| Revision as of 09:20, 11 October 2015 view source2607:fb90:1808:a421:94f6:d4eb:68c6:d53f (talk) →The Intifada: Fixed typoTags: canned edit summary Mobile edit Mobile app edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 09:22, 11 October 2015 view source 2607:fb90:1808:a421:94f6:d4eb:68c6:d53f (talk) →The Intifada: Fixed grammarTags: canned edit summary Mobile edit Mobile app editNext edit → | ||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

| On 8 December 1987, an Israeli army transporter got into an accident with cars containing Palestinians returning from working in Israel, at the ]. Four Palestinians, three of them residents of the ] refugee camp, the largest of the eight refugee camps in the Gaza Strip, were killed and seven others injured. The traffic incident was witnessed by hundreds of Palestinian labourers returning home from work.<ref>Vitullo p.46.</ref> The funerals, attended by 10,000 people from the camp that evening, quickly led to a large violent demonstration. Rumours swept the camp that the incident was an act of intentional retaliation for the stabbing to death of an Israeli businessman, killed while shopping in Gaza two days earlier.<ref>Ruth Margolies Beitler,''The path to mass rebellion: an analysis of two intifadas,'' Lexington Books, 2004 p.xiii.</ref><ref>Vitullo, p.46:'No one cooperated with military interrogators, who arrested suspects and instituted a curfew on the area.'</ref> Following the throwing of a petrol bomb by a Palestinian at a passing patrol car in the Gaza Strip on the following day, Israeli forces, firing with tear gas canisters into angry rioters, shot one young Palestinian dead and wounded 16 others.<ref>Beitler,''The path to mass rebellion,'' p.116 n.75.</ref><ref>Tessler, ''A History of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,'' pp.677-8.</ref> | On 8 December 1987, an Israeli army transporter got into an accident with cars containing Palestinians returning from working in Israel, at the ]. Four Palestinians, three of them residents of the ] refugee camp, the largest of the eight refugee camps in the Gaza Strip, were killed and seven others injured. The traffic incident was witnessed by hundreds of Palestinian labourers returning home from work.<ref>Vitullo p.46.</ref> The funerals, attended by 10,000 people from the camp that evening, quickly led to a large violent demonstration. Rumours swept the camp that the incident was an act of intentional retaliation for the stabbing to death of an Israeli businessman, killed while shopping in Gaza two days earlier.<ref>Ruth Margolies Beitler,''The path to mass rebellion: an analysis of two intifadas,'' Lexington Books, 2004 p.xiii.</ref><ref>Vitullo, p.46:'No one cooperated with military interrogators, who arrested suspects and instituted a curfew on the area.'</ref> Following the throwing of a petrol bomb by a Palestinian at a passing patrol car in the Gaza Strip on the following day, Israeli forces, firing with tear gas canisters into angry rioters, shot one young Palestinian dead and wounded 16 others.<ref>Beitler,''The path to mass rebellion,'' p.116 n.75.</ref><ref>Tessler, ''A History of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,'' pp.677-8.</ref> | ||

| On 9 December, several popular Palestinian leaders held a press conference in West Jerusalem with the ] in response to the deterioration of the situation. While they convened, reports came in that demonstrations at the Jabalya camp were underway and that a 20-year-old terrorist had been shot to death after throwing a petrol bomb at Israeli soldiers. He would later become known as the first ] of the intifada.<ref>Vitullo, p.46. writes 20 year old man.</ref><ref name="Intifada, p.284">'Intifada,' in David Seddon,(ed.)''A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East,''p.284.</ref> Protests rapidly spread into the West Bank and Jerusalem. Rioters took control of neighbourhoods, closed off camps with barricades of garbage, stone and burning tires, meeting soldiers who endeavoured to break through with petrol bombs. Palestinian shopkeepers closed their businesses, and labourers refused to turn up to their work in Israel. |

On 9 December, several popular Palestinian leaders held a press conference in West Jerusalem with the ] in response to the deterioration of the situation. While they convened, reports came in that demonstrations at the Jabalya camp were underway and that a 20-year-old terrorist had been shot to death after throwing a petrol bomb at Israeli soldiers. He would later become known as the first ] of the intifada.<ref>Vitullo, p.46. writes 20 year old man.</ref><ref name="Intifada, p.284">'Intifada,' in David Seddon,(ed.)''A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East,''p.284.</ref> Protests rapidly spread into the West Bank and Jerusalem. Rioters took control of neighbourhoods, closed off camps with barricades of garbage, stone and burning tires, meeting soldiers who endeavoured to break through with petrol bombs. Palestinian shopkeepers closed their businesses, and labourers refused to turn up to their work in Israel. Rioters stripped one Israeli down to his underwear in front of Shifa hospital. Within days the occupied territories were engulfed in a wave of riots and violence on an unprecedented scale. Specific elements of the occupation were targeted for attack: military vehicles, Israeli buses and Israeli banks. None of the dozen Israeli settlements were attacked. <ref>Vitullo, p.47</ref> Equally unprecedented was the extent of mass participation in these riots: tens of thousands of civilians, including women and children. The Israeli security forces used the full panoply of crowd control measures to try and quell the disturbances: cudgels, nightsticks, ], water cannons, rubber bullets. But the rioters only gathered momentum.<ref name="Shlaim2000_450-451">], pp. 450–1.</ref> | ||

| Soon there was widespread ], road-blocking and tire burning throughout the territories. By 12 December, six Palestinians had died and 30 had been injured in the violence. The next day, rioters threw a gasoline bomb at the U.S. consulate in ].<ref name="Intifada, p.284"/> | Soon there was widespread ], road-blocking and tire burning throughout the territories. By 12 December, six Palestinians had died and 30 had been injured in the violence. The next day, rioters threw a gasoline bomb at the U.S. consulate in ].<ref name="Intifada, p.284"/> | ||

Revision as of 09:22, 11 October 2015

For Sahrawi uprising, see First Sahrawi Intifada.

| First Intifada | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict | |||||||

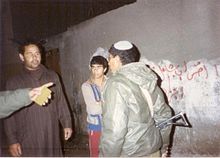

IDF roadblock outside Jabalya during the First Intifada, 1988 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Supported by; | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Yitzhak Shamir | Marwan Barghouti | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

160 Israelis killed

|

2,044 Palestinians killed

| ||||||

The First Intifada or First Palestinian Intifada (also known as simply as "the intifada" or "intifadah") was a Palestinian uprising against the Israeli seizure of the West Bank and Gaza from Jordan and Egypt during the 1967 war, which lasted from December 1987 until the Madrid Conference in 1991, though some date its conclusion to 1993, with the signing of the Oslo Accords. The uprising began on 9 December, in the Jabalia refugee camp after a traffic incident when an Israeli Defense Forces' (IDF) truck collided with a civilian car, killing four Palestinians. In the wake of the incident, an increase in violence arose, involving a two-fold strategy of armed resistance and rioting, consisting of general strikes, boycotts of Israeli Civil Administration institutions in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, an economic boycott consisting of refusal to work in Israeli settlements on Israeli products, refusal to pay taxes, refusal to drive Palestinian cars with Israeli licenses, graffiti, barricading, and widespread throwing of stones and Molotov cocktails at the Israelis and infrastructure within Israel.100 Israeli civilians and 60 IDF personnel were killed often by militants under the influence of the Intifada’s UNLU, and more than 1,400 Israeli civilians and 1,700 soldiers were injured. Intra-Palestinian violence was also a prominent feature of the Intifada, with widespread executions of an estimated 822 Palestinians killed as alleged collaborators,(1988–April 1994). At the time Israel reportedly obtained information from some 18,000 Palestinians who had been compromised, although fewer than half had any proven contact with the Israeli authorities.

The ensuing Second Intifada took place from September 2000 to 2005.

General causes

After Israel's seizing of the West Bank, Jerusalem, Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Jordan and Egypt in the Six-Day War in 1967, frustration grew among local Arabs in the Israeli territories. Israel opened its labor market to Palestinians in the newly occupied territories. Palestinians were recruited mainly to do unskilled or semi-skilled labor jobs. By the time of the Intifada, over 40 percent of the Palestinian work force worked in Israel daily. Additionally, high birth rates in the territories and the limited allocation of land for new building and agriculture created conditions marked by growing population density and rising unemployment, even for those with university degrees. At the time of the Intifada, only one in eight college-educated Palestinians could find degree-related work. Couple this with an expansion of a Palestinian university system catering to people from refugee camps, villages, and small towns generating new Palestinian elite from a lower social strata that was more activist and confrontational with Israel.

The Israeli Labor Party's Yitzhak Rabin, the then Defense Minister, added deportations in August 1985 to Israel's "Iron Fist" policy of cracking down on Palestinian terrorism. This, which led to 50 deportations in the following 4 years, was accompanied by economic integration and increasing Israeli settlements such that the Jewish settler population in the West Bank alone nearly doubled from 35,000 in 1984 to 64,000 in 1988, reaching 130,000 by the mid nineties. Referring to the developments, Israeli minister of Economics and Finance, Gad Ya'acobi, stated that "a creeping process of de facto annexation" contributed to a growing militancy in Palestinian society.

Background

While the immediate cause for the First Intifada is generally dated to a truck incident involving several Palestinian fatalities at the Erez Crossing in December 1987, Mazin Qumsiyeh argues, against Donald Neff, that it began with multiple youth riots earlier in the preceding month. Some sources consider that the perceived IDF failure in late November 1987 to stop a Palestinian terrorist operation, the Night of the Gliders, in which six Israeli soldiers were killed, helped catalyze local Palestinians to riot.

In two incidents on 1 and 6 October 1987, respectively, the IDF ambushed and killed seven Gaza men, reportedly affiliated with Islamic Jihad, who had escaped from prison in May. Some days later, Intisar al-'Attar, was shot for stone throwing while in her schoolyard in Deir al-Balah by a civilian in the Gaza Strip. The Arab summit in Amman in November 1987 focused on the Iran–Iraq War, and the Palestinian issue was shunted to the sidelines for the first time in years.

Leadership and aims

The Intifada was not initiated by any single individual or organization. Local leadership came from groups and organizations affiliated with the PLO that operated within the Territories; Fatah, the Popular Front, the Democratic Front and the Palestine Communist Party. The PLO's rivals in this activity were the Islamic organizations, Hamas and Islamic Jihad as well as local leadership in cities such as Beit Sahour and Bethlehem. However, the uprising was predominantly led by community councils led by Hanan Ashrawi, Faisal Husseini and Haidar Abdel-Shafi, that promoted independent networks for education, medical care, and food aid. The Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU) gained credibility where the Palestinian society complied with the issued communiques. There was a collective commitment to abstain from lethal violence, a notable departure from past practice, which, according to Shalev arose from a calculation that recourse to arms would lead to undermine the support they had in Israeli liberal quarters. The PLO and its chairman Yassir Arafat had also decided on an unarmed strategy, in the expectation that negotiations at that time would lead to an agreement with Israel. Pearlman attributes the non-violent character of the uprising to the movement's internal organization and its capillary outreach to neighbourhood committees that ensured that lethal revenge would not be the goal. Hamas and Islamic Jihad cooperated with the leadership at the outset, and throughout the first year of the uprising conducted three armed attacks, the stabbing of a soldier in October 1988, and the detonation of two roadside bombs.

Leaflets publicizing the uprising's aims demanded the complete withdrawal of Israel from the territories it had taken from Jordan and Egypt in 1967: the lifting of curfews and checkpoints; it appealed to Palestinians to join in rioting; it also called for the establishment of the Palestinian state on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, abandoning the standard rhetorical calls, still current at the time, for the "liberation" of all of Palestine.

The Intifada

Israel's drive into the occupied territories had occasioned spontaneous acts of violence, but the administration, pursuing an "iron fist" policy of curfews and the suppression of political institutions, was confident that Palestinian resistance was exhausted. The assessment that the unrest would collapse proved to be mistaken.

On 8 December 1987, an Israeli army transporter got into an accident with cars containing Palestinians returning from working in Israel, at the Erez checkpoint. Four Palestinians, three of them residents of the Jabalya refugee camp, the largest of the eight refugee camps in the Gaza Strip, were killed and seven others injured. The traffic incident was witnessed by hundreds of Palestinian labourers returning home from work. The funerals, attended by 10,000 people from the camp that evening, quickly led to a large violent demonstration. Rumours swept the camp that the incident was an act of intentional retaliation for the stabbing to death of an Israeli businessman, killed while shopping in Gaza two days earlier. Following the throwing of a petrol bomb by a Palestinian at a passing patrol car in the Gaza Strip on the following day, Israeli forces, firing with tear gas canisters into angry rioters, shot one young Palestinian dead and wounded 16 others.

On 9 December, several popular Palestinian leaders held a press conference in West Jerusalem with the Israeli League for Human and Civil Rights in response to the deterioration of the situation. While they convened, reports came in that demonstrations at the Jabalya camp were underway and that a 20-year-old terrorist had been shot to death after throwing a petrol bomb at Israeli soldiers. He would later become known as the first martyr of the intifada. Protests rapidly spread into the West Bank and Jerusalem. Rioters took control of neighbourhoods, closed off camps with barricades of garbage, stone and burning tires, meeting soldiers who endeavoured to break through with petrol bombs. Palestinian shopkeepers closed their businesses, and labourers refused to turn up to their work in Israel. Rioters stripped one Israeli down to his underwear in front of Shifa hospital. Within days the occupied territories were engulfed in a wave of riots and violence on an unprecedented scale. Specific elements of the occupation were targeted for attack: military vehicles, Israeli buses and Israeli banks. None of the dozen Israeli settlements were attacked. Equally unprecedented was the extent of mass participation in these riots: tens of thousands of civilians, including women and children. The Israeli security forces used the full panoply of crowd control measures to try and quell the disturbances: cudgels, nightsticks, tear gas, water cannons, rubber bullets. But the rioters only gathered momentum.

Soon there was widespread rock-throwing, road-blocking and tire burning throughout the territories. By 12 December, six Palestinians had died and 30 had been injured in the violence. The next day, rioters threw a gasoline bomb at the U.S. consulate in East Jerusalem. The Israeli response was swift. Israel used mass arrests of Palestinians, engaged in collective punishments like closing down West Bank universities for most years of the uprising, and West Bank schools for a total of 12 months. Round-the-clock curfews were imposed over 1600 times in just the first year. At any one time, 25,000 Palestinians would be confined to their homes. Palestinian refusals to pay taxes were met with confiscations of property and licenses, new car taxes, and heavy fines for any family whose members had been identified as terrorists.

Casualties

In the first year in the Gaza Strip alone, 142 Palestinians were killed. From 57,000 to 120,000 were arrested. 481 were deported Between December 1987 and June 1991, 120,000 were injured and 15,000 arrested. In the first five weeks alone, 35 Palestinians were killed and some 1,200 wounded, a casualty rate that only energized the uprising by drawing more Palestinians into participating. B'Tselem official statistics place the total Israeli killed at 200 over the same period. 3,100 Israelis, 1,700 of them soldiers, and 1,400 civilians suffered injuries.

Israel adopted a policy of arresting key representatives of Palestinian institutions. After lawyers in Gaza went on strike to protest their inability to visit their detained clients, Israel detained the deputy head of its association without trial for six months. Dr. Zakariya al-Agha, the head of the Gaza Medical Association, was likewise arrested and held for a similar period of detention, as were several women active in Women's Work Committees. During Ramadan, many camps in Gaza were placed under curfew for weeks, impeding residents from buying food, and Al-Shati, Jabalya and Burayj were subjected to saturation bombing by tear gas. During the first year of the Intifada, the total number of casualties in the camps from such bombing totalled 16.

Intra-communal violence

Between 1988 and 1992, intra-Palestinian violence claimed the lives of nearly 1,000. By June 1990, according to Benny Morris, "he Intifada seemed to have lost direction. A symptom of the PLO's frustration was the great increase in the killing of suspected collaborators." Roughly 18,000 Palestinians, compromised by Israeli intelligence, are said to have give information to the other side. Collaborators were threatened with death or ostracism unless they desisted, and if their collaboration with the Occupying Power continued, were executed by special troops such as the "Black Panthers" and "Red Eagles". An estimated 771 (according to Associated Press) to 942 (according to the IDF) Palestinians were executed on suspicion of collaboration during the span of the Intifada.

Other notable events

On 16 April 1988, a leader of the PLO, Khalil al-Wazir, nom de guerre Abu Jihad or 'Father of the Struggle', was assassinated in Tunis by an Israeli commando squad. Israel claimed he was the 'remote-control "main organizer" of the revolt', and perhaps believed that his death would break the back of the intifada. During the mass demonstrations and mourning in Gaza that followed, two of the main mosques of Gaza were raided by the IDF and worshippers were beaten and tear-gassed. In total between 11 and 15 Palestinians were killed during the demonstrations and riots in Gaza and West Bank that followed al-Wazir's death. In June of that year, the Arab League agreed to support the intifada financially at the 1988 Arab League summit. The Arab League reaffirmed its financial support in the 1989 summit.

Israeli defense minister Yitzhak Rabin's response was: "We will teach them there is a price for refusing the laws of Israel." When time in prison did not stop the activists, Israel crushed the boycott by imposing heavy fines and seizing and disposing of equipment, furnishings, and goods from local stores, factories and homes.

On 8 October 1990, 22 Palestinians were killed by Israeli police during the Temple Mount riots. This led the Palestinians to adopt more lethal tactics, with three Israeli civilians and one IDF soldier stabbed in Jerusalem and Gaza two weeks later. Incidents of stabbing persisted. The Israeli state apparatus carried out contradictory and conflicting policies that were seen to have injured Israel's own interests, such as the closing of educational establishments (putting more youths onto the streets) and issuing the Shin Bet list of collaborators. Suicide bombings by Palestinian militants started on 16 April 1993 with the Mehola Junction bombing, carried at the end of the Intifada.

United Nations

The large number of Palestinian casualties provoked international condemnation. In subsequent resolutions, including 607 and 608, the Security Council demanded Israel cease deportations of Palestinians. In November 1988, Israel was condemned by a large majority of the UN General Assembly for its actions against the intifada. The resolution was repeated in the following years.

Failing Security Council

On 17 February 1989, the UN Security Council unanimously but for US condemned Israel for disregarding Security Council resolutions, as well as for not complying with the fourth Geneva Convention. The United States, put a veto on a draft resolution which would have strongly deplored it. On 9 June, the US again put a veto on a resolution. On 7 November, the US vetoed a third draft resolution, condemning alleged Israeli violations of human rights

On 14 October 1990, Israel openly declared that it would not abide Security Council Resolution 672 and refused to receive a delegation of the Secretary-General, which would investigate Israeli violence. The following Resolution 673 made little impression and Israel kept on obstructing UN investigations.

Outcomes

The Intifada was recognized as an occasion where the Palestinians acted cohesively and independently of their leadership or assistance of neighbouring Arab states.

The Intifada broke the image of Jerusalem as a united Israeli city. There was unprecedented international coverage, and the Israeli response was criticized in media outlets and international fora.

The success of the Intifada gave Arafat and his followers the confidence they needed to moderate their political programme: At the meeting of the Palestine National Council in Algiers in mid-November 1988, Arafat won a majority for the historic decision to recognise Israel's legitimacy; to accept all the relevant UN resolutions going back to 29 November 1947; and to adopt the principle of a two-state solution.

Jordan severed its residual administrative and financial ties to the West Bank in the face of sweeping popular support for the PLO. The failure of the "Iron Fist" policy, Israel's deteriorating international image, Jordan cutting legal and administrative ties to the West Bank, and the U.S.'s recognition of the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people forced Rabin to seek an end to the violence though negotiation and dialogue with the PLO.

In the diplomatic sphere, the PLO opposed the Gulf War in Iraq. Afterwards, the PLO was isolated diplomatically, with Kuwait and Saudi Arabia cutting off financial support, and 300-400,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from Kuwait before and after the war. The diplomatic process led to the Madrid Conference and the Oslo Accords.

The impact on the Israeli services sector, including the important Israeli tourist industry, was notably negative.

Timeline

See also

References

- ^Note A The word intifada (انتفاضة) is an Arabic word meaning "uprising". Its strict Arabic transliteration is intifāḍah.

- Template:Tr icon 'Saddam olsaydı İsrail'e dersini verirdi' (Zaman)

- Kim Murphy. "Israel and PLO, in Historic Bid for Peace, Agree to Mutual Recognition," Los Angeles Times, 10 September 1993.

- ^ B'Tselem Statistics; Fatalities in the first Intifada.

- Israel, the Occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, and the Palestinian Authority Territories, Human Rights Watch Vol.13, No.4 December 2001

- Lockman; Beinin (1989), p. 5.

- ^ Nami Nasrallah, 'The First and Second Palestinian intifadas,' in David Newman, Joel Peters (eds.) Routledge Handbook on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Routledge, 2013, pp.56–67, p.56.

- Edward Said (1989). Intifada: The Palestinian Uprising Against Israeli Occupation. South End Press. pp. 5–22.

- Berman 2011, p. 41.

- Michail Omer-Man The accident that sparked an Intifada, 12/04/2011

- David McDowall,Palestine and Israel: The Uprising and Beyond, University of California Press, 1989 p.1

- Ruth Margolies Beitler, The Path to Mass Rebellion: An Analysis of Two Intifadas, Lexington Books, 2004 p.xi.

- BBC: A History of Conflict

- Walid Salem, 'Human Security from Below: Palestinian Citizens Protection Strategies, 1988–2005 ,' in Monica den Boer, Jaap de Wilde (eds.), The Viability of Human Security,Amsterdam University Press, 2008 pp.179–201 p.190.

- Mient Jan Faber, Mary Kaldor, ‘The deterioration of human security in Palestine,’ in Mary Martin, Mary Kaldor (eds.) The European Union and Human Security: External Interventions and Missions, Routledge, 2009 pp.95-111.

- 'Intifada,' in David Seddon, (ed.)A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East, Taylor & Francis 2004, p.284.

- Human Rights Watch, Israel, the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and the Palestinian Authority Territories, November, 2001. Vol. 13, No. 4(E), p.49

- ^ Amitabh Pal, "Islam" Means Peace: Understanding the Muslim Principle of Nonviolence Today, ABC-CLIO, 2011 p.191.

- Lockman; Beinin (1989), p.

- Ackerman; DuVall (2000), p 401.

- Robinson, Glenn E. "The Palestinians." The Contemporary Middle East, Third Edition. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2013. 126-127.

- Helena Cobban, 'The PLO and the Intifada', in Robert Owen Freedman, (ed.) The Intifada: its impact on Israel, the Arab World, and the superpowers, University Press of Florida, 1991 pp.70-106, pp.94-5.'must be considered as an essential part of the backdrop against which the intifada germinated'.(p.95)

- Helena Cobban, 'The PLO and the Intifada', p.94. In the immediate aftermath of the 6 Day War in 1967, some 15,000 Gazans had been deported to Egypt. A further 1,150 were deported between September 1967 and May 1978. This pattern was drastically curtailed by the Likud governments under Menachem Begin between 1978-1984.

- Morris, Benny (2001). Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001. Vintage. p. 567. ISBN 0679744754.

- Lockman; Beinin (1989), p. 32.

- ^ Neff, Donald. "The Intifada Erupts, Forcing Israel to Recognize Palestinians". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. December. 1997: 81–83. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- M. B. Qumsiyeh Popular Resistance in Palestine; A History of Hope and Empowerment, Pluto Press; New York 2011.pp. 135

- Shay (2005), p. 74.

- Oren, Amir (18 October 2006). "Secrets of the Ya-Ya brotherhood". Haaretz. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- Vitullo, p.44 The first incident involved two men, one a well-known Gaza businessman, at a roadblock. The second occurred in a residential raid, where subsequently a small cache of weapons were found in the cars of four men. A general riot took place, and in response Israel arrested and ordered the deportation of Shaykh 'Abd al-'Aziz Awad, who was held responsible for the growth of popular support for Islamic Jihad, on 15 November.

- Vitullo, pp45-6. An Israeli schoolteacher was arrested for the incident after a ballistics test was undertaken, but an Israel judge released him after a week, for lack of evidence. Witnesses said she had been throwing stones.

- Shalev (1991), p. 33.

- Nassar; Heacock (1990), p. 31.

- ^ Lockman; Beinin (1989), p. 39.

- MERIP Palestine, Israel and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, A Primer

- "What amazed this writer . .was the interesting departure from the norms of the past. Palestinians in the Occupied Territories were continuously insisting that they would not resort to arms. Any escalation in the use of violence on their part would be as a last resort, for defensive purposes only", Souad Dajani, cited Pearlman, Violence, Nonviolence, and the Palestinian National Movement, p.106

- ^ Jean-Pierre Filiu,Gaza: A History, Oxford University Press p.206.

- éPearlman, ibid. p.107.

- Pearlman, p.112.

- Walid Salem p.189

- Mark Tessler, A History of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,Indiana University Press, 1994 p.677.

- Vitullo p.46.

- Ruth Margolies Beitler,The path to mass rebellion: an analysis of two intifadas, Lexington Books, 2004 p.xiii.

- Vitullo, p.46:'No one cooperated with military interrogators, who arrested suspects and instituted a curfew on the area.'

- Beitler,The path to mass rebellion, p.116 n.75.

- Tessler, A History of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, pp.677-8.

- Vitullo, p.46. writes 20 year old man.

- ^ 'Intifada,' in David Seddon,(ed.)A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East,p.284.

- Vitullo, p.47

- Shlaim (2000), pp. 450–1.

- Pearlman, p.115.

- Cite error: The named reference

Croninwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

DAMHwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - WRMEA Donald Neff The Intifada Erupts, Forcing Israel to Recognize Palestinians

- Sumantra Bose, Contested Lands: Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, Bosnia, Cyprus, and Sri Lanka, Harvard University Press, 2007 p.243

- Beitler,The path to mass rebellion: , p.120

- Vitullo pp.51-2,

- "Collaborators, One Year Al-Aqsa Intifada Fact Sheets And Figures". One Year Al-Aqsa Intifada Fact Sheets And Figures. The Palestinian Human Rights Monitoring Group. Archived from the original on 6 June 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 15 (help) - Morris (1999), p. 612.

- Sergio Catignani, Israeli Counter-Insurgency and the Intifadas: Dilemmas of a Conventional Army, Routledge, 2008 pp.81-84.

- Anita Vitullo, pp.50-1

- UN (31 July 1991). "THE QUESTION OF PALESTINE 1979-1990". United Nations. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Sela, Avraham. "Arab Summit Conferences." The Continuum Political Encyclopedia of the Middle East. Ed. Sela. New York: Continuum, 2002. pp. 158-160

- Sosebee, Stephen J. "The Passing of Yitzhak Rabin, Whose 'Iron Fist' Fueled the Intifada" The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. 31 October 1990. Vol. IX #5, pg. 9

- Aburish, Said K. (1998). Arafat: From Defender to Dictator. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing pp.201-228 ISBN 978-1-58234-049-4

- Beitler, The path to mass rebellion, p.128.

- Nassar; Heacock (1990), p. 115.

- Jeffrey Ivan Victoroff (2006). Tangled Roots: Social and Psychological Factors in the Genesis of Terrorism. IOS Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-58603-670-6.

- ^ UNGA, Resolution "43/21. The uprising (intifadah) of the Palestinian people". 3 November 1988 (doc.nr. A/RES/43/21).

- Resolution 44/2 of 06.10.89; Resolution 45/69 of 06.12.90; Resolution 46/76 of 11.12.91

- Yearbook of the United Nations 1989, Chapter IV, Middle East. 31 December 1989.

- Division for Palestinian Rights (DPR), The question of Palestine 1979-1990, Chapter II, section E. The intifadah and the need to ensure the protection of the Palestinians living under Israeli occupation. 31 July 1991.

- ^ McDowall (1989), p.

- Nassar; Heacock (1990), p. 1.

- Eitan Alimi (9 January 2007). Israeli Politics and the First Palestinian Intifada: Political Opportunities, Framing Processes and Contentious Politics. Taylor & Francis. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-203-96126-1.

- Shlaim (2000), p. 455.

- Shlaim (2000), p. 466.

- Pearlman, p.113

- Shlaim (2000), pp. 455–7.

- Foreign Policy Research Institute Yitzhak Rabin: An Appreciation By Harvey Sicherman

- Roberts; Garton Ash (2009) p. 37.

- Noga Collins-kreiner, Nurit Kliot, Yoel Mansfeld, Keren Sagi (2006) Christian Tourism to the Holy Land: Pilgrimage During Security Crisis Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7546-4703-4 and ISBN 978-0-7546-4703-4

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Peter; DuVall, Jack (2000). A Force More Powerful: A Century of Nonviolent Conflict. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-24050-3.

- Alimi, Eitan Y. (2006). Israeli Politics and the First Palestinian Intifada (2007 hardback ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-38560-2.

- Aronson, Geoffrey (1990). Israel, Palestinians, and the Intifada: Creating Facts on the West Bank. London: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0336-3.

- Berman, Eli (2011). Radical, Religious, and Violent: The New Economics of Terrorism. MIT Press. p. 314. ISBN 0262258005.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Finkelstein, Norman (1996). The Rise and Fall of Palestine: A Personal Account of the Intifada Years. Minnesota: University Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-2858-2.

- Hiltermann, Joost R. (1991). Behind the Intifada: Labor and Women's Movements in the Occupied Territories (1993 reprint ed.). Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07869-4.

- King, Mary Elizabeth (2007). A Quiet Revolution: The First Palestinian Intifada and Nonviolent Resistance. New York: Nation Books. ISBN 978-1-56025-802-5.

- Lockman, Zachary; Beinin, Joel, eds. (1989). Intifada: The Palestinian Uprising Against Israeli Occupation. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-363-9.

- McDowall, David (1989). Palestine and Israel: The Uprising and Beyond. California: University Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06902-2.

- Morris, Benny (1999). Righteous Victims: a History of the Zionist-Arab conflict, 1881-1999. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-74475-7.

- Nassar, Jamal Raji; Heacock, Roger, eds. (1990). Intifada: Palestine at the Crossroads. New York: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-93411-X.

- Peretz, Don (1990). Intifada: The Palestinian Uprising. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-0860-9.

- Rigby, Andrew (1991). Living the Intifada. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-040-5., out-of-print, now downloadable at civilresistance.info

- Roberts, Adam; Garton Ash, Timothy, eds. (2009). Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955201-6.

- Shay, Shaul (2005). The Axis of Evil: Iran, Hizballah, and the Palestinian Terror. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0255-2.

- Schiff, Ze'ev; Ya'ari, Ehud (1989). Intifada: The Palestinian Uprising: Israel's Third Front. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-67530-1.

- Shalev, Aryeh (1991). The Intifada: Causes and Effects. Jerusalem: Jerusalem Post & Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-8303-3.

- Shlaim, Avi (2000). The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-028870-4.

External links

- Jewish Virtual Library

- The Intifada in Palestine:Introduction (www.intifada.com)

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 605

- Palestinian Arab "collaborators" (Guardian, UK)

- The Future of a Rebellion - Palestine An anaysis of the 1980s intifada revolt of Palestinian youth. on libcom.org

- U.S. Involvement with Palestine's Rebellions from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Israel's Post-Soviet Expansion from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

| Arab–Israeli conflict | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Wars and conflicts involving Israel | |

|---|---|

|