This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Finetooth (talk | contribs) at 16:14, 21 June 2009 (fixed spelling of "thousands"). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:14, 21 June 2009 by Finetooth (talk | contribs) (fixed spelling of "thousands")(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Kohala | |

|---|---|

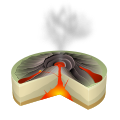

Kohala (Hawaiian: ) is the oldest of five volcanoes that make up the island of Hawaiʻi. It is believed to have breached sea level more than 500,000 years ago and to have last erupted 120,000 years ago. Toward the end of its shield-building stage 250,000 to 300,000 years ago, a landslide destroyed the northeast flank of the volcano, reducing its height by over 1,000 m (3,281 ft) and traveling 130 km (81 mi) across the sea floor. Kohala is 606 square kilometers (235 square miles) in area and 14,000 cubic kilometers (3,400 cubic miles) in volume, and thus constitutes 5.8% of the island of Hawaiʻi. It last erupted 120,000 years ago.

The volcano is pocketed by multiple deep gorges, the product of thousands of years of erosion. In violation of the typical symmetry of Hawaiian volcanoes, Kohala is shaped like a foot. Kohala is an estimated 1 million years old—so old that it experienced, and recorded, a reversal of magnetic polarity 780,000 years ago.

Geology

Geological history

In the past, Kohala was once about twice its current size. Based on a sharp increase of incline on the submarine slope of the volcano at a depth of 1,000 m (3,281 ft), scientists estimate that the portion of Kohala that was above the water was in its prime more than 50 km (31 mi) wide. The volcano began its development about one million years ago. Beginning 300,000 years ago, the rate of eruption slowly decreased over a long period of time to a point where erosion wore the volcano down faster than Kohala rebuilt itself through volcanic activity. Decreasing eruptions combined with increasing erosion caused Kohala to slowly weather away and subside into the ocean. It is difficult to determine the original size and shape of the volcano, as the southeast flank has been buried by volcanic lava flows from nearby Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. Like most Hawaiian volcanoes, Kohala is a broad volcano with a gentle angle of elevation.

The oldest lava flows that are still exposed at the surface are just under 0.78 million years old. Studies of the volcano's lava accumulation rate have put the volcano's age at somewhere near one million years. Kohala had two active rift zones, a characteristic common to Hawaiian volcanoes. The double-ridge, shaped axially, was active in both the shield and postshield stages. The southeast rift zone passes under the nearby Mauna Kea and reappears further southeast in the Hilo Ridge, as indicated by the relationship between collected lava samples. In addition, the two features align to one another more closely then does the ridge to Mauna Kea, of which it was once thought to constitute a part of. The bulk of the ridge is built of reverse polarity volcanic rock, evidence that the volcano is over 780,000 years old, the age of the oldest known lava flows. Older lava dated from the toe of the ridge was estimated to be roughly between 1.1 and 1.2 million years. The volcano's lava flows are sorted into two layers. The Hawi Volcanics layers were deposited in the shield stage of the volcano's life, and the younger Pololu Volcanics was deposited in the volcano's post-shield stage.

The volcano is so old that it experienced, and recorded, a reversal of magnetic polarity (a change in the orientation of Earth's magnetic field so that the positions North and South poles interchange) that happened 780,000 years ago. Fifty different flow units in the top 140 m (459 ft) of exposed strata in the Pololu section are of normal polarity, indicating that they were deposited within the last 0.78 million years. Radiometric datings ranged mostly from 450,000 to 320,000 years ago, although several pieces strayed lower; this indicated a period of eruptive history at the time.

The rock in the younger Hawi section, which overlies the older Pololu flows, is mostly 260 to 140 thousand years, and composed mainly of hawaiite and trachyte. The separation between the two layers is not clear; the lowest layers may actually be in the Pololu sect, based on their depositional patterns and low phosphorus content. The time intervals separating the two periods of volcanic evolution were extremely brief, something first noted in 1988.

Kohala is thought to have last erupted 120,000 years ago. However, several samples of an earlier date have been obtained. Two samples collected about 120 m (394 ft) apart, obtained from Waipio Valley on the volcano's east flank in 1977, were dated replicably to 60,000 years. Another double set of samples, collected from the western part in 1996, was measured to be 80,000 years in age. The samples have been treated with skepticism by the scientific community, and their ages have been directly challenged. The rocks collected from the west site have not been tested by subsequent experiments. The lava collected from the eastern site were allegedly found under a Mauna Loa lava flow, which had been previously dated to 187,000 years. The general agreement is that the flows are 120,000 years at their youngest, conceivably younger.

Kohala was devastated by a massive landslide between 250,000 and 300,000 years before present. Debris from the slide was found on the ocean floor up to 130 km (81 mi) away from the volcano. Twenty kilometers wide at the shoreline, the landslide cut back to the summit of the volcano, and is partially, if not largely, responsible for the volcano losing 1,000 m (3,281 ft) in height since then. The famous sea cliffs of the windward Kohala shoreline stand as evidence of the massive geologic disaster, and mark the topmost part of the debris from this ancient landslide. There are also several other unique features found on the volcano, all marks made by the decimating collapse.

The forest-covered summit of the volcano consists of many cones which generated lava from its two rift zones between 240,000 and 120,000 years ago. Kohala completed its shield-building stage 245,000 years ago and has been in decline ever since. Potassium-argon dating indicates that the volcano last erupted about 120,000 years ago in the late Pleistocene. Kohala is currently in transition between the shield and postshield Hawaiian volcanic stages in the life cycle of Hawaiian volcanoes.

In 2004, unknown marine fossils were found at the base of the volcano 6 km (4 mi) inshore. A research team led by University of Hawaii's Gary McMurtry and Dave Tappin of the British Geological Survey in Nottingham found that the fossils had been deposited by a massive tsunami, 61 m (200 ft) above the current sea level. The team dated the fossils and nearby volcanic rock at about 120,000 years old. Based on the rate of Kohala's subsidence over the past 475,000 years, it was estimated that the fossils were deposited at a height of about 500 m (1,640 ft), well out of reach of storms and far above the normal sea level at the time. The timing corresponds with the last great landslide of nearby Mauna Loa. Researchers hypothesize that the underwater landslide from the nearby volcano triggered a gigantic tsunami, which swept up coral and other small marine organisms, depositing them on the western face of Kohala. Mauna Loa, an active volcano, has since repaired its flank. Dave Tappin, a marine geologist with the British Geological Survey believes that a "future collapse on this volcano, with the potential for mega-tsunami generation, is almost certain."

The United States Geological Survey has, not surprisingly, assessed the extinct Kohala as a low-risk area. The volcano is in zone 9 (bottom risk), while the border of the volcano with Mauna Kea is zone 8 (second lowest), as Mauna Kea has not produced lava flows for 4,500 years.

Characteristics

The natural habitats in Kohala range across a wide rainfall gradient in a very short distance—from less than 5 in (127 mm) a year on the coast near Kawaihae, to more than 150 in (3,810 mm) a year near the summit of Kohala Mountain, a distance of just 11 mi (18 km). At the coast are remnants of dry forests, and near the summit is a cloud forest, a type of rainforest that obtains some of its moisture from "cloud drip" in addition to precipitation.

The volcano has several unique geomorphic features, some possibly resulting from the ancient collapse and landslide. The volcano is shaped like a foot; the northeast coast extends prominently across 20 km (12 mi) of shoreline, breaking the ordinarily smooth, rounder shape of Hawaiian volcanoes.

There is a small string of faults on and near the main summit caldera, arranged parallel to the northern coast. The faults are thought to be the result of stresses released by the prehistoric collapse. It was originally regarded to be the follow-up of the mighty collapse; however the lack of fault lines near the coastline and their arrangement tightly clustered around the caldera indicate that the fault lines were a more remote result, possibly due to the sudden release of stress during the event.

Just north of Kohala's summit is an area considered sacred to the locals. There, a small ridge separates two streams by only about a quarter of a mile. The ridge dictates whether the falling rain will go southeast, and plunge into Waipi'o Valley, or northwest, down into Honokane Valley. The ridge itself is part of the northwest-southeast trending rift zone. When the volcano was still active, vertical sheets of magma, arranged in what is known as dikes, forced their way out of the magma reservoir and intruded the rift zone, weakened by the large collapse. As the dikes forced their way up, they formed fractures and faults parallel to the rift zone. The exertion caused by the dikes produced a series of faults along the rift zone, forming horsts and grabens (fault blocks). In the northern region of Kohala, the faulted structure prevented rainwater from naturally flowing northeast down the mountain slope. Instead, the rainwater flows down laterally and empties directly into the ocean. Two grabens control the flow of water into the two valleys.

Kohala is dissected by multiple, deeply eroded stream valleys in a west-east alignment, cutting into the flanks of the volcano. The northwestern slope of Kohala has few stream valleys cut into it, the result of the rain shadow effect—the dominent trade winds bring most of the rainfall to the northeastern slope of the volcano. The valleys are more then 800 m (2,625 ft) in depth, and include the Waipio and Waimanu valleys, among the oldest and largest. The volcano stayed active well into the formation of these mountainside valleys, as the arrangement of the later-life Pololu lava flows, which separated into two directions and often went into Pololu Valley, shows this. Recent seafloor mapping seems to show that the valley extends shortly into the seafloor, and it is believed the valley formed formed from the tumbled-out rock from the landslide.

In addition to being the primary factor behind the faulting structure, the dike complex plays another important role in the development of the enormous valleys—that of creating and maintaining the water table. Hawaiian lava is extremely permeable and porous. Rainwater easily seeps into the lava, creating a large lense of fresh water below the island surface. In most places, the top of the water table is just a few feet from sea level. Unlike porous lava flows, however, dikes cool underground into dense rock with few cracks and vesicles. The dikes act as impermeable walls through which groundwater cannot flow. Rainwater that would ordinarily seep right through the ground gets trapped in the dike "reservoirs," located well above sea level. The groundwater is confined to a flow along the dike until it finds a means to escape. In Kohala, the numerous dikes near the summit inhibit groundwater from seeping downslope to the northeast, where it naturally wants to go. Rather, the Kohala dike complex guides it northwest or southeast, down the axis of the rift zones, before the water escapes it. Therefore, most of North Kohala's groundwater ends up in either the Waipi'o/Waimanu drainage or in the Honokane/Pololu drainage area. The enormous amount of water routed through these areas results in a large amount of water erosion, which causes the valley walls to frequently collapse, accelerating valley development.

On the other hand, the numerous smaller, shallow shallow stream valleys between the large ones, such as Honokane Iki, 'Awini, Honopue, Waikapu, 'Apua, and Laupahoehoe, are deprived of groundwater by the orientation of the rift zone and its dikes. Without the large amount of water that is received by the bigger valleys, these grow far slower. Meanwhile, the fault graben structure staves off stream flow near the summit, and the main caldera is affected relatively little.

Districts

Kohala is divided into two districts, North Kohala and South Kohala, as part of the County of Hawaiʻi. The beaches, parks, golf courses, and resorts in these areas are also commonly known together as the Kohala Coast. King Kamehameha I, the first King of the unified Hawaiian Islands, was born in North Kohala near Hawi. The original Kamehameha Statue stands in front of the community center in Kapaʻau, and replicas of the statue are found at Aliʻiōlani Hale in Honolulu, and in the United States Capitol at the Hall of Columns in Washington, D.C.

References

- ^ "Kohala - Hawai`i's Oldest Volcano". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. 1998-03-20. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ "Geological Map of the State of Hawaii" (PDF). USGS Hawaii geology pamphlet. USGS. 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) pp. 41–43 - Another, Māhukona, has since sank below the waves. Loihi, the youngest and smallest volcano in the chain, has neither risen from sea level or connected with the island, so it is not usually included in the five.

- "Kohala Volcano, Hawaii-Photo Information". USGS Image. USGS. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- Garcia, Michael O. (2005-09-20). "Geology, geochemistry and earthquake history of Lōʻihi Seamount, Hawaiʻi" (PDF). This is the author's personal version of a paper that was published on 2006-05-16 as "Geochemistry, and Earthquake History of Lōʻihi Seamount, Hawaiʻi's youngest volcano", in Chemie der Erde - Geochemistry (66) 2:81-108. SOEST. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Moore, James G. (1992-11). "Volcano growth and evolution of the island of Hawaii". GSA Bulletin. v. 104 (no. 11). Geological Society of America: 1471–1484. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1992)104<1471:VGAEOT>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - McDougall, Ian (December 1969). "Potassium-argon ages on lavas of Kohala volcano, Hawaii". GSA Bulletin. 80 (12). Geological Society of America: pp. 2597–2600. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1969)80[2597:PAOLOK]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Seach, John. "Kohala Volcano - John Seach". Volcansim reference base. John Seach, volcanologist. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ "Hawaiian tsunami left a gift at foot of volcano". New Scientist (2464). Reed Business Information: 14. 2004-09-11. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- "Lava Flow Hazand Zone Maps:Mauna Kea and Kohala". USGS. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- Gon III, S.M. "Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregion". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ "Origin of the Big Island's Great Valleys Revealed in Hawaiian chant". USGS weekly feature. USGS. 2006-02-16. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Mouginis-Mark, Pete. "Airphotos of Kohala". Photos of Kohala. Virtually Hawaii group, Hawaii Center of Volcanology. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- Pawlak, Debra. "The Lonely One:The Story of King Kamehameha the Great". History Comglomerate. The Mediadrome. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

Further reading

- MacDonald, Gordon A. (1983). Volcanoes in the Sea: The Geology of Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824808327.

- Wood, Charles A. (1992). Volcanoes of North America: The United States and Canada. Cambridge University Press. pp. 337–339. ISBN 978-0521438117.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)