This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Tokerdesigner (talk | contribs) at 20:31, 11 March 2009. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:31, 11 March 2009 by Tokerdesigner (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

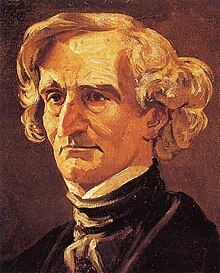

A choral symphony is a large musical composition, generally including an orchestra, a choir and soloists, which adheres to some extent to the tenets of musical form for a symphony in its internal workings and overall musical architecture. The term "choral symphony" in this context was coined by Hector Berlioz when describing his Roméo et Juliette in his five-paragraph introduction to that work.

The direct antecedent for the choral symphony is Ludwig van Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. The Beethoven Ninth incorporates part of the Ode an die Freude ("Ode to Joy"), a poem by Friedrich Schiller, with text sung by soloists and a chorus in the last movement. It is the first example of a major composer using the human voice on the same level with instruments in a symphony. Even after taking this step, Beethoven wondered if he had made the right decision. Concerned that having words and voices in a symphony abrogate the rules governing that genre, he considered replacing the choral ending with a purely instrumental one. He eventually concluded that instead of limiting the meanings implied by the music, the words became a prime vehicle for enlarging the music's meaning.

While Berlioz and Franz Liszt followed in Beethoven's footsteps, it was with the advent of the 20th century that the choral symphoy seemed to come into vogue, with notable works by Benjamin Britten, Gustav Mahler, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Dmitri Shostakovich, Igor Stravinsky and Ralph Vaughan Williams, among others. In most of these works their composers strove to perserve more than a semblance of symphonic form; and while the size and scope of written texts grew to encompass an entire composition, parity was maintained between words and text and vocal and instrumental forces.

Moreover, the intent for the choral symphony to remain symphonic rather than narrative or dramatic meant that the words were to be treated symphonically as well, with frequent repetition of important words and phrases and transposing, reording and omission of passages to pursue purely non-narrative ends. The text came to determine not only tone, but also the basic symphonic outline for the composition to follow, while the orchestra maintained an equal share with the chorus and soloists in carrying out the musical ideas.

Overview

True to symphonic form

Choral symphonies, unlike the Beethoven Ninth, can utilize text settings, choruses and sometimes soloists throughout their compositions, not in just one or two sections; Gustav Mahler's Eighth Symphony, written in 1906-1907, was the first to do this, followed in 1909 by Ralph Vaughan Williams' A Sea Symphony. Both these works justified their status as symphonies, having been symphonically conceived and remaining true to symphonic form after their subsequent conceptions. Berlioz attempted to explain as much years earlier regarding Roméo et Juliette:

Even though voices are often used, it is neither a concert opera nor a cantata, but a choral symphony.

If there is singing, almost from the beginning, it is to prepare the listener's mind for the dramatic scenes whose feelings and passions are to be expressed by the orchestra. It is also to introduce the choral masses gradually into the musical development, when their too sudden appearance would have damaged the compositions's unity .....

As in both opera and oratorio, the text helps serve both musical and programmatic ends. The difference between the choral symphony and these other genres is in their overall forms. The oratorio was somewhat modeled after the opera. Their similarities include the use of a choir, soloists, an ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. The choral symphony, conversely, remains essentially a symphony. It can (but not necessarily) utilize sonata form and have a similar ordering of movements as a purely orchestral symphony. Even when the number of movements are extended, as is the case with Berlioz' Roméo, as long as the form remains essentially symphonic, it does not cross from symphony in to oratorio, even if the form itself has been extended. As Robert Collet wrote about Berlioz, the line between his dramatic works for the stage and his dramatic works for the concert platform may have been a fine one, but the composer knew where to draw it.

Music and words as equals

Like the oratorio, however, the written text shares equal standing with the music, just as the chorus and soloists share equality with the instruments. Igor Stravinsky phrased this point succinctly when he said about the texts of his Symphony of Psalms that "it is not a symphony in which I have included Psalms to be sung. On the contrary, it is the singing of the Psalms that I am symphonizing." This decision was as much musical as it was textual. Stravinsky wanted to employ considerable counterpoint in his symphony. To facilitate doing so he chose to use "a choral and instrumental ensemble in which the two elements should be on an equal footing, neither of them outweighing the other." This desire for balance and unity informs the symphony's texts as well as its music. The 39th Psalm of the second movement is like an answer to the 38th Psalm of the first movement, while the Alleluia which begins the 150th Psalm in the third movement likewise answers the 39th Psalm which precedes it. The work maintains both the force of formal thrust and overall unity of material dictated by the symphony.

A desire for balance was also Mahler's intent in writing his Eighth Symphony for exceptionally large forces. Though the composer's doing so earned the work the subtitle "Symphony of a Thousand" from his press agent (a soubriquet which has stuck to the symphony to the present day), Mahler's aim was not pure grandiosity but to maintain as perfect a balance between voices and instruments as possible. This is something of which he would have had considerable experience from working as an opera conductor nearly all of his adult life. Like Stravinsky, Mahler employs these forces on an extensive and extended use of counterpoint, especially in the first movement, "Veni Creator Spiritus." This movement, which owes much in its use of polyphony to Mahler's study of cantatas by Johann Sebastian Bach, is an extended sonata structure in E-flat.

Vaughan Williams also insisted on a balance between words and music. Though it was Walt Whitman's poems that inspired him to write A Sea Symphony, and beginning as "songs of the sea" in emulation of the works of Charles Villiers Stanford, it became Vaughan-Williams' intent to set them within symphonic bounds and stay within the four-movement norm. As the composer wrote in the program notes for the symphony,

The plan of the work is symphonic rather than narrative or dramatic, and this may be held to justify the frequent repetition of important words and phrases which occur in the poem. The words as well as the music are thus treated symphonically. It is also noticeable that the orchestra has an equal share with the chorus and soloists in carrying out the musical ideas.

Although it represents a departure from the traditional Germanic symphonic tradition of the time, A Sea Symphony follows a fairly standard symphonic outline, as suggested by the orchestral symphony: fast introductory movement, slow movement, scherzo, and finale. While the shape of the first movement is governed by the words of the text, it is recognizably in sonata form. Similarly, the slow movement is in ternary form. Vaughan Williams employs two traditional sea songs in the scherzo, which is in the usual binary form, with trio. Only the final movement employs a free and unsymphonic form, following the text's Whitmanesque journey of the soul into the unknown.

Nevertheless, the words also had their influence throughout the symphony. Whitman's poems attracted Vaughan Williams by their ability to transcend both metaphysical and humanist perspectives, and the poet's emphasis on the unity of being and the brotherhood of man comes through strongly. Whitman's use of free verse was also beginning to make waves in the compositional world, where fluidity of structure was beginning to be more attractive than traditional, metrical settings of text. This fluidity helped facilitate the non-narrative, symphonic treatment of text that Vaughan Williams had in mind. Especially in the scherzo, because the text is loosely descriptive, lines could follow the demands of the music in being detached, cobbled together and repeated.

Most notably, the physical exultation characteristic of Whitman's poetry produced a grandiloquence and musical poetry as unexpectedly direct as the words. This was even more apparent when comparing the symphony to the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis. Written at roughly the same period, the Fantasy shows taut and strict control of material in marked contrast to the expansiveness of the symphony. The symphony is also profuse in melodic invention; it has enough tunes in its four movements for other composers to write at least three symphonies.

Gustav Holst was to take a similar approach as Vaughan Williams when he composed his First Choral Symphony in 1924. Utilizing a text based on several (unrelated) poems by John Keats, Holst structured the work to follow the traditional outline of the four-movement symphony, with the choral parts fully integrated into the aural texture of the work instead of standing out independently as an extra element.

Words determining symphonic form

The text can determine not only tone, but also the basic symphonic outline for the composition to follow. With Sergei Rachmaninoff the four-part structure of Edgar Allan Poe's The Bells, as translated by Russian symbolist poet Konstantin Balmont, naturally suggested the four movements of a symphony with its outline of the circle of life: youth, marriage, maturity, and death. Rachmaninoff follows this pattern not just in general outline but also in tone and orchestration: treble instruments for the sleigh bells of youth; muted violins for the golden bells of marriage in the slow movement; and lower instruments, reminiscent of the final movement of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Pathétique Symphony, for the iron tone of funeral bells in the finale. By following this progression, Rachmaninoff heightens the impact of the finale by its contrast with the other three, more vivid movements. Benjamin Britten follows a similar overall pattern, though reversed, for his Spring Symphony, with the four sections of the symphony representing, in its composer's words, represents "the progress of Winter to Spring and the reawakening of the earth and life which that means." Part I begins with the dark and mysterious Shine Out, a poem to the sun. The second part has several solos and quiet choruses and references to the month of May. The third part looks forward to May and then to summer. The Finale, London, to Thee I do Present, is most notable, with its crowning glory being when the children's voices sing the 13th century round Sumer is icumen in.

The gestation of Dmitri Shostakovich's Thirteenth Symphony, Babi Yar, was only slightly less straightforward. He set the poem Babi Yar by Yevgeny Yevtushenko almost immediately upon reading it. He initially considered keeping this work as a single-movement composition. What changed his mind was discovering three other Yevtushenko poems in the poet's collection Vzmakh ruki (A Wave of the Hand). These additional poems prompted him to proceed to a full-length choral symphony, with "A Career" as the closing movement. Shostakovich did so by complementing Babi Yar's theme of Jewish suffering with Yevtushenko's verses about other Soviet abuses. "At the Store" is a tribute to the women who have to stand in line for hours to buy the most basic foods. "Fears" invokes the terror under Stalin. "A Career" is an attack on bureaucrats and a tribute to genuine creativity. Yevtushenko wrote "Fears" at the composer's request.

While inevitably much of the emphasis surrounding the Thirteenth Symphony is focused on its text, the musical language and codes Shostakovich employs are immediately familiar. Power is represented by thudding two-note fortes, the People by threes. While Shostakovich quotes amply from his earlier compositions, especially the Sixth String Quartet, the work on the whole does not come across as tightly-knit a piece of music as his instrumental Fourth Symphony; it actually receives more unity as a composition from its text. Nonetheless, the poems form a perfect symphonic cycle—a strongly dramatic opening movement followed by a scherzo, two slow movements and a finale—with the music, while inhabiting a life and logic of its own, remaining closely welded to the texts.

Words expanding symphonic form

The text can also encourage a composer to expand a choral symphony past the normal bounds for the genre of the symphony. Berlioz intended to follow a design much like Beethoven's Ninth Symphony for his Roméo et Juliette, only with four instrumental movements instead of three before the choral finale. This would have also placed it within the same formal scheme overall as Berlioz' Symphonie fantastique. While he still considered the musical structure to hew to this plan, he overlaid "extra" movements to fill out the drama illustrated in the work. As a result, the symphony is actually in seven movements. He also calls for an intermission after the fourth movement, the "Queen Mab Scherzo", to remove the harps from the stage and bring on the chorus of Capulets for the funeral march which follows.

While some critics have argued similarly that Mahler allowed his text for the Eighth Symphony to dictate his writing the piece in two movements, this is actually not the case. He merely telescoped slow movement, scherzo and finale into one continuous movement.

Symphonic form without symphonic argument

While composers of choral symphonies have many times hewed to the four-movement form or some equivalent of it, they have not always felt as obligated to follow the symphony's traditional philosophical discourse of contrast, conflict and resolution. Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms, while containing the force of a symphony in its formal thrust and unity of material, does not attempt any conventional symphonic process of conflict or resolve. As phrased in the 2001 edition of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, "The substance of things hoped for is, already, for Stravinsky as for St. Paul, faith; and it is the music's neo-Baroque religious symbolism, its fugues and spiraling ostinatos, that supply both the power and, ultimately, the stability ." In this sense, the Symphony of Psalms is not indebted to traditional symphonic thought.

Likewise, while Britten kept to the formal outline of the symphony in his Spring Symphony, he saw no reason to produce a traditional symphonic "argument"; instead, he wanted to project a series of controlled gestures in four distinct parts, the inner two corresponding to a scherzo and slow movement and with a single poem for the more extended, joyous finale. The separate text settings build cumulatively in feeling and climactic in structure, an effect Britten mastered through his operas. The result is a building-up of tensions from an introductary movement in ritornello form, more consistent with Baroque affectation than Romantic argument, to the climactic peoration of Sumer is icumin in.

Programmatic versus symphonic

Beethoven

Even with a balance between words and music, the question arose whether having words and voices in a symphony abrogated the rules governing that genre. Beethoven thought that perhaps this was so, even intending to discard the choral ending to his Ninth Symphony and replace it with a purely instrumental one.

Part of the quandary for Beethoven was the direction in which his compositional style was heading. His finales during his late period had extended far beyond the normal parameters of classical form. It was as though he were elaborating the limitless variety of endings his mind could create, in a dizzying display of his creative powers. At the same time, his ever-present skepticism warred with his will to affirm and transcend; no matter what the symbolic affirmation, doubt survived. Beethoven may have been becoming convinced that his colossal endings were overwhelming the works they were intended to crown, throwing off classical balance and intruding compositional and dramatic issues normally reserved for earlier movements of a sonata style. The Grosse Fuge is just one case in point.

There was also the nature of written text, which was verbal and philosophical rather than musical. Even if the "Ode to Joy" satisfied Beethoven's prophetic and apocalyptic intent by showing Elysium after surviving storm and chaos (Gesamtkunstwerk ), by doing so with words he ran the risk of diluting the power of sound and narrowing the range of the music's potential meanings. By introducing a choral finale, he seemed to advance Richard Wagner's assertion on the inferiority of music: "'Where music can go no farther, there comes the word' (the word stands higher than the tone)."

Moreover, the narrowing of musical meanings seemed to also introduce the question of considering the earlier movements as ideological constructs rather than as music. The instrumental finale Beethoven contemplated for his Ninth would have sidestepped the ideological diminution of the choral finale, along with the Gestamtkunstwerk conception and denotational vocabulary, leaving music's expressive powers unhindered.

Eventually, Beethoven realized that he had underestimated the achievement he had won—that, rather than fixing or limiting the meanings implied by the music, the text became a prime vehicle for enlarging the music's meaning.

Berlioz

Rather than question how a text might show music inferior to it, Berlioz instead showed how an orchestra could supplant a text wordlessly to expand meaning—not just any text, but Shakespeare. He wrote in his preface to Roméo:

If, in the famous garden and cemetery scenes the dialogue of the two lovers, Juliet's asides, and Romeo's passionate outbursts are not sung, if the duets of love and despair are given to the orchestra, the reasons are numerous and easy to comprehend. First, and this alone would be sufficient, it is a symphony and not an opera. Second, since duets of this nature have been handled vocally a thousand times by the greatest masters, it was wise as well as unusual to attempt another means of expression. It is also because the very sublimity of this love made its depiction so dangerous for the musician that he had to give his imagination a latitude that the positive sense of the sung words would not have given him, resorting instead to instrumental language, which is richer, more varied, less precise, and by its very indefiniteness incomparably more powerful in such a case.

As a manifesto, this paragraph became more significant than its author could have imagined for the amalgamation of symphonic and dramatic elements in the same composition. While Berlioz planned initially for Roméo to follow the same pattern as Beethoven's Ninth and adhere to symphonic ideals stringently, he had to break with those ideals and sonata-style organization as he progressed on the work. He found strophic forms and free sectionality more congenial to the dramatic purposes he had in mind. He achieved balance and coherence by a musico-dramatic framing similar to that he had used for his Grande Messe des morts (Requiem). He reprises the opening instrumental "swordplay" used to illustrate the warring Montagues and Capulets and maintains a clear formal balance beginning the opening strophes and Friar Lawrence's aria in the last scene.

Despite this expansion past the classical boundaries of the symphony for dramatic purposes, Roméo remained indebted structurally and musically to Beethoven's Ninth. This was due not just due to the use of soloists and choir, but in Berlioz' keeping the weight of the vocal contribution in the finale, and also in aspects of the orchestration such as the theme of the trombone recitative at the Introduction. At its core, the composer felt, Roméo remained Beethovenian in scope and design, with the exception of including both a scherzo and a march as he had in the Symphonie Fantastique. The "extra" movements—the introduction with its potpourri of subsections and the concluding tomb scene—functioned merely as bookends for the drama.

By keeping the idea of symphonic construction closely in mind, Berlioz was able (per his manifesto) to express the main portion of the drama in instrumental music while setting the more expository sections and narrative sections in words. The three principally instrumental sections—"Fête chez Capulet", "Scène d'amour" and "La reine Mab"—can be considered the equivalent of first movement, slow movement and scherzo. At the same time, he succeeded in creating a new model in which a dramatic text became an essential guiding element in the structure of a composition while not hindering that work from being recognizably a symphony.

Liszt

The most important choral symphoinies immediately following Berlioz may have been the two of Franz Liszt. There is no doubt as to Berlioz's connection with Liszt's Faust Symphony; it was Berlioz who introduced Liszt to Goethe's Faust and had shown in his La Damnation de Faust how well suited the subject could be to musical development. Nevertheless, both Faust and its sister symphony Dante were conceived as purely instrumental works and only later became choral symphonies.

Liszt's inclusion of a choral finale in the revised version of his Faust can be said to effectively sum up the work and make it complete. However, in doing so, Liszt arguably changed the work's dramatic focus to the point of meriting a different interpretation of the work itself. Liszt's original version of 1854 ended with a last fleeting reference to Gretchen and an optimistic peoration in C major, based on the most majestic of themes from the opening movement. Some critics suggest this conclusion remains within the persona of Faust and his imagination. When Liszt rethought the piece three years later, he added a 'Chorus mysticus', tranquil and positive. The male chorus sings the final words from Goethe's Faust. The tenor soloist then rises above the murmur of the chorus and starts to sing the last two lines of the text, emphasizing the power of salvation through the Eternal Feminine. The symphony ends in a glorious blaze of the choir and orchestra, backed up by held chords on the organ. With this direct association to the final scene of Goethe's drama we escape Faust's imaginings and hear another voice commenting on his striving and redemption.

Likewise, Liszt's inclusion of a choral finale in his Dante Symphony changed both the symphonic and programmatic intent of the work. Following the structure of the Divina Commedia, Liszt's intention was to compose Dante in three movements—one each for the Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso. However, Liszt's son in law Richard Wagner persuaded him that no earthly composer could faithfully express the joys of Paradise. Liszt dropped the third movement but added a choral Magnificat at the end of the second. This action, some critics claim, effectively destroyed the work's balance, leaving the listener, like Dante, gazing upward at the heights of Heaven and hearing its music from afar. Others suggest that the choral finale actually helps complete the work's programattic trajectory from struggle to paradise.

Shostakovich

A text can also spark the birth of what may initially seem a choral symphony, only for that work to become a purely instrumental one, with symphonic concerns overriding dramatic ones. Shostakovich originally planned his Seventh Symphony as a single-movement choral symphony much like his Second and Third Symphonies. Rather than the blatantly agitprop sentiments in the texts of those works, however, Shostakovich reportedly intended with the Seventh to set a text from the Ninth Psalm on the avengement of innocent blood shed. He was also influenced by Stravinsky in doing so; he had been deeply impressed with the latter's Symphony of Psalms, which he wanted to emulate in this work. While the theme of vengeance for innocent blood conveyed Shostakovich's outrage over Stalin's oppression,, a public performance of a work with such a text would have been impossible before the German invasion. Hitler's aggression made the performance of such a work feasible, at least in theory, with the reference to "blood" applied at least officially to Hitler. With Stalin appealing to the Soviets' patriotic and religious sentiments, the authorities were no longer suppressing Orthodox themes or images. Nevertheless, Shostakovich eventually realized that the work encompassed far more than this symbology. He expanded the symphony to the traditional four movements and made it purely instrumental. He also may have been right in writing the symphony without a text, in view of the censorship that he may have felt would eventually be reimposed.

Mahler

Second Symphony

Not only was there no schism or discrepancy between programmatic and symphonic concerns when it came to Mahler's Second Symphony, the Resurrection, but it became a programmatic impetus that allowed him to complete it. It had begun as a huge single-movement tone poem, Totenfeier (Funeral Rite), remaining one of the composer's most imposing symphonic structures, unorthodox in tonal organization but unambiguously and even classically articulated. It also left him stuck with the challenge of how to follow such a movement. While there was a time lag between its composition and that of the finale, with its setting of Klopstock's "Resurrection Ode", there is no discontinuity. On the contrary, the final movement complements the opening one.

Third Symphony

Even with its program, the Second Symphony followed the Beethovenian pattern of three instrumental movements and a choral finale (the fourth movement, Urlicht, being a bridge from slow movement to finale). The Third Symphony broke from this pattern. Two movements for voices and orchestra follow three purely instrumental ones, then return to instruments alone for the finale. The progress of movements make sense only in a programmatic one. Both the first and final movements are huge, flanking what are essentially intermezzi which themselves frame weightier episodes discussing "animals" and "mankind." But with the finale, originally titled "What Love Tells Me", (and in this case he was talking about agape or godly love,) some might think Mahler took a hint from Berlioz about instruments sometimes being more eloquent than voices.

Eighth Symphony

Initially, Mahler planned for the Eighth Symphony to have four movements:

- Veni, Creator Spiritus

- Caritas

- Scherzo: Christmas Games with the Christ Child

- This movement would have included two songs from "Des Knaben Wunderhorn"

- Creation through Eros (Hymn)

What the sketches for these movements did not have were words; though the opening theme was articulated to fit the words "Veni, creator spiritus", Mahler may have planned this work to be purely instrumental. Mahler dated these sketches "Aug. 1906." Somewhere in the eight weeks which followed, Mahler replaced the contemplated hymn to Love with a similar idea based on the closing scene in Part II of Goethe's Faust, with the ideal of salvation through the eternal womanhood (das Ewige-Weibliche). He interrupted his holiday to conduct The Marriage of Figaro at the Salzburg Festival. There, critic Julius Korngold spotted a well-thumbed copy of Faust protruding from his coat pocket.

The dramatic and intellectual plan for the symphony would affect both its content and its overall musical structure—affirming Goethe's symbolic vision of the redemptive power of human love, eros, while linking it in "Veni, Creator Spiritus" to both the creative spirit who inspires the artist and God the Creator who endows the artist with creativity. As Mahler wrote to his wife Alma,

The essence ... is really Goethe's idea that all love is generate, creative, and that there is a a physical and spiritual generation which is the emanation of this "Eros." You have it in the last scene of Faust, presented symbolically. The wonderful discussion between Diotima and Socrates ... gives the core of Plato's thought, his whole outlook on the world... The comparison between and Christ is obvious and has arisen spontaneously in all ages ... In each case Eros as Creator of the world.

As the composer took a non-narrative approach to expressing a personal philosophical idea, the symphony metamorphosed from being completely instrumental to completely choral, becoming the first completely choral symphony to be written. Not just the choice of text became crucial to convey Mahler's intentions, but even the way in which he chose to set it. "Veni, creator spiritus" ("Come, creator spirit") might as well have read "come, creative spirit" since the music for it reportedly came at such a white heat of inspiration.. Yet in a 1906 conversation with Richard Specht, the composer confirmed that the music, not the text, had remained paramount:

"This Eighth Symphony is noteworthy for one thing, because it combines two works of poetry in different languages. The first part is a Latin hymn and the second nothing less than the final scene of the second part of Faust...Its form is also something altogether new. Can you imagine a symphony that is sung throughout, from beginning to end? So far I have employed words and the human voice merely to suggest, to sum up, to establish a mood...But here the voice is also an instrument. The whole first movement is strictly symphonic in form yet is completely sung...the most beautiful instrument of all is led to its calling. Yet it is used only as sound, because the voice is the bearer of poetic thoughts."

Mahler's treatment of what he considered "the cardinal point of the text" and the bridge from "Veni, Creator Spiritus" to Faust—that is, "Accende lumen sensibus" ("Kindle our Reason with Light")—show us how he intended to treat the text as music, to be manipulated as needed. While his first statement of this line by the soloists is quiet, the word order is reversed—"Lumen accente sensibus", or literally "Light, Kindle with Reason." The great outburst with all voices in unison, including those of children, coincides with the first presentation of the line in its proper order. The change there of texture, tempo and harmony make this the most dramatic stroke in the symphony. Likewise, he presents other lines of "Veni, Creator Spiritus" in a tremendously dense growth of repetitions, combinations, inversions, transpositions and conflations. He does the same with Goethe's text. There he makes two substantial cuts, one of 37 lines and another of seven, presumably on purpose, along with other omissions, inversions and altered word forms.

List of choral symphonies

Symphonies for chorus and orchestra

Works are listed in chronological order. Works with an asterisk (*) indicate that text is used throughout the entire composition.

- Symphony No. 9 in D minor, opus 125, by Ludwig van Beethoven (1824)

- Roméo et Juliette, opus 17, by Hector Berlioz (1835)

- Symphony No. 2 in B-flat major, opus 52, Lobgesang, by Felix Mendelssohn (1840)

- Faust Symphony, by Franz Liszt (1854)

- Dante Symphony, by Franz Liszt (1856)

- Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Resurrection, by Gustav Mahler (1894)

- Symphony No. 3 in D minor, by Gustav Mahler (1896)

- Symphony No. 1 in E major, opus 26, by Alexander Scriabin (1900)

- Symphony No. 3, by Joseph Guy Ropartz (1905)

- Symphony No. 8 in E-flat major, by Gustav Mahler (1907) *

- A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1), by Ralph Vaughan Williams (1909) *

- The Bells, opus 35, by Sergei Rachmaninoff (1913) *

- Symphony No. 4, by Charles Ives (1916)

- Symphony No. 3, opus 27, Song of the Night, by Karol Szymanowski (1916)

- A Symphony: New England Holidays, by Charles Ives (1919)

- Symphony No. 3 in C major, opus 21, by George Enescu (1921)

- First Choral Symphony, by Gustav Holst (1924)

- Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Gothic, by Havergal Brian (1927)

- Symphony No. 2 in B major, opus 14, To October, by Dmitri Shostakovich (1927)

- Symphony No. 2, O Holy Lord, by Jan Maklakiewicz (1928)

- Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, opus 20, The First of May, by Dmitri Shostakovich (1929)

- Morning Heroes, by Arthur Bliss (1930) *

- Symphony of Psalms, by Igor Stravinsky (1930) *

- Symphony No. 4, Das Siegeslied, by Havergal Brian (1933) *

- Symphony No. 3, The Muses, by Cyril Scott (1937)

- Symphony No. 4, Folksong Symphony, by Roy Harris (1940)

- Symphony No. 4, The Revelation of Saint John, by Hilding Rosenberg (1940)

- Symphony No. 6, by Erwin Schulhoff (1940)

- Den judiska sången, by Moses Pergament (1944)

- Symphony No. 6, In Memoriam, by Alexandre Tansman (1944)

- Symphony No. 5, The Keeper of the Garden, by Hilding Rosenberg (1945)

- Odysseus (Symphony No. 2), by Cecil Armstrong Gibbs (first performed 1946)

- Symphony No. 3, Te Deum, by Darius Milhaud (1946)

- Spring Symphony, by Benjamin Britten (1947) *

- Symphony No. 5, by Dimitrie Cuclin (1947)

- Symphony No. 4, The Cycle, by Peter Mennin (1948)

- Symphony No. 10, by Dimitrie Cuclin (1949)

- Symphony No. 12, by Dimitrie Cuclin (1951)

- Sinfonia Antartica (Symphony No. 7), by Ralph Vaughan Williams (1952)

- Symphony No. 9, opus 54, Sinfonia Visionaria, by Kurt Atterberg (1956) *

- Deutsche Sinfonie, by Hanns Eisler (1957) *

- Symphony No. 12, opus 188, Choral, by Alan Hovhaness (1960)

- Symphony No. 13 in B-flat minor, opus 113, Babi Yar, by Dmitri Shostakovich (1962) *

- Symphony No. 3, Kaddish, by Leonard Bernstein (1963)

- Symphony No. 10, Abraham Lincoln, by Roy Harris (1965)

- Vocal Symphony, by Ivana Loudová (1965)

- Choral Symphony, by Jean Coulthard (1967)

- Symphony No. 2, opus 31, Copernicus, by Henryk Górecki (1972) *

- Symphony No. 9 (Sinfonia Sacra), opus 140, The Resurrection, by Edmund Rubbra (1972) *

- Symphony No. 3, The Icy Mirror, by Malcolm Williamson (1972) *

- Symphony No. 23, opus 273, Majnun, by Alan Hovhaness (1973)

- Symphony No. 2, Sinfonia mistica, by Kenneth Leighton (1974)

- Symphony No. 13, Bicentennial Symphony, by Roy Harris (1976)

- Symphony No. 5, by Camargo Guarnieri (1977)

- Symphony No. 7, A Sea Symphony, by Howard Hanson (1977) *

- Sinfonia fidei, opus 95, by Alun Hoddinott (1977)

- Symphony No. 2, Saint Florian, by Alfred Schnittke (1979)

- Harmonium, by John Adams (1981) *

- Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia da Requiem, by József Soproni (1983)

- Symphony No. 6, Aphorisms, by Einar Englund (1984)

- Symphony No. 4, by Alfred Schnittke (1984)

- Symphony No. 58, Sinfonia Sacra, opus 389, by Alan Hovhaness (1985)

- Symphony No. 2, by Erkki-Sven Tüür (1987)

- The Dawn Is at Hand, by Malcolm Williamson (1987-89) *

- Symphony No. 3, Journey without Distance, by Richard Danielpour (1989) *

- Symphony No. 7, opus 116, The Keys of the Kingdom, by Jan Hanuš (1990)

- Symphony No. 7, Seven Gates of Jerusalem, by Krzysztof Penderecki (1996)

- Symphony No. 6, Choral, by Carl Vine (1996) *

- Symphony No. 9, by Hans Werner Henze (1997) *

- Symphony 1997: Heaven - Earth - Mankind, by Tan Dun (1997)

- Symphony No. 5, Choral, by Philip Glass (1999) *

- Symphony No. 4, The Gardens, by Ellen Taaffe Zwilich (1999)

- Symphony No. 9, The Spirit of Time, by Robert Kyr (2000)

- Symphony No. 7, Toltec, by Philip Glass (2005) *

- Symphony No. 8, Songs of Transitoriness, by Krzysztof Penderecki (2005)

Symphonies for unaccompanied chorus

Works are listed in chronological order. These works are scored without orchestra, but the composers nevertheless titled or sub-titled them as symphonies.

- Atalanta in Calydon, by Granville Bantock (1911)

- Vanity of Vanities, by Granville Bantock (1913)

- A Pageant of Human Life, by Granville Bantock (1913)

- Symphony for Voices, by Roy Harris (1935)

- Symphony for Voices, by Malcolm Williamson (1962)

Bibliography

- Carr, Jonathan. Mahler—A Biography. Woodstock and New York: The Overlook Press, 1997. ISBN 0-87951-802-2.

- ed. Hamilton, Kenneth, The Cambridge Companion to Liszt. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-64462-3 (paperback).

- Shulstad, Reeves, "Liszt's symphonic poems and symphonies"

- Holoman, D. Kern. Berlioz. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-674-06778-9.

- Kennedy, Michael. The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1964.

- Kennedy, Michael. The Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-19-311333-3.

- Kennedy, Michael. Mahler. New York: Schirmer Books, 1990. ISBN 0460125982

- Latham, Alison (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-866212-2.

- Maes, Francis. A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar, trans. by Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Morton, Brian, Shostakovich: His Life and Music (Life and Times) (London: Haus Publishers Ltd., 2007). ISBN 1-90-495050-7.

- Ottaway, Hugh, Vaughan Williams Symphonies (BBC Music Guides). Seattle; University of Washington Press, 1973. ISBN 0-295-95233-4.

- Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 20 vols. London: Macmillian, 1980. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Expanded Edition, 29 vols. London: Macmillian, 2001. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- Short, Michael, Notes for Hyperion CDA66660, Holst: Choral Fantasy; First Choral Symphony (London: Hyperion Records Limited, 1993).

- Simpson, Robert (ed.). The Symphony, 2 vols. New York: Drake Publishing, Inc., 1972.

- Volume 1: Haydn to Dvořák ISBN 0877492441

- Volume 2: Mahler to the Present Day ISBN 087749245X

- Solomon, Maynard. Late Beethoven—Music, Thought, Imagination. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2003. ISBN 0-520-23746-3.

- Steinberg, Michael. The Symphony. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-506177-2.

- Steinberg, Michael. The Choral Masterworks. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-195-12644-0.

- Volkov, Solomon. Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich, trans. by Antonina W. Bouis. New York: Harper & Row, 1979. ISBN 0-06-014476-9.

- Volkov, Solomon. St. Petersburg: A Cultural History, trans. by Antonina W. Bouis. New York: The Free Press, 1995. ISBN 0-02-874052-1.

- Volkov, Solomon. Shostakovich and Stalin: The Extraordinary Relationship Between the Great Composer and the Brutal Dictator, trans. by Antonina W. Bouis. New York: Knopf, 2004. ISBN 0-375-41082-1.

- White, Eric Walter. Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1966. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 66-27667. (Second edition, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979. ISBN 0520039831.)

- Wilson, Elizabeth, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, Second Edition (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994, 2006). ISBN 0-691-12886-3.

References

- Kennedy, Oxford, 144.

- ^ "Avant-Propos de l'auteur", Reiter-Biedermann's vocal score (Winterhur, 1858), p. 1.

- ^ Solomon, 217.

- ^ Solomon, 221 Cite error: The named reference "sol221" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Kennedy, Vaughan Williams, 444.

- ^ Kennedy, Mahler, 151.

- Cairns, The Symphony, 1:223.

- White, 321.

- Steinberg, 268-9.

- Walsh, New Grove (2001), 24:843.

- Kennedy, Mahler, 152.

- Franklin, New Grove (2001), 15:622.

- ^ Ottaway, New Grove, 19:572.

- ^ Cox, The Symphony, 2:115.

- Ottaway, Vaughan Williams Symphonies, 17.

- Kennedy, Vaughan Williams, 126.

- Kennedy, Vaughan Williams, 131.

- Short, 2.

- Steinberg, Choral Masterworks, 241-2.

- Norris, New Grove (2001), 20:715.

- Maes, 366-7.

- Morton, 106.

- Schwarz, New Grove, 17:270.

- Holiman, 262-263.

- As phrased in Walsh, New Grove (2001), 24:843.

- Walsh, New Grove (2001), 24:843.

- Brett, New Grove (2001) 4:374.

- Solomon, 218.

- ^ Solomon, 219.

- Prose jotting to Die Kunst und die Revolution, in Richard Wagner's Prose Works, tr. W. Ashton Hills, 8 vols. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1893), 8:362.

- Solonon, 219-220.

- Holoman, 261.

- Holoman, 260.

- BBC Philharmonic Orchestra homepage

- Holoman, 263.

- MacDonald, New Grove, 2:596.

- ^ Temperley, New Grove, 18:460.

- Searle, The Symphony, 1:269.

- Shulstad, 217.

- Shulstad, 219.

- Searle, "Liszt, Franz", New Grove, 11:45.

- Bonds, New Grove (2001), 24:838.

- Volkov, Testimony, 184; Arnshtam interview with Sofiya Khentova in Khentova, In Shostakovich's World (Moscow, 1996), 234, as quoted in Wilson, 171—172.

- ^ Volkov, Shostakovich and Stalin, 175.

- Volkov, St. Petersburg,427.

- Volkov, St. Petersburg, 427-428.

- Steinberg, The Symphony, 557.

- ^ Mitchell, New Grove, 11:515.

- Truscott, The Symphony, 2:34.

- Truscott, The Symphony, 2:39.

- Carr, 73.

- Carr, 74.

- Kennedy, Mahler, 77.

- Kennedy, Mahler, 149

- ^ New Grove, 18:524-525.

- Kennedy, Mahler, 150.

- Seckerson, Edward, Gramophone March 2005.

- Steinberg, The Symphony, 339.

- Steinberg, The Symphony, 335.

- Kennedy, Oxford, 48, 144.