| Revision as of 08:43, 21 January 2015 view sourceAltenmann (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers220,348 edits →See also← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:45, 21 January 2015 view source Altenmann (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers220,348 edits →Militant atheism as state policyNext edit → | ||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

| {{cite book|author=] |year=2006 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=h6Wo5CIgk84C&pg=PA59 |page=59 |title=Antisemitism and Modernity: Innovation and Continuity|publisher=]|quote=The Holbachians formed a considerable atheistic movement, which specialized in attacking Judaism as a means of denigrating its offshoot Christianity.}}</ref> | {{cite book|author=] |year=2006 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=h6Wo5CIgk84C&pg=PA59 |page=59 |title=Antisemitism and Modernity: Innovation and Continuity|publisher=]|quote=The Holbachians formed a considerable atheistic movement, which specialized in attacking Judaism as a means of denigrating its offshoot Christianity.}}</ref> | ||

| == |

==Atheism as state policy== | ||

| In countries where atheism was state policy, this resulted in suppression and persecution of religion, often to extreme degrees. | |||

| ===French Revolution=== | ===French Revolution=== | ||

| ] by English ] ]. Titled "The Radical's Arms", it depicts the infamous guillotine. "No God! No Religion! No King! No Constitution!" is written in the republican banner.]] | ] by English ] ]. Titled "The Radical's Arms", it depicts the infamous guillotine. "No God! No Religion! No King! No Constitution!" is written in the republican banner.]] | ||

Revision as of 08:45, 21 January 2015

| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This redirect was last edited by Altenmann (talk | contribs) 10 years ago. (Update timer) |

Militant atheism is a form of atheism which actively opposes, combats religion. Militant atheists have a desire to propagate atheism, and differ from moderate atheists because they hold religion to be pernicious. Militant atheism was an integral part of the materialism of Marxism-Leninism, and significant in the French Revolution, atheist states such as the Soviet Union, and Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. The term militant atheist has been used going back to at least 1882, and it has been applied to political thinkers.

Recently the term militant atheist has been used, often pejoratively, to describe atheists such as Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett and Victor Stenger — prominent representatives of the New Atheism movement. The appellation has been criticized by some activists, such as Dave Niose, who feel that the term is used indiscriminately for "an atheist who had the nerve to openly question religious authority or vocally express his or her views about the existence of God."

Concepts

In his Oxford University Press book, titled Atheism, which is part of a larger series of Very Short Introductions, British philosopher and journalist Julian Baggini states that he describes an atheistic active hostility to religion as militant and says that this hostility "requires more than just strong disagreement with religion – it requires something verging on hatred and is characterized by a desire to wipe out all forms of religious belief." Militant atheists, Baggini continues, "tend to make one or both of two claims that moderate atheists do not. The first is that religion is demonstrably false or nonsense, and the second is that it is usually or always harmful." According to Baggini, the "too-zealous" militant atheism found in the Soviet Union was characterized by thinking the best way to counter religion was "by oppression and making atheism the official state credo."

Philosopher Kerry S. Walters contends that militant atheism differs from moderate atheism because it sees belief in God as pernicious. In the same vein, militant atheism, according to theologian Karl Rahner, regards itself as a doctrine to be propagated for the happiness of mankind and combats every religion as a harmful aberration; "militant" atheism differs from the philosophy of "theoretical" atheism, which he states, may be tolerant and deeply concerned.

Under régimes which espoused militant atheism, such as Albania under Enver Hoxha and Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, in which traditional religion was banned, when the wave of militant atheism passes, traditional religion may reappear with undiminished strength when conditions allow for the expression of grassroots identities.

Historical roots

| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This redirect was last edited by Altenmann (talk | contribs) 10 years ago. (Update timer) |

The idea that atheism must actively combat religion originates is the Age of Enlightenment and associates with the names such as Denis Diderot, Claude Adrien Helvétius, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Leo Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach.

Nikolai Berdyaev wrote that with respect to atheism, Karl Marx was a disciple of Feuerbach in that religion is an illusory product of the consciousness. Marx developed this notion from the philosophy of mind into the sphere of social relations. Still, militant atheism of Marx was calling for the changes in consciousness. Militant atheism of Vladimir Lenin moved from the intellectual sphere into emotional one; it was a genuine hatred of religion. For him atheism was part of the revolutionary struggle.

Sociologist Rodney Stark describes Thomas Hobbes and the other originators of the 'social "scientific" study of religion' as "militant opponents of religion" whose "militant atheism...was motivated partly by politics". The 19th-century political activist Charles Bradlaugh has been called a militant atheist by several authors, and is often credited as the first militant atheist in the history of Western civilization. The term has also been applied to other 19th-century political thinkers such as Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach, Annie Besant, and Schopenhauer.

A significant militant atheist movement known as the Holbachians, disciples of militant atheist Baron d'Holbach, opposed Judaism, Christianity and Deism.

Atheism as state policy

In countries where atheism was state policy, this resulted in suppression and persecution of religion, often to extreme degrees.

French Revolution

Counter-Enlightenment writers frequently charged the philosophes with militant atheism which sought to destroy the Church and the monarchical form of government." Two prominent militant atheists of the French Revolution included Jacques Hébert and Baron Anacharsis Cloots, who both advocated the dechristianisation of France. Cloots, says Alister McGrath, did not believe in religious tolerance. He vigorously campaigned for the atheistic Cult of Reason, which was officially proclaimed on 10 November 1793. According to James Gray, Thomas Holcroft, an English militant atheist, was instrumental in founding the London Corresponding Society in 1792, "whose main aim was to connect with radical elements in Paris in the same year".

Soviet Union

According to Harold J. Berman, a Harvard specialist in Soviet law, "militant atheism was the official religion, one might say, of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party was the established church." The militant atheism of the Bolsheviks owed its origins not just to the "standard Marxist feeling that religion was the opium of the masses", but also to the fact that the Russian Orthodox Church had "always been a pillar of czarism." The goal of the Soviet Union was the liquidation of religion and the means to achieve this goal included the destruction of churches, mosques, synagogues, mandirs, madrasahs, religious monuments, as well the mass deportation to Siberia of believers of different religions. Under the Soviet doctrine of separation of church and state, detailed in the Constitution of the Soviet Union, churches in the Soviet Union were forbidden to give to the poor or carry on educational activities. They could not publish literature since all publishing was done by state agencies, although after World War II the Russian Orthodox Church was given the right to publish church calendars, a very limited number of Bibles, and a monthly journal in a limited number of copies. Churches were forbidden to hold any special meetings for children, youth or women, or any general meetings for religious study or recreation, or to open libraries or keep any books other than those necessary for the performance of worship services. Furthermore, under militant atheist policies, Church property was expropriated. Moreover, not only was religion banned from the school and university system, but pupils were to be indoctrinated with atheism and antireligious teachings. For example, schoolchildren were asked to convert family members to atheism and memorize antireligious rhymes, songs, and catechisms, while university students who declined to propagate atheism lost their scholarships and were expelled from universities. Severe criminal penalties were imposed for violation of these rules. By the 1960s, with the fourth Soviet anti-religious campaign underway, half of the amount of Russian Orthodox churches were closed, along with five out of the eight seminaries. In addition, several other Christian denominations were brought to extinction, including the Baptist Church, Methodist Church, Evangelical Christian Church, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Before the Russian Revolution, there were more than fifty thousand Russian Orthodox clergymen, by 1939, there were no more than three to four hundred left. In the year 1922 alone, under the militant atheistic system, 2691 secular priests, 1962 monks and 3447 nuns were martyred for their faith. Due to the militant atheistic campaigns against Judaism, the religion was inaccessible to its followers; most Soviet Jews focused on a national identity, which fueled a mass dissident movement. Marxist-Leninist militant atheism resulted in the administrative elimination of the clergy, the housing of atheist museums where churches had once stood, the sending of many religious people to prisons and concentration camps, a continuous stream of propaganda, and the imposing of atheism through education (and forced re-education through torture at various prisons). Specifically, by 1941, 40,000 Christian churches and 25,000 Muslim mosques had been closed down and converted into schools, cinemas, clubs, warehouses and grain stores, or Museums of Scientific Atheism.

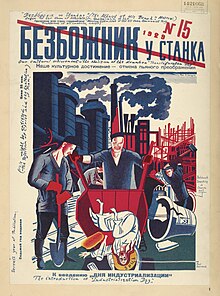

Oscar J. Hammen, an American historian, classified Engels as a militant atheist, although the Soviet professor, N. Lobkowicz, challenged the assertion that Marx was a militant atheist. The ascent of the Bolsheviks to power in 1917 "meant the beginning of a campaign of militant atheism." and in 1922 Lenin, himself a militant atheist, referred with approval to "militant atheist literature" and demanded that the journal Pod Znamenem Marksizma "must be a militant atheist organ", explaining that he meant militant 'in the sense of unflinchingly exposing and indicting all modern “graduated flunkeys of clericalism”, irrespective of whether they act as representatives of official science or as free lances calling themselves “democratic Left or ideologically socialist” publicists'. In 1923, the Bezbozhnik ("Atheist", or "Godless") magazine appeared, around which the "Union of the Friends of the Bezbozhnik" was formed in 1924. The organization, renamed the League of Militant Atheists (Template:Lang-ru, Soyuz voinstvuyushchikh bezbozhnikov) in 1929, along with the Tatar Union of the Militant Godless, carried out anti-religious propaganda at the grassroots level. In 1941, soon after the Nazi invasion of the USSR, the newspaper closed, and in 1947 the society itself folded, the task of the anti-religious propaganda being transferred to the more neutrally named All-Union Society for the Dissemination of Political and Scientific Knowledge (Всесоюзное общество по распространению политических и научных знаний). Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a Soviet concentration camp survivor, wrote of the The Union of the Militant Godless, stating that its members "went on rampages, blew out candles, and smashed icons with axes." The League of Militant Atheists, which was renamed the Znanie Society (Общество "Знание"), published a monthly journal called Nauka i Religya (Science and Religion) which described itself as "a fighting organ of militant atheism", rejecting the view that religion would disappear "of itself." In 1961 the Ukrainian branch produced a similar journal called Militant Atheist (Voivnichy Ateist).

Scientists and party philosophers in the Soviet Union worked to establish a view of science acceptable to Marxist-Leninist philosophy. In addition to the antireligious substance of each course, the curriculum from the universities in the Soviet Union presented scientific findings correct or incorrect based on their supposed ideological positions, not on the objective, applied, and experimental essence of science. Some Soviet militant atheists also believed science disproved religion because God remained unseen, his miracles were never subject to empirical verification, and certain religious stories were scientifically inconceivable. Bruce Sheiman, himself an atheist, states that militant atheists are incorrect in asserting that science is capable of determining the existence of God.

Joseph McCabe, who has himself been called a militant atheist, wrote in 1936 that "Russia is doing the finest and soundest reconstructive work of our time, and it is doing this, not only without God, but on a basis of militant Atheism." However, militant atheism failed to eradicate Christianity, which resulted, starting in 1939, in the reopening of churches, the abandonment of the atheist teaching in schools, and the restoration of the seven day week. Moreover, John W. Garver observes that the collapse of the Soviet Union ended the dominance of militant atheism over South-Central Asia and led to the reemergence of Islam in the region.

Czechoslovakia

When communists seized power in former Czechoslovakia in February 1948, part of their agenda was also a fight against “dangerous ideological enemy that holds enormous influence on the masses”. Thus, the monasteries had been seized by state security service (StB) during three so called “barbaric nights” in 1950. In total, 3142 people were relocated by force into concentrating monasteries. These were in case of male members of orders virtually turned into prison camps or labor camps secured with guards and strict regime aiming the “political re-education” of monks. The 213 monastery buildings and facilities were confiscated by state and content of many ancient precious libraries that survived even Turko-Tatar attacks in the middle ages was scrapped and used for cardboard production.”

In 1957 ŠtB arrested university students in eastern Slovakia town Košice who held Bible study meetings. The consequent investigations lead to further arrests of Christians and lawsuit in 1959 with non-public hearing and coverage by state-controlled media. Newspapers brought up the case under titles „Poison in gold-foil“, „Sects are eradicating the thinking of youth“ and „Report on trial with blue crusaders“ (Blue Cross was Christian abstinent association fighting alcoholism). The arrested members of Blue Cross were found „guilty“ of „spreading hostile Christian ideology“ that is „contradicting scientific Marxist ideology“. They were sentenced pursuant to paragraph on subversion of republic. At the same time their personal correspondence, typing machines and Christian literature was confiscated, mainly the one written by national author Kristína Royová, regarded by some authors for "Slovak Kierkegaard".

People's Republic of China and the Cultural Revolution

The People's Republic of China is officially an atheist state, as atheism is endorsed and promoted by the ruling Chinese Communist Party. When the People's Republic of China was established, militant atheist functionaries compelled the Party to impose control on and limit religious suppliers. As a result, foreign missionaries were expelled from the nation. Furthermore, major religions including Buddhism, Daoism, Islam and Christianity were co-opted into national associations, while minor sects were labelled as reactionary organisations and were therefore banned.

However, during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a new form of militant atheism made great efforts to eradicate religion completely. Under this militant atheism espoused by Mao Zedong, houses of worship were shut down; Buddhist pagodas, Daoist temples, Christian churches, and Muslim mosques were destroyed; artifacts were smashed; and sacred texts were burnt. Moreover, it was a criminal offence to even possess a religious artifact or sacred text. However, following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, many former policies towards religious freedom returned although they are limited and tenuous, as religion is closely regulated by the government.

According to philosopher Julia Ching, the Falun Gong religion was seen by Jiang Zemin, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, as an ideological threat to militant atheism and historical materialism. Nevertheless, Fengang Yang, a professor at Purdue University, writes that the "predominant view on religion has moved away from militant atheism to a more scientific, objective and consequently more balanced approach to religion."

See also

- State atheism

- Soviet anti-religious legislation

- Treatment of Christians in the Soviet Union

- The Trouble with Atheism (film)

Notes and references

- ^

Julian Baggini (2009). Atheism. Sterling Publishing. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

Militant Atheism: Atheism which is actively hostile to religion I would call militant. To be hostile in this sense requires more than just strong disagreement with religion—it requires something verging on hatred and is characterized by a desire to wipe out all forms of religious beliefs. Militant atheists tend to make one or both of two claims that moderate atheists do not. The first is that religion is demonstrably false or nonsense, and the second is that is is usually or always harmful.

- ^

Karl Rahner (1975). Encyclopædia of Theology: A Concise Sacramentum Mundi. Continuum International Publishing Group. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

Atheism A. In Philosophy I. Concept and incidence. Philosophically speaking, atheism means denial of the existence of God or of any possibility of knowing God. In those who hold this theoretical atheism, it may be tolerant (and even deeply concerned), if it has no missionary aims; it is "militant" when it regards itself as a doctrine to be propagated for the happiness of mankind and combats every religion as a harmful aberration.

Cite error: The named reference "Rahner" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^

Kerry S. Walters (2010). Atheism. Continuum International Publishing Group. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

Both positive and negative atheism may be further subdivided into (i) militant and (ii) moderate varieties. Militant atheists, such as physicist Steven Weinberg, tend to think that God-belief is not only erroneous but pernicious. Moderate atheists agree that God-belief is unjustifiable, but see nothing inherently pernicious in it. What leads to excess, they argue, is intolerant dogmatism and extremism, and these are qualities of ideologies in general, religious or nonreligious.

Cite error: The named reference "Walters" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). -

Phil Zuckerman (2009). Atheism and Secularity: Issues, Concepts, and Definitions. ABC-CLIO. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

In contrast, militant atheism, as advocated by Lenin and the Russian Bolsheviks, treats religion as the dangerous opium and narcotic of the people, a wrong political ideology serving the interests of antirevolutionary forces; thus force may be necessary to control or eliminate religion.... militant atheism leads to antireligious measures (Dai 2001, 38-57) Militant atheism is so radical and left-leaning that it merely lasted 30 years or so (i.e.1949-1979) and dwindled away... at the end of 1978.

-

Yang, Fenggang (2004). "Between Secularist Ideology and Desecularizing Reality: The Birth and Growth of Religious Research in Communist China" (PDF). Sociology of Religion. 65 (2): 101–119.

Scientific atheism is the theoretical basis for tolerating religion while carrying out atheist propaganda, whereas militant atheism leads to antireligious measures. In practice, almost as soon as it took power in 1949, the CCP followed the hard line of militant atheism. Within a decade, all religions were brought under the iron control of the Party: Folk religious practices considered feudalist superstitions were vigorously suppressed; cultic or heterodox sects regarded as reactionary organizations were resolutely banned; foreign missionaries, considered part of Western imperialism, were expelled; and major world religions, including Buddhism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism, were coerced into "patriotic" national associations under close supervision of the Party. Religious believers who dared to challenge these policies were mercilessly banished to labor camps, jails, or execution grounds.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Yang, Fenggang (2006). "The Red, Black, and Gray Markets of Religion in China" (PDF). The Sociological Quarterly. 47 (1): 93–122.

In contrast, militant atheism, as advocated by Lenin and the Russian Bolsheviks, treats religion as a dangerous narcotic and a troubling political ideology that serves the interests of antirevolutionary forces. As such, it should be suppressed or eliminated by the revolutionary force. On the basis of scientific atheism, religious toleration was inscribed in CCP policy since its early days. By reason of militant atheism, however, atheist propaganda became ferocious, and the power of "proletarian dictatorship" was invoked to eradicate the reactionary ideology (Dai 2001)

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Charles Colson, Ellen Santilli Vaughn (2007). "God and Government". Zondervan. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

But Nietzsche's atheism was the most radical the world had yet seen. While the old atheism had acknowledged the need for religion, the new atheism was political activist, and jealous. One scholar observed that "atheism has become militant . . . inisisting it must be believed. Atheism has felt the need to impose its views, to forbid competing versions."

Cite error: The named reference "Colson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Harold Joseph Berman (1993). Faith and Order: The Reconciliati oyn of Law and Religion. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

One fundamental element of that system was its propagation of a doctrine called Marxism-Leninism, and one fundamental element of that doctrine was militant atheism. Until only a little over three years ago, militant atheism was the official religion, one might say, of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party was the established church in what might be called an atheocratic state.

- ^

J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (1996). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 289. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

For seventy years, from the Bolshevik Revolution to the closing years of the Gorbachev regime, militant atheism was the official religion, one might say, of the Soviet Union, and the Communist Party was, in effect, the established church. It was an avowed task of the Soviet state, led by the Communist Party, to root out from the minds and hearts of the Soviet state, all belief systems other than Marxism-Leninism.

- ^ Alister E. McGrath. The Twilight of Atheism: The Rise and Fall of Disbelief in the Modern World. Random House. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

So was the French Revolution fundamentally atheist? There is no doubt that such a view is to be found in much Christian and atheist literature on the movement. Cloots was at the forefront of the dechristianization movement that gathered around the militant atheist Jacques Hébert. He "debaptised" himself, setting aside his original name of Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce. For Cloots, religion was simply not to be tolerated.

- ^ Gerhard Simon (1974). Church, State, and Opposition in the U.S.S.R. University of California Press. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

On the other hand the Communist Party has never made any secret of the fact, either before or after 1917, that it regards 'militant atheism' as an integral part of its ideology and will regard 'religion as by no means a private matter'. It therefore uses 'the means of ideological influence to educate people in the spirit of scientific materialism and to overcome religious prejudices..' Thus it is the goal of the C.P.S.U. and thereby also of the Soviet state, for which it is after all the 'guiding cell', gradually to liquidate the religious communities.

- ^

Simon Richmond (2006). Russia & Belarus. BBC Worldwide. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

Soviet 'militant atheism' led to the closure and destruction of nearly all the mosques and madrasahs (Muslim religious schools) in Russia, although some remained in the Central Asian states. Under Stalin there were mass deportations and liquidation of the Muslim elite.

- ^ The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge Studies in Social Theory, Religion and Politics). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Seeking a complete annihilation of religion, places of worship were shut down; temples, churches, and mosques were destroyed; artifacts were smashed; sacred texts were burnt; and it was a criminal offence even to possess a religious artifact or sacred text. Atheism had long been the official doctrine of the Chinese Communist Party, but this new form of militant atheism made every effort to eradicate religion completely.

-

Strahan, A. (1882). The Contemporary review. Vol. 42.

In Germany, a new Protestant Caesarism has essayed the part of jailer of human souls to its Catholic subjects; while in France, Jacobinism, which is identical in its ethos with Caesarism—the tyrant being legion instead of one, and clad in blouse instead of in imperial purple—is labouring, with all the fanaticism of militant atheism, to overthrow and destroy the rights of the spiritual side of man's nature.

- Rodney Stark; Roger Finke (2000). "Acts of Faith: explaining the human side of religion". University of California Press. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

The militant atheism of the early social scientists was motivated partly by politics. As Jeffrey Hadden reminds us, the social sciences emerged as part of a new political "order that was at war with the old order" (1987, 590).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Elaine A. Heath (2008). "Mystic Way of Evangelism". Baker Academic. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

Richard Dawkins's Foundation for Reason and Science is out to debunk religion, which Dawkins calls "the God delusion." His book of the same title is a best seller, and Dawkins is not alone. Sam Harris, Daniel C. Den-nett, Victor J. Stenger, and Christopher Hitchens are only a handful of militant atheists who are convinced Christianity is toxic to human life.

-

Marcelo Gleiser (2010). "A Tear at the Edge of Creation". Simon & Schuster. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

Scientists such as Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, philosopher Daniel Dennett, and British journalist and polemicist Christopher Hitchens, a group sometimes referred to as "the Four Horsemen," have taken the offensive, deeming religious belief a form of "delusion," a dangerous kind of collective madness that has wreaked havoc upon the world for millennia. Their rhetoric is the emblem of a militant radical atheism, a view I believe is as inflammatory and intolerant as that of the religious fundamentalists they criticize.

-

Fiala, Andrew. "Militant atheism, pragmatism, and the God-shaped hole". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. 65 (3): 139–51.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) -

Michael Babcock (2008). "Unchristian America". Tyndale House. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

MILITANT ATHEISM The change in tone is most evident in the writings of the so-called New Atheists-Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens-men who have been trying to accelerate a process that's been under way for centuries.

- Dave Niose (1894). "The Myth of Militant Atheism". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2011-07-09.

When the media and others refer to a "militant atheist," the object of that slander is usually an atheist who had the nerve to openly question religious authority or vocally express his or her views about the existence of God.

- Baggini 2009 p. 131

- C. M. Hann (1993). "Socialism: ideals, ideologies, and local practice". Psychology Press. p. 8.

It may disappear from view during the apogee of Marxism-Leninism, when the old temples are likely to be sacred (though only Albania and Cambodia went so far as formally to ban traditional religion per se). When the wave of militant atheism passes and conditions permit the expression of grassroots identities once again, traditional religion may reappear with undiminished strength.

- Christopher Marsh. "Religion and the State in Russia and China: Suppression, Survival, and Revival". Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 18.

Religious belief is quite distinct from a philosophical viewpoint, however, meaning that almost all previous studies have avoided serious consideration of the theological roots of militant atheism. While it is with Hegel that one must begin to understand Marxist philosophy, one must take a detour through the thought of Schleiermacher, Strauss, and Feuerbach before coming to an understanding of Marx's and Engels's critique of religion.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - Nikolai Berdyaev, Глава VII. Коммунизм и христианство (Ch. 7, Communism and Christianity)

- Rodney Stark "Atheism, Faith and the Social Scientific Study of Religion" Journal of Contemporary Religion Vol 14 No 1 1999, pp. 41–62.

- Laurel Brake, Marysa Demoor (2009). Dictionary of nineteenth-century journalism in Great Britain and Ireland. Academia Press. p. 566.

A well-set Sunday weekly* selling for 1 d, the Secular Review's stance was representative of a relatively moderate style of Secularism, sympathetic to socialism and aligned against the individualism and militant atheism of Charles Bradlaugh and his National Reformer. In its discussion of religion, philosophy, ethics, science and history, and in reviewing Secularism and 'what purports to be so, and is not', the title's stated domain of inquiry was 'this world, without implying disregard or denial of another' (Holyoake 1876).

-

Craig Ott; Harold A. Netland (2006). Globalizing Theology: Belief and Practice in an Era of World Christianity. Baker Academic. p. 190.

She was a close friend and coworker of Charles Bradlaugh, the militant atheist and first president of the National Secular Society (set up in 1866), and helped to edit his journal, the National Reformer.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

James Richard Moore (2002). History, Humanity and Evolution: Essays for John C. Greene. Cambridge University Press. p. 286.

Though at first allied with the militant atheist Charles Bradlaugh (1833–91) and his National Secular Society (NSS), the elder Watts refused in 1877 to defend Bradlaugh's right to republish Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy, a pamphlet on on birth control.

-

Bryan S. Turner (2011). Religion and Modern Society: Citizenship, Secularisation and the State. Cambridge University Press. p. 129.

Secularism, when under the inspiration of militant atheists such as Charles Bradlaugh, Member of Parliament for Northhampton in Great Britan, assumed a more striden, uncrompromising and critical relationship to religious belief.

-

Madalyn Murray O'Hair. "Agnostics". American Atheist Online Services. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

Charles Bradlaugh was the first militant Atheist in the history of Western civilization. He was elected to the British parliament six times, and each time that body refused to seat him because he was an Atheist – and because he would not swear his allegiance to queen and country, so help him "God." Everyone in England knew Bradlaugh and his fight, and he raised the issue of Atheism to every person in public life as he sought allies.

-

Ian Hill Nish, Hugh Cortazzi (2003). Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits. Psychology Press. p. 335.

At South Place, Robert Young also came to know Charles Bradlaugh (1833–91), the first militant Atheist.

- The Debate Between Feuerbach and Stirner: An Introduction, in The Philosophical Forum 8, numbers 2–4, (1976) – available on the web here

- Annie Wood Besant (2003). Theosophist Magazine Collection 1920–1955. Kessinger Publishing. p. 155.

Madame Blavatsky, a Russian, suspected of being a spy, converted Anglo-Indians to a passionate belief in her Theosophy mission, even when the Jingo fever was the hottest, and in her declining years she succeeded in winning over to the new-old religion Annie Besant, who had for years fought in the forefront of the van of militant atheism.

- Joel H. Spring (2001). Globalization and educational rights: an intercivilizational analysis. Psychology Press. p. 127.

Annie Besant had an important influence on Nehru's family and on social reform in India. Born in 1847, she was known in England as 'Red Annie' because of her activities as a militant atheist, socialist, and trade union organizer.

- S. W. Jackman, Sydney Wayne Jackman (2003). Deviating voices: women and orthodox religious tradition. James Clarke & Co. p. 139.

The final chapter of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky's life was to be shared with the individual who probably became her most famous disciple, namely, Annie Besant, who had had two children while married to an Anglican clergyman, but was now a militant atheist and radical.

- Gerard Mannion (2003). Schopenhauer, religion and morality: the humble path to ethics. Ashgate Publishing. p. i.

This work challenges the textbook assessment of Schopenhauer as militant atheist and absolute pessimist.

- Jean-François Marmontel (1895). Marmontel's Moral Tales. Ballantyne, Hanson & Co. p. xxxv.

It certainly stopped altogether short of the militant atheism of the Holbachian coterie; and it may be doubtful whether, except in the ardour of the novitiate, it reached Voltaire's dislike of positive creeds.

- ^ Gerald Robert McDermott (2000). Jonathan Edwards Confronts the Gods: Christian Theology, Enlightenment Religion, and Non-Christian Faiths. Oxford University Press. p. 27.

The Holbachians were disciples of Baron d'Holbach, a militant atheist who opposed both Christianity and desim (because it was theistic).

-

Hyam Maccoby (2006). Antisemitism and Modernity: Innovation and Continuity. Psychology Press. p. 59.

The Holbachians formed a considerable atheistic movement, which specialized in attacking Judaism as a means of denigrating its offshoot Christianity.

- Mark Bevir (2010). Encyclopedia of Political Theory, Volume 1. SAGE Publications. p. 329.

Moreover, materialism simultaneously was expected to undermine religious faith, and the philosophes, despite their wide variety of religious views, were charged with a militant atheism bent on the destruction of church and throne alike. As these pillars of traditional society were under attack, Counter-Enlightenment writers predicted horrific scenes of anarchy, chaos, perversion, and bloodshed. When the French Revolution culminated in regicide and the Reign of Terror, the bloody warnings of the anti-philosophes suddenly appeared prophetic.

- Timothy Ferris (2008). The Science of Liberty: Democracy, Reason, and the Laws of Nature. Harper. p. 86.

Locked up in the Luxembourg prison, he passed the time debating religion with his friend Anacharsis Cloots, a militant atheist, until Cloots was guillotined on March 24.

- John Keane (2003). Tom Paine: A Political Life. Harper. p. 86.

nvariably, their conversations turned into heated arguments, with Paine resisting the militant atheism of Cloots, who regularly called himself "Jesus Christ's personal enemy" and berated Paine "for his credulity in still indulging so many religious and political prejudices."

- Jean-Pierre Gross (1997). Fair Shares for All: Jacobin Egalitarianism in Practice. Cambridge University Press. p. 23.

It is not without significance in this regard that, while many of the confirmed terrorists were militant atheists, who took naturally to blasphemy and adhered to the dechristianisation movement in the autumn and winter of 1793, the moderates were often deists who shared Robespierre's and Tom Paine's belief in the usefulness of religion.

- Christine L. Krueger; George Stade; Karen Karbiener; Book Builders Llc (COR). Encyclopædia of British Writers: 19th and 20th Centuries. Infobase Publishing. p. 164.

Holcroft, Thomas (1745–1809) playwright, novelist A militant atheist and a fervent believer in the individual's capacity for self-improvement, he was drawn into a circle of political and social radicals that included Thomas Paine, John Tooke, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ James Gray. "Review of The French Revolution and the London Stage 1789–1805, by George Taylor". Cambridge University Press.

In two chapters devoted to reactions of the English stage to the Reign of Terror in France, Taylor notes that Thomas Holcroft (1745–1809), a militant atheist and a pro-Revolutionary zealot, helped to found in 1792 the London Corresponding Society, whose main aim was to connect with radical elements in Paris in the same year.

-

Harold J. Berman (1998). "Freedom of Religion in Russia: An Amicus Brief for the Defendant". HeinOnline.

from the Bolshevik Revolution to the closing years of the Gorbachev regime, militant atheism was the official religion, one might say, of the Soviet Union, and the Communist Party was, in effect, the established church.

- Crane Brinton (1995). A History of Civilization: 1648 to the present. Prentice Hall. p. 357.

- Dimitry Pospielovsky (1998). The Orthodox Church in the History of Russia. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 395.

It might be expected that as a Christian leader, he would at least declare that a Christian could not vote for a party that preached and practiced genocide, whether racial or class-based, nor for a party whose ideology included a militant atheism aiming at liquidation of religion.

-

Melvin Ember; Carol R. Ember; Ian Skoggard (2005). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities (v. 1). Springer Science+Business Media. p. 988.

The militant atheism of the Soviet period put an end to the traditional beliefs, religion, and rituals of Koreans.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

Ruth Ellen Gruber (2007). National Geographic Jewish Heritage Travel. National Geographic Society. p. 99.

But the hundreds of thousands of Jews in the Soviet sector were subject to the regime's ruthless campaign of militant atheism. Synagogues were closed, demolished, or converted for secular use, and religious life was crushed.

-

Albert Lee (1980). Henry Ford and the Jews. Stein and Day. p. 108.

The atheist Jew, Gubermann, under the name of Jaroslawski and then the leader of the militant atheists in Soviet Union, also declared: 'It is our duty to destroy every religious world concept.'

-

World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 1980. p. 1387.

A campaign of militant atheism began. Many churches – as well as synagogues, mosques, and Buddhist temples – were closed or destroyed. For example, some eight thousand Russian Orthodox churches were closed in 1937 alone.

- ^ Berman 2009, p. 395. "Under the doctrine of separation of church and state, churches in the Soviet Union were forbidden to engage in any activities that were within the sphere of responsibilities of the state. That meant, for example, that churches could not give to the poor or carry on educational activities. They could not publish literature since all publishing was done by state agencies, although after World War II the Russian Orthodox Church was given the right to publish church calendars, a very limited number of Bibles, and a monthly journal in a limited number of copies. Churches were forbidden to hold any special meetings for children, youth or women, or any general meetings for religious study or recreation, or to open libraries or keep any books other than those necessary for the performance of worship services. Severe criminal penalties were imposed for violation of these rules. The formula of the 1936 and 1977 Soviet Constitutions was: freedom of religious worship and freedom of atheist propaganda – meaning, first no freedom of religious teaching other than the worship service itself, and second, a vigorous campaign in the schools and universities, in the press, and in special meetings organized by atheist so-called 'agitators,' to convince people of the folly of religious beliefs."

- Christel Lane (1978). Christian Religion in the Soviet Union: A Sociological Study. State University of New York Press. p. 232.

Militant atheist measures, both in premeditated and in unforeseen ways, have also caused far-reaching changes in the organisational structure of collectivities, in the ways they perform their religious functions and in which believers satisfy their religious requirements. In the field of organisation, most measures have had the effect of weakening or destroying central organisation and strengthening local independence and spontaneity.

- J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (1996). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 290.

Churches, mosques, and synagogues were deprived of almost all activities except the conduct or worship services. Moreover, schools were not merely to avoid the teaching of religion; they were actively to promote the teaching of atheism. These doctringes were spelled out in a 1929 law that remained the basic legistlation on the subject until the Gorbachev reforms of the late 1980s. There was freedom of religious worship, but churches were forbidden to give any material aid to their memebers or charity of any kind, or to hold any special meetings for children, youth, or women, or general meetings for religious study, recreation, or any similar purpose or to open libraries or to keep any books other thanose necessary for the performance of worhsip services. The formula of the 1929 law was repeated in the 1936 Constitution and again in the 1977 Constitution: freedom of religious worship and freedom of atheist propaganda-meaning (1) no freedom of religious teaching outside of the worship service itself, plus (2) a vigorous campaign in the schools, in the press, and in special meetings organized by atheist agitators, to convice people of the folly of religious beliefs.

- R. J. Overy (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 271.

The communist regime treated the Church as a political institution rather than as a set of beliefs. On 28 January 1918 the Russian Orthodox Church was formally separated from the state; religious belief was permitted as long as it did not threaten public order or trespass on political soil. Religious property was liquidated, and a twenty-year programme of church closures begun. Religion was banned from schools. The state and the party were officially atheist.

-

Richard Sakwa (1999). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union, 1917–1991. Psychology Press. p. 74.

Marx's view on religion as the 'opiate of the people' under the Bolsheviks took the form a militant atheism that sought to destroy the social sources of the power of the Church, and to extirpate religious belief as a social phenomenon. Uner the slogan of separating Church and state, the Bolsheviks in effect expropriated church property and dramatically limited the Church's ability to conduct a normal religious life.

- J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (1996). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 290.

Moreover, schools were not merely to avoid the teaching of religion; they were actively to promote the teaching of atheism.

- ^ Paul Froese (2008). The Plot to Kill God: findings from the Soviet experiment in Secularization. University of California Press. pp. 58, 79.

Militant atheists also believed that science disproved religion because God remained unseen, his miracles were never subject to empirical verification, and certain religious stories were inconceivable. As such, the Soviet school system consistently promoted "atheistic science" to combat the effects of religion. The curriculum of scientific atheism resembled the curriculum of scientific atheism resembled the curriculum for much of the Soviet educational system, as it was based more on memorization than critical analysis. For homework, schoolchildren were sometimes asked to convert a member of their family to atheism by reciting arguments that were intended to disprove religious beliefs. And schoolchildren often memorized antireligious rhymes, songs, and catechisms. Antireligious ideas infiltrated the most basic in unrelated topics: "Physics, biology, chemistry, astronomy, mathematics, history, geography and literature all serve as jumping-off points to instruct pupils on the evils or falsity of religion." Although many school subjects appear unrelated to religion, Soviets believed that any intellectual activity was intrinsically opposed to religion. The Soviet educational system officially stated that "that bringing up of children in the atheist spirit" was one of its primary missions. University students were also required to actively propogate atheism and were told, "Those who refuse to make such practical application of their study will lose their scholarships and must leave the university. Special pressure was placed on academics and scientists to join the atheist educational organization Znanie, and, b the late 1970s, for example, over 80 percent of all professors and doctors of science in Luthuania became members. The course syllabi from the atheist universities of the Soviet Union indicate how the topic of atheism was presented as a historically logical outcome of scientific development.

- J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (1996). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 290.

In 1960 Criminal Code of the Russian Republic imposed a fine for violating lasw of separation from the state and of the school from the church, and, for repeated violators, deprivation of freedom up to three years (Article 142). Such violations included organizing religious assemblies and processions, organizing religious instruction for minors, and preparing written materials calling for such activities. Other types of religious activities were subject to more severe sanctions: thus leaders and active participants in religious groups that caused damage to the health of citizens or violted personal rights, or that tried to persuade citizens not to participate in social activities or to perform duties of citizens, or that drew minors into such group, were punishable by deprivation of freedom up to give years (Article 277).

-

J. D. Van der Vyver, John Witte (1996). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 291. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

These articles of the Criminal Code were enacted as part of the severe anti-religious campaign launched under Khrushchev in the early 1960s, when an estimated 10,000 Russian Orthodox churches-half the total number-were closed, together with five of the eight insitutions for training priests, and the independence of the priesthood were curtailed both nationally and locally.

-

Thomas Hoffmann; William Alex Pridemore (2003). "Esau's Birthright and Jacob's Pottage: A Brief Look at Orthodox-Methodist Ecumenism in Twentieth-Century Russia" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

One of these was the resurgence of non-Orthodox Christian confessions, including the Methodist Church – a denomination completely eradicated in Russia during the Soviet era.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Paul Froese (2008). The Plot to Kill God: findings from the Soviet experiment in Secularization. University of California Press. pp. 58, 79.

There were more than fifty thousand Orthodox priests before the Russian Revolution, and by mid-1939, there were no more than three to four hundred clergy.

- John Meyendorff (1987). Witness to the World. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 225.

After having been the state religion for centuries both in Russian and in almost all the countries of Europe, Christianity suddenly was confronted with a militant atheistic system claiming to regulate not only the material, but also the spiritual life of man. The number of those who died for the faith is innumerable: in the year 1922 alone, 2691 secular priests, 1962 monks and 3447 nuns.

Quoted from N. Struve, Christians in Russia, Harvill Press, London, 1967, p. 38 -

Timothy Ware (1993). The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books. p. 145.

The Ottoman Turks, while non-Christians, were still worshippers of the one God and, as we have seen, allowed the Church a large measure of toleration. But Soviet Communism was committed by its fundamental principles to an aggressive and militant atheism. Not only were churches closed on a massive scale in the 1920s and 1930s, but huge numbers of bishops and clergy, monks, nuns and laity were sent to prison and to concentration camps. How many were executed or died from ill-treatment we simply cannot calculate. Nikita Struve provides a list of martyr-bishops running to 130 names, and even this he terms 'provisional and incomplete'. The sum total of priest-martyrs must extend into tens of thousands.

- Robert S. Wistrich (1995). Terms of Survival: the Jewish World since 1945. Psychology Press. p. 266.

Anti-Semitism, too, was relatively mild in the USSR during these interim post-Stalin years, despite the militant atheistic campaigns against the Jewish religion and the implication of Jews in economic crimes under Khruschev.

- ^ David Singer] (1998). American Jewish Year, Book 1998. Amer Jewish Committee. p. 30.

For most Soviet Jews, raised in an atmosphere of militant atheism, Judaism was inaccessible; and so the Soviet Jewish renaissance focused instead on national identity. Israel and its military victories, especially the Six Day War, emboldened thousands of young Jews to form the Soviet Union's only mass, nationwide, dissident movement.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Jews" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - De James Thrower (1983). Marxist-Leninist Scientific Atheism and the Study of Religion and Atheism in the USSR. Walter de Gruyter. p. 135.

In the pre-war period the emphasis was on 'practical atheism' – the more so as Stalin, the sole arbiter in such matters had not made a single theoretical pronouncement on religion or the study of religion – and 'practical atheism' meant schools from the propagation of atheism, the administrative elimination of the clergy, atheist museums where churches had once stood, and a continuous stream of hate-propaganda designed to terrorise the faithful into submission.

- A short history of Soviet socialism, p. 126. ISBN 9781857283556

- Orthodox Christianity and Militant Atheism in the Twentieth Century

- Paul Kurtz, Vern L. Bullough, Tim Madigan (1994). Toward a New Enlightenment: the philosophy of Paul Kurtz. Transaction Books. p. 171.

There have been fundamental and irreconcilable differences between humanists and atheists, particularly Marxist-Leninists. The defining characteristic of humanism is its commitment to human freedom and democracy; the kind of atheism practiced in the Soviet Union has consistently violated basic human rights.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Allan Todd, Sally Waller (2011). Origins and Development of Authoritarian and Single Party States. Cambridge University Press. p. 53.

By the time of the Nazi invasion in 1941, nearly 40,000 Christian churches and 25,000 Muslims mosques had been closed down and converted into schools, cinemas, clubs, warehouses and grain stores, or Museums of Scientific Atheism.

-

Allan Todd, Sally Waller. "Crispin Paine". Present Pasts. 1.

By the time of the Nazi invasion in 1941, nearly 40,000 Christian churches and 25,000 Muslims mosques had been closed down and converted into schools, cinemas, clubs, warehouses and grain stores, or Museums of Scientific Atheism.

- Freidrich Engels Encyclopedia Britannica 2008.

- Lobkowicz, N (1964). "Karl Marx's Attitude toward Religion", The Review of Politics, Vol. 26 (3), July, pp.319–352. , see also

- John F. Pollard (2001). Benedict XV: the unknown pope and the pursuit of peace p. 199.

- Edward Craig. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. p. 564.

Lenin, leader of the October 1917 Revolution in Russia, wrote mainly about politics and economics, but as a Marxist of his generation he assumed that ideas about society needed to rest on sound philosophical premises. He was a militant atheist.

- On the Significance of Militant Materialism Lenin 1922

- Журнал "БЕЗБОЖНИК", Москва, СССР (Bezbozhnik Magazine, Moscow, USSR). The page is in UTF-8 encoding. The caption to the front page picture of the No. 1 issue, by Dmitry Moor, shown in the article, is "We've finished with the earthly kings – now it's time to take care of the heavenly ones!"

- Alexandre A. Bennigsen, S. Enders Wimbush (1980). Muslim National Communism in the Soviet Union: A Revolutionary Strategy for the Colonial World. University of Chicago Press. p. 202.

In disgrace after Sultan Galiev's trial in 1928, he was, until his final purge in 1937, chairman of the Tatar Union of Militant Godless.

- Michael Kemper; Stephan Conermann (2011). The Heritage of Soviet Oriental Studies. Taylor & Francis. p. 69.

The League of the Militant Godless and the Knowledge Society conducted anti-religious propaganda at the grassroots level.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sabrina P. Ramet (1993). Religious Policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press. p. 14.

Local public and voluntary organisations – the Komsomol, the Young Pioneers, workers' Clubs and, of course, the League of Militant Atheists – were encouraged to undertake a whole range of anti-religious initiatives: promoting the observance of the five day working week, ensuring that priests did not visit believers in their homes, supervising the setting-up of cells of the League of Militant Atheists in the army. Public lampoons and blasphemous parades, recalling the early 1920s, were resumed from 1928. One of the main activities of the League of Militant Atheists was the publication of massive quantities of anti-religious literature, comprising regular journals and newspapers as well as books and pamphlets. The number of printed pages rose from 12 million in 1927 to 800 million in 1930.

-

William G. Rosenberg (1990). Bolshevik Visions: First Phase of the Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia, Part 1. University of Michigan Press. p. 18.

The publication in 1923 of Yaroslavsky's response to Khegund (see below), signalled the beginning of an organized ant-religious movement. Many in the party still urged caution; the "League of Militant Atheists, formally the a "private union" rather than a party body, was not permitted to function until 1925.

-

M. Searle Bates (2005). Religious Liberty: An Inquiry. Kessinger Publishing Company. p. 6.

On the other hand, the League of Militant Atheists reported for 1932 an organization of 80,000 cells with 7,000,000 members, besides 1,500,000 children in affiliated groups.

- Союз воинствующих безбожников (Union of the Militant Atheists) in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- Joseph Pearce (2011). Solzhenitsyn: A Soul in Exile. Ignatius Press. p. 72.

In the years immediately before and after the Revolution, the church was shunned and subjected to ridicule by young people and the intelligentsia. Solzhenitsyn rememberd how many fiery adherents were claimed by militant atheism in the 1920s. "Those who went on rampages, blew out candles, and smashed icons with axes have now crumbled into dust, like their Union of the Militant Godless."

- "Знание", Всесоюзное общество (The All-Union "Knowledge" Society) in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- ^ John Anderson (1994). Religion, state, and politics in the Soviet Union and successor states. Cambridge University Press. p. 44.

Finally, various public organisations were drawn into the struggle against religion, most notably the Znanie Society. Formed in 1947, in large part as a successor to the disbanded League of the Militant Godless, the society had begun to expand its work beyond the narrowly anti-religious. In September 1959 it at last produced the first copy of the monthly atheist magazine Nauka i religiya. The unusual decision to commence publication part way through the year perhaps suggested the increasing degree of urgency in anti-religious campaigning. The first editorial reflected this mood in describing the journal as 'a fighting organ of militant atheism' and in its rejection of the view that religion would disappear 'of itself.'

- Helge Kragh (2008). Entropic Creation. Ashgate Publishing. p. 226.

In the attempts to establish an ideologically acceptable view of science, the new physics became a matter of considerable controversy in the young Soviet Union. Physicists and party philosophers discussed the problematic relationship of relativity theory and quantum mechanics to Marxist-Leninist philosophy.

- Paul Froese (2008). The Plot to Kill God: findings from the Soviet experiment in Secularization. University of California Press. pp. 58, 79.

Militant atheists also believed that science disproved religion because God remained unseen, his miracles were never subject to empirical verification, and certain religious stories were inconceivable. The course syllabi from the atheist universities of the Soviet Union indicate how the topic of atheism was presented as a historically logical outcome of scientific development; Soviet college students chose from the following course selections: Physics...Chemistry...Geology...Mathematics...Biology...Medicine...What stands out in these syllabi, in addition to the antireligious substance of each course, is the way in which the curriculum appears to ignore the objective, applied, and experimental essence of science. Instead, scientific findings are presented as correct or incorrect based on their supposed ideological positions. Religion is presented as the historic cofounder of scientific advancement, with atheism providing the phislosophical framework from which to conduct accurate science.

- Paul Froese (2008). The Plot to Kill God: findings from the Soviet experiment in Secularization. University of California Press. pp. 58, 79.

Militant atheists also believed science disproved religion because God remained unseen, his miracles were never subject to empirical verification, and certain religious stories were scientifically inconceivable. Following World War II and after the dissolution of the League of Militant Atheists, Soviet officials started a campaign to produce natural-scientific arguments against belief in God. For instance, Soviet scientists placed holy water under a microscope to prove that it had no special properties, and the corpses of saints were exhumed to demonstrate that they too were subject to corruption. These activities indicated that atheist propgandists held a very literal interpretation of religious language; for them, holy water and the bodies of saints were expected to hold some physical sign of their divinity.

- Christian De Duve (2002). Life Evolving: Molecules, Mind, and Meaning. Oxford University Press. p. 53.

Contrary to what is sometimes claimed, a naturalistic view of the origin of life does not necessarily exlude belief in a Creator. The notion, propagated at the same time, though for opposite reasons, by militant atheistic scientists and by many antiscientific circles, that the findings of science are incompatible with the existence of a Creator is false.

- Bruce Sheiman (2009). An Atheist Defends Religion: Why Humanity is Better Off with Religion Than Without It. Penguin Books. p. 119.

The militant atheist asserts, incorrectly, that science is capable of determining the nonexistence of God.

- Madalyn Murray O'Hair. The Atheist World. Kessinger Publishing.

This is a listing of the great and near great compiled by Joseph McCabe, ex-Roman Catholic priest and militant Atheist of early in this century.

- Joseph McCabe (2010). Is the Position of Atheism Growing Stronger?. Kessinger Publishing.

For the news is spreading, and is triumphing even over reactionary opposition that Russia is doing the finest and soundest reconstructive work of our time, and it is doing this, not only without God, but on a basis of militant atheism.

- Earle E. Cairns (1996). Christianity through the centuries: a History of the Christian Church. Zondervan. p. 455.

The failure of militant atheism to eradicate Christianity; the persistence of belief in God, which approximately half of the Russian people expressed in the 1937 census; and the threatening international situation dictated the need for a strategic retreat after 1939. Churches were reopened, the antireligious carnivals were dropped, and the teaching of atheism in schools was abandoned. In 1943 Sergius was permitted to function as the patriarch of Moscow and all Russia. The seven-day week was restored, seminaries were permitted to reopen, and the Orthodox church was freed of many burdensome restrictions.

- John W. Garver (2006). China and Iran: Ancient Partners in a Post-Imperial World. University of Washington Press. p. 130.

Post-Soviet Central Asia witnessed a swift revival of Islam. The collapse of Soviet power lifted a seventy-year-long reign of militant atheism and opened the way to reemergence of the long-suppressed Islamic faith of the Central Asian peoples.

- NMI (2011). "Likvidácia kláštorov v komunistickom Československu – Barbarská noc ("Eradication of monasteries in communist Czechoslovakia – Barbaric night")". Nation's Memory Institute.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - NMI (2011). "Likvidácia kláštorov v komunistickom Československu – Barbarská noc, výpovede svedkov ("Eradication of monasteries in communist Czechoslovakia – Barbaric night, reports of witnesses")". Nation's Memory Institute.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - Slavka, M.; et al. (1994). Naše korene. Bratislava: Nádej. p. 187. ISBN 80-7120-029-8.

In 1957 StB arrested Miloš Rataj, undergraduate student in Košice. He was a son of teacher and poet Ján Rataj. Miloš Rataj together with his fellow students held private Bible Study and prayer meetings at the hostel belonging to university campus. Somebody reported their activities to authorities what triggered investigations and later leaded to a lawsuit. In the newspaper „Východoslovenské Noviny" there were consequently published articles „Poison in gold-foil" (No.41 in 1959), „Sects are eradicating the thinking of youth" and „Report on trial with blue crusaders". It was just a preparation for more thorough trial at court in Bratislava, where prior to that trial further church members had been arrested, namely Ing. O. Lupták, Ing. Vl. Matej, J. Rosa and J. Hollý from Stará Turá. The hearings during the trial were behind the closed doors excluding the public (sep 1959). The main guilt of accused was that they as members of blue cross „spread hostile Christian ideology" that is „contradicting scientific Marxist ideology". They were sentenced pursuant to paragraph on subversion of republic. At the same time their personal correspondence, typing machines and Christian literature was confiscated, mainly the one written by national author Kristína Royová.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - Trúsik, Pavol (2/2011). "Kristína Royová – slovenský Kierkegaard? (Kristína Royová – Slovak Kierkegaard?)". Ostium, Internet journal for humanitarian science. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

We can conclude that (Kristína) Royová was sort of Slovak version of Kierkegaard.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - China in the 21st century. Oxford University Press. p. 108.

China is still officially an atheist country, but many religions are growing rapidly, including evangelical Christianity (estimates of how many Chinese have converted to some form of Protestantism range widely, but at least tens of millions have done so) and various hybrid sects that combine elements of traditional creeds and belief systems (Buddhism mixed with local folk cults, for example).

- The State of Religion Atlas. Simon & Schuster. p. 108.

Atheism continues to be the official position of the governments of China, North Korea and Cuba.

- ^ The New Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Religion. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 432.

As soon as the PRC was established, militant atheism compelled the party to impose control and limitations on religious suppliers. Foreign missionaries, who were considered a part of Western imperialism, were expelled, and cultic or heterodox sects that were regarded as reactionary organizations (fandong hui dao men), were banned. Further, major religions – Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism, which were difficult to eliminate and possesed diplomatic value for the isolated regime – were co-opted into national associations.

- ^ Bryan S. Turner. Religion and Modern Society: Citizenship, Secularisation and the State. Cambridge University Press. p. 129.

The contrast between religion in American and militant atheism in China could not have been more stark or profound. While the Red Guards under Mao Zedong's leadership were busy destroying Buddhist pagodas, Catholic churches and Daoist temples, the Christian Right were equally busy condemning the communists.

- Julie Ching (1 January 2001). "The Falun Gong: Religious and political implications". American Asian Review. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

Now, Jiang is emphasizing the need for people, especially party members, to study politics. He accepts the threat of Falun Gong as an ideological one: spiritual beliefs against militant atheism and historical materialism. He wishes to purge the government and the military of such beliefs. His decision is in line with the suspicion of religious protest by the traditional Chinese state. As it turns out, the government's campaign against "evil cults" includes popular folk cults, as well as underground Christians-Catholics and Protestants who meet at house churches.

- Fengang Yang (2004). "Between Secularist Ideology and Desecularizing Reality: The Birth and Growth of Religious Research in Communist China". Sociology of religion. 65: 101.

Under the ride of the Chinese Communist Party, the scholarship of religious research in China has changed from virtual nonexistence in the first thirty years (1949–1979) to flourishing in the reform era (1979–present). Moreover, the predominant view on religion has moved away from militant atheism to a more scientific, objective and consequently more balanced approach to religion. This paper attempts to trace this intellectual history in China and to examine the role of academia in the religious scene. There are three distinct periods in this development: the domination of atheism from 1949 to 1979, the birth of religious research in the 1980s, and the growth of the scholarship in the 1990s, despite political restrictions. Religious research was intended by the government to serve atheist propaganda, but it grew into an independent academic discipline responsive to the desecularizing reality.

Further reading

- Nikolai Berdyaev, Генеральная линия советской философии и воинствующий атеизм ("General Line of Soviet Philosophy and Militant Atheism"), 1932

- New Myth, New World: From Nietzsche to Stalinism by Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal Publisher: Pennsylvania State University Press (November 2002) ISBN 978-0271022185

- Nietzsche and Soviet Culture: Ally and Adversary (Cambridge Studies in Russian Literature) various authors edited by Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal Publisher: Cambridge University Press ISBN 978-0521452816

- What the God-seekers found in Nietzsche: The Reception of Nietzsches Übermensch by the Philosophers of the Russian Religious Renaissance. (Studies in Slavic Literature & Poetics) by Nel Grillaert Publisher: Rodopi (October 22, 2008) ISBN 978-9042024809

- Stalin's Holy War Religion, Nationalism, and Alliance Politics, 1941–1945 by Steven Merritt Miner Copyright 2002 by the University of North Carolina Press ISBN 0-8078-2736-3

- Nietzsche in Russia Publisher by Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal Princeton Univ Pr ISBN 978-0691102092

- Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical by Chris Matthew Sciabarra Publisher: Pennsylvania State University Press ISBN 0271014415

- The Returns of History: Russian Nietzscheans After Modernity by Dragan Kujundzic Publisher: State University of New York Press ISBN 978-0791432341

- A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist-Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti-Religious Policies, by Dimitry V. Pospielovsky. Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0312381328

- Soviet Antireligious Campaigns and Persecutions (History of Soviet Atheism in Theory and Practice and the Believers, Vol 2),Dimitry Pospielovsky, (November, 1987), Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0312009054

- Soviet Studies on the Church and the Believer's Response to Atheism: A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory and Practice and the Believers, Vol 3, Dimitry Pospielovsky, (August, 1988), Palgrave Macmillan, hardcover: ISBN 0312012918, paperback edition: ISBN 0312012926

- Great Soviet encyclopedia, ed. A. M. Prokhorov (New York: Macmillan, London: Collier Macmillan, 1974–1983) 31 volumes, three volumes of indexes.

- The Russian Church and the Soviet State by John Shelton Curtiss, 1917–1950 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1953)

- Storming the Heavens: The Soviet League of the Militant Godless by Daniel Peris Cornell University Press 1998 ISBN 9780801434853

- Sacred causes : the clash of religion and politics from the Great War to the War on Terror by Michael Burleigh Paperback: 576 pages Publisher: Harper Perennial (March 11, 2008) ISBN 978-0060580964

- Religious and anti-religious thought in Russia By George Louis Kline The Weil Lectures Published in 1968, University Press (Chicago)

- "Godless Communists": Atheism and Society in Soviet Russia 1917–1932. by William B. Husband DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. 2000. Pp. xviii, 241.

- A History of Russia. Nicholas V. Riasanovsky and Mark D. Steinberg. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 800 pages. ISBN 0195153944

External links

- Christian Post: Militant Atheism Gives Rise to Christian Apologetics

- A TED talk by Richard Dawkins on Militant Atheism

- Beware of Religion!: a rebirth of Militant Atheism in Moscow. by Dmitry Ageev, Department for External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate. (Article comments on the destruction by "believers" of allegedly blasphemous artworks at an exhibition in Moscow, and discusses the implications of the exhibition.)

- "Men Have Forgotten God" – The Templeon Address by Aleksander Solzhenitsyn (translated). This is the speech by Solzhenitsyn at the Guild Hall following his receiving the Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion award in 1983.

- How Russians survived militant atheism to embrace God

| Links to related articles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||