 1.</ref> However, although the term "film noir" was originally coined to describe Hollywood movies, it was an international phenomenon.<ref>See Palmer (2004), pp. 267–68, for a representative discussion of film noir as an international phenomenon.</ref> Even before the beginning of the generally accepted classic period, there were films made far from Hollywood that can be seen in retrospect as films noir, for example, the French productions '']'' (1937), directed by ], and '']'' (1939), directed by ].<ref>Spicer (2007), pp. 5–6, 26, 28, 59; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 14–15.</ref> In addition, ] experienced a vibrant film noir period from roughly 1946 to 1952, which was around the same time film noir was blossoming in the United States.<ref>{{cite news|last=Jones|first=Kristin|date=2015-07-21|access-date=2018-04-30|title=A Series on Mexican Noir Films Illuminates a Dark Genre|url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-series-on-mexican-noir-films-illuminates-a-dark-genre-1437513037|newspaper=The Wall Street Journal|archive-date=2018-04-26|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180426012214/https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-series-on-mexican-noir-films-illuminates-a-dark-genre-1437513037|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| During the classic period, there were many films produced in Europe, particularly in France, that share elements of style, theme, and sensibility with American films noir and may themselves be included in the genre's canon. In certain cases, the interrelationship with Hollywood noir is obvious: American-born director ] moved to France in the early 1950s as a result of the ], and made one of the most famous French film noirs, '']'' (1955). Other well-known French films often classified as noir include '']'' (1947) and '']'' (1955), both directed by ]. '']'' (1952), '']'' (1954), and '']'' (1960) directed by ]; and '']'' (1958), directed by ]. French director ] is widely recognized for his tragic, minimalist films noir—'']'' (1955), from the classic period, was followed by '']'' (1962), '']'' 1966), '']'' (1967), and '']'' (1970).<ref>Spicer (2007), pp. 32–39, 43; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 255–61.</ref> In the 1960s, Greek films noir "''The Secret of the Red Mantle''"<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Gaedtke |first=Andrew |date=December 2009 |title=The Politics and Aesthetics of Disability: A Review of Michael Davidson's ''Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body'' |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2979/jml.2009.33.1.164 |journal=Journal of Modern Literature |volume=33 |issue=1 |pages=164–170 |doi=10.2979/jml.2009.33.1.164 |s2cid=146184141 |issn=0022-281X|url-access=subscription }}</ref> and "'']''" allowed audience for an anti-ableist reading which challenged stereotypes of disability. .<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fessas |first=Nikitas |date=2020-08-01 |title=Representations of Disability in 1960s Greek Film Noirs |url=http://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/journals/article/57763 |journal=Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies |language=en |volume=14 |issue=3 |pages=281–300 |doi=10.3828/jlcds.2020.18 |s2cid=225451304 |issn=1757-6466 |access-date=2022-06-06 |archive-date=2022-01-20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220120041539/https://liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/journals/article/57763/ |url-status=live |url-access=subscription }}</ref> | |||

| ]'' (1949), directed and cowritten by ], contains many cinematographic and narrative elements associated with classic American film noir.]] | |||

| Scholar Andrew Spicer argues that British film noir evidences a greater debt to French poetic realism than to the expressionistic American mode of noir.<ref>Spicer (2007), p. 9.</ref> Examples of British noir (sometimes described as "Brit noir") from the classic period include '']'' (1947), directed by ]; '']'' (1947), directed by ]; '']'' (1948), directed by ] and ]; '']'' (1947), directed by ]; and '']'' (1955), directed by ]. ] directed several low-budget thrillers in a noir mode for ], including '']'' (a.k.a. ''Man Bait''; 1952), '']'' (1952), and '']'' (a.k.a. ''Blackout''; 1954). Before leaving for France, Jules Dassin had been obliged by political pressure to shoot his last English-language film of the classic noir period in Great Britain: '']'' (1950). Though it was conceived in the United States and was not only directed by an American but also stars two American actors—] and ]—it is technically a UK production, financed by ]'s British subsidiary. The most famous of classic British noirs is director ]'s '']'' (1949), from a screenplay by ]. Set in Vienna immediately after World War II, it also stars two American actors, ] and ], who had appeared together in ''Citizen Kane''.<ref>Spicer (2007), pp. 16, 91–94, 96, 100; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 144, 249–55; Lyons (2000), p. 74, 81, 114–15.</ref> | |||

| Elsewhere, Italian director ] adapted Cain's ''The Postman Always Rings Twice'' as '']'' (1943), regarded both as one of the great noirs and a seminal film in the development of neorealism.<ref>Spicer (2007), pp. 13, 28, 241; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 264, 266.</ref> (This was not even the first screen version of Cain's novel, having been preceded by the French '']'' in 1939.)<ref>Spicer (2007), pp. 19 n. 36, 28.</ref> In Japan, the celebrated ] directed several films recognizable as films noir, including '']'' (1948), '']'' (1949), '']'' (1960), and '']'' (1963).<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 266–68.</ref> Spanish author Mercedes Formica's novel '']'' (The Lost City) was adapted into film in 1960.<ref>García López (2015), pp. 46–53.</ref> | |||

| Among the first major ] films—the term often applied to films that consciously refer back to the classic noir tradition—was the French '']'' (1960), directed by ] from a novel by one of the gloomiest of American noir fiction writers, ].<ref>Spicer (2007), p. 241; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 257.</ref> Noir crime films and melodramas have been produced in many countries in the post-classic area. Some of these are quintessentially self-aware neo-noirs—for example, '']'' (1969; Italy), '']'' (1977; Germany), '']'' (1984; Denmark), and '']'' (2005; Argentina). Others simply share narrative elements and a version of the hardboiled sensibility associated with classic noir, such as '']'' (1974; Japan), '']'' (1997; Norway), '']'' (1998; UK), and '']'' (2003; China).<ref>Ballinger and Graydon (2007), pp. 253, 255, 263–64, 266, 267, 270–74; Abbas (1997), p. 34.</ref> | |||

| ==Neo-noir and echoes of the classic mode== | ==Neo-noir and echoes of the classic mode== | ||

| {{See also|Neo-noir}} | |||

| ===The 1960s and 1970s=== | |||

| The neo-noir film genre developed mid-way into the Cold War. This cinematological trend reflected much of the cynicism and the possibility of nuclear annihilation of the era. This new genre introduced innovations that were not available to earlier noir films. The violence was also more potent.<ref name="Schwartz">{{cite web |url=http://chapters.scarecrowpress.com/08/108/081085676Xch1.pdf |title=Neo-Noir The New Film Noir Style from Psycho to Collateral |last=Schwartz |first=Ronald |publisher=The Scarecrow Press Inc. |year=2005 |access-date=2013-03-31|url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131104224706/http://chapters.scarecrowpress.com/08/108/081085676Xch1.pdf |archive-date=2013-11-04}}</ref> | |||

| While it is hard to draw a line between some of the noir films of the early 1960s such as ''Blast of Silence'' (1961) and '']'' (1962) and the noirs of the late 1950s, new trends emerged in the post-classic era. '']'' (1962), directed by ], '']'' (1962), directed by Samuel Fuller, and '']'' (1965), directed by experienced noir character actor ], all treat the theme of mental dispossession within stylistic and tonal frameworks derived from classic film noir. | |||

| ===1960s and 1970s=== | |||

| In a different vein, filmmakers such as ] (''Mickey One'' , clearly drawing inspiration from Truffaut's ''Tirez sur la pianiste'' and other ] films), ] ('']'' , similarly caught up, though in the '']''s deeper waters), and ] ('']'' ) directed movies that knowingly related themselves to the original film noirs, inviting audiences in on the game. Conscious acknowledgment of the classic era's conventions, as historical ] to be revived, rejected, or reimagined, is what puts the "neo" in neo-noir, according to many critics. Though several late classic noirs, ''Kiss Me Deadly'' in particular, were entirely self-knowing and post-traditional in conception, none that were top- or midbudgeted (like ]'s masterpiece) tipped its hand in a way noticeable to most audiences of the time. The first broadly popular crime drama of an unmistakabe neo-noir nature was not a movie, but the TV series '']'' (1958–61), created by ]. | |||

| While it is hard to draw a line between some of the noir films of the early 1960s such as '']'' (1961) and '']'' (1962) and the noirs of the late 1950s, new trends emerged in the post-classic era. '']'' (1962), directed by ], '']'' (1963), directed by ], and '']'' (1965), directed by experienced noir character actor ], all treat the theme of mental dispossession within stylistic and tonal frameworks derived from classic film noir.<ref name=u284286/> ''The Manchurian Candidate'' examined the situation of ] (POWs) during the ]. Incidents that occurred during the war as well as those post-war functioned as an inspiration for a "Cold War Noir" subgenre.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.koreanconfidential.com/koreanpowfilmnoir.html |title=Cold War Noir and the Other Films about Korean War POWs |access-date=2013-03-31|url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130218203603/http://www.koreanconfidential.com/koreanpowfilmnoir.html |last=Sautner|first=Mark|archive-date=2013-02-18}}</ref><ref name="Conway">{{cite web |url=http://www.articledestination.com/Article/Korean-War-Film-Noir--the-POW-Movies/12753 |title=Korean War Film Noir: the POW Movies |last=Conway |first=Marianne B. |access-date=2013-03-31 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130217064144/http://www.articledestination.com/Article/Korean-War-Film-Noir--the-POW-Movies/12753 |archive-date=2013-02-17}}</ref> The television series '']'' (1963–67) brought classic noir themes and mood to the small screen for an extended run.<ref name=u284286>Ursini (1995), pp. 284–86; Ballinger and Graydon (2007), p. 278.</ref> | |||

| ] does his best ] in '']'' (''Breathless''; 1960), written and directed by ] from a story by ].]] | |||

| ] in '']'' (''Breathless''; 1960). Poiccard reveres and styles himself after ]'s screen persona. Here he imitates a characteristic Bogart gesture, one of the film's ].<ref>Appel (1974), p. 4.</ref>]] | |||

| A manifest affiliation with noir traditions—which, by its nature, allows for different sorts of commentary on them to be inferred—can also provide the basis for explicit critiques of those traditions. The first major film to work this angle (that might be thought of as the most "neo" of "neo") was French director ]'s '']'' (''Breathless''; 1960), which pays its literal respects to Bogart and his crime films while brandishing a bold new style for a new day. In 1973, director ], who had worked on ''Peter Gunn'', flipped off noir piety with '']''. Based on the novel by Raymond Chandler, it features one of Bogart's most famous characters, but in ] fashion: Philip Marlowe, the prototypical hardboiled detective, is replayed as a hapless misfit, almost laughably out of touch with contemporary ] and morality. Where Altman's subversion of the film noir mythos was so irreverent as to anger many contemporary critics, around the same time Woody Allen was paying affectionate, at points idolatrous homage to the classic mode with '']'' (1972). | |||