| Revision as of 04:06, 16 March 2008 editFowler&fowler (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers63,218 edits →Revenue settlements under the Company: keystone of ryotwari← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:08, 16 March 2008 edit undoDesione (talk | contribs)1,226 edits Usual POV pushing without any discussionNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{POV-check}} | |||

| {{Infobox Former Country | {{Infobox Former Country | ||

| |native_name = | |native_name = | ||

| Line 28: | Line 29: | ||

| |image_flag = Flag of the British East India Company (1801).svg | |image_flag = Flag of the British East India Company (1801).svg | ||

| |flag = British East India Company#Flags|The flags of the British East India Company | |flag = British East India Company#Flags|The flags of the British East India Company | ||

| |image_map = |

|image_map = European settlements in India 1501-1739.png | ||

| |image_map_caption = |

|image_map_caption = British and other European settlements in India (1501-1739) | ||

| |capital = Calcutta | |capital = Calcutta | ||

| |national_motto = | |national_motto = | ||

| Line 45: | Line 46: | ||

| '''Company rule in India''', also '''Company Raj''' ("raj," lit. "rule" in ]), or the rule of the ] in India, was established after the ] in 1757, when the ] surrendered his dominions to the ]. The Company's rule in India lasted until 1858, when, consequent to the ], it was liquidated and the ] assumed direct control of the administration of ]. | '''Company rule in India''', also '''Company Raj''' ("raj," lit. "rule" in ]), or the rule of the ] in India, was established after the ] in 1757, when the ] surrendered his dominions to the ]. The Company's rule in India lasted until 1858, when, consequent to the ], it was liquidated and the ] assumed direct control of the administration of ]. | ||

| ==Prelude== | |||

| ==Expansion and territory== | |||

| The ] (hereafter, the Company) was founded in 1600, as ''The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies''. It gained footing in India in 1612, after ] emperor ] granted it the rights to establish a ''factory'' (a trading post) in ]. In 1640, consequent to receiving similar permission from the local ], a second factory was established in ]. Soon, in 1668, the Company leased ] island, a former Portuguese outpost recently gifted to ] in celebration of the wedding of ] to ]. Thereafter, in 1687, the company moved its headquarters from Surat to Bombay. Next, in 1690, a Company ''settlement'' was established in ], again after receiving such rights from of the ] emperor, and the Company now began its lengthy and far-flung presence on the ]. During this time, other ''companies'', established by the ], ], ], and ], were similarly expanding in the region. | |||

| The ] (hereafter, the Company) was incorporated on ], ] as ''The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies'' through a ] granted by ] of ]. In 1608, Company ships arrived in India and docked at port city of ], ]. In 1612, British traders battled the ] at the ], gaining the favour of the ] emperor ] who then granted the Company the rights to establish a ''factory'' (a trading post) in ]. In 1615, ] sent ] as his ambassador to Emperor Jahangir's court, which lead to a treaty allowing East India Company ''"freedom answerable to their own desires; to sell, buy, and to transport into their country at their pleasure"''.<ref></ref> In 1640, consequent to receiving similar permission from the local ], a second factory was established in ] (now ]). Soon, in 1668, the Company leased ] island (now ]), a former Portuguese outpost recently gifted to ] in celebration of the wedding of ] to ]. Thereafter, in 1687, the company moved its headquarters from Surat to Bombay. Next, in 1690, a Company ''settlement'' was established in ] (now ]) and the Company began its lengthy and far-flung presence on the ]. During this time, other ''companies'', established by the ], ], ], and ], were similarly expanding in the region. | |||

| ==1670 to 1770== | |||

| {{underconstruction}} | |||

| In 1670, ] granted the company the right to acquire territory, raise an army, mint its own money, and exercise legal jurisdiction in areas under its control. Taking advantage of a declining Mughal Empire after ]'s death in 1707 and warring provinces, the East India Company started to extend areas under its control. | |||

| In 1757, ], the ambitious commander in chief of the army of ], the ], secretly connived with the British asking for support to overthrow the Nawab in return for trade grants. At the ], Mir Jafar's forces betrayed the Nawab allowing the relatively small British force commanded by ] to win the battle. Jafar was installed on the throne of ] which became a British ]. Clive gained access to Bengal's treasury and netted £2.5m for the company and £234,000 for himself.<ref></ref> At the time, an average British nobleman could live a life of luxury on an annual income of £800.<ref></ref>. The battle transformed British perspective as they realised their strength and potential to conquer smaller Indian kingdoms, and marked the beginning of the imperial or colonial era. | |||

| A double system of government was then established in Bengal with administration, revenue collection, and justice under the nominal Nawab and the power to write bills against the treasury distributed among various company officials. This lead to a great deal of corruption enriching many in the company.<ref></ref> An ''unrequited trade'' involving use of India's own resources to fund exports to Britain was also created leading to a huge siphoning of wealth to Britain while impoverishing Bengal. Within a few years, India's historic positive balance of trade with Europe was gone.<ref></ref> | |||

| After defeating ] in ] (1764), the East India Company obtained right to collect taxes over much of eastern India (the regions currently occupied by Indian states of ], ], ], and ] along with the country of ]). In exchange, Shah Alam got an annual tribute of £300,000 and administrative rights over ] and ]. East India Company now directly administered a region with a population of 25 million and an annual revenue that was half of England's.<ref></ref> | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Within the next five years, revenues from land tax tripled leading to many farmers paying 2/3rd of their produce as tax - an unprecedented amount both by historical and modern standards. This tax was transferred to Britain in form of dividends to shareholders of East India Company and through unrequited trade. Unlike under the Mughals, when farmers were unable to pay taxes as a result of crop failure, their lands were auctioned off. | |||

| Although the British had earlier ruled in the factory areas, the beginning of British rule is often dated from the ] ]. ]'s victory was consolidated in ] at the ] (in ]), where the emperor, ], was defeated. As a result, Shah Alam was coerced to appoint the company to be the '']'' for the areas of ], Bihar, and ] (this pretense of ] control was abandoned in ]). The company thus became the supreme, but not the titular, power in much of the ], and company agents continued to trade on terms highly favorable to them. The Company also expanded from their bases at Bombay and Madras. The ] of ] to ] and the ] of ] to ] put the Company in control of most of India south of the ]. | |||

| {{cquote|''There were not five men of principle left in the Presidency'' - Robert Clive.<ref></ref>}} | |||

| The area controlled by the company expanded during the first three decades of the 19th century by two methods. The first was the use of '']'' between the British and the local rulers, under which control of foreign affairs, defense, and communications was transferred from the ruler to the Company, while the rulers retained limited dominion over internal affairs. This development created the ''Native States'', or ], of the Hindu ] and the Muslim ]s. The second method was outright military conquest or direct annexation of territories; it was these annexed areas that were properly called British India. Most of northern India was annexed by the British. | |||

| In early 1769, disregarding all warnings of an approaching drought,<ref></ref> the East India Company continued strict land tax enforcement, increasing land taxes in April 1770, and prevented hoarding of food grains by merchants anticipating higher prices during drought. Famines, as a result of fluctuating monsoon rains were not new to India; however, as a result of these policies and corrupt governance, what was expected to be a drought turned into a severe famine killing an unprecedented 10 million people (1/3rd of Bengal's population at the time) within a period of six months. Strict enforcement of land tax continued. In the year immediately following the famine, tax revenues collected by British East India Company increased as compared to the year immediately preceding the famine.<ref></ref> | |||

| == 1770 to 1857 == | |||

| At the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General ] began what became two decades of accelerated expansion of Company territories.<ref name=ludden-expansion>{{Harvnb|Ludden|2002|p=133}}</ref> Prominent among the princely states were: ] (1791), ] (1794), ] (1795), ] (1798), ] (1799), ] (1815), ] (1819), Kutch and Gujarat Gaikwad territories (1819), ] (1818), and ] (1833).<ref name=ludden-expansion/> The annexed regions included the ''Northwest Provinces'' (comprising ], ], and the ]) (1801), Delhi (1803), and ] (1843). ], ], and ], were annexed after the ] in 1849; however, Kashmir was immediately sold under the ] (1850) to the ] of ], and thereby became a princely state. In 1854 ] was annexed, and the state of ] two years later.<ref name=ludden-expansion/> | |||

| In 1773, the ] granted regulatory control over East India Company to the British government and established the post of ].<ref></ref> ] was appointed as the first Governor General of India. Later, in 1774, the British Parliament passed the ] which created a Board of Control overseeing the administration of East India Company.<ref></ref> During the proceedings of Pitt's India Act, ] was the lone parliamentarian who brought attention to what he perceived to be British East India Company misrule in India.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{cquote|''Every rupee of profit made by an Englishman is lost forever to India'' - ], British Parliamentarian, 1783<ref></ref>}} | |||

| The East India Company also signed treaties with Afghan rulers and with ] to counterbalance Russian support of ] plans in western ]. In 1839 the Company's actions brought about the ] (1839-42). However, as the British expanded their territory in India, so did ] in ], with the taking of ] and ] in 1863 and 1868 respectively, thereby setting the stage for the ] of ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Ludden|2002|p=135}}</ref> | |||

| Hastings, under pressure of East India Company directors to return profits, started to reorganise company operations. <ref></ref> | |||

| ==Policies== | |||

| He moved the administrative offices from ] to ], halved the stipend of titular Nawab of Bengal to £160,000, withdrew the tribute of £300,000 to ], and resold ] and ] to ]. | |||

| ] the first Governor-General of Company territories in India.]] | |||

| The British Parliament enacted a series of laws (see ]), beginning with the Regulating Act of 1773 which put limits on the Company's commercial activities as well as control over acquired territory. Limiting the company charter to periods of twenty years, subject to review upon renewal, the 1773 act gave the ] supervisory rights over the Bengal, ], and ] presidencies. The Regulating Act also created a unified administration for India, uniting the three presidencies under the authority of the Bengal's governor, who was elevated to the new position of ]. ] was the first incumbent (1773-1785). The India Act of 1784 sometimes described as the "half-loaf system," as it sought to mediate between Parliament and the company directors, enhanced Parliament's control by establishing the Board of Control, whose members were selected from the cabinet. | |||

| Hastings remained in India until 1784 and was succeeded by ], who initiated the Permanent Settlement, whereby an agreement in perpetuity was reached with ]s or landlords for the collection of revenue. For the next fifty years, the British were engaged in attempts to eliminate Indian rivals. | |||

| In the ], the British parliament renewed the Company's charter but terminated its monopoly, opening India both to private investment and missionaries.<ref name=ludden-expansion/> With increased British power in India supervision of Indian affairs by the ] and ] increased as well; by the 1820s British nationals could transact business or engage in missionary work under the protection of the Crown in the three Company ].<ref name=ludden-expansion/> With the ], the British parliament revoked the Company's trade license completely, making the Company a part of British governance, although the administration of British India remained the province of Company officers.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ludden|2002|p=134}}</ref> The Charter Act also recognized British ''moral responsibility'' for introducing "just and humane" laws in India, foreshadowing future social legislation, and outlawing a number of traditional practices such as '']'' and '']'' (or '']'', robbery coupled with ritual murder). The Charter Act of 1833 deprived the presidencies of the power to make laws, concentrating legislative power with the Governor-General and his council. | |||

| Further acts, such as the ] and the ], further defined the relationship of the Company and the British government. | |||

| ===Revenue settlements under the Company=== | |||

| {{underconstruction}} | |||

| {{main|Permanent Settlement|Zamindari|Ryotwari}} | |||

| ]), 1860.]] | |||

| ], the Governor-General who established the ] in ].]] | |||

| ]) shown with a broad-bladed agricultural knife and carrying a freshly harvested ]. Unknown photographer, 1860.]] | |||

| ], the Governor of ], who promoted '']'' settlements in the region.]] | |||

| In the remnant of the ] revenue system existing in pre-1765 Bengal, ]s collected revenue on behalf of the ] emperor, whose representative, or ] supervised their activities closely, with the stated goal of moderation in assessment. On being awarded the ''diwani'' or overlordship of Bengal following the ] in 1764, the ] found itself short of trained administrators, especially those familiar with local custom and law; tax collection was consequently ]. However, following the devastating famine of 1770, the importance of oversight of revenue officials was understood by the Company officials in Calcutta. | |||

| The Company also expanded from their bases at Bombay and Madras. The ] of ] to ] and the ] of ] to ] put the Company in control of most of India south of the ]. | |||

| In 1772, under Warren Hastings, the East India Company took over revenue collection directly in the ] (then ] and ]), establishing a Board of Revenue with offices in Calcutta and ], and moving the pre-existing Mughal revenue records from ] to Calcutta.<ref name=robb-revenue>{{Harvnb|Robb|2002|pp=126-129}} </ref> | |||

| In 1773, after ] ceded the tributary state of ], the revenue collection system was extended to the territory with a Company ] in charge.<ref name=robb-revenue/> The following year—with a view to preventing corruption—Company ''district collectors'', who were then responsible for revenue collection for an entire district, were replaced with provincial councils at Patna, Murshidabad, and Calcutta, and with Indian collectors working within each district.<ref name=robb-revenue/> The title, "collector," reflected "the centrality of land revenue collection to government in India: it was the government's primary function and it moulded the institutions and patterns of administration."<ref>{{Harvnb|Brown|1994|p=55}}</ref> | |||

| The area controlled by the company expanded during the first three decades of the 19th century by two methods. The first was the use of '']'' between the British and the local rulers, under which control of foreign affairs, defense, and communications was transferred from the ruler to the Company, while the rulers retained limited dominion over internal affairs. This development created the ''Native States'', or ], of the Hindu ] and the Muslim ]s. The second method was outright military conquest or direct annexation of territories; it was these annexed areas that were properly called British India. Most of northern India was annexed by the British. | |||

| The Company inherited a revenue collection system from the Mughals in which the heaviest proportion of the tax burden fell on the cultivators, with one-third of the production reserved for imperial entitlement; this pre-colonial system became the Company revenue policy's baseline.<ref name = peers-p45-47>{{Harvnb|Peers|2006|pp=45-47}}</ref> However, there was vast variation across India in the methods by which the revenues were collected; with this complication in mind, a Committee of Circuit toured the districts of expanded Bengal presidency in order to make a five-year settlement, consisting of five-yearly inspections and temporary ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Peers|2006|pp=45-47}}, {{Harvnb|Robb|2002|pp=126-129}} </ref> In their overall approach to revenue policy, Company officials were guided by two goals: first, preserving as much as possible the balance of rights and obligations that were traditionally claimed by the farmers who cultivated the land and the various intermediaries who collected tax on the state's behalf and who reserved a cut for themselves; and second, identifying those sectors of the rural economy that would maximize both revenue and security.<ref name = peers-p45-47/> Although their first revenue settlement turned out to be essentially the same as the more informal pre-existing Mughal one, the Company had created a foundation for the growth of both information and bureaucracy.<ref name=peers-p45-47/> | |||

| At the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General ] began what became two decades of accelerated expansion of Company territories.<ref name=ludden-expansion>{{Harvnb|Ludden|2002|p=133}}</ref> Prominent among the princely states were: ] (1791), ] (1794), ] (1795), ] (1798), ] (1799), ] (1815), ] (1819), Kutch and Gujarat Gaikwad territories (1819), ] (1818), and ] (1833).<ref name=ludden-expansion/> The annexed regions included the ''Northwest Provinces'' (comprising ], ], and the ]) (1801), Delhi (1803), and ] (1843). ], ], and ], were annexed after the ] in 1849; however, Kashmir was immediately sold under the ] (1850) to the ] of ], and thereby became a princely state. In 1854 ] was annexed, and the state of ] two years later.<ref name=ludden-expansion/> | |||

| At the start of the 19th century, most of present-day Pakistan was under independent rulers. Sindh was ruled by the Muslim ]s (chiefs) in three small states that were annexed by the British in ]. In Punjab, the decline of the Mughal Empire allowed the rise of the ]s, first as a military force and later as a political administration in ]. The kingdom of Lahore was at its most powerful and expansive during the rule of Maharaja ], when Sikh control was extended beyond ], and ] was added to his dominions in 1819. After Ranjit Singh died in 1839, political conditions in Punjab deteriorated, and the British fought two wars with the Sikhs. The second of these wars, in 1849, saw the annexation of Punjab, including the present-day ], to the company's territories. Kashmir was transferred by sale in the ] in 1850 to the ], which ruled the area under British paramountcy until 1947. | |||

| In 1793, the new Governor-General, ], promulgated the ] of land revenues in the presidency, the first socio-economic regulation in colonial India.<ref name=robb-revenue/> It was named ''permanent'' because it fixed the land tax in perpetuity in return for landed property rights for ]; it simultaneously defined the nature of land ownership in the presidency, and gave individuals and families separate property rights in occupied land. Over the next century, partly as a result of land surveys, court rulings, and property sales, the change was given practical dimension.<ref>{{Harvnb|Robb|2002|p=127}}</ref> An influence on the development of this revenue policy were the economic theories then current, which regarded agriculture as the engine of economic development, and consequently stressed the fixing of revenue demands in order to encourage growth.<ref>{{Harvnb|Guha|1995}}</ref> The expectation behind the permanent settlement was that knowledge of a fixed government demand would encourage the zamindars to increase both their average outcrop and the land under cultivation, since they would be able to retain the profits from the increased output; in addition, it was envisaged that land itself would become a marketable form of property that could be purchased, sold, or mortgaged.<ref name=peers-p45-47/> A feature of this economic rationale was the additional expectation that the zamindars, recognizing their own best interest, would not make unreasonable demands on the peasantry.<ref name=bose-ps>{{Harvnb|Bose|1993}}</ref> | |||

| In Punjab, annexed in 1849, a group of extraordinarily able British officers, serving first the Company and then the British Crown, governed the area. They avoided the administrative mistakes made earlier in Bengal. A number of reforms were introduced, although local customs were generally respected. Irrigation projects later in the century helped Punjab become the granary of northern India. The respect gained by the new administration could be gauged by the fact that within ten years Punjabi troops were fighting for the British elsewhere in India to subdue the ]. Punjab was to become the major recruiting area for the British Indian Army, recruiting both ] and Muslims. | |||

| However, these expectations were not realized in practice, and in many regions of Bengal, the peasants bore the brunt of the increased demand, there being little protection for their traditional rights in the new legislation.<ref name=bose-ps/> Forced labor of the peasants by the zamindars became more prevalent as cash crops were cultivated to meet the Company revenue demands.<ref name=peers-p45-47/> Although commercialized cultivation was not new to the region, it had now penetrated deeper into village society and made it more vulnerable to market forces.<ref name=peers-p45-47/> The zamindars themselves were often unable to meet the increased demands that the Company had placed on them; consequently, many defaulted, and by one estimate, up to one-third of their lands were auctioned during the first three decades following the permanent settlement.<ref>{{Harvnb|Tomlinson|1993|p=43}}</ref> The new owners were often ] and ] employees of the Company who had a good grasp of the new system, and, in many cases, had prospered under it.<ref name=metcalf-revenue>{{Harvnb|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p=79}}</ref> | |||

| ==Motives== | |||

| Since the zamindars were never able to undertake costly improvements to the land envisaged under the Permanent Settlement, some of which required the removal of the existing farmers, they soon became rentiers who lived off the rent from their tenant farmers.<ref name=metcalf-revenue/> In many areas, especially northern Bengal, they had to increasingly share the revenue with intermediate tenure holders, called ''jotedars'', who supervised farming in the villages.<ref name=metcalf-revenue/> Consequently, unlike the contemporaneous ] in Britain, agriculture in Bengal remained the province of the subsistence farming of innumerable small ] fields.<ref name=metcalf-revenue/> | |||

| A multiplicity of motives underlay the British penetration into ]: commerce, security, and a purported moral upliftment of the people. The "expansive force" of private and company trade eventually led to the conquest or annexation of territories in which ]s, ], and ] were produced. British investors ventured into the unfamiliar interior landscape in search of opportunities that promised substantial profits. British economic penetration was aided by Indian collaborators, such as the bankers and merchants who controlled intricate credit networks already present in India. British rule in India would have been a frustrated or half-realized dream had not Indian counterparts provided connections between rural and urban centers. External threats, both real and imagined, such as the ] (1796-1815) and Russian expansion toward Afghanistan (in the 1830s), as well as the desire for internal stability, led to the annexation of more territory in India. Political analysts in Britain wavered initially as they were uncertain of the costs or the advantages in undertaking wars in India, but by the 1810s, as the territorial aggrandizement eventually paid off, opinion in ] welcomed the absorption of new areas. Occasionally the ] witnessed heated debates against expansion, but arguments justifying military operations for security reasons always won over even the most vehement critics. | |||

| The British soon forgot their own rivalry with the ] and the ] and permitted them to stay in their coastal enclaves, which they kept even after independence in 1947. The British, however, continued to expand vigorously well into the ]. A number of aggressive ] undertook relentless campaigns against several ] and ] rulers. Among them were ] (1798-1805), ] (1823-1828), ] (1836-1842), ] (1842-1844), and ] (1848-1856; also known as the Marquess of Dalhousie). Despite desperate efforts at salvaging their tottering power and keeping the British at bay, many Hindu and Muslim rulers lost their territories: ] (1799, but later restored), the ] (1818)(see ]), and Punjab (1849). The British success in large measure was the result not only of their superiority in tactics and weapons but also of their ingenious relations with Indian rulers through the "subsidiary alliance" system, introduced in the early 19th century. Many rulers bartered away their real responsibilities by agreeing to uphold British paramountcy in India, while they retained a fictional sovereignty under the rubric of ]. Later, Dalhousie espoused the "doctrine of lapse" and annexed outright the estates of deceased princes of ] (1848), ] (1852), ] (1853), ] (1853), ] (1854), and ] (1856). | |||

| European perceptions of India, and those of the British especially, shifted from unequivocal appreciation to sweeping condemnation of India's past achievements and customs. Imbued with an ] sense of superiority, often known as the ], British intellectuals, including ] ], spearheaded a movement that sought to bring Western intellectual and technological innovations to Indians, ignoring the fact that the Indian Christian tradition through the ] went back to the very beginnings of first century Christian thought. | |||

| Interpretations of the causes of India's cultural and spiritual "backwardness" varied, as did the solutions. Many argued that it was Europe's mission to civilize India and hold it as a trust until Indians proved themselves "competent" for self-rule. The immediate consequence of this sense of superiority was to open India to more missionary activity. The contributions of three missionaries based in ] (a ] enclave in Bengal) - ], ], and ] - remained unequaled and have provided inspiration for future generations of their successors. | |||

| ==Policies== | |||

| The British Parliament enacted a series of laws (see ]), among which the Regulating Act of 1773 stood first, to curb the company traders' unrestrained commercial activities and to bring about some order in territories under company control. Limiting the company charter to periods of twenty years, subject to review upon renewal, the 1773 act gave the ] supervisory rights over the Bengal, ], and ] presidencies. The Regulating Act also created a unified administration for India, uniting the three presidencies under the authority of the Bengal's governor, who was elevated to the new position of governor-general. Bengal was given preeminence over the others because of its enormous commercial vitality, and ] became the seat of British power in India. ] was the first incumbent (1773-1785). The India Act of 1784 sometimes described as the "half-loaf system," as it sought to mediate between Parliament and the company directors, enhanced Parliament's control by establishing the Board of Control, whose members were selected from the cabinet. The Charter Act of 1813 recognized British moral responsibility by introducing just and humane laws in India, foreshadowing future social legislation, and outlawing a number of traditional practices such as '']'' and '']'' (or '']'', robbery coupled with ritual murder). The Charter Act of 1833 deprived the presidencies of the power to make laws, concentrating legislative power with the Governor-General and his council. | |||

| The zamindari system was one of three principal revenue settlements that were employed by the Company in India.<ref>{{Harvnb|Roy|2000|pp=37-42}}</ref> In southern India, ], who would later become Governor of ], promoted the '']'' system, in which the government settled land-revenue directly with the peasant farmers, or ''ryots''.<ref name=peers47>{{Harvnb|Peers|2006|p=47}}</ref> This was, in part, a consequence of the turmoil of the ], which had prevented the emergence of a class of large landowners; in addition, Munro and others felt that ''ryotwari'' was closer to traditional practice in the region and ideologically more progressive, allowing the benefits of Company rule to reach the lowest levels of rural society.<ref name=peers47/> The keystone of the new system of temporary settlements was the classification of agricultural fields according to soil type and produce, with average rent rates fixed for the period of the settlement.<ref>{{Harvnb|Robb|2002|p=128}}</ref> However, in spite of the appeal of the ''ryotwari'' system's abstract principles, class hierarchies in southern Indian villages had not entirely disappeared, and peasant cultivators sometimes came to experience revenue demands they could not meet.<ref name=peers47/> In the 1850s, a scandal erupted when it was discovered that some Indian revenue agents of the Company were using torture to meet the Company's revenue demands.<ref name=peers47/> | |||

| As governor-general from 1786 to 1793, ] (the Marquis of Cornwallis), professionalized, bureaucratized, and Europeanized the company's administration. He also outlawed private trade by company employees, separated the commercial and administrative functions, and remunerated company servants with generous graduated salaries. Because revenue collection became the company's most essential administrative function, Cornwallis made a compact with ]i ]s, who were perceived as the Indian counterparts to the British landed gentry. The Permanent Settlement system, also known as the ], fixed taxes in perpetuity in return for ownership of large estates; but the state was excluded from agricultural expansion, which came under the purview of the zamindars. In Madras and Bombay, however, the '']'' (peasant) settlement system was set in motion, in which peasant cultivators had to pay annual taxes directly to the government. | |||

| ===Trade: 1770-1860=== | |||

| Neither the zamindari nor the ryotwari systems proved effective in the long run because India was integrated into an international economic and pricing system over which it had no control, while increasing numbers of people subsisted on agriculture for lack of other employment. Millions of people involved in the heavily taxed Indian textile industry also lost their markets, as they were unable to compete successfully with cheaper textiles produced in ]'s mills from Indian raw materials. | Neither the zamindari nor the ryotwari systems proved effective in the long run because India was integrated into an international economic and pricing system over which it had no control, while increasing numbers of people subsisted on agriculture for lack of other employment. Millions of people involved in the heavily taxed Indian textile industry also lost their markets, as they were unable to compete successfully with cheaper textiles produced in ]'s mills from Indian raw materials. | ||

| ===Law=== | |||

| Beginning with the ], established in 1727 for civil litigation in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, justice in the interior came under the company's jurisdiction. In 1772 an elaborate judicial system, known as '']'', established civil and criminal jurisdictions along with a complex set of codes or rules of procedure and evidence. Both Hindu ] and Muslim qazis (] court judges) were recruited to aid the presiding judges in interpreting their customary laws, but in other instances, British common and statutory laws became applicable. In extraordinary situations where none of these systems was applicable, the judges were enjoined to adjudicate on the basis of "justice, equity, and good conscience." The legal profession provided numerous opportunities for educated and talented Indians who were unable to secure positions in the company, and, as a result, Indian lawyers later dominated nationalist politics and reform movements. | Beginning with the ], established in 1727 for civil litigation in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, justice in the interior came under the company's jurisdiction. In 1772 an elaborate judicial system, known as '']'', established civil and criminal jurisdictions along with a complex set of codes or rules of procedure and evidence. Both Hindu ] and Muslim qazis (] court judges) were recruited to aid the presiding judges in interpreting their customary laws, but in other instances, British common and statutory laws became applicable. In extraordinary situations where none of these systems was applicable, the judges were enjoined to adjudicate on the basis of "justice, equity, and good conscience." The legal profession provided numerous opportunities for educated and talented Indians who were unable to secure positions in the company, and, as a result, Indian lawyers later dominated nationalist politics and reform movements. | ||

| ===Education=== | |||

| Education for the most part was left to the charge of Indians or to private agents who imparted instruction in the vernaculars. But in 1813, the British became convinced of their "duty" to awaken the Indians from intellectual slumber by exposing them to British literary traditions, earmarking a paltry sum for the cause. Controversy between two groups of Europeans - the "]s" and "Anglicists" - over how the money was to be spent prevented them from formulating any consistent policy until 1835 when ], the governor-general from 1828 to 1835, finally broke the impasse by resolving to introduce the ] as the medium of instruction. English replaced ] in public administration and education. | Education for the most part was left to the charge of Indians or to private agents who imparted instruction in the vernaculars. But in 1813, the British became convinced of their "duty" to awaken the Indians from intellectual slumber by exposing them to British literary traditions, earmarking a paltry sum for the cause. Controversy between two groups of Europeans - the "]s" and "Anglicists" - over how the money was to be spent prevented them from formulating any consistent policy until 1835 when ], the governor-general from 1828 to 1835, finally broke the impasse by resolving to introduce the ] as the medium of instruction. English replaced ] in public administration and education. | ||

| ===Social Reform=== | |||

| The company's education policies in the 1830s tended to reinforce existing lines of socioeconomic division in society rather than bringing general liberation from ignorance and superstition. Whereas the Hindu English-educated minority spearheaded many social and religious reforms either in direct response to government policies or in reaction to them, Muslims as a group initially failed to do so, a position they endeavored to reverse. Western-educated Hindu elites sought to rid Hinduism of its much criticized social evils: the ], child marriage, and ''sati''. Religious and social activist ] (1772-1833), who founded the ] (Society of Brahma) in 1828, displayed a readiness to synthesize themes taken from Christianity, ], and ], while other individuals in Bombay and Madras initiated literary and debating societies that gave them a forum for open discourse. The exemplary educational attainments and skillful use of the press by these early reformers enhanced the possibility of effecting broad reforms without compromising societal values or religious practices. | The company's education policies in the 1830s tended to reinforce existing lines of socioeconomic division in society rather than bringing general liberation from ignorance and superstition. Whereas the Hindu English-educated minority spearheaded many social and religious reforms either in direct response to government policies or in reaction to them, Muslims as a group initially failed to do so, a position they endeavored to reverse. Western-educated Hindu elites sought to rid Hinduism of its much criticized social evils: the ], child marriage, and ''sati''. Religious and social activist ] (1772-1833), who founded the ] (Society of Brahma) in 1828, displayed a readiness to synthesize themes taken from Christianity, ], and ], while other individuals in Bombay and Madras initiated literary and debating societies that gave them a forum for open discourse. The exemplary educational attainments and skillful use of the press by these early reformers enhanced the possibility of effecting broad reforms without compromising societal values or religious practices. | ||

| ===Infrastructure Development=== | |||

| The 1850s witnessed the introduction of the three "engines of social improvement" that heightened the British illusion of permanence in India. They were the ]s, the ], and the uniform ], inaugurated during the tenure of Dalhousie as governor-general. The first railroad lines were built in 1850 from Howrah (], across the ] from ]) inland to the coalfields at ], Bihar, a distance of 240 kilometers. In 1851 the first electric telegraph line was laid in Bengal and soon linked ], Bombay, Calcutta, Lahore, ], and other cities. The three different presidency or regional postal systems merged in 1854 to facilitate uniform methods of communication at an all-India level. With uniform postal rates for letters and newspapers - one-half anna and one anna, respectively (sixteen annas equalled one ]) - communication between the rural and the metropolitan areas became easier and faster. The increased ease of communication and the opening of highways and waterways accelerated the movement of troops, the transportation of raw materials and goods to and from the interior, and the exchange of commercial information. | The 1850s witnessed the introduction of the three "engines of social improvement" that heightened the British illusion of permanence in India. They were the ]s, the ], and the uniform ], inaugurated during the tenure of Dalhousie as governor-general. The first railroad lines were built in 1850 from Howrah (], across the ] from ]) inland to the coalfields at ], Bihar, a distance of 240 kilometers. In 1851 the first electric telegraph line was laid in Bengal and soon linked ], Bombay, Calcutta, Lahore, ], and other cities. The three different presidency or regional postal systems merged in 1854 to facilitate uniform methods of communication at an all-India level. With uniform postal rates for letters and newspapers - one-half anna and one anna, respectively (sixteen annas equalled one ]) - communication between the rural and the metropolitan areas became easier and faster. The increased ease of communication and the opening of highways and waterways accelerated the movement of troops, the transportation of raw materials and goods to and from the interior, and the exchange of commercial information. | ||

| The railroads did not break down the social or cultural distances between various groups but tended to create new categories in travel. Separate compartments in the trains were reserved exclusively for the ruling class, separating the educated and wealthy from ordinary people. Similarly, when the Sepoy Rebellion was quelled in ], a British official exclaimed that "the telegraph saved India." He envisaged, of course, that British interests in India would continue indefinitely. | The railroads did not break down the social or cultural distances between various groups but tended to create new categories in travel. Separate compartments in the trains were reserved exclusively for the ruling class, separating the educated and wealthy from ordinary people. Similarly, when the Sepoy Rebellion was quelled in ], a British official exclaimed that "the telegraph saved India." He envisaged, of course, that British interests in India would continue indefinitely. | ||

| ==Features of Company Rule== | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 288: | Line 298: | ||

| | url= | | url= | ||

| }}. | }}. | ||

| *{{Harvard reference | |||

| | last1=Bose | |||

| | first1=Sumit | |||

| | authorlink1= | |||

| | year=1993 | |||

| | title=Peasant Labour and Colonial Capital: Rural Bengal since 1770 (New Cambridge History of India) | |||

| | place= | |||

| | publisher=Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. | |||

| | isbn= | |||

| | url= | |||

| }}. | |||

| *{{Harvard reference| last1=Bayly| first1=C. A. | authorlink1=Christopher Alan Bayly | *{{Harvard reference| last1=Bayly| first1=C. A. | authorlink1=Christopher Alan Bayly | ||

| | year=2000| title=Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 (Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society)| place=| publisher=Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 426| isbn=0521663601| url=}} | | year=2000| title=Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 (Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society)| place=| publisher=Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 426| isbn=0521663601| url=}} | ||

| Line 311: | Line 310: | ||

| | isbn=0521596920 | | isbn=0521596920 | ||

| | url=http://www.amazon.com/Imperial-Power-Popular-Politics-Resistance/dp/0521596920/ | | url=http://www.amazon.com/Imperial-Power-Popular-Politics-Resistance/dp/0521596920/ | ||

| }}. | |||

| *{{Harvard reference | |||

| | last1=Guha | |||

| | first1=R. | |||

| | authorlink= | |||

| | year=1995 | |||

| | title=A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of the Permanent Settlement | |||

| | place= | |||

| | publisher=Durham, NC: Duke University Press | |||

| | isbn=0521596920 | |||

| | url= | |||

| }}. | }}. | ||

| *{{Harvard reference | *{{Harvard reference | ||

| Line 336: | Line 324: | ||

| *{{Harvard reference | last = Metcalf | first = Thomas R. | year = 1997 | title = Ideologies of the Raj | publisher = Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press, Pp. 256 | isbn = 0521589371}} | *{{Harvard reference | last = Metcalf | first = Thomas R. | year = 1997 | title = Ideologies of the Raj | publisher = Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press, Pp. 256 | isbn = 0521589371}} | ||

| *{{Harvard reference | last = Porter | first = Andrew (ed.) | year = 2001 | title = Oxford History of the British Empire: Nineteenth Century | publisher = Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 800 | isbn = 0199246785 | url = http://www.amazon.com/Oxford-History-British-Empire-Nineteenth/dp/0199246785}} | *{{Harvard reference | last = Porter | first = Andrew (ed.) | year = 2001 | title = Oxford History of the British Empire: Nineteenth Century | publisher = Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 800 | isbn = 0199246785 | url = http://www.amazon.com/Oxford-History-British-Empire-Nineteenth/dp/0199246785}} | ||

| *{{Harvard reference | |||

| | last1=Tomlinson | |||

| | first1=B. R. | |||

| | authorlink1= | |||

| | year=1993 | |||

| | title=The Economy of Modern India, 1860-1970 (The New Cambridge History of India, III.3) | |||

| | place= | |||

| | publisher=Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. | |||

| | isbn= | |||

| | url= | |||

| }}. | |||

| ===Articles in Journals or Collections=== | ===Articles in Journals or Collections=== | ||

Revision as of 04:08, 16 March 2008

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| British India | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1757–1858 | |||||||

Flag

Flag | |||||||

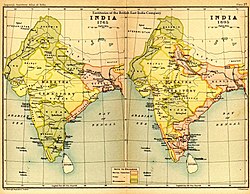

British and other European settlements in India (1501-1739) British and other European settlements in India (1501-1739) | |||||||

| Status | British colony | ||||||

| Capital | Calcutta | ||||||

| Common languages | English and many others | ||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||

| • 1774-1775 | Warren Hastings | ||||||

| • 1857-1858 | The Viscount Canning | ||||||

| History | |||||||

| • Battle of Plassey | June 23 1757 | ||||||

| • Third Anglo-Maratha War | 1817-1818 | ||||||

| • Indian Rebellion | 1857 | ||||||

| • Government of India Act | August 2 1858 | ||||||

| Currency | British Indian rupee | ||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IN | ||||||

| |||||||

Company rule in India, also Company Raj ("raj," lit. "rule" in Sanskrit), or the rule of the British East India Company in India, was established after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, when the Nawab of Bengal surrendered his dominions to the British East India Company. The Company's rule in India lasted until 1858, when, consequent to the Government of India Act 1858, it was liquidated and the British Crown assumed direct control of the administration of India.

Prelude

The British East India Company (hereafter, the Company) was incorporated on 31 December, 1600 as The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies through a royal charter granted by Queen Elizabeth I of England. In 1608, Company ships arrived in India and docked at port city of Surat, Gujarat. In 1612, British traders battled the Portuguese at the Battle of Swally, gaining the favour of the Mughal emperor Jahangir who then granted the Company the rights to establish a factory (a trading post) in Surat. In 1615, King James I sent Sir Thomas Roe as his ambassador to Emperor Jahangir's court, which lead to a treaty allowing East India Company "freedom answerable to their own desires; to sell, buy, and to transport into their country at their pleasure". In 1640, consequent to receiving similar permission from the local Vijayanagara ruler, a second factory was established in Madras (now Chennai). Soon, in 1668, the Company leased Bombay island (now Mumbai), a former Portuguese outpost recently gifted to Great Britain in celebration of the wedding of Charles II of England to Catherine of Braganza. Thereafter, in 1687, the company moved its headquarters from Surat to Bombay. Next, in 1690, a Company settlement was established in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and the Company began its lengthy and far-flung presence on the Indian subcontinent. During this time, other companies, established by the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and Danish, were similarly expanding in the region.

1670 to 1770

| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Desione (talk | contribs) 16 years ago. (Update timer) |

In 1670, King Charles II granted the company the right to acquire territory, raise an army, mint its own money, and exercise legal jurisdiction in areas under its control. Taking advantage of a declining Mughal Empire after Aurangzeb's death in 1707 and warring provinces, the East India Company started to extend areas under its control.

In 1757, Mir Jafar, the ambitious commander in chief of the army of Siraj Ud Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, secretly connived with the British asking for support to overthrow the Nawab in return for trade grants. At the Battle of Plassey, Mir Jafar's forces betrayed the Nawab allowing the relatively small British force commanded by Robert Clive to win the battle. Jafar was installed on the throne of Bengal which became a British protectorate. Clive gained access to Bengal's treasury and netted £2.5m for the company and £234,000 for himself. At the time, an average British nobleman could live a life of luxury on an annual income of £800.. The battle transformed British perspective as they realised their strength and potential to conquer smaller Indian kingdoms, and marked the beginning of the imperial or colonial era.

A double system of government was then established in Bengal with administration, revenue collection, and justice under the nominal Nawab and the power to write bills against the treasury distributed among various company officials. This lead to a great deal of corruption enriching many in the company. An unrequited trade involving use of India's own resources to fund exports to Britain was also created leading to a huge siphoning of wealth to Britain while impoverishing Bengal. Within a few years, India's historic positive balance of trade with Europe was gone.

After defeating Shah Alam II in Battle of Buxar (1764), the East India Company obtained right to collect taxes over much of eastern India (the regions currently occupied by Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa, and West Bengal along with the country of Bangladesh). In exchange, Shah Alam got an annual tribute of £300,000 and administrative rights over Allahabad and Kora. East India Company now directly administered a region with a population of 25 million and an annual revenue that was half of England's.

Within the next five years, revenues from land tax tripled leading to many farmers paying 2/3rd of their produce as tax - an unprecedented amount both by historical and modern standards. This tax was transferred to Britain in form of dividends to shareholders of East India Company and through unrequited trade. Unlike under the Mughals, when farmers were unable to pay taxes as a result of crop failure, their lands were auctioned off.

There were not five men of principle left in the Presidency - Robert Clive.

In early 1769, disregarding all warnings of an approaching drought, the East India Company continued strict land tax enforcement, increasing land taxes in April 1770, and prevented hoarding of food grains by merchants anticipating higher prices during drought. Famines, as a result of fluctuating monsoon rains were not new to India; however, as a result of these policies and corrupt governance, what was expected to be a drought turned into a severe famine killing an unprecedented 10 million people (1/3rd of Bengal's population at the time) within a period of six months. Strict enforcement of land tax continued. In the year immediately following the famine, tax revenues collected by British East India Company increased as compared to the year immediately preceding the famine.

1770 to 1857

In 1773, the British Parliament granted regulatory control over East India Company to the British government and established the post of Governor-General of India. Warren Hastings was appointed as the first Governor General of India. Later, in 1774, the British Parliament passed the Pitt's India Act which created a Board of Control overseeing the administration of East India Company. During the proceedings of Pitt's India Act, Edmund Burke was the lone parliamentarian who brought attention to what he perceived to be British East India Company misrule in India.

Every rupee of profit made by an Englishman is lost forever to India - Edmund Burke, British Parliamentarian, 1783

Hastings, under pressure of East India Company directors to return profits, started to reorganise company operations. He moved the administrative offices from Murshidabad to Calcutta, halved the stipend of titular Nawab of Bengal to £160,000, withdrew the tribute of £300,000 to Shah Alam II, and resold Allahabad and Kora to Oudh.

Hastings remained in India until 1784 and was succeeded by Cornwallis, who initiated the Permanent Settlement, whereby an agreement in perpetuity was reached with zamindars or landlords for the collection of revenue. For the next fifty years, the British were engaged in attempts to eliminate Indian rivals.

Further acts, such as the Charter Act of 1813 and the Charter Act of 1833, further defined the relationship of the Company and the British government.

The Company also expanded from their bases at Bombay and Madras. The Anglo-Mysore Wars of 1766 to 1799 and the Anglo-Maratha Wars of 1772 to 1818 put the Company in control of most of India south of the Sutlej River.

The area controlled by the company expanded during the first three decades of the 19th century by two methods. The first was the use of subsidiary alliances between the British and the local rulers, under which control of foreign affairs, defense, and communications was transferred from the ruler to the Company, while the rulers retained limited dominion over internal affairs. This development created the Native States, or Princely States, of the Hindu maharaja and the Muslim nawabs. The second method was outright military conquest or direct annexation of territories; it was these annexed areas that were properly called British India. Most of northern India was annexed by the British. At the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General Wellesley began what became two decades of accelerated expansion of Company territories. Prominent among the princely states were: Cochin (1791), Jaipur (1794), Travancore (1795), Hyderabad (1798), Mysore (1799), Cis-Sutlej Hill States (1815), Central India Agency (1819), Kutch and Gujarat Gaikwad territories (1819), Rajputana (1818), and Bahawalpur (1833). The annexed regions included the Northwest Provinces (comprising Rohilkhand, Gorakhpur, and the Doab) (1801), Delhi (1803), and Sindh (1843). Punjab, Northwest Frontier Province, and Kashmir, were annexed after the Anglo-Sikh Wars in 1849; however, Kashmir was immediately sold under the Treaty of Amritsar (1850) to the Dogra Dynasty of Jammu, and thereby became a princely state. In 1854 Berar was annexed, and the state of Oudh two years later.

At the start of the 19th century, most of present-day Pakistan was under independent rulers. Sindh was ruled by the Muslim Talpur mirs (chiefs) in three small states that were annexed by the British in 1843. In Punjab, the decline of the Mughal Empire allowed the rise of the Sikhs, first as a military force and later as a political administration in Lahore. The kingdom of Lahore was at its most powerful and expansive during the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, when Sikh control was extended beyond Peshawar, and Kashmir was added to his dominions in 1819. After Ranjit Singh died in 1839, political conditions in Punjab deteriorated, and the British fought two wars with the Sikhs. The second of these wars, in 1849, saw the annexation of Punjab, including the present-day North-West Frontier Province, to the company's territories. Kashmir was transferred by sale in the Treaty of Amritsar in 1850 to the Dogra Dynasty, which ruled the area under British paramountcy until 1947.

In Punjab, annexed in 1849, a group of extraordinarily able British officers, serving first the Company and then the British Crown, governed the area. They avoided the administrative mistakes made earlier in Bengal. A number of reforms were introduced, although local customs were generally respected. Irrigation projects later in the century helped Punjab become the granary of northern India. The respect gained by the new administration could be gauged by the fact that within ten years Punjabi troops were fighting for the British elsewhere in India to subdue the uprising of 1857-1858. Punjab was to become the major recruiting area for the British Indian Army, recruiting both Sikhs and Muslims.

Motives

A multiplicity of motives underlay the British penetration into India: commerce, security, and a purported moral upliftment of the people. The "expansive force" of private and company trade eventually led to the conquest or annexation of territories in which spices, cotton, and opium were produced. British investors ventured into the unfamiliar interior landscape in search of opportunities that promised substantial profits. British economic penetration was aided by Indian collaborators, such as the bankers and merchants who controlled intricate credit networks already present in India. British rule in India would have been a frustrated or half-realized dream had not Indian counterparts provided connections between rural and urban centers. External threats, both real and imagined, such as the Napoleonic Wars (1796-1815) and Russian expansion toward Afghanistan (in the 1830s), as well as the desire for internal stability, led to the annexation of more territory in India. Political analysts in Britain wavered initially as they were uncertain of the costs or the advantages in undertaking wars in India, but by the 1810s, as the territorial aggrandizement eventually paid off, opinion in London welcomed the absorption of new areas. Occasionally the British Parliament witnessed heated debates against expansion, but arguments justifying military operations for security reasons always won over even the most vehement critics.

The British soon forgot their own rivalry with the Portuguese and the French and permitted them to stay in their coastal enclaves, which they kept even after independence in 1947. The British, however, continued to expand vigorously well into the 1850s. A number of aggressive governors-general undertook relentless campaigns against several Hindu and Muslim rulers. Among them were Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley (1798-1805), William Pitt Amherst (1823-1828), George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland (1836-1842), Edward Law, 1st Earl of Ellenborough (1842-1844), and James Andrew Brown Ramsay, 11th Earl of Dalhousie (1848-1856; also known as the Marquess of Dalhousie). Despite desperate efforts at salvaging their tottering power and keeping the British at bay, many Hindu and Muslim rulers lost their territories: Mysore (1799, but later restored), the Maratha Confederacy (1818)(see Battle of Khadki), and Punjab (1849). The British success in large measure was the result not only of their superiority in tactics and weapons but also of their ingenious relations with Indian rulers through the "subsidiary alliance" system, introduced in the early 19th century. Many rulers bartered away their real responsibilities by agreeing to uphold British paramountcy in India, while they retained a fictional sovereignty under the rubric of Pax Britannica. Later, Dalhousie espoused the "doctrine of lapse" and annexed outright the estates of deceased princes of Satara (1848), Udaipur (1852), Jhansi (1853), Tanjore (1853), Nagpur (1854), and Oudh (1856).

European perceptions of India, and those of the British especially, shifted from unequivocal appreciation to sweeping condemnation of India's past achievements and customs. Imbued with an ethnocentric sense of superiority, often known as the White Man's Burden, British intellectuals, including Christian missionaries, spearheaded a movement that sought to bring Western intellectual and technological innovations to Indians, ignoring the fact that the Indian Christian tradition through the Saint Thomas Christians went back to the very beginnings of first century Christian thought.

Interpretations of the causes of India's cultural and spiritual "backwardness" varied, as did the solutions. Many argued that it was Europe's mission to civilize India and hold it as a trust until Indians proved themselves "competent" for self-rule. The immediate consequence of this sense of superiority was to open India to more missionary activity. The contributions of three missionaries based in Serampore (a Danish enclave in Bengal) - William Carey, Joshua Marshman, and William Ward - remained unequaled and have provided inspiration for future generations of their successors.

Policies

The British Parliament enacted a series of laws (see British East India Company), among which the Regulating Act of 1773 stood first, to curb the company traders' unrestrained commercial activities and to bring about some order in territories under company control. Limiting the company charter to periods of twenty years, subject to review upon renewal, the 1773 act gave the British government supervisory rights over the Bengal, Bombay, and Madras presidencies. The Regulating Act also created a unified administration for India, uniting the three presidencies under the authority of the Bengal's governor, who was elevated to the new position of governor-general. Bengal was given preeminence over the others because of its enormous commercial vitality, and Calcutta became the seat of British power in India. Warren Hastings was the first incumbent (1773-1785). The India Act of 1784 sometimes described as the "half-loaf system," as it sought to mediate between Parliament and the company directors, enhanced Parliament's control by establishing the Board of Control, whose members were selected from the cabinet. The Charter Act of 1813 recognized British moral responsibility by introducing just and humane laws in India, foreshadowing future social legislation, and outlawing a number of traditional practices such as sati and thagi (or thuggee, robbery coupled with ritual murder). The Charter Act of 1833 deprived the presidencies of the power to make laws, concentrating legislative power with the Governor-General and his council.

As governor-general from 1786 to 1793, Charles Cornwallis (the Marquis of Cornwallis), professionalized, bureaucratized, and Europeanized the company's administration. He also outlawed private trade by company employees, separated the commercial and administrative functions, and remunerated company servants with generous graduated salaries. Because revenue collection became the company's most essential administrative function, Cornwallis made a compact with Bengali zamindars, who were perceived as the Indian counterparts to the British landed gentry. The Permanent Settlement system, also known as the zamindari system, fixed taxes in perpetuity in return for ownership of large estates; but the state was excluded from agricultural expansion, which came under the purview of the zamindars. In Madras and Bombay, however, the ryotwari (peasant) settlement system was set in motion, in which peasant cultivators had to pay annual taxes directly to the government.

Neither the zamindari nor the ryotwari systems proved effective in the long run because India was integrated into an international economic and pricing system over which it had no control, while increasing numbers of people subsisted on agriculture for lack of other employment. Millions of people involved in the heavily taxed Indian textile industry also lost their markets, as they were unable to compete successfully with cheaper textiles produced in Lancashire's mills from Indian raw materials.

Beginning with the Mayor's Court, established in 1727 for civil litigation in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, justice in the interior came under the company's jurisdiction. In 1772 an elaborate judicial system, known as adalat, established civil and criminal jurisdictions along with a complex set of codes or rules of procedure and evidence. Both Hindu pandits and Muslim qazis (sharia court judges) were recruited to aid the presiding judges in interpreting their customary laws, but in other instances, British common and statutory laws became applicable. In extraordinary situations where none of these systems was applicable, the judges were enjoined to adjudicate on the basis of "justice, equity, and good conscience." The legal profession provided numerous opportunities for educated and talented Indians who were unable to secure positions in the company, and, as a result, Indian lawyers later dominated nationalist politics and reform movements.

Education for the most part was left to the charge of Indians or to private agents who imparted instruction in the vernaculars. But in 1813, the British became convinced of their "duty" to awaken the Indians from intellectual slumber by exposing them to British literary traditions, earmarking a paltry sum for the cause. Controversy between two groups of Europeans - the "Orientalists" and "Anglicists" - over how the money was to be spent prevented them from formulating any consistent policy until 1835 when William Cavendish Bentinck, the governor-general from 1828 to 1835, finally broke the impasse by resolving to introduce the English language as the medium of instruction. English replaced Persian in public administration and education.

The company's education policies in the 1830s tended to reinforce existing lines of socioeconomic division in society rather than bringing general liberation from ignorance and superstition. Whereas the Hindu English-educated minority spearheaded many social and religious reforms either in direct response to government policies or in reaction to them, Muslims as a group initially failed to do so, a position they endeavored to reverse. Western-educated Hindu elites sought to rid Hinduism of its much criticized social evils: the caste system, child marriage, and sati. Religious and social activist Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833), who founded the Brahmo Samaj (Society of Brahma) in 1828, displayed a readiness to synthesize themes taken from Christianity, Deism, and Indian monism, while other individuals in Bombay and Madras initiated literary and debating societies that gave them a forum for open discourse. The exemplary educational attainments and skillful use of the press by these early reformers enhanced the possibility of effecting broad reforms without compromising societal values or religious practices.

The 1850s witnessed the introduction of the three "engines of social improvement" that heightened the British illusion of permanence in India. They were the railroads, the telegraph, and the uniform postal service, inaugurated during the tenure of Dalhousie as governor-general. The first railroad lines were built in 1850 from Howrah (Haora, across the Hughli River from Calcutta) inland to the coalfields at Raniganj, Bihar, a distance of 240 kilometers. In 1851 the first electric telegraph line was laid in Bengal and soon linked Agra, Bombay, Calcutta, Lahore, Varanasi, and other cities. The three different presidency or regional postal systems merged in 1854 to facilitate uniform methods of communication at an all-India level. With uniform postal rates for letters and newspapers - one-half anna and one anna, respectively (sixteen annas equalled one rupee) - communication between the rural and the metropolitan areas became easier and faster. The increased ease of communication and the opening of highways and waterways accelerated the movement of troops, the transportation of raw materials and goods to and from the interior, and the exchange of commercial information.

The railroads did not break down the social or cultural distances between various groups but tended to create new categories in travel. Separate compartments in the trains were reserved exclusively for the ruling class, separating the educated and wealthy from ordinary people. Similarly, when the Sepoy Rebellion was quelled in 1858, a British official exclaimed that "the telegraph saved India." He envisaged, of course, that British interests in India would continue indefinitely.

See also

- British Raj

- Secretary of State for India

- Governor-General of India

- Government of India Act

- History of Bangladesh

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

References

- ^ Ludden 2002, p. 133 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLudden2002 (help)

Contemporary General Histories

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

Monographs and Collections

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

Articles in Journals or Collections

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

Classic Histories

- India Pakistan

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Misplaced Pages:Copyrights for more information.