| Revision as of 08:24, 8 November 2009 editPer Honor et Gloria (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers53,031 edits →Carolingian architecture: +← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:24, 23 November 2009 edit undoRussBot (talk | contribs)Bots1,407,994 editsm Robot-assisted: fix links to disambiguation page RomanNext edit → | ||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

| From ] times, various Islamic influences seem to appear in Christian religious architecture such as the multi-colored tile designs which may have been inspired by Islamic ] in the 800 CE gatehouse at ].<ref>''A world history of architecture'' Marian Moffett p.194 </ref> | From ] times, various Islamic influences seem to appear in Christian religious architecture such as the multi-colored tile designs which may have been inspired by Islamic ] in the 800 CE gatehouse at ].<ref>''A world history of architecture'' Marian Moffett p.194 </ref> | ||

| ] arches, as well as the centralized plan, found in Carolingian churches such as ] suggest influence from the ] architectural designs of Islamic Spain.<ref>''A world history of architecture'' Marian Moffett p.195 </ref> Early Carolingian architecture generally combines ], ], ], ] and ] designs.<ref>''A world history of architecture'' Marian Moffett p.195 </ref> | ] arches, as well as the centralized plan, found in Carolingian churches such as ] suggest influence from the ] architectural designs of Islamic Spain.<ref>''A world history of architecture'' Marian Moffett p.195 </ref> Early Carolingian architecture generally combines ], ], ], ] and ] designs.<ref>''A world history of architecture'' Marian Moffett p.195 </ref> | ||

| In the ] from 723 to 842, Islam and ] influenced a Christian movement towards the destruction of images this time, an event known as "]".<ref>''Adventures in Paranormal Investigation'' Joe Nickell p.222 </ref> According to ], it is the prestige of Islamic military successes in the 7-8th centuries that motivated Byzantine Christians into evaluating and adopting the Islamic precept of the destruction of idolatric images.<ref name="Toynbee">''A Study of History: Abridgement of volumes VII-X'' by Arnold Joseph Toynbee p.259 </ref> ] himself attempted to follow the iconoclastic precepts of the East Roman Emperor ], but this was stopped by ].<ref name="Toynbee"/> | In the ] from 723 to 842, Islam and ] influenced a Christian movement towards the destruction of images this time, an event known as "]".<ref>''Adventures in Paranormal Investigation'' Joe Nickell p.222 </ref> According to ], it is the prestige of Islamic military successes in the 7-8th centuries that motivated Byzantine Christians into evaluating and adopting the Islamic precept of the destruction of idolatric images.<ref name="Toynbee">''A Study of History: Abridgement of volumes VII-X'' by Arnold Joseph Toynbee p.259 </ref> ] himself attempted to follow the iconoclastic precepts of the East Roman Emperor ], but this was stopped by ].<ref name="Toynbee"/> | ||

Revision as of 16:24, 23 November 2009

An Abbasid-Carolingian alliance was attempted and partially formed during the 8th to 9th century through a series of embassies, rapprochements and combined military operations between the Frankish Carolingian Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate or the pro-Abbasid Muslim rulers in Spain. These contacts followed the intense conflict between the Carolingians and the Umayyads, marked by the landslide Battle of Tours in 732, and were aimed at establishing a counter-alliance with the faraway Abbasid Empire. Slightly later, another Carolingian-Abbasid alliance was attempted in a conflict against Byzantium.

Contacts under Pepin the Short

Embassies

Contacts started soon after the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate and the concommital fall of the Umayyad Caliphate in 751. The Carolingian ruler Pepin the Short had a powerful enough position in Europe to "make his alliance valuable to the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, al-Mansur". Former supporters of the Umayyad Caliphate were established firmly in southern Spain under Abd ar-Rahman I, and constituted a strategic threat both to the Carolingian on their southern border, and to the Abbasid at the western end of their dominion.

Embassies were exchanged both ways, with the apparent objective of cooperating against the Umayyads of Spain: a Frank embassy went to Baghdad in 765 which returned to Europe after three years with numerous presents, and an Abbasid embassy from Al-Mansur visited France in 768.

Commercial exchanges

Commercial exchanges occurred between the Carolingian and Abassid realms, and Arabic coins are known to have spread in Carolingian Europe in that period. Arab gold is reported to have circulated in Europe during the 9th century, apparently in payment of the export of slaves, timber, iron and weapons from Europe to Eastern lands. As a famous example, the 8th century English king Offa of Mercia is known to have minted copies of Abbasid dinars struck in 774 by Caliph Al-Mansur with "Offa Rex" centered on the reverse amid inscriptions in Pseudo-Kufic script.

Charlemagne's alliance

Military alliance in Spain (777-778)

In 777, pro-Abbasid rulers of northern Spain contacted the Carolingian to request help against the powerful Ummayyad Caliphate in southern Spain, still led by Abd ar-Rahman I. The "Spanish Abbasids sought support for their cause in Pepin's Francia; he was content to oblige because the Cordoban dynasty posed a constant military threat to southwestern France".

Sulayman al-Arabi the pro-Abbasid Wali (governor) of Barcelona and Girona sent a delegation to Charlemagne in Paderborn, offering his submission, together with the allegiance of Husayn of Zaragoza and Abu Taur of Huesca in return for military aid. The three Umayyad ruler also conveyed that the caliph of Baghdad, Muhammad al-Mahdi, was preparing an invasion force against Abd al-Rhaman I.

Following the sealing of this alliance at Paderborn, Charlemagne marched across the Pyrenees in 778 "at the head of all the forces he could muster". His troops were welcomed in Barcelona and Girona by Sulayman al-Arabi. As he moved towards Zaragoza, the troops of Charlemagne were joined by troops led by Sulayman. Husayn of Zaragoza, however, refused to surrender the city, claiming that he had never promised Charlemagne his allegiance. Meanwhile, the force sent by the Baghdad caliphate seems to have been stopped near Barcelona. After a month of siege at Zaragoza, Charlemagne decided to return to his kingdom. On his retreat, Charlemagne suffered an attack from the Basques in central Navarra. As a reprisal he attacked Pamplona, destroying it. However on his retreat north his baggage train was ambushed by the Basques at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass August 15, 778.

Carolingian presence remained south of the Pyrenees however, and the city of Girona was captured in 785, and they then concentrated on expanding their rule to Vich, Caserras and Cardona.

The Muslims made their last incursion in Gaul in 793, where they sacked the suburbs of Narbonne, and defeated William of Gellone, count of Toulouse near Carcassonne.

Later contacts

Charlemagne and Harun Al-Rashid exchanged numerous embassies and lavish presents.

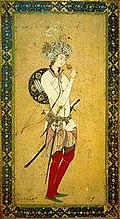

Charlemagne and Harun Al-Rashid exchanged numerous embassies and lavish presents.Left image: A coin of Charlemagne with the inscription KAROLVS IMP AVG (Karolus imperator augustus).

Right image: Persian miniature representing Harun Al-Rashid.

After these campaigns, there were again numerous embassies between Charlemagne and the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid from 797, apparently in view of a Carolingian-Abbasid alliance against Byzantium, or with a view to gaining an alliance against the Umayyads of Spain.

Strategic interest

Indeed, "Charles's conflict with the Umayyad Emir of Cordova made him an ally of the Abbasid emir of Baghdad, the celebrated Harun al-Rashid", and they were "forming a pact against a common enemy - namely the Muslim rulers in Umayyad Spain".

For Charlemagne, the alliance may also have functioned as a counterweight against the Byzantine Empire, which was opposed to his role in Italy and his claim to the title of Roman Emperor. For Harun al-Rashid, there was an advantage in having a partner against his rivals in Umayyad Spain.

Embassies

Three embassies were sent by Charlemagne to Harun al-Rashid's court and the latter sent at least two embassies to the Charlemagne. Harun al-Rashid is reported to have sent numerous presents to Charlemagne, such as aromatics, fabrics, a clock, a chessboard, and an elephant named Abu 'Abbas.

The 797 embassy, the first one from Charlemagne, was composed of three men, the Jew Isaac (Isaac Judaeus, probably as interpreter), Lantfrid and Sigimud, and Harun al-Rashid was described as "Aaron, king of the Persians". Four years later in 801, an Abassid embassy arrived in Pisa, composed of "a Persian from the East" and one envoy "Emir Abraham, probably Harun al-Rashid's governor in North Africa, Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab, with news about Jew Isaac that he was returning with numerous presents. They met with Charlemagne who was present in Italy at that time.

In 799, Charlemagne sent another mission to the Patriarch of Jerusalem.

Apparently led by encouragements from Spain, Louis the Pious, king of Aquitaine, captured Barcelona in 801, but failed to extend his conquests to Tortosa, which would remain Muslim for the next 300 years.

In 802, a second embassy was sent by Charlemagne, which returned in 806.

In 807, Rodbertus, Charlemagne's ambassador died as he returned from Persia. Harun al-Rashid is also reported to have offered the custody of the Holy places in Jerusalem to Charlemagne. In 807, Abdallah, "sent by the king of the Persian", reached Charlemagne in Aachen accompanied by two monks from Jerusalem, George (a German named Egilbaldus, prior of the Monastery of the Mount of Olives) and Felix, envoys of the Patriarch Thomas. They also brought many gifts, including a clock ("Horologium").

The third and final embassy was sent by Charlemagne in 809, but it arrived after Harun al-Rashid had died. The embassy returned in 813 with messages of friendship, but little concrete results.

Artistic influences

Further information: Islamic influences on Christian art

Left image: Great Mosque of Córdoba.

Left image: Great Mosque of Córdoba.Right image: Horseshoe arches in the Palatine Chapel in Aachen.

From Carolingian times, various Islamic influences seem to appear in Christian religious architecture such as the multi-colored tile designs which may have been inspired by Islamic polychromy in the 800 CE gatehouse at Lorsch Abbey.

Horseshoe arches, as well as the centralized plan, found in Carolingian churches such as Germigny-des-Prés suggest influence from the Mozarabic architectural designs of Islamic Spain. Early Carolingian architecture generally combines Roman, Early Christian, Byzantine, Islamic and Northern European designs.

In the Byzantine Empire from 723 to 842, Islam and Judaism influenced a Christian movement towards the destruction of images this time, an event known as "Iconoclasm". According to Arnold Toynbee, it is the prestige of Islamic military successes in the 7-8th centuries that motivated Byzantine Christians into evaluating and adopting the Islamic precept of the destruction of idolatric images. Charlemagne himself attempted to follow the iconoclastic precepts of the East Roman Emperor Leo Syrus, but this was stopped by Pope Hadrian I.

Aftermath

It seems that in 831, Harun al-Rashid's son al Ma'mun also sent an embassy to Louis the Pious. These embassies also seems to have had the objective of promoting commerce between the two realms.

After 814 and the accession of Louis the Pious to the throne, internal dissensions prevented the Carolingians from further ventures into Spain.

Almost a century later Bertha of Savoy, the consort of Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor is reported to have sent an embassy to the Abbasid caliph Al-Muktafi, requesting friendship and a marital alliance.

Notes

- Heck, p.172

- Shalem, p.94-95

- Carolingian Chronicles by Bernhard Walter Scholz, p.16

- ^ Deanesly, p.294

- Goody, p.80

- Charlemagne, Muhammad, and the Arab roots of capitalism by Gene W. Heck p.179-181

- British Museum

- Medieval European Coinage By Philip Grierson p.330

- ^ Lewis, p.244

- Mohammed, Charlemagne, and the Origins of Europe Richard Hodges, p.120

- Lewis, p.245

- ^ Lewis, p.246

- Lewis, p.253

- ^ Lewis, p.249

- Lewis, p.251-267

- O'Callaghan, p.106

- ^ O'Callaghan, p.106

- Heck, p. 172

- ^ Heck, p. 172

- Carolingian Chronicles by Bernhard Walter Scholz p.16

- Beyond the Arab disease by Riad Nourallah p.51

- Creating East and West by Nancy Bisaha p.207

- Charlemagne and the Early Middle Ages by Miriam Greenblatt, p.29

- A History of Palestine, 634-1099 by Moshe Gil, Ethel Broido p.286

- ^ Gil, p.286

- War And Peace in the Law of Islam by Majid Khadduri, p.247

- ^ Mohammed, Charlemagne, and the Origins of Europe Richard Hodges, p.121

- A world history of architecture Marian Moffett p.194

- A world history of architecture Marian Moffett p.195

- A world history of architecture Marian Moffett p.195

- Adventures in Paranormal Investigation Joe Nickell p.222

- ^ A Study of History: Abridgement of volumes VII-X by Arnold Joseph Toynbee p.259

- ^ Heck, p. 173

- M. Hamidullah, "An Embassy of Queen Bertha to Caliph al-Muktafi billah in Baghdad 293/906", Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, I, 1953, pp 272-300.

References

- Margaret Deanesly A History of Early Medieval Europe Taylor & Francis, London Methuen & Co, Ltd

- David Levering Lewis God's Crucible Islam and the Making of Europe, 570-1215 W.W. Norton, 2008 ISBN 9780393064728

- Gene W. Heck When worlds collide: exploring the ideological and political foundations of the clash of civilizations Rowman & Littlefield, 2007 ISBN 0742558568

- Jack Goody Islam in Europe, Polity Press, 2004, ISBN 9780745631936

- Joseph F. O'Callaghan A History of Medieval Spain Cornell University Press, 1983 ISBN 0801492645

- Moshe Gil, Ethel Broido A History of Palestine, 634-1099 Cambridge University Press, 1997 ISBN 0521599849