This is an old revision of this page, as edited by CheMoBot (talk | contribs) at 05:24, 19 February 2012 (Updating {{drugbox}} (changes to verified fields - added verified revid - updated '') per Chem/Drugbox validation (report errors or bugs)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:24, 19 February 2012 by CheMoBot (talk | contribs) (Updating {{drugbox}} (changes to verified fields - added verified revid - updated '') per Chem/Drugbox validation (report errors or bugs))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vibramycin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682063 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | oral, buccal, iv, im |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% |

| Metabolism | hepatic,minimally |

| Elimination half-life | 18-22 hours |

| Excretion | urine, feces |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.429 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H24N2O8 |

| Molar mass | 462.46 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

Doxycycline INN (/ˌdɒksˈsaɪkliːn/ doks-i-SY-kleen) is a member of the tetracycline antibiotics group, and is commonly used to treat a variety of infections. Doxycycline is a semisynthetic tetracycline invented and clinically developed in the early 1960s by Pfizer Inc. and marketed under the brand name Vibramycin. Vibramycin received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in 1967, becoming Pfizer's first once-a-day, broad-spectrum antibiotic. Other brand names include Monodox, Microdox, Periostat, Vibra-Tabs, Oracea, Doryx, Vibrox, Adoxa, Doxyhexal, Doxylin, Doxoral,Doxy-1 and Atridox (topical doxycycline hyclate for periodontitis).

Indicated uses

Main article: Tetracycline antibiotics Further information: OxytetracyclineAs well as the general indications for all members of the tetracycline antibiotics group, doxycycline is frequently used to treat chronic prostatitis, sinusitis, syphilis, chlamydia, pelvic inflammatory disease, acne, rosacea, and rickettsial infections.

Antiprotozoal

It is used in prophylaxis against malaria. It should not be used alone for initial treatment of malaria, even when the parasite is doxycycline-sensitive, because the antimalarial effect of doxycycline is delayed. This delay is related to its mechanism of action, which is to specifically impair the progeny of the apicoplast genes, resulting in their abnormal cell division.

It can be used in a treatment plan in combination with other agents, such as quinine.

Antibacterial

It is used in the treatment and prophylaxis of Bacillus anthracis (anthrax).

It is also effective against Yersinia pestis (the infectious agent of bubonic plague), and is prescribed for the treatment of Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. In fact, because doxycycline is one of the few medications shown to be effective in treating Rocky Mountain spotted fever (with the next-best alternative being chloramphenicol), doxycycline is indicated even for use in children for this illness. Otherwise, doxycycline is not indicated for use in children under the age of eight years. Doxycycline, like other antibiotics, will not work for colds, influenza, or other viral infections.

When bacteriologic testing indicates appropriate susceptibility to the drug, doxycycline may be used to treat and prevent:

- Escherichia coli

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- Enterobacter aerogenes (formerly Aerobacter aerogenes)

- Lyme disease, aka Lyme borreliosis complex (B. burgdorferi)

- Rocky mountain spotted fever

- Folliculitis

- Acne and other inflammatory skin diseases, such as hidradenitis suppurativa

- Shigella species

- Acinetobacter species (formerly Mima species and Herellea species)

- Respiratory tract infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae

- Respiratory tract and urinary tract infections

- Upper respiratory infections caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (formerly Diplococcus pneumoniae)

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections

- As combined therapy when treating a patient for "Chlamydia Trachomatis" because up to 50% of patients will be infected with the beta-lactam-resistant strain of this bacteria.

Anthelmintic

Elephantiasis is the end-stage condition of lymphatic filariases caused by one of two genera of filarial nematodes (roundworms): Wuchereria or Brugia (primarily Wuchereria bancrofti). Elephantiasis is characterized by permanently swollen limbs or genitals and permanent damage to the lymph system (often accompanied by severe secondary fungal and bacterial infections). This results from blockage of lymph flow caused by immune response against dead or dying adult worms in the lymphatics. This condition affects over 120 million people worldwide, with 1 billion at risk. Previous antinematode treatments have been limited by poor levels of effectiveness, drug side effects and high costs. Doxycycline was shown in 2003 to kill the symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria in the filarial worms' reproductive tracts, rendering them sterile, thus reducing transmission of the disease. Field trials in 2005 showed doxycycline almost completely eliminates the release of microfilariae when given for an eight-week course. However, doxycycline only reduces transmission and the relatively light pathology associated with microfilaraemia; there is currently no cure for lymphatic filariasis.

Cautions and side effects

Cautions and side effects are similar to those of other members of the tetracycline antibiotic group. However, the risk of photosensitivity skin reactions is of particular importance for those intending long-term use for malaria prophylaxis, because it can cause permanent sensitive and thin skin.

Unlike some other members of the tetracycline group, it may be used in those with renal impairment.

Previously, doxycycline was believed to impair the effectiveness of many types of hormonal contraception due to CYP450 induction. Recent research has shown no significant loss of effectiveness in oral contraceptives while using most tetracycline antibiotics (including doxycycline), although many physicians still recommend the use of barrier contraception for people taking the drug to prevent unwanted pregnancy.

Food, including dairy products, does not interfere with the absorption of doxycycline, unlike most other tetracycline antibiotics.

Doxycycline, like all tetracyclines, is not approved for general use in children, but specific exceptions are made for potentially fatal illnesses where the benefits outweigh the risks and there are few or no other alternatives, such as with Rocky Mountain spotted fever and anthrax.

Expired tetracyclines or tetracyclines allowed to stand at a pH less than 2 are reported to be nephrotoxic due to the formation of a degradation product, anhydro-4-epitetracycline causing Fanconi syndrome. In the case of doxycycline, the absence of an hydroxyl group in C-6 prevent the formation of the nephrotoxic compound. Nevertheless, tetracyclines and doxycycline itself have to be taken with precaution in patients with kidney injury, as they can worsen azotemia due to catabolic effects.

Experimental applications

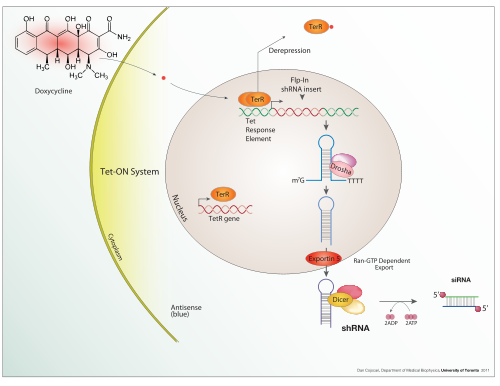

At subantimicrobial doses, doxycycline is an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteases, and has been used in various experimental systems for this purpose, such as for recalcitrant recurrent corneal erosions. Doxycycline has been used successfully in the treatment of one patient with lymphangioleiomyomatosis, an otherwise progressive and fatal disease. Doxycycline has also been shown to attenuate cardiac hypertrophy (in mice), a deadly consequence of prolonged hypertension. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, doxycycline has shown to improve lung functions in patients with stable symptoms. Doxycycline is also used in "Tet-on" and "Tet-off" tetracycline-controlled transcriptional activation to regulate transgene expression in organisms and cell cultures.

Other experimental applications include:

- Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE)

- Infected animal bite wounds (Pasteurella multocida, Pasteurella pneumotropica)

- Rheumatoid arthritis and reactive arthritis

- Chronic inflammatory lung diseases (panbronchiolitis, asthma, cystic fibrosis, bronchitis)

- Sarcoidosis

- Prevention of aortic aneurysm in people with Marfan syndrome and Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Multiple sclerosis

- Meibomian gland dysfunction

- Treatment of filariasis and onchocerciasis due to filariae and onchocercae, in general, harbouring endosymbiotic Wolbachia bacteria, doxycycline kills the bacteria, and (by removal of the endosymbiotes) the nematodes.

- New daily persistent headache

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

References

- Sweet RL, Schachter J, Landers DV, Ohm-Smith M, Robbie MO (1988). "Treatment of hospitalized patients with acute pelvic inflammatory disease: comparison of cefotetan plus doxycycline and ana doxycycline". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 158 (3 Pt 2): 736–41. PMID 3162653.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gjønnaess H, Holten E (1978). "Doxycycline (Vibramycin) in pelvic inflammatory disease". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 57 (2): 137–9. doi:10.3109/00016347809155893. PMID 345730.

- Määttä M; Kari O; Tervahartiala T; et al. (2006). "Tear fluid levels of MMP-8 are elevated in ocular rosacea--treatment effect of oral doxycycline". Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 244 (8): 957–62. doi:10.1007/s00417-005-0212-3. PMID 16411105.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - Quarterman MJ, Johnson DW, Abele DC, Lesher JL, Hull DS, Davis LS (1997). "Ocular rosacea. Signs, symptoms, and tear studies before and after treatment with doxycycline". Arch Dermatol. 133 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1001/archderm.133.1.49. PMID 9006372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dahl EL, Shock JL, Shenai BR, Gut J, DeRisi JL, Rosenthal PJ (2006). "Tetracyclines specifically target the apicoplast of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 (9): 3124–31. doi:10.1128/AAC.00394-06. PMC 1563505. PMID 16940111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lalloo DG; Shingadia D; Pasvol G; et al. (2007). "UK malaria treatment guidelines". J. Infect. 54 (2): 111–21. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2006.12.003. PMID 17215045.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Nadelman RB, Luger SW, Frank E, Wisniewski M, Collins JJ, Wormser GP (1992). "Comparison of cefuroxime axetil and doxycycline in the treatment of early Lyme disease". Ann. Intern. Med. 117 (4): 273–80. PMID 1637021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Luger SW; Paparone P; Wormser GP; et al. (1995). "Comparison of cefuroxime axetil and doxycycline in treatment of patients with early Lyme disease associated with erythema migrans". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39 (3): 661–7. PMC 162601. PMID 7793869.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Nadelman RB; Nowakowski J; Fish D; et al. (2001). "Prophylaxis with single-dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme disease after an Ixodes scapularis tick bite". N. Engl. J. Med. 345 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1056/NEJM200107123450201. PMID 11450675.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - Karlsson M, Hammers-Berggren S, Lindquist L, Stiernstedt G, Svenungsson B (1994). "Comparison of intravenous penicillin G and oral doxycycline for treatment of Lyme neuroborreliosis". Neurologe. 44 (7): 1203–7. PMID 8035916.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weinstein RS (1996). "Human ehrlichiosis". Am Fam Physician. 54 (6): 1971–6. PMID 8900357.

- Karlsson U, Bjöersdorff A, Massung RF, Christensson B (2001). "Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis--a clinical case in Scandinavia". Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 33 (1): 73–4. doi:10.1080/003655401750064130. PMID 11234985.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gladwin, Mark (2007). Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple 4th ed. Miami, FL: MedMaster Inc. p. 68. ISBN 0-940780-81-X.

- Watkins BM (2003). "Drugs for the control of parasitic diseases: current status and development". Trends Parasitol. 19 (11): 477–8. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.010. PMID 14580957.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hoerauf A; Mand S; Fischer K; et al. (2003). "Doxycycline as a novel strategy against bancroftian filariasis-depletion of Wolbachia endosymbionts from Wuchereria bancrofti and stop of microfilaria production". Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 192 (4): 211–6. doi:10.1007/s00430-002-0174-6. PMID 12684759.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); replacement character in|last9=at position 2 (help) - Taylor MJ, Makunde WH, McGarry HF, Turner JD, Mand S, Hoerauf A (2005). "Macrofilaricidal activity after doxycycline treatment of Wuchereria bancrofti: a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 365 (9477): 2116–21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66591-9. PMID 15964448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Outland, Katrina (24 June 2005). "New Treatment for Elephantitis: Antibiotics". Vol. 13. The Journal of Young Investigators.

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (November–December 2004). "European recommendations on the use of oral antibiotics for acne". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- Archer JS, Archer DF (2002). "Oral contraceptive efficacy and antibiotic interaction: a myth debunked". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 46 (6): 917–23. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120448. PMID 12063491.

- Dréno B, Bettoli V, Ochsendorf F, Layton A, Mobacken H, Degreef H (2004). "European recommendations on the use of oral antibiotics for acne" (PDF). Eur J Dermatol. 14 (6): 391–9. PMID 15564203.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - DeRossi SS, Hersh EV (2002). "Antibiotics and oral contraceptives". Dent. Clin. North Am. 46 (4): 653–64. doi:10.1016/S0011-8532(02)00017-4. PMID 12436822.

- Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics; Editors: A. G. Gilman, L. S. Goodman, T. W. Rall and F. Murad, 7th edition, MacMillan Publishing Co., New York, 1985, pp. 1170-1198

- "Principles and methods for the assessment of nephrotoxicity associated with exposure to chemicals". Environmental health criteria: 119. World Health Organization (WHO). ISBN 92 4 157119 5. ISSN 0250-863X. 1991.

- ^ Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry; David A. Williams; William O. Foye, Thomas L. Lemke

- ^ Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 12ed, Laurence L. Brunton, Bruce A. Chabner, Björn C. Knollmann

- Dursun D, Kim MC, Solomon A, Pflugfelder SC (2001). "Treatment of recalcitrant recurrent corneal erosions with inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase-9, doxycycline and corticosteroids". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 132 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(01)00913-8. PMID 11438047.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Moses MA, Harper J, Folkman J (2006). "Doxycycline treatment for lymphangioleiomyomatosis with urinary monitoring for MMPs". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (24): 2621–2. doi:10.1056/NEJMc053410. PMID 16775248.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Errami M, Galindo CL, Tassa AT, Dimaio JM, Hill JA, Garner HR (2007). "Doxycycline attenuates isoproterenol- and transverse aortic banding- induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 324 (3): 1196–203. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.133975. PMID 18089841.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dalvi PS; Singh A; Trivedi HR; et al. (2011). "Effect of doxycycline in patients of moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with stable symptoms". Ann Thorac Med. 6 (4): 221–6. doi:10.4103/1817-1737.84777. PMC 3183640. PMID 21977068.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Saraiva IH, Jones RN, Erwin M, Sader HS (1997). "". Rev Assoc Med Bras (in Portuguese). 43 (3): 217–22. doi:10.1590/S0104-42301997000300009. PMID 9497549.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dibb WL, Digranes A (1981). "Characteristics of 20 human Pasteurella isolates from animal bite wounds". Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand . 89 (3): 137–41. PMID 7315339.

- Sreekanth VR, Handa R, Wali JP, Aggarwal P, Dwivedi SN (2000). "Doxycycline in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis--a pilot study". J Assoc Physicians India. 48 (8): 804–7. PMID 11273473.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nordström D, Lindy O, Lauhio A, Sorsa T, Santavirta S, Konttinen YT (1998). "Anti-collagenolytic mechanism of action of doxycycline treatment in rheumatoid arthritis". Rheumatol. Int. 17 (5): 175–80. doi:10.1007/s002960050030. PMID 9542777.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Raza M, Ballering JG, Hayden JM, Robbins RA, Hoyt JC (2006). "Doxycycline decreases monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human lung epithelial cells". Exp. Lung Res. 32 (1–2): 15–26. doi:10.1080/01902140600691399. PMID 16809218.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chodosh S, Tuck J, Pizzuto D (1988). "Comparative trials of doxycycline versus amoxicillin, cephalexin and enoxacin in bacterial infections in chronic bronchitis and asthma". Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 53: 22–8. PMID 3047855.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bachelez H, Senet P, Cadranel J, Kaoukhov A, Dubertret L (2001). "The use of tetracyclines for the treatment of sarcoidosis". Arch Dermatol. 137 (1): 69–73. PMID 11176663.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - El Sayed F, Dhaybi R, Ammoury A (2006). "Subcutaneous nodular sarcoidosis and systemic involvement successfully treated with doxycycline". J Med Liban. 54 (1): 42–4. PMID 17044634.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Briest W, Cooper TK, Tae HJ, Krawczyk M, McDonnell NB, Talan MI (2011). "Doxycycline ameliorates the susceptibility to aortic lesions in a mouse model for the vascular type of ehlers-danlos syndrome". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 337 (3): 621–27. doi:10.1124/jpet.110.177782. PMC 3101011. PMID 21363928.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Antibiotics 'could help slow MS'". BBC News. 11 December 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- Mishra GP, Mulani JD. "Doxycycline: An Old Drug With A New Role In Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis". International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences. V1(2) 2010. ISSN 0975-6299.

External links

- Patient Information Leaflet

- Drugs.com Article on Doxycycline

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Doxycycline

| Antibacterials that inhibit protein synthesis (J01A, J01B, J01F, J01G, QJ01XQ) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30S |

| ||||||||||||||

| 50S | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Antiparasitics directed at excavata parasites (P01) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discicristata |

| ||||||||||

| Trichozoa |

| ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Antiparasitics – antiprotozoal agents – Chromalveolata antiparasitics (P01) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alveo- late |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stramen- opile | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Categories: