This is an old revision of this page, as edited by The Thing That Should Not Be (talk | contribs) at 19:29, 8 September 2010 (Reverted edits by 86.8.22.23 (talk) to last revision by Gun Powder Ma (HG (Custom))). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:29, 8 September 2010 by The Thing That Should Not Be (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 86.8.22.23 (talk) to last revision by Gun Powder Ma (HG (Custom)))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

A crank is an arm attached at right angles to a rotating shaft by which reciprocating motion is imparted to or received from the shaft. It is used to change circular into reciprocating motion, or reciprocating into circular motion. The arm may be a bent portion of the shaft, or a separate arm attached to it. Attached to the end of the crank by a pivot is a rod, usually called a connecting rod. The end of the rod attached to the crank moves in a circular motion, while the other end is usually constrained to move in a linear sliding motion, in and out.

The term often refers to a human-powered crank which is used to manually turn an axle, as in a bicycle crankset or a brace and bit drill. In this case a person's arm or leg serves as the connecting rod, applying reciprocating force to the crank. Often there is a bar perpendicular to the other end of the arm, often with a freely rotatable handle on it to hold in the hand, or in the case of operation by a foot (usually with a second arm for the other foot), with a freely rotatable pedal.

Examples

Familiar examples include:

Using a hand

- mechanical pencil sharpener

- fishing reel and other reels for cables, wires, ropes, etc.

- manually operated car window

- the crank set that drives a trikke through its handles.

Using the feet

- the crankset that drives a bicycle via the pedals.

- treadle sewing machine

Engines

Almost all reciprocating engines use cranks to transform the back-and-forth motion of the pistons into rotary motion. The cranks are incorporated into a crankshaft.

Mechanics

The displacement of the end of the connecting rod is approximately proportional to the cosine of the angle of rotation of the crank, when it is measured from top dead center (TDC). So the reciprocating motion created by a steadily rotating crank and connecting rod is approximately simple harmonic motion:

where x is the distance of the end of the connecting rod from the crank axle, l is the length of the connecting rod, r is the length of the crank, and α is the angle of the crank measured from top dead center (TDC). Technically, the reciprocating motion of the connecting rod departs slightly from sinusoidal motion due to the changing angle of the connecting rod during the cycle.

The mechanical advantage of a crank, the ratio between the force on the connecting rod and the torque on the shaft, varies throughout the crank's cycle. The relationship between the two is approximately:

where is the torque and F is the force on the connecting rod. For a given force on the crank, the torque is maximum at crank angles of α = 90° or 270° from TDC. When the crank is driven by the connecting rod, a problem arises when the crank is at top dead centre (0°) or bottom dead centre (180°). At these points in the crank's cycle, a force on the connecting rod causes no torque on the crank. Therefore if the crank is stationary and happens to be at one of these two points, it cannot be started moving by the connecting rod. For this reason, in steam locomotives, whose wheels are driven by cranks, the two connecting rods are attached to the wheels at points 90° apart, so that regardless of the position of the wheels when the engine starts, at least one connecting rod will be able to exert torque to start the train.

History

Western World

Classical Antiquity

See also: Roman technology and List of Roman watermills

The eccentrically mounted handle of the rotary handmill which appeared in 5th century BC Celtiberian Spain and ultimately spread across the Roman Empire constitutes a crank. A ca. 40 cm long true iron crank was excavated, along with a pair of shattered mill-stones of 50−65 cm diameter and diverse iron items, in Aschheim, close to Munich. The crank-operated Roman mill is dated to the late 2nd century AD.

A Roman iron crank handle was excavated in Augusta Raurica, Switzerland. The 82.5 cm long piece with a 15 cm long handle is of yet unknown purpose and dates to no later than ca. 250 AD. An often cited modern reconstruction of a bucket-chain pump driven by hand-cranked flywheels from the Nemi ships has been dismissed though as "archaeological fantasy".

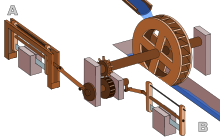

The earliest evidence for the crank as part of a machine, that is in combination with a connecting rod, anywhere in the world appears in the late Roman Hierapolis sawmill from the 3rd century AD and two Roman stone sawmills at Gerasa, Roman Syria, and Ephesus, Asia Minor (both 6th century AD). On the pediment of the Hierapolis mill, a waterwheel fed by a mill race is shown powering via a gear train two frame saws which cut rectangular blocks by the way of some kind of connecting rods and, through mechanical necessity, cranks. The accompanying inscription is in Greek.

The crank and connecting rod mechanisms of the other two archaeologically attested sawmills worked without a gear train. In ancient literature, we find a reference to the workings of water-powered marble saws close to Trier, now Germany, by the late 4th century poet Ausonius; about the same time, these mill types seem also to be indicated by the Christian saint Gregory of Nyssa from Anatolia, demonstrating a diversified use of water-power in many parts of the Roman Empire The three finds push back the date of the invention of the crank and connecting rod back by a full millennium; for the first time, all essential components of the much later steam engine were assembled by one technological culture:

With the crank and connecting rod system, all elements for constructing a steam engine (invented in 1712) — Hero's aeolipile (generating steam power), the cylinder and piston (in metal force pumps), non-return valves (in water pumps), gearing (in water mills and clocks) — were known in Roman times.

Middle Ages

See also: Medieval technology

A rotary grindstone − the earliest representation thereof − which is operated by a crank handle is shown in the Carolingian manuscript Utrecht Psalter; the pen drawing of around 830 goes back to a late antique original. A musical tract ascribed to the abbot Odo of Cluny (ca. 878−942) describes a fretted stringed instrument which was sounded by a resined wheel turned with a crank; the device later appears in two 12th century illuminated manuscripts. There are also two pictures of Fortuna cranking her wheel of destiny from this and the following century.

The use of crank handles in trepanation drills was depicted in the 1887 edition of the Dictionnaire des Antiquités Grecques et Romaines to the credit of the Spanish Muslim surgeon Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi; however, the existence of such a device cannot be confirmed by the original illuminations and thus has to be discounted. The Benedictine monk Theophilus Presbyter (c. 1070−1125) described crank handles "used in the turning of casting cores".

The Italian physician Guido da Vigevano (c. 1280−1349), planning for a new crusade, made illustrations for a paddle boat and war carriages that were propelled by manually turned compound cranks and gear wheels (center of image). The Luttrell Psalter, dating to around 1340, describes a grindstone which was rotated by two cranks, one at each end of its axle; the geared hand-mill, operated either with one or two cranks, appeared later in the 15th century;

Medieval cranes were occasionally powered by cranks, although more often by windlasses.

Renaissance

See also: Renaissance technology

The crank became common in Europe by the early 15th century, often seen in the works of those such as the German military engineer Konrad Kyeser. Devices depicted in Kyeser's Bellifortis include cranked windlasses (instead of spoke-wheels) for spanning siege crossbows, cranked chain of buckets for water-lifting and cranks fitted to a wheel of bells. Kyeser also equipped the Archimedes screws for water-raising with a crank handle, an innovation which subsequently replaced the ancient practice of working the pipe by treading. The earliest evidence for the fitting of a well-hoist with cranks is found in a miniature of c. 1425 in the German Hausbuch of the Mendel Foundation.

The first depictions of the compound crank in the carpenter's brace appear between 1420 and 1430 in various northern European artwork. The rapid adoption of the compound crank can be traced in the works of the Anonymous of the Hussite Wars, an unknown German engineer writing on the state of the military technology of his day: first, the connecting-rod, applied to cranks, reappeared, second, double compound cranks also began to be equipped with connecting-rods and third, the flywheel was employed for these cranks to get them over the 'dead-spot'.

One of the drawings of the Anonymous of the Hussite Wars shows a boat with a pair of paddle-wheels at each end turned by men operating compound cranks (see above). The concept was much improved by the Italian Roberto Valturio in 1463, who devised a boat with five sets, where the parallel cranks are all joined to a single power source by one connecting-rod, an idea also taken up by his compatriot Francesco di Giorgio.

In Renaissance Italy, the earliest evidence of a compound crank and connecting-rod is found in the sketch books of Taccola, but the device is still mechanically misunderstood. A sound grasp of the crank motion involved demonstrates a little later Pisanello who painted a piston-pump driven by a water-wheel and operated by two simple cranks and two connecting-rods.

The 15th century also saw the introduction of cranked rack-and-pinion devices, called cranequins, which were fitted to the crossbow's stock as a means of exerting even more force while spanning the missile weapon (see right). In the textile industry, cranked reels for winding skeins of yarn were introduced.

Around 1480, the early medieval rotary grindstone was improved with a treadle and crank mechanism. Cranks mounted on push-carts first appear in a German engraving of 1589.

From the 16th century onwards, evidence of cranks and connecting rods integrated into machine design becomes abundant in the technological treatises of the period: Agostino Ramelli's The Diverse and Artifactitious Machines of 1588 alone depicts eighteen examples, a number which rises in the Theatrum Machinarum Novum by Georg Andreas Böckler to 45 different machines, one third of the total.

Far East

The earliest true crank handle in Han China occurs, as Han era glazed-earthenware tomb models portray, in a agricultural winnowing fan, dated no later than 200 AD. The crank was used thereafter in China for silk-reeling and hemp-spinning, in the water-powered flour-sifter, for hydraulic-powered metallurgic bellows, and in the well windlass. However, the potential of the crank of converting circular motion into reciprocal one never seems to have been fully realized in China, and the crank was typically absent from such machines until the turn of the 20th century.

Middle East

While the US-American historian of technology Lynn White could not find "firm evidence of even the simplest application of the crank until al-Jazari's book of A.D. 1206", the crank appears according to Beeston in the mid-9th century in several of the hydraulic devices described by the Banū Mūsā brothers in their Book of Ingenious Devices. These devices, however, made only partial rotations and could not transmit much power, although only a small modification would have been required to convert it to a crankshaft.

Al-Jazari (1136–1206) described a crank and connecting rod system in a rotating machine in two of his water-raising machines. His twin-cylinder pump incorporated a crankshaft, but the device was unnecessarily complex indicating that he still did not fully understand the concept of power conversion. Another other machine of al-Jazari incorporated the first known crank-slider mechanism.

After al-Jazari, according to White, cranks in Islamic technology are not traceable until an early 15th century copy of the Mechanics of the ancient Greek engineer Hero of Alexandria.

Cranks were formerly common on some machines in the early 20th century; for example almost all phonographs before the 1930s were powered by clockwork motors wound with cranks, and internal combustion engines of automobiles were usually started with cranks (known as starting handles in the UK), before electric starters came into general use.

See also

References

- ^ Laur-Belart 1988, p. 51–52, 56, fig. 42

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 159

- ^ Lucas 2005, p. 5, fn. 9

- Volpert 1997, pp. 195, 199

- White, Jr. 1962, pp. 105f.; Oleson 1984, pp. 230f.

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 161:

Because of the findings at Ephesus and Gerasa the invention of the crank and connecting rod system has had to be redated from the 13th to the 6th c; now the Hierapolis relief takes it back another three centuries, which confirms that water-powered stone saw mills were indeed in use when Ausonius wrote his Mosella.

- Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 139–141

- Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 149–153

- Mangartz 2006, pp. 579f.

- Wilson 2002, p. 16 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWilson2002 (help)

- Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 156, fn. 74

- ^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 110

- Hägermann & Schneider 1997, pp. 425f.

- ^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 170

- Needham 1986, pp. 112–113 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNeedham1986 (help).

- Hall 1979, p. 80

- ^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 111

- Hall 1979, p. 48

- White, Jr. 1962, pp. 105, 111, 168

- White, Jr. 1962, p. 167; Hall 1979, p. 52

- White, Jr. 1962, p. 112

- White, Jr. 1962, p. 114

- ^ White, Jr. 1962, p. 113

- Hall 1979, pp. 74f.

- White, Jr. 1962, p. 167

- White, Jr. 1962, p. 172

- N. Sivin (August 1968), "Review: Science and Civilisation in China by Joseph Needham", Journal of Asian Studies, 27 (4), Association for Asian Studies: 859–864 , retrieved 13/03/2010

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - White, Jr. 1962, p. 104

- Needham 1986, pp. 118–119 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNeedham1986 (help).

- White, Jr. 1962, p. 104:

Yet a student of the Chinese technology of the early twentieth century remarks that even a generation ago the Chinese had not 'reached that stage where continuous rotary motion is substituted for reciprocating motion in technical contrivances such as the drill, lathe, saw, etc. To take this step familiarity with the crank is necessary. The crank in its simple rudimentary form we find in the Chinese windlass, which use of the device, however, has apparently not given the impulse to change reciprocating into circular motion in other contrivances'. In China the crank was known, but remained dormant for at least nineteen centuries, its explosive potential for applied mechanics being unrecognized and unexploited.

- A. F. L. Beeston, M. J. L. Young, J. D. Latham, Robert Bertram Serjeant (1990), The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature, Cambridge University Press, p. 266, ISBN 0521327636

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - al-Hassan & Hill 1992, pp. 45, 61

- Banu Musa, Donald Routledge Hill (1979), The book of ingenious devices (Kitāb al-ḥiyal), Springer, pp. 23–4, ISBN 9027708339

- Ahmad Y Hassan. The Crank-Connecting Rod System in a Continuously Rotating Machine.

- Sally Ganchy, Sarah Gancher (2009), Islam and Science, Medicine, and Technology, The Rosen Publishing Group, p. 41, ISBN 1435850661

- White, Jr. 1962, p. 170:

However, that al-Jazari did not entirely grasp the meaning of the crank for joining reciprocating with rotary motion is shown by his extraordinarily complex pump powered through a cog-wheel mounted eccentrically on its axle.

- Lotfi Romdhane & Saïd Zeghloul (2010), "Al-Jazari (1136–1206)", History of Mechanism and Machine Science, 7, Springer: 1–21, doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2346-9, ISBN 978-90-481-2346-9, ISSN 1875-3442

Bibliography

- Hall, Bert S. (1979), The Technological Illustrations of the So-Called "Anonymous of the Hussite Wars". Codex Latinus Monacensis 197, Part 1, Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, ISBN 3-920153-93-6

- Hägermann, Dieter; Schneider, Helmuth (1997), Propyläen Technikgeschichte. Landbau und Handwerk, 750 v. Chr. bis 1000 n. Chr. (2nd ed.), Berlin, ISBN 3-549-05632-X

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - al-Hassan, Ahmad Y.; Hill, Donald R. (1992), Islamic Technology. An Illustrated History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-422396

- Lucas, Adam Robert (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", Technology and Culture, 46: 1–30, doi:10.1353/tech.2005.0026

- Laur-Belart, Rudolf (1988), Führer durch Augusta Raurica (5th ed.), Augst

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mangartz, Fritz (2006), "Zur Rekonstruktion der wassergetriebenen byzantinischen Steinsägemaschine von Ephesos, Türkei. Vorbericht", Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 36 (1): 573–590

- Needham, Joseph (1991), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology: Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521058031.

- Oleson, John Peter (1984), Greek and Roman Mechanical Water-Lifting Devices: The History of a Technology, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 90-277-1693-5

- Volpert, Hans-Peter (1997), "Eine römische Kurbelmühle aus Aschheim, Lkr. München", Bericht der bayerischen Bodendenkmalpflege, 38: 193–199, ISBN 3-7749-2903-3

- White, Jr., Lynn (1962), Medieval Technology and Social Change, Oxford: At the Clarendon Press

- Ritti, Tullia; Grewe, Klaus; Kessener, Paul (2007), "A Relief of a Water-powered Stone Saw Mill on a Sarcophagus at Hierapolis and its Implications", Journal of Roman Archaeology, 20: 138–163

External links

- Crank highlight: Hypervideo of construction and operation of a four cylinder internal combustion engine courtesy of Ford Motor Company

- Kinematic Models for Design Digital Library (KMODDL) - Movies and photos of hundreds of working mechanical-systems models at Cornell University. Also includes an e-book library of classic texts on mechanical design and engineering.

| Heat engines | |

|---|---|

| Thermodynamic cycle |

is the torque and F is the force on the connecting rod. For a given force on the crank, the torque is maximum at crank angles of α = 90° or 270° from TDC. When the crank is driven by the connecting rod, a problem arises when the crank is at

is the torque and F is the force on the connecting rod. For a given force on the crank, the torque is maximum at crank angles of α = 90° or 270° from TDC. When the crank is driven by the connecting rod, a problem arises when the crank is at