| Revision as of 02:28, 28 April 2008 editPiotrus (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers286,439 edits rv falsehoods, read the original text or dedicated scholarly works - it has most certainly NOT ceded Vilnius← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:33, 28 April 2008 edit undoPiotrus (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers286,439 edits partial self-rvNext edit → | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

| ] was split between Poland and Lithuania along a border that for the most part remains the border between Poland and Lithuania in modern times; notably the towns of ] (site of the ]), ] and ] remained on the Polish side.<ref name="ŁossowskiKPL166-175"/> | ] was split between Poland and Lithuania along a border that for the most part remains the border between Poland and Lithuania in modern times; notably the towns of ] (site of the ]), ] and ] remained on the Polish side.<ref name="ŁossowskiKPL166-175"/> | ||

| The agreement did not, however, address the most controversial issue — the future status of the city of ] (Wilno), located northeast of the Sudova region and the demarcation line, and recently transferred by retreating Soviets to Lithuanian control.<ref name="ŁossowskiKPL166-175"/> When Suwałki Agreement was signed by the Polish side, Vilnius was garrisoned by Lithuanian troops and behind Lithuanian lines.<ref name=James> James P. Nichol. Diplomacy in the Former Soviet Republics. 1995, p. 123</ref><ref name=Philipp>Philipp Ther, Ana Siljak. Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. 2001, p. 137</ref> | The agreement did not, however, address the most controversial issue — the future status of the city of ] (Wilno), the historic capital of Lithuania, located northeast of the Sudova region and the demarcation line, and recently transferred by retreating Soviets to Lithuanian control.<ref name="ŁossowskiKPL166-175"/> When Suwałki Agreement was signed by the Polish side, Vilnius was garrisoned by Lithuanian troops and behind Lithuanian lines.<ref name=James> James P. Nichol. Diplomacy in the Former Soviet Republics. 1995, p. 123</ref><ref name=Philipp>Philipp Ther, Ana Siljak. Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. 2001, p. 137</ref> | ||

| Yet this was changed almost immediately by the ], which began on October 8 and resulted (in 1922) in the annexation of the city and its surrounding regions by Poland. The Poles denied the knowledge of the mutiny (although in fact Piłsudski and his allies were the ones who orchestrated it<ref name="Slocombe"/>), and noted that the demarcation line and the ceasefire did not extend east of Bastuny (the Polish delegation during the negotiations specifically refused to agree on the demarcation line east of Bastuny - which would cut off Polish access to Vilna - in order to allow Żeligowski's forces space for action). They saw the Suwałki Agreement as a ] of minor importance. The Lithuanians however — particularly after losing Vilnius to Żeligowski's forces and being unable to regain control over it with their own military — expressed outrage at the Żeligowski's actions and went on to use the Suwałki Agreement as the basis for protests in international venues. The Lithuanian side argued (contrary to the provisions of the agreement) that Poland had agreed to a truce along the entire front and to the concession of Vilnius to Lithuania, and that Żeligowski's actions violated the agreement (which they called a ]); this would be denied by the Poles, who would point out that the Suwałki Agreement was explicitly limited in scope so as not to interfere in any way with the future of the Vilnius region.<ref name="ŁossowskiKPL166-175"/> Further, Żeligowski took Vilnius before noon on October 10 when the agreement became law.<ref>{{pl icon}} Algis Kasperavičius, '''', in ''Historycy polscy, litewscy i białoruscy wobec problemów XX wieku Historiografia polska, litewska i białoruska po 1989 roku'', Krzysztof Buchowski i Wojciech Śleszyński (ed.), Instytut Historii Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku, 2003 quoting A. Liekis, Lietuvos sienų raida, t.1, Vilnius 1997, p. 43, 46.</ref> | Yet this was changed almost immediately by the ], which began on October 8 and resulted (in 1922) in the annexation of the city and its surrounding regions by Poland. The Poles denied the knowledge of the mutiny (although in fact Piłsudski and his allies were the ones who orchestrated it<ref name="Slocombe"/>), and noted that the demarcation line and the ceasefire did not extend east of Bastuny (the Polish delegation during the negotiations specifically refused to agree on the demarcation line east of Bastuny - which would cut off Polish access to Vilna - in order to allow Żeligowski's forces space for action). They saw the Suwałki Agreement as a ] of minor importance. The Lithuanians however — particularly after losing Vilnius to Żeligowski's forces and being unable to regain control over it with their own military — expressed outrage at the Żeligowski's actions and went on to use the Suwałki Agreement as the basis for protests in international venues. The Lithuanian side argued (contrary to the provisions of the agreement) that Poland had agreed to a truce along the entire front and to the concession of Vilnius to Lithuania, and that Żeligowski's actions violated the agreement (which they called a ]); this would be denied by the Poles, who would point out that the Suwałki Agreement was explicitly limited in scope so as not to interfere in any way with the future of the Vilnius region.<ref name="ŁossowskiKPL166-175"/> Further, Żeligowski took Vilnius before noon on October 10 when the agreement became law.<ref>{{pl icon}} Algis Kasperavičius, '''', in ''Historycy polscy, litewscy i białoruscy wobec problemów XX wieku Historiografia polska, litewska i białoruska po 1989 roku'', Krzysztof Buchowski i Wojciech Śleszyński (ed.), Instytut Historii Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku, 2003 quoting A. Liekis, Lietuvos sienų raida, t.1, Vilnius 1997, p. 43, 46.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 02:33, 28 April 2008

| This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources. Find sources: "Suwałki Agreement" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2007) |

The Suwałki Agreement, Treaty of Suvalkai, or Suwalki Treaty (Template:Lang-lt, Template:Lang-pl) was an agreement signed in Suwałki on October 7 1920, between Poland and Lithuania, achieved under pressure and mediation from the League of Nations, and resulting in a ceasefire of the Polish-Lithuanian War. It established demarcation lines running through the disputed Sudovian (Polish: Suwalszczyzna, Lithuanian: Suvalkija) region (but not through the also disputed Vilnius Region).

The agreement took place on October 10, but a few days earlier, Polish General Lucjan Żeligowski, acting under secret orders from the Polish Chief of State, Józef Piłsudski, staged a mutiny and took control of the Vilnius region. As a result, that region, along with a corridor connecting it to Poland, was controlled by Poland until 1939.

The nature of the agreement has been the subject of debate; it has been characterized as both an ceasefire of limited scope and as a final treaty that ceded the disputed territory to the participant states.

Negotiations

The Suwałki Conference was a significant event involving Poland and Lithuania, after the respective establishment their independence following the First World War. As a result of ongoing hostilities, the conference was proposed by the Polish Foreign Minister, Eustachy Sapieha, on September 26, 1920, and accepted by the Lithuanian side the following day. The conference began on the evening of September 29. The Polish delegation was led by colonel Mieczysław Mackiewicz, and the Lithuanian by general Maksimas Katche.

The Lithuanian side, having suffered a series of setbacks in the Polish-Lithuanian War, was ready for a compromise over Sudovia (and cession of most of the disputed territory to Poland), but in exchange for Poland's recognizing Lithuanian claims to Vilnius (Polish: Wilno), the historical capital of Grand Duchy of Lithuania which at that time however had a Polish majority. In demographic terms Vilnius was the least Lithuanian of Lithuanian cities, divided near evenly between Poles and Jews, with ethnic Lithuanians constituting a mere fraction of the total population (about 2-3% of the population, according to Russian 1897 and German 1916 censuses - see ethnic history of the Vilnius region for further details). The Lithuanians nonetheless believed that their historical claim to the city (former capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) had precedence and refused to recognize any Polish claims to the city and the surrounding area.

The Polish side was stalling for time. Having the upper hand in the ongoing war, its main problem was the increased pressure from the League of Nations, which wanted both sides to sign a peace treaty. Vilnius was under Lithuanian control (it has been recently transferred by the retreating Soviets, after they were defeated by the Poles in August at the battle of Warsaw, to the Lithuanians as a result of the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920). The Polish leader, Józef Piłsudski, feared that the Entente and the League might accept the fait accompli that had been created by the Soviets' transfer of Vilnius to Lithuania. Pilsudski was preparing a fait accompli of his own — Żeligowski's Mutiny — and preferred that the negotiations be prolonged.

Hence while the Lithuanians wanted to sign a treaty as soon as possible and safeguard their current gains, the Polish side raised issues such as violations of Lithuania's neutrality in the Polish-Soviet War, and protested the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty.

The Lithuanian delegation, after consultations in Kaunas on October 2, proposed their demarcation line on October 3, the Polish delegation, after consultations with Piłsudski, proposed a counterline of their own on October 4 — the day League mediation began.

In the meantime, both sides became involved in the battle of Varėna (Orany) — an important train station which Poles captured, and whose control prevented Lithuanians from being able to move their troops from Sudova region — which they were prepared to surrender — to Vilnius region, which they were not (but which was defended by relatively weak units). Nonetheless in rest of Sudova a semi-official ceasefire — welcomed by the tired troops of both sides — were already in place from October 1.

The agreement

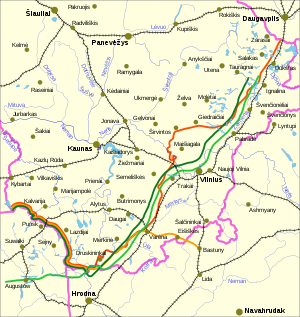

— Line as proposed by Lithuanian delegation during Suwałki conference, October 3, 1920.

— Line as proposed by Lithuanian delegation during Suwałki conference, October 3, 1920.The agreement was finally signed on October 7 1920; it was to have taken full effect at noon on October 10.

The agreement featured the following articles:

- Article I: on the demarcation line; it also stated that the line "in no way prejudices the territorial claims of the two Contracting Parties". Demarcation line would start in the west following the Foch line until it reached the Niemen river. It would follow the Nemen river till Uciecha and Mereczanka (Merkys) River, than follow Merkys river till Varėna (Orany) — which was to be transferred to the Lithuanian side but its train station was on the Polish side. From Orany the line would go near Bortele-Poturce-Montwiliszki-Ejszyszki (Eišiškės)-Podzitwa-Bastuny (Bastunai, Бастынь), with the train station in Bastuny also remaining in Polish hands. The demarcation line east of Bastuny was to be determined by a separate agreement.

- Article II: on the ceasefire; notably the ceasfire was to take place only along the demarcation line, not on the entire Polish-Lithuanian frontline (i.e. not east of Bastuny).

- Article III: on the train station in Varėna (Orany); it was to remain under Polish control but the Polish side promised no restrictions on Lithuanian civilian trains and allowed Lithuanians the transit of 2 military trains per day

- Article IV: on prisoner exchange

- Article V: on the date and time ceasefire starts (October 10 at noon) and map used

Aftermath

Main article: Żeligowski's MutinySudovia was split between Poland and Lithuania along a border that for the most part remains the border between Poland and Lithuania in modern times; notably the towns of Sejny (site of the Sejny Uprising), Suwałki and Augustów remained on the Polish side.

The agreement did not, however, address the most controversial issue — the future status of the city of Vilnius (Wilno), the historic capital of Lithuania, located northeast of the Sudova region and the demarcation line, and recently transferred by retreating Soviets to Lithuanian control. When Suwałki Agreement was signed by the Polish side, Vilnius was garrisoned by Lithuanian troops and behind Lithuanian lines. Yet this was changed almost immediately by the Żeligowski's Mutiny, which began on October 8 and resulted (in 1922) in the annexation of the city and its surrounding regions by Poland. The Poles denied the knowledge of the mutiny (although in fact Piłsudski and his allies were the ones who orchestrated it), and noted that the demarcation line and the ceasefire did not extend east of Bastuny (the Polish delegation during the negotiations specifically refused to agree on the demarcation line east of Bastuny - which would cut off Polish access to Vilna - in order to allow Żeligowski's forces space for action). They saw the Suwałki Agreement as a ceasefire of minor importance. The Lithuanians however — particularly after losing Vilnius to Żeligowski's forces and being unable to regain control over it with their own military — expressed outrage at the Żeligowski's actions and went on to use the Suwałki Agreement as the basis for protests in international venues. The Lithuanian side argued (contrary to the provisions of the agreement) that Poland had agreed to a truce along the entire front and to the concession of Vilnius to Lithuania, and that Żeligowski's actions violated the agreement (which they called a peace treaty); this would be denied by the Poles, who would point out that the Suwałki Agreement was explicitly limited in scope so as not to interfere in any way with the future of the Vilnius region. Further, Żeligowski took Vilnius before noon on October 10 when the agreement became law.

In Piłsudski's view, signing even such a limited agreement was not in Poland's best interests, and he disapproved of it. In a 1923 speech acknowledging that he had directed Żeligowski's coup, Piłsudski stated: "I tore up the Suwałki Treaty, and afterwards I issued a false communique by the General Staff."

The City of Vilnius was returned to Lithuania by the Soviet Union in 1939. It was designated the capital of Lithuania in 1940, and has remained its capital since then (although for about 50 years Lithuania was in fact the Lithuanian SSR in the Soviet Union).

References

- Robert A. Vitas (1984-02-03). "The Polish-Lithuanian Crisis of 1938". Lituanus. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ George Slocombe (1970). A Mirror to Geneva: Its Growth, Grandeur, and Decay.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Piotr Łossowski, Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920 (The Polish-Lithuanian Conflict, 1918–1920), Warsaw, Książka i Wiedza, 1995, ISBN 8305127699, pp. 166–75

- ^ Michael MacQueen, The Context of Mass Destruction: Agents and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 12, Number 1, pp. 27-48, 1998,

- Template:Pl icon Piotr Łossowski, Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920 (The Polish-Lithuanian Conflict, 1918–1920), Warsaw, Książka i Wiedza, 1995, ISBN 8305127699, pp. 11.

- Template:Ru icon Demoscope.

- Template:Pl icon Michał Eustachy Brensztejn (1919). Spisy ludności m. Wilna za okupacji niemieckiej od. 1 listopada 1915 r. Biblioteka Delegacji Rad Polskich Litwy i Białej Rusi, Warsaw.

- James P. Nichol. Diplomacy in the Former Soviet Republics. 1995, p. 123

- Philipp Ther, Ana Siljak. Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. 2001, p. 137

- Template:Pl icon Algis Kasperavičius, Współcześni historycy litewscy o sprawie Wilna i stosunkach polsko-litewskich w latach 1918-1940 oraz zmiany w potocznej świadomości Litwinów, in Historycy polscy, litewscy i białoruscy wobec problemów XX wieku Historiografia polska, litewska i białoruska po 1989 roku, Krzysztof Buchowski i Wojciech Śleszyński (ed.), Instytut Historii Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku, 2003 quoting A. Liekis, Lietuvos sienų raida, t.1, Vilnius 1997, p. 43, 46.

Further reading

- Richard C. Lukas, "The Seizure of Vilna, October 1920", The Historian, vol. 23, issue 2 (February 1961), pp. 234–46.

External links

- Text of Treaty. United Nations Treaty Collection: Lithuanie and Poland. Agreement with regard to the establishment of a provisional "Modus Vivendi", signed at Suwalki, October 7, 1920