This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Muboshgu (talk | contribs) at 01:32, 30 August 2022 (Undid revision 1107442261 by Pulpfiction621 (talk) not relevant to discussing what a recession is). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:32, 30 August 2022 by Muboshgu (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 1107442261 by Pulpfiction621 (talk) not relevant to discussing what a recession is)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Business cycle contraction This article is about a slowdown in economic activity. For other uses, see Recession (disambiguation).

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various events, such as a financial crisis, an external trade shock, an adverse supply shock, the bursting of an economic bubble, or a large-scale anthropogenic or natural disaster. A recession is less severe and prolonged than a depression.

Although the definition of a recession varies between different countries and scholars, two consecutive quarters of decline in a country's real gross domestic product (real GDP) is commonly used as a practical definition of a recession. In the United States, a recession is defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) as "a significant decline in economic activity spread across the market, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales". In the European Union, a recession is defined as "zero or negative growth of GDP in at least two successive quarters". In the United Kingdom, it is defined as negative economic growth for two consecutive quarters.

Governments usually respond to recessions by adopting expansionary macroeconomic policies, such as increasing money supply or increasing government spending and decreasing taxation.

Definitions

In a 1974 article by The New York Times, Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics Julius Shiskin suggested that a rough translation of the bureau's qualitative definition of a recession into a quantitative one that almost anyone can use might run like this:

- In terms of duration – Declines in real gross national product (GNP) for two consecutive quarters; a decline in industrial production over a six-month period.

- In terms of depth – A 1.5% decline in real GNP; a 15% decline in non-agricultural employment; a two-point rise in unemployment to a level of at least 6%.

- In terms of diffusion – A decline in non-agricultural employment in more than 75% of industries, as measured over six-month spans, for six months or longer.

Over the years, some commentators dropped most of Shiskin's "recession-spotting" criteria for the simplistic rule-of-thumb of a decline in real GNP for two consecutive quarters.

In the United States, the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is generally seen as the authority for dating US recessions. The NBER, a private economic research organization, defines an economic recession as: "a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales". The NBER is considered the official arbiter of recession start and end dates for the United States. The Bureau of Economic Analysis, an independent federal agency that provides official macroeconomic and industry statistics, says "the often-cited identification of a recession with two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth is not an official designation" and that instead, "The designation of a recession is the province of a committee of experts at the National Bureau of Economic Research".

The European Union adopted a definition similar to that of the NBER, using GDP alongside additional macroeconomic variables such as employment and other measures to assess the depth of decline in economic activity.

Recessions in the United Kingdom are generally defined as two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth, as measured by the seasonal adjusted quarter-on-quarter figures for real GDP.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines a recession as a period of at least two years during which the cumulative output gap reaches at least 2% of GDP, and the output gap is at least 1% for at least one year.

Attributes

A recession has many attributes that can occur simultaneously and includes declines in component measures of economic activity (GDP) such as consumption, investment, government spending, and net export activity. These summary measures reflect underlying drivers such as employment levels and skills, household savings rates, corporate investment decisions, interest rates, demographics, and government policies.

Economist Richard C. Koo wrote that under ideal conditions, a country's economy should have the household sector as net savers and the corporate sector as net borrowers, with the government budget nearly balanced and net exports near zero.

A severe (GDP down by 10%) or prolonged (three or four years) recession is referred to as an economic depression, although some argue that their causes and cures can be different. As an informal shorthand, economists sometimes refer to different recession shapes, such as V-shaped, U-shaped, L-shaped and W-shaped recessions.

Type of recession or shape

Main article: Recession shapesThe type and shape of recessions are distinctive. In the US, v-shaped, or short-and-sharp contractions followed by rapid and sustained recovery, occurred in 1954 and 1990–91; U-shaped (prolonged slump) in 1974–75, and W-shaped, or double-dip recessions in 1949 and 1980–82. Japan's 1993–94 recession was U-shaped and its 8-out-of-9 quarters of contraction in 1997–99 can be described as L-shaped. Korea, Hong Kong and South-east Asia experienced U-shaped recessions in 1997–98, although Thailand's eight consecutive quarters of decline should be termed L-shaped.

Psychological aspects

Recessions have psychological and confidence aspects. For example, if companies expect economic activity to slow, they may reduce employment levels and save money rather than invest. Such expectations can create a self-reinforcing downward cycle, bringing about or worsening a recession. Consumer confidence is one measure used to evaluate economic sentiment. The term animal spirits has been used to describe the psychological factors underlying economic activity. Keynes, in his The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, was the first economist to claim that such emotional mindsets significantly affect the economy. Economist Robert J. Shiller wrote that the term "refers also to the sense of trust we have in each other, our sense of fairness in economic dealings, and our sense of the extent of corruption and bad faith. When animal spirits are on ebb, consumers do not want to spend and businesses do not want to make capital expenditures or hire people." Behavioral economics has also explained many psychological biases that may trigger a recession including the availability heuristic, the money illusion, and normalcy bias.

Balance sheet recession

Main article: Balance sheet recessionExcessive levels of indebtedness or the bursting of a real estate or financial asset price bubble can cause what is called a "balance sheet recession". This occurs when large numbers of consumers or corporations pay down debt (i.e., save) rather than spend or invest, which slows the economy. The term balance sheet derives from an accounting identity that holds that assets must always equal the sum of liabilities plus equity. If asset prices fall below the value of the debt incurred to purchase them, then the equity must be negative, meaning the consumer or corporation is insolvent. Economist Paul Krugman wrote in 2014 that "the best working hypothesis seems to be that the financial crisis was only one manifestation of a broader problem of excessive debt—that it was a so-called "balance sheet recession". In Krugman's view, such crises require debt reduction strategies combined with higher government spending to offset declines from the private sector as it pays down its debt.

For example, economist Richard Koo wrote that Japan's "Great Recession" that began in 1990 was a "balance sheet recession". It was triggered by a collapse in land and stock prices, which caused Japanese firms to have negative equity, meaning their assets were worth less than their liabilities. Despite zero interest rates and expansion of the money supply to encourage borrowing, Japanese corporations in aggregate opted to pay down their debts from their own business earnings rather than borrow to invest as firms typically do. Corporate investment, a key demand component of GDP, fell enormously (22% of GDP) between 1990 and its peak decline in 2003. Japanese firms overall became net savers after 1998, as opposed to borrowers. Koo argues that it was massive fiscal stimulus (borrowing and spending by the government) that offset this decline and enabled Japan to maintain its level of GDP. In his view, this avoided a U.S. type Great Depression, in which U.S. GDP fell by 46%. He argued that monetary policy was ineffective because there was limited demand for funds while firms paid down their liabilities. In a balance sheet recession, GDP declines by the amount of debt repayment and un-borrowed individual savings, leaving government stimulus spending as the primary remedy.

Krugman discussed the balance sheet recession concept during 2010, agreeing with Koo's situation assessment and view that sustained deficit spending when faced with a balance sheet recession would be appropriate. However, Krugman argued that monetary policy could also affect savings behavior, as inflation or credible promises of future inflation (generating negative real interest rates) would encourage less savings. In other words, people would tend to spend more rather than save if they believe inflation is on the horizon. In more technical terms, Krugman argues that the private sector savings curve is elastic even during a balance sheet recession (responsive to changes in real interest rates), disagreeing with Koo's view that it is inelastic (non-responsive to changes in real interest rates).

A July 2012 survey of balance sheet recession research reported that consumer demand and employment are affected by household leverage levels. Both durable and non-durable goods consumption declined as households moved from low to high leverage with the decline in property values experienced during the subprime mortgage crisis. Further, reduced consumption due to higher household leverage can account for a significant decline in employment levels. Policies that help reduce mortgage debt or household leverage could therefore have stimulative effects.

Liquidity trap

A liquidity trap is a Keynesian theory that a situation can develop in which interest rates reach near zero (zero interest-rate policy) yet do not effectively stimulate the economy. In theory, near-zero interest rates should encourage firms and consumers to borrow and spend. However, if too many individuals or corporations focus on saving or paying down debt rather than spending, lower interest rates have less effect on investment and consumption behavior; increasing the money supply is like "pushing on a string". Economist Paul Krugman described the U.S. 2009 recession and Japan's lost decade as liquidity traps. One remedy to a liquidity trap is expanding the money supply via quantitative easing or other techniques in which money is effectively printed to purchase assets, thereby creating inflationary expectations that cause savers to begin spending again. Government stimulus spending and mercantilist policies to stimulate exports and reduce imports are other techniques to stimulate demand. He estimated in March 2010 that developed countries representing 70% of the world's GDP were caught in a liquidity trap.

Paradoxes of thrift and deleveraging

Behavior that may be optimal for an individual (e.g., saving more during adverse economic conditions) can be detrimental if too many individuals pursue the same behavior, as ultimately, one person's consumption is another person's income. Too many consumers attempting to save (or pay down debt) simultaneously is called the paradox of thrift and can cause or deepen a recession. Economist Hyman Minsky also described a "paradox of deleveraging" as financial institutions that have too much leverage (debt relative to equity) cannot all de-leverage simultaneously without significant declines in the value of their assets.

In April 2009, U.S. Federal Reserve Vice Chair Janet Yellen discussed these paradoxes: "Once this massive credit crunch hit, it didn't take long before we were in a recession. The recession, in turn, deepened the credit crunch as demand and employment fell, and credit losses of financial institutions surged. Indeed, we have been in the grips of precisely this adverse feedback loop for more than a year. A process of balance sheet deleveraging has spread to nearly every corner of the economy. Consumers are pulling back on purchases, especially durable goods, to build their savings. Businesses are cancelling planned investments and laying off workers to preserve cash. And financial institutions are shrinking assets to bolster capital and improve their chances of weathering the current storm. Once again, Minsky understood this dynamic. He spoke of the paradox of deleveraging, in which precautions that may be smart for individuals and firms—and indeed essential to return the economy to a normal state—nevertheless magnify the distress of the economy as a whole."

Predictors

Main article: Inverted yield curveA handful of measures exist that are held to generally predict the possibility of a recession:

- The U.S. Conference Board's Present Situation Index year-over-year change turns negative by more than 15 points before a recession.

- The U.S. Conference Board Leading Economic Indicator year-over-year change turns negative before a recession.

- When the CFNAI Diffusion Index drops below the value of −0.35, then there is an increased probability of the beginning a recession. Usually, the signal happens in the three months of the recession. The CFNAI Diffusion Index signal tends to happen about one month before a related signal by the CFNAI-MA3 (3-month moving average) drops below the −0.7 level. The CFNAI-MA3 correctly identified the 7 recessions between March 1967 – August 2019, while triggering only 2 false alarms.

Except for the above, there are no known completely reliable predictors. Analysis by Prakash Loungani of the International Monetary Fund found that only two of the sixty recessions around the world during the 1990s had been predicted by a consensus of economists one year earlier, while there were zero consensus predictions one year earlier for the 49 recessions during 2009.

However, the following are considered possible predictors:

- The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago posts updates of the Brave-Butters-Kelley Indexes (BBKI).

- The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis posts the Weekly Economic Index (Lewis-Mertens-Stock) (WEI).

- The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis posts the Smoothed U.S. Recession Probabilities (RECPROUSM156N).

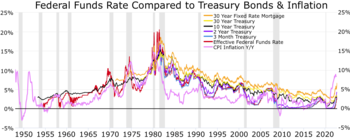

- Inverted yield curve, the model developed by economist Jonathan H. Wright, uses yields on 10-year and three-month Treasury securities as well as the Fed's overnight funds rate. Another model developed by Federal Reserve Bank of New York economists uses only the 10-year/three-month spread.

- The three-month change in the unemployment rate and initial jobless claims. U.S. unemployment index defined as the difference between the 3-month average of the unemployment rate and the 12-month minimum of the unemployment rate. Unemployment momentum and acceleration with Hidden Markov model.

- Index of Leading (Economic) Indicators (includes some of the above indicators).

- Lowering of asset prices, such as homes and financial assets, or high personal and corporate debt levels.

- Commodity prices may increase before recessions, which usually hinders consumer spending by making necessities like transportation and housing costlier. This will tend to constrict spending for non-essential goods and services. Once the recession occurs, commodity prices will usually reset to a lower level.

- Increased income inequality.

- Decreasing recreational vehicle shipments.

- Declining trucking volumes.

- The S&P 500 and BBB bond spread.

Government responses

See also: Stabilization policyKeynesian economists favor the use of expansionary macroeconomic policy during recessions to increase aggregate demand. Strategies favored for moving an economy out of a recession vary depending on which economic school the policymakers follow. Monetarists, exemplified by economist Milton Friedman, would favor the use of limited expansionary monetary policy, while Keynesian economists may advocate increased government spending to spark economic growth. Supply-side economists promote tax cuts to stimulate business capital investment. For example, the Trump administration claimed that lower effective tax rates on new investment imposed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 would raise investment, thereby making workers more productive and raising output and wages. Investment patterns in the United States through 2019, however, indicated that the supply-side incentives of the TCJA had little effect on investment growth. Although investments increased after 2017, much of the increase was a response to oil prices, and investment in other sectors had negligible growth.

Monetarist economists have argued that objectives of monetary policy, i.e., controlling the money supply to influence interest rates, are best achieved by targeting the growth rate of the money supply. They maintain that money may affect output in the short term but that in the long run, expansionary monetary policy leads to inflation only. Keynesian economists have mostly adopted this analysis, modifying the theory with better integration of short and long run trends and an understanding that a change in the money supply "affects only nominal variables in the economy, such as prices and wages, and has no effect on real variables, like employment and output". The Federal Reserve traditionally uses monetary accommodation, a policy instrument of lowering its main benchmark interest rate, to accommodate sudden supply-side shifts in the economy. When the federal funds rate reaches the boundary of an interest rate of 0%, called the zero lower bound, the government resorts to unconventional monetary policy to stimulate recovery.

Gauti B. Eggertsson of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, using a New Keynesian macroeconomic model for policy analysis, writes that cutting taxes on labor or capital is contractionary under certain circumstances, such as those that prevailed following the economic crisis of 2008, and that temporarily increasing government spending at such times has much larger effects than under normal conditions. He says other forms of tax cuts, such as a reduction in sales taxes and investment tax credits, e.g., in the context of Japan's "Great Recession", are also very effective. Eggertsson infers from his analysis that contractionary effects of labor and capital tax cuts, and the strong expansionary effect of government spending, are peculiar to the unusual environment created by zero interest rates. He asserts that with positive interest rates a labor tax cut is expansionary, per the established literature, but at zero interest rates, it reverses and tax cuts become contractionary. Further, while capital tax cuts are inconsequential in his model with a positive interest rate, they become strongly negative at zero, and the multiplier of government spending is then almost five times larger.

Paul Krugman wrote in December 2010 that significant, sustained government spending was necessary because indebted households were paying down debts and unable to carry the U.S. economy as they had previously: "The root of our current troubles lies in the debt American families ran up during the Bush-era housing bubble...highly indebted Americans not only can't spend the way they used to, they're having to pay down the debts they ran up in the bubble years. This would be fine if someone else were taking up the slack. But what's actually happening is that some people are spending much less while nobody is spending more—and this translates into a depressed economy and high unemployment. What the government should be doing in this situation is spending more while the private sector is spending less, supporting employment while those debts are paid down. And this government spending needs to be sustained..."

John Maynard Keynes believed that government institutions could stimulate aggregate demand in a crisis:

Keynes showed that if somehow the level of aggregate demand could be triggered, possibly by the government printing currency notes to employ people to dig holes and fill them up, the wages that would be paid out would resuscitate the economy by generating successive rounds of demand through the multiplier process.

— Anatomy of the Financial Crisis: Between Keynes and Schumpeter, Economic and Political Weekly

Stock market

Some recessions have been anticipated by stock market declines. In Stocks for the Long Run, Siegel mentions that since 1948, ten recessions were preceded by a stock market decline, by a lead time of 0 to 13 months (average 5.7 months), while ten stock market declines of greater than 10% in the Dow Jones Industrial Average were not followed by a recession.

The real estate market also usually weakens before a recession. However, real estate declines can last much longer than recessions.

Since the business cycle is very hard to predict, Siegel argues that it is not possible to take advantage of economic cycles for timing investments. Even the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) takes a few months to determine if a peak or trough has occurred in the US.

U.S. politics

An administration generally gets credit or blame for the state of economy during its time in office; this state of affairs has caused disagreements about how particular recessions actually started.

For example, the 1981 recession is thought to have been caused by the tight-money policy adopted by Paul Volcker, chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, before Ronald Reagan took office. Reagan supported that policy. Economist Walter Heller, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers in the 1960s, said that "I call it a Reagan-Volcker-Carter recession."

Consequences

Unemployment

Unemployment is particularly high during a recession. Many economists working within the neoclassical paradigm argue that there is a natural rate of unemployment which, when subtracted from the actual rate of unemployment, can be used to estimate the GDP gap during a recession. In other words, unemployment never reaches 0%, so it is not a negative indicator of the health of an economy, unless it exceeds the "natural rate", in which case the excess corresponds directly to a loss in the GDP.

The full impact of a recession on employment may not be felt for several quarters. After recessions in Britain in the 1980s and 1990s, it took five years for unemployment to fall back to its original levels. Employment discrimination claims rise during a recession.

Business

Productivity tends to fall in the early stages of a recession, then rises again as weaker firms close. The variation in profitability between firms rises sharply. The fall in productivity could also be attributed to several macro-economic factors, such as the loss in productivity observed across UK due to Brexit, which may create a mini-recession in the region. Global epidemics, such as COVID-19, could be another example, since they disrupt the global supply chain or prevent movement of goods, services and people.

Recessions have also provided opportunities for anti-competitive mergers, with a negative impact on the wider economy; the suspension of competition policy in the United States in the 1930s may have extended the Great Depression.

Social effects

The living standards of people dependent on wages and salaries are not more affected by recessions than those who rely on fixed incomes or welfare benefits. The loss of a job is known to have a negative impact on the stability of families, and individuals' health and well-being. Fixed income benefits receive small cuts which make it tougher to survive.

History

Global

Main article: Global recessionAccording to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), "Global recessions seem to occur over a cycle lasting between eight and 10 years." The IMF takes many factors into account when defining a global recession. Until April 2009, IMF several times communicated to the press, that a global annual real GDP growth of 3.0% or less in their view was "equivalent to a global recession".

By this measure, six periods since 1970 qualify: 1974–1975, 1980–1983, 1990–1993, 1998, 2001–2002, and 2008–2009. During what IMF in April 2002 termed the past three global recessions of the last three decades, global per capita output growth was zero or negative, and IMF argued—at that time—that because of the opposite being found for 2001, the economic state in this year by itself did not qualify as a global recession.

In April 2009, IMF had changed their Global recession definition to "A decline in annual per‑capita real World GDP (purchasing power parity weighted), backed up by a decline or worsening for one or more of the seven other global macroeconomic indicators: Industrial production, trade, capital flows, oil consumption, unemployment rate, per‑capita investment, and per‑capita consumption." By this new definition, a total of four global recessions took place since World War II: 1975, 1982, 1991 and 2009. All of them only lasted one year, although the third would have lasted three years (1991–93) if IMF as criteria had used the normal exchange rate weighted per‑capita real World GDP rather than the purchase power parity weighted per‑capita real World GDP.

In 2020, the COVID-19 lockdowns and other precautions taken in early 2020 drove the global economy into a recession, the second largest global recession in recent history.

Australia

As a result of late 1920s profit issues in agriculture and cutbacks, 1931–1932 saw Australia's biggest recession in its entire history. It fared better than other nations that underwent depressions, but their poor economic states influenced Australia, which depended on them for export, as well as foreign investments. The nation also benefited from greater productivity in manufacturing, facilitated by trade protection, which also helped with lessening the effects.

The economy had gone into a brief recession in 1961 because of a credit squeeze. Australia was facing a rising level of inflation in 1973, caused partially by the oil crisis happening in that same year, which brought inflation at a 13% increase. Economic recession hit by the middle of the year 1974, with no change in policy enacted by the government as a measure to counter the economic situation of the country. Consequently, the unemployment level rose and the trade deficit increased significantly.

Another recession—the most recent one to date—came at the beginning of the 1990s as the result of a major stock collapse in October 1987, referred to now as Black Monday. Although the collapse was larger than the one in 1929, the global economy recovered quickly, but North America still suffered a decline in lumbering savings and loans, which led to a crisis. The recession was not limited to the United States, but it also affected partnering nations such as Australia. The unemployment level increased to 10.8%, employment declined by 3.4% and the GDP also decreased as much as 1.7%. Inflation, however, was successfully reduced.

Australia faced recession in 2020 due to the impact of huge bush fires and the COVID-19 pandemic's effect on tourism and other important aspects of the economy.

European Union

The Eurozone experienced a recession in 2012: the economies of the 17-nation region failed to grow during any quarter of the 2012 calendar year. The recession deepened during the final quarter of the year, with the French, German and Italian economies all affected.

United Kingdom

Main article: List of recessions in the United KingdomThe most recent recession to affect the United Kingdom was the 2020 recession attributed to the COVID-19 global pandemic, the first recession since the Great Recession.

United States

Main article: List of recessions in the United States

According to economists, since 1854, the U.S. has encountered 32 cycles of expansions and contractions, with an average of 17 months of contraction and 38 months of expansion. From 1980 to 2018 there have been only eight periods of negative economic growth over one fiscal quarter or more, and four periods considered recessions:

- July 1981 – November 1982: 15 months

- July 1990 – March 1991: 8 months

- March 2001 – November 2001: 8 months

- December 2007 – June 2009: 18 months

For the last three of these recessions, the NBER decision has approximately conformed with the definition involving two consecutive quarters of decline. While the 2001 recession did not involve two consecutive quarters of decline, it was preceded by two quarters of alternating decline and weak growth.

Since then, then NBER has also declared a 2-month COVID-19 recession for February 2020 – April 2020.

In July 2022, the NBER released a statement regarding declaring a recession following a second consecutive quarter of shrinking GDP, "There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions".

NBER has sometimes declared a recession before a second quarter of GDP shrinkage has been reported, but beginnings and endings can also be declared over a year after they are reckoned to have occurred. In 1947, NBER did not declare a recession despite two quarters of declining GDP, due to strong economic activity reported for employment, industrial production, and consumer spending.

Late 2000s

Main article: Great RecessionOfficial economic data shows that a substantial number of nations were in recession as of early 2009. The US entered a recession at the end of 2007, and 2008 saw many other nations follow suit. The US recession of 2007 ended in June 2009 as the nation entered the current economic recovery. The timeline of the Great Recession details the many elements of this period.

United States

The United States housing market correction (a consequence of the United States housing bubble) and subprime mortgage crisis significantly contributed to a recession.

The 2007–2009 recession saw private consumption fall for the first time in nearly 20 years. This indicated the depth and severity of the recession. With consumer confidence so low, economic recovery took a long time. Consumers in the U.S. were hit hard by the Great Recession, with the value of their houses dropping and their pension savings decimated on the stock market.

U.S. employers shed 63,000 jobs in February 2008, the most in five years. Former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan said on 6 April 2008 that "There is more than a 50 percent chance the United States could go into recession." On 1 October, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that an additional 156,000 jobs had been lost in September. On 29 April 2008, Moody's declared that nine US states were in a recession. In November 2008, employers eliminated 533,000 jobs, the largest single-month loss in 34 years. In 2008, an estimated 2.6 million U.S. jobs were eliminated.

The unemployment rate in the U.S. grew to 8.5% in March 2009, and there were 5.1 million job losses by March 2009 since the recession began in December 2007. That was about five million more people unemployed compared to just a year prior, which was the largest annual jump in the number of unemployed persons since the 1940s.

Although the US economy grew in the first quarter by 1%, by June 2008 some analysts stated that due to a protracted credit crisis and "rampant inflation in commodities such as oil, food, and steel", the country was nonetheless in a recession. The third quarter of 2008 brought on a GDP retraction of 0.5%, the biggest decline since 2001. The 6.4% decline in spending during Q3 on non-durable goods, like clothing and food, was the largest since 1950.

A November 2008 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia based on the survey of 51 forecasters, suggested that the recession started in April 2008 and would last 14 months. They projected real GDP declining at an annual rate of 2.9% in the fourth quarter and 1.1% in the first quarter of 2009. These forecasts represented significant downward revisions from the forecasts of three months prior.

A December 2008 report from the National Bureau of Economic Research stated that the U.S. had been in a recession since December 2007, when economic activity peaked, based on several measures including job losses, declines in personal income, and declines in real GDP. By July 2009, a growing number of economists believed that the recession may have ended. The National Bureau of Economic Research announced on 20 September 2010 that the 2008/2009 recession ended in June 2009, making it the longest recession since World War II. Prior to the start of the recession, it appears that no known formal theoretical or empirical model was able to accurately predict the advance of this recession, except for minor signals in the sudden rise of forecasted probabilities, which were still well under 50%.

See also

- Credit crunch

- Deflation

- Depression

- Disinflation

- Economic collapse

- Economic stagnation

- Flooding the market

- Foreclosure

- Inventory bounce

- List of recessions in the United States

- Overproduction

- Stagflation

- Underconsumption

- COVID-19 recession

References

- "Recession". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- Recession definition. Microsoft Corporation. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 March 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Claessens, Stijn (17 March 2009). "Back to Basics: What Is a Recession?". Finance & Development. 46 (1). doi:10.5089/9781451953688.022.A021 (inactive 31 July 2022). Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - "Recession". Reserve Bank of Australia. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- Mankiw, Greg (1997). "The Data of Macroeconomics". Principles of Economics (9th ed.). SSBH. p. 504. ISBN 978-0-357-03831-4.

- "The NBER's Recession Dating Procedure". nber.org. 7 January 2008. Archived from the original on 12 January 2008.

- "Recession in the EU: its impact on retail trade". Eurostat. 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Q&A: What is a recession?". BBC News. 8 July 2008. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Glossary of Treasury terms". HM Treasury. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- Shiskin, Julius (1 December 1974). "Points of View". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- Dale, Edwin L. Jr (6 April 1974). "U.S. to Broaden the Base Of Consumer Price Index". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 July 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- Silk, Leonard (28 August 1974). "Recession: Some Criteria Missing, So Far". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 July 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- Lakshman, Achuthan; Banerji, Anirvan (7 May 2008). "The risk of redefining recession". CNN Money. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Anstey, Chris (28 July 2022). "'Technical Recession' Sets Up Washington War of the Words". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- Cox, Jeff (28 July 2022). "The economy may look like it's in recession, but we still don't know for sure". CNBC. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- Jacobsen, Louis (26 July 2022). "What exactly is a recession? Sorting out a confusing topic". PolitiFact. Archived from the original on 27 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- Loe, Megan; Lewis, Brandon (28 July 2022). "Yes, there is an official definition of a recession". KUSA.com. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "Recession | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)". www.bea.gov. Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- "FAQ | EABCN". eabcn.org. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- "The CEPR and NBER Approaches". eabcn.org. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- "OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2008 Issue 2". oecd-ilibrary.org.

- ^ Koo, Richard (2009). The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics-Lessons from Japan's Great Recession. John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-470-82494-8.

- ^ Koo, Richard C. (12 December 2011). "The world in balance sheet recession: causes, cure, and politics" (PDF). Real-World Economics Review (58): 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- "What is the difference between a recession and a depression?" Archived 23 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine Saul Eslake Nov 2008

- Kaur, Rajwant; Sidhu, A.S. (Spring 2012). Sarkar, Siddhartha (ed.). "Global Recession and Its Impact on Foreign Trade in India". International Journal of Afro-Asian Studies. 3 (1). Universal-Publishers: 62. ISBN 9781612336084.

- "Key Indicators 2001: Growth and Change in Asia and the Pacific". ADB.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- Samuelson, Robert J. (14 June 2010). "Our economy's crisis of confidence". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "The Conference Board – Consumer Confidence Survey Press Release – May 2010". Conference-board.org. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Akerlof, George A.; Shiller, Robert J. (2010). Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Princeton University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4008-3472-3.

- Shiller, Robert J. (27 January 2009). "Animal Spirits Depend on Trust". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- How to be an Adult (13 May 2020). "Psychological Biases and Errors that led to historic bubbles and crashes". Medium. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Jupe, Robert (2014). "Accounting, balance sheet". In Michie, Jonathan (ed.). Reader's Guide to the Social Sciences. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-135-93226-8.

- Krugman, Paul (10 July 2014). "Does He Pass the Test? 'Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises' by Timothy Geithner". New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- White, Gregory (14 April 2010). "Presentation by Richard Koo – The Age of Balance Sheet Recessions". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Krugman, Paul (17 August 2010). "Notes On Koo (Wonkish)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Krugman, Paul (18 November 2010). "Debt, deleveraging, and the liquidity trap". Voxeu.org). Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Krugman, Paul (6 July 2012). "Grim Natural Experiments". Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Konczal, Mike (3 July 2012). "New Report: A Literature Summary on New Balance-Sheet Recession Research". Next New Deal. Roosevelt Institute. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- Eggertsson, Gauti B. (2018). "Liquidity Trap". The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 7929–7936. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_2482. ISBN 978-1-349-95189-5.

- Correia, Isabel; Farhi, Emmanuel; Nicolini, Juan Pablo; Teles, Pedro (August 2012). "Unconventional Fiscal Policy at the Zero Bound: Working Paper 698" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. p. 1. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Krugman, Paul (2009). The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. W.W. Norton Company Limited. ISBN 978-0-393-07101-6.

- "How Much of the World is in a Liquidity Trap?". Krugman.blogs.nytimes.com. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Lipsey, Richard G.; Harbury, Colin (1992). First Principles of Economics. Oxford University Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-297-82120-5.

- ^ "A Minsky Meltdown: Lessons for Central Bankers". Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco speeches. 16 April 2009. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Consumer Confidence: A Useful Indicator of … the Labor Market? Archived 14 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

Jason Bram, Robert Rich, and Joshua Abel ... Conference Board's Present Situation Index

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Wall Street starts 2017 with tailwind | By Juergen Buettner | 4 January 2017 | Chart 1: Consumer Confidence Index and Historically Shocks". Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Consumer Confidence Drops – Why Does It Matter? Archived 18 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine Forbes. 27 June 2019. Brad McMillan.

- "Gundlach: We don't see a recession on the horizon. But there's bad news..." Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Seeking Alpha | Take Me To Your Leader: Analyzing The Latest Leading Indicators | by −1.9% | 24 September 2019".

- "Background on the Chicago Fed National Activity Index | Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago | 19 September 2019" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Grim Stock Signals Piling Up as Wall Street Mulls Recession Odds". Bloomberg L.P. 25 November 2018. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- A Estrella, FS Mishkin (1995). "Predicting U.S. Recessions: Financial Variables as Leading Indicators" (PDF). Review of Economics and Statistics. 80. MIT Press: 45–61. doi:10.1162/003465398557320. S2CID 11641969. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "A 'Big Data' View of the U.S. Economy: Introducing the Brave-Butters-Kelley Indexes – Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago". chicagofed.org. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Weekly Economic Index (Lewis-Mertens-Stock)". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 5 January 2008. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- "Smoothed U.S. Recession Probabilities". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 1 February 1967. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Ulatan, Jeffrey (3 July 2020). "2020 Recession Signals, After US-Iran Airstrike. Vanguard ETF Best Performing Funds for 2020". Harvard Dataverse. doi:10.7910/DVN/AWWQPN.

- Grading Bonds on Inverted Curve Archived 7 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine By Michael Hudson

- Wright, Jonathan H., The Yield Curve and Predicting Recessions Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine (March 2006). FEDs Working Paper No. 2006-7.

- "The Yield Curve as a Leading Indicator". newyorkfed.org. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 2020. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Park, B.U., Simar, L. & Zelenyuk, V. (2020) "Forecasting of recessions via dynamic probit for time series: replication and extension of Kauppi and Saikkonen (2008)" Archived 23 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Empirical Economics 58, 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01708-2 Archived 14 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 19 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine Using the U.S. Treasury Yield Curve to predict S&P 500 returns and U.S. recessions | Theodore Gregory Hanks | Pennsylvania State University, Schreyer Honors College Department of Finance | Spring 2012

- "Labor Model Predicts Lower Recession Odds". The Wall Street Journal. 28 January 2008. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Sahm, Claudia (6 May 2019). "Direct Stimulus Payments to Individuals" (PDF). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Lihn, Stephen H. T. (10 August 2019). "Real-time Recession Probability with Hidden Markov Model and Unemployment Momentum". SSRN 3435667.

- Leading Economic Indicators Suggest U.S. In Recession Archived 6 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine 21 January 2008

- "Income and wealth inequality make recessions worse, research reveals". phys.org. 2016. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Neves, Pedro Cunha; Afonso, Óscar; Silva, Sandra Tavares (February 2016). "A Meta-Analytic Reassessment of the Effects of Inequality on Growth". World Development. 78: 386–400. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.038.

- Raice, Shayndi (19 August 2019). "An Economic Warning Sign: RV Shipments Are Slipping". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Premack, Rachel. "The "bloodbath" in America's trucking industry has officially spilled over to the rest of the economy". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- "Cass Freight Index Report" (PDF). August 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Archived 6 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine JPMorgan | The US Economic Outlook | Feb. 2020 | Page 22]

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Ocampo, José Antonio, eds. (2008). Capital Market Liberalization and Development. OUP Oxford. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-19-923058-7.

- Ahuja, H.L. (2019). "Monetarism and Friedman's Restatement of Quantity Theory of Money". Macroeconomics, 20e. S. Chand Publishing. p. 527. ISBN 978-93-5283-732-8.

- Thornton, Saranna (2018). Bucking The Deficit: Economic Policymaking In America. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-429-97052-8.

- Mason, J.W (2020). "Chapter 1: Macroeconomic lessons from the past decade". In MacLean, Brian K.; Bougrine, Hassan; Rochon, Louis-Philippe (eds.). Aggregate Demand and Employment: International Perspectives. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-78643-205-6.

- Gale, William G.; Haldeman, Claire (6 July 2021). "Searching for supply-side effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act" (PDF). Brookings. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Jahan, Sarwat; Mahmud, Ahmed Saber; Papageorgiou, Chris (September 2014). "What Is Keynesian Economics? - Back to Basics" (PDF). Finance & Development. 51 (1): 54.

- Jahan, Sarwat; Papageorgiou, Chris (March 2014). "What Is Monetarism? - Back to Basics - Finance & Development, March 2014" (PDF). Finance and Development. 51 (1): 38.

- Skaperdas, Arsenios (7 July 2017). "How Effective is Monetary Policy at the Zero Lower Bound? Identification Through Industry Heterogeneity" (PDF). pp. 2–3.

- Eggertsson, Gauti B. (1 January 2011). "What Fiscal Policy Is Effective at Zero Interest Rates?". NBER Macroeconomics Annual. 25: 59–60. doi:10.1086/657529. hdl:10419/60825. ISSN 0889-3365. S2CID 16071568.

- Krugman, Paul (13 December 2010). "Opinion – Block Those Economic Metaphors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Nayak, Pulin B. (2009). "Anatomy of the Financial Crisis: Between Keynes and Schumpeter". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (13): 160. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 40278675.

- Siegel, Jeremy J. (2002). Stocks for the Long Run: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns and Long-Term Investment Strategies, 3rd, New York: McGraw-Hill, 388. ISBN 978-0-07-137048-6

- "From the subprime to the terrigenous: Recession begins at home". Land Values Research Group. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

A downturn in the property market, especially in turnover (sales) of properties, is a leading indicator of recession, with a lead time of up to 9 quarters...

- Shiller, Robert J. (6 June 2009). "Why Home Prices May Keep Falling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- Sloan, Allan (11 December 2007). "Recession Predictions and Investment Decisions". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- "Economy puts Republicans at risk". BBC. 29 January 2008. Archived from the original on 2 February 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- The Bush Recession Archived 4 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Prepared by: Democratic staff, Senate Budget Committee, 31 July 2003

- Church, George J. (23 November 1981). "Ready for a Real Downer". Time. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008.

- Unemployment Rate Archived 12 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine p. 1. The Saylor Foundation. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Vaitilingam, Romesh (17 September 2009). "Recession Britain: New ESRC report on the impact of recession on people's jobs, businesses and daily lives". Economic and Social Research Council. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- Rampell, Catherine (11 January 2011). "More Workers Complain of Bias on the Job, a Trend Linked to Widespread Layoffs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ The Recession that Almost Was. Archived 12 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Kenneth Rogoff, International Monetary Fund, Financial Times, 5 April 2002

- "The world economy Bad, or worse". The Economist. 9 October 2008. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- Lall, Subir. International Monetary Fund, 9 April 2008. "IMF Predicts Slower World Growth Amid Serious Market Crisis" Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Global Economic Slump Challenges Policies Archived 9 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine IMF. January 2009.

- ^ "Global Recession Risk Grows as U.S. "Damage" Spreads. Jan 2008". Bloomberg L.P. 28 January 2008. Archived from the original on 21 March 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- "World Economic Outlook (WEO) April 2013: Statistical appendix – Table A1 – Summary of World Output" (PDF). IMF. 16 April 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ^ Davis, Bob (22 April 2009). "What's a Global Recession?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook – April 2009: Crisis and Recovery" (PDF). Box 1.1 (pp. 11–14). IMF. 24 April 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Australian Economic Indicators, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 27 February 1998, archived from the original on 16 October 2015, retrieved 11 August 2015

- "Reasons for 1990s Recession", The Age, Melbourne, 2 December 2006, archived from the original on 12 April 2014, retrieved 11 August 2015

- Janda, Michael (3 June 2020), Australian Recession, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, archived from the original on 3 June 2020, retrieved 3 June 2020

- BBC News, Eurozone recession deepened at end of 2012, published 14 February 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2022

- "UK officially in recession for first time in 11 years". The BBC. 12 August 2020. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Percent change from preceding period". U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Isidore, Chris (1 December 2008). "It's official: Recession since Dec. '07". CNN. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "US economy out of recession". BBC News – Business. 29 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- "Business Cycle Dating Committee Announcement July 19, 2021". NBER. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- "Business Cycle Dating Procedure: Frequently Asked Questions". NBER. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- Blake, Aaron (28 July 2022). "What two negative GDP quarters means for 'recession' — and our politics". The Washington Post.

- "Determination of the December 2007 Peak in Economic Activity" (PDF). NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee. 11 December 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Izzo, Phil (20 September 2010). "Recession Over in June 2009". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Economic Crisis: When will it End? IBISWorld Recession Briefing " Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dr. Richard J. Buczynski and Michael Bright, IBISWorld, January 2009

- Andrews, Edmund L. (7 March 2008). "Employment Falls for Second Month". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Recession unlikely if US economy gets through next two crucial months Archived 12 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Uchitelle, Louis; Andrews, Edmund L.; Labaton, Stephen (6 December 2008). "U.S. Loses 533,000 Jobs in Biggest Drop Since 1974". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- Uchitelle, Louis (9 January 2009). "U.S. lost 2.6 million jobs in 2008". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Unemployment rate in March 2009 Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine 6 April 2009. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- 2 million jobs lost so far in '09 Archived 11 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine CNN/Money. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "Employment Situation Summary". Bls.gov. 2 July 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- Goldman, David (9 January 2009). "Worst year for jobs since '45". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- Meyer, Brent (16 October 2008). "Real GDP First-Quarter 2008 Preliminary Estimate :: Brent Meyer :: Economic Trends :: 06.03.08 :: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland". Clevelandfed.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "Fragile economy improves but not out of woods yet". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on 7 July 2008.

- Why it's worse than you think Archived 1 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 16 June 2008, Newsweek.

- "Gross Domestic Product: Third quarter 2008". Bea.gov. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Chandra, Shobhana (30 October 2008). "U.S. Economy Contracts Most Since the 2001 Recession". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "Fourth quarter 2008 Survey of Professional Forecasters". Philadelphiafed.org. 17 November 2008. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "Text of the NBER's statement on the recession". USA Today. 1 December 2008. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Daniel Gross, The Recession Is... Over? Archived 19 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Newsweek, 14 July 2009.

- V.I. Keilis-Borok et al., "Pattern of Macroeconomic Indicators Preceding the End of an American Economic Recession". Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Journal of Pattern Recognition Research, JPRR Vol. 3 (1) 2008.

- "Business Cycle Dating Committee, National Bureau of Economic Research". nber.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

External links

Library resources aboutRecession

- Moore, Geoffrey H. (2002). "Recessions". In Henderson, David R. (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (1st ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty. OCLC 317650570, 50016270, 163149563

- Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions The National Bureau Of Economic Research