| Revision as of 20:14, 17 April 2009 editDocu (talk | contribs)97,802 editsm →As an inventor (1892–1897): clean up, WP:CHECKWIKI #47 using AWB← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:45, 21 April 2009 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,458,685 editsm Citation maintenance. Added: format. You can use this bot yourself! Please report any bugs.Next edit → | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

| |month=May | |month=May | ||

| |year=1927 | |year=1927 | ||

| |accessdate=2007-02-24 | |||

| | |

|format={{dead link|date=April 2009}} – <sup></sup>}}; republished in ''Hotwire: The Newsletter of the Toaster Museum Foundation'', vol. 3, no. 3, online edition. The piece is largely an interview of Hoskins. <small>(And there actually is a Toaster Museum, backed by a related foundation. They take the history of toast, and electrical heating in general, quite seriously.)</small></ref> he became the co-inventor (with ]) in 1897 of modern ].<ref name="Clark" /><ref name="Patent578514">{{US patent|0578514}}, March 9, 1897</ref> He was originally (and again in retirement from the billiards circuit) a ]n, but spent much of his professional career in ].<ref name="APObit" /><ref name="Clark" /> At his peak, the '']'' labeled Spinks " of the most brilliant players among the veterans of the game",<ref name="NYTDemarest2" /> and he still holds the world record for points scored in a row (1,010) using a particular shot type.<ref name="Shamos 1999" /> Aside from his billiards playing career, he founded a ] manufacturing business, and was both a ] investor and director, and a flower and ] farmer and ], originator of the eponymous Spinks avocado ]. | ||

| ==As an inventor (1892–1897)== | ==As an inventor (1892–1897)== | ||

| Line 33: | Line 34: | ||

| While Spinks was a world-class player, his lasting contribution to ]s was the innovations he brought to the game and the industry resulting from his fascination with the ]s used by players on the leather {{Cuegloss|Cue tip|tips}} of their ]s. | While Spinks was a world-class player, his lasting contribution to ]s was the innovations he brought to the game and the industry resulting from his fascination with the ]s used by players on the leather {{Cuegloss|Cue tip|tips}} of their ]s. | ||

| {{Cuegloss|Chalk|Cue "chalk"}} (used since at least 1807) helps the tip better grip the {{Cuegloss|Cue ball|cue ball}} (very briefly) on a {{Cuegloss|Stroke|stroke}} and prevent {{Cuegloss|Miscue|miscueing}}, as well as permitting the player to impart a great deal more {{Cuegloss|Spin|spin}} to the ball, vital for {{Cuegloss|Position play|position play}} and for spin-intensive shots such as {{Cuegloss|Massé|massés}}. In the 1800s, actual ] (generally ] lumps, suspended from strings), and even ] was often used, but players experimented with other powdery, abrasive substances,<ref name="Shamos 1999" />{{Rp|46}}<ref name="APObit" /> since true chalk had a deleterious effect on the game equipment, not only discoloring the billiard cloth but actually causing the fabric to rot.<ref>{{cite book | author = Victor Stein & Paul Rubino | year = 1996 | edition= 2nd |chapter= Tables, Cloths, and Balls | title = The Billiard Encyclopedia: An Illustrated History of the Sport | publisher = Blue Book Publcations, Inc. | location = ] | pages = p. 240 | |

{{Cuegloss|Chalk|Cue "chalk"}} (used since at least 1807) helps the tip better grip the {{Cuegloss|Cue ball|cue ball}} (very briefly) on a {{Cuegloss|Stroke|stroke}} and prevent {{Cuegloss|Miscue|miscueing}}, as well as permitting the player to impart a great deal more {{Cuegloss|Spin|spin}} to the ball, vital for {{Cuegloss|Position play|position play}} and for spin-intensive shots such as {{Cuegloss|Massé|massés}}. In the 1800s, actual ] (generally ] lumps, suspended from strings), and even ] was often used, but players experimented with other powdery, abrasive substances,<ref name="Shamos 1999" />{{Rp|46}}<ref name="APObit" /> since true chalk had a deleterious effect on the game equipment, not only discoloring the billiard cloth but actually causing the fabric to rot.<ref>{{cite book | author = Victor Stein & Paul Rubino | year = 1996 | edition= 2nd |chapter= Tables, Cloths, and Balls | title = The Billiard Encyclopedia: An Illustrated History of the Sport | publisher = Blue Book Publcations, Inc. | location = ] | pages = p. 240 |isbn= 1-886768-06-4}}</ref> | ||

| In 1892, Spinks was particularly impressed by a piece of natural chalk-like substance obtained in ], and presented it to chemist and electrical engineer William Hoskins (1862–1934)<ref name="CHiC1">{{Cite web | In 1892, Spinks was particularly impressed by a piece of natural chalk-like substance obtained in ], and presented it to chemist and electrical engineer William Hoskins (1862–1934)<ref name="CHiC1">{{Cite web | ||

| Line 138: | Line 139: | ||

| |title=City of San Diego and San Diego County: The Birthplace of California | |title=City of San Diego and San Diego County: The Birthplace of California | ||

| |volume=Vol. 1 | |volume=Vol. 1 | ||

| ⚫ | |section="Ora C. Morningstar" entry | ||

| |section=Section 31: "Morningstar, Maurice Daly, billiards" | |||

| |last=McGrew | |last=McGrew | ||

| |first=Clarence Alan | |first=Clarence Alan | ||

| Line 145: | Line 146: | ||

| |publisher=] | |publisher=] | ||

| |location=] & New York, NY | |location=] & New York, NY | ||

| ⚫ | |section="Ora C. Morningstar" entry | ||

| }}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 15:45, 21 April 2009

| William A. Spinks | |

|---|---|

Spinks in 1924 Spinks in 1924(US Passport photo from Dept. of State microfilm) | |

| Born | July 11, 1865, San Jose, California |

| Died | January 15, 1933(1933-01-15) (aged 67), Monrovia, California |

| Nationality | |

| Other names | W. A. Spinks, Billy Spinks |

| Occupation(s) | Billiards player, inventor, sporting goods manufacturer, oil company investor/director, farmer/horticuluralist |

| Years active | ca. 1893 – 1920s |

| Known for | Co-invention of billiard chalk, balkline billiards world record, the Spinks avocado cultivar |

| Signature | |

William Alexander Spinks Jr. (1865–1933), known professionally as William A. Spinks or (in the initialing practice common in his era) W. A. Spinks, and rarely also referred to as Billy Spinks), was an American professional carom billiards player in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In addition to being amateur Pacific Coast billiards champion several times, a world champion contender in more than one cue sports discipline, and an exhibition player in Europe, he became the co-inventor (with William Hoskins) in 1897 of modern billiard chalk. He was originally (and again in retirement from the billiards circuit) a Californian, but spent much of his professional career in Chicago, Illinois. At his peak, the New York Times labeled Spinks " of the most brilliant players among the veterans of the game", and he still holds the world record for points scored in a row (1,010) using a particular shot type. Aside from his billiards playing career, he founded a sporting goods manufacturing business, and was both a petroleum company investor and director, and a flower and avocado farmer and horticulturist, originator of the eponymous Spinks avocado cultivar.

As an inventor (1892–1897)

While Spinks was a world-class player, his lasting contribution to cue sports was the innovations he brought to the game and the industry resulting from his fascination with the abrasives used by players on the leather tips of their cue sticks.

Cue "chalk" (used since at least 1807) helps the tip better grip the cue ball (very briefly) on a stroke and prevent miscueing, as well as permitting the player to impart a great deal more spin to the ball, vital for position play and for spin-intensive shots such as massés. In the 1800s, actual chalk (generally calcium carbonate lumps, suspended from strings), and even plaster was often used, but players experimented with other powdery, abrasive substances, since true chalk had a deleterious effect on the game equipment, not only discoloring the billiard cloth but actually causing the fabric to rot.

In 1892, Spinks was particularly impressed by a piece of natural chalk-like substance obtained in France, and presented it to chemist and electrical engineer William Hoskins (1862–1934) of Chicago for analysis, who determined that it was porous volcanic rock (pumice) originally probably from Mount Etna, Sicily. Using the rock as a starting place, the two experimented together with different formulations of various materials to achieve the cue ball "action" that Spinks sought.

They finally honed in on a mixture of Illinois-sourced silica and the abrasive substance corundum or aloxite (a form of aluminum oxide, Al2O3), founding William A. Spinks & Company with a factory in Chicago after securing a patent on March 9, 1897. Spinks himself later left the company as an active party, which retained his name and was subsequently run by Hoskins, and later by Hoskins's cousin Edmund F. Hoskin, after Hoskins moved on to other projects.

While regular calcium carbonate chalk had been packaged and marketed on a local scale by various parties (English player Jack Carr's "Twisting Powder" of the 1820s being the earliest recorded example, although considered dubious by some billiards researchers), the Spinks Company product (which is still emulated by modern manufacturers today with differing, proprietary compounds) effectively revolutionized billiards. The modern product provided a cue tip friction enhancer that allowed the tip to better grip the cue ball briefly and impart a previously unattainable amount of spin on the ball, which consequently allowed more precise and extreme cue ball control, made miscueing less likely, made curve and massé shots more plausible, and ultimately spawned the new cue sport of artistic billiards. Even the basic draw and follow shots of pool games (like eight-ball and nine-ball) depend heavily on the effects and properties of modern billiard "chalk".

Spinks made a "fortune" from his co-invention and the company that sold it to the world.

As a player

Spinks was a formidable specialist and professional competitor in straight rail billiards (early on), and balkline billiards (arguably the most difficult of all cue sports aside from artistic billiards), especially 14.2 and later 18.2 balkline, and skilled enough at the even more difficult 18.1 variant to hold his own against World Champions.

1890s: Rise as a professional contender

He began his competitive professional playing career in Brooklyn, New York, ca. 1893.

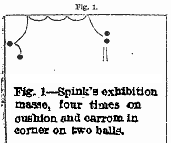

On December 19, 1893 in Brooklyn, Spinks played in an exhibition that also featured the great Maurice Daly and young champion Frank Ives, and gave demonstrations of fancy massé shots. He also played a 14.2 balkline match against World Champion Jacob Schaefer Sr.; Schaefer won, 250–162, with a high run and average of 88 and 20 (respectively) to Spinks's 33 and 13.

In 1894, he was living in Cincinnati, Ohio, and in January of that year offered a convoluted challenge to veteran cueist Edward McLaughlin of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to play him either a single 14.2 match to 600 points for US$500 each (a substantial amount of money in that period for someone to put up personally on a bet – approximately $11,400 in 2007 dollars) in New York, or one in New York and one in Philadelphia, or one in Cincinnati and one in Philadelphia, whatever McLaughlin preferred, and even offered to pay travel expenses to Cincinnati.

Spinks issued an even more curious challenge in November 1894, to play 14.2 balkline against (almost) any challenger to 600 points for a $1,000 pot again, and while including French champion Edward Fournil, the bet specifically excluded the top-three names in that era of the sport, namely Shaefer, Ives and George Franklin Slosson. The challenge was accepted by well-known Chicago pro Thomas Gallagher (in a match that future champion Ora Morningstar traveled all the way to Chicago to see).

Spinks was apparently not a fan of upstart cueist Ives in particular. Days after issuing his caveat-laden challenge, Spinks was described by an onlooking journalist as "very uneasy until the seventeenth inning" as a spectator at the 14.2 balkline World Champion challenge match between Ives and incumbent Schaefer; the latter's point total had been trailing, sometimes badly, in all sixteen previous innings until he rallied in the final one of the game. Spinks, along with Gallagher, even helped Schaefer train in 14.2 for another match against Ives, in October of that year; though Spinks lost this practice match 600–369 (averages 23 vs. 14), he had a high run of 109, to Schaefer's 102 (and Gallagher's 157 total).

Spinks was reported in the press in 1895 to be specifically desired as a competitor in an upcoming seven-man invitational tournament for "second class" professional players (i.e., not the top 3), organized by Daly, and with as much as $1,200 (approx. $28,400 in 2007 dollars) added.

Spinks had moved to Chicago by 1896, and was perfecting his billiard chalk with Hoskins. That year he was noted for besting McLaughlin at 14.2 by a comfortable 2500–2300 margin (with averages of 11 vs. 10) in a five-evening, $250 (approx. $6150, in 2007 dollars) 14.2 match, December 8–12, in Slosson's New York City billiard hall. At one point he had trailed rather badly, 1500–1880, after McLaughlin pulled off a stunning run of 140 (Spinks's highest recorded run of the match was 69).

By 1897, the year of the launch of Spinks & Company, he had evidently overcome his seeming reluctance to face World Champions again (perhaps from having several years' experience with his own product prototypes). Spinks competed in (but did not win) a December 3 open tournament.

The next month in New York City, a January 15–21, 1898 double-elimination, five-man invitational 18.2 balkline tournament was arranged, again in Chicago. It was a handicapped event, featuring the five top players from the previous event – Schaefer and Ives, as World Champions, had to reach 600 points to Spinks's, William Catton's and George Sutton's 260. Without having to rely on the 600-point handicap, Spinks beat Schaefer flat-out, 260–139 (with a high run of 48 vs. Schaefer's 38) in his January 18 second game. Spinks (with a high run of "only" 44) was himself defeated in a very close 249–260 third game a day later by Catton (high run 56) – by way of comparison, the same night Ives trounced Sutton by a whopping 400–160. By January 20, Spinks seemed to be running out of steam, as Sutton took him 260–118, (high runs 73 vs. 30), and he lost again 154–400 (with another high run of 44) to Ives a day later. (In Spinks's defense, he not only did better against Ives than Catton had, but Ives also had a very impressive high run of 136, making it virtually impossible to catch up.) This loss put Spinks out of the tournament at 4th place.

1900s: World-class competitor

Spinks was still considered a newsworthy contender over a decade later, for the World 18.2 Balkline Championship of 1909, being enumerated in "a fine list of entries" anticipated for the March event.

On January 11, Spinks (with a high run of 51) beat former amateur champion and then-pro Calvin Demarest, 250–199, in only 15 innings, despite scoring 0 points in 4 innings and only 1 point in another, by building several solid runs in the innings in which things went his way. For all intents and purposes it was a 10-inning win. Demarest took his revenge only days later, defeating Spinks in a close 250–225, 23-inning game on January 13, despite Spinks's high run of 78 (his highest 18.2 run on record in publicly-available sources, and considerably higher than Demarest's 52 that night). Spinks lost to him again the very next day, 175–250, in an exhibition game, despite Spinks's solid high run of 69, and also beat veteran pro Tom Gallagher.

In January 1909, just prior to an 18.1 balkline championship at Madison Square Garden (in which Spinks was not competing), he and Mauricy Daly were observed playing practice games with Sutton for the latter's pre-event training, in Daly's billiard hall in New York City, on multiple occasions over a several-day stretch. While Spinks lost all but one of the recorded matches of this series, one loss was by a hair, at 400–399, another was 400–370, and his victory was a surprising 300–194 – and 18.1 was not his preferred game.

Many articles of the era stress that Spinks was a Californian, because during this period American billiards was completely dominated by East-Coasters and a few Midwesterners.

1910s: Setting a record and leveling the field

Spinks was noted in 1912 for a still-unbroken world record run of 1,010 continuous points at 18.2 balkline using the "chuck nurse" (a form of nurse shot), and could have made more, but stopped, before anchor space rules were instituted especially to curtail the effectiveness of the chuck nurse. The use of such repetitive, predictable shots by Spinks, Schaefer Sr. and their contemporaries led to the development of the more advanced and restrictive 14.1 balkline rules (invented in 1907, but not played professionally until 1914), which further thwarted the ease of reliance on nurse shots than the older balkline games already did.

In August 1915, Spinks was tapped to join a consultative panel of notable players and major billiard hall proprietors to help develop a new handicapping system for balkline billiards, organized by the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company, at that time the organizers of the World Championships. The inspiration for the new system was simply making it possible for the newly ascendant Willie Hoppe to be meaningfully challenged (his near-unassailability was hurting billiard tournament revenues, because the outcome was considered foreordained by many potential ticket-buyers), although the system was expected to level the playing field in other ways, especially making it easier for skilled amateurs to enter the professional ranks.

As an oilman

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2008) |

Spinks described himself as a director of an oil company as of 1900. He invested money from his billiard equipment corporation in the petroleum industry in California.

As a farmer

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2008) |

While Spinks was not operating a farm as of 1900, he described himself as a flower farmer (among other such specialists in the area) in 1910, and an avocado "rancher" by 1920. As a pomology horticulturist, he developed the Spinks avocado cultivar. As a floriculurist, he made no known major contributions.

Private life

William A. Spinks, Jr., the youngest of five children, was born July 11, 1865 in the then-small township of San Jose, California, to struggling farmer William A. and wife Cynthia J. (Prather) Spinks. He had blue eyes, dark hair and a ruddy complexion, and was 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m) tall by adulthood. Nothing is known of his education.

On September 1, 1891 he married Clara Alexandria Karlson (b. December 12, 1871, Gothenburg, Sweden, immigrated 1872; d. October 4, 1949, Los Angeles); they were to remain together for over 40 years. They returned to California from Chicago before the turn of the century. After a period in a San Francisco apartment (ca. 1900), they lived in the (then-rural) L.A. suburbs of Duarte (ca. 1910) where their farm was, and later (by 1920) Monrovia, where they maintained a modest house in addition to the farm. After William's business success, the couple became extensive world travelers.

William Spinks died January 15, 1933, aged 67, in Monrovia.

In Los Angeles County's San Gabriel Valley, Spinks Canyon, its stream Spinks Canyon Creek, and the local major residential thoroughfare Spinks Canyon Road (running through Duarte's northernmost residential area, called "Duarte Mesa"), are named after William Spinks. He would probably be surprised that homes in the area can fetch over $1mil; his house in nearby Monrovia was valued at only $6,000 ($72,000 in 2007 dollars) in 1930.

References

- ^ "Billiard Cue Chalk Inventor Dead". Associated Press Newswire. New York City, NY: Associated Press. January 16, 1933. Retrieved 2006-11-25. Appeared in the San Antonio, Texas Express, Helena, Montana Daily Independent, New York Times, Huron, South Dakota Evening Huronite, Hagerstown, Maryland Daily Mail, and many other newspapers. The exact title and text varies from publication to publication – from 2 sentences to five paragraphs – due to editorial alterations to the newswire. The full version can be found in the Express and Daily Independent. Provides specific mention of Chicago factory; confirms involvement in oil industry, avocado growing, as well as birthplace and that he made a "fortune" on the chalk; also provides info on use of pre-Spinks chalk.

- ^ "W. A. Spinks Dies". International News Service. New York, NY: Hearst Corporation. January 16, 1933. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

{{cite journal}}:|section=ignored (help) Provides more specific death place; confirms Pacific Coast Champion titles; implies incorrectly that he died on January 16; mentions his world record, but off by 10 points. - ^ Cf. the New York Times pieces cited in more detail elsewhere in this article.

- ^ Clark, Neil M. (1927). "The World's Most Tragic Man Is the One Who Never Starts" ( – ). The American. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format=|month=ignored (help); republished in Hotwire: The Newsletter of the Toaster Museum Foundation, vol. 3, no. 3, online edition. The piece is largely an interview of Hoskins. (And there actually is a Toaster Museum, backed by a related foundation. They take the history of toast, and electrical heating in general, quite seriously.) - ^ U.S. patent 0,578,514, March 9, 1897

- ^ "Demarest Beats Veterans". New York Times. ibid.: p. 7 (below Syracuse & Sutton articles) January 14, 1909. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Short sports column. - ^ Shamos, Mike (1999). The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York: Lyons Press. ISBN 9781558217973 – via Internet Archive.

- Victor Stein & Paul Rubino (1996). "Tables, Cloths, and Balls". The Billiard Encyclopedia: An Illustrated History of the Sport (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Blue Book Publcations, Inc. pp. p. 240. ISBN 1-886768-06-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - "C.H.i.C. Timeline 1843–1880". A Guide to the Chemical History of Chicago. Chemical History in Chicago Project. date unspecified. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - "Substance Summary: Aluminum Oxide". PubChem Database. National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 2008. pp. "aloxite" and "corundum" search results. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- "Aloxite". ChemIndustry.com. 1999–2008. pp. Chemical Info database. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Russell, Michael (December 23, 2005). "Billiards — The Transformation Years: 1845-1897". Leisure and Sport Review. Retrieved 2008-08-19. (Also appears on several other sites.) This questionable article was obviously used as the source for the CSI season 6 episode "Time of Your Death", in which pool chalk plays a small but crucial role; the show perpetuated the "axolite" for "aloxite" error in that article, to millions of viewers. It is retained as a (red-flagged) source here specifically to document this fact, as the term "axolite" cannot be found anywhere else.

- U.S. patent 1,524,132, January 27, 1925

- "Ten Years Ago". Evening Times. Cumberland, MD: p. 4. January 15, 1943. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|section=ignored (help) Confirms "fortune". - ^ "Saw Good Billiards: Union Leaguers Entertained by Four Star Cue-wielders". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY: p. 8. December 20, 1893. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) The piece (as several others did) misspelled his surname as "Spink". Note: Each section of the newspaper page scans on this site can be clicked for a readable closeup. - Cf. the newspaper sources cited in more detail elsewhere in this article; no billiards-related coverage has been discovered so far pre-dating 1893.

- ^ Friedman, S. Morgan (2007). "The Inflation Calculator". WestEgg.com. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- "Spinks Will Meet McLaughlin". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. ibid.: p. 8 January 6, 1894. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "Spinks's Billiard Challenge". New York Times. New York, NY: New York Times Company: p. 6. November 5, 1894. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) A very short sports column note. NB: Though the article called the game "fourteen-inch balkline" it meant 14.2 balkline more specifically, because 14.1 was not introduced into tournaments until 1914. - "Billiard Notes". New York Times. ibid.: p. 7 (below Navy article) November 18, 1894. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Sports column entry. - McGrew, Clarence Alan (1922). ""Ora C. Morningstar" entry". City of San Diego and San Diego County: The Birthplace of California. Vol. Vol. 1. Chicago, IL & New York, NY: American Historical Society. pp. p. 364.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help) - "Schaefer Is in the Lead – The "Wizard" 32 Points Ahead of Ives, the Young Expert: Both Men Played Good, Strong Billiards and Ives Led Up to the Last Inning — Pretty Nursing by the Youthful Aspirant for Championship Honors — Ives Had the Best Average and the Highest Run in the Opening Night's Play". New York Times. ibid.: p. 2 February 25, 1894. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) An eyewitness summary of the first day of the match. The piece amply demonstrates the popularity of the sport at the time, as the in-depth article made the second page of the newspaper as a whole. - ^ "Billiards by the Experts". New York Times. ibid.: p. 12 (below real estate article) October 29, 1894. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Sports column entry. Cite error: The named reference "NYTSpinksLeads" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - "Crack Billiards Players in Tournament". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. ibid.: p. 4 February 22, 1895. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "Good Billiards Ahead: Maurice Daly Promises Great Things for This City". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. ibid.: p. 12 September 24, 1896. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "To Play 14-inch Balk Line". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. ibid.: p. 10 November 24, 1896. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) The event was originally slated to begin December 7. - "McLaughlin's Brilliant Run". New York Times. ibid.: p. 2 (below cricket article) December 10, 1896. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) A short sports column note. - "Spinks Still Ahead". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. ibid.: p. 10 December 11, 1896. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Sports column note. - "Spinks Wins at Billiards". New York Times. ibid.: p. 3 (below Platt article) December 12, 1896. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Another very short sports column note. - "Spinks Wins the Match". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. ibid.: p. 9 December 12, 1896. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Sports column note. - Colby, Frank Moore (1899). ""Billiards" entry". The International Year Book: A Compendium of the World's Progress in Every Department of Human Knowledge During the Year 1898. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead & Co. pp. p. 99. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Chicago Billiards Tourney". New York Times. ibid.: p. 4 January 15, 1898. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Another short sports column piece. - "Spinks Defeats Schaeffer ". New York Times. ibid.: p. 5 January 18, 1898. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Another short sport column piece. - "Chicago Billiard Tournament: Catton Defeats Spinks and Ives Defeats Sutton by 400 to 160". New York Times. ibid.: p. 5 January 19, 1898. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) More summary sports coverage. - "Chicago Billiard Tournament: Sutton Defeats Spinks, and Is Beaten by Schaefer". New York Times. ibid.: p. 4 January 20, 1898. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) More summary sports coverage. - "Chicago Billiard Tournament: Schaefer and Ives Win Games – The Former Breaks a Record". New York Times. ibid.: p. 10 January 21, 1898. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) More summary sports coverage. - "Billiard Titles in New Contests: Clearance of Clouds and Quibbles Promised in Winter Series of Games – Championships Are Lure – Challenge Match Between Sutton and Slosson Will Open Tilts and Lead to Open Tournament". New York Times. ibid.: p. S3 January 24, 1909. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|section=ignored (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Another in-depth piece that further demonstrates the popularity of carom billiards in its heyday and the seriousness with which it was treated by the media. It is notable that Spinks, Sutton, Slosson, Morningstar and Albert Cutler were simply given by name, while all others on the list were given by name and city (e.g. "Calvin Demarest of Chicago"), indicating that Spinks was a well-known public figure at this time. - "Surprise in Billiards: Spinks Scores Well-earned Victory Over Demarest in Final Inning". New York Times. ibid.: p. 10 (below NYAC article) January 12, 1909. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) A sports column piece. - "Two Games for Demarest". New York Times. ibid.: p. 8 (below New Orleans article) January 13, 1909. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) A very short sports column piece. - "Sutton to Practice at Daly's". New York Times. ibid.: p. 7 (below Syracuse article) January 14, 1909. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Short sports column. - "Sutton Wins and Loses". New York Times. ibid.: p. 9 (below McGann article) January 18, 1909. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Short sports column. - "Two Billiard Victories for Sutton". New York Times. ibid.: p. 7 (below Dartmouth article) January 21, 1909. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Short sports column. - "Sutton Scores a Double: Billiard Champ Beats Morningstar and Spinks in His Practice". New York Times. ibid.: p. 7 (below the Dartmouth article) January 23, 1909. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Short sports column. - "Sutton Wins Two Balkline Games". New York Times. ibid.: p. S1 (below the ice skating article) January 24, 1909. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|section=ignored (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Short sports page note. - Loy, Jim (2000). "The Chuck Nurse". Jim Loy's Billiards/Pool Page. Retrieved 2007-02-24. The Shamos source is the authoritative one, but this site provides an animated illustration of precisely how the chuck nurse works.

- "New Billiard Plan of Rating Players: Hoppe Will Lead the List—Handicaps for All of the Others". New York Times. ibid.: p. 9 August 5, 1915. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) The article refers to him as "W.M. Spinks of Los Angeles", a typo for "W.A." or "Wm.", and could not plausibly refer to anyone else, as there was no other notable W. Spinks in the billiards world of the period (or since), only two amateurs, C.A. and John Spinks, meanwhile William was the only Californian among them. - ^ ""William A. Spinks" and "Clara A. Spinks" entries (the only ones in California)". 1900 United States Federal Census. US Census Bureau, ibid. 1900. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Provides San Francisco residence, marital status, marriage year 1890–91, William's occupation as "oil company director"; confirms ages, birth places, no children; does not mention farm, or Clara's immigration year. - ^ ""William A. Spinks" entry in Los Angeles (the only there one, and the only one in California for that matter)". 1910 United States Federal Census. US Census Bureau, ibid. 1910. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Provides Duarte residence/farm, marriage year 1891–1892 (off by 1 compared to multiple other sources), Clara's immigration year, William's occupation as flower farmer (employer), land owned free and clear, neighbors engaged in flower farming; confirms marital status, no children, ages, birth places, parents' birth places. Copy is poor; data columns verified by comparison to legible blank 1910 census form. - ^ ""William A. Spinks" entry in Los Angeles (the only one there, and the only one in California)". 1920 United States Federal Census. US Census Bureau, ibid. 1920. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Provides Monrovia residence, William's occupation as avocado farmer, Clara's immigration date; confirms ages, marital status, birth places, no children, parents' birth places, free-owned home, Clara's immigration year. Copy is poor; data columns verified by comparison to legible blank 1920 census form. - ""William A. Spinks" entries in California (there are only two, father and son). Provides age of 5, birthplace, parents' names and birthplaces, mother's middle initial, father's occupation, siblings, father's assets ($2,000 in total estate value, did not own the land he worked, in contrast to most neighbors). Note: The full details of the search results from the URL provided for this and various other public records here are only available with a paid subscription to the search service, but are extant in their original paper forms for verification.". 1870 United States Federal Census. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau. 1870. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ^ "item "List of United States Citizens: SS Golden State, Departing from Hong Kong May 2, 1922, Arriving at Port of San Francisco"". Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, 1893-1953 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1410). Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85, National Archives, Washington, DC: US Immigration and Naturalization Service. 1954. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) Provides William's middle name, marriage date, Duarte residence overlapping with Monrovia (cf. 1920 Census); confirms Clara's middle name, William's birth place, birth dates of both. Cf. 1922 passport applications. Another ship manifest shows them returning from a trip to Italy in 1909, amusingly listing William's occupation simply as "capitalist". Another shows Clara returning from a visit to her native country of Sweden in 1937 (necessarily alone). Neither provide additional details, so are not cited here in full. Another, with both returning from England in 1925, again confirms that they retained the property in Duarte after getting the Monrovia house. All of the above are available as scans from Ancestry.com. - Braddock, Bruce. "Braddock Family Tree". Ancestry.com. The Generations Network. Retrieved 2008-08-20. Provides mother's maiden name. While a tertiary source, it agrees in every respect with vital records data. Note: The full details of the search results from the URL provided for this and various other public records here are only available with a paid subscription to the search service.

- "entries for "William A. Spinks" (1922), and "William A. Spinks" & "Clara A. Spinks" (1924).". Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1490). General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59, National Archives, Washington, DC: US Department of State. 1926. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) 1924: Provides full birth dates and places for both, photos of them, their height and appearance, William's occupation as "fruit grower", plans for whirlwind world tour including the British Isles, France, Italy, Japan, China, Hong Kong, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Egypt, India, Palestine, the Holy Land, Switzerland, Austria and Germany, for the purpose of "travel" (and "visit relatives" in the case of Clara), summer of 1924; confirms residence in Duarte (overlapping Monrovia), William's father's name and birthplace. 1922: Same confirmations, for William; photo of the couple together, travel plans for Japan, China, Hong Kong. - ^ ""William A. Spinks" entry in Los Angeles (the only one there, and the only one in California)". 1930 United States Federal Census. US Census Bureau, ibid. 1930. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Provides home value of $6,000 in Monrovia, non-veteran; confirms Monrovia residence, owned home, living on farm, William's occupation as avocado "rancher" (employer, active), marriage year 1880–1, ages, marital status, birth places, no children, parents' birth places. Copy is poor; data columns verified by comparison to legible blank 1930 census form. - California Death Index, 1940–1997. Sacramento, CA: Center for Health Statistics, Department of Health Services, State of California. 1998. Retrieved 2008-08-20. Provides Clara's maiden name, death date and place; confirms her birth date. Curiously, William does not appear in the index, despite have been reported to have died in Monrovia, L.A. County. It is therefore possible that he actually died in an out-of-state hospital.

- Beardshear, Laurie (December 13, 1973). "Area Street Names Traced to Pioneers". Star-News. Pasadena, CA: p. C3. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help)

| Cue sports | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pool games |  | |

| Carom billiards | ||

| Snooker | ||

| Other games | ||

| Resources | ||

| Major international tournaments |

| |

| Other events | ||

| Governing bodies | ||

| Categories | ||

The rules of games in italics are standardized by international sanctioning bodies. | ||

- American carom billiards players

- American farmers

- American inventors

- American oil industrialists

- American sports businesspeople

- California businesspeople

- Cue sports inventors and innovators

- Floriculturists

- Pomologists

- World record holders

- People from Brooklyn

- People from Chicago, Illinois

- People from Cincinnati, Ohio

- People from San Francisco, California

- People from San Jose, California

- 1865 births

- 1933 deaths

- People from Los Angeles County, California