This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Morogris (talk | contribs) at 21:36, 2 October 2024 (→Filming: No mention of the equipment rentals / budget costs as to why they filmed in the heat. I checked the two sources for this and there is no mention of it.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:36, 2 October 2024 by Morogris (talk | contribs) (→Filming: No mention of the equipment rentals / budget costs as to why they filmed in the heat. I checked the two sources for this and there is no mention of it.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) 1974 film by Tobe Hooper This article is about the 1974 film. For subsequent films, see The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (franchise).

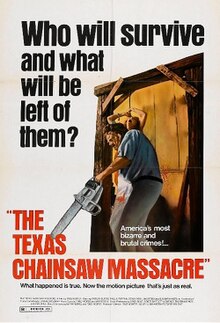

| The Texas Chain Saw Massacre | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tobe Hooper |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Tobe Hooper |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Daniel Pearl |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

| Production company | Vortex Inc. |

| Distributed by | Bryanston Distributing Company |

| Release dates |

|

| Running time | 83 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $80,000–140,000 |

| Box office | $30.9 million |

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a 1974 American independent horror film produced, co-composed, and directed by Tobe Hooper, who co-wrote it with Kim Henkel. The film stars Marilyn Burns, Paul A. Partain, Edwin Neal, Jim Siedow, and Gunnar Hansen. The plot follows a group of friends who fall victim to a family of cannibals while on their way to visit an old homestead. The film was marketed as being based on true events to attract a wider audience and to act as a subtle commentary on the era's political climate. Although the character of Leatherface and minor story details were inspired by the crimes of murderer Ed Gein, its plot is largely fictional.

Hooper produced the film for less than $140,000 ($700,000 adjusted for inflation) and used a cast of relatively unknown actors drawn mainly from central Texas, where the film was shot. The limited budget forced Hooper to film for long hours seven days a week, so that he could finish as quickly as possible and reduce equipment rental costs. Due to the film's violent content, Hooper struggled to find a distributor, but it was eventually acquired by the Bryanston Distributing Company. Hooper limited the quantity of onscreen gore in hopes of securing a PG rating, but the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) rated it R. The film faced similar difficulties internationally, being banned in several countries, and numerous theaters stopped showing the film in response to complaints about its violence.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was released in the United States on October 11, 1974. While the film initially received mixed reception from critics, it was highly profitable, grossing over $30 million at the domestic box office, equivalent with roughly over $150.8 million as of 2019, selling over 16.5 million tickets in 1974. It has since gained a reputation as one of the best and most influential horror films. It is credited with originating several elements common in the slasher genre, including the use of power tools as murder weapons, the characterization of the killer as a large, hulking, masked figure, and the killing of victims. It led to a franchise that continued the story of Leatherface and his family through sequels, prequels, a remake, comic books, and video games.

Plot

In the early hours of August 18, 1973, a grave robber steals several remains from a cemetery near Newt, Muerto County, Texas. The robber ties a rotting corpse and other body parts onto a monument, creating a grisly display that is discovered by a local resident as the sun rises.

Driving in a van, five teenagers take a road trip through the area: Sally Hardesty, Jerry, Pam, Kirk, and Sally's paraplegic brother Franklin. They stop at the cemetery to check on the grave of Sally and Franklin's grandfather, which appears undisturbed. As the group drives past a slaughterhouse, Franklin recounts the Hardesty family's history with animal slaughter. They soon pick up a hitchhiker, who talks about his family who worked at the old slaughterhouse. He borrows Franklin's pocket knife and cuts himself, then takes a single Polaroid picture of the group, for which he demands money. When they refuse to pay, he burns the photo and attacks Franklin with a straight razor. The group forces him out of the van, where he smears blood on the side as they drive off. Low on gas, the group stops at a station whose proprietor says that no fuel is available. The group explores a nearby abandoned house, owned by the Hardesty family.

Kirk and Pam leave the others behind, planning to visit a nearby swimming hole mentioned by Franklin. On their way there, they discover another house, surrounded by run-down cars, and run by gas-powered generators. Hoping to barter for gas, Kirk enters the house through the unlocked door, while Pam waits outside. As he searches the house, a large man wearing a mask made of skin appears and murders Kirk with a hammer. When Pam enters the house, she stumbles into a room strewn with decaying remains and furniture made from human and animal bones. She attempts to flee but is caught by the man and impaled on a meat hook. The man then starts up a chainsaw, dismembering Kirk as Pam watches. In the evening, Jerry searches for Pam and Kirk. When he enters the other house, he finds Pam's nearly-dead, spasming body in a chest freezer and is killed by the masked man.

With darkness falling, Sally and Franklin set out to find their friends. En route, the masked man ambushes them, killing Franklin with the chainsaw. The man chases Sally into the house, where she finds a very old, seemingly dead man and a woman's rotting corpse. She escapes from the man by jumping through a second-floor window, and she flees to the gas station. With the man in pursuit, Sally arrives at the gas station when he seems to disappear. The station's proprietor comforts Sally with the offer of help, after which he beats and subdues her, loading her into his pickup truck. The proprietor drives to the other house, and the hitchhiker appears. The proprietor scolds him for his actions at the cemetery, identifying the hitchhiker as the grave robber. As they enter the house, the masked man reappears, dressed in women's clothing. The proprietor identifies the masked man and the hitchhiker as brothers, and the hitchhiker refers to the masked man as "Leatherface". The two brothers bring the old man—"Grandpa"—down the stairs and cut Sally's finger so that Grandpa can suck her blood, Sally then faints from the ordeal.

The next morning, Sally regains consciousness. The men taunt her and bicker with each other, resolving to kill her with a hammer. They try to include Grandpa in the activity, but Grandpa is too weak. Sally breaks free and runs onto a road in front of the house, pursued by the brothers. An oncoming truck accidentally runs over the hitchhiker, killing him. The truck driver attacks Leatherface with a large wrench, causing him to fall and injure his leg with the chainsaw. Sally, covered in blood, flags down a passing pickup truck and climbs into the bed, narrowly escaping Leatherface. As the pickup drives away, Sally laughs hysterically while an enraged Leatherface swings his chainsaw in the road as the sun rises.

Cast

- Marilyn Burns as Sally Hardesty

- Allen Danziger as Jerry

- Paul A. Partain as Franklin Hardesty

- William Vail as Kirk

- Teri McMinn as Pam

- Edwin Neal as Hitchhiker

- Jim Siedow as Old Man

- Gunnar Hansen as Leatherface

- John Dugan as Grandfather

- Robert Courtin as Window Washer

- William Creamer as Bearded Man

- John Henry Faulk as Storyteller

- Jerry Green as Cowboy

- Ed Guinn as Cattle Truck Driver

- Joe Bill Hogan as Drunk

- Perry Lorenz as Pick Up Driver

- John Larroquette as Narrator

Production

Development

The concept for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre arose in the early 1970s while Tobe Hooper was working as an assistant film director at the University of Texas at Austin and as a documentary cameraman. He had already developed a story involving the elements of isolation, the woods, and darkness. He credited the graphic coverage of violence by San Antonio news outlets as one inspiration for the film and based elements of the plot on murderer Ed Gein, who committed his crimes in 1950s Wisconsin; Gein inspired other horror films such as Psycho (1960) and The Silence of the Lambs (1991). During development, Hooper used the working titles of Headcheese and Leatherface.

— Kim HenkelI definitely studied Gein ... but I also noticed a murder case in Houston at the time, a serial murderer you probably remember named Elmer Wayne Henley. He was a young man who recruited victims for an older homosexual man. I saw some news report where Elmer Wayne ... said, "I did these crimes, and I'm gonna stand up and take it like a man." Well, that struck me as interesting, that he had this conventional morality at that point. He wanted it known that, now that he was caught, he would do the right thing. So this kind of moral schizophrenia is something I tried to build into the characters.

Hooper has cited changes in the cultural and political landscape as central influences on the film. His intentional misinformation, that the "film you are about to see is true", was a response to being "lied to by the government about things that were going on all over the world", including Watergate, the 1973 oil crisis, and "the massacres and atrocities in the Vietnam War". The "lack of sentimentality and the brutality of things" that Hooper noticed while watching the local news, whose graphic coverage was epitomized by "showing brains spilled all over the road", led to his belief that "man was the real monster here, just wearing a different face, so I put a literal mask on the monster in my film". The idea of using a chainsaw as the murder weapon came to Hooper while he was in the hardware section of a busy store, contemplating how to speed his way through the crowd.

Hooper and Kim Henkel cowrote the screenplay and formed Vortex, Inc. with Henkel as president and Hooper as vice president. They asked Bill Parsley, a friend of Hooper, to provide funding. Parsley formed a company named MAB, Inc. through which he invested $60,000 in the production. In return, MAB owned 50% of the film and its profits. Production manager Ron Bozman told most of the cast and crew that he would have to defer part of their salaries until after it was sold to a distributor. Vortex made the idea more attractive by awarding them a share of its potential profits, ranging from 0.25 to 6%, similar to mortgage points. The cast and crew were not informed that Vortex owned only 50%, which meant their points were worth half of the assumed value.

Casting

Many of the cast members at the time were relatively unknown actors—Texans who had played roles in commercials, television, and stage shows, as well as performers whom Hooper knew personally, such as Allen Danziger and Jim Siedow. Involvement in the film propelled some of them into the motion picture industry. The lead role of Sally was given to Marilyn Burns, who had appeared previously on stage and served on the film commission board at UT Austin while studying there. Teri McMinn was a student who worked with local theater companies, including the Dallas Theater Center. Henkel called McMinn to come in for a reading after he spotted her picture in the Austin American-Statesman. For her last call-back he requested that she wear short shorts, which proved to be the most comfortable of all the cast members' costumes.

Icelandic-American actor Gunnar Hansen was selected for the role of Leatherface. He regarded Leatherface as having an intellectual disability and having never learned to speak properly. To research his character in preparation for his role, Hansen visited a special needs school and watched how the students moved and spoke. John Larroquette performed the narration in the opening credits, for which he was paid in marijuana.

Filming

The primary filming location was an early 1900s farmhouse located on Quick Hill Road near Round Rock, Texas, where the La Frontera development is now located. The crew filmed seven days a week, up to 16 hours a day. The environment was hot and the cast and crew found conditions tough; temperatures peaked at 110°F (43 °C) on July 26. Hansen later recalled, "It was 95, 100 degrees every day during filming. They wouldn't wash my costume because they were worried that the laundry might lose it, or that it would change color. They didn't have enough money for a second costume. So I wore that 12 to 16 hours a day, seven days a week, for a month."

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was mainly shot using an Eclair NPR 16mm camera with fine-grain, low-speed Ektachrome Commercial film that required considerably more light than modern digital cameras and even most filmstocks of the day. This allowed more mobility and cost savings over shooting on the standard theatrical 35mm format of the time, without significant sacrifices to image quality. Most of the filming took place in the farmhouse, which was filled with furniture constructed from animal bones and a latex material used as upholstery to give the appearance of human skin. The house was not cooled, and there was little ventilation. The crew covered its walls with drops of animal blood obtained from a local slaughterhouse. Art director Robert A. Burns drove around the countryside and collected the remains of cattle and other animals in various stages of decomposition, with which he littered the floors of the house.

The special effects were simple and limited by the budget. The on-screen blood was real in some cases, such as the scene in which Leatherface feeds "Grandpa". The crew had difficulty getting the stage blood to come out of its tube, so instead Burns's index finger was cut with a razor. Burns's costume was so drenched with stage blood that it was "virtually solid" by the last day of shooting. The scene in which Leatherface dismembers Kirk with a chainsaw worried actor William Vail (Kirk). After telling Vail to stay still lest he really be killed, Hansen brought the running chainsaw to within 3 inches (8 cm) of Vail's face. A real hammer was used for the climactic scene at the end, with some takes also featuring a mock-up. However, the actor playing Grandpa was aiming for the floor rather than his victim's head. Still, the shoot was quite dangerous, with Hooper noting at the wrap party that all cast members had obtained some level of injury. He stated that "everyone hated me by the end of the production" and that "it just took years for them to kind of cool off."

Post-production

The production exceeded its original $60,000 (about $288,000 adjusted for inflation) budget during editing. Sources differ on the film's final cost, offering figures between $93,000 (about $447,000 inflation-adjusted) and $300,000 (about $1,400,000 inflation-adjusted). A film production group, Pie in the Sky, partially led by future President of the Texas State Bar Joe K. Longley provided $23,532 (about $113,000 inflation-adjusted) in exchange for 19% of Vortex. This left Henkel, Hooper and the rest of the cast and crew with a 40.5% stake. Warren Skaaren, then head of the Texas Film Commission, helped secure the distribution deal with Bryanston Distributing Company. David Foster, who would later produce the 1982 horror film The Thing, arranged for a private screening for some of Bryanston's West Coast executives, and received 1.5% of Vortex's profits and a deferred fee of $500 (about $2,400 inflation-adjusted).

On August 28, 1974, Louis Peraino of Bryanston agreed to distribute the film worldwide, from which Bozman and Skaaren would receive $225,000 (about $1,100,000 inflation-adjusted) and 35% of the profits. Years later Bozman stated, "We made a deal with the devil, , and I guess that, in a way, we got what we deserved." They signed the contract with Bryanston and, after the investors recouped their money (with interest),—and after Skaaren, the lawyers, and the accountants were paid—only $8,100 (about $38,900 inflation-adjusted) was left to be divided among the 20 cast and crew members. Eventually the producers sued Bryanston for failing to pay them their full percentage of the box office profits. A court judgment instructed Bryanston to pay the filmmakers $500,000 (about $2,400,000 inflation-adjusted), but by then the company had declared bankruptcy. In 1983, New Line Cinema acquired the distribution rights from Bryanston and gave the producers a larger share of the profits.

Release

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre premiered in Austin, Texas, on October 1, 1974, almost a year after filming concluded. It screened nationally in the United States as a Saturday afternoon matinée and its false marketing as a "true story" helped it attract a broad audience. For eight years after 1976, it was annually reissued to first-run theaters, promoted by full-page ads. The film eventually grossed more than $30 million in the United States and Canada ($14.4 million in rentals), making it the 12th highest-grossing film initially released in 1974, despite its minuscule budget. Among independent films, it was overtaken in 1978 by John Carpenter's Halloween, which grossed $47 million.

— The opening crawl falsely suggests that the film is based on true events, a conceit that contributed to its success.The film which you are about to see is an account of the tragedy which befell a group of five youths, in particular Sally Hardesty and her invalid brother, Franklin.

Hooper reportedly hoped that the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) would give the complete, uncut release print a "PG" rating due to its minimal amount of visible gore. Instead, it was originally rated "X". After several minutes were cut, it was resubmitted to the MPAA and received an "R" rating. A distributor apparently restored the offending material, and at least one theater presented the full version under an "R". In San Francisco, cinema-goers walked out of theaters in disgust and in February 1976, two theaters in Ottawa, Canada, were advised by local police to withdraw the film lest they face morality charges.

After its initial British release, including a one-year theatrical run in London, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was initially banned on the advice of British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) Secretary Stephen Murphy, and subsequently by his successor, James Ferman. While the British ban was in force the word "chainsaw" itself was barred from movie titles, forcing imitators to rename their films. In 1998, despite the BBFC ban, Camden London Borough Council granted the film a license. The following year the BBFC passed The Texas Chain Saw Massacre uncut for release with an 18 certificate, and it was broadcast a year later on Channel 4.

When the 83-minute version of the film was submitted to the Australian Classification Board by distributor Seven Keys in June 1975, the Board denied the film a classification, and similarly refused classification of a 77-minute print in December that year. In 1981, the 83-minute version submitted by Greater Union Film Distributors was again refused registration. It was later submitted by Filmways Australasian Distributors and approved for an "R" rating in 1984. It was banned for periods in many other countries, including Brazil, Chile, Finland, France, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Singapore, Sweden and West Germany. In Sweden, it would also symbolize a video nasty, a discussed topic at the time.

The film was released in 2021 in Australia and 2024 in Russia, grossing $36,879 at the international box office.

Reception

Critical response

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre received a mixed reaction upon its initial release. Linda Gross of the Los Angeles Times called it "despicable" and described Henkel and Hooper as more concerned with creating a realistic atmosphere than with its "plastic script". Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times said it was "as violent and gruesome and blood-soaked as the title promises", yet praised its acting and technical execution. Donald B. Berrigan of The Cincinnati Enquirer praised the lead performance of Burns: "Marilyn Burns, as Sally, deserves a special Academy Award for one of the most sustained and believable acting achievements in movie history." Patrick Taggart of the Austin American-Statesman hailed it as the most important horror film since George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead (1968). Variety found the picture to be well-made, despite what it called the "heavy doses of gore". John McCarty of Cinefantastique stated that the house featured in the film made the Bates motel "look positively pleasant by comparison". Revisiting the film in his 1976 article "Fashions in Pornography" for Harper's Magazine, Stephen Koch found its sadistic violence to be extreme and unimaginative.

— Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-TimesHorror and exploitation films almost always turn a profit if they're brought in at the right price. So they provide a good starting place for ambitious would-be filmmakers who can't get more conventional projects off the ground. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre belongs in a select company (with Night of the Living Dead and Last House on the Left) of films that are really a lot better than the genre requires. Not, however, that you'd necessarily enjoy seeing it.

Critics later frequently praised both the film's aesthetic quality and its power. Observing that it managed to be "horrifying without being a bloodbath (you'll see more gore in a Steven Seagal film)", Bruce Westbrook of the Houston Chronicle called it "a backwoods masterpiece of fear and loathing". TV Guide thought it was "intelligent" in its "bloodless depiction of violence", while Anton Bitel felt the fact that it was banned in the United Kingdom was a tribute to its artistry. He pointed out how the quiet sense of foreboding at the beginning of the film grows, until the viewer experiences "a punishing assault on the senses". In Hick Flicks: The Rise and Fall of Redneck Cinema, Scott Von Doviak commended its effective use of daylight shots, unusual among horror films, such as the sight of a corpse draped over a tombstone in the opening sequence. Mike Emery of The Austin Chronicle praised the film's "subtle touches"—such as radio broadcasts heard in the background describing grisly murders around Texas—and said that what made it so dreadful was that it never strayed too far from potential reality.

It has often been described as one of the scariest films of all time. Rex Reed called it the most terrifying film he had ever seen. Empire described it as "the most purely horrifying horror movie ever made" and called it "never less than totally committed to scaring you witless". Reminiscing about his first viewing of the film, horror director Wes Craven recalled wondering "what kind of Mansonite crazoid" could have created such a thing. It is a work of "cataclysmic terror", in the words of horror novelist Stephen King, who declared, "I would happily testify to its redeeming social merit in any court in the country." Critic Robin Wood found it one of the few horror films to possess "the authentic quality of nightmare". Quentin Tarantino called it "one of the few perfect movies ever made."

Based on 82 reviews published since 2000, the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes reports that 83% of critics gave it a positive review, with an average score of 8.10/10. The site's critical consensus states, "Thanks to a smart script and documentary-style camerawork, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre achieves start-to-finish suspense, making it a classic in low-budget exploitation cinema."

Cultural impact

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is widely considered one of the greatest—and most controversial—horror films of all time and a major influence on the genre. In 1999, Richard Zoglin of Time commented that it had "set a new standard for slasher films". The Times listed it as one of the 50 most controversial films of all time. Tony Magistrale believes the film paved the way for horror to be used as a vehicle for social commentary. Describing it as "cheap, grubby and out of control", Mark Olsen of the Los Angeles Times declared that it "both defines and entirely supersedes the very notion of the exploitation picture". In his book Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film, David Hogan called it "the most affecting gore thriller of all and, in a broader view, among the most effective horror films ever made ... the driving force of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is something far more horrible than aberrant sexuality: total insanity." According to Bill Nichols, it "achieves the force of authentic art, profoundly disturbing, intensely personal, yet at the same time far more than personal". Leonard Wolf praised the film as "an exquisite work of art" and compared it to a Greek tragedy, noting the lack of onscreen violence.

Leatherface has gained a reputation as a significant character in the horror genre, responsible for establishing the use of conventional tools as murder weapons and the image of a large, silent killer devoid of personality. Christopher Null of Filmcritic.com said, "In our collective consciousness, Leatherface and his chainsaw have become as iconic as Freddy and his razors or Jason and his hockey mask." Don Sumner called The Texas Chain Saw Massacre a classic that not only introduced a new villain to the horror pantheon but also influenced an entire generation of filmmakers. According to Rebecca Ascher-Walsh of Entertainment Weekly, it laid the foundations for the Halloween, Evil Dead, and Blair Witch horror franchises. Wes Craven crafted his 1977 film The Hills Have Eyes as an homage to Massacre, while Ridley Scott cited Hooper's film as an inspiration for his 1979 film Alien. French director Alexandre Aja credited it as an early influence on his career. Horror filmmaker and heavy metal musician Rob Zombie sees it as a major influence on his work, including his films House of 1000 Corpses (2003) and The Devil's Rejects (2005).

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was selected for the 1975 Cannes Film Festival Directors' Fortnight and London Film Festival. In 1976, it won the Special Jury Prize at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival in France. Entertainment Weekly ranked the film sixth on its 2003 list of "The Top 50 Cult Films". In a 2005 Total Film poll, it was selected as the greatest horror film of all time. It was named among Time's top 25 horror films in 2007. In 2008 the film ranked number 199 on Empire magazine's list of "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire also ranked it 46th in its list of the 50 greatest independent films. In a 2010 Total Film poll, it was again selected as the greatest horror film; the judging panel included veteran horror directors such as John Carpenter, Wes Craven, and George A. Romero. In 2010, as well, The Guardian ranked it number 14 on its list of the top 25 horror films. It was also voted the greatest horror film of all time in Slant Magazine's 2013 list of the greatest horror films of all time. It was also voted the scariest movie of all time in a 2017 list by Complex and voted the best horror movie of all time in a 2017 list by Thrillist. It was also voted the scariest movie of all time in a 2018 list by Consequence of Sound and voted the best horror movie of all time in a 2018 list by Esquire.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was inducted into the Horror Hall of Fame in 1990, with director Hooper accepting the award, and it is part of the permanent collection of New York City's Museum of Modern Art. In 2012, the film was named by critics in the British Film Institute's Sight & Sound magazine as one of the 250 greatest films. The Academy Film Archive houses the Texas Chain Saw Massacre Collection, which contains over fifty items, including many original elements for the film.

Themes and analysis

Contemporary American life

— Christopher SharrettHooper's apocalyptic landscape is ... a desert wasteland of dissolution where once vibrant myth is desiccated. The ideas and iconography of Cooper, Bret Harte and Francis Parkman are now transmogrified into yards of dying cattle, abandoned gasoline stations, defiled graveyards, crumbling mansions, and a ramshackle farmhouse of psychotic killers. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre ... recognizable as a statement about the dead end of American experience.

Critic Christopher Sharrett argues that since Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960) and The Birds (1963), the American horror film has been defined by the questions it poses "about the fundamental validity of the American civilizing process", concerns amplified during the 1970s by the "delegitimation of authority in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate". "If Psycho began an exploration of a new sense of absurdity in contemporary life, of the collapse of causality and the diseased underbelly of American Gothic", he writes, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre "carries this exploration to a logical conclusion, addressing many of the issues of Hitchcock's film while refusing comforting closure".

Robin Wood characterizes Leatherface and his family as victims of industrial capitalism, their jobs as slaughterhouse workers having been rendered obsolete by technological advances. He states that the picture "brings to focus a spirit of negativity ... that seems to lie not far below the surface of the modern collective consciousness". Naomi Merritt explores the film's representation of "cannibalistic capitalism" in relation to Georges Bataille's theory of taboo and transgression. She elaborates on Wood's analysis, stating that the Sawyer family's values "reflect, or correspond to, established and interdependent American institutions ... but their embodiment of these social units is perverted and transgressive."

In Kim Newman's view, Hooper's presentation of the Sawyer family during the dinner scene parodies a typical American sitcom family: the gas station owner is the bread-winning father figure; the killer Leatherface is depicted as a bourgeois housewife; the hitchhiker acts as the rebellious teenager. Isabel Cristina Pinedo, author of Recreational Terror: Women and the Pleasures of Horror Film Viewing, states, "The horror genre must keep terror and comedy in tension if it is to successfully tread the thin line that separates it from terrorism and parody ... this delicate balance is struck in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in which the decaying corpse of Grandpa not only incorporates horrific and humorous effects, but actually uses one to exacerbate the other."

Violence against women

The underlying themes of the film have been the subject of extensive critical discussion; critics and scholars have interpreted it as a paradigmatic exploitation film in which female protagonists are subjected to brutal, sadistic violence. Stephen Prince comments that the horror is "born of the torment of the young woman subjected to imprisonment and abuse amid decaying arms ... and mobiles made of human bones and teeth." As with many slasher films, it incorporates the "final girl" trope—the heroine and inevitable lone survivor who somehow escapes the horror that befalls the other characters: Sally Hardesty is wounded and tortured, yet manages to survive with the help of a male truck driver. Critics argue that even in exploitation films in which the ratio of male and female deaths is roughly equal, the images that linger will be of the violence committed against the female characters. The specific case of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre provides support for this argument: three men are killed in quick fashion, but one woman is brutally slaughtered—hung on a meathook—and the surviving woman endures physical and mental torture. In 1977, critic Mary Mackey described the meathook scene as probably the most brutal onscreen female death in any commercially distributed film. She placed it in a lineage of violent films that depict women as weak and incapable of protecting themselves.

In one study, a group of men were shown five films depicting differing levels of violence against women. On first viewing The Texas Chain Saw Massacre they experienced symptoms of depression and anxiety; however, upon subsequent viewing they found the violence against women less offensive and more enjoyable. Another study, investigating gender-specific perceptions of slasher films, involved 30 male and 30 female university students. One male participant described the screaming, especially Sally's, as the "most freaky thing" in the film.

According to Jesse Stommel of Bright Lights Film Journal, the lack of explicit violence in the film forces viewers to question their own fascination with violence that they play a central role in imagining. Nonetheless—citing its feverish camera moves, repeated bursts of light, and auditory pandemonium—Stommel asserts that it involves the audience primarily on a sensory rather than an intellectual level.

Vegetarianism

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre has been described as "the ultimate pro-vegetarian film" due to its animal rights themes. In a video essay, film critic Rob Ager describes the irony in humans' being slaughtered for meat, putting humans in the position of being slaughtered like farm animals. Director Tobe Hooper has confirmed that "it's a film about meat" and even gave up meat while making the film, saying, "In a way I thought the heart of the film was about meat; it's about the chain of life and killing sentient beings." Writer-director Guillermo del Toro became a vegetarian for a time after seeing the film.

Post-release

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre has appeared on various home video formats. In the US, it was first released on videotape and CED in the early 1980s by Wizard Video and Vestron Video. The British Board of Film Classification had long since refused a certification for the uncut theatrical version and in 1984 they also refused to certify it for home video, amid a moral panic surrounding "video nasties". After the retirement of BBFC Director James Ferman in 1999, the board passed the film uncut for theatrical and video distribution with an 18 certificate, almost 25 years after the original release. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was released on LaserDisc in the United States in November 1993. It was initially released on DVD in October 1998 in the United States, May 2000 in the United Kingdom and 2001 in Australia.

In 2005 the film received a 2K scan and full restoration from the original 16mm A/B rolls, which was subsequently released on DVD and Blu-ray. In 2014, a more extensive 4K restoration, supervised by Hooper, using the original 16mm A/B reversal rolls, was carried out. After a screening in the Directors' Fortnight section of the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, this was also released on DVD and Blu-ray worldwide. Dark Sky Films' US 40th Anniversary Edition was nominated for Best DVD/BD Special Edition Release at the 2015 Saturn Awards. In 2024, for the film's 50th anniversary, the film was released to Ultra HD Blu-ray and re-released to VHS in a collector's edition.

In 1982, shortly after The Texas Chain Saw Massacre established itself as a success on US home video, Wizard Video released a mass-market video game adaptation for the Atari 2600. In the game, the player assumes the role of Leatherface and attempts to murder trespassers while avoiding obstacles such as fences and cow skulls. As one of the first horror-themed video games, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre caused controversy when it was first released due to its violent nature; it sold poorly as a result, because many game stores refused to stock it.

The film has been followed by eight other films to date, including sequels, prequels and remakes. The first sequel, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986), was considerably more graphic and violent than the original and was banned in Australia for 20 years before it was released on DVD in a revised special edition in October 2006. Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (1990) was the second sequel to appear, though Hooper did not return to direct due to scheduling conflicts with another film, Spontaneous Combustion. Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation, starring Renée Zellweger and Matthew McConaughey, was released in 1995. While briefly acknowledging the events of the preceding two sequels, its plot makes it a virtual remake of the 1974 original. A straight remake, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, was released by Platinum Dunes and New Line Cinema in 2003. It was followed by a prequel, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning, in 2006. A seventh film, Texas Chainsaw 3D, was released on January 4, 2013. It is a direct sequel to the original 1974 film, with no relation to the previous sequels, or the 2003 remake. Another prequel, Leatherface, was released exclusively to DirecTV on September 21, 2017, before receiving a wider release on video on demand and in limited theaters, simultaneously, in North America on October 20, 2017. Another sequel, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, was released exclusively on Netflix on February 18, 2022.

See also

Notes

- While the original theatrical release poster and many references to the film render its title as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the official spelling is The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, per the film's opening credits. This is also the title under which the film is registered with the U.S. Copyright Office.

References

- "THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE (18)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- David, Colker (August 8, 2014). "Marilyn Burns dies at 65; starred in 'Texas Chain Saw Massacre'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)". The Numbers. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ^ "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- "The Texas chain saw massacre : prev. entitled Headcheese & Leatherface". United States Copyright Office. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- Allon 2002, p. 246

- Baumgarten, Marjorie (October 27, 2000). "Tobe Hooper Remembers The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". The Austin Chronicle. Austin, Texas: Austin Chronicle Corp. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Hooper, Tobe (2008). Tobe Hooper Interview (DVD). Dark Sky Films. Event occurs at 00:00:58–00:01:14; 00:01:38–00:02:00.

- Summers, Chris (2003). "BBC Crime Case Closed – Ed Gein". BBC. Archived from the original on February 4, 2004. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- Allon 2002, p. 248

- ^ Bowen 2004, p. 17

- ^ Gregory, David (Director and Writer) (2000). Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Shocking Truth (Documentary). Blue Underground.

- Smith, Joseph W. (2009). The Psycho File: A Comprehensive Guide to Hitchcock's classic shocker. McFarland & Company. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7864-4487-8.

- ^ Hooper, Tobe (Director) (2008). The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (DVD). Dark Sky Films. Event occurs at 00:01:00–00:01:22.

- "The Man Hollywood Trusts". Texas Monthly. Vol. 17, no. 9. Austin, Texas: Genesis Park, LP. September 1989. p. 185. ISSN 0148-7736.

- Bloom 2004, p. 2

- Henkel, Kim (Writer) (2008). Kim Henkel Interview (DVD). Dark Sky Films. Event occurs at 00:01:16–00:03:19.

- Armstrong, Kent Byron (2003). Slasher Films: An International Filmography, 1960 through 2001. McFarland & Company. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-7864-1462-8.

- ^ Farley, Ellen; Knoedelseder, William Jr. (October 1986). "The Chainsaw Massacres". Cinefantastique. Vol. 16, no. 4/5. New York City: Fourth Castle Micromedia. pp. 28–44.

- ^ Bloom 2004, p. 3

- ^ Hansen, Gunnar (May 1985). "A Date with Leatherface". Texas Monthly. Vol. 13, no. 5. Austin, Texas: Genesis Park, LP. pp. 163–4, 206. ISSN 0148-7736.

- Wood, Robin (1986). "5: The American Nightmare". Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. Columbia University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-231-05777-6.

- ^ Jaworzyn 2004, pp. 8–33

- Macor 2010, pp. 24–25

- "Teri McMinn Talks Meathooks, Chainsaws, and Massacres". Dread Central. June 24, 2009. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ West, Richard (March 1974). "Scariest Movie Ever?". Texas Monthly. Vol. 2, no. 3. Austin, Texas: Genesis Park, LP. p. 9. ISSN 0148-7736.

- Jaworzyn 2004, p. 30

- Rabin, Nathan (June 8, 2008). "John Larroquette". The A.V. Club. Chicago, Illinois: Onion, Inc. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

- Wright, Tracy (January 16, 2023). "John Larroquette was paid in marijuana to narrate 'Texas Chainsaw Massacre,' talks 'Night Court' reboot". Fox News.

- ^ Pack, MM (October 23, 2003). "The Killing Fields: A culinary history of 'The Texas Chainsaw Massacre' farmhouse". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- Staff (June 10, 2004). "The calm, peaceful life of Leatherface". CNN. Archived from the original on June 11, 2004. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- Hansen, Gunnar (Actor) (2008). The Texas Chain Saw Massacre audio commentary (DVD). Second Sight Films. Event occurs at 0:04:20.

it was 110 degrees or whatever in the sun

- Jaworzyn 2004, p. 63

- ^ Haines 2003, pp. 114–115

- Kraus, Daniel (October 1999). "Bone of My Bone, Flesh of My Flesh". Gadfly. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ^ Triplett, Gene (October 6, 2006). "First 'Chain Saw' madman remains fond of grisly role". NewsOk/The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on March 20, 2007. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- Freeland 2002, p. 241

- Weinstein, Farrah (October 15, 2003). "'Chainsaw' Cuts Up the Screen". Fox News. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- Hansen, Gunnar (Actor) (2008). The Texas Chain Saw Massacre audio commentary (DVD). Second Sight Films. Event occurs at 1:08:17.

we couldn't get the blood out of the tube onto the knife edge and so after the fourth or fifth take... I turned away from everybody... and just cut her

- ^ Smith, Nigel M (March 14, 2014). "SXSW: Tobe Hooper On Why Audiences Get 'Texas Chain Saw Massacre' Better Now Than When It Was First Released". IndieWire. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Gayne, Zach (March 18, 2014). "SXSW 2014 Interview: THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE Director Tobe Hooper Talks His Legacy of Unspeakable Horror". Screen Anarchy. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- Jaworzyn 2004, p. 33

- Bloom 2004, p. 6

- Halberstam, Judith (1995). Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters. Duke University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8223-1663-3.

- ^ Rockoff 2002, p. 42

- "They Came. They Sawed". November 2004.

- Bloom 2004, p. 5

- Bozman, Ron (Production manager) (2008). The Business of Chain Saw: Interview with Ron Bozman from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (DVD). Dark Sky Films. Event occurs at 0:11:40–0:16:25.

- Savlov, Marc (February 11, 1998). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Aronzyk, Melissa (October 12, 2003). "A New Texas Chainsaw to Fire Up Blood Lust". The Toronto Star.

- Bowen 2004, pp. 17–18

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) - Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ Cook 2000, p. 229

- "Halloween (1978) - Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Russo, John (1989). Making Movies: The Inside Guide to Independent Movie Production. Delacorte Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-385-29684-7.

- Worland 2006, p. 298

- Jaworzyn 2004, p. 40

- Vaughn, Stephen (2006). Freedom and Entertainment: Rating the Movies in an Age of New Media. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-85258-6.

- Murphy, Mary (November 20, 1974). "The Perils of a 'Chainsaw' star". Los Angeles Times. p. F.13.

- Henry, Sarah (February 12, 1976). "Mordbid 'Massacre' pulled off screen". Ottawa Citizen. p. 3. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ Bowen 2004, p. 18

- "Case Study: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- "Texas Chainsaw Massacre Rejected by the BBFC". British Board of Film Classification. March 12, 1975. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Morgan, Diannah; Gaskell, Ed (2004). Creative titling with Final Cut Pro (illustrated ed.). The Ilex Press Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-904705-15-4.

- Clarke, Sean (March 13, 2002). "Explained: Film censorship in the UK". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". August 3, 2020.

- "Entertainment: Texas Chainsaw Massacre released uncut". BBC News Online. March 16, 1999. Archived from the original on August 22, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- "Screen 'video nasty' hits Channel 4". BBC News Online. October 16, 2000. Archived from the original on January 7, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Egan, Kate (2008). Trash or Treasure?: Censorship and the Changing Meanings of the Video Nasties (illustrated ed.). Manchester University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-7190-7232-1.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review 1)". Australian Classification Board. June 1, 1975. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review 2)". Australian Classification Board. December 12, 1975. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review 3)". Australian Classification Board. July 1, 1981. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review 4)". Australian Classification Board. January 1, 1984. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Australia Parliament (1984). Parliamentary Debates, Senate Weekly Hansard. Australian Authority. p. 776.

- Davis, Laura (October 5, 2010). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Chibnall 2002, p. 16

- Bloom 2004, p. 7

- Johansson, Annika (October 22, 2003). "Succé för ny massaker". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Техасская резня бензопилой, кинопрокат – ИНОЕКИНО". inoekino.com (in Russian). Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- Gross, Linda (October 30, 1974). "'Texas Massacre' Grovels in Gore". Los Angeles Times. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1974). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- Ebert, Roger (1989). Roger Ebert's Movie Home Companion: Full-Length Reviews of Twenty Years of Movies on Video. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 748. ISBN 978-0-8362-6240-7.

- Berrigan, Donald B. (November 17, 1974). "Texas Chainsaw Massacre (R)". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- Macor 2010, p. 39

- "Variety Reviews - The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Variety. November 6, 1974. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- McCarty, John (1975). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Cinefantastique. Vol. 4, no. 3. p. 36. ASIN B001O8Q9SO.

- Staiger, Janet (2000). Perverse Spectators: The Practices of Film Reception. NYU Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-8147-8139-5.

- Westbrook, Bruce (January 19, 1992). "Films love to show off tawdry side of Texas". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre: Review". TVGuide.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- Bitel, Anton. "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Eye For Film. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- Von Doviak, Scott (2005). Hick Flicks: The Rise and Fall of Redneck Cinema. McFarland & Company. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7864-1997-5.

- Emery, Mike (November 2, 1998). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- Edmundson, Mark (1999). Nightmare on Main Street: Angels, Sadomasochism, and the Culture of Gothic. Harvard University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-674-62463-4.

- Muir 2002 p. 17

- "Review of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Empire. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- Bowen 2004, pp. 16–17

- King, Stephen (1983). Stephen King's Danse Macabre. Berkley Books. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-425-10433-0.

- Worland 2006, p. 208

- Tarantino, Quentin (2022). Cinema Speculation. W&N. p. 331.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Texas Massacre tops horror poll". BBC News Online. October 9, 2005. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- Kerekes, David; Slater, David (2000). See No Evil: Banned Films and Video Controversy (illustrated ed.). Headpress. p. 374. ISBN 978-1-900486-10-1.

- Gleiberman, Owen (August 6, 2009). "Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The template for modern horror". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 8, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- Zoglin, Richard (August 16, 1999). "Cinema: The Predecessors: They Came from Beyond". Time. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- McIntosh, Lindsay (August 19, 2006). "The frighteners". The Times. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- Magistrale, Tony (2005). Abject Terrors: Surveying the Modern and Postmodern Horror Film. Peter Lang. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8204-7056-6.

- Olsen, Mark (August 6, 2006). "Beware, the cave man". Los Angeles Times. p. 5. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- Hogan, David J. (1997). Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film. McFarland & Company. pp. 247–249. ISBN 978-0-7864-0474-2.

- Weaver, James B.; Tamborini, Ronald C. (1996). Horror Films: Current Research on Audience Preferences and Reactions. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8058-1174-2.

- Nichols, Bill (1985). Movies and Methods: An Anthology. Vol. 1 (reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-520-05408-0.

- Jicha, Tom (October 31, 1991). "Eek! Now There's A Hall Of Fame For Horror Films". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- Morris, Sophie (October 31, 2008). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (18)". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 10, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- Schechter, Harold; Everitt, David (2006). The A to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (revised, illustrated ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4165-2174-7.

- Fulwood, Neil (2003). "Censorship and Controversy". One Hundred Violent Films that Changed Cinema. Batsford. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7134-8819-7.

- Peucker, Brigitte (2007). The Material Image: Art and the Real in Film. Stanford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-8047-5431-6.

- Null, Christopher (November 22, 2003). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)". FilmCritic.com. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- Sumner, Don (2010). Horror Movie Freak (illustrated ed.). Krause Publications. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4402-0824-9.

- Ascher-Walsh, Rebecca (November 3, 2000). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- Paul, Zachary (July 22, 2017). "40 Years Later and 'The Hills Still Have Eyes'". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- Robb, Brian (2005). Ridley Scott. Pocket Essentials. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-904048-47-3.

- Biodrowski, Steve (September 20, 2008). "Alien Revisted: An Interview with Ridley Scott". Cinefantastique. Archived from the original on March 11, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- Dicker, Ron (September 15, 2008). "Aja reflects on Mirrors, his life as a director". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- Wood, Jennifer M. (October 21, 2014). "11 Things You Didn't Know About The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Esquire. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- Spencer, Megan (November 25, 2003). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". ABC. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- Jaworzyn 2004, p. 86

- "The Top 50 Cult Films". Entertainment Weekly. May 16, 2003. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- Graham, Jamie (October 10, 2005). "Shock Horror!". Total Film. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2009.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, 1974". Time. October 29, 2007. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- "Empire: The Greatest Films of All Time (200–101)". Empire. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- "The 50 Greatest Independent Films - The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Empire. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- "Future's Total Film reveals "Greatest Horror Movie Ever"". Future plc. September 29, 2010. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

- Heritage, Stuart (October 22, 2010). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: No 14 best horror film of all time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 25, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "The 100 Greatest Horror Films of All Time". Slant Magazine. October 28, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "The 50 Scariest Movies of All Time". Complex Magazine. October 7, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "The 50 Best Horror Movies of All Time". Thrillist. November 27, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "The 100 Scariest Movies of All Time". Consequence of Sound. June 7, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "The 50 Scariest Movies of All Time". Esquire Magazine. July 30, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- Davies, Steven Paul (2003). A-Z of cult films and film-makers (illustrated ed.). Batsford. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-7134-8704-6.

- "Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- "Texas Chain Saw Massacre Collection". Academy Film Archive. September 5, 2014.

- Sharrett 2004, p. 318

- Sharrett 2004, pp. 300–1

- Sharrett 2004, p. 300

- Sharrett 2004, pp. 301–2

- Sharrett 2004, p. 308

- Gelder, Ken (2000). The Horror Reader. Routledge. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-415-21355-4.

- Merritt 2010, p. 1

- Merritt 2010, p. 6

- Newman, Kim. "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Film Reference. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- Pinedo, Isabel Cristina (1997). Recreational Terror: Women and the Pleasures of Horror Film Viewing. SUNY Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7914-3441-3.

- Wood, Robin (1985). "An Introduction to the American Horror Film" (PDF). Movies and Methods. 2: 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- Weaver, James B. III (Summer 1991). "Are Slasher Horror Films Sexually Violent?". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 35 (3): 385–392. doi:10.1080/08838159109364133. ISSN 1550-6878.

- Prince, Stephen (2004). "Postmodern Elements of the Contemporary Horror Film". The Horror Film. Rutgers University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8135-3363-6.

- ^ Grant, Barry Keith (1996). The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film (illustrated ed.). University of Texas Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-292-72794-6.

- Schmidt, Leonard J.; Warner, Brooke (2002). Panic: Origins, Insight, and Treatment: Issue 63. North Atlantic Books. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-55643-396-2.

- Prince, Stephen (2000). Screening Violence (illustrated ed.). Continuum. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-485-30095-6.

- Wells, Alan; Hakanen, Ernest A. (1997). Mass Media & Society. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 476. ISBN 978-1-56750-288-6.

- Clover 1993, p. 7

- ^ Bogart, Leo (2000). Commercial Culture: The Media System and the Public Interest (2, illustrated ed.). Transaction Publishers. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-7658-0605-5.

- ^ Mackey, Mary (1977). "Women and Violence in Film". Jump Cut (14): 12–14. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- Linz, Daniel; Donnerstein, Edward; Penrod, Steven (September 1984). "The Effects of Multiple Exposures to Filmed Violence Against Women". Journal of Communication. 34 (3): 130–147. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1984.tb02180.x.

- ^ Nolan, Justin M.; Ryan, Gery W. (2000). "Fear and Loathing at the Cineplex: Gender Differences in Descriptions and Perceptions of Slasher Films". Sex Roles. 42 (1 & 2): 39. doi:10.1023/A:1007080110663. ISSN 0360-0025. S2CID 142297913.

- ^ Stommel, Jesse (February 2011). "Something That Festers". Bright Lights Film Journal. Archived from the original on April 5, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Wickman, Forrest (July 30, 2013). "The Ultimate Pro-Vegetarian Film Is the Last Movie You'd Expect". Slate. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Wickman, Forrest (July 30, 2013). "The Ultimate Pro-Vegetarian Film Is the Last Movie You'd Expect". Slate. Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- Waddell, Calum (November 2010). "Tobe Hooper Interview". Bizarre. Archived from the original on August 5, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- "Director Guillermo del Toro Became a Vegetarian Because of a Slasher Film - TMZ". YouTube. November 7, 2013. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- "Video Cassette: Top 25 Rentals". Billboard. Vol. 94, no. 7. 1982. p. 48. ISSN 0006-2510.

- American Film Institute; Arthur M. Sackler Foundation (1983). American film. Vol. 9. American Film Institute. p. 72.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cherry, Bridget (2009). Horror (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-415-45667-8.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre rated 18 by the BBFC". British Board of Film Classification. 1999. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- McGowan, Chris (November 6, 1993). "Letterbox Format's Popularity Widens" (PDF). Billboard. p. 73. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- Gilchrist, Todd (October 5, 2006). "Double Dip Digest: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". IGN. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- Coates, Tom (October 2, 2001). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". BBC. Archived from the original on January 2, 2009. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- "RIP Paul Partain; new CHAINSAW & HENRY DVDs". Fangoria. March 2, 2005. Archived from the original on February 5, 2005.

- Miska, Brad. "Full Details, 4K Stills for Restored 'The Texas Chain Saw Massacre'!". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on April 22, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- Goodfewllow, Melanie (April 22, 2014). "Cannes Directors' Fortnight 2014 lineup unveiled". Screen Daily. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- "The Academy of Science Fiction Fantasy and Horror Films". Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- Squires, John (September 17, 2024). "'The Texas Chain Saw Massacre' 50th Anniversary 4K Collector's Set Includes the Original Classic on VHS!". Bloody Disgusting!. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ Shea, Tom (February 28, 1983). "Horror films' themes reappear in video games". InfoWorld. Vol. 5, no. 9. InfoWorld Media Group. ISSN 0199-6649.

- Clark, Al (1983). The Film Yearbook, 1984 (illustrated ed.). Random House. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-394-62488-4.

- Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System (illustrated ed.). MIT Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 – SE Film (DVD)". Australian Classification Board. Archived from the original on April 5, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- Jaworzyn 2004, p. 188

- Maltin, Leonard (2000). Leonard Maltin's Movie and Video Guide. Signet. p. 1400. ISBN 978-0-451-20107-2.

- ^ Maçek, J. C. III (February 5, 2013). "No Texas, No Chainsaw, No Massacre: The True Links in the Chain". PopMatters. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Zimmerman, Samuel (February 27, 2012). "Date shifts for Sinister and Texas Chainsaw Massacre 3D". Fangoria. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- "Texas Chainsaw 3D". Rotten Tomatoes. January 9, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- Miska, Brad (June 30, 2017). "We Have the Official 'Leatherface' Release Date! (Exclusive)". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- Lee, Benjamin (February 18, 2022). "Texas Chainsaw Massacre review – it's Leatherface vs gentrifiers in nasty sequel". The Guardian. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- Scheck, Frank (February 18, 2022). "Netflix's 'Texas Chainsaw Massacre': Film Review". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- "Review: From hippies to hipsters, 'Texas Chainsaw' is back". The Independent. February 18, 2022. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- Sandwell, Ian (February 18, 2022). "Texas Chainsaw Massacre review: Is Netflix's horror sequel any good?". Digital Spy. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

Sources

- Allon, Yoram; Patterson, Hannah (2002). Contemporary North American Film Directors: A Wallflower Critical Guide. Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1-903364-52-9.

- Bloom, John (November 2004). "They Came. They Sawed". Texas Monthly. Vol. 32. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011.

- Bowen, John W. (November 2004). "Return of the Power Tool Killer". Rue Morgue. No. 42. Marrs Media. pp. 16–22. ISSN 1481-1103.

- Chibnall, Steve; Petley, Julian (2002). British Horror Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23004-9.

- Clover, Carol J. (1993). Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00620-8.

- Cook, David A. (2000). Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970–1979. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23265-5.

- Freeland, Cynthia A. (2002). The Naked and the Undead: Evil and the Appeal of Horror. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-6563-3.

- Haines, Richard W. (2003). The Moviegoing Experience, 1968–2001. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1361-4.

- Hansen, Gunnar (2013). Chain Saw Confidential: How We Made the World's Most Notorious Horror Movie. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1452114491.

- Jaworzyn, Stefan (2004). The Texas Chain Saw Massacre Companion. Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84023-660-6.

- Macor, Alison (2010). Chainsaws, Slackers, and Spy Kids: Thirty Years of Filmmaking in Austin, Texas. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72243-9.

- Merritt, Naomi (2010). "Cannibalistic Capitalism and other American Delicacies: A Bataillean Taste of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Film-Philosophy. 14 (1): 202–231. doi:10.3366/film.2010.0007. ISSN 1466-4615.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2002). Eaten Alive at a Chainsaw Massacre: The Films of Tobe Hooper. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1282-2.

- Rockoff, Adam (2002). Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978–1986. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1227-3.

- Sharrett, Christopher (2004). "The Idea of Apocalypse in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". In Grant, Barry Keith; Sharrett, Christopher (eds.). Planks of Reason: Essays on the Horror Film. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5013-2.

- Worland, Rick (2006). The Horror Film: An Introduction. Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3902-1.

- Dika, Vera (2003). Recycled Culture in Contemporary Art and Film: The Uses of Nostalgia. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01631-5.

- Donaldson, Lucy Fife (2010). "Access and Excess in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" (PDF). Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism (1).

- Greenberg, Harvey Roy (1994). Screen Memories: Hollywood Cinema on the Psychoanalytic Couch. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07287-8.

- Hand, Stephen (2004). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Games Workshop. ISBN 978-1-84416-060-0.

- Phillips, Kendall R. (2005). "The Exorcist (1973) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". Projected Fears: Horror Films and American Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98353-6.

Further reading

- Williams, Tony (December 1977). "American Cinema in the '70s: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Movie (25): 12–16.

External links

- Official Site

- Template:AllMovie title

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at Box Office Mojo

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at IMDb

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at Metacritic

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at the TCM Movie Database

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: A Visit to the Film Locations

| The Texas Chainsaw Massacre | |

|---|---|

| Films | |

| Video games |

|

| Characters | |

| Related | |

| Films directed by Tobe Hooper | |

|---|---|

|

Categories:

- 1974 films

- 1970s American films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s exploitation films

- 1970s serial killer films

- 1970s slasher films

- 1974 horror films

- 1974 independent films

- American exploitation films

- American independent films

- American teen horror films

- American serial killer films

- American slasher films

- Censored films

- Cross-dressing in American films

- Films directed by Tobe Hooper

- Films about cannibalism

- Films about families

- Films set in 1973

- Films set in abandoned houses

- Films set in Texas

- Films shot in Texas

- Films with screenplays by Kim Henkel

- Films about grave-robbing

- Films about self-harm

- Films à clef

- Films originally rejected by the British Board of Film Classification

- Films shot in 16 mm film

- Films about disability in the United States

- Films about violence against women

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Rating controversies in film

- Southern Gothic films

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (franchise) films

- Video nasties

- English-language horror films

- English-language independent films

- English-language crime films