| Revision as of 00:23, 7 July 2006 view sourceJLaTondre (talk | contribs)Administrators45,017 editsm Fixing links to disambiguation pages using AWB← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:21, 8 July 2006 view source Crissidancer88 (talk | contribs)171 editsm moved Gilan Province to Gilan Province on more Wheels than CanadianCaesar!Next edit → |

| (No difference) | |

Revision as of 01:21, 8 July 2006

Gilan (Persian: گیلان, locally known as Guilan) is one of the 30 provinces of Iran, known during ancient times as part of Hyrcania, with a population of approximately 2 million and an area of 14,700 sq. km. It lies just west of the province of Mazandaran, along the Caspian Sea. The center of the province is the city of Rasht. Other towns in the province include Astara, Astaneh-e Ashrafiyyeh, Rudsar, Langrud, Souma'eh Sara, Talesh, Fuman, Masouleh, and Lahijan.

The main harbor port of the province is Bandar-e Anzali (previously Bandar-e Pahlavi).

History

Ancient history

Archaeological excavations reveal the antiquity of the province to date back to prior to the last Ice Age.

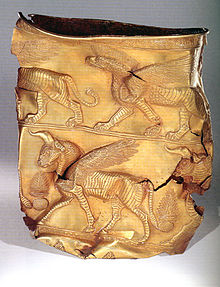

In the 6th century BCE, the inhabitants of Guilan (such as the Gil Gilanshah and Daylam) allied with Cyrus the Great and overthrew the Medes. The province then passed from the control of one dynasty to the next. It is worth noting that people of Gilan were organized in tribes. Caspi (who gave their name to the Caspian sea), and Amardi (who lived in the Sepid Rud valley) were the main two tribes during the Achaemenid dynasty era. By the time of Sassanids, the people of the Gilan's mountains were called Deylamites and the people of the Caspian coast were called Gel, Gelai, Gil or Gilak.

It is worth noting that due to the difficulty of terrain and resistance of the natives, Gilan was loosely allied with the Parthian and Sassanid empires. Sassanid empire did not instal a royal prince, as was the custom. We do not have any records of a Gilanshah (literally, King of Gils), as such a royal prince would have been called, until after the decline of the Sassanids. There is scant evidence about the relationship between local Gil and Deylami chieftains and the Sassanid empire. There is some evidence to believe that members of Ispahbadh clan ruled at least parts of Gilan during the Sassanid era. They seem to have kept their possesions even after the collapse of Sassanids due to the Arab invasions in the mid seventh century CE.

While we know very little about the local customs of Gils and Deylamites, we know that some of their tribes originally revered the river Sepid Rud based on the evidence presented by the Greek geographer Strabo. They were not Zoroastrian prior to Sassanid overlordship, as evidenced by their custom of burying their dead and making human sacrifice. Zoroastrianism gained ground during the Sassanid era. By the time of the Islamic invasion, Gils and Deylamites were mostly Zoroastrian.

Deylamite mercenaries served in Persian armies and where generally considered the best infantry in the middle east up to the time of Mongol invasion. The typical Deylamite troopers either were skirmishers (armed with two-pronged javelins and a light sword or battle-axe) or served as heavy infantry (armed with a long pole weapon, heavy sword, battle-axe, or mace). These soldiers probably used Sagaris-type battle axes. All Deylamite infantrymen carried a round, very large, and strikingly painted shield. Deylamite commander Vahriz (or Vahraz) was instrumental in the conquest of Yemen during the reign of Khosrau I (Anushirvan). Deylamite infantry men were legendry javeliners and had a fearsome reputation in using their battle-axes.

They were highly effective, and could easily engage Byzantine heavy infantrymen, or even Turkic cavalry.

Medieval history

Muslim Arabs never managed to conquer Gilan. Gilaks and Deylamites successfully repulsed any Arab attempt to occupy their land or to convert them to Islam.

In 9th and 10th centuries CE, Deylamites and later Gilaks gradually converted to a heretical sect of Shi'a Islam. It is worth noting that several Deylamite commanders and soldiers of fortune who were active in the military theatres of Iran and Mesopotamia were openly Zoroastrian (for example, Asfar Shiruyeh a warlord in central Iran, and Makan son of Kaki the warlord of Rayy) or were suspected of harboring pro-Zoroastrian (for example Mardavij) sentiments. Muslim chronicles of Varangian (Rus, pre-Russian Norsemen) invasion of the litoral Caspian region in the 9th century record Deylamites as non-Muslim. These chronicles also show that the Deylamite were the only warriors in the Caspian region who could fight the fearsome Varangian vikings as equals. In a way, Deylamite infantrymen had a role very similar to the Swiss Reisläufer of the Late Middle Ages in Europe. Deylamite mercenaries served as far as Egypt, Islamic Spain, and Khazar kingdom.

Buyids established the most successful of the Deylamite dynasties of Iran.

Turkish invasions of 10th and 11th centuries CE, which saw the rise of Ghaznavid and Seljuk dynasties, put an end to Deylamite states in Iran. From 11th century CE to the rise of Safavids, Gilan was ruled by local rulers who paid tribute to the dominant power south of the Alborz range, but ruled independently.

Before introduction of silk production to this region (date unknown, but definitely a pilar of the economy by the 15th century CE), Gilan was a poor province. There were no permanent trade routes linking Gilan to Persia. There was a small trade in smoked fish and wood products. It seems that the city of Qazvin was initially a fortress-town against marauding bands of Deylamites, another sign that the economy of the province did not produce enough. It all changed with the introduction of silk worm sometime in the late middle ages.

Modern history

Safavid emperor, Shah Abbas I ended the rule of Kia Ahmad Khan, the last semi-independent ruler of Gilan, and annexed the province directly to his empire. From this point in history onward, rulers of Gilan were appointed by the Persian Shah.

Safavid empire became weak towards the end of the 17th century CE. By the early 18th century, the once mighty Safavid empire was in the grips of civil war. Peter I of Russia (Peter the Great) sent an expeditionary force that occupied Gilan for a year (1722-1723).

Qajars established a central government in Persia (Iran) in late 18th century CE. They lost s series of wars to Russia (Russo-Persian Wars 1804-1813 and 1826-28), resulting in enormous gain of influence by the Russian empire in the Caspian region. Gilanian cities of Rasht and Anzali were all but occupied by the Russian forces. Anzali served as the main trading port of Iran and Europe.

Gilan was a major producer of silk beginning in 15th century CE. As a result, it was one of the wealthiest provinces in Iran. Safavid annexation in 16th century was at least partially motivated by this revenue stream. Silk trade, though not the production, was a monopoly of the Crown and the single most important source of trade revenue for the imperial treasury. As early as 16th century and until mid 19th century CE, Gilan was the major exporter of silk in Asia. The Shah farmed out this trade to Greek and Armenian merchants, and would receive a portion of the proceeds.

In mid 19th century, a wide spread fatal epidemy in silk worms paralized Gilan's economy, causing widespread economic distress. Gilan's budding industrialists and merchants were increasingly dissatisfied with the weak and ineffective rule of Qajars. Reoreintation of Gilan's agriculture and industry from silk to production of rice and introduction of tea plantations where a partial answer to decline of silk in the province.

After World War I, Gilan came to be ruled independently of the central government of Tehran and concern arose that the province might permanently separate at some point. Prior to the war, Guilanis had played an important role in the Constitutional Revolution of Iran. Sepahdar Tonekaboni (Rashti) was a prominent figure in the early years of the revolution and was instrumental in defeating Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar. In later years (late 1910s), many Gilakis gathered under the leadership of Mirza Kouchak Khan Jangali. Mirza Kochak Kahn became the most prominent revolutionary leader in northern Iran in this period. His movement, known as the Jangalis (Foresters Movement), had sent an armed brigade to Tehran which helped depose the Qajar ruler Mohammad Ali Shah. However, the revolution did not progress the way the constitutionalists had strived for, and Iran came to face much internal unrest and foreign intervention, particularly from the British and Russian Empires.

Guilan's contribution to the movement of Mirza Kouchak Khan Jangali, known as the Constitutionalist movement of Guilan (also Jangalis) is glorified in Iranian history and effectively secured Guilan and Mazandaran against foreign invasions. However, in 1920 British forces invaded Bandar-e Anzali, while being pursued by the Bolsheviks. In the midst of this conflict between Britain and Russia, the Jangalis entered into an alliance with the Bolsheviks against the British. This culminated in the establishment of the Soviet Republic of Gilan, which lasted from June 1920 until September 1921. In February 1921 the Soviets withdrew their support for the Jangali government of Guilan, and signed the Soviet-Iranian Friendship Treaty with the central government of Tehran. The Jangalis continued to struggle against the central government for the rest of that year until their final defeat in September when control of Guilan returned to Tehran.

Rise of the communist power in Russia (USSR) for the better part of the 20th century, along with severe decline in the trade between Iran and Europe through Russia, impoverished Gilan. In effect, from being the most affluent province in Iran in 17th and 19th centuries, Gilan has the highest level of unemployment in Iran right now.

Geography and climate

Guilan has a humid temperate climate with plenty of annual rainfall. The Alborz range provides further diversity to the land in addition to the Caspian coasts.

Large parts of the province are mountainous, green and forested. The coastal plain along the Caspian Sea is similar to that of Mazandaran, mainly used for rice paddies.

In May 1990 large parts of the province were destroyed by a huge earthquake, in which about 45,000 people died. Abbas Kiarostami made his famous films "Nothing but Life" and "Through the Olive Trees" based upon this event.

People and culture

The majority of the population speaks Gilaki as their first language while many children, particularly in the cities, tend to use Standard Persian amongst themselves. Kurdish language is used by some kurds that has moved from khorasan to Amarlu region. Language of Rudbar is Tati.

Gilan's position in between the Tehran-Baku trade route has established the cities of Bandar-e Anzali and Rasht as ranking amongst the most important commercial centers in Iran. As a result, the merchant and middle-classes comprise a significant percentage of the population.

The province has an annual average of 2 million tourists, mostly domestic. Although Iran's Cultural Heritage Organization lists 211 sites of historical and cultural significance in the province, the main tourist attraction in Guilan is the small town of Masouleh in the hills south-east of Rasht. The town is built not dissimilar to the pueblo settlements, with the roof of one house being the courtyard of the next house above.

Gilan has a strong culinary tradition, from which several dishes have come to be adopted across Iran. This richness derives in part from the climate, which allows for a wide variety of fruit, vegetables and nuts grown in the province. Seafood is a particularly strong component of Gilani (and Mazandarani) cuisine. Sturgeon, often smoked or served as kabab, and caviar are delicacies along the whole Caspian littoral. Traditional Persian stews such as ghalieh mahi (fish stew) and ghalieh maygu (shrimp stew) are also featured and prepared in a uniquely Gilani fashion.

More specific to Gilan are a distinctive walnut-paste and pomegranate-juice sauce, used as a marinade for 'sour' kabab (Kabab Torsh) and as the basis of fesenjun, a rich stew of duck, chicken or lamb. Mirza ghasemi is an aubergine and egg dish with a smoky taste that is often served as a side dish or appetizer. Other such dishes include pickled garlic, olives with walnut paste, and smoked fish. The caviar and smoked fish from the region are, in particular, widely prized and sought after specialities in both domestic and foreign gourmet markets. See also Cuisine of Iran.

Colleges and universities

- Gilan University of Mofid

- University of Gilan

- Islamic Azad University of Astara

- Islamic Azad University of Bandar Anzali

- Islamic Azad University of Rasht

- Islamic Azad University of Lahijan

- Gilan University of Medical Sciences

- Institute of Higher Education for Academic Jihad of Rasht (موسسه آموزش عالي غيرانتفاعي جهاد دانشگاهي رشت)

See also

External links

- Picture Gallery of Guilan

- Guilan University of Medical Sciences Health Information Center

- Gilan Cultural Heritage Organization (An excellent source of info in Persian)

- Masouleh Village Official website

- Guilan Province Office of Tourism

- Guilan Province Department of Education (in Persian)