| Revision as of 13:16, 6 October 2011 editJaan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users17,257 edits See WP:OPENPARA.← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:32, 6 October 2011 edit undoJaan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users17,257 edits Sorry, apparently he was a Soviet citizen until 1982.Next edit → | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev''' ({{lang-ba|Рудольф Хәмит улы Нуриев}}, {{lang-tt|Rudolf Xämit ulı Nuriev}}, {{lang-ru|Рудо́льф Хаме́тович Нуре́ев}}) (17 March 1938 – 6 January 1993) was a ] ] |

'''Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev''' ({{lang-ba|Рудольф Хәмит улы Нуриев}}, {{lang-tt|Rudolf Xämit ulı Nuriev}}, {{lang-ru|Рудо́льф Хаме́тович Нуре́ев}}) (17 March 1938 – 6 January 1993) was a ] ], considered one of the most celebrated ] dancers of the 20th century. Nureyev's artistic skills explored expressive areas of the dance, providing a new role to the male ballet dancer who once served only as support to the women. | ||

| In 1961 he defected to the West, despite ] efforts to stop him.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/3667963/The-KGBs-long-war-against-Rudolf-Nureyev.html|title=The KGB's long war against Rudolf Nureyev|publisher=The Telegraph | location=London | first=John | last=Bridcut | date=17 September 2007 | accessdate=22 May 2010}}</ref> According to ] archives studied by Peter Watson, ] personally signed an order to have Nureyev killed.<ref name="rivera">{{cite book|title=My sax life|author=Paquito D'Rivera, Ilan Stavans|isbn=0810122189}}</ref> | In 1961 he defected to the West, despite ] efforts to stop him.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/3667963/The-KGBs-long-war-against-Rudolf-Nureyev.html|title=The KGB's long war against Rudolf Nureyev|publisher=The Telegraph | location=London | first=John | last=Bridcut | date=17 September 2007 | accessdate=22 May 2010}}</ref> According to ] archives studied by Peter Watson, ] personally signed an order to have Nureyev killed.<ref name="rivera">{{cite book|title=My sax life|author=Paquito D'Rivera, Ilan Stavans|isbn=0810122189}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:32, 6 October 2011

This article is about the ballet dancer. For the Thoroughbred racehorse, see Nureyev (horse).| This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (August 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Rudolf Nureyev" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Rudolf Nureyev | |

|---|---|

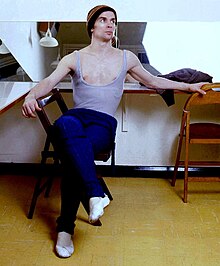

Rudolf Nureyev in 1973 by Allan Warren Rudolf Nureyev in 1973 by Allan Warren | |

| Born | Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev (1938-03-17)17 March 1938 near Irkutsk, Siberia, USSR |

| Died | 6 January 1993(1993-01-06) (aged 54) Levallois-Perret, France |

| Cause of death | AIDS |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Kirov Ballet School |

| Occupation(s) | ballet dancer, choreographer |

| Years active | 1958–1992 |

| Partner | Erik Bruhn (1961–1986) |

| Website | www.nureyev.org |

Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev (Template:Lang-ba, Template:Lang-tt, Template:Lang-ru) (17 March 1938 – 6 January 1993) was a Russian dancer, considered one of the most celebrated ballet dancers of the 20th century. Nureyev's artistic skills explored expressive areas of the dance, providing a new role to the male ballet dancer who once served only as support to the women.

In 1961 he defected to the West, despite KGB efforts to stop him. According to KGB archives studied by Peter Watson, Nikita Khrushchev personally signed an order to have Nureyev killed.

Early life and career at the Kirov

Nureyev was born on a Trans-Siberian train near Irkutsk, Siberia, Soviet Union, while his mother Feride was travelling to Vladivostok, where his father Hamit, a Red Army political commissar, was stationed. He was raised as the only son in a Bashkir-Tatar family in a village near Ufa in Soviet republic of Bashkortostan. When his mother took him and his sisters into a performance of the ballet "Song of the Cranes", he fell in love with dance. As a child he was encouraged to dance in Bashkir folk performances and his precocity was soon noticed by teachers who encouraged him to train in Leningrad. On a tour stop in Moscow with a local ballet company, Nureyev auditioned for the Bolshoi ballet company and was accepted. However, he felt that the Kirov Ballet school was the best, so he left the local touring company and bought a ticket to Leningrad.

Owing to the disruption of Soviet cultural life caused by World War II, Nureyev was unable to enroll in a major ballet school until 1955, aged 17, when he was accepted by the Leningrad Choreographic School, the associate school of the Kirov Ballet.

Alexander Ivanovich Pushkin took an interest in him professionally and allowed Nureyev to live with him and his wife. Upon graduation, Nureyev continued with the Kirov and went on to become a soloist.

In his three years with the Kirov, he danced fifteen rôles, usually opposite his partner, Ninel Kurgapkina, with whom he was very well paired, although she was almost a decade older than he was. He became one of the Soviet Union's best-known dancers and was allowed to travel outside the Soviet Union, when he danced in Vienna at the International Youth Festival. Not long after, for disciplinary reasons, he was told he would not be allowed to go abroad again. He was confined to tours of the Soviet republics.

Defection

By the late 1950s, Nureyev had become a sensation in the Soviet Union. Yet, as the Kirov ballet was preparing to go on a European tour, Nureyev's rebellious character and a non-conformist attitude quickly made him the unlikely candidate for a trip to the West, which was to be of crucial importance to the Soviet government's ambitions to portray their cultural supremacy. However, in 1961, the Kirov's leading male dancer, Konstantin Sergeyev, was injured, and Nureyev was chosen to replace him on the Kirov's European tour. In Paris, his performances electrified audiences and critics, but he broke the rules about mingling with foreigners, which alarmed the Kirov's management. The KGB wanted to send him back to the Soviet Union immediately. As a subterfuge, they told him that he would not travel with the company to London to continue the tour because he was needed to dance at a special performance in the Kremlin. When that didn't work they told him his mother had fallen severely ill and he needed to come home immediately to see her. He knew these were lies and believed that if he returned to the U.S.S.R., he would likely be imprisoned, because KGB agents had been investigating him.

On June 16, 1961 at the Le Bourget Airport in Paris, Rudolf Nureyev defected with the help of French police and a Parisian socialite friend - Clara Saint. Within a week, he was signed up by the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas and was performing The Sleeping Beauty with Nina Vyroubova. On a tour of Denmark he met Erik Bruhn, soloist dancer at the Royal Danish Ballet who became his lover, his closest friend and his protector until Bruhn's death in 1986.

Although he petitioned the Soviet government for many years to be allowed to visit his mother, he was not allowed to do so until 1987, when his mother was dying and Mikhail Gorbachev consented to the visit. In 1989, he was invited to dance with the Kirov Ballet at the Maryinsky theatre in Leningrad. The visit gave him the opportunity to see many of the teachers and colleagues he had not seen since he defected, including his first ballet teacher in Ufa.

Royal Ballet

Nureyev's first appearance in Britain was at a ballet matinée organised by The Royal Ballet's Prima Ballerina Dame Margot Fonteyn. The event was held in aid of the Royal Academy of Dance, a classical ballet teaching organisation of which she was President. He danced "Poeme Tragique", a solo choreographed by Frederick Ashton, and the Black Swan pas de deux from Swan Lake.

Dame Ninette de Valois offered him a contract to join The Royal Ballet as Principal Dancer. His first appearance with the company was partnering Margot Fonteyn in Giselle on 21 February 1962. Fonteyn and Nureyev would go on to form a partnership. Nureyev stayed with the Royal Ballet until 1970, when he was promoted to Principal Guest Artist, enabling him to concentrate on his increasing schedule of international guest appearances and tours. He continued to perform regularly with The Royal Ballet until committing his future to the Paris Opera Ballet in the 1980s.

Nureyev and his dance partnerships

Rudolph Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn became longstanding dance partners and continued to dance together for many years after Nureyev's departure from the Royal Ballet. Their last performance together was in Baroque Pas de Trois on 16 September 1988 when Fonteyn was 69, Nureyev was aged 50, with Carla Fracci also starring, aged 52. Nureyev once said of Fonteyn that they danced with "one body, one soul".

Together Nureyev and Fonteyn premiered Sir Frederick Ashton's ballet Marguerite and Armand, a ballet danced to Liszt's Piano Sonata in B minor, which became their signature piece. They always completely sold out the house. Kenneth MacMillan was forced to allow them to premiere his Romeo and Juliet, which was intended for two other dancers, Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable.Films exist of their partnership in Les Sylphides, Swan Lake, Romeo and Juliet, and other rôles.

Nureyev danced with many of the top ballerinas of his time. He celebrated another long-time partnership with Prima Ballerina Assoluta Eva Evdokimova. They first appeared together in La Sylphide (1971) and in 1975 he selected her as his Sleeping Beauty in his staging for London Festival Ballet. Evdokimova remained his partner of choice for many guest appearances and tours across the globe with "Nureyev and Friends" for more than fifteen years.

Film and television

In 1962, Nureyev made his screen debut in a film version of Les Sylphides. In 1977 he played Rudolph Valentino in Ken Russell's Valentino, but he decided against an acting career in order to branch into modern dance with the Dutch National Ballet in 1968. In 1972, Robert Helpmann invited him to tour Australia with his own production of Don Quixote, his directorial debut. The film version (1973) features Nureyev, Lucette Aldous as Kitri, Helpmann as Don Quixote and artists of the Australian Ballet.

During the 1970s, Nureyev appeared in several films and toured through the United States in a revival of the Broadway musical The King and I. He was one of the guest stars on the television series The Muppet Show where he danced in a parody called "Swine Lake," sang "Baby It's Cold Outside" in a hot tub duet with Miss Piggy, and sang and danced in the show's finale, "Top Hat". In 1981, Thames Television filmed a documentary with Nureyev, including a candid interview, as well as access to him in the studio, rehearsing. In 1982, he became a naturalized Austrian. In 1983 he had a non-dancing role in the movie Exposed with Nastassja Kinski. Also in 1983, he was appointed director of the Paris Opera Ballet, where, as well as directing, he continued to dance and to promote younger dancers. He remained there as a dancer and chief of choreography until 1989. Among the dancers he groomed were Sylvie Guillem, Isabelle Guerin, Manuel Legris, Elisabeth Maurin, Élisabeth Platel, Charles Jude, and Monique Loudieres. Despite advancing illness towards the end of his tenure, he worked tirelessly, staging new versions of old standbys and commissioning some of the most ground-breaking choreographic works of his time. His own Romeo and Juliet was a popular success.

Personality

Nureyev was notoriously impulsive and did not have much patience with rules, limitations and hierarchical order. His impatience mainly showed itself when the failings of others interfered with his work. Most ballerinas with whom he danced, including Antoinette Sibley, Gelsey Kirkland and Annette Page paid tribute to him as a considerate partner.

He socialized with Gore Vidal, Freddie Mercury, Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Mick Jagger, Liza Minnelli, Andy Warhol and Talitha Pol, but developed an intolerance for celebrities. He kept up old friendships in and out of the ballet world for decades, and was considered to be a loyal and generous friend. He was known as extremely generous to many ballerinas, who credit him with helping them during difficult times. In particular, the Canadian ballerina Lynn Seymour – distressed when she was denied the opportunity to premiere Macmillan's Romeo and Juliet – says that Nureyev often found projects for her even when she was suffering from weight issues and depression and thus had trouble finding rôles. He is also said to have helped an elderly and increasingly impoverished Tamara Karsavina.

By the end of the 1970s, when he was in his 40s, he continued to tackle big classical rôles. However by the late 1980s his diminished capabilities disappointed his admirers who had fond memories of his outstanding prowess and skill. Towards the end of his life, when he was sick, he worked on productions for the Paris Opera Ballet. His last work was a production of La Bayadère which closely follows the Kirov Ballet version he danced as a young man.

Personal life

Nureyev met Erik Bruhn, the celebrated Danish dancer, after Nureyev defected to the West in 1961. Nureyev was a great admirer of Bruhn, having seen filmed performances of the Dane on tour in Russia with the American Ballet Theatre, although stylistically the two dancers were very different. Bruhn became the great love of Nureyev's life and the two remained close for 25 years, until Bruhn's death in 1986.

Final years and death

When AIDS appeared in France around 1982, Nureyev took little notice. The dancer tested positive for H.I.V. in 1984, but for several years he simply denied that anything was wrong with his health. Nureyev began a marked decline only in the summer of 1991 and entered the final phase of the disease in the spring of 1992.

In March 1992, Rudolf Nureyev, living with advanced AIDS, visited Kazan and appeared as a conductor in front of the audience at Musa Cälil Tatar Academic Opera and Ballet Theater in Kazan, which now presents the Rudolf Nureyev Festival in Tatarstan Returning to Paris, with a high fever, he was admitted to the hospital Notre Dame du Perpétuel Secours in Levallois-Perret, a suburb northwest of Paris, and was operated on for pericarditis, an inflammation of the membranous sac around the heart. At that time, what inspired him to fight his illness was the hope that he could fulfill an invitation to conduct Prokofiev's "Romeo and Juliet" at an American Ballet Theater's benefit on May 6, 1992 at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. He did so and was elated at the reception.

In July 1992, Nureyev showed renewed signs of pericarditis but determined to forswear further treatment. His last public appearance on October 8, 1992, at the premiere at Palais Garnier of a new production of La Bayadère that he choreographed after Marius Petipa for the Paris Opera Ballet, was a personal triumph although the gravity of his condition was evident. The French Culture Minister, Jack Lang, presented him that evening on stage with France's highest cultural award, the Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Nureyev re-entered the hospital Notre Dame du Perpétuel Secours in Levallois-Perret on November 20, 1992 and remained there until his death from cardiac complication a few months later, aged 54. His grave, at a Russian cemetery in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois near Paris, features a tomb draped in a mosaic of an oriental carpet. Nureyev was an avid collector of beautiful carpets and antique textiles.

Influence

Nureyev's influence on the world of ballet changed the perception of male dancers; in his own productions of the classics the male rôles received much more choreography. Another important influence was his crossing the borders between classical ballet and modern dance by performing both. Today it is normal for dancers to receive training in both styles, but Nureyev was the originator, and the practice was much criticized in his day. (Though Gene Kelly had done much to combine the two styles in film, he came from a more Modern Dance influenced "popular dance" environment, while Nureyev made great strides in gaining acceptance of Modern Dance in the "Classical Ballet" sphere.)

See also

Notes

- Bridcut, John (17 September 2007). "The KGB's long war against Rudolf Nureyev". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Paquito D'Rivera, Ilan Stavans. My sax life. ISBN 0810122189.

- ^ Rudolf Nureyev Foundation official website

- Autobiography Template:Ru icon

- Rudolf Nureyev Foundation official website

- Nureyev.org

- Soutar, Carolyn (2006). The Real Nureyev. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312340974.

- Set and Costume Designs for Don Quixote by Barry Kay for both the stage production at the Adelaide Festival (1970) and Nureyev's movie version, gala world premiere at the Sydney Opera House, 1973.

- McKim, D. W. "Muppet Central Guides – The Muppet Show: Rudolf Nureyev". Retrieved 2009-07-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kavanagh, Julie Nureyev: The Life (2007) ISBN 978-0-375-40513-6

- "Literary Review". Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- "Rudolf Nureyev Foundation Official Website". Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- Roderick Conway Morris (2 8 1997). "Mosaics Move Off the Wall and Onto the Table". New York Times. Retrieved 5 12 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Nureyev Did Have AIDS, His Doctor Confirms". The New York Times. John Rockwell. January 16, 1993. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Yaroslav Sedov. Russian Life. Montpelier: Jan/Feb 2006. Vol. 49, Iss. 1; p. 49

- "Rudolf Nureyev Foundation official website". Retrieved 1 18 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - John Rockwell (13 1 1993). "Rudolf Nureyev Eulogized And Buried in Paris Suburb". New York Times. Retrieved 5 12 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help)

References

- Nureyev, R. (1962). Nureyev: An Autobiography with Pictures. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC: 65776396.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Percival, J. (1976). Nureyev: Aspects of the Dancer. London: Faber. ISBN 0571106277. OCLC: 2689702.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Bland, A. (1977). The Nureyev Valentino: Portrait of a Film. London: Studio Vista. ISBN 0289707951. OCLC: 3933869.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Nureyev, R. (1993). Nureyev: His Spectacular Early Years. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 034060042X. OCLC: 28496501.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Watson, P. (1994). Nureyev: a biography. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0340596155. OCLC: 32162130.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Kaiser, Charles (1997). The Gay Metropolis: 1940–1996. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 404 pages. ISBN 0395657814.

- Sokou, R. (2003). Nureyev-as I knew him. Athens: Kaktos. ISBN 960-382-503-4. .

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Solway, D. (1998). Nureyev, his life. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0688128734. OCLC: 38485934.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Kavanagh, J. (2007). Rudolph Nureyev: The Life. London; New York: Fig Tree. ISBN 1905490151. OCLC: 77013261.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Reviews

- NY Times, Anna Kisselgoff, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, April 9, 1979

External links

- Rudolf Nureyev at IMDb

- Rudolf Nureyev Foundation

- BBC Interviews with Nureyev

- Birthday tribute

- New York Sun review of PBS's "Nureyev: The Russian Years"

| Ballet | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Terminology | |

| Ballet by genre | |

| Ballet by region | |

| Technique |

|

| Occupations and ranks | |

| Ballet apparel | |

| Awards | |

| Organisations | |

| Publications | |

| Related articles | |

| |

| People from Russia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political leaders |

| ||||

| Military figures and explorers | |||||

| Scientists, engineers and inventors | |||||

| Artists and writers | |||||

| Religious leaders | |||||

| Sportspeople | |||||

- Misplaced Pages references cleanup from August 2009

- Articles covered by WikiProject Wikify from August 2009

- AIDS-related deaths in France

- Burials at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery

- Danseurs

- Eastern Bloc defectors

- Soviet emigrants to France

- LGBT dancers

- LGBT people from France

- LGBT people from Austria

- LGBT people from Russia

- Principal dancers of The Royal Ballet

- Russian ballet dancers

- Russian film actors

- Soviet defectors

- Tatar people

- 1938 births

- 1993 deaths

- Ballet choreographers

- Commandeurs of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Prix Benois de la Danse jurors