This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Christopherlin (talk | contribs) at 00:12, 31 December 2005 (fix for). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:12, 31 December 2005 by Christopherlin (talk | contribs) (fix for)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For the Patrick O'Brian novel, see Aubrey-Maturin series § The Letter of Marque, and The Letter of Marque.

A letter of marque and reprisal was an official warrant or commission from a national government authorizing the designated agent to search, seize, or destroy specified assets or personnel belonging to a party which had committed some offense under the laws of nations against the assets or citizens of the issuing nation, and was usually used to authorize private parties to raid and capture merchant shipping of an enemy nation.

The formal statement of the warrant was to authorize the agent to pass beyond the borders of the nation ("marque", meaning frontier), and there to search, seize, or destroy assets or personnel of the hostile foreign party ("reprisal"), not necessarily a nation, to a degree and in a way that was proportional to the original offense. It was considered a retaliatory measure short of a full declaration of war, and by maintaining a rough proportionality, was intended to justify the action to other nations, who might otherwise consider it an act of war or piracy. As with a domestic search, arrest, seizure, or death warrant, to be considered lawful it had to have a certain degree of specificity, to insure that the agent did not exceed his authority and the intent of the issuing authority.

A private ship and its captain and crew operating under a letter of marque and reprisal was called a privateer.

Letter of Marque by nations

United Kingdom

Letters of marque were issued by England and later the United Kingdom until the signing of the Declaration of Paris in 1856. Famous recipients include Sir Francis Drake, Sir Henry Morgan, and William Kidd. To further illustrate the subtlety between piracy and privateering, both Henry Morgan and William Kidd were later brought up on charges of piracy by England.

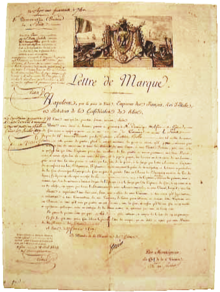

France

Letters of Marque were given in a very selective manner.

Under Napoleon, they covered a six-month period, in case war would stop. This had the consequence that captains left port with several letters, since expeditions rarely lasted less than a year. Back to harbour, the captain had to hand the letter over to the naval authorities, which destroyed it (hence their rarity).

Letters of Marque were abolished on the 16th of April 1856, in an annex to the Treaty of Paris (the USA being one of the main nations not to ratify the treaty).

USA

The United States Constitution (Art. I § 8) authorized only Congress to issue letters of marque and reprisal. Such issuance is not restricted to private actors, however, and such a warrant could potentially be issued to the President, as an authorization for limited offensive warlike operations outside the territory of the United States. However, Douglas Kmiec, Dean of the Columbus School of Law, in testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, April 17, 2002, said:

Letters of Marque and Reprisal are grants of authority from Congress to private citizens, not the President. Their purpose is to expressly authorize seizure and forfeiture of goods by such citizens in the context of undeclared hostilities. Without such authorization, the citizen could be treated under international law as a pirate. Occasions where one’s citizens undertake hostile activity can often entangle the larger sovereignty, and therefore, it was sensible for Congress to desire to have a regulatory check upon it. Authorizing Congress to moderate or oversee private action, however, says absolutely nothing about the President’s responsibilities under the Constitution.

The difference between a privateer and a pirate was a subtle (often invisible) one, and the issuance of letters of marque and reprisal to private parties was banned for the signatories of the Declaration of Paris in 1856. The United States was not a signatory and is not bound by that Declaration, but did issue statements during the 1861-65 American Civil War, and during the 1898 Spanish-American War, that it would abide by the principles of the Declaration of Paris for the duration of the hostilities. The Confederate States of America did issue letters of marque and reprisal during the Civil War, however.

Examples of some famous American privateers include: