This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Casliber (talk | contribs) at 22:58, 3 November 2007 (ref for Jiangshi in film). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:58, 3 November 2007 by Casliber (talk | contribs) (ref for Jiangshi in film)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)For a closer look at vampires in modern fiction, see vampire literature and vampire films. For the bats that subsist on blood, see vampire bat. For other uses, see Vampire (disambiguation).

Vampires are mythological or folkloric beings that are renowned for subsisting on human blood or lifeforce, but in some cases may prey on animals. Vampire lore stems from ancient psychological and mythological roots; beings with vampiric abilities have been recorded from the earliest cultures and folklore the world over. Though vampires have widely varying characteristics, they are described for the most part as reanimated corpses who feed by draining and consuming the blood of living beings. The term was popularised in the early 18th century and arose from the folklore of southeastern Europe, particularly the Balkans and Greece. Folkloric vampires were depicted as revenants who visited loved ones and caused mischief or deaths in the neighbourhoods they inhabited when they were living. They wore shrouds, did not bear fangs and were often described as bloated and of ruddy or darkened countenance.

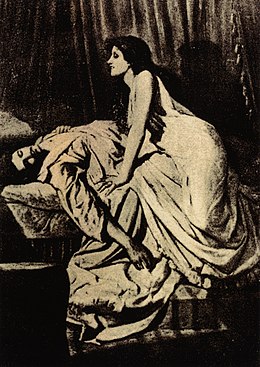

The charismatic and sophisticated vampire of modern fiction was born in 1819 with the publication of The Vampyre (1819) by John Polidori. The wild life of Lord Byron became the model for Polidori's undead protagonist Lord Ruthven after Polidori became Byron's personal physician. The story was highly successful and the most influential vampire work of the early 19th century. However it is the 1897 novel Dracula which is best remembered as the quintessential vampire novel. The success of this book spawned a distinctive vampire genre, still popular in the 21st century. Though books and films of the genre have portrayed vampires with attributes markedly distinct from those of original folkloric vampires, some folkloric traits such as aversion to garlic and vulnerability to staking have been simply incorporated.

Etymology

The word vampire appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1734 as much was appearing in German literature on the subject. After the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz where parts of Serbia and Wallachia came under Austrian control, the Austrian officials noted the local practice of exhuming bodies and "killing vampires". These reports prepared between 1725 and 1732 received widespread publicity. Several theories of the word's origin exist. The English term was derived (possibly via French vampyre) from the German Vampir, in turn thought to be derived in the early 18th century from Serbian вампир/vampir, or Hungarian vámpír. The Serbian and Hungarian forms have parallels in virtually all Slavic languages: Bulgarian вампир (vampir), Czech and Slovak upír, Polish wąpierz and (perhaps East Slavic-influenced) upiór, Russian упырь (upyr'), Belarusian упыр (upyr), Ukrainian упирь (upir'), from Old Russian упирь (upir'). (Note that many of these languages have also borrowed forms such as "vampir/wampir" secondarily from the West). Among the proposed proto-Slavic forms are *ǫpyrь and *ǫpirь. The Slavic word might, like its possible cognate that means "bat" (Czech netopýr, Slovak netopier, Polish nietoperz, Russian нетопырь / netopyr' - a species of bat), contain a Proto-Indo-European root for "to fly".

The first recorded use of the Old Russian form Упирь (Upir') is commonly believed to be in a document dated 6555 (1047 AD). It is a colophon in a manuscript of the Book of Psalms written by a priest who transcribed the book from Glagolitic into Cyrillic for the Novgorodian Prince Vladimir Yaroslavovich. The priest writes that his name is "Upir' Likhyi " (Упирь Лихый), which would mean something like "Wicked Vampire" or "Foul Vampire." This apparently strange name has been cited as an example of surviving paganism and/or of the use of nicknames as personal names. However, in 1982, Swedish Slavicist Anders Sjöberg suggested that "Upir' likhyi" was in fact an Old Russian transcription and/or translation of the name of Öpir Ofeigr, a well-known Swedish rune carver. Sjöberg argued that Öpir could possibly have lived in Novgorod before moving to Sweden, considering the connection between Eastern Scandinavia and Russia at the time. This theory is still controversial, although at least one Swedish historian, Henrik Janson, has expressed support for it. Another early use of the Old Russian word is in the anti-pagan treatise "Word of Saint Grigoriy," dated variously to the 11—13 centuries, where pagan worship of upyri is reported.

Folk beliefs

The notion of vampirism has been in use for millennia; cultures such as the Mesopotamians, Hebrews, Ancient Greeks, and Romans had tales of demons and spirits including the Empusa, Lamia, and Lilitu, who would eat flesh and drink blood; even the devil was considered synonymous with the vampire in earlier times. However, despite the occurrence of vampire-like creatures in these ancient civilizations, the folklore for the entity we know today as the vampire originates almost exclusively from Southeastern Europe. In most cases, vampires are revenants of evil beings, suicide victims or witches, but can also be created by a malevolent spirit possessing a corpse or by being bitten by a vampire itself. The legends of the vampire grew to such a height, that in some areas it caused mass hysteria and even public executions of people believed to be vampires. Although the original lore has been distorted due to new fictional references such as Dracula, there are many ways to destroy a vampire; decapitation, a stake to the heart, incineration and exposure to sunlight are commonly cited.

Description and common attributes

It is difficult to make a single, definitive description of the folkloric vampire though there are several elements common to many European legends. It is usually reported as bloated in appearance and ruddy, purplish or dark in colour, often attributed to drinking blood. Indeed, blood is often seen seeping from the mouth and nose when one is seen in its shroud or coffin and his left eye is often open. Clothing often consisted of the linen shroud they were buried in and teeth, hair and nails may have grown somewhat, though in general fangs were not a feature.

Other attributes may vary greatly from culture to culture; some vampires, such as those found in Transylvanian tales, are gaunt, pale and have long fingernails, while Bulgarian vampires only had one nostril, while Bavarian vampires slept with thumbs crossed and one eye open. Moravian vampires only attacked victims naked and the vampires of Albanian folklore wore high heeled shoes. As stories of vampires spread throughout the globe to the Americas and elsewhere, so did the varied and sometimes bizarre descriptions of them; Mexican vampires have a bare skull instead of a head, Brazilian vampires had furry feet and vampires from the Rocky Mountains only sucked blood with their noses from the victim's ears. Even broad descriptions were implemented, such as having red hair. So from these various descriptions across time, works of literature such as Bram Stoker's Dracula and the influences of historical figures such as Gilles de Rais and Vlad Tepes, the vampire has developed into the stereotype we perceive today; over time, a selection of more common reported attributes from a huge variety of ancient and medieval stories have coalesced to form a contemporary vampire profile as seen in literature and film today.

Creation beliefs

It is commonly accepted in modern cultural depictions that one is likely to become a vampire if bitten by one. However the causes were far more varied in original vampire folklore. In Slavic and also Chinese traditions any corpse which was jumped over by an animal, particularly a dog or cat, would become one of the undead. If a body had a wound which had not been treated with boiling water. And in Russian mythology, vampires were said to have once been witches while they were living, or people who rebelled against the church.

Practices often arose that were intended to prevent a recently deceased loved one turning into an undead revenant. Burying a corpse upside-down was a common prevention method, as well as placing earthly objects, such as scythes or sickles, near the grave to satisfy any demons entering the body or to appease the dead so that it would not wish to arise from its coffin. This method is similar to the ancient Greek practice of placing a obolus in the corpse's mouth so that they may pay their way across the River Styx in the underworld; it has been argued that instead, the obolus was intended to ward off any evil spirits from entering the body and this may have influenced later mythology surrounding the vampire. This Greek tradition was continued on in regard to modern Greek folklore about the vrykolakas, the equivalent of a modern vampire, in which a wax cross and piece of pottery with the inscription "Jesus Christ conquers" were placed on the corpse to prevent the body becoming a vrykolakas. Other methods commonly practised in Europe included severing the tendons at the knees or placing poppy seeds, millet or sand on the ground at the gravesite of a presumed vampire; this was intended to keep the vampire occupied all night by counting the fallen grains. In similar Chinese narratives about vampire-like beings, it is stated that if one of these creatures comes across a sack of rice, he will have to count all of the grains; this is a theme similar to myths recorded on the Indian subcontinent as well as in South American tales of witches and other sorts of evil or mischievous spirits or beings.

Identifying vampires

The rituals behind identifying a vampire were in most cases elaborate, with several methods arising throughout Eastern Europe and other areas where vampire legends became prominent. In some Eastern European instances, the method of finding a vampire's grave involved leading a virgin boy through a graveyard or church grounds on a virgin, black stallion; the tomb which the horse stopped at first was said to be that of the vampire's. Holes appearing in the earth over a grave were taken as a sign of vampirism. Corpses thought to be vampires were generally described as having a healthier appearance than expected, plump and showing little or no signs of decomposition. In some cases, when suspected graves were opened, villagers even described the corpse as having fresh blood from a victim all over its face. Evidence that a vampire was active in a given locality included death of cattle, sheep, relatives or neighbours; folkloric vampires could also make their presence felt by engaging in minor poltergeist-like activity and pressing on people in their sleep.

Protection

A common theme is the use of apotropaics to ward the revenants off, namely mundane or sacred items or things such as garlic, sunlight or holy water. Items vary from region to region; a branch of wild rose is said to harm vampires as well as the hawthorn plant; in Europe, sprinkling mustard seeds on the roof of a house was said to keep vampires away. Other apotropaics include sacred items, for example a crucifix, rosary beads and the aforementioned holy water; vampires are said to be unable to walk on consecrated ground, such as those of churches or temples or cross running water. In Asian legends, vampiric creatures are often warded by holy devices such as Shintō seals. In South American superstition, Aloe vera hung backwards behind or near a door has the same function. Although not regarded as a vampire apotropaic, mirrors have been used to ward off vampires when placed facing outwards on a door; it's a well known myth that vampires do not have a reflection and in some cultures, do not cast shadows either, perhaps to express the vampire's lack of a soul. This attribute, although not universal as the Greek vrykolakas/tympanios was capable of both reflection and shadow, was utilized by Bram Stoker in Dracula and has since remained popular with subsequent authors and filmmakers. In addition to apotropaics, some traditions hold that a vampire cannot enter a house unless invited by the owner, although they only have to be invited once as after this they can come and go as they please without further permission.

Traditional methods of destroying vampires were varied, with staking the most commonly cited method. This was most common in southern slavic cultures. The preferred wood is ash in Russia and the Baltic states, or hawthorn in Serbia, with a record of oak in Silesia. Potential vampires were most often staked though the heart, though the mouth was targetted in Russia and northern Germany, or the stomach in northeastern Serbia. Unlike today's cloaked and suave vampires, the original revenants were described as largely bloated. Thus the act of piercing the skin of the chest was a way of "deflating" the vampire; this is similar to the act of burying sharp objects, such as sickles, in with the corpse, so that they may penetrate the skin if the body bloats sufficiently whilst transforming into a revenant. Decapitation was the preferred method in German and western slavic areas, with the head buried between the feet, behind the buttocks or away from the body. The act of cutting off the head was also seen as a way of hastening the departure of the soul from the body, which in some cultures, was said to linger in the corpse for a prolonged amount of time before dispersing. Other than being decapitated, the vampire's head, body or clothes could be spiked and pinned to the earth to prevent rising. Gypsies drove steel or iron needles into a corpse's heart and placed bits of steel in the mouth, over the eyes, ears and between the fingers at the time of burial. They also placed hawthorn in the corpse's sock or drove a hawthorn stake through the legs. Further measures included pouring boiling water over the grave or complete incineration of the body. In the Balkans a vampire could also be shot or drowned, as well as having the funeral service repeated, or by the sprinkling holy water on the body, or exorcism. In Romania garlic could be placed in the mouth, and as recently as the 19th century, the precaution of shooting a bullet through the coffin was taken. For resistant cases, the body was dismembered and the pieces burned, mixed with water, and administered to family members as a cure. Even a lemon was placed in the mouth of suspected Saxon vampires in Germany.

Vampires are sometimes endowed with special abilities when described in folklore; some are given great strength, while others the ability to transform not only into a bat, as is often depicted in modern cartoons and film, but rather other familiars such as rats, dogs, wolves, spiders and even moths. An attribute shared by the 19th century literary vampires Lord Ruthven and Varney the Vampire was the ability to be healed by moonlight, although no account of this is known in traditional folklore. Though folkloric vampires thought more active at night, they were not generally considered vulnerable to sunlight. This vulnerability has developed with subsequent vampire fiction.

Ancient beliefs

Tales of the undead consuming the blood or flesh of living beings have been found in nearly every culture around the world for many centuries. Today we know these entities predominantly as vampires, but in ancient times, the term vampire didn't exist; blood drinking and such like was referred to as the work of demons or spirits, such as Lilith, Empusa, Lamia and other monsters; vampires and the devil were closely linked in many cultures as well. Modern vampire mythology spread from Eastern Europe, however, early vampiric creatures have been described throughout the world — from Europe to Asia, from the Americas to the Pacific. Almost every nation has associated blood drinking with some kind of revenant or demon. Indeed, some of these legends could have given rise to the Eastern European folklore, though they are not strictly considered vampires by historians when using today's definitions.

Mesopotamia

The Persians were one of the first civilizations thought to have tales of blood-drinking demons; creatures attempting to drink blood from men were depicted on excavated pottery. Ancient Babylonia had tales of the mythical Lilitu, synonymous with Lilith (Hebrew לילית) and her daughters the Lilu from Hebrew demonology who were derived from their Babylonian counterparts. Lilitu was considered as a demon and was often depicted as subsisting on the blood of babies. However, the Jewish Lilu and their mother Lilith, were said to feast on both men and women, as well as newborns. The legend of Lilith was originally included in some traditional Jewish texts, she was considered to be Adam's first wife before Eve according to the medieval folk traditions. In the these texts, Lilith left Adam to become the queen of the demons and much like the Greek striges, would prey on young babies and their mothers at night, as well as males. This practice of blood drinking performed by Lilith was considered exceptionally evil in Jewish tradition due to the Hebrew law which absolutely forbade the eating of human flesh or the drinking of any type of blood. To ward off attacks from Lilith, parents used to hang amulets from their child's cradle. An alternate versions state, the legend of Lilith/Lilitu (And a type of spirit of the same name) originally arose from Sumer, where she was a described as an infertile "beautiful maiden" and was believed to be a harlot and vampire who, once had chosen a lover, would never let him go. Lilitu or the Lilitu spirits were considered to be anthropomorphic bird-footed, wind or night demons and were often described as subsisting on the blood of babies, their mothers, and being highly sexually predatory to men. Other Mesopotamian demons such as Babylonian goddess Lamashtu, (Sumerian Dimme) and Gallu of the Uttuke group are mentioned as having vampiric natures.

Lamashtu, is a historically older image that left an mark on the figure of Lilith. Many incantations against Lamashtu invoke her as a malicious "Daughter of Heaven" or Anu and she is often depicted as a terrifying blood-sucking creature, with a lion's head and the body of a donkey. Akin to Lilitu, Lamashtu's primary victim's consisted of the newborn and their mothers. She was said to watch pregnant women vigilantly, particularly when they went into labor. Afterwards, she snatched the newborn from the mother to drink it's blood and eat it's flesh. In the Labartu texts she is described; "Wherever she comes, wherever she appears, she brings evil and destruction. Men, beasts, trees, rivers, roads, buildings, she brings harm to them all. A flesh-eating, bloodsucking monster is she." Similary, Gallu was a demon closely associated with Lilith. Occasionally, Gallu, like that of Uttuku, is used as a general term for demons, and these are "evil Uttuke" or "evil Galli". One incantation tells of them as spirits that threaten every house, rage at people, eat their flesh, and as they let their blood flow like rain, they never stop drinking blood. In amulet texts, sometimes its Lamashtu, sometimes Lilitu, and at other times its Gallu, who is invoked and conjured. Gallu is inherited in Graeco-Byzantine myth, as Gello, Gylo, or Gyllo and appears as an child stealing and child killing female demon, like that of Lamia and Lilith.

Ancient Egypt

The Ancient Egyptian goddess Sekhmet was associated with bloodlust, death and vampiric behaviour. Possessing the head of a lion, Sekhmet was considered the greatest hunter known to the Egyptians and was originally the warrior goddess of Upper Egypt, who devoured humans and drank blood after battle. In Egyptian mythology Sekhmet was closely related with the warrior goddess Bast, although was often depicted as the fiercer of the two with names such as Lady of Slaughter, Mistress of Dread, Avenger of Wrongs and the Scarlet Lady, references to her bloodlust. She was seen as a special goddess for women and was patron god of menstruation. Usually shown in red to represent blood, Sekhmet was first noted for her bloodlust in an ancient myth about the Nile; to avert excessive flooding during the inundation of the Nile river at the beginning of each year Sekhmet was said to swallow the excess water that overflowed the river's banks. However, the water at this time of the year is laden with sand and silt from upstream, thus giving it a red, blood-like appearance.

A variant on this myth is that Sekhmet only drank the Nile river after being deceived by the sun god Ra. In this version, her bloodlust was not quelled at the end of battle by her devouring of human flesh and blood, so the goddess decided to turn on man to sate her thirst. After nearly destroying all of humanity, Ra tricked her by turning the Nile red like blood so that Sekhmet would drink it. However, the red liquid was not blood, but beer mixed with pomegranate juice, making her so drunk that she gave up slaughter. This association with Sekhmet explains the goddess' depiction as a vampiric being in later mythology, and a festival to reinact this blood drinking was held at the beginning of each year to coincide with the Nile's flood cycle. At the festival, all the alcohol was coloured red in honour of Sekhmet and thousands were recorded as attending the festivities.

Ancient Greece

The Ancient Greeks had several precursors of modern vampires, though none were considered undead; these included the Lamia, Empusa and striges (strix in Ancient Roman mythology). Over time the first two terms became general words to describe witches and demons respectively. Empusa was the daughter of the goddess Hecate and was described as a demonic, bronze-footed creature. She would feast on blood by transforming into a young woman and seducing men as they slept before drinking their blood. Lamia was the daughter of King Belus and secret lover of the Greek god Zeus. However Zeus' wife Hera discovered this infidelity and killed all Lamia's offspring; Lamia swore vengeance and preyed on young children in their beds at night, sucking their blood. Like Lamia, the striges, feasted on children, but also preyed on young men. They were described as having the bodies of crows or birds and were later incorporated into Roman mythology as strix, a kind of nocturnal bird that fed on human flesh and blood. The Romanian vampire breed Strigoï has no direct relation to the Greek striges, but was derived from the Roman term strix, as is the name of the Albanian Shtriga and the Slavic Strzyga, though myths about these creatures are more similar to their Slavic equivalents.

India

In India, tales of vetalas, ghoul-like beings that inhabit corpses, are found in old Sanskrit folklore. A prominent story tells of King Vikramāditya and his nightly quests to capture an elusive vetala. The vetala legends have been compiled in the book Baital Pachisi. The vetala is an undead creature, who like the bat associated with modern day vampirism, hangs upside down on trees found in cremation grounds and cemeteries. Pishacha are other creatures who resemble vampires to an extent. Since Hinduism believes in reincarnation of the soul, it is supposed that leading an unholy or immoral life, sin or suicide, will lead the soul to reincarnate into such evil spirits. This kind of reincarnation does not arise out of birth from a womb, but is achieved directly, and such evil spirits' fate is predetermined as to how they shall achieve liberation from that yoni, and re-enter the world of mortal flesh in the next incarnation.

Medieval and later European folklore

Some myths of vampires arose out of the folk traditions of the Jews in medieval Europe. In fact, it can be speculated that the legend of Lilith may have given rise to the vampire myth. Lilith possesses several characteristics of and in common with that of a vampire; the ability to transform herself into an animal, usually an cat, and she makes attempts to diabolically do harm, often charming her victims into believing that she is benevolent or irresistible, at first. The vampire motif seems to be replaced a bit by Lilith and her daughters, who usually strangle their victims rather than drain the life out of them. However, in the Kabbalah, Lilith retains many attributes found in vampires. A late 17th or early 18th century Kabbalah document was found in one of the Ritman library's copies of Jean de Pauly's translation of the Zohar. The text contains two amulets, one for male ('lazakhar'), the other for female('lanekevah'). The invocations on the amulets mention Adam, Eve, and Lilith, 'Chavah Rishonah', the angels - Sanoy, Sansinoy, Smangeluf, Shmari'el, and Hasdi'el (the merciful). A few lines in Yiddish are shown as dialog between the prophet Elijah and Lilith, in which Lilith has come with a host of demons to kill the mother and take her newborn and 'to drink her blood, suck her bones and eat her flesh'. She precedes to tell Elijah that she will lose power if someone uses her secret names, which she reveals at the end. Other Jewish stories depict vampires in a more traditional way. In "The Kiss of Death", the daughter of the demon king Ashmodai, snatches the breath of a man who has betrayed her, in away strongly reminiscent of a fatal kiss of a vampire. In another rare story found in Sefer Hasidim #1465, an old woman vampire named Astryiah, uses her hair to drain the blood from her victims. A similar tale from the same book describes staking a witch through the heart to ensure she does not come back from the dead to haunt her enemies.

The 12th century English historians and chroniclers Walter Map and William of Newburgh recorded accounts of revenants, though records in English legends of vampiric beings after this date are scant. These tales are similar to the later folklore widely reported from Eastern Europe in the 18th century, and it was from these that the vampire legend entered Germany and England, where it was subsequently embellished and greatly popularised into the modern fictional vampire.

During the 18th century, there was a major vampire scare in Eastern Europe. Even government officials frequently got dragged into the hunting and staking of vampires. The panic began with an outbreak of alleged "vampire" attacks in East Prussia in 1721 and in the Habsburg Monarchy from 1725 to 1734. Two famous vampire cases (which were the first to be officially recorded) involved Peter Plogojowitz and Arnold Paole from Serbia. Plogojowitz was reported to have died at the age of 62, but allegedly returned after his death asking his son for food. When he refused, the son was found dead the following day. Plogojowitz soon returned and attacked some neighbours who died from loss of blood. In the other famous case, Arnold Paole, an ex-soldier turned farmer who allegedly was attacked by a vampire years before, died while haying. After his death, people began to die, and it was widely believed that Paole had returned to prey on the neighbours.

These two incidents were extremely well documented. Government officials examined (and wrote reports of) the cases and the bodies, and books were published afterwards of the Paole case and distributed around Europe. The controversy raged for a generation. The problem was exacerbated by rural epidemics of so-claimed vampire attacks, with locals digging up bodies. Many scholars said vampires did not exist, and attributed reports to premature burial, or rabies. Nonetheless, Dom Augustine Calmet, a well-respected French theologian and scholar, put together a carefully thought out treatise in 1746, which was at least ambiguous concerning the existence of vampires, if not admitting it explicitly. He amassed reports of vampire incidents and numerous readers, including both a critical Voltaire and supportive demonologists, interpreted the treatise as claiming that vampires exist. In his Philosophical Dictionary, Voltaire wrote on the vampires:

These vampires were corpses, who went out of their graves at night to suck the blood of the living, either at their throats or stomachs, after which they returned to their cemeteries. The persons so sucked waned, grew pale, and fell into consumption; while the sucking corpses grew fat, got rosy, and enjoyed an excellent appetite. It was in Poland, Hungary, Silesia, Moravia, Austria, and Lorraine, that the dead made this good cheer.

According to some recent research, and judging from the second edition of the work in 1751, Calmet was actually somewhat skeptical towards the vampire concept as a whole. He did acknowledge that parts of the reports, such as the preservation of corpses, might be true. Whatever his personal convictions were, Calmet's apparent support for vampire belief had considerable influence on other scholars at the time.

Eventually, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria sent her personal physician, Gerhard van Swieten, to investigate. He concluded that vampires do not exist, and the Empress passed laws prohibiting the opening of graves and desecration of bodies. This was the end of the vampire epidemics. By then, though, many knew about vampires, and soon authors would adopt and adapt the concept of vampire, making it known to the general public.

Slavic

The vampire legends of various Slavic peoples do have some common characteristics, but are on the whole rather varied. Some of the more common causes of vampirism include being a magician or an immoral person; suffering an "unnatural" or untimely death such as suicide; excommunication; improper burial rituals; an animal jumping or a bird flying over the corpse or the empty grave (in South Slavic folk belief); and even being born with a caul, teeth or tail, or being conceived on certain days. In southern Russia, people who were known to talk to themselves were believed to be at risk of becoming vampires. Slavic vampires were able to appear as butterflies, echoing an earlier belief of them symbolizing departed souls. Some traditions spoke of "living vampires" or "people with two souls", a kind of witches capable of leaving their body and engaging in harmful and vampiric activity while sleeping. The most famous Serbian vampire was Sava Savanović, famous from a folklore-inspired novel by Milovan Glišić.

One Serbian ritual is as follows; after the deceased was taken out of the house, a nail was driven into the floor beneath the bier, and an egg was broken. Two or three elderly women would come to the grave the evening after the funeral, and stick five hawthorn pegs or old knives into the grave: one at the position of the chest of the deceased, and the other four at the positions of his arms and legs. Alternately, they may surround the grave with a red woolen thread, ignite the thread, and wait until it was burnt up.

By one of the customs intended to protect a village from vampires and diseases, twin brothers yoked twin oxen to a plow, and made a furrow with it around the village.

If a noise was heard during night, suspected to be made by a vampire sneaking around someone's house, it was shouted, "Come tomorrow, and I will give you some salt," or "Go, pal, get some fish, and come back."

South Slavic legends had a number of characteristics that set them apart from the others; a vampire was believed to pass through several distinct stages in its development. The first 40 days were considered decisive for the making of a vampire. It started out as an invisible shadow and then gradually gained strength from the blood it had sucked, forming a (typically also invisible) jelly-like, boneless mass, and eventually building up a human-like body nearly identical to the one the person had had in life. This development allowed the creature to ultimately leave its grave permanently and begin a new life as an ordinary human. The vampire (who was usually male) was also sexually active and could have children, either from his widow or from a new wife. These could become vampires themselves, but could also have a special ability to see and kill vampires, allowing them to become vampire hunters. The same talent was believed to be found in persons born on Saturday.

A special feature of West Slavic beliefs, according to ethnologist E. Levkievskaya, is that they tend to stress that becoming a vampire is determined by fate and can be predicted on the basis of physical traits. In the East Slavic area, the northern regions (i.e. most of Russia) are unique in that their undead, while having many of the features of the vampires of other Slavic peoples, don't drink blood and don't bear a name derived from the common Slavic root for "vampire". Ukrainian and Belarusian legends are more "conventional", although in Ukraine the vampires may sometimes not be described as dead at all, or may be seen as engaging in vampirism long before death. During cholera epidemics in the 19th century, there were cases of people being burned alive by their neighbours on charges of being vampires.

Romanian

| This http://www.darknessembraced.com/ may contain excessive or inappropriate references to self-published sources. Please help improve it by removing references to unreliable sources where they are used inappropriately. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Romanian vampires are called strigoi and classified as living or dead. Live strigoi are living witches with two hearts and/or two souls. They have the ability to send out their souls at night to meet with other strigoi or suck the blood of livestock and neighbours. Dead strigoi are reanimated corpses that also suck blood and attack their family. Live strigoi turned into the other variety after death, but there were also many other ways of becoming a dead strigoi. Another type of vampire, or perhaps another term for a vampire in Romanian folklore is Moroi.

Romanian folklore described numerous ways of becoming a vampire. A person born with a caul, an extra nipple, a tail, or extra hair, was doomed to become a vampire. The same fate applied to the seventh child in any family if all of his or her previous siblings were of the same sex, someone born too early, and someone whose mother had encountered a black cat crossing her path. If a pregnant woman did not eat salt or was looked upon by a vampire or a witch, her child would also become a vampire. So would a child born out of wedlock. Others who became vampires were those who died an unnatural death or before baptism. Finally a person with red hair and blue eyes was seen as a potential strigoi. Living vampires were identified by distributing garlic in church and observing who would refuse to eat it.

Romanian vampires were said to bite their victims over the heart or between the eyes, never on the neck. It would attack family members and livestock. Sudden deaths could be a sign that a vampire was around. They would also indulge in poltergeist-like activity such as throwing things around in the house. Graves were often opened three years after the death of a child, five years after the death of a young person, or seven years after the death of an adult to check for vampirism.

Vampires were believed to be especially active in the winter, and more specifically on the eve of two religious holidays, the Feast of St. George and the Feast of St. Andrew. Bram Stoker makes reference to this in his novel Dracula (1897) when Jonathan Harker is warned that at midnight "all the evil things in the world will have full sway." During these nights, the people kept their houses lit and used apotropaics such as thorns, crosses and garlic to prevent the vampires from entering their homes. Cattle were also rubbed with garlic.

Roma

Roma frequently feature in vampire fiction and film, no doubt influenced by the Bram Stoker's Dracula, in which the Szgany Roma served Dracula, carrying his boxes of earth and guarding him.

The mullo (one who is dead) is believed to return and do malicious things and/or suck the blood of a person. It was often a relative who had caused their relative's death, or who did not properly observe the burial ceremonies, or kept the deceased's possessions instead of destroying them as was proper. Female vampires could return, lead a normal life and even marry but would eventually exhaust the husband. Male vampires could father children, known as Dhampirs, who could be hired to detect and get rid of vampires.

Anyone who had a horrible appearance, was missing a finger, or had appendages similar to those of an animal, was believed to be a vampire. A person who died alone and unseen would become a vampire, likewise if a corpse swelled or turned black before burial. Dogs, cats, plants or even agricultural tools could become vampires. Pumpkins or melons kept in the house too long would start to move, make noises or show blood. According to the late Serbian ethnologist Tatomir Vukanović, Roma people in Kosovo believed that vampires were invisible to most people, but could be seen "by a twin brother and sister born on a Saturday who wear their drawers and shirts inside out." Likewise, a settlement could be protected from a vampire "by finding a twin brother and sister born on a Saturday and making them wear their shirts and drawers inside out...This pair could see the vampire out of doors at night, but immediately after it saw them it would have to flee, head over heels."

Greek

Main article: VrykolakasAlthough not related to ancient Greek, blood-drinking beings such as Lamia, the modern Greek equivalent of a vampire is known as the vrykolakas, similar in many ways to the European vampire. Belief in vampires (usually called βρυκόλακας, vrykolakas, though reportedly referred to as καταχανάδες, katakhanades, on Crete) was persistent throughout Greek history, although vampires are now seen as mythical creatures in modern times rather than factual entities. Belief in vampire lore grew so prominent, that many practices were enforced to both prevent and combat vampirism. Many rituals were carried out, but most, if not all, have now fallen into decline. One ritual entailed that entailed the deceased was exhumed from its grave after three years of death. If the body was fully decayed, the remaining bones were put in a box by relatives and wine poured over them, a priest would then read from scriptures. However, if the body had not sufficiently decayed, the corpse would be labelled a vampire and treated appropriately.

According to Greek beliefs, vampirism could occur through various means: excommunication or desecrating a religious day, committing a great crime, or dying alone. Other more superstitious causes include having a cat jump across the grave, eating meat from a sheep killed by a wolf or having been cursed. It was also believed in more remote regions of Greece that unbaptized people would be doomed to vampirism in the afterlife.

They were usually thought to be indistinguishable from living people, giving rise to many folk tales with this theme. However, this was not the case everywhere: on Mount Pelion vampires glowed in the dark, while on the Saronic islands vampires were thought to be hunchbacks with long nails; on the island of Lesbos vampires were thought to have long canine teeth much like wolves.

Vampires could be harmless, sometimes returning to support their widows by their work. However, they were usually thought to be ravenous predators, killing their victims who would be condemned to become vampires,though blood-drinking in particular was not a prominent part of the legends. Vampires were so feared for their potential for great harm, that a village or an island would occasionally be stricken by a mass panic if a vampire invasion were believed imminent. Nicholas Dragoumis records such a panic on Naxos in the 1930s, following a cholera epidemic.

Varieties of wards were employed for protection in different places, including blessed bread (antidoron) from the church, crosses and black-handled knives. To prevent vampires from rising from the dead, their hearts were pierced with iron nails whilst resting in their graves, or their bodies burned and the ashes scattered. Because the Church opposed burning people who had received the myron of chrismation in the baptism ritual, cremation was considered a last resort.

Western Europe

The Baobhan sith from the Scottish Highlands, and the Lhiannan Shee of the Isle Of Man are two faerie spirits with decidedly vampiric tendencies. The Bruxsa of Portugal is another female vampiric spirit hostile to humans.

World beliefs

New England

During the late 18th and 19th centuries the belief in vampires was widespread in parts of New England, particularly in Rhode Island and Eastern Connecticut. In this region there are many documented cases of families disinterring loved ones and removing their hearts in the belief that the deceased was a vampire who was responsible for sickness and death in the family (although the word "vampire" was never used to describe him/her). The deadly tuberculosis, or "consumption" as it was known at the time, was believed to be caused by nightly visitations on the part of a dead family member (who had died of consumption him/herself). The most famous (and latest recorded) case is that of nineteen year old Mercy Brown who died in Exeter, Rhode Island in 1892. Her father, assisted by the family physician, removed her from her tomb two months after her death. Her heart was cut out then burnt to ashes. An account of this incident was found among the papers of Bram Stoker and the story closely resembles the events in his classic novel, Dracula.

The Caribbean and the Americas

The Loogaroo is an example of how a vampire belief can result from a combination of beliefs, here a mixture of French and African Vodu or voodoo. The term Loogaroo possibly comes from the French mythological creature called the Loup-garou, a type of werewolf and is common in the Culture of Mauritius. However, the stories of the Loogaroo are widespread through the Caribbean Islands and Louisiana in the USA. Similar female monsters are the Soucouyant of Trinidad, and Tunda and Patasola of Colombian folklore, while the Mapuche of southern Chile have the bloodsucking snake known as the Peuchen. Aztec mythology described tales of the Cihuateteo, skeletal-faced spirits of those who died in childbirth who stole children and entered into sexual liaisons with the living and drove them mad.

Africa

Various regions of Africa have folkloric tales of beings with vampiric abilities: in West Africa the Ashanti people tell of the iron-toothed and tree-dwelling asanbosam, and the Ewe people the adze, which can take the form of a firefly and hunts children. The eastern Cape region has the impundulu, which can take the form of a large taloned bird and can summon thunder and lightning, and the Betsileo people of Madagascar the ramanga, an outlaw or living vampire who drank the blood and ate the nail clippings of nobles.

India

India of later times is also familiar with many vampiric entities. The Bhūta or Prét is the soul of a man who died an untimely death. It wanders around animating dead bodies at night, attacking the living much like a ghoul. In northern India, there is the BrahmarākŞhasa, a vampire-like creature with a head encircled by intestines and a skull from which it drank blood.

Southeast Asia

Similar legends of female vampire-like beings who can detach parts of their upper body occur in the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. There are two vampire-like creatures in the Philippines: the Tagalog mandurugo (blood-sucker) and the Visayan manananggal (self-segmenter or viscera sucker). The mandurugo is a variety of the aswang that takes the form of an attractive girl by day, and develops wings and a long, hollow, thread-like tongue by night. The tongue is used to suck up blood from a sleeping victim. The manananggal of Visayan Filipino folklore is described as being an older, beautiful woman capable of severing its upper torso in order to fly into the night with huge bat-like wings to prey on unsuspecting, sleeping pregnant women in their homes. They use an elongated proboscis-like tongue to suck fetuses off these pregnant women. They also prefer to eat entrails (specifically the heart and the liver) and the phlegm of sick people.

The Malaysian Penanggalan may either be a beautiful old or young woman who obtained her beauty through the active use of black magic, supernatural, mystical, or paranormal means which is most commonly described in local folklores to be dark or demonic in nature. She is able to detach her fanged head which flies around in the night looking for blood, typically from pregnant women. The Leyak is similar being from Balinese folklore. A Pontianak, Kuntilanak or Matianak in Indonesia, or Langsuir in Malaysia, is a woman who died during childbirth and becomes undead, seeking revenge and terrorizing villages.

China and Korea

Jiang Shi (simplified Chinese: 僵尸; traditional Chinese: 僵屍 or 殭屍; pinyin: jiāngshī; literally "stiff corpse"), sometimes called Chinese vampires by Westerners, are reanimated corpses that hop around, killing living creatures to absorb life essence (qì) from their victims. jiāngshī is pronounced geungsi in Cantonese, and gangshi in Korean. They are said to be created when a person's soul (魄 pò) fails to leave the deceased's body. One unusual feature of folklore is their greenish-white furry skin; one theory is this is derived from fungus or mould growing on corpses. The influence of Western vampire stories brought the blood-sucking aspect to the Chinese myth in modern times.

Jiang Shis were a popular subject in Hong Kong movies during the 1980s; some movies even featured both Jiang Shis and "Western" zombies. In the movies, Jiang Shis can be put to sleep by putting on their foreheads a piece of yellow paper with a spell written on it (Chinese talisman or 符 pinyin fú). Generally in the movies the Jiang Shi are dressed in imperial Qing Dynasty clothes, their arms permanently outstretched due to rigor mortis. Like those depicted in Western movies, they tend to appear with an outrageously long tongue and long fingernails. They can be evaded by holding one's breath, as they track living creatures by detecting their breathing. Their visual depiction as horrific Qing Dynasty officials reflects a common stereotype among the Han Chinese of the foreign Manchu people, who founded the much-despised dynasty, as bloodthirsty creatures with little regard for humanity.

It is also conventional wisdom of feng shui in Chinese architecture that a threshold (Chinese: 門檻), a piece of wood approximately 15 cm (6 in) high, be installed along the width of the door at the bottom to prevent a Jiang Shi from entering the household.

Japan

Kyūketsuki, (Japanese meaning 'blood sucking demon') are vampires in Japan. Very few stories of vampiric monsters were actually told in Japan until the mid 1990's. They are common in Japanese fiction such as manga, and are often simply a Japanese word for vampires in general (usually European) or less commonly, a unique race of Japanese vampiric beings. They are often linked to a system of blood purity in which the original kyūketsuki are the most powerful and are called shinso. Shino are able to convert others to kyūketuki, but their power will generally be weaker than the original.

Modern beliefs

Belief in vampires persists to this day. While some cultures preserve their original traditions about the immortal, most modern-day believers are more influenced by the fictional image of the vampire as it occurs in films and literature.

There were rumours spread by the local press in early 1970 that a vampire haunted Highgate Cemetery in London. Amateur vampire hunters flocked in large numbers in the cemetery. Several books have been written about the case, notably by Sean Manchester, a local man who was among the first to suggest the existence of the "Highgate Vampire" and who later claimed to have exorcised and destroyed a whole nest of vampires in the area.

In the modern folklore of Puerto Rico and Mexico, the chupacabra (goat-sucker) is said to be a creature that feeds upon the flesh or drinks the blood of domesticated animals, leading some to consider it a kind of vampire. The "chupacabra hysteria" was frequently associated with deep economic and political crises, particularly during the mid-1990s.

Hysteria about alleged attacks of vampires swept through the African country of Malawi during late 2002 and early 2003. Mobs stoned one individual to death and attacked at least four others, including Governor Eric Chiwaya, based on the belief that the government was colluding with vampires.

In Romania during February of 2004, several relatives of the late Toma Petre feared that he had become a vampire. They dug up his corpse, tore out his heart, burned it, and mixed the ashes with water in order to drink it.

In January 2005, rumours began to circulate that an attacker had bitten a number of people in Birmingham, England, fueling concerns about a vampire roaming the streets. However, local police stated that no such crime had been reported. This case appears to be an urban legend.

In March 2007, self-proclaimed vampire hunters broke into the tomb of Slobodan Milošević, former president of Serbia and Yugoslavia, and staked his body through the heart into the ground. Although the group involved claimed this act was to prevent Milošević from returning as a vampire, it is not known whether those involved actually believed this could happen or if the crime was simply politically motivated.

Natural propagations for beliefs

Pathology

Decomposition

People sometimes reported that the cadaver did not look as they thought a normal corpse should when the coffin of an alleged vampire was opened. This was often taken to be evidence of vampirism. However, corpses decompose at different speeds depending on temperature and soil composition, and some of the signs of decomposition are not widely known. This has led vampire hunters to mistakenly conclude that a dead body had not decomposed at all, or, ironically, to interpret signs of decomposition as signs of continued life. Corpses swell as gases from decomposition accumulate in the torso and the increased pressure forces blood to ooze from the nose and mouth. This causes the body to look "plump", "well-fed" and "ruddy" - changes that are all the more striking if the person was pale or thin in life. In the Arnold Paole case, an old woman's exhumed corpse was judged by her neighbours to look more plump and healthy than she had ever looked in life. The exuding blood gave the impression that the corpse had recently been engaging in vampiric activity.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). The staking of a swollen, decomposing body could cause the body to bleed and force the accumulated gases to escape the body. This could produce a groan when the gases moved past the vocal chords, or a sound reminiscent of flatus when they passed through the anus. The official reporting on the Peter Plogojowitz case speaks of "other wild signs which I pass by out of high respect".

After death, the skin and gums lose fluids and contract, exposing the roots of the hair, nails, and teeth, even teeth that were concealed in the jaw. This can produce the illusion that the hair, nails, and teeth have grown. At a certain stage, the nails fall off and the skin peels away, as reported in the Plogojowitz case - the dermis and nail beds emerging underneath were interpreted as "new skin" and "new nails". Finally, decomposition also causes the body to shift or contort itself, adding to the illusion that the corpse has been active after death.

Premature burial

It has also been hypothesized that vampire legends were influenced by individuals being buried alive, due to primitive knowledge in medicine. In some cases where people reported sounds emanating from a specific coffin, it was later dug up and fingernail marks were discovered on the inside from the victim trying to escape. In other cases the person would hit their heads/noses/faces and it would appear that they had been "feeding". A problem with this theory is how people presumably buried alive managed to stay alive for an extended period without food, water or oxygen. An alternate explanation for noise is the bubbling of escaping gases from natural decomposition of bodies. Another likely cause of disordered tombs, though, is that of graverobbing.

Contagion

Folkloric vampirism has been associated with a series of deaths due to unindentifiable or mysterious illnesses, usually within the same family or the same small community. The "epidemic pattern" is obvious in the classical cases of Peter Plogojowitz and Arnold Paole, and even more so in the case of Mercy Brown and in the vampire beliefs of New England generally, where a specific disease, tuberculosis, was associated with outbreaks of vampirism (see above).

In his book, De masticatione mortuorum in tumulis (1725), Michaël Ranft attempted to explain folk beliefs in vampires in a natural way. He says that, in the event of the death of every villager, some other person or people - much probably a person related to the first dead - who saw or touched the corpse, would eventually die either of some disease related to exposure to the corpse or of a frenetic delirium caused by the panic of merely seeing the corpse. These dying people would say that the dead man had appeared to them and tortured them in many ways. The other people in the village would exhume the corpse to see what it had been doing. He gives the following explanation when talking about the case of Peter Plogojowitz:

This brave man perished by a sudden or violent death. This death, whatever it is, can provoke in the survivors the visions they had after his death. Sudden death gives rise to inquietude in the familiar circle. Inquietude has sorrow as a companion. Sorrow brings melancholy. Melancholy engenders restless nights and tormenting dreams. These dreams enfeeble body and spirit until illness overcomes and, eventually, death.

Porphyria

Porphyria, a rare blood disorder that disrupts the production of haem, has been proposed as an origin of reported vampirism. It was thought to be more common than elsewhere in small Transylvanian villages (roughly 1000 years ago) where inbreeding probably occurred. The haem group, found in every blood cell in the human body, is excited by electrons, but in a controlled fashion. However, the haem groups in porphyria sufferers causes uncontrollable tissue, bone and skin damage, made worse when the person comes into contact with sunlight. This would have given the porphyria sufferer a very pallid skin colour, with teeth that appear larger than normal, due to the porphyria damaging the gum tissue and causing it to recede. These people would have been very anemic, and drinking (animal) blood was a traditional treatment for anemia.

Certain forms of porphyria are also associated with neurological or psychiatric symptoms. However, suggestions that porphyria sufferers crave the heme in human blood, or that the consumption of blood might ease the symptoms of porphyria, are based on a misunderstanding of the disease.

Rabies

Rabies has been linked with vampire folklore. Dr Juan Gomez-Alonso, a neurologist at Xeral Hospital in Vigo, Spain, examined this in a report in the journal Neurology. The susceptibility to garlic and light could be due to hypersensitivity, which is a symptom of rabies. The disease can also affect portions of the brain that could lead to disturbance of normal sleep patterns (i.e., becoming nocturnal) and hypersexuality. Legend once said a man was not rabid if he could look at his own reflection, which relates to the legend of a vampire not having a reflection. Wolves and bats, which are often associated with vampires, can be carriers of rabies. The disease can also lead to a drive to bite others, and to a bloody frothing at the mouth.

Psychopathology

Some psychologists in modern times recognize a disorder called clinical vampirism or Renfield syndrome, from Dracula's insect-eating henchman, Renfield, in the novel by Bram Stoker in which the victim is obsessed with drinking blood, either from animals or humans.

There have been a number of murderers who performed seemingly vampiric rituals upon their victims. Serial killers Peter Kurten and Richard Trenton Chase were both called "vampires" in the tabloids after they were discovered drinking the blood of the people they murdered. Similarly, in 1932, an unsolved murder case in Stockholm, Sweden, was nicknamed the "Vampire murder", due to the circumstances of the victim’s death. The infamous Hungarian countess and mass murderer Elizabeth Báthory of the late 16th and early 17th century was popularised in the 18th and 19th centuries. The most common motif of these works that of her bathing in her victims' blood in order to retain beauty or youth clearly has a common theme with vampirism and was belately linked in the 1970s.

Vampire lifestyle is a term for a contemporary subculture of people largely within the Goth subculture who consume the blood of others as a pastime; drawing from the rich recent history of popular culture related to cult symbolism, horror films, the fiction of Anne Rice, and the styles of Victorian England.

Vampire bats

Bats have become an integral part of the traditional vampire only recently, although many cultures have stories about them. In Europe, bats and owls were long associated with the supernatural, mainly because they were night creatures. Conversely, the Gypsies thought them lucky and wore charms made of bat bones. In English heraldic tradition, a bat means "Awareness of the powers of darkness and chaos". In South America, Camazotz was a bat god of the caves living in the Bathouse of the Underworld. The three species of actual vampire bats are all endemic to Latin America, and there is no evidence to suggest that they had any Old World relatives within human memory. It is therefore extremely unlikely that the folkloric vampire represents a distorted presentation or memory of the bat. During the 16th century the Spanish conquistadors first came into contact with vampire bats and recognized the similarity between the feeding habits of the bats and those of their legendary vampires. The bats were named after the folkloric vampire rather than vice versa; the Oxford English Dictionary records the folkloric use in English from 1734 and the zoological not until 1774. It wasn't long before vampire bats were adapted into fictional tales, and they have become one of the more important vampire associations in popular culture.

In popular fiction

The vampire is now a dominant fixture in popular fiction and horror titles; this stems from the early 1800s after a series of vampiric novels were released, but the vampire and fiction certainly date back further into the late 1700s when the revenant appeared in poems such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's 1797 work of Die Braut von Corinth (The Bride of Corinth). Lord Byron introduced the vampire theme to Western literature in his epic poem The Giaour (1813), but it was his personal physician John Polidori who authored the first "true" vampire story called The Vampyre. The vampire made the transition into prose works when Poldori used Byron's own wild life as the model for his undead protagonist Lord Ruthven. Poldori had earlier composed an enigmatic fragmentary story concerning the mysterious fate of an aristocrat named Augustus Darvell whilst journeying in the Orient - as his contribution to the famous ghost story competition at the Villa Diodati by Lake Geneva in 1816, between him, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley and Polidori. The story was highly successful and the most influential vampire work of the early 19th century.

Literature

Main article: Vampire literature

Varney the Vampire was a landmark popular mid-Victorian era gothic horror story by James Malcolm Rymer (alternatively attributed to Thomas Preskett Prest), which first appeared 1845-47 in a series of pamphlets generally referred to as penny dreadfuls because of their inexpensive price and typically gruesome contents. The story was published in book form in 1847 and was of epic length: the original edition runs to 868 double columned pages divided into 220 chapters. It has a distinctly suspenseful style, using vivid imagery to describe the horrifying exploits of Varney. Other examples of early vampire stories exist, such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge's unfinished poem Christabel, and Sheridan Le Fanu's lesbian vampire story, "Carmilla" published in 1871. Like Varney before her, the vampire Carmilla is portrayed in a somewhat sympathetic light as the compulsion of her condition is highlighted.

However, despite all earlier efforts to portray the vampire in popular fiction, none have been as influenticial nor as definitive as Bram Stoker's Dracula. Its portrayal of vampirism as a disease (contagious demonic possession), with its undertones of sex, blood and death, struck a chord in a 1897 Victorian Europe where tuberculosis and syphilis were common. Most of Stoker's vampric traits were adapted into future fiction and folkloric descriptions combined with Dracula's traits to develope into the vampire we know today. Drawing on past works such as The Vampyre and "Carmilla", Stoker began to research his new book in the late 1800s, reading works such as The Land Beyond the Forest (1888) and other books of Transylvania and vampires. A member of the cult Order of the Golden Dawn, he was keen to travel around Eastern Europe to learn about the folkloric vampires and occult. In London, a colleague mentioned to him about the story of Vlad Tepes, the real-life Dracula, and Stoker immediately incorporated this story into his book. The first chapter of the book was omitted when it was published in 1897, but it was released alter in 1914 as Dracula's Guest.

The latter part of the twentieth centry saw the rise of multi-volume vampire epics. The first of these was gothic romance writer Marilyn Ross's Barnabas Collins series (1966-71) loosely based on the contemporary American TV series Dark Shadows. It also set the trend for seeing vampires as poetic tragic heroes rather than as the traditional embodiment of evil. This formula was followed in the highly popular and influential Vampire Chronicles (1976-2003) series of novels by Anne Rice.

Film

Main article: Vampire filmsConsidered one of the eminent figures of the classic horror film, vampires have proven to be a rich subject for the film and gaming industries. Dracula is a major character in more movies than any other bar Sherlock Holmes, and early films were either based on the novel of Dracula or closley derived from it. These included the landmark 1922 German silent film Nosferatu, directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau featuring the first film portrayal of Dracula - although names and characters were intended to mimic Dracula's, Murnau could not obtain permission to do so from Stoker's widow, so had to alter many aspects of the film. In addition to this film was Universal's Dracula, starring Bela Lugosi as the count in what was the first talking film to portray Dracula. However, Browning's film was overshadowed in 1932 by Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr, loosely based on "Carmilla", which was highly acclaimed by critics. And so the media's fascination with the vampire came to a head, following with movies such as Dracula's Daughter in 1936.

The legend of the vampire was cemented in the film industry when Dracula was reincarnated for a new generation with the celebrated Hammer Horror series of films, starring Christopher Lee as the Count. The successful 1958 film Dracula starring Lee was followed by seven sequels. Lee returned as Dracula in all but two of these and became well known in the role. By the 1970s, vampires in films had diversified with films such as Count Yorga, Vampire in 1970, an African Count in 1972's Blacula, and a Nosferatu-like vampire in 1979's Salem's Lot, as well as several female vampire antagonists, though the plotlines still revolved around a central evil vampire character. Later films showed more diversity in plotline, with some focusing on the vampire-hunter such as Blade in the Marvel Comics' Blade Trilogy movies and the film and television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Still others showed the vampire as protagonist such as the 1994 Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles and its indirect sequel of sorts Queen of the Damned, and The Hunger. Bram Stoker's Dracula was a noteworthy 1992 remake which became the then-highest grossing vampire film ever.

Films such as Blade also heralded renewed interest in vampire societies, subsequently depicted in Underworld in 2003, and the Russian Night Watch and a TV miniseries remake of 'Salem's Lot, both from 2004.

Notes

- ^ Silver & Ursini, p. 22-23

- ^ Silver & Ursini, p. 37-38

- Barber, P (1988). Vampires, Burial and Death: Folklore and Reality. New York: Yale University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-300-04126-8.

- Tokarev, S.A. (1982). Mify Narodov Mira ("Myths of the Peoples of the World").

- Template:De icon "Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jacob Grimm und Wilhelm Grimm. 16 Bde. (in 32 Teilbänden). Leipzig: S. Hirzel 1854-1960". Retrieved 2006-06-13.

- "Vampire". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-06-13.

- Template:Fr icon "Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé". Retrieved 2006-06-13.

- Template:Fr icon Dauzat, A. (1938). Dictionnaire étymologique. Librairie Larousse.

- Weibel, Peter. "Phantom Painting - Reading Reed: Painting between Autopsy and Autoscopy". David Reed's Vampire Study Center. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English. 1955.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 2006-06-13.

- ^ Template:Ru icon "Russian Etymological Dictionary by [[Max Vasmer]]". Retrieved 2006-06-13.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) Cite error: The named reference "Vasmer" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Melton, J.G. (1999). "Chronology". The Vampire Book - The Encyclopedia of the Undead. 2nd Edition. Visible Ink Press. pp. xxxi. ISBN 1-57859-071-X.

- Template:Ru icon Sobolevskij, A. I., Slavjano-russkaja paleografija

- http://www.stsl.ru/manuscripts/book.php?col=1&manuscript=089 The original manuscript, Книги 16 Пророков толковыя

- "Löfstrand, Elisabeth. V nacale bylo slovo - om språkhistorisk forskning vid Institutionen för slaviska och baltiska språk. Föreläsningar hållna vid Institutionens för slaviska och baltiska språk femtioårsjubileum 1994". Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ^ Lind, John H (2004). "Varangians in Europe's Eastern and Northern Periphery". ennen & nyt (4). ISSN: 1458-1396. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- "Ванькова А.Б., Родионов О.А., Долотова И.А. История России. 6-7 кл : Учебник для основной школы: В 2-х частях. Ч. 1: С древнейших времен до конца XVI века.- М.: ЦГО, 2002.- 256 c. : ил.; 60х90/16 .- ISBN 5-7662-0149-4 (В пер.) , 1000 экз. (тир.) УДК 371.671.11:94(47).01/04.. ББК 63.3(2)4я721" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- "Рыбаков Б.А. Язычество древних славян / М.: Издательство 'Наука', 1981 г." Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- Зубов, Н.И. (1998). "Загадка периодизации славянского язычества в древнерусских списках "Слова св. Григория … о том, како первое погани суще языци, кланялися идолом…"". Живая старина (1(17)). Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ^ Graves, R (1955). "The Empusae". Greek Myths. London: Penguin. pp. 189–90. ISBN 0-14-001026-2.

- ^ Graves, R (1955). "Lamia". Greek Myths. London: Penguin. pp. 205–06. ISBN 0-14-001026-2.

- ^ Siegmund Hurwitz, Lilith, die erste Eva: eine Studie uber dunkle Aspekte des Wieblichen. Zurich: Daimon Verlag, 1980, 1993. English tr. Lilith, the First Eve: Historical and Psychological Aspects of the Dark Feminine, translated by Gela Jacobson. Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag, 1992 ISBN 3-85630-545-9.

- Marigny, J (1993). "Blood Lust". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- Bunson, p. 66

- Barber, p. 41-42

- Barber, p. 2

- Bunson, p. 35

- ^ Reader's Digest Association Ltd (1988). "Vampires Galore!". Strange Stories, Amazing Facts. London: Reader's Digest Services Pty Ltd. pp. 432–433. ISBN 0-949819-89-1.

- Barber, p. 33

- Barber, p. 50-51

- Lawson, JC (1910). Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion. Cambridge. pp. p. 405-06.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Barber, p. 49

- ^ Jaramillo Londoño, Agustín (1967). Testamento del paisa. Editorial Bedout: Medellín. Cite error: The named reference "Jaramillo" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Barber, p. 125

- Barber, p. 109

- Barber, p. 114-15

- Barber, p. 63

- Mappin, J. (2003). Didjaknow: Truly Amazing & Crazy Facts About... Everything. Australia: Pancake. p. 50. ISBN 0-330-40171-8.

- Burkhardt, p. 221

- ^ Spence, Lewis (1960). An Encyclopaedia of Occultism. University Books, Inc.

- Silver & Ursini, p. 25

- Barber, p. 73

- Template:De icon Alseikaite-Gimbutiene, Marija (1946). Die Bestattung in Litauen in der vorgeschichtlichen Zeit. Tübingen.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vukanovic, TP (1959). "The Vampire". Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society. 38: 111–18.

- Template:De icon Klapper, Joseph (1909). "Die schlesischen Geschichten von den schädingenden Toten". Mitteilungen der schlesischen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde. 11: 58–93.

- Template:De icon Löwenstimm, A (1897). Aberglaube und Stafrecht. Berlin. pp. p. 99.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Template:De iconBăchtold-Staubli, H (1934–35). Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Template:De icon Filipovic, Milenko (1962). "Die Leichenverbrennung bei den Südslaven". Wiener völkerkundliche Mitteilungen. 10: 61–71.

- Barber, p. 158

- Barber, p. 73

- Barber, p. 157

- Bunson, p. 154

- ^ Silver & Ursini, p. 38-9

- Silver & Ursini, p. 25

- McNally, Raymond T. (1994). In Search of Dracula. p. 117. ISBN 0-395-65783-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Marigny, J (1993). "Blood Lust". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- ^ Summers, M (1968). "Chapter I: The Vampire in Greece and Rome of Old". The Vampire in Europe. New York: University Books Inc. pp. 1–77.

- "The Alphabet of Ben Sira Question #5 (23a-b)".

- ^ Marigny, J (1993). "Blood Lust". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 17–19. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- Raphael Patai p222, The Hebrew Goddess 1978, 3rd enlarged edition from Discus Books New York.

- Siegmund Hurwitz, p.40 Lilith, die erste Eva: eine Studie uber dunkle Aspekte des Wieblichen. Zurich: Daimon Verlag, 1980, 1993. English tr. Lilith, the First Eve: Historical and Psychological Aspects of the Dark Feminine, translated by Gela Jacobson. Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag, 1992 ISBN 3-85630-545-9.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica Article: Lamashtu".

- Hurwitz p.34-35

- Hurwitz p.36

- "Lamashtu-Ancient Near East".

- Hurwitz p.36

- Hurwitz p.40

- Hurwitz p.41

- Boyle, A. "Sex and booze figured in Egyptian rites: Archaeologists find evidence for ancient version of 'Girls Gone Wild'". MSNBC. Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- Oliphant, Samuel Grant (1913). "The Story of the Strix: Ancient". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 44: 133–49.

- Marigny, J (1993). "Blood Lust". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 15–17. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- Burton, Sir Richard R. (1870). Vikram and The Vampire:Classic Hindu Tales of Adventure, Magic, and Romance. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- Schwartz p.15

- Schwartz p.15

- "J.R. Ritman Libary: Lilith Amulet".

- Schwartz p. 20 Note: 38

- William of Newburgh (2000). "Book 5, Chapter 22-24". Historia rerum Anglicarum. Fordham University. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jones, p. 121

- Barber, p. 5-9

- Barber, p. 15-21

- "Introvigne, Massimo. 1997. Satanism Scares and Vampirism from the 18th Century to the Contemporary Anti-Cult Movement. A paper presented at the World Dracula Congress, Los Angeles 1997". Retrieved 2006-06-17.

- Burkhardt, p. 225

- Template:De icon Jaworskij, Juljan (1898). "Südrussische Vampyre". Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde. 8: 331–36.

- Template:De icon Kanitz, F (1875). Donaubulgarien und der Balkan. p. 80.

- Jones, p. 107

- ^ Levkievskaja, E.E. La mythologie slave : problèmes de répartition dialectale (une étude de cas : le vampire). Cahiers slaves n°1 (septembre 1997). Online (French)

- Glišić, Milovan, "Posle devedeset godina" (Ninety Years Later)

- Vukovic, p. 58

- Vuković, p. 213

- Словник символів, Потапенко О.І., Дмитренко М.К., Потапенко Г.І. та ін., 1997.Online article (Ukrainian)

- Франко И., Сожжение упырей в Нагуевичах (Кіевская старина. — 1890. — Т.29. — №4. — С.101-120.) Online

- Cremene, p. 89

- Cremene, p. 37

- ^ Cremene, p. 38

- Cremene, p. 100

- http://www.darkness-embraced.com/php/Sections-index-req-printpage-artid-20.phtml

- Bunson, p. 64-69

- ^ Vukanovic, TP (1958). "The Vampire". Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society. 37: 21–31.

- Bunson, p. 278

- Dickens, Charles Jr. "The Year Round - Vampires and Ghouls".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Summers, M (1968). "Chapter IV: Modern Greece". The Vampire in Europe. New York: University Books Inc. pp. 217–281.

- Greek Vampires

- Tomkinson, J.L. (2004). Haunted Greece: Nymphs, Vampires and other Exotika. Athens: Anagnosis. ISBN 960-88087-0-7.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - Briggs, Katharine (1976). A Dictionary of Fairies. Middlesex: Penguin. pp. p. 16. ISBN 0-14-00-4753-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Briggs, p. 266

- "Sledzik, Paul S. and Nicholas Bellantoni. 1994. Bioarcheological and Biocultural Evidence for the New England Vampire Folk Belief. In The American Journal of Physical Anthropology No. 94. (A table of historic vampire accounts)". Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Bell, M.E. "Interview with a REAL Vampire Stalker". SeacoastNH.com. Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Template:Es iconMartinez Vilches, Oscar (1992). Chiloe Misterioso: Turismo, Mitologia Chilota, leyendas. Chile: Ediciones de la Voz de Chiloe. p. 179. ISBN 0-19-451308-4.

- Bunson, p. 11

- Bunson, p. 2

- Bunson, p. 219

- Bunson, p. 23-24

- Ramos, Maximo D. (1971). Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology. Philippines: University of the Philippines Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Bunson, p. 197

- Michele Stephen (August 1999). "Witchcraft, Grief, and the Ambivalence of Emotions". American Ethnologist. 26 (3): 711–737. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- Bunson, p. 208

- Bunson, p. 150

- Suckling, Nigel (2006). Vampires. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 190433248X.

- de Groot, JJM (1892–1910). The Religious System of China. The Hague.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Newman, Kim (1996). The BFI Companion to Horror. London: Cassell. pp. p. 175. ISBN 0-304-33216-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - "'Vampires' strike Malawi villages". BBC News. 2002. Retrieved 2005-08-17.

- "Romanian villagers decry police investigation into vampire slaying", Matthew Schofield, Knight Ridder Newspapers, March 24 2004

- "Reality Bites". The Guardian. 2005. Retrieved 2005-08-17.

- "Slobodan Milosevic's heart staked". 2007.

- Barber, Paul (1996-03-01). "Staking claims: the vampires of folklore and fiction". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved 2006-04-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Benecke, Mark and David Pescod-Taylor. "The Restless Dead: Vampires & Decomposition". Bizarre Magazine, May-June 1997. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- Barber, p. 117

- Barber, p. 119

- Marigny, J (1993). "The Golden Age of the Vampire". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 48–49. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- Barber, p. 128

- Barber, p. 137-38

- "Sledzik, Paul S. and Nicholas Bellantoni. 1994. Bioarcheological and Biocultural Evidence for the New England Vampire Folk Belief. In The American Journal of Physical Anthropology No. 94". Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- "BBC-Rabies-The Vampire's Kiss". Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Template:Sv iconLinnell, Stig (1968). Stockholms spökhus och andra ruskiga ställen. ISBN 978-91-518-2738-4.

- Skal, David J. (1993). The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror. New York: Penguin. pp. p. 342-43. ISBN 0-14-024002-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - "HERALDIC "MEANINGS"". American College of Heraldry. Retrieved 2006-04-30.

- Marigny, J (1993). "Documents: The vampire in poetry". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 114–115. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- Silver & Ursini, p. 40-41

- Silver & Ursini, p. 43

- Marigny, J (1993). "The Reawakening of the Vampire: The Forces of Good and Evil". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 82–85. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- Silver & Ursini, p. 205

- Marigny, J (1993). "The Reawakening of the Vampire". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 90–92. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- ^ Marigny, J (1993). "The Reawakening of the Vampire". Vampires: The World of the Undead. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 92–95. ISBN 0-500-30041-0.

- Silver & Ursini, p. 208

References

See alsoRelated links

Related mythological creaturesExternal links |