This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Halaqah (talk | contribs) at 15:20, 25 June 2007 (revert material which violates wiki policy see talk page weasle words, religious bias, not discussing the topic, etc etc). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:20, 25 June 2007 by Halaqah (talk | contribs) (revert material which violates wiki policy see talk page weasle words, religious bias, not discussing the topic, etc etc)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| It has been suggested that Impact of Slave Trade on Africa be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since April 2007. |

- This article discusses systems of Slavery within Africa, the history and effects of the slavery trade upon Africa. And also Maafa. See Atlantic slave trade for the trans-Atlantic trade, and Arab slave trade for the Trans-Saharan and Arab Slave trade.

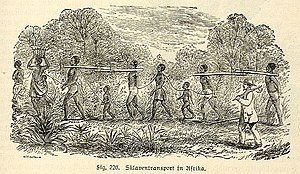

Trade in slaves, like most of the world, has carried on for thousands of years in Africa. The first main route passed through the Sahara. After the Age of Exploration, African slaves became part of the Atlantic slave trade, from which comes the modern, Western conception of slavery as an institution of African-derived slaves and non-African slave owners. Despite its illegality, slavery continues in all parts of the world, including Africa.

Slavery within Africa

In most African societies, there was very little difference between the free peasants and the feudal vassal peasants. Vassals of the Songhay Muslim Empire were used primarily in agriculture; they paid tribute to their masters in crop and service but they were slightly restricted in custom and convenience. These non-free people were more an occupational caste, as their bondage was relative..

There is adequate evidence citing case after case of African control of segments of the trade. Several African nations such as the Ashanti of Ghana and the Yoruba of Nigeria had economies largely depending on the trade. African peoples such as the Imbangala of Angola and the Nyamwezi of Tanzania would serve as intermediaries or roving bands warring with other African nations to capture Africans for Europeans. Extenuating circumstances demanding exploration are the tremendous efforts European officials in Africa used to install rulers agreeable to their interests. They would actively favor one African group against another to deliberately ignite chaos and continue their slaving activities..

Slavery in the rigid form which existed in Europe and throughout the New World was not practiced in Africa nor in the Islamic Orient. "Slavery", as it is often referred to, in African cultures was generally more like indentured servitude: "slaves" were not made to be chattel of other men, nor enslaved for life. African "slaves" were paid wages and were able to accumulate property. They often bought their own freedom and could then achieve social promotion -just as freedman in ancient Rome- some even rose to the status of kings (e.g. Jaja of Opobo and Sunni Ali Ber). Similar arguments were used by western slave owners during the time of abolition, for example by John Wedderburn in Wedderburn v. Knight, the case that ended legal recognition of slavery in Scotland in 1776. Regardless of the legal options open to slave owners, rational cost-earning calculation and/or voluntary adoption of moral restraints often tended to mitigate (except with traders, who preferred to weed out the worthless weak individuals) the actual fate of slaves throughout history.

Slavery in Songhai

In most African societies, there was very little difference between the free peasants and the feudal vassal peasants. Vassals of the Songhay Muslim Empire were used primarily in agriculture; they paid tribute to their masters in crop and service but they were slightly restricted in custom and convenience. These people were more an occupational caste, as their bondage was relative. In the Kanem Bornu Empire, vassals were three classes beneath the nobles. Marriage between captor and captive was far from rare, blurring the anticipated roles..

Slavery in Ethiopia

Ethiopian slavery was essentially domestic. Slaves thus served in the houses of their masters or mistresses, and were not employed to any significant extent for productive purposes, Slaves were thus regarded as members of their owners' family, and were fed, clothed and protected. They generally roamed around freely and conducted business as free people. They had complete freedom of religion and culture. It had been banished by its Emperors numerous times starting with Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855-1868), although not eradicated completely until 1923 with Ethiopia's ascension to the League of Nations.

Slaves taken from Africa

Trans Saharan trade

The very earliest external slave trade was the trans-Saharan slave trade. Although there had long been some trading up the Nile River and very limited trading across the western desert, the transportation of large numbers of slaves did not become viable until camels were introduced from Arabia in the 10th century. By this point, a trans-Saharan trading network came into being to transport slaves north. It has been estimated that from the 10th to the 19th century some 6,000 to 7,000 slaves were transported north each year. Over time this added up to several million people moving north. Frequent intermarriages meant that the slaves were assimilated in North Africa. Unlike in the Americas, slaves in North Africa were mainly servants rather than labourers, and a greater number of females than males were taken, who were often employed as women of harems. It was also not uncommon to turn male slaves into eunuchs to serve as guardians to the harems.

Indian Ocean trade

The trade in slaves across the Indian Ocean also has a long history beginning with the control of sea routes by Arab traders in the ninth century. It is estimated that only a few thousand slaves were taken each year from the Red Sea and Indian Ocean coast. They were sold throughout the Middle East and India. This trade accelerated as superior ships led to more trade and greater demand for labour on plantations in the region. Eventually, tens of thousands per year were being taken.

Atlantic Ocean trade

- Main article Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade developed much later, but it would eventually be by far the largest and have the greatest impact. The first Europeans to arrive on the coast of Guinea were the Portuguese; the first European to actually buy slaves in the region was Antão Gonçalves, a Portuguese explorer. Originally interested in trading mainly for gold and spices, they set up colonies on the uninhabited islands of Sao Tome. In the 16th century the Portuguese settlers found that these volcanic islands were ideal for growing sugar. Sugar growing is a labour-intensive undertaking and Portuguese settlers were difficult to attract due to the heat, lack of infrastructure, and hard life. To cultivate the sugar the Portuguese turned to large numbers of African slaves. Elmina Castle on the Gold Coast, originally built by African labor for the Portuguese in 1482 to control the gold trade, became an important depot for slaves that were to be transported to the New World.

Increasing penetration into the Americas by the Portuguese created more demand for labour in Brazil--primarily for farming and mining. To meet this demand, a trans-Atlantic slave trade soon developed. Slave-based economies quickly spread to the Caribbean and the southern portion of what is today the United States. These areas all developed an insatiable demand for slaves.

As European nations grew more powerful, especially Portugal, Spain, France and England, they began vying for control of the African slave trade, with little effect on the local African and Arab trading. Great Britain's existing colonies in the Lesser Antilles and their effective naval control of the Mid Atlantic forced other countries to abandon their enterprises due to inefficiency in cost. The English crown provided a charter giving the Royal African Company monopoly over the African slave routes until 1712.

Why African Slaves?

In the late 15th century, Europeans (Spanish and Portuguese first) began to explore, colonize and conquer the territory in the Americas. The European colonists attempted to enslave some of the Native Americans to perform hard physical labor, but found them unaccustomed to hard agrarian labor and so familiar with the local environment that it was difficult to prevent their escape. Their lack of resistance to common European diseases was another factor against their suitability for slavery. The Europeans had also noted the West African practice of enslaving prisoners of war (a common phenomenon among many peoples on all of the continents). European colonial powers traded guns, brandy and other goods for these slaves, but this had little effect on the Arabian and African trade. The African slaves proved more resistant to European diseases than indigenous Americans, familiar with a tropical climate and accustomed to agricultural work. As a result, regular trade was soon established.

Source of slaves

All three slave-trading routes tapped into local trading patterns. Europeans or Arabs in Africa very rarely mounted expeditions to capture slaves. Lack of people and the prevalence of disease prevented any widespread gathering of slaves by Europeans and other non-Africans. Local rulers were very rarely open to allowing groups of armed foreigners to enter their lands. It was far easier and more common to make use of existing African middlemen and slave traders. Slavery has been present in Africa for millennia, and still is today even with children, though some historians prefer to describe African slavery as feudalism, arguing it was more like the system that controlled the peasantry of Western Europe during the Middle Ages or Russia into the 19th century than slavery as it was practiced in the Americas.

The slaves came from many different sources. About half came from the societies that sold them. These might be criminals, heretics, the mentally ill, the indebted and any others that had fallen out of favour with the rulers. Little is known about the details of theses practices before the arrival of Europeans, and so it is difficult to tell if the number of people considered as undesirables was artificially increased to provide more slaves for export. It is believed that capital punishment in the region nearly disappeared since prisoners became far too valuable to dispose of in such a way.

Another source of slaves, comprising about half the total, came from military conquests of other states or tribes. It has long been contended that the slave trade greatly increased violence and warfare in the region due to the pursuit of slaves, but it is hard to provide evidence to prove this; warfare was certainly common even before slave hunting had added such an extra inducement.

For the Atlantic slave trade, captives were purchased from slave dealers in West African regions known as the Slave Coast, Gold Coast, and Côte d'Ivoire were sold into slavery as a result of a defeat in warfare. In the Bight of Biafra near modern-day Senegal and Benin, some African kings sold their captives locally and later to European slave traders for goods such as metal cookware, rum, livestock, and seed grain. Previous to the voyage, the victims were held in "slave castles" and deep pits where many died from multiple illnesses and malnutrition. Conditions were even worse in the Middle Passage across the Atlantic where up to a third of the slaves died en route.

Effects

| The factual accuracy of part of this article is disputed. The dispute is about too many POV of author Fage. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. See the relevant discussion on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. Such statements should be clarified or removed. |

Effect on the economy of Africa

No scholars dispute the harm done to the slaves themselves, but the effect of the trade on African societies is much debated due to the apparent influx of capital to Africans. Proponents of the slave trade, such as Archibald Dalzel, argued that African societies were robust and not much affected by the ongoing trade. In the 19th century, European abolitionists, most prominently Dr. David Livingston, took the opposite view arguing that the fragile local economy and societies were being severely harmed by the ongoing trade. This view continued with scholars until the 1960s and 70s such as Basil Davidson, who conceded it might have had some benefits while still acknowledging its largely negative impact on Africa. Historian Walter Rodney estimates that by c.1770, the King of Dahomey was earning an estimated £250,000 per year by selling captive African soldiers and even his own people to the European slave-traders. Most of this money was spent on British-made firearms (of very poor quality) and industrial-grade alcohol.

Today, however, some scholars assert that slavery did not have a wholly disastrous effect on those left behind in Africa. Slaves were an expensive commodity, and traders received a great deal in exchange for each slave. At the peak of the slave trade, it is said that hundreds of thousands of muskets, vast quantities of cloth, gunpowder and metals were being shipped to Guinea. Guinea's trade with Europe at the peak of the slave trade—which also included significant exports of gold and ivory—was some 3.5 million pounds Sterling per year. By contrast, the trade of the United Kingdom, the economic superpower of the time, was about 14 million pounds per year over this same period of the late 18th century. As Patrick Manning has pointed out, the vast majority of items traded for slaves were common rather than luxury goods. Textiles, iron ore, currency, and salt were some of the most important commodities imported as a result of the slave trade, and these goods were spread within the entire society raising the general standard of living.

Effects on Europe’s economy

Eric Williams had attempted to show the contribution of Africans on the basis of profits from the slave trade and slavery, and the employment of those profits to finance Britain’s industrialization process. He argues that the enslavement of Africans was an essential element to the Industrial Revolution, and that European wealth is a result of slavery. However, he argued that by the time of its abolition it had lost its profitability and it was in Britain's economic interest to ban it. Seymour Dreshcer and Robert Antsey have both presented evidence that the slave trade remained profitable until the end, and that reasons other than economics led to its cessation. Joseph Inikori have shown elsewhere that the British slave trade was more profitable than the critics of Williams would want us to believe.

Demographics

The demographic effects of the slave trade are some of the most controversial and debated issues. Tens of millions of people were removed from Africa via the slave trade, and what effect this had on Africa is an important question. Walter Rodney argued that the export of so many people had been a demographic disaster and had left Africa permanently disadvantaged when compared to other parts of the world, and largely explains that continent's continued poverty. He presents numbers that show that Africa's population stagnated during this period, while that of Europe and Asia grew dramatically. According to Rodney all other areas of the economy were disrupted by the slave trade as the top merchants abandoned traditional industries to pursue slaving and the lower levels of the population were disrupted by the slaving itself.

Others have challenged this view. J.D. Fage compared the number effect on the continent as a whole. David Eltis has compared the numbers to the rate of emigration from Europe during this period. In the nineteenth century alone over 50 million people left Europe for the Americas, a far higher rate than were ever taken from Africa..

Others have challenged this view. Joseph E. Inikori argues the history of the region shows that the effects were still quite deleterious. He argues that the African economic model of the period was very different from the European, and could not sustain such population losses. Population reductions in certain areas also led to widespread problems. Inikori also notes that after the suppression of the slave trade Africa's population almost immediately began to rapidly increase, even prior to the introduction of modern medicines. Shahadah also states that the trade was not only of demographic significance, in aggregate population losses but also in the profound changes to settlement patterns, epidemiological exposure and reproductive and social development potential.

In addition, the majority of the slaves being taken to the Americas were male. So while the slave trade created an immediate drop in the population, its long term effects were less drastic..

Legacy of racism

Maulana Karenga states that the effects of slavery where "the morally monstrous destruction of human possibility involved redefining African humanity to the world, poisoning past, present and future relations with others who only know us through this stereotyping and thus damaging the truly human relations among people of today." . He cites that it constituted the destruction of culture, language, religion and human possibility.

Abolition

Beginning in the late 18th century, France was Europe's first country to abolish slavery, in 1794, but it was revived by Napoleon in 1802, and banned for good in 1848. In 1807 the British Parliament passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, under which captains of slave ships could be fined for each slave transported. This was later superseded by the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, which freed all slaves in the British Empire. Abolition was then extended to the rest of Europe. The power of the Royal Navy was subsequently used to suppress the slave trade, and while some illegal trade, mostly with Brazil, continued, the Atlantic slave trade would be eradicated by the middle of the 19th century. The Saharan and Indian Ocean trades continued, however, and even increased as new sources of slaves became available. According to Mordechai Abir, with the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. The slave trade within Africa also increased. The British Navy could suppress much of the trade in the Indian Ocean, but the European powers could do little to affect the intra-continental trade.

The continuing anti-slavery movement in Europe became an excuse and a casus belli for the European conquest and colonisation of much of the African continent. In the late 19th century, the Scramble for Africa saw the continent rapidly divided between Imperialistic Europeans, and an early but secondary focus of all colonial regimes was the suppression of slavery and the slave trade. In response to this public pressure, Ethiopia officially abolished slavery in 1932. By the end of the colonial period they were mostly successful in this aim, though slavery is still very active in Africa even though it has gradually moved to a wage economy. Independent nations attempting to westernise or impress Europe sometimes cultivated an image of slavery suppression, even as they, in the case of Egypt, hired European soldiers like Samuel White Baker's expedition up the Nile. Slavery has never been eradicated in Africa, and it commonly appears in states, such as Sudan, in places where law and order have collapsed.. See also Slavery in Sudan.

Slavery in Africa in the 21st Century

Slavery persists in Africa more than in all other continents. Slavery in Mauritania was legally abolished by laws passed in 1905, 1961, and 1981, but it has never been criminalised, and several human rights organizations are reporting that the practice continues there. In Niger, slavery is a real and current phenomenon that is alive today. A Nigerien study has found that almost 8% of the population are slaves. Descent-based slavery, where generations of the same family are born into bondage, is traditionally practised by at least four of Niger’s eight ethnic groups. It is especially rife among the warlike Tuareg, in the wild deserts of north and west Niger, who roam near the borders with Mali and Algeria.

The trading of children has been reported in modern Nigeria and Benin. In parts of Ghana, a family may be punished for an offense by having to turn over a virgin female to serve as a sex slave within the offended family. In this instance, the woman does not gain the title of "wife". In parts of Ghana, Togo, and Benin, shrine slavery persists, despite being illegal in Ghana since 1998. In this system of slavery, sometimes called trokosi (in Ghana) or voodoosi in Togo and Benin, or ritual servitude, young virgin girls are given as slaves in traditional shrines and are used sexually by the priests in addition to providing free labor for the shrine. In the Sudan, slavery continues as part of an ongoing civil war; see also the Slavery in Sudan article. Evidence emerged in the late 1990s of systematic slavery in cacao plantations in West Africa. See the chocolate and slavery article.

According to Dr. Kwaku Person-Lynn, "The saddest and most painful reality of this situation is, that same slave trading is occurring today, still in the name of Islam. It is primarily happening in the countries of Mauritania, located in northwest Afrika, and Sudan, in northeast Afrika" and "if we assess what we have before us, this only leaves us to conclude that this is a horrendous misuse of Islam."

External links

- African Holocaust African Slave trade and legacy

- Set All Free - Act to end slavery - British site commemorating 200 years since the passing of Abolition of the Slave Trade Act

- Rice N Peas - Interview with an Ex-Slave

- Scale of African slavery revealed

- Nigeria's 'respectable' slave trade

- Africa's trade in children

- The story of Africa: Slavery

- Scotland and the Abolition of the Slave Trade - schools resource

- Sugar, Slavery and Civilizationl

Notes

- ^ ""African Holocaust: Dark Voyage audio CD"". "Owen 'Alik Shahadah". Retrieved 2005-04-01. Cite error: The named reference "Legacy of the African Holocaust" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ""African involvement in Atlantic Slave Trade"". "Kwaku Person-Lynn". Retrieved 2004-10-01.

- ""Slavery In Arabia"". "Owen 'Alik Shahadah".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ""Ethiopian Slave Trade"".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Fage, J.D. A History of Africa. Routledge, 4th edition, 2001. pg. 256

- ""Myths regarding the Arab Slave Trade"". "Owen 'Alik Shahadah".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Fage, J.D. A History of Africa. Routledge, 4th edition, 2001. pg. 258

- John Henrik Clarke. Critical Lessons in Slavery & the Slavetrade. A & B Book Pub

- http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/africa_caribbean/britain_trade.htm

- "Atlantic Slave Trade," Microsoft Encarta 2006.

- Fage, J.D. A History of Africa. Routledge, 4th edition, 2001. pg. 268

- Fage, J.D. A History of Africa. Routledge, 4th edition, 2001. pg. 267

- Fage, J.D. A History of Africa. Routledge, 4th edition, 2001. pg. 267

- Basil Davidson, Black mother : Africa and the Atlantic slave trade Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1980.

- Fage, J.D. A History of Africa. Routledge, 4th edition, 2001. pg. 261

- Contours of Slavery and Social Change in Africa, by Patrick Manning

- Rodney, Walter. How Europe underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, 1972

- David Eltis Economic Growth and the Ending of the Transatlantic slave trade

- "Ideology versus the Tyranny of Paradigm: Historians and the Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on African Societies," by Joseph E. Inikori African Economic History. 1994.

- ""Effects on Africa"". "Ron Karenga".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Human Rights Watch Slavery and Slave Redemption in the Sudan

- "The last law, in 1981, banned it but failed to criminalise it. However much it is denied, an ancient system of bondage, with black slaves passed on from generation to generation, still plainly exists.", The Economist

Further reading

- Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery

- Fage, J.D. A History of Africa (Routledge, 4th edition, 2001 ISBN 0-415-25247-4)

- Faragher, John Mack (2004). Out of Many. Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. p. 54. ISBN 0-13-182431-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lovejoy, Paul E. Transformations in Slavery 1983

- The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation.(Review): An article from: Population and Development Review (Digital) by Tukufu Zuberi

See also

- Atlantic slave trade

- Arab slave trade

- Islam and slavery

- Maafa

- History of slavery in the United States

- New France

- James Riley (Captain) white slaves in the Sahara

- Slavery

- Slave ship

- African Diaspora