| Revision as of 19:06, 11 February 2008 view sourceDavid Shankbone (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers22,979 edits Revert to revision 190639937 dated 2008-02-11 15:53:48 by Tenmazero using popups← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:13, 11 February 2008 view source 137.244.215.61 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

| == In popular culture == | == In popular culture == | ||

| ]''.<ref>, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2008.</ref>]] | ]''.<ref>, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2008.</ref>]] | ||

| ]'', based on popular depictions of Fawkes.]] | ]'', based on popular depictions of Fawkes.]] | ||

| In 18th-century England, the term "guy" was used to refer to an ] of Fawkes, which would be paraded around town by children on the anniversary of the conspiracy.<ref></ref> It is traditional for children to go door-to-door with their creation asking for a small donation using the term "Penny For The Guy".<ref></ref> In recent years this has attracted controversy as some regard it as nothing more than begging. Whilst it was traditional for children to spend the money raised on fireworks, this is now illegal, as persons under 18 cannot buy fireworks or even be in possession of them in a public place.<ref></ref> | In 18th-century England, the term "guy" was used to refer to an ] of Fawkes, which would be paraded around town by children on the anniversary of the conspiracy.<ref></ref> It is traditional for children to go door-to-door with their creation asking for a small donation using the term "Penny For The Guy".<ref></ref> In recent years this has attracted controversy as some regard it as nothing more than begging. Whilst it was traditional for children to spend the money raised on fireworks, this is now illegal, as persons under 18 cannot buy fireworks or even be in possession of them in a public place.<ref></ref> | ||

Revision as of 19:13, 11 February 2008

For other uses, see Guido Fawkes (disambiguation).| Guy Fawkes | |

|---|---|

A modern illustration of Guy Fawkes with the Houses of Parliament in the background. A modern illustration of Guy Fawkes with the Houses of Parliament in the background. | |

| Status | Ensign |

| Occupation | Soldier |

| Parent(s) | Edward Fawkes, Edith Blake |

| Criminal charge | Conspiracy to assassinate king James I & VI and members of the Houses of Parliament |

| Penalty | Hanged, drawn and quartered |

Guy Fawkes (13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606) sometimes known as Guido Fawkes, was a member of a group of Roman Catholic revolutionaries from England who planned to carry out the Gunpowder Plot. The plot was an attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament, which would have displaced Protestant rule by killing King James I of England and the entire Protestant aristocracy, on 5 November 1605.

Although Robert Catesby was the lead figure in thinking up the actual plot, Fawkes was put in charge of executing the plan due to his military and explosives experience. The plot was foiled shortly before its intended completion, as Fawkes was captured while guarding the gunpowder. Suspicion was aroused by his wearing a coat, boots and spurs, as if he intended to leave very quickly.

Fawkes has left a lasting mark on history and popular culture. Held in the United Kingdom (and some parts of the Commonwealth) on November 5 is Bonfire Night, centred on the plot and Fawkes. He has been mentioned in popular film, literature and music by people such as Charles Dickens and John Lennon. There are geographical locations named after Fawkes, such as Isla Guy Fawkes in the Galápagos Islands and Guy Fawkes River in Australia.

Early life

Childhood

Born on 13 April 1570 at Stonegate in York, Yorkshire, Fawkes was the only son of Edward Fawkes and Edith Blake. His mother had given birth to a daughter a couple of years earlier, named Anne who died seven weeks later on 14 November 1568. Guy was originally baptised in the church of St Michael le Belfrey on 16 April 1570 as a three day old baby. In the five years following Fawkes' birth, his mother also bore two more daughters, Anne (named in honour of the earlier deceased child) and Elizabeth.

He attended St Peter's School in York, where his schoolfellows may have included John and Christopher Wright, both of whom would be among the conspirators of the Gunpowder Plot, and Thomas Morton, who became Bishop of Durham. During Fawkes's time at St Peter's he was under the tutelage of John Pulleyn, kinsman to the Pulleyns of Scotton and a suspected Catholic who, according to some sources, may have had an early effect on the impressionable Fawkes.

Fawkes's father was a descendant of the Fawkes family in Farnley; he was either a notary or proctor of the ecclesiastical courts and later an advocate of the consistory court of the Archbishop of York. Edward's wife, Edith Blake, was descended from prominent merchants and aldermen of the city. Edward Fawkes died in 1579, and his widow remarried in 1582, to a Catholic, Denis Bainbridge of Scotton. The family were known to be recusants, resisters of the authority of the Church of England, and it is probable that his stepfather's influence contributed to Guy’s affiliation to Catholicism; Fawkes finally converted to Catholicism around the age of 16.

Occupation as a soldier

After leaving school, Fawkes became a footman for Anthony Browne, 1st Viscount Montagu. Browne was one of the leading statesmen during the time of Catholic monarch of Scotland Mary and was also allegedly implicated in the Ridolfi plot. Browne took a disliking to Fawkes and fired him after a short time. However, his grandson Anthony-Maria Browne, 2nd Viscount Montagu re-employed Fawkes as a table waiter.

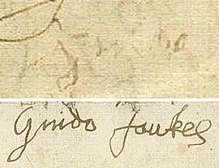

He enlisted in the army of Archduke Albert of Austria in the Netherlands and fought with the armies of Catholic Spain against the Protestant United Provinces in the Dutch Revolt . It was during this time that Fawkes adopted the name Guido, the Spanish form of Guy. He served for many years as a soldier, gaining considerable expertise with explosives, which is the most likely reason that conspirators Winter and Catesby recruited him.

The Netherlands were then possessions of King Philip II of Spain, Duke of Burgundy, and a foreigner to the Dutch. The Dutch associated Spain and Philip's rule with the Catholic Inquisition, which he had tried to impose on his territories in the Low Countries. Fawkes arrived at a time when the death of the Duke of Parma and mutinies by Spanish mercenaries had left the Catholic military force in the Netherlands paralysed, and Maurice of Nassau, the stadtholder in five provinces from 1584 till 1625, son of William of Orange, had led successful campaigns against Spanish positions

In 1596 Fawkes was present at the siege and capture of Calais. By 1602 he had risen only to the rank of ensign. There is some evidence that Fawkes was in considerable poverty around this time. He may have visited Spain in the early 1600s to request Spanish help in returning England to Catholicism.

Gunpowder Plot

Fawkes is notorious for his involvement in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was probably placed in charge of executing the plot because of his military and explosives experience. The plot, masterminded by Robert Catesby, was an attempt by a group of religious conspirators to kill King James I of England, his family, and most of the aristocracy by blowing up the House of Lords in the Palace of Westminster during the State Opening of Parliament. Fawkes may have been introduced to Catesby by Hugh Owen, a man who was in the pay of the Spanish Netherlands. Sir William Stanley is also believed to have recommended him, and Fawkes named him under torture, leading to his arrest and imprisonment for a day after the discovery of the plot. It was Stanley who first presented Fawkes to Thomas Winter in 1603 when Winter was in Europe. Stanley was the commander of the English in Flanders at the time. Stanley had handed Deventer and much of its garrison back to the Spanish in 1587, nearly wiping out the gains that the Earl of Leicester had made in the Low Countries. Leicester’s expedition was widely regarded as a disaster, for this reason among others.

The best primary source for the details of the plot itself is the account known as the King's Book or James I The Kings Book - A True and Perfect Relation of the Whole Proceedings Against the Late Most Barbarous Traitors. Robt. Barker, Printer to the Kings Most Excellent Majesty, British Museum 1606. Although this is a government account, and details have been disputed, it is generally considered to be an accurate record of the history of the plot, and the imprisonment, torture and execution of the plotters. Template:Gunpowder plotters The plot itself may have been occasioned by the realisation by Protestant authorities and Roman Catholic recusants that the Kingdom of Spain was in far too much debt and were fighting too many wars to assist Roman Catholics in the South of Britain. Any possibility of toleration by Great Britain was removed at the Hampton Court conference in 1604 when King James I attacked both extreme Puritans and Catholics. The plotters realised that no outside help would be forthcoming unless they took action themselves. Fawkes and the other conspirators rented a cellar beneath the House of Lords having first tried to dig a tunnel under the building. This would have proved difficult, because they would have had to dispose of the dirt and debris. (No evidence of this tunnel has ever been found). By March 1605, they had hidden 1800 pounds (36 barrels, or 800 kg) of gunpowder in the cellar. The plotters also intended to abduct Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth of Bohemia, the "Winter Queen"). A few of the conspirators were concerned, however, about fellow Catholics who would have been present at Parliament during the opening. One of the conspirators wrote a warning letter to Lord Monteagle, who received it on 26 October. The conspirators became aware of the letter the following day, but they resolved to continue the plot after Fawkes had confirmed that nothing had been touched in the cellar.

Lord Monteagle had been made suspicious, however; the letter was sent to the Secretary of State, who initiated a search of the vaults beneath the House of Lords in the early morning of 5 November. Peter Heywood, a resident of Heywood, Lancashire, was reputedly the man who snatched the torch from Guy Fawkes’s hand as he was about to light the fuse to detonate the gunpowder. Fawkes was tortured over the next few days, after the King granted special permission to do so. James directed that the torture should be gentle at first, and then more severe. Sir William Wade, Lieutenant of the Tower of London at this time, supervised the torture and obtained Fawkes's confession. For three or four days Fawkes said nothing, let alone divulge the names of his co-conspirators. Only when he found out that they had proclaimed themselves by appearing in arms did he succumb. The torture only revealed the names of those conspirators who were already dead or whose names were known to the authorities. Some had fled to Dunchurch, Warwickshire, where they were killed or captured. On 31 January, Fawkes and a number of others implicated in the conspiracy were tried in Westminster Hall. After being found guilty, they were taken to Old Palace Yard in Westminster and St Paul's Yard, where they were hanged, drawn, and quartered. Fawkes, however, managed to avoid the worst of this execution by jumping from the scaffold where he was supposed to be hanged, breaking his neck before he could be drawn and quartered ("The King's Book.",1606.)

Reaction

Many popular contemporary verses were written in condemnation of Fawkes. The most well-known verse begins:

- “Remember, remember the fifth of November,

- The gunpowder, treason and plot,

- I know of no reason

- Why gunpowder treason

- Should ever be forgot.”

(For the full lyrics see Guy Fawkes Night)

John Rhodes produced a popular narrative in verse describing the events of the plot and condemning Fawkes:

- "Fawkes at midnight, and by torchlight there was found

- With long matches and devices, underground"

The full verse was published as A brief Summary of the Treason intended against King & State, when they should have been assembled in Parliament, November 5. 1605. Fit for to instruct the simple and ignorant herein: that they not be seduced any longer by Papists. Other popular verses were of a more religious tone and celebrated the fact that England had been saved from the Guy Fawkes conspiracy. John Wilson published, in 1612, a short song on the "powder plot" with the words:

- "O England praise the name of God

- That kept thee from this heavy rod!

- But though this demon e'er be gone,

- his evil now be ours upon!"

The Lord Mayor and aldermen of the City of London commemorated the conspiracy on November 5 for years after by a sermon in St Paul's Cathedral. Popular accounts of the plot supplemented these sermons, some of which were published and survive to this day. Many in the city left money in their wills to pay for a minister to preach a sermon annually in their own parish.

The Fawkes story continued to be celebrated in poetry. The Latin verse In Quintum Novembris was written c. 1626. John Milton’s Satan in book six of Paradise Lost was inspired by Fawkes — the Devil invents gunpowder to try to match God's thunderbolts. Post-Reformation and anti–Roman Catholic literature often personified Fawkes as the Devil in this way. From Puritan polemics to popular literature, all sought to associate Fawkes with the demoniacal.

In popular culture

In 18th-century England, the term "guy" was used to refer to an effigy of Fawkes, which would be paraded around town by children on the anniversary of the conspiracy. It is traditional for children to go door-to-door with their creation asking for a small donation using the term "Penny For The Guy". In recent years this has attracted controversy as some regard it as nothing more than begging. Whilst it was traditional for children to spend the money raised on fireworks, this is now illegal, as persons under 18 cannot buy fireworks or even be in possession of them in a public place.

A common phrase is that Fawkes was "the only man to ever enter parliament with honourable intentions".This phrase may have originated in a 19th-century pantomime, and was commonly seen on anarchist posters during the early 20th century. The Scottish Socialist Party became embroiled in controversy when they resurrected the poster with humorous intent in 2003.

Fawkes was ranked 30th in the 2002 list of "100 Greatest Britons", sponsored by the BBC and voted for by the public. He was also included in a list of the 50 greatest people from Yorkshire.

In literature

There are several references to Fawkes in popular literature, here are the most noted examples, listed in cronological order.

- 1842: William Harrison Ainsworth - Guy Fawkes: A Historical Romance, is a historical novel which portrayed Fawkes, and Catholic recusancy in general, in a sympathetic light and began to challenge the official depiction of the plot, one of the first to do so.

- 1847: Charlotte Brontë - Jane Eyre, Jane is compared to Guy Fawkes by Abbot with the line "a sort of infantine Guy Fawkes" because she looked like she was constantly plotting schemes. Brontë herself, like Fawkes, was of Yorkshire origins.

- 1850: Charles Dickens - David Copperfield, in order for Peggotty to find money for Saturday's expenses, she "had to prepare a long and elaborate scheme, a very Gunpowder Plot...", directly referencing the Plot Fawkes was involved with.

- 1886: Herman Melville - Billy Budd, the novella mentions Fawkes in the passage "The Pharisee is the Guy Fawkes prowling in the hid chambers underlying the Claggarts".

- 1925: T. S. Eliot - The Hollow Men, the epigraph of the Nobel Prize winning poem directly alludes to Fawkes, "A penny for the Old Guy".

- 1953: Ray Bradbury - Fahrenheit 451, the protagonist of the novel is named Guy Montag directly after Guy Fawkes. In the story, the character plans to start burning down the firemen's houses in order to overthrow the government.

- 1982: Alan Moore - V for Vendetta, the dystopian graphic novel of a fascist Britain takes influence from the story of Fawkes. The story revolves around the main character, V, who wears a stylised Guy Fawkes mask.

- 1998: J. K. Rowling - Chamber of Secrets, the Harry Potter series headmaster Dumbledore's phoenix is named Fawkes after the man.

In film and television

- V for Vendetta was adapted into a film in 2005. The main character "V" wears a mask that is based on popular depiction of Fawkes.

- In the 1985 film The Falcon and the Snowman, which is based on true events, the main character's pet falcon is named after Guy Fawkes.

- In an episode of the Beavis and Butt-head spin-off Daria, Daria is contacted by anthropomorphic personifications of holidays, including Guy Fawkes Night, who is portrayed as a mohawked, leather-jacket-wearing punk reminiscent of Sid Vicious.

- On The Simpsons episode "Simpsoncalifragilisticexpiala(Annoyed Grunt)cious," while flying a kite, Bart remarks that with Shary Bobbins, "every day is Guy Fawkes Day."

- BBC Northern Ireland released the two-part mini-series Gunpowder, Treason & Plot in 2004.

- In the BBC Doctor Who special "The Five Doctors" the Brigadier references their capture from the time scoop as a mix of "Guy Fawkes and Halloween".

In music

- Fawkes is documented in many film newsreels (see the archives of British Pathé and Movietone). The discovery of the plot, the celebration, and Fawkes are mentioned in many popular songs and ballads. Notably, on the vinyl version of The Smiths' album Strangeways, Here We Come, the words "Guy Fawkes was a genius" are carved near the centre of the record.

- On John Lennon's 1970 solo album John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, Lennon sings "Remember, remember, the 5th of November" on the song "Remember". The lyrics are followed by the sound of an explosion.

- The Jethro Tull song "Commons Brawl" includes the lines "But there again I think for less poor Guy went to the wall/The wrong house but the right idea to end the Commons brawl" referring to Fawkes' participation in the Gunpowder Plot.

Other

- Guido Fawkes has been adopted as a pseudonym by the right wing British political blogger, Paul Staines, who deals with political rumor and gossip.

- In the computer game RollerCoaster Tycoon, if one changes a patron's name to 'Guido Fawkes,' a fireworks display appears.

- The Guy Fawkes River and thus Guy Fawkes River National Park in northern New South Wales, Australia were so named by explorer John Oxley when he encountered the river on November 5th, 1824. Fittingly, both men were from North Yorkshire.

- Supporters of United States Presidential Candidate Ron Paul organized an event on Guy Fawkes Day in 2007 that raised a net $4.3 million, the largest documented one-day online fundraising record in political history at that time.

- Project Chanology members often wear a Guy Fawkes mask in their "raids" or demonstrations at Church of Scientology centres. They were first used in raids on Habbo Hotel.

See also

- Bridgwater Guy Fawkes Carnival

- Dunchurch

- Juan de Jáuregui, a Spanish merchant who unsuccessfully tried to assassinate William I of Orange in 1582.

Notes

- James I The Kings Book-A True and Perfect Relation of the Whole Proceedings Against the Late Most Barbarous Traitors. Robt. Barker, Printer to the Kings Most Excellent Majesty, British Museum 1606.

References

- "Transplanted Englishman brings countryís Guy Fawkes party tradition to Burnsville". ThisWeek-Online.com. 24 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Guy Fawkes - Old Peterite". St-Peters.york.sch.uk. 24 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Guy Fawkes: A Biography". Britannia.com. 24 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "A man for all treason". North East History. 24 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Fraser, Antonia. Faith And Treason. Nan A. Talese. ISBN 978-0385471893.

- "Guy Fawkes: From York to the Battlefields of Flanders". Gunpowder-Plot.org. 24 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - L.A. takes part in Scientology protests, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2008.

- Online Etymology Dictionary

- Penny for the Guy Cnn Travel guide

- Firework Laws

- Famous People website: Famous Criminals > Guy Fawkes

- Harrison Ainsworth, William. Guy Fawkes: A Historical Romance. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1428607347.

- "Jane Eyre - by Charlotte Bronte: Chapter III". ReadPrint.com. 25 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0140434941.

- Melville, Herman. Billy Budd. Chelsea House Publications. ISBN 978-0791040546.

- "T. S. Eliot - The Hollow Men". Poetryx.com. 25 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Fahrenheit 451: Summaries and Commentaries - Part One". CliffNotes.com. 25 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Scholastic Online Chat Transcript". Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- "Paul's Money Draws Attention". Guardian Unlimited. 2007-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Phil Shuman (2007-07-26). "FOX 11 Investigates: 'Anonymous'". Fox Interactive Media. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

External links

- An edition of the "King's Book" from 1679

- Guy Fawkes

- A biography on Guy Fawkes from the Gunpowder Plot Society

- Guy Fawkes and Bonfire Night

- Guy Fawkes Day Sayings and Chants, an extensive set of rhymes, often known as Bonfire "prayers" or "chants" which vary by community and location.

- Guy Fawkes and the Theatre

- Site of the Center for Fawkesian Pursuits

- British parliament's Web site to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the plot

- Parliament (Official Site) FAQ on Gunpowder Plot

- Britannia on Fawkes

- York in the time of Guy Fawkes, a walking trail exploring the Gunpowder Plot and its historical context

- Ideas for Catholics to commemorate Guy Fawkes Day — with fireworks

- History, Activities and Greeting Cards for the day

- Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot

| The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 | |

|---|---|

| Original plotters | |

| Recruits | |

| See also | |