| Revision as of 21:17, 10 November 2004 editFys (talk | contribs)14,706 editsm →The counties: Hampshire - Southamptonshire← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:34, 10 November 2004 edit undoSam Korn (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users22,849 editsm Misplaced Pages:WikiProject Wiki Syntax|Please help out by clicking here to fix someone else's Wiki syntax]]Next edit → | ||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

| ==Traditional subdivisions== | ==Traditional subdivisions== | ||

| ] county had three major subdivisions known as the ]s of ]: | ] county had three major subdivisions known as the ]s of ]: | ||

| <br><ol> | <br><ol> | ||

| <li>] | <li>] | ||

Revision as of 22:34, 10 November 2004

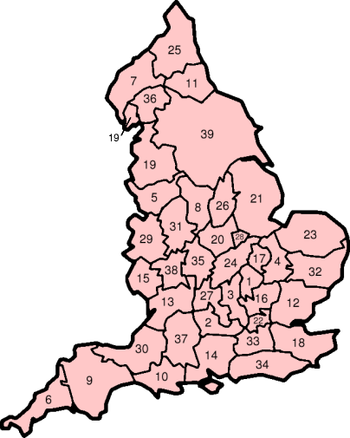

The traditional counties of England are historic subdivisions of the country into around 40 regions. They are also known as the historic counties, or archaically as the ancient or geographical counties.

The traditional counties were used for administrative purposes for hundreds of years, and over time became established as a geographic reference frame. The establishment of the usually accepted set of counties began in the 12th century, although it did not become finalised until the 16th century.

After local government reform in the late 19th century, the traditional counties are no longer in general use for official geographic purposes (in favour of ceremonial counties or administrative counties), but the system in use is partially based on them, and the postal counties often still follow them. (See Counties of England for an overview of how the different types of county compare.)

Various groups exist to promote their continued use, and people engaged in genealogy, family history and local history tend to follow the names used at the time being researched.

The counties

The map omits all exclaves (detached parts) apart from the Furness part of Lancashire south of Cumberland and Westmorland.

Monmouthshire was previously usually considered to be a county of England, but is now generally accepted to be part of Wales.

Counties named after towns were often legally known as the "County of" followed by the name of the town — so, for example, Yorkshire would be referred to as "County of York". The modern usage is to use the suffix "-shire" only for counties named after towns, and for those which would otherwise have only one syllable. In the past, usages such as "Devonshire", "Dorsetshire" and "Somersetshire" was frequent. (There is still a Duke of Devonshire, who is not properly called the Duke of Devon.) Kent was a former kingdom of the Jutes, so "Kentshire" was never used. The name of County Durham is anomalous. The expected form would be "Durhamshire", but it is never used. This is ascribed to that county's history as a county palatine ruled by the Bishop of Durham.

Customary abbreviations exist for many of the counties. In most cases these consist of simple truncation, usually with an "s" at the end, such as "Berks." for Berkshire and "Bucks." for Buckinghamshire. Some abbreviations are not obvious, such as "Salop" for Shropshire, "Oxon" for Oxfordshire or "Hants" and "Northants" for Hampshire and Northamptonshire, respectively.

Origin

The traditional counties accreted over hundreds of years, and have differing ages and origins. In southern England, they were subdivisions of the Kingdom of Wessex, and in many areas represented annexed, previously independent, kingdoms — such as Kent (from the Kingdom of Kent). Only one county on the south coast of England has the suffix "-shire". Hampshire is named after the former town of "Hampton", which is now the city of Southampton.

When Wessex conquered Mercia in the 9th and 10th centuries, it subdivided the area into various shires, which tended to take the name of the main town (the county town) of the county, along with "-shire". Examples of these include Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. In many cases these have since been worn down — for example, Cheshire was originally "Chestershire".

Much of Northumbria was also shired, the best known of these counties being Hallamshire and Cravenshire. The Normans did not use these divisions, and so they are not generally included as traditional counties. After the Norman Conquest in 1066 and the "Harrying of the North", much of the north of the country was left depopulated; at the time of the Domesday Book northern England was covered by Cheshire and Yorkshire. The north-east, land that would later become County Durham and Northumberland, was left unrecorded.

Cumberland, Westmorland, Lancashire, County Durham and Northumberland were established in the 12th century. Lancashire itself can be firmly dated to 1182. Part of the domain of the Bishops of Durham, Hexhamshire was split off and was considered an independent county until 1572.

The border with Wales was not set until the Act of Union 1536 — this remains the modern border. In the Domesday Book the border counties had included parts of what would later become Wales — Monmouth, for example, being included in Herefordshire. The traditional county town of Shropshire, Ludlow, was actually included in Herefordshire in Domesday.

Because of their different origins, the counties have wildly varying sizes. The huge Yorkshire was a successor to the Viking Kingdom of York, and at the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 was considered to include northern Lancashire, Cumberland, and Westmorland. Lincolnshire was the successor to the Kingdom of Lindsey, and took on the territories of Kesteven and Holland when Stamford became the only Danelaw borough to fail to become a county town. A "Stamfordshire" was probably precluded by the existence of Rutland immediately to the west and north of Stamford — leaving it at the very edge of its associated territory. Rutland was an anomalous territory or Soke, associated with Nottinghamshire, that eventually became considered the smallest county.

Traditional subdivisions

county had three major subdivisions known as the ridings of Yorkshire:

]]

Some of the traditional counties had major subdivisions. Of these, the most important were the three ridings of Yorkshire — the East Riding, West Riding and North Riding. Since Yorkshire was so big, its Ridings became established as geographic terms quite apart from their role as administrative divisions. The second largest county, Lincolnshire, was also divided into three historic "Parts" — of Lindsey, Holland and Kesteven. Other divisions included those of Kent into East Kent and West Kent, and of Sussex into East Sussex and West Sussex.

Several counties had liberties or Sokes within them that were administered separately. Cambridgeshire had the Isle of Ely, and Northamptonshire had the Soke of Peterborough. Such divisions were used by such entities as the Quarter Sessions courts and were inherited by the later county council areas.

Smaller subdivisions also existed. Most English counties were traditionally subdivided into hundreds, while Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire and Lincolnshire were divided into wapentakes and Durham, Cumberland and Westmoreland into wards. Kent and Sussex also had an intermediate level between their major subdivisions and their hundreds, known as lathes in Kent and rapes in Sussex. Hundreds or their equivalents were divided into tithings and parishes (the only class of these divisions still used administratively), which in turn were divided into townships and manors.

Authenticity and anomalies

There are at least two sets of county boundaries that have been put forward as the true and genuine traditional borders. The dispute is whether to accept an Act of Parliament in 1844 which purported to modify the counties by abolishing the many enclaves of counties within others, or whether to reject this as mere administrative convenience.

The Act itself says the detached parts shall "be considered" to be part of the county they locally lie in, not that they "shall be". However, this is a matter of disagreement within the traditional counties movement itself, with the Association of British Counties acknowledging the changes in its Gazetteer, and saying that the matter is "debatable".

The traditional counties have (even if the 1844 changes be accepted) many anomalies, and many small exclaves, where a parcel of land would be politically part of one county despite not being physically connected to the rest of the county. The most significant exclaves affected by the 1844 Act were the County Durham exclaves of Islandshire, Bedlingtonshire and Norhamshire, which were incorporated into Northumberland — most of the others were smaller, including even a detached part of the Welsh county of Monmouthshire in Herefordshire, called Welsh Bicknor. This was created as late as 1651.

Exclaves which the 1844 Act did not touch include the part of Derbyshire around Donisthorpe, locally in Leicestershire; and most of the larger exclaves of Worcestershire, including the town of Dudley, which was locally situate in Staffordshire. Additionally the Furness portion of Lancashire remained separated from the rest of Lancashire by a narrow strip of Westmorland — though accessible by the Morecambe Bay tidal flats.

Several towns are historically divided between counties, including Newmarket, Royston, Stamford, Tamworth and Todmorden — in some cases with the county boundary running right up the middle of the high street. In Todmorden, the boundary between Lancashire and Yorkshire is said to run through the middle of the town hall.

Usage

The traditional counties have not formally been abolished, and the Government has made frequent statements to this effect.

When the first county councils were set up in 1888, they covered newly created entities known as administrative counties, and defined in terms of the "ancient and geographic" counties. Direct references in statute to the ancient and geographic counties gradually were removed over the next few decades. The administrative counties differed in many ways — such as the existence of the County of London, and the division of larger counties into several areas (such as Suffolk into East Suffolk and West Suffolk), along with a great many minor boundary changes which accreted over the years.

The ceremonial counties used for Lord-Lieutenancy were changed from a set directly based on the ancient and geographic ones (with exceptions such as the City and Counties of Bristol and London) to an approximation of them based on the administrative counties and the county boroughs. These counties are the ones usually shown on maps of the early to mid 20th century, and largely displaced the traditional counties in general use.

In 1974 a major local government reform took place. This abolished administrative counties and created replacements for them called in the statute "counties". Several counties, such as Cumberland, Herefordshire, Huntingdonshire (actually in 1965), Middlesex (1965) Rutland, Westmorland and Worcestershire vanished from the administrative map, whilst new entities such as Avon, Cleveland, Cumbria and Humberside appeared.

Despite repeated statements by the Government that loyalties were not intended to be affected, many people have accepted (in many places grudgingly) the changes. Significantly, the Ordnance Survey and the Post Office both adopted the changes. Many private organisations have not changed. For example, county cricket is still based on the traditional counties — but this may be due to there being no good reason to change, as opposed to rejection of the changes as legitimate.

The Post Office largely altered its postal counties in accordance with the reform — with the two major exceptions of Greater London and Greater Manchester. Perhaps as a result of this, along with the cumbersomeness of the names and the resentment of encroaching urbanisation, the traditional counties appear not to have fallen out of use for locating the boroughs of Greater Manchester; along with areas of Greater London that were not part of the original administrative County of London. It is quite common for people to speak of Uxbridge, Middlesex or Bromley, Kent, but much less so to speak of Brixton, Surrey or West Ham, Essex. Where metropolitan counties were given more generic names, such as Merseyside or Tyne and Wear, the new counties appear to have been adopted. However, since 2000 the Royal Mail have removed its postal counties from the authoritative Postal Address File database, creating a separate database which now also lists the traditional counties for every address in the UK.

There was particular distress in parts of Yorkshire that were administratively incorporated into Cumbria, Lancashire, Greater Manchester, Humberside, Cleveland and County Durham. Some of these areas have been since returned for ceremonial purposes.

Counties and urban areas

Apart from historic divisions such as Newmarket, Stamford and Tamworth, there are a great number of towns which have expanded (in some cases across a river) into a neighbouring county. These include such towns and cities as Banbury, Birmingham, Bristol, Burton-on-Trent, Great Yarmouth, Leighton Buzzard, London, Manchester, Market Harborough, Peterborough, Reading, Redditch, St Neots, Swadlincote, Tadley and Wisbech.

Although Oxford is on the River Thames, historically the border between Oxfordshire and Berkshire, the traditional border there makes a detour to include Oxford west of the river within Oxfordshire.

The built-up areas of conurbations tend to cross traditional county boundaries freely. Examples here include Bournemouth/Poole (Dorset and Hampshire), Manchester metropolitan area (Cheshire and Lancashire), Merseyside (Cheshire and Lancashire), Teesside (Yorkshire and County Durham), Tyneside (County Durham and Northumberland) and Birmingham metropolitan area (Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire).

Greater London itself straddles five traditional counties — Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent, Middlesex, Surrey — and the London urban area sprawls into Buckinghamshire and Berkshire.

The traditional counties movement

The traditional counties movement consists of a national organisation, the Association of British Counties, along with various regional affiliates. The broad objectives of the movement include

- to replace the ceremonial counties with the traditional counties

- to re-establish the pre-1974 terminology of "administrative counties" in the law, rather than the post-1974 terminology of "counties"

- to get the Ordnance Survey and other map suppliers to determine and mark the traditional county boundaries

- to, in some places, restore traditional counties as administrative counties

Successive governments have generally been quite happy to issue statements saying that the traditional counties still exist, but have been reluctant to pursue these changes. Political parties to have included support for traditional counties in their manifestos include the English Democrats Party and the United Kingdom Independence Party — neither of which has ever had any MPs elected.

In the 1990s the movement enjoyed its greatest success when Rutland became independent of Leicestershire and Hereford and Worcester split to become a unitary authority and shire county respectively — as part of a general local government reform which led to the establishment of many other unitaries. However, the campaign for Huntingdonshire, currently administered as a district of Cambridgeshire, to gain similar status, failed. Additionally, the administrative counties of Avon, Cleveland and Humberside were abolished, and the traditional borders restored for ceremonial purposes.

Recent activities undertaken have included lobbying the Boundary Committee regarding the proposed local government reform in the north of England. Suggestions put forward have included basing the names or the borders of the new authorities on traditional counties. Both of these suggestions have been rejected, though the Committee noted a strong level of support in some areas.

See also

- Subdivisions of England

- Home Counties

- Traditional counties of Wales

- Traditional counties of Scotland

External links

- Named map of the counties of England and Wales - a map rejecting the 1844 changes

- Family history links to traditional counties of England

- Family history links to traditional counties of Wales