| Revision as of 06:48, 23 October 2008 editMac (talk | contribs)23,294 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:23, 24 October 2008 edit undoHughcharlesparker (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers5,767 edits →Further reading: remove a link to a blog - WP:LINKSNext edit → | ||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| * | |||

| * Common, M. and Stagl, S. 2005. ''Ecological Economics: An Introduction''. New York: Cambridge University Press. | * Common, M. and Stagl, S. 2005. ''Ecological Economics: An Introduction''. New York: Cambridge University Press. | ||

| * Daly, H. and Townsend, K. (eds.) 1993. ''Valuing The Earth: Economics, Ecology, Ethics''. Cambridge, Mass.; London, England: MIT Press. | * Daly, H. and Townsend, K. (eds.) 1993. ''Valuing The Earth: Economics, Ecology, Ethics''. Cambridge, Mass.; London, England: MIT Press. | ||

Revision as of 11:23, 24 October 2008

Ecological economics is a transdisciplinary field of academic research within economics that aims to address the interdependence between human economies and natural ecosystems. Its distinguished from environmental economics by its connection to outside disciplines within the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities and its focus on the "scale" conundrum, or how to operate an economy within the ecological constraints of earth's natural resources. According to ecological economist Malte Faber, ecological economics is defined by its focus on nature, justice, and time. Issues of intergenerational equity, irreversibility of environmental change, uncertainty of long-term outcomes, and sustainable development guide ecological economic analysis and valuation.

The identity of ecological economics as a field has been described as fragile, with no generally accepted theoretical framework and a knowledge structure which is not clearly defined. Ecological economists have questioned fundamental mainstream economic approaches such as cost-benefit analysis, and the separability of economic values from scientific research, contending that economics is unavoidably normative rather than positive (empirical). Positional analysis, which attempts to incorporate time and justice issues, is proposed as an alternative.

The related field of biophysical economics, sometimes referred to also as bioeconomics, is based on a conceptual model of the economy connected to, and sustained by, a flow of energy, materials, and ecosystem services. Analysts from a variety of disciplines have conducted research on the economy-environment relationship, with concern for energy and material flows and sustainability, environmental quality, and economic development.

Nature

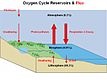

A circular flow of income diagram is typically presented to undergraduate students of economics. In ecological economics, a more complex flow diagram reflects the input of solar energy, which sustains natural inputs and environmental services, which are then used as factors of production. After these natural inputs are consumed, they are outputted as pollution and waste. The potential of an environment to make services and materials is called an environment's source function, and this function is depleted as resources are consumed or pollution contaminates the resources. The sink function describes an environment's ability to absorb and render harmless waste and pollution; when waste output exceeds the limit of the sink function, long-term damage occurs. Some pollutants, such as persistent organic pollutants are persistent, and thus are absorbed very slowly; ecological economists emphasize minimizing "cumulative pollutants". Pollutants affect human health and the health of the climate.

The economic value of natural capital and ecosystem services is accepted by mainstream environmental economics, but is emphasized as especially important in ecological economics. Ecological economists may begin by estimating how to maintain a stable environment before assessing the cost in dollar terms. Ecological economist Robert Costanza led an attempted valuation of the global ecosystem in 1997. Initially published in Nature, the article concluded on $33 trillion with a range from $16 trillion to $54 trillion (in 1997, total global GDP was $27 trillion). Half of the value went to nutrient cycling. The open oceans, continental shelves, and estuaries had the highest total value, and the highest per-hectare values went to estuaries, swamps/floodplains, and seagrass/algae beds. The work was criticized by articles in Ecological Economics Volume 25, Issue 1, but the critics acknowledged the positive potential for economic valuation of the global ecosystem.

The Earth's carrying capacity is another central question. This was first examined by Thomas Malthus, and more recently in an MIT study entitled Limits to Growth. Although the predictions of Malthus have not come to pass, some limit to the Earth's ability to support life are acknowledged. In addition, for real GDP per capita to increase real GDP must increase faster than population growth. Diminishing returns suggest that productivity increases will slow if major technological progress is not made. Food production may become a problem, as erosion, an impending water crisis, and soil salinity (from irrigation) reduce the productivity of agriculture. Ecological economists argue that industrial agriculture, which exacerbates these problems, is not sustainable agriculture, and are generally inclined favorably to organic farming, which also reduces the output of carbon. Global fisheries are believed to have peaked and begun a decline, with valuable habitat such as estuaries in critical condition. Aquaculture, especially fish farming, does not help solve the problem because fish feed is derived from fish, and a recent study stating that fish farming has a major negative effect on wild salmon. Since animals are higher on the trophic level, they are less efficient sources of food energy. Reduced consumption of meat would reduce the demand for food, but as nations develop, they adopt high-meat diets similar to the United States. Genetically modified food (GMF) a conventional solution to the problem, have problems – Bt corn produces its own Bacillus_thuringiensis, but the pest resistant is believed to be only a matter of time. The overall effect of GMF on yields is contentious, with the USDA and FAO acknowledging that GMFs do not necessarily have higher yields and may even have reduced yields.

Global warming is now widely acknowledged as a major issue, with all national scientific academies expressing agreement on the importance of the issue. As the population growth intensifies and energy demand increases, the world faces an energy crisis. Some economists and scientists forecast a global ecological crisis if energy use is not contained – the Stern report is an example. Others, notably William Nordhaus, believe that the world should spend little to reduce carbon emissions because the damage in the future should be discounted. The disagreement has sparked a vigorous debate on issue of discounting and intergenerational equity.

- GLOBAL GEOCHEMICAL CYCLES CRITICAL FOR LIFE

-

Nitrogen cycle

Nitrogen cycle

-

Water cycle

Water cycle

-

Carbon cycle

Carbon cycle

-

Oxygen cycle

Oxygen cycle

Ethics

An important motivation for the emergence of ecological economics has been criticism of the assumptions and approaches of traditional environmental and resource economics, and further a need to distinguish from the social goals of green politics.

By contrast, ecological economics presents a scientific but still more pluralistic approach to study of environmental problems and policy solutions, characterized by systems perspectives and a focus on physical and biological contexts and long-term environmental sustainability. Ecological economics might be regarded as a version of environmental science or human geography with much emphasis on social, political, economic, behavioral and ethical issues. However, it seeks to state its assumptions in a framework similar to that of classical economics with expanded definitions of infrastructure, defense, currency and justice that match the constraints of a society in which carrying capacity is now scarcer.

Template:Renewable energy sources 2

Various competing schools of thought exist in the field. Some are close to resource and environmental economics while others are far more heterodox in outlook. An example of the latter is the European Society for Ecological Economics. An example of the former is the Swedish Beijer International Institute of Ecological Economics.

What differentiates ecological economics schools from classical thought is that capital asset analysis (land, labour, financial capital) has been expanded to make land more active and include the operations of other ecosystems such as rivers, oceans and the atmosphere. In other words, land has been broadened into the concept of natural capital. Furthermore, the analysis of labour is often much more fine-grained and includes examination of the unique ways in which labour adapts to its surroundings. Indigenous languages, for instance, tend to acquire distinctions that match the ecosystems and lifeways in which they operate to enable awareness that colonialism and globalization generally override and ignore. The social capital and possibly unique talents or instructions of a culture will be more closely identified with the location and surrounding ecosystems than in the classical.

Ecological economics inherits some mathematical assumptions from neoclassical economics in that it will employ aggregate measures for genuinely aggregated resources such as the CO2 absorption capacity of the atmosphere (the amount it can absorb before global warming begins to occur). It however generally rejects the neoclassical assumption that local differences in the means of production or extraction method are just another externality, since living ecosystems are impossible to repay or reproduce and often extraordinarily expensive to replace or augment. Unlike the neoclassical assumption of a high-liquidity world in which there are a near infinite number of technology and supply substitutes, ecological economics tends instead to assume that only a narrow range of such substitutes, similar to those used in nature (see biomimicry), will prove feasible as a long-term economic proposition for those living within the biosphere. The major and most obvious difference is that neoclassical economics is wholly unconcerned with the proportion of the supply chain absorbed by transport costs and also unconcerned with the issues in alienation of property rights when consuming goods from far away.

The most cogent example of how the different theories treat similar assets is tropical rainforest ecosystems, most obviously the Yasuni region of Ecuador. While this area has substantial deposits of bitumen it is also one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth and some estimates establish it has over 200 undiscovered medical substances in its genomes - most of which would be destroyed by logging the forest or mining the bitumen. Effectively, the instructional capital of the genomes is undervalued by both classical and neoclassical means which would view the rainforest primarily as a source of wood, oil/tar and perhaps food. Increasingly the carbon credit for leaving the extremely carbon-intensive ("dirty") bitumen in the ground is also valued - the government of Ecuador set a price of US$350M for an oil lease with the intent of selling it to someone committed to never exercising it at all and instead preserving the rainforest. Bill Clinton, Paul Martin and other former world leaders have become closely involved in this project which includes lobbying for the issue of International Monetary Fund Special Drawing Rights to recognize the rainforest's value directly within the framework of the Bretton Woods institutions. If successful this would be a major victory for advocates of ecological economics as the new mainstream form of economics.

History and Development

The first book with the title Ecological Economics was published in Europe by Juan Martinez-Alier (Blackwell, Oxford, 1987) tracing the history of ecological critiques of economics since the 1880s to the 1950s. European conceptual founders include Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1971), William Kapp (1944) and Karl Polanyi (1950). Furthermore, some key concepts of what is now ecological economics are evident in the writings of E.F. Schumacher, whose book Small Is Beautiful – A Study of Economics as if People Mattered (1973) was published just a few years before the first edition of Herman Daly's comprehensive and persuasive Steady-State Economics (1977).

The antecedents can be traced back to the Romantics of the 1800s as well as some Enlightenment political economists of that era. Concerns over population were expressed by Thomas Malthus, while John Stuart Mill hypothesized that the "stationary state" of an economy might be something that could be considered desirable, anticipating later insights of modern ecological economists, without having had their experience of the social and ecological costs of the dramatic post-World War II industrial expansion. As Martinez-Alier explores in his book the debate on energy in economic systems can also be traced into the 1800s e.g. Nobel prize-winning chemist, Frederick Soddy (1877-1956).

In North America, conceptual founders include economists Kenneth Boulding and Herman Daly, ecologists C.S. Holling, H.T. Odum and Robert Costanza, biologist Gretchen Daily and physicist Robert Ayres. Daly and Costanza were part of the institutional founding of the field - resulting in the establishment of the academic journal Ecological Economics and the International Society for Ecological Economics (ISEE). Some attribute origination of ecological economics as a specific field per se to professor Herman Daly, University of Maryland, a former economist at the World Bank. Ecological economics has been popularized by ecologist and University of Vermont Professor Robert Costanza. CUNY geography professor David Harvey explicitly added ecological concerns to political economic literature. This parallel development in political economy has been continued by analysts such as sociologist John Bellamy Foster.

The Romanian economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1906-1994), who was among Daly's teachers at Vanderbilt University, provided ecological economics with a modern conceptual framework based on the material and energy flows of economic production and consumption. His magnum opus, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (1971), has been highly influential.

Green Economics is a more recent development that goes beyond the traditional scope of Ecological Economics but shares some of its basic principles. Green Economics comprises all aspects and sub-disciplines of economics, not only ecology related, and analyses economic issues with a pluralistic, holistic and long term view. The aim of this emerging discipline is the reform of mainstream economics towards an unbiased understanding of economic facts and the political choices available to enhance the economic freedom available to all stakeholders. Comprehensive academic work in this field is organised and co-ordinated by the Green Economics Institute, an academic think tank founded in 2004 in the UK, which edits the International Journal of Green Economics. See links below to the Institute and the journal publisher. The term Green Economics is in addition employed by some, mainly UK based, individuals acting as a political lobby and activist forum rather than taking the purely scientific approach dominant amongst other green or progressive economists. Their views can differ from the academically developed discipline as the proposals and concepts are party political in nature or based on individually favoured ideas by some of the proponents.

Articles by Inge Ropke (2004, 2005) and Clive Spash (1999) cover the development and modern history of ecological economics and explain its differentiation from resource and environmental economics, as well as some of the controversy between American and European schools of thought.

Topics in ecological economics

Concept

| Thermodynamics | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The classical Carnot heat engine The classical Carnot heat engine | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Branches | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Laws | |||||||||||||||||||||

Systems

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

System propertiesNote: Conjugate variables in italics

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Material properties

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Equations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potentials | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientists | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||

The primary objective of ecological economics (EE) is to ground economic thinking and practice in physical reality, especially in the laws of physics (particularly the laws of thermodynamics) and in knowledge of biological systems. It accepts as a goal the improvement of human well-being through development, and seeks to ensure achievement of this through planning for the sustainable development of ecosystems and societies. Of course the terms development and sustainable development are far from lacking controversy. Richard Norgaard argues traditional economics has hi-jacked the development terminology in his book Development Betrayed. Well-being in ecological economics is also differentiated from welfare as found in mainstream economics and the 'new welfare economics' from the 1930s which informs resource and environmental economics. This entails a limited preference utilitarian conception of value i.e., Nature is valuable to our economies, that is because people will pay for its services such as clean air, clean water, encounters with wilderness, etc.

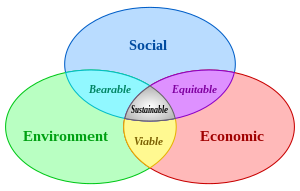

Ecological economics distinguishes itself from neoclassical economics primarily by its assertion that the economy is an embedded within an environmental system. Ecology deals with the energy and matter transactions of life and the Earth, and the human economy is by definition contained within this system. Ecological economists feel neoclassical economics has ignored the environment, at best relegating it to be a subset of the human economy. Economic theory, as encapsulated in general equilibrium models, then assume both an infinite resource base and also infinite waste sinks with no feedbacks; in simpler terms, resources never run out and pollution never occurs. This allows neoclassical economics to claim theoretically that infinite economic growth is both possible and desirable.

However, this belief disagrees with much of what the natural sciences have learned about the world, and, according to Ecological Economics, completely ignores the contributions of Nature to the creation of wealth e.g., the planetary endowment of scarce matter and energy, along with the complex and biologically diverse ecosystems that provide goods and ecosystem services directly to human communities: micro- and macro-climate regulation, water recycling, water purification, storm water regulation, waste absorption, food and medicine production, pollination, protection from solar and cosmic radiation, the view of a starry night sky, etc.

There has then been a move to regard such things as natural capital and ecosystems functions as goods and services. However, this is far from uncontroversial within ecology or ecological economics due to the potential for narrowing down values to those found in mainstream economics and the danger of merely regarding Nature as a commodity. This has been referred to as ecologists 'selling out on Nature'. There is then a concern that ecological economics has failed to learn from the extensive literature in environmental ethics about how to structure a plural value system.

Allocation of resources

Resource and neoclassical economics focus primarily on the efficient allocation of resources, and less on two other fundamental economic problems which are central to ecological economics: distribution (equity) and the scale of the economy relative to the ecosystems upon which it is reliant. Ecological Economics also makes a clear distinction between growth (quantitative) and development (qualitative improvement of the quality of life) while arguing that neoclassical economics confuses the two. Ecological economics challenges the common normative approach taken towards natural resources, claiming that it misvalues nature by displaying it as interchangeable with human capital--labor and technology. EE counters this convention by asserting that human capital is instead complementary to and dependent upon natural systems, as human capital inevitably derives from natural systems. From these premises, it follows that economic policy has a fiduciary responsibility to the greater ecological world, and that, by misvaluing the importance of nature, sustainable progress (as opposed to economic growth) --which is the only solution to elevating the standard of living for citizens worldwide--will not result. Furthermore, ecological economists point out that, beyond modest levels, increased per-capita consumption (the typical economic measure of "standard of living") does not necessarily lead to improvements in human well-being, while this same consumption can have harmful effects on the environment and broader societal well-being.

Energy economics

It rejects the view of energy economics that growth in the energy supply is related directly to well being, focusing instead on biodiversity and creativity - or natural capital and individual capital, in the terminology sometimes adopted to describe these economically. In practice, ecological economics focuses primarily on the key issues of uneconomic growth and quality of life. Ecological economists are inclined to acknowledge that much of what is important in human well-being is not analyzable from a strictly economic standpoint and suggests an interdisciplinary approach combining social and natural sciences as a means to address this.

Thermoeconomics is based on the proposition that the role of energy in biological evolution should be defined and understood through the second law of thermodynamics but in terms of such economic criteria as productivity, efficiency, and especially the costs and benefits (or profitability) of the various mechanisms for capturing and utilizing available energy to build biomass and do work. As a result, thermoeconomics are often discussed in the field of ecological economics, which itself is related to the fields of sustainability and sustainable development.

Energy accounting and balance

An energy balance can be used to track energy through a system, and is a very useful tool for determining resource use and environmental impacts, using the First and Second laws of thermodynamics, to determine how much energy is needed at each point in a system, and in what form that energy is a cost in various environmental issues. The energy accounting system keeps track of energy in, energy out, and non-useful energy versus work done, and transformations within the system.

Energy Accounting is the hypothetical system of distribution, proposed by Technocracy Incorporated in the Technocracy Study Course, which would record the energy used to produce and distribute goods and services consumed by citizens in a Technate.

Scientists have written and speculated on different aspects of energy accounting. Many variations of energy accounting are in use now, as this issue relates to current (price system) economics directly, as well as projected models in possible Non-market economics systems.

In Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt, (George Allen & Unwin 1926), Frederick Soddy turned his attention to the role of energy in economic systems. He criticized the focus on monetary flows in economics, arguing that “real” wealth was derived from the use of energy to transform materials into physical goods and services. Soddy’s economic writings were largely ignored in his time, but would later be applied to the development of bioeconomics and ecological economics in the late 20th century.

Environmental services

A study was carried out by Costanza and colleagues to determine the 'price' of the services provided by the environment. This was determined by averaging values obtained from a range of studies conducted in very specific context and then transferring these without regard to that context. Dollar figures were averaged to a per hectare number for different types of ecosystem e.g. wetlands, oceans. A total was then produced which came out at 33 trillion US dollars (1997 values), more than twice the total GDP of the world at the time of the study. This study was criticized by pre-ecological and even some environmental economists - for being inconsistent with assumptions of financial capital valuation - and ecological economists - for being inconsistent with an ecological economics focus on biological and physical indicators.. See also ecosystem valuation and price of life.

The whole idea of treating ecosystems as goods and services to be valued in monetary terms remains controversial to some. A common objection is that life is precious or priceless, but this demonstrably degrades to it being worthless under the assumptions of any branch of economics. Reducing human bodies to financial values is a necessary part of every branch of economics and not always in the direct terms of insurance or wages. Economics, in principle, assumes that conflict is reduced by agreeing on voluntary contractual relations and prices instead of simply fighting or coercing or tricking others into providing goods or services. In doing so, a provider agrees to surrender time and take bodily risks and other (reputation, financial) risks. Ecosystems are no different than other bodies economically except insofar as they are far less replaceable than typical labour or commodities.

Despite these issues, many ecologists and conservation biologists are pursuing ecosystem valuation. Biodiversity measures in particular appear to be the most promising way to reconcile financial and ecological values, and there are many active efforts in this regard. The growing field of biodiversity finance began to emerge in 2008 in response to many specific proposals such as the Ecuadoran Yasuni proposal or similar ones in the Congo. US news outlets treated the stories as a "threat" to "drill a park" reflecting a previously dominant view that NGOs and governments had the primary responsibility to protect ecosystems. However Peter Barnes and other commentators have recently argued that a guardianship/trustee/commons model is far more effective and takes the decisions out of the political realm.

Commodification of other ecological relations as in carbon credit and direct payments to farmers to preserve ecosystem services are likewise examples that permit private parties to play more direct roles protecting biodiversity. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization achieved near-universal agreement in 2008 that such payments directly valuing ecosystem preservation and encouraging permaculture were the only practical way out of a food crisis. The holdouts were all English-speaking countries that export GMOs and promote "free trade" agreements that facilitate their own control of the world transport network: The US, UK, Canada and Australia . Increasingly the pro-GMO pro-trade view is in the extreme minority worldwide though it is disproportionately represented at the IMF, World Bank and so on.

Externalities

Ecological economics is founded upon the view that the NCE assumption that environmental and community costs and benefits are mutually canceling "externalities" is not warranted. Juan Martinez Alier , for instance shows that the bulk of consumers are automatically excluded from having an impact upon the prices of commodities, as these consumers are future generations who have not been born yet. The assumptions behind future discounting, which assume that future goods will be cheaper than present goods, has been criticised by Fred Pearce and by the recent Stern Report. Although the Stern report itself does employ discounting and has been criticised by ecological economists. Concerning these externalities, Paul Hawken argues that the only reason why goods produced unsustainably are usually cheaper than goods produced sustainably is due to a hidden subsidy, paid by the non monetarised human environment, community or future generations. These arguments are developed further by Hawken, Amory and Hunter Lovins in "Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution".

See also

2References

- ^ Malte Faber. (2008). How to be an ecological economist. Ecological Economics 66(1):1-7. Preprint.

- Peter Victor. (2008). Book Review: Frontiers in Ecological Economic Theory and Application. Ecological Economics 66(2-3).

- Mattson L. (1975). Book Review: Positional Analysis for Decision-Making and Planning by Peter Soderbaum. The Swedish Journal of Economics.

- Cutler J. Cleveland, "Biophysical economics", Encyclopedia of Earth, Last updated: September 14, 2006.

- ^ Harris J. (2006). Environmental and Natural Resource Economics: A Contemporary Approach. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Costanza R; et al. (1998). "The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital1". Ecological Economics. 25 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(98)00020-2.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Washington Post. Salmon Farming May Doom Wild Populations, Study Says.

- Soil Association. UK Organic Group Exposes Myth that Genetically Engineered Crops Have Higher Yields. Organic Consumers Association.

- Kapp, K. W. (1950) The Social Costs of Private Enterprise. New York: Shocken.

- Polanyi, K. (1944) The Great Transformation. New York/Toronto: Rinehart & Company Inc.

- Schumacher, E.F. 1973. Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered. London: Blond and Briggs.

- Daly, H. 1991. Steady-State Economics (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. 1971. The Entropy Law and the Economic Process. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Røpke, I. (2004) The early history of modern ecological economics. Ecological Economics 50(3-4): 293-314. Røpke, I. (2005) Trends in the development of ecological economics from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Ecological Economics 55(2): 262-290.

- Spash, C. L. (1999) The development of environmental thinking in economics. Environmental Values 8(4): 413-435.

- Norgaard, R. B. (1994) Development Betrayed: The End of Progress and a Coevolutionary Revisioning of the Future. London: Routledge

- Daily, G.C. 1997. Nature's Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Biodiversity Synthesis. Washington, D.C.: World Resources Institute.

- McCauley, D. J. (2006) Selling out on nature. Nature 443(7): 27-28

- Daly, H. and Farley, J. 2004. Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications. Washington: Island Press.

- Peter A. Corning 1 *, Stephen J. Kline. (2000). Thermodynamics, information and life revisited, Part II: Thermoeconomics and Control information Systems Research and Behavioral Science, Apr. 07, Volume 15, Issue 6 , Pages 453 – 482

- Corning, P. (2002). “Thermoeconomics – Beyond the Second Law” – source: www.complexsystems.org

- Cutler J. Cleveland, "Biophysical economics", Encyclopedia of Earth, Last updated: September 14, 2006.

- http://telstar.ote.cmu.edu/environ/m3/s3/05account.shtml Environmental Decision making, Science and Technology

- http://ecen.com/eee9/ecoterme.htm Economy and Thermodynamics

- Stabile, Donald R. "Veblen and the Political Economy of the Engineer: the radical thinker and engineering leaders came to technocratic ideas at the same time," American Journal of Economics and Sociology (45:1) 1986, 43-44.

- http://www.eoearth.org/article/Soddy,_Frederick Soddy, Frederick - Encyclopedia of Earth

- Costanza, R., d'Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Naeem, S., Limburg, K., Paruelo, J., O'Neill, R.V., Raskin, R., Sutton, P., and van den Belt, M. 1997. The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387: 253-260.

- Norgaard, R.B. and Bode, C. 1998. Next, the value of God, and other reactions. Ecological Economics 25: 37-39.

- Jose Maria Figueres Olson (Foreword), Robert Costanza (Editor), Olman Segura (Editor), Juan Martinez-Alier (Editor), Juan Martinez Alier (Author) (1996) "Getting Down to Earth: Practical Applications Of Ecological Economics" (Intl Society for Ecological Economics) (Island Press)

- Pearce, Fred "Blueprint for a Greener Economy"

- Spash, C. L. (2007) The economics of climate change impacts à la Stern: Novel and nuanced or rhetorically restricted? Ecological Economics 63(4): 706-713

- Hawken, Paul (1994) "The Ecology of Commerce" (Collins)

- Hawken, Paul; Amory and Hunter Lovins (2000) "Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution" (Back Bay Books)

Further reading

- Common, M. and Stagl, S. 2005. Ecological Economics: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Daly, H. and Townsend, K. (eds.) 1993. Valuing The Earth: Economics, Ecology, Ethics. Cambridge, Mass.; London, England: MIT Press.

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. 1975. Energy and economic myths. Southern Economic Journal 41: 347-381.

- Martinez-Alier, J. (1990) Ecological Economics: Energy, Environment and Society. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell.

- Røpke, I. (2004) The early history of modern ecological economics. Ecological Economics 50(3-4): 293-314.

- Røpke, I. (2005) Trends in the development of ecological economics from the late 1980s to the early 2000s. Ecological Economics 55(2): 262-290.

- Spash, C. L. (1999) The development of environmental thinking in economics. Environmental Values 8(4): 413-435.

- Vatn, A. (2005) Institutions and the Environment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar

- Krishnan R, Harris JM, Goodwin NR. (1995). A Survey of Ecological Economics. Island Press. ISBN 1559634111, 9781559634113.

External links

- The International Society for Ecological Economics (ISEE) - http://www.ecoeco.org/

- The International Journal of Green Economics, http://www.inderscience.com/ijge

- The Green Economics Institute http://www.greeneconomics.org.uk

- Eco-Economy Indicators: http://www.earth-policy.org/Indicators/index.htm

- The Inspired Economist.

- Ecological Economics Encyclopedia - http://www.ecoeco.org/education_encyclopedia.php

- The academic journal, Ecological Economics - http://www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

- The US Society of Ecological Economics - http://www.ussee.org/

- The Beijer International Institute for Ecological Economics - http://www.beijer.kva.se/

- Gaian Economics website - http://www.gaianeconomics.org/

- Sustainable Prosperity - http://sustainableprosperity.ca/

- The Gund Institute of Ecological Economics - http://www.uvm.edu/giee

- Ecological Economics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute - http://www.economics.rpi.edu/ecological.html

- An ecological economics article about reconciling economics and its supporting ecosystem - http://www.fs.fed.us/eco/s21pre.htm

- "Economics in a Full World", by Herman E. Daly - http://sef.umd.edu/files/ScientificAmerican_Daly_05.pdf

- Steve Charnovitz, "Living in an Ecolonomy: Environmental Cooperation and the GATT," Kennedy School of Government, April 1994.