| Revision as of 23:47, 3 July 2019 editIamNotU (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers18,370 edits Reverted 1 edit by Jazz1972 (talk): Per rationale and talk page consensus at Talk:Cypriot intercommunal violence#Title and scope of the article, and original research (TW)Tag: Undo← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:31, 4 July 2019 edit undoJazz1972 (talk | contribs)228 edits Rv vandalism, you are removing important well sourced information that came after a consencus from all sides. You do not have the concencus. Is only you and Cinadon that were discussing in the talk page, both belonging on the turkish side.Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Violence between ethnic communities in Cyprus}} | {{short description|Violence between ethnic communities in Cyprus}} | ||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |image = | |||

| |caption = | |||

| |conflict = Cyprus crisis | |||

| |partof = the ] | |||

| |date = 1955–1964 | |||

| |place = ] | |||

| |casus = Constitutional breakdown | |||

| |result = Greek Cypriot military and political victory<ref>{{cite book|first1=Evanthis|last1=Hatzivassiliou|title=Greece and the Cold War: Front Line State, 1952-1967|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Dyl9AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA161|publisher=Routledge|page=161|date=27 September 2006|isbn=9781134154883|via=Google Books}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first1=Farid|last1=Mirbagheri|title=Cyprus and International Peacemaking 1964-1986|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Znp9AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA54|publisher=Routledge|page=54|date=1 May 2014|isbn=9781136677526|via=Google Books}}</ref>{{failed verification|date=January 2019|reason=Reference is about fighting in 1967.}}<ref>{{cite book|first1=Dan|last1=Landis|first2=Rosita D.|last2=Albert|title=Handbook of Ethnic Conflict: International Perspectives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-kmTe1XVcW4C&pg=PA305|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|page=305|date=14 February 2012|isbn=9781461404484|via=Google Books}}</ref>{{failed verification|date=January 2019|reason=Reference is about fighting in 1967.}}<ref>{{cite book|first1=Nicos|last1=Trimikliniotis|first2=Umut|last2=Bozkurt|title=Beyond a Divided Cyprus: A State and Society in Transformation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zS_HAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA75|publisher=Springer|page=75|date=26 November 2012|isbn=9781137100801|via=Google Books}}</ref> | |||

| * Outbreak of intercommunal clashes (1958). | |||

| * Constitutional breakdown between ] and ]. | |||

| * Creation of ] in 1964.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unficyp/background.shtml |title=UNFICYP Background - United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus |publisher=Un.org |date= |accessdate=2017-03-29}}</ref> | |||

| * ] founded "general committee" and announced that their rights in ] are violated by ].<ref name=kibrisevi> '''(Turkish)''', Kıbrıs Evi</ref> | |||

| * ] recognizes the Greek Cypriot-led government of Archbishop ] as the sole legitimate authority in the Republic of Cyprus (Resolution 186).<ref></ref> | |||

| |combatant1= {{flagicon image|Flag of Greece (1822-1978).svg|size=22px}} ] (1955–1959)<hr/>] ] (1963–1967)<br />{{flagicon image|Flag of Greece (1822-1978).svg|size=22px}} ] | |||

| |combatant2= {{flagicon|Turkey}} ]<br/>{{flag|Turkey}} <small>(])</small> | |||

| |commander1 = ] | |||

| |commander2 = ] | |||

| |strength1 = | |||

| |strength2 = | |||

| |casualties1 = | |||

| 56 dead (June–August 1958)<ref name="Empire page 893">Human Rights and the End of Empire: Britain and the Genesis of the European, Alfred William Brian Simpson, page 893,</ref> | |||

| 174 dead (1963–64)<ref name=oberling120/> | |||

| '''Total 230+''' | |||

| |casualties2 = | |||

| 53 dead (June–August 1958)<ref name="Empire page 893"/> | |||

| 364 dead (1963–64)<ref name=oberling120/> | |||

| '''Total 417+''' | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Cyprus dispute}} | {{Campaignbox Cyprus dispute}} | ||

Revision as of 17:31, 4 July 2019

Violence between ethnic communities in Cyprus| Cyprus crisis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cyprus dispute | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Georgios Grivas | Rauf Denktaş | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

56 dead (June–August 1958) 174 dead (1963–64) Total 230+ |

53 dead (June–August 1958) 364 dead (1963–64) Total 417+ | ||||||

| Cyprus problem | |

|---|---|

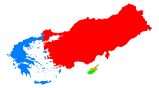

Several distinct periods of Cypriot intercommunal violence involving the two main ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, marked mid-20th century Cyprus. These included the Cyprus Emergency of 1955–59 during British rule, the post-independence Cyprus crisis of 1963–64, and the Cyprus crisis of 1967. Hostilities culminated in the 1974 de facto division of the island along the Green Line following the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. The region has been relatively peaceful since then, but the Cyprus dispute has continued, with various attempts to solve it diplomatically having been generally unsuccessful.

Background

Main article: Cyprus under the Ottoman EmpireTurks made up a significant portion of the population of the island and had ruled the island for several hundred years prior to leasing the island to the British and the subsequent British annexing of the island in 1914.

In 1914, after the Ottoman Empire joined World War I on the side of the Central Powers, the island was annexed by the United Kingdom. Soon afterward, in 1915, the UK offered the island to Greece ruled by King Constantine I of Greece on condition that Greece joins the war on the side of the British. Although the offer was supported by the liberal ex Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, it was rejected by the King, and his prime Minister Zaimis, who wished to keep Greece out of the war. The wife of the King, Sophia of Prussia, was German.

After the foundation of the Republic of Turkey, in 1923, the new Turkish government formally recognized Britain's sovereignty over Cyprus. Greek Cypriots believed it was their natural and historic right to unite the island with Greece (enosis), as many of the Aegean and Ionian islands had done following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

Enosis and Taksim

The repeated rejections by the British of Greek Cypriot demands for enosis led to armed resistance organized by a group known as the National Organization of Cypriot Struggle, or EOKA. EOKA, led by the Greek-Cypriot commander George Grivas, systematically targeted British colonial authorities. One of the effects of the EOKA campaign was to alter the Turkish position from demanding full reincorporation into Turkey to a demand for taksim (partition). The fact that the Turks were a minority was, according to Nihat Erim, to be addressed by the transfer of thousands of Turks from mainland Turkey so that the Greek Cypriots would cease to be the majority. When Erim visited Cyprus as the Turkish representative, he was advised by the then British Governor John Harding that Turkey should send educated Turks to settle in Cyprus.

Turkey actively promoted the idea that on the island of Cyprus two distinctive communities existed, and sidestepped its former claim that “the people of Cyprus were all Turkish subjects”. In doing so, Turkey’s aim to have self-determination of two to-be equal communities in effect led to de jure partition of the island. This could be justified to the international community against the will of the majority Greek population of the island. Dr. Fazil Küçük in 1954 had already proposed Cyprus be divided in two at the 35° parallel.

Crisis of 1955–1959

Main article: Cyprus EmergencyThe British started recruiting Turkish Cypriots into the police force that patrolled Cyprus to fight the EOKA. EOKA targeted colonial authorities, including police, but Georgios Grivas, the leader of EOKA, did not initially wish to open up a new front by fighting Turkish Cypriots and reassured them that EOKA would not harm their people. In 1956, some Turkish Cypriot policemen were killed by EOKA members and this provoked some intercommunal violence in the spring and summer, but these attacks on policemen were not motivated by the fact that they were Turkish Cypriots. However, in January 1957, Grivas changed his policy as his forces in the mountains became increasingly pressured by the British forces. In order to divert the attention of the British forces, EOKA members started to target Turkish Cypriot policemen intentionally in the towns, so that Turkish Cypriots would riot against the Greek Cypriots and the security forces would have to be diverted to the towns to restore order. The killing of a Turkish Cypriot policeman on 19 January, when a power station was bombed, and the injury of three others, provoked three days of intercommunal violence in Nicosia. The two communities targeted each other in reprisals, at least one Greek Cypriot was killed and the army was deployed in the streets. Greek Cypriot stores were burned and their neighborhoods attacked. Following the events, the Greek Cypriot leadership spread the propaganda that the riots had merely been an act of Turkish Cypriot aggression. Such events created chaos and drove the communities apart both in Cyprus and in Turkey.

On 22 October 1957 Sir Hugh Mackintosh Foot replaced Sir John Harding as the British Governor of Cyprus. Foot suggested five to seven years of self-government before any final decision. His plan rejected both enosis and taksim. The Turkish Cypriot response to this plan was a series of anti-British demonstrations in Nicosia on 27 and 28 January 1958 rejecting the proposed plan because the plan did not include partition. The British then withdrew the plan.

By 1958 signs of dissatisfaction with the British increased on both sides, with Turkish Cypriots now forming Volkan, later known as the Turkish Resistance Organization paramilitary group to promote partition and the annexation of Cyprus to Turkey as dictated by the Menderes plan.

On 27 January 1958 British soldiers opened fire against a crowd of Turkish Cypriot rioters. The events continued until the next day.

In June 1958 the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was expected to propose a plan to resolve the Cyprus issue. In light of the new development the Turks rioted in Nicosia to promote the idea that Greek and Turkish Cypriots could not live together and therefore any plan that did not include partition would not be viable. This violence was soon followed by bombing, Greek Cypriot deaths and looting of Greek Cypriot-owned stores and houses. Greek and Turkish Cypriots started to flee mixed population villages where they were a minority in search of safety. This was effectively the beginning of segregation of the two communities. On 7 June 1958 a bomb exploded at the entrance of the Turkish Embassy in Cyprus. Following the bombing Turkish Cypriots looted Greek Cypriot properties. On June 26, 1984 the Turkish Cypriot leader, Rauf Denktaş, admitted on British channel ITV that the bomb was placed by the Turks themselves in order to create tension. On January 9, 1995 Rauf Denktaş repeated his claim to the famous Turkish newspaper Milliyet in Turkey.

The crisis reached a climax on June 12, 1958 when eight Greeks, out of an armed group of thirty five arrested by soldiers of the Royal Horse Guards on suspicion of preparing an attack on the Turkish quarter of Skylloura, were killed in a suspected attack by Turkish Cypriot locals, near the village of Geunyeli having being ordered to walk back to their village of Kondemenos.

The Republic of Cyprus

Right after the EOKA campaign began the British government successfully began to turn the Cyprus issue from a British colonial problem into a Greek-Turkish issue. British diplomacy exerted back-stage influence on the Adnan Menderes government, with the aim of making Turkey active in Cyprus. For the British the attempt had a twofold objective. On one hand the EOKA campaign would be silenced as quickly as possible, on the other hand Turkish Cypriots would not side with Greek Cypriots against the British colonial claims over the island and the island would remain under the British. The Turkish Cypriot leadership at the time, visited Menderes to discuss the Cyprus issue. When asked how the Turkish Cypriots should respond to the Greek Cypriot claim of enosis Menderes replied: "You should go to the British foreign minister and request the status quo be prolonged, Cyprus to remain as a British colony.” Later when the Turkish Cypriots visited the British minister of foreign affairs and requested that Cyprus remain a colony, the Minister replied: "You should not be asking for colonialism at this day and age, you should be asking for Cyprus be returned to Turkey, its former owner".

As Turkish Cypriots began to look to Turkey for protection, it soon became apparent to Greek Cypriots that enosis was extremely unlikely. Greek Cypriot leader Archbishop Makarios III now set independence for the island as his objective.

Britain resolved to solve the dispute by creating an independent Cypriot state. In 1959 all involved parties signed the Zurich agreements: Britain, Turkey, Greece, and the Greek and Turkish Cypriot leaders, Makarios and Dr. Fazil Kucuk respectively. The new constitution drew heavily on the ethnic composition of the island. The President would be a Greek Cypriot and the Vice-President a Turkish Cypriot with an equal veto. The contribution to the public service would be set at a ratio of 70:30, and the Supreme Court would consist of an equal number of judges from both communities plus an independent judge who was not Greek, Turkish or British. The Zurich accords were supplemented by a number of treaties. The Treaty of Guarantee stated that secession or union with any state was forbidden, and that Greece, Turkey and Britain would be given guarantor status to intervene should this be violated. The Treaty of Alliance allowed for two small Greek and Turkish military contingents to be stationed on the island whilst the Treaty of Establishment gave Britain sovereignty over two bases in Akrotiri and Dhekelia.

On August 15, 1960, the Republic of Cyprus was proclaimed.

The new constitution brought dissatisfaction to Greek Cypriots that felt that it was highly unjust for them, for historical, demographic and contributional reasons. While 80% of the island were Greek Cypriots and Greek Cypriots were the vast majority and indigenous people of the island for thousands of years, plus contributing to 94% percent of the taxes, the new constitution was giving the 17% of Turkish Cypriots, with a 6% contribution to the taxes, 30% of the government jobs and 40% of the national security jobs.

Crisis of 1963–1964

Proposed constitutional amendments and the Akritas plan

Main articles: 13 Amendments proposed by Makarios III and Akritas planWithin three years tensions between the two communities in administrative affairs began to show. In particular disputes over separate municipalities and taxation created a deadlock in government. A constitutional court ruled in 1963 Makarios had failed to uphold article 173 of the constitution which called for the establishment of separate municipalities for Turkish Cypriots. Makarios subsequently declared his intention to ignore the judgement, resulting in the West German judge resigning from his position. Makarios proposed thirteen amendments to the constitution, which according to the historian Keith Kyle had the effect of resolving most of the issues in the Greek Cypriot favour. Under the proposals, the President and Vice President would lose their veto, the separate municipalities as sought after by the Turkish Cypriots would be abandoned, the need for separate majorities by both communities in passing legislation would be discarded and the civil service contribution would be set at actual population ratios (82:18) instead of the slightly higher figure for Turkish Cypriots.

The intention behind the amendments has long been called into question. The Akritas plan, written in the height of the constitutional dispute by the Greek Cypriot interior minister Polycarpos Georkadjis, called for the removal of undesirable elements of the constitution so as to allow power-sharing to work. The plan envisaged a swift retaliatory attack on Turkish Cypriot strongholds should Turkish Cypriots resort to violence to resist the measures, stating “In the event of a planned or staged Turkish attack, it is imperative to overcome it by force in the shortest possible time, because if we succeed in gaining command of the situation (in one or two days), no outside, intervention would be either justified or possible.” Whether Makarios's proposals were part of the Akritas plan is unclear, however it remains that sentiment towards enosis had not completely disappeared with independence. Makarios described independence as "a step on the road to enosis". Preparations for conflict were not entirely absent from Turkish Cypriots either, with right wing elements still believing taksim (partition) the best safeguard against enosis.

Greek Cypriots however believe the amendments were a necessity stemming from a perceived attempt by Turkish Cypriots to frustrate the working of government. Turkish Cypriots saw it as a means to reduce their status within the state from one of co-founder to that of minority, seeing it as a first step towards enosis. The security situation deteriorated rapidly.

Intercommunal violence

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (February 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

An armed conflict was triggered after December 21, 1963, a period remembered by Turkish Cypriots as Bloody Christmas, when a Greek Cypriot policemen that had been called to help deal with a taxi driver refusing officers already on the scene access to check the identification documents of his customers, took out his gun upon arrival and shot and killed the taxi driver and his partner. Eric Solsten summarized the events as follows: "a Greek Cypriot police patrol, ostensibly checking identification documents, stopped a Turkish Cypriot couple on the edge of the Turkish quarter. A hostile crowd gathered, shots were fired, and two Turkish Cypriots were killed."

In the morning after the shooting, crowds gathered in protest in Northern Nicosia, likely encouraged by the TMT, without incident. On the evening of the 22nd, gunfire broke out, communication lines to the Turkish neighborhoods were cut, and the Greek Cypriot police occupied the nearby airport. On the 23rd, a ceasefire was negotiated, but did not hold. Fighting, including automatic weapons fire, between Greek and Turkish Cypriots and militias increased in Nicosia and Larnaca. A force of Greek Cypriot irregulars led by Nikos Sampson entered the Nicosia suburb of Omorphita and engaged in heavy firing on armed, as well as by some accounts unarmed, Turkish Cypriots. The Omorphita clash has been described by Turkish Cypriots as a massacre, while this view has generally not been acknowledged by Greek Cypriots.

Further ceasefires were arranged between the two sides, but also failed. By Christmas Eve, the 24th, Britain, Greece, and Turkey had joined talks, with all sides calling for a truce. On Christmas day, Turkish fighter jets overflew Nicosia in a show of support. Finally it was agreed to allow a force of 2,700 British soldiers to help enforce a ceasefire. In the next days, a "buffer zone" was created in Nicosia, and a British officer marked a line on a map with green ink, separating the two sides of the city, which was the beginning of the "Green Line". Fighting continued across the island for the next several weeks.

In total 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the violence. 25,000 Turkish Cypriots from 103-109 villages fled and were displaced into enclaves and thousands of Turkish Cypriot houses were ransacked or completely destroyed.

700 Turkish Cypriot hostages, including men, women and children, were taken from the northern suburbs of Nicosia (into Greek-Cypriot houses, at Omorphita north suburb, which in turn became refugees in their own country). Greek historian Ronaldos Katsaunis stated that he was an eye witness to the retaliation murder and communal burial of 32 Turkish Cypriot civilians in 1963 in Famagusta. Contemporary newspapers also reported on the forceful exodus of the Turkish Cypriots from their homes. According to The Times in 1964, threats, shootings and attempts of arson were committed against the Turkish Cypriots to force them out of their homes. The Daily Express wrote that "25,000 Turks have already been forced to leave their homes". The Guardian reported a massacre of Turks at Limassol on 16 February 1964.

Turkey had by now readied its fleet and its fighter jets appeared over Nicosia. Turkey was dissuaded from direct involvement by the creation of a United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) in 1964. Despite the negotiated ceasefire in Nicosia, attacks on the Turkish Cypriot persisted, particularly in Limassol. Concerned about the possibility of a Turkish invasion, Makarios undertook the creation of a Greek Cypriot conscript-based army called the “National Guard”. A general from Greece took charge of the army, whilst a further 20,000 well-equipped officers and men were smuggled from Greece into Cyprus. Turkey threatened to intervene once more, but was prevented by a strongly worded letter from the American President Lyndon B. Johnson, anxious to avoid a conflict between NATO allies Greece and Turkey at the height of the Cold War.

Turkish Cypriots had by now established an important bridgehead at Kokkina, provided with arms, volunteers and materials from Turkey and abroad. Seeing this incursion of foreign weapons and troops as a major threat, the Cypriot government invited George Grivas to return from Greece as commander of the Greek troops on the island and launch a major attack on the bridgehead. Turkey retaliated by dispatching its fighter jets to bomb Greek positions, causing Makarios to threaten an attack on every Turkish Cypriot village on the island if the bombings did not cease. The conflict had now drawn in Greece and Turkey, with both countries amassing troops on their Thracian borders. Efforts at mediation by Dean Acheson, a former U.S. Secretary of State, and UN-appointed mediator Galo Plaza had failed, all the while the division of the two communities becoming more apparent. Greek Cypriot forces were estimated at some 30,000, including the National Guard and the large contingent from Greece. Defending the Turkish Cypriot enclaves was a force of approximately 5,000 irregulars, led by a Turkish colonel, but lacking the equipment and organization of the Greek forces.

The Secretary-General of the United Nations in 1964, U Thant, reported the damage during the conflicts:

- UNFICYP carried out a detailed survey of all damage to properties throughout the island during the disturbances; it shows that in 109 villages, most of them Turkish-Cypriot or mixed villages, 527 houses have been destroyed while 2,000 others have suffered damage from looting.

Crisis of 1967

The situation worsened in 1967, when a military junta overthrew the democratically elected government of Greece, and began applying pressure on Makarios to achieve enosis. Makarios, not wishing to become part of a military dictatorship or trigger a Turkish invasion, began to distance himself from the goal of enosis. This caused tensions with the junta in Greece as well as George Grivas in Cyprus. Grivas's control over the National Guard and Greek contingent was seen as a threat to Makarios's position, who now feared a possible coup. Grivas escalated the conflict when his armed units began patrolling the Turkish Cypriot enclaves of Ayios Theodhoros and Kophinou, and on November 15 engaged in heavy fighting with the Turkish Cypriots.

By the time of his withdrawal 26 Turkish Cypriots had been killed. Turkey replied with an ultimatum demanding that Grivas be removed from the island, that the troops smuggled from Greece in excess of the limits of the Treaty of Alliance be removed, and that the economic blockades on the Turkish Cypriot enclaves be lifted. Grivas resigned his position and 12,000 Greek troops were withdrawn. Makarios now attempted to consolidate his position by reducing the number of National Guard troops, and by creating a paramilitary force loyal to Cypriot independence. In 1968, acknowledging that enosis was now all but impossible, Makarios stated, "A solution by necessity must be sought within the limits of what is feasible which does not always coincide with the limits of what is desirable."

Greek coup

Main article: 1974 Cypriot coup d'étatAfter 1967 tensions between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots subsided. Instead, the main source of tension on the island came from factions within the Greek Cypriot community. Although Makarios had effectively abandoned enosis in favour of an ‘attainable solution’, many others continued to believe that the only legitimate political aspiration for Greek Cypriots was union with Greece. Makarios was branded a traitor to the cause by Grivas and, in 1971, he made a clandestine return to the island.

On his arrival, Grivas began by establishing a nationalist paramilitary group known as the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston B or EOKA-B), drawing comparisons with the EOKA struggle for enosis under the British colonial administration of the 1950s.

The military junta in Athens saw Makarios as an obstacle, and directed funds to Grivas to carry out a number of attacks and to fund a propaganda campaign through the creation of pro-enosis newspapers. Makarios's failure to disband the National Guard, whose officer class was dominated by mainland Greeks, had meant the junta had practical control over the Cypriot military establishment, leaving Makarios isolated and a vulnerable target.

Turkish invasion

Main article: Turkish invasion of CyprusSee also

References

- Hatzivassiliou, Evanthis (27 September 2006). Greece and the Cold War: Front Line State, 1952-1967. Routledge. p. 161. ISBN 9781134154883 – via Google Books.

- Mirbagheri, Farid (1 May 2014). Cyprus and International Peacemaking 1964-1986. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 9781136677526 – via Google Books.

- Landis, Dan; Albert, Rosita D. (14 February 2012). Handbook of Ethnic Conflict: International Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 305. ISBN 9781461404484 – via Google Books.

- Trimikliniotis, Nicos; Bozkurt, Umut (26 November 2012). Beyond a Divided Cyprus: A State and Society in Transformation. Springer. p. 75. ISBN 9781137100801 – via Google Books.

- "UNFICYP Background - United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus". Un.org. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- Kıbrıs'ta Dünden Bugüne Yönetimler (Turkish), Kıbrıs Evi

- Michael Moran, Cyprus: A European Anomaly, Global Political Trends Center, pp. 5-14

- ^ Human Rights and the End of Empire: Britain and the Genesis of the European, Alfred William Brian Simpson, page 893,

- ^ Oberling, Pierre (1982). The road to Bellapais: the Turkish Cypriot exodus to northern Cyprus. Social Science Monographs. p. 120. ISBN 978-0880330008.

- ^ "Cyprus," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. Archived 2009-10-31.

- David French, p. 255

- Camp, Glen D. (1980). "Greek-Turkish Conflict over Cyprus". Political Science Quarterly. 95 (1): 43. doi:10.2307/2149584.

- Copeaux, Etienne, Aedelsa TUR. Taksim Chypre divisee. ISBN 2-915033-07-2

- cyprus-conflict.net

- Dr. Fazil Küçük, 1957. The Cyprus Question: A permanent solution.

- ^ French, David (2015). Fighting EOKA: The British Counter-Insurgency Campaign on Cyprus, 1955-1959. Oxford University Press. pp. 258–9. ISBN 9780191045592.

- ^ Crawshaw, Nancy. The Cyprus revolt : an account of the struggle for union with Greece. London : Boston : G. Allen & Unwin, 1978. ISBN 0-04-940053-3

- Arif Hasan Tahsin. "He Anodos Tou _Denktas Sten Koryphe". January, 2001. ISBN 9963-7738-6-9

- 'Denktash admits Turks initiated Cyprus intercommunal violence': https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1tUGnWqw2M

- "Denktaş'tan şok açıklama". Milliyet (in Turkish). 9 January 1995.

- The Outbreak of Communal Strife, 1958 Archived January 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, London.

- Anthony Eden, 2005. Memoirs, Full Circle, Cassell, London 1960, p.400.

- Arif Hasan Tahsin. "He Anodos Tou _Denktas Sten Koryphe". January, 2001. ISBN 9963-7738-6-9 page 38

- David Hannay, 2005. Cyprus the search for a solution. I.B Tauris, p.2

- "Cyprus Critical History Archive: Reconsidering the culture of violence in Cyprus, 1955-64 | What Greeks and Turks contribute to the government revenue". Ccha-ahdr.info. 2012-08-06. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- Stephen, Michael (1987). "Cyprus: Two Nations in One Island". Archived from the original (TXT) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- The Cyprus Conflict Archived 2007-02-17 at the Wayback Machine, The Main Narrative, by Keith Kyle

- The Cyprus Conflict, The Akritas Plan

- David Hannay, 2005. Cyprus the search for a solution. I.B Tauris, p.3

- Ali Carkoglu (1 April 2003). Turkey and the European Union: Domestic Politics, Economic Integration and International Dynamics. Taylor & Francis. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7146-8335-5. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Salomon Ruysdael (1 September 2002). New Trends in Turkish Foreign Affairs: Bridges and Boundaries. iUniverse. pp. 299–. ISBN 978-0-595-24494-2. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Her şey buradan başladı [Everything started here]". Havadis. 21 December 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Eric Solsten, Country Studies, US Library of Congress, retrieved on 25 May 2012.

- ^ Borowiec, Andrew (2000). Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 55–57. ISBN 9780275965334.

- John Terence O'Neill; Nicholas Rees (2005). United Nations Peacekeeping in the Post-Cold War Era. Taylor & Francis. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7146-8489-5.

- Report S/5950 (10 September 1964), page 48, paragraph 180

- "REPORT BY THE SECRETARY-GENERAL ON THE UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN CYPRUS" (PDF). United Nations. 10 September 1964. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

The trade of the Turkish community had considerably declined during the period, due to the existing situation, and unemployment reached a very high level as approximately 25,000 Turkish Cypriots had become refugees.

- Risini, Isabella (2018). The Inter-State Application under the European Convention on Human Rights: Between Collective Enforcement of Human Rights and International Dispute Settlement. BRILL. p. 117. ISBN 9789004357266.

- Smit, Anneke (2012). The Property Rights of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons: Beyond Restitution. Routledge. p. 51.

- "Bir katliam itirafı da Rum tarafından geldi - Dünya Haberleri". Radikal. 2009-01-26. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ""32 Türk'ü gözümün önünde öldürdüler!!!" Rum tarihçi anlatıyor!!!". MedyaFaresi.com. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- The Times 04.01.1964

- Daily Express 28.12.1963

- Michael Stephen (1997). The Cyprus Question. British-Northern Cyprus Parliamentary Group. p. 15.

- BBC On This Day. 1964: Guns fall silent in Cyprus

- Report S/5950 (10 September 1964), page 48, paragraph 180

- Country Studies: Cyprus - Intercommunal Violence Archived 8 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

External links

- Cyprus-Conflict.net An independent and comprehensive website dedicated to the Cyprus conflict, containing a detailed narrative as well as documents, reports and eye-witness accounts.

- Library of Congress Cyprus Country Study Detailed information on Cyprus, covering the various phases of the Cyprus conflict.

| Bilateral relations |  | |

|---|---|---|

| Multilateral relations | ||

| Cyprus dispute | ||

| United Nations | ||

| Other topics | ||

| Africa |  | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Americas | |||

| Asia | |||

| Europe |

| ||

| Disputes | |||

| Missions | |||

| Multilateral | |||

| Related topics | |||

| Cyprus Ministry of Foreign Affairs | |||

| Cyprus problem | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants |

|  | ||||

| Events |

| |||||

| Politics | ||||||

| Organisations | ||||||

| Lawsuits | ||||||

| Peace process | ||||||

| List of modern conflicts in the Middle East | |

|---|---|

| 1910s | |

| 1920s | |

| 1930s | |

| 1940s | |

| 1950s | |

| 1960s | |

| 1970s |

|

| 1980s | |

| 1990s | |

| 2000s | |

| 2010s | |

| 2020s | |

| This list includes World War I and later conflicts (after 1914) of at least 100 fatalities each Prolonged conflicts are listed in the decade when initiated; ongoing conflicts are marked italic, and conflicts with +100,000 killed with bold. | |

- 20th-century conflicts

- 1955 in Cyprus

- 1958 in Cyprus

- 1963 in Cyprus

- 1964 in Cyprus

- Cyprus dispute

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Asia

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Europe

- Civil wars post-1945

- Ethnicity-based civil wars

- Sectarian violence

- Conflicts in 1955

- Conflicts in 1956

- Conflicts in 1957

- Conflicts in 1958

- Conflicts in 1959

- Conflicts in 1960

- Conflicts in 1961

- Conflicts in 1962

- Conflicts in 1963

- Conflicts in 1964