| Revision as of 11:16, 27 January 2016 view sourceCFCF (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers35,046 edits From the CDC page, Public domain contentTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:37, 27 January 2016 view source AlbinoFerret (talk | contribs)11,178 edits remove claim only in the lede, copy reference to Safety page where claim is already covered.Next edit → | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| <!-- Health effects --> | <!-- Health effects --> | ||

| The benefits and the ] are uncertain.<ref name=EbbertAgunwamba2015>{{cite journal |last1=Ebbert |first1=Jon O. |last2=Agunwamba |first2=Amenah A. |last3=Rutten |first3=Lila J. |title=Counseling Patients on the Use of Electronic Cigarettes |journal=Mayo Clinic Proceedings |volume=90 |issue=1 |year=2015 |pages=128–134 |issn=00256196 |doi=10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.004 |pmid=25572196}}</ref><ref name=Siu2015/><ref name=Harrell2014/> There is tentative evidence that they can help people ],<ref name=Cochrane2014>{{cite journal |last1=McRobbie |first1=Hayden |last2=Bullen |first2=Chris |last3=Hartmann-Boyce |first3=Jamie |last4=Hajek |first4=Peter |last5=McRobbie |first5=Hayden |title=Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction |journal=The Cochrane Library |year=2014 |volume=12 |pages=CD010216 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2 |pmid=25515689}}</ref> but they have not been proven better than regulated medication.<ref name=Harrell2014/> Their usefulness in ] is unclear,<ref name=Drummond2014>{{cite journal |last1=Drummond |first1=M.B. |last2=Upson |first2=D |title=Electronic cigarettes: Potential harms and benefits |journal=Annals of the American Thoracic Society |date=February 2014 |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=236–42 |doi=10.1513/annalsats.201311-391fr |pmid=24575993}}</ref> but they could form part of future strategies to ].<ref name=Kacker2014/><ref name=Caponnetto2013>{{cite journal |title=Electronic cigarette: a possible substitute for cigarette dependence |journal=Monaldi archives for chest disease |date=Mar 2013 |author1=Caponnetto P. |author2=Russo C. |author3=Bruno C.M. |author4=Alamo A. |author5=Amaradio M.D. |author6=Polosa R. |volume=79 |issue=1 |pages=12–19 |pmid=23741941 |doi=10.4081/monaldi.2013.104}}</ref> Their safety risk to users is similar to that of ].<ref name=Caponnetto2013/> Regulated ] are safer than e-cigarettes,<ref name=Drummond2014/> but e-cigarettes are probably safer than smoking.<ref name=Golub2015>{{cite journal |last1=Golub |first1=Justin S. |last2=Samy |first2=Ravi N. |title=Preventing or reducing smoking-related complications in otologic and neurotologic surgery |journal=Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery |volume=23 |issue=5 |year=2015 |pages=334–340 |issn=1068-9508 |doi=10.1097/MOO.0000000000000184 |pmid=26339963}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- Safety --> | <!-- Safety --> | ||

Revision as of 14:37, 27 January 2016

Electronic cigarettes are battery-powered vaporizers that simulate the feeling of smoking, but without tobacco. Their use is commonly called "vaping". The user activates the e-cigarette by taking a puff or pressing a button. Some look like traditional cigarettes, but they come in many variations. Most are reusable but there are also disposable versions called first generation cigalikes. There are also second, third, and fourth generation devices. Instead of cigarette smoke, the user inhales an aerosol, commonly called vapor. E-cigarettes typically have a heating element that atomizes a liquid solution known as e-liquid. E-liquids usually contain propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, and flavorings.

The benefits and the health risks of e-cigarettes are uncertain. There is tentative evidence that they can help people quit smoking, but they have not been proven better than regulated medication. Their usefulness in tobacco harm reduction is unclear, but they could form part of future strategies to decrease tobacco related death and disease. Their safety risk to users is similar to that of smokeless tobacco. Regulated nicotine replacement products are safer than e-cigarettes, but e-cigarettes are probably safer than smoking.

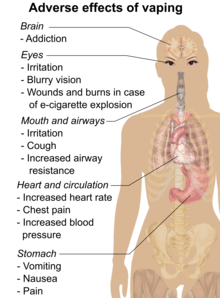

Nicotine is associated with a range of harmful effects. Non-smokers who use e-cigarettes risk nicotine addiction and their use may delay or deter quitting smoking. E-cigarettes create vapor consisting of ultrafine particles. The vapor contains similar chemicals to the e-liquid, together with tiny amounts of toxicants and heavy metals. The composition of the vapor varies across and within manufacturers. E-cigarette vapor can contain harmful chemicals not found in tobacco smoke. Later-generation e-cigarettes may generate more formaldehyde than tobacco does, but reduced voltage e-cigarettes produce very low levels of formaldehyde. E-cigarette vapor contains fewer toxic substances than cigarette smoke. It also has lower concentrations of potential toxic substances than cigarette smoke, and is probably less harmful to users and bystanders. No serious adverse effects from e-cigarettes have been reported in trials. Less serious adverse effects include throat and mouth inflammation, vomiting, nausea, and cough. The long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown.

Since their introduction to the market in 2004, global usage has risen exponentially. As of 2014, about 13% of American high school students have used them at least once in the last month. As of mid-2015 around 10% of American adults are current users of e-cigarettes. In the UK user numbers have increased from 700,000 in 2012 to 2.6 million in 2015. Most US e-cigarette users still smoke traditional cigarettes. About 60% of UK users are smokers and about 40% are ex-smokers, while use among never-smokers remains "negligible". Most peoples' reason for using e-cigarettes is related to quitting, but a considerable proportion use them recreationally. The modern e-cigarette arose from a 2003 invention by Hon Lik in China and as of 2015 most devices are made there. Because of the potential relationship with tobacco laws and medical drug policies, e-cigarette legislation is being debated in many countries. The European Parliament passed regulations in February 2014, to come into effect by 2016, standardizing liquids and personal vaporizers, listing ingredients, and child-proofing liquid containers. The US FDA published proposed regulations in April 2014 with some similar measures. As of 2014, there were 466 brands with sales of around $7 billion.

Use

Frequency

Since their introduction to the market in 2004, global usage of e-cigarettes has risen exponentially. By 2013, there were several million users globally. Awareness and use of e-cigarettes greatly increased over the few years to 2014, particularly among young people and women in some countries. But in both the US and UK the growth in usage seemed to have slowed in 2015.

In the US, vaping among young people exceeded smoking in 2014. In 2014, it was projected that vaping would exceed smoking in about three decades. People with higher incomes are more likely to have heard of e-cigarettes, but those with lower incomes are more likely to have tried them. Trying e-cigarettes was common among less educated people. Whites are more likely to use them than non-whites. Most users have a history of smoking regular cigarettes. At least 52% of current or former smokers have used e-cigarettes. Of smokers who use e-cigarettes, less than 15% turn into everyday e-cigarette users. E-cigarette use in never-smokers is very low but is rising. A 2015 review suggests that 1% of e-cigarette users use liquid without nicotine. As of 2014, up to 13% of American high school students had used them at least once in the last month, and around 3.4% of American adults as of 2011.

In the UK user numbers have increased from 700,000 in 2012 to 2.6 million in 2015, but use by current smokers remained flat at 17.6% from 2014 into 2015 (in 2010 it was 2.7%). About 60% of UK users are smokers and about 40% are ex-smokers, while use among never-smokers remains "negligible".

The majority of e-cigarette users use them every day. E-cigarette users mostly keep smoking traditional cigarettes. Many say e-cigarettes help them cut down or quit smoking. Adults often vape to replace tobacco, but not always to quit. Most e-cigarette users are middle-aged men who also smoke traditional cigarettes, either to help them quit or for recreational use. Among young adults e-cigarette use is not regularly associated with trying to quit smoking. E-cigarette use is also rising among women. Women smokers who are poorer and did not finish high school are more likely to have tried vaping. Dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional tobacco is still a definite concern. There is wide concern that vaping may be a "gateway" to smoking. A 2014 review raised ethical concerns about minors' e-cigarette use and the potential to weaken cigarette smoking reduction efforts.

In the US, the recent fall in smoking has accompanied a rapid growth in the use of alternative nicotine products among young people and young adults. 56% of respondents in a US 2013 survey admitted having used e-cigarettes to quit or reduce their smoking, and 26% of respondents would use them in areas where smoking was banned. In the US, as of 2014, 12.6% of adults have used an e-cigarette at least once and about 3.7% are still using them. Among grade 6 to 12 students in the US, the proportion who have tried them rose from 3.3% in 2011 to 6.8% in 2012. Those still vaping over the last month rose from 1.1% to 2.1% and dual use rose from 0.8% to 1.6%. Over the same period the proportion of grade 6 to 12 students who regularly smoke tobacco fell from 7.5% to 6.7%.

Use frequency has risen: as of 2012, up to 10% of American high school students have used them. In 2013 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that around 160,000 students between 2011 to 2012 who had tried vaping had never smoked. Between 2013 and 2014, vaping among students tripled. The majority of young people who vape also smoke. E-cigarette use among never-smoking youth in the US correlates with elevated desires to use traditional cigarettes.

About one in 20 adults in the UK uses e-cigarettes. In the UK in 2015, 18% of regular smokers said they used e-cigarettes and 59% said they had used them in the past. Among those who had never smoked, 1.1% said they had tried them and 0.2% still use them. In 2013, among those under 18, 7% have used e-cigarettes at least once. Among non-smokers' children, 1% reported having tried e-cigarettes "once or twice", and there was no evidence of continued use. About 60% of all users are smokers and most of the rest are ex-smokers, with "negligible" numbers of never-smokers. In 2015 figures showed around 2% monthly EC-usage among under-18s, and 0.5% weekly, and despite experimentation, "nearly all those using EC regularly were cigarette smokers". 10-11-year-old Welsh never-smokers are more likely to use e-cigarettes if a parent used e-cigarettes.

In France, a 2014 survey estimated between 7.7 and 9.2 million people had tried e-cigarettes and 1.1 to 1.9 million use them on a daily basis. The same survey also found 67% of smokers used e-cigarettes to reduce or quit smoking. Of respondents who indicated they tried e-cigarettes, 9% said they had never smoked tobacco. Of the 1.2% who had recently stopped tobacco smoking at the time of the survey, 84% (or 1% of the population surveyed) credited e-cigarettes as essential in quitting.

Many young people who use e-cigarettes also smoke tobacco. Some young people who have tried an e-cigarette have never smoked tobacco, so ECs can be a starting point for nicotine use. There are high levels of dual use with e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes. Some young people who have never smoked have tried e-cigarettes at least once. Most young people are not using e-cigarettes to help them quit tobacco. Teenagers who had used an e-cigarette were more inclined to become smokers than those who had not. Young people who vape are more likely to use hookah and blunts than smokers.

Motivation

Reasons for e-cigarette usage often relate to quitting cigarettes, relaxation, and recreation. While many vapers believe usage is healthier than smoking for themselves and bystanders, some are concerned about the possible adverse health effects. Others use them to circumvent smoke-free laws and policies, or to cut back on cigarette smoking. Not having odor from smoke on clothes on some occasions prompted interest in or use of e-cigarettes. E-cigarette users have contradictory views about using them to get around smoking bans.

Users sometimes use e-cigarettes without nicotine around friends for the convenience. Non-smoking adults tried e-cigarettes due to curiosity, because a relative was using them, or because they were given an e-cigarette. College students often vape for experimentation. Expensive marketing aimed at smokers suggests e-cigarettes are "newer, healthier, cheaper and easier to use in smoke-free situations, all reasons that e-cigarette users claim motivate their use". Exposure to e-cigarette advertising influenced people to try them.

If tobacco businesses persuade women that e-cigarettes are a small risk, women might vape while pregnant. The belief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes could widen their use among pregnant women. E-cigarettes feel or taste similar to traditional cigarettes, and vapers disagreed about whether this was a benefit or a drawback. The majority of committed e-cigarette users interviewed at an e-cigarette convention found them cheaper than traditional cigarettes.

Some users stopped vaping due to issues with the devices. Dissatisfaction and concerns over safety can discourage ongoing e-cigarette use. Some surveys found that a small percentage of users' motives were to avoid smoking bans, but other surveys found that over 40% of users said they used the device for this reason. The extent to which traditional cigarette users vape to avoid smoking bans is unclear.

The health and lifestyle appeal may also encourage young non-smokers to use e-cigarettes, as they may perceive that trying e-cigarettes is less risky and more socially appealing. This may ameliorate negative beliefs or concerns about nicotine addiction. Marketing might appeal to young people as well as adults. Adolescent experimenting with e-cigarettes may be sensation seeking behavior, and is not likely to be associated with tobacco reduction or quitting smoking. Young people may view e-cigarettes as a symbol of rebellion. The main reasons young people experimented with e-cigarettes were due to curiosity, flavors, and peer influences. Some advocates say there is concern that e-cigarettes could be appealing to youth because of their high-tech design, assortment of flavors, and accessibility online. At least one advocacy group claims that candy and fruit flavors e-cigarettes are designed to appeal to young people. Infants and toddlers could ingest the e-liquid from an e-cigarette device out of curiosity.

Users may begin by using a disposable e-cigarette, and e-cigarette users often start with e-cigarettes resembling normal cigarettes, eventually moving to a later-generation device. Most later-generation e-cigarette users shifted to their present device to get a "more satisfying hit", and users may adjust their devices to provide more vapor for better "throat hits".

Construction

A. LED light cover

B. battery (also houses circuitry)

C. atomizer (heating element)

D. cartridge (mouthpiece)

The primary parts that make up an e-cigarette are a mouthpiece, a cartridge (tank), a heating element/atomizer, a microprocessor, a battery, and possibly a LED light on the end. An atomizer comprises a small heating element that vaporizes e-liquid and wicking material that draws liquid onto the coil. When the user pushes a button, or (in some variations) activates a pressure sensor by inhaling, the heating element that atomizes the liquid solution; The e-liquid reaches a temperature of roughly 100-250 °C within a chamber to create an aerosolized vapor. The user inhales the aerosol, commonly called vapor, rather than cigarette smoke. The aerosol provides a flavor and feel similar to tobacco smoking.

There are three main types of e-cigarettes: cigalikes, looking like cigarettes; eGos, bigger than cigalikes with refillable liquid tanks; and mods, assembled from basic parts or by altering existing products. As the e-cigarette industry is growing, new products are quickly developed and brought to market. First generation e-cigarettes tend to look like tobacco cigarettes and so are called "cigalikes". Most cigalikes look like cigarettes but there is some variation in size. A traditional cigarette is smooth and light while a cigalike is rigid and slightly heavier. Second generation devices are larger overall and look less like tobacco cigarettes. Third generation devices include mechanical mods and variable voltage devices. The fourth generation includes Sub ohm tanks and temperature control devices. The power source is the biggest component of an e-cigarette, which is frequently a rechargeable lithium battery.

Health effects

Positions of medical organizations

Main article: Positions of medical organizations on electronic cigarettes

Physicians and public health officials have been concerned about the health implications of e-cigarette use. Numerous medical organizations have made statements about their health and safety. All agree that more research is needed. Some healthcare groups have hesitated to recommend e-cigarettes for quitting smoking, because of limited evidence of effectiveness and safety. In July 2014, a report produced by the World Health Organization (WHO) found there was not enough evidence to determine if electronic cigarettes could help people quit smoking, suggesting smokers be encouraged to use approved methods for help with quitting. The same report also notes expert opinion which suggests e-cigarettes have a role in helping those who have failed to quit by other means. Smokers will get the maximum health benefit if they completely quit all nicotine use. The World Lung Foundation has applauded the WHO report's recommendation of tighter regulation due to safety concerns and the risk of increased nicotine or tobacco addiction among youth.

In a 2015 joint statement, Public Health England and twelve other UK medical bodies concluded "e-cigarettes are significantly less harmful than smoking." In 2015, Public Health England released a report stating that e-cigarettes are estimated to be 95% less harmful than smoking, and said that "PHE looks forward to the arrival on the market of a choice of medicinally regulated products that can be made available to smokers by the NHS on prescription." The UK National Health Service followed with the statement that e-cigarettes have approximately 5% of the risk of tobacco cigarettes, while also concluding that there won't be a complete understanding of their safety for many years. As of 2014 there are clinical trials in progress to test the quality, safety and effectiveness of e-cigarettes, but until these are complete the NHS maintains that the government could not give any advice on them or to recommend their use.

In October 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends against e-cigarettes for quitting smoking and stated among adolescents, e-cigarette use is related with reduced quitting smoking. In August 2014, the American Heart Association released a policy statement in which they support "effective FDA regulation of e-cigarettes that addresses marketing, youth access, labeling, quality control over manufacturing, free sampling, and standards for contaminants." In 2015 the California Department of Public Health issued a report that stated the "aerosol has been found to contain at least ten chemicals that are on California’s Proposition 65 list of chemicals known to cause cancer, birth defects, or other reproductive harm." In 2014, the US FDA said "E-cigarettes have not been fully studied, so consumers currently don't know: the potential risks of e-cigarettes when used as intended, how much nicotine or other potentially harmful chemicals are being inhaled during use, or whether there are any benefits associated with using these products. Additionally, it is not known whether e-cigarettes may lead young people to try other tobacco products, including conventional cigarettes, which are known to cause disease and lead to premature death."

Smoking cessation

The available research on the safety and efficacy of e-cigarette use for smoking cessation is limited and the evidence is contradictory. Some medical authorities recommend that e-cigarettes have a role in smoking cessation, and others disagree. Views of e-cigarettes' role range from on the one hand Public Health England, who recommend that stop-smoking practitioners should:- (1) advise people who want to quit to try e-cigarettes if they are not succeeding with conventional NRT; and (2) advise people who cannot or do not want to quit to switch to e-cigarettes to reduce smoking-related disease to, on the other hand, the United States Preventive Services Task Force that advised only use of conventional NRTs in smoking cessation and found insufficient evidence to recommend e-cigarettes for this purpose.

A 2016 meta-analysis based on 20 different studies found that those smokers who had used electronic cigarettes were 28 % less likely to quit than those who had not tried electronic cigarettes. This finding persisted whether not the smokers where initially interested in quitting or not. A 2015 meta-analysis on clinical trials of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation found that e-cigarettes containing nicotine are more effective than those that do not. They compared their finding that nicotine-containing e-cigarettes helped 20% of people quit with the results from other studies that found conventional NRTs help 10% of people quit. There has only been one study directly comparing first generation e-cigarettes to conventional NRT as smoking cessation tools so the comparative effectiveness is not known.

However, e-cigarettes have not been subject to the same efficacy testing as nicotine replacement products. Several authorities, including the World Health Organisation, take the view that there is not enough evidence to recommend e-cigarettes for quitting smoking in adults, and there are studies showing a decline in smoking cessation among dual users. A 2014 review found that e-cigarettes do not seem to improve cessation rates compared to regulated nicotine replacement products, and a trial found 29% of e-cigarette users were still vaping at 6 months, but only 8% of patch users still wore patches at 6 months.

Harm reduction

Tobacco harm reduction (THR) is the replacement of tobacco cigarettes with lower risk products to reduce tobacco related death and disease. THR has been controversial out of fear that tobacco companies cannot be trusted to produce and market products that will reduce the risks associated with tobacco use. E-cigarettes can reduce smokers' exposure to carcinogens and other toxic substances found in tobacco. Tobacco smoke contains 100 known carcinogens, and 900 potentially cancer causing chemicals, none of which has been found in more than trace quantities in the cartridges or aerosol of e-cigarettes. According to a 2011 review, while e-cigarettes cannot be considered "safe" because there is no safe level for carcinogens, they are doubtless safer than tobacco cigarettes.

A core concern is that smokers who could have quit completely will develop an alternative nicotine addiction instead. A 2014 review stated that promotion of vaping as a harm reduction aid is premature, but in an effort to decrease tobacco related death and disease, e-cigarettes have a potential to be part of the harm reduction strategy. Another review found e-cigarettes would likely be less harmful than traditional cigarettes to users and bystanders. The authors warned against the potential harm of excessive regulation and advised health professionals to consider advising smokers who are reluctant to quit by other methods to switch to e-cigarettes as a safer alternative to smoking. A 2015 Public Health England report concluded that e-cigarettes "release negligible levels of nicotine into ambient air with no identified health risks to bystanders". A 2014 review recommended that regulations for e-cigarettes could be similar to those for dietary supplements or cosmetic products to not limit their potential for harm reduction. A 2012 review found e-cigarettes could considerably reduce traditional cigarettes use and they likely could be used as a lower risk replacement for traditional cigarettes, but there is not enough data on their safety and efficacy to draw definite conclusions. E-cigarette use for risk reduction in high-risk groups such as people with mental disorders is unavailable.

A 2014 Public Health England report concluded that there is large potential for health benefits when switching from tobacco use to other nicotine delivery devices such as e-cigarettes, but realizing their full potential requires regulation and monitoring to minimize possible risks. They found that a considerable number of smokers want to reduce harm from smoking by using these products. The British Medical Association encourages health professionals to recommend conventional nicotine replacement therapies, but for patients unwilling to use or continue using such methods, health professionals may present e-cigarettes as a lower-risk option than tobacco smoking. The American Association of Public Health Physicians (AAPHP) suggests those who are unwilling to quit tobacco smoking or unable to quit with medical advice and pharmaceutical methods should consider other nicotine containing products such as electronic cigarettes and smokeless tobacco for long term use instead of smoking. In an interview, the director of the Office on Smoking and Health for the U.S. federal agency Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) believes that there is enough evidence to say that using e-cigarettes is likely less harmful than smoking a pack of conventional cigarettes. However, due to the lack of regulation of the contents of e-cigarettes and the presence of nicotine, the CDC has issued warnings. A 2014 WHO report concluded that some smokers will switch completely to e-cigarettes from traditional tobacco but a "sizeable" number will use both. This report found that such "dual use" of e-cigarettes and tobacco "will have much smaller beneficial effects on overall survival compared with quitting smoking completely."

Safety

Main articles: Safety of electronic cigarettes and Electronic cigarette aerosol and e-liquid

The safety of electronic cigarettes is uncertain. There is little data about their health effects, and considerable variability between vaporizers and in quality of their liquid ingredients and thus the contents of the aerosol delivered to the user. Reviews on the safety of electronic cigarettes have reached different conclusions. In July 2014 the World Health Organization (WHO) report cautioned about potential risks of using e-cigarettes. Regulated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) products such as nicotine inhalers are probably safer than e-cigarettes. In 2015, Public Health England stated that e-cigarettes are estimated to be 95% less harmful than smoking. A 2014 systematic review concluded that the risks of e-cigarettes have been exaggerated by health authorities and stated that while there may be some remaining risk, the risk of e-cigarette use is likely small compared to smoking tobacco.

The long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown. A 2014 Cochrane review found no serious adverse effects reported in trials. Less serious adverse effects from e-cigarette use include throat and mouth inflammation, vomiting, nausea, and cough. The evidence suggests they produce less harmful effects than tobacco. A 2014 WHO report said, "ENDS use poses serious threats to adolescents and fetuses." Aside from toxicity, there are also risks from misuse or accidents such as contact with liquid nicotine, fires caused by vaporizer malfunction, and explosions as result from extended charging, unsuitable chargers, or design flaws. Battery explosions are caused by an increase in internal battery temperature and some have resulted in severe skin burns. There is a small risk of battery explosion in devices modified to increase battery power.

The e-liquid has a low level of toxicity, and contamination with various chemicals has been identified in the product. E-cigarette vapor contains fewer toxic substances, and lower concentrations of potential toxic substances than cigarette smoke. Metal parts of e-cigarettes in contact with the e-liquid can contaminate it with metals. Normal usage of e-cigarettes generates very low levels of formaldehyde. A 2015 review found that later-generation e-cigarettes set at higher power may generate equal or higher levels of formaldehyde compared to smoking. A 2015 review found that these levels were the result of overheating under test conditions that bear little resemblance to common usage. The 2015 Public Health England report looking at the research concluded that by applying maximum power and increasing the time the device is used on a puffing machine, e-liquids can thermally degrade and produce high levels of formaldehyde. Users detect the "dry puff" and avoid it, and the report concluded that "There is no indication that EC users are exposed to dangerous levels of aldehydes." E-cigarette users are exposed to potentially harmful nicotine. Nicotine is associated with cardiovascular disease, potential birth defects, and poisoning. In vitro studies of nicotine have associated it with cancer, but carcinogenicity has not been demonstrated in vivo. There is inadequate research to demonstrate that nicotine is associated with cancer in humans. The risk is probably low from the inhalation of propylene glycol and glycerin. No information is available on the long-term effects of the inhalation of flavors.

E-cigarettes create vapor that consists of ultrafine particles, with the majority of particles in the ultrafine range. The vapor has been found to contain flavors, propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, tiny amounts of toxicants, carcinogens, heavy metals, and metal nanoparticles, and other chemicals. Exactly what comprises the vapor varies in composition and concentration across and within manufacturers. However, e-cigarettes cannot be regarded as simply harmless. There is a concern that some of the mainstream vapor exhaled by e-cigarette users can be inhaled by bystanders, particularly indoors. E-cigarette use by a parent might lead to inadvertent health risks to offspring. A 2014 review recommended that e-cigarettes should be regulated for consumer safety. There is limited information available on the environmental issues around production, use, and disposal of e-cigarettes that use cartridges. A 2014 review found "disposable e-cigarettes might cause an electrical waste problem."

E-liquid

E-liquid is the mixture used in vapor products such as e-cigarettes. The main ingredients in the e-liquid usually are propylene glycol, glycerin, water, nicotine, and flavorings. However, there are e-liquids sold without propylene glycol, nicotine, or flavors. The liquid typically contains 95% propylene glycol and glycerin. The flavorings may be natural or artificial. About 8,000 flavors exist as of 2014. There are many e-liquids manufacturers in the USA and worldwide. While there are currently no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) manufacturing standards for e-liquid, the FDA has proposed regulations that are expected to be finalized in late 2015. Industry standards have been created and published by the American E-liquid Manufacturing Standards Association (AEMSA).

Addiction

Nicotine is very addictive, comparable to heroin or cocaine. Nicotine induces strong effects on the brain, which lead to considerable changes in the brain’s physiology such as stimulation in regions of the cortex associated with reward, pleasure and reducing anxiety. When nicotine intake stops, there are withdrawal symptoms.

Various organizations are concerned that vaping might increase nicotine addiction and use among young people. These include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Food and Drug Administration. The World Health Organization raised concern about addiction for non-smokers from their use in July 2014. The National Institute on Drug Abuse said they could maintain nicotine addiction in those who are attempting to quit.

It is not clear whether vaping will decrease or increase overall nicotine addiction. Information about the drug action of the nicotine in e-cigarettes is limited, but the nicotine in e-cigarettes is adequate to sustain nicotine dependence. The limited data suggests that the likelihood of abuse from e-cigarettes could be smaller than traditional cigarettes. A 2014 systematic review found that the concerns that e-cigarettes could cause non-smokers to start smoking are unsubstantiated. No long-term studies have been done on the effectiveness of e-cigarettes in treating tobacco addiction. Some evidence suggests that dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes may be associated with greater nicotine dependence.

A 2014 review found no evidence that they are used regularly by those who have never smoked, while another 2014 review has found that in studies up to a third of young people who have ever vaped have never smoked tobacco. The degree to which teens are using e-cigarettes in ways the manufacturers did not intend, such as increasing the nicotine delivery, is unknown. The extent to which e-cigarette use will lead to addiction or substance dependence in youth is unknown. Youthful experimentation with e-cigarettes could lead to a lifelong addiction.

Nicotine yield

Smoking a traditional cigarette yields between 0.5 and 1.5 mg of nicotine, but the nicotine content of the cigarette is only weakly correlated with the levels of nicotine in the smoker's bloodstream. The amount of nicotine in the e-cigarette aerosol varies widely either from puff-to-puff or among products of the same company. In practice vapers tend to reach lower blood nicotine concentrations than smokers, particularly when the vapers are inexperienced or using earlier-generation devices. Nicotine in tobacco smoke is absorbed into the bloodstream rapidly, and e-cigarette vapor is relatively slow in this regard. The concentration of nicotine in e-liquid ranges up to 36 mg/mL. New EU regulations cap this at a maximum of 2% (20 mg/mL), but this is an arbitrary ceiling based on limited data. In practice the nicotine concentration in an e-liquid is not a reliable guide to the amount of nicotine that reaches the bloodstream.

History

The earliest e-cigarette can be traced to American Herbert A. Gilbert, who in 1963 patented "a smokeless non-tobacco cigarette" that involved "replacing burning tobacco and paper with heated, moist, flavored air". This device produced flavored steam without nicotine. The patent was granted in 1965. Gilbert’s invention was ahead of its time. There were prototypes, but it received little attention and was never commercialized because smoking was still fashionable at that time. Gilbert said in 2013 that today's electric cigarettes follow the basic design set forth in his original patent.

Hon Lik, a Chinese pharmacist and inventor, who worked as a research pharmacist for a company producing ginseng products, is credited with the invention of the modern e-cigarette. Lik quit smoking after his father, also a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer. In 2003, he thought of using a high frequency, piezoelectric ultrasound-emitting element to vaporize a pressurized jet of liquid containing nicotine. This design creates a smoke-like vapor. Lik said that using resistance heating obtained better results and he said the difficulty was to scale down the device to a small enough size. Lik’s invention was intended to be an alternative to smoking.

Hon Lik patented the modern e-cigarette design in 2003. Lik is credited with developing the first commercially successful electronic cigarette. The e-cigarette was first introduced to the Chinese domestic market in 2004. Many versions made their way to the U.S., sold mostly over the Internet by small marketing firms. The company that Lik worked for, Golden Dragon Holdings, changed its name to Ruyan (如烟, literally "Resembling smoking"), and started exporting its products in 2005–2006 before receiving its first international patent in 2007. Ruyan changed its company name to Dragonite International Limited. Lik said in 2013 that "I really hope that the large international pharmaceutical groups get into manufacturing electronic cigarettes and that authorities like the FDA in the United States will continue to impose stricter and stricter standards so that the product will be as safe as possible." Most e-cigarettes today use a battery-powered heating element rather than the ultrasonic technology patented design from 2003.

Hon Lik sees the e-cigarette as comparable to the "digital camera taking over from the analogue camera." He has said "My fame will follow the development of the e-cigarette industry. Maybe in 20 or 30 years I will be very famous." Many US and Chinese e-cig makers copied his designs illegally, so Lik was not paid for his invention (although some US manufacturers have compensated him through out of court settlements). The company had sold e-cigarettes and e-cigars.

The e-cigarette continued to evolve from the first generation three-part device. In 2007 British entrepreneurs Umer and Tariq Sheikh invented the cartomizer. This is a mechanism that integrates the heating coil into the liquid chamber. They launched this new device in the UK in 2008 under their Gamucci brand and the design is now widely adopted by most "cigalike" brands. The grant of the UK patent for the "cartomizer" was made to XL Distributors in February 2013 and published by the UK Intellectual Property Office. The clearomizer was invented in 2009 that originated from the cartomizer design. It contained the wicking material, an e-liquid chamber, and an atomizer coil within a single clear component. The clearomizer allows the user to monitor the liquid level in the device. E-cigarettes entered the European market and the US market in 2006 and 2007.

| Tobacco company | Subsidiary company | Electronic cigarette |

|---|---|---|

| Imperial Tobacco | Fontem Ventures and Dragonite | Puritane blu eCigs |

| British American Tobacco | CN Creative and Nicoventures | Vype |

| R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company | R. J. Reynolds Vapor Company | Vuse |

| Altria | Nu Mark, LLC | MarkTen |

| Japan Tobacco International | Ploom | E-lites LOGIC |

International tobacco companies, recognizing the development of a potential new market sector that could render traditional tobacco products obsolete, are increasingly involved in the production and marketing of their own brands of e-cigarettes and in acquiring existing e-cigarette companies. blu eCigs, a prominent US e-cigarette manufacturer, was acquired by Lorillard Inc. in 2012. British American Tobacco launched Vype in 2013, while Imperial Tobacco's Fontem Ventures acquired the intellectual property owned by Hon Lik through Dragonite International Limited for $US 75 million in 2013 and launched Puritane in partnership with Boots UK. On 1 October 2013 Lorillard Inc. acquired another e-cigarette company, this time the UK based company SKYCIG. SKY was rebranded as blu. On 3 February 2014, Altria Group, Inc. acquired popular electronic cigarette brand Green Smoke for $110 million. The deal was finalized in April 2014 for $110 million with $20 million in incentive payments. Altria also markets its own e-cigarette, the MarkTen, while Reynolds American has entered the sector with its Vuse product. On 30 April 2015, Japan Tobacco bought the US Logic e-cigarette brand. Japan Tobacco also bought the UK E-Lites brand in June 2014. On 15 July 2014, Lorillard sold blu to Imperial Tobacco as part of a deal for $7.1 billion. As of March 2015, 74% of all e-cigarette sales in convenience stores in the U.S. were products made by tobacco companies. As of May 2015, 80% were products made by tobacco companies.

In the UK in 2015 the "most prominent brands of cigalikes" were owned by tobacco companies, but except for one model all the tank types came from "non-tobacco industry companies". However some tobacco industry products, while using prefilled cartridges, resemble tank models.

Society and culture

Consumers of e-cigarettes, sometimes called "vapers", have shown passionate support for the device that other nicotine replacement therapy did not receive. This suggests e-cigarettes have potential mass appeal that could challenge combustible tobacco's market position.

As the electronic cigarette industry grows, a subculture has emerged which calls itself "the vaping community". The online forum E-Cig-Reviews.com was one of the first major communities. Another online forum known as UKVaper.org was the origin of the hobby of modding. There are also groups on Facebook and Reddit. Members of this emerging subculture often see e-cigarettes as a safer alternative to smoking and some view it as a hobby. These groups tend to use highly customized devices that do not resemble the earlier "cig-a-likes". Online forums based around modding have grown in the vaping community. Vapers energetically embrace activities associated with e-cigarettes and sometimes act as unpaid evangelicals according to a 2014 review. A 2014 Postgraduate Medical Journal editorial stated that e-cigarette companies have a substantial online presence, as well as many individual vapers who blog and tweet about e-cigarette related products. The editorial stated that vapers "also engage in grossly offensive online attacks on anyone who has the temerity to suggest that ENDS are anything other than an innovation that can save thousands of lives with no risks". A 2014 review stated that tobacco and e-cigarette companies interact with consumers for their policy agenda. The companies use websites, social media, and marketing to get consumers involved in opposing bills that include e-cigarettes in smoke-free laws. The same review said this is similar to tobacco industry activity going back to the 1980s. These approaches were used in Europe to minimize the EU Tobacco Product Directive in October 2013. True grassroots lobbying also influenced the TPD decision. Rebecca Taylor, a member of the European Parliament, stated, "to say it’s an orchestrated campaign is absolute rubbish."

Large gatherings of vapers, called vape meets, take place around the US. They focus on e-cig devices, accessories, and the lifestyle that accompanies them. Vapefest, which started in 2010, is an annual show hosted by different cities. People attending these meetings are usually enthusiasts that use specialized, community-made products not found in convenience stores or gas stations. These products are mostly available online or in dedicated "vape" storefronts where mainstream e-cigarettes brands from the tobacco industry and larger e-cig manufacturers are not as popular. Some vape shops have a vape bar where patrons can test out different e-liquids and socialize. The Electronic Cigarette Convention in North America which started in 2013, is an annual show where companies and consumers meet up. As of 2014, e-cigarette availability in US stores is increasing, especially in places with low taxes and smoking bans. In the US they are more likely available in places with a higher median family income.

A growing subclass of vapers called "cloud-chasers" configure their atomizers to produce large amounts of vapor by using low-resistance heating coils. This practice is called "cloud-chasing" and is growing more popular. By using a coil with very low resistance, the batteries are stressed to a potentially unsafe extent. This could present a risk of dangerous battery failures. As vaping comes under increased scrutiny, some members of the vaping community have voiced their concerns about cloud-chasing, claiming the practice gives vapers a bad reputation when doing it in public. The Oxford Dictionaries' word of the year for 2014 is "vape".

Regulation

Main articles: Regulation of electronic cigarettes and List of vaping bans in the United States

Regulation of e-cigarettes varies across countries and states, ranging from no regulation to banning them entirely. As of 2015, around two thirds of major nations have regulated e-cigarettes in some way. Because of the potential relationship with tobacco laws and medical drug policies, e-cigarette legislation is being debated in many countries. Regulators are currently evaluating the research on e-cigarettes.

The legal status of e-cigarettes is currently pending in many countries. Some countries such Brazil, Singapore, the Seychelles, and Uruguay have banned e-cigarettes. In Canada, they are technically illegal to sell, as no nicotine-containing e-fluid is approved by Health Canada, but this is generally unenforced and they are commonly available for sale Canada-wide. In the US and the UK, the use and sale of e-cigarettes are legal.

In February 2014 the European Parliament passed regulations requiring standardization and quality control for liquids and vaporizers, disclosure of ingredients in liquids, and child-proofing and tamper-proofing for liquid packaging. In April 2014 the US FDA published proposed regulations for e-cigarettes along similar lines. In the US, as of 2014 some states tax e-cigarettes as tobacco products, and some state and regional governments have broadened their indoor smoking bans to include e-cigarettes. As of 9 October 2015, at least 48 states and 2 territories banned e-cigarette sales to minors.

E-cigarettes have been listed as drug delivery devices in several countries because they contain nicotine, and their advertising has been restricted until safety and efficacy clinical trials are conclusive. Since they do not contain tobacco, television advertising in the US is not restricted. Some countries have regulated e-cigarettes as a medical product even though they have not approved them as a smoking cessation aid. As of 2014 electronic cigarettes had not been approved as a smoking cessation device by any government. A 2014 review stated the emerging phenomenon of e-cigarettes has raised concerns in the health community, governments, and the general public and recommended that e-cigarettes should be regulated to protect consumers. It added, "heavy regulation by restricting access to e-cigarettes would just encourage continuing use of much unhealthier tobacco smoking." A 2014 review said these products should be considered for regulation in view of the "reported adverse health effects".

Marketing

A 2014 review said, "the e-cigarette companies have been rapidly expanding using aggressive marketing messages similar to those used to promote cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s." E-cigarettes and nicotine are regularly promoted as safe and beneficial in the media and on brand websites. While advertising of tobacco products is banned in most countries, television and radio e-cigarette advertising in some countries may be indirectly encouraging traditional cigarette smoking. There is no evidence that the cigarette brands are selling e-cigarettes as part of a plan to phase out traditional cigarettes, despite some claiming to want to cooperate in "harm reduction". In the US, six large e-cigarette businesses spent $59.3 million on promoting e-cigarettes in 2013. Easily circumvented age verification at company websites enables young people to access and be exposed to marketing for e-cigarettes.

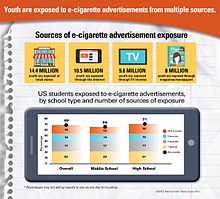

A national US television advertising campaign starred Steven Dorff exhaling a "thick flume" of what the ad describes as "vapor, not tobacco smoke", exhorting smokers with the message "We are all adults here, it's time to take our freedom back." The ads, in a context of longstanding prohibition of tobacco advertising on TV, were criticized by organizations such as Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids as undermining anti-tobacco efforts. Cynthia Hallett of Americans for Non-Smokers' Rights described the US advertising campaign as attempting to "re-establish a norm that smoking is okay, that smoking is glamorous and acceptable". University of Pennsylvania communications professor Joseph Cappella stated that the setting of the ad near an ocean was meant to suggest an association of clean air with the nicotine product. In 2012 and 2013, e-cigarette companies advertised to a large television audience in the US which included 24 million youth. The channels on which e-cigarette advertising reached the largest numbers of youth (ages 12–17) were AMC, Country Music Television, Comedy Central, WGN America, TV Land, and VH1.

A 2014 review said e-cigarettes are aggressively promoted, mostly via the internet, as a healthy alternative to smoking in the US. Celebrity endorsements are used to encourage e-cigarette use. "Big tobacco" markets e-cigarettes to young people, with industry strategies including cartoon characters and candy flavors to sell e-cigarettes. E-cigarette companies commonly promote that their products contain only water, nicotine, glycerin, propylene glycol, and flavoring but this assertion is misleading as scientists have found differing amounts of heavy metals in the vapor, including chromium, nickel, tin, silver, cadmium, mercury, and aluminum. The assertion that e-cigarette emit "only water vapor" is false because the evidence indicates e-cigarette vapor contains possibly harmful chemicals such as nicotine, carbonyls, metals, and organic volatile compounds, in addition to particulates.

Economics

As of 2014 the number of e-cigarettes sold has increased every year. In 2015, a slowdown in the growth in usage occurred in both the US and the UK As of 2014 there were at least 466 e-cigarette companies. Worldwide e-cigarette sales in 2014 were around US$7 billion., yet it is expected to continue to rise, and even exceed traditional cigarette sales by 2047. In the US, tobacco producers have a significant share of the e-cigarette market, and they are the major producers.

Tobacco manufacturers dismissed e-cigarettes as a fad at first; but the purchase of the US brand blu eCigs by US tobacco manufacturer Lorillard for $135 million in April 2012 signaled their entry into the market. Tobacco companies have bought some e-cigarette businesses and greatly increased their marketing efforts. As of 2015 e-cigarette devices are mostly made in China. A 2015 review said there are more than a hundred small e-cigarette businesses in the US, with about 70% of the market held by 10 businesses. A sizable share of the e-cigarette business is done on the internet. The majority of e-cigarette businesses have their own homepage and approximately 30–50% of total e-cigarettes sales are handled on the internet in respect to English-language websites.

Canada is an expanding market for e-cigarettes. There are numerous e-cigarette retail shops in Canada. In 2013, the company Smoke NV was the leading seller of e-cigarette products in Canada. Smoke NV does not sell vapor products containing nicotine.

The UK is a growing market for e-cigarettes. Key e-cigarette businesses in the UK in 2014 were British American Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco, Nicocigs, and Vivid Vapours. British American Tobacco was the first tobacco business to sell e-cigarettes in the UK. They launched the e-cigarette Vype in July 2013. Philip Morris, the world’s largest tobacco firm, purchased UK’s Nicocigs in June 2014. In March 2014 the top selling e-cigarette brands in the UK at independent convenience stores were Nicolites and Vivid Vapours.

France is a growing market for e-cigarettes, which is said to be about €100 million (£85 million) in sales as of 2013. In 2013, there were about 150 e-cigarette retail shops there.

According to Nielsen Holdings, convenience store e-cigarette sales in the US went down for the first time during the four-week period ending on 10 May 2014. Wells Fargo analyst Bonnie Herzog attributes this decline to a shift in consumers' behavior, buying more specialized devices or what she calls "vapor/tank/mods (VTMs)" that are not tracked by Nielsen. According to Herzog these products, produced and sold by stand alone makers are now (2014) growing twice as fast as traditional electronic cigarettes marketed by the major players (Lorillard, Logic Technology, NJOY, etc.) Wells Fargo estimated that VTMs accounted for 57% of the 3.5 billion dollar market in the US for vapor products in 2015. In 2014, the Smoke-Free Alternatives Trade Association estimated that there were 35,000 vape shops in the US, more than triple the number a year earlier.

Related technologies and alternatives

Other devices to deliver inhaled nicotine have been developed. They aim to mimic the ritual and behavioral aspects of traditional cigarettes.

British American Tobacco, through their subsidiary Nicoventures Limited, licensed a nicotine delivery system based on existing asthma inhaler technology from UK-based healthcare company Kind Consumer Limited. In September 2014 a product based on this named Voke obtained approval from the United Kingdom's Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency.

Philip Morris International (PMI) bought the rights to a nicotine pyruvate technology developed by Jed Rose at Duke University. The technology is based on the chemical reaction between pyruvic acid and nicotine, which produces an inhalable nicotine pyruvate vapor.

PAX Labs has developed vaporizers that heats the leaves of tobacco to deliver nicotine in a vapor. On 1 June 2015, they introduced Juul a different type of e-cigarette which delivers 10 times as much nicotine as other e-cigarettes, equivalent to an actual cigarette puff.

BLOW started selling e-hookahs, an electronic version of the hookah, in 2014.

Several companies including Canada's Eagle Energy Vapor are selling caffeine-based e-cigarettes instead of nicotine.

References

- Footnotes

- Variously also known as ECs, e-cigs, e-cigarettes, personal vaporizers (PVs), or electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS)

- Philip Morris International sells Atria's vaping products outside of the US, while Altria only sells two e-cigarette brands in the US.

- Citations

- ^ Caponnetto, Pasquale; Campagna, Davide; Papale, Gabriella; Russo, Cristina; Polosa, Riccardo (2012). "The emerging phenomenon of electronic cigarettes". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 6 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1586/ers.11.92. ISSN 1747-6348. PMID 22283580.

- ^ Orellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- ^ "Electronic cigarettes: patterns of use, health effects, use in smoking cessation and regulatory issues". Tob Induc Dis. 12 (1): 21. 2014. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-12-21. PMC 4350653. PMID 25745382.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Grana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- ^ Pepper, J. K.; Brewer, N. T. (2013). "Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions and beliefs: a systematic review". Tobacco Control. 23 (5): 375–384. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24259045.

- ^ Bhatnagar, A.; Whitsel, L.P.; Ribisl, K.M.; Bullen, C.; Chaloupka, F.; Piano, M.R.; Robertson, R.M.; McAuley, T.; Goff, D.; Benowitz, N. (24 August 2014). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 130 (16): 1418–1436. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000107. PMID 25156991.

- ^ Hayden McRobbie (2014). "Electronic cigarettes" (PDF). National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training. pp. 1–16.

- ^ Farsalinos KE, Spyrou A, Tsimopoulou K, Stefopoulos C, Romagna G, Voudris V (2014). "Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: Comparison between first and new-generation devices". Scientific Reports. 4: 4133. doi:10.1038/srep04133. PMC 3935206. PMID 24569565.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Konstantinos Farsalinos. "Electronic cigarette evolution from the first to fourth generation and beyond" (PDF). gfn.net.co. Global Forum on Nicotine. p. 23. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Cheng, T. (2014). "Chemical evaluation of electronic cigarettes". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii11 – ii17. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051482. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995255. PMID 24732157.

- ^ Weaver, Michael; Breland, Alison; Spindle, Tory; Eissenberg, Thomas (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 8 (4): 234–240. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000043. ISSN 1932-0620. PMID 25089953.

- ^ Cooke, Andrew; Fergeson, Jennifer; Bulkhi, Adeeb; Casale, Thomas B. (2015). "The Electronic Cigarette: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 3 (4): 498–505. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.05.022. ISSN 2213-2198. PMID 26164573.

- ^ Oh, Anne Y.; Kacker, Ashutosh (December 2014). "Do electronic cigarettes impart a lower potential disease burden than conventional tobacco cigarettes?: Review on e-cigarette vapor versus tobacco smoke". The Laryngoscope. 124 (12): 2702–2706. doi:10.1002/lary.24750. PMID 25302452.

- ^ Brandon, T.H.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Hanna, N.H.; Hatsukami, D.K.; Herbst, R.S.; Hobin, J.A.; Ostroff, J.S.; Shields, P.G.; Toll, B.A.; Tyne, C.A.; Viswanath, K.; Warren, G.W. (2015). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: A Policy Statement from the American Association for Cancer Research and the American Society of Clinical Oncology". Clinical Cancer Research. 21: 514–525. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2544. ISSN 1078-0432. PMID 25573384.

- ^ McRobbie, Hayden; Bullen, Chris; Hartmann-Boyce, Jamie; Hajek, Peter; McRobbie, Hayden (2014). "Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction". The Cochrane Library. 12: CD010216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2. PMID 25515689.

- ^ Ebbert, Jon O.; Agunwamba, Amenah A.; Rutten, Lila J. (2015). "Counseling Patients on the Use of Electronic Cigarettes". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (1): 128–134. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.004. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 25572196.

- ^ Siu, A.L. (22 September 2015). "Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of internal medicine. 163: 622–34. doi:10.7326/M15-2023. PMID 26389730.

- ^ Harrell, P.T.; Simmons, V.N.; Correa, J.B.; Padhya, T.A.; Brandon, T.H. (4 June 2014). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems ("E-cigarettes"): Review of Safety and Smoking Cessation Efficacy". Otolaryngology—head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 151: 381–393. doi:10.1177/0194599814536847. PMID 24898072.

- ^ Drummond, M.B.; Upson, D (February 2014). "Electronic cigarettes: Potential harms and benefits". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 11 (2): 236–42. doi:10.1513/annalsats.201311-391fr. PMID 24575993.

- ^ Caponnetto P.; Russo C.; Bruno C.M.; Alamo A.; Amaradio M.D.; Polosa R. (March 2013). "Electronic cigarette: a possible substitute for cigarette dependence". Monaldi archives for chest disease. 79 (1): 12–19. doi:10.4081/monaldi.2013.104. PMID 23741941.

- Golub, Justin S.; Samy, Ravi N. (2015). "Preventing or reducing smoking-related complications in otologic and neurotologic surgery". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 23 (5): 334–340. doi:10.1097/MOO.0000000000000184. ISSN 1068-9508. PMID 26339963.

- ^ "E-cigarettes: Safe to recommend to patients?". Cleve Clin J Med. 82 (8): 521–6. 2015. doi:10.3949/ccjm.82a.14054. PMID 26270431.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ WHO. "Electronic nicotine delivery systems" (PDF). pp. 1–13. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Hajek, P.; Etter, J.F.; Benowitz, N.; Eissenberg, T.; McRobbie, H. (31 July 2014). "Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit" (PDF). Addiction (Abingdon, England). 109 (11): 1801–10. doi:10.1111/add.12659. PMID 25078252.

- ^ Hildick-Smith, Gordon J.; Pesko, Michael F.; Shearer, Lee; Hughes, Jenna M.; Chang, Jane; Loughlin, Gerald M.; Ipp, Lisa S. (2015). "A Practitioner's Guide to Electronic Cigarettes in the Adolescent Population". Journal of Adolescent Health. 57: 574–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.020. ISSN 1054-139X. PMID 26422289.

- ^ Bekki, Kanae; Uchiyama, Shigehisa; Ohta, Kazushi; Inaba, Yohei; Nakagome, Hideki; Kunugita, Naoki (2014). "Carbonyl Compounds Generated from Electronic Cigarettes". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (11): 11192–11200. doi:10.3390/ijerph111111192. ISSN 1660-4601. PMID 25353061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Fernández, Esteve; Ballbè, Montse; Sureda, Xisca; Fu, Marcela; Saltó, Esteve; Martínez-Sánchez, Jose M. (2015). "Particulate Matter from Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Cigarettes: a Systematic Review and Observational Study". Current Environmental Health Reports. 2: 423–9. doi:10.1007/s40572-015-0072-x. ISSN 2196-5412. PMID 26452675.

- ^ Rom, Oren; Pecorelli, Alessandra; Valacchi, Giuseppe; Reznick, Abraham Z. (2014). "Are E-cigarettes a safe and good alternative to cigarette smoking?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1340 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1111/nyas.12609. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 25557889.

- ^ "E-cigarette use triples among middle and high school students in just one year". CDC. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Mincer, Jilian (10 June 2015). "E-cigarette usage surges in past year: Reuters/Ipsos poll".

- ^ "Use of electronic cigarettes (vaporisers) among adults in Great Britain" (PDF). ASH UK. May 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Barbara Demick (25 April 2009). "A high-tech approach to getting a nicotine fix". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Alawsi, F.; Nour, R.; Prabhu, S. (2015). "Are e-cigarettes a gateway to smoking or a pathway to quitting?". BDJ. 219 (3): 111–115. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.591. ISSN 0007-0610. PMID 26271862.

- ^ Saitta, D; Ferro, GA; Polosa, R (March 2014). "Achieving appropriate regulations for electronic cigarettes". Therapeutic advances in chronic disease. 5 (2): 50–61. doi:10.1177/2040622314521271. PMC 3926346. PMID 24587890.

- ^ Etter, J. F.; Bullen, C.; Flouris, A. D.; Laugesen, M.; Eissenberg, T. (May 2011). "Electronic nicotine delivery systems: a research agenda". Tobacco control. 20 (3): 243–8. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.042168. PMC 3215262. PMID 21415064.

- ^ "Questions & Answers: New rules for tobacco products". European Commission. 26 February 2014.

- "Electronic Cigarettes (e-Cigarettes)". FDA. 11 August 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Peter Evans (20 February 2015). "E-Cigarette Makers Face Rise of Counterfeits". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Backgrounder on WHO report on regulation of e-cigarettes and similar products". 26 August 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Michael Felberbaum (11 June 2013). "Marlboro Maker To Launch New Electronic Cigarette". The Huffington Post.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Schraufnagel, Dean E.; Blasi, Francesco; Drummond, M. Bradley; Lam, David C. L.; Latif, Ehsan; Rosen, Mark J.; Sansores, Raul; Van Zyl-Smit, Richard (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes. A Position Statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 190 (6): 611–618. doi:10.1164/rccm.201407-1198PP. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 25006874.

- ^ Mickle, Tripp (17 November 2015). "E-cig sales rapidly lose steam". E-Cigarette Sales Rapidly Lose Steam. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ West, Robert; Beard, Emma; Brown, Jamie (10 August 2015). "Electronic cigarettes in England - latest trends (STS140122)". Smoking in England. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Pisinger, Charlotta; Døssing, Martin (December 2014). "A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes". Preventive Medicine. 69: 248–260. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.009. PMID 25456810.

- ^ Carroll Chapman, SL; Wu, LT (18 March 2014). "E-cigarette prevalence and correlates of use among adolescents versus adults: A review and comparison". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 54: 43–54. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.005. PMID 24680203.

- ^ Bullen, Christopher (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes for Smoking Cessation". Current Cardiology Reports. 16 (11): 538. doi:10.1007/s11886-014-0538-8. ISSN 1523-3782. PMID 25303892.

- ^ Born, H.; Persky, M.; Kraus, D.H.; Peng, R.; Amin, M.R.; Branski, R.C. (2015). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Primer for Clinicians". Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 153: 5–14. doi:10.1177/0194599815585752. ISSN 0194-5998. PMID 26002957.

- Suter, Melissa A.; Mastrobattista, Joan; Sachs, Maike; Aagaard, Kjersti (2015). "Is There Evidence for Potential Harm of Electronic Cigarette Use in Pregnancy?". Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 103 (3): 186–195. doi:10.1002/bdra.23333. ISSN 1542-0752. PMID 25366492.

- ^ "E-cigarettes: an up to date review and discussion of the controversy". W V Med J. 110 (4): 10–5. 2014. PMID 25322582.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Franck, C.; Budlovsky, T.; Windle, S.B.; Filion, K. B.; Eisenberg, M.J. (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes in North America: History, Use, and Implications for Smoking Cessation". Circulation. 129 (19): 1945–1952. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006416. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 24821825.

- ^ Lauterstein, Dana; Hoshino, Risa; Gordon, Terry; Watkins, Beverly-Xaviera; Weitzman, Michael; Zelikoff, Judith (2014). "The Changing Face of Tobacco Use Among United States Youth". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 7 (1): 29–43. doi:10.2174/1874473707666141015220110. ISSN 1874-4737. PMID 25323124.

- "Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults: United States, 2014" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 2015. pp. 1–8.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (November 2013). "Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011 and 2012". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 62 (45): 893–7. PMID 24226625.

- Sabrina Tavernise (17 April 2015). "Use of e-cigarettes rising sharply among teenagers". The Boston Globe.

- Arrazola, RA; Neff, LJ; Kennedy, SM; Holder-Hayes, E; Jones, CD (14 November 2014). "Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2013". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 63 (45): 1021–1026. PMID 24699766.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E – cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Use of electronic cigarettes in Great Britain" (PDF). ASH. ASH. July 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- "Over 2 million Britons now regularly use electronic cigarettes". ASH UK. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E – cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. pp. 31–34. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Moore, G. F.; Littlecott, H. J.; Moore, L.; Ahmed, N.; Holliday, J. (2014). "E-cigarette use and intentions to smoke among 10-11-year-old never-smokers in Wales". Tobacco Control. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052011. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 25535293.

- Volkow, Nora (August 2015). "Teens Using E-cigarettes More Likely to Start Smoking Tobacco". National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- ^ "Prévalence, comportements d'achat et d'usage, motivations des utilisateurs de la cigarette électronique" (PDF). Observatoire Français des Drogues et des Toxicomanies. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Schraufnagel, Dean E. (2015). "Electronic Cigarettes: Vulnerability of Youth". Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology. 28 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1089/ped.2015.0490. ISSN 2151-321X. PMID 25830075.

- ^ Linda Bauld, Kathryn Angus, Marisa de Andrade (May 2014). "E-cigarette uptake and marketing" (PDF). Public Health England. pp. 1–19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Regulation of Electronic Cigarettes ("E-Cigarettes")" (PDF). National Association of County and City Health Officials.

- ^ "Heart and Stroke Foundation: E-cigarettes in Canada". Heart and Stroke Foundation.

- "Are e-cigarettes safe to puff?". CBC News. 19 June 2013.

- ^ Crowley, Ryan A. (2015). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: Executive Summary of a Policy Position Paper From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (8): 583–4. doi:10.7326/M14-2481. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 25894027.

- ^ England, Lucinda J.; Bunnell, Rebecca E.; Pechacek, Terry F.; Tong, Van T.; McAfee, Tim A. (2015). "Nicotine and the Developing Human". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. ISSN 0749-3797. PMID 25794473.

- ^ ""Smoking revolution": a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites". Am J Prev Med. 46 (4): 395–403. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010. PMID 24650842.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Kong, G.; Morean, M.E.; Cavallo, D.A.; Camenga, D.R.; Krishnan-Sarin, S. (2014). "Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 17: 847–54. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu257. ISSN 1462-2203. PMID 25481917.

- Kevin Chatham-Stephens (20 October 2014). "Young Children and e-Cigarette Poisoning". Medscape.

- ^ Yingst, J. M.; Veldheer, S.; Hrabovsky, S.; Nichols, T. T.; Wilson, S. J.; Foulds, J. (2015). "Factors associated with electronic cigarette users' device preferences and transition from first generation to advanced generation devices". Nicotine Tob Res. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv052. ISSN 1462-2203. PMID 25744966.

- "Electronic Cigarette Fires and Explosions" (PDF). U.S. Fire Administration. 2014. pp. 1–11.

- "Vaper Talk – The Vaper's Glossary". Spinfuel eMagazine. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ Rowell, Temperance R.; Tarran, Robert (2015). "Will Chronic E-Cigarette Use Cause Lung Disease?". American Journal of Physiology – Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology: ajplung.00272.2015. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00272.2015. ISSN 1040-0605. PMID 26408554.

- Glasser, A. M.; Cobb, C. O.; Teplitskaya, L.; Ganz, O.; Katz, L.; Rose, S. W.; Feirman, S.; Villanti, A. C. (2015). "Electronic nicotine delivery devices, and their impact on health and patterns of tobacco use: a systematic review protocol". BMJ Open. 5 (4): e007688 – e007688. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007688. ISSN 2044-6055. PMID 25926149.

- ^ Bhatnagar, A.; Whitsel, L. P.; Ribisl, K. M.; Bullen, C.; Chaloupka, F.; Piano, M.R.; Robertson, R. M.; McAuley, T.; Goff, D.; Benowitz, N. (24 August 2014). "AHA Policy Statement - Electronic Cigarettes". Circulation. 130 (16): 1418–1436. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000107.

- "More than a quarter-million youth who had never smoked a cigarette used e-cigarettes in 2013". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ "E-cigarette Ads and Youth". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "WHO Right to Call for E-Cigarette Regulation". World Lung Federation. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ "E-cigarettes: an emerging public health consensus". UK: Public Health England. 2015.

- ^ McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E – cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. p. 76. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "E – cigarettes: a new foundation for evidence – based policy and practice" (PDF). Public Health England. 19 August 2015. p. 5. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Electronic cigarettes". Smokefree NHS. Are e-cigarettes safe to use?. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "Stop smoking treatments". UK National Health Service. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- "Clinical Practice Policy to Protect Children From Tobacco, Nicotine, and Tobacco Smoke" (PDF). PEDIATRICS. 136 (5): 1008–1017. 2015. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3108. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 26504137.

- ^ "State Health Officer's Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat" (PDF). California Department of Public Health, California Tobacco Control Program. January 2015.

- "Electronic Cigarettes (e-Cigarettes)". US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- "CDC launches powerful new ads in "Tips From Former Smokers" campaign". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 26 March 2015.

- ^ Kalkhoran, Sara; Glantz, Stanton A. "E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00521-4. PMID 26776875.

- ^ Rahman, Muhammad Aziz (30 March 2015). "E-Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation: Evidence from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 10: e0122544. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122544. PMID 25822251.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Saitta, D.; Ferro, G.A.; Polosa, R. (3 February 2014). "Achieving appropriate regulations for electronic cigarettes". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 5 (2): 6. doi:10.1177/2040622314521271. PMC 3926346. PMID 24587890.

- ^ M., Z.; Siegel, M. (February 2011). "Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: a step forward or a repeat of past mistakes?". Journal of public health policy. 32 (1): 16–31. doi:10.1057/jphp.2010.41. PMID 21150942.

- McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E – cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. p. 65. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "E-cigarettes—prevention, pulmonary health, and addiction". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 111 (20): 349–55. 2014. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2014.0349. PMC 4047602. PMID 24882626.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Britton, John; Bogdanovica, Ilze (15 May 2014). "Electronic cigarettes – A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). Public Health England.

- "BMA calls for stronger regulation of e-cigarettes" (PDF). British Medical Association. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- "Principles to Guide AAPHP Tobacco Policy". American Association of Public Health Physicians. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ^ Edgar, Julie. "E-Cigarettes: Expert Q&A With the CDC". WebMD. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Detailed reference list is located on a separate image page.

- ^ Palazzolo, Dominic L. (November 2013). "Electronic cigarettes and vaping: a new challenge in clinical medicine and public health. A literature review". Frontiers in Public Health. 1 (56). doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00056. PMC 3859972. PMID 24350225.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Odum, L.E.; O'Dell, K.A.; Schepers, J.S. (December 2012). "Electronic cigarettes: do they have a role in smoking cessation?". Journal of pharmacy practice. 25 (6): 611–4. doi:10.1177/0897190012451909. PMID 22797832.

- O'Connor, R.J. (March 2012). "Non-cigarette tobacco products: what have we learnt and where are we headed?". Tobacco control. 21 (2): 181–90. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050281. PMC 3716250. PMID 22345243.

- Farsalinos, Konstantinos E; Le Houezec, Jacques (29 September 2015). "Regulation in the face of uncertainty: the evidence on electronic nicotine delivery systems (e-cigarettes)". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 2015 (8): 157–167. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S62116. PMC 4598199. PMID 26457058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Farsalinos, K.E.; Polosa, R. (2014). "Safety evaluation and risk assessment of electronic cigarettes as tobacco cigarette substitutes: a systematic review". Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 5 (2): 67–86. doi:10.1177/2042098614524430. ISSN 2042-0986. PMC 4110871. PMID 25083263.

- "The Potential Adverse Health Consequences of Exposure to Electronic Cigarettes and Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems". Oncology Nursing Forum. 42 (5): 445–446. 2015. doi:10.1188/15.ONF.445-446. ISSN 0190-535X. PMID 26302273.

- ^ Durmowicz, E.L. (2014). "The impact of electronic cigarettes on the paediatric population". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii41 – ii46. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051468. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24732163.

- ^ Bertholon, J.F.; Becquemin, M.H.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Dautzenberg, B. (2013). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Short Review". Respiration. 86: 433–8. doi:10.1159/000353253. ISSN 1423-0356. PMID 24080743.

- ^ Polosa, R.; Campagna, D.; Caponnetto, P. (September 2015). "What to advise to respiratory patients intending to use electronic cigarettes". Discovery medicine. 20 (109): 155–61. PMID 26463097.

- Orellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- Kosmider, Leon; et al. (September 2014). "Carbonyl Compounds in Electronic Cigarette Vapors: Effects of Nicotine Solvent and Battery Output Voltage". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 16 (10): 1319–1326. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu078. ISSN 1462-2203. PMID 24832759.

- ^ McNeill, A. (August 2015). "E-cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. pp. 77–78.

- "The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014, Chapter 5 - Nicotine" (PDF). Surgeon General of the United States. 2014. pp. 107–138.