| Revision as of 01:40, 11 February 2009 editPietru (talk | contribs)3,694 edits →Religion← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:44, 11 February 2009 edit undo78.149.184.232 (talk) →Historical accountsNext edit → | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

| ===Historical accounts=== | ===Historical accounts=== | ||

| Over time, the various rulers of Malta published their own view of the ethnicity of the population.<ref> Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on the history of the Central Mediterranean | Over time, the various rulers of Malta published their own view of the ethnicity of the population.<ref> Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on the history of the Central Mediterranean | ||

| held at the University of Malta, 13-17 December 1989. Ed: S. Fiorini and V. Mallia-Milanes (Malta University Publications, Malta Historical Society, and Foundation for International Studies, University of Malta) at 33-45. Last visited August 5, 2007.</ref> The ] promoted the idea of a continuous ] presence<ref>. Last visited August 5, 2007.</ref> and during British colonial rule, in an attempt to counteract the growing ] and thus discount a genetic connection between the Maltese and Italian, publications disregarded Sicilian origins for the Maltese.<ref>See, ''e.g.'': . Published 1910. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Nihil Obstat, October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York. Last visited August 6, 2007.</ref> | held at the University of Malta, 13-17 December 1989. Ed: S. Fiorini and V. Mallia-Milanes (Malta University Publications, Malta Historical Society, and Foundation for International Studies, University of Malta) at 33-45. Last visited August 5, 2007.</ref> The ] promoted the idea of a continuous ] presence<ref>. Last visited August 5, 2007.</ref> and during British colonial rule, in an attempt to counteract the growing ] and thus discount a genetic connection between the Maltese and Italian, publications disregarded Sicilian origins for the Maltese.<ref>See, ''e.g.'': . Published 1910. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Nihil Obstat, October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York. Last visited August 6, 2007.</ref> After the Independence of Malta, Libya loaned several millions of dollars to Malta,<ref>, in ''Time Magazine'' (Monday, Jan. 17, 1972). Last viewed August 8, 2007.</ref> and the two countries entered into a ''Friendship and Cooperation Treaty'', and attitudes promoted at the time that the Maltese were linked to the Libyans, not the Italians.<ref>Jeremy Boissevain, "Ritual, Play, and Identity: Changing Patterns of Celebration in Maltese Villages," in ''Journal of Mediterranean Studies'', Vol.1 (1), 1991:87-100 at 88.</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | </blockquote> | ||

| During the ] years following ] of Malta, Libya had loaned several million dollars to Malta to make up for the loss of rental income which followed the closure of British military bases in Malta;<ref>, in ''Time Magazine'' (Monday, Jan. 17, 1972). Last viewed August 8, 2007.</ref> Malta and Libya had entered into a ''Friendship and Cooperation Treaty'', in response to repeated overtures by ] for a closer, more formal union between the two countries; and, for a brief period, Arabic had become a compulsory subject in Maltese secondary schools.<ref>Hanspeter Mattes, "Aspekte der libyschen Außeninvestitionspolitik 1972-1985 (Fallbeispiel Malta)," ''Mitteilungen des Deutschen Orient-Instituts'', No. 26 (Hamburg: 1985), at 88-126; 142-161.</ref> These closer ties with Libya meant a dramatic new (but short-lived) development in Maltese foreign policy: Western media reported that Malta appeared to be turning its back on ], the ], and ] generally.<ref>, in ''Time Magazine'' (Monday, Apr. 09, 1979). Last viewed August 8, 2007.</ref> | |||

| History books were published that began to spread the idea of a disconnection between the Italian and Catholic populations, and instead tried to promote the theory of closer cultural and ethnic ties with North Africa. This new development was noted by Boissevain in 1991: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| ...the Labour government broke off relations with NATO and sought links with the Arab world. After 900 years of being linked to Europe, Malta began to look southward. Muslims, still remembered in folklore for savage pirate attacks, were redefined as blood brothers.<ref>Jeremy Boissevain, "Ritual, Play, and Identity: Changing Patterns of Celebration in Maltese Villages," in ''Journal of Mediterranean Studies'', Vol.1 (1), 1991:87-100 at 88.</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | </blockquote> |

||

| However, following the termination of the Mintoff government and backed by popular sentiment, Malta abandoned its fledgling relationship with North Africa and returned its attention and allegiance to Europe. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 14:44, 11 February 2009

Ethnic group| File:Maltese people.png Rużar Briffa • Maria Adeodata Pisani • Edward de Bono • Gerald Strickland • Dun Karm Psaila • Enrico Mizzi | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

400,000 (2006)

| |

| Languages | |

| Official languages: Maltese, English Significant historical languages: Punic, Greek, Latin, Sicilian, Siculo-Arabic, Italian, French, English | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic |

The Maltese people are a Southern European nation and ethnic group native to Malta, an island nation consisting of an archipelago of seven islands in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea.

Historical background

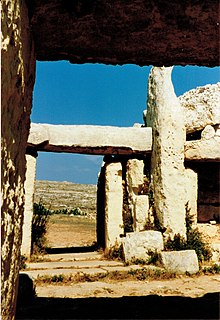

Main article: History of MaltaMalta has been inhabited from around 5200 BC, since the arrival of settlers from the island of Sicily. A significant prehistoric Neolithic culture marked by Megalithic structures, which date back to c. 3600 BC, existed on the islands, as evidenced by the temples of Mnajdra, Ggantija and others. The Phoenicians colonized Malta from about 1000 BC, bringing their Semitic language and culture, using the islands as an outpost from which they expanded sea explorations and trade in the Mediterranean until their successors, the Carthaginians, were ousted by the Romans in 216 BC with the help of the Maltese inhabitants, under whom Malta became a municipium.

After a period of Byzantine rule (4th to 9th century) and a probable sack by the Vandals, the islands were invaded by the Fatimid Arabs in AD 870. The Arabs generally tolerated the population's Christianity and their influence can be seen in the modern Maltese language, a descendant of Siculo-Arabic and the only Semitic language written in the Latin alphabet in its standard form.

The Arabs were expelled from the islands by the Normans in 1090 and their leader Roger I of Sicily was warmly welcomed by the native Christians. Until 1530 the islands were part of the Kingdom of Sicily and briefly controlled by the Capetian House of Anjou. In 1530 Charles I of Spain gave the islands to the Order of Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem in perpetual lease.

The French under Napoleon took hold of the Maltese islands in 1798, although with the aid of the British the Maltese were able to oust French control two years later. The inhabitants subsequently desired Britain to accept the sovereignty of the islands under the conditions laid out in a Declaration of Rights stating that "his Majesty has no right to cede these Islands to any power...if he chooses to withdraw his protection, and abandon his sovereignty, the right of electing another sovereign, or of the governing of these Islands, belongs to us, the inhabitants and aborigines alone, and without control." As part of the Treaty of Paris (1814) Malta became a part of the British Empire, ultimately rejecting an attempted integration with the United Kingdom in 1965.

Malta became independent on September 21, 1964 (Independence Day). Under its 1964 constitution Malta initially retained Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta, with a Governor-General exercising executive authority on her behalf. On December 13, 1974 (Republic Day) it finally became a republic within the Commonwealth, with the President as head of state. Malta joined the European Union on May 1, 2004 and joined the Eurozone on January 1, 2008.

Culture

Main article: Culture of MaltaThe culture of Malta is a reflection of various cultures that have come into contact with the Maltese Islands throughout the centuries, including neighbouring Mediterranean cultures, and the cultures of the nations that ruled Malta for long periods of time prior to its independence in 1964.

The earliest inhabitants of the Maltese Islands are believed to have crossed over from nearby Sicily sometime before 5000 BCE. The culture of modern Malta has been described as a "rich pattern of traditions, beliefs and practices," which is the result of "a long process of adaptation, assimilation and cross fertilization of beliefs and usages drawn from various conflicting sources." It has been subjected to the same complex, historic processes that gave rise to the linguistic and ethnic admixture that defines who the people of Malta and Gozo are today.

Maltese culture has both Semitic and Latin European origins; however, the Latin European element is more readily apparent in modern Malta for two key reasons: the fact that Latin European cultures have had more recent, and virtually continuous impact on Malta over the past eight centuries through political control; and the fact that Malta shares the religious beliefs, traditions and ceremonies of its Sicilian neighbor.

Language

Main article: Maltese languageMaltese people speak the Maltese language, a Semitic language written in the Latin alphabet in its standard form. The language is descended from Siculo-Arabic, a dialect spoken in Sicily and surrounding Southern Italy from the ninth century. In the course of Malta's history, the language has adopted large amounts of vocabulary from Sicilian, Italian, English, and to a smaller degree, French. The official languages of Malta are English and Maltese, with Italian also widely spoken.

Maltese became an official language of Malta in 1934, prior to which the official language was Italian. Today there are an estimated 371,900 Maltese speakers. There are a significant number of Maltese expatriates in Australia, the United States and Canada who still speak the language. Maltese is the only official Semitic language within the European Union.

Multilingualism

Main article: Languages of MaltaBilingualism and even multilingualism is common in Malta. The Eurobarometer statistics show 100% of people speak Maltese, 88% speak English, 66% Italian, 17% French, which shows a greater degree of fluency in a greater amount of languages than many other European countries have.

For 29% of the population, English is the language of the workplace. Studies indicate that somewhere between 86% and 90% of the population speak Maltese within their families, while among friends, that figure drops to about 83.6%. For several decades there has been a growing trend among young Maltese families to speak to their children in English at home. Certain subjects at Secondary level of education are taught in English whereas others are taught in Maltese. However, the situation varies from school to school, to the point that certain schools teach almost exclusively in Maltese while others teach almost exclusively in English. Tertiary education is in English, except for a few subjects.

Religion

Main article: Religion in MaltaThe Constitution of Malta provides for freedom of religion but establishes Roman Catholicism as the state religion.

The Church in Malta is described in the Book of Acts (Acts 27:39–42; Acts 28:1–11) to have been founded by its patrons Saint Paul the Apostle and Saint Publius, who was its first bishop. The Islands of St. Paul (or St. Paul's Islets), are traditionally believed to be the site where Saint Paul was shipwrecked in the year 60 CE, on his way to trial and eventual martyrdom in Rome.

Freedom House and the World Factbook report that 98% of the Maltese religion is Roman Catholic, making the nation one of the most Catholic countries in the world.

Genetic links

The first settlers of Malta were from the island of Sicily. However, the result of the influences on the population after this have been fiercely debated among historians and geneticists. The origins question is complicated by numerous factors, including Malta's turbulent history of invasions and conquests, with long periods of depopulation followed by periods of immigration to Malta and intermarriage with the Maltese by foreigners from the Mediterranean, Western and Southern European countries that ruled Malta.

The many demographic influences on the island include:

- The exile to Malta of the entire male population of the town of Celano (Italy) in 1223

- The stationing of Norman French and Sicilian Italian troops on Malta in 1240

- The removal of all remaining Arabs from Malta in 1224

- The arrival of several hundred Catalan (Spain) soldiers in 1283

- Further waves of European repopulation throughout the 13th century,

- The settlement in Malta of noble families from Sicily (Italy) and Aragon (Spain) between 1372 and 1450

- The arrival of several thousand Greek and Rhodian sailors, soldiers and slaves with the Knights of St. John

- The introduction of several thousand Sicilian laborers in 1551 and again in 1566

- The emigration of some 891 Italian exiles to Malta during the Risorgimento in 1849

- The posting of some 22,000 British servicemen in Malta from 1807 to 1979.

Present view

Confirming the idea that the first settlers on Malta were Sicilian, studies on the Y-chromosomes of men have indicated that the Maltese population has Southern Italian origins, with little genetic input from the Eastern Mediterranean. However, a study carried out by geneticists Spencer Wells and Pierre Zalloua of the American University of Beirut showed that more than 50% of Y-chromosomes from Maltese men could have Phoenecian origins.

Historical accounts

Over time, the various rulers of Malta published their own view of the ethnicity of the population. The Knights of Malta promoted the idea of a continuous Roman Catholic presence and during British colonial rule, in an attempt to counteract the growing Italian power in the area and thus discount a genetic connection between the Maltese and Italian, publications disregarded Sicilian origins for the Maltese. After the Independence of Malta, Libya loaned several millions of dollars to Malta, and the two countries entered into a Friendship and Cooperation Treaty, and attitudes promoted at the time that the Maltese were linked to the Libyans, not the Italians.

See also

|

External links

References

- Australian 2006 Census

- 2002 Community Survey

- Statistics Canada, 2006 Census: Ethnic Origin

- http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/18/23/34792376.xls

- CSO Ireland - 2006 Census

- Ethnologue report for Malta

- ^ "Gozo". IslandofGozo.org. 7 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Castillo, Dennis Angelo. The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313323291. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=i5ns5LNtoiUC&pg=PA25&lpg=PA25&dq=MALTA+sEMPRONIUS&source=web&ots=JHcfabryVa&sig=cXCtKu3apl5Y2y7OEhaMvt1CMM0&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA25,M1.

- Borg, Victor Paul. The Rough Guide to Malta & Gozo. Rough Guides. ISBN 1858286808. http://books.google.com/books?id=o1QO1Tk-FsMC&pg=PA331&dq=byzantine+malta&lr=&as_brr=3&sig=ACfU3U38b0XhbN8wTPyxs2tPEX0RbyVg9w.

- The Official Tourism Site for Malta, Gozo and Comino : What to See & Do : Holiday Ideas : Culture and Heritage : Timeline : :Arab Occupation

- Castillo, Dennis Angelo. The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313323291. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=i5ns5LNtoiUC&pg=PA25&lpg=PA25&dq=MALTA+sEMPRONIUS&source=web&ots=JHcfabryVa&sig=cXCtKu3apl5Y2y7OEhaMvt1CMM0&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA25,M1.

- Holland, James (2003). Fortress Malta: An Island Under Siege, 1940-1943. Miramax Books. ISBN 1-4013-5186-7.

- J. Cassar Pullicino, "Determining the Semitic Element in Maltese Folklore", in Studies in Maltese Folklore, Malta University Press (1992), p. 68.

- MED Magazine

- http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_243_en.pdf

- European Commission, "Malta: Country Profile", Euromosaic Study (September 2004). Available online, at http://ec.europa.eu/

- Kendal, James (1910). "Malta". The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume IX. Retrieved 2006-06-18.

- Debattista, Martin; Timeline of Malta History; retrieved on

- Constantiae Imperatricis et Reginae Siciliae Diplomata: 1195-1198, ed. T.K.Slzer (Vienna, 1983), 237-240.

- Joseph M. Brincat, "Language and Demography in Malta: The Social Foundations of the Symbiosis between Semitic and Romance in Standard Maltese," in Malta: A Case Study in International Cross-Currents. Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on the history of the Central Mediterranean held at the University of Malta, 13-17 December 1989. Ed: S. Fiorini and V. Mallia-Milanes (Malta University Publications, Malta Historical Society, and Foundation for International Studies, University of Malta) at 91-110.] Last visited August 5, 2007.

- C. Capelli, N. Redhead, N. Novelletto, L. Terrenato, P. Malaspina, Z. Poulli, G. Lefranc, A. Megarbane, V. Delague, V. Romano, F. Cali, V.F. Pascali, M. Fellous, A.E. Felice, and D.B. Goldstein; "Population Structure in the Mediterranean Basin: A Y Chromosome Perspective," Annals of Human Genetics, 69, 1-20, 2005. Last visited August 8, 2007.

- In the Wake of the Phoenicians: DNA study reveals a Phoenician-Maltese link

- Anthony Luttrell, "Medieval Malta: the Non-written and the Written Evidence", in Malta: A Case Study in International Cross-Currents. Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on the history of the Central Mediterranean held at the University of Malta, 13-17 December 1989. Ed: S. Fiorini and V. Mallia-Milanes (Malta University Publications, Malta Historical Society, and Foundation for International Studies, University of Malta) at 33-45. Last visited August 5, 2007.

- Anthony T. Luttrell, "Girolamo Manduca and Gian Francesco Abela: Tradition and invention in Maltese Historiography," in Melita Historica, 7 (1977) 2 (105-132). Last visited August 5, 2007.

- See, e.g.: "Malta: Civil History," in The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume IX. Published 1910. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Nihil Obstat, October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York. Last visited August 6, 2007.

- "Gaddafi to the Rescue", in Time Magazine (Monday, Jan. 17, 1972). Last viewed August 8, 2007.

- Jeremy Boissevain, "Ritual, Play, and Identity: Changing Patterns of Celebration in Maltese Villages," in Journal of Mediterranean Studies, Vol.1 (1), 1991:87-100 at 88.