| Revision as of 18:35, 15 August 2010 editSardur (talk | contribs)2,308 edits →Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding territories: rebalancing according to the source← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:38, 17 August 2010 edit undoParishan (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users13,427 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| {{cquote|It is clear that Armenians are the target of violence from societal forces and that the Azerbaijani government is unable or in some instances unwilling to control the violence or acts of discrimination and harassment. Some sectors of the government, such as the Department of Visas and Registrations mentioned above, appear unwilling to enforce the governments stated policy on minorities. As long as the Armenian-Azeri conflict over the fate of Karabakh continues, and possibly long after a settlement is reached, Armenian inhabitants of Azerbaijan will have no guarantees of physical safety.}} | {{cquote|It is clear that Armenians are the target of violence from societal forces and that the Azerbaijani government is unable or in some instances unwilling to control the violence or acts of discrimination and harassment. Some sectors of the government, such as the Department of Visas and Registrations mentioned above, appear unwilling to enforce the governments stated policy on minorities. As long as the Armenian-Azeri conflict over the fate of Karabakh continues, and possibly long after a settlement is reached, Armenian inhabitants of Azerbaijan will have no guarantees of physical safety.}} | ||

| ==Armenians in Baku == | |||

| <!-- == Distribution == | |||

| According to 1979 Soviet census in ] lived more than 216 thousand ]. 17.5% (40,400 people)of the total population of the city of ], 57.7% of the city of ], 96% of the town of ]. Almost all the population of ], the significant part of the population of ], 8.7% of the city of ], 7.2% of the city of ] were Armenians. The 63.2% of the population of ] district, 23.9% of population of ] district, and the 18.2% of the population of ] district.<ref></ref>{{Verify credibility|date=March 2010}} --> | |||

| Baku saw a large influx of Armenians following the city's incorporation into the ] in 1806, who worked as merchant, industrial managers and government administrators.<ref>. Europa Publications Limited. ''Azerbaijan''.</ref> Due to favourable economic conditions the Imperial Russian government had provided the Christian population with, Armenians took control of almost one-third of the region's oil industry by 1900.<ref>Richard G. Hovannisian. . Palgrave Macmillan, 2004; p. 125</ref> The growing tension between Armenians and Azeris (often instigated by the Russian officials who feared nationalist movements among their ethnically non-Russian subjects) resulted in ], planting a seed of distrust between these two groups in the city and elsewhere in the region for decades to come.<ref>Suha Bolukbasi. . Willem van Schendel (ed.), Erik Jan Zürcher (ed.). ''Identity politics in Central Asia and the Muslim world''. I.B.Tauris, 2001. "Until the 1905—6 Armeno-Tatar (the Azeris were called Tatars by Russia) war, localism was the main tenet of cultural identity among Azeri intellectuals."</ref><ref>Joseph Russell Rudolph. . ABC-CLIO, 2008. "To these larger moments can be added dozens of lesser ones, such as the 1905-06 Armenian-Tartar wars that gave Azeris and Armenians an opportunity to kill one another in the areas of Armenia and Azerbaijan that were then controlled by Russia..."</ref> Following the proclamation of ], the Armenian nationalist ] Party became increasingly active in then ]-occupied Baku. 70% of the governing body of the ] consisted of ].<ref name="ts">Tadeusz Swietochowski. ''Russian Azerbaijan''. Part III.</ref> Despite pledging non-involvement, the Dashnaks mobilised Armenian militia units to participate in the ] in March 1918, killing thousands.<ref name=" Hopkirk">Peter Hopkirk, "Like hidden fire. The Plot to bring down the British Empire", Kodansha Globe, New York, 1994, p. 287. ISBN 1-56836-127-0</ref> Five months later, the Armenian community itself dwindled as thousands of Armenians either fled Baku or ] at the approach of the Turkish–Azeri army (which seized the city from the Bolsheviks), as an act of retaliation for the Armenian participation in the massacres of local Azeris.<ref name="Croissant-15">Croissant. ''Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict'', p. 15.</ref> Regardless of these events, on 18 December 1918, ethnic Armenians (including members of the Dashnaktsutyun) were represented in the newly-formed Azerbaijani parliament, constituting 11 of its 96 members.<ref name="ts"/> | |||

| ==Armenians in Baku and other areas in the Azerbaijani Republic== | |||

| The anti-Armenian feelings were aroused because of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh resulting in the exodus of most Armenians from Baku and elsewhere in the republic.<ref name="cidcm.umd.edu"/> | |||

| Following the Sovietisation of Azerbaijan, Armenians managed to reestablish a large and vibrant community in Baku comprised of skilled professionals, craftsmen and intelligentsia and integrated into the political, economic and cultural life of Azerbaijan. The community grew steadily in part due to active migration of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians to Baku and other large cities. The mainly-Armenian populated quarter of Baku called Armenikend grew from a tiny village of oil-workers into a prosperous urban community.<ref>Nikolai Baransky. Экономическая география СССР. Учпедгиз, 1938; p. 305</ref> At the advent of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Baku alone had a larger Armenian population than Nagorno-Karabakh.<ref>Anoushiravan Ehteshami. . University of Exeter Press, 1994; p. 164</ref> Armenians were widely represented in the state apparatus.<ref>Encyclopedia Americana. ''Azerbaijan, Republic of''. Grolier Incorporated, 1993</ref> Multiethnic nature of Soviet-era Baku created conditions for active integration of its population and the emergence of a distinct ] urban subculture, to which ethnic identity began losing grounds and with which post-World War II generations of urbanised Bakuvians regardless of their ethnic origin or religious affiliations tended to identify.<ref>Румянцев, Сергей. Об итогах урбанизации в отдельно | |||

| Much of the anti-Armenian sentiments among the Azeri people today stem from ] and the resulting loss of Nagorno-Karabakh territories as well as some other Azerbaijani regions. | |||

| взятой республике на Южном Кавказе.</ref><ref>Мамардашвили, Мераб. </ref> By the 1980s, the Armenian community of Baku had become largely ]. In 1977, 58% of Armenian pupils in Azerbaijan were receiving education in Russian.<ref>Ivan Bilodid. ''Русский язык как средство межнационального общения''. Наука, 1977; p. 164</ref> While in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, Armenians often chose to disassociate themselves from Azerbaijan and Azeris, cases of mixed Azeri-Armenian marriages were quite common in Baku.<ref>Vladimir Shlapentokh. . M.E. Sharpe, 2001; p. 269</ref> The political unrest in Nagorno-Karabakh remained a rather distant concern for Armenians of Baku until March 1988, when the ] took place.<ref>Mark Malkasian. . Wayne State University Press, 1996; p. 176</ref> The anti-Armenian feelings were aroused because of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh resulting in the exodus of most Armenians from Baku and elsewhere in the republic.<ref name="cidcm.umd.edu"/> However, many Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan later reported that despite ethnic tensions taking place in Nagorno-Karabakh, the relationships with their Azeris friends and neighbours had been unaffected.<ref name="miller">Donald Earl Miller, Lorna Touryan Miller, Jerry Berndt. . University of California Press, 2003; p. 38, 56</ref> The Sumgait events became a shock to both Armenian and Azeri population of the cities, and many Armenian lives were saved as ordinary Azeris sheltered them during the pogroms and volunteered to escort them out of the country, often risking their own lives.<ref>Новый мир, Issues 7-9. Известия Совета депутатов Трудящихся СССР, 1998; p. 189</ref><ref>Huberta von Voss. . Berghahn Books, 2007; p. 301</ref> In some cases, the Armenians who were leaving entrusted their houses and possessions to their Azeri friends.<ref name="miller"/> | |||

| ===Pogroms=== | |||

| {{Main|Pogrom of Armenians in Baku}} | {{Main|Pogrom of Armenians in Baku}} | ||

| {{Main|Kirovabad pogrom}} | {{Main|Kirovabad pogrom}} | ||

| {{Main|Sumgait pogrom}} | {{Main|Sumgait pogrom}} | ||

| However, it should also be noted that among the events precipitating the conflict were ]s perpetrated by Azeris against ethnic Armenians in the Azeri towns of ] (1988), ] (]) (1988) and ] (1990)<ref name = "pogroms">{{dead link|date=October 2009|bot=WebCiteBOT}}</ref> and that the Azeris themselves committed atrocities against Armenians during the war, such as the attack on the town of ] (1992).<ref name = "Maraghar">{{dead link|date=October 2009|bot=WebCiteBOT}}, Christianity Today.</ref> | |||

| ===Armenian Churches in Baku=== | ===Armenian Churches in Baku=== | ||

| The Armenian churches in Baku include the Armenian Apostolic ] (''Sourb Grigor Lousavoritch'' in Armenian) and the Old Armenian Church (Baku Fortress). At the height of atrocities against the Armenian minorities in Baku in 1990, the Armenian church in Baku was set on fire, but was restored in 2004 and is not used anymore. | The Armenian churches in Baku include the Armenian Apostolic ] (''Sourb Grigor Lousavoritch'' in Armenian) and the Old Armenian Church (]). At the height of atrocities against the Armenian minorities in Baku in 1990, the Armenian church in Baku was set on fire, but was restored in 2004 and is not used anymore. | ||

| ==Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh |

==Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh == | ||

| {{Main|Nagorno-Karabakh Republic}} | {{Main|Nagorno-Karabakh Republic}} | ||

| {{Main|Artsakh}} | {{Main|Artsakh}} | ||

| Line 46: | Line 41: | ||

| In April 1920, while the Azerbaijani army was locked in Karabakh fighting local Armenian forces, Azerbaijan was taken over by ]s.<ref name="Cornell"/> Subsequently, the disputed areas of Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan came under the control of Armenia. During July and August 1920, however, the ] occupied mountainous Karabakh, Zangezur, and part of Nakhchivan. Later on, for basically political reasons, the Soviet Union agreed to a division under which Zangezur would fall under the control of Armenia, while Karabakh and Nakhchivan would be under the control of Azerbaijan. In addition, the mountainous part of Karabakh that had come to be named ] was granted an autonomous status as the ], giving Armenians more rights than were given to ]<ref name="debiel">Tobias Debiel, Axel Klein, Stiftung Entwicklung und Frieden. . Zed Books, 2002; p.94</ref> and enabling Armenians to be appointed to key positions and attend schools in their first language. | In April 1920, while the Azerbaijani army was locked in Karabakh fighting local Armenian forces, Azerbaijan was taken over by ]s.<ref name="Cornell"/> Subsequently, the disputed areas of Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan came under the control of Armenia. During July and August 1920, however, the ] occupied mountainous Karabakh, Zangezur, and part of Nakhchivan. Later on, for basically political reasons, the Soviet Union agreed to a division under which Zangezur would fall under the control of Armenia, while Karabakh and Nakhchivan would be under the control of Azerbaijan. In addition, the mountainous part of Karabakh that had come to be named ] was granted an autonomous status as the ], giving Armenians more rights than were given to ]<ref name="debiel">Tobias Debiel, Axel Klein, Stiftung Entwicklung und Frieden. . Zed Books, 2002; p.94</ref> and enabling Armenians to be appointed to key positions and attend schools in their first language. | ||

| With the Soviet Union firmly in control of the region, the conflict over the region died down for several decades. The Armenians in Karabakh were not repressed to a substantial extent. Their situation was undoubtedly better than of the Azeris in Armenia who lived in ] in an equally concentrated manner, though without possessing any autonomy.<ref name="debiel"/> Local schools offered education in Armenian but taught Azerbaijani history and not the history of the Armenian people; the population had access to Armenian-language television broadcast by a Stepanakert-based channel controlled from Baku, and later directly from Armenia as well, though |

With the Soviet Union firmly in control of the region, the conflict over the region died down for several decades. The Armenians in Karabakh were not repressed to a substantial extent. Their situation was undoubtedly better than of the Azeris in Armenia who lived in ] in an equally concentrated manner, though without possessing any autonomy.<ref name="debiel"/> Local schools offered education in Armenian but taught Azerbaijani history and not the history of the Armenian people; the population had access to Armenian-language television broadcast by a Stepanakert-based channel controlled from Baku, and later directly from Armenia as well, though in an unfavourable manner.<ref>T.K.Oommen. . Wiley-Blackwell, 1997; p. 131</ref> The autonomy of Nagorno-Karabakh led to the rise of Armenian nationalism and the Armenians' determination in claiming independence. With the beginning of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the question of Nagorno-Karabakh re-emerged. | ||

| Armenians allege that this followed the Azerbaijani and Soviet military forces jointly starting "a campaign of violence to disperse Armenian villagers from areas north and south of Nagorno-Karabakh, a territorial enclave in Azerbaijan where Armenian communities have lived for centuries"<ref name=hrw></ref>. | Armenians allege that this followed the Azerbaijani and Soviet military forces jointly starting "a campaign of violence to disperse Armenian villagers from areas north and south of Nagorno-Karabakh, a territorial enclave in Azerbaijan where Armenian communities have lived for centuries"<ref name=hrw></ref>. | ||

Revision as of 04:38, 17 August 2010

Armenians in Azerbaijan are the Armenians who lived in great numbers in Azerbaijan (120,700 as of 1999 Azerbaijani official statistics). According to the statistics, about 400,000 Armenians lived in Azerbaijan in 1989. Most of the Armenian-Azerbaijanis however had to flee the republic, like Azeris in Armenia, in the events leading up to the Nagorno-Karabakh War, a result of the ongoing Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. Atrocities directed against the Armenian population have reportedly taken place in Sumgait (February 1988), Ganja (Kirovabad, November 1988) and Baku (January 1990). Today the vast majority of Armenians in Azerbaijan live in territory controlled by the break-away region Nagorno-Karabakh, which declared its unilateral act of independence in 1991 under the name Nagorno-Karabakh Republic but has not been recognised by any country, including Armenia.

In 1998, non-official sources estimated the number of Armenians living on Azerbaijani territory outside Nagorno-Karabakh at around 30,000 or less, and almost exclusively comprises persons married to Azeris or of mixed Armenian-Azeri descent.

In Azerbaijan, the status of Armenians, is precarious.. Armenian churches remain closed, because of the large outmigration of Armenians and fear of Azeri attacks.

The Armenians still remaining in Azerbaijan have continued to complain (in private due to fear of attacks) that they remain subject to harassmant and human rights violations and therefore have to hide their identity..

According to a 1993 Immigration and naturalization service report:

It is clear that Armenians are the target of violence from societal forces and that the Azerbaijani government is unable or in some instances unwilling to control the violence or acts of discrimination and harassment. Some sectors of the government, such as the Department of Visas and Registrations mentioned above, appear unwilling to enforce the governments stated policy on minorities. As long as the Armenian-Azeri conflict over the fate of Karabakh continues, and possibly long after a settlement is reached, Armenian inhabitants of Azerbaijan will have no guarantees of physical safety.

Armenians in Baku

Baku saw a large influx of Armenians following the city's incorporation into the Russian Empire in 1806, who worked as merchant, industrial managers and government administrators. Due to favourable economic conditions the Imperial Russian government had provided the Christian population with, Armenians took control of almost one-third of the region's oil industry by 1900. The growing tension between Armenians and Azeris (often instigated by the Russian officials who feared nationalist movements among their ethnically non-Russian subjects) resulted in mutual pogroms in 1905–1906, planting a seed of distrust between these two groups in the city and elsewhere in the region for decades to come. Following the proclamation of Azerbaijan's independence in 1918, the Armenian nationalist Dashnaktsutyun Party became increasingly active in then Bolshevik-occupied Baku. 70% of the governing body of the Baku Commune consisted of ethnic Armenians. Despite pledging non-involvement, the Dashnaks mobilised Armenian militia units to participate in the massacres of Baku's Muslim population in March 1918, killing thousands. Five months later, the Armenian community itself dwindled as thousands of Armenians either fled Baku or were massacred at the approach of the Turkish–Azeri army (which seized the city from the Bolsheviks), as an act of retaliation for the Armenian participation in the massacres of local Azeris. Regardless of these events, on 18 December 1918, ethnic Armenians (including members of the Dashnaktsutyun) were represented in the newly-formed Azerbaijani parliament, constituting 11 of its 96 members.

Following the Sovietisation of Azerbaijan, Armenians managed to reestablish a large and vibrant community in Baku comprised of skilled professionals, craftsmen and intelligentsia and integrated into the political, economic and cultural life of Azerbaijan. The community grew steadily in part due to active migration of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians to Baku and other large cities. The mainly-Armenian populated quarter of Baku called Armenikend grew from a tiny village of oil-workers into a prosperous urban community. At the advent of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Baku alone had a larger Armenian population than Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenians were widely represented in the state apparatus. Multiethnic nature of Soviet-era Baku created conditions for active integration of its population and the emergence of a distinct Russian-speaking urban subculture, to which ethnic identity began losing grounds and with which post-World War II generations of urbanised Bakuvians regardless of their ethnic origin or religious affiliations tended to identify. By the 1980s, the Armenian community of Baku had become largely Russified. In 1977, 58% of Armenian pupils in Azerbaijan were receiving education in Russian. While in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, Armenians often chose to disassociate themselves from Azerbaijan and Azeris, cases of mixed Azeri-Armenian marriages were quite common in Baku. The political unrest in Nagorno-Karabakh remained a rather distant concern for Armenians of Baku until March 1988, when the Sumgait pogrom took place. The anti-Armenian feelings were aroused because of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh resulting in the exodus of most Armenians from Baku and elsewhere in the republic. However, many Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan later reported that despite ethnic tensions taking place in Nagorno-Karabakh, the relationships with their Azeris friends and neighbours had been unaffected. The Sumgait events became a shock to both Armenian and Azeri population of the cities, and many Armenian lives were saved as ordinary Azeris sheltered them during the pogroms and volunteered to escort them out of the country, often risking their own lives. In some cases, the Armenians who were leaving entrusted their houses and possessions to their Azeri friends.

Main article: Pogrom of Armenians in Baku Main article: Kirovabad pogrom Main article: Sumgait pogromArmenian Churches in Baku

The Armenian churches in Baku include the Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory Illuminator (Sourb Grigor Lousavoritch in Armenian) and the Old Armenian Church (Baku Fortress). At the height of atrocities against the Armenian minorities in Baku in 1990, the Armenian church in Baku was set on fire, but was restored in 2004 and is not used anymore.

Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

Main article: Nagorno-Karabakh Republic Main article: Artsakh Main article: Nagorno-Karabakh

Armenians have lived in the Karabakh region since Roman times. In the beginning of the 2 century B.C. Karabakh became a part of Armenian Kingdom as province of Artsakh. In the 14th century, a local Armenian leadership emerged, consisting of five noble dynasties led by princes, who held the titles of meliks and were referred to as Khamsa (five in Arabic). The Armenian meliks maintained control over the region until the 18th century. In the early 16th century, control of the region passed to the Safavid dynasty, which created the Ganja-Karabakh province (beglarbekdom, bəylərbəyliyi). Despite these conquests, the population of Upper Karabakh remained largely Armenian..

Karabakh passed to Imperial Russia by the Kurekchay Treaty, signed between the Khan of Karabakh and Tsar Alexander I of Russia in 1805, and later further formalized by the Russo-Persian Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, before the rest of Transcaucasia was incorporated into the Empire in 1828 by the Treaty of Turkmenchay. In 1822, the Karabakh khanate was dissolved, and the area became part of the Elisabethpol Governorate within the Russian Empire.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Karabakh became part of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, but this soon dissolved into separate Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian states. Over the next two years (1918–1920), there were a series of short wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan over several regions, including Karabakh. In July 1918, the First Armenian Assembly of Nagorno-Karabakh declared the region self-governing and created a National Council and government. Later, Ottoman troops entered Karabakh, meeting armed resistance by Armenians.

In April 1920, while the Azerbaijani army was locked in Karabakh fighting local Armenian forces, Azerbaijan was taken over by Bolsheviks. Subsequently, the disputed areas of Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhchivan came under the control of Armenia. During July and August 1920, however, the Red Army occupied mountainous Karabakh, Zangezur, and part of Nakhchivan. Later on, for basically political reasons, the Soviet Union agreed to a division under which Zangezur would fall under the control of Armenia, while Karabakh and Nakhchivan would be under the control of Azerbaijan. In addition, the mountainous part of Karabakh that had come to be named Nagorno-Karabakh was granted an autonomous status as the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, giving Armenians more rights than were given to Azeris in Armenia and enabling Armenians to be appointed to key positions and attend schools in their first language.

With the Soviet Union firmly in control of the region, the conflict over the region died down for several decades. The Armenians in Karabakh were not repressed to a substantial extent. Their situation was undoubtedly better than of the Azeris in Armenia who lived in Zangezur in an equally concentrated manner, though without possessing any autonomy. Local schools offered education in Armenian but taught Azerbaijani history and not the history of the Armenian people; the population had access to Armenian-language television broadcast by a Stepanakert-based channel controlled from Baku, and later directly from Armenia as well, though in an unfavourable manner. The autonomy of Nagorno-Karabakh led to the rise of Armenian nationalism and the Armenians' determination in claiming independence. With the beginning of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the question of Nagorno-Karabakh re-emerged.

Armenians allege that this followed the Azerbaijani and Soviet military forces jointly starting "a campaign of violence to disperse Armenian villagers from areas north and south of Nagorno-Karabakh, a territorial enclave in Azerbaijan where Armenian communities have lived for centuries".

"However, the unstated goal was to "convince" the villagers half are pensioners to relocate permanently in Armenia." This military action was officially called "Operation Ring," because its basic strategy consists of surrounding villages (included Martunashen and Chaykand) with tanks and armored personnel carriers and shelling them. Azerbaijani villagers were allowed to come and loot the empty Armenian villages, while more than ten thousand Armenian villagers have been forced to leave Azerbaijan.

The majority Armenian population started a movement that culminated in the unilateral declaration of independence.

Armenians in Nakhchivan

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Armenians had a historic presence in Nakhchivan (In Armenian Նախիջևան). According to an Armenian tradition, Nakhchivan was founded by Noah, of the Abrahamic religions. It became part of the Satrapy of Armenia under Achaemenid Persia circa 521 BC. In 189 BC, Nakhchivan was part of the new Kingdom of Armenia established by Artaxias I. In 428, the Armenian Arshakuni monarchy was abolished and Nakhchivan was annexed by Sassanid Persia. In 623 AD, possession of the region passed to the Byzantine Empire. Nakhchivan itself became part of the autonomous Principality of Armenia under Arab control. After the fall of the Arab rule in the 9th century, the area became the domain of several Muslim emirates of Arran and Azerbaijan. Nakhchivan became part of the Seljuk Empire in the 11th century, followed by becoming the capital of the Atabegs of Azerbaijan in the 12th century. In the 1220s it was plundered by Khwarezmians and Mongols. In the 15th century, the weakening Mongol rule in Nakhchivan was forced out by the Turcoman dynasties of Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu.

In the 16th century, control of Nakhchivan passed to the Safavid dynasty of Persia. In 1604, Shah Abbas I Safavi, concerned that the lands of Nakhchevan and the surrounding areas would pass into Ottoman hands, decided to institute a scorched earth policy. He forced the entire local population, Armenians, Jews and Muslims alike, to leave their homes and move to the Persian provinces south of the Aras River. Many of the deportees were settled in the neighborhood of Isfahan that was named New Julfa since most of the residents were from the original Julfa (a predominantly Armenian town).

After the last Russo-Persian War and the Treaty of Turkmenchay, the Nakhchivan khanate passed into Russian possession in 1828. The Nakhchivan khanate was dissolved, and its territory was merged with the territory of the Erivan khanate and the area became the Nakhchivan uyezd of the new Armenian Oblast, which was reformed into the Erivan Governorate in 1849. A resettlement policy implemented by the Russian authorities encouraged massive Armenian immigration to Nakhchivan from various parts of the Ottoman Empire and Persia. According to official statistics of the Russian Empire, by the turn of the 20th century Azerbaijanis made up 57% of the uyezd's population, while Armenians constituted 42%.

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, conflict erupted between the Armenians and the Azeris, culminating in the Armenian-Tatar massacres. In the final year of World War I, Nakhchivan was the scene of more bloodshed between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, who both laid claim to the area. By 1914, the Armenian population was at 40% while the Azeri population increased to roughly 60%. After the February Revolution, the region was under the authority of the Special Transcaucasian Committee of the Russian Provisional Government and subsequently of the short-lived Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. When the TDFR was dissolved in May 1918, Nakhchivan, Nagorno-Karabakh, Zangezur (today the Armenian province of Syunik), and Qazakh were heavily contested between the newly formed and short-lived states of the Democratic Republic of Armenia (DRA) and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR). In June 1918, the region came under Ottoman occupation. Under the terms of the Armistice of Mudros, the Ottomans agreed to pull their troops out of the Transcaucasus to make way for the forthcoming British military presence.

After a brief British occupation and the fragile peace they tried to impose, in December 1918, with the support of Azerbaijan's Musavat Party, Jafar Gulu Khan Nakhchivanski declared the Republic of Aras in the Nakhchivan uyezd of the former Erivan Governorate assigned to Armenia by Wardrop. The Armenian government did not recognize the new state and sent its troops into the region to take control of it. The conflict soon erupted into the violent Aras War. By mid-June 1919, however, Armenia succeeded in establishing control over Nakhchivan and the whole territory of the self-proclaimed republic. The fall of the Aras republic triggered an invasion by the regular Azerbaijani army and by the end of July, Armenian troops were forced to leave Nakhchivan City to the Azeris. In mid-March 1920, Armenian forces launched an offensive on all of the disputed territories, and by the end of the month both the Nakhchivan and Zangezur regions came under stable but temporary Armenian control. In July 1920, the 11th Soviet Red Army invaded and occupied the region and on July 28, declared the Nakhchivan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic with "close ties" to the Azerbaijan SSR. A referendum was called for the people of Nakhchivan to be consulted. According to the formal figures of this referendum, held at the beginning of 1921, 90% of Nakhchivan's population wanted to be included in the Azerbaijan SSR "with the rights of an autonomous republic. The decision to make Nakhchivan a part of modern-day Azerbaijan was cemented March 16, 1921 in the Treaty of Moscow between Bolshevist Russia and Turkey. The agreement between the Soviet Russia and Turkey also called for attachment of the former Sharur-Daralagez uyezd (which had a solid Azeri majority) to Nakhchivan, thus allowing Turkey to share a border with the Azerbaijan SSR. This deal was reaffirmed on October 23, in the Treaty of Kars.

During the Soviet era, Nakhchivan saw a significant demographic shift. Its Armenian population gradually decreased as many emigrated to the Armenian SSR. In 1926, 11% of region's population was Armenian, but by 1979 this number had shrunk to 1.4%. The Azeri population, meanwhile increased substantially with both a higher birth rate and immigration (going from 85% in 1926 to 96% by 1979). The Armenian population saw a great reduction in their numbers throughout the years repatriating to Armenia.

Some Armenian political groupings of the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian diaspora, amongst them most notably the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) claim that Nakhchivan should belong to Armenia. However, Nakhchivan is not officially claimed by the government of Armenia. But huge Armenian religious and cultural remnants are witness of the historic presence of Armenians in the Nakhcivan region (Nakichevan, sometimes Nakhijevan in Armenian). Recently the Medieval Armenian cemetery of Jugha (Julfa) in Nakhchevan, regarded by Armenians as the biggest and most precious repository of medieval headstones marked with Christian crosses – khachkars (of which more than 2,000 were still there in the late 1980s), has completely vanished in 2006.

Famous Armenians from Azerbaijan

- Hovhannes Bagramyan Army Commander, Marshal of the Soviet Union

- Hovannes Adamian, designer of color television

- Alexander Shirvanzade, playwright and novelist, awarded by the "People's Writer of Armenia" and "People's Writer of Azerbaijan" titles

- Boris Babaian, pioneering creator of supercomputers in the Soviet Union

- Armen Ohanian, an Armenian dancer, actress, writer and translator

- Alexey Ekimyan, composer and police general

- Garri Kasparov, grandmaster and world champion

- Vladimir Akopian, chess player

- Ashot Nadanian, chess player

- Vladimir Bagirov, chess player

- Yevgeny Petrosyan, comedian

- Georgy Shakhnazarov, political scientist

- Rafael Kapreliants, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Avet Terterian, composer

- Sergey Petrosyan, weightlifter

- Karina Aznavourian, épée fencer

See also

- List of Azerbaijani Armenians

- Armenian–Azerbaijani War

- Kirovabad pogrom

- Pogrom of Armenians in Baku

- Sumgait pogrom

- Armenian National Council of Baku

References

- Demographic indicators: Population by ethnic groups

- Memorandum from the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights to John D. Evans, Resource Information Center, 13 June 1993.

- "Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Human Rights and Democratization in the Newly Independent States of the former Soviet Union" (Washington, DC: U.S. Congress, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, January 1993), p. 118.

- ^ Assessment for Armenians in Azerbaijan, Minorities At Risk Project

- Razmik Panossian. The Armenians. Columbia University Press, 2006; p. 281

- Mario Apostolov. The Christian-Muslim Frontier. Routledge, 2004; p. 67

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. 2001

- Barbara Larkin. International Religious Freedom (2000): Report to Congress by the Department of State. DIANE Publishing, 2001; p. 256

- Assessment for Armenians in Azerbaijan. N.B.: Armenians living in Azerbaijan outside the Nagorno-Karabakh region are almost exclusively members of mixed families.

- Azerbaijan: The status of Armenians, Russians, Jews and other minorities, report, 1993, INS Resource Information Center, p. 10

- United States Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1992 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, February 1993), p. 708

- "Implementation of the Helsinki Accords: Human Rights and Democratization in the Newly Independent States of the former Soviet Union" (Washington, DC: U.S. Congress, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, January 1993), p. 118

- "AZERBAIJAN: THE STATUS OF ARMENIANS, RUSSIANS, JEWS AND OTHER MINORITIES", INS resource information center, 1993

- Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2004. Europa Publications Limited. Azerbaijan.

- Richard G. Hovannisian. The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004; p. 125

- Suha Bolukbasi. Nation-building in Azerbaijan. Willem van Schendel (ed.), Erik Jan Zürcher (ed.). Identity politics in Central Asia and the Muslim world. I.B.Tauris, 2001. "Until the 1905—6 Armeno-Tatar (the Azeris were called Tatars by Russia) war, localism was the main tenet of cultural identity among Azeri intellectuals."

- Joseph Russell Rudolph. Hot spot: North America and Europe. ABC-CLIO, 2008. "To these larger moments can be added dozens of lesser ones, such as the 1905-06 Armenian-Tartar wars that gave Azeris and Armenians an opportunity to kill one another in the areas of Armenia and Azerbaijan that were then controlled by Russia..."

- ^ Tadeusz Swietochowski. Russian Azerbaijan. Part III.

- Peter Hopkirk, "Like hidden fire. The Plot to bring down the British Empire", Kodansha Globe, New York, 1994, p. 287. ISBN 1-56836-127-0

- Croissant. Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict, p. 15.

- Nikolai Baransky. Экономическая география СССР. Учпедгиз, 1938; p. 305

- Anoushiravan Ehteshami. From the Gulf to Central Asia. University of Exeter Press, 1994; p. 164

- Encyclopedia Americana. Azerbaijan, Republic of. Grolier Incorporated, 1993

- Румянцев, Сергей. Столица, город или деревня. Об итогах урбанизации в отдельно взятой республике на Южном Кавказе.

- Мамардашвили, Мераб. «Солнечное сплетение» Евразии.

- Ivan Bilodid. Русский язык как средство межнационального общения. Наука, 1977; p. 164

- Vladimir Shlapentokh. . M.E. Sharpe, 2001; p. 269

- Mark Malkasian. . Wayne State University Press, 1996; p. 176

- ^ Donald Earl Miller, Lorna Touryan Miller, Jerry Berndt. Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope. University of California Press, 2003; p. 38, 56

- Новый мир, Issues 7-9. Известия Совета депутатов Трудящихся СССР, 1998; p. 189

- Huberta von Voss. Portraits of hope: Armenians in the Contemporary World. Berghahn Books, 2007; p. 301

- ^ Cornell, Svante E. The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. Uppsala: Department of East European Studies, April 1999.

- The Nagorno-Karabagh Crisis: A Blueprint for Resolution, New England Center for International Law & Policy

- ^ Tobias Debiel, Axel Klein, Stiftung Entwicklung und Frieden. . Zed Books, 2002; p.94

- T.K.Oommen. Citizenship, nationality, and ethnicity. Wiley-Blackwell, 1997; p. 131

- ^ HRW Report on Soviet Union Human Rights Developments, 1992

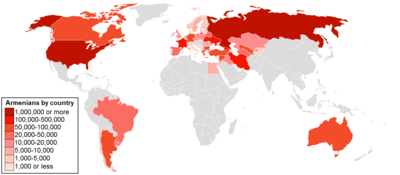

| Armenian diaspora | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Historic areas of Armenian settlement | ||

| Caucasus | ||

| Former Soviet Union | ||

| Americas | ||

| Europe | ||

| Middle East | ||

| Asia | ||

| Africa | ||

| Oceania | ||