This is an old revision of this page, as edited by SchulteMAS214 (talk | contribs) at 05:10, 31 October 2007 (→Demise). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:10, 31 October 2007 by SchulteMAS214 (talk | contribs) (→Demise)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

The daguerreotype is an early type of photograph, developed by Louis Daguerre, in which the image is exposed directly onto a mirror-polished surface of silver bearing a coating of silver halide particles deposited by iodine vapor. In later developments bromine and chlorine vapors were also used, resulting in shorter exposure times. The daguerreotype is a negative image, but the mirrored surface of the metal plate reflects the image and makes it appear positive in the proper light. Thus, daguerreotype is a direct photographic process without the capacity for duplication.

While the daguerreotype was not the first photographic process to be invented, earlier processes required hours for successful exposure, which made daguerreotype the first commercially viable photographic process and the first to permanently record and fix an image with exposure time compatible with portrait photography.

The daguerreotype is named after one of its inventors, French artist and chemist Louis J.M. Daguerre, who announced its perfection in 1839 after years of research and collaboration with Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, applying and extending a discovery by Johann Heinrich Schultz (1724): a silver and chalk mixture darkens when exposed to light. The French Academy of Sciences announced the daguerreotype process on January 9 of that year.

Daguerre's French patent was acquired by the French government. In Britain, Miles Berry, acting on Daguerre's behalf, obtained a patent for the daguerreotype process on August 14, 1839. Almost simultaneously, on August 19, 1839, the French government announced the invention a gift "Free to the World".

Daguerreotype process

The daguerreotype is a unique photographic image allowing no reproduction of the picture. Preparation of the plate prior to image exposure resulted in the formation of a layer of photo-sensitive silver halide, and exposure to a scene or image through a focusing lens formed a latent image. The latent image was made visible, or "developed", by placing the exposed plate over a slightly heated (about 75°C) cup of mercury.

The mercury vapour condensed on those places where the exposure light was most intense, in proportion with the areas of highest density in the image. This produced a picture in an amalgam, the mercury vapour attaching itself to the altered silver iodide. Removal of the mercury image by heat validates this chemistry. The developing box was constructed to allow inspection of the image through a yellow glass window while it was being developed.

The next operation was to "fix" the photographic image permanently on the plate by dipping in a solution of hyposulphite of soda – known as "fixer" or "hypo". The image produced by this method is so delicate it will not bear the slightest handling. Practically all daguerreotypes are protected from accidental damage by a glass-fronted case. It was discovered by experiment that treating the plate with heated gold chloride both tones and strengthens the image, although it remains quite delicate and requires a well-sealed case to protect against touch as well as oxidation of the fine silver deposits forming the blacks in the image. The best-preserved daguerreotypes dating from the nineteenth century are sealed in robust glass cases evacuated of air and filled with a chemically inert gas, typically nitrogen.

Proliferation

Daguerreotype photography spread rapidly across the United States but not in the United Kingdom, where Louis Daguerre controlled the practice with a patent. Richard Beard, who bought the British patent from Miles Berry in 1841, closely controlled his investment, selling licenses throughout the country and prosecuting infringers.

In the early 1840s, the invention was introduced in a period of months to practitioners in the United States by Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph code. A flourishing market in portraiture sprang up, predominantly the work of itinerant practitioners who travelled from town to town. For the first time in history, people could obtain an exact likeness of themselves or their loved ones for a modest cost, making portrait photographs extremely popular with those of modest means. Their wealthy counterparts continued to commission painted portraits by fine artists, considering the new photographic portraits inferior in much the same way their ancestors had viewed printed books as inferior to hand-scribed books centuries earlier. In some ways they were right, in other ways wrong; the vast bulk of 19th-century portrait photography effected by itinerant practitioners was of inferior artistic quality, yet the work of many portrait painters was of equally dubious artistic merit, and although photographic images were monochrome, they offered a technical likeness of the sitter no portrait painter could achieve. The first erotic photographs and the first experimenters in stereo photography also utilized daguerreotypes.

This method spread to other parts of the world as well. In 1857, Ichiki Shirō created the first known Japanese photograph, a portrait of his daimyo Shimazu Nariakira. This photograph was designated an "Important Cultural Property" by the government of Japan.

The daguerreotype is commonly, erroneously, believed to have been the dominant photographic process into the late part of the 19th century in Europe. Evidence from the period proves it was only in widespread use for approximately a decade before being superseded by other processes:

- The calotype, introduced in 1841; a negative-positive process using a paper negative.

- The ambrotype, introduced in 1854; a negative image on glass, with a black paper backing.

- The tintype or ferrotype.

- The collodion process, introduced in 1851; a negative-positive process using silver salt impregnated collodion on a glass plate.

Demise

The intricate, complex, labor-intensive daguerreotype process itself helped contribute to the rapid move to the ambrotype and tintype. The resulting reduction in economy of scale made daguerreotypes expensive and unaffordable for the average person. According to Mace (1999), the rigidity of these images stems more from the seriousness of the activity than a long exposure time, which he says was actually only a few seconds (Early Photographs, p. 21). The daguerreotype's lack of a negative image from which multiple positive "prints" could be made was a limitation also shared by the tintype and ambrotype and was not a factor in the daguerreotype's demise until the introduction of the calotype. Unlike film and paper photography however, a properly sealed daguerreotype can potentially last indefinitely.

Daguerreotype cameras are expensive. In May 2007, an anonymous buyer paid 588,613 euros (792,000 USD) for an original 1839 camera made by Susse Frères (Susse brothers), Paris, at an auction in Vienna, Austria, making it the world's oldest and most expensive commercial photographic apparatus.

The Daguerrotype's popularity was not threatened until photography was used to make imitation Daguerrotypes on glass positives called "ambrotypes."-Meaning "imperishable picture" named by "Marcus A. Root.(Newhall, 107)

Living art

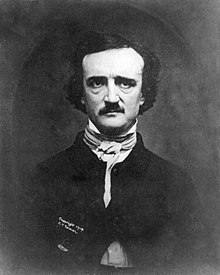

Some daguerreotypes—such as those by Southworth & Hawes of Boston, or George S. Cook of Charleston, South Carolina—are considered masterpieces in the art of photography. A daguerreotype of Edgar Allan Poe was featured on the PBS show Antiques Roadshow and appraised at US $30,000 to $50,000.

Daguerreotypy continues to be practiced by enthusiastic photographers to this day, although in much smaller numbers; there are thought to be fewer than 100 worldwide. Its appeal lies in the "magic mirror" effect of light reflected from the polished silver plate through the perfectly sharp silver image and in the sense of achievement derived from the dedication and hand-crafting required to make a daguerreotype.

The Daguerreobase

The Daguerreobase is a database registration system (currently only available in Dutch) for daguerreotypes, developed by the Nederlands fotomuseum (Rotterdam, The Netherlands). It can be used by conservators and researchers as well as viewed by those interested. Its aim is to disclose historic and technical information about the daguerreotype on a worldwide level. The project was initiated by Hans de Herder, head of the conservation department of the Nederlands fotomuseum from its instigation in 1994 until 2005. It was further developed by Belgian photo conservator Herman Maes, de Herder's successor, Boudewijn Ridder and Nickel van Duijvenboden.

References

- "LOT 2 - Le Daguerréotype Susse Frères". WestLicht Auction. 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Oldest/Most Expensive Camera". Media Speak, Inc. 2007-05-28. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- "The Daguerreotype in America" By Beaumont Newhall 1976

- Coe, Brian. The Birth of Photography, Ash & Grant, 1976.

External links

| This article's use of external links may not follow Misplaced Pages's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Jerry Spagnoli: Daguerreotypes as a Medium for Contemporary Art

- Jonathan Danforth: Contemporary Daguerreotype Artist

- Sean Culver: Artist and Contemporary Daguerreotypist

- Contemporary Daguerreotypes: a few of the people who make them today and how it is done

- An index of 19th Century American Daguerreotype Artists: Craig's Daguerreian Registry

- The Daguerreian Society: History, database and galleries

- Daguerreotype Portraits and Views, 1836-1864: US Library of Congress

- The American Handbook of the Daguerreotype from Project Gutenberg

- The Social Construction of the American Daguerreotype Portrait

- Daguerreotypes by the artist Christopher Lovenguth

- The Daguerreobase, conservator's database exclusively on daguerreotypes

- Article on daguerreotypes from Discover Magazine

- Article on making your own daguerreotypes from Instructables

- A University of Utah Podcast on Daguerreotype Theories

- America's First Look into the Camera Library of Congress

- TheDagLab: Contemporary Daguerreotypist offering tutorials, history and images.