This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 132.3.53.81 (talk) at 19:28, 25 April 2014 (→Limitations on CCW Permits). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:28, 25 April 2014 by 132.3.53.81 (talk) (→Limitations on CCW Permits)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Open carry in the United States

Concealed carry or carrying a concealed weapon (CCW), is the practice of carrying a weapon (such as a handgun) in public in a concealed manner, either on one's person or in close proximity. Not all weapons that fall under CCW controls are lethal. For example, in Florida, carrying pepper spray in more than a specified volume (2 oz.) of chemical requires a CCW permit, whereas anyone may legally carry a smaller, so-called, “self-defense chemical spray” device hidden on their person without a CCW permit.

While there is no federal law specifically addressing the issuance of concealed-carry permits, all 50 states have passed laws allowing citizens to carry certain concealed firearms in public, either without a permit or after obtaining a permit from local government and/or law enforcement. Illinois had been the last state without such a provision – but its long-standing ban on concealed weapons was overturned in a federal appeals court, on Constitutional grounds. Illinois was required by the court to draft a concealed carry law by July 9, 2013 (including a 30-day extension) at which time the Illinois legislature, over-riding the amendatory veto of the governor who had sought to impose many restrictions, approved concealed carry to begin January 2014, at the latest.

The states give different terms for licenses or permits to carry a concealed firearm, such as a Concealed Handgun License/Permit (CHL/CHP), Concealed Carry Weapons (CCW), Concealed (Defensive/Deadly) Weapon Permit/License (CDWL/CWP/CWL), Concealed Carry Permit/License (CCP/CCL), License To Carry (Firearms) (LTC/LTCF), Carry of Concealed Deadly Weapon license (CCDW), Concealed Pistol License (CPL), etc. Thirteen states use a single permit to regulate the practices of both concealed and open carry of a handgun.

Some states publish statistics indicating how many residents hold permits to carry concealed weapons, and their demographics. For example, Florida has issued 2,031,106 licenses since adopting its law in 1987, and had 843,463 licensed permit holders as of July 31, 2011. Reported permit holders are predominantly male. Some states have reported the number of permit holders increasing over time. "With hard numbers or estimates from all but three of the 49 states that have laws allowing for issuance of carry permits, the GAO reports that there were about 8 million active permits in the United States as of December 31, 2011. That's about a million more than previous estimates by scholars."

The number of permits revocations is typically small. The grounds for revocation in most states, other than expiration of a time-limited permit without renewal, is typically the commission of a gross misdemeanor or felony by the permit holder. While these crimes are often firearm-related (including unlawful carry), a 3-year study of Texas crime statistics immediately following passage of CHL legislation found that the most common crime committed by CHL holders that would be grounds for revocation was actually DUI, followed by unlawful carry and then aggravated assault. The same study concluded that Texas CHL holders were always less likely to commit any particular type of crime than the general population, and overall were 13 times less likely to commit any crime.

History

Laws banning the carrying of concealed weapons were passed in Kentucky and Louisiana in 1813, and other states soon followed: Indiana (1820), Tennessee and Virginia (1838), Alabama (1839), and Ohio (1859). Similar laws were passed in Texas, Florida, and Oklahoma. Until the early 2000s, many states in the South were either No-Issue or Restrictive May-Issue, which were a vestige of the Jim Crow era. In the past decade, these states have largely enacted Shall-Issue licensing laws, with Arizona and Arkansas (for certain situations) legalizing Unrestricted concealed carry.

State laws

Regulations differ widely by state, with most states currently maintaining a "Shall-Issue" policy. As recently as the mid-'90s most states were No-Issue or May-Issue, but over the past 30 years states have consistently migrated to less restrictive alternatives. For detailed information on individual states' permitting policies, see Gun laws in the United States by state.

Permitting policies

| Jurisdiction | Shall-issue | May-issue | Unrestricted | No-issue | Disputed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | |||||

| Alaska | |||||

| American Samoa | |||||

| Arizona | |||||

| Arkansas | On Journey | ||||

| California | Some counties in practice | ||||

| Colorado | |||||

| Connecticut | In practice | ||||

| Delaware | In practice | ||||

| District of Columbia | |||||

| Florida | |||||

| Georgia | |||||

| Guam | in practice | ||||

| Hawaii | In practice | ||||

| Idaho | Rural Areas | ||||

| Illinois | |||||

| Indiana | |||||

| Iowa | |||||

| Kansas | |||||

| Kentucky | |||||

| Louisiana | |||||

| Maine | |||||

| Maryland | In practice | ||||

| Massachusetts | |||||

| Michigan | |||||

| Minnesota | |||||

| Mississippi | |||||

| Missouri | |||||

| Montana | Outside of city limits | ||||

| Nebraska | |||||

| Nevada | |||||

| New Hampshire | |||||

| New Jersey | In practice | ||||

| New Mexico | In vehicle/Unloaded | ||||

| New York | |||||

| North Carolina | |||||

| North Dakota | |||||

| Northern Mariana Islands | |||||

| Ohio | |||||

| Oklahoma | |||||

| Oregon | |||||

| Pennsylvania | |||||

| Puerto Rico | In practice | ||||

| Rhode Island | Local permits | In practice | |||

| South Carolina | |||||

| South Dakota | |||||

| Tennessee | |||||

| Texas | |||||

| United States Virgin Islands | |||||

| Utah | |||||

| Vermont | |||||

| Virginia | |||||

| Washington | |||||

| West Virginia | |||||

| Wisconsin | |||||

| Wyoming | |||||

| US Military installations |

State regulations relating to the issuance of concealed carry permits generally fall into four categories described as Unrestricted, Shall Issue, May issue and No Issue.

Unrestricted

An Unrestricted jurisdiction is one in which a permit is not required to carry a concealed handgun. This is sometimes called Constitutional carry.

Among U.S. states, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Vermont and Wyoming allow residents to carry a concealed firearm without a permit. These states also allow the open carry of a handgun without a permit.

Vermont does not have any provision for issue of concealed-carry licenses, as none has ever been necessary. As such, Vermont residents wishing to carry handguns in other states must acquire a license from a state which is valid in their destination. A popular choice is Florida's concealed handgun permit, which is valid for nonresident holders in 28 other states. Alaska, Arizona, and Wyoming all previously had concealed-carry license requirements prior to adoption of unrestricted carry laws, and continue to issue licenses on a "shall-issue" basis for the purposes of inter-state reciprocity (allowing residents of the state to travel to other states with a concealed weapon, abiding by that state's law).

In Montana, Utah, South Carolina, and New Hampshire, bills are being discussed that would allow unrestricted carry. Montana and Idaho both currently allow concealed carry without a permit in places outside of any incorporated municipality. New Mexico and New Hampshire laws allow an individual to conceal carry an unloaded handgun without a permit. New Mexico further allows one to carry a loaded hangun either openly or concealed while traveling in a vehicle, including motorcycles, bicycles or while riding a horse.

The Federal Gun Free School Zones Act limits where an unlicensed person may carry; carry of a weapon, openly or concealed, within 1000 feet of a school zone is prohibited, with exceptions granted in the Federal law to holders of valid State-issued weapons permits (State laws may reassert the illegality of school zone carry by license holders), and under LEOSA to current and honorably retired law enforcement officers (regardless of permit, usually trumping State law).

Shall-Issue

A Shall-Issue jurisdiction is one that requires a license to carry a concealed handgun, but where the granting of such licenses is subject only to meeting determinate criteria laid out in the law; the granting authority has no discretion in the awarding of the licenses, and there is no requirement of the applicant to demonstrate "good cause". The laws in a Shall-Issue jurisdiction typically state that a granting authority shall issue a license if the criteria are met, as opposed to laws in which the authority may issue a license at their discretion.

Typical license requirements include residency, minimum age, submitting fingerprints, passing a computerized instant background check (or a more comprehensive manual background check), attending a certified handgun/firearm safety class, passing a practical qualification demonstrating handgun proficiency, and paying a required fee. These requirements vary widely by jurisdiction, with some having few or none of these and others having most or all.

The following are Shall-Issue states: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Certain states and jurisdictions, while "may-issue" by law, direct their issuing authorities to issue licenses to all or nearly all qualified applicants, and as such they are considered "shall-issue" in practice. Connecticut, and certain cities and counties in New York are examples.

Connecticut law specifies that CCW licenses be granted on a May-Issue basis, but the state's courts have established that issuing authorities must grant CCW licenses on a Shall-Issue basis for applicants who meet all statutory qualifications, as unlike other May-Issue states Connecticut law does not contain a requirement for the applicant to show "necessary and proper reason" for obtaining a license. Connecticut has a two-tiered system of Temporary (60-day) and Regular (5-year) licenses, the permanent licensing process considered to be shall-issue in practice. In Connecticut, issuance of the temporary license from local authorities is not a prerequisite to obtain the regular license; however one must apply for the temporary license and wait for a decision from local authorities before applying for the regular license. Normally, the regular license is generally granted for applicants that meet statutory criteria regardless of whether the temporary license is issued or denied.

May-Issue

A May-Issue jurisdiction is one that requires a permit to carry a concealed handgun, and where the granting of such permits is partially at the discretion of local authorities (frequently the sheriff's department or police), with a few states consolidating this discretionary power under state-level law enforcement. The law typically states that a granting authority "may issue" a permit if various criteria are met, or that the permit applicant must have "good cause" (or similar) to carry a concealed weapon. In most such situations, self-defense in and of itself often does not satisfy the "good cause" requirement, and issuing authorities in some May-Issue jurisdictions have been known to arbitrarily deny applications for CCW permits without providing the applicant with any substantive reason for the denial.

May-Issue can be compared to Shall-Issue where in a May-Issue jurisdiction, the burden of proof for justifying the need for a permit rests with the applicant, whereas in a Shall-Issue jurisdiction the burden of proof to justify denying a permit rests with the issuing authority.

The following are "may-issue" states: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island.

A state that is de jure a May-Issue jurisdiction may range anywhere from Shall-Issue to No-Issue in practice, i.e., Permissive May-Issue to Restrictive May-Issue, based on each licensing authority's willingness to issue permits to applicants:

- Connecticut and Delaware are regarded as Permissive May-Issue states, where either governmental policy or court precedence direct issuing authorities to approve applications that meet all non-discretionary criteria.

- Hawaii, Maryland, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and Rhode Island (for statewide CCW permits) are considered Restrictive May-Issue states, where issuing authorities are directed to deny most or all applications, either based on hard-to-meet "good cause" requirements or agency policies specifically prohibiting issue. Additionally, Rhode Island (for state permits), Maryland and New Jersey require the applicant provide substantive evidence of a clear and immediate threat on their lives that exists outside of their home at the time the permit application is filed. Rhode Island further requires applicants for the statewide permit to submit to a mental health records check at the applicant's expense.

- California, Massachusetts, and New York vary within state; Inland California, rural portions of Massachusetts, and Upstate New York are Permissive, while the New York City, Long Island, Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco metropolitan areas are Restrictive. California's "May Issue" status has been thrown into question with the 9th District Court's ruling in Peruta v County of San Diego, where the state's mostly restrictive concealed carry requirements & qualifications were deemed unconstitutional.

- Rhode Island state law is two-tier; local authorities are directed by state law and court precedent (Archer v McGarry) to practice shall-issue permitting policy, but the Attorney General's office has discretionary authority over state-issued permits (required for open carry in general and for concealed carry outside the resident's home jurisdiction), and some local jurisdictions, at the recommendation of the AG, still refer all applicants to the AG's office and the "may-issue" state-level system in violation of Archer.

In some May-Issue jurisdictions, permits are only issued to individuals with celebrity status, have political connections, or have a high degree of wealth. In some such cases, issuing authorities charge arbitrarily-defined fees that go well beyond the basic processing fee for a CCW permit, thereby making the CCW permit unaffordable to most applicants.

May-issue permitting policies are currently under legal challenge in California, Hawaii, Maryland, New Jersey and New York; most thus far have survived challenge though the "May Issue" status for California and Hawaii have recently been thrown into question by the ruling of the 9th District Federal Appeals court in Peruta v County of San Diego. In recent cases challenging restrictive discretionary issue laws, federal district and appeals courts have generally applied intermediate scrutiny to these and other Second Amendment related cases, where the courts recognize that restrictive concealed carry laws "infringe on an individual's right to keep and bear arms," but also recognizes that such infringement is permitted to further "an important government interest in public safety." In Maryland, Woollard v. Sheridan, the United States District Court for the District of Maryland decided in favor of a Maryland resident who was denied a permit renewal due to lack of "good cause" in accordance with Maryland law. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed, holding the "good cause" requirement met the standard of intermediate scrutiny applicable to restrictions on the right to carry arms outside the home, and reinstated the "good cause" requirement on March 21, 2013. The plaintiffs in the case filed a petition for certiorari in the United States Supreme Court; the court denied certiorari without comment on October 15. New York's similar "good cause" requirement was also under challenge in Kachalsky v. Cacase. However, certiorari before SCOTUS was denied on April 15, 2013. Additionally, the case Peruta v. County of San Diego that is being heard by the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals is challenging discretionary issue laws in California. Drake v. Filko, involving several plaintiffs (including one kidnap victim) denied permits under New Jersey's permitting system; the suit challenged New Jersey's "justifiable need" requirement for obtaining a carry permit. The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit affirmed the lower court's judgment holding the requirement constitutional, holding (much like the 4th Circuit in Woollard and the 2nd Circuit in Kachalsky) that the New Jersey statute survived intermediate scrutiny. The common theme from Courts of Appeals rulings upholding May-Issue laws is that state or local policies in limiting who is granted permits to carry firearms in public "furthers an important government interest in public safety." The courts have opined that these laws survive intermediate scrutiny on that basis.

While members of the Armed Services receive extensive small arms training, United States Military installations have some of the most restrictive rules for the possession, transport, and carrying of personally-owned firearms in the country. Overall authority for carrying a personally-owned firearm on a military installation rests with the installation commander, although the authority to permit individuals to carry firearms on an installation is usually delegated to the Provost Marshal. Military installations do not recognize state-issued concealed carry permits, and state firearms laws generally do not apply to military bases, regardless of the state in which the installation is located. Federal law (18 USC, Section 930) generally forbids the possession, transport, and carrying of firearms on military installations without approval from the installation commander. While federal law gives installation commanders wide discretion in establishing firearms policies for their respective installations, local discretion is often constrained by policies and directives from the headquarters of each military branch and major commands. Installation policies can vary from No-Issue for most bases to Shall-Issue in rare circumstances. Installations that do allow the carrying of firearms typically restrict carrying to designated areas and for specific purposes (i.e., hunting or officially-sanctioned shooting competitions in approved locations on the installation). Installation commanders may require the applicant complete extensive firearms safety training, undergo a mental health evaluation, and obtain a letter of recommendation from his or her unit commander (or employer) before such authorization is granted. Personnel that reside on a military installation are typically required to store their personally-owned firearms in the installation armory, although the installation commander or provost marshal may permit a servicemember to store his or her personal firearms in their on-base dwelling if he or she has a gun safe or similarly-designed cabinet where the firearms can be secured. Prior to 2011, military commanders could impose firearms restrictions to servicemenbers residing off-base, such as mandatory registration of firearms with the base Provost Marshal, restricting or banning the carrying of firearms by servicemembers either on or off the installation regardless of whether the member had a state permit to carry, and requiring servicemembers to have a gun safe or similar container to secure firearms when not in use. A provision was included in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2011 that limited commanders' authority to impose restrictions on the possession and use of personally-owned firearms by servicemembers who reside off-base.

No-Issue

A No-Issue jurisdiction is one that – with very limited exceptions – does not allow any private citizen to carry a concealed handgun in public. The term refers to the fact that no concealed carry permits will be issued (or recognized). Since July 2013, with the legalization of concealed carry in Illinois, there are no patently no-issue states.

The District of Columbia is a No-Issue jurisdiction by law, and forbids both open and concealed carry except under a very limited set of circumstances. The District of Columbia recently lost a Supreme Court case relating to restrictions on ownership and possession of firearms (District of Columbia v Heller), however, the case did not specifically address the question of public carry, either open or concealed. While technically May-Issue under state law, Hawaii, Maryland, New Jersey, Rhode Island (for statewide permits issued by the Attorney General's Office) and certain cities and counties within California and New York are No-Issue jurisdictions in practice, with governmental policy directing officials with discretionary power to rarely or never issue licenses. Additionally, all of the United States' insular territories (Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, etc.) are No-Issue jurisdictions either by law or in practice. Most No-Issue jurisdictions have exceptions to their laws that permit open or concealed carry by active and retired law enforcement officials, armed security personnel while on duty and in uniform, and for members of the Armed Forces.

Limitations on CCW Permits

Most May-Issue jurisdictions, and some Shall-Issue jurisdictions allow issuing authorities to impose limitations on CCW permits, such as the type and caliber of handguns that may be carried (Massachusetts, New Mexico, Texas), restrictions on places where the permit is valid (New York, Rhode Island), restricting concealed carry to purposes or activities specified on the approved permit application (New York, California), limitations on magazine size (Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York), or limitations on the number of firearms that may be carried concealed by a permit-holder at any given time.

Training requirements

Some states require concealed carry applicants to certify their proficiency with a firearm through some type of training or instruction. Certain training courses developed by the National Rifle Association that combine classroom and live-fire instruction typically meet most state training requirements. Some states recognize prior military or police service as meeting training requirements.

Classroom instruction would typically include firearm mechanics and terminology, cleaning and maintenance of a firearm, concealed carry legislation and limitations, liability issues, carry methods and safety, home defense, methods for managing and defusing confrontational situations, and practice of gun handling techniques without firing the weapon. Most required CCW training courses devote a considerable amount of time to liability issues.

Depending on the state, a practical component during which the attendee shoots the weapon for the purpose of demonstrating safety and proficiency, may be required. During range instruction, applicants would typically learn and demonstrate safe handling and operation of a firearm and accurate shooting from common self-defense distances. Some states require a certain proficiency to receive a passing grade, whereas other states (e.g., Florida) technically require only a single-shot be fired to demonstrate handgun handling proficiency.

CCW training courses are typically completed in a single day and are good for a set period, the exact duration varying by state. Some states require re-training, sometimes in a shorter, simpler format, for each renewal. An example of a training organization is the Midwest Carry Academy which specializes in practical shooting and defensive training.

A few states, e.g., South Carolina, recognize the safety and use-of-force training given to military personnel as acceptable in lieu of formal civilian training certification. Such states will ask for a military ID (South Carolina) for active persons or DD214 for honorably discharged persons. These few states will commonly request a copy of the applicant's BTR (Basic Training Record) proving an up-to-date pistol qualification. Active and retired law enforcement officers are generally exempt from qualification requirements, due to a federal statute permitting retired law enforcement officers to carry concealed weapons in the United States.

Virginia recognizes eight specific training options to prove competency in handgun handling, ranging from DD214 for honorably discharged military veterans, to certification from law enforcement training, to firearms training conducted by a state or NRA certified firearms instructor including electronic, video, or on-line courses. While any one of the eight listed options will be considered adequate proof, individual circuit courts may recognize other training options.

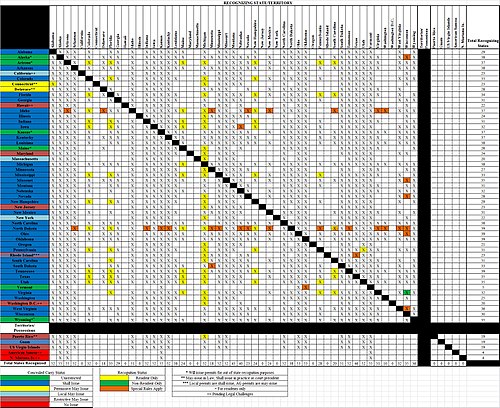

Reciprocity

Many jurisdictions have established arrangements where they recognize or honor permits or licenses issued by other jurisdictions with comparable standards, for instance in regard to marriage or driver's licenses. This is known as Reciprocity and is based on U.S. Constitution "full faith and credit" provision. Due to the nature of gun politics, reciprocity in regard to weapons carry permits or licenses has been controversial.

Reciprocal recognition of concealed carry privileges and rights vary state-to-state, are negotiated between individual states, and sometimes additionally depend on the residency status of the license holder. While 37 states have reciprocity agreements with at least one other state and several states honor all out-of-state concealed carry permits, some states have special requirements like training courses or safety exams, and therefore do not honor permits from states that do not have such requirements for issue. Some states make exceptions for persons under the minimum age (usually 21) if they are active or honorably-discharged members of the military or a police force (the second of these two is allowed under Federal law). States that do not have this exemption generally do not recognize any license from states that do. An example of this is the State of Washington's refusal to honor any Texas CHL as Texas has the military exception to age.

Florida (Resident), Michigan and Missouri hold the widest reciprocity of all the states in the U.S. with the number of other states honoring their permits at 37, followed by Oklahoma at 36, Alaska at 35 then Florida (Non-Resident) and Utah at 33; Both Michigan and Missouri, however, do not issue permits to non-residents, and some states that honor Utah permits do not extend that to include Utah's non-resident permits. Also, effective May 10, 2011, Utah requires that non-resident applicants, who reside in states that have reciprocity with Utah, must first obtain the CCW permit from their state of residence before applying for the Utah permit.

Although carry may be legal under State law in accordance with reciprocity agreements, the Federal Gun Free School Zones Act subjects an out-of-state permit holder to federal felony prosecution if they carry a firearm within 1000 feet of any K-12 school's property line.

Restricted Premises

While generally a concealed carry permit allows the permit holder to carry a concealed weapon in public, a state may restrict carry of a firearm including a permitted concealed weapon while in or on certain properties, facilities or types of businesses that are otherwise open to the public. These areas vary by state (except for the first item below; Federal offices are subject to superseding Federal law) and can include:

- Federal government facilities, including post offices, IRS offices, federal court buildings, military/VA facilities and/or correctional facilities, Amtrak trains and facilities, and Corps of Engineers-controlled property (carry in these places is prohibited by Federal law and preempts any existing State law). Carry on land controlled by the Bureau of Land Management (federal parks and wildlife preserves) is allowed by Federal law as of the 2009 CARD Act, but is still subject to State law. However, carry into restrooms or any other buildings or structures located within federal parks is illegal in the United States, despite concealed carry being otherwise legal in federal parks with a permit recognized by the state in which the federal park is located. Similarly, concealed carry into caves located within federal parks is illegal.

- State government facilities, including courthouses, DMV/DoT offices, police stations, correctional facilities, and/or meeting places of government entities (exceptions may be made for certain persons working in these facilities such as judges, lawyers, and certain government officials both elected and appointed)

- Venues for political events, including rallies, parades, debates, and/or polling places

- Educational institutions including elementary/secondary schools and colleges. Some states have "drop-off exceptions" which only prohibit carry inside school buildings, or permit carry while inside a personal vehicle on school property. Utah & Colorado currently do not restrict concealed weapons (in hands of permit holders) on State Universities and College Campuses. Utah also allows permit holders to carry handguns in elementary/secondary schools.

- Public interscholastic and/or professional sporting events and/or venues (sometimes only during a time window surrounding such an event)

- Amusement parks, fairs, parades and/or carnivals

- Businesses that sell alcohol (sometimes only "by-the-drink" sellers like restaurants, sometimes only establishments defined as a "bar" or "nightclub", or establishments where the percentage of total sales from alcoholic beverages exceeds a specified threshold)

- Hospitals (even if hospitals themselves are not restricted, "teaching hospitals" partnered with a medical school are sometimes considered "educational institutions"; exceptions are sometimes made for medical professionals working in these facilities)

- Churches, mosques and other "Houses of worship," usually at the discretion of the church clergy (Ohio allows with specific permission of house of worship)

- Municipal mass transit vehicles or facilities

- Sterile areas of airports (sections of the airport located beyond security screening checkpoints)

"Opt-out" statutes ("gun-free zones")

Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin all allow private businesses to post a specific sign (language and format vary by state) prohibiting concealed carry, violation of which, in some of these states, is grounds for revocation of the offender's concealed carry permit and criminal prosecution. Other states, such as Virginia, enforce only trespassing laws when a person violates a "Gun Free Zone" sign. By posting the signs, businesses create areas where it is illegal to carry a concealed handgun similar to regulations concerning schools, hospitals, and public gatherings. In addition to signage, virtually all jurisdictions allow some form of oral communication by the lawful owner or controller of the property that a person is not welcome and should leave. This notice can be given to anyone for any reason (except for statuses that are protected by the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other CRAs, such as race), including due to the carrying of firearms by that person, and refusal to heed such a request to leave may constitute trespassing. In some jurisdictions trespass by a person carrying a firearm may have more severe penalties than "simple" trespass, while in other jurisdictions, penalties are lower than for trespass.

There is considerable dispute over the effectiveness of such "gun-free zones". Opponents of such measures, such as OpenCarry.org, state that, much like other malum prohibitum laws banning gun-related practices, only law-abiding individuals will heed the signage and disarm. Individuals or groups intent on committing far more serious crimes, such as armed robbery or murder, will not be deterred by signage prohibiting weapons. Further, the reasoning follows that those wishing to commit mass murder might intentionally choose gun-free venues like shopping malls, schools and churches (where weapons carry is generally prohibited by statute or signage) because the population inside is disarmed and thus less able to stop them.

In some states, business owners have been documented posting signs that appear to prohibit guns, but legally do not because the signs do not meet local or state laws defining required appearance, placement, or wording of signage. Such signage can be posted out of ignorance to the law, or intent to pacify gun control advocates while not actually prohibiting the practice. The force of law behind a non-compliant sign varies based on state statutes and case law. Some states interpret their statutes' high level of specification of signage as evidence that the signage must meet the specification exactly, and any quantifiable deviation from the statute makes the sign non-binding. Other states have decided in case law that if efforts were made in good faith to conform to the statutes, the sign carries the force of law even if it fails to meet current specification. Still others have such lax descriptions of what is a valid sign that virtually any sign that can be interpreted as "no guns allowed" is binding on the license holder.

Brandishing and printing

Printing refers to a circumstance where the shape or outline of a firearm is visible through a garment while the gun is still fully covered, and is generally not desired when carrying a concealed weapon. Brandishing can refer to different actions depending on jurisdiction. These actions can include printing through a garment, pulling back clothing to expose a gun, or unholstering a gun and exhibiting it in the hand. The intent to intimidate or threaten someone may or may not be required legally for it to be considered brandishing.

In some jurisdictions, especially where open carry is not legal, printing is also a crime. Brandishing is a crime in most jurisdictions, but the definition of brandishing varies widely.

Under California law, the following conditions have to be present to prove brandishing:

- " A person, in the presence of another person, drew or exhibited a ; That person did so in a rude, angry, or threatening manner] That person, in any manner, unlawfully used the in a fight or quarrel] The person was not acting in lawful self-defense.]"

In Virginia law:

- "It shall be unlawful for any person to point, hold or brandish any firearm or any air or gas operated weapon or any object similar in appearance, whether capable of being fired or not, in such manner as to reasonably induce fear in the mind of another or hold a firearm or any air or gas operated weapon in a public place in such a manner as to reasonably induce fear in the mind of another of being shot or injured. However, this section shall not apply to any person engaged in excusable or justifiable self-defense."

Federal law

Gun Control Act of 1968

The Gun Control Act passed by Congress in 1968 lists felons, illegal aliens, and other codified persons as prohibited from purchasing or possessing firearms. During the application process for concealed carry states carry out thorough background checks to prevent these individuals from obtaining permits. Additionally the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act created an FBI maintained system in 1994 for instantly checking the backgrounds of potential firearms buyers in an effort to prevent these individuals from obtaining weapons.

Firearm Owners Protection Act

Main article: Firearm Owners Protection ActThe Firearm Owners Protection Act (FOPA) of 1986 allows a gun owner to travel through states in which their firearm possession is illegal as long as it is legal in the states of origination and destination, the owner is in transit and does not remain in the state in which firearm possession is illegal, and the firearm is transported unloaded and in a locked container. The FOPA addresses the issue of transport of private firearms from origin to destination for purposes lawful in state of origin and destination; FOPA does not authorize concealed carry as a weapon of defense during transit. New York State Police do not recognize this law. If caught you will be arrested and then required to use FOPA as an affirmative defense to the charges of illegal possession.

Law Enforcement Officer's Safety Act

In 2004, the United States Congress enacted the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act, 18 U.S. Code 926B and 926C. This federal law allows two classes of persons – the "qualified law enforcement officer" and the "qualified retired law enforcement officer" – to carry a concealed firearm in any jurisdiction in the United States, regardless of any state or local law to the contrary, with certain exceptions.

Federal Gun Free School Zones Act

The Federal Gun Free School Zone Act limits where a person may legally carry a firearm. It does this by making it generally unlawful for an armed citizen to be within 1000 feet (extending out from the property lines) of a place that the individual knows, or has reasonable cause to believe, is a K–12 school. Although a State-issued carry permit may exempt a person from this restriction in the State that physically issued their permit, it does not exempt them in other States which recognize their permit under reciprocity agreements made with the issuing State. The law's failure to provide adequate protection to LEOSA qualified officers, licensed concealed carry permit holders, and other armed citizens, is an issue that the United States Congress so far has not addressed.

Federal property

Some federal statutes restrict the carrying of firearms on the premises of certain Federal properties such as military installations or land controlled by the USACE.

National park carry

On May 22, 2009, President Barack Obama signed H.R. 627, the "Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009," into law. The bill contained an amendment introduced by Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK) that prohibits the Secretary of the Interior from enacting or enforcing any regulations that restrict possession of firearms in National Parks or Wildlife Refuges, as long as the person complies with laws of the state in which the unit is found. This provision was supported by the National Rifle Association and opposed by the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, the National Parks Conservation Association, and the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees, among other organizations. As of February 2010 concealed handguns are for the first time legal in all but 3 of the nation's 391 national parks and wildlife refuges so long as all applicable federal, state, and local regulations are adhered to. Hawaii is a notable exception. Concealed and open carry are both illegal in Hawaii for all except retired military or law enforcement personnel. Previously firearms were allowed into parks non-concealed and unloaded.

Full faith and credit (CCW permits)

Attempts were made in the 110th Congress, United States House of Representatives (H.R. 226) and the United States Senate (S. 388), to enact legislation to compel complete reciprocity for concealed carry licenses. Opponents of national reciprocity have pointed out that this legislation would effectively require states with more restrictive standards of permit issuance (e.g., training courses, safety exams, "good cause" requirements, et al.) to honor permits from states with more liberal issuance policies. Supporters have pointed out that the same situation already occurs with marriage licenses, adoption decrees and other state documents under the "full faith and credit" clause of the Constitution. Some states have already adopted a "full faith and credit" policy treating out-of-state carry permits the same as driver's license or marriage license without federal legislation mandating such a policy.

Legal issues

Court rulings

Prior to the 1897 supreme court case Robertson v. Baldwin, the federal courts had been silent on the issue of concealed carry. In the dicta from a maritime law case the Supreme Court commented that state laws restricting concealed weapons do not infringe upon the right to bear arms protected by the Federal Second Amendment.

In the majority decision in the 2008 Supreme Court case of District of Columbia v. Heller, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote;

- "Like most rights, the Second Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose: For example, concealed weapons prohibitions have been upheld under the Amendment or state analogues ... The majority of the 19th-century courts to consider the question held that prohibitions on carrying concealed weapons were lawful under the Second Amendment or state analogues."

Heller was a landmark case because for the first time in United States history a Supreme Court decision defined the right to bear arms as constitutionally guaranteed to private citizens rather than a right restricted to "well regulated militia". The Justices asserted that sensible restrictions on the right to bear arms are constitutional, however, an outright ban on a specific type of firearm, in this case handguns, was in fact unconstitutional. The decision is limited because it only applies to federal enclaves such as the District of Columbia.

On June 28, 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the handgun ban enacted by the city of Chicago, Illinois, in McDonald v. Chicago, effectively extending the Heller decision to states and local governments nationwide. Banning handguns in any jurisdiction has the effect of rendering invalid any licensed individual's right to carry concealed in that area except for federally exempted retired and current law enforcement officers and other government employees acting in the discharge of their official duties.

Legal liability

Even when self-defense is justified, there can be serious civil or criminal liabilities related to self-defense when a concealed carry permit holder brandishes or fires his/her weapon. For example, if innocent bystanders are hurt or killed, there could be both civil and criminal liabilities even if the use of deadly force was completely justified. Some states technically allow an assailant who is shot by a gun owner to bring civil action. In some states, liability is present when a resident brandishes the weapon, threatens use, or exacerbates a volatile situation, or when the resident is carrying while intoxicated. It is important to note that simply pointing a firearm at any person constitutes felony assault with a deadly weapon unless circumstances validate a demonstration of force. A majority of states who allow concealed carry, however, forbid suits being brought in such cases, either by barring lawsuits for damages resulting from a criminal act on the part of the plaintiff, or by granting the gun owner immunity from such a civil suit if it is found that he or she was justified in shooting.

Simultaneously, increased passage of "Castle Doctrine" laws allow persons who own firearms and/or carry them concealed to use them without first attempting to retreat. The "Castle Doctrine" typically applies to situations within the confines of one's own home. Nevertheless many states have adopted escalation of force laws along with provisions for concealed carry. These include the necessity to first verbally warn a trespasser or lay hands on a trespasser before a shooting is justified (unless the trespasser is armed or assumed to be so). This escalation of force does not apply if the shooter reasonably believes a violent felony has been or is about to be committed on the property by the trespasser. Additionally some states have a duty to retreat provision which requires a permit holder, especially in public places, to vacate him or herself from a potentially dangerous situation before resorting to deadly force. The duty to retreat does not restrictively apply in a person's home or business though escalation of force may be required. In 1895 the Supreme Court ruled in Beard v. U.S. that if an individual does not provoke an assault and is residing in a place they have a right to be then they may use considerable force against someone they reasonably believe may do them serious harm without being charged with murder or manslaughter should that person be killed. Further, in Texas and California homicide is justifiable solely in defense of property. In other states, lethal force is only authorized when serious harm is presumed to be imminent.

Even given these relaxed restrictions on use of force, using a handgun must still be a last resort in some jurisdictions; meaning the user must reasonably believe that nothing short of deadly force will protect the life or property at stake in a situation. Additionally, civil liabilities for errors that cause harm to others still exist, although civil immunity is provided in the Castle Doctrine laws of some states (e.g., Texas).

Penalties for carrying illegally

Main article: Weapon possession (crime)Based on state law, the penalty for illegally carrying a firearm varies widely throughout the United States, ranging from a simple infraction punishable by a fine, to a felony conviction and mandatory incarceration, depending on the state. Similarly, actual enforcement of laws restricting or prohibiting open or concealed carry also varies greatly between localities. Authorities in jurisdictions that favor strong gun control policies will typically prosecute people for the mere fact they were carrying a firearm in an unlawful manner, regardless of actual intent. In jurisdictions that favor individual gun rights, authorities will typically not prosecute someone for illegally carrying a firearm, unless the individual clearly demonstrates some form of malicious intent. Typical policies that are used to determine who can legally carry concealed weapons are a prohibition of concealed carry, discretionary licensing, non-discretionary licensing, minimum age requirements (e.g., 18 or 21 years), successful completion of an instructor-led course, and marksmanship/handling qualification on a firing range. Less common is unregulated, legal concealed carry such as in Vermont, Alaska, Arizona, Wyoming, and unincorporated rural areas of Montana.

In the United States no convicted felon may purchase, transfer, or otherwise be in the possession of any firearm. Illegally concealing a handgun is a felony in many states therefore conviction of such a crime would automatically result in the forfeiture of a citizen's gun rights for life nationwide. Additional state penalties for unlawful carry of a concealed firearm can be severe with punishments including expensive fines, extended jail time, loss of voting rights, and even passport cancellation. A federal penalty of ten years in prison has been enacted for those found to be in possession of either firearms or ammunition while subject to a protection or restraining order. Such an order is grounds for the revocation of any concealed carry permit and the outright denial of any person's new application while the order is active. Weapon possession, in the context of concealed weapons, is a crime of that circumstance in which a person who is not legally authorized to carry a concealed weapon is found in possession of such a weapon. In the United States this can be interpreted as the possession of a firearm by a person legally disqualified from doing so under the Gun Control Act. These prohibited individuals include those who have been dishonorably discharged from the military, those who have been convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence, unlawful immigrant aliens, and individuals who have renounced their United States citizenship. None of these individuals are eligible for concealed weapons permits and may be punished not only for unlawful concealed carry of a handgun but for unlawful possession of a firearm. Depending on state law, it can apply to concealed carry of otherwise illegal knives such as stilettos, dirks or switchblades.

Citizens holding concealed carry permits may be prosecuted for failing to adhere to state and federal rules and regulations concerning the lawful exercise of carrying a concealed weapon. Some states do not allow the carrying of more than one concealed firearm by permit holders. Concealing two handguns, for example, might constitute a violation of law resulting in permit revocation or criminal charges. Carrying a handgun in the glove box of a vehicle, though commonly regarded as safe and legal, is considered illegal concealment in some states and could be punishable as a felony offense among non-permit holders. When arrested for any firearms offense the weapon(s) in question will be confiscated and could be destroyed upon conviction. While legally carrying concealed outside of one's particular state of residence, such as in a state which grants reciprocity to the bearer's permit, he or she must comply with all regulations in the state in which they are currently carrying even if those rules and regulations differ from those of the individual's permit issuing state. Some states require that a person carrying a concealed weapon immediately declare this fact to any law enforcement officer they may encounter in the line of their official duties. This provision most commonly applies to traffic stops and police questioning but is required upon approach of an officer by the person who is carrying concealed. Failure to comply with this provision is an arrestable misdemeanor and additionally may require the mandatory revocation of the licensee's permit. However simply passing an officer on the street, even at close distance, does not generally require the declaration of a concealed weapon. Carry of a concealed weapon by a licensed individual where prohibited is generally referred to as illegal weapon possession. In some states, no person may be in the public possession of a firearm while under the intoxicating effects of narcotics (whether prescribed or otherwise) or alcohol (usually defined as .01% BAC but up to .05% BAC in some areas).

Even in localities where concealed carrying is permitted, there may be legal restrictions on where a person may carry a concealed weapon unless state law overrides a business posting that no firearms are allowed.

The city of Chicago, Illinois as well as the District of Columbia had previously banned handguns completely within their respective jurisdictions. However, two recent Supreme Court cases have effectively deemed those statutes to be illegal (see above).

Lastly, some states regulate which firearms may be concealed by a particular permit holder. Texas, for example, differentiates between semi-automatic and non-semi-automatic firearms, and an "NSA"-class permit holder cannot carry an autoloading handgun (restricting them largely to revolvers). Texans who qualify with a revolver are only allowed to carry a revolver; if they qualify with a semi-automatic, they can carry either a semi-automatic or a revolver. Other restrictions seen in certain states include restricting the user to a gun no more powerful than they used when qualifying, or to one or more specific guns specified by the permit holder when applying. New York prohibits certain specific makes and models of pistols (mostly Saturday Night Specials) and will not issue a permit for those specific weapons. Other states ban the carrying of handguns with large-capacity magazines. In most states, though, a CCW permit holder is limited only by what they can conceal while wearing particular clothing.

Research on the efficacy of concealed carry

Main article: Defensive gun useAccording to attorney Frank Espohl, between 1987, when Florida adopted a concealed carry law, and 1993, its homicide rate dropped from 11.4 to 8.7 persons per 100,000. However, in 2003, economists and law professors Ian Ayres and John Donohue wrote that shall-issue laws do not reduce crime.

Economist John Lott studied FBI crime statistics from 1977 to 1993. In his 1998 book, More Guns, Less Crime, Lott said that the passage of concealed carry laws resulted in a murder rate decrease of 8.5%, rape rate decrease of 5%, and aggravated assault reduction of 7%. He said that his analysis of crime report data showed a statistically significant effect of concealed carry laws on crime.

In their 2003 article, Ayres and Donohue said that Lott's conclusions were the result of a limited data set and that re-running his tests with more complete data, subjected to less-constrained specifications and tweaked in plausible ways, yielded none of Lott's results. In 2010, Lott updated his findings with new data. According to the FBI, during the first year of the Obama administration the national murder rate declined by 7.4% along with other categories of crime which fell by significant percentages. During that same time national gun sales increased dramatically. According to Lott, 450,000 more people bought guns in November 2008 than in November 2007, representing a 40% increase in sales, a trend that continued throughout 2009. The drop in the murder rate was the biggest one-year drop since 1999, another year when gun sales soared in the wake of increased calls for gun control as a result of the Columbine shooting.

In a Chronicle of Higher Education interview, Ayres and Donohue said, "There are many factors that people might weigh in deciding whether to pass these laws or not, but this idea that there is a statistical basis for thinking that these laws will reduce crime simply is not true." When asked about Lott's response to their work, Donohue said: "There's really nothing they can say. It's sort of like we caught them failing to carry the 1." He later went on to acknowledge that, "Mr. Lott's research has convinced his peers of at least one point: No scholars now claim that legalizing concealed weapons causes a major increase in crime."

A committee of the National Research Council (NRC), the working arm of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), wrote that it found "no credible evidence" either supporting or disproving Lott's thesis. However, economist and committee member James Q. Wilson wrote a dissent in which he said that "some of results survive virtually every reanalysis done by the committee." On the Ayres and Donohue hybrid model showing more guns-more crime, the NAS panel stated: "The committee takes no position on whether the hybrid model provides a correct description of crime levels or the effects of right-to-carry laws." In an article for American Law and Economics Association (ALER), Donohue said the NRC results published from the hybrid model "could not be replicated on its data set." Lott replicated the NRC's results using its copy of the Ayres and Donohue model and data set, pointing out that the model used for the ALER article was different and introduced a truncation bias.

A 2008 article by Carlisle E. Moody and Thomas B. Marvell uses a more extensive data set and projects effects of the Ayres and Donohue hybrid model beyond a five-year span. Though their data set renders an apparent reduction in the cost of crime, Ayres and Donohue point out that the cost of crime increased in 23 of the 24 jurisdictions under scrutiny. Florida was the only jurisdiction showing positive effects from shall-issue laws. Ayres and Donohue question the special case of Florida as well.

Using publicly available media reports, the Violence Policy Center (VPC) said that from May 2007 through the end of 2009, concealed carry permit holders in the U.S. killed at least 117 individuals, including nine law enforcement officers (excluding cases where individuals were acquitted, but including pending cases). There were about 25,000 murders by firearm during that period. Furthermore, a large number of the victims were killed in extended suicides, most of which took place in the home of the shooter, where arms can be possessed without special permits. VPC also includes in its numbers several homicides using only long guns and several instances of accidental discharge.

According to FBI Uniform Crime Reports (UCR), in 2011 there were 12,664 murders and 653 justifiable homicides (of which 393 were performed by law enforcement) in the United States. Over previous years this reflects a decline in criminal homicide and an increase in homicides reported as justifiable (for 2008 UCR listed 14,180 murders, 616 justifiable homicides (of which 371 were by law enforcement). The UCR states that the justifiable homicide statistic does not represent eventual adjudication by medical examiner, coroner, district attorney, grand jury, trial jury or appellate court. Few U.S. jurisdictions allow a police crime report to adjudicate a homicide as justifiable and in any given year fifteen to twenty states do not report such statistics to FBI UCR, resulting in an undercount in the UCR table. The majority of defensive gun uses (DGUs) do not involve killing or wounding an attacker. Government surveys indicate 108,000 to 23 million DGUs per year, while private surveys indicate 764,000 to 3.6 million DGUs per year.

See also

- Concealed carry

- Gun laws in the United States (by state)

- Gun politics

- Gun control

- Gun politics in the US

- Open carry

- Self-defense

- Transport assumption

References

- "2012 Florida Statutes, TITLE XLVI CRIMES, Chapter 790 WEAPONS AND FIREARMS, 790.01 Carrying concealed weapons". 2012.

790.01 Carrying concealed weapons.— (1) Except as provided in subsection (4), a person who carries a concealed weapon or electric weapon or device on or about his or her person commits a misdemeanor of the first degree, punishable as provided in s. 775.082 or s. 775.083. (2) A person who carries a concealed firearm on or about his or her person commits a felony of the third degree, punishable as provided in s. 775.082, s. 775.083, or s. 775.084. (3) This section does not apply to a person licensed to carry a concealed weapon or a concealed firearm pursuant to the provisions of s. 790.06. (4) It is not a violation of this section for a person to carry for purposes of lawful self-defense, in a concealed manner: (a) A self-defense chemical spray. (b) A nonlethal stun gun or dart-firing stun gun or other nonlethal electric weapon or device that is designed solely for defensive purposes. (5) This section does not preclude any prosecution for the use of an electric weapon or device, a dart-firing stun gun, or a self-defense chemical spray during the commission of any criminal offense under s. 790.07, s. 790.10, s. 790.23, or s. 790.235, or for any other criminal offense.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 36 (help) - "2012 Florida Statutes, TITLE XLVI CRIMES, Chapter 790 WEAPONS AND FIREARMS, 790.001 Definitions". 2012.

(3)(a) "Concealed weapon" means any dirk, metallic knuckles, slungshot, billie, tear gas gun, chemical weapon or device, or other deadly weapon carried on or about a person in such a manner as to conceal the weapon from the ordinary sight of another person. (b) "Tear gas gun" or "chemical weapon or device" means any weapon of such nature, except a device known as a "self-defense chemical spray." "Self-defense chemical spray" means a device carried solely for purposes of lawful self-defense that is compact in size, designed to be carried on or about the person, and contains not more than two ounces of chemical.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 260 (help) - "Right-to-Carry 2008". National Rifle Association of America, Institute for Legislative Action. 2008-08-19.

- ^ Concealed Weapon / Firearm Summary Report – October 1, 1987 – June 30, 2012, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services – Division of Licensing. Retrieved October 2011.

- License Holder Profile Report, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services – Division of Licensing. Retrieved August 2007.

- 2005–2006 CCW Annual Report, Michigan State Police

- New Federal Report Shows Right-to-Carry Boom (July 20, 2012), NRA Institute for Legislative Affairs

- North Carolina Concealed Handgun Permit Statistics by County – 12/01/1995 through 09/30/2004, North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation

- "Concealed Weapon / Firearm Summary Report – October 1, 1987 – September 30, 2010". Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- An Analysis Of The Arrest Rate Of Texas Concealed Handgun License Holders As Compared To The Arrest Rate Of The Entire Texas Population (1996–1998), Revised to include 1999 data pdf and html

- Adam Winkler, Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America, 2012, cited in "Battleground America: One nation, under the gun", The New Yorker, Jill Lepore, April 23, 2012

- ^ Kranz, Steven W. (2006). "A Survey of State Conceal And Carry Statutes: Can Small Changes Help Reduce the Controversy?". Hamline Law Review. 29 (638).

- Changes Coming to Alabama Gun Laws, WTVM Channel 9, May 22, 2013

- http://handgunlaw.us/states/americansamoa.pdf

- http://handgunlaw.us/states/guam.pdf

- McCune, Greg (July 9, 2013). "Illinois Is Last State to Allow Concealed Carry of Guns", Reuters. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- Jones, Ashby (July 9, 2013). "Illinois Abolishes Ban on Carrying Concealed Weapons", Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- McDermott, Kevin, and Hampel, Paul (July 11, 2013). "Illinois Concealed Carry Now on the Books — But Not Yet in the Holster", St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- DeFiglio, Pam (July 9, 2013). "General Assembly Overrides Veto, Legalizing Concealed Carry in Illinois", Patch Media. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- Md. Gun Law Found Unconstitutional

- Bills. Assembly.state.ny.us (2011-01-13). Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- Kachalsky vs. Cacase. www.saf.org

- ^ "North Carolina ''shall-issue'' laws" (PDF). Jus.state.nc.us. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- http://handgunlaw.us/states/northernmariana.pdf

- ^ "166.291: Issuance of concealed handgun license".

The sheriff of a county, upon a persons application for an Oregon concealed handgun license, upon receipt of the appropriate fees and after compliance with the procedures set out in this section, shall issue the person a concealed handgun license

- ^ "Tennessee ''shall-issue'' laws". Tennessee.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ "Concealed Handgun Licensing Program". Texas Department of Public Safety.

- ^ "Texas Government Code, Chapter 411, Subchapter H. License to carry a concealed handgun, Section 411.172. Eligibility".

- http://handgunlaw.us/states/usvirginislands.pdf

- ^ "Utah ''shall-issue'' laws". Publicsafety.utah.gov. 2010-10-05. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- Concealed Handgun Permit Firearms Safety Class – Virginia Concealed Handgun Permit. Concealed-carry.net. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- "Alaska Concealed Handgun Permits – Permits and Licensing Unit". Dps.state.ak.us. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- "The Vermont Statutes Online". Leg.state.vt.us. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- "Governor Mead Signs Bill Allowed Concealed-Carry Without a Permit". thewyonews.net. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- "Utah lawmaker: Guns should be legal without permit". Deseret News. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- "S.C. Political Briefs". thestate.com. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- Permitless Carry Bill Moves to New Hampshire Senate, NRA-ILA, March 16, 2011. Nraila.org (March 16, 2011). Retrieved on October 16, 2011.

- Clayton E. Cramer and David B. Kopel (1994-10-17). " 'Shall Issue': The New Wave of Concealed Handgun Permit Laws". Independence Institute. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- Clayton E. Cramer & David B. Kopel, " 'Shall Issue': The New Wave of Concealed Handgun Permit Laws", Tennessee Law Review, July 1995. Text Html

- Rhode Island Concealed Carry Permit Information - USACarry

- Snyder, Jeffrey. "Fighting Back: Crime, Self-Defense, and the Right to Carry a Handgun". Cato Institute. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- "Madoff son of a gun Bernie kid on pistol-permit list". NY Post. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- Jo Craven McGinty (February 18, 2011). "The Rich, the Famous, the Armed". The New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- Woollard v. Sheridan, 863 F.Supp 2d 462 (D. Md. 2012)., rev'd sub nom Woollard v. Gallagher, 712 F.3d 865 (4th Cir. 2013).

- Woollard v. Gallagher, 712 F.3d 865 (4th Cir. 2013).

- Woollard v. Gallagher, --- S.Ct. ---- (2013).

- Drake v. Filko, 724 F.3d 426 (3d Cir. 2013).

- ^ Virginia State Police, application for a concealed handgun permit page. Vsp.state.va.us. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- "Florida Statute 790".

- Article IV, Section 1, "Full faith and credit shall be given in each state to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other state."

- 08:27 PM. "''Concealed Carry (CCW) Laws by State'' on". Usacarry.com. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - State of Washington reciprocity. Atg.wa.gov. Retrieved on 2011-10-16.

- "Missouri Attorney General's Office – Concealed Carry Reciprocity".

- "Michigan Attorney General's Office – Concealed Carry Reciprocity".

- Reciprocity - Alaska Concealed Handgun Permits

- "Florida Division of Licensing, DOACS – Concealed Carry Reciprocity".

- "Utah Department of Public Safety – Reciprocity with Other States".

- Non-Resident Applicants Law Change in Utah May 2011

- Colorado Allows Permit Holders to Carry on Campus

- "Nebraska Revised Statute 69-2441". Nebraska Statutes. Nebraska Legislature. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- "Chapter 624, Section 714, Subdivision 17". Minnesota Statutes. Minnesota Revisor of Statutes. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- Deakins, Jacob (Summer 2008). "Guns, Truth, Medicine, and the Constitution" (PDF). Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons. 13 (2). Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- Hetzner, Amy (2011–2012). "Where Angels Tread: Gun-Free School Zone Laws and an Individual Right to Bear Arms". Marquette Law Review. 95: 359–398.

- "Brandishing a Weapon, Gun or Firearm". Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- "LIS > Code of Virginia > 18.2-282". Retrieved 2014-02-19.

- "Title 36 CFR §327.13". Ecfr.gpoaccess.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- National Parks Gun Law Takes Effect in February Washington Post, May 22, 2009.

- Judge Blocks Rule Permitting Concealed Guns In U.S. Parks Washington Post, March 20, 2009.

- "Copy of Injunction" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- "Greenspace". The Los Angeles Times. May 20, 2009.

- Constitution for the United States of America, Article IV, Section 1: "Full faith and credit shall be given in each state to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other state. And the Congress may by general laws prescribe the manner in which such acts, records, and proceedings shall be proved, and the effect thereof."

- Tennessee reciprocity policy "Tennessee now recognizes a facially valid handgun permit, firearms permit, weapons permit, or a license issued by another state according to its terms..."

- Carter, Gregg Lee (2002). Guns in American society: an encyclopedia of history, politics, culture, and the law. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. p. 506. ISBN 1-57607-268-1. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

Justice Brown spotlighted his belief that the guarantee of the right to keep and bear arms was not infringed by laws prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons

- "SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES" (PDF). October term 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Barnes, Robert (October 1, 2009). "Justices to Decide if State Gun Laws Violate Rights". The Washington Post.

- Swickard, Joe (June 4, 2010). "Charges in stray-bullet death: Carjacking victim faces manslaughter rap". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on 2010-06-09.

- "Wayne County judge lessens bond for man accused of killing bystander". The Detroit News. June 28, 2010.

- Castle Doctrine And Self-Defense

- "BEARD V. UNITED STATES, 158 U. S. 550 (1897)". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Booher, Kary (June 8, 2010). "Case highlights concealed carry weapons issues". Springfield News-Leader. Archived from the original on 2010-06-10.

"Missouri is like 48 other states, except the state of Texas, that does not allow deadly force in defense of property," said Randy Gibson, a captain in the Greene County Sheriff's Department.

- CALCRIM No. 3476

- Cal. Penal Code §197 (West 2013.)

- "Sec. 83.001. CIVIL IMMUNITY".

- "18 U.S.C. § 922 : US Code – Section 922: Unlawful acts". Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- "18 U.S.C. § 922 : US Code – Section 922: Unlawful acts, Subsections g and n". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Melissa Topey (June 16, 2010). "Sandusky police arrest accused 7-Eleven shooter". Sandusky Register. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Carrying a Concealed Weapon". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "PROTECTION ORDERS AND FEDERAL FIREARMS PROHIBITIONS" (PDF). Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "STATE v. HOLIFIELD 39 So.3d 853 (2010)". Court of Appeal of Louisiana, First Circuit. June 11, 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Jeff Mason (June 18, 2010). "Cottage Hills: Man arrested on weapons charges, swinging bat at family". kmov.com. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Jeff Morganteen (16 June 2010). "Psychotherapist arraigned on firearms". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Mike Gallagher (June 17, 2010). "25 arrested, 230 guns seized in NM thrift store sting". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "North Carolina". Updated July 2004, August 2005. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "STATE KNIFE LAWS". Compiled in September 1996 for BLADE Magazine. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "?". Associated Press. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions About Concealed Carry in North Carolina". North Carolina Rifle & Pistol Association. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Resident Concealed Handgun Permits". Virginia State Police. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "2923.12 Carrying concealed weapons". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- David Gambacorta (June 17, 2010). "Cops stop ex-NFL receiver Marvin Harrison, take gun". Philadelphia Daily News. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Concealed Handgun Permit Unit". Louisiana State Police. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Revocation, Suspension, or Surrender of Permit". Virginia State Police. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Nina totenberg (March 2, 2010). "Supreme Court To Hear Chicago Gun Rights Case". NPR. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "TEXAS CONCEALED HANDGUN LAWS AND SELECTED STATUTES" (PDF). Texas Department of Public Safety. October 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Steps To Getting Your Texas Concealed Handgun License". texasconcealedhandgundlicense.us. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Espohl, Frank (1997). "The right to carry concealed weapons for self-defense". saf.org. Board of Trustees of Southern Illinois University. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000.

- ^ Ayres, Ian; Donohue, John J. III (April 16, 2003). "Shooting Down the 'More Guns, Less Crime' Hypothesis" (PDF). Stanford Law Review. 55: 1193–1312. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ Hinyub, Chris (June 12, 2010). "More guns, less crime". ivn.us. Foundation for Independent Voter Education (FIVE). Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- "About Crime in the U.S. (CIUS)". FBI. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- Glenn, David (May 9, 2003). "'More Guns, Less Crime' Thesis Rests on a Flawed Statistical Design, Scholars Argue". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 49 (35): A18. Retrieved May 27, 2007.

- "Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review (2004)". p. 2.

- "Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review (2004)" Appendix A Dissent by James Q. Wilson, retrieved January 11, 2006

- National Research Council (National Academy of Sciences), Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review, The National Academies Press, 2005. Chapter 6.

- Abhay Aneja, John J. Donohue III, and Alexandria Zhang, "The Impact of Right-to-Carry Laws and the NRC Report: Lessons for the Empirical Evaluation of Law and Policy", Am Law Econ Rev (Fall 2011) 13(2): 565–631.

- Carlisle E. Moody, John R. Lott Jr., Thomas B. Marvell and Paul R. Zimmerman, "Trust But Verify: Lessons for the Empirical Evaluation of Law and Policy", SSRN Working Paper Series, January 25, 2012.

- Ayres, Ian, and John J. Donohue III (2009). "Yet Another Refutation of the More Guns, Less Crime Hypothesis – With Some Help From Moody and Marvell". Econ Journal Watch. 6 (1): 35–59.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - FBI's Crime in the United States 2008

- "FBI's Crime in the United States 2009". Fbi.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- Concealed Carry Killers, Violence Policy Center

- Expanded Homicide Data, 2011, Federal Bureau of Investigation. "In the UCR Program, justifiable homicide is defined as and limited to: ■ The killing of a felon by a peace officer in the line of duty. ■ The killing of a felon, during the commission of a felony, by a private citizen."

- Philip J. Cook and Jens Ludwig, "National Survey on Private Ownership and Use of Firearms," NIJ Research in Brief, May 1997

- Gary Kleck and Marc Gertz, "Armed Resistance to Crime: The Prevalence and Nature of Self-Defense with a Gun", 86 Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 1, 1995.

Further reading

- 1997 John Lott and David Mustard, "Crime, Deterrence, and Right-to-Carry Concealed Handguns," Journal of Legal Studies.

- 1998 Dan Black and Daniel Nagin, "Do Right-to-Carry Laws Deter Violent Crime?" Journal of Legal Studies.

- 1998 John Lott, "The Concealed-Handgun Debate." Journal of Legal Studies.

- 1998 John Lott, More Guns, Less Crime (U Chicago Press).

- 2000 John Lott, More Guns, Less Crime, Second Edition (U Chicago Press).

- 2003 Ian Ayres and John Donohue, "Shooting Down the ‘More Guns, Less Crime’ Hypothesis, Stanford Law Review.

- 2003 Florenz Plassmann and John Whitley, "Confirming ‘More Guns, Less Crime," Stanford Law Review.

- 2003 Ian Ayres and John Donohue, "The Latest Misfires in Support of the ‘More Guns, Less Crime’ Hypothesis," Stanford Law Review.

- 2003 John Lott, The Bias against Guns (AEI).

- 2004 John Donohue. "Guns, Crime, and the Impact of State Right-to-Carry Laws" Fordham Law Review 73 (2004): 623.

- 2005 Robert Martin Jr., & Richard Legault, "Systematic Measurement Error with State-Level Crime Data: Evidence From the "More Guns, Less Crime" Debate," J. RESEARCH IN CRIME & DELINQUENCY

- 2008 Carlisle E. Moody and Thomas B. Marvell. "The Debate on Shall-Issue Laws," Econ Journal Watch 5.3: 269–293.

- 2009 John Donohue and Ian Ayres. "More Guns, Less Crime Fails Again: The Latest Evidence from 1977–2006" Econ Journal Watch 6.2: 218–238.

External links

- NRA-ILA guide to gun laws

- A very comprehensive guide to gun laws and reciprocity

- Strengthen gun laws, or weaken them?

- Concealed Carry Reciprocity Maps