| Revision as of 04:08, 8 February 2006 view sourceChristopher Parham (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,662 edits Revert to revision 38718687 using popups← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:30, 8 February 2006 view source 139.168.25.110 (talk) →Use of the word "football" in English-speaking countriesNext edit → | ||

| Line 181: | Line 181: | ||

| The word "''football''", when used in reference to a specific game can mean any one of those described above. Because of this, much friendly controversy has occurred over the term ''football'', primarily because it is used in different ways in different parts of the ]. | The word "''football''", when used in reference to a specific game can mean any one of those described above. Because of this, much friendly controversy has occurred over the term ''football'', primarily because it is used in different ways in different parts of the ]. | ||

| In most English-speaking countries, the word "football" usually refers to ], also known as soccer (soccer originally being a slang abbreviation of ''Association''). Of the 48 national ] affiliates in which ] is an official or primary language, only |

In most English-speaking countries, the word "football" usually refers to ], also known as soccer (soccer originally being a slang abbreviation of ''Association''). Of the 48 national ] affiliates in which ] is an official or primary language, only six — ], the ], ], ], ] and the ] — use soccer in their name, while the rest use football. However, even in the countries where football is the official name of association football, this name may be at odds with common usage. | ||

| In other countries or regions within them, the word "football" may refer to ], ], ], ], or one of the two codes of ]: ] or ]. | In other countries or regions within them, the word "football" may refer to ], ], ], ], or one of the two codes of ]: ] or ]. | ||

Revision as of 06:30, 8 February 2006

- This article deals with the history and development of the different sports around the world known as "football". For links to articles on each of these codes of football, please see the list in the Football today section of this article.

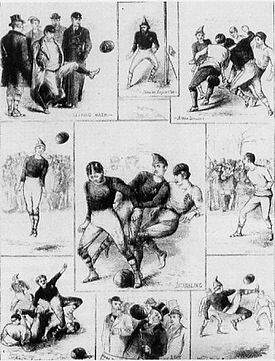

Football is the name given to a number of different, but related, team sports. The most popular of these worldwide is Association football, which is called soccer in several countries. The English language word football is also applied to Rugby football (Rugby union and Rugby league), American football, Australian rules football, Gaelic football, and Canadian football. (See also: Players who have converted from one football code to another.)

While it is widely believed that the word football, or "foot ball", originated in reference to the action of a foot kicking a ball, there is a rival explanation, which has it that football originally referred to a variety of games in medieval Europe, which were played on foot. These games were usually played by peasants, as opposed to the horse-riding sports often played by aristocrats. While there is no conclusive evidence for this explanation, the word football has always implied a variety of games played on foot, not just those that involved kicking a ball. In some cases, the word football has been applied to games which have specifically outlawed kicking the ball. (See football (word) for more details.)

All football games involve scoring points with a spherical or ellipsoidal ball (itself called a football), by moving the ball into, onto, or over a goal area or line defended by the opposing team. Many of the modern games have their origins in England, but many peoples around the world have played games which involved kicking and/or carrying a ball since ancient times.

The object of all football games is to advance the ball by kicking, running with, or passing and catching, either to the opponent's end of the field where points or goals can be scored by, depending on the game, putting the ball across the goal line between posts and under a crossbar, putting the ball between upright posts (and possibly over a crossbar), or advancing the ball across the opponent's goal line while maintaining possession of the ball.

In all football games, the winning team is the one that has the most points or goals when a specified length of time has elapsed.

History

Throughout the history of mankind the urge to kick at stones and other such objects is thought to have led to many early activities involving kicking and/or running with a ball. Football-like games predate recorded history in all parts of the world, though the earliest forms of football are not known.

Ancient games

Documented evidence of what is possibly the oldest organized activity resembling football can be found in a Chinese military manual written during the Han Dynasty in about 2nd century BC.

It describes a practice known as tsu chu (Traditional Chinese:蹴鞠 or 蹴踘 ; Pinyin: cù jū) which involved kicking a leather ball through a hole in a piece of silk cloth strung between two 30 foot poles. It was not a game as such but more of a spectacle for the amusement of the Emperor and it may have been performed as long as 3000 years ago.

Another Asian ball-kicking game, which may have been influenced by tsu chu, is kemari. This is known to have been played within the Japanese imperial court in Kyoto from about 600AD. In kemari several individuals stand in a circle and kick a ball to each other, trying not to let the ball drop to the ground (much like keepie uppie). The game survived through many years but appears to have died out sometime before the mid 19th century. In 1903 in a bid to restore ancient traditions the game was revived and it can now be seen played for the benefit of tourists at a number of festivals.

The Greeks and Romans are known to have played many ball games some of which involved the use of the feet. The Roman writer Cicero describes the case of a man who was killed whilst having a shave when a ball was kicked into a barbers shop. The Roman game of Harpastu is believed to have been adapted from a team game known as "επισκυρος" (episkyros) or pheninda that is mentioned by Greek playwright, Antiphanes (388-311BC) and later referred to by Clement of Alexandria. The game appears to have vaguely resembled rugby.

There are a number of less well-documented references to prehistoric, ancient or traditional ball games, played by indigenous peoples all around the world. For example, William Strachey of the Jamestown settlement is the first to record a game played by the Native Americans called Pahsaheman, in 1610. In Victoria, Australia, Indigenous Australians played a game called Marn Grook. An 1878 book by Robert Brough-Smyth, The Aborigines of Victoria, quotes a man called Richard Thomas as saying, in about 1841, that he had witnessed Aboriginal people playing the game: "Mr Thomas describes how the foremost player will drop kick a ball made from the skin of a possum and how other players leap into the air in order to catch it." It is widely believed that Marn Grook had an influence on the development of Australian Rules Football (see below). In northern Canada and/or Alaska, the Inuit (Eskimos) played a game on ice called Aqsaqtuk. Each match began with two teams facing each other in parallel lines, before attempting to kick the ball through each other team's line and then at a goal. The ancient Aztec game of ollamalitzli also involved kicking a ball, but it generally had more similarities to basketball.

These games and others may well stretch far back into antiquity and have influenced football over the centuries. However, the route towards the development of modern football games appears to lie in Western Europe and particularly England.

Mediæval football

Further information: Mediæval footballThe Middle Ages saw a huge rise in popularity of annual Shrovetide football matches throughout Europe, particularly in England. The game played in England at this time may have arrived with the Roman occupation, but there is little evidence to indicate this. Reports of a game played in Brittany, Normandy and Picardy, known as Choule or Soule, suggest that some of these football games could have arrived in England as a result of the Norman Conquest.

These archaic forms of football would be played between neighbouring towns and villages, involving an unlimited number of players on opposing teams, who would clash in a heaving mass of people struggling to drag an inflated pig's bladder by any means possible to markers at each end of a town. A legend that these games in England evolved from a more ancient and bloody ritual of kicking the "Dane's head" is unlikely to be true. Shrovetide games survive in a number of English towns (see below).

The first description of football in England was given by William FitzStephen (c. 1174-1183). He described the activities of London youths during the annual festival of Shrove Tuesday.

- After lunch all the youth of the city go out into the fields to take part in a ball game. The students of each school have their own ball; the workers from each city craft are also carrying their balls. Older citizens, fathers, and wealthy citizens come on horseback to watch their juniors competing, and to relive their own youth vicariously: you can see their inner passions aroused as they watch the action and get caught up in the fun being had by the carefree adolescents.

Most of the early references to the game speak simply of "ball play" or "playing at ball". This reinforces the idea that the games played at the time did not necessarily involve a ball being kicked. The first clear reference to football was not recorded until 1409, when King Henry IV of England issued an edict to ban it. In 1424, King James I of Scotland also attempted to ban the playing of "fute-ball". However, the first clear reference to a ball being used did not occur until 1486.

The first reference to football in Ireland occurs in the Statute of Galway of 1527, which allowed the playing of football and archery but banned "hokie' — the hurling of a little ball with sticks or staves" as well as other sports. (The earliest recorded football match in Ireland was one between Louth and Meath, at Slane, in 1712.)

Calcio Fiorentino

Main article: Calcio FiorentinoIn the 16th century, the city of Florence celebrated the period between Epiphany and Lent by playing a game known as "o Calcio storico" ("kickball in costume") in the Piazza della Novere or the Piazza Santa Croce. The young aristocrats of the city would dress up in fine silk costumes and embroil themselves in a violent form of football. For example, calcio players could punch, shoulder charge, and kick opponents. Blows below the belt were allowed. The game is said to have originated as a military training exercise. The most famous match took place on February 17, 1530. While the troops of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor were besieging Florence, a game of calcio was organised as a show of defiance. In 1580, Count Giovanni de' Bardi di Vernio wrote Discorso sopra 'l giuoco del Calcio Fiorentino. This is sometimes credited as the earliest known published rules of any football game. The game was not played between January 1739 and May 1930, when it was revived to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the match mentioned above. Calcio is still played, mostly as a tourist attraction.

Official disapproval and attempts to ban football

Numerous attempts have been made throughout history to ban football games, particularly the most rowdy and disruptive forms. Between 1324 and 1667, football was banned in England alone by more than 30 royal and local laws. King Edward II was so troubled by the unruliness of football in London that on April 13, 1314 he issued a proclamation banning it:

- Forasmuch as there is great noise in the city caused by hustling over large balls from which many evils may arise which God forbid; we command and forbid, on behalf of the King, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future.

The reasons for the ban by Edward III, on June 12, 1349, were explicit: football and other recreations distracted the populace from practicing archery, which was necessary for war, and after the great loss of life that had occurred during the Black Death, England needed as many archers as possible.

Football featured in similar attempts by monarchs to ban recreational sport across Europe. In France it was banned by Phillippe V in 1319, and again by Charles V in 1369. In England, the outlawing of sport was attempted by Richard II in 1389 and Henry IV in 1401. In Scotland, football was banned by James I in 1424 and by James II in 1457. Despite evidence that Henry VIII of England played the game — in 1526, he ordered the first known pair of football boots — in 1540 Henry also attempted a ban. All of these attempts failed to curb the people's desire to play the game.

By 1608, the local authorities in Manchester were complaining that:

- With the ffotebale... hath beene greate disorder in our towne of Manchester we are told, and glasse windowes broken yearlye and spoyled by a companie of lewd and disordered persons using that unlawful exercise of playing with the ffotebale in ye streets of the said towne, breaking many men's windows and glasse at their pleasure and other great inormyties.

That same year, the modern spelling of the word "football" is first recorded, when it was used disapprovingly by William Shakespeare. Shakespeare's play King Lear (which was first published in 1608) contains the line: "Nor tripped neither, you base football player" (Act I Scene 4). Shakespeare also mentions the game in A Comedy of Errors (Act II Scene 1):

- Am I so round with you as you with me,

- That like a football you do spurn me thus?

- You spurn me hence, and he will spurn me hither:

- If I last in this service, you must case me in leather.

("Spurn" literally means to kick away, thus implying that the game involved kicking a ball between players.)

In the period following the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell had some success in suppressing football games, although they became even more popular following the Restoration, in 1660. Charles II of England gave the game royal approval in 1681 when he attended a fixture between the Royal Household and the Duke of Albemarle's servants.

Even in the early modern era, efforts were made to ban football at a local level, and force it off the streets. In 1827, the annual Alnwick Shrove Tuesday game proceeded only after the Duke of Northumberland provided a field for the game to be played on. (The Duke also presented the ball before the match — a ritual that continues to this day.) In 1835, the British Highways Act banned the playing of football on public highways, with a maximum penalty of forty shillings.

The establishment of modern codes of football

English public schools

The earliest evidence that games resembling football were being played at English public schools — attended by boys from the upper, upper-middle and professional classes — comes from the Vulgaria by William Horman in 1519. Horman had been headmaster at Eton College and Winchester and his Latin textbook includes a translation exercise with the phrase "We wyll playe with a ball full of wynde". The first specific mention of football can be found in a Latin poem by Robert Matthew, a Winchester scholar from 1643 to 1647. He describes how "...we may play quoits, or hand-ball, or bat-and-ball, or football; these games are innocent and lawful...". Nugae Etonenses (1766) by T. Frankland also mentions the "Football Fields" at Eton.

By the early 19th century, (before the Factory Act of 1850), most working class people in Britain had to work six days a week, often for over twelve hours a day. They had neither the time nor the inclination to engage in sport for recreation and, at the time, many children were part of the labour force. Feast day football on the public highway was at an end. Thus the public school boys, who were free from constant toil, became the inventors of organised football games with formal codes of rules. These gradually evolved into the modern football games that we know today.

Football had come to be adopted by a number of public schools as a way of encouraging competitiveness and keeping youths fit. Each school drafted their own rules as they saw fit and they often varied widely and were changed over time with each new intake of pupils. In 1823 William Webb Ellis, a pupil at Rugby School, is said to have "showed a fine disregard for the rules of football, as played in his time" by picking up the ball and running to the opponents' goal, but the evidence for this bold act does not stand up to close examination. However, by 1841 (some sources say 1842), running with the ball had become acceptable at Rugby, as long as a player gathered the ball on the full or from a bounce, he was not offside and he did not pass the ball.

Soon, two schools of thought about how football should be played had developed. Some favoured a game in which the ball could be carried (as at Rugby, Marlborough and Cheltenham), whilst others preferred a game where kicking and dribbling the ball was promoted (as at Eton, Harrow, Westminster and Charterhouse). The division into these two camps was partly the result of circumstances in which the games were played. At Charterhouse and Westminster the boys were confined to playing their ball game within the cloisters making the rough and tumble of the handling game difficult.

During this period, the Rugby School rules appear to have spread at least as far, perhaps further, than the other schools' games. For example, it is said that the world's first "football club" (that is one which was not part of a school or university), was the Guy's Hospital Football Club, founded in London in 1843. The club is said to have played the Rugby School game. However, some have argued that this club is too poorly documented to be considered to have existed since that time.

In 1845, three boys at Rugby School were tasked with codifying the rules then being used at the school. These were the first set of written rules (or code) for any form of football. This further assisted the spread of the Rugby game.

The boom in rail transport in Britain during the 1840s meant that people were able to travel further and with less inconvenience than they ever had before. Inter-school sporting competitions became possible. While local rules for athletics could be easily understood by visiting schools, it was nearly impossible for schools to play each other at football, as each school played by its own rules.

The Cambridge Rules

Main article: The Cambridge RulesIn 1848 at Cambridge University, Mr. H. de Winton and Mr. J.C. Thring, who were both formerly at Shrewsbury School, called a meeting at Trinity College, Cambridge with 12 other representatives from Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Winchester and Shrewsbury. An eight-hour meeting produced what amounted to the first set of modern rules, known as the Cambridge Rules. No copy of these rules now exists, but a revised version from circa 1856 is held in the library of Shrewsbury School. The rules clearly favour the kicking game. Handling was only allowed for a player to take a clean catch entitling them to a free kick and there was a primitive offside rule, disallowing players from "loitering" around the opponents' goal. However, the Cambridge Rules were not widely adopted.

Other developments in the 1850s

The increasing interest and development of the various English football games was shown in 1851, when William Gilbert, a shoemaker from Rugby, exhibited both round and oval-shaped balls at the Great Exhibition in London.

Dublin University Football Club — founded at Trinity College, Dublin in 1854 and later famous as a bastion of the Rugby School game — is arguably the world's oldest football club in any code.

Sheffield Football Club also has a claim to be the world's oldest football club, in the sense of a club not attached to a school or university. It was founded by former Harrow School pupils Nathaniel Creswick and William Prest, in 1857. Creswick and Prest devised their own version of football: the Sheffield Rules. There were some similarities to the Cambridge Rules, but players were allowed to push or hit the ball with their hands, and there was no offside rule at all, so that players known as 'kick throughs' could be permanently positioned near the opponents' goal. (How long this set of rules lasted is unclear, but by 1866, when Sheffield played a combined FA side, they were employing their own version of offside that differed from the FA rule. In 1867 the Sheffield Football Association was formed by a number of clubs in the local area and the Sheffield clubs continued to play by their own rules until they decided to fall in line with the FA in 1878.)

By the end of the 1850s, many clubs had been formed throughout the English-speaking world, to play various codes of football. (For more details see: Oldest football clubs.)

Australian Rules football

Main article: Australian Rules footballTom Wills began to develop Australian Rules football in Melbourne during 1858. Wills had been educated in England, at Rugby School and had played cricket for Cambridge University. The extent to which Wills was directly influenced by British and Irish football games is unknown, but there were similarities between some of them and his game. There were pronounced similarities between Wills's game and Gaelic football (as it would be codified in 1887). It appears that Australian Rules also has some similarities to the Indigenous Australian game of Marn Grook (see above).

The Melbourne Football Club was also founded in 1858 and is the oldest surviving Australian football club, but the rules it used during its first season are unknown. The club's rules of 1859 are the oldest surviving set of laws for Australian Rules. They were drawn up at the Parade Hotel, East Melbourne on May 17, by Wills, W. J. Hammersley, J. B. Thompson and Thomas Smith (some sources include H. C. A. Harrison). These men had similar backgrounds to Wills and their code also had pronounced similarities to the Sheffield rules, most notably in the absence of an offside rule. A free kick was awarded for a mark (clean catch). However, running while holding the ball was allowed and although it was not specified in the rules, an oval ball (like those later used in rugby) was used. The club had a strong and long-standing association with the Melbourne Cricket Club and cricket ovals — which vary in size and are much larger than the fields used in other forms of football — became the standard playing field. The 1859 rules did not include some elements which would soon become important to the game, such as the requirement to bounce the ball while running.

Australian Rules is sometimes said to be the first form of football to be codified but — as was the case in all kinds of football at the time, there was no official body supporting the rules — and play varied from one club to another. By 1866, however, several other clubs in the Colony of Victoria had agreed to play an updated version of the Melbourne FC rules, which were later known as "Victorian Rules" and/or "Australasian Rules". The official name of the code is now Australian football.

The Football Association

In 1862, J. C. Thring, who had been one of the driving forces behind the original Cambridge Rules, was now a master at Uppingham School and he issued his own rules of what he called "The Simplest Game" (these are also known as the Uppingham Rules). In early October of 1863 a new revised set of Cambridge Rules rules were drawn up by a seven man committee representing former pupils from Harrow, Shrewsbury, Eton, Rugby, Marlborough and Westminster. This later revised version of the Cambridge Rules rules were to form the basis of what eventually became the rules adopted by The Football Association (FA).

On the evening of October 26, 1863 at the Freemason's Tavern in Great Queen Street, London, The Football Association (FA) met for the first time. It was the world's first official football body. The meeting had been called, not by public school figures, but by members of several football clubs in the London Metropolitan area. Charterhouse was the only school represented at that first meeting. The aim was to produce a single code of football that everybody could agree to and to set up a governing body for the regulation of the game. The first meeting resulted in the issuing of a request for representatives of the public schools to join the association. With the exception of Thring at Uppingham, most schools declined. Rugby, Eton and Winchester did not even reply. In total, six meetings were held between October and December 1863. At the close of the third meeting, a draft set of rules were published that most of the delegates were happy to endorse, but this agreement was not to last. At the beginning of the fourth meeting, attention was drawn to the fact that a number of newspapers had recently published the Cambridge Rules of 1863. The Cambridge rules differed from the draft FA rules in two significant areas; namely 'running with the ball' and 'hacking' (kicking an opponent in the shins). The two contentious draft rules were as follows:

- IX.A player shall be entitled to run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal if he makes a fair catch, or catches the ball on the first bound; but in case of a fair catch, if he makes his mark he shall not run.

- X.If any player shall run with the ball towards his adversaries' goal, any player on the opposite side shall be at liberty to charge, hold, trip or hack him, or to wrest the ball from him, but no player shall be held and hacked at the same time.

At the fifth meeting a motion was proposed that these two rules be expunged from the FA rules. Most of the delegates were favourable to this suggestion but F. W. Campbell, the representative from Blackheath and the first FA treasurer, objected strongly. He said, "hacking is the true football". The motion was carried nonetheless but at the final meeting, Campbell withdrew his club from the FA. After the final meeting on 8 December the FA published the "Laws of Football", the first comprehensive set of rules for the game later known as Association football (or, colloquially, soccer). These first FA rules still contained elements that are recognisable in other games for instance, a player could make a fair catch and claim a mark and if a player touched the ball behind the opponents' goal line, his side was entitled to a free kick at the goal 15 yards from the goal line.

Rugby football

- See the earlier section English public schools and the main article history of rugby union

In Britain, by 1870, there were about 75 clubs playing variations of the Rugby School game, including Blackheath (founded in 1858 and arguably the world's oldest surviving, non-university rugby club). There were also "rugby" clubs in Ireland, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. However, there was no generally accepted set of rules for rugby until 1871, when 21 clubs in England came together to form the Rugby Football Union (RFU). (Ironically, Blackheath now lobbied to ban hacking.) The first official RFU rules were adopted in June 1871.

North American football

Main article: ]As was the case in Britain, by the early 19th century, North American schools and universities played their own local games, between sides made up of students. By the 1820s, a game known as Ballown was being played at the College of New Jersey (later known as Princeton University) and Old Division Football was being played at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire. In 1827, a Harvard University student composed a humorous epic poem called The Battle of the Delta, one of the first accounts of football in American universities.

The first documented football match in Canada was a game played at University College, University of Toronto on November 9, 1861. A football club was formed at the university soon afterwards, although its rules of play at this stage are unclear: it is not known whether they played a kicking or handling game, or both, and its members mostly played against each other.

The first "football club" in the USA was the short-lived Oneida Football Club in Boston, Massachusetts, founded in 1862. It has often been said that this club was the first to play soccer outside Britain. However, the rules that the Oneida club used are also unknown, and it was formed before the FA rules were formulated. The club may have invented the "Boston Game", a running code which was being played several years later in Massachusetts.

In 1864, at Trinity College, Toronto, F. Barlow Cumberland and Frederick A. Bethune devised rules based on the Rugby School game. However, the first game of "rugby" in Canada is generally said to have taken place in Montreal, in 1865, when British Army officers played local civilians. The game gradually gained a following, and the Montreal Football Club was formed in 1868, the first recorded football club in Canada.

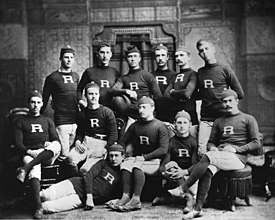

The first match generally said to have occurred under English FA (soccer) rules in the USA was a game between Princeton and Rutgers in 1869. This is also often considered to be the first US game of college football, in the sense of a game between colleges (although the eventual form of American football would come from rugby, not soccer).

Modern American football grew out of a match between McGill University of Montreal, and Harvard University in 1874. At the time, Harvard students are reported to have played the "Boston Game" — a running code — rather than the FA-based kicking games favored by US universities. This made it easy for Harvard to adapt to the rugby-based game played by McGill and the two teams alternated between their respective sets of rules. Within a few years, however, Harvard had both adopted McGill's rugby rules and had persuaded other US university teams to do the same. In 1876, at the Massasoit Convention, it was agreed by these universities to adopt most of the Rugby Football Union rules. However, a touch-down (as it was also known in rugby football at the time) only counted toward the score if neither side kicked a field goal. The convention decided that, in the US game, four touchdowns would be worth one goal; in the event of a tied score, a goal converted from a touchdown would take precedence over four touch-downs.

Princeton, Rutgers and others continued to compete using soccer-based rules for a few years before switching to the rugby-based rules of Harvard and its competitors. US colleges did not generally return to soccer until the early twentieth century.

In 1880, Yale coach Walter Camp, devised a number of major changes to the American game, beginning with the reduction of teams from 15 to 11 players, followed by reduction of the field area by almost half, and; the introduction of the scrimmage, in which a player heeled the ball backwards, to begin a game. These were complemented in 1882 by another of Camp's innovations: a team had to surrender possession if they did not gain five yards after three downs (i.e. successful tackles).

Over the years Canadian football absorbed some developments in American football, but also retained many unique characteristics. One of these was that Canadian football, for many years, did not officially distinguish itself from rugby. For example, the Canadian Rugby Football Union, founded in 1884 was the forerunner of the Canadian Football League, rather than a Rugby Union body. (The Canadian Rugby Union was not formed until 1965.) American football was also frequently described as "rugby" in the 1880s.

Gaelic football

Main article: History of Gaelic football. In the mid-19th century, various traditional football games, referred to collectively as caid, remained popular in Ireland, especially in County Kerry. One observer, Father W. Ferris, described two main forms of caid during this period: the "field game" in which the object was to put the ball through arch-like goals, formed from the boughs of two trees, and; the epic "cross-country game" which took up most of the daylight hours of a Sunday on which it was played, and was won by one team taking the ball across a parish boundary. "Wrestling", "holding" opposing players, and carrying the ball were all allowed.

By the 1870s, Rugby and Association football had started to become popular in Ireland. Trinity College, Dublin was an early stronghold of Rugby (see the Developments in the 1850s section, above). The rules of the English FA were being distributed widely. Caid had begun to give way to a "rough-and-tumble game" which even allowed tripping.

There was no serious attempt to unify and codify Irish varieties of football, until the establishment of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) in 1884. The GAA sought to promote traditional Irish sports, such as hurling and to reject "foreign" (particularly English) imports. The first Gaelic football rules were drawn up by Maurice Davan and published in the United Ireland magazine on February 7, 1887. Davan's rules showed the influence of games such as hurling and a desire to formalise an Irish code of football distinct from Rugby and Association football. The prime example of this differentiation was the lack of an offside rule (an attribute which, for many years, was shared only by other Irish games like hurling, and by Australian rules football).

The split in rugby football

Further information: History of rugby leagueThe International Rugby Football Board (IRFB) was founded in 1886, but rifts were beginning to emerge in the code. Professionalism was beginning to creep into the various codes of football. In Britain, by the 1890s, a long-standing Rugby Football Union ban on professional players was causing regional tensions within rugby football, as many players in northern England were working class and could not afford to take time off to train, travel, play and recover from injuries. In 1895 representatives of the northern clubs met in Huddersfield to form the Northern Rugby Football Union (NRFU), a professional competition.

Within a few years the NRFU rules had started to diverge from the RFU, most notably with the abolition of the line out. The separate Lancashire and Yorkshire competitions of the NRFU merged in 1901, forming the Northern Rugby League, the first time the name Rugby League was used officially. Eventually, to differentiate the two codes of rugby, the code played by clubs which remained members of national federations affiliated to the IRFB became known as Rugby Union.

The reform of American football

Both forms of rugby and American football were noted at the time for serious injuries, as well as the deaths of a significant number of players. By the early 20th century in the USA, this had resulted in national controversy and American football was banned by a number of colleges. Consequently, a series of meetings was held by 19 colleges in 1905-06. This occurred reputedly at the behest of President Theodore Roosevelt, who was considered to be a fancier of the game, but who had threatened to ban it, unless the rules were modified to reduce the numbers of deaths and disabilities. The meetings are now considered to be the origin of the National Collegiate Athletic Association.

One proposed change was a widening of the playing field. However, Harvard University had just built a concrete stadium, objected and proposed instead legalisation of the forward pass. The report of the meetings introduced many restrictions on tackling and two more divergences from rugby: the banning of mass formation plays, as well as the forward pass. The changes did not immediately have the desired effect, and 33 American football players were killed during 1908 alone. However, the number of deaths and injuries did gradually decline.

The two rugby codes diverge further

Rugby league rules diverged significantly from rugby union in 1906, with the reduction of the team from 15 to 13 players, and the introduction of the play the ball (heeling the ball back after a tackle). In 1907, a New Zealand professional rugby team toured Australia and Britain, and as a result the New South Wales Rugby League was formed. However the rules of professional rugby varied from one country to another, and negotiations between various national bodies were required to fix the exact rules for each international match. This situation endured until 1948, when at the instigation of the French league, the Rugby League International Federation (RLIF) was formed at a meeting in Bordeaux.

Football today

Use of the word "football" in English-speaking countries

Further information: Football (word)The word "football", when used in reference to a specific game can mean any one of those described above. Because of this, much friendly controversy has occurred over the term football, primarily because it is used in different ways in different parts of the English-speaking world.

In most English-speaking countries, the word "football" usually refers to Association football, also known as soccer (soccer originally being a slang abbreviation of Association). Of the 48 national FIFA affiliates in which English is an official or primary language, only six — Canada, the Marshall Islands, New Zealand, Samoa, Australia and the United States — use soccer in their name, while the rest use football. However, even in the countries where football is the official name of association football, this name may be at odds with common usage.

In other countries or regions within them, the word "football" may refer to American football, Australian rules football, Canadian football, Gaelic football, or one of the two codes of rugby football: rugby league or rugby union.

The different codes are listed below and are described more fully in their own articles.

Games descended from the FA rules of 1863

- Association football, also known as soccer.

- Indoor varieties of Association football:

- Five-a-side football - played throughout the world under various rules including:

- Indoor soccer — the six-a-side indoor game as played in North America

- Paralympic Football — modified association football for disabled competitors.

- Beach soccer — football played on sand, also known as sand soccer

Games descended from Rugby School rules

- Rugby football

- Rugby League

- Touch football — usually known simply as "Touch".

- OzTag — a form of Rugby League replacing tackles with tags.

- Rugby Union

- Touch Rugby — a form of rugby union without tackles.

- Tag Rugby — a form of Touch Rugby, in which a velcro tag is taken to indicate a tackle.

- Wheelchair Rugby

- Rugby League

- American football — called "football" in the United States, and "gridiron" in Australia and New Zealand.

- Arena football — an indoor version of American football

- Touch football — non-tackle American football.

- Flag football — non-tackle American football, like touch football, in which a flag that is held by velcro on a belt tied around the waist is pulled by defenders to indicate a tackle.

- Canadian football — called simply "football" in Canada.

- Canadian flag football — non-tackle Canadian football.

- Speedball (American) — a combination of American football, soccer, and basketball, devised by Elmer D. Mitchell at the University of Michigan in 1912. There is an coincidental resemblance to Gaelic football. It has since been played occasionally on an experimental basis, but is not known to have had organised competitions amateur leagues. (Another game known as speedball is a combination of soccer and handball.)

Irish and Australian varieties of football

- Australian rules football — now known officially as Australian football and informally as "Aussie rules" or "footy". Often (erroneously) referred to as "AFL", which is the name of the main organising body.

- Auskick — a version of Australian rules designed by the AFL for young children

- Metro Footy (or Metro rules footy) — a modified version invented by the USAFL, for use on gridiron fields in North American cities (which often lack grounds large enough for conventional Australian rules matches).

- 9-a-side Footy — a more open, running variety of Australian rules, requiring 18 players in total and a proportionally smaller playing area. (Includes contact and non-contact varieties.)

- Rec Footy — "Recreational Football", a modified non-contact touch variation of Australian rules, created by the AFL, which replaces tackles with tags.

- Samoa Rules — localised version adapted to Samoan conditions, such as the use of rugby fields.

- Austus – a compromise between Australian rules and American football, invented in Melbourne during World War II.

- Gaelic football

- International rules football — a compromise code used for games between Gaelic and Australian Rules players.

- Marn Grook — a game played by some Australian Aboriginal communities, which is considered to have partly inspired Australian football.

Surviving Mediæval ball games

- Traditional Shrove Tuesday matches in the UK — annual town- or village-wide football games with their own rules. Alternative names include mob football, Shrovetide football and folk football.

- Alnwick in Northumberland

- Ashbourne in Derbyshire (known as Royal Shrovetide Football)

- Atherstone in Warwickshire

- Corfe Castle in Dorset The Shrove Tuesday Football Ceremony of the Purbeck Marblers

- Haxey in Lincolnshire (the Haxey Hood, actually played on Epiphany)

- Hurling the Silver Ball takes place at St Columb Major in Cornwall

- Sedgefield in County Durham

- In Scotland the Ba game ("Ball Game") is still popular around Christmas and Hogmanay at:

- Duns, Berwickshire

- Scone, Perthshire

- Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands

- Outside the UK other Mediæval games include:

- Calcio Fiorentino — a modern revival of Renaissance football from 16th century Florence.

For details of extinct varieties of football invented and/or played during the Middle Ages in Europe, see the medieval football article.

Other surviving public school games

More recent inventions and derivations

- Based on Medieval football:

- Based on FA rules:

- Based on Rugby:

- Force em' Backs

Tabletop games and other recreations

- Based on FA rules:

- Category:Football (soccer) computer and video games

- Subbuteo

- Blow football

- Foosball (also known as table football/soccer, babyfoot, bar football or gettone)

- Fantasy football (soccer)

- Button football (also known as Futebol de Mesa; Jogo de Botões)

- Based on Rugby:

- Based on American Football:

References

- Mandelbaum, Michael (2004); The Meaning of Sports; Public Affairs, ISBN 1586482521

- Green, Geoffrey (1953); The History of the Football Association; Naldrett Press, London

- Williams, Graham (1994); The Code War; Yore Publications, ISBN 1874427658

External links

- RFU Museum of Rugby: Chronology

- FIFA history page

- Association of Football Statisticians History of football pages