This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 71.202.191.160 (talk) at 01:11, 9 July 2020 (→Aftermath). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:11, 9 July 2020 by 71.202.191.160 (talk) (→Aftermath)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Part of the French intervention in Mexico Not to be confused with Siege of Puebla (1847) or Siege of Puebla (1863).| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Battle of Puebla" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Battle of Puebla | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second French intervention in Mexico | |||||||

Charge of the Mexican Cavalry at the Battle of Puebla, Francisco P. Miranda | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,500 | 6,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

83 killed 132 wounded 12 missing |

172 killed 304 wounded 35 captured | ||||||

The Battle of Puebla (Template:Lang-es; Template:Lang-fr) took place on 5 May 1862, near Puebla City during the Second French intervention in Mexico. The battle ended in a victory for the Mexican Army over the French Army. The French eventually overran the Mexicans in subsequent battles, but the Mexican victory at Puebla against a much better equipped and larger French army provided a significant morale boost to the Mexicans and also helped slow the French advance towards Mexico City.

The Mexican victory is celebrated yearly through a festival on the same date as the battle. It is primarily celebrated in the Mexican state of Puebla, where the holiday is celebrated as El Día de la Batalla de Puebla (English: The Day of the Battle of Puebla). There is some limited recognition of the holiday in other parts of the country. In the United States, this holiday has evolved into the very popular Cinco de Mayo holiday, a celebration of Mexican heritage.

Background

The Reform War of 1858 to 1860 had caused major distress throughout Mexico's economy and bitter enemies and the remaining defeated conservatives still opposed the government and were hoping for some kind of hope for their cause. When taking office as the elected president in 1861, Benito Juárez was forced to suspend payments of interest on foreign debts for a period of two years. At the end of October 1861, diplomats from Spain, France, and the United Kingdom met in London to form the Tripartite Alliance, with the main purpose of launching an allied invasion of Mexico, and ensuring the Mexican government would be willing to come to terms to negotiate terms for repaying its debts. However, the French were secretly using the alliance as a facade to invade the fractured country. In December 1861, Spanish troops landed in Veracruz; British and French troops followed in early January. The allied forces occupied Veracruz and advanced to Orizaba. However, the Tripartite Alliance fell apart by early April 1862, when it became clear the French wanted to impose harsh demands on the Juarez government and provoke a war. The British and Spanish withdrew after peacefully negotiating agreements with Juárez, leaving the French to march alone on Mexico City. The goal of Napoleon III was to set up a puppet Mexican regime in his early attempts to regain the glory of the first Empire.

Battle

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

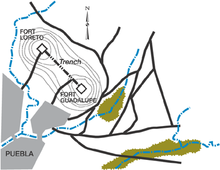

The French expeditionary force at the time was led by General Charles de Lorencez, an experienced commander who had served in Algeria and the Crimean war being promoted to Major General. The battle came about by a misunderstanding of the French agreement to withdraw to the coast. When the Mexican forces saw French soldiers on the march, they took it as a sign that hostilities had recommenced and felt threatened. To add to the mounting concerns, the Mexican forces were informed that political negotiations for the withdrawal had broken down. A vehement complaint was lodged by the Mexicans to Lorencez who took the effrontery as a plan to assail his forces. Lorencez decided to hold up his withdrawal to the coast by occupying Orizaba instead, which prevented the Mexicans from being able to defend the passes between Orizaba and the landing port of Veracruz. The Mexican Commander-general, Ignacio Zaragoza, veteran of the Reform war, fell back to Acultzingo Pass, where he and his army were defeated in a skirmish with Lorencez's forces on 28 April. Zaragoza retreated to Puebla which was heavily fortified – it had been held by the Mexican government since the Reform War. To its north stood the forts Loreto and Guadalupe on opposite hilltops. Zaragoza had a trench dug to join the forts via the saddle.

Lorencez was led to believe that the people of Puebla were friendly towards the French, and that the Mexican garrison which kept the people in line would be overrun by the population once he made a show of force. This would prove to be a serious miscalculation on Lorencez's part. On 5 May 1862, against the advice of his officers, Lorencez decided to attack Puebla from the north. However, he started his attack late in the day, using his artillery just before noon, and advancing his infantry by noon proper. In the first assault, Lorencez used his artillery to pound the forts right before launching his men. However, the stone forts held, possibly due to the fact that Lorencez positioned his artillery at a far range for a better angle. During the battle, he would move them closer but the terrain made it hard to precisely hit the forts. The French were beaten back as they were shot from above from the forts and from and around from the trenches forcing Lorencez to change his tactics.

During the second assault, Lorencez planned to make a diversionary attack to the east of the city to draw off the attention and defenders of the forts. The French artillery once again began a bombardment on the forts and the French soldier once again launched their assault. The send attack proved more successful as one Frenchman managed to raise the tricolor flag on the wall of fort Guadalupe. However, he was then immediately killed as his fellow soldiers were beaten back from the forts. The early diversionary attack was also beaten back in melee combat.

By the third assault the French required the full engagement of all their reserves. The French artillery had run out of ammunition but Lorencez was unwilling to concede defeat yet, so the third infantry attack was ordered without any supporting fire. The Mexican forces put up a stout defense and even took to the field to defend the positions between the hilltop forts.

As the French retreated from their final assault, Zaragoza, possibly guessing that the French artillery was spent as the third assualt came with no initial shell fire, had his cavalry attack them from the right and left while troops concealed along the road pivoted out to flank them. Against the orders of his commander, General Porfirio Diaz ordered his brigade forward and his calvary helped push back the French. By 3 p.m. the daily rains had started, making a slippery slope of the battlefield. Lorencez withdrew to distant positions, counting 172 of his men killed against only 83 of the Mexicans. He waited a couple of days for Zaragoza to attack again, but Zaragoza held his ground knowing that an open field battle with the French was a guaranteed defeat. Lorencez then withdrew to Orizaba.

Aftermath

The Battle of Puebla was an inspirational event for Mexico during the war, and it proved a stunning revelation to the rest of the world which had largely expected a rapid victory for French arms. General Zaragoza would not live long enough to celebrate the victory as he passed away 4 months later due to tyhpid fever.

Slowed by their loss at Puebla, the French forces retreated and regrouped, and the invasion continued after Napoleon III determinedly sent additional troops to Mexico and dismissed General Lorencez. The French were eventually victorious, winning the Second Battle of Puebla on 17 May 1863 and pushing on to Mexico City. When the capital fell, Juárez's government was forced into exile in the remote northern parts of Mexico.

With the backing of France, the Habsburg Archduke Maximilian became Emperor of Mexico of the short-lived Second Mexican Empire as by the time that the puppet regime had been created, the United States would be more able to support Juárez turning the tide of the war.

Celebration

On 9 May 1862, President Juárez declared that the anniversary of the Battle of Puebla would be a national holiday, regarded as "Battle of Puebla Day" or "Battle of Cinco de Mayo".

A common misconception in the United States is that Cinco de Mayo is Mexico's Independence Day, the most important national patriotic holiday in Mexico. Mexico celebrates Independence Day on the 16th of September, commemorating the beginning of the war of Independence (September 16, 1810, the "Cry of Dolores"). Mexico also observes the culmination of the war of Independence, which lasted 11 years, on 27 September.

Since the 1930s, a re-enactment of the Battle of Puebla has been held each year at Peñón de los Baños, a rocky outcrop close to Mexico City International Airport.

See also

- List of battles of the French intervention in Mexico

- Monument for the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Puebla

References

- ^ Christopher Minster (2011). "Latin American history: Cinco de Mayo/The Battle of Puebla". About.com. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Booth, William (5 May 2011). "In Mexico, Cinco de Mayo a more sober affair". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "Cinco de Mayo". Mexico Online. 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

- DeRouen, Karl R.; Heo, Uk (2005). Defense and security: a compendium of national armed forces and security policies. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 472. ISBN 978-1-85109-781-4. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- The following sources are mentioning that Zaragoza was heading 12,000 troops : see The Cinco de Mayo and French Imperialism – Hicks, Peter, Fondation Napoléon, and General Gustave Léon Niox book, Expédition du Mexique : 1861–1867, published in 1874 by Librairie militaire de J. Dumaine, p. 162 Read online

- "Cinco de Mayo". Mexico Online: The Oldest and most trusted online guide to Mexico.

- Lovgren, Stefan (2006-05-05). "Cinco de Mayo, From Mexican Fiesta to Popular U.S. Holiday". National Geographic News.

- List of Public and Bank Holidays in Mexico Archived 2009-04-16 at the Wayback Machine April 14, 2008. This list indicates that Cinco de Mayo is not a día feriado obligatorio ("obligatory holiday"), but is instead a holiday that can be voluntarily observed.

- Cinco de Mayo is not a federal holiday in México Accessed May 5, 2009

- Día de la Batalla de Puebla. 5 May 2011. "Dia de la Batalla de Puebla: 5 de Mayo de 1862." Archived 24 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Colegio Rex: Marina, Mazatlan. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- Día de la Batalla de Puebla (5 de Mayo). Guia de San Miguel. Archived 2012-05-12 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- Happy “Battle of Puebla” Day. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ Beezley, William H. (2011). Mexico in World History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-19-515381-1. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- Did You Know? Cinco de Mayo is more widely celebrated in USA than Mexico. Tony Burton. Mexconnect. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- Cultural adaptation: the Cinco de Mayo holiday is far more widely celebrated in the USA than in Mexico. Geo-Mexico. 2 May 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- 25 Latino Craft Projects: Celebrating Culture in Your Library. Ana Elba Pabon. Diana Borrego. 2003. American Library Association. Page 14. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- 7 Things You May Not Know About Cinco de Mayo. Jesse Greenspan. May 3, 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- Congressional Record – House. p. 7488. May 9, 2001. Retrieved 29 April 2013. Note that contrary to most other sources, this source states the date Juarez declared Cinco de Mayo to be a national holiday was 8 September 1862.

- Statement by Mexican Consular official Accessed May 8, 2007.

- Adam Brooks. "Is Cinco De Mayo Really Mexico's Independence Day?". NBC 11 News. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2011). "The World Factbook: Mexico". CIA. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- Geo-Mexico (2010). "The Battle of Puebla is re-enacted each year on Cinco de Mayo (May 5), but in Mexico City". Geo-mexico.com. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

External links

- French Intervention in Mexico: Battle of Puebla

- Phil's Findings: Did Battle of Puebla change the course of U.S. history? by Philip A. Rue

19°03′00″N 98°12′00″W / 19.0500°N 98.2000°W / 19.0500; -98.2000

Categories: