This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 24.99.192.9 (talk) at 01:12, 26 January 2007 (→The non-human fetus). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:12, 26 January 2007 by 24.99.192.9 (talk) (→The non-human fetus)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Fetus (disambiguation).

A fetus (or foetus, or fœtus) is a developing mammal or other viviparous vertebrate, after the embryonic stage and before birth. The plural is fetuses or, very rarely, foeti.

In humans, a fetus develops from the end of the eighth week after conception, when the major structures and organ systems have formed, until birth. The word fetus was a Latin word having Indo-European roots.

Etymology and spelling variations

The word "fetus" is derived from the Latin fetus, meaning "childbearing", "pregnancy", or "offspring". It has Indo-European roots related to sucking or suckling.

Foetus is an English variation on this, rather than a Latin or Greek word, but has been in use since at least 1594 according to the Oxford English Dictionary, which describes "fetus" as the etymologically preferable spelling. The English variation "foetus" may have originated with an error by Saint Isidore of Seville, in AD 620. The medical community prefers the spelling fetus, but the pseudo-Greek spelling foetus persists in general use, especially in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand.

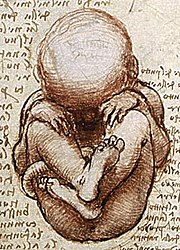

The human fetus

Fetal development

Main article: Fetal developmentDuring the course of the fetal stage, many biological changes occur, most obviously including the size of the fetus. All major structures are already formed in the fetus when the fetal stage begins (at eight weeks after conception) but they continue to grow and become more functional. The fetus is not as sensitive to damage from environmental exposures as the embryo was, though toxic exposures can often cause physiological abnormalities or minor congenital malformation.

At the beginning of the fetal stage (i.e. eight weeks after conception), a human fetus is typically about 30 mm (1.2 inches) in length. However, much human anatomy is in place: hands, feet, head, organs, brain, and the like. The heart has already been beating for five weeks already, and some fingerprint formation can be seen. The risk of miscarriage decreases sharply at the beginning of the fetal stage. Also at this point in pregnancy, the fetus is able to bend fingers around an object; in response to a touch on the foot, the fetus will bend hips and knees (or curl toes) to move away from the touching object. And, at the beginning of the fetal stage, a fetus can hiccup and react to loud noises.

During the third month after conception, the fetus grows to about 8 cm (3.2 inches), with the head being almost half that size. The different appearance of the genitals in males and females becomes pronounced in the ninth week. Integrated brain functioning has been verified about seventy days after conception. Rapid fetal activities are observed by ultrasound in the tenth week, when the fetus rarely pauses for more than five minutes.

By the end of the fourth month, the fetus has reached about 15 cm (6 inches). During the fifth month, the mother can usually feel the fetus moving, and this is called quickening. The more insulated the fetus is (i.e. the larger the body weight of the mother), the later quickening occurs. By the end of the fifth month, the fetus is about 20 cm (8 inches), and this is the earliest point at which medical science has been able to achieve viability, although viability usually occurs somewhat later. A few decades ago, the earliest point of fetal viability was the end of the sixth month, with viability usually occurring at the end of the seventh month.

The fetus is considered full-term at 35 weeks after conception, meaning that it is a good time to be born. It may be 48 to 53 cm (19 to 21 inches) in length, when born.

Fetal development can be interrupted by various factors, including miscarriage, feticide committed by a third party, or abortion chosen by the pregnant woman. In the United States, for example, about 40.7% of induced abortions were fetal abortions instead of embryonic abortions, as of 2002.

Variation in growth

There is much natural variation in the growth of the fetus. Factors affecting fetal growth can be maternal, placental, or fetal.

Maternal factors include maternal size, weight, weight for height, nutritional state, anemia, high environmental noise exposure, cigarette smoking, substance abuse, or uterine blood flow.

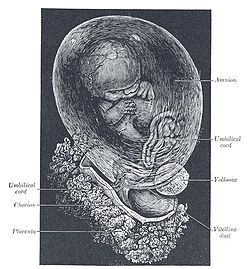

Placental factors include size, microstructure (densities and architecture), umbilical blood flow, transporters and binding proteins, nutrient utilization and nutrient production.

Fetal factors include the fetus genome, nutrient production, and hormone output.

Inappropriate growth can result in low birth weight. If the newborn is small for gestational age, he or she will have an increased risk for perinatal mortality (death shortly after birth), asphyxia, hypothermia, polycythemia, hypocalcemia, immune dysfunction, neurologic abnormalities, and other long-term health problems. This can be the result of fetal growth restriction.

Circulatory system

The circulatory system of a human fetus works differently from that of born humans, mainly because the lungs are not in use: the fetus obtains oxygen and nutrients from the woman through the placenta and the umbilical cord.

Blood from the placenta is carried by the umbilical vein. About half of this enters the ductus venosus and is carried to the inferior vena cava, while the other half enters the liver proper from the inferior border of the liver. The branch of the umbilical vein that supplies the right lobe of the liver first joins with the portal vein. The blood then moves to the right atrium of the heart. In the fetus, there is an opening between the right and left atrium (the foramen ovale), and most of the blood flows from the right into the left atrium, thus bypassing pulmonary circulation. The majority of blood flow is into the left ventricle from where it is pumped through the aorta into the body. Some of the blood moves from the aorta through the internal iliac arteries to the umbilical arteries, and re-enters the placenta, where carbon dioxide and other waste products from the fetus are taken up and enter the woman's circulation.

Some of the blood from the right atrium does not enter the left atrium, but enters the right ventricle and is pumped into the pulmonary artery. In the fetus, there is a special connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta, called the ductus arteriosus, which directs most of this blood away from the lungs (which aren't being used for respiration at this point as the fetus is suspended in amniotic fluid).

Postnatal development

See Adaptation to extrauterine life for more details

With the first breath after birth, the system changes suddenly. The pulmonary resistance is dramatically reduced. More blood moves from the right atrium to the right ventricle and into the pulmonary arteries, and less flows through the foramen ovale to the left atrium. The blood from the lungs travels through the pulmonary veins to the left atrium, increasing the pressure there. The decreased right atrial pressure and the increased left atrial pressure pushes the septum primum against the septum secundum, closing the foramen ovale, which now becomes the fosse ovalis. This completes the separation of the circulatory system into two halves, the left and the right.

The ductus arteriosus normally closes off within one or two days of birth, leaving behind the ligamentum arteriosum. The umbilical vein and the ductus venosus closes off within two to five days after birth, leaving behind the ligamentum teres and the ligamentum venosus of the liver respectively.

Developmental problems

Infants with certain congenital anomalies of the heart can survive only as long as the ductus remains open: in such cases the closure of the ductus can be delayed by the administration of prostaglandins to permit sufficient time for the surgical correction of the anomalies. Conversely, in cases of patent ductus arteriosus, where the ductus does not properly close, drugs that inhibit prostaglandin synthesis can be used to encourage its closure, so that surgery can be avoided.

A developing fetus is highly susceptible to anomalies in its growth and metabolism, increasing the risk of birth defects. One area of concern is the mother's lifestyle choices made during pregnancy. Diet is especially important during the first trimester of development. Studies show that supplementation of the mother's diet with folic acid reduces the risk of spina bifida and other neural tube defects. Another dietary concern is the consumption of breakfast by the mother. This one factor could lead to extended periods of lower than normal nutrients in the mother's blood, leading to a higher risk of prematurity, or other birth defects in the fetus. During this time alcohol consumption may increase the risk of the development of fetal alcohol syndrome, a condition leading to mental retardation in some infants. Smoking during pregnancy may also lead to a low birth weight infant, with a weight of <2500 grams, or 5.5 lbs. Low birth weight is a concern for medical providers due to the tendency of these infants, described as premature by weight, to have a higher risk of secondary medical problems.

References:

Differences from the adult circulatory system

Remnants of the fetal circulation can be found in adults:

| Fetal | Adult |

| foramen ovale | fossa ovalis |

| ductus arteriosus | ligamentum arteriosum |

| extra-hepatic portion of the fetal left umbilical vein | ligamentum teres hepatis (the "round ligament of the liver"). |

| intra-hepatic portion of the fetal left umbilical vein (the ductus venosus) | ligamentum venosum |

| proximal portions of the fetal left and right umbilical arteries | umbilical branches of the internal iliac arteries |

| distal portions of the fetal left and right umbilical arteries | medial umbilical ligaments |

In addition to differences in circulation, the developing fetus also employs a different type of oxygen transport molecule than adults (adults use adult hemoglobin). Fetal hemoglobin enhances the fetus' ability to draw oxygen from the placenta. Its association curve to oxygen is shifted to the left, meaning that it will take up oxygen at a lower concentration than adult hemoglobin will. This enables fetal hemoglobin to absorb oxygen from adult hemoglobin in the placenta, which has a lower pressure of oxygen than at the lungs.

Legal issues

Especially since the 1970s, there has been continuing debate over the "personhood" of the human fetus. Although abortion of a fetus before viability is generally legal in the United States following the case of Roe v. Wade, the third-party-killing of a fetus is often punishable as homicide or feticide, even before viability.

The non-human fetus

| This article's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The fetus of most mammals develops similarly to the Homo sapiens fetus. In the first stages of development, the human fetus is indistinguishable from another mammalian fetus. The anatomy of the area surrounding a fetus, however, is different in litter-bearing animals compared to humans: each fetus is surrounded by placental tissue and is lodged along one of two long uteri instead of the single uterus found in a human female. Development at birth is similar, with animals also having a poorly developed sense of vision and other senses.

References

- Harper, Douglas. (2001). Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- fetus. (n.d.). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- Aronson, Jeff (July 1997). "When I use a word...:Oe no!". British Medical Journal. 315 (1). BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. Retrieved 2006-06-29.

- Marjorie Greenfield, M.D., “Dr. Spock.com". Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- Mark J. Zabinski, Forensic Series Seminar, Pastore Chemical Laboratory, University of Rhode Island (February 2003) (news report retrieved 2007-01-20).

- -Q&A: Miscarriage. (August 6 , 2002). BBC News. Retrieved January 10, 2007.

- Lennart Nilsson. (1990) A Child is Born. - Valman & Pearson, What the Fetus Feels, British Medical Journal, (January 26, 1980).

- Hopson, Fetal Psychology, 31 Psychology Today 44 (October 1998).

- Christopher Vaughan, How Life Begins: the Science of Life in the Womb 74 (1996).

- Peter Steinfels, "Scholar Proposes 'Brain Birth' Law", N. Y. Times (Nov. 8, 1990).

- Geraldine Lux Flanagan, Beginning Life 62 (1996).

See also

- Embryo

- Fetal development

- Pregnancy

- Child

- Superfetation

- Neural development

- Fetoscopy

- Fetal position

- Abortion

| Preceded byEmbryo | Stages of human development Fetus |

Succeeded byInfant |

| Human embryonic development in the first three weeks | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | |||||||||

| Week 2 (Bilaminar) | |||||||||

| Week 3 (Trilaminar) |

| ||||||||