| Revision as of 23:35, 18 October 2005 editSimonP (talk | contribs)Administrators113,129 editsm →Contents← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:31, 13 November 2005 edit undoDbachmann (talk | contribs)227,714 edits fixing ws linkNext edit → | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| {{Wikisourcepar|Bible, Gothic, Ulfila}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 21:31, 13 November 2005

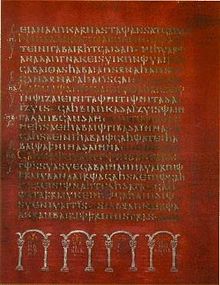

The Codex Argenteus (or "Silver Bible") is a 6th century manuscript, originally containing bishop Ulfilas's 4th century translation of the bible into the Gothic language. Of the original 336 folia, 188 (including the Speyer fragment discovered in 1970) have been preserved, containing the translation of the greater part of the four gospels. A part of it is at permanent display at the Carolina Rediviva library in Uppsala, Sweden.

History

Origin

The tribes we consider Gothic were nominally Arians during the period of time when Ulfilas translated the Christian bible into Gothic, meaning that they followed the teachings of Arius about the person and nature of Jesus Christ. The "Silver Bible" was probably written for the Ostrogothic King Theodoric the Great, either at his royal seat in Ravenna, or in the Po valley or at Brescia. It was made as a special and impressive book written with gold and silver ink on high-quality thin vellum stained a regal purple, with an ornate binding. After Theodoric's death in 526 the Silver Bible is not mentioned in inventories or book lists for a thousand years.

Rediscovery

Parts of the "Codex Argenteus", 187 of the original 336 parchment folia, were preserved at the former Benedictine abbey of Werden, (near Essen, Rhineland) among the richest monasteries of the Holy Roman Empire, whose abbots were imperial princes and had a seat in the imperial diets, where it was rediscovered in the 16th century. The book, or the remaining part of it, came to rest in the library of Emperor Rudolph II at his imperial seat in Prague. At the end of the Thirty Years' War, in 1648, it was taken as war booty to Stockholm, Sweden, to the library of Queen Christina of Sweden. After her conversion to Catholicism and her abdication, the book wound up in the Netherlands. In the 1660s, it was returned to Uppsala University by count Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, who also provided its present lavishly decorated binding. The codex remains to this day at the Uppsala university library Carolina Rediviva.

It is unknown whether the other half of the book survived, and the wanderings of this Codex, the disappearance for a thousand years and possible fragmental remains remain a mystery.

In March 1995, parts of the Codex that were on public display in Carolina Rediviva were stolen. The stolen parts were recovered one month later, in a storage box at the Stockholm Central train station.

The Speyer fragment

The final leaf of the codex, fol. 336, was discovered in October 1970 in Speyer, Germany. It was found at the restoration of the Saint Afra chapel, rolled around a thin wooden staff, contained in a small reliquary originating in Aschaffenburg. The leaf contains the final verses of the Gospel of Mark.

Publications

The first publication mentioning the codex appeared in 1569, by Johannes Goropius Becanus of Antwerp. In 1597, Bonaventura Vulcanius, another Dutchman, published the text, the first publication of a Gothic text altogether, calling the manuscript Codex Argenteus for the first time. In 1737, Lars Roberg, a physician of Uppsala, made a woodcut of one page of the manuscript; it was included in Benzelius' edition of 1750, and the woodcut is preserved in the Linköping Diocesan and Regional Library. Another edition of 1854–7 by Anders Uppström contained an artist's rendition of another page. In 1927, a facsimile edition of the Codex was published.

Script and decoration

The manuscript is written in an uncial script in the alphabet created by Ulfilas for the Gothic language. The script is very uniform, so much so that it has been suggested that it was made with stamps. However, two hands have been identified. One hand in the Gospels of Matthew and John and another in the Gospels of Mark and Luke. The decoration is limited to a few large, framed initials and, at the bottom of each page, a silver arcade which encloses the monograms of the four evangelists.

Contents

- Gospel of Matthew: 5:15-48; 6:1-32; 7:12-29; 8:1-34; 9:1-38; 10:1,23-42; 11:1-25; 26:70-75; 27:1-19,42-66.

- Gospel of John: 5:45-47; 6:1-71; 7:1-53; 8:12-59; 9:1-41; 10:1-42; 11:1-47; 12:1-49; 13:11-38; 14:1-31; 15:1-27; 16:1-33; 27:1-26; 28:1-40; 29:1-13.

- Gospel of Luke 1:1-80; 2:2-52; 3:1-38; 4:1-44; 5:1-39; 6:1-49; 7:1-50; 8:1-56; 9:1-62; 10:1-30; 14:9-35; 15:1-32; 16:1-24; 17:3-37; 18:1-43; 19:1-48; 20:1-47.

- Gospel of Mark: 1:1-45; 2:1-28; 3:1-35; 4:1-41; 5:1-5; 5-43; 6:1-56; 7:1-37; 8:1-38; 9:1-50; 10:1-52; 11:1-33; 12:1-38; 13:16-29; 14:4-72; 15:1-47; 16:1-12 (+ 16:13-20).

See also

Reference

- Bologna, Giulia, Illuminated Manuscripts: The Book before Gutenberg, New York: Crescent Books, 1995. pg. 50.

External links

- The Codex Argenteus Online

- Wulfila Project digital library dedicated to the study of Gothic

- Homepage of the Codex Argenteus (in Swedish)

- Lars Munkhammar, Uppsala University Library, "Codex Argenteus"

- Codex Argenteus Bibliography

- the Gothic Bible on wikisource