This is the current revision of this page, as edited by Renamed user e49d72558f52759b30121a878bac3a27 (talk | contribs) at 23:31, 30 June 2024 (#article-section-source-editor). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this version.

Revision as of 23:31, 30 June 2024 by Renamed user e49d72558f52759b30121a878bac3a27 (talk | contribs) (#article-section-source-editor)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Medical condition where the tendon at the back of the ankle breaks Medical condition| Achilles tendon rupture | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Achilles tendon tear, Achilles rupture |

| |

| The achilles tendon | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Pain in the heel |

| Usual onset | Sudden |

| Causes | Forced plantar flexion of the foot, direct trauma, long-standing tendonitis |

| Risk factors | Fluoroquinolones, significant change in exercise, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, corticosteroids |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and examination, supported by medical imaging |

| Differential diagnosis | Achilles tendinitis, ankle sprain, avulsion fracture of the calcaneus |

| Treatment | Casting or surgery |

| Frequency | 1 per 10,000 people per year |

Achilles tendon rupture is when the Achilles tendon, at the back of the ankle, breaks. Symptoms include the sudden onset of sharp pain in the heel. A snapping sound may be heard as the tendon breaks and walking becomes difficult.

Rupture typically occurs as a result of a sudden bending up of the foot when the calf muscle is engaged, direct trauma, or long-standing tendonitis. Other risk factors include the use of fluoroquinolones, a significant change in exercise, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, or corticosteroid use. Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and examination and supported by medical imaging.

Prevention may include stretching before activity and gradual progression of exercise intensity. Treatment may consist of surgical repair or conservative management. Quick return to weight bearing (within 4 weeks) appears acceptable and is often recommended. While surgery traditionally results in a small decrease in the risk of re-rupture, the risk of other complications is greater. Non-surgical treatment is an alternative as there is supporting evidence that rerupture rates and satisfactory outcomes are comparable to surgery. If appropriate treatment does not occur within 4 weeks of the injury outcomes are not as good.

Achilles tendon rupture occurs in about 1 per 10,000 people per year. Males are more commonly affected than females. People in their 30s to 50s are most commonly affected.

Signs and symptoms

The main symptom of an Achilles tendon rupture is the sudden onset of sharp pain in the heel. Additionally, a snap or "pop" may be heard as the tendon breaks. Some people describe the pain as a hit or kick behind the lower leg. There is difficulty walking immediately. It may be difficult to push off or stand on the toes of the injured leg. Swelling may be present around the heel.

Causes

The Achilles tendon is most often injured by sudden downward or upward movement of the foot, or by forced upward flexion of the foot outside its normal range of motion. Other ways the Achilles tendon can be torn involve sudden direct trauma or damage to the tendon, or sudden use of the Achilles after prolonged periods of inactivity, such as bed rest or leg injury. Some other common tears can happen from intense sports overuse. Twisting or jerking motions can also contribute to injury. Some antibiotics, such as levofloxacin, may increase the risk of tendon injury or rupture. These antibiotics are known as fluoroquinolones. As of 2016 the mechanism through which fluoroquinolones cause this was unclear.

Many people may develop an Achilles rupture or tear, such as recreational athletes, older people, or those with a previous Achilles tendon injury. Tendon injections, quinolone use, and extreme changes in exercise intensity can contribute. Most cases of Achilles tendon rupture are traumatic sports injuries. The average age of patients is 29–40 years with a male-to-female ratio of nearly 20:1. Yet, recent studies have shown that Achilles tendon ruptures are rising in all ages up to 60 years of age. It has been theorized that this is due to the popularity of remaining active with older age. Additionally, even the occasional weekend exercise activity for "weekend warriors" may put one at risk. The risk continues to be higher in people who are older than 60, and also taking corticosteroids, or have kidney disease. Risk also increases with dose amount and for longer periods of time.

Anatomy

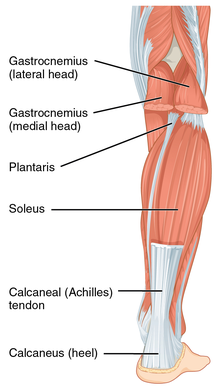

The Achilles tendon is the strongest and thickest tendon in the body. It connects the calf muscles to the heel bone of the foot. The calf muscles are the gastrocnemius, soleus and the heel bone is called the calcaneus. It is approximately 15 centimeters (5.9 inches) long and begins near the middle part of the calf. Contraction of the calf muscles flexes the foot down. This is important in activities such as walking, jumping, and running. The Achilles tendon receives its blood supply from its muscular and tendon junction. Its nerve supply is from the sural nerve and to a lesser degree from the tibial nerve.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and history of the event. People describe it like being kicked or shot behind the ankle. During physical examination, a gap may be felt above the heel unless swelling is present. A common physical exam test the doctor or provider may perform is the Simmonds' test (aka Thompson test). To perform the test, have the person lay on their stomach, face down, and with their feet hanging from the exam table. The test is positive if squeezing the calf muscles of the affected side results in no movement (no passive plantarflexion) of the foot. The test is negative with an intact Achilles tendon and squeezing the calf muscle results in the foot flexing down. Walking is usually impaired, as the person will be unable to step off the ground using the injured leg. The person will also be unable to stand up on the toes of that leg, and pointing the foot downward (plantarflexion) is impaired. Pain may be severe, and swelling around the ankle is common.

Although a tear may be diagnosed by history and physical exam alone, an ultrasound scan is sometimes required to clarify or confirm the diagnosis. Once diagnosis is made, ultrasound imaging is an effective way to monitor the healing progress of the tendon over time. An ultrasound is recommended over MRI and MRI is generally not needed. Both MRI and ultrasound are effective tools and have their strengths and limitations. However, when it comes to an Achilles tendon tear, an ultrasound is usually recommended first because of convenience, quick availability, and cost.

Imaging

Ultrasonography can be used to determine the tendon thickness, character, and presence of a tear. It works by sending harmless high frequencies of sound waves through the body. Some of these sound waves reflect back off the spaces between fluid and soft tissue or bone. These reflected images are analyzed and created into an image. These images capture in real time and are helpful in detecting movement of the tendon and visualizing injuries or tears. This device makes it possible to identify injuries and observe healing over time. Ultrasound is inexpensive and involves no harmful radiation. It is operator-dependent and so requires a level of skill and practice for it to be used effectively.

MRI can be used to distinguish incomplete ruptures from degeneration of the Achilles tendon. MRI can also distinguish between paratenonitis, tendinosis, and bursitis. This technique uses a strong uniform magnetic field to align millions of protons running through the body. These protons are then bombarded with radio waves that knock some of them out of alignment. When these protons return they emit their own unique radio waves that is analyzed by a computer in 3D to create a sharp cross sectional image of the area. MRI provides excellent soft tissue imaging making it easier for technicians to spot tears or other injuries.

Radiography can also be used to indirectly identify Achilles tendon tears. Radiography uses X-rays to analyze the point of injury. This is not very effective at identifying soft tissue injuries. X-rays are created when high energy electrons hit a metal source. X-ray images are acquired by utilizing the different densities of the bone or tissue. When these rays pass through tissue they are captured on film. X-rays are generally best for dense objects such as bone while soft tissue is shown poorly. Radiography is not the best for assessing an Achilles tendon injury. It is more useful for ruling out other injuries such as heal bone fractures.

Differential diagnosis

Some conditions to consider when diagnosing an Achilles tendon tear are Achilles tendinitis, ankle sprain, and avulsion fracture of the calcaneus.

Treatment

Treatment options include surgery and non-surgical rehabilitation. Surgery has shown a lower risk of re-rupture. However, it has a higher rate of short-term problems. Surgery complications include leg clots, nerve damage, infection, and clots in the lungs. The most common problem after non-surgical treatment is leg clots. The main problem after surgery is infection. Certain rehabilitation techniques have shown similar re-rupture rates to surgery. In centers without early range of motion rehabilitation available, surgery is preferred to decrease re-rupture rates.

Surgery

There are at least four different types of surgeries; open surgery, percutaneous surgery, ultrasound-guided surgery, and WALANT surgery.

During an open surgery, an incision is made in the back of the leg and the Achilles tendon is stitched together. In complete ruptures, the tendon of another muscle is used and wrapped around the Achilles tendon. Commonly, the tendon of the plantaris is used and this wrapping increases the strength of the repaired tendon. If the quality of tissues is poor, such as from a neglected injury, a reinforcement mesh is an option. These meshes can be of collagen, Artelon or other degradable material. In the case of both poor tissue and significant loss of the Achilles tendon, the flexor hallucis longus tendon can be used. The flexor hallucis longus tendon of the big toe is transferred with free tissue (skin flap) in a process described as a one-stage repair.

In percutaneous surgery, several small incisions are made, rather than one large incision. The tendon is sewn back together through the incision(s). Surgery is often delayed for about a week after the rupture to let the swelling go down. For sedentary patients and those who have vascular diseases or risks for poor healing, percutaneous surgical repair may be the better surgical option. Surgical care is evolving, with minimally invasive and percutaneous surgical techniques. These developments hope to lessen the risk of wound complications and infections found with open surgery. These techniques are more challenging than traditional open surgery, with a learning curve for surgeons, and are not yet widely used.

Rehabilitation

Non-surgical treatment used to be long and a tedious process. It involved a series of casts, and took longer to complete than surgical treatment. Recently, both surgical and non-surgical rehabilitation protocols have become quicker and more successful. Before, patients who underwent surgery would wear a cast for approximately 4 to 8 weeks. After surgery, they were only allowed to gently move the ankle once out of the cast. Recent studies have shown that is not the best method. Patients that are allowed to gently move and stretch the ankle immediately after surgery, have faster and more successful recoveries. They will wear removable boots to ensure their safety with these exercises. For surgical and non-surgical patients, they will still generally limit non-weightbearing (NWB) activity to two weeks. This is done using modern removable boots, either fixed or hinged, rather than casts. Physiotherapy is often begun as early as two weeks regardless of surgical or non-surgical treatment. This includes weightbearing and range of motion exercises. This is followed by progressive strengthening and general conditioning of the muscle and tendon.

There are three things to consider with Achilles rupture rehabilitation. These are range of motion, functional strength, and sometimes orthotic support. Range of motion is important because it takes into mind the tightness of the repaired tendon. When beginning rehabilitation, a person should perform light stretches. Over time, the goal should be to increase the intensity of that stretch. Stretching the tendon is important because it stimulates connective tissue repair. This can be done while performing the "runner's stretch". The runner's stretch involves putting the toes a few inches up a wall while the heel is on the ground. Doing stretches to gain functional strength is also important because it improves healing in the tendon. This will in turn lead to a quicker return to activities. These stretches should continue to increase in intensity over time. Over time the goal is to include some weight bearing, to reorient and strengthen the collagen fibers in the injured ankle. A popular stretch used for this phase of rehabilitation is the toe raise on an elevated surface. The patient is to push up onto the toes and lower themselves as far down as possible and repeat several times. The other part of the rehab process is orthotic support. This doesn't have anything to do with stretching or strengthening the tendon, rather it is in place to keep the patient comfortable. These are custom-made inserts that fit into the patient's shoe. They help with proper pronation of the foot, which is when the ankle leans toward the middle of the body.

In summary, the steps of rehabilitating a ruptured Achilles tendon begin with range of motion type stretching. Studies have shown that the earlier movement is started, the better. This will allow the ankle to get used to moving again and get ready for weight-bearing activities. This is followed by functional strength. This is where weight-bearing should begin to strengthen the tendon. The intensity should gradually increase over time. The end goal is to get the person to resume their normal and athletic activities.

Epidemiology

Of all the large tendon ruptures, 1 in 5 will be an Achilles tendon rupture. An Achilles tendon rupture is estimated to occur in a little over 1 per 10,000 people per year. Males are also over 2 times more likely to develop an Achilles tendon rupture as opposed to women. Achilles tendon rupture tends to occur most frequently between the ages of 25-40 and over 60 years of age. Sports and high-impact activity is the most common cause of rupture in younger people, whereas sudden rupture from chronic tendon damage is more common in older people. The rate of return to sports in the months or years following the rupture (whether operated on or not, partial or total) is 70 to 80%.

References

- ^ "Achilles Tendon Tears". MSD Manual Professional Edition. August 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Ochen Y, Beks RB, van Heijl M, Hietbrink F, Leenen LP, van der Velde D, et al. (January 2019). "Operative treatment versus nonoperative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 364: k5120. doi:10.1136/bmj.k5120. PMC 6322065. PMID 30617123.

- ^ Hubbard MJ, Hildebrand BA, Battafarano MM, Battafarano DF (June 2018). "Common Soft Tissue Musculoskeletal Pain Disorders". Primary Care. 45 (2): 289–303. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.006. PMID 29759125. S2CID 46886582.

- ^ Shamrock AG, Varacallo M (January 2018). "Achilles Tendon, Rupture". StatPearls. PMID 28613594.

- ^ Ferri FF (2015). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2016 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 19. ISBN 9780323378222.

- ^ El-Akkawi AI, Joanroy R, Barfod KW, Kallemose T, Kristensen SS, Viberg B (March 2018). "Effect of Early Versus Late Weightbearing in Conservatively Treated Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: A Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 57 (2): 346–352. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2017.06.006. PMID 28974345. S2CID 3506883.

- van der Eng DM, Schepers T, Goslings JC, Schep NW (2012). "Rerupture rate after early weightbearing in operative versus conservative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures: a meta-analysis". The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 52 (5): 622–628. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2013.03.027. PMID 23659914.

- Maffulli N, Ajis A (June 2008). "Management of chronic ruptures of the Achilles tendon". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 90 (6): 1348–1360. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.01241. PMID 18519331.

- Shamrock AG, Varacallo M (January 2018). "Achilles Tendon, Rupture". StatPearls. PMID 28613594

- ^ Bidell MR, Lodise TP (June 2016). "Fluoroquinolone-Associated Tendinopathy: Does Levofloxacin Pose the Greatest Risk?". Pharmacotherapy. 36 (6): 679–693. doi:10.1002/phar.1761. PMID 27138564. S2CID 206359106.

- ^ Dams OC, Reininga IH, Gielen JL, van den Akker-Scheek I, Zwerver J (November 2017). "Imaging modalities in the diagnosis and monitoring of Achilles tendon ruptures: A systematic review" (PDF). Injury. 48 (11): 2383–2399. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2017.09.013. PMID 28943056. S2CID 25815282.

- ^ Doral MN, Alam M, Bozkurt M, Turhan E, Atay OA, Dönmez G, Maffulli N (May 2010). "Functional anatomy of the Achilles tendon". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 18 (5): 638–643. doi:10.1007/s00167-010-1083-7. PMID 20182867. S2CID 24159374.

- Cuttica DJ, Hyer CF, Berlet GC (January 2015). "Intraoperative value of the thompson test". The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 54 (1): 99–101. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2014.09.014. PMID 25441265.

- ^ Achilles Tendon Injuries~differential at eMedicine

- ^ Aminlari A, Stone J, McKee R, Subramony R, Nadolski A, Tolia V, Hayden SR (November 2021). "Diagnosing Achilles Tendon Rupture with Ultrasound in Patients Treated Surgically: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 61 (5): 558–567. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.09.008. PMID 34801318. S2CID 244381264.

- Grover VP, Tognarelli JM, Crossey MM, Cox IJ, Taylor-Robinson SD, McPhail MJ (September 2015). "Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Principles and Techniques: Lessons for Clinicians". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 5 (3): 246–255. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2015.08.001. PMC 4632105. PMID 26628842.

- ^ "Achilles tendon rupture". Mayo Clinic. August 20, 2014.

- ^ Nazerali RS, Hakimi M, Giza E, Sahar DE. Single-stage reconstruction of achilles tendon rupture with flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer and simultaneous free radial fasciocutaneous forearm flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2013 Apr;70(4):416-8. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182853d6c. PMID 23486135.

- "My Achilles tendon rupture | Fisiodue Fisioterapia Palma de Mallorca". Fisiodue (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ Zellers JA, Christensen M, Kjær IL, Rathleff MS, Silbernagel KG (November 2019). "Defining Components of Early Functional Rehabilitation for Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: A Systematic Review". Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 7 (11): 2325967119884071. doi:10.1177/2325967119884071. PMC 6878623. PMID 31803789.

- ^ Cluett J (April 29, 2007). "Achilles Tendon Rupture: What is an Achilles Tendon Rupture". Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- ^ Christensen KD (July 20, 2003). "Rehab of the Achilles Tendon". Archived from the original on November 29, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Huang, Jiazhang; Wang, Chen; Ma, Xin; Wang, Xu; Zhang, Chao; Chen, Li (April 2015). "Rehabilitation Regimen After Surgical Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 43 (4): 1008–1016. doi:10.1177/0363546514531014. ISSN 0363-5465. PMID 24793572. S2CID 206528867.

- Scott, Lisa A.; Munteanu, Shannon E.; Menz, Hylton B. (January 2015). "Effectiveness of Orthotic Devices in the Treatment of Achilles Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review". Sports Medicine. 45 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0237-z. ISSN 0112-1642. PMID 25108348. S2CID 25491960.

- Park SH, Lee HS, Young KW, Seo SG. Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture. Clin Orthop Surg. 2020;12(1):1-8. doi:10.4055/cios.2020.12.1.1

- Tarantino, Domiziano; Palermi, Stefano; Sirico, Felice; Corrado, Bruno (2020-12-17). "Achilles Tendon Rupture: Mechanisms of Injury, Principles of Rehabilitation and Return to Play". Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 5 (4): 95. doi:10.3390/jfmk5040095. ISSN 2411-5142. PMC 7804867. PMID 33467310.

External links

- [REDACTED] Media related to Achilles tendon rupture at Wikimedia Commons

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Soft tissue disorders | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsular joint |

| ||||||||||

| Noncapsular joint |

| ||||||||||

| Nonjoint |

| ||||||||||

| Dislocations/subluxations, sprains and strains | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joints and ligaments |

| ||||||||||||

| Muscles and tendons |

| ||||||||||||