This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dewritech (talk | contribs) at 20:14, 8 December 2021 (clean up, typo(s) fixed: University → university, january → January). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:14, 8 December 2021 by Dewritech (talk | contribs) (clean up, typo(s) fixed: University → university, january → January)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Hungarian physicist and Roman Catholic priestThe native form of this personal name is Jedlik Ányos István. This article uses Western name order when mentioning individuals.

| Ányos István Jedlik | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1800-01-11)11 January 1800 Szimő, Kingdom of Hungary (today Zemné, Slovakia) |

| Died | 13 December 1895(1895-12-13) (aged 95) Győr, Kingdom of Hungary, Austria-Hungary |

| Citizenship | Hungarian |

| Known for | Electric motor, dynamo, self-excitation, impulse generator, cascade connection |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Inventor, engineer, physicist |

Ányos István Jedlik (Template:Lang-hu; Template:Lang-sk; in older texts and publications: Template:Lang-la; 11 January 1800 – 13 December 1895) was a Hungarian inventor, engineer, physicist, and Benedictine priest. He was also a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and author of several books. He is considered by Hungarians and Slovaks to be the unsung father of the dynamo and electric motor.

Career

He was born in Szimő, Kingdom of Hungary (today Zemné, Slovakia). His parents were Ferenc Jedlik and Rozália Szabó. His mother was a member of a Hungarian noble family, while his father's family was of Slovak origin moving in 1720 from Liptó County to Szimő.

Jedlik's education began at high schools in Nagyszombat (today Trnava) and Pressburg (today Bratislava). In 1817 he became a Benedictine, and from that time continued his studies at the schools of that order, where he was known by his Latin name Stephanus Anianus. He lectured at Benedictine schools up to 1839, then for 40 years at the Budapest University of Sciences department of physics-mechanics. Few guessed at that time that his activities would play an important part in bringing up a new generation of physicists. He became the dean of the Faculty of Arts in 1848, and by 1863 he was rector of the university. From 1858 he was a corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and from 1873 was an honorary member. After his retirement, he continued working and spent his last years in complete seclusion at the priory in Győr, where he died.

Scientific work

In 1827, Jedlik started experimenting with electromagnetic rotating devices which he called lightning-magnetic self-rotors, and in 1828 he demonstrated the first device which contained the three main components of practical direct current motors: the stator, rotor, and commutator. In the prototype both the stationary and the revolving parts were electromagnetic. The first electromotor, built in 1828, and Jedlik's operating instructions are kept at the Museum of Applied Arts in Budapest. The motor still works perfectly today. However, Jedlik only reported his invention decades later and the true date of it is uncertain (late December 1827 or early January of 1828).

He was a prolific author. In 1845, Jedlik was the first university professor in the Kingdom of Hungary who began teaching his students in Hungarian instead of Latin. His cousin Gergely Czuczor, a Hungarian linguist, asked him to create a Hungarian technical vocabulary in physics, the first of its kind, by which he became one of its founders.

In the 1850s he conducted optical and wave-mechanical experiments, and at the beginning of the 1860s, he constructed an excellent optical grate.

He was ahead of his contemporaries in his scientific work, but he did not speak about his most important invention, his prototype dynamo, until 1856; it was not until 1861 that he mentioned it in writing in a list of inventory of the university. Although that document might serve as evidence of Jedlik's being the first dynamo, the invention of the dynamo is linked to Siemens's name because Jedlik's invention did not rise to notice at that time.

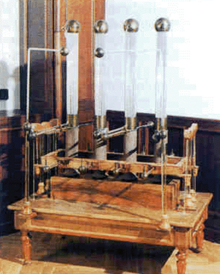

In 1863 he discovered the possibility of voltage multiplication and in 1868 demonstrated it with a "tubular voltage generator", which was successfully displayed at the Vienna World Exposition in 1873. It was an early form of the impulse generators now applied in nuclear research. The jury of the World Exhibition of 1873 in Vienna awarded his voltage multiplying condenser of cascade connection with a prize "For Development". Through this condenser, Jedlik framed the principle of surge generation by cascaded connection. (The cascade connection was another important invention of Ányos Jedlik)

Invention of the Dynamo principle

Jedlik's best known invention is the principle of dynamo self-excitation.

In 1827, Jedlik started experimenting with electromagnetic rotating devices which he called electromagnetic self-rotors. It replaced the permanent magnet designs in the industry.

In the prototype of the single-pole electric starter, both the stationary and the revolving parts were electromagnetic. In essence, the concept is that instead of permanent magnets, two opposed electromagnets induce the magnetic field around the rotor. He formulated the concept of the self-excited dynamo about 1861, six years before Siemens and Wheatstone.

As one side of the coil passes in front of the north pole, crossing the line of force, a current is induced. As the frame rotates further the current diminishes, then arriving at the front of the south pole it rises again but flows in the opposite direction. The frame is connected to a commutator, thus the current always flows in the same direction in the external circuit.

Bibliography

Books for university students

The following are all given in the Hungarian Electronic Library:

- Tentamen publicum e Physica ... ex Institutine primi semestris Aniani Jedlik [Public examination on Physics ... from the first semester education of Ányos Jedlik] (in Latin). Pozsony. 1839.

- Tentamen publicum e Physica quod in regia univers. Hung. e praelectionibus [Public examination on Physics for election to the Royal Hungarian University] (in Latin). Pest: Trattner-Károlyi. 1845.

- Mathesis adplicata [Applied Science] (in Latin). Pest: Kőnyomat.

- Compendium Hydrostaticae et Hydrodinamicae usibus Auditorum Suorum adaptatum per Anianum Jedlik [Compendium of Hydrostatics and Hydrodynamics. Lecture Notes adapted by Ányos Jedlik] (in Latin). Pest: Kőnyomat. 1847.

- Elements of natural science. Vol. 16. Pest: Eisinfels. 1850.

- Viznyugtanhoz tartozó Pótlékok [Supplements for science of still/calm water] (in Hungarian). Pest: Kőnyomat. 1850.

- Goldsmith, Irta (1851). Ányos Jedlik (ed.). Fénytan [Science of Light] (in Hungarian). Pest: Kőnyomat.

- Goldsmith, Irta (1990) . Ányos Jedlik (ed.). Hőtan [Science of Heat] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó.

Contributions by Jedlik in other works:

- Vagács, Caesar, ed. (1854). "A hévmérő s kellékei" [The thermometer and its accessories]. Olvasmány a főgymnasiumi középosztályok [Reading material for grammar school students] (in Hungarian). Hartleben. pp. 259–261.

- ibid., pp. 256–258

- Német – magyar tudományos műszótár a csász. kir. gymnasiumok és reáliskolák számára [German – Hungarian Scientific Dictionary for Imperial and Royal grammar schools and primary schools] (in German and Hungarian). Vol. VIII. Pest: Hekenast. 1858.

- "Ueber die Anwendung des Elektro-Magnetes bei elektro-dynamischen Rotationen" [On the application of electromagnets in electrodynamic rotations]. Aemtlicher Bericht über die XXXII. Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte zu Wien im Sept. 1856 [Report of the 32nd Conference of German Naturalists and Physicists at Vienna, September 1856] (in German). Vienna. 1858. pp. 170–175.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Modification der Grove'schen und Bunsen'schen Batterie" [Modification of the Grove and Bunsen batteries]. Aemtlicher Bericht über die XXXII. Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte zu Wien im Sept. 1856 [Report of the 32nd Conference of German Naturalists and Physicists at Vienna, September 1856] (in German). Vienna. 1858. pp. 176–178.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Egyetemes Magyar Encyclopaedia [Universal Hungarian Encyclopaedia] (in Hungarian). Vol. 1–13. Pest: Szent István Társulat. 1859–1876.

See also

References

- Z dejín vied a techniky na Slovensku (in Slovak). Vol. 11–13. Vydavatel'stvo Slovenskej akadémie vied. 1985. p. 132.

- Simon, Andrew L. (1999). Made in Hungary: Hungarian Contributions to Universal Culture . Simon Publications p.246.

- Teichmann, Jürgen; Stinner, Arthur; Rieß, Falk (eds.). From the itinerant lecturers of the 18th century to popularizing physics in the 21st century – exploring the relationship between learning and entertainment "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Conference sponsored by the University of Oldenburg, Deutsches Museum, University of Winnipeg. - Károly Simonyi: History of the Hungarian physic

- Wagner, Francis S. (1977). Hungarian Contributions to World Civilization. Bratislava: Alpha Publications. ISBN 978-0-912404-04-2.

- Denton, Tom (2004). Automobile Electrical and Electronic Systems. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-6219-2.

- "Bulletin of the International Committee of Historical Sciences". International Committee of Historical Sciences (Presses Universitaires de France). 1933.

- Pledge, H. T. (2007). Science since 1500: A Short History of Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Biology. London: Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-6872-5.

- Teichmann, Jürgen; Stinner, Arthur; Rieß, Falk (eds.). From the itinerant lecturers of the 18th century to popularizing physics in the 21st century – exploring the relationship between learning and entertainment "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Tibenský, Ján (1979). Dejiny vedy a techniky na Slovensku.

Hoci vyrastal v maďarskom prostredí a maďarsky aj cítil, po svojich predkoch bol nepochybne slovenského pôvodu. Translation: Although he grew up in Magyar (Hungarian) environment and also felt Magyar (ethnic Hungarian), he was indisputably of Slovak origin after his ancestors

- Mayer, Farkas (1995). Jedlink Ányos (1800–1895) Családfája ("Family tree") (PDF) (in Hungarian). Magyar Tudománytörténeti Intézet munkatársai (Hungarian Institute of the History of Science, Árpád Király chief ed.). p. 1. Retrieved August 23, 2010. "A Jedlik-ágról, a név alapján, csak azt lehet sejteni, hogy a Vágon tutajjal érkező, Szimőn megtelepedő, itt elmagyarosodott szlovák család lehetett A Jedlik család ősei 1720-ban Liptóból jöttek tutajon Szimőre." ("It is likely that the Jedlik family arrived from Liptó by boat on the River Vág in 1720 and started to live in Szimő.")

- Thompson, Silvanus P., ed. (1891). Electricity and magnetism, translated from the French of Amédée Guillemin. London: MacMillan.

- ^ Heller, Augustus (April 1896). "Anianus Jedlik". Nature. 53 (1379). Norman Lockyer: 516. Bibcode:1896Natur..53..516H. doi:10.1038/053516a0. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- "Technology and Applications Timeline". Electropaedia. May 28, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- Thein, M. (March 22, 2009). "Elektrische Maschinen in Kraftfahrzeugen" [Electrical machinery in motor vehicles] (PDF) (in German). Zwickau: Falkutat der Kraftfahrzeugen. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 14, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- "Elektrische Chronologie". Elektrisiermaschinen im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert – Ein kleines Lexikon [Electrical machinery in the 18th and 19th centuries – a small thesaurus] (in German). University of Regensburg. March 31, 2004. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- "History of Batteries (and other things)". Electropaedia. June 9, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- Lunar Radar

- "Institute - History - the invention of the electric motor 1800-1854". September 25, 2014.

- Sipka, László (Summer 2001). "Innovators and Innovations". Hungarian Quarterly. XLII (162). Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- Sisa, Stephen (1995). "42. The Hungarian Genius". The Spirit of Hungary: A Panorama of Hungarian History and Culture. Ontario, Canada: Vista Books. p. 308. ISBN 0-9628422-0-6. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Singer, Charles Joseph; Williams, Trevor Illtyd (1954). A history of technology. Clarendon Press. p. 187. ISBN 1-56072-432-3. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- O'Dea, William T. (1933). Handbook of the collections illustrating electrical engineering. HMSO. p. 6. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- "Jedlik Ányos (1800–1895) Akadémikus, Fizikaprofesszor. Könyveinek és Cikkeiinek Bibliográfiája" [Ányos Jedlik (1800–1895) Academic, Professor of Physics. Books and Articles] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár (Hungarian Electronic Library). September 6, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

External links

- Biography (in Hungarian)

- Jedlik Biography

- Jedlik honored on Hungarian coin

- Jedlik motor (YouTube video)

- Jedlik's electric motor (YouTube video)

- Scientist of the Day – Ányos Jedlik at Linda Hall Library

| Electric machines | |

|---|---|

| |

| Components and accessories | |

| Generators | |

| Motors | |

| Motor controllers | |

| History, education, recreational use | |

| Experimental, futuristic | |

| Related topics | |

| People | |

- 1800 births

- 1895 deaths

- Hungarian inventors

- Hungarian electrical engineers

- 19th-century Hungarian physicists

- Austro-Hungarian engineers

- Austro-Hungarian inventors

- People associated with electricity

- Hungarian Roman Catholic priests

- Catholic clergy scientists

- Hungarian people of Slovak descent

- Hungarian Benedictines

- 19th-century Roman Catholic priests

- People from Nové Zámky District